Federal Reserve: Emergency Lending

The 2007-2009 financial crisis led the Federal Reserve (Fed) to revive an obscure provision found in Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act (12 U.S.C. 344) to extend credit to nonbank financial firms for the first time since the 1930s. Section 13(3) provides the Fed with greater flexibility than its normal lending authority. Using this authority, the Fed created six broadly based facilities (of which only five were used) to provide liquidity to “primary dealers” (certain large investment firms) and to revive demand for commercial paper and asset-backed securities. More controversially, the Fed provided special, tailored assistance exclusively to four firms that the Fed considered “too big to fail”—AIG, Bear Stearns, Citigroup, and Bank of America.

In response to the financial turmoil caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the Fed reopened four of these broadly-based programs and created two new ones in 2020. Treasury pledged $50 billion of assets from the Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF) to protect the Fed against losses in most of these programs. H.R. 748, referred to by some as the “third coronavirus stimulus” bill, was passed by the Senate on March 25, 2020. The bill would provide between $454 billion and $500 billion to support Fed liquidity facilities. The bill states that applicable requirements of Section 13(3) shall apply to these facilities.

Credit outstanding (extended in the form of cash or securities) authorized by Section 13(3) peaked at $710 billion in November 2008. All credit extended under Section 13(3) during the financial crisis was repaid with interest. Contrary to popular belief, the Fed earned profits of more than $30 billion and did not suffer any losses on transactions authorized by Section 13(3). These transactions exposed the taxpayer to greater risks than traditional discount window lending to banks, however, because in some cases the terms of the programs had fewer safeguards.

The Fed’s use of Section 13(3) in the 2007-2009 crisis raised fundamental policy issues: Should the Fed be lender of last resort to banks only, or to all parts of the financial system? Should the Fed lend to firms that it does not supervise? How much discretion does the Fed need to be able respond to unpredictable financial crises? How can Congress ensure that taxpayers are not exposed to losses? Do the benefits of emergency lending outweigh the costs, including moral hazard? How can Congress ensure that Section 13(3) is not used to “bail out” failing firms? Should the Fed tell Congress and the public to whom it has lent?

The restrictions in Section 13(3) placed few limits on the Fed’s actions in 2008. However, in 2010, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 111-203) added more restrictions to Section 13(3), attempting to ban future assistance to failing firms while maintaining the Fed’s ability to create broadly based facilities. The Dodd-Frank Act also required records for actions taken under Section 13(3) to be publicly released with a lag and required the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to audit those programs. Although Section 13(3) must be used “for the purpose of providing liquidity to the financial system,” some Members of Congress have expressed interest in—while others have expressed opposition to—the Fed using Section 13(3) to assist financially struggling entities, including states, municipalities, and territories of the United States.

Jeb Hensarling, former Chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, contends that “Dodd-Frank tried but failed to rein in the Fed’s emergency lending authority.” Legislation was passed by the House in the 114th Congress (H.R. 3189) and 115th Congress (H.R. 10) that would have further limited the Fed’s authority under Section 13(3). Then-Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen contended that such restrictions would “essentially repeal the Federal Reserve’s remaining ability to act in a crisis.” Current Fed Chairman Jerome Powell opposed further reducing the Fed’s discretion under Section 13(3) on the grounds that the Fed needs “to be able to respond flexibly and nimbly” to threats to financial stability.

Federal Reserve: Emergency Lending

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- History of Section 13(3)

- Use of Section 13(3) in 2020 in Response to COVID-19

- Use of Section 13(3) in 2008

- Broadly Based Facilities

- Special Assistance to Firms Deemed "Too Big to Fail"

- Limits on Emergency Lending

- Restrictions on Emergency Lending in Place in 2008

- Changes in the Dodd-Frank Act

- The Fed's Rule Implementing the Dodd-Frank Act's Changes

- Oversight Requirements

- Policy Issues

- Why Was the Fed Established as a "Lender of Last Resort"?

- Who Should Have Access to the Lender of Last Resort?

- Lending to Nonbank Financial Firms?

- Lending to Nonfinancial Firms?

- Lending to Government or Government Chartered Entities?

- Lending to Itself?

- What Are the Potential Costs of Emergency Assistance?

- How Much Discretion Should the Fed Be Granted?

- What Rate Should the Fed Charge?

- Should Borrowers' Identities Be Kept Confidential?

- Selected Legislation

- 114th Congress

- H.R. 3189

- H.R. 5983

- 115th Congress

- H.R. 10

Figures

Tables

Summary

The 2007-2009 financial crisis led the Federal Reserve (Fed) to revive an obscure provision found in Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act (12 U.S.C. 344) to extend credit to nonbank financial firms for the first time since the 1930s. Section 13(3) provides the Fed with greater flexibility than its normal lending authority. Using this authority, the Fed created six broadly based facilities (of which only five were used) to provide liquidity to "primary dealers" (certain large investment firms) and to revive demand for commercial paper and asset-backed securities. More controversially, the Fed provided special, tailored assistance exclusively to four firms that the Fed considered "too big to fail"—AIG, Bear Stearns, Citigroup, and Bank of America.

In response to the financial turmoil caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the Fed reopened four of these broadly-based programs and created two new ones in 2020. Treasury pledged $50 billion of assets from the Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF) to protect the Fed against losses in most of these programs. H.R. 748, referred to by some as the "third coronavirus stimulus" bill, was passed by the Senate on March 25, 2020. The bill would provide between $454 billion and $500 billion to support Fed liquidity facilities. The bill states that applicable requirements of Section 13(3) shall apply to these facilities.

Credit outstanding (extended in the form of cash or securities) authorized by Section 13(3) peaked at $710 billion in November 2008. All credit extended under Section 13(3) during the financial crisis was repaid with interest. Contrary to popular belief, the Fed earned profits of more than $30 billion and did not suffer any losses on transactions authorized by Section 13(3). These transactions exposed the taxpayer to greater risks than traditional discount window lending to banks, however, because in some cases the terms of the programs had fewer safeguards.

The Fed's use of Section 13(3) in the 2007-2009 crisis raised fundamental policy issues: Should the Fed be lender of last resort to banks only, or to all parts of the financial system? Should the Fed lend to firms that it does not supervise? How much discretion does the Fed need to be able respond to unpredictable financial crises? How can Congress ensure that taxpayers are not exposed to losses? Do the benefits of emergency lending outweigh the costs, including moral hazard? How can Congress ensure that Section 13(3) is not used to "bail out" failing firms? Should the Fed tell Congress and the public to whom it has lent?

The restrictions in Section 13(3) placed few limits on the Fed's actions in 2008. However, in 2010, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 111-203) added more restrictions to Section 13(3), attempting to ban future assistance to failing firms while maintaining the Fed's ability to create broadly based facilities. The Dodd-Frank Act also required records for actions taken under Section 13(3) to be publicly released with a lag and required the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to audit those programs. Although Section 13(3) must be used "for the purpose of providing liquidity to the financial system," some Members of Congress have expressed interest in—while others have expressed opposition to—the Fed using Section 13(3) to assist financially struggling entities, including states, municipalities, and territories of the United States.

Jeb Hensarling, former Chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, contends that "Dodd-Frank tried but failed to rein in the Fed's emergency lending authority." Legislation was passed by the House in the 114th Congress (H.R. 3189) and 115th Congress (H.R. 10) that would have further limited the Fed's authority under Section 13(3). Then-Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen contended that such restrictions would "essentially repeal the Federal Reserve's remaining ability to act in a crisis." Current Fed Chairman Jerome Powell opposed further reducing the Fed's discretion under Section 13(3) on the grounds that the Fed needs "to be able to respond flexibly and nimbly" to threats to financial stability.

Introduction

The financial crisis that began in 2007 and deepened in 2008 was the worst since the Great Depression. The federal policy response was swift, large, creative, and controversial, creating unprecedented tools to grapple with financial instability. Particularly notable were the actions taken by the Federal Reserve (Fed) under its broad emergency lending authority, Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act (12 U.S.C. 344). This obscure section of the act was described in a 2002 review as follows: "To some this lending legacy is likely a harmless anachronism, to others it's still a useful insurance policy, and to others it's a ticking time bomb of political chicanery."1

Using its normal powers, the Fed faces statutory limitations on whom it may lend to, what it may accept as collateral, and for how long it may lend. Because many of the actions it took during the crisis did not meet these limitations, Section 13(3) was used to authorize most of the Fed's emergency facilities created during the crisis to provide credit to nonbank financial firms. More controversially, the Fed also invoked Section 13(3) to prevent the failure of—some would say to "bail out"—Bear Stearns and American International Group (AIG), two financial firms that it deemed "too big to fail." The Federal Reserve also lent extensively to banks through the discount window and newly created facilities and undertook "quantitative easing" (large scale purchases of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities) during the crisis.2 Because these actions were taken under other authorities, they are beyond the scope of this report, as are other actions taken by the federal government during the crisis.3

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (hereinafter, the Dodd-Frank Act; P.L. 111-203) limited the Fed's discretion under Section 13(3), but some Members of Congress believe that these changes were insufficient.

In response to the financial turmoil caused by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the Fed reopened some of these programs in 2020. It has also taken other actions to promote economic activity and financial stability that are not taken under Section 13(3). For an overview of these actions, see CRS Insight IN11259, Federal Reserve: Recent Actions in Response to COVID-19, by Marc Labonte. H.R. 748, referred to by some as the "third coronavirus stimulus" bill, was passed by the Senate on March 25, 2020. The bill would provide between $454 billion and $500 billion to support Fed liquidity facilities. (Of the $500 billion, $46 billion could be used to support specifically identified industries. Any sum that is not spent from this $46 billion could be used to support Fed facilities.) The bill states that applicable requirements of Section 13(3) shall apply to these facilities.

This report provides a review of the history of Section 13(3), including its use in 2008 and 2020. It discusses the Fed's authority under Section 13(3) before and after the Dodd-Frank Act. It then discusses policy issues and previous legislation to amend Section 13(3), including H.R. 3189, which passed the House on November 19, 2015.

History of Section 13(3)

One of the main reasons the Fed was created was to act as a "lender of last resort," by providing liquidity in the form of short-term loans to banks through the discount window. The Fed still provides that service today, but the amount of liquidity extended is insignificant typically. Over time, it became expected that banks would meet their short-term borrowing needs through private markets under normal conditions. Discount window lending to banks occurs under the Fed's normal statutory authority.

Nonbank financial firms also face liquidity needs, but the history of Fed lending to nonbanks is much more limited. Section 13(3) has been invoked rarely since it was enacted in 1932. The Fed used it to make 123 loans to nonfinancial firms totaling $1.5 million from 1932 to 1936, until that authority was superseded by new authority (Section 13b, which was subsequently repealed).4 Section 13(3) can also be used to authorize lending to banks. After 1936, the Fed invoked Section 13(3) occasionally to make nonmember banks and credit unions eligible to borrow at the discount window before 1980, when nonmember banks were permitted to access the discount window.5 Section 13(3) authority was not used to extend credit to nonbanks from 1936 to 2008. This authority was then used extensively beginning in 2008 in response to the financial crisis—in very different ways than it had been used previously.

Use of Section 13(3) in 2020 in Response to COVID-19

In March 2020, the Fed opened six lending facilities using Section 13(3) authority in response to financial disruptions caused by COVID-19 in markets for corporate debt, municipal debt, and nonresidential asset-backed securities:

- Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF). The Fed revived the CPFF, which uses a special purpose vehicle (SPV)6 created and controlled by the Fed to support the commercial paper market.7 Commercial paper is short-term debt issued by financial firms (including banks), nonfinancial firms, and pass-through entities that issue asset-backed securities (ABS). The CPFF purchases newly-issued commercial paper from all types of U.S. issuers who cannot find private sector buyers. Issuers must pay a fee to the Fed, as well as interest on the commercial paper; the interest rate is set at the prevailing three-month overnight index swap rate plus two percentage points. There are limits on how much commercial paper any issuer can sell to the facility, and the commercial paper must receive a relatively high credit rating to be eligible for purchase. The CPFF is currently scheduled to expire in March 2021. Treasury has pledged $10 billion of assets from the Exchange Stabilization Fund to protect the Fed from future losses.

- Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF). The Fed revived the PDCF to provide liquidity to primary dealers,8 a group of large government securities dealers that are market makers in securities markets and are the Fed's traditional counterparties for open market operations.9 The PDCF can be thought of as analogous to a discount window for primary dealers. Loans are made at the Fed's primary credit rate (i.e., the borrowing rate at the discount window), which is currently set at the top of the federal funds target range. Loans are available with maturities ranging from overnight to up to 90 days, with recourse (i.e., loans must still be repaid if collateral is insufficient); and they are fully collateralized, limiting their riskiness. Acceptable collateral includes U.S. Treasuries; government agency debt; investment grade corporate, mortgage-backed, asset-backed, and municipal securities; and certain classes of equities.

- Money Market Fund Liquidity Facility (MMLF). The Fed created the MMLF to make nonrecourse loans to financial institutions to purchase assets that money market funds are selling to meet redemptions.10 This reduces the probability of runs on money market funds caused by a fund's inability to liquidate assets. Only assets sold by prime money market funds or funds that invest in municipal debt are eligible for the MMLF. Securities eligible for purchase include U.S. Treasuries; securities issued by government agencies or government-sponsored enterprises; highly rated municipal debt that matures in less than 12 months; and highly rated commercial paper. The Fed earns interest on the loans (at the prime credit rate for Treasury, government agency, or government sponsored debt, plus an additional 0.25 percentage points for municipal debt, and an additional one percentage point for commercial paper) but bears the risk that the security will decline below the value of the loan. On March 19, 2020, the banking regulators issued an interim final rule so that these loans would not affect the borrowing bank's compliance with regulatory capital requirements.11

- Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility (PMCCF) and Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF). The Fed created two new facilities to support corporate bond markets—the PMCCF to purchase newly issued corporate debt from issuers and the SMCCF to purchase existing corporate debt or corporate debt exchange-traded funds on secondary markets.12 Both facilities will purchase debt through an SPV. Both facilities can only purchase debt that is investment grade or issued by investment-grade issuers. The issuer must have material operations in the United States and cannot receive direct federal financial assistance related to COVID-19. For the SMCCF, bonds will be purchased at fair market value and must mature in five years or less. For the PMCCF, interest rates will be "informed by market rates," and borrowers will pay a one percentage point commitment fee. The borrower may call any bond at par in the future, enabling the facility to wind down more quickly if financial conditions normalize. Both programs are currently scheduled to terminate at the end of September 2020.

- Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF). The Fed revived the TALF to make nonrecourse, three-year loans to private investors through a SPV to purchase newly issued, highly rated ABS backed by various nonmortgage loans.13 Eligible ABS include those backed by certain auto loans, student loans, credit card receivables, equipment loans, floorplan loans, insurance premium finance loans, small business loans guaranteed by the Small Business Administration, or servicing advance receivables. Any company with an account with a primary dealer would be eligible for a TALF loan. Borrowers would pay an interest rate that would be one or two percentage points above a LIBOR swap rate and a fee equal to 0.1% of the loan amount. The Fed bears the risk that the value of the ABS falls below the loan amount plus a haircut. Borrowers may prepay the loan. The program is currently scheduled to terminate at the end of September 2020.

The CPFF, PDCF, and TALF are very similar to the 2008 facilities discussed below. The MMLF is very similar to the 2008 Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (AMLF) but accepts a wider range of collateral than the AMLF accepted in 2008. The PMCCF and SMCCF are unlike any 2008 facilities.

The potential size of these programs is generally limited only by participants' pre-crisis borrowing patterns; the Fed has virtually unlimited ability to fund them. The risk posed to the Fed (and ultimately, the taxpayer) through these facilities is hard to quantify given the uncertainty surrounding COVID-19, but risk is mitigated because the credit is collateralized and borrowers must qualify based on terms such as credit ratings. In addition, Treasury has pledged $10 billion of assets from the Exchange Stabilization Fund for each of these facilities except the PDCF to protect the Fed from future losses—although these losses would still be borne by the federal government.14 Each facility was approved by the Treasury Secretary.

Amounts outstanding through 13(3) programs are reported weekly on the Fed's balance sheet.15 More detailed information is provided in the Fed's Quarterly Report on Federal Reserve Balance Sheet Developments.16 The Dodd-Frank Act requires the Fed to provide the congressional committees of jurisdiction with details of all transactions, including amounts and the identities of borrowers, within 7 days of the program's creation and with updates every 30 days thereafter. In addition, the Dodd-Frank Act requires transaction details to be publicly disclosed one year after the facility is closed.17 See the section below entitled "Oversight Requirements" for more details.

Use of Section 13(3) in 2008

Section 13(3) was used to authorize multiple actions taken by the Fed when financial conditions worsened at two points in 2008—around the time the investment bank Bear Stearns experienced difficulties in March and following the failure of the investment bank Lehman Brothers in September. Credit extended under Section 13(3) in 2008 can be divided into two broad categories:

- 1. broadly based facilities to address liquidity problems in specific markets and

- 2. exclusive, tailored assistance to prevent the disorderly failure of individual firms deemed too big to fail.18

Credit outstanding (in the form of cash or securities) under Section 13(3) peaked at $710 billion in November 2008.19 Currently, all credit extended under Section 13(3) has been repaid with interest and all 13(3) facilities have expired.20 Contrary to popular belief, the Fed did not suffer any losses on transactions taken under Section 13(3) and earned profits of more than $30 billion (more than half of which is AIG21 related).22 Nevertheless, some of these transactions exposed the taxpayer to greater ex ante risks than the discount window because the terms of the programs had fewer safeguards—in some cases involving nonrecourse loans23 and troubled asset purchases, for example. The next two sections summarize this experience, with more detail provided in the Appendix.24

|

Lessons From the 2008 Experience As this report discusses, the 2008 experience with 13(3) facilities yields a few insights that may be applicable to its use in 2020.

|

Broadly Based Facilities

The Fed created six broadly based facilities under Section 13(3) in 2008 to extend credit to all eligible borrowers within a particular class of nonbank financial firms or to a particular segment of financial markets:

- Term Securities Lending Facility (TSLF) and Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF). The TSLF and PDCF were created to assist primary dealers. The Fed made short-term loans through the PDCF and TSLF to primary dealers to ensure that other primary dealers did not experience liquidity crises in the wake of the primary dealer Bear Stearns's financial difficulties.

- Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (AMLF), Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF), and Money Market Investor Funding Facility (MMIFF). The AMLF, CPFF, and MMIFF were created to support the commercial paper market (the MMIFF was never used). The Fed set up its commercial paper facilities after a run on money market mutual funds forced the latter to contract their large holdings of commercial paper.

- Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF). The TALF was created to support the ABS market. Through TALF, the Fed made three- and five-year loans to private investors to encourage them to purchase ABS other than residential mortgage-backed securities (MBS).26 ABS are an alternative way that banks and nonbanks finance loans to consumers and businesses, and they are often referred to as a form of shadow banking—activities that substitute for traditional bank lending and deposit-taking.27 The decline in the value and liquidity of ABS during the crisis resulted in a sharp contraction in their issuance, reducing the credit available to households and businesses.

Table 1 provides a summary of the terms and uses of these facilities. All the facilities except for TALF were used to provide short-term liquidity—conceptually comparable to the role of the discount window. The CPFF was the largest facility, and TALF was the smallest. As can be seen in the table, none of these facilities extended credit after 2010.

|

Usage |

Terms and Conditions |

|||||||

|

Facility |

Loans Outstanding at Peak |

Total Income |

Number of Participants |

Lending Rate/Fee |

Recourse/ |

Term |

Date Announced-Expired |

|

|

Term Securities Lending Facility (TSLF) |

$235.5 billion |

$0.8 billion |

18 |

Set at auction, with minimum fee of 10 to 25 basis points |

Yes/Yes |

28 days |

Mar. 11, 2008-Feb. 1, 2010 |

|

|

Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF) |

$146.6 billion |

$0.6 billion |

18 |

Rate set equal to Fed's discount rate; fees of up to 40 basis points for frequent users |

Yes/Yes |

overnight |

Mar. 16, 2008-Feb. 1, 2010 |

|

|

Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (AMLF) |

$152.1 billion |

$0.5 billion |

11 from 7 bank holding companies |

Fed's discount rate |

No/No |

120 or 270 days |

Sept. 19, 2008-Feb. 1, 2010 |

|

|

Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF) |

$348.2 billion on Jan. 21, 2009 |

$6.1 billion |

120 |

Markups of 100 to 300 basis points over overnight index swap rate; fees of 10 to 100 basis points |

No/No |

90 days |

Oct. 7, 2008-Feb. 1, 2010 |

|

|

Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF) |

$48.2 billion |

$1.6 billion |

177 |

Various markups over LIBOR or federal funds rate; 10 to 20 basis point administrative fee |

No/Yes |

5 years for CMBS, 3 years for other |

Nov. 25, 2008- Mar. 31, 2010 (June 30, 2010, for new CMBS) |

|

Sources: Federal Reserve, Office of the Inspector General, The Federal Reserve's Section 13(3) Lending Facilities to Support Overall Market Liquidity, November 2010; Federal Reserve, Quarterly Report on Federal Reserve Balance Sheet Developments, various dates. U.S. Government Accountability Office, Federal Reserve System: Opportunities Exist to Strengthen Policies and Processes for Managing Emergency Assistance, GAO-11-696, July 21, 2011.

Notes: Expiration date for facilities marks date after which no new activities were authorized. For some facilities, existing loans remained outstanding after the expiration date. Some facilities did not begin operations on the date announced. Recourse only includes to participant's assets; the Fed had recourse for AMLF and TALF only in the case of material misrepresentation.

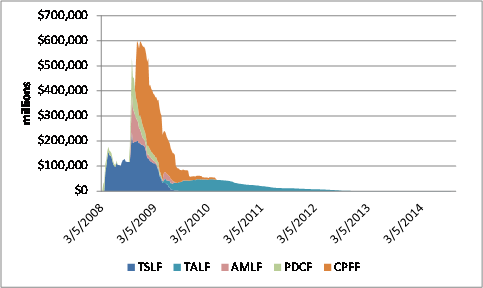

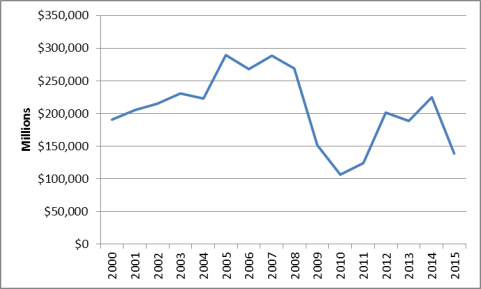

Figure 1 plots loans outstanding for these five facilities from March 2008, when the first facility was created, to October 2014, when the last loan was repaid. Usage of the facilities spiked beginning in mid-September 2008, peaked in December 2008, and then tapered off relatively quickly in 2009 as financial conditions stabilized. From 2010 to 2014, there were only residual amounts of credit outstanding through TALF. According to GAO, use of the facilities was relatively concentrated among a small number of borrowers—which may reflect concentration in those markets.28

|

Figure 1. Loans Outstanding Under Broadly Based Facilities (March 2008-October 2014) |

|

|

Source: Federal Reserve, H.4.1 release, various dates. Notes: For TSLF, lending took the form of Treasury securities. For CPFF, commercial paper was purchased. For other facilities, lending took the form of cash. See Appendix for details. |

Special Assistance to Firms Deemed "Too Big to Fail"

Section 13(3) was also invoked to provide exclusive, tailored assistance to prevent the disorderly failure of four large financial firms on an ad hoc basis:

- In March 2008, the Fed assisted JP Morgan Chase's takeover of Bear Stearns to prevent the latter's failure. Assistance was provided through first, a short-term bridge loan and then, the purchase of Bear Stearns troubled assets, financed through a $29 billion Fed loan;

- In September 2008, the Fed prevented AIG's failure by initially providing it a line of credit of $85 billion. The assistance was restructured several times, with the loan eventually replaced by a Fed pledge to purchase up to $52.5 billion in troubled assets in November (and the rest of the assistance shifted to Treasury);

- In November 2008, the Fed, Treasury, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Cooperation (FDIC) announced a joint agreement to guarantee a more than $300 billion portfolio of Citigroup's troubled assets;

- In January 2009, the Fed, Treasury, and FDIC announced a joint agreement to guarantee a $118 billion portfolio of Bank of America's troubled assets to assist its takeover of Merrill Lynch. (The agreement was never finalized.)

These actions were motivated by concerns that the failure of any of these firms would increase financial instability—in other words, the Fed viewed the firms as too big to fail or too interconnected to fail.29 In all four cases, the Fed did not limit its action to those of a traditional lender of last resort because problems at the firms were not limited to a need for short-term liquidity. In the Fed's view, the firms were not insolvent, but were vulnerable to losing access to funding markets which could cause their failure.30 An evaluation of whether these four institutions were solvent at the time was hampered by the "fog of war"—the Fed was forced to judge their solvency hastily in the context of a crisis, in which the value of all assets was rapidly declining and it was uncertain whether the decline was temporary or permanent. While some have described this assistance as a bail out of failing firms, in all four cases, there was not clear evidence that the firms were insolvent in the classic sense.31 In the case of Bear Stearns, JP Morgan Chase was willing to pay more to acquire it than the value of the Fed's assistance, but later reported losses related to the transaction.32 The other three firms all eventually returned to profitability once the crisis had ended, which means they may or may not have been solvent at the time of the intervention.

As notable as whom the Fed assisted is whom it chose not to assist—Lehman Brothers. Although Lehman Brothers was an investment firm similar to Bear Stearns, the Fed chose not to help facilitate its takeover by Barclays. Instead, Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy. Then-Chairman Bernanke later testified that the Fed declined to assist Lehman Brothers because it held inadequate collateral33—although some of the Fed's other interventions under Section 13(3) featured concerns about inadequate collateral. While one cannot say what would have happened in the counterexample where the Fed had assisted Lehman Brothers, Lehman Brothers' failure marked the worsening of the financial crisis.

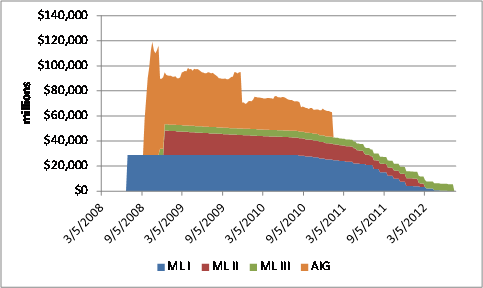

Troubled assets were purchased from Bear Stearns and AIG through three limited liability corporations (LLCs) created and controlled by the Fed named Maiden Lane. Figure 2 shows loans outstanding to the Maiden Lanes and directly to AIG. The direct loan to AIG was paid off in 2011. The asset holdings and loans of the Maiden Lanes tapered off slowly until 2011, when the pace accelerated. The final Maiden Lane loan was fully repaid in 2012; final profits to the Fed will not be known until residual asset holdings are extinguished. Although Citigroup and Bank of America were banks, this assistance was nevertheless authorized under Section 13(3) because it took the form of asset guarantees. The guarantees to Citigroup and Bank of America are not shown in Figure 2 because Fed funds were never extended under those guarantees.

|

|

Source: Federal Reserve, H.4.1 release, various dates. Notes: ML I = Maiden Lane I, facility to assist the takeover of Bear Stearns; ML II = Maiden Lane II, facility to assist AIG; ML III = Maiden Lane III, facility to assist AIG; AIG = direct loan from Fed to AIG. Funds were never extended under asset guarantee to Citigroup and Bank of America. |

Limits on Emergency Lending

Under normal authority, the Fed faces statutory limitations on whom it may lend to, what it may accept as collateral, and for how long it may lend.34 If the Fed wishes to extend credit that does not meet these criteria, it can initiate assistance under Section 13(3).

Restrictions on Emergency Lending in Place in 2008

Section 13(3) was not in the original Federal Reserve Act of 1913; it was added in 1932 (47 Stat 715). Until the Dodd-Frank Act, the authority was very broad, with few limitations. It required that35

- at least five of the seven Fed governors find that there are "unusual and exigent circumstances"36—while this phrase has no specific legal definition, it implies that financial conditions are not normal;37

- the Fed may "discount (for) any individual, partnership, or corporation"—that is, assistance should take the form of a loan, and the loan may be made to private individuals or businesses;

- the borrower must present "notes, drafts, and bills of exchange endorsed or otherwise secured to the satisfaction of the Federal Reserve Bank"—that is, the loan must be backed by collateral approved by the Fed;38

- the Fed shall charge an interest rate consistent with the same limitations applied to the discount window;39 and

- "the Federal Reserve Bank shall obtain evidence that such individual, partnership, or corporation is unable to secure adequate credit accommodations from other banking institutions"—that is, there must be evidence that the borrower does not have private alternatives.

These restrictions did not prevent the Fed from taking several unorthodox actions in 2008. Notably, in some cases, "In form, these transactions were structured as loans. But in substance, they permitted the Fed to move assets off the balance sheets of these institutions and onto its own."40 In the cases of AIG and Bear Stearns, the Fed purchased their assets through limited liability corporations that it created and controlled (called Maiden Lane I, II, and III). This structure allowed the Fed to comply with Section 13(3) because the asset purchases were financed through loans from the Fed to the Maiden Lanes. The loans were backed by those assets and were eventually repaid when the assets were sold off or matured.41 In the cases of Citigroup and Bank of America, the firms were offered a guarantee in the event that they suffered losses on a portfolio of assets, structured as a loan "provided ... on a nonrecourse basis, except with respect to interest payments and fees."42 The Fed also made a loan directly to AIG backed by the company's general assets, meaning there were no specific securities pledged in the event of nonpayment.43 Furthermore, the Fed has interpreted "unusual and exigent circumstances" to mean that assistance should be temporary, but routinely extended each facility's expiration date until demand for credit had waned.

One statutory revision to Section 13(3) affected the Fed's actions in 2008. In 1991, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act (P.L. 102-242; 12 U.S.C. 1811) contained a provision that removed the requirement that collateral be "of the kind and maturities made eligible for discount for member banks" at the discount window. According to the sponsor, Senator Christopher Dodd, the rationale for the provision was to enable the Fed "to make fully secured loans to securities firms in instances similar to the 1987 stock market crash."44 Securities firms, it was argued, would not necessarily hold the same sort of assets that banks used as collateral at the discount window. By removing this language, the Fed had discretion to lend against a broader array of assets.

Changes in the Dodd-Frank Act

Concerns in Congress about some of the Fed's actions under Section 13(3) during the financial crisis led to the section's amendment in Section 1101 of the Dodd-Frank Act. Generally, the intention of the provision in the Dodd-Frank Act was to prevent the Fed from bailing out failing firms while preserving enough of its discretion that it could still create broadly based facilities to address unpredictable market-access problems during a crisis.45 Specifically, the Dodd-Frank Act

- replaced "individual, partnership, or corporation" with "participant in any program or facility with broad-based eligibility";

- required that assistance be "for the purpose of providing liquidity to the financial system, and not to aid a failing financial company." It ruled out lending to an insolvent firm, defined as in any bankruptcy, resolution, or insolvency proceeding;

- required that loans be secured "sufficient(ly) to protect taxpayers from losses," and that collateral be assigned a "lendable value" that is "consistent with sound risk management practices";

- forbade "a program or facility that is structured to remove assets from the balance sheet of a single and specific company";

- required any program "to be terminated in a timely and orderly fashion"; and

- required the "prior approval of the Secretary of the Treasury."46

Proponents of the Dodd-Frank Act believed that the Fed's authority to provide assistance to too big to fail firms was no longer necessary because of other changes in the act. The Fed justified its special assistance to too big to fail firms during the crisis on the grounds that these firms could not be wound down without causing financial instability under existing law because of perceived shortcomings of the bankruptcy process. Fed officials called for the creation of a resolution regime for non-banks modeled on the FDIC's bank resolution regime so that such assistance would not be necessary in the future.47 Title II of the Dodd-Frank Act created such a regime, called the "Orderly Liquidation Authority."48 While critics oppose Title II for reasons beyond the scope of this report, proponents of the Dodd-Frank Act argue that eliminating the Fed's ability to prevent firms from failing under Section 13(3) will not result in financial instability now that firms can undergo an orderly resolution under Title II. According to Ben Bernanke, chairman of the Fed during the financial crisis, "With the creation of the [orderly] liquidation authority, the ability of the Fed to make loans to individual troubled firms like Bear [Stearns] and AIG was no longer needed and, appropriately, was eliminated."49

The Fed's Rule Implementing the Dodd-Frank Act's Changes

As Section 13(3) can be used only in "unusual and exigent circumstances" and had not been used for decades, the Fed had not promulgated a rule governing its use as of 2008, even though it had the discretion to do so. The Dodd-Frank Act also required the Fed to promulgate a rule implementing Section 1101 "as soon as is practicable," and the Fed issued a proposed rule doing so in 2013.50 Some public comments criticized the rule for not adding meaningful quantitative or qualitative definitions to the terms "unusual and exigent circumstances," collateral, penalty rate, insolvency, broadly based, or the duration of assistance.51 Generally, critics believe that the vagueness of the rule is undesirable for the same reason that proponents view it as desirable—because it maximize the Fed's future discretion.52

On December 18, 2015, the Fed promulgated a final rule implementing Section 1101.53 Compared with the proposed rule, the final rule provided more specificity as to how the Fed would comply with the Dodd-Frank Act's requirements, and thus gives the Fed less discretion. For example, the final rule requires lending to be at a "penalty rate," which it defines as a premium to the market rate prevailing in normal circumstances. In some cases, the final rule goes beyond the statutory requirements. For example, statute only prohibits lending to firms that are in a bankruptcy or insolvency proceeding, whereas the final rule also prohibits lending to any facility unless it is open to at least five eligible borrowers, any recipient who has not been current on its debt over the past 90 days, a healthy firm for the purposes of preventing a third party from failing (as was the case with JP Morgan Chase and Bear Stearns), and a firm so that it can avoid bankruptcy or resolution. Table 2 explains how the final rule implements the major provisions of Section 13(3).

Table 2. Major Provisions of the Fed's Final Rule Implementing Dodd-Frank Act Changes to Section 13(3)

|

Section 13(3) Provision |

Final Rule Implementation |

|

Limits assistance to any "participant in any program or facility with broad-based eligibility." |

Minimum of five eligible participants for a program to meet the "broad-based eligibility" requirement. |

|

Specifies that assistance be "for the purpose of providing liquidity to the financial system, and not to aid a failing financial company." Requires that regulations preclude insolvent borrowers, i.e., borrowers "in bankruptcy, resolution ... or any other Federal or State insolvency proceeding." |

Specifies that liquidity may be provided only to an identifiable market or sector of the financial system. Provides that a program may not be used for a firm to avoid bankruptcy or resolution. Specifies that a program designed to aid one or more failing companies or to assist one or more companies to avoid bankruptcy, resolution, or insolvency will not be considered to have the required "broad-based eligibility." Requires borrowers be current on their debt for 90 days before borrowing. Permits the Fed to determine whether the applicant is insolvent. Excludes a firm from borrowing from Fed if the purpose is to help a third-party firm that is insolvent. Includes immediate repayment and enforcement actions for firms that "make[s] a willful misrepresentation regarding its solvency." Specifies that the Fed is under no obligation to extend credit to a borrower. |

|

Requires that loans be secured "sufficient[ly] to protect taxpayers from losses," and collateral be assigned a "lendable value" that is "consistent with sound risk management practices." |

Requires that the Fed assign a lendable value to collateral at the time credit is extended. |

|

Forbids "a program or facility that is structured to remove assets from the balance sheet of a single and specific company." |

Prohibits removing assets from one or more firms that meet the rule's definition of failing. |

|

Requires "prior approval of the Secretary of the Treasury." |

Specifies that no program may be established without the approval of the Secretary of the Treasury. |

|

Specifies that the authority may be invoked only in "unusual and exigent circumstances" and that any program be "terminated in a timely and orderly fashion." |

Requires that the Fed provide "a description of the unusual and exigent circumstances that exist" no later than 7 days after establishing a program. Requires that initial credit terminate within one year, with extension possible only upon a vote of five governors and approval by the Secretary of the Treasury. Requires a review of programs every six months to assure timely termination. |

|

Specifies that rates be consistent with the statutory requirements governing the discount rate.a |

Requires the rate charged must be a "penalty rate," defined as a rate that is a premium to the market rate in normal circumstances. It must also be a rate that "affords liquidity in unusual and exigent circumstances; and ... encourages repayment of the credit and discourages use of the program" when "economic conditions normalize." Permits the charging of "any fees, penalties,...or other consideration...to protect and appropriately compensate the taxpayer.... " |

|

Specifies that the borrower must be "unable to secure adequate credit accommodations from other banking institutions."a |

Requires evidence of inability of participants in a program to obtain credit. The evidence may be based on economic conditions in a particular market or markets; on the borrower's certification of its inability "to secure adequate credit accommodations from other banking institutions," or on "other evidence from participants or other sources." |

Source: CRS based on Federal Reserve, "Extensions of Credit by Federal Reserve Banks," 80 Federal Register 78959, December 18, 2015, available at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2015-12-18/pdf/2015-30584.pdf.

Oversight Requirements

Following the use of Section 13(3) in 2008, three laws have been enacted affecting congressional oversight of emergency lending.

First, in 2008, Section 129 of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act (P.L. 110-343) required the Fed to report to the congressional committees of jurisdiction on the terms of and justification for assistance within seven days of providing assistance under Section 13(3), with updates every 60 days.54

Second, in 2009, an amendment to the Helping Families Save Their Homes Act (Section 801 of P.L. 111-22) included a provision that allows Government Accountability Office (GAO) audits of "any action taken by the Board under ... Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act with respect to a single and specific partnership or corporation." This provision allowed GAO audits of the Maiden Lane facilities and the asset guarantees of Citigroup and Bank of America, but it maintained audit restrictions on non-emergency activities and the broadly based emergency lending facilities.

Third, Section 1101 of the Dodd-Frank Act required that details on the assistance provided under Section 13(3) be reported to the committees of jurisdiction within seven days, with regular updates. Section 1103 required lending records (including details on the identity of the borrower and the terms of the loan) from the crisis to be publicly released on December 1, 2010,55 and lending records from future programs created under Section 13(3) to be publicly released a year after the facility was terminated or two years after lending ceased, whichever came first. Section 1102 allowed GAO to audit any action under Section 13(3) for operational integrity, accounting, financial reporting, internal controls, effectiveness of collateral policies, favoritism, and use of third-party contractors—but did not allow GAO to conduct an economic evaluation—and Section 1109 required GAO to conduct an audit of all Fed emergency facilities created between December 2007 and enactment.56 GAO may not disclose confidential information until the lending records are released.

For more details, see CRS Report R42079, Federal Reserve: Oversight and Disclosure Issues, by Marc Labonte.

Policy Issues

Why Was the Fed Established as a "Lender of Last Resort"?

Economists distinguish between liquidity problems and solvency problems facing financial firms. Firms become insolvent when their assets are worth less than their liabilities (e.g., because their assets have fallen in value). Liquidity (i.e., cash flow) problems arise because of the maturity mismatch between a financial firm's long-term assets and short-term liabilities. In any instance where such a mismatch exists, no matter how much liquidity the firm holds, a firm is vulnerable to a loss of liquidity if it cannot roll over its short-term liabilities—even if the firm is solvent. In a crisis, creditors are unable to distinguish between solvent and insolvent firms, so both lose access to liquidity. The classic example of a liquidity crisis is a bank run, in which depositors withdraw their deposits (liabilities) and banks cannot liquidate loans (assets) to meet withdrawals. Holding more cash and fewer loans would make a run less likely but could not completely prevent it, and the unintended consequence would be that loans would be more expensive to customers. The Fed was created as a lender of last resort with this scenario in mind—when its depositors withdrew funds, a bank would be able to pledge its assets at the Fed's discount window in exchange for short-term loans. Because the Fed controls the money supply, it is in a unique position to potentially provide unlimited liquidity. This position enhances its ability to credibly pledge to end financial crises. Given that the Fed can only address liquidity problems, it is not equipped to address solvency problems or crises resulting from solvency problems, however.

One alternative to the Fed acting as a lender of last resort in a crisis is to allow the panic to run its course. This was the approach followed in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, until repeated panics resulted in the creation of the Fed. Eventually the panic would subside, but crises can lead to significant contractions in real economic activity and declines in prices. Crises cause economic contractions because financial firms extend less credit to consumers and businesses to hoard liquidity.

Who Should Have Access to the Lender of Last Resort?

Lending to Nonbank Financial Firms?

Do nonbank financial firms also face liquidity problems, and does this justify the Fed's emergency authority? Although only banks accept deposits, many types of financial firms face a maturity mismatch between long-term assets and short-term liabilities. As a result, many types of financial firms are vulnerable to liquidity crises. In 2008, the availability of repurchase agreements (repos) and commercial paper—two prominent types of short-term lending for nonbanks—sharply and suddenly contracted, causing liquidity problems for banks and nonfinancial firms. Thus, some nonbank financial firms could also benefit from access to Fed lending in a liquidity crisis.

Although some nonbank firms could benefit from access to a lender of last resort, policymakers might decide to grant them access only if there is some wider societal benefit to doing so. Such benefits could be because a failure to do so would result in financial instability, through spillover effects (e.g., counterparty exposure), contagion, or the disruption of critical functions within the financial system. Banks provide critical functions through their unique role in the payment system, for example. Nonbanks do not play a similar role in the payment system, although they are important participants in similar markets, such as the repo market, that might also be viewed as critical.57

Before 2008, there was some debate about whether nonbank financial firms were systemically important enough that there would be widespread repercussions if they faced a crisis. Likewise, there was some debate about whether a nonbank crisis would significantly affect the availability of credit to consumers and businesses. Over time, the nonbank financial sector has grown in absolute terms and relative to banks. The 2008 experience suggests that a nonbank crisis can be damaging to the availability of credit and the broader financial sector. Thus, the rationale of having a lender of last resort to provide liquidity also extends to parts of the nonbank financial system, although the policy tradeoffs may be different. This raises the question of whether there should be disparate treatment of banks and nonbanks—banks receive continual access to the discount window, whereas any given nonbank receives no access to the Fed in normal conditions and uncertain access to the Fed in unusual and exigent circumstances. Should nonbanks be allowed to be members of the Federal Reserve system to ensure access to the discount window?58 If so, should they be subject to prudential supervision by the Fed?59

Not all uses of Section 13(3) during the crisis were for the purpose of providing short-term liquidity, however. TALF loans had terms of three to five years and were intended to revive long-term consumer and business credit (by increasing the demand for ABS, which might be described as increasing their liquidity). The AIG loan initially had a maturity of two years. The Maiden Lane facilities set up for Bear Stearns and AIG and the asset guarantees for Citigroup and Bank of America were all intended to help those firms with troubled assets. The Dodd-Frank Act now requires that assistance provided under Section 13(3) be "for the purpose of providing liquidity to the financial system, and not to aid a failing financial company."

Lending to Nonfinancial Firms?

Another issue is whether Section 13(3) should ever be used to provide credit to nonfinancial firms. In 2008, the Fed chose to use Section 13(3) to provide credit mainly to financial firms, although nonfinancial firms were eligible to sell their commercial paper to the CPFF. The Dodd-Frank Act limits actions under Section 13(3) to providing liquidity to the financial system, but does not limit participants to financial firms. In the 1930s, emergency loans were made to nonfinancial firms. Although nonfinancial firms might also have liquidity needs,60 they do not generally face the maturity mismatch that makes liquidity risk inherent to financial firms. Liquidity problems at nonfinancial firms may also pose less systemic risk than at financial firms because they are less interconnected with the financial system and do not perform critical functions in the financial system.

The advantage of providing long-term credit to nonfinancial firms is that it directly stimulates physical capital investment spending on plant and equipment, which in turn directly stimulates gross domestic product (GDP). A disadvantage is that it is more likely to put the Fed in the position of "picking winners", and the Fed has no expertise in evaluating the creditworthiness of loan proposals. Another disadvantage is the potential that the Fed's lending will "crowd out" private capital. In a liquidity crisis, when the availability of private lending, by definition, is constrained, the likelihood that Fed lending comes at the expense of private lending is lower. By contrast, long-term credit, which will outlast a liquidity crisis, has a greater potential for crowding out.

Lending to Government or Government Chartered Entities?

Another category of firms that Congress might consider whether it wants to make ineligible for assistance under Section 13(3) is entities associated with the government, such as government agencies, government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs), or bridge banks created in an FDIC resolution.61 Some Members of Congress have also expressed concern that Section 13(3) could be used to assist state or municipal governments. The Fed has never used Section 13(3) for these purposes, although it has purchased agency and GSE debt under its normal authority. Current statute does not explicitly rule it out, although such an action might have trouble meeting the statute's various requirements, such as that the facility be broadly based for the purpose of providing liquidity to the financial system.

Lending to Itself?

During the crisis, the Fed structured many of its transactions under Section 13(3) as loans to an LLC or SPV that it created and controlled. It did so to comply with the Section 13(3) requirement that assistance take the form of a loan. For example, in 2008, the Fed created the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF) to purchase commercial paper, a debt security that is economically equivalent to a short-term loan from the borrower's perspective. In this case, the Fed was able to purchase commercial paper by setting up an SPV that it controlled and lending the SPV funds to finance the purchases. Some of the commercial paper the CPFF purchased was not collateralized, however, so it was not economically equivalent to a collateralized loan.

These actions raise two policy issues. First, should Section 13(3) be restricted so that the Fed cannot lend to SPVs or LLCs it creates and controls? Second, should Section 13(3) be modified so that the Fed can provide short-term liquidity by purchasing debt securities?62

From an economic perspective, whether a company accesses short-term liquidity by taking out a loan or issuing a debt security does not change its purpose. On practical grounds, since financial firms increasingly rely on debt securities for liquidity needs, allowing the Fed to purchase them would make it a more effective lender of last resort. But allowing the Fed to purchase securities (directly or through SPVs or LLCs it controls) to provide short-term liquidity faces the "slippery slope" problem. The Fed also used LLCs in the Maiden Lanes case, where the goal was not to provide short-term liquidity but to remove troubled assets from a firm's balance sheet. The Dodd-Frank Act maintained the Fed's ability to create SPVs or LLCs, but prohibits "a program or facility that is structured to remove assets from the balance sheet of a single and specific company." It might be difficult to draw a bright line between debt securities purchased for liquidity purposes and other types of securities.

What Are the Potential Costs of Emergency Assistance?

Potential costs inherent in Section 13(3) lending can be divided into risks to taxpayers and broader economic consequences. These costs can be weighed against the benefits of Section 13(3) lending, which could be significant if the lending restores or maintains financial stability. While lending poses risks to the taxpayer, if the Fed did not act, the economic losses from allowing a financial crisis to run its course would also pose risks to taxpayers in terms of a larger federal budget deficit and privately through higher unemployment, lost wealth, and so forth.

The risk to the taxpayer of lending is primarily default risk. The Fed can—but is not required to—attach various conditions to its lending to minimize default, including requiring short maturities, collateral in excess of the funds lent (i.e., applying a "haircut" to collateral), senior creditor standing, and recourse if collateral proves insufficient. Note that the Fed has typically—but not always—imposed all of these conditions to Section 13(3) assistance. Loans to nonbanks are arguably not inherently riskier than loans to banks; to the extent that Section 13(3) programs were riskier than the discount window, it was mainly because these conditions were loosened. Lending to non-banks may also be riskier because the Fed can safeguard its lending to banks through prudential supervision, but, with the exception of firms designated as "systemically important financial institutions" (SIFIs) or structured as bank holding companies, the Fed has no jurisdiction to supervise nonbanks for safety and soundness. In times of crisis, the Fed's broader ability to restore financial stability also reduces default risk for any specific loan.

In some cases, the Fed was able to protect the taxpayer through terms other than conventional collateral pledges. For example, the Fed required that AIG provide it with compensation in the form of an equity stake in the company in exchange for a loan. The Fed's ability to protect taxpayers against losses could be more limited in the future based on a recent court ruling. The court found that the AIG equity stake was an illegal exaction.63 However, because the Dodd-Frank Act prohibits assistance to single or failing firms, future scenarios in which the Fed would need to take an equity stake to adequately protect taxpayers may be limited.

One broader economic concern with Section 13(3) lending raised by House Financial Services Committee Chairman Jeb Hensarling is that "its use risks exacerbating moral hazard costs."64 Moral hazard is the concept that firms will take greater risks if they are protected from negative outcomes. In this case, moral hazard occurs because firms are more likely to be more reliant on short-term lending if they anticipate access to Fed lending during a liquidity crisis. Some argue that Section 13(3) should be repealed or curbed because of moral hazard, but Bernanke compares that approach to shutting down the fire department to encourage fire safety, instead of toughening the fire code.65 Unlike lending to banks, the Fed cannot mitigate moral hazard through prudential supervision, however, except in the cases noted above.

Moral hazard concerns can be overstated. For instance, moral hazard arguably did not cause nonbank financial firms to be reckless about liquidity management before the crisis, unless they were able to anticipate that Section 13(3) would be used to provide them with liquidity, even though it had never been used for that purpose before 2008. Thus, greater market discipline might reduce moral hazard problems but cannot eliminate liquidity crises.

How Much Discretion Should the Fed Be Granted?

Limiting discretion is the common goal running throughout many of the diverse policy proposals to alter Section 13(3). The fact that the Fed has broad discretion under Section 13(3) allowed the Fed, for or better or worse, to act swiftly, pledge sizable funds, create a diverse set of facilities for a diverse set of lenders, and tackle multiple, disparate problems as they emerged. It also explains why the Fed was able to provide assistance in forms not envisioned by Congress that arguably were not always consistent with the spirit of a lender of last resort, such as the Maiden Lane LLCs.66

One potential drawback to discretion is that assistance might be provided in ways the Dodd-Frank Act did not intend, such as to prevent a firm from failing. As noted above, the Dodd-Frank Act modified Section 13(3) to rule out lending to an insolvent firm, but some critics are skeptical that the Dodd-Frank Act successfully ruled out the use of Section 13(3) to aid an insolvent firm. The Fed's final rule further limits its ability to assist a failing firm by prohibiting the creation of any facility unless it is open to at least five eligible borrowers, lending to any recipient who is not current on debt over the past 90 days, lending to a healthy firm for the purposes of preventing a third party from failing (as was the case with JP Morgan Chase and Bear Stearns), and lending to a firm so that it can avoid bankruptcy or resolution. Nevertheless, as long as emergency authority exists, policymakers may be tempted to use it to bail out a failing firm to avoid a crisis—and the broader the authority, the more feasible it becomes.67

Arguably, another drawback to discretion is the potential for favoritism. Because the types of nonbank financial firms are numerous and diverse, deciding who should get access to loans involves trade-offs and judgments that are not completely technical in nature. For example, the Fed set a high minimum loan size in TALF that effectively limited access to loans at below-market interest rates to large investors. The decision to outsource certain functions of emergency facilities to third-party vendors also creates the potential for favoritism.68

Another consideration for the degree of discretion provided is the Fed's independence from Congress and the Administration. The Fed argues that maintaining its independence is important for the credibility and effectiveness of its monetary policy. At the same time, greater independence complicates accountability to Congress. It is fair to question to what degree limiting discretion on Section 13(3) affects perceptions of monetary policy independence because 13(3) is used so rarely. The Dodd-Frank Act's requirement that assistance under Section 13(3) be preapproved by the Treasury Secretary reduces the Fed's independence from the Administration, although the Treasury Secretary supported all of the Fed's actions taken under Section 13(3) in 2008.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell argued when he was a Fed Governor that Congress should maintain the Fed's current discretion under Section 13(3) because

One of the lessons of the crisis is that the financial system evolves so quickly that it is difficult to predict where threats will emerge and what actions may be needed in the future to respond. Because we cannot anticipate what may be needed in the future, the Congress should preserve the ability of the Fed to respond flexibly and nimbly to future emergencies. Further restricting or eliminating the Fed's emergency lending authority will not prevent future crises, but it will hinder the Fed's ability to limit the harm from those crises for families and businesses.69

Alternatively, some argue that discretion can increase uncertainty, thereby increasing systemic risk. For example, some argue that the failure of Lehman Brothers exacerbated financial instability because market participants believed that it would receive Fed assistance similar to Bear Stearns and panicked when it did not.

The Dodd-Frank Act reduced the Fed's discretion under Section 13(3), and the final rule implementing those changes reduced it further. In Governor Powell's view, the Dodd-Frank reforms "struck a reasonable balance ... (and) it would be a mistake to go further and impose additional restrictions" on Section 13(3). By reducing the Fed's discretion, Chair Janet Yellen has stated that H.R. 3189 would "essentially repeal the Federal Reserve's remaining ability to act in a crisis."70 By contrast, Chairman Hensarling believes that "Dodd-Frank tried but failed to rein in the Fed's emergency lending authority."71

Congress could curb discretion by adding more restrictions to Section 13(3) or by requiring Congressional approval for each action taken under Section 13(3). The latter proposal, depending on the details, could potentially affect the timeliness and credibility of the Fed's actions during a crisis. Examples of additional restrictions Congress could add to Section 13(3) include restrictions on who is eligible for assistance and the terms of assistance, such as acceptable collateral or the rate that the Fed charges (discussed below). Congress could also add limits on the amount of total assistance or assistance to one borrower.72 Granting the Fed discretion on these issues is in part a judgment by Congress about whether it or the Fed can balance these competing policy considerations more effectively. For example, favoritism concerns could potentially be exacerbated or mitigated if Congress were more involved.

What Rate Should the Fed Charge?

In determining what rate the lender of last resort should charge, economists and central bankers almost universally point to the maxim of Walter Bagehot—lend freely against good collateral, but at a penalty.73 Consensus breaks down on how penurious the penalty rate should be. A penalty rate (i.e., a rate that is higher than the market rate) achieves two goals: (1) it maximizes the return to the central bank (and thus the taxpayer) and (2) it discourages lenders from turning to the central bank instead of the private market when private credit is available (hence, the concept of lender of last resort), thereby reducing moral hazard problems. These two goals call for making the rate as high as possible. Alternatively, financial stability concerns call for making the rate as close to market rates as possible. Higher rates will potentially undermine financial stability by discouraging the use of Fed facilities, which may increase the stigma associated with borrowing from the Fed (i.e., if lending is made unattractive to healthy firms, the decision to borrow could be taken as a sign of desperation). Further, higher rates might weaken the health of the borrower, thereby undermining the goal of restoring stability. This concept is most starkly demonstrated in the case of assistance to AIG during the crisis (for details, see the Appendix). The terms of the initial Fed loan were more favorable to the taxpayer than the subsequent iterations of assistance, which were repeatedly renegotiated for fear that overly harsh terms would compromise the company's viability.

There is also a question of how a market rate should be calculated during a crisis. Generally, two features of a crisis are that markets become illiquid (so there are fewer transactions to observe) and rates become higher. These features would argue for using a pre-crisis market rate as the baseline. Critics incorrectly accused the Fed of charging below-market rates during the crisis.74 The seeming contradiction between the low rates charged by the Fed in absolute terms and the fact that these rates were a markup above market rates is explained by the fact that the market rates referenced by the Fed were directly influenced by monetary policy. At the same time the Fed was making these loans, it was in the process of reducing the federal funds rate to zero.

The possibility of a limited group of recipients receiving below-market borrowing rates was arguably greatest in the two cases in which the direct recipients of the loans were not the intended recipients of ultimate assistance. The AMLF made loans to banks to finance the purchase of commercial paper to relieve stress in the commercial-paper market. The TALF made loans to investment funds to purchase ABS to revive the private-securitization market. Borrowers would only choose to participate in these programs if they could reasonably expect that, adjusted for risk, the profits they would earn from the purchase of commercial paper or ABS would exceed the interest on Fed loans. To entice banks and investors, respectively, to participate in these programs, the Fed made the terms of the programs relatively attractive to them (e.g., the loans were non-recourse), potentially reducing the profits and increasing the risk exposure for the Fed. Weighed against these costs, this arrangement may have had benefits to the Fed, such as avoiding the need to "pick winners" or develop the financial expertise to accurately price complex securities.

Section 13(3) does not address whether a penalty rate should be charged, but the final rule implementing the Dodd-Frank Act's modifications requires the Fed to charge a penalty rate, defined as a premium to the market rate prevailing in normal circumstances.

Should Borrowers' Identities Be Kept Confidential?

Many Members of Congress contend that taxpayers have a right to know to whom the Fed is lending and on what terms because taxpayers are the ultimate backstop for these loans. The Fed has argued that allowing the public to know which firms are accessing its facilities could undermine investor confidence in the institutions receiving aid because of a perception that recipients are weak or unsound. A loss of investor confidence could potentially lead to destabilizing runs on the institution's deposits, debt, or equity. If institutions feared that this would occur, the Fed argues, the institutions would be wary of participating in the Fed's programs. A delayed release of information mitigates, but does not eliminate, these concerns. Some critics would view less Fed lending as a positive outcome, but if the premise that the Fed's lender of last resort role helps prevent financial crises by maintaining the liquidity of the financial system is accepted, then an unwillingness by institutions to access Fed facilities makes the system less safe. One study argues that the Fed's decision to discourage banks to use the discount window from 1929-1931 (at a time when identities were kept confidential) worsened the bank panic in the Great Depression.75

Whether investors are less willing to borrow as a result of the disclosure of identities will not be apparent until the next crisis. A historical example supporting the Fed's argument would be the experience with the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) in the Great Depression. When the RFC publicized to which banks it had given loans, those banks typically experienced depositor runs.76 A more recent example—disclosure of TARP fund recipients—provides mixed evidence. At first, TARP funds were widely disbursed, and recipients included all the major banks. At that point, there was no perceived stigma to TARP participation. Subsequently, many banks repaid TARP shares at the first opportunity, and several remaining participants have expressed concern that if they did not repay soon, investors would perceive them as weak.

The granularity of information to be disclosed is a policy issue. Aggregate information about programs and activities that does not require the identification of borrowers tends to be more useful for broad policy purposes, while current information on specific transactions within the programs is of interest to investors. The Fed voluntarily released the former, but only reluctantly released the latter when compelled to by legislation and lawsuits. For oversight purposes, the former would suffice for answering most questions about taxpayer risk exposure, expected profits or losses, potential subsidies, economic effects, and evaluating the state of the financial system. The latter would be necessary for transparency around issues such as favoritism (certain firms receiving preferential treatment over similar firms).77 Although preventing favoritism is a valid policy goal, releasing the identities of borrowers to "name and shame" them is more questionable, especially if one believes that these programs were helpful for providing liquidity and maintaining financial stability. Naming and shaming is likely to result in less uptake of the programs in the future. If one believes that these lending programs are not helpful, repealing Section 13(3) would be more effective than undermining their effectiveness by stigmatizing recipients.

As discussed above, the Dodd-Frank Act compromised between stability and oversight concerns by requiring borrowers' identities to be publicly released with a lag. Some Members of Congress have expressed an interest in revisiting this issue.

Selected Legislation

114th Congress

One bill to amend Section 13(3) (H.R. 3189) passed the House in the 114th Congress. Other bills to amend Section 13(3) that did not see legislative action were H.R. 5983, S. 1320, and H.R. 2625.

H.R. 3189

The Fed Oversight Reform and Modernization Act (H.R. 3189) was ordered to be reported by the House Financial Services Committee on July 29, 2015. On November 19, 2015, it was passed by the House. Section 11 of the bill as passed amends Section 13(3) to limit the Fed's discretion to make emergency loans. It would limit 13(3) to "unusual and exigent circumstances that pose a threat to the financial stability of the United States" and would require "the affirmative vote of not less than nine presidents of Federal reserve banks" in addition to the current requirement of the affirmative vote of five Fed governors. It would forbid the Fed from accepting as collateral equity securities issued by a borrower. It would require the Fed to issue a rule establishing how it would determine sufficiency of collateral; acceptable classes of collateral; any discount that would be applied to determine the sufficiency of collateral; and how it would obtain independent appraisals for valuing collateral. It would eliminate the current language permitting the Fed to establish the solvency of a borrower based on the borrower's certification and would specify that before a borrower may be eligible for assistance, the Fed's Board and any other federal banking regulator with jurisdiction over the borrower must certify that the borrower is not insolvent. It would limit assistance to institutions "predominantly engaged in financial activities" and preclude assistance to federal, state, and local government agencies and government-controlled or sponsored entities. It would require the Fed to issue a rule establishing a minimum interest rate on emergency loans based on the sum of the average secondary discount rate charged by the Federal Reserve banks over the most recent 90-day period and the average of the difference between a distressed corporate bond index (as defined by a rule issued by the Fed) and the Treasury yield over the most recent 90-day period.

H.R. 5983

The same language amending 13(3) from H.R. 3189 was then included in the Financial Choice Act of 2016 (H.R. 5983), a wide-ranging financial regulatory relief bill sponsored by Jeb Hensarling, Chairman of the Financial Services Committee.78 H.R. 5983 was ordered to be reported as amended by the House Committee on Financial Services on September 13, 2016, and was reported on December 20, 2016.

115th Congress

One bill to amend Section 13(3) (H.R. 10) passed the House in the 115th Congress. Other bills to amend Section 13(3) that were reported by the House Financial Services Committee were H.R. 4302 and H.R. 6741.

H.R. 10

The same language amending 13(3) from H.R. 3189 in the 114th Congress was included in the Financial Choice Act of 2017 (H.R. 10), a wide-ranging financial regulatory relief bill sponsored by Jeb Hensarling, Chairman of the Financial Services Committee.79 H.R. 10 was passed by the House on June 8, 2017.

Appendix. Details on the Actions Taken Under Section 13(3) in 2008

Term Securities Lending Facility

Shortly before Bear Stearns suffered its liquidity crisis, the Fed created the Term Securities Lending Facility (TSLF) on March 11, 2008, to expand its existing securities lending program for primary dealers.80 Primary dealers are financial firms that are the Fed's counterparties for open market operations, including investment banks that were ineligible to access the Fed's lending facilities for banks. At the end of 2007, there were 20 primary dealers, including Bear Stearns.81 The proximate cause of Bear Stearns' crisis was its inability to roll over its short-term debt, and the Fed created the TSLF and the Primary Dealer Credit Facility (discussed below) to offer an alternative source of short-term liquidity for primary dealers.