Monetary Policy and the Federal Reserve: Current Policy and Conditions

Congress has delegated responsibility for monetary policy to the Federal Reserve (the Fed), the nation’s central bank, but retains oversight responsibilities for ensuring that the Fed is adhering to its statutory mandate of “maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.” To meet its price stability mandate, the Fed has set a longer-run goal of 2% inflation.

The Fed’s control over monetary policy stems from its exclusive ability to alter the money supply and credit conditions more broadly. Normally, the Fed conducts monetary policy by setting a target for the federal funds rate, the rate at which banks borrow and lend reserves on an overnight basis. It meets its target through open market operations, financial transactions traditionally involving U.S. Treasury securities. Beginning in 2007, the federal funds target was reduced from 5.25% to a range of 0% to 0.25% in December 2008, which economists call the zero lower bound. By historical standards, rates were kept unusually low for an unusually long time to mitigate the effects of the 2007-2009 financial crisis and its aftermath. Starting in December 2015, the Fed began raising interest rates. In total, the Fed raised rates nine times between 2015 and 2018, by 0.25 percentage points each time. In light of increased economic uncertainty, the Fed then reduced interest rates by 0.25 percentage points in a series of steps beginning in July 2019.

The Fed influences interest rates to affect interest-sensitive spending, such as business capital spending on plant and equipment, household spending on consumer durables, and residential investment. In addition, when interest rates diverge between countries, it causes capital flows that affect the exchange rate between foreign currencies and the dollar, which in turn affects spending on exports and imports. Through these channels, monetary policy can be used to stimulate or slow aggregate spending in the short run. In the long run, monetary policy mainly affects inflation. A low and stable rate of inflation promotes price transparency and, thereby, sounder economic decisions.

The Fed’s relative independence from Congress and the Administration has been justified by many economists on the grounds that it reduces political pressure to make monetary policy decisions that are inconsistent with a long-term focus on stable inflation. But independence reduces accountability to Congress and the Administration, and recent criticism of the Fed by the President has raised the question about the proper balance between the two.

While the federal funds target was at the zero lower bound, the Fed attempted to provide additional stimulus through unsterilized purchases of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities (MBS), a practice popularly referred to as quantitative easing (QE). Between 2009 and 2014, the Fed undertook three rounds of QE. The third round was completed in October 2014, at which point the Fed’s balance sheet was $4.5 trillion—five times its precrisis size. After QE ended, the Fed maintained the balance sheet at the same level until September 2017, when it began to very gradually reduce it to a more normal size. The Fed has raised interest rates in the presence of a large balance sheet through the use of two new tools—by paying banks interest on reserves held at the Fed and by engaging in reverse repurchase agreements (reverse repos) through a new overnight facility. In January 2019, the Fed announced that it would continue using these tools to set interest rates permanently. In August 2019, it stopped reducing the balance sheet from its current size of $3.8 trillion. However, the remaining MBS on its balance sheet would gradually be replaced with Treasury securities as they mature. In response to turmoil in the repo market in September 2019, the Fed began intervening in the repo market and began expanding its balance sheet again in October 2019.

With regard to its mandate, the Fed believes that unemployment is currently lower than the rate that it considers consistent with maximum employment, and inflation is running slightly below the Fed’s 2% goal by the Fed’s preferred measure. Monetary policy is still considered expansionary, which is unusual at this stage of an expansion, and is being coupled with a stimulative fiscal policy (larger structural budget deficit). The decision to cut rates in 2019 was controversial. The Fed justified the cut on the grounds that risks of a growth slowdown had intensified and inflation was still below 2%. But it also argued that the economy was still strong, and some of the risks to the economy, such as higher tariffs, had not yet materialized at the time of the decision. Overly stimulative monetary policy in a strong expansion risks economic overheating, high inflation, or asset bubbles.

Monetary Policy and the Federal Reserve: Current Policy and Conditions

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Recent Monetary Policy Developments

- How Does the Federal Reserve Execute Monetary Policy?

- Policy Tools

- Targeting Interest Rates versus Targeting the Money Supply

- Real versus Nominal Interest Rates

- Economic Effects of Monetary Policy in the Short Run and Long Run

- Low Interest Rates and the Neutral Rate

- Monetary versus Fiscal Policy

- Unconventional Monetary Policy and the Fed's Balance Sheet during and after the Financial Crisis

- The "Exit Strategy": Normalization of Monetary Policy after QE

- The Federal Reserve's Response to Repo Market Turmoil in September 2019

- The Federal Reserve's Review of Monetary Policy Strategy, Tools, and Communications

Tables

Appendixes

Summary

Congress has delegated responsibility for monetary policy to the Federal Reserve (the Fed), the nation's central bank, but retains oversight responsibilities for ensuring that the Fed is adhering to its statutory mandate of "maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates." To meet its price stability mandate, the Fed has set a longer-run goal of 2% inflation.

The Fed's control over monetary policy stems from its exclusive ability to alter the money supply and credit conditions more broadly. Normally, the Fed conducts monetary policy by setting a target for the federal funds rate, the rate at which banks borrow and lend reserves on an overnight basis. It meets its target through open market operations, financial transactions traditionally involving U.S. Treasury securities. Beginning in 2007, the federal funds target was reduced from 5.25% to a range of 0% to 0.25% in December 2008, which economists call the zero lower bound. By historical standards, rates were kept unusually low for an unusually long time to mitigate the effects of the 2007-2009 financial crisis and its aftermath. Starting in December 2015, the Fed began raising interest rates. In total, the Fed raised rates nine times between 2015 and 2018, by 0.25 percentage points each time. In light of increased economic uncertainty, the Fed then reduced interest rates by 0.25 percentage points in a series of steps beginning in July 2019.

The Fed influences interest rates to affect interest-sensitive spending, such as business capital spending on plant and equipment, household spending on consumer durables, and residential investment. In addition, when interest rates diverge between countries, it causes capital flows that affect the exchange rate between foreign currencies and the dollar, which in turn affects spending on exports and imports. Through these channels, monetary policy can be used to stimulate or slow aggregate spending in the short run. In the long run, monetary policy mainly affects inflation. A low and stable rate of inflation promotes price transparency and, thereby, sounder economic decisions.

The Fed's relative independence from Congress and the Administration has been justified by many economists on the grounds that it reduces political pressure to make monetary policy decisions that are inconsistent with a long-term focus on stable inflation. But independence reduces accountability to Congress and the Administration, and recent criticism of the Fed by the President has raised the question about the proper balance between the two.

While the federal funds target was at the zero lower bound, the Fed attempted to provide additional stimulus through unsterilized purchases of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities (MBS), a practice popularly referred to as quantitative easing (QE). Between 2009 and 2014, the Fed undertook three rounds of QE. The third round was completed in October 2014, at which point the Fed's balance sheet was $4.5 trillion—five times its precrisis size. After QE ended, the Fed maintained the balance sheet at the same level until September 2017, when it began to very gradually reduce it to a more normal size. The Fed has raised interest rates in the presence of a large balance sheet through the use of two new tools—by paying banks interest on reserves held at the Fed and by engaging in reverse repurchase agreements (reverse repos) through a new overnight facility. In January 2019, the Fed announced that it would continue using these tools to set interest rates permanently. In August 2019, it stopped reducing the balance sheet from its current size of $3.8 trillion. However, the remaining MBS on its balance sheet would gradually be replaced with Treasury securities as they mature. In response to turmoil in the repo market in September 2019, the Fed began intervening in the repo market and began expanding its balance sheet again in October 2019.

With regard to its mandate, the Fed believes that unemployment is currently lower than the rate that it considers consistent with maximum employment, and inflation is running slightly below the Fed's 2% goal by the Fed's preferred measure. Monetary policy is still considered expansionary, which is unusual at this stage of an expansion, and is being coupled with a stimulative fiscal policy (larger structural budget deficit). The decision to cut rates in 2019 was controversial. The Fed justified the cut on the grounds that risks of a growth slowdown had intensified and inflation was still below 2%. But it also argued that the economy was still strong, and some of the risks to the economy, such as higher tariffs, had not yet materialized at the time of the decision. Overly stimulative monetary policy in a strong expansion risks economic overheating, high inflation, or asset bubbles.

Introduction

The Federal Reserve's (the Fed's) responsibilities as the nation's central bank fall into four main categories: monetary policy, provision of emergency liquidity through the lender of last resort function, supervision of certain types of banks and other financial firms for safety and soundness, and provision of payment system services to financial firms and the government.1

Congress has delegated responsibility for monetary policy to the Fed, but retains oversight responsibilities to ensure that the Fed is adhering to its statutory mandate of "maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates."2 The Fed has defined stable prices as a longer-run goal of 2% inflation—the change in overall prices, as measured by the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index. By contrast, the Fed states that "it would not be appropriate to specify a fixed goal for employment; rather, the Committee's policy decisions must be informed by assessments of the maximum level of employment, recognizing that such assessments are necessarily uncertain and subject to revision."3 Monetary policy can be used to stabilize business cycle fluctuations (alternating periods of economic expansions and recessions) in the short run, while it mainly affects inflation in the long run. The Fed's conventional tool for monetary policy is to target the federal funds rate—the overnight, interbank lending rate.4

This report provides an overview of how monetary policy works and recent developments, a summary of the Fed's actions following the financial crisis, and ends with a brief overview of the Fed's regulatory responsibilities.

Recent Monetary Policy Developments

In response to the 2007-2009 financial crisis and the "Great Recession," the federal funds target was reduced to a range of 0% to 0.25% in December 2008—referred to as the zero lower bound—for the first time ever. The recession ended in 2009, but as the economic recovery consistently proved weaker than expected in the years that followed, the Fed repeatedly pushed back its time frame for raising interest rates. As a result, the economic expansion was in its seventh year and the unemployment rate was already near the Fed's estimate of full employment at the time when it began raising rates on December 16, 2015. This was a departure from past practice—in the previous two economic expansions, the Fed began raising rates within three years of the preceding recession ending. The Fed then raised rates in a series of steps to incrementally tighten monetary policy. The Fed raised rates—by 0.25 percentage points each time—once in 2016, three times in 2017, and four times in 2018.

In 2019, the expansion became the longest in U.S. history. Beginning in July 2019, the Fed reduced the federal funds target in a series of steps, by 0.25 percentage points at a time. Usually, when the Fed begins cutting interest rates, it subsequently makes several reductions over a series of months in response to the onset of a recession, although sometimes the rate cuts are more modest and short-lived "mid-cycle corrections."5 If the range of 2.25%-2.5% turns out to be the highest that the federal funds target reached in the current expansion, then it will have been much lower than at the peak of previous expansions in either nominal or inflation-adjusted terms, as shown in Table 1.

|

Date of Peak Rate |

Peak Rate (Nominal) |

Peak Rate (Inflation-Adjusted) |

Cumulative Subsequent Reduction in Nominal Rate (Percentage Points) |

|

October 1957 |

3.5% |

0.6% |

2.9 |

|

February 1960 |

4.0% |

2.6% |

2.8 |

|

September 1969 |

9.2% |

3.5% |

5.5 |

|

July 1974 |

12.9% |

1.4% |

7.7 |

|

April 1980 |

17.6% |

3.0% |

4.8 |

|

June 1981 |

19.1% |

9.4% |

10.4 |

|

May 1989 |

9.8% |

4.5% |

5.3 |

|

November 2000 |

6.5% |

3.1% |

4.8 |

|

July 2007 |

5.3% |

2.9% |

5.1 |

|

As of July 2019 |

2.4% |

0.6% |

potential max of 2.4 |

Sources: CRS calculations based on Fed data; David Reifschneider, "Gauging the Ability of the FOMC to Respond to Future Recessions," Federal Reserve, Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2016-068, August 2016.

Notes: Federal funds rate adjusted for inflation using the consumption price index. In early expansions in the table, the federal funds rate was not the explicit target of monetary policy. The table presents the average effective federal funds rate.

The rate cuts seem to have been in response to a slowdown in growth. After being persistently low by historical standards throughout the expansion, economic growth accelerated from the third quarter of 2017 through the third quarter of 2018. Since the fourth quarter of 2018, economic growth appears to have slowed from this elevated pace back toward the previous trend, where projections expect it to stay in the coming quarters.6

The Fed's decision to reduce rates can be evaluated in terms of its statutory mandate. Based on the maximum employment mandate, tight labor market conditions did not support the series of rate cuts, considering monetary policy was still slightly stimulative—adjusted for inflation, rates were close to zero even before they were cut. The unemployment rate has been below 5% since 2015 and is now lower than the rate believed to be consistent with full employment. Other labor market indicators are also consistent with full employment, with the possible exception of the still-low labor force participation rate.

Based on the price stability mandate, lower rates could be justified to avoid a potentially long-lasting decline in inflation (which would be unexpected, given labor market tightness). After remaining persistently below the Fed's 2% target from mid-2012 to early 2018 as measured by core PCE, inflation hovered around 2% in 2018 as measured by headline or core PCE. Inflation then dipped slightly below 2% again in 2019. Economic theory posits that lower unemployment will lead to higher inflation in the short run, but inflation has not proven responsive to lower unemployment in recent years.7 Arguably, the experiences of Japan since the 1990s and the euro area since the financial crisis demonstrate that persistently lower-than-desirable inflation has become a harder problem than high inflation for central banks to solve.

Monetary policy works with a lag, and if economic conditions were to deteriorate in the near future, it would be helpful to have cut rates ahead of time. Financial volatility has increased, and the Fed has argued that there are heightened risks to the economic outlook coming from the slowdown in growth abroad and the potential for economic disruptions from "trade policy uncertainty."8 (Distinct from monetary stimulus, the Fed has intervened in repo markets since September 2019 in response to repo market volatility. For more information, see the section below entitled "The Federal Reserve's Response to Repo Market Turmoil in September 2019.")

Although it believes the most likely scenario is sustained expansion, the Fed has justified the 2019 rate cuts in risk-management terms as "insurance cuts." But cutting rates also poses risks.9 The Fed has little headroom to lower rates more aggressively during the next economic downturn—the potential two-percentage-point reduction in rates remaining before hitting the zero bound is currently smaller than the rate cuts that the Fed has undertaken in past recessions, as shown in the right hand column of Table 1.10 Fed Chair Jerome Powell and other Fed officials have argued that, with limited headroom, it is better to cut rates aggressively when risks rise to nip a potential downturn in the bud.11 The counterargument is that when your arsenal is limited, it is better to keep your powder dry until you are sure it is needed. By cutting rates in 2019, the Fed leaves itself less scope for monetary stimulus in the future.

There is upside risk to cutting rates as well. If downside risks to the outlook do not materialize (for example, if a trade war is averted), monetary stimulus could cause the economy to overheat, resulting in high inflation and posing risk to financial stability. The Fed has signaled it intends to keep interest rates at their current level for now, even though some of these downside risks seem to be diminishing. As an example of how overly stimulative monetary policy can lead to financial instability, critics contend that the Fed contributed to the precrisis housing bubble by keeping interest rates too low for too long during the economic recovery starting in 2001. Critics see these risks as outweighing any marginal benefit associated with monetary stimulus when the economy is already so close to full employment.12 Finally, there is reputational risk to the Fed's independence if it appears that the Fed is cutting rates in response to political pressure from the President (see the text box "Federal Reserve Independence" below).

How Does the Federal Reserve Execute Monetary Policy?

Monetary policy refers to the actions the Fed undertakes to influence the availability and cost of money and credit to promote the goals mandated by Congress, a stable price level and maximum sustainable employment. Because the expectations of households as consumers and businesses as purchasers of capital goods exert an important influence on the major portion of spending in the United States, and because these expectations are influenced in important ways by the Fed's actions, a broader definition of monetary policy would include the directives, policies, statements, economic forecasts, and other Fed actions, especially those made by or associated with the chairman of its Board of Governors, who is the nation's central banker.

The Fed's Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meets every six weeks to choose a federal funds target and sometimes meets on an ad hoc basis if it wants to change the target between regularly scheduled meetings. The FOMC is composed of the 7 Fed governors, the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and 4 of the other 11 regional Federal Reserve Bank presidents serving on a rotating basis.13

The Fed generally tries to avoid policy surprises, and FOMC members regularly communicate their views on the future direction of monetary policy to the public. The Fed describes its monetary policy plans as "data dependent," meaning they would be altered if actual employment or inflation deviate from its forecast.

Policy Tools

The Fed targets the federal funds rate to carry out monetary policy. The federal funds rate is determined in the private market for overnight reserves of depository institutions (called the federal funds market). At the end of a given period, usually a day, depository institutions must calculate how many dollars of reserves they want or need to hold against their reservable liabilities (deposits).14 Some institutions may discover a reserve shortage (too few reservable assets relative to those they want to hold), whereas others may have reservable assets in excess of their wants. These reserves can be borrowed and lent on an overnight basis in a private market called the federal funds market. The interest rate in this market is called the federal funds rate. If it wishes to expand money and credit, the Fed will lower the target, which encourages more lending activity and, thus, greater demand in the economy. Conversely, if it wishes to tighten money and credit, the Fed will raise the target.

The federal funds rate is linked to the interest rates that banks and other financial institutions charge for loans. Thus, whereas the Fed may directly influence only a very short-term interest rate, this rate influences other longer-term rates. However, this relationship is far from being on a one-to-one basis because longer-term market rates are influenced not only by what the Fed is doing today, but also by what it is expected to do in the future and by what inflation is expected to be in the future. This fact highlights the importance of expectations in explaining market interest rates. For that reason, a growing body of literature urges the Fed to be very transparent in explaining what its policy is, will be, and in making a commitment to adhere to that policy.15 The Fed has responded to this literature and is increasingly transparent in explaining its policy measures and what these measures are expected to accomplish.

The Federal Reserve uses two methods to maintain its target for the federal funds rate:

- Traditionally, the Fed primarily relied on open market operations, which involves the Fed buying existing U.S. Treasury securities in the secondary market (i.e., those that have already been issued and sold to private investors).16 Should the Fed buy securities, it does so with the equivalent of newly issued currency (Federal Reserve notes), which expands the reserve base and increases the ability of depository institutions to make loans and expand money and credit. The reverse is true if the Fed decides to sell securities from its portfolio. The Fed must stand ready to buy or sell as many securities as necessary to maintain its federal funds target. Outright purchases of securities were used for QE from 2009 to 2014, but normal open market operations are typically conducted through repos instead, described in the text box. When the Fed wishes to add liquidity to the banking system, it enters into repos. When it wishes to remove liquidity, the Fed enters into reverse repos.17 Because of the large increase in bank reserves caused by QE, open market operations alone can no longer effectively maintain the federal funds target.

- The Fed can also change the two interest rates it administers directly by fiat, and these interest rates influence market rates—the rate it charges to borrowers and the rate it pays to depositors.

- The Fed permits depository institutions to borrow from it directly on a temporary basis at the discount window.18 That is, these institutions can discount at the Fed some of their own assets to provide a temporary means for obtaining reserves. Discounts are usually on an overnight basis. For this privilege banks are charged an interest rate called the discount rate, which is set by the Fed at a small markup over the federal funds rate.19 The Fed is referred to as the "lender of last resort" because direct lending, from the discount window and other recently created lending facilities, is negligible under normal financial conditions such as the present but was an important source of liquidity during the financial crisis.

- In October 2008, the Federal Reserve began to pay interest on reserves that banks deposit at the Fed. (It pays interest on both required and excess reserves.) Since 2008, this has been the primary tool for maintaining the federal funds target. Reducing the opportunity cost for banks of holding that money as reserves at the Fed as opposed to lending it out influences the rates at which banks are willing to lend reserves to each other, such as the federal funds rate.

|

What Are Repos? Repurchase agreements (repos) are agreements between two parties to purchase and then repurchase securities at a fixed price and future date, often overnight. Although legally structured as a pair of security sales, they are economically equivalent to a collateralized loan. The difference in price between the first and second transaction determines the interest rate on the loan. The repo market is one of the largest short-term lending markets, where banks and other financial institutions are active borrowers and lenders. For the seller of the security, who receives the cash, the transaction is called a repo. For the purchaser of the security, who lends the cash, it is called a reverse repo. (When describing transactions, the Fed uses the terminology from the perspective of its counterparty.) Collateral protects the lender against potential default. In principle, any type of security can be used as collateral, but the most common collateral—and the types used by the Fed—are Treasury securities, agency MBS, and agency debt. Note: For background on the repo market, see CRS In Focus IF11383, Repurchase Agreements (Repos): A Primer, by Marc Labonte; and Tobias Adrian et al., "Repo and Securities Lending," Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Staff Report no. 529, December 2011, available at http://www.newyorkfed.org/research/staff_reports/sr529.pdf. |

Since the financial crisis, interest on reserves has been the primary tool for influencing the federal funds rate. However, the Fed has also used reverse repos and began using repos again after repo market turmoil in September 2019 (see the section below entitled "The Federal Reserve's Response to Repo Market Turmoil in September 2019").

The Fed can also change the federal funds rate by changing reserve requirements, which specify what portion of customer deposits (primarily checking accounts) banks must hold as vault cash or on deposit at the Fed. Thus, reserve requirements affect the liquidity available within the federal funds market. Statute sets the numerical levels of reserve requirements, although the Fed has some discretion to adjust them. Currently, banks are required to hold 0% to 10% of customer deposits that qualify as net transaction accounts in reserves, depending on the size of the bank's deposits.20 This tool is used rarely—the percentage was last changed in 1992.21

Each of these tools works by altering the overall liquidity available for use by the banking system, which influences the amount of assets these institutions can acquire. These assets are often called credit because they represent loans the institutions have made to businesses and households, among others.

Targeting Interest Rates versus Targeting the Money Supply

The Fed's control over monetary policy stems from its exclusive ability to alter the money supply and credit conditions more broadly. The Fed directly controls the monetary base, which is made up of currency (Federal Reserve notes) and bank reserves. The size of the monetary base, in turn, influences broader measures of the money supply, which include close substitutes to currency, such as demand deposits (e.g., checking accounts) held at banks.

The Fed's definition of monetary policy as the actions it undertakes to influence the availability and cost of money and credit suggests two ways to measure the stance of monetary policy. One is to look at the cost of money and credit as measured by the rate of interest relative to inflation (or inflation projections), and the other is to look at the growth of money and credit itself. Thus, it is possible to look at either interest rates or the growth in the supply of money and credit in coming to a conclusion about the current stance of monetary policy—that is, whether it is expansionary (adding stimulus to the economy), contractionary (slowing economic activity), or neutral.

During the high inflation experience of the 1970s the Fed placed greater emphasis on money supply growth, but since then, most central banks including the Fed have preferred to formulate monetary policy in terms of the cost of money and credit rather than in terms of their supply. The Fed conducts monetary policy by focusing on the cost of money and credit as proxied by the federal funds rate.

Real versus Nominal Interest Rates

A simple comparison of market interest rates over time as an indicator of changes in the stance of monetary policy is potentially misleading, however. Economists call the interest rate that is essential to decisions made by households and businesses to buy capital goods the real interest rate. It is often proxied by subtracting from the market interest rate the actual or expected rate of inflation. If inflation rises and market interest rates remain the same, then real interest rates have fallen, with a similar economic effect as if market rates (called nominal rates) had fallen by the same amount with a constant inflation rate.

The federal funds rate is only one of the many interest rates in the financial system that determines economic activity. For these other rates, the real rate is largely independent of the amount of money and credit over the longer run because it is determined by the interaction of saving and investment (or the demand for capital goods). The internationalization of capital markets means that for most developed countries the relevant interaction between saving and investment that determines the real interest rate is on a global basis. Thus, real rates in the United States depend not only on U.S. national saving and investment but also on the saving and investment of other countries. For that reason, national interest rates are influenced by international credit conditions and business cycles.

Economic Effects of Monetary Policy in the Short Run and Long Run

How do changes in short-term interest rates affect the overall economy? In the short run, an expansionary monetary policy that reduces interest rates increases interest-sensitive spending, all else equal. Interest-sensitive spending includes physical investment (i.e., plant and equipment) by firms, residential investment (housing construction), and consumer-durable spending (e.g., automobiles and appliances) by households. As discussed in the next section, it also encourages exchange rate depreciation that causes exports to rise and imports to fall, all else equal. To reduce spending in the economy, the Fed raises interest rates and the process works in reverse.

An examination of U.S. economic history will show that money- and credit-induced demand expansions can have a positive effect on U.S. GDP growth and total employment. In the Fed's model of the economy, a one percentage point increase in the federal funds rate would increase the output gap by 0.2-0.5 percentage points and decrease inflation by 0.2-0.8 percentage points at its peak (after about two years).22 The extent to which greater interest-sensitive spending results in an increase in overall spending in the economy in the short run will depend in part on how close the economy is to full employment. When the economy is near full employment, the increase in spending is likely to be dissipated through higher inflation more quickly. When the economy is far below full employment, inflationary pressures are more likely to be muted. This same history, however, also suggests that over the longer run, a more rapid rate of growth of money and credit is largely dissipated in a more rapid rate of inflation with little, if any, lasting effect on real GDP and employment.23

Economists have two explanations for this paradoxical behavior. First, they note that, in the short run, many economies have an elaborate system of contracts (both implicit and explicit) that makes it difficult in a short period for significant adjustments to take place in wages and prices in response to a more rapid growth of money and credit. Second, they note that expectations for one reason or another are slow to adjust to the longer-run consequences of major changes in monetary policy. This slow adjustment also adds rigidities to wages and prices. Because of these rigidities, changes in the growth of money and credit that change aggregate demand can have a large initial effect on output and employment, albeit with a policy lag of six to eight quarters before the broader economy fully responds to monetary policy measures. Over the longer run, as contracts are renegotiated and expectations adjust, wages and prices rise in response to the change in demand and much of the change in output and employment is undone. Thus, monetary policy can matter in the short run but be fairly neutral for GDP growth and employment in the longer run.24 In the Fed's model, the effect of higher rates on the output gap disappears after five years.

In societies in which high rates of inflation are endemic, price adjustments are very rapid. During the final stages of very rapid inflations, called hyperinflation, the ability of more rapid rates of growth of money and credit to alter GDP growth and employment is virtually nonexistent, if not negative.

|

Federal Reserve Independence The Fed is more independent from Congress and the Administration than most other agencies. Its independence is attributable to structural reasons, such as 14-year terms of office for its governors, "for cause" removal, and budgetary independence,25 and as a result of unofficial norms, such as the President refraining from opining on monetary policy decisions in recent decades.26 Beginning in 2018, President Trump has upended these norms with a series of statements criticizing the Fed for first raising interest rates and then not cutting rates more quickly.27 Economists have justified this independence on the grounds that the mismatch between short-term and long-term benefits of monetary policy decisions (discussed above) creates political pressure to pursue interest rate targets that are too low to be consistent with stable inflation.28 Independence, it is argued, insulates the Fed's decisionmaking from this political pressure, and may help explain why the Fed has successfully kept inflation consistently low since the early 1990s.29 Furthermore, independence enhances the Fed's credibility that it will maintain stable inflation, it is argued, and this makes interest rate changes more potent than if inflation expectations increased whenever the Fed pursued expansionary monetary policy. For better or worse, the trade-off of more independence is less accountability to Congress and the President, however. |

Low Interest Rates and the Neutral Rate

Economists judge monetary policy to be contractionary or stimulative based on whether the actual federal funds rate is above or below, respectively, the neutral rate. The neutral interest rate (sometimes called r* or the natural rate of interest) is conceptual and not directly observed—it is the idea that at any given time there is some level for the federal funds rate that will neither stimulate nor hold back economic activity. Various statistical techniques can be used to infer the neutral rate.

Since the crisis, the federal funds rate (as well as long-term rates) has been very low by historical standards—it was nearly zero from 2008 to 2015. Before the crisis, many economists assumed that the real (inflation-adjusted) neutral rate was about 2% and fairly constant over time. At the prevailing inflation rate of 2%, that would translate to a neutral rate of about 4%. If the actual federal funds rate is consistently below the neutral rate—in other words, if monetary policy is persistently stimulative—at full employment, inflation would be expected to rise. Yet the actual federal funds rate has now been below 4% since 2008 without any noticeable sustained increase in inflation, even as the economy has returned to full employment. This outcome is consistent with a decline in the neutral rate. According to some estimates, the real neutral rate has fallen by more than a percentage point since 2008.30

Despite the drop in the neutral rate, monetary policy has largely remained stimulative since the crisis because the federal funds rate has remained below the estimated neutral rate. (As the Fed raised interest rates, it remained stimulative, but less stimulative than previously.)

A decline in the neutral rate has implications for monetary policy. It means that any given federal funds rate is less stimulative or more contractionary than it would have been before the neutral rate fell. As a result, a simple historical comparison of prevailing federal funds rates before and after the crisis would give the misleading impression that monetary policy since the crisis has been more stimulative than it actually was. (Also, inflation has been lower since the crisis than it was in earlier decades, so the difference in real rates over the decades is smaller than the difference in actual rates.)

Although the neutral rate is a useful concept for framing monetary policy decisions, uncertainty about its true value points to the difficulty of basing policy on a variable that cannot be directly observed. Choosing to set interest rates equal to the neutral rate would be intended to neither slow down nor speed up economic activity. But if the Fed has incorrectly estimated that the neutral rate has fallen more than it has, then monetary policy is still stimulative, and the risk of inflation rising or economic overheating is greater.

In light of this uncertainty, the neutral rate could be de-emphasized in policymaking, but without it, policy decisions may become less forward-looking, as the difference between actual rates and the neutral rate helps project future employment and inflation. Thus, a de-emphasis could lead to worse outcomes because of lags between policy changes and economic outcomes.

A lower neutral rate also limits how much monetary stimulus is potentially available to fight the next economic downturn before hitting the zero lower bound. This could make it necessary in the next downturn for the Fed to revive some of the unconventional tools it used in response to the financial crisis (see the section below entitled "Unconventional Monetary Policy and the Fed's Balance Sheet during and after the Financial Crisis") or try to develop alternative monetary policy strategies (as discussed in the section below "The Federal Reserve's Review of Monetary Policy Strategy, Tools, and Communications").31

Monetary versus Fiscal Policy

Either fiscal policy (defined here as changes in the structural budget deficit, caused by policy changes to government spending or taxes) or monetary policy can be used to alter overall spending in the economy. However, there are several important differences to consider between the two.

First, economic conditions change rapidly, and in practice monetary policy can be more nimble than fiscal policy. The Fed meets every six weeks to consider changes in interest rates and can call an unscheduled meeting any time. Large changes to fiscal policy typically occur once a year at most. Once a decision to alter fiscal policy has been made, the proposal must travel through a long and arduous legislative process that can last months before it can become law, whereas monetary policy changes are made instantly.32

Both monetary and fiscal policy measures are thought to take more than a year to achieve their full impact on the economy due to pipeline effects. In the case of monetary policy, interest rates throughout the economy may change rapidly, but it takes longer for economic actors to change their spending patterns in response. For example, in response to a lower interest rate, a business must put together a loan proposal, apply for a loan, receive approval for the loan, and then put the funds to use. In the case of fiscal policy, once legislation has been enacted, it may take some time for authorized spending to be outlaid. An agency must approve projects and select and negotiate with contractors before funds can be released. In the case of transfers or tax cuts, recipients must receive the funds and then alter their private spending patterns before the economy-wide effects are felt. For both monetary and fiscal policy, further rounds of private and public decisionmaking must occur before multiplier or ripple effects are fully felt.

Second, monetary policy is determined based only on the Fed's mandate, whereas fiscal policy is determined based on competing political goals. Fiscal policy changes have macroeconomic implications regardless of whether that was policymakers' primary intent. Political constraints have prevented increases in budget deficits from being fully reversed during expansions. Over the course of the business cycle, aggregate spending in the economy can be expected to be too high as often as it is too low. This means that stabilization policy should be tightened as often as it is loosened, yet increasing the budget deficit has proven to be much more popular than implementing the spending cuts or tax increases necessary to reduce it. As a result, the budget has been in deficit in all but five years since 1961, which has led to an accumulation of federal debt that gives policymakers less leeway to potentially undertake a robust expansionary fiscal policy, if needed, in the future. By contrast, the Fed is more insulated from political pressures, as discussed in the previous section, and experience shows that it is willing to raise or lower interest rates.

Third, the long-run consequences of fiscal and monetary policy differ. Expansionary fiscal policy creates federal debt that must be serviced by future generations. Some of this debt will be "owed to ourselves," but some (presently, about half) will be owed to foreigners. To the extent that expansionary fiscal policy crowds out private investment, it leaves future national income lower than it otherwise would have been.33 Monetary policy does not have this effect on generational equity, although different levels of interest rates will affect borrowers and lenders differently. Furthermore, the government faces a budget constraint that limits the scope of expansionary fiscal policy—it can only issue debt as long as investors believe the debt will be honored, even if economic conditions require larger deficits to restore equilibrium.

Fourth, openness of an economy to highly mobile capital flows changes the relative effectiveness of fiscal and monetary policy. Expansionary fiscal policy would be expected to lead to higher interest rates, all else equal, which would attract foreign capital looking for a higher rate of return, causing the value of the dollar to rise.34 Foreign capital can only enter the United States on net through a trade deficit. Thus, higher foreign capital inflows lead to higher imports, which reduce spending on domestically produced substitutes and lower spending on exports. The increase in the trade deficit would cancel out the expansionary effects of the increase in the budget deficit to some extent (in theory, entirely if capital is perfectly mobile). Expansionary monetary policy would have the opposite effect—lower interest rates would cause capital to flow abroad in search of higher rates of return elsewhere, causing the value of the dollar to fall. Foreign capital outflows would reduce the trade deficit through an increase in spending on exports and domestically produced import substitutes. Thus, foreign capital flows would (tend to) magnify the expansionary effects of monetary policy.35

Fifth, fiscal policy can be targeted to specific recipients. In the case of normal open market operations, monetary policy cannot. This difference could be considered an advantage or a disadvantage. On the one hand, policymakers could target stimulus to aid the sectors of the economy most in need or most likely to respond positively to stimulus. On the other hand, stimulus could be allocated on the basis of political or other noneconomic factors that reduce the macroeconomic effectiveness of the stimulus. As a result, both fiscal and monetary policy have distributional implications, but the latter's are largely incidental whereas the former's can be explicitly chosen.

In cases in which economic activity is extremely depressed, monetary policy may lose some of its effectiveness. When interest rates become extremely low, interest-sensitive spending may no longer be very responsive to further rate cuts. Furthermore, interest rates cannot be lowered below zero so traditional monetary policy is limited by this "zero lower bound." In this scenario, fiscal policy may be more effective. As is discussed in the next section, some argue that the U.S. economy experienced this scenario following the recent financial crisis.

Of course, using monetary and fiscal policy to stabilize the economy are not mutually exclusive policy options. But because of the Fed's independence from Congress and the Administration, the two policy options are not always coordinated. If Congress and the Fed were to choose compatible fiscal and monetary policies, respectively, then the economic effects would be more powerful than if either policy were implemented in isolation. For example, if stimulative monetary and fiscal policies were implemented, the resulting economic stimulus would be larger than if one policy were stimulative and the other were neutral. Alternatively, if Congress and the Fed were to select incompatible policies, these policies could partially negate each other. For example, a stimulative fiscal policy and contractionary monetary policy may end up having little net effect on aggregate demand (although there may be considerable distributional effects). Thus, when fiscal and monetary policymakers disagree in the current system, they can potentially choose policies with the intent of offsetting each other's actions.36 Whether this arrangement is better or worse for the economy depends on what policies are chosen. If one actor chooses inappropriate policies, then the lack of coordination allows the other actor to try to negate its effects.

Unconventional Monetary Policy and the Fed's Balance Sheet during and after the Financial Crisis

The 2007-2009 financial crisis was the worst crisis since the Great Depression, freezing virtually all parts of the financial system. To restore liquidity and stability to financial markets, the Fed responded by taking a series of unprecedented actions that can be divided into three categories.37

The first category involved actions related to the federal funds rate. The Fed reduced interest rates from 5.25% in September 2007 to the zero lower bound in December 2008 for the first time ever to stimulate economic activity.38 The fundamental problem the Fed faced at the zero lower bound was that traditional monetary policy could not provide any further stimulus, yet the severity of the crisis required more stimulus to restore economic normalcy. Its other actions attempted to provide stimulus through other channels. For example, the Fed subsequently made a series of pledges, called forward guidance, to keep future interest rates low. Because long-term rates today depend on market views of future short-term rates, a credible promise by the Fed to keep short-term rates low in the future could potentially lower long-term rates today.

The second category involved actions that provided direct assistance to the financial sector in the Fed's capacity as the lender of last resort. Traditionally, the Fed acted as lender of last resort by making short-term collateralized loans to banks at the discount window. The Fed made discount window loans during the crisis, but it also created a series of emergency facilities that were unlike anything the Fed had done before in its 100-year history. The first facility was introduced in December 2007, and several more were added after the worsening of the crisis in September 2008. Through these facilities, the Fed provided liquidity to nonbank firms for the first time since the Great Depression. In a handful of cases, the Fed also provided assistance to prevent the failure of a specific firm (such as AIG) or facilitate the takeover of a failing firm (such as Bear Stearns), which have been popularly called bailouts. These firms were viewed as too big to fail, meaning that their failure could have exacerbated the overall crisis. The Fed's lender of last resort actions were taken under both the Fed's traditional authority (e.g., lending to banks) and rarely used emergency authority under Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act (12 U.S.C. §343).39

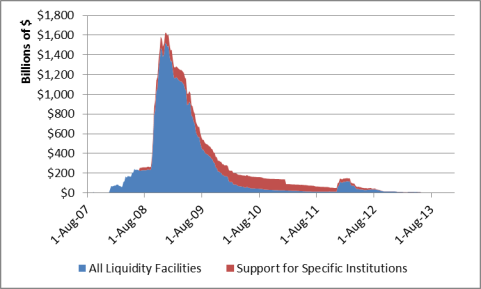

The amount of assistance provided during the crisis was an order of magnitude larger than in normal times, as shown in Figure 1. Total assistance from the Federal Reserve at the beginning of August 2007 was approximately $234 million provided through liquidity facilities, with no direct support given. In mid-December 2008, this number reached a high of $1.6 trillion, with a near-high of $108 billion given in direct support. Once financial stability was restored, most of these programs were wound down relatively quickly.40 Assistance provided through liquidity facilities fell below $100 billion in February 2010, when many facilities were allowed to expire, and support to specific institutions fell below $100 billion in January 2011.41 All outstanding assistance was eventually repaid in full with interest. The last loan from the crisis was repaid on October 29, 2014.42 In 2010, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 111-203) changed Section 13(3) to rule out direct support to specific institutions in the future.

|

Figure 1. Direct Fed Assistance to the Financial Sector (August 1, 2007-December 31, 2013) |

|

|

Source: Fed, Recent Balance Sheet Trends, https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/bst_recenttrends.htm. |

The third category of actions involved large-scale asset purchases. Over three rounds of what was popularly referred to as quantitative easing (QE) between 2009 and 2014, the Fed purchased Treasury securities. Given the role of mortgages at the heart of the financial crisis (and its limited statutory authority), it also purchased mortgage-backed securities and debt issued by the government-sponsored enterprises (Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and the Federal Home Loan Banks) and government agencies (Ginnie Mae). Table 2 summarizes the change in the Fed's securities holdings during the QE programs. In addition, between QE2 and QE3, the Fed initiated the Maturity Extension Program, popularly referred to as Operation Twist. In this program, it replaced short-term securities on its balance sheet with long-term securities. The goal of these actions was to reduce long-term interest rates to provide further stimulus at the zero lower bound. Long-term interest rates were very low over this period, and many studies have tried to tease out the extent to which that should be attributed to QE.43

Table 2. Quantitative Easing (QE):

Changes in Asset Holdings on the Fed's Balance Sheet

(billions of dollars)

|

Treasury Security Holdings |

Agency MBS Holdings |

Agency Debt Holdings |

Total Assets |

|

|

QE1 |

+$302 |

+$1,129 |

+$168 |

+$451 |

|

QE2 |

+$788 |

-$142 |

-$35 |

+$578 |

|

QE3 |

+$810 |

+874 |

-$48 |

+$1,663 |

|

Total |

+$1,987 |

+$1,718 |

+$40 |

+$2,587 |

Source: CRS calculations based on Fed data.

Notes: The first round of QE, QE1, was announced in March 2009. The "QE1" and "total" rows include agency securities and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) that the Fed began purchasing in September 2008 and January 2009, respectively. The final column does not equal the sum of the first three columns because of changes in other items (not shown) on the Fed's balance sheet. The final row does not equal the sum of the first three rows because it includes changes in holdings between the three rounds of QE. The figures in the table are based on actual data, not announced amounts at the onset of the program. The two can differ because of timing and the maturity of prior holdings, which decrease the amounts shown in the table.

The size of actions in the second and third categories can be seen in data on the Fed's balance sheet. Loans and securities are assets on the Fed's balance sheet, so the Fed's balance sheet grew when it made loans and provided other financial assistance during the financial crisis and bought securities under QE. In total, the Fed's balance sheet increased from $0.9 trillion in August 2008 to $4.5 trillion when QE3 ended in October 2014, making it about five times larger than it was before the crisis. The effect this had on the Fed's profits is discussed in the text box below. The increase in the Fed's assets was matched by an equal increase in its liabilities. The two largest liabilities on the Fed's balance sheet are currency (Federal Reserve notes) and bank reserves that banks deposit in their reserve account at the Fed.44 The Fed financed its loans and asset purchases by increasing bank reserves—in essence, "printing money."45 (Reserves increase because when the Fed makes loans or purchases assets, it credits the proceeds to the recipients' reserve accounts at the Fed.) As a result, bank reserves in excess of reserve requirements rose from virtually zero before the financial crisis to over $2.5 trillion at their peak.

The increase in the Fed's balance sheet had the potential to be inflationary because bank reserves are a component of the portion of the money supply controlled by the Fed (called the monetary base), which grew at an unprecedented pace. In practice, overall measures of the money supply did not grow as quickly as the monetary base, and inflation has mostly remained below the Fed's goal of 2% since 2008. The growth in the monetary base did not translate into higher inflation because it did not lead to a commensurate increase in lending or asset purchases by banks.

|

How Has QE Affected the Fed's Profits and the Federal Budget Deficit? The Fed earns interest on its securities holdings, and it uses this interest to fund its operations. (It receives no appropriations from Congress.) The Fed's income exceeds its expenses, and it remits most of its net income to the Treasury, which uses it to reduce the budget deficit. Although the increases in, first, direct lending and, later, holdings of mortgage-related securities increased the potential riskiness of the Fed's balance sheet, it had the ex post facto effect of more than doubling the Fed's net income and remittances to Treasury. Remittances from net income to Treasury rose from $35 billion in 2007 to more than $75 billion annually from 2010 to 2017. However, normalization is likely to continue reducing remittances because of the smaller portfolio holdings and rising costs associated with paying higher interest on bank reserves and reverse repos, with remittances from net income falling to $55 billion in 2019. Although some analysts have raised concerns that the Fed could have negative net income as a result of normalization, the New York Fed is not currently projecting that will occur under various interest-rate and balance-sheet scenarios. Instead, it projects that remittances will decline from the higher levels that have prevailed since the crisis to closer to precrisis levels.46 If the Fed were to generate negative net income, its accounting conventions preclude the possibility of insolvency or transfers from Treasury. |

The "Exit Strategy": Normalization of Monetary Policy after QE

On October 29, 2014, the Fed announced that it would stop making large-scale asset purchases at the end of the month.47 With QE ending, the Fed laid out its plans to normalize monetary policy in a statement in September 2014, also called the "exit strategy."48 In the 2014 announcement, the Fed announced it would continue to implement monetary policy by targeting the federal funds rate.49 The basic challenge to doing so is that the Fed cannot effectively alter the federal funds rate by altering reserve levels (as it did before the crisis) because QE has flooded the market with excess bank reserves. In other words, in the presence of more than $1 trillion in bank reserves, the market-clearing federal funds rate is close to zero even if the Fed would like it to be higher.50

One option to return to normal monetary policy would be to remove the bulk of those excess reserves by shrinking the balance sheet through asset sales. The Fed did not sell any securities during normalization, however.51 From 2014 to 2017, it kept the size of the balance sheet constant at $4.5 trillion by rolling over securities as they matured. In September 2017, it gradually reduced the balance sheet by ceasing to roll over some securities as they mature. At the peak of the runoff, the Fed allowed $30 billion of Treasuries and $20 billion of MBS to run off each month.

The Fed's goal was to reduce the balance sheet until it held "no more securities than necessary to implement monetary policy efficiently and effectively."52 The Fed has stated that a balance sheet that is consistent with this goal will be larger than it was before the crisis. In part, that is because other liabilities on the Fed's balance sheet are larger—there is more currency in circulation now than there was before the crisis, and the Treasury has kept larger balances on average in its account at the Fed. But the balance sheet is also significantly larger because the Fed decided in January 2019 to continue using its new method of targeting the federal funds rate even after normalization is completed.53 Under the new method, the federal funds rate is not determined by supply and demand in the market for bank reserves, and the Fed would prefer to maintain abundant bank reserves so that it does not have to use open market operations to respond to changes in banks' demand for reserves. By contrast, if it had gone back to the pre-crisis method of targeting the federal funds rate, only minimal excess reserve balances would be necessary (but perhaps more than before the crisis), so its balance sheet could have been much smaller.

The Fed ended the balance sheet wind-down in August 2019, but resumed balance sheet growth in September 2019 in response to repo market turmoil (see the section below entitled "The Federal Reserve's Response to Repo Market Turmoil in September 2019"). In August, the size of the balance sheet was about $3.8 trillion, and bank reserves were about $1.5 trillion. Going forward, the Fed will continue to allow $20 billion in MBS to run off the balance sheet each month but will now replace the maturing MBS with Treasury securities instead of allowing the balance sheet to shrink by that amount. Although the Fed has stated that it intends to eventually stop holding MBS, at this rate the Fed would still have sizable MBS holdings in 2025, according to projections from the New York Fed.54

In order to raise the federal funds rate in the presence of large reserves, the Fed has raised the two market interest rates that are close substitutes—it has directly raised the rate it pays banks on reserves held at the Fed and used large-scale reverse repurchase agreements (repos) to alter repo rates.55

In 2008, Congress granted the Fed the authority to pay interest on reserves.56 Because banks can earn interest on excess reserves by lending them in the federal funds market or by depositing them at the Fed, raising the interest rate on bank reserves should also raise the federal funds rate.57 In this way, the Fed can lock up excess liquidity to avoid any potentially inflationary effects because reserves kept at the Fed cannot be put to use by banks to finance activity in the broader economy.58 In practice, because reserves were so abundant, the interest rate that the Fed paid banks on reserves was slightly higher than the actual federal funds rate until 2019, which some have criticized as a subsidy to banks.59

Reverse repos are another tool for draining liquidity from the system and influencing short-term market rates. They drain liquidity from the financial system because cash is transferred from market participants to the Fed. As a result, interest rates in the repo market, one of the largest short-term lending markets, rise. The Fed has long conducted open market operations through the repo market, but since 2013 it has engaged in a much larger volume of reverse repos with a broader range of nonbank counterparties, including the government-sponsored enterprises (such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac) and certain money market funds, through a new Overnight Reverse Repurchase Operations Facility. The Fed is currently not capping the amount of overnight reverse repos offered through this facility. There has been some concern about the potential ramifications of the Fed becoming a dominant participant in this market and expanding its counterparties. For example, will counterparties only be willing to transact with the Fed in a panic, and will the Fed be exposed to counterparty risk with nonbanks that it does not regulate?60

The Federal Reserve's Response to Repo Market Turmoil in September 2019

Repo rates suddenly spiked on September 17, 2019.61 For the day, the average repo rate, as measured by the Secured Overnight Financing Rate, was 5.25%—more than double the average on the previous day. According to media reports, at one point in the day, repo rates hit 10%.62 Because of the interrelationship between the repo market and the federal funds market, the Fed intervened to prevent this spike from leading to an upward movement in the federal funds rate. Nevertheless, the average effective federal funds rate that day rose 0.05 percentage points above the top of the target range.

There is no indication that the recent spike in repo rates was caused by a panic—the markets were not experiencing wider financial disruption and no problems with particular participants were seen. Instead, it was caused by a temporary increase in demand for cash and decrease in supply of bank reserves that have been attributed to three factors. First, federal tax payments were due on September 15. When taxes are paid, money is initially transferred out of the reserve account of the taxpayer's bank into the Treasury's general account at the Fed. Second, relatively large Treasury debt issuance at that time similarly transferred money out of the reserve accounts of banks (who purchased the securities for themselves or customers) and into the Treasury general account. Finally, financial reporting requirements at the end of the third quarter made banks temporarily less willing to lend in the repo market.63 In the words of former New York Fed President Bill Dudley, "the spike ... was not a 'canary in the coal mine' signaling bigger problems in the financial system. Instead, it reflects the difficulty in forecasting the demand for reserves given the changes in regulations."64

Since September 2019, the Fed has responded in two ways to avoid further repo market turmoil. First, since the turmoil began, it has engaged in daily repos, and has pledged to continue to do so at least through April 2020. Second, since October, it has purchased $60 billion in Treasury bills per month, and has pledged to do so at least into the second quarter of 2020. Both achieve the same aim—they increase market liquidity and the supply of bank reserves. Repo rates and the federal funds rate have been stable since the Fed began these operations.

Fed repos outstanding rose from an average of zero the week of September 11, 2019, to $82 billion the week of September 25, 2019, to over $200 billion since the week of October 30. A focus on the Fed's repos only presents one side of the Fed's influence on repo market liquidity and bank reserves, however. The Fed intervenes on both sides of the repo market—that is, it simultaneously injects liquidity into markets by entering into repos and it withdraws liquidity by entering into reverse repos. While the Fed had not used repos from 2009 to September 2019, it had regularly used reverse repos during that period. Since the financial crisis, the Fed has been withdrawing liquidity from repo markets on net because its reverse repos have exceeded its repos. That is still true—despite the liquidity shortfall—even since the Fed's intervention beginning in September 2019.

The reason the Fed's repo activity is still withdrawing liquidity on net is mainly because of the Fed's foreign repo pool, which invests foreign central banks' and international institutions' excess balances held at the Fed in reverse repos with the Fed.65 Note that this service is available to these institutions on demand, so the amount of reverse repos outstanding is determined by the institutions. It is not a tool of monetary policy, but it has the same effect on market liquidity as domestic reverse repos, which are a tool of monetary policy.

Some observers have suggested that regulation played a role in September's repo market turmoil.66 Other observers have disputed the assertion that reforms have created disincentives for large banks to participate in repo markets.67 Specifically, postcrisis financial stability reforms pursuant to Title I of the Dodd-Frank Act and Basel III, an international accord, have required large banks to hold more liquid assets and to hold more capital against loans (i.e., to reduce their leverage).68 Both could potentially raise the cost or reduce the scope for large banks to borrow and lend in repo markets, making participation in repo markets less attractive to them.69 In this sense, such reforms could make banks safer while making financial markets more fragile. But fragility in repo markets of the type experienced in September can be contained as long as the Fed is willing to intervene.

Viewed more broadly, the policy question becomes what mix of monetary policy tools is most appropriate—a question with wider implications than only which tool best delivers interest rate stability. As discussed above, repos were the primary tool for targeting the federal funds rate before the Fed expanded its balance sheet. The main difference since September 2019 was the greater magnitude of the Fed's intervention. A lesser reliance on repos necessitates a larger Fed balance sheet and higher bank reserves, and vice versa, to effectively target the federal funds rate.

The Federal Reserve's Review of Monetary Policy Strategy, Tools, and Communications

In November 2018, the Fed announced a "broad review of the strategy, tools, and communication practices it uses to pursue the monetary policy goals established by the Congress: maximum employment and price stability."70 The mandate itself and the Fed's 2% inflation target are not part of the review. The Fed has been holding town halls with stakeholders and a research conference as part of the review.

According to Chair Powell, one purpose of the review is to evaluate whether changes are needed in how monetary policy is carried out in response to the economic changes that have occurred since the Great Recession.71 For example, inflation is less responsive to changes in unemployment, and the peak federal funds rate is much lower than in the previous nine expansions for which data are available.72 Because the Fed is much closer to the zero lower bound than in previous expansions, it has much less scope to stimulate the economy (if necessary) using reductions in the federal funds rate.

As part of the review, the FOMC has discussed "makeup" strategies as a way to potentially deliver more stimulus given the zero lower bound problem.73 Given the tendency for inflation to undershoot the 2% target during downturns, the idea behind the makeup strategy is to explicitly pledge to deliver an equivalent amount of inflation above 2% at other times, so that inflation will average 2% over the business cycle.74 (It is already Fed policy that the 2% target should be met on average, as opposed to a policy that inflation should be no higher than 2%.75) A challenge to the success of makeup strategies has been the Fed's inability to get inflation to even reach the 2% target in this expansion: If it cannot even deliver 2% inflation, how will it deliver inflation above 2%? Another challenge is that makeup strategies could be hard to communicate to the public and could risk undermining the stability of the public's inflation expectations.

The review is also considering whether there are other tools to provide stimulus that the Fed should use at the zero lower bound besides forward guidance and QE. For example, Vice Chair Richard Clarida noted that some other countries have targeted government bond yields to provide additional stimulus.76

The review is also considering potential changes to how the Fed communicates monetary policy decisions to the public. The review is scheduled to conclude in the first half of 2020.

Appendix. Regulatory Responsibilities

The Fed has distinct roles as a central bank and a regulator. Its main regulatory responsibilities are as follows:

- Bank regulation. The Fed supervises bank holding companies (BHCs) and thrift holding companies (THCs), which include all large and thousands of small depositories, for safety and soundness.77 The Dodd-Frank Act requires the Fed to subject BHCs with more than $50 billion in consolidated assets to enhanced prudential regulation (i.e., stricter standards than are applied to similar firms) in an effort to mitigate the systemic risk they pose.78 The Fed is also the prudential regulator of U.S. branches of foreign banks and state banks that have elected to become members of the Federal Reserve System. Often in concert with the other banking regulators,79 it promulgates rules and supervisory guidelines that apply to banks in areas such as capital adequacy, and examines depository firms under its supervision to ensure that those rules are being followed and those firms are conducting business prudently. The Fed's supervisory authority includes consumer protection for banks under its jurisdiction that have $10 billion or less in assets.80

- Prudential regulation of nonbank systemically important financial institutions. The Dodd-Frank Act allows the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC)81 to designate nonbank financial firms as systemically important (SIFIs). Designated firms are supervised by the Fed for safety and soundness. Since enactment, the number of designated firms has ranged from four, initially, to none today.82

- Regulation of the payment system. The Fed regulates the retail and wholesale payment system for safety and soundness. It also operates parts of the payment system, such as interbank settlements and check clearing.83 The Dodd-Frank Act subjects payment, clearing, and settlement systems designated as systemically important by the FSOC to enhanced supervision by the Fed (along with the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, depending on the type of system).

- Margin requirements. The Fed sets margin requirements on the purchases of certain securities, such as stocks, in certain private transactions. The purpose of margin requirements is to mandate what proportion of the purchase can be made on credit.

The Fed attempts to mitigate systemic risk and prevent financial instability through these regulatory responsibilities, as well as through its lender of last resort activities and participation on the FSOC (whose mandate is to identify risks and respond to emerging threats to financial stability). The Fed has focused more on attempting to mitigate systemic risk through its regulations since the financial crisis, and has also restructured its internal operations to facilitate a macroprudential approach to supervision and regulation.84

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

This report was originally authored by Gail E. Makinen, formerly of the Congressional Research Service.

Footnotes

| 1. |

For background on the makeup of the Federal Reserve, see CRS In Focus IF10054, Introduction to Financial Services: The Federal Reserve, by Marc Labonte. |

| 2. |

Section 2A of the Federal Reserve Act, 12 U.S.C. §225a. |

| 3. |

Federal Reserve, Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy, January 24, 2012, at http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/files/FOMC_LongerRunGoals.pdf. |

| 4. |

Current and past monetary policy announcements can be accessed at http://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomccalendars.htm. For more information on the business cycle, see CRS In Focus IF10411, Introduction to U.S. Economy: The Business Cycle and Growth, by Jeffrey M. Stupak. |

| 5. |

See CRS Insight IN11152, Why Is the Federal Reserve Reducing Interest Rates?, by Marc Labonte. |

| 6. |

For more information, see CRS Report R46200, Recent Slower Economic Growth in the United States: Policy Implications, by Marc Labonte. |

| 7. |

For more information, see CRS Report R44663, Unemployment and Inflation: Implications for Policymaking, by Marc Labonte. |

| 8. |

See CRS Insight IN10971, Escalating U.S. Tariffs: Affected Trade, coordinated by Brock R. Williams. |

| 9. |

Federal Reserve, "Transcript of Chairman Powell's Press Conference," July 31, 2019, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/mediacenter/files/FOMCpresconf20190731.pdf. |

| 10. |

Janet Yellen, "The Federal Reserve's Monetary Policy Toolkit," speech at Jackson Hole, WY, August 26, 2016, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/yellen20160826a.htm. |

| 11. |

Nick Timiraos, "Powell Says Fed Won't Bend to Political Pressure," Wall Street Journal, June 25, 2019, at https://www.wsj.com/articles/feds-powell-trade-uncertainty-global-growth-worries-could-prompt-rate-cuts-11561481986. |

| 12. |

See, for example, John Taylor, "A Monetary Policy for the Future," speech at the International Monetary Fund, April 15, 2015, at http://web.stanford.edu/~johntayl/2015_pdfs/A_Monetary_Policy_For_the_Future-4-15-15.pdf. |

| 13. |

Of the monetary policy tools described below, the board is generally responsible for setting reserve requirements and interest rates paid by the Fed, whereas the federal funds target is set by the FOMC. The discount rate is set by the 12 Federal Reserve banks, subject to the board's approval. In practice, the board and FOMC coordinate the use of these tools to implement a consistent monetary policy stance. The New York Fed determines what open market operations are necessary on an ongoing basis to maintain the federal funds target. |

| 14. |

Depository institutions are obligated by law to hold some fraction of their deposit liabilities as reserves. They are also likely to hold additional or excess reserves based on certain risk assessments they make about their portfolios and liabilities. |

| 15. |

See, for example, Anthony M. Santomero, "Great Expectations: The Role of Beliefs in Economics and Monetary Policy," Business Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Second Quarter 2004, pp. 1-6, and Gordon H. Sellon, Jr., "Expectations and the Monetary Policy Transmission Mechanism," Economic Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Fourth Quarter 2004, pp. 4-42. |

| 16. |

The Fed is legally forbidden from buying securities directly from the Department of the Treasury. Instead, it buys them on secondary markets from primary dealers. For a technical explanation of how open market operations are conducted, see Cheryl L. Edwards, "Open Market Operations in the 1990s," Federal Reserve Bulletin, November 1997, pp. 859-872; and Benjamin Friedman and Kenneth Kuttner, Implementation of Monetary Policy: How Do Central Banks Set Interest Rates?, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper no. 16165, March 2011. |

| 17. |

In addition to open market operations, the Fed has entered into reverse repos since 2013 through a newly created facility, the Overnight Reverse Repurchase Operations Facility. See the section below entitled "The "Exit Strategy": Normalization of Monetary Policy after QE." |

| 18. |

All depository institutions, as defined by 12 U.S.C. §461, may borrow from the discount window and are subject to reserve requirements regardless of whether they are members of the Federal Reserve. |

| 19. |

Until 2003, the discount rate was set slightly below the federal funds target, and the Fed used moral suasion to discourage healthy banks from profiting from this low rate. To reduce the need for moral suasion, lending rules were altered in early 2003. Since that time, the discount rate has been set at a penalty rate above the federal funds rate target. However, during the financial crisis, the Fed encouraged banks to use the discount window. |

| 20. |