Enhanced Prudential Regulation of Large Banks

The 2007-2009 financial crisis highlighted the problem of “too big to fail” financial institutions—the concept that the failure of large financial firms could trigger financial instability, which in several cases prompted extraordinary federal assistance to prevent their failure. One pillar of the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act’s (P.L. 111-203) response to addressing financial stability and ending too big to fail is a new enhanced prudential regulatory (EPR) regime that applies to large banks and to nonbank financial institutions designated by the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) as systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs). Previously, FSOC had designated four nonbank SIFIs for enhanced prudential regulation, but all four have since been de-designated.

Under this regime, the Federal Reserve (Fed) is required to apply a number of safety and soundness requirements to large banks that are more stringent than those applied to smaller banks. These requirements are intended to mitigate systemic risk posed by large banks

Stress tests and capital planning ensure banks hold enough capital to survive a crisis.

Living wills provide a plan to safely wind down a failing bank.

Liquidity requirements ensure that banks are sufficiently liquid if they lose access to funding markets.

Counterparty limits restrict the bank’s exposure to counterparty default.

Risk management requires publicly traded companies to have risk committees on their boards and banks to have chief risk officers.

Financial stability requirements provide for regulatory interventions that can be taken only if a bank poses a threat to financial stability.

Capital requirements under Basel III, an international agreement, require large banks hold more capital than other banks to potentially absorb unforeseen losses.

The Dodd-Frank Act automatically subjected all bank holding companies and foreign banks with more than $50 billion in assets to enhanced prudential regulation. In 2017, the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 115-174) created a more “tiered” and “tailored” EPR regime for banks. It automatically exempted domestic banks with assets between $50 billion and $100 billion (five at present) from enhanced regulation. The Fed has discretion to apply most individual enhanced prudential provisions to the 11 domestic banks with between $100 billion and $250 billion in assets on a case-by-case basis if it would promote financial stability or the institutions’ safety and soundness, and has proposed exempting them from several EPR requirements. The eight domestic banks that have been designated as Global-Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs) and the five banks with more than $250 billion in assets or $75 billion in cross-jurisdictional activity remain subject to all Dodd-Frank EPR requirements. In addition, the Fed has proposed applying some EPR requirements on a progressively tiered basis to the 23 foreign banks with over $50 billion in U.S. assets and $250 billion in global assets.

P.L. 115-174 also reduced the amount of capital that custody banks are required to hold against one of the EPR capital requirements, the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR). In addition, the Fed has issued a proposed rule that would reduce the amount of capital that G-SIBs are required to hold against the SLR. Finally, the Fed has proposed another rule that would combine capital planning under the stress tests with overall capital requirements for large banks.

Collectively, these proposed changes would reduce, to varying degrees, capital and other advanced EPR requirements for banks with more than $50 billion in assets. In the view of the banking regulators and the supporters of P.L. 115-174, these changes better tailor EPR to match the risks posed by large banks. Opponents are concerned that the additional systemic and prudential risks posed by these changes outweigh the benefits to society of reduced regulatory burden, believing that the benefits will mainly accrue to the affected banks.

Enhanced Prudential Regulation of Large Banks

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Who Is Subject to Enhanced Prudential Regulation?

- U.S. Banks

- Foreign Banks Operating in the United States

- Other Financial Firms

- What Requirements Must Large Banks Comply With Under Enhanced Regulation?

- Stress Tests and Capital Planning

- Resolution Plans ("Living Wills")

- Liquidity Requirements

- Counterparty Exposure Limits

- Risk Management Requirements

- Provisions Triggered in Response to Financial Stability Concerns

- Basel III Capital Requirements

- Assessments

- Proposed Changes to Large Bank Regulation

- Higher, Tiered Thresholds

- Stress Capital Buffer

- Treatment of Custody Banks Under the Supplementary Leverage Ratio

- Incorporating the G-SIB Surcharge into the Enhanced Supplementary Leverage Ratio and the Total Loss Absorbing Capacity

- Evaluating Proposed Changes

Figures

Summary

The 2007-2009 financial crisis highlighted the problem of "too big to fail" financial institutions—the concept that the failure of large financial firms could trigger financial instability, which in several cases prompted extraordinary federal assistance to prevent their failure. One pillar of the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act's (P.L. 111-203) response to addressing financial stability and ending too big to fail is a new enhanced prudential regulatory (EPR) regime that applies to large banks and to nonbank financial institutions designated by the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) as systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs). Previously, FSOC had designated four nonbank SIFIs for enhanced prudential regulation, but all four have since been de-designated.

Under this regime, the Federal Reserve (Fed) is required to apply a number of safety and soundness requirements to large banks that are more stringent than those applied to smaller banks. These requirements are intended to mitigate systemic risk posed by large banks

- Stress tests and capital planning ensure banks hold enough capital to survive a crisis.

- Living wills provide a plan to safely wind down a failing bank.

- Liquidity requirements ensure that banks are sufficiently liquid if they lose access to funding markets.

- Counterparty limits restrict the bank's exposure to counterparty default.

- Risk management requires publicly traded companies to have risk committees on their boards and banks to have chief risk officers.

- Financial stability requirements provide for regulatory interventions that can be taken only if a bank poses a threat to financial stability.

- Capital requirements under Basel III, an international agreement, require large banks hold more capital than other banks to potentially absorb unforeseen losses.

The Dodd-Frank Act automatically subjected all bank holding companies and foreign banks with more than $50 billion in assets to enhanced prudential regulation. In 2017, the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 115-174) created a more "tiered" and "tailored" EPR regime for banks. It automatically exempted domestic banks with assets between $50 billion and $100 billion (five at present) from enhanced regulation. The Fed has discretion to apply most individual enhanced prudential provisions to the 11 domestic banks with between $100 billion and $250 billion in assets on a case-by-case basis if it would promote financial stability or the institutions' safety and soundness, and has proposed exempting them from several EPR requirements. The eight domestic banks that have been designated as Global-Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs) and the five banks with more than $250 billion in assets or $75 billion in cross-jurisdictional activity remain subject to all Dodd-Frank EPR requirements. In addition, the Fed has proposed applying some EPR requirements on a progressively tiered basis to the 23 foreign banks with over $50 billion in U.S. assets and $250 billion in global assets.

P.L. 115-174 also reduced the amount of capital that custody banks are required to hold against one of the EPR capital requirements, the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR). In addition, the Fed has issued a proposed rule that would reduce the amount of capital that G-SIBs are required to hold against the SLR. Finally, the Fed has proposed another rule that would combine capital planning under the stress tests with overall capital requirements for large banks.

Collectively, these proposed changes would reduce, to varying degrees, capital and other advanced EPR requirements for banks with more than $50 billion in assets. In the view of the banking regulators and the supporters of P.L. 115-174, these changes better tailor EPR to match the risks posed by large banks. Opponents are concerned that the additional systemic and prudential risks posed by these changes outweigh the benefits to society of reduced regulatory burden, believing that the benefits will mainly accrue to the affected banks.

The 2007-2009 financial crisis highlighted the problem of "too big to fail" financial institutions—the concept that the failure of large financial firms could trigger financial instability, which in several cases prompted extraordinary federal assistance to prevent their failure. One pillar of the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act's (P.L. 111-203) response to addressing financial stability and ending too big to fail is a new enhanced prudential regulatory (EPR) regime that applies to large banks and to nonbank financial institutions designated by the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) as systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs). Previously, FSOC had designated four nonbank SIFIs for enhanced prudential regulation, but all four have since been de-designated.

Under this regime, the Federal Reserve (Fed) is required to apply a number of safety and soundness requirements to large banks that are more stringent than those applied to smaller banks. These requirements are intended to mitigate systemic risk posed by large banks

- Stress tests and capital planning ensure banks hold enough capital to survive a crisis.

- Living wills provide a plan to safely wind down a failing bank.

- Liquidity requirements ensure that banks are sufficiently liquid if they lose access to funding markets.

- Counterparty limits restrict the bank's exposure to counterparty default.

- Risk management requires publicly traded companies to have risk committees on their boards and banks to have chief risk officers.

- Financial stability requirements provide for regulatory interventions that can be taken only if a bank poses a threat to financial stability.

- Capital requirements under Basel III, an international agreement, require large banks hold more capital than other banks to potentially absorb unforeseen losses.

The Dodd-Frank Act automatically subjected all bank holding companies and foreign banks with more than $50 billion in assets to enhanced prudential regulation. In 2017, the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 115-174) created a more "tiered" and "tailored" EPR regime for banks. It automatically exempted domestic banks with assets between $50 billion and $100 billion (five at present) from enhanced regulation. The Fed has discretion to apply most individual enhanced prudential provisions to the 11 domestic banks with between $100 billion and $250 billion in assets on a case-by-case basis if it would promote financial stability or the institutions' safety and soundness, and has proposed exempting them from several EPR requirements. The eight domestic banks that have been designated as Global-Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs) and the five banks with more than $250 billion in assets or $75 billion in cross-jurisdictional activity remain subject to all Dodd-Frank EPR requirements. In addition, the Fed has proposed applying some EPR requirements on a progressively tiered basis to the 23 foreign banks with over $50 billion in U.S. assets and $250 billion in global assets.

P.L. 115-174 also reduced the amount of capital that custody banks are required to hold against one of the EPR capital requirements, the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR). In addition, the Fed has issued a proposed rule that would reduce the amount of capital that G-SIBs are required to hold against the SLR. Finally, the Fed has proposed another rule that would combine capital planning under the stress tests with overall capital requirements for large banks.

Collectively, these proposed changes would reduce, to varying degrees, capital and other advanced EPR requirements for banks with more than $50 billion in assets. In the view of the banking regulators and the supporters of P.L. 115-174, these changes better tailor EPR to match the risks posed by large banks. Opponents are concerned that the additional systemic and prudential risks posed by these changes outweigh the benefits to society of reduced regulatory burden, believing that the benefits will mainly accrue to the affected banks.

Introduction

"Too big to fail" (TBTF) is the concept that a financial firm's disorderly failure would cause widespread disruptions in financial markets and result in devastating economic and societal outcomes that the government would feel compelled to prevent, perhaps by providing direct support to the firm. Such firms are a source of systemic risk—the potential for widespread disruption to the financial system, as occurred in 2008 when the securities firm Lehman Brothers failed.1

Although TBTF has been a perennial policy issue, it was highlighted by the near-collapse of several large financial firms in 2008. Some of the large firms were nonbank financial firms, but a few were depository institutions. To avert the imminent failures of Wachovia and Washington Mutual, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) arranged for them to be acquired by other banks without government financial assistance. Citigroup and Bank of America were offered additional preferred shares through the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) and government guarantees on selected assets they owned.2 In many of these cases, policymakers justified government intervention on the grounds that the firms were "systemically important" (popularly understood to be synonymous with too big to fail). Some firms were rescued on those grounds once the crisis struck, although the government had no explicit policy to rescue TBTF firms beforehand.

In response to the crisis, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (hereinafter, the Dodd-Frank Act; P.L. 111-203), a comprehensive financial regulatory reform, was enacted in 2010.3 Among its stated purposes are "to promote the financial stability of the United States…, [and] to end 'too big to fail,' to protect the American taxpayer by ending bailouts." The Dodd-Frank Act took a multifaceted approach to addressing the TBTF problem. This report focuses on one pillar of that approach—the Federal Reserve's (Fed's) enhanced (heightened) prudential regulation for large banks and nonbank financial firms designated as systemically important by the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC).4 For an overview of the TBTF issue and other policy approaches to mitigating it, see CRS Report R42150, Systemically Important or "Too Big to Fail" Financial Institutions, by Marc Labonte.

The Dodd-Frank Act automatically subjected all bank holding companies and foreign banks with more than $50 billion in assets to enhanced prudential regulation (EPR). In addition, Basel III (a nonbinding international agreement that U.S. banking regulators implemented through rulemaking after the financial crisis) included several capital requirements that only apply to large banks. In 2018, the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (referred to herein as P.L. 115-174) eliminated most EPR requirements for banks with assets between $50 billion and $100 billion. Banks that have been designated as Global-Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs) by the Financial Stability Board (an international, intergovernmental forum) or have more than $250 billion in assets automatically remain subject to all EPR requirements, as modified. P.L. 115-174 gives the Fed discretion to apply most individual EPR provisions to banks with between $100 billion and $250 billion in assets on a case-by-case basis only if it would promote financial stability or the institution's safety and soundness.5

This report begins with a description of who is subject to enhanced prudential regulation and what requirements make up EPR. It then discusses several rules proposed by the Fed that would reduce EPR requirements for some large banks; some in response to P.L. 115-174 and some before it was enacted.

Who Is Subject to Enhanced Prudential Regulation?

Under P.L. 115-174, the application of EPR remains mainly based on asset size and charter type. Broadly speaking, only three types of financial charters allow financial institutions to accept insured deposits—banks, thrifts, and credit unions. Banks operating in the United States can be U.S. or foreign based. Depository institutions are regulated much differently than other types of financial institutions. This section discusses whether or not EPR is applied to each of those types of institutions, as well as other types of financial firms. A detailed discussion of which provisions apply at which size threshold is discussed in the "Higher, Tiered Thresholds" section below.

U.S. Banks

Banks and Bank Holding Companies

By statute, enhanced regulation applies to large U.S. bank holding companies (BHCs). A BHC is used any time a company owns multiple banks, but the BHC structure also allows for a large, complex financial firm with depository banks to operate multiple subsidiaries in different financial sectors. In general, the regime's requirements are applied to all parts of the BHC, not just its banking subsidiaries.

Five large investment "banks" that operated in securities markets and did not have depository subsidiaries (and therefore were not BHCs) were among the largest, most interconnected U.S. financial firms and were at the center of events during the financial crisis. Two of the large investment banks, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, were granted BHC charters in 2008, whereas others failed (Lehman Brothers) or were acquired by BHCs (Merrill Lynch and Bear Stearns). As a result, all of the largest U.S. investment banks are now BHCs, subject to the enhanced prudential regime.

If a bank does not have a BHC structure, it is not subject to enhanced regulation. The Congressional Research Service (CRS) found two banks that are currently over the previous $50 billion threshold and do not have a BHC structure.6 One of the two, Zions, converted its corporate structure from a BHC to a standalone bank in 2018, reportedly in order to no longer be subject to EPR.7 Under Title I of the Dodd-Frank Act's "Hotel California" provision, which was unchanged by P.L. 115-174, BHCs with more than $50 billion in assets that participated in TARP cannot escape enhanced regulation by debanking (i.e., divesting of their depository business) unless permitted to by FSOC.8 FSOC found that "there is not a significant risk that Zions could pose a threat to U.S. financial stability," and permitted it to withdraw from EPR.9

Thrifts

Similar to BHCs, thrift holding companies (THCs), also called savings and loan holding companies, have subsidiaries that accept deposits, make loans, and can also have nonbank subsidiaries. Although THCs are also regulated by the Fed, the EPR statute does not mention THCs. To date, enhanced prudential regulatory requirements have not been applied to large thrift (savings and loan) holding companies, with the exception of company-run stress tests. The Fed's 2018 proposed rule implementing P.L. 115-174 changes would subject THCs to EPR for the first time if they are not substantially engaged in insurance.10 Official regulatory data report four THCs with more than $100 billion in assets; three are substantially engaged in insurance, so only the one that is not (Charles Schwab) is subject to EPR. Two THCs have between $50 billion to $100 billion in assets, and are therefore not subject to EPR.11

U.S. Institutions Subject to EPR Under P.L. 115-174

The proposed rule that would implement P.L. 115-174's changes to the $50 billion asset threshold creates four categories of banks based on their asset size and systemic importance, with increasingly stringent EPR requirements applied to each category as these characteristics increase.12 Table 1 shows which BHCs and THCs would currently be assigned to each category, as well as banks no longer subject to EPR because they hold between $50 billion and $100 billion in assets.13 A discussion of which requirements apply to each category is found in the "Higher, Tiered Thresholds" section below.

Banks are assigned to categories based on size or other measures of complexity and interconnectedness, reflecting the relationship between those factors and systemic importance. The most stringent tier of regulation applies only to G-SIBs (Category I). Since 2011, the Financial Stability Board (FSB), an international forum that coordinates the work of national financial authorities and international standard-setting bodies, has annually designated G-SIBs based on the banks' cross-jurisdictional activity, size, interconnectedness, substitutability, and complexity.14 Currently, 30 banks are designated as G-SIBs worldwide, 8 of which are headquartered in the United States. Category II includes other banks with more than $700 billion in assets or more than $75 billion in cross-jurisdictional activity (and at least $100 billion in total assets). Currently, no bank meets the former test but one bank meets the latter test. Category III includes all other banks with $250 billion or more in assets or more than $75 billion in nonbank assets, weighted short-term funding, or off-balance sheet exposure (and at least $100 billion in total assets).15 Currently, all Category III banks meet the $250 billion asset test. Category IV includes banks with between $100 and $250 billion in assets who do not meet the criteria in one of the other categories.

Table 1. Proposed EPR Rule and U.S. BHCs and THCs with

More Than $50 Billion in Assets

(as of September 2018)

|

Subject to EPR Under Proposed Rule |

Not Subject to EPR Under Proposed Rule |

|

Category 1: U.S. Global-Systematically Important Banks |

THC >$100 billion in assets not subject to proposal because engaged in insurance: |

|

JPMorgan Chase & Co. |

Teachers Insurance & Annuity Association of Americaa |

|

Bank Of America Corporation |

State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Companya |

|

Wells Fargo & Company |

United Services Automobile Associationa |

|

Citigroup Inc. |

No longer qualify for EPR: $50 billion-$100 billion in assets |

|

Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. |

Synchrony Financiala |

|

Morgan Stanley |

Comerica Incorporated |

|

Bank Of New York Mellon Corporation |

E*TRADE Financiala |

|

State Street Corporation |

Silicon Valley Bank |

|

Category II: >$750 billion in assets or >$75 billion in cross-jurisdictional activity |

NY Community Bancorp |

|

Northern Trust Corporation |

|

|

Category III: >$250 billion in assets or meet other metrics of complexity |

|

|

U.S. Bancorp |

|

|

PNC Financial Services Group, Inc. |

|

|

Capital One Financial Corporation |

|

|

Charles Schwaba |

|

|

Category IV: $100 billion-$250 billion in assets |

|

|

BB&T Corporation |

|

|

SunTrust Banks, Inc. |

|

|

American Express Company |

|

|

Ally Financial Inc. |

|

|

Citizens Financial Group, Inc. |

|

|

Fifth Third Bancorp |

|

|

Keycorp |

|

|

Regions Financial Corporation |

|

|

M&T Bank Corporation |

|

|

Huntington Bancshares Incorporated |

|

|

Discover Financial Services |

Source: Federal Reserve, "Prudential Standards for Large Bank Holding Companies and Savings and Loan Holding Companies," Federal Register, vol. 83, no. 230, November 29, 2018, p. 61408; Federal Reserve, National Information Center, "Holding Companies with Assets Greater than $10 Billion."

Notes: Banks are classified to categories in the Fed's proposed rule (at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/bcreg20181031a.htm). See Table 3 for EPR requirements by category. In addition to banks with more than $250 billion in total assets, banks are classified as Category III banks if they had more than $75 billion in nonbank assets, weighted short-term wholesale funding, or off-balance sheet exposure.

Foreign Banks Operating in the United States

The enhanced prudential regime also applies to foreign banking organizations operating in the United States that meet the EPR asset threshold based on global assets.16 However, the implementing regulations, before P.L. 115-174 was enacted, have imposed most EPR requirements only on foreign banks with more than $50 billion in U.S. nonbranch, nonagency assets.17 Foreign banks with more than $50 billion in U.S. nonbranch, nonagency assets must form intermediate holding companies (IHCs) for their U.S. operations; those intermediate holding companies are essentially treated as equivalent to U.S. banks for purposes of applicability of the enhanced regime and bank regulation more generally.18

P.L. 115-174 raised the EPR threshold for global assets, but did not introduce a threshold for U.S. assets of foreign banks. It clarified that the act did not affect the Fed's rule on IHCs for foreign banks with more than $100 billion in global assets or limit the Fed's authority to subject those banks to EPR.

Because the threshold for domestic banks has been raised, there is now a question of whether to raise the threshold for U.S. assets of foreign banks to maintain regulatory parity with U.S. banks. The Dodd-Frank Act states that enhanced regulation of foreign banks should "give due regard to the principle of national treatment and equality of competitive opportunity; and take into account the extent to which the foreign financial company is subject on a consolidated basis to home country standards that are comparable" to U.S. standards. The parity issue can be viewed from the perspective of U.S. assets or foreign assets. For example, should a foreign G-SIB with between $50 billion and $100 billion in U.S. assets have its U.S. operations regulated similarly to a U.S. bank with less than $100 billion in assets (i.e., not subject to EPR requirements) or to a U.S. G-SIB (i.e., subject to the most stringent EPR requirements)?

Under proposed rules, the 23 foreign banks listed in Table 2 would currently be subject to some EPR requirements.19 Most foreign banks have less than $250 billion in U.S. assets, but the banks in Table 2 have more than $250 billion in global assets, and several are foreign G-SIBs.20 The proposed rules use $50 billion in U.S. assets as a minimum threshold for EPR, but are tiered so that most requirements only apply at higher thresholds. To determine which foreign banks are subject to which EPR requirements, the proposals would use total U.S. assets—in contrast to existing EPR rules, which exempt assets in U.S. branches or agencies. As a result, more foreign banks would become subject to some EPR requirements under the proposal. In addition, over 80 foreign banks (including those in Table 2) would be required to submit resolution plans (or living wills) under a proposed rule, because they had more than $250 billion in worldwide assets and operate in the United States, regardless of the extent of their U.S. assets.21

|

Category II or III |

Category IV |

Uncategorized ($50-$100 Billion in U.S. Assets) |

|

Toronto-Dominion |

BNP Paribas |

Bank of China |

|

HSBC |

Banco Santander |

Bank of Nova Scotia |

|

Credit Suisse |

Bank of Montreal |

Canadian Imperial |

|

Deutsche Bank |

BBVA |

Credit Agricole |

|

Barclays |

BPCE |

I & C Bank of China |

|

MUFG |

Societe Generale |

Norinchukin |

|

Royal Bank of Canada |

Sumitomo Mitsui |

Rabobank |

|

UBS |

||

|

Mizhuo |

Source: Federal Reserve, Federal Reserve, "Prudential Standards for Large Foreign Bank Operations," April 8, 2019, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/bcreg20190408a.htm.

Note: Proposal only applies to foreign banks with over $100 billion in worldwide assets. The Fed does not currently collect enough official data to determine whether some foreign banks are Category II or III. In addition to banks with more than $700 billion in total assets, banks are classified as Category II banks if they had more than $75 billion in cross-jurisdictional activity. In addition to banks with more than $250 billion in total assets, banks are classified as Category III banks if they had more than $75 billion in nonbank assets, weighted short-term wholesale funding, or off-balance sheet exposure. See Table 3 for EPR requirements by category.

Hereinafter, the report will refer to BHCs, THCs, and foreign banking operations meeting the criteria described above as banks subject to EPR, unless otherwise noted.

Other Financial Firms

Numerous other large financial firms operating in the United States are not BHCs and are not automatically subject to enhanced regulation, such as credit unions, insurance companies, government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs), securities holding companies, and nonbank lenders. However, the FSOC may designate any nonbank financial firm as a systemically important financial institution (SIFI) if its failure or activities could pose a risk to financial stability. Designated SIFIs are then subject to the Fed's EPR regime, which can be tailored to consider their business models. Since inception, FSOC has designated three insurers (AIG, MetLife, and Prudential Financial) and one other financial firm (GE Capital) as SIFIs. MetLife's designation was subsequently invalidated by a court decision,22 which the Trump Administration declined to appeal, and the other three designations were later rescinded by FSOC.23 In some cases, these former SIFIs had substantially altered or shrank their operations between designation and de-designation.

In addition to the former SIFIs, a CRS search of the proprietary database S&P Capital IQ identified multiple insurance companies and GSEs with more than $250 billion in assets. A Credit Union Times database includes only one credit union with more than $50 billion in assets (Navy Federal Credit Union) and zero credit unions with more than $100 billion in assets.24 Many investment companies have more than $250 billion in assets under management; these are not assets they own, but rather assets that they invest at their customers' behest.

What Requirements Must Large Banks Comply With Under Enhanced Regulation?

All BHCs are subject to long-standing prudential (safety and soundness) regulation conducted by the Fed. The novelty in the Dodd-Frank Act was to create a group of specific prudential requirements that apply only to large banks.25 Some of these requirements related to capital and liquidity overlap with parts of the Basel III international agreement.

Under Title I of the Dodd-Frank Act, the Fed is responsible for administering EPR. It promulgates regulations implementing the regime (based on recommendations, if any, made by FSOC) and supervises firms subject to the regime. The Dodd-Frank regime is referred to as enhanced or heightened because it applies higher or more stringent standards to large banks than it applies to smaller banks. It is a prudential regime because the regulations are intended to contribute toward the safety and soundness of the banks subject to the regime. The cost to the Fed of administering the regime is financed through assessments on firms subject to the regime.

Some EPR provisions are intended to reduce the likelihood that a bank will experience financial difficulties, while others are intended to help regulators cope with a failing bank. Several of these provisions directly address problems or regulatory shortcomings that arose during the financial crisis. As of the date of this report, no bank has experienced financial difficulties since EPR came into effect, but the economy has not experienced a downturn in which financial difficulties at banks become more likely. Thus, the risk mitigation provisions that have shown robustness in an expansion have not yet proven to be robust in a downturn, while the provisions intended to cope with a failing bank remain untested. Finally, some parts of enhanced regulation cannot be evaluated because, as noted below, they still have not been implemented through final rules.

The following sections provide more detail on the requirements that Title I of the Dodd-Frank Act (which will be referred to hereinafter as Title 1) and Basel III place on banks subject to EPR.26 Subsequent to initial implementation, numerous regulatory changes over the years have tailored the individual provisions discussed in this section to reduce their regulatory burden; this report does not provide a comprehensive catalog of those subsequent changes.

Stress Tests and Capital Planning

Stress tests and capital planning are two enhanced requirements that have been implemented together. Title I requires company-run stress tests for any (bank or nonbank) financial firm with more than $10 billion in assets, which P.L. 115-174 raised to more than $250 billion in assets (with Fed discretion to apply to financial firms with between $100 billion and $250 billion in assets), and Fed-run (or "supervisory") stress tests (called DFAST) for any BHC or nonbank SIFI with more than $50 billion in assets, which P.L. 115-174 raised to more than $100 billion in assets. P.L. 115-174 also reduced the number of stress test scenarios and the frequency of company-run stress tests from semi-annually to periodically. Stress test and capital planning requirements were implemented through final rules in 2012, effective beginning in 2013.27

Stress tests attempt to project the losses that banks would suffer under a hypothetical deterioration in economic and financial conditions to determine whether banks would remain solvent in a future crisis. Unlike general capital requirements that are based on current asset values, stress tests incorporate an adverse scenario that focuses on projected asset values based on specific areas of concern each year. For example in 2017, the adverse scenario is "characterized by a severe global recession that is accompanied by a period of heightened stress in corporate loan markets and commercial real estate markets."28 In 2019, the Fed made changes to the stress test process to increase its transparency.29

Capital requirements are intended to ensure that a bank has enough capital backing its assets to absorb any unexpected losses on those assets without failing. Title I required enhanced capital requirements for banks with more than $50 billion in assets, which P.L. 115-174 raised to more than $250 billion in assets (with Fed discretion to apply to banks with between $100 billion and $250 billion in assets). Overall capital requirements were revamped through Basel III after the financial crisis (described below in the "Basel III Capital Requirements" section). Outside of Basel III, enhanced capital requirements were primarily implemented through capital planning requirements that are tied to stress test results.

The final rule for capital planning was implemented in 2011.30 Under the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR), banks must submit a capital plan to the Fed annually. The capital plan must include a projection of the expected uses and sources of capital, including planned debt or equity issuance and dividend payments. The plan must demonstrate that the bank will remain in compliance with capital requirements under the stress tests. The Fed evaluates the plan on quantitative (whether the bank would have insufficient capital under the stress tests) and qualitative grounds (the adequacy of bank's risk management policies and processes).

If the Fed rejects the bank's capital plan, the bank will not be allowed to make any capital distributions, including dividend payments, until a revised capital plan is resubmitted and approved by the Fed. In 2017, the Fed removed qualitative requirements from the capital planning process for banks with less than $250 billion in assets that are not complex.31 Each year, the Fed has required some banks to revise their capital plans or objected to them on qualitative or quantitative grounds, or due to other weaknesses in their processes.32

Resolution Plans ("Living Wills")

Policymakers claimed that one reason they intervened to prevent large financial firms from failing during the financial crisis was because the opacity and complexity of these firms made it too difficult to wind them down quickly and safely through bankruptcy. Title I requires banks with more than $50 billion in assets, which P.L. 115-174 raised to more than $250 billion in assets (with Fed discretion to apply to banks with between $100 billion and $250 billion in assets), to periodically submit resolution plans (popularly known as "living wills") to the Fed, FSOC, and FDIC that explain how they can safely enter bankruptcy in the event of their failures. The living wills requirement was implemented through a final rule in 2011, and it became fully effective at the end of 2013.33 The final rule required resolution plans to include details of the firm's ownership, structure, assets, and obligations; information on how the firm's depository subsidiaries are protected from risks posed by its nonbank subsidiaries; and information on the firm's cross-guarantees, counterparties, and processes for determining to whom collateral has been pledged. Proposed rules would reduce the frequency of living will submissions from annually to biennially for G-SIBs and triennially for other large banks.34

In the 2011 final rule, the regulators highlighted that the resolution plans would help them understand the firms' structure and complexity, as well as their resolution processes and strategies, including cross-border issues for banks operating internationally. The resolution plan is required to explain how the firm could be resolved under the bankruptcy code35—as opposed to being liquidated by the FDIC under the Orderly Liquidation Authority created by Title II of the Dodd-Frank Act.36 The plan is required to explain how the firm can be wound down in a stressed environment in a "rapidly and orderly" fashion without receiving "extraordinary support" from the government (as some firms received during the crisis) or without disrupting financial stability. To do so, the plan must include information on core business lines, funding and capital, critical operations, legal entities, information systems, and operating jurisdictions.

Resolution plans are divided into a public part that is disclosed and a private part that contains confidential information. Some banks have submitted resolution plans containing tens of thousands of pages. If regulators find that a plan is incomplete, deficient, or not credible, they may require the firm to revise and resubmit. If the firm cannot resubmit an adequate plan, regulators have the authority to take remedial steps against it—increasing its capital and liquidity requirements; restricting its growth or activities; or ultimately taking it into resolution. Since the process began in 2013, multiple firms' plans have been found insufficient, including all eleven that were submitted and subsequently resubmitted in the first wave. In 2016, Wells Fargo became the first bank to be sanctioned for failing to submit an adequate living will.37

Liquidity Requirements

Bank liquidity refers to a bank's ability to meet cash flow needs and readily convert assets into cash. Banks are vulnerable to liquidity crises because of the liquidity mismatch between illiquid loans and deposits that can be withdrawn on demand. Although all banks are regulated for liquidity adequacy, Title I requires more stringent liquidity requirements for banks with more than $50 billion in assets, which P.L. 115-174 raised to more than $250 billion in assets (with Fed discretion to apply to banks with between $100 billion and $250 billion in assets). These liquidity requirements are being implemented through three rules: (1) a 2014 final rule implementing firm-run liquidity stress tests, (2) a 2014 final rule implementing the Fed-run liquidity coverage ratio (LCR), and (3) a 2016 proposed rule that would implement the Fed-run net stable funding ratio (NSFR).38 The firm-run liquidity stress tests apply to domestic banks with more than $100 billion in assets under the Fed's proposed rule. More stringent versions of the LCR and NSFR apply to G-SIBs and Category II banks. A less stringent version applies to Category III banks, except those with significant insurance or commercial operations. Proposed rules would extend the LCR and NSFR to large foreign banks operating in the United States.39

The final rule implementing firm-run liquidity stress tests was issued in 2014, effective January 2015 for U.S. banks and July 2016 for foreign banks.40 The rule requires banks subject to EPR to establish a liquidity risk management framework involving a bank's management and board, conduct monthly internal liquidity stress tests, and maintain a buffer of high-quality liquid assets (HQLA).

The final rule implementing the liquidity coverage ratio was issued in 2014.41 The LCR came into effect at the beginning of 2015 and was fully phased in at the beginning of 2017. The LCR requires banks subject to EPR to hold enough HQLA to match net cash outflows over a 30-day period in a hypothetical scenario of market stress where creditors are withdrawing funds.42 An asset can qualify as a HQLA if it has lower risk, has a high likelihood of remaining liquid during a crisis, is actively traded in secondary markets, is not subject to excessive price volatility, can be easily valued, and is accepted by the Fed as collateral for loans. Different types of assets are relatively more or less liquid, and there is disagreement on what the cutoff point should be to qualify as a HQLA under the LCR. In the LCR, eligible assets are assigned to one of three categories, ranging from most to least liquid. Assets assigned to the most liquid category are given more credit toward meeting the requirement, and assets in the least liquid category are given less credit. Section 403 of P.L. 115-174 required regulators to place municipal bonds in a more liquid category, so that banks could get more credit under the LCR for holding them.

The proposed rule to implement the net stable funding ratio was issued in 2016, and to date has not been finalized.43 The NSFR would require banks subject to EPR to have a minimum amount of stable funding backing their assets over a one-year horizon. Different types of funding and assets would receive different weights based on their stability and liquidity, respectively, under a stressed scenario. The rule would define funding as stable based on how likely it is to be available in a panic, classifies it by type, counterparty, and time to maturity. Assets that do not qualify as HQLA under the LCR would require the most backing by stable funding under the NSFR. Long-term equity would get the most credit toward fulfilling the NSFR, insured retail deposits get medium credit, and other types of deposits and long-term borrowing would get less credit. Borrowing from other financial institutions, derivatives, and certain brokered deposits would not qualify under the rule.

Counterparty Exposure Limits

One source of systemic risk associated with TBTF comes from "spillover effects." When a large firm fails, it imposes losses on its counterparties. If large enough, the losses could be debilitating to the counterparty, thus causing stress to spread to other institutions and further threaten financial stability. Title I requires banks with more than $50 billion in assets, which P.L. 115-174 raised to more than $250 billion in assets (with Fed discretion to apply to banks with between $100 billion and $250 billion in assets), to limit their exposure to unaffiliated counterparties on an individual counterparty basis and to periodically report on their credit exposures to counterparties. Counterparty exposure limits remain mandatory, but P.L. 115-174 placed credit exposure reports at the Fed's discretion. In 2011, the Fed proposed rules implementing these provisions, but they were not included in subsequent final rules.44 In 2018, the Fed finalized a reproposed rule to implement a single counterparty credit limit (SCCL), effective in 2020; to date, the counterparty exposure reporting requirement has not been reproposed.45

Counterparty exposure for all banks was subject to regulation before the crisis, but did not cover certain off balance sheet exposures or holding company level exposures.46 The SCCL is tailored to have increasingly stringent requirements as asset size increases. For banks with more than $250 billion in total assets that are not G-SIBs, net counterparty credit exposure is limited to 25% of the bank's capital. For G-SIBs, counterparty exposure to another G-SIB or a nonbank SIFI is limited to 15% of the G-SIB's capital and exposure to any other counterparty is limited to 25% of its capital.

The 2011 credit exposure reporting proposal would have required banks to regularly report on the nature and extent of their credit exposures to significant counterparties. These reports would help regulators understand spillover effects if firms experienced financial distress. There has been no subsequent rulemaking on credit exposure reporting since the 2011 proposal.47

Risk Management Requirements

The board of directors of publicly traded companies oversees the company's management on behalf of shareholders. The Dodd-Frank Act required publicly traded banks with at least $10 billion in assets, which P.L. 115-174 raised to at least $50 billion in assets, to form risk committees on their boards of directors that include a risk management expert responsible for oversight of the bank's risk management. Title I also requires the Fed to develop overall risk management requirements for banks with more than $50 billion in assets. The Fed issued the final rule implementing this provision in 2014, effective in January 2015 for domestic banks and July 2016 for foreign banks.48 The rule requires the risk committee be led by an independent director. The rule requires banks with more than $50 billion in assets to employ a chief risk officer responsible for risk management, which the proposed rule implementing P.L. 115-174 leaves unchanged.

Provisions Triggered in Response to Financial Stability Concerns

Title I of the Dodd-Frank Act provides several powers for—depending on the provision—FSOC, the Fed, or the FDIC to use when the respective entity believes that a bank with more than $50 billion in assets or designated nonbank SIFI poses a threat to financial stability. Unless otherwise noted, P.L. 115-174 raises the threshold at which the powers can be applied to banks with $250 billion in assets, with no discretion to apply them to banks between $100 billion and $250 billion in assets. Unlike the enhanced regulation requirements described earlier in this section, financial stability provisions generally do not require any ongoing compliance and would be triggered only when a perceived threat to financial stability has arisen—and none of these provisions have been triggered to date.

Some of the following powers are similar to powers that bank regulators already have over all banks, but they are new powers over nonbank SIFIs. These powers are listed here because they, to varying degrees, expand regulatory authority over banks (or extend authority from bank subsidiaries to bank holding companies) with more than $250 billion in assets vis-a-vis smaller banks.

FSOC Reporting Requirements. To determine whether a bank with more than $250 billion in assets poses a threat to financial stability, FSOC may require the bank to submit certified reports. However, FSOC may make information requests only if publicly available information is not available.

Mitigation of Grave Threats to Financial Stability. When at least two-thirds of the FSOC find that a bank with more than $250 billion in assets poses a grave threat to financial stability, the Fed may limit the firm's mergers and acquisitions, restrict specific products it offers, and terminate or limit specific activities. If none of those steps eliminates the threat, the Fed may require the firm to divest assets. The firm may request a Fed hearing to contest the Fed's actions. To date, this provision has not been triggered, and the FSOC has never identified any bank as posing a grave threat.

Acquisitions. Title I broadens the requirement for banks with more than $250 billion in assets to provide the Fed with prior notice of U.S. nonbank acquisitions that exceed $10 billion in assets and 5% of the acquisition's voting shares, subject to various statutory exemptions. The Fed is required to consider whether the acquisition would pose risks to financial stability or the economy.

Emergency 15-to-1 Debt-to-Equity Ratio. For banks with more than $250 billion in assets, with Fed discretion to apply to banks with between $100 billion and $250 billion in assets, Title I creates an emergency limit of 15-to-1 on the bank's ratio of liabilities to equity capital (sometimes referred to as a leverage ratio).49 The Fed issued a final rule implementing this provision in 2014, effective June 2014 for domestic banks and July 2016 for foreign banks.50 The ratio is applied only if a bank receives written warning from FSOC that it poses a "grave threat to U.S. financial stability," and ceases to apply when the bank no longer poses a grave threat. To date, this provision has not been triggered.

Early Remediation Requirements. Early remediation is the principle that financial problems at banks should be addressed early before they become more serious. Title I requires the Fed to "establish a series of specific remedial actions" to reduce the probability that a bank with more than $250 billion in assets experiencing financial distress will fail. This establishes a requirement for BHCs similar in spirit to the prompt corrective action requirements that apply to insured depository subsidiaries. Unlike prompt corrective action, early remediation requirements are not based solely on capital adequacy. As the financial condition of a firm deteriorates, statute requires the steps taken under early remediation to become more stringent, increasing in four steps from heightened supervision to resolution. The Fed issued a proposed rule in 2011 to implement this provision that to date has not been finalized.51

Expanded FDIC Examination and Enforcement Powers. Title I expands the FDIC's examination and enforcement powers over certain large banks. To determine whether an orderly liquidation under Title II of the Dodd-Frank Act is necessary, the FDIC is granted authority to examine the condition of banks with more than $250 billion in assets. Title I also grants the FDIC enforcement powers over BHCs or THCs that pose a risk to the Deposit Insurance Fund.

Basel III Capital Requirements

Parallel to the Dodd-Frank Act, Basel III reformed bank regulation after the financial crisis. U.S. bank regulators implemented this nonbinding international agreement through rulemaking.52 Basel III determined many of the current capital requirements applied to all U.S. banks. Capital requirements are intended to ensure that a bank has enough capital backing its assets to absorb any unexpected losses on those assets without resulting in the bank's insolvency. Basel III did not include enhanced capital requirements at the original $50 billion threshold, but it did include more stringent capital requirements for the largest banks. The following Basel III capital requirements apply only to large banks:

Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR). Leverage ratios determine how much capital banks must hold relative to their assets without adjusting for the riskiness of their assets. Banks with more than $250 billion in assets or more than $10 billion in foreign exposure must meet a 3% SLR, which differs from the leverage ratio that applies to all banks by including the bank's off-balance-sheet exposures. Unanticipated losses related to opaque off-balance-sheet exposures exacerbated uncertainty about banks' solvency during the financial crisis. In April 2014, U.S. bank regulators adopted a joint rule that would require the G-SIBs to meet an enhanced SLR of 5% at the holding company level to pay all discretionary bonuses and capital distributions and 6% at the depository subsidiary level to be considered well capitalized as of 2018.53 The amount of capital required by the SLR and to whom it applies would be modified by proposed rules discussed below.

G-SIB Capital Surcharge. Basel III also required G-SIBs to hold relatively more capital than other banks in the form of a common equity surcharge of at least 1% to "reflect the greater risks that they pose to the financial system."54 In July 2015, the Fed issued a final rule that began phasing in this capital surcharge in 2016.55 Currently, the surcharge applies to the eight G-SIBs, but under its rule, it could designate additional firms as G-SIBs, and it could increase the capital surcharge to as high as 4.5%. The Fed stated that under its rule, most G-SIBs would face a higher capital surcharge than required by Basel III.

Countercyclical Capital Buffer. The banking regulators also issued a final rule implementing a Basel III countercyclical capital buffer applied to banks with more than $250 billion in assets or more $10 billion in foreign exposure. The countercyclical buffer requires these banks to hold more capital than other banks when regulators believe that financial conditions make the risk of losses abnormally high. It has been set at zero since inception.56 Because the countercyclical buffer has not yet been in place for a full business cycle,57 it is unclear how likely it is that regulators would raise it above zero, and under what circumstances an increase would be triggered.

Total Loss-Absorbing Capacity (TLAC). The Fed issued a 2017 final rule implementing a TLAC requirement for U.S. G-SIBs and U.S. operations of foreign G-SIBs effective at the beginning of 2019.58 The rule requires G-SIBs to hold a minimum amount of capital and long-term debt at the holding company level so that these equity and debt holders can absorb losses and be "bailed in" in the event of the firm's insolvency. This furthers the policy goal of avoiding taxpayer bailouts of large financial firms. TLAC would be affected by a proposed rule discussed below.

These capital requirements determine how the largest banks must fund all of their activities on a day-to-day basis. In that sense, these requirements arguably have a larger ongoing impact on banks' marginal costs of providing credit and other services than most of the Title I provisions discussed in the last section that impose only fixed compliance costs on banks.59

Assessments

The Dodd-Frank Act imposes various assessments on banks with more than $50 billion in assets. P.L. 115-174 raised the threshold for some of these assessments. As amended, fees are assessed on

- BHCs with more than $250 billion in assets (beginning in November 2019) and designated SIFIs to fund the Office of Financial Research;

- BHCs and THCs with assets over $100 billion and designated SIFIs to fund the cost of administering EPR. Assessments on BHCs and THCs with $100 billion to $250 billion in assets must reflect the tailoring of EPR; and

- BHCs with assets over $50 billion and designated SIFIs to repay any uncompensated costs borne by the government in the event of a liquidation under the Orderly Liquidation Authority.60 This assessment is imposed only after a liquidation occurs.

Proposed Changes to Large Bank Regulation

As of the date of this report, the Fed and the other bank regulators have proposed several rules that would modify EPR

- One set of rules, implementing Section 401 of P.L. 115-174, would raise the asset thresholds for EPR. This rule would exempt banks with less than $100 billion in assets from EPR and reduce EPR requirements mostly for banks with between $100 billion and $250 billion in assets.

- A second proposed rule, implementing Section 402 of P.L. 115-174, would reduce capital requirements under the SLR for three custody banks, two of which are G-SIBs.

- Two other rules were proposed independently of any legislative action

- One would combine elements of stress tests requirements and Basel III to create a stress capital buffer requirement for large banks, effectively reducing capital requirements mainly for large banks that are not G-SIBs.

- The other would reduce capital requirements under the SLR for G-SIBs by changing how the SLR is calculated.

This section summarizes these proposed rules and their projected effects.

Higher, Tiered Thresholds

Prior to the enactment of P.L. 115-174, U.S. regulators described the prudential regulatory regime applying to all banks as tiered regulation, meaning that increasingly stringent regulatory requirements are applied as metrics, such as a bank's size, increase.61 These different tiers have been applied on an ad hoc basis—in some cases, statute requires a given regulation to be applied at a certain size; in some cases, regulators have discretion to apply a regulation at a certain size; and in other cases, regulators must apply a regulation to all banks. In addition to $100 billion and $250 billion, notable thresholds found in bank regulation are $1 billion, $3 billion, $5 billion, and $10 billion. P.L. 115-174 expanded tiered regulation for EPR and other types of bank regulation (see text box).

|

Size Thresholds Outside of EPR Besides enhanced regulation, size thresholds are also used in other regulations. For example, by statute, only banks with more than $10 billion in assets are subject to the Durbin Amendment,62 which caps debit interchange fees, and supervision by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau for consumer compliance. Pursuant to the Dodd-Frank Act, executive compensation rules for financial firms apply to only firms with more than $1 billion in assets by statute, with more stringent requirements for firms with more than $50 billion and $250 billion proposed by regulation. P.L. 115-174 created or increased several other asset thresholds used in bank regulation outside of EPR. For example, it exempted banks from the Volcker Rule if they had less than $10 billion in assets and trading assets and liabilities less than 5% of total assets.63 It also created a new Community Bank Leverage Ratio. Banks with less than $10 billion in assets that wish to opt out of complying with Basel III capital rules are allowed to do so if they meet the Community Bank Leverage Ratio. It also created or increased small bank exemptions or tailoring for holding mortgages, call reporting requirements, thrift regulation, holding company capital requirements, and frequency of bank exams.64 |

Even before enactment of P.L. 115-174, EPR was itself an example of tiered regulation, as it imposed requirements only on banks with more than $50 billion in assets, banks with $250 billion in assets, or G-SIBs, depending on the requirement. Before P.L. 115-174, the Fed's rules had also tailored some of the EPR requirements for banks with more than $50 billion in assets, so that more stringent regulatory or compliance requirements were applied to banks with more than $250 billion in assets or G-SIBs, depending on the requirement.

Under P.L. 115-174, EPR would become much more tiered and tailored by bank size. The Fed has proposed rules that would implement changes to bank asset thresholds and specific EPR requirements found in P.L. 115-174 and would make additional changes to EPR requirements using the discretionary authority provided in P.L. 115-174. Under these proposed rules, EPR would impose progressively more stringent requirements across four categories of banks, as summarized in Table 3.65 As proposed, the Fed used the discretion granted by P.L. 115-174 to exempt banks with $100 billion to $250 billion from most, but not all, EPR requirements unless they had other characteristics that made them qualify as Category II or III banks. Consistent with P.L. 115-174, banks with under $100 billion would be exempted from all EPR requirements except those related to risk management.

|

Requirement |

Category I (G-SIBs) |

Category II (>$700B assets or see notes) |

Category III (>$250B or see notes) |

Category IV (Other $100B-$250B) |

Uncategorized ($50B-$100B) |

|

Provisions previously applied to BHCs with > $10B assets: |

|||||

|

Company-run stress tests |

annual |

annual |

biannual |

none |

none |

|

Risk committee |

applies |

applies |

applies |

applies |

applies |

|

Provisions previously applied to BHCs with > $50B assets: |

|||||

|

Fed-run stress tests |

annual, quantitative and qualitative |

annual, quantitative and qualitative |

annual, quantitative and qualitative |

biannual, quantitative |

none |

|

Capital plan |

annual |

annual |

annual |

annual |

none |

|

Living wills |

biennial |

triennial |

triennial |

nonea |

nonea |

|

Firm-run liquidity stress test |

more stringent |

more stringent |

more stringent |

less stringent |

none |

|

LCR |

more stringent |

more stringent |

less stringentb |

nonec |

none |

|

NSFR |

more stringent |

more stringent |

less stringentb |

nonec |

none |

|

SCCL |

more stringent |

less stringent |

less stringent |

none |

none |

|

Chief risk officer |

applies |

applies |

applies |

applies |

applies |

|

Emergency provisions |

applies |

applies |

applies |

none |

none |

|

Subject to assessments for: |

OFR, EPR, OLA |

OFR, EPR, OLA |

OFR, EPR, OLA |

EPR (less stringent), OLA |

OLA |

|

Provisions previously applied to BHCs with > $250B assets or >$10B in foreign exposure: |

|||||

|

SLR |

more stringent (eSLR) |

less stringent |

less stringent |

none |

none |

|

Advanced Approaches |

applies |

applies |

none |

none |

none |

|

AOCI included in capital calculation |

mandatory |

mandatory |

optional |

optional |

optional |

|

Countercyclical capital buffer |

applies |

applies |

applies |

none |

none |

|

Provisions previously applied to G-SIBs: |

|||||

|

TLAC |

applies |

none |

none |

none |

none |

|

G-SIB capital surcharge |

applies |

none |

none |

none |

none |

Source: The Congressional Research Service (CRS).

Notes: LCR = Liquidity Coverage Ratio, NSFR = Net Stable Funding Ratio, SCCL = Single Counterparty Credit Limit, SLR = Supplementary Leverage Ratio, G-SIB = Global Systemically Important Bank, AOCI = Accumulated and Other Comprehensive Income, TLAC = Total Loss Absorbency Capacity, OFR = Office of Financial Research, EPR = Enhanced Prudential Regulation, OLA = Orderly Liquidation Authority, IHC = Intermediate Holding Company. Banks by category are listed in Table 1 and Table 2. Banks under $700 billion in assets are ranked as Category II if they have over $75 billion in cross-jurisdictional activity. Banks under $250 billion in assets are ranked as Category III if they had more than $75 billion in nonbank assets, weighted short-term wholesale funding, or off-balance sheet exposure. Previously applied thresholds refers to rules under the Dodd-Frank Act and Basel III before amendments from P.L. 115-174, as applied to U.S. banks. For brevity, this table does not specify whether each requirement is applied to a foreign bank's IHC or total U.S. operations.

a. Foreign banks in these categories face a less stringent requirement.

b. Category III banks with >$75 billion in weighted short-term wholesale funding face the more stringent version of the rule.

c. Foreign Category IV banks with >$50 billion in weighted short-term wholesale funding face the less stringent version of the rule.

Under proposed rules, foreign banks would be placed in the same categories, based on their U.S. assets, with requirements for each category similar to those applied to U.S. banks.66 In most cases, compared to the status quo for foreign banks, EPR requirements for foreign banks in Category II and III (see Table 2) would remain largely unchanged, whereas foreign banks with an IHC in Category IV would be exempted from or face less stringent versions of most EPR requirements, depending on the requirement. Most requirements would continue to be applied to the U.S. IHC, but a few would apply to all U.S. operations, including U.S. branches and agencies. Because assets of U.S. branches and agencies were not used to determine who was subject to EPR previously, the proposed rule would apply a few EPR requirements to foreign banks that were not previously subject to EPR. But overall the proposed rules would mostly continue to defer to home country regulation for foreign banks operating in the United States that do not qualify as Category II or III banks.

Stress Capital Buffer

Stress tests and capital planning requirements play a specific role in EPR—they provide the Fed with an assessment of whether large banks have enough capital to withstand another crisis, as simulated using a specific adverse scenario developed by the Fed. This is similar to the role of capital requirements more generally and creates some overlap and redundancy between the two. More generally, the Fed points out that banks with more than $100 billion in assets must simultaneously comply with 18 capital requirements and G-SIBs must simultaneously comply with 24 different capital requirements, each addressing a separate but related risk.67

To try to minimize what it perceives as redundancy between these various measures, the Fed has proposed a rule to combine elements of the stress tests and the Basel III requirements.68 Under the proposed rule, banks with more than $100 billion in assets would have to simultaneously comply with 8 capital requirements and G-SIBs would have to simultaneously comply with 14 capital requirements. The proposed rule would accomplish this by eliminating 5 requirements tied to the "adverse" scenario in the stress tests, which the Fed is allowed to do under P.L. 115-174, and by combining 4 requirements tied to the "severely adverse" stress tests with 4 Basel III capital requirements.

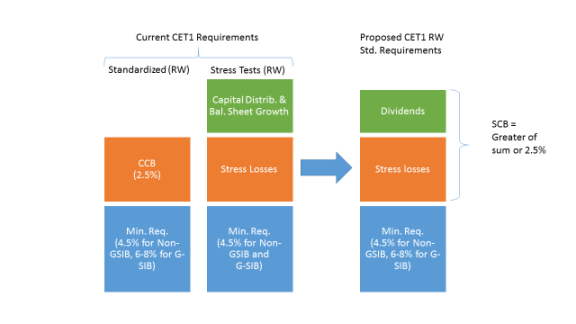

Under current Basel III risk-weighted capital requirements, all banks must hold a common equity capital conservation buffer (CCB) equal to 2.5% of their risk-weighted assets (on top of the minimum amount of common equity, Tier 1, and total capital required) to avoid limitations on capital distributions. They also must meet an unweighted leverage capital requirement. Under capital planning requirements, banks currently must hold enough capital to still meet the minimum amount required under the common equity, Tier 1, and total capital, and leverage requirements after their stress test losses, planned capital distributions (such as dividends and share buybacks), and projected balance sheet growth (because an increase in assets requires a proportional increase in capital).

The proposed rule would replace these separate requirements with a combined stress capital buffer (SCB) requirement that banks hold enough capital to cover stress test losses and dividends or 2.5% of risk-weighted assets, whichever is larger (see Figure 1). The former is less restrictive than what banks face if their projected capital levels fall below the minimum under current stress test requirements. The Fed has provided three justifications for making these requirements less stringent than the current capital planning requirements. First, the Fed argues that because capital distributions would automatically face restrictions if the proposed stress capital buffer was not met, it would no longer be necessary for firms to hold enough capital to meet all planned capital distributions. However, distributions are not entirely forbidden unless the stress capital buffer falls below 0.625%. Second, the Fed argues for removing stock repurchases from capital planning on the grounds that only dividends are likely to be continued as planned in a period of financial stress. Finally, the Fed argues that its previous assumption that balance sheets continue to grow in a stressed environment was an unreasonable one.69

Because the Fed decided that banks would no longer have to hold capital to account for capital distributions other than dividends and balance sheet growth, they have reduced capital requirements relative to current stress tests for non G-SIBs. However, whether the stress capital buffer would be a lower capital requirement than the stress tests and the risk-weighted Basel III requirements it is replacing depends on whether losses under the stress tests were greater than 2.5%. If they were less than 2.5%, then a bank is required to hold the same amount of capital under the proposal as currently under the capital conservation buffer. If they were more than 2.5%, then a bank is required to hold less capital under the proposal than currently under the stress tests.70

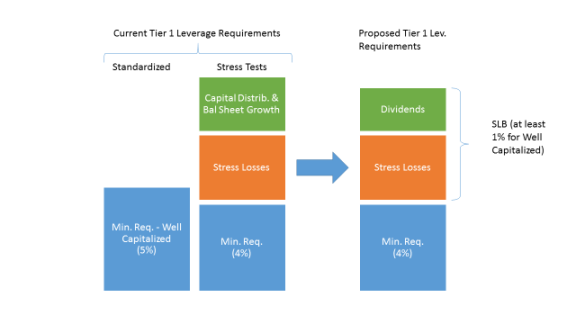

Under the proposal, banks would also face a stress leverage buffer in lieu of the leverage ratio.71 The stress leverage buffer would require large banks to hold Tier 1 capital equal to stress tests losses and dividends, but the leverage buffer would not include any minimum (see Figure 2).72 Currently, the leverage ratio does not include a buffer requirement, although banks must hold an additional 1% of capital to be considered well capitalized under prompt-corrective action requirements. So in this case, whether the stress leverage buffer would be a lower capital requirement than the stress tests and Basel III leverage requirements it is replacing depends on whether losses, planned capital distributions, and projected balance sheet growth under the stress tests were greater than 1%—which the Fed reports is generally the case.73

These proposed buffers would work similarly to the CCB, in that capital restrictions would be automatically triggered if a bank's capital level falls below the buffers. It would not feature the annual quantitative "pass/fail" announcement that is a current feature of the stress tests.

|

Figure 2. Leverage Capital Requirements, Current and Proposed Tier 1 Capital |

|

|

Source: CRS. Notes: SLB = Stress Leverage Buffer. |

The Fed calculated what would have happened if this proposed rule had been in place in recent years. It found that the proposed rule would have reduced required capital for large banks that are not G-SIBs (because the stress test is currently the binding constraint) by between $10 billion and $45 billion74 and would have required G-SIBs to hold the same or more capital (because the G-SIB surcharge is being added to the stress capital buffer); overall, capital requirements for G-SIBs would have increased by between $10 billion and $50 billion. The Fed also found that all banks would have had enough actual capital in those years to meet the SCB requirement.

|

What is a "Binding" Capital Requirement? When banks face multiple capital requirements, the minimum amount of capital that they are required to hold is determined by whichever capital requirement is the "binding" one. Conceptually, whichever of the 18 or 24 different capital requirements that large banks or G-SIBs, respectively, must currently comply with requires the most capital to meet the minimum requirement becomes the only one that determines the bank's overall required capital (because all of the others require less capital than that one).75 The binding requirement will vary from bank to bank depending on the types of capital and assets it holds. Typically, a bank aims to hold enough capital to always stay comfortably above whatever amount is required by the binding ratio. Three of the proposals discussed in this report involve changes to specific capital requirements. Reducing or combining individual capital requirements does not necessarily mean that large banks will have to hold less capital. That depends on three factors: (1) which capital requirement is currently binding? (2) which capital requirement would become binding under the proposal? (3) does the proposal also make changes to the newly binding capital requirement that would increase or reduce the amount of capital that banks must hold? Proposals to change capital requirements will reduce how much capital a bank is required to hold overall if the proposal reduces the amount of capital required under the capital requirement that is binding under the proposal. By contrast, if a proposal reduces a requirement that is not binding before or after the change, it will not change how much capital a bank is required to hold. |

Treatment of Custody Banks Under the Supplementary Leverage Ratio

Custody banks provide a unique set of services not offered by many other banks, but are generally subject to the same regulatory requirements as other banks. Custody banks hold securities; receive interest or dividends on those securities; provide related administrative services; and transfer ownership of securities on behalf of financial market asset managers, including investment companies such as mutual funds. Asset managers access central counterparties and payment systems via custodian banks. Custodian banks play a passive role in their clients' decisions, carrying out instructions. As discussed in the "Basel III Capital Requirements" section above, under leverage ratios, including the SLR, the same amount of capital must be held against any asset, irrespective of risk to ensure that banks have a minimum amount of total capital. Banks must hold capital against their deposits at central banks under the leverage or supplemental leverage ratio, although there is no risk associated with those deposits. Custody banks argue that this disproportionately burdens them because of their business model.76 Other observers counter that the purpose of the leverage ratio is to measure the amount of bank capital against assets regardless of risk, and to exempt "safe" assets undermines the usefulness of that measure.77

Section 402 of P.L. 115-174 allows for custody banks—defined by the legislation as banks predominantly engaged in custody, safekeeping, and asset servicing activities—to no longer hold capital against funds deposited at certain central banks78 to meet the SLR, up to an amount equal to customer deposits linked to fiduciary, custodial, and safekeeping accounts.79 All other banks would continue to be required to hold capital against central bank deposits. In April 2019, the banking regulators proposed a rule to implement this provision.80

Custody banks are generally an industry concept, not a regulatory concept. P.L. 115-174 leaves it to bank regulators to define which banks meet the definition of "predominantly engaged in custody, safekeeping, and asset servicing activities." The proposed rule uses a ratio of at least 30 times more assets under custody than the banks' assets to determine "predominantly engaged."81 By this measure, three banks would qualify—Bank of New York Mellon, Northern Trust, and State Street. Depending on who qualifies in the final rule, other large banks that offer custody services but do not qualify for relief under the "predominantly engaged" definition may be at a relative disadvantage under this provision. Under the proposed rule, Northern Trust would be able to reduce its capital by $3 for every $100 it deposits at central banks, and Bank of New York Mellon and State Street (as G-SIBs) would be able to reduce their capital by $6 for every $100 of banking subsidiary deposits at central banks—although the latter two would face a lower leverage ratio under the enhanced SLR proposed rule discussed in the next section.

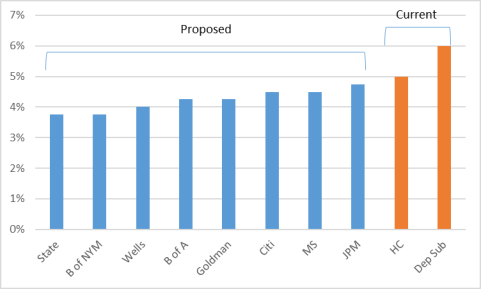

The proposed rule implementing Section 402 estimates that the three eligible custody banks would be granted an exclusion equivalent to 21% to 30% of their assets and be able to reduce their capital requirements at the holding company level under the SLR by an aggregate $8 billion. However, the proposed rule states that the SLR was not the binding capital requirement for the custody banks at the holding company level, but it was the binding requirement at the depository level for two of the banks, as of the third quarter of 2018. As a result, capital requirements would have declined by a combined $7 billion or 23% for those two banks had the rule been in effect.82

Incorporating the G-SIB Surcharge into the Enhanced Supplementary Leverage Ratio and the Total Loss Absorbing Capacity

As noted in the "Basel III Capital Requirements" section, G-SIBs must currently comply with a higher SLR than other banks with $250 billion in assets. For G-SIBs, the current enhanced SLR is set at 5% at the holding company level and 6% for the depository subsidiary to be considered well capitalized.