The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act: Background and Summary

Beginning in 2007, U.S. financial conditions deteriorated, leading to the near-collapse of the U.S. financial system in September 2008. Major commercial banks, insurers, government-sponsored enterprises, and investment banks either failed or required hundreds of billions in federal support to continue functioning. Households were hit hard by drops in the prices of real estate and financial assets, and by a sharp rise in unemployment. Congress responded to the crisis by enacting the most comprehensive financial reform legislation since the 1930s.

Then-Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner issued a reform plan in the summer of 2009 that served as a template for legislation in both the House and Senate. After significant congressional revisions, President Obama signed H.R. 4173, now titled the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 111-203), into law on July 21, 2010.

Perhaps the major issue in the financial reform legislation was how to address the systemic fragility revealed by the crisis. The Dodd-Frank Act created a new regulatory umbrella group chaired by the Treasury Secretary—the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC)—with authority to designate certain financial firms as systemically important and subjecting them and all banks with more than $50 billion in assets to heightened prudential regulation. Financial firms were also subjected to a special resolution process (called “Orderly Liquidation Authority”) similar to that used in the past to address failing depository institutions following a finding that their failure would pose systemic risk.

The Dodd-Frank Act made other changes to the regulatory structure. It created the Office of Financial Research to support FSOC. The act consolidated consumer protection responsibilities in a new Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (CFPB). It consolidated bank regulation by reassigning the Office of Thrift Supervision’s (OTS’s) responsibilities to the other banking regulators. A federal office was created to monitor insurance. The Federal Reserve’s emergency authority was amended, and its activities were subjected to greater public disclosure and oversight by the Government Accountability Office (GAO).

Other aspects of Dodd-Frank addressed particular sectors of the financial system or selected classes of market participants. Dodd-Frank required more derivatives to be cleared and traded through regulated exchanges, reporting for derivatives that remain in the over-the-counter market, and registration with appropriate regulators for certain derivatives dealers and large traders. Hedge funds were subject to new reporting and registration requirements. Credit rating agencies were subject to greater disclosure and legal liability provisions, and references to credit ratings were required to be removed from statute and regulation. Executive compensation and securitization reforms attempted to reduce incentives to take excessive risks. Securitizers were subject to risk retention requirements, popularly called “skin in the game.” It made changes to bank regulation to make bank failures less likely in the future, including prohibitions on certain forms of risky trading (known as the “Volcker Rule”). It created new mortgage standards in response to practices that caused problems in the foreclosure crisis.

This report reviews issues related to financial regulation and provides brief descriptions of major provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act, along with links to CRS products going in to greater depth on specific issues. It does not attempt to track the legislative debate in the 115th Congress.

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act: Background and Summary

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Legislative History

- Financial Crisis

- The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-203)

- Systemic Risk

- Financial Crisis Context

- Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Titles I and VIII)

- Federal Reserve

- Financial Crisis Context

- Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title XI)

- Resolution Regime for Failing Firms

- Financial Crisis Context

- Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title II)

- Securitization

- Financial Crisis Context

- Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title IX)

- Bank Regulation

- Financial Crisis Context

- Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title I, III, VI, and X)

- Consumer Financial Protection

- Financial Crisis Context

- Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title X)

- Mortgage Standards

- Financial Crisis Context

- Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title XIV)

- Derivatives

- Financial Crisis Context

- Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Titles VII and XVI)

- Credit Rating Agencies

- Financial Crisis Context

- Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title IX)

- Investor Protection

- Financial Crisis Context

- Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title IX)

- Hedge Funds

- Financial Crisis Context

- Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title IV)

- Executive Compensation and Corporate Governance

- Financial Crisis Context

- Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title IX)

- Insurance

- Financial Crisis Context

- Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title V)

- Miscellaneous Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act

Tables

Summary

Beginning in 2007, U.S. financial conditions deteriorated, leading to the near-collapse of the U.S. financial system in September 2008. Major commercial banks, insurers, government-sponsored enterprises, and investment banks either failed or required hundreds of billions in federal support to continue functioning. Households were hit hard by drops in the prices of real estate and financial assets, and by a sharp rise in unemployment. Congress responded to the crisis by enacting the most comprehensive financial reform legislation since the 1930s.

Then-Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner issued a reform plan in the summer of 2009 that served as a template for legislation in both the House and Senate. After significant congressional revisions, President Obama signed H.R. 4173, now titled the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 111-203), into law on July 21, 2010.

Perhaps the major issue in the financial reform legislation was how to address the systemic fragility revealed by the crisis. The Dodd-Frank Act created a new regulatory umbrella group chaired by the Treasury Secretary—the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC)—with authority to designate certain financial firms as systemically important and subjecting them and all banks with more than $50 billion in assets to heightened prudential regulation. Financial firms were also subjected to a special resolution process (called "Orderly Liquidation Authority") similar to that used in the past to address failing depository institutions following a finding that their failure would pose systemic risk.

The Dodd-Frank Act made other changes to the regulatory structure. It created the Office of Financial Research to support FSOC. The act consolidated consumer protection responsibilities in a new Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (CFPB). It consolidated bank regulation by reassigning the Office of Thrift Supervision's (OTS's) responsibilities to the other banking regulators. A federal office was created to monitor insurance. The Federal Reserve's emergency authority was amended, and its activities were subjected to greater public disclosure and oversight by the Government Accountability Office (GAO).

Other aspects of Dodd-Frank addressed particular sectors of the financial system or selected classes of market participants. Dodd-Frank required more derivatives to be cleared and traded through regulated exchanges, reporting for derivatives that remain in the over-the-counter market, and registration with appropriate regulators for certain derivatives dealers and large traders. Hedge funds were subject to new reporting and registration requirements. Credit rating agencies were subject to greater disclosure and legal liability provisions, and references to credit ratings were required to be removed from statute and regulation. Executive compensation and securitization reforms attempted to reduce incentives to take excessive risks. Securitizers were subject to risk retention requirements, popularly called "skin in the game." It made changes to bank regulation to make bank failures less likely in the future, including prohibitions on certain forms of risky trading (known as the "Volcker Rule"). It created new mortgage standards in response to practices that caused problems in the foreclosure crisis.

This report reviews issues related to financial regulation and provides brief descriptions of major provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act, along with links to CRS products going in to greater depth on specific issues. It does not attempt to track the legislative debate in the 115th Congress.

Introduction

In response to problems raised by the 2007-2009 financial crisis, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 20101 (Dodd-Frank) was enacted on July 21, 2010. Since enactment, there has been congressional debate over whether—and how much—the act should be amended. Proponents believe that Dodd-Frank has successfully created a more stable financial system and better protected consumers and investors, while opponents believe that the act is partly to blame for restricted credit availability and the sluggish economic recovery that, in some ways, persists to this day. It should be noted that while Dodd-Frank is the largest source of new financial regulations since the crisis, it is not the only one.2

This report provides a brief summary of the major provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act and how they relate to the financial crisis. It begins with a table (Table 1) listing the financial regulators discussed in the report, followed by a summary of the act's legislative history and the financial crisis.

|

Name/Acronym |

Composition/General Responsibilities |

|

Regulators |

|

|

Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) |

Regulation of derivatives markets |

|

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) |

Regulation of financial products for consumer protection |

|

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) |

Provision of deposit insurance, regulation of banks, receiver for failing banks |

|

Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) |

Regulation of housing-government sponsored enterprises |

|

Federal Reserve System (Fed) |

Monetary policy; regulation of banks, systemically important financial institutions, and the payment system |

|

Federal Trade Commission (FTC) |

Regulation of nondepository lending institutions prior to the Dodd-Frank Act |

|

National Credit Union Administration (NCUA) |

Provision of deposit insurance, regulation of credit unions, receiver for failing credit unions |

|

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) |

Regulation of banks |

|

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) |

Regulation of securities markets |

|

Other Federal Financial Entities |

|

|

Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) |

Council of financial regulators and state and industry representatives accountable for financial stability |

|

Office of Financial Research (OFR) |

Provides research support to FSOC |

|

Federal Insurance Office (FIO) |

Monitors insurance industry and represents federal interests in insurance |

Source: Table compiled by the Congressional Research Service (CRS).

Legislative History

The 111th Congress considered several proposals to reorganize financial regulators and to reform the regulation of financial markets and financial institutions. Following House committee markups on various bills addressing specific issues, then-Chairman Barney Frank of the House Committee on Financial Services introduced the Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2009 (H.R. 4173), incorporating elements of numerous previous bills.3 After two days of floor consideration, the House passed H.R. 4173 on December 11, 2009, on a vote of 232-202.

Then-Chairman Christopher Dodd of the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs issued a single comprehensive committee print on November 16, 2009, the Restoring American Financial Stability Act of 2009. This proposal was revised over the following months, and the Restoring American Financial Stability Act of 2010 was marked up in committee on March 22, 2010, and reported as S. 3217 on April 15, 2010. The full Senate took up S. 3217 and amended it several times, finishing consideration on May 20, 2010, when it substituted the text of S. 3217 into H.R. 4173. The Senate then passed its version of H.R. 4173 on a vote of 59-39.

Following a conference committee, the House on June 30, 2010, agreed to the H.R. 4173 conference report by a vote of 237-192. The Senate agreed to the report on July 15, 2010, by a vote of 60-39. The legislation was signed into law on July 21, 2010, as P.L. 111-203.

In addition to Chairman Dodd's and Chairman Frank's bills, other proposals were made but not scheduled for markup. For example, then-House Financial Services Committee Ranking Member Spencer Bachus introduced a comprehensive reform proposal, the Consumer Protection and Regulatory Enhancement Act (H.R. 3310), and offered a similar amendment (H.Amdt. 539) during House consideration of H.R. 4173. In March 2008, then-Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson issued a "Blueprint for a Modernized Financial Regulatory Structure."4 The Obama Administration released "Financial Regulatory Reform: A New Foundation"5 in June 2009, and followed this with specific legislative language that provided a base text for congressional consideration.

Financial Crisis

Understanding the fabric of financial reform proposals requires some analysis both of financial disruptions that peaked in September 2008, as well as of more enduring concerns about risks in the financial system.6

The financial crisis focused policy attention on systemic risk, which had previously been a subject of interest to academics and central bankers, but was not seen as a significant threat to economic stability. The last major systemic risk episode was sparked by bank runs in the Great Depression, and the main elements of the current bank regulatory regime and federal safety net were put in place to prevent a similar recurrence. Between the end of the Great Depression and the early 2000s, the financial system weathered numerous shocks, failures, and crashes, with limited spillover into the real economy. Typically, the Federal Reserve (Fed) would announce that it stood ready to provide liquidity to the system, and that proved sufficient to stem panic. The idea that a financial shock could cause the entire system to spin out of control and collapse, and that the flow of credit might stop altogether, seemed to be a remote prospect. De facto policy was to rely on the Fed to deal with crises after the fact.

The events of 2007 and 2008 caused a sharp reassessment of the robustness and the self-stabilizing capacity of the financial system. As then-Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner noted in written testimony delivered to the House Financial Services Committee on September 23, 2009, "The job of a financial system … is to efficiently allocate savings and risk. Last fall, our financial system failed to do its job, and came precariously close to failing altogether."7

A number of discrete failures in individual markets and institutions led to global financial panic. Notably, many of these failures were not banks, seen historically as the primary source of systemic risk. U.S. financial firms suffered heavy losses in 2007 and 2008, primarily because of declines in the value of mortgage-related assets. During September 2008, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were placed in government conservatorship. Merrill Lynch was sold in distress to Bank of America in a deal supported by the Fed and Treasury. The Fed and Treasury failed to find a buyer for Lehman Brothers, which subsequently filed for bankruptcy, disrupting financial markets. A money market mutual fund (the Reserve Primary Fund) that held debt issued by Lehman Brothers announced losses, triggering a run on other money market funds, and Treasury responded with a guarantee for money market funds. The American International Group (AIG), an insurance conglomerate with a securities subsidiary that specialized in financial derivatives, including credit default swaps, was unable to post collateral related to its derivatives and securities lending activities. The Fed intervened with an $85 billion loan to prevent bankruptcy and to ensure full payment to AIG's counterparties. In response to the general panic, Congress approved the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP); the Fed introduced several lending facilities to provide liquidity to different parts of the financial system; and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) introduced a debt guarantee program for banks.8 The panic largely subsided through the latter part of 2008, although confidence in the financial system returned very slowly.

It was widely understood that the panic had its roots in the subprime mortgage market, in which years of double-digit housing price increases had fed a bubble mentality and caused lenders to relax underwriting standards. That the housing market would cool, as it began to do in 2006, was not a great surprise. What was generally unexpected was the way losses caused by rising foreclosures and bad loans rippled through the system. Major financial institutions had constructed highly leveraged speculative positions that magnified the subprime shock, so that a setback in a $1 trillion segment of the U.S. housing market generated many times that amount in financial losses.

Giant financial institutions were shown to be vulnerable to liquidity runs, and many failed or had to be rescued as short-term credit dried up. The value of complex financial instruments created through securitization became completely uncertain, and market participants lost confidence in each other's creditworthiness. Risks that were thought to be unrelated became highly correlated; a negative spiral that showed all financial risk taking to be interconnected and all declines to be self-reinforcing took hold. Doubts about counterparty exposure were magnified by opacity in derivatives markets.

Disruption to the financial system exacerbated recessionary forces already at work in the economy. Asset prices plunged and consumers suffered sharp losses in their retirement and college savings accounts, as well as in the value of their homes. The financial crisis accelerated declines in consumption and business investment, which in turn made banks' problems worse. Overall, the recession proved to be the deepest and longest since the Great Depression.

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-203)

The Dodd-Frank Act included measures to improve systemic stability, improve policy options for coping with failing financial firms, increase transparency throughout financial markets, and protect consumers and investors. The act included provisions that affected virtually every financial market and that amended existing or granted new authority and responsibility to nearly every federal financial regulatory agency.

Under each of the areas treated below, the financial crisis context and the corresponding provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act are included.

Systemic Risk

Financial Crisis Context9

Systemic risk refers to sources of instability for the financial system as a whole, often through "contagion" or "spillover" effects against which individual firms cannot protect themselves. Although regulators took systemic risk into account before the crisis, and systemic risk can never be entirely eliminated, analysts have pointed to a number of ostensible weaknesses in the precrisis regulatory regime's approach to systemic risk. First, there had been no regulator with overarching responsibility for mitigating systemic risk. Some analysts argue that systemic risk can fester in the gaps in the regulatory system where one regulator's jurisdiction ends and another's begins. Second, the crisis revealed that liquidity crises and runs were not just a problem for depository institutions. Third, the crisis revealed that nonbank, highly leveraged firms, such as Lehman Brothers and AIG, could be a source of systemic risk and "too big (or too interconnected) to fail." Finally, there were concerns that the breakdown of different payment, clearing, and settlement (PCS) systems that make up the "plumbing" of the financial system, which were not regulated consistently, could be another source of systemic risk.

Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Titles I and VIII)

Rather than creating a dedicated systemic risk regulator with broad powers to neutralize sources of systemic risk as they arise, Dodd-Frank instead created a Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC), composed of the Treasury Secretary as chair along with eight heads of federal regulatory agencies (including the newly created Consumer Financial Protection Bureau) and a presidential appointee with insurance experience as voting members. The act created an Office of Financial Research to support the council. See Table 2 below.

|

Voting Members (Heads of) |

Nonvoting Members |

|

Department of the Treasury |

Office of Financial Research (OFR) Director |

|

Federal Reserve Board (FRB, or the Fed) |

Federal Insurance Office Director |

|

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) |

A state insurance commissioner |

|

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) |

A state bank supervisor |

|

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) |

A state securities commissioner |

|

Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) |

|

|

Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) |

|

|

Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) |

|

|

National Credit Union Administration (NCUA) |

|

|

Insurance expert (appointed by the President) |

Source: Dodd-Frank §111(b).

The council is authorized to identify and advise its member regulators on sources of systemic risk and "regulatory gap" problems, but has limited rulemaking, examination, or enforcement powers of its own. The council is authorized to identify systemically important financial firms regardless of their legal charter, and the Fed will subject them and all bank holding companies with over $50 billion in assets to stricter prudential oversight and regulation, including counterparty exposure limits set at 25% of total capital, annual stress tests and capital planning requirements, resolution planning ("living wills"), early remediation requirements, and risk management standards. Many large firms were already regulated by the Fed for safety and soundness as bank holding companies; the act prevented most firms from changing their charter in order to escape Fed regulation (known as the "Hotel California" provision). In addition, the Dodd-Frank Act included a 10% liability concentration limit for financial firms and mechanisms by which the Fed would be empowered to curb the growth or reduce the size of large firms if they pose a risk to financial stability.10

Title VIII also provided for many PCS systems and activities deemed systemically important by the council to be regulated for safety and soundness by (depending on the type) the Fed, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), or the Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and to have access to the Fed's discount window in "unusual and exigent circumstances."

Federal Reserve

Financial Crisis Context11

During the recent financial turmoil, the Fed engaged in unprecedented levels of emergency lending to nonbank financial firms through its authority under Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act. At that time, this statute stated that "in unusual and exigent circumstances, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, by the affirmative vote of not less than five members, may authorize any Federal reserve bank ... to discount for any individual, partnership, or corporation, notes, drafts, and bills of exchange…."12

Such loans can be made only if secured to the Fed's satisfaction and if the targeted borrower is unable to obtain the needed credit through other banking institutions. In addition to the level of lending, the form of the lending was novel, particularly the creation of a series of liquidity facilities for nonbank financial firms and three limited liability corporations controlled by the Fed, to which the Fed lent a total of $72.6 billion to purchase illiquid assets from Bear Stearns and AIG. The Fed's actions under Section 13(3) generated debate in Congress about whether measures were needed to amend the institution's emergency lending powers.

Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title XI)

The Dodd-Frank Act included several provisions related to the Federal Reserve's Section 13(3) lending authority. In particular, the act stipulated that, although the Fed may authorize a Federal Reserve Bank to make collateralized loans as part of a broadly available credit facility, it may not authorize a Federal Reserve Bank to lend to only a single and specific individual, partnership, or corporation. When using this emergency authority, the Fed is required to seek approval from the Treasury Secretary.13 Title XI would also allow the FDIC to set up emergency liquidity programs to guarantee the debt of bank holding companies, similar to the 2008 Temporary Liquidity Guarantee Program.

In addition, the Dodd-Frank Act allowed the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to audit the Fed's lending facilities and open market operations for internal controls and risk management, and it called for a GAO audit of the Fed's actions during the crisis. The act required disclosure of Fed borrowers and borrowing terms, but with a time lag. The act prohibited firms regulated by the Fed from participating in the selection of directors of the regional Federal Reserve Banks.14 The act also created a new presidentially appointed Vice Chair of Supervision on the Board of Governors.

Resolution Regime for Failing Firms

Financial Crisis Context15

Most companies, including many financial companies, that fail in the United States are resolved through a judicial process in accordance with the U.S. Bankruptcy Code.16 The primary objective of a corporate17 bankruptcy is to provide the debtor with a "fresh start" by discharging the company's legal obligations to make further payments on existing debts.18 This generally is accomplished by either (1) liquidating the debtor company's assets so as to maximize returns to creditor classes based on a statutorily defined priority scheme, or (2) reorganizing the company's debts so that creditor classes receive more than they would have through liquidation, while also enabling the debtor to maintain operations as a going concern.19

However, federal law does not permit every financial company to file for protection under the Bankruptcy Code.20 For example, depository institutions (i.e., banks and thrifts) that hold FDIC-insured deposits cannot be debtors under the Bankruptcy Code.21 Instead, these insured depositories are subject to a special resolution regime, called a conservatorship or receivership (C/R), that typically is administered by the FDIC.22

Unlike the bankruptcy process, this C/R resolution regime is a largely nonjudicial, administrative process through which the FDIC assumes control over a troubled depository for the purpose of either preserving and conserving the institution's assets as conservator23 or liquidating the institution as receiver.24 The FDIC, as conservator or receiver, assumes broad and flexible powers, including "all the powers of the members or shareholders, the directors, and the officers of the institution."25 One of the primary objectives of the FDIC as conservator or receiver is to protect federally insured deposits of the failed institution by either paying them off or transferring them to another institution.26 This process generally requires significant disbursements from the FDIC's Deposit Insurance Fund and often results in the FDIC being the largest creditor of the failed institution.27 The FDIC is generally required by statute to choose the "least-cost resolution" strategy that will result in the lowest cost to the Deposit Insurance Fund.28 However, the FDIC may waive the least-cost resolution requirement under certain circumstances to "avoid serious adverse effects on economic conditions or financial stability."29

The financial turmoil at the end of the last decade that resulted from the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy and the federal government's provision of ad hoc emergency financial assistance to prevent the bankruptcies of AIG, Bear Stearns, and others focused congressional attention on options for resolving large, complex financial companies while maintaining the stability of the U.S. financial system. More specifically, policymakers questioned whether the Bankruptcy Code, as it was structured at the time of the financial crisis, could effectuate the resolution of large, complex financial companies without undermining financial stability.30 Some believed that establishing a special resolution regime for large, complex financial companies modeled after the nonjudicial C/R process for resolving failed depositories would reduce the likelihood that the federal government would need to provide taxpayer-backed financial assistance to reduce the potential systemic disruptions of one or more financial companies entering bankruptcy.31 Opponents argued that the establishment of a special resolution regime would enable policymakers to provide beneficial treatment to favored creditors and counterparties of failing firms.32 Rather than establishing a new administrative resolution regime, some policymakers argued that these systemic risk concerns could be effectively addressed through amendments to the Bankruptcy Code.33 Ultimately, Congress can be seen to have chosen a path somewhat in the middle of these policy proposals.

Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title II)

Title II of the Dodd-Frank Act establishes a new resolution regime for certain financial companies, called the "Orderly Liquidation Authority" (OLA). OLA is an administrative process modeled after the C/R regime for failed depository institutions. However, OLA is statutorily structured as a fallback alternative to the normally applicable Bankruptcy Code34 that is to be utilized only under extraordinary circumstances.35 Under normal circumstances, failed financial companies would be resolved under the Bankruptcy Code.36 OLA, on the other hand, may be utilized only if, at the time when an eligible financial company is in default or in danger of default, various federal regulators determine that the company's resolution under the Bankruptcy Code37 would pose dangers to the U.S. financial system.38

OLA is largely modeled after the C/R regime for failed depository institutions described above, but with some notable distinguishing characteristics. Like the C/R regime for depositories, OLA is a largely nonjudicial, administrative process that typically would be administered by the FDIC.39 Additionally, the FDIC's powers under OLA are similar to those assumed by the FDIC under the C/R regime for depositories.40

Unlike the C/R regime, which is limited to depository institutions and their subsidiaries, OLA is available to a broad array of financial companies, including bank holding companies, thrift holding companies, and insurance holding companies, as well as many of their subsidiaries.41 However, depository institutions continue to be resolved under the C/R regime, and insurance companies and certain securities broker-dealers are subject to distinct resolution requirements.42

While the chief objective of the C/R regime is to protect federally insured deposits and minimize the cost to the Deposit Insurance Fund, the primary objective of the OLA is "to provide the necessary authority to liquidate failing financial companies that pose a significant risk to the financial stability of the United States in a manner that mitigates such risk and minimizes moral hazard."43 To further this objective, OLA authorizes only receiverships, not conservatorships. The Dodd-Frank Act states that "[a]ll financial companies put into receivership under this title shall be liquidated and no taxpayer funds shall be used to prevent the liquidation of any financial company under this title."44

The funding mechanism for resolutions under the OLA also differs from the C/R regime for depositories. Whereas the Deposit Insurance Fund is prefunded based on assessments against insured depositories, the Orderly Liquidation Fund established for funding resolutions under the OLA is not prefunded.45 Instead, the FDIC is authorized to borrow from the Treasury as necessary to fund a specific OLA receivership, subject to explicit caps based on the value of the failed company's consolidated assets.46 If the failed companies' assets are insufficient to repay fully what was borrowed from the Treasury, then the FDIC is empowered to recover the shortfall from the financial industry.47

Securitization

Financial Crisis Context

Securitization is the process of turning mortgages, credit card loans, and other debt into securities that can be purchased by investors. Securitizers acquire and pool many loans from lenders and then issue new securities based on the flow of payments from the underlying loans. Banks can reduce the risk of their retained portfolios by securitizing the loans they hold, spreading risks to other types of investors more willing to bear them. If the risks are adequately managed and understood, this can enhance financial stability. Also, securitization is a source of funding for nonbank lenders, and thus can increase the total amount of credit available to businesses and consumers.

Securitization risks were not properly managed leading up to the crisis, contributing in part to the housing bubble and financial turmoil. Lenders collect origination fees, but if they sell their loans they are not exposed to loan losses if borrowers default. This creates an incentive to originate loans without appropriate underwriting. Prior to the crisis, these incentives likely led to deteriorating underwriting standards, and certain lenders may have been indifferent to whether loans would be repaid. Private securitization was especially prevalent in the subprime mortgage market, the nonconforming mortgage market, and in regions where loan defaults were particularly severe. Losses and illiquidity in the mortgage-backed securities (MBS) market led to wider problems in the crisis, including a lack of confidence in financial firms because of uncertainty about their exposure to potential MBS losses, through their holdings of MBS or off-balance sheet support to securitizers.

One approach to address incentives in securitization is to require loan securitizers to retain a portion of the long-term default risk. An advantage of this "skin in the game" requirement is that it may help preserve underwriting standards among lenders funded by securitization. Another advantage is that securitizers would share in the risks faced by the investors to whom they market their securities. A possible disadvantage is that if each step of the securitization chain must retain a portion of risk, then less risk may be shifted out to a broader sector of investors willing and able to bear it, raising the cost of credit. Concentrating risk in certain financial sectors could increase financial instability.

Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title IX)

The Dodd-Frank Act generally required securitizers to retain some of the risk if they issue asset-backed securities. The amount of risk required to be retained depends in part on the quality and type of the underlying assets. Regulators are instructed to write risk retention rules requiring less than 5% retained risk if the securitized assets meet prescribed underwriting standards. For assets that do not meet these standards, regulators were instructed to require not less than 5% retention of risk. Securitizers were prohibited from hedging the retained credit risk.

In the case of residential mortgages that are securitized, the Dodd-Frank Act allowed for a complete exemption from risk retention if all of the mortgages in the securitization meet the standards of a "Qualified Residential Mortgage." Subsequently, regulators decided to use the same definition for a "Qualified Residential Mortgage" and a "Qualified Mortgage."48 The act exempted certain government-guaranteed securities.

The act required securitizers to perform due diligence on the underlying assets of the securitization and to disclose the nature of the due diligence. In addition, investors in asset-backed securities are to receive more information about the underlying assets.

Bank Regulation

Financial Crisis Context49

During the crisis, banks and their parent companies, called bank-holding companies (BHC), came under significant stress, and over 500 banks would eventually fail, presenting an opportunity to reexamine bank regulation. Areas of concern that emerged included capital requirements; debit interchange fees; regulatory fragmentation; federal deposit insurance; and risky activities by banks.

Capital Requirements. Bank organizations fund themselves with liabilities and capital. Capital can absorb losses while the bank continues to meet its obligations on liabilities, and hence avoid failure. Safety and soundness regulations require banks to hold a certain amount of capital.

Following the crisis, some observers asserted that capital requirements should be more stringent, and requirements facing BHCs and certain nonbanks should be at least as stringent as those faced by depositories. Proponents argued that BHCs should be a "source of strength" to support distressed depository subsidiaries. They further claimed that differing requirements allowed banking organizations to take on more risk. Opponents argued that regulators should have discretion over what should be imposed across different company types to allow for differences in business models. They asserted this was especially true of nonbank institutions, with insurance companies in particular arguing those companies have substantially different risk profiles than banks.

Interchange Fees. When a debit card is used to make a purchase, the merchant making the sale pays a fee—known as the interchange fee—to the bank that issued the debit card (the issuer). The fee is compensation for services provided by the issuer, including facilitating authorization, clearance, and settlement and fraud prevention. Network providers set the rates for interchange fees, acting as an intermediary between issuers and merchants.

Merchants asserted that large network providers and issuing banks exercised market power to charge fees above market prices. Network providers and issuing banks argued that prices are appropriately set and reflected the costs—including fixed and card reward program costs overlooked by critics—of facilitating the transactions. Proponents of fee limits asserted the measures would eliminate anticompetitive pricing and benefit merchants and consumers. Opponents asserted that price restrictions would lead to inaccurate prices that created economic distortions and costs in other parts of the system.

Regulatory Consolidation. Commercial banks and similar institutions are subject to regulatory examination for safety and soundness. Prior to the crisis, these institutions—depending on their charter type—may have been examined by the Federal Reserve, OCC, the FDIC, the Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS), the National Credit Union Administration, or a state authority.

The system of multiple bank regulators was believed to have problems, some of which could be mitigated by consolidation. Consistent enforcement may be difficult across multiple regulators. To the extent that regulations are applied inconsistently, institutions may have an incentive to choose the regulator that they feel will be the least intrusive. While depositories of all types failed in the crisis, shortcomings in the OTS's supervision of large and complex institutions under its purview received particular criticism. An argument against consolidation is that regulatory consolidation could change the traditional U.S. dual banking system in ways that could put smaller banks at a disadvantage. Another argument for maintaining the current system is interaction between regulators monitoring different types of institutions may allow one regulator to alert others if it identifies emerging risks or regulatory weakness.

Federal Deposit Insurance. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) insures deposits, guaranteeing that (up to a certain account limit) depositors will not lose any deposits. FDIC funding comes from charging banks premiums—called assessments—which are used to maintain the Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF). The ratio of the value of the DIF to domestic deposits is called the reserve ratio.

At the onset of the crisis, the FDIC insured up to $100,000 per account, and was required to maintain a reserve ratio between 1.15% and 1.5%. During this crisis, the FDIC temporarily raised the maximum insured deposit amount to $250,000, because many depositors held accounts larger than $100,000. Also, the rapid increase in bank failures depleted the DIF. Observers argued that the FDIC needed greater latitude to collect assessments and maintain a higher reserve ratio.

Risky Activities. Crisis-related bank failures led some to call for new limits on risky activity. Paul Volcker, former Chair of the Federal Reserve (Fed) and former Chair of President Obama's Economic Recovery Advisory Board, argued that "adding further layers of risk to the inherent risks of essential commercial bank functions doesn't make sense, not when those risks arise from more speculative activities far better suited for other areas of the financial markets."50

While proprietary trading and hedge fund sponsorship pose risks, it is not clear whether they pose greater risks to bank solvency and financial stability than "traditional" banking activities, such as mortgage lending. They could be viewed as posing additional risks that might make banks more likely to fail, but alternatively those risks might better diversify a bank's risks, making it less likely to fail. Critics argue that banning proprietary trading or hedge fund sponsorship is "a solution in search of a problem—it seeks to address activities that had nothing to do with the financial crisis, and its practical effect has been to undermine financial stability rather than preserve it."51

Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title I, III, VI, and X)

Capital Requirements. Section 171 in Title I of Dodd-Frank—also known as the Collins Amendment—directed federal banking agencies to establish minimum capital requirements for insured depository institutions (except federal home loan banks), BHCs, and Federal Reserve supervised nonbank financial companies. The requirements on BHCs and certain nonbank companies generally cannot be less stringent than requirements on depositories. Small institutions received grandfathering, phase-ins, and exemption from parts or all of its requirements.52

Interchange Fees. Section 1075 in Title X of Dodd-Frank—also known as the Durbin Amendment—authorized the Federal Reserve Board to prescribe regulations to ensure that any interchange transaction fee received by a debit card issuer is reasonable and proportional to the cost incurred. Debit card issuers with less than $10 billion in assets were exempted by statute from the regulation. In addition, network providers and debit card issuers are prohibited from imposing restrictions on a merchant's choice of the network provider through which to route transactions.53

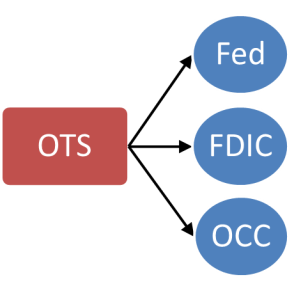

Regulatory Consolidation. Title III of Dodd-Frank did not effect a complete consolidation of banking agencies, but did eliminate the Office of Thrift Supervision as an independent agency and reassigns responsibility for regulating thrifts to the FDIC, the OCC, and to the Federal Reserve (see Figure 1).

|

|

Source: CRS. Notes: Blue = existing, red = eliminated. See text for details. |

Federal Deposit Insurance. Title III also made changes to federal deposit insurance. A new assessment formula is based on the total assets minus the average tangible equity of the depository, rather than on deposits. The minimum DIF reserve ratio was raised to 1.35% from 1.15%, and the 1.5% percent maximum was eliminated. The insured deposit limit was permanently raised to $250,000 from $100,000.54

Risky Activities. Section 619 of the Dodd-Frank Act—also known as the Volcker Rule—has two main parts. It prohibits banks from proprietary trading of "risky" assets and from "certain relationships" with risky investment funds; banks may not "acquire or retain any equity, partnership, or other ownership interest in or sponsor a hedge fund or a private equity fund."55 The statute carves out exemptions from the rule for trading activities that Congress viewed as legitimate for banks to participate in, such as risk-mitigating hedging and market-making related to broker-dealer activities. It also exempts certain securities, including those issued by the federal government, government agencies, states, and municipalities, from the ban on proprietary trading.56

Consumer Financial Protection57

Financial Crisis Context

Before Title X of the Dodd-Frank Act (entitled the Consumer Financial Protection Act) went into effect,58 federal consumer financial protection regulatory authority was split between five banking agencies—the OCC, Fed, FDIC, NCUA, and OTS59—as well as the FTC and HUD. These seven agencies shared (1) the authority to write rules to implement most federal consumer financial protection laws; (2) the power to enforce those laws; and (3) supervisory authority over the individuals and companies offering and selling consumer financial products and services.60 The jurisdictions of these agencies varied based on the type of institution involved and, in some cases, based on the type of financial activities in which institutions engaged.61

The regulatory authority of the banking agencies varied by depository charter. The OCC regulated depository institutions with a national bank charter.62 The Fed regulated the domestic operations of foreign banks and state-chartered banks that were members of the Federal Reserve System (FRS).63 The FDIC regulated state-chartered banks and other state-chartered depository institutions that were not members of the FRS.64 The NCUA regulated federally insured credit unions,65 and the OTS regulated institutions with a federal thrift charter.66

The banking agencies were charged with a two-pronged mandate to regulate depository institutions within their jurisdiction for safety and soundness, as well as consumer compliance.67 The focus of safety and soundness regulation is ensuring that institutions are managed in a safe and sound manner so as to maintain profitability and avoid failure.68 The focus of consumer compliance regulation is ensuring that institutions abide by applicable consumer protection and fair lending laws.69 To reach these ends, the banking agencies held broad authority to subject depository institutions to upfront supervisory standards, including the authority to conduct regular, if not continuous, on-site examinations of depository institutions.70 They also had flexible enforcement powers to redress consumer harm, as well as to rectify proactively compliance issues found in the course of examinations and the exercise of their other supervisory powers, potentially before consumers suffered harm.71

The FTC was the primary federal regulator for nondepository financial companies, such as payday lenders and mortgage brokers.72 Unlike the federal banking agencies, the FTC had little upfront supervisory or enforcement authority.73 For instance, the FTC did not have the statutory authority to examine nondepository financial companies regularly or impose reporting requirements on them as a way proactively to ensure they were complying with consumer protection laws.74 Instead, the FTC's powers generally were limited to enforcing federal consumer laws.75 However, because the FTC lacked supervisory powers, it generally initiated enforcement actions in response to consumer complaints, private litigation, or similar "triggering events [that] postdate injury to the consumer."76

Additionally, both depository institutions and nondepository financial companies were subject to federal consumer financial protection laws.77 Together, these federal laws establish consumer protections for a broad and diverse set of activities and services, including consumer credit transactions,78 third-party debt collection,79 and credit reporting.80 Before the Dodd-Frank Act went into effect, the rulemaking authority to implement federal consumer financial protection laws was largely held by the Fed.81 However, the authority to enforce federal consumer financial protection laws and regulations was spread among all of the banking agencies, the FTC, and HUD.82

Some scholars and consumer advocates argued that the complex, fragmented federal consumer financial protection regulatory system in place before the Dodd-Frank Act was enacted failed to protect consumers adequately and created market inefficiencies to the detriment of both financial companies and consumers.83 Some argued that these problems could be corrected if federal consumer financial regulatory powers were strengthened and consolidated in a single regulator with a consumer-centric mission and supervisory, rulemaking, and enforcement powers akin to those held by the banking agencies.84

Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title X)

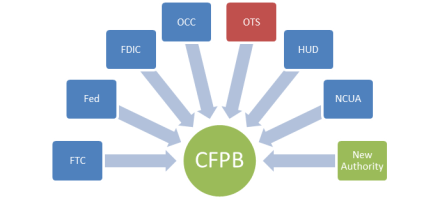

The Dodd-Frank Act establishes the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (CFPB, or Bureau) as an independent agency within the Federal Reserve System.85 The CFPB is headed by a single Director and funded primarily by a transfer of nonappropriated funds from the Federal Reserve System's combined earnings in an amount "determined by the Director to be reasonably necessary to carry out the authorities of the Bureau," subject to specified caps.86 The CFPB has rulemaking, enforcement, and supervisory powers over many consumer financial products and services, as well as the entities that sell them.87 The Dodd-Frank Act explicitly exempts certain industries from CFPB regulation, however.88 The Dodd-Frank Act significantly enhances federal consumer protection regulatory authority over nondepository financial companies, for instance, by providing the CFPB with supervisory and examination authority over certain nondepository financial companies akin to those powers long held by the banking agencies over depository institutions.89 Although the Dodd-Frank Act consolidates in the CFPB much of the federal consumer financial protection authority, as shown in Figure 2, at least six other agencies—the OCC, Fed, FDIC, NCUA, HUD, and FTC—retain some powers in this field.90

|

|

Source: CRS. Notes: Blue = existing, green = new, red = eliminated. Existing regulators retained certain consumer regulatory responsibilities. See text for details. |

The Dodd-Frank Act transferred from the banking agencies to the bureau primary consumer compliance authority over banks, thrifts, and credit unions with more than $10 billion in assets.91 However, the banking agencies continue to hold safety and soundness authority over these "larger depositories,"92 as well as both consumer compliance and safety and soundness authority over "smaller depositories" (i.e., bank, thrifts, and credit unions with $10 billion or less in assets).93

The law also transferred to the bureau the primary rulemaking authority over 19 "enumerated consumer laws,"94 which, with one exception,95 were enacted prior to the Dodd-Frank Act.96 Additionally, the CFPB is authorized to prohibit unfair, deceptive, and abusive acts or practices associated with consumer financial products and services that fall under the bureau's general regulatory jurisdiction.97 The bureau also is authorized to enforce consumer financial protections laws either through the courts98 or administrative adjudications.99 The CFPB is authorized by statute to redress violations of consumer financial protection laws through the assessment of civil monetary penalties, restitution orders, and various other forms of legal and equitable relief.100

Mortgage Standards

Financial Crisis Context

Beginning around the middle of 2006, residential mortgage delinquency and foreclosure rates rose sharply in many regions of the United States. In addition to the negative effects on some homeowners, the increase in nonperforming mortgages contributed to the financial crisis by straining the balance sheets of financial firms that held those mortgages. Although all kinds of mortgages experienced increases in delinquency and foreclosure, many poorly performing mortgages exhibited increasingly complex features, such as adjustable interest rates, or nontraditional mortgage features, such as negative amortization. While such nontraditional or complex mortgage features may be appropriate for some borrowers in some circumstances, many were made available more widely. In addition, some observers view certain mortgage features, such as high prepayment penalties, as predatory. Although not all troubled mortgages exhibited these or similar features, and not all loans that exhibited such features became troubled, some observers point to the widespread use of such mortgage terms as having exacerbated the housing "bubble" and its subsequent collapse.

The role that nonperforming mortgages played in the financial crisis led some to suggest actions to protect consumers from risky mortgage products and to protect the U.S. financial system from experiencing major losses due to troubled mortgages in the future. One way to minimize mortgage defaults and foreclosures is to limit or prohibit certain mortgage features that are viewed as especially risky. Another would be to require mortgage lenders to offer consumers basic mortgage products with traditional terms alongside any loan with nontraditional features. Although either of these approaches may reduce the chances of widespread mortgage failures, and might help preserve financial stability, both could also limit consumer choice or prevent borrowers from taking out loans with nontraditional features that may be advantageous given their specific circumstances. Some also argue that such approaches could limit financial innovation in mortgage products or reduce competition among lenders.

Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title XIV)

The Dodd-Frank Act amended the Truth in Lending Act (TILA)101 to set minimum standards for certain residential mortgages. Under the Ability-to-Repay requirements, lenders are required to determine that mortgage borrowers have a reasonable ability to repay the mortgages that they receive, based on the borrowers' verified income and other factors. Certain "Qualified Mortgages" with traditional mortgage terms are presumed to meet these requirements. The CFPB was also directed to issue regulations prohibiting mortgage originators from "steering" consumers to mortgages that (1) those consumers do not have a reasonable ability to repay, (2) exhibit certain features that are determined to be predatory, or (3) meet certain other conditions. It was also directed to issue regulations prohibiting any practices related to residential mortgage lending that it deems to be "abusive, unfair, deceptive, [or] predatory." The act restricted the use of prepayment penalties. Mortgage originators are prohibited from receiving compensation that varies in any way based on the applicable mortgages terms or conditions, other than the principal amount. The act also required increased disclosures to consumers on a range of topics, including disclosures related to how certain features of a mortgage may affect the consumer.

New requirements related to "high-cost mortgages" are included in the act, such as limitations on the terms of such mortgages and a requirement that lenders verify that borrowers have received prepurchase counseling before obtaining such a mortgage.

Derivatives102

Financial Crisis Context

Derivatives are financial contracts whose value is linked to some underlying asset price or variable. They fall into three types of instruments—futures, options, and swaps. Some derivatives are traded on organized exchanges with central clearinghouses that guarantee payment on all contracts, while swaps are traded in an over-the-counter (OTC) market, where credit risk is borne by the individual counterparties.

The Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000 (CFMA)103 largely exempted swaps and other derivatives in the OTC market from regulation. The collapse of AIG in 2008 illustrated the risks posed by large OTC derivatives positions not backed by collateral or margin (as a central clearinghouse would require). If AIG had been required to post margin on its credit default swap contracts, it would have been unlikely to build such a large position, which could have reduced the threat to systemic stability and the resulting large taxpayer bailout. Further, opacity in the OTC market made it difficult for policymakers and market participants to gauge firms' risk exposures, arguably exacerbating the panic.

Such disruptions in markets for financial derivatives during the financial crisis led to calls for changes in derivatives regulation, particularly whether the swap (OTC) markets should adopt features of the regulated markets.

Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Titles VII and XVI)

Under the Dodd-Frank Act, the Commodities Futures Trading Commission regulates "swaps," which include contracts based on interest rates, currencies, physical commodities, and some credit default swaps, whereas the SEC has authority over a much smaller slice of the market, including "security-based swaps," which are mostly other credit default swaps and equity swaps.104

The Dodd-Frank Act mandated centralized clearing and exchange-trading of many OTC derivatives, but provided exemptions for certain market participants. In general, swaps that must be cleared must also be traded on an exchange or exchange-like facility that provides price transparency. The regulators were given considerable discretion to define the forms of trading that will meet this requirement.

The Dodd-Frank Act included an exemption from the clearing requirement, if desired, if at least one party to the trade is an "end user,"105 defined as parties that are not financial entities106 and are using the swaps to hedge or mitigate commercial risk. An exempted party must inform the CFTC or SEC (depending on the contract) on how they generally meet their financial obligations when entering into uncleared swaps.

The act requires regulators to impose registration and capital requirements on swap dealers and major swaps participants. It requires regulators to impose margin requirements on certain swaps that remain uncleared by any clearinghouse. It also requires reporting of all swaps, including those not subject to or exempt from the clearing requirement, to swap data repositories. Both agencies were given the power to promulgate rules to prevent the evasion of the clearing requirements created by the act.

Section 716, which was a widely debated section of the act, prohibited federal assistance to any swaps entity and became known as the "swaps pushout rule." It included an exemption, however, that appeared to address concerns that under previous language large commercial banks would have been unable to hedge their risk without becoming ineligible for federal assistance, including access to the Federal Reserve's discount window or any other Fed credit facility and FDIC insurance. Furthermore, depository institutions were permitted to establish an affiliate that was a swap entity as long as it was supervised by the Fed. P.L. 113-235, an omnibus appropriations bill, included language narrowing Section 716 of the Dodd-Frank Act.107

Credit Rating Agencies

Financial Crisis Context108

Credit rating agencies provide investors with an evaluation of the creditworthiness of bonds issued by a wide spectrum of entities, including corporations, sovereign nations, and municipalities. The grading of the creditworthiness is typically displayed in a letter hierarchical format: for example, AAA being the safest, with lower grades representing greater risk. Credit rating agencies (CRAs) are typically paid by the issuers of the securities being rated by the agencies, which could be seen as a conflict of interest. In exchange for adhering to various policies and reporting requirements, the SEC can confer on interested CRAs the designation of a Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating Organization (NRSRO). Historically, the designation was especially significant because a host of state and federal laws and regulations referenced or required NRSRO-based credit ratings.109

In the run-up to the financial crisis, the provision of investment-grade ratings110 by the three dominant CRAs—Moody's, Standard & Poor's, and Fitch—was a critical part of the process of structuring the residential mortgage-backed securities and collateralized debt obligations that held subprime housing mortgages. Many observers believed that the three leading CRAs fundamentally failed in their rating of these securities, exacerbating the market collapse. During the housing boom preceding the financial crisis, the CRAs often gave top-tier AAA ratings to many structured securities, only to downgrade many of them later to levels often below investment grade status. One argument for the dominant rating agencies' failings was their reliance on a business model in which issuers paid the agencies for their rating services. This issuer-pays model was criticized for potentially creating bias toward providing overly favorable ratings.

Criticism of the CRAs, however, was not universal. A common defense of their failings was that their rating missteps could be traced in part to their view that the rising housing prices would be sustained, a perspective also said to be held by a number of respected financial market observers at the time.111

Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title IX)

The Dodd-Frank Act contains provisions that enhanced SEC regulation of credit rating agencies. It established the SEC Office of Credit Ratings; imposed new reporting, disclosure, and examination requirements on NRSROs; established new standards of legal liability; and required the removal of references to NRSRO ratings from federal statutes and regulations.

In an attempt to mitigate some of the potential bias in the issuer-pays model, the Dodd-Frank Act directed the SEC to study the feasibility of establishing a public utility/self-regulatory body that would randomly assign NRSROs to provide credit ratings for structured finance products. After completion of the study, unless the SEC "determines an alternative system would better serve the public interest and protection of investors," the agency was required to implement the proposed public utility/self-regulatory organization system. Released in 2012, the study recommended that the SEC convene a roundtable of stakeholders to discuss the merits of several alternative business models for rating structured products.112 The public utility system has not been adopted to date.

Investor Protection

Financial Crisis Context

Before his arrest in 2008, Bernard Madoff was responsible for the theft of billions of dollars of his client's funds using a massive Ponzi scheme conducted through his securities firm.113 The firm was a registered broker-dealer subject to oversight by Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA, the self-regulatory organization for broker-dealers overseen by the SEC) and was also a registered investment adviser subject to SEC oversight. One consequence of the Madoff affair was heightened interest and concern over the adequacy of investor protection in the regulatory realm.

The SEC is funded through the congressional appropriation process. It has been argued that the SEC needs similar budgetary independence to other financial regulators to help close the resource gap between the agency and its regulated entities.114 Through the years, however, a key criticism of proposals for SEC self-funding was that it would undermine agency accountability and oversight provided by the congressional appropriation process.115

Principally regulated by FINRA, broker-dealers are required to make investment recommendations that are "suitable" to their customers, meaning that they must do what is suitable for an investor, based on that investor's particular circumstances. SEC-registered investment advisers have a "fiduciary duty" to their customers with respect to investment recommendations under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940.116 It is an obligation to place their client's best interests above their own—a more demanding duty to their clients than the suitability standard. The services provided by broker-dealers and investment advisers, however, often overlap—both can provide investment advice—and there are some concerns that customers may falsely assume that the person advising them has a fiduciary duty to them.

Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title IX)

The Dodd-Frank Act established an Investor Advisory Committee within the SEC whose purpose is to advise and consult with the SEC on regulatory priorities from an investor protection perspective. The act also created an Office of the Investor Advocate within the SEC. It also enhanced rewards and protection to whistleblowers of securities fraud.

The Dodd-Frank Act also required the SEC to produce a study on the effectiveness of the standards of care required of broker-dealers and investment advisers. Released in 2011, the study recommended that the SEC establish a uniform fiduciary standard for broker-dealers and investment advisers when they provided personalized investment advice on securities to retail customers, a standard that should not be any less stringent than the fiduciary standard for investment advisers under the Investment Advisors Act of 1940. To date, the SEC has not acted on this recommendation.117

The Dodd-Frank Act required financial advisors in municipal securities markets to register with the SEC and permits the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board to promulgate rules governing their behavior. The Dodd-Frank Act also allows the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board to examine auditors of broker-dealers and exempts small firms from external audit requirements found in Section 404(b) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act.118

The Dodd-Frank Act as enacted did not provide for a self-funded SEC. It did, however, give the agency some budgetary autonomy.119 One such measure was the establishment of a SEC Reserve Fund to be used as the agency "determines is necessary to carry out the functions of the Commission." The SEC was authorized to deposit up to $50 million a year into the Reserve Fund from registration fees collected from SEC registrants, up to a fund balance limit of $100 million. To date, Congress has rescinded $25 million from the fund in two years.120 The SEC has used the Reserve Fund to help modernize its information technology.

Hedge Funds

Financial Crisis Context121

The term "hedge fund" is not defined by federal law, but it is generally used to describe a privately organized, pooled investment vehicle not widely available to the public.122 Some hedge funds can also be distinguished from other investment funds by their pronounced use of leverage, along with hedge funds' use of active trading strategies in which investment positions change frequently.123 Some potential risks hedge fund investing might pose to the markets as a whole were revealed in 1998 when the hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) teetered on the brink of collapse.124 Concerns over the systemic implications of LTCM's collapse resulted in the New York Fed engineering a multibillion-dollar private rescue of the fund.125 Hedge fund failures apparently did not play a prominent role in precipitating or spreading the 2008 financial crisis.126 Nonetheless, the collapse of LTCM and the systemic issues that it revealed led the 111th Congress to consider the laws that applied or, more accurately, did not apply to hedge funds and their managers.127

Prior to the enactment of the Dodd-Frank Act, most hedge funds and their managers were not required to register with the SEC128 due to a combination of interlocking and commonly used exemptions in the Investment Company Act of 1940 (ICA)129 and the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 (IAA).130

Generally, the ICA requires investment companies, broadly defined to include companies that invest in securities and offer their own securities to the public,131 to register with the SEC and comply with the provisions of the act.132 Under Section 3(c)(1) of the act, issuers with fewer than 100 beneficial owners that do not make public offerings of their securities are not deemed to be investment companies.133 Section 3(c)(7) also generally exempts from the act's definition of "investment companies" those companies that sell shares only to "qualified purchasers"134 and do not make public offerings of their securities.135 Hedge funds, and other private investment vehicles, typically avail themselves of one of these two exemptions, which means that the ICA, for the most part, does not apply to the funds themselves.136

Subject to certain exemptions, the IAA defines an "investment adviser" as a person "who, for compensation, engages in the business of advising others, either directly or through publications or writings, as to the value of securities or as to the advisability of investing in, purchasing, or selling securities.... "137 Investment advisers generally are required to register with the SEC and otherwise comply with the act.138

However, under the "private adviser" exemption in the IAA that existed prior to the enactment of the Dodd-Frank Act, advisers were not required to register with the SEC if, during the preceding 12 months, they (1) did not hold themselves out to the public as investment advisers, (2) had fewer than 15 clients, and (3) did not act as advisers to an investment company registered under the ICA.139 Clients, under this exemption, referred to entire investment funds if they were not registered investment companies and not to each individual investor in those funds.140 Therefore, before the enactment of the Dodd-Frank Act, an adviser could manage up to 14 hedge funds without being required to register as an investment adviser.141

Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title IV)

The Dodd-Frank Act preserved the ICA exemptions from the definition of an "investment company" most often used by hedge funds and other private pooled investment vehicles, and the act also codified a statutory definition for "private fund[s]" based upon whether the funds availed themselves of those exemptions.142 More importantly, the Dodd-Frank Act eliminated the "private adviser" exemption in the IAA.143 This modified a regulatory framework that had prevented the government from having access to information about the size and trading strategies of hedge funds, as well as such funds' positions in the market.144 Access to information of that sort, it was argued by proponents of the act, would be critical to any future government response to a financial crisis.145

The repeal of the exemption generally required advisers to private funds, including hedge funds, with more than $150 million in assets under management to register with the SEC.146 Advisers are also required to provide such information about their investment portfolios and strategies to the extent the SEC, in consultation with the FSOC, deems necessary to monitor systemic risk.147 Advisers to venture capital funds148 and private funds with assets under management of $150 million or less149 are exempt from the registration requirement, but must submit reports and information to the SEC as the SEC deems necessary.150 The Dodd-Frank Act also raised the asset threshold for SEC registration of investment advisers to funds that are not investment companies from $25 million to $100 million.151

Executive Compensation and Corporate Governance

Financial Crisis Context

Although some observers have questioned the validity of such links,152 the financial crisis raised concerns that incentive compensation arrangements (compensation based on an employee's performance) at various financial firms created incentives for executives at those firms to take excessive risks.153 The Dodd-Frank Act addressed this issue and also contained executive compensation provisions that were not directly linked to the financial crisis and which applied to all public companies.

Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title IX)

Dodd-Frank required the SEC to issue rules that would affect all companies listed on a stock exchange. These rules would require a company found to be in material noncompliance with financial disclosure requirements in federal securities laws to claw back incentive-based executive officer compensation awarded during the three years before it is required to restate its financials.

Dodd-Frank also directed federal financial regulators to adopt new rules to jointly prescribe regulations or guidelines aimed at prohibiting incentive compensation arrangements that might encourage inappropriate risks at financial institutions with a $1 billion or more in assets.

The act also required public companies to disclose the ratio of the chief executive officer's (CEO's) compensation to that of their median employee (excluding CEO pay). In addition, at least once every three years, public company shareholders are entitled to cast a nonbinding vote on whether they approve of executive compensation, popularly known as "say on pay."

The Dodd-Frank Act also granted the SEC explicit authority to issue rules providing for shareholder proxy access, the ability of shareholders to nominate outsider directors to a company's board.154

Insurance155

Financial Crisis Context

Under the McCarran-Ferguson Act of 1945,156 insurance regulation is generally left to the individual states. For several years prior to the financial crisis, some Members of Congress introduced legislation to federalize insurance regulation along the lines of the dual regulation of the banking sector.157

The financial crisis, particularly the problems with insurance giant AIG and the smaller monoline bond insurers, changed the tenor of the debate around insurance regulation with increased emphasis on the systemic importance of some insurance companies. Although it was argued that insurer involvement in the financial crisis demonstrated the need for full-scale federal regulation of insurance, the financial regulatory reform debate generally did not include such a federal system. Instead, such proposals typically included the creation of a somewhat narrower federal office focusing on gathering information on insurance and setting policy on international insurance issues. Proposals relating to consumer protection, investor protection, bank and thrift holding company oversight, and systemic risk also had the potential to affect insurance, absent exemptions.

Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act (Title V)

The Dodd-Frank Act created a new Federal Insurance Office within the Treasury Department. In addition to gathering information and advising on insurance issues, this office has limited preemptive power over state insurance laws and regulations. This preemption is limited to cases in which state regulation results in less favorable treatment of non-U.S. insurers and to those covered by an existing international agreement.158 Insurers were exempted from oversight by the act's new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Under the act, systemically important insurers are subject to identification by the Financial Stability Oversight Council and regulation by the Federal Reserve. Insurers also may be subject to resolution by the special authority created by the act at the holding company level, although resolution of state-chartered insurance companies continues to occur under the state insurer insolvency regimes. Consolidation of bank and thrift holding company oversight resulted in several insurers with depository subsidiaries being overseen by the Federal Reserve after abolishment of the Office of Thrift Supervision. The Collins Amendment (addressed above in "Bank Regulation") could have imposed additional capital requirements on insurers overseen by the Federal Reserve; however, this provision was later amended by P.L. 113-279 to allow flexibility in its implementation. In addition, the Dodd-Frank Act streamlined the state regulation of surplus lines insurance and reinsurance.159

Miscellaneous Provisions in the Dodd-Frank Act

The Dodd-Frank Act contains several miscellaneous provisions in various titles of the legislation, including the following:

- Title XII: Improving Access to Mainstream Financial Institutions. This title included provisions to expand access to the banking system for families with low and moderate incomes by (1) authorizing a program to help such individuals open low-cost checking or savings accounts at banks or credit unions; and (2) creating a pool of capital to enable community development financial institutions to provide small, local, retail loan programs.

- Title XIII: The TARP Pay it Back Act. This title reduced the amount authorized to be outstanding under the TARP to $475 billion; it was originally $700 billion. It also prohibited the Treasury from using repaid TARP funds to make new TARP investments.160