Introduction

The Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (S. 2155) was reported by the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs on December 18, 2017. The bill is a broad proposal; its five titles would alter certain aspects of the regulation of banks, mortgage lending, and credit reporting agencies. Many of the provisions can be categorized as providing regulatory relief to banks. Others are designed to relax mortgage lending rules and provide additional protections to consumers related to credit reporting.

Some S. 2155 provisions would amend the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 111-203; Dodd-Frank Act), regulatory reform legislation enacted following the 2007-2009 financial crisis that initiated the largest change to the financial regulatory system since at least 1999.1 Other provisions would amend certain rules implemented by bank regulators in accordance with the Basel III Accords—the international bank regulation standards-setting agreement—under existing authorities. Finally, other provisions would address long-standing or more recent issues not directly related to Dodd-Frank or Basel III.

Proponents of the bill assert it would provide targeted financial regulatory relief that would eliminate a number of unduly burdensome regulations, foster economic growth, and strengthen consumer protections.2 Opponents of the bill argue it needlessly pares back important Dodd-Frank safeguards and protections to the benefit of large and profitable banks.3

In addition to S. 2155, the House and the Administration have also proposed wide-ranging financial regulatory relief plans. In terms of the policy areas addressed, some of the changes proposed in S. 2155 are similar to those proposed in the Financial CHOICE Act (H.R. 10; FCA), which passed the House on June 8, 2017.4 However, the two bills generally differ in the scope and degree of proposed regulatory relief. The FCA calls for widespread changes to the regulatory framework across the entire financial system, whereas S. 2155 is more focused on the banking industry, mortgages, and credit reporting. Likewise, many of the provisions found in S. 2155 parallel regulatory relief recommendations made in the Treasury Department's series of reports pursuant to Executive Order 13772, particularly the first report on banks and credit unions. The Treasury reports are more wide-ranging than S. 2155, however, and more focused on changes that can be made by regulators without congressional action.5

This report summarizes S. 2155 and highlights major policy proposals of the bill, as reported by committee. Most changes proposed by S. 2155, as reported, can be grouped into one of four issue areas: (1) mortgage lending, (2) regulatory relief for community banks, (3) credit reporting, and (4) regulatory relief for large banks. The report provides background on each policy area, describes the S. 2155 provisions that make changes in these areas, and examines the prominent policy issues related to those changes. In its final section, this report also provides an overview of provisions that do not necessarily relate directly to these four topics. This report also includes a contact list of CRS experts on topics addressed by S. 2155, and in the Appendix it summarizes various exemption thresholds created or raised by S. 2155.

Amending Mortgage Rules

Title I of S. 2155 is intended to reduce the regulatory burden involved in mortgage lending and to expand credit availability, especially in certain market segments. Following the financial crisis, in which lax mortgage standards are believed by certain observers to have played a role, new mortgage regulations were implemented and some existing regulations were strengthened. Some analysts are now concerned that certain new and long-standing regulations unduly impede the mortgage process and unnecessarily restrict the availability of mortgages. To address these concerns, several provisions in S. 2155 are designed to relax mortgage rules, including by providing relief to small lenders and easing rules related to specific mortgage types or markets. Other analysts argue that market developments have contributed to a tightening of mortgage credit and, though some changes to regulations may be desirable, the current regulatory structure generally provides important consumer protections.

Background

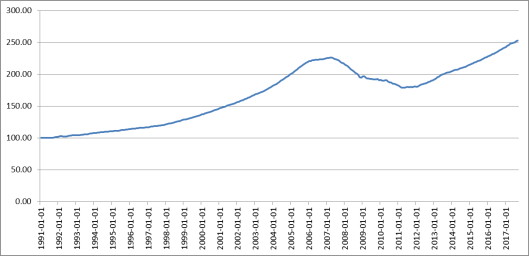

The bursting of the housing bubble in 2007 precipitated the December 2007-June 2009 recession and a financial panic in September 2008. As shown in Figure 1, house prices rose significantly during the early 2000s before peaking in 2007 and then falling for several years. House prices did not return to their peak levels until the end of 2015. The decrease in house prices reduced household wealth and resulted in a surge in foreclosures. This had negative effects on homeowners and contributed to the financial crisis by straining the balance sheets of financial firms that held nonperforming mortgage products.

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS using data from the Federal Housing Finance Agency House Price Index (Seasonally Adjusted Purchase-Only Index). Note: January 1991 is set to 100 for this index. |

Many factors contributed to the housing bubble and its collapse, and there is significant debate about the underlying causes even a decade later. Many observers, however, point to relaxed mortgage underwriting standards, an expansion of nontraditional mortgage products, and misaligned incentives among various participants as underlying causes.

Mortgage lending has long been subject to regulations intended to protect homeowners and to prevent risky loans, but the issues evident in the financial crisis spurred calls for reform. The Dodd-Frank Act made a number of changes to the mortgage system, including establishing the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB)—which consolidated many existing authorities and established new authorities, some of which pertained to the mortgage market—and creating numerous consumer protections in Dodd-Frank's Title XIV, which was called the Mortgage Reform and Anti-Predatory Lending Act.

A long-standing issue in the regulation of mortgages and other consumer financial services is the perceived trade-off between protecting consumers and ensuring that the providers of financial goods and services are not unduly burdened. If regulation intended to protect consumers increases the cost of providing a financial product, a company may reduce how much of that product it is willing to provide, and may provide it more selectively. Those who still receive the product may benefit from the enhanced disclosure or added legal protections of the regulation, but that benefit may result in a higher price for the product.

Some policymakers generally believe that the postcrisis mortgage rules have struck the appropriate balance between protecting consumers and ensuring that credit availability is not restricted due to overly burdensome regulations. They contend that the regulations are intended to prevent those unable to repay their loans from receiving credit and have been appropriately tailored to ensure that those who can repay are able to receive credit.

Critics counter that some rules have imposed compliance costs on lenders of all sizes, resulting in less credit available to consumers and restricting the types of products available to them. Some assert this is especially true for certain types of mortgages, such as mortgages for homes in rural areas or for manufactured housing. They further argue that the rules for certain types of lenders, usually small lenders, are unduly burdensome.

No consensus exists on whether or to what degree mortgage rules have unduly restricted the availability of mortgages, in part because it is difficult to isolate the effects of rules and the effects of broader economic and market forces. A variety of experts and organizations attempt to measure the availability of mortgage credit, and although their methods vary, it is generally agreed that mortgage credit is tighter than it was in the years prior to the housing bubble and subsequent housing market turmoil. However, whether this should be interpreted as a desirable correction to precrisis excesses or an unnecessary restriction on credit availability is subject to debate.

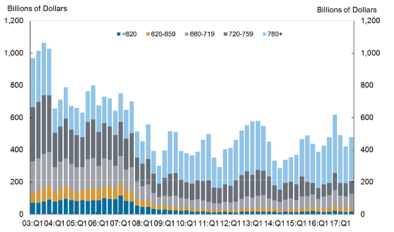

Figure 2 shows two ways credit has tightened: the number of new mortgage originations has decreased since the peak of the mortgage bubble, and borrowers' credit scores have generally increased. In addition to regulatory changes, economic conditions could be affecting both the supply of homes on the market and demand for those homes, and demographic trends may also be playing a role.6 As a result of this uncertainty, striking the right balance of credit access and risk management continues to be the subject of ongoing debate.

|

|

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit, 2017 Q3, p. 6, at https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/interactives/householdcredit/data/pdf/HHDC_2017Q3.pdf. |

Mortgage Provisions and Selected Analysis

Title I contains 10 sections that would amend various laws that affect relatively small segments of the nation's mortgage market. Some sections pertain to consumer protection, and are generally intended to relax consumer protections in areas and markets in which the costs of these regulations are high relative to the rest of the mortgage market. In some cases, the bill would remove perceived regulatory barriers to the efficient functioning of specific segments of the mortgage market. Other provisions balance safety and soundness concerns with concerns about access to credit.

Section 101—Qualified Mortgage Status for Loans Held by Small Banks

Provision

Section 101 would create a new qualified mortgage (QM) compliance option for mortgages that depositories with less than $10 billion in assets originate and hold in portfolio. To be eligible, the lender would have to consider and document a borrower's debts, incomes, and other financial resources, and the loan would have to satisfy certain product-feature requirements.

Analysis

Title XIV of the Dodd-Frank Act established the ability-to-repay (ATR) requirement to address problematic market practices and policy failures that some policymakers believe fueled the housing bubble that precipitated the financial crisis. Under the ATR requirement, a lender must determine based on documented and verified information that, at the time a mortgage is made, the borrower has the ability to repay the loan. Lenders that fail to comply with the ATR rule could be subject to legal liability, such as the payment of certain statutory damages.7

The CFPB issued regulations in January 2013 implementing the ATR requirement. A lender can comply with the ATR requirement in different ways, one of which is by originating a QM. When a lender originates a QM, it is presumed to have complied with the ATR requirement, which consequently reduces the lender's potential legal liability for its residential mortgage lending activities. The definition of a QM, therefore, is important to a lender seeking to minimize the legal risk of its residential mortgage lending activities, specifically its compliance with the statutory ATR requirement.

The Dodd-Frank Act provides a general definition of a QM, but also authorizes CFPB to issue "regulations that revise, add to, or subtract from" the general statutory definition.8 The CFPB-issued QM regulations establish a Standard QM that meets all of the underwriting and product-feature requirements outlined in the Dodd-Frank Act. However, the QM regulations also establish several additional categories of QMs, one of which is the Small Creditor Portfolio QM, which provide lenders the same presumption of compliance with the ATR requirement as the Standard QM. Compared to the Standard QM compliance option, the Small Creditor Portfolio QM has less prescriptive underwriting requirements. It is intended to reduce the regulatory burden of the ATR requirement for certain small lenders.

A mortgage can qualify as a Small Creditor Portfolio QM if three broad sets of criteria are satisfied.9 First, the loan must be held in the originating lender's portfolio for at least three years (subject to several exceptions). Second, the loan must be held by a small creditor, which is defined as a lender that originated 2,000 or fewer mortgages in the previous year and has less than $2 billion in assets. Third, the loan must meet the underwriting and product-feature requirements for a Standard QM except for the debt-to-income ratio.

Some argue that the QM definition has led to an unnecessary constriction of credit and has been unduly burdensome for lenders. In particular, critics argue that not all of the lender and underwriting requirements included in the Small Creditor Portfolio QM are essential to ensuring that a lender will verify a borrower's ability to repay, and instead argue that holding the loan in portfolio is sufficient to encourage thorough underwriting.10

By keeping the loan in portfolio, lenders have added incentive to consider whether the borrower will be able to repay the loan. Keeping the loan in portfolio means that the lender retains the default risk and could be exposed to losses if the borrower does not repay. This retained risk, the argument goes, would encourage small creditors to provide additional scrutiny during the underwriting process, even in the absence of a legal requirement to do so. The expanded portfolio option would, according to supporters, spur lenders to offer more mortgages and it would reduce the burden associated with the more prescriptive underwriting standards of the existing QM options. The less prescriptive standards could most benefit creditworthy borrowers with atypical financial situations, such as self-employed individuals or seasonal employees, who may have a difficult time conforming to the existing standards.

As summarized in Table 1, S. 2155 would create a new compliance option for lenders who keep a mortgage in portfolio in addition to the existing Small Creditor Portfolio QM. Compared to the CFPB's Small Creditor Portfolio QM, S. 2155 would allow larger lenders to use the portfolio compliance option (raising the asset threshold from $2 billion to $10 billion and eliminating the origination limits) but would limit the new option to insured depositories (banks and credit unions) rather than for both depository and nondepository lenders. The portfolio option under S. 2155 would have more restrictive portfolio requirements, requiring lenders to hold the loan in portfolio for the life of the loan (with certain exceptions) rather than for just three years. S. 2155 would have more relaxed loan criteria, however. Lenders would have to comply with some product-feature restrictions, but those restrictions would be less stringent than under the current compliance option. In addition, S. 2155 would relax underwriting criteria, requiring lenders to consider and document a borrower's debts, incomes, and other financial resources in accordance with less prescriptive guidance than is currently required.

Table 1. Comparison of S. 2155 to the CFPB's Small Creditor Portfolio QM

|

CFPB's Small Creditor Portfolio QM |

||

|

Portfolio Requirements |

Mortgage must be held in portfolio for three years. It may be transferred to another small lender and retain QM status. |

Mortgage must be held in portfolio by the originator. It may be transferred and retain QM status under certain limited circumstances. |

|

Lender Restrictions |

Limited to small lenders (depositories and nondepositories) with less than $2 billion in assets and fewer than 2,000 originations a year (excluding those held in portfolio). |

Limited to small insured depositories (banks and credit unions) with less than $10 billion in assets. |

|

Loan Criteria |

Loan must satisfy the underwriting and product feature requirements of the Standard QM Option, with the exception of the Standard QM Option's DTI requirement. |

Loan must satisfy fewer product-feature restrictions and less prescriptive underwriting guidance than the CFPB's Small Creditor Portfolio QM. |

Source: Table created by the Congressional Research Service.

Notes: "QM" = qualified mortgage. "DTI" = debt-to-income ratio. "CFPB Small Creditor Portfolio QM" refers to compliance option currently available in 12 C.F.R. §1026.43.

Although supporters of the expanded portfolio QM option in S. 2155 argue that the new compliance option would expand credit availability and appropriately align the incentives of the borrower and lender, critics of the proposal counter that the incentives of holding the loan in portfolio are insufficient to protect consumers and that the existing protections in the rule are needed to ensure that the hardships caused by the housing crisis are not repeated.

Section 102—Charitable Tax Deduction for Appraisals

Under current law,11 appraisers who meet certain criteria (such as an appraiser who is not an employee of the mortgage loan originator) are required to be compensated at a rate that is customary and reasonable for appraisal services in the market in which the appraised property is located. During the buildup of the housing bubble and its subsequent bust, house prices rose quickly and then fell steeply in many parts of the country, causing some policymakers to question the accuracy of the appraisals that supported the mortgage loans during the housing bubble, and the independence of the appraisers. The customary-and-reasonable fee requirement in current law is intended to help ensure that appraisers are acting with appropriate independence and not in the interest of the lender, seller, borrower, or other interested party. However, some have argued that the requirement for appraisers to receive a customary and reasonable fee has made it difficult for them to donate their services to certain charitable organizations. Section 102 would allow appraisers to donate their appraisal services to a charitable organization eligible to receive tax-deductible charitable contributions, such as Habitat for Humanity, by clarifying that a donated appraisal service to a charitable organization would not be in violation of the customary-and-reasonable fee requirement.

Section 103—Exemption from Appraisals in Rural Areas

Provision

The Dodd-Frank Act strengthened appraisal requirements after concerns were raised about the role that inaccurate appraisals played in the housing crisis. In recent years, there have been reports of shortages of qualified appraisers, especially in rural areas.12 Section 103 would waive the general requirement for independent home appraisals for federally related mortgages in rural areas where the lender has contacted three state-licensed or state-certified appraisers who could not complete an appraisal in "a reasonable amount of time."13 An originator who makes a loan without an appraisal could sell the mortgage only under certain circumstances, such as bankruptcy.

Section 104—Home Mortgage Disclosure Act Adjustment

Provision

Section 104 would exempt banks and credit unions from certain Home Mortgage and Disclosure Act (P.L. 94-200; HMDA) reporting requirements—generally new requirements implemented by the Dodd-Frank Act—if they originated fewer than 500 closed-end mortgage loans in each of the preceding two years and fewer than 500 open-end lines of credit in each of the preceding two years. HMDA, which was originally enacted in 1975, requires most lenders to report data on their mortgage business so that the data can be used to assist (1) "in determining whether financial institutions are serving the housing needs of their communities"; (2) "public officials in distributing public-sector investments so as to attract private investment to areas where it is needed"; and (3) "in identifying possible discriminatory lending patterns."14 Currently, depository lenders have to comply with the HMDA reporting requirements if they have $44 million or more of assets, originated at least 25 home purchase loans in each of the previous two years, and satisfied other criteria.15 The changes proposed by Section 104 would exempt more depository lenders from certain HMDA requirements.

Section 105—Credit Union Loans for Nonprimary Residences

Provision

Section 105 would exclude from the definition of a member business loan a loan made by a credit union for a single-family home that is not an individual's primary residence.16 Credit unions face certain restrictions on the type and volume of loans that they can originate. One such restriction relates to member business loans. A member business loan "means any loan, line of credit, or letter of credit, the proceeds of which will be used for a commercial, corporate or other business investment property or venture, or agricultural purpose," with some exceptions.17 The aggregate amount of member business loans made by a credit union must be the lesser of 1.75 times the credit union's actual net worth, or 1.75 times the minimum net worth amount required to be well capitalized. A loan for a single-family home that is a primary residence is not considered a member business loan, but a similar loan for a nonprimary residence, such as an investment property or vacation home, is considered a member business loan. Section 105 would modify the definition such that nonprimary residence transactions would be excluded from the member business loan definition.

Section 106— Mortgage Loan Originator Licensing and Registration

Provision

Section 106 would allow certain state-licensed mortgage loan originators (MLOs) who are licensed in one state to temporarily work in another state while waiting licensing approval in the new state. It also would grant MLOs who move from a depository institution (where loan officers do not need to be state licensed) to a nondepository institution (where they do need to be state licensed) a grace period to complete the necessary licensing.

Under the Secure and Fair Enforcement for Mortgage Licensing Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-289; SAFE Act),18 MLOs who work for a bank must register with the National Mortgage Licensing System and Registry (NMLS), and those working for a nonbank mortgage lender must be licensed and registered in their state. Supporters of the original 2008 legislation argued that without registration and licensing, unscrupulous or incompetent MLOs may be able to move from job to job to escape the consequences of their actions. For MLOs at nonbank lenders, the process of becoming licensed and registered in a state can be time intensive, involving criminal background checks and prelicensing education. This may be problematic, in particular for individuals moving (1) from a bank lender to a nonbank lender, or (2) from a nonbank lender in one state to a nonbank lender in another state. To address transition issues, Section 106 would provide grace periods to allow individuals who are transferring positions in the situations mentioned above (and meet other performance criteria, such as not having previously had his or her license revoked or suspended) to become appropriately licensed and registered.

Section 107—Manufactured Homes Retailers

Provision

In response to problems in the mortgage market when the housing bubble burst, the SAFE Act and the Dodd-Frank Act established new requirements for mortgage originators' licensing, registration, compensation, and training, among other practices. A mortgage originator is someone who, among other things, "(i) takes a residential mortgage loan application; (ii) assists a consumer in obtaining or applying to obtain a residential mortgage loan; or (iii) offers or negotiates terms of a residential mortgage loan."19 The current definition used in implementing the regulation excludes employees of manufactured-home retailers under certain circumstances, such as "if they do not take a consumer credit application, offer or negotiate credit terms, or advise a consumer on credit terms."20 Section 107 would expand the exception such that retailers of manufactured homes or their employees would not be considered mortgage originators unless they received more compensation for a sale that included a loan than for a sale that did not include a loan and if they provided certain disclosures about their affiliation to other creditors.

Section 108—Real Property Retrofit Loans

Provision

Section 108 would require that the CFPB issue regulations such that creditors would be required to assess a borrower's ability to repay a home improvement loan that is financed through a property lien and included in real property tax payments.

Some states have encouraged retrofitting homes through Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) financing programs which allow state and local governments to issue bonds and use the funds raised to finance residential, commercial, or industrial energy efficiency and renewable energy projects. The proceeds from PACE bonds are lent to property owners, who use the funds to invest in energy efficiency upgrades or renewable energy property. The loans are added to property tax bills through special assessments and paid off over time. PACE programs offer an alternative to traditional loans and repayments.

Some observers have expressed concerns that PACE loans could lead to mortgage defaults, as PACE loans often have relatively high interest rates compared to home-purchase loans.21 To address this issue, Section 108 would extend consumer protections from the ability-to-repay requirement to PACE loans. A creditor would be required to verify that a borrower has the ability to repay the loan prior to extending the financing.

Section 109—Escrow Requirements Relating to Certain Consumer Credit Transactions

Provision

Section 109 would exempt any loan made by a bank or credit union from certain escrow requirements if the institution has assets of $10 billion or less, originated fewer than 1,000 mortgage loans in the preceding year, and meets certain other criteria.

An escrow account is an account that a "mortgage lender may set up to pay certain recurring property-related expenses ... such as property taxes and homeowner's insurance."22 Maintaining escrow accounts for borrowers is an additional cost to banks and may be especially costly for smaller lenders.

An escrow account is not required by statute for all types of mortgages, but higher-priced mortgage loans have been required to maintain an escrow account for at least one year pursuant to a regulation that was implemented before the Dodd-Frank Act.23 The Dodd-Frank Act, among other things, extended the amount of time an escrow account for a higher-priced mortgage loan must be maintained from one year to five years, although the escrow account can be terminated after five years only if certain conditions are met. It also provided additional disclosure requirements.24

The Dodd-Frank Act gave the CFPB the discretion to exempt from certain escrow requirements lenders operating in rural areas if the lenders satisfied certain conditions.25 The CFPB's escrow rule included exemptions from escrow requirements for lenders that (1) operate in rural or underserved areas; (2) extend 2,000 mortgages or fewer; (3) have less than $2 billion in total assets; and (4) do not escrow for any mortgage they service (with some exceptions).26 Additionally, a lender that satisfies the above criteria must intend to hold the loan in its portfolio to be exempt from the escrow requirement for that loan. Section 109 would expand the exemption such that a bank or credit union also would be exempt from maintaining an escrow account for a mortgage as long as it has assets of $10 billion or less, originated fewer than 1,000 mortgage loans in the preceding year, and met certain other criteria.

Section 110—Waiting Period Requirement for Lower-Rate Mortgage

Provision

The Dodd-Frank Act directed the CFPB to combine mortgage disclosures required under the Truth in Lending Act (P.L. 90-321; TILA) and Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (P.L. 93-533; RESPA) into a TILA-RESPA Integrated Disclosure (TRID) form. On November 20, 2013, the CFPB issued the TRID final rule that would require lenders to use the streamlined disclosure forms. Under current law,27 a borrower must receive the disclosures at least three days before the closing of the mortgage. After receiving their required disclosures, borrowers have in some cases been offered new mortgage terms by their lender, which requires new disclosures and potentially delays their mortgage closing. Section 110 would waive the three-day waiting period between a consumer receiving a mortgage disclosure and closing on the mortgage if a consumer receives an amended disclosure that results in the consumer receiving a lower mortgage interest rate.

Section 110 would also express the sense of Congress that the CFPB should provide additional guidance on certain aspects of the final rule, such as whether lenders receive a safe harbor from liability if they use model disclosures published by the CFPB that do not reflect regulatory changes issued after the model forms were published.

Regulatory Relief for Community Banks

Title II of S. 2155 is focused on providing regulatory relief to community banks. Although small banks qualify for various exemptions from certain regulations, whether the regulations have been appropriately tailored is the subject of debate. Certain provisions of Title II would change existing asset thresholds or create new ones at which banks and other depositories are exempt from regulation or otherwise qualify for reduced regulatory obligations.

Background

The term community bank typically refers to a small bank focused on a traditional commercial bank business of taking deposits and making loans, and in so doing meeting the financial needs of a particular community. Although conceptually size does not necessarily have to be a determining factor, community banks are nevertheless often identified as such based on having a small asset size. No consensus exists on where asset thresholds should be set, and some observers doubt the effectiveness of size-based measures in identifying community banks.28

Community banks differ from large institutions in a number of ways besides size that arguably could result in their being subject to certain regulations that are unduly burdensome—meaning the benefit of the regulation does not justify the cost. Community banks are likely to be more concentrated in core commercial bank businesses of making loans and taking deposits and less involved in other activities like securities trading or holding derivatives. Community banks also tend to operate within a smaller geographic area. Also, these banks are generally more likely to practice relationship lending, wherein loan officers and other bank employees have a longer-standing and perhaps more personal relationship with borrowers.29

Due in part to these characteristics, proponents of community banks assert that these banks are particularly important credit sources to local communities and otherwise underserved groups, as big banks may be unwilling to meet the credit needs of a small market of which they have little direct knowledge. If this is the case, imposing burdens on small banks that potentially restrict the amount of credit they make available could have a cost for these groups. In addition, relative to large banks, small banks individually pose less of a systemic risk to the broader financial system, and are likely to have fewer employees and resources to dedicate to regulatory compliance.30 Arguably, this means regulation aimed at systemic stability might produce little benefit at a high cost when applied to these banks.31

Thus, one rationale for easing the regulatory burden for community banks would be that regulation intended to increase systemic stability need not be applied to such banks. Sometimes the argument is extended to assert that because small banks did not cause the 2007-2009 crisis and pose less systemic risk, they need not be subject to new regulations.

Another potential rationale for easing regulations on small banks would be if there are economies of scale to regulatory compliance costs, meaning that as banks become bigger, their costs do not rise as quickly as asset size. From a cost-benefit perspective, if regulatory compliance costs are subject to economies of scale, then the balance of costs and benefits of a particular regulation will depend on the size of the bank. Although regulatory compliance costs are likely to rise with size, those costs as a percentage of overall costs or revenues are likely to fall. In particular, as regulatory complexity increases, compliance may become relatively more costly for small firms.32 Empirical evidence on whether compliance costs are subject to economies of scale is mixed.33 Some argue for reducing the regulatory burden on small banks on the grounds that they provide greater access to credit or offer credit at lower prices than large banks for certain groups of borrowers. These arguments tend to emphasize potential market niches small banks occupy that larger banks may be unwilling to fill.34

Other observers assert that the regulatory burden facing small banks is appropriate, citing the special regulatory consideration already given to minimizing small banks' regulatory burden. For example, during the rulemaking process, bank regulators are required to consider the effect of rules on small banks.35 In addition, they note that many regulations already include an exemption for small banks or are tailored to reduce the cost for small banks to comply. Supervision is also structured to put less of a burden on small banks than larger banks, such as by requiring less frequent bank examinations for certain small banks.36 Furthermore, they counter that although small institutions were not a major cause of the past crisis, they did play a prominent role in the savings and loan crisis of the late 1980s, a systemic event that cost taxpayers $124 billion, according to one analysis.37 Also, they note that systemic risk is only one of the goals of regulation, along with prudential regulation and consumer protection, and argue that the failure of hundreds of banks during the crisis illustrates that precrisis prudential regulation for small banks was not stringent enough.38

Provisions in S. 2155 and Selected Analysis

This section reviews eight provisions in Title II that would amend various laws that affect depositories, including banks, federal savings associations, and credit unions. Although some provisions would relax certain regulations for all banks, Title II provisions are generally aimed at providing regulatory relief to institutions under certain asset thresholds. Several sections amend prudential regulation rules, including minimum capital requirements and the Volcker Rule, whereas others are designed to reduce supervisory requirements by decreasing exam frequency and reporting requirements for small banks. Certain sections in Title II are related to public housing, insurance, national securities exchanges, and the National Credit Union Administration and are described in the "Miscellaneous Proposals in S. 2155" section.

Section 201—Community Bank Leverage Ratio

Provision

Section 201 directs regulators to develop a Community Bank Leverage Ratio (CBLR) and set a threshold ratio of between 8% and 10% capital to unweighted assets, compared to a current leverage ratio requirement of 5%, to be considered well capitalized. If a bank with less than $10 billion in assets maintains a CBLR above that threshold, it will be considered to have met all other leverage and risk-based capital requirements. Banking regulators may determine that a bank with under $10 billion in assets is not eligible to be exempt from existing capital requirements based on its risk profile.

Analysis

Capital—defined by the bill as tangible equity (e.g., ownership shares)39—gives a bank the ability to absorb losses without failing, and regulators set minimum amounts a bank must hold. These capital requirements are expressed as capital ratio requirements—ratios of a bank's assets and capital. The ratios are generally one of two main types— a risk-weighted capital ratio or a leverage ratio. Risk-weighted ratios assign a risk weight—a number based on the riskiness of the asset that the asset value is multiplied by—to account for the fact that some assets are more likely to lose value than others. Riskier assets receive a higher risk weight, which requires banks to hold more capital—to better enable them to absorb losses—to meet the ratio requirement.40 In contrast, leverage ratios treat all assets the same, requiring banks to hold the same amount of capital against the asset regardless of how risky each asset is.

Whether multiple risk-based capital ratios should be replaced with a single leverage ratio is subject to debate. Some observers argue that it is important to have both risk-weighted ratios and a leverage ratio because the two complement each other. Riskier assets generally offer a greater rate of return to compensate the investor for bearing more risk. Without risk weighting, banks would have an incentive to hold riskier assets because the same amount of capital would be required to be held against risky and safe assets. Therefore, a leverage ratio alone—even if set at higher levels—may not fully account for a bank's riskiness because a bank with a high concentration of very risky assets could have a similar ratio to a bank with a high concentration of very safe assets.41

However, others assert the use of risk-weighted ratios should be optional, provided a high leverage ratio is maintained.42 Risk weights assigned to particular classes of assets could potentially be an inaccurate estimation of some assets' true risk, especially because they cannot be adjusted as quickly as asset risk might change. Banks may have an incentive to overly invest in assets with risk weights that are set too low (they would receive the high potential rate of return of a risky asset, but have to hold only enough capital to protect against losses of a safe asset), or inversely to underinvest in assets with risk weights that are set too high. Some observers believe that the risk weights in place prior to the financial crisis were poorly calibrated and "encouraged financial firms to crowd into" risky assets, exacerbating the downturn.43 For example, banks held highly rated mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) before the crisis, in part because those assets offered a higher rate of return than other assets with the same risk weight. MBSs then suffered unexpectedly large losses during the crisis.

Some critics of the current requirements are especially opposed to their application to small banks. They argue that the risk-weighted system involves "needless complexity" and is an example of regulator micromanagement.44 Furthermore, they say, that complexity could benefit the largest banks that have the resources to absorb the added regulatory cost compared to small banks that could find compliance costs relatively more burdensome. Thus, they contend that a simpler system should be implemented for small banks to avoid giving large banks a competitive advantage over them.

Section 202—Allowing More Banks to Accept Reciprocal Deposits

Provision

Section 202 would make reciprocal deposits—deposits that two banks place with each other in equal amounts—exempt from the prohibitions against taking brokered deposits faced by banks that are not well capitalized (i.e., those that may hold enough capital to meet the minimum requirements, but not by the required margins to be classified as well capitalized), subject to certain limitations.

Analysis

Certain deposits at banks are not placed there by individuals or companies utilizing the safekeeping, check writing, and money transfer services the banks provide. Instead, brokered deposits are placed by a third-party broker that places clients' savings in accounts paying higher interest rates. Regulators consider these deposits less stable, because brokers are more willing to withdraw them and move them to another bank than individuals and companies who face higher switching costs and inconvenience when switching banks (e.g., filling out and submitting new direct deposit forms to one's employer, getting new checks, and changing automatic bill payment information). Due to these characteristics, regulators prohibit not-well-capitalized banks from accepting brokered deposits in order to limit potential losses to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) in the event the bank fails.

Section 202 would allow certain not-well-capitalized banks to accept a particular type of brokered deposit called reciprocal deposits, an arrangement between two banks in which each bank places a portion of its own customers' deposits with the other bank. Generally, the purpose of this transaction is to ensure that large accounts stay under the $250,000-per-account deposit insurance limit, with any amount in excess of the limit placed in a separate account at another bank. Like other brokered deposits, reciprocal deposits are funding held by a bank that does not have a relationship with the underlying depositors. However, reciprocal deposits differ from other brokered deposits in that if reciprocal deposits are withdrawn from a bank, the bank receives its own deposits back and thus may better maintain its funding.

Section 203 and 204—Changes to the Volcker Rule

Provision

Section 203 would create an exemption from prohibitions on propriety trading—owning and trading securities for the bank's own portfolio with the aim of profiting from price changes—and relationships with certain investment funds for banks with (1) less than $10 billion in assets, and (2) trading assets and trading liabilities less than 5% of total assets. Currently all banks are subject to these prohibitions pursuant to Section 619 of the Dodd-Frank Act, often referred to as the "Volcker Rule."45 In addition to Section 203's exemption for small banks, Section 204 eases certain Volcker Rule restrictions on all bank entities, regardless of size, related to sharing a name with hedge funds and private equity funds they organize.

Analysis

The Volcker Rule generally prohibits banking entities from engaging in proprietary trading or sponsoring a hedge fund or private equity fund. Proponents argue that proprietary trading would add further risk to the inherently risky business of commercial banking. Furthermore, they assert that other types of institutions are very active in proprietary trading and better suited for it, so bank involvement in these markets is unnecessary for the financial system.46 Finally, proponents assert moral hazard is problematic for banks in these risky activities. Because deposits—an important source of bank funding—are insured by the government, a bank could potentially take on excessive risk without concern about losing this funding. Thus, support for the Volcker Rule has often been posed as preventing banks from "gambling" in securities markets with taxpayer-backed deposits.47

Some observers doubt the necessity and the effectiveness of the Volcker Rule in general. They assert that proprietary trading at commercial banks did not play a role in the financial crisis, noting that issues that played a direct role in the crisis—including failures of large investment banks and insurers, and losses on loans held by commercial banks—would not have been prevented by the rule.48 In addition, although the activities prohibited under the Volcker Rule pose risks, it is not clear whether they pose greater risks to bank solvency and financial stability than "traditional" banking activities, such as mortgage lending. Taking on additional risks in different markets potentially could diversify a bank's risk profile, making it less likely to fail.49 Some contend the rule poses practical supervisory problems. The rule includes exceptions for when bank trading is deemed appropriate—such as when a bank is hedging against risks and market-making—and differentiating among these motives creates regulatory complexity and compliance costs that could affect bank trading behavior.50

In addition to the broad debate over the necessity and efficacy of the Volcker Rule, whether small banks should be subjected to the rule is also a debated issue. Proponents of the rule contend that the vast majority of community banks do not face compliance obligations under the rule, and so do not face an excessive burden by being subject to it. They argue that those community banks that are subject to compliance obligations can comply simply by having clear policies and procedures in place that can be reviewed during the normal examination process. In addition, they assert the small number of community banks that are engaged in complex trading should have the expertise to comply with the Volcker Rule.51

Others argue that the act of evaluating the Volcker Rule to ensure banks' compliance is burdensome in and of itself. They support a community bank exemption so that community banks and supervisors would not have to dedicate resources to complying with and enforcing a regulation whose rationale is unlikely to apply to smaller banks.52

Section 205—Financial Reporting Requirements for Small Banks

Provision

Section 205 would direct the federal banking agencies to issue regulations allowing banks with assets under $5 billion to face reduced reporting requirements for the first and third quarterly reports of the year. Currently, all banks must submit a report of condition and income to the federal bank agencies at the end of every financial quarter of the year, sometimes referred to as a "call report."53 Completing the call report involves entering numerous values into forms or "schedules" in order to provide the regulator with a detailed accounting of many aspects of each bank's income, expenses, and balance sheet. Section 205 directs the regulators to shorten or simplify the reports banks with assets under $5 billion would file in the first and third quarter.

Section 206—Allowing Thrifts to Opt-In to National Bank Regulatory Regime

Provision

Section 206 would create a mechanism for federal savings associations (or "thrifts") with under $15 billion in assets to opt out of their current regulatory regime and enter the national bank regulatory regime without having to go through the process of changing their charter. An institution that makes loans and takes deposits can have one of several types of charters—including a national bank charter and federal savings association charter, among others—each of which subjects the institutions to regulations that can differ in certain ways.54 Currently, if an institution wants to switch from one regime to another, it would have to change its charter.

Analysis

Historically, thrifts were intended to be institutions focused on residential home mortgage lending, and as such they are subject to regulatory limitations on how much of other types of lending they can do. Certain thrifts may want to expand their lending in other business lines, but be unable to do so because of these limitations. Currently, if a thrift wanted to avoid those limitations, it could convert its charter to a national bank charter, but such a conversion could potentially be costly.55 Section 206 would offer an alternative to avoid lending limitations without having to change charters.

Section 207—Small Bank Holding Company Policy Statement Threshold

Provision

Section 207 would raise the asset threshold in the Federal Reserve Small Bank Holding Company (BHC) and Small Saving and Loan Holding Company Policy Statement from $1 billion to $3 billion in total assets. In this statement, the Federal Reserve permits BHCs under $1 billion in assets to take on more debt in order to complete a merger (provided they meet certain other requirements concerning nonbank activities, off-balance-sheet exposures, and debt and equities outstanding) than would be allowed for a larger BHC.56 In addition, Section 171 of the Dodd-Frank Act (sometimes referred to as the "Collins Amendment") exempts BHCs subject to this policy statement from the requirement that banking organizations meet the same capital requirements at the holding company level that depository subsidiaries face.57 The significance of the Collins Amendment arguably depends on the extent to which a BHC has activities in nonbank subsidiaries, and many small banks do not have substantial activities in nonbank subsidiaries.

Section 210—Frequency of Examination for Small Banks

Provision

Section 210 would raise the asset threshold below which banks can become eligible for an 18-month examination cycle instead of a 12-month cycle from $1 billion to $3 billion. Generally, federal bank regulators must conduct an on-site examination of the banks they oversee at least once in each 12-month period. However, if a bank has less than $1 billion in assets and meets certain criteria related to capital adequacy and scores received on previous examinations, then it can be examined only once every 18 months.58 Raising this threshold would allow more banks to be subject to less frequent examination.

Credit Reporting and Consumer Protections

Title III is intended to address various consumer protection challenges facing the credit reporting industry. Credit reporting accuracy, which may affect consumers' access to financial products or employment opportunities and be adversely affected by fraud and identity theft, has been a long-standing congressional policy issue. In light of the Equifax breach announced in September 2017, Congress has increased its interest in consumer data protection and security measures. A provision in Title III is intended to help protect a consumer's credit report from being used fraudulently. In addition, other provisions exclude certain types of information about veteran medical debt and student loan debt from being included in credit reports.

Background

The credit reporting industry collects and subsequently provides information to companies about behavior when consumers conduct various financial transactions. A credit report typically includes information related to a consumer's identity (such as name, address, and Social Security number), existing or recent credit transactions (including credit card accounts, mortgages, and other forms of credit), public record information (such as court judgments, tax liens, or bankruptcies), and credit inquiries made about the consumer.

Credit reports are prepared by credit reporting agencies (CRAs). The three largest CRAs—Equifax, TransUnion, and Experian—are the most well-known, but they are not the only CRAs. Approximately 400 smaller CRAs either are regional or specialize in collecting specific types of information or information for specific industries, such as information related to payday loans, checking accounts, or utilities.

Companies use credit reports to determine whether consumers have engaged in behaviors that could be costly or beneficial to the companies. For example, lenders rely upon credit reports and scoring systems to determine the likelihood that prospective borrowers will repay mortgage and other consumer loans. Insured depository institutions (i.e., banks and credit unions) rely on consumer data service providers to determine whether to make checking accounts or loans available to individuals. Insurance companies use consumer data to determine what insurance products to make available and to set policy premiums.59 Employers may use consumer data information to screen prospective employees to determine, for example, the likelihood of fraudulent behavior. In short, numerous firms rely upon consumer data to identify and evaluate the risks associated with entering into financial relationships or transactions with consumers.

Much of what is thought of as the business of credit reporting is regulated through the Fair Credit Reporting Act (P.L. 91-508; FCRA).60 The FCRA requires "that consumer reporting agencies adopt reasonable procedures for meeting the needs of commerce for consumer credit, personnel, insurance, and other information in a manner which is fair and equitable to the consumer, with regard to the confidentiality, accuracy, relevancy, and proper utilization of such information."61 The FCRA establishes consumers' rights in relation to their credit reports, as well as permissible uses of credit reports. For example, the FCRA requires that consumers be told when their information from a CRA has been used after an adverse action (generally a denial of a loan) has occurred, and disclosure of that information must be made free of charge.62 Consumers have a right to one free credit report every year from each of the three largest nationwide credit reporting providers in the absence of an adverse action. Consumers have the right to dispute inaccurate or incomplete information in their report. The CRAs must investigate and correct, usually within 30 days. The FCRA also imposes certain responsibilities on those who collect, furnish, and use the information contained in consumers' credit reports.

Although the FCRA originally delegated rulemaking and enforcement authority to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the Dodd-Frank Act transferred that authority to the CFPB. The CFPB coordinates enforcement efforts with the FTC's enforcements under the Federal Trade Commission Act.63 Since 2012, the CFPB has subjected the "larger participants" in the consumer reporting market to supervision.64 Previously, CRAs were not actively supervised for FCRA compliance on an ongoing basis.

Cybersecurity threats have raised concerns about the oversight of CRAs for data protection. CRAs are subject to the data protection requirements of Section 501(b) of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (P.L. 106-102; GLBA), which requires the federal financial institution regulators to

establish appropriate standards for the financial institutions subject to their jurisdiction relating to administrative, technical, and physical safeguard—(1) to insure the security and confidentiality of customer records and information; (2) to protect against any anticipated threats or hazards to the security or integrity of such records; and (3) to protect against unauthorized access or use of such records or information which could result in substantial harm or inconvenience to any customer.65

As the "federal functional regulator" of CRAs and other nonbank financial institutions, the FTC has promulgated regulations implementing this requirement and subjecting CRAs to its provisions.66 The FTC has authority, under GLBA, to enforce this regulation with respect to the CRAs through its authority under the Federal Trade Commission Act. The FTC, however, has little ex ante supervisory or enforcement authority, making it difficult to prevent an incident from occurring and instead often relying on enforcement after the fact. As mentioned above, the CFPB does have supervisory authority over the CRAs, but that authority appears to be limited. The CFPB has asserted that Dodd-Frank "excluded financial institutions' information security safeguards under GLBA Section 501(b) from the CFPB's rulemaking, examination, and enforcement authority."67

How consumers' personal information is used and protected is a debated subject. The Equifax breach highlighted the importance of this question, as Equifax has estimated that sensitive information for 145.5 million U.S. consumers was potentially compromised.68 One possible response to these issues is to strengthen consumer protections through the FCRA in order to assist consumers after their information may have been breached (rather than modifying standards to GLBA that could reduce the probability of a breach occurring). As discussed below, this is the approach proposed by S. 2155.

Provisions and Selected Analysis

Section 301—Fraud Alerts and Credit Report Security Freezes

Provisions

Section 301 would amend the FCRA to require credit bureaus to provide fraud alerts for consumer files for at least one year (up from 90 days) when notified by an individual who believes he or she has been or may become a victim of fraud or identity theft. It also provides consumers the right to place (and remove) a security freeze on their credit reports free of charge. In addition, Section 301 would create new protections for the credit reports of minors.

A fraud alert is the inclusion in an individual's report, at the request of the individual, of a notice that the individual has reason to believe they might be the victim of fraud or identity theft. Generally, when a lender receives a credit report on a prospective borrower that includes a fraud alert, the lender must take reasonable steps to verify the identity of the prospective borrower, thus making it more difficult for a fraudster or identity thief to take out loans using the victim's identity. Currently, when an individual requests a fraud alert, the CRAs are required to include the alert in the credit report for 90 days, unless the individual asks for its removal sooner. Section 301 would increase this period to one year.

A security freeze can be placed on an individual's credit report at the request of the individual (or in the case of a minor, at the request of an authorized representative), and generally prohibits the CRAs from disclosing the contents of the credit report for the purposes of new extensions of credit. If a consumer puts a security freeze on his or her credit report, it would make it harder to fraudulently open new credit lines using that consumer's identity.

Analysis

By lengthening the time fraud alerts stay on credit reports and by allowing consumers to place security freezes on their credit reports, Section 301 would give consumers the ability to make it more difficult for identity thieves to get credit using a victim's identity. Reducing the prevalence of erroneous information appearing on credit reports as a result of fraud would reduce the occurrence of defrauded consumers being unfairly denied credit. However, these protections can create some potential costs for lenders and consumers. While a fraud alert is active, the increased verification requirements could potentially increase costs for the lender. A security freeze restricts the use of credit report information in a credit transaction, reducing the information available to lenders and possibly reducing the consumer's access to credit. Although requesting a fraud alert or credit freeze be turned off or "lifted" during a period when a consumer expects to apply for new credit is not especially difficult, doing so is an additional step facing consumers seeking credit and requires some time and attention.69

Section 301 also is related to broader debates over the availability, use, and control of personal financial information. Information that financial institutions and service providers have about consumers allows those firms to make better assessments of the consumers' needs and creditworthiness. Credit reports that contain accurate and complete information may improve the efficiency of consumer credit markets, potentially reducing the cost of consumer credit and the frequency of loan default while also increasing the availability of credit. However, as availability of personal financial information increases, it raises questions about what control individuals have over their own personal, sensitive financial information, particularly in cases in which firms use the information to make adverse decisions against an individual and in which an individual's information is in some way compromised as in the case of fraud. By requiring CRAs to place security freezes at the request of consumers and lengthening the time fraud alerts placed by consumers stay on their reports, Section 301 would give greater control to individuals over how and when their credit reports are used.

Section 302—Certain Medical Debt in Veterans' Credit Reports

Provisions

Section 302 would amend the FCRA to mandate that certain information related to medical debt incurred by a veteran be excluded from the veteran's credit report. Medical debt could not be included in the credit report until one year had passed from when the medical service was provided. The CRAs have already implemented a six-month delay on reporting medical debt for all individuals, so Section 302 would give veterans an additional six months before their medical debts are reported. In addition, Section 302 would require that any information related to medical debt that had been characterized as delinquent, charged off, or in collection be removed once the debt was fully paid or settled. Finally, Section 302 establishes a dispute process for veterans wherein a CRA must remove information related to a debt if the veterans notifies and provides documentation to a CRA showing that the Department of Veterans Affairs is in the process of making payment.

Section 307—Certain Student Loan Debt in Credit Reports

Provisions

Section 307 would amend the FCRA to allow a consumer to request that information related to a default on a qualified private student loan be removed from a credit report if the borrower satisfies the requirements of a loan rehabilitation program offered by a private lender (with the approval of prudential regulators).

Borrowers who default on some federal student loan programs (defined as not having made a payment in more than 270 days70) have a one-time loan rehabilitation option.71 If the defaulted borrower makes nine on-time monthly payments during a period of 10 consecutive months, the loan would be considered rehabilitated.72 The borrower's credit report would then be updated to show that the loan is no longer in default, although the information pertaining to the late payments that led up to the rehabilitation generally would still remain on the report for seven years.73 Students who default on private loans do not necessarily have a similar rehabilitation option.74 Section 307 does not require banks to offer rehabilitations, and each bank would offer them only if the rehabilitations are beneficial to the bank in light of various business, accounting, and regulatory considerations. However, if a financial institution does choose to offer a rehabilitation program—after getting permission from its federal bank regulator—and the consumer completes the terms of the program, Section 307 would allow for the exclusion of default information related to the rehabilitated loan from the consumer's credit report.

Regulatory Relief for Large Banks

Title IV is intended to provide regulatory relief to certain large banks. Generally, there is widespread agreement that the largest, most complex financial institutions that could pose a risk to the stability of the financial system were one to fail or become distressed should be regulated differently than other institutions. However, identifying which institutions fit this description and how their regulatory treatment should differ are subjects of debate.

Background

The 2007-2009 financial crisis highlighted the problem of "too big to fail" (TBTF) financial institutions—the concept that the failure of a large financial firm could trigger financial instability, which in several cases prompted extraordinary federal assistance to prevent their failure. In addition to fairness issues, economic theory suggests that expectations that a firm will not be allowed to fail create moral hazard—if the creditors and counterparties of a TBTF firm believe that the government will protect them from losses, they have less incentive to monitor the firm's riskiness because they are shielded from the negative consequences of those risks.

Enhanced prudential regulation is one pillar of the policy response to addressing financial stability and ending TBTF. Under this regime, the Federal Reserve is required to apply a number of safety and soundness requirements to large banks that are more stringent than those applied to smaller banks. Enhanced regulation is tailored, with the largest banks facing more stringent regulatory requirements than medium-sized and smaller banks. Specifically, organizations are divided into the following three tiers that determine which enhanced regulations they are subject to:

- 1. about 38 U.S. bank holding companies or the U.S. operations of foreign banks with more than $50 billion in assets;

- 2. a subset of 15 advanced approaches banks with $250 billion or more in assets or $10 billion or more in foreign exposure;75 and

- 3. a further subset of globally systemically important banks (G-SIBs), designated as such based on a bank's cross-jurisdictional activity, size, interconnectedness, substitutability, and complexity. There are currently 8 G-SIBs headquartered in the United States out of 30 G-SIBs worldwide.76

Title I of the Dodd-Frank Act created a new enhanced prudential regulatory regime that applies to all banks with more than $50 billion in assets (unless noted below):

- Stress tests and capital planning ensure banks hold enough capital to survive a crisis.

- Living wills provide a plan to safely wind down a failing bank.

- Liquidity requirements ensure that banks are sufficiently liquid if they lose access to funding markets. These liquidity requirements are being implemented through three rules: (1) a 2014 final rule implementing firm-run liquidity stress tests,77 (2) a 2014 final rule implementing a Fed-run liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) to ensure that banks hold sufficient "high quality liquid assets,"78 and (3) a 2016 proposed rule that would implement the Fed-run net stable funding ratio (NSFR) to ensure that banks have adequate sources of stable funding.79

- Counterparty limits restrict the bank's exposure to counterparty default through a single counterparty credit limit (SCCL) and credit exposure reports.

- Risk management standards require publicly traded companies with more than $10 billion in assets to have risk committees on their boards, and banks with more than $50 billion in assets to have chief risk officers.

- Financial stability requirements mandate that a number of regulatory interventions can be taken only if a bank poses a threat to financial stability. For example, the Fed may limit a firm's mergers and acquisitions, restrict specific products it offers, terminate or limit specific activities, or require it to divest assets.80

Most of these requirements are already in place, but some proposed rules have not yet been finalized. Some of these requirements have been tailored so that more stringent regulatory or compliance requirements were applied to advanced approaches banks or G-SIBs. For example, versions of the LCR, NSFR, and SCCL applied to advanced approaches banks are more stringent than those applied to banks with more than $50 billion in assets that are not advanced approaches banks. The SCCL as proposed also includes a third, most stringent requirement that applies only to G-SIBs.

Pursuant to Basel III, banking regulators have implemented additional prudential regulations that apply only to large banks. For these requirements, $50 billion in assets was not used as a threshold. The following requirement applies to advanced approaches banks, with a more stringent version applied to G-SIBs, and would be affected by a provision in S. 2155:

- Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR). Leverage ratios determine how much capital banks must hold relative to their assets without adjusting for the riskiness of their assets. Advanced approaches banks must meet a 3% SLR, which includes off-balance-sheet exposures. G-SIBs are required to meet an SLR of 5% at the holding company level in order to pay all discretionary bonuses and capital distributions and 6% at the depository subsidiary level to be considered well capitalized as of 2018.81

Large banks are also subject to other Basel III regulations that would not be directly affected by S. 2155. The countercyclical capital buffer requires advanced approaches banks to hold more capital than other banks when regulators believe that financial conditions make the risk of losses abnormally high. It is currently set at zero (as it has been since it was introduced), but can be modified over the business cycle.82 The G-SIB capital surcharge requires G-SIBs to hold relatively more capital than other banks in the form of a common equity surcharge of at least 1% and as high as 4.5% to "reflect the greater risks that they pose to the financial system."83 G-SIBs are also required to hold a minimum amount of capital and long-term debt at the holding company level to meet total loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC) requirements. To further the policy goal of preventing taxpayer bailouts of large financial firms, TLAC requirements are intended to increase the likelihood that equity- and debt-holders can absorb losses and be "bailed in" in the event of the firm's insolvency.84

Provisions and Selected Analysis

Section 401—Enhanced Prudential Regulation and the $50 Billion Threshold

Provision

Section 401 of S. 2155 would automatically exempt banks with assets between $50 billion and $100 billion from enhanced regulation, except for the risk committee requirements. Banks with between $100 billion and $250 billion in assets would still be subject to supervisory stress tests, and the Fed would have discretion to apply other individual enhanced prudential provisions (except those included in the "Financial Stability" bullet above) to these banks if it would promote financial stability or the institutions' safety and soundness. Banks that have been designated as domestic G-SIBs and banks with more than $250 billion in assets would remain subject to enhanced regulation. To illustrate how specific firms might be affected by S. 2155, Table 2 matches the criteria found in the three categories created by the bill to firms' U.S. assets as of June 30, 2017. The $250 billion threshold matches one of the two thresholds used to identify advanced approaches banks (it does not include the foreign exposure threshold).

Currently, foreign banking organizations that have more than $50 billion in global assets and operate in the United States are also potentially subject to enhanced regulatory regime requirements. S. 2155 would replace that threshold with $250 billion in global assets (with Fed discretion to impose individual standards between $100 billion and $250 billion). In practice, the implementing regulations have imposed significantly lower requirements on foreign banks with less than $50 billion in U.S. nonbranch assets compared to those with more than $50 billion in U.S. nonbranch assets. Foreign banks with more than $50 billion in U.S. nonbranch assets must form intermediate holding companies (IHCs) for their U.S. operations, which are essentially treated as equivalent to U.S. banks for purposes of applicability of the enhanced regime and bank regulation more generally. For these reasons, the U.S. assets of foreign IHCs are presented in Table 2 to be consistent with the current implementation of most enhanced prudential regulatory requirements, but implementation of S. 2155 would remain at the Fed's discretion. All of the IHCs in Table 2 belong to a foreign parent with more than $250 billion in global assets.85

Table 2. BHCs and IHCs with Over $50 Billion in U.S. Assets

(as of June 30, 2017; dollar amounts in billions)

|

Institution Name |

U.S. Assets |

|

Banks With Over $250 Billion in U.S. Assets or G-SIBs |

|

|

JPMorgan Chase & Co. |

$2,563 |

|

Bank of America Corporation |

$2,256 |

|

Wells Fargo & Company |

$1,931 |

|

Citigroup Inc. |

$1,864 |

|

Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. |

$907 |

|

Morgan Stanley |

$841 |

|

U.S. Bancorp |

$464 |

|

PNC Financial Services Group, Inc. |

$372 |

|

Bank of New York Mellon Corporation |

$355 |

|

Capital One Financial Corporation |

$351 |

|

TD Group U.S. Holdings LLCa |

$349 |

|

HSBC North America Holdings Inc.a |

$308 |

|

State Street Corporation |

$238 |

|

Banks With $100 Billion to $250 Billion in U.S. Assets |

|

|

BB&T Corporation |

$221 |

|

Credit Suisse Holdings (USA), Inc.a |

$215 |

|

Suntrust Banks, Inc. |

$207 |

|

DB USA Corporationa |

$191 |

|

Barclays US LLCa |

$179 |

|

American Express Company |

$167 |

|

Ally Financial Inc. |

$164 |

|

Citizens Financial Group, Inc. |

$152 |

|

MUFG Americas Holdings Corporationa |

$151 |

|

RBC USA Holdco Corporationa |

$147 |

|

UBS Americas Holding LLCa |

$143 |

|

Fifth Third Bancorp |

$141 |

|

BNP Paribas USA, Inc.a |

$140 |

|

Keycorp |

$136 |

|

Santander Holdings USA, Inc.a |

$135 |

|

BMO Financial Corp. |

$130 |

|

Northern Trust Corporation |

$126 |

|

Regions Financial Corporation |

$125 |

|

M&T Bank Corporation |

$121 |

|

Huntington Bancshares Incorporated |

$101 |

|

Banks With $50 Billion to $100 Billion in U.S. Assets |

|

|

Discover Financial Services |

$94 |

|

BBVA Compass Bancshares, Inc.a |

$87 |

|

Comerica Incorporated |

$72 |

|

Zions Bancorporation |

$65 |

|

CIT Group Inc. |

$50 |

S. 2155 would make tailoring of the regime mandatory instead of discretionary. For banks with less than $100 billion in assets, the changes would be effective immediately. For banks with more than $100 billion in assets, the changes would be effective in 18 months.

The bill would also make changes to specific enhanced prudential requirements. Section 401 would give regulators the discretion to reduce the number of scenarios used in stress tests and to reduce the frequency of certain stress tests for banks with less than $250 billion in assets. It would increase the asset thresholds for company-run stress tests from $10 billion to $250 billion and for a mandatory risk committee at publicly traded banks from $10 billion to $50 billion. The bill would make the implementation of credit exposure report requirements discretionary for the Federal Reserve instead of mandatory. To date, the Fed has not finalized a rule implementing credit exposure reports.

Analysis

Supporters and opponents of S. 2155 generally agree that enhanced prudential regulation should apply to systemically important banks, but disagree about which banks could pose systemic risk. There has been widespread support for raising the $50 billion threshold, including from certain prominent regulators, but no consensus on how it should be modified.86 In particular, critics of the $50 billion threshold distinguish between regional banks (which tend to be at the lower end of the asset range and, it is claimed, have a traditional banking business model comparable to community banks) and Wall Street banks (a term applied to the largest, most complex organizations that tend to have significant nonbank financial activities).87 If there are economies of scale to regulatory compliance, the regulatory burden of enhanced regulation is disproportionately higher for the banks with closer to $50 billion in assets. Thus, if the bill reduces the number of banks that are subject to enhanced regulation but are not systemically important, a significant reduction in cost could be achieved without a significant increase in systemic risk.

Definitively identifying banks that are systemically important is not easily accomplished, in part because potential causes and mechanisms through which a bank could disrupt the financial system and spread distress are numerous and not well understood in all cases. In addition, there is not an exact correlation between size and traditional banking activities.

Many economists believe that the economic problem of "too big to fail" is really a problem of firms that are too complex or too interdependent to fail. Size correlates with complexity and interdependence, but not perfectly. Size is a much simpler and more transparent metric than complexity or interdependence, however. As a practical matter, if size is well correlated with systemic importance, a dollar threshold could serve as a good proxy that is inexpensive and easy to administer. Designating banks on a case-by-case basis could raise similar issues that have occurred in the designation of nonbanks, such as the slow pace of designations; difficulty in finding objective, consensus definitions of what constitutes systemic importance; and legal challenges to overturn their designation.

S. 2155 attempts to maximize the benefits and minimize the problems by using both approaches—an automatic designation for banks with assets of more than $250 billion and a case-by-case application of standards for banks with assets between $100 billion and $250 billion. This approach can mitigate the drawbacks inherent in both approaches, but cannot eliminate them. Any dollar threshold still potentially includes banks that do not pose systemic risk with assets above that threshold. Compared to a dollar threshold, any case-by-case application of standards would be more expensive, time-consuming, and subjective, and could potentially create opportunities for legal challenges.

Aside from the effects on financial stability, reducing the number of banks subject to enhanced regulation also reduces second-order benefits, such as protecting taxpayers against FDIC insurance losses. It could also worsen the "too big to fail" problem if market participants perceive the banks subject to enhanced regulation as officially too big to fail. This could lead to greater moral hazard—if the creditors and counterparties of a TBTF firm believe that the government will protect them from losses, they have less incentive to monitor the firm's riskiness because they are shielded from the negative consequences of those risks. One rationale for (1) setting the asset threshold low and (2) subjecting any bank above it to enhanced prudential regulation automatically is that this method would reduce the likelihood that banks in the regime would be viewed as having a de facto TBTF designation.