Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 115-174) and Selected Policy Issues

Some observers assert the financial crisis of 2007-2009 revealed that excessive risk had built up in the financial system, and that weaknesses in regulation contributed to that buildup and the resultant instability. In response, Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 111-203; the Dodd-Frank Act), and regulators strengthened rules under existing authority. Following this broad overhaul of financial regulation, some observers argue certain changes are an overcorrection, resulting in unduly burdensome regulation.

The Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (S. 2155, P.L. 115-174) was signed into law by President Donald Trump on May 24, 2018. P.L. 115-174 modifies Dodd-Frank provisions, such as the Volcker Rule (a ban on proprietary trading and certain relationships with investment funds), the qualified mortgage criteria under the Ability-to-Repay Rule, and enhanced regulation for large banks; provides smaller banks with an “off ramp” from Basel III capital requirements—standards agreed to by national bank regulators as part of an international bank regulatory framework; and makes other changes to the regulatory system.

Most changes made by P.L. 115-174 can be grouped into one of five issue areas: (1) mortgage lending, (2) regulatory relief for “community” banks, (3) consumer protection, (4) regulatory relief for large banks, and (5) regulatory relief for capital formation.

Title I of P.L. 115-174 relaxes or provides exemptions to certain mortgage lending rules. For example, it creates a new compliance option for mortgages originated and held by banks and credit unions with less than $10 billion in assets to be considered qualified mortgages for the purposes of the Ability-to-Repay Rule. In addition, P.L. 115-174 exempts certain insured depositories and credit unions that originate few mortgages from certain Home Mortgage Disclosure Act reporting requirements.

A number of Title II provisions provide regulatory relief to community banks. For example, banks with under $10 billion in assets are exempt from the Volcker Rule, and certain banks that meet a new Community Bank Leverage Ratio are exempt from other risk-based capital ratio and leverage ratio requirements.

Title III enhances consumer protections in targeted areas. For example, it subjects credit reporting agencies (CRAs) to additional requirements, including requirements to generally provide fraud alerts for consumer files for at least a year and to allow consumers to place security freezes on their credit reports. In addition, it requires CRAs to exclude certain medical debt from veterans’ credit reports.

Title IV alters the criteria used to determine which banks are subject to enhanced prudential regulation from the original $50 billion asset threshold original set by Dodd-Frank. Banks designated as global systemically important banks and banks with more than $250 billion in assets are still automatically subjected to enhanced regulation. However, under P.L. 115-174 banks with between $100 billion and $250 billion in assets are automatically subject only to supervisory stress tests, while the Federal Reserve (Fed) has discretion to apply other individual enhanced prudential provisions to these banks. Banks with assets between $50 billion and $100 billion will no longer be subject to enhanced regulation, except for the risk committee requirement. In addition, P.L. 115-174 relaxes leverage requirements for large custody banks, and allows certain municipal bonds to be counted toward large banks’ liquidity requirements.

Title V provides regulatory relief to certain securities regulations to encourage capital formation. For example, it exempts more securities exchanges from state securities regulation and subjects certain investment pools to fewer registration and disclosure requirements.

Title VI provides enhanced consumer protection for borrowers of student loans. For example, it requires CRA to exclude certain defaulted private student loan debt from credit reports.

Proponents of P.L. 115-174 assert it provides necessary and targeted regulatory relief, fosters economic growth, and provides increased consumer protections. Opponents of the legislation argue it needlessly pares back important Dodd-Frank protections to the benefit of large and profitable banks.

Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 115-174) and Selected Policy Issues

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Amending Mortgage Rules

- Background

- Provisions and Selected Analysis

- Section 101—Qualified Mortgage Status for Loans Held by Small Banks

- Section 102—Charitable Tax Deduction for Appraisals

- Section 103—Exemption from Appraisals in Rural Areas

- Section 104—Home Mortgage Disclosure Act Adjustment

- Section 105—Credit Union Loans for Nonprimary Residences

- Section 106—Mortgage Loan Originator Licensing and Registration

- Section 107—Manufactured Homes Retailers

- Section 108—Escrow Requirements Relating to Certain Consumer Credit Transactions

- Section 109—Waiting Period Requirement for Lower-Rate Mortgage

- Regulatory Relief for Community Banks

- Background

- Provisions and Selected Analysis

- Section 201—Community Bank Leverage Ratio

- Section 202—Allowing More Banks to Accept Reciprocal Deposits

- Section 203 and 204—Changes to the Volcker Rule

- Section 205—Financial Reporting Requirements for Small Banks

- Section 206—Allowing Thrifts to Opt-In to National Bank Regulatory Regime

- Section 207—Small Bank Holding Company Policy Statement Threshold

- Section 210—Frequency of Examination for Small Banks

- Section 213—Identification When Opening an Account Online

- Section 214—Classifying High Volatility Commercial Real Estate Loans

- Consumer Protections

- Background

- Credit Reporting

- Veterans and Active Duty Servicemembers

- Student Loans

- Provisions and Selected Analysis

- Section 215—Reducing Identity Theft

- Section 301—Fraud Alerts and Credit Report Security Freezes

- Section 302—Veteran Medical Debt in Credit Reports

- Section 303—Whistleblowers on Senior Exploitation

- Section 304—Protecting Tenants at Foreclosure

- Section 307—Real Property Retrofit Loans

- Section 309—Protecting Veterans from Harmful Mortgage Refinancing

- Section 310—Consider Use of Alternative Credit Scores for Mortgage Underwriting

- Section 313—Foreclosure Relief Extension for Servicemembers

- Section 601—Student Loan Protections in the Event of Death or Bankruptcy

- Section 602—Certain Student Loan Debt in Credit Reports

- Regulatory Relief for Large Banks

- Background

- Provisions and Selected Analysis

- Section 401—Enhanced Prudential Regulation and the $50 Billion Threshold

- Section 402—Custody Banks and the Supplementary Leverage Ratio

- Section 403—Municipal Bonds and Liquidity Coverage Ratio

- Capital Formation

- Background

- Provisions and Selected Analysis

- Section 501—National Security Exchange Parity

- Section 504—Registration Requirements for Small Venture Capital Funds

- Section 506—U.S. Territories Investor Protection

- Section 507—Disclosure Requirements for Companies Paying Personnel in Stock

- Section 508―Expanding Regulation A+ Access to Reporting Companies

- Section 509—Streamlined Closed-End Fund Registration

- Miscellaneous Proposals in P.L. 115-174

Tables

Summary

Some observers assert the financial crisis of 2007-2009 revealed that excessive risk had built up in the financial system, and that weaknesses in regulation contributed to that buildup and the resultant instability. In response, Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 111-203; the Dodd-Frank Act), and regulators strengthened rules under existing authority. Following this broad overhaul of financial regulation, some observers argue certain changes are an overcorrection, resulting in unduly burdensome regulation.

The Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (S. 2155, P.L. 115-174) was signed into law by President Donald Trump on May 24, 2018. P.L. 115-174 modifies Dodd-Frank provisions, such as the Volcker Rule (a ban on proprietary trading and certain relationships with investment funds), the qualified mortgage criteria under the Ability-to-Repay Rule, and enhanced regulation for large banks; provides smaller banks with an "off ramp" from Basel III capital requirements—standards agreed to by national bank regulators as part of an international bank regulatory framework; and makes other changes to the regulatory system.

Most changes made by P.L. 115-174 can be grouped into one of five issue areas: (1) mortgage lending, (2) regulatory relief for "community" banks, (3) consumer protection, (4) regulatory relief for large banks, and (5) regulatory relief for capital formation.

Title I of P.L. 115-174 relaxes or provides exemptions to certain mortgage lending rules. For example, it creates a new compliance option for mortgages originated and held by banks and credit unions with less than $10 billion in assets to be considered qualified mortgages for the purposes of the Ability-to-Repay Rule. In addition, P.L. 115-174 exempts certain insured depositories and credit unions that originate few mortgages from certain Home Mortgage Disclosure Act reporting requirements.

A number of Title II provisions provide regulatory relief to community banks. For example, banks with under $10 billion in assets are exempt from the Volcker Rule, and certain banks that meet a new Community Bank Leverage Ratio are exempt from other risk-based capital ratio and leverage ratio requirements.

Title III enhances consumer protections in targeted areas. For example, it subjects credit reporting agencies (CRAs) to additional requirements, including requirements to generally provide fraud alerts for consumer files for at least a year and to allow consumers to place security freezes on their credit reports. In addition, it requires CRAs to exclude certain medical debt from veterans' credit reports.

Title IV alters the criteria used to determine which banks are subject to enhanced prudential regulation from the original $50 billion asset threshold original set by Dodd-Frank. Banks designated as global systemically important banks and banks with more than $250 billion in assets are still automatically subjected to enhanced regulation. However, under P.L. 115-174 banks with between $100 billion and $250 billion in assets are automatically subject only to supervisory stress tests, while the Federal Reserve (Fed) has discretion to apply other individual enhanced prudential provisions to these banks. Banks with assets between $50 billion and $100 billion will no longer be subject to enhanced regulation, except for the risk committee requirement. In addition, P.L. 115-174 relaxes leverage requirements for large custody banks, and allows certain municipal bonds to be counted toward large banks' liquidity requirements.

Title V provides regulatory relief to certain securities regulations to encourage capital formation. For example, it exempts more securities exchanges from state securities regulation and subjects certain investment pools to fewer registration and disclosure requirements.

Title VI provides enhanced consumer protection for borrowers of student loans. For example, it requires CRA to exclude certain defaulted private student loan debt from credit reports.

Proponents of P.L. 115-174 assert it provides necessary and targeted regulatory relief, fosters economic growth, and provides increased consumer protections. Opponents of the legislation argue it needlessly pares back important Dodd-Frank protections to the benefit of large and profitable banks.

Introduction

The Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (S. 2155) was reported out by the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs on December 18, 2017. It was then passed by the Senate on March 14, 2018, following the inclusion of a manager's amendment that added a number of provisions to the bill as reported.1 The House passed P.L. 115-174 on May 22, 2018, and President Donald Trump signed it into law on May 24, 2018.

P.L. 115-174 changes a number of financial regulations; its six titles alter certain aspects of the regulation of banks, capital markets, mortgage lending, and credit reporting agencies. Many of the provisions can be categorized as providing regulatory relief to banks and certain companies accessing capital markets. Others are designed to relax mortgage lending rules and provide additional protections to consumers, including protections related to credit reporting, veterans' mortgage refinancing, and student loans.

Some P.L. 115-174 provisions amend the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act; P.L. 111-203), regulatory reform legislation enacted following the 2007-2009 financial crisis that initiated the largest change to the financial regulatory system since at least 1999.2 Other provisions amend certain rules implemented by bank regulators under existing authorities and which closely adhere to the Basel III Accords—the international bank regulation standards-setting agreement. Finally, other provisions address long-standing or more recent issues not directly related to Dodd-Frank or Basel III.

Proponents of the legislation assert it provides targeted financial regulatory relief that eliminates a number of unduly burdensome regulations, fosters economic growth, and strengthens consumer protections.3 Opponents of the legislation argue it needlessly pares back important Dodd-Frank safeguards and protections to the benefit of large and profitable banks.4

Prior to passage of P.L. 115-174, the House and the Administration had also proposed wide-ranging financial regulatory relief plans. In terms of the policy areas addressed, some of the changes in P.L. 115-174 are similar to those proposed in the Financial CHOICE Act (FCA; H.R. 10), which passed the House on June 8, 2017 (see Appendix B).5 However, the two bills generally differ in the scope and degree of proposed regulatory relief. The FCA calls for widespread changes to the regulatory framework across the entire financial system, whereas P.L. 115-174 is more focused on the banking industry, mortgages, capital formation, and credit reporting. Likewise, many of the provisions found in P.L. 115-174 parallel regulatory relief recommendations made in the Treasury Department's series of reports pursuant to Executive Order 13772, particularly the first report on banks and credit unions.6 The Treasury reports are more wide-ranging than P.L. 115-174, however, and more focused on changes that can be made by regulators without congressional action.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that P.L. 115-174 would reduce the budget deficit by $23 million over 10 years.7 CBO estimated that only one provision would reduce the deficit—Section 217 requires the Federal Reserve (Fed) to transfer $675 million from its surplus account to the Treasury, where it is added to general revenues. CBO estimated that this provision would increase revenues by $478 million on net over 10 years.8 CBO assumed when making the estimate that the Fed would finance the transfer by selling Treasury securities, which otherwise would have earned $177 million in income that would have been remitted to the Treasury in the next 10 years. Thus, the provision can be thought of as shifting Fed remittances from the future to the present, as opposed to representing new economic resources available to the federal government. Various other provisions are forecast to increase the deficit, with the three provisions with the largest effect on the deficit being the community bank leverage ratio (Section 201), changes to the enhanced regulation threshold (Section 401), and changes to the supplementary leverage ratio for custody banks (Section 402).9

This report summarizes P.L. 115-174 as enacted and highlights major policy proposals of the legislation. Most changes proposed by P.L. 115-174, as passed, can be grouped into one of five issue areas: (1) mortgage lending, (2) regulatory relief for "community" banks, (3) consumer protection, (4) regulatory relief for large banks, and (5) regulatory relief in securities markets. The report provides background on each policy area, describes the P.L. 115-174 provisions that make changes in these areas, and examines the prominent policy issues related to those changes. In its final section, this report also provides an overview of provisions that do not necessarily relate directly to these five topics. This report also includes a contact list of CRS experts on topics addressed by P.L. 115-174, a summary of various exemption thresholds created or raised by P.L. 115-174 in Appendix A, and a list of provisions in P.L. 115-174 that address similar issues as a number of House bills in Appendix B.

Amending Mortgage Rules

Title I of P.L. 115-174 is intended to reduce the regulatory burden involved in mortgage lending and to expand credit availability, especially in certain market segments. Following the financial crisis, in which lax mortgage standards are believed by certain observers to have played a role, new mortgage regulations were implemented and some existing regulations were strengthened. Some analysts are now concerned that certain new and long-standing regulations unduly impede the mortgage process and unnecessarily restrict the availability of mortgages. To address these concerns, several provisions in P.L. 115-174 are designed to relax mortgage rules, including by providing relief to small lenders and easing rules related to specific mortgage types or markets. Other analysts argue that market developments have contributed to a tightening of mortgage credit and, though some changes to regulations may be desirable, the regulatory structure in place prior to the enactment of P.L. 115-174 generally provided important consumer protections.

Background10

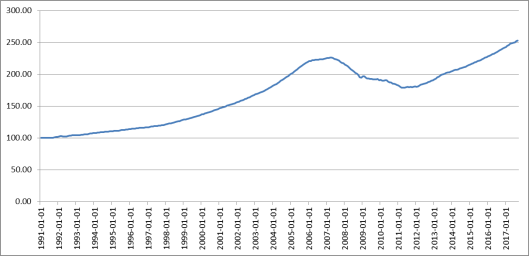

The bursting of the housing bubble in 2007 preceded the December 2007-June 2009 recession and a financial panic in September 2008. As shown in Figure 1, house prices rose significantly between 1991 and 2007 and then declined sharply for several years. Nationwide house prices did not return to their peak levels until the end of 2015. The decrease in house prices reduced household wealth and resulted in a surge in foreclosures. This had negative effects on homeowners and contributed to the financial crisis by straining the balance sheets of financial firms that held nonperforming mortgage products.

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS using data from the Federal Housing Finance Agency House Price Index (Seasonally Adjusted Purchase-Only Index). Note: January 1991 is set to 100 for this index. |

Many factors contributed to the housing bubble and its collapse, and there is significant debate about the underlying causes even a decade later. Many observers, however, point to relaxed mortgage underwriting standards, an expansion of nontraditional mortgage products, and misaligned incentives among various participants as underlying causes.11

Mortgage lending has long been subject to regulations intended to protect homeowners and to prevent risky loans, but the issues evident in the financial crisis spurred calls for reform. The Dodd-Frank Act made a number of changes to the mortgage system, including establishing the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB)12—which consolidated many existing authorities and established new authorities, some of which pertained to the mortgage market—and creating numerous consumer protections in Dodd-Frank's Title XIV, which was called the Mortgage Reform and Anti-Predatory Lending Act.13

A long-standing issue in the regulation of mortgages and other consumer financial services is the perceived trade-off between consumer protection and credit availability. If regulation intended to protect consumers increases the cost of providing a financial product, some lenders may charge a higher price and provide the service more selectively.14 Those who still receive the product may benefit from the enhanced disclosure or added legal protections of the regulation, but that benefit may result in a higher price for the product.

Some policymakers generally believe that the postcrisis mortgage rules have struck the appropriate balance between protecting consumers and ensuring that credit availability is not restricted due to overly burdensome regulations. They contend that the regulations are intended to prevent those unable to repay their loans from receiving credit and have been appropriately tailored to ensure that those who can repay are able to receive credit.15

Critics counter that some rules have imposed compliance costs on lenders of all sizes, resulting in less credit available to consumers and restricting the types of products available to them. Some assert this is especially true for certain nonstandard types of mortgages, such as mortgages for homes in rural areas or for manufactured housing. They further argue that the rules for certain types of lenders, usually small lenders, are unduly burdensome.16

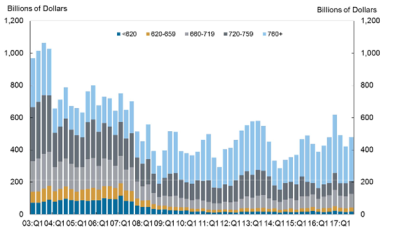

A variety of experts and organizations attempt to measure the availability of mortgage credit, and although their methods vary, it is generally agreed that mortgage credit is tighter than it was in the years prior to the housing bubble and subsequent housing market turmoil. Figure 2 shows that mortgage originations to borrowers with FICO credit scores below 720 have decreased in absolute and percentage terms. However, no consensus exists on whether or to what degree mortgage rules have unduly restricted the availability of mortgages, in part because it is difficult to isolate the effects of rules and the effects of broader economic and market forces. For example, the supply of homes on the market, demand for those homes, and demographic trends may also be playing a role.17 In addition, whether a tightening of credit should be interpreted as a desirable correction to precrisis excesses or an unnecessary restriction on credit availability is subject to debate.

|

|

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit, 2017 Q3, p. 6, at https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/interactives/householdcredit/data/pdf/HHDC_2017Q3.pdf. |

Provisions and Selected Analysis

Title I contains 10 sections that amend various laws that affect relatively small segments of the nation's mortgage market. Some sections pertain to consumer protection, and are generally intended to relax consumer protections in areas and markets in which the costs of these regulations are thought by some observers to be high relative to the rest of the mortgage market. In some cases, the legislation removes perceived regulatory barriers to the efficient functioning of specific segments of the mortgage market. Other provisions aim to balance safety and soundness concerns with concerns about access to credit.

Section 101—Qualified Mortgage Status for Loans Held by Small Banks

Provision

Section 101 creates a new qualified mortgage (QM) compliance option for mortgages that depositories with less than $10 billion in assets originate and hold in portfolio. To be eligible, the lender has to consider and document a borrower's debts, incomes, and other financial resources, and the loan has to satisfy certain product-feature requirements.

Analysis

Title XIV of the Dodd-Frank Act established the ability-to-repay (ATR) requirement to address problematic market practices and policy failures that some policymakers believe fueled the housing bubble that precipitated the financial crisis. Under the ATR requirement, a lender must verify and document that, at the time a mortgage is made, the borrower has the ability to repay the loan. Lenders that fail to comply with the ATR rule could be subject to legal liability, such as the payment of certain statutory damages.18

The CFPB issued regulations in January 2013 implementing the ATR requirement. A lender can comply with the ATR requirement in different ways, one of which is by originating a QM. When a lender originates a QM, it is presumed to have complied with the ATR requirement, which consequently reduces the lender's potential legal liability for its residential mortgage lending activities. The definition of a QM, therefore, is important to a lender seeking to minimize the legal risk of its residential mortgage lending activities, specifically its compliance with the statutory ATR requirement.

The Dodd-Frank Act provides a general definition of a QM, but also authorizes CFPB to issue "regulations that revise, add to, or subtract from" the general statutory definition.19 The CFPB-issued QM regulations establish a Standard QM that meets all of the underwriting and product-feature requirements outlined in the Dodd-Frank Act. However, the QM regulations also establish several additional categories of QMs, one of which is the Small Creditor Portfolio QM, which provide lenders the same presumption of compliance with the ATR requirement as the Standard QM. Compared with the Standard QM compliance option, the Small Creditor Portfolio QM has less prescriptive underwriting requirements. It is intended to reduce the regulatory burden of the ATR requirement for certain small lenders.

A mortgage can qualify as a Small Creditor Portfolio QM if three broad sets of criteria are satisfied.20 First, the loan must be held in the originating lender's portfolio for at least three years (subject to several exceptions). Second, the loan must be held by a small creditor, which is defined as a lender that originated 2,000 or fewer mortgages in the previous year and has less than $2 billion in assets. Third, the loan must meet the underwriting and product-feature requirements for a Standard QM except for the debt-to-income ratio.

Some argue that the QM definition has led to an unnecessary constriction of credit and has been unduly burdensome for lenders. In particular, critics argue that not all of the lender and underwriting requirements included in the Small Creditor Portfolio QM are essential to ensuring that a lender will verify a borrower's ability to repay, and instead argue that holding the loan in portfolio is sufficient to encourage thorough underwriting.21

By keeping the loan in portfolio, lenders have added incentive to consider whether the borrower will be able to repay the loan. Keeping the loan in portfolio means that the lender retains the default risk and could be exposed to losses if the borrower does not repay. This retained risk, the argument goes, encourages small creditors to provide additional scrutiny during the underwriting process, even in the absence of a legal requirement to do so. The expanded portfolio option, according to supporters, will spur lenders to offer more mortgages and reduce the burden associated with the more prescriptive underwriting standards of the existing QM options. The less prescriptive standards could most benefit creditworthy borrowers with atypical financial situations, such as self-employed individuals or seasonal employees, who may have a difficult time conforming to the existing standards.

As summarized in Table 1, P.L. 115-174 creates a new compliance option for lenders who keep a mortgage in portfolio in addition to the existing Small Creditor Portfolio QM. Compared with the CFPB's Small Creditor Portfolio QM, P.L. 115-174 allows larger lenders to use the portfolio compliance option (raising the asset threshold from $2 billion to $10 billion and eliminating the origination limits) but limits the new option to insured depositories (banks and credit unions) rather than to both depository and nondepository lenders. The new portfolio option created by P.L. 115-174 has more restrictive portfolio requirements, requiring lenders to hold the loan in portfolio for the life of the loan (with certain exceptions) rather than for just three years. However, the P.L. 115-174 option has more relaxed loan criteria. Lenders have to comply with some product-feature restrictions, but those restrictions are generally less stringent than under the other compliance option. In addition, P.L. 115-174 relaxes underwriting criteria, requiring lenders to consider and document a borrower's debts, incomes, and other financial resources in accordance with less prescriptive guidance than is required under certain other QM option criteria.

Table 1. Comparison of P.L. 115-174 to the CFPB's Small Creditor Portfolio QM

|

CFPB's Small Creditor Portfolio QM |

||

|

Portfolio Requirements |

Mortgage must be held in portfolio for three years. It may be transferred to another small lender and retain QM status. |

Mortgage must be held in portfolio by the originator. It may be transferred and retain QM status under certain limited circumstances. |

|

Lender Restrictions |

Limited to small lenders (depositories and nondepositories) with less than $2 billion in assets and fewer than 2,000 originations a year (excluding those held in portfolio). |

Limited to small insured depositories (banks and credit unions) with less than $10 billion in assets. |

|

Loan Criteria |

Loan must satisfy the underwriting and product feature requirements of the Standard QM Option, with the exception of the Standard QM Option's DTI requirement. |

Loan must satisfy fewer product-feature restrictions and less prescriptive underwriting guidance than the CFPB's Small Creditor Portfolio QM. |

Source: Table created by the Congressional Research Service.

Notes: QM = qualified mortgage. DTI = debt-to-income ratio. CFPB Small Creditor Portfolio QM refers to compliance option available in 12 C.F.R. §1026.43.

Although supporters of the expanded portfolio QM option in P.L. 115-174 argue that the new compliance option will expand credit availability and appropriately align the incentives of the borrower and lender, critics of the proposal counter that the incentives of holding the loan in portfolio are insufficient to protect consumers and that the protections in the rule in place prior to the enactment of P.L. 115-174 are needed to ensure that the hardships caused by the housing crisis are not repeated.

Section 102—Charitable Tax Deduction for Appraisals

Under current law,22 appraisers who meet certain criteria (such as an appraiser who is not an employee of the mortgage loan originator) are required to be compensated at a rate that is customary and reasonable for appraisal services in the market in which the appraised property is located. During the buildup of the housing bubble and its subsequent bust, house prices rose quickly and then fell steeply in many parts of the country, causing some policymakers to question the accuracy of the appraisals that supported the mortgage loans during the housing bubble, and the independence of the appraisers. The customary-and-reasonable fee requirement in current law is intended to help ensure that appraisers are acting with appropriate independence and not in the interest of the lender, seller, borrower, or other interested party. However, some have argued that the requirement for appraisers to receive a customary and reasonable fee made it difficult for them to donate their services to charitable organizations. Section 102 allows appraisers to donate their appraisal services to a charitable organization eligible to receive tax-deductible charitable contributions, such as Habitat for Humanity, by clarifying that a donated appraisal service to a charitable organization would not be in violation of the customary-and-reasonable fee requirement.

Section 103—Exemption from Appraisals in Rural Areas

Provision

The Dodd-Frank Act strengthened appraisal requirements after concerns were raised about the role that inaccurate appraisals played in the housing crisis. In recent years, there have been reports of shortages of qualified appraisers, especially in rural areas.23 Section 103 waives the general requirement for independent home appraisals for federally related mortgages in rural areas where the lender has contacted three state-licensed or state-certified appraisers who could not complete an appraisal in "a reasonable amount of time."24 An originator who makes a loan without an appraisal could sell the mortgage only under certain circumstances, such as bankruptcy.

Section 104—Home Mortgage Disclosure Act Adjustment

Provision

Section 104 exempts banks and credit unions from certain Home Mortgage and Disclosure Act (HMDA; P.L. 94-200) reporting requirements—generally new requirements implemented by the Dodd-Frank Act.25 Lenders that have originated fewer than 500 closed-end mortgage loans in each of the preceding two years qualify for reduced reporting on those loans and lenders originating fewer than 500 open-end lines of credit in each of the preceding two years qualify for reduced reporting on those loans, provided they achieve certain Community Reinvestment Act compliance scores.

HMDA, which was originally enacted in 1975, requires most lenders to report data on their mortgage business so that the data can be used to assist (1) "in determining whether financial institutions are serving the housing needs of their communities"; (2) "public officials in distributing public-sector investments so as to attract private investment to areas where it is needed"; and (3) "in identifying possible discriminatory lending patterns."26 The Dodd-Frank Act required lenders to collect additional data through HMDA, such as points and fees payable at origination, the term of the mortgage, and certain information about the interest rate. Currently, depository lenders generally have to comply with the HMDA reporting requirements if they have $45 million or more of assets, originated at least 25 home purchase loans in each of the previous two years, and satisfied other criteria.27 Section 104 exempts additional depository lenders from most of the HMDA requirements that were added by the Dodd-Frank Act.

Section 105—Credit Union Loans for Nonprimary Residences

Provision

Section 105 excludes loans made by a credit union for a single-family home that is not the member's primary residence from the definition of a member business loan.28 Credit unions face certain restrictions on the type and volume of loans that they can originate. One such restriction relates to member business loans. A member business loan means "any loan, line of credit, or letter of credit, the proceeds of which will be used for a commercial, corporate or other business investment property or venture, or agricultural purpose," with some exceptions, made to a credit union member.29 The aggregate amount of member business loans made by a credit union must be the lesser of 1.75 times the credit union's actual net worth, or 1.75 times the minimum net worth amount required to be well capitalized. A loan for a single-family home that is a primary residence is not considered a member business loan, but a similar loan for a nonprimary residence, such as an investment property or vacation home, was considered a member business loan prior to the enactment of P.L. 115-174. Section 105 modifies the definition such that nonprimary residence transactions are excluded from the member business loan definition.

Section 106—Mortgage Loan Originator Licensing and Registration

Provision

Section 106 allows certain state-licensed mortgage loan originators (MLOs) who are licensed in one state to temporarily work in another state while waiting for licensing approval in the new state. It also grants MLOs who move from a depository institution (where loan officers do not need to be state licensed) to a nondepository institution (where they do need to be state licensed) a grace period to complete the necessary licensing.

Under the Secure and Fair Enforcement for Mortgage Licensing Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-289; SAFE Act),30 MLOs who work for a bank must register with the National Mortgage Licensing System and Registry (NMLS), and those working for a nonbank mortgage lender must be licensed and registered in their state. Supporters of the original 2008 legislation argued that without registration and licensing, unscrupulous or incompetent MLOs may be able to move from job to job to escape the consequences of their actions. For MLOs at nonbank lenders, the process of becoming licensed and registered in a state can be time intensive, involving criminal background checks and prelicensing education. This could potentially be problematic for individuals moving (1) from a bank lender to a nonbank lender, or (2) from a nonbank lender in one state to a nonbank lender in another state. To address transition issues, Section 106 provides grace periods to allow individuals who are transferring positions in the situations mentioned above (and meet other performance criteria, such as not having previously had his or her license revoked or suspended) to become appropriately licensed and registered.

Section 107—Manufactured Homes Retailers

Provision

In response to problems in the mortgage market when the housing bubble burst, the SAFE Act and the Dodd-Frank Act established new requirements for mortgage originators' licensing, registration, compensation, and training, among other practices. A mortgage originator is someone who, among other things, "(i) takes a residential mortgage loan application; (ii) assists a consumer in obtaining or applying to obtain a residential mortgage loan; or (iii) offers or negotiates terms of a residential mortgage loan."31 The definition used in implementing the regulation in place at the time of the enactment of P.L. 115-174 excluded employees of manufactured-home retailers under certain circumstances, such as "if they do not take a consumer credit application, offer or negotiate credit terms, or advise a consumer on credit terms."32 Section 107 expands the exception such that retailers of manufactured homes or their employees are not be considered mortgage originators if they do not receive more compensation for a sale that included a loan than for a sale that did not include a loan, and if they provide customers certain disclosures about their affiliations with other creditors.

Section 108—Escrow Requirements Relating to Certain Consumer Credit Transactions

Provision

Section 108 exempts any loan made by a bank or credit union from certain escrow requirements if the institution has assets of $10 billion or less, originated fewer than 1,000 mortgage loans in the preceding year, and meets certain other criteria.

An escrow account is an account that a "mortgage lender may set up to pay certain recurring property-related expenses ... such as property taxes and homeowner's insurance."33 Escrow accounts may only be used for the purpose they were created. For example, a mortgage escrow account can only be used to pay for expenses (such as property taxes) for that mortgage, not for the mortgage lender's general expenses. Escrow accounts provide a way for homeowners to make monthly payments for annual or semi-annual expenses. Maintaining escrow accounts for borrowers are potentially costly for some banks, such as certain small institutions.

Higher-priced mortgage loans have been required to maintain an escrow account for at least one year pursuant to a regulation that was implemented before the Dodd-Frank Act.34 The Dodd-Frank Act, among other things, extended the amount of time an escrow account for a higher-priced mortgage loan must be maintained from one year to five years, although the escrow account can be terminated after five years if certain conditions are met. It also provided additional disclosure requirements.35

The Dodd-Frank Act gave the CFPB the discretion to exempt from certain escrow requirements lenders operating in rural areas if the lenders satisfied certain conditions.36 The CFPB's escrow rule included exemptions from escrow requirements for lenders that (1) operate in rural or underserved areas; (2) extend 2,000 mortgages or fewer; (3) have less than $2 billion in total assets; and (4) do not escrow for any mortgage they service (with some exceptions).37 Additionally, a lender that satisfies the above criteria must intend to hold the loan in its portfolio to be exempt from the escrow requirement for that loan. Section 108 amends the exemption criteria such that a bank or credit union also are exempt from maintaining an escrow account for a mortgage as long as it has assets of $10 billion or less, originated fewer than 1,000 mortgage loans in the preceding year, and met certain other criteria.

Section 109—Waiting Period Requirement for Lower-Rate Mortgage

Provision

The Dodd-Frank Act directed the CFPB to combine mortgage disclosures required under the Truth in Lending Act (P.L. 90-321; TILA) and Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (P.L. 93-533; RESPA) into a TILA-RESPA Integrated Disclosure (TRID) form. On November 20, 2013, the CFPB issued the TRID final rule that would require lenders to use the streamlined disclosure forms. Under current law,38 a borrower generally must receive the disclosures at least three days before the closing of the mortgage. After receiving their required disclosures, borrowers have in some cases been offered new mortgage terms by their lender, which requires new disclosures and potentially delays their mortgage closing. Section 109 waives the three-day waiting period between a consumer receiving a mortgage disclosure and closing on the mortgage if a consumer receives an amended disclosure that includes a lower interest rate than was offered in the previous disclosure.

Section 109 also expresses the sense of Congress that the CFPB should provide additional guidance on certain aspects of the final rule, such as whether lenders receive a safe harbor from liability if they use model disclosures published by the CFPB that do not reflect regulatory changes issued after the model forms were published.

Regulatory Relief for Community Banks

Title II of P.L. 115-174 is focused on providing regulatory relief to community banks. Although small banks qualify for various exemptions from certain regulations, whether the regulations have been appropriately tailored is the subject of debate. Certain Title II provisions raise previous asset thresholds or create new ones at which banks and other depositories are exempt from regulation or otherwise qualify for reduced regulatory obligations.

Background39

The term community bank typically refers to a small bank focused on a traditional commercial bank business of taking deposits and making loans to meet the financial needs of a particular community. Although conceptually size does not necessarily have to be a determining factor, community banks are nevertheless often identified as such based on having a small asset size. No consensus exists on what size limit is compatible with the community bank concept, and some observers doubt the effectiveness of size-based measures in identifying community banks.40

Community banks are more likely to be concentrated in core commercial bank businesses of making loans and taking deposits and less concentrated in other activities like securities trading or holding derivatives. Community banks also tend to operate within a smaller geographic area. Also, these banks are generally more likely to practice relationship lending, wherein loan officers and other bank employees have a longer-standing and perhaps more personal relationship with borrowers.41

Due in part to these characteristics, proponents of community banks assert that these banks are particularly important credit sources to local communities and otherwise underserved groups, as big banks may be unwilling to meet the credit needs of a small market of which they have little direct knowledge. If this is the case, imposing burdens on small banks that potentially restrict the amount of credit they make available could have a cost for these groups. In addition, relative to large banks, small banks individually pose less of a systemic risk to the broader financial system, and are likely to have fewer employees and resources to dedicate to regulatory compliance.42 Arguably, this means regulation aimed at systemic stability might produce little benefit at a high cost when applied to these banks.43

Thus, one rationale for easing the regulatory burden for community banks would be that regulation intended to increase systemic stability need not be applied to such banks since they individually do not pose a risk to the entire financial system. Sometimes the argument is extended to assert that because small banks did not cause the 2007-2009 crisis and pose less systemic risk, they need not be subject to new regulations.

Another potential rationale for easing regulations on small banks would be if there are economies of scale to regulatory compliance costs, meaning that as banks become bigger, their costs do not rise as quickly as asset size. From a cost-benefit perspective, if regulatory compliance costs are subject to economies of scale, then the balance of costs and benefits of a particular regulation will depend on the size of the bank. Although regulatory compliance costs are likely to rise with size, those costs as a percentage of overall costs or revenues are likely to fall. In particular, as regulatory complexity increases, compliance may become relatively more costly for small firms.44 Empirical evidence on whether compliance costs are subject to economies of scale is mixed.45 Some argue for reducing the regulatory burden on small banks on the grounds that they provide greater access to credit or offer credit at lower prices than large banks for certain groups of borrowers. These arguments tend to emphasize potential market niches small banks occupy that larger banks may be unwilling to fill.46 For these reasons, community banks differ from large institutions in a number of ways besides size that arguably could result in their being subject to certain regulations that are unduly burdensome—meaning the benefit of the regulation does not justify the cost.

Other observers assert that the regulatory burden facing small banks is appropriate, citing the special regulatory emphasis already given to minimizing small banks' regulatory burden. For example, during the rulemaking process, bank regulators are required to consider the effect of rules on small banks.47 In addition, they note that many regulations already include an exemption for small banks or are tailored to reduce the cost for small banks to comply. Supervision is also structured to put less of a burden on small banks than larger banks, such as by requiring less frequent bank examinations for certain small banks.48 Furthermore, they counter that although small institutions were not a major cause of the past crisis, they did play a prominent role in the savings and loan crisis of the late 1980s, a systemic event that cost taxpayers $124 billion, according to one analysis.49 Also, they note that systemic risk is only one of the goals of regulation, along with prudential regulation and consumer protection, and argue that the failure of hundreds of banks during the crisis illustrates that precrisis prudential regulation for small banks was not stringent enough.50

Provisions and Selected Analysis

This section reviews eight provisions in Title II that amend various laws and regulations that affect depositories, including banks, federal savings associations, and credit unions. Although some provisions relax certain regulations for all banks, Title II provisions are generally aimed at providing regulatory relief to institutions under certain asset thresholds. Several sections amend prudential regulation rules, including minimum capital requirements and the Volcker Rule, whereas others are designed to reduce supervisory requirements by decreasing exam frequency and reporting requirements for small banks. Other sections in Title II are related to public housing, insurance, and the National Credit Union Administration and are described in the "Miscellaneous Proposals in P.L. 115-174" section.

Section 201—Community Bank Leverage Ratio

Provision

Section 201 directs regulators to develop a Community Bank Leverage Ratio (CBLR) and set a threshold ratio of between 8% and 10% capital to unweighted assets—compared with the general leverage ratio requirement of 5%—to be considered well capitalized. If a bank with less than $10 billion in assets maintains a CBLR above that threshold, it will be exempt from all other leverage and risk-based capital requirements. Banking regulators may determine that an individual bank with under $10 billion in assets is not eligible to be exempt based on its risk profile.

Analysis

Capital—defined by the legislation as tangible equity (e.g., ownership shares)51—gives a bank the ability to absorb losses without failing, and regulators set minimum amounts a bank must hold. These capital requirements are expressed as capital ratio requirements—ratios of a bank's assets and capital. The ratios are generally one of two main types—a risk-weighted capital ratio or a leverage ratio. Risk-weighted ratios assign a risk weight—a number based on the riskiness of the asset that the asset value is multiplied by—to account for the fact that some assets are more likely to lose value than others. Riskier assets receive a higher risk weight, which requires banks to hold more capital—to better enable them to absorb losses—to meet the ratio requirement.52 In contrast, leverage ratios treat all assets the same, requiring banks to hold the same amount of capital against the asset regardless of how risky each asset is.

Whether multiple risk-based capital ratios should be replaced with a single leverage ratio is subject to debate. Some observers argue that it is important to have both risk-weighted ratios and a leverage ratio because the two complement each other. Riskier assets generally offer a greater rate of return to compensate the investor for bearing more risk. Without risk weighting, banks may have an incentive to hold riskier assets because the same amount of capital would be required to be held against risky, high-yielding assets and safe, low-yielding assets. Therefore, a leverage ratio alone—even if set at higher levels—may not fully account for a bank's riskiness because a bank with a high concentration of very risky assets could have a similar ratio to a bank with a high concentration of very safe assets.53

However, others assert the use of risk-weighted ratios should be optional, provided a high leverage ratio is maintained.54 Risk weights assigned to particular classes of assets could potentially be an inaccurate estimation of some assets' true risk, especially because they cannot be adjusted as quickly as asset risk might change. Banks may have an incentive to overly invest in assets with risk weights that are set too low (they would receive the high potential rate of return of a risky asset, but have to hold only enough capital to protect against losses of a safe asset), or inversely to underinvest in assets with risk weights that are set too high. Some observers believe that the risk weights in place prior to the financial crisis were poorly calibrated and "encouraged financial firms to crowd into" risky assets, exacerbating the downturn.55 For example, banks held highly rated mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) before the crisis, in part because those assets offered a higher rate of return than other assets with the same risk weight. MBSs then suffered unexpectedly large losses during the crisis.

Some critics of the current requirements are especially opposed to their application to small banks. They argue that the risk-weighted system involves "needless complexity" and is an example of regulator micromanagement.56 Furthermore, they say, that complexity could benefit the largest banks that have the resources to absorb the added regulatory cost compared with small banks that could find compliance costs relatively more burdensome. Thus, they contend that a simpler system should be implemented for small banks to avoid giving large banks a competitive advantage over them.

In its cost estimate, CBO assumed that regulators would select a 9% leverage ratio and estimates that 70% of community banks will opt in to the new leverage regime. As a result, they forecasted that some community banks would take on more risk and increase the likelihood that more community banks will fail than would under the general capital and leverage ratio regime. CBO estimated that this will raise costs to the Deposit Insurance Fund by $240 million, about half of which would be offset by higher insurance premiums over the 10-year budget window.57

For further information on leverage and capital ratios, see CRS In Focus IF10809, Financial Reform: Bank Leverage and Capital Ratios, by [author name scrubbed].

Section 202—Allowing More Banks to Accept Reciprocal Deposits

Provision

Section 202 makes reciprocal deposits—deposits that two banks place with each other in equal amounts—exempt from the prohibitions against taking brokered deposits faced by banks that are not well capitalized (i.e., those that may hold enough capital to meet the minimum requirements, but not by the required margins to be classified as well capitalized), subject to certain limitations.

Analysis

Certain deposits at banks are not placed there by individuals or companies utilizing the safekeeping, check writing, and money transfer services the banks provide. Instead, brokered deposits are placed by a third-party broker that places clients' savings in accounts paying higher interest rates. Regulators consider these deposits less stable, because brokers are more willing to withdraw them and move them to another bank than individuals and companies who face higher switching costs and inconvenience when switching banks (e.g., filling out and submitting new direct deposit forms to one's employer, getting new checks, and changing automatic bill payment information). Due to these characteristics, regulators generally prohibit not-well-capitalized banks from accepting brokered deposits in order to limit potential losses to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) in the event the bank fails.

Section 202 allows certain not-well-capitalized banks to accept a particular type of brokered deposit called reciprocal deposits, an arrangement between two banks in which each bank places a portion of its own customers' deposits with the other bank. Generally, the purpose of this transaction is to ensure that large accounts stay under the $250,000-per-account deposit insurance limit, with any amount in excess of the limit placed in a separate account at another bank. Like other brokered deposits, reciprocal deposits are funding held by a bank that does not have a relationship with the underlying depositors. However, reciprocal deposits differ from other brokered deposits in that if reciprocal deposits are withdrawn from a bank, the bank receives its own deposits back and thus may better maintain its funding.

CBO estimated that Section 202 would increase the budget deficit by $25 million over 10 years because permitting reciprocal deposits will increase deposit insurance payouts from bank failures, imposing losses on the FDIC insurance fund that would not fully be offset by higher deposit insurance premiums within the 10-year budget window.58

Section 203 and 204—Changes to the Volcker Rule

Provision

Section 203 creates an exemption from prohibitions on propriety trading—owning and trading securities for the bank's own portfolio with the aim of profiting from price changes—and relationships with certain investment funds for banks with (1) less than $10 billion in assets, and (2) trading assets and trading liabilities less than 5% of total assets. Pursuant to Section 619 of the Dodd-Frank Act, often referred to as the "Volcker Rule," bank organizations generally face these prohibitions.59 In addition to Section 203's exemption for small banks, Section 204 eases certain Volcker Rule restrictions on all bank entities, regardless of size, related to sharing a name with hedge funds and private equity funds they organize.

Analysis

The Volcker Rule generally prohibits banking entities from engaging in proprietary trading or sponsoring a hedge fund or private equity fund. Proponents of the rule argue that proprietary trading adds further risk to the inherently risky business of commercial banking. Furthermore, they assert that other types of institutions are very active in proprietary trading and better suited for it, so bank involvement in these markets is unnecessary for the financial system.60 Finally, proponents assert moral hazard is problematic for banks in these risky activities. Because deposits—an important source of bank funding—are insured by the government, a bank could potentially take on excessive risk without concern about losing this funding. Thus, support for the Volcker Rule has often been posed as preventing banks from "gambling" in securities markets with taxpayer-backed deposits.61

Some observers doubt the necessity and the effectiveness of the Volcker Rule in general. They assert that proprietary trading at commercial banks did not play a role in the financial crisis, noting that issues that played a direct role in the crisis—including failures of large investment banks and insurers, and losses on loans held by commercial banks—would not have been prevented by the rule.62 In addition, although the activities prohibited under the Volcker Rule pose risks, it is not clear whether they pose greater risks to bank solvency and financial stability than "traditional" banking activities, such as mortgage lending. Taking on additional risks in different markets potentially could diversify a bank's risk profile, making it less likely to fail.63 Some contend the rule poses practical supervisory problems. The rule includes exceptions for when bank trading is deemed appropriate—such as when a bank is hedging against risks and market-making—and differentiating among these motives creates regulatory complexity and compliance costs that could affect bank trading behavior.64

In addition to the broad debate over the necessity and efficacy of the Volcker Rule, whether small banks should be subjected to the rule is also a debated issue. Proponents of the rule contend that the vast majority of community banks do not face compliance obligations under the rule, and so do not face an excessive burden by being subject to it. They argue that those community banks that are subject to compliance obligations can comply simply by having clear policies and procedures in place that can be reviewed during the normal examination process. In addition, they assert the small number of community banks that are engaged in complex trading should have the expertise to comply with the Volcker Rule.65

Others argue that the act of evaluating the Volcker Rule to ensure banks' compliance is burdensome in and of itself. They support a community bank exemption so that community banks and supervisors do not have to dedicate resources to complying with and enforcing a regulation whose rationale is unlikely to apply to smaller banks.66

Section 205—Financial Reporting Requirements for Small Banks

Provision

Section 205 directs the federal banking agencies to issue regulations to reduce the reporting requirements that banks with assets under $5 billion must comply with in the first and third quarters of the year. Currently, all banks must submit a report of condition and income to the federal bank agencies at the end of every financial quarter of the year, sometimes referred to as a "call report."67 Completing the call report involves entering numerous values into forms or "schedules" in order to provide the regulator with a detailed accounting of many aspects of each bank's income, expenses, and balance sheet. The filing requires an employee or employees to dedicate time to the exercise and in some cases banks purchase certain software products that assist in the task. Section 205 directs the regulators to shorten or simplify the reports banks with assets under $5 billion file in the first and third quarter.

For more information about bank supervision, including a discussion about bank financial reporting, see CRS In Focus IF10807, Financial Reform: Bank Supervision, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed].

Section 206—Allowing Thrifts to Opt-In to National Bank Regulatory Regime

Provision

Section 206 creates a mechanism for federal savings associations (or "thrifts") with under $20 billion in assets to opt out of the federal thrift regulatory regime and enter the national bank regulatory regime without having to go through the process of changing their charter. An institution that makes loans and takes deposits can have one of several types of charters—including a national bank charter and federal savings association charter, among others—each of which subjects the institutions to regulations that can differ in certain ways.68 Without this provision, if an institution wanted to switch from one regime to another, it would have to change its charter.

Historically, thrifts were intended to be institutions focused on residential home mortgage lending, and as such they are subject to regulatory limitations on how much of other types of lending they can do. Certain thrifts may want to expand their lending in other business lines, but be unable to do so because of these limitations. Without the mechanism provided by Section 206, if a thrift wanted to exceed the limitations, it would have to convert its charter to a national bank charter, which could potentially be costly.69

For more information on federal thrift chartering issues, see CRS In Focus IF10818, Financial Reform: Savings Associations or "Thrifts", by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed].

Section 207—Small Bank Holding Company Policy Statement Threshold

Provision

Section 207 raises the asset threshold in the Federal Reserve Small Bank Holding Company (BHC) and Small Saving and Loan Holding Company Policy Statement from $1 billion to $3 billion in total assets. In the policy statement, the Federal Reserve permits BHCs under the asset threshold to take on more debt in order to complete a merger (provided they meet certain other requirements concerning nonbank activities, off-balance-sheet exposures, and debt and equities outstanding) than would be allowed for a larger BHC.70 In addition, Section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Act (sometimes referred to as the "Collins Amendment") exempts BHCs subject to this policy statement from the requirement that banking organizations meet the same capital requirements at the holding company level that depository subsidiaries face.71 The significance of the Collins Amendment arguably depends on the extent to which a BHC has activities in nonbank subsidiaries, and many small banks do not have substantial activities in nonbank subsidiaries.

For more information on the Federal Reserve's Small Bank Holding Company Policy Statement, see CRS In Focus IF10837, Financial Reform: Small Bank Holding Company Threshold, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed].

Section 210—Frequency of Examination for Small Banks

Provision

Section 210 raises the asset threshold below which banks can become eligible for an 18-month examination cycle instead of a 12-month cycle from $1 billion to $3 billion. Generally, federal bank regulators must conduct an on-site examination of the banks they oversee at least once in each 12-month period. However, if a bank below the asset threshold meets certain criteria related to capital adequacy and scores received on previous examinations, then it can be examined only once every 18 months.72 Raising this threshold allows more banks to be subject to less frequent examination.

For more information about bank supervision, including a discussion about bank examinations, see CRS In Focus IF10807, Financial Reform: Bank Supervision, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed].

Section 213—Identification When Opening an Account Online

Provision

Section 213 permits financial institutions to use a scan of, make a copy of, or receive the image of a driver's license or identification card to record the personal information of a person requesting to open an account or for some other service through the internet.

Section 214—Classifying High Volatility Commercial Real Estate Loans

Provision

Section 214 allows banks to classify certain credit facilities (e.g., business loans, revolving credit, and lines of credit) that finance the acquisition, development, or construction of commercial properties as regular commercial real estate exposures instead of high volatility commercial real estate (HVCRE) exposures for the purposes of calculating their risk-weighted capital requirements, previously discussed in the Section 201 "Analysis" section. Prior to the enactment of P.L. 115-174, banks generally were required to classify facilities financing commercial real estate projects as HVCRE, unless the developer contributed capital of at least 15% of the estimated "as completed value" of the project. Under that rule, capital included cash, unencumbered readily marketable assets, and out of pocket-expenses. Being classified as HVCRE means the exposure must be given a risk weight of 150% instead of the 100% weight given to other CRE exposures, thus requiring banks to hold more capital to finance those projects.

Section 214 offers a number of additional avenues for commercial real estate exposures to avoid or shed HVCRE status. It allows the appraised value of the property being developed to count as a capital contribution, providing another avenue for projects to reach the minimum 15% threshold. In addition, Section 214 allows certain credit facilities financing the acquisition or improvement of already-income-producing properties to avoid classification as HVCRE, provided the cash flow is sufficient to support the property's debt service and other expenses. Finally, a HVCRE could achieve reclassification when the property development is substantially completed or when it begins generating cash flow sufficient to support the property's debt service and other expenses. A lower capital requirement gives banks greater incentive to make HVCRE loans, but provides banks with less capital cushion against potential losses on what has been historically a risky category of lending.

For further information on leverage and capital ratios, see CRS In Focus IF10809, Financial Reform: Bank Leverage and Capital Ratios, by [author name scrubbed].

Consumer Protections

Title III, Title VI, and Section 215 of Title II are intended to address various consumer protection challenges facing the credit reporting industry and borrowers in certain credit markets, such as active duty servicemembers, veterans, student borrowers, and borrowers funding energy efficiency projects.

Background73

Credit Reporting

The credit reporting industry collects and subsequently provides information to companies about behavior when consumers conduct various financial transactions. A credit report typically includes information related to a consumer's identity (such as name, address, and Social Security number), existing or recent credit transactions (including credit card accounts, mortgages, and other forms of credit), public record information (such as court judgments, tax liens, or bankruptcies), and credit inquiries made about the consumer.

Credit reports are prepared by credit reporting agencies (CRAs). The three largest CRAs—Equifax, TransUnion, and Experian—are the most well-known, but they are not the only CRAs. Approximately 400 smaller CRAs either are regional or specialize in collecting specific types of information or information for specific industries, such as information related to payday loans, checking accounts, or utilities.

Companies use credit reports to determine whether consumers have engaged in behaviors that could be costly or beneficial to the companies. For example, lenders rely upon credit reports and scoring systems to determine the likelihood that prospective borrowers will repay mortgage and other consumer loans. Insured depository institutions (i.e., banks and credit unions) rely on consumer data service providers to determine whether to make checking accounts or loans available to individuals. Insurance companies use consumer data to determine what insurance products to make available and to set policy premiums.74 Employers may use consumer data information to screen prospective employees to determine, for example, the likelihood of fraudulent behavior. In short, numerous firms rely upon consumer data to identify and evaluate the risks associated with entering into financial relationships or transactions with consumers.

Much of what is thought of as the business of credit reporting is regulated through the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA; P.L. 91-508).75 The FCRA requires "that consumer reporting agencies adopt reasonable procedures for meeting the needs of commerce for consumer credit, personnel, insurance, and other information in a manner which is fair and equitable to the consumer, with regard to the confidentiality, accuracy, relevancy, and proper utilization of such information."76 The FCRA establishes consumers' rights in relation to their credit reports, as well as permissible uses of credit reports. For example, the FCRA requires that consumers be told when their information from a CRA has been used after an adverse action (generally a denial of a loan) has occurred, and disclosure of that information must be made free of charge.77 Consumers have a right to one free credit report every year from each of the three largest nationwide credit reporting providers in the absence of an adverse action. Consumers have the right to dispute inaccurate or incomplete information in their report. The CRAs must investigate and correct, usually within 30 days. The FCRA also imposes certain responsibilities on those who collect, furnish, and use the information contained in consumers' credit reports.

Although the FCRA originally delegated rulemaking and enforcement authority to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the Dodd-Frank Act transferred that authority to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. The CFPB coordinates its enforcement efforts with the FTC's enforcements under the Federal Trade Commission Act.78 Since 2012, the CFPB has subjected the "larger participants" in the consumer reporting market to supervision.79 Previously, CRAs were not actively supervised for FCRA compliance on an ongoing basis.

How consumers' personal information is used and protected has been an area of concern. For example, if a fraudster is able to obtain a consumer's personal identifying information he or she could "steal" that person's identity, using it to obtain credit with no intention of repaying. The unpaid debt would then appear on the consumer's credit report, making him or her appear uncreditworthy and potentially resulting in a denial of credit or other adverse outcomes. In September 2017, Equifax announced a security breach80 in which the sensitive information of an estimated 145.5 million U.S. consumers was potentially compromised, which highlighted the importance of this issue.81

Veterans and Active Duty Servicemembers

Active duty military members are subject to sudden and often times dangerous deployments and assignments that require them to be away from home in a way that is unique from other professions and could adversely affect servicemembers' ability to meet financial obligations. As a result, a number of U.S. laws dating at least as far back as World War I are designed to ease the financial burden on military members and protect them from being financially mistreated.82 More recently, the Servicemembers Civil Relief Act (SCRA; P.L. 108-189) amended and expanded certain protections for active duty servicemembers. However, some observers assert servicemembers remain inadequately protected in certain transactions and markets, including in the reporting of medical debt to credit reporting agencies, home mortgage refinancing, and mortgage foreclosures.

Student Loans83

Aggregate student loan debt in the United States has increased markedly over time. According to the U.S. Department of Education (ED), "[a]verage tuition prices have more than doubled at U.S. colleges and universities over the past three decades, and over this time period a growing proportion of students borrowed money to finance their postsecondary education"84 The ED's Federal Student Aid Data Center estimated that the total amount of outstanding federal student loan debt exceeded $1.37 trillion at the end of the 2017 fiscal year.85

As overall student loan indebtedness has increased, some studies have suggested that repayment burdens facing many borrowers and co-signers have also increased. For example, statistics published by ED suggest that many borrowers face an average educational debt burden that exceeds the "manageable percentage of income that a borrower can" realistically "be expected to devote to loan payment,"86 although other studies have come to different conclusions.87 This has led some observers to broadly question whether appropriate protections are in place in this market. A specific area of concern are private student loans, which generally are not required to offer the same repayment relief, loan rehabilitation, and loan discharge options that are offered in federal student loans.88

Provisions and Selected Analysis

Section 215—Reducing Identity Theft

Provisions

Section 215 directs the Social Security Administration (SSA) to allow certain financial institutions to receive customers' consent by electronic signature to verify their name, date of birth, and Social Security number with SSA. In addition, the section directs SSA to modify their databases or systems to allow for the financial institutions to electronically and quickly request and receive accurate verification of the consumer data.

Some identity thefts use a technique called synthetic identity theft in which they apply for credit using a mixture of real, verifiable information of an existing person with fictitious information, thus creating a "synthetic" identity. Often these identity thieves use real Social Security numbers of people they know are unlikely to have existing credit files, such as children or recent immigrants.89 The SSA Consent-Based Social Security Number Verification system was created to fight identity fraud such as this, but prior to the enactment of P.L. 115-174 it required financial institutions to obtain a physical written signature to make a verification request. Some observers feel this requirement is outdated and time consuming, undermining the effectiveness of the program.90 Section 215 aims to modernize and make the SSA's verification system more efficient by allowing the use of electronic signatures.

Section 301—Fraud Alerts and Credit Report Security Freezes

Provisions

Section 301 amends the FCRA to require credit bureaus to provide fraud alerts for consumer files for at least one year (up from 90 days) when notified by an individual who believes he or she has been or may become a victim of fraud or identity theft. It also provides consumers the right to place (and remove) a security freeze on their credit reports free of charge. In addition, Section 301 creates new protections for the credit reports of minors.

A fraud alert is the inclusion in an individual's report, at the request of the individual, of a notice that the individual has reason to believe they might be the victim of fraud or identity theft. Generally, when a lender receives a credit report on a prospective borrower that includes a fraud alert, the lender must take reasonable steps to verify the identity of the prospective borrower, thus making it more difficult for a fraudster or identity thief to take out loans using the victim's identity. Prior to the enactment of P.L. 115-174, when an individual requested a fraud alert, the CRAs were required to include the alert in the credit report for 90 days, unless the individual asked for its removal sooner. Section 301 increases this period to one year.

A security freeze can be placed on an individual's credit report at the request of the individual (or in the case of a minor, at the request of an authorized representative), and generally prohibits the CRAs from disclosing the contents of the credit report for the purposes of new extensions of credit. If a consumer puts a security freeze on his or her credit report, it would make it harder to fraudulently open new credit lines using that consumer's identity.

Analysis

By lengthening the time fraud alerts stay on credit reports and by allowing consumers to place security freezes on their credit reports, Section 301 gives consumers the ability to make it more difficult for identity thieves to get credit using a victim's identity. Reducing the prevalence of erroneous information appearing on credit reports as a result of fraud would reduce the occurrence of defrauded consumers being denied credit on the basis of erroneous information. However, these protections can create some potential costs for lenders and consumers. While a fraud alert is active, the increased verification requirements could potentially increase costs for the lender. A security freeze restricts the use of credit report information in a credit transaction, reducing the information available to lenders and possibly reducing the consumer's access to credit. Although requesting a fraud alert or credit freeze be turned off or "lifted" during a period when a consumer expects to apply for new credit is not especially difficult, doing so is an additional step facing consumers seeking credit and requires some time and attention.91