Overview1

During its 114th session, Congress faced numerous international trade and finance policy issues. These issues included approval of legislation granting time-limited U.S. Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) to the President. TPA provides expedited congressional procedures for considering legislation to implement U.S. trade agreements that advance U.S. trade negotiating objectives and meet specific notification and consultative requirements. Congress also approved legislation to reauthorize the Export-Import Bank (Ex-Im Bank), the Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) program, U.S. trade preference programs for Africa and other developing countries, and the commercial operations of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), as well as legislation to enhance trade enforcement by Customs and approve governance reforms at the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Additionally, Congress continued oversight of ongoing U.S. trade agreements and negotiations, U.S. trading relationships with major economies, and U.S. economic sanctions against Iran, Cuba, North Korea, Russia, and other countries.

The future direction of U.S. trade policy and international economic issues continue to be active areas of interest in the 115th session of Congress. Notably, U.S. trade policy and trade agreements received significant attention during the 2016 presidential election campaign. Since taking office, President Trump has withdrawn the United States as a signatory to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) free trade agreement among 12 Asia-Pacific nations; notified Congress of his intent to renegotiate NAFTA with Canada and Mexico; and is reviewing other current U.S. free trade agreements (FTA) for possible revision, including the U.S.-South Korea FTA (KORUS). The Trump Administration has also indicated a preference for bilateral trade negotiations, including with the United Kingdom (UK), and Japan and other participants in TPP. There appears to be little interest so far in continuing negations on an FTA with the European Union.

Trade enforcement issues and the broader impact of trade and the trade deficit on the U.S. economy are receiving increased attention. Recent actions by the Trump Administration include a review of the trade deficit and the renewed use of certain trade laws, such as Section 232, designed to investigate the national security impact of specific imports. Other pertinent issues include the future direction of U.S.-China trade relations and a new bilateral economic dialogue, ongoing trade negotiations at the World Trade Organization (WTO) and on services (taking place outside of the WTO), and other FTA discussions that do not include the United States.

International trade and finance issues are important to Congress because they can affect the overall health of the U.S. economy and specific sectors, the success of U.S. businesses and workers, and Americans' standard of living. They also have implications for U.S. geopolitical interests. Conversely, geopolitical tensions, risks, and opportunities can have major impacts on international trade and finance. These issues are complex and at times controversial, and developments in the global economy often make policy deliberation more challenging.

Congress is in a unique position to address these issues, particularly given its constitutional authority for legislating and overseeing international trade and financial policy. This report provides a brief overview of some of the trade and finance issues that may be of interest or continuing attention of the 115th Congress. A list of CRS products covering these issues and containing relevant citations is provided in the Appendix.

The United States in the Global Economy

Since the end of World War II, the United States has served as the chief architect of an open and rules-based international economic order that has been characterized by trade expansion and growing economic integration. Some see this global economic order fragmenting and becoming less governable. The U.S. leadership role is being challenged both from abroad by rising economic powers such as China and from within the United States by groups that have grown skeptical of the benefits of the unique U.S. position in the global economy. For some, these changes to the international economic order may signal the end of America's dominance without a clear successor.

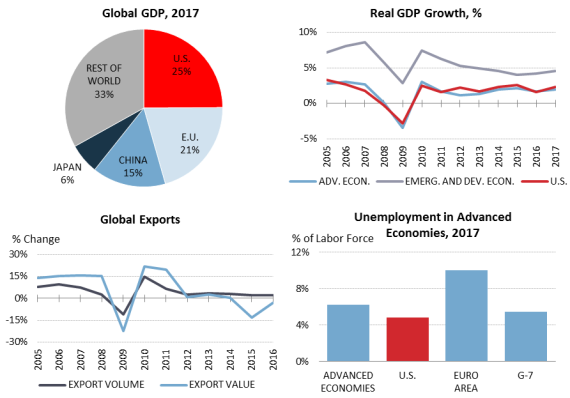

The global economy is continuing to recover in 2017 from the 2008-2009 financial crisis and deep economic recession. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) projects that global annual growth will increase to nearly 3.5% in 2017 from a projected global growth rate of 3.2% in 2016.2 The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) forecasts a global growth forecast of 3.3%, based on the United States and other developed economies increasing government deficit spending to support infrastructure development, while avoiding restrictive trade measures.3 The lack of new infrastructure spending by the United States has reduced the IMF forecast of U.S. growth from 2.3% in 2017 to 2.1%, while developed economies as a whole are projected to grow by 2.0%. Emerging market and developing economies are projected by the IMF to grow by 4.6%, up from 4.3% in 2016, while China's economy is projected to grow at 6.7%, the same rate of growth as 2016.

Additional factors raise uncertainties about the strength and pace of the projected recovery in the rate of economic growth. Savings and investment relative to GDP, which serve as building blocks for future growth, continue to lag behind pre-financial 2008 crisis levels in the advanced economies. Similarly, global trade continues to perform at lower levels and is significantly slower compared to historical levels. Lingering high rates of unemployment and non-performing loans are constraining economic growth in many Western European economies. Higher sustained rates of economic growth remain elusive in Japan, Canada, and parts of Europe, and especially in the UK where the implementation of Brexit (the vote in favor of exiting the European Union) is causing economic uncertainty over the future UK-EU economic and trade relationship, among other concerns.

Emerging markets (EMs) as a group are expected to face reduced levels of vulnerabilities to their economies due to a modest recovery in global trade and more stable exchange rates, inflation, commodity prices, and equity markets, which should aid in improving the rate of growth. Growth rates are projected to recover somewhat in Russia and Brazil, due to more stable oil and commodity prices, but increased uncertainty over political and policy direction could constrain the rate of growth in Brazil. Additionally, China has faced a slower rate of economic growth as it attempts to navigate toward a more sustainable growth model that is more focused on boosting innovation and private consumption. In Venezuela, a major economic and financial crisis has surfaced. These and other developments, such as grown tension and concern over North Korea's nuclear arms policies, contribute to uncertainties that potentially impact global financial markets and raise concerns over the pace of business investment that could dampen prospects for longer-term gains in productivity and sustained higher rates of economic growth.

|

|

Source: Created by CRS from International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, April 2017 and World Trade Organization Trade Statistics, accessed August 2017. Note: 2017 data is forecasted. |

Over the long term, developed and developing economies are struggling to find the right policy mix to address low growth, low inflation, and low levels of productivity growth, referred to as structural stagnation by some. Developed and developing economies are experiencing declining or flat birth rates, which portend a smaller work force in the future and lower potential rates of economic growth. Aging work forces, a demographic unfolding everywhere but in Africa and the Middle East, may also act to restrain economic growth. Under similar challenging conditions, nations in the past have turned to broad, multinational trade liberalization agreements to stimulate economic growth through improvements in productivity by removing market-distorting barriers.

Even with a slower pace of economic recovery, the U.S. economy remains a relative bright spot in terms of the global economic outlook, which could help sustain its position as a main driver of global economic growth. The United States accounts for 24.5% of global gross domestic product (GDP) and 9.1% of global trade. Although still recovering from the worst recession in 8 decades, overall U.S. economic conditions have improved with the unemployment rate below 4.5% in mid-2017 from a high of 10% in 2009, and the IMF projects GDP growth will be 2.0% in 2017, up from 1.7% in 2016.4 The stabilization in oil prices is affecting the U.S. economy. Relatively low energy prices are expected to raise consumers' real incomes, improve the competitive position of some industries, and stabilize employment and output in the energy sector.

Despite improvements in the economy as a whole, average U.S. household incomes have not fully recovered from the 1999-2000 and 2008-2010 economic recessions. The United States, similar to other developed economies, has experienced widening disparity in incomes that is fueling domestically-focused political movements and a backlash against globalization. The Trump Administration announced shortly after taking office that it would focus its efforts on tax reform and infrastructure spending to restore economic growth, but an effort to revamp health care dominated the congressional calendar. At the same time, President Trump has criticized U.S. trade agreements as a main cause of U.S. economic challenges and has launched certain trade investigations and reviews that are viewed by some experts as potentially leading to growing trade restrictions in the United States. The Trump Administration has also made reduction of U.S. bilateral trade deficits a priority issue. Since their peak in 2006, however, current account imbalances, as a share of world GDP, have fallen significantly, particularly the deficit in the United States and the surpluses in China and Japan.

For many economists, concerns over a slowdown in global trade and the role the United States may play in supporting global growth as a major importer may overshadow potential concerns over global imbalances. The Euro and Japanese yen have experienced periods of volatility since the Brexit referendum vote during the summer of 2016. Some currencies remain at levels below the pre-Brexit level, including the Chinese renminbi, the Brazilian real, and the Russian ruble. In addition, the Mexican peso depreciated sharply in international foreign markets as the dollar strengthened in 2016. Volatile currency and equity markets combined with uncertainties over global growth prospects and rates of inflation that remain below the target levels of a number of central banks have complicated somewhat the efforts of the U.S. Federal Reserve to take additional steps to raise U.S. interest rates to stabilize financial markets. In addition, other major economies in Europe and Japan have attempted to pursue more expansionary monetary policies. Reduced levels of uncertainty in global financial markets have reduced upward pressure on the dollar, as investors have been less prone to seek safe haven currencies and dollar-denominated investments. Through the first half of 2017, for instance, the dollar depreciated about 5% against the currencies of its major trading partners.

The Role of Congress in International Trade and Finance

The U.S. Constitution assigns authority over foreign trade to Congress. Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution gives Congress the power to "regulate Commerce with foreign Nations" and to "lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts, and Excises." For roughly the first 150 years of the United States, Congress exercised its power to regulate foreign trade by setting tariff rates on all imported products. Congressional trade debates in the 19th century often pitted Members from northern manufacturing regions, who benefitted from high tariffs, against those from largely southern raw material exporting regions, who gained from and advocated for low tariffs.

A major shift in U.S. trade policy occurred after Congress passed the highly protective "Smoot-Hawley" Tariff Act of 1930, which significantly raised U.S. tariff levels and led U.S. trading partners to respond in kind. As a result, world trade declined rapidly, exacerbating the impact of the Great Depression. Since the passage of the Tariff Act of 1930, Congress has delegated certain trade authority to the executive branch. First, Congress enacted the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934, which authorized the President to enter into reciprocal agreements to reduce tariffs within congressionally pre-approved levels, and to implement the new tariffs by proclamation without additional legislation. Congress renewed this authority periodically until the 1960s. Subsequently, Congress enacted the Trade Act of 1974, aimed at opening markets and establishing nondiscriminatory international trade norms for nontariff barriers as well. Because changes in nontariff barriers in reciprocal bilateral, regional, and multilateral trade agreements may involve amending U.S. law, the agreements require congressional approval and implementing legislation. Congress has renewed or amended the 1974 Act five times, which includes granting "fast-track" trade negotiating authority. Since 2002, "fast track" has been known as trade promotion authority (TPA). Third, Congress has granted the President various authorities to address unfair trade practices and impose tariffs in certain circumstances for trade, national security and foreign policy purposes.

Congress also exercises trade policy authority through the enactment of laws authorizing trade programs and governing trade policy generally, as well as oversight of the implementation of trade policies, programs, and agreements. These include such areas as U.S. trade agreement negotiations, tariffs and nontariff barriers, trade remedy laws, import and export policies, economic sanctions, and the trade policy functions of the federal government.

Additionally, Congress has an important role in international investment and finance policy. It has authority over bilateral investment treaties (BITs) through Senate ratification, and the level of U.S. financial commitments to the multilateral development banks (MDBs), including the World Bank, and to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). It also authorizes the activities of such agencies as the Export-Import Bank (Ex-Im Bank) and the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC). Congress has oversight responsibilities over these institutions, as well as the Federal Reserve and the Department of the Treasury, whose activities affect international capital flows. Congress also closely monitors developments in international financial markets that could affect the U.S. economy.

Policy Issues for Congress

Trade Promotion Authority (TPA)5

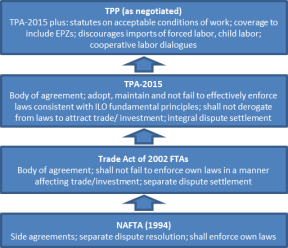

Legislation to renew Trade Promotion Authority (TPA)—the Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-26)—was signed by President Obama on June 29, 2015, after months of debate and passage by both houses of Congress. TPA allows implementing bills for specific trade agreements to be considered under expedited legislative procedures—limited debate, no amendments, and an up or down vote—provided the President observes certain statutory obligations in negotiating trade agreements. These obligations include adhering to congressionally-defined U.S. trade policy negotiating objectives, as well as congressional notification and consultation requirements before, during, and after the completion of the negotiation process.

The primary purpose of TPA is to preserve the constitutional role of Congress with respect to consideration of implementing legislation for trade agreements that require changes in domestic law, which includes tariffs, while also bolstering the negotiating credibility of the executive branch by ensuring that trade agreements will not be changed once concluded. Since the authority was first enacted in the Trade Act of 1974, Congress has renewed or amended TPA five times (1979, 1984, 1988, 2002, and 2015). The latest grant of authority expires on July 1, 2021, provided that the President requests its extension by April 1, 2018, and neither chamber introduces and passes an extension disapproval resolution by July 1, 2018. If legislation is introduced in Congress in the future to implement the results of negotiations to renegotiate or modernize the North American Free Trade Agreement, it may be eligible to receive expedited consideration under TPA if concluded prior to the expiration of TPA.

The World Trade Organization (WTO)6

The WTO is an international organization that administers the trade rules and agreements negotiated by 164 participating members to eliminate barriers and create non-discriminatory rules and principles to govern trade. It also serves as a forum for dispute settlement resolution and trade liberalization negotiations. The United States was a major force behind the establishment of the WTO on January 1, 1995, and the new rules and trade liberalization agreements that occurred as a result of the Uruguay Round of multilateral trade negotiations (1986-1994). The WTO succeeded the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which was established in 1947.

The most recent round of multilateral trade negotiations, the WTO Doha Round, began in November 2001, but concluded with no clear path forward after the 10th Ministerial Conference in December 2015.Trade ministers and their senior representatives in Nairobi did reach consensus on a limited set of deliverables related to the agriculture priorities of least developed countries, but the lack of a clear mandate for the Doha Round reflects continued wide division among WTO members.

The WTO's future as an effective multilateral trade negotiating organization for broad based multilateral trade liberalization remains in question. The deadlock in negotiations is largely due to differences between leading emerging-market economies, such as India, China and Brazil, developing economies, and advanced countries. Most developing countries want to continue to link the broad spectrum of agricultural and non-agricultural issues under the Doha Round and have been reluctant to lower their tariffs on industrial goods. They maintain that unless all issues are addressed in a single package, issues important to developing countries will be ignored. Conversely, the developed economies have pushed for change in the negotiating dynamics, arguing that the WTO needs to address new issues, such as digital trade and investment, especially given the growth of major emerging markets, such as China and India. WTO members are working on potential deliverables in the lead up to the 11th ministerial conference in Buenos Aires, Argentina in December 2017.

The WTO appears to moving in a direction of negotiating sectoral and issue-focused agreements on a plurilateral basis (subsets of WTO members rather than among all WTO members). The Nairobi Declaration underscored the importance of a multilateral rules-based trading system with regional and plurilateral agreements as a complement to, not a substitute for, the multilateral forum. Work to build on the current WTO agreements outside the scope of the Doha Round continues, including through sectoral or plurilateral agreements that involve only a subset of WTO members, for example, on services (see text box).

|

Sectoral and Plurilateral Agreements and Negotiations

|

U.S. Bilateral and Regional Trade Agreements

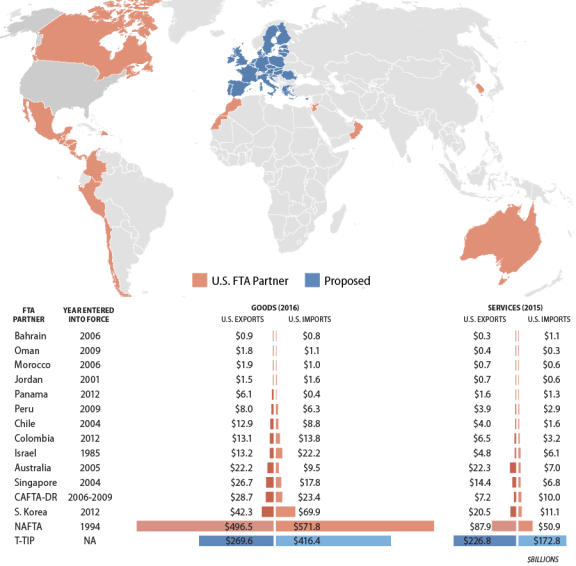

In addition to the WTO, the United States has worked to reduce and eliminate barriers to trade and create non-discriminatory rules and principles to govern trade through plurilateral and bilateral agreements. It has concluded 14 free trade agreements (FTAs) with 20 countries since 1985, when the first U.S. bilateral FTA was concluded with Israel.

The Trump Administration has signaled a shift on U.S. bilateral and regional trade agreements. President Trump withdrew the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a FTA negotiated during the Obama Administration between the United States and 11 other countries in the Asia-Pacific region. The Trump Administration is also planning a renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), a FTA between the United States, Canada, and Mexico. Other trade negotiations launched during the Obama Administration, including for a FTA between the United States and the European Union (EU) on a potential Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP), and among 23 WTO members on a potential Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA), have been dormant to date under the Trump Administration. President Trump has expressed interest in negotiating bilateral trade agreements, including a FTA with the United Kingdom, Japan, and other TPP partners.

|

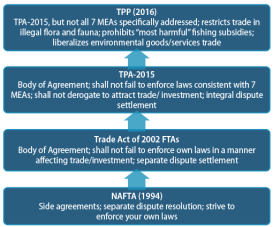

U.S. Trade Agreement Basics U.S. trade agreements generally are negotiated

|

|

|

Source: Created by CRS using U.S. International Trade Commission and the Bureau of Economic Analysis data. |

|

North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)7 Renegotiation

NAFTA, a comprehensive FTA among the United States, Canada, and Mexico, entered into force on January 1, 1994. NAFTA initiated a new generation of trade agreements, influencing subsequent negotiations in areas such as market access, rules of origin, intellectual property rights (IPR), foreign investment, dispute resolution, worker rights, and environmental protection.

On May 18, 2017, the Trump Administration sent a 90-day notification to Congress of its intent to begin talks with Canada and Mexico to modernize NAFTA, as required by the 2015 Trade Promotion Authority.8 On July 17, 2017, United States Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer released a summary of the Administration's negotiating objectives.9 Under TPA requirements, negotiations can begin no earlier than August 16, 2017.

NAFTA is more than 20 years old and renegotiation may provide opportunities to address issues not currently covered in NAFTA and to modernize other parts of the agreement. Potential topics of renegotiation could include rules of origin, agriculture, services trade, digital trade, intellectual property rights (IPR) protection, government procurement, and stronger and more enforceable labor and environmental provisions.

The Trump Administration's desire to renegotiate NAFTA, along with the rising number of bilateral and regional trade agreements globally and the growing presence of China in Latin America have numerous implications for U.S. trade policy with its NAFTA partners. Many trade policy experts and economists give credit to NAFTA and other FTAs for expanding trade and economic linkages among countries, creating more efficient production processes, increasing the availability of lower-priced consumer goods, and improving living standards and working conditions. Other proponents contend that FTAs have political dimensions that create positive ties among member countries and improve democratic governance. However, some policymakers, labor groups and consumer advocacy groups argue that NAFTA has had a negative effect on the U.S. economy. They strongly oppose NAFTA and other FTAs. They maintain that trade agreements result in outsourcing, lower wages, and job dislocation.

Both proponents and critics of NAFTA agree that the three countries could consider the strengths and shortcomings of the agreement as they look to the future of NAFTA and a potential modernization. Policy issues could include strengthening NAFTA provisions in areas such as worker rights, the environment, intellectual property rights, services trade, and digital trade; considering the ramifications if Canada and Mexico move forward with a potential FTA with other TPP partners; evaluating the possibility of trade retaliation by Canada or Mexico if the United States considers changing or withdrawing from NAFTA; considering the establishment of a border infrastructure plan, including more investment in infrastructure to make border crossings more efficient; promoting research and development to enhance the global competitiveness of North American industries; enhancing understanding of regional supply chain networks; and/or creating more efforts to lessen income differentials within the region.

Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)10

|

TPP Fast Facts Negotiations concluded: 10/5/2015. Agreement text released: 11/5/2015. Date signed: 2/4/2016. U.S. Withdrawal: 1/24/17. Status: 11 remaining countries may continue with accord. 11 countries participating: Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, Vietnam. Value of total 2015 U.S. goods and services trade with TPP countries: $1.8 trillion. |

On January 24, 2017, President Trump withdrew the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The TPP had been a proposed free trade agreement (FTA) among 12 countries in the Asia-Pacific region, including the United States. The Obama Administration cast TPP as a comprehensive and high standard agreement with economic and strategic significance for the United States. Some U.S. stakeholders argue the TPP withdrawal coupled with ongoing FTA negotiations that do not involve the United States may negatively affect U.S. export competitiveness and leadership in establishing new trade disciplines. Had it been ratified by the United States, TPP would have been the largest U.S. FTA by trade flows to date, as it included three of the five largest U.S. trade partners—Canada, Mexico, and Japan. The Trump Administration has expressed interest in negotiating bilateral FTAs with Japan and other TPP parties.

The remaining 11 parties may move forward to ratify the TPP without U.S. participation (TPP-11). This group has met on several occasions since the U.S. withdrawal, and reportedly will meet to decide whether to continue with the deal later this year. Japan is a leading proponent of keeping discussion of the TPP alive and minimizing potential changes to the agreement, which is in many ways similar to existing U.S. FTAs. This may be a strategy by Japan to keep open the possibility of future U.S. accession. The Japanese Diet approved the TPP in late 2016, and the New Zealand Parliament followed suit in May 2017. Other countries have expressed various levels of enthusiasm for continuing the agreement.

The economic significance of a TPP-11 agreement would be smaller without U.S. participation. However, it would provide those countries liberalized trade with Japan, the world's third largest economy. Japan has existing bilateral FTAs with several countries in the region, including Australia, and exports to Japan from these countries currently enjoy a price advantage in the Japanese market relative to U.S. exports. If the TPP-11 is ratified, major agricultural exporters in particular, including Canada, Australia, and New Zealand will benefit from a further tariff advantage in the Japanese market over U.S. competitors. Japan also recently announced an agreement "in principle" with the European Union, which, if finalized and enacted, would similarly give advantage to EU products in the Japanese market and vice-versa.

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), an Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN)-led negotiation, may also take on increased significance in the wake of TPP. The RCEP encompasses ASEAN members (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam), as well as China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, India, and New Zealand, but not the United States. The remaining TPP countries may also seek to solidify their trading relationship with China, whether within RCEP or bilaterally, as China is already the largest trading partner for most TPP countries. Proponents of TPP often characterized it as a vehicle to establish U.S. favored trade disciplines in the Asia-Pacific region, maintaining U.S. economic and strategic leadership in the region. Many in Congress have expressed strong support for certain aspects of the TPP, such as its new commitments on digital trade and state-owned enterprises. Trump Administration officials, including Ambassador Lighthizer, have noted that aspects of TPP may influence U.S. negotiating positions in future FTA talks, including in the renegotiation of NAFTA.

Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP)11

|

T-TIP Basics U.S.-EU High-Level Working Group report: Called for United States and EU to negotiate FTA, 2/11/13. Date negotiations started: 7/8/2013. Number of negotiating rounds: 15 rounds through October 2016 under the Obama Administration. Status: Negotiations currently dormant under the Trump Administration. U.S.-EU goods and services trade in 2016: $1.1 trillion (22% of U.S. global trade). U.S.-EU investment in 2016: $5.2 trillion (57% of U.S. world investment stock on historical-cost basis). Note: Data for EU-28. |

The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP) is a potential "comprehensive and high-standard" free trade agreement (FTA) between the United States and the European Union (EU). These economies are each other's largest overall trade and investment partner. T-TIP aims to liberalize U.S.-EU trade and investment and address tariff and non-tariff barriers on goods, services, and agriculture. It also aims to set globally relevant rules and disciplines to support economic growth and multilateral trade liberalization. T-TIP negotiations began in 2013. With the 15th and latest negotiating round in October 2016, the two sides had consolidated texts in many areas. Yet, they face unresolved complex and sensitive issues on numerous fronts, raising questions about whether sufficient political momentum exists to overcome differences. Presently, negotiations are on pause as both sides evaluate T-TIP's status.12

T-TIP's outlook is uncertain. On the U.S. side, support for T-TIP remains high among some Members of Congress. At the same time, making concessions in international trade negotiations remains controversial for others in Congress and with the American public. On one hand, T-TIP's prospects are questionable due to President Trump's preference for bilateral FTA negotiations to leverage U.S. economic strength and target U.S. priorities. The potential for growing U.S.-EU trade frictions in light of the Trump Administration's focus on "unfair" trading practices related to U.S. domestic import competition, such as the Section 232 investigations on steel and aluminum, and the possibility of EU countermeasures depending on the outcome of these and other potential investigations13 could also diminish T-TIP's prospects. On the other hand, the Administration has expressed support for expanding transatlantic trade and possible openness to resuming T-TIP negotiations.14 The Administration also appears to have shifted away from its prior advances to some EU member states to negotiate bilateral FTAs, which was unrealistic given tehir membership in the EU.15

Other uncertainties include the September 2017 national elections in Germany, where public opposition to T-TIP runs high due to concerns over treatment of genetically modified organisms (GMOs), investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS), and data privacy. Another variable is the pending United Kingdom exit from the EU ("Brexit," see next section). In addition, if the agreement "in principle" announced in July 2017 on an EU-Japan FTA leads to a ratified FTA between those two economies, it could accelerate U.S. interest in resuming T-TIP negotiations to ensure U.S. firms' competitiveness in the EU market.16

If T-TIP negotiations resume, potential issues for Congress include the level of priority both sides place on T-TIP, given the U.S. renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the EU's trade negotiations with other countries. If T-TIP negotiations stall indefinitely or terminate, Congress may wish to examine other ways to enhance U.S.-EU trade relations. Congress might also want to address strategic issues regarding U.S. ability to shape international trade norms due to the EU's push to include its approaches on issues such as regulatory cooperation, geographical indications (GIs), data flows, and ISDS in its FTAs with other countries. These issues, which were contentious in prior T-TIP negotiations, could directly conflict with U.S. trade and regulatory objectives.

Brexit and a Potential U.S.-UK Free Trade Agreement (FTA)17

|

U.S.-UK Trade Relations: Fast Answers

|

On June 23, 2016, the United Kingdom (UK) voted in favor of exiting the EU ("Brexit"), presenting oversight and legislative issues about transatlantic trade relations. Trade is equivalent to about 60% of the UK economy, in large part due to reduced trade barriers through the EU's Single Market. At $2.7 trillion, the UK was the EU's second largest economy behind Germany and accounted for about 16% of EU GDP in 2016.18 Brexit confronts U.S. firms operating in the UK and benefiting from UK's access to the Single Market with economic and financial uncertainties.

Brexit's impact on U.S.-UK trade relations depends on a number of variables. These include the UK's negotiated terms of withdrawal from the EU and the UK's future trade relationship with the EU. On March 29, 2017, UK Prime Minister Theresa May triggered the two-year Article 50 process for withdrawal from the EU.19 June 2017 marked the start of the withdrawal negotiations.20 The UK indicates that it will not seek membership in the EU Single Market and instead will seek an "ambitious and comprehensive" FTA with the EU and a new customs agreement.21 Another variable is any redefinition of UK and EU terms of trade in the WTO. The UK is a member of the WTO both on an individual basis and as a part of the EU. However, the UK's commitments to the United States and other WTO members are through the EU's WTO schedules of commitments on tariffs and other areas, and may have to be renegotiated.

The UK is a key U.S. trade and investment partner. The Brexit referendum prompted calls from some Members of Congress and the Trump Administration to launch U.S.-UK FTA negotiations, though some Members have moderated their support with calls to ensure that such negotiations do not constrain promoting broader transatlantic trade relations.22 On January 27, 2017, President Trump and Prime Minister May discussed how the two sides could "lay the groundwork" for a future U.S.-UK FTA.23 In July 2017, the two sides launched a U.S.-UK Trade and Investment Working Group to explore a possible post-Brexit FTA. Early discussions include a focus on ensuring commercial continuity for U.S. and UK businesses during the withdrawal process.24 Some experts view a potential U.S.-UK FTA as more politically feasible than other U.S. FTAs, given similarities in U.S. and UK trade policy approaches and the two countries' "special relationship"; others caution that, even among like-minded trading partners, domestic political interests can complicate trade negotiations.25

Brexit raises questions about other aspects of U.S. trade policy as well. Regarding T-TIP, some argue that the UK's possible absence could complicate the T-TIP negotiations, if resumed, given the UK's traditionally liberalizing role in the EU. Others say that a potential U.S.-UK FTA could add pressure to advance any further T-TIP negotiations. The UK's future status also could affect other U.S. trade policy interests, such as the Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) negotiations (see below).

Trade in International Services Agreement (TiSA)26

|

TiSA Facts

|

TiSA is a potential agreement that would liberalize trade in services among its signatories. The term "services" refers to an expanding range of economic activities, such as construction, retail and wholesale sales, e-commerce, financial services, professional services (such as accounting and legal services), logistics, transportation, tourism, and telecommunications. The impetus for TiSA comes from the lack of progress in the WTO Doha Round on services trade liberalization. Given the impasse in the WTO, a subset of WTO members, led by the United States and Australia, launched informal discussions in early 2012 to explore negotiating a separate agreement focused on trade in services. The United States and the 22 other TiSA participants account for more than 70% of global trade in services.

Negotiations began in April 2013, and 21 rounds of negotiations and intercessional meetings took place through 2016. The Trump Administration has not stated an official position on TiSA, and no negotiations have been scheduled for 2017.

Negotiations on services present unique trade policy issues, such as how to construct trade rules that are applicable across a wide range of varied economic activities. The General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) under the WTO is the only multilateral set of rules on trade in services. GATS came into effect in 1995, and many policy experts have argued that the GATS must be updated and expanded if it is to liberalize services trade effectively. This prospect is diminished given that GATS reform is part of the stalled Doha Round of WTO negotiations.

The TiSA negotiations are of congressional interest given the significance of the services sector in the U.S. economy and TiSA's potential impact on domestic services industries seeking to expand internationally. Services account for almost 78% of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) and for over 82% of U.S. private sector employment.27 They not only function as end-user products by themselves, but they also act as the "lifeblood" of the rest of the economy. For example, transportation services ensure that goods reach customers and financial services provide financing for the manufacture of goods, while e-commerce and cross-border data flows allow customers to download products and companies to manage global supply chains. Services have been an important priority in U.S. trade policy and of global trade in general.

Congress may continue oversight of the TiSA negotiations. Opening services markets globally has been a long-standing U.S. trade negotiating objective. In the 2015 Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) legislation, Congress included specific provisions establishing U.S. trade negotiating objectives on services trade to expand competitive market opportunities and obtain fairer and more open conditions of trade.

U.S.-China Commercial Relations28

Since China embarked upon economic and trade liberalization in 1979, U.S.-Chinese economic ties have grown extensively and total bilateral trade rose from about $2 billion in 1979 to $579 billion in 2016. China was the United States' second-largest trading partner, largest source of imports ($463 billion), and third largest merchandise export market ($116 billion).29 The U.S. merchandise trade deficit with China was $347 billion, by far the largest U.S. bilateral trade imbalance.

China has been one of the fastest growing markets for U.S. exports. From 2006 to 2015, U.S. merchandise exports to China doubled. The U.S.-China Business Council estimates that China is a $400 billion market for U.S. firms when U.S. exports of goods and services to China plus sales by U.S-invested firms in China are counted.30 China's large population, vast infrastructure needs, and rising middle class could make it an even more significant market for U.S. businesses, provided that new economic reforms are implemented and trade and investment barriers are lowered. According to the Rhodium Group, annual Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in the United States rose from $4.6 billion in 2010 to $46.2 billion in 2016.31 China is important to the global supply chain for many U.S. companies, some of which use China as a final point of assembly for their products. Low-cost imports from China help keep U.S. inflation low. China is the world's largest economy and trading country. Its economic conditions and policies have a major impact on the U.S. and global economy, and thus are of interest to Congress.

Despite growing U.S.-Chinese commercial ties, the bilateral relationship is complex and at times contentious. From the U.S. perspective, many trade tensions stem from China's incomplete transition to an open-market economy. While China has significantly liberalized its economic and trade regimes over the past three decades—especially since joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001—it continues to maintain (or has recently imposed) a number of policies that appear to distort trade and FDI flows, which, some Members argue, often undermine U.S. economic interests and cause U.S. job losses in some sectors. The USTR summed up the major challenge to U.S.-China trade relations in its 2015 Report to Congress on China's WTO Compliance as follows: "Many of the problems that arise in the U.S.-China trade and investment relationship can be traced to the Chinese government's interventionist policies and practices and the large role of state-owned enterprises and other national champions in China's economy, which continue to generate significant trade distortions that inevitably give rise to trade frictions."32 Major economic and trade areas of congressional concern are described below. A 2017 American Chamber in China (AmCham China) business climate survey of its member companies found that while a majority of respondents felt optimistic about their investments in China, 81% said that foreign businesses in China were "less welcomed" in China than before, compared to 44% who felt that way in 2014.33

|

China-U.S. FDI U.S.-China FDI flows are relatively small given the high level of bilateral trade, although estimates of such flows differ. The Rhodium Group (RG), a private advisory firm, estimates the stock of China's FDI in the United States through 2015 at $62.9 billion and the stock of U.S. FDI in China at $227.9 billion. RG also estimated that annual Chinese FDI flows to the United States rose from $7.5 billion in 2012 to $15.3 billion in 2015, and that 2016 FDI flows were nearly triple 2015 levels, at $45.6 billion. Some members have raised concerns that some Chinese FDI activities may threaten to harm U.S. economic security and the competitiveness of some industries, and have proposed revising the criteria of how the federal government reviews such investment. The United States has pressed China to reduce FDI restrictions and barriers, including through negotiations for a bilateral investment treaty (BIA). In 2013, China agreed that the BIT would include Chinese commitments to open up various sectors to FDI, based on a "negative list" basis—meaning only sectors specifically listed in the final agreement would be barred from FDI. A BIT was not concluded by the end President Obama's term and the Trump Administration has not indicated if it intends to restart BIT negotiations with China. |

The United States has initiated more WTO dispute settlement cases (21 cases through July 2017) against China than any other WTO member. Recently-brought cases involve Chinese agricultural subsides, export restrictions on certain raw materials, and preferential tax policies for locally-produced aircraft. China has brought 10 WTO cases against the United States, the most recent of which was filed on December 12, 2016, and involves U.S. treatment of China as a non-market economy (NME) for the purposes of applying anti-dumping measures. China contends that the WTO agreement on its accession to the WTO in 2001 contained a provision mandating that all WTO members give it market economy status by December 11, 2016. Most recently, on August 14, 2017, President Trump issued a Presidential Memorandum directing the USTR to determine whether it should launch a Section 301 investigation into China's protection of U.S. IPR and forced technology transfer polices. A Section 301 case against China could have significant implications for bilateral commercial ties, especially if the case is pursued unilaterally and not through the WTO dispute settlement process.

|

Section 301 Sections 301 through 310 of the Trade Act of 1974, as amended, are commonly referred to as "Section 301." It is one of the principal statutory means by which the United States enforces U.S. rights under trade agreements and addresses "unfair" foreign barriers to U.S. exports. Section 301 procedures apply to foreign acts, policies, and practices that the USTR determines either (1) violates, or is inconsistent with, a trade agreement; or (2) is unjustifiable and burdens or restricts U.S. commerce. The measure sets procedures and timetables for actions based on the type of trade barrier(s) addressed. Section 301 cases can be initiated as a result of a petition filed by an interested party with the USTR or self-initiated by the USTR. Once the USTR begins a Section 301 investigation, it must seek a negotiated settlement with the foreign country concerned, either through compensation or an elimination of the particular barrier or practice. For cases involving trade agreements, such as those under the Uruguay Round (UR) agreements in the WTO, the USTR is required to utilize the formal dispute proceedings specified by the agreement. |

Industrial Policies and State Capitalism

The Chinese government continues to play a major role in economic decision-making. For example, at the macroeconomic level, the Chinese government maintains policies that induce households to save a high level of their income, much of which is deposited in state-controlled Chinese banks. This enables the government to provide low-cost financing to Chinese firms, especially SOEs which dominate several economic sectors in China. Fortune's 2016 Global 500 list of the world's largest companies included 103 Chinese firms, 75 of which were classified as being 50% or more owned by the Chinese government. At the microeconomic level, the Chinese government (at the central and local government level) seeks to promote the development of industries deemed critical to the country's future economic development by using various means, such as subsidies, preferential loans, tax exemptions, and access to low-cost land and energy. Many analysts contend that such distortionary policies contribute to overcapacity in several Chinese industrial sectors, such as steel and aluminum. Additionally, the Chinese government imposes numerous restrictions on foreign firms seeking to do business in China, such as discriminatory regulations and standards, uneven enforcement of commercial laws (such as its anti-monopoly laws), FDI barriers and mandates, export restrictions on raw materials, technology transfer requirements imposed on foreign firms, and public procurement rules that give preferences to domestic Chinese firms.

The Chinese government has outlined a number of policies to promote China's transition from a manufacturing center to a major global source of innovation and reducing the country's dependence on foreign technology by promoting "indigenous innovation" and a 2025 "Made in China" plan. In recent years, the Chinese government has enacted new laws on national security, cybersecurity, and counter-terrorism, and has proposed new regulations for banking and insurance, which, under the pretext of protecting national security, appear to impose new restrictions against foreign providers of information and communications products (ICT) and services. For example, some of the provisions describe the need for China to obtain ICT that is "secure and controllable," describe the need for the government to promote indigenous sources of technology, imposes data localization requirements, and contain broad and vague language on an approval process for ICT goods and services.

Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) Protection and Cyber-Theft

American firms cite the lack of effective and consistent protection and enforcement in China of U.S. IPR as one of the largest challenges they face in doing business in China. Although China has significantly improved its IPR protection regime over the past few years, many U.S. industry officials view piracy rates in China as unacceptably high. While the 2017 Amcham China's 2017 business survey found that 95% percent of respondents felt that IPR enforcement had improved over the past five years, 66% said the IPR enforcement of trade secrets was ineffective and 52% said protection of trademarks and brands was ineffective. A May 2013 study by the Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property, a commission co-chaired by Dennis C. Blair, former U.S. Director of National Intelligence, and former U.S. Ambassador to China, Jon Huntsman, estimated that China accounted for up to 80% ($240 billion) of the annual cost to the U.S. economy of global IPR theft ($300 billion).34 The USTR's 2016 report on foreign trade barriers stated that over the past decade, China's Internet restrictions have "posed a significant burden to foreign suppliers," and that eight out of the top 25 most globally visited sites (such as Yahoo, Facebook, YouTube, eBay, Twitter and Amazon) are blocked in China.35 Cyberattacks by Chinese entities against U.S. firms have raised concerns over the potential theft of U.S. IPR, especially trade secrets. A February 2013 report by Mandiant, a U.S. information security company, documented extensive economic cyber espionage by a Chinese unit (designated as "APT1") with alleged links to the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) against 141 firms, covering 20 industries, since 2006.36 On May 19, 2014, the U.S. Department of Justice issued a 31-count indictment against five members of the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) for cyber espionage and other offenses that allegedly targeted five U.S. firms and a labor union for commercial advantage, the first time the federal government initiated such action against state actors.

On April 1, 2015, President Obama issued Executive Order 13964, authorizing certain sanctions against "persons engaging in significant malicious cyber-enabled activates." Shortly before Chinese President Xi's state visit to the United States in September 2015, some press reports indicated that the Obama Administration was considering imposing sanctions against Chinese entities over cyber-theft. After high-level talks between Chinese and U.S. officials on cybersecurity, President Obama and President Xi announced on September 25, 2016 that they reached an agreement. The agreement stated that neither country's government will conduct or knowingly support cyber-enabled theft of intellectual property, including trade secrets or other confidential business information, with the intent of providing competitive advantages to companies or commercial sectors. They also agreed to set up a high-level dialogue mechanism to address cybercrime and to improve two-way communication when cyber-related concerns arise. The U.S.-China High-Level Joint Dialogue on Cybercrime and Related Issues met in December 2015 and June 2016, although it is unclear if the dialogue has produce concrete results.

The Trump Administration's Approach

At their first official meeting as heads of state, President Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping announced the establishment of a "100-day plan on trade" as well as a new high-level forum called the "U.S.-China Comprehensive Economic Dialogue."37 According to U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, "President Trump noted the challenges caused by Chinese government intervention in its economy and raised serious concerns about the impact of China's industrial, agricultural, technology, and cyber policies on U.S. jobs and exports. The President underscored the need for China to take concrete steps to level the playing field for American workers, stressing repeatedly the need for reciprocal market access."

On May 11, 2017, the two sides announced that China would open its markets to U.S. beef, biotechnology products, credit rating services, electronic payment services, and bond underwriting and settlement. The United States agreed to open its markets to Chinese cooked poultry and welcomed Chinese purchases of U.S. liquefied gas. Chinese officials also indicated their support for continuing negotiations for continuing the BIT negotiations, although the Trump Administration did not indicate its position on this proposal. Following the meeting, President Trump in a series of Tweets appeared to indicate that he would link U.S. trade policy towards China with China's willingness to pressure North Korea to curb its nuclear and missile programs.

On July 19, 2017, the two sides held the first session of the CED in Washington, DC, which sought to build on the 100-day action plan through a new one-year action plan on trade and investment, seeking to achieve "a more balanced economic relationship." The outcome of the meeting is unclear as, unlike past high-level meetings, no joint fact sheet was released. The U.S. side issued a short statement that said that "China acknowledged our shared objective to reduce the trade deficit which both sides will work cooperatively to achieve." This led some U.S. observers to claim that the CED was marred with high tensions and disagreements, and failed to produce any meaningful results.38 China, on the other hand issued a four-page document on the "positive outcomes" of the CED, including the broad outline of a one-year plan covering broad economic and trade topics.39 The document also stated that two sides discussed trade in services, steel, aluminum, and high technology.40

President Trump has indicated growing frustration with China over North Korea, especially over the relative lack of economic pressure. China's trade data for January-June 2017 indicate that while its imports from North Korea declined by 24% year on year, its exports rose by 18%. This led President Trump to Tweet on July 29, 2017 that he was "very disappointed with China" and complained that China greatly benefited from trade with the United States but was doing nothing on North Korea. On July 31, 2017, Chinese Vice Commerce Minister Qian Keming's reportedly stated that "North Korea's nuclear issue and the issue of trade between China and the United States are two different issues. They are not related. You cannot speak about them together."41

Looking Ahead

The Trump Administration appears to be taking a harder line against China on trade issues. On March 31, 2017, President Trump issued an executive order requiring the U.S. Department of Commerce and USTR to submit an Omnibus Report on Significant Trade Deficits that focuses on major bilateral merchandise trade imbalances. That report will likely heavily focus on China. The Administration's Section 232 investigations on steel and aluminum imports might result in the imposition of import restrictions against China. Finally, the Administration has made the enforcement and application U.S. anti-dumping and countervailing measures (where Chinese imports have been the largest target) a major priority.42 When President Trump announced and signed his Presidential Memorandum on China's IPR policies on August 14, he said that "this is only the beginning."

Economic Effects of Trade

Trade and trade agreements have wide-ranging effects on the economy, including on economic growth, the distribution of income, and employment gains or losses. For most economists, liberalized trade results in both economic costs and benefits, but they argue the long-run net effect on the economy as a whole is positive. It is argued that the economy as a whole operates more efficiently and grows more rapidly as a result of competition through international trade and investment, and consumers benefit by having available a wider variety of goods and services at varying levels of quality and price than would be possible in an economy closed to international trade. Trade also can have long-term positive dynamic effects on an economy and enhances production and employment. However, the costs and benefits associated with expanding trade and trade agreements do not accrue to the economy at the same speed; costs to the economy in the form of job and firm losses are felt in the initial stages of the agreement, while benefits to the economy accrue over time. According to the World Bank, liberalizing trade and foreign investment have reduced the number of people in the world living in extreme poverty (under $1 per day) by half, or 600 million, over the past 25 years, transforming the global economy.43

Trade and U.S. Jobs44

Trade is one among a number of forces that drive changes in employment, wages, the distribution of income, and ultimately the standard of living in the U.S. economy. Most economists argue that macroeconomic forces within an economy, including technological and demographic changes, are the dominant factors that shape trade and foreign investment relationships and complicate efforts to disentangle the distinct impact that trade has on the economy. Various measures are used to estimate the role and impact of trade in the economy and of trade on employment. One measure developed by the Department of Commerce concludes that exports support, directly and indirectly, 11.7 million jobs in the U.S. economy. According to these estimates, jobs associated with international trade, especially jobs in export-intensive manufacturing industries, earn 18% more on a weighted average basis than comparable jobs in other manufacturing industries.

More open markets globally and other changes have subjected a larger portion of the domestic workforce to international competition. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the effective global labor market quadrupled over the past two decades through the opening of China, India, and the former East European bloc countries.45 In particular, the entry of China into the global economy is an unprecedented development given the size of the Chinese economy and the speed with which it became a major participant in the global economy. Standard economic theory recognizes that some workers and producers in the economy may experience a disproportionate share of the short-term adjustment costs as a result of such economic transformations. Although the attendant adjustment costs for firms and workers are difficult to measure, some estimates suggest they may be significant over the short-run and can entail dislocations for some segments of the labor force, some companies, and some communities. Closed plants can result in depressed commercial and residential property values and lost tax revenues, with effects on local schools, local public infrastructure, and local community viability.46

In a dynamic economy like that of the United States, jobs are constantly being created and replaced as some economic activities expand, while others contract. As part of this process, various industries and sectors evolve at different speeds, reflecting differences in technological advancement, productivity, and efficiency. Those sectors that are the most successful in developing or incorporating new technological advancements usually generate greater economic rewards and are capable of attracting larger amounts of capital and labor. In contrast, those sectors or individual firms that lag behind generally attract less capital and labor and confront ever-increasing competitive challenges. In addition, advances in communications, transportation, and technology have facilitated a global transformation of economic production into sophisticated supply chains that span national borders, defy traditional concepts of trade, and effectively increase the number of firms and workers participating in the global economy. The growth of the digital economy, or the digitization of information, also has enhanced the knowledge economy and information-based trade.

Trade and trade liberalization can have a differential effect on workers and firms in the same industry. Some estimates indicate that the short-run costs to workers who attempt to switch occupations or switch industries in search of new employment opportunities may experience substantial effects. One study concluded that workers who switched jobs as a result of trade liberalization generally experienced a reduction in their wages, particularly in occupations where workers performed routine tasks.47 These negative income effects were especially pronounced in occupations exposed to imports from low-income countries. In contrast, occupations associated with exports experienced a positive relationship between rising incomes and growth in export shares. As a result of the differing impact of trade liberalization on workers and firms, some governments have adopted special safeguards and worker retraining and other social safety net policies to mitigate the potential adverse effects of trade liberalization or address certain trade practices that may cause or threaten to cause injury.

Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA)48

Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) is a group of programs that provide federal assistance to parties that have been adversely affected by foreign trade. Reduced barriers to trade can offer domestic benefits in increased consumer choice and new export markets but trade can also have negative effects among domestic industries that face increased competition. TAA aims to mitigate some of these negative domestic effects. TAA programs are authorized by the Trade Act of 1974, as amended, and were last reauthorized by the Trade Adjustment Assistance Reauthorization Act of 2015 (TAARA; Title IV of P.L. 114-27).

The largest TAA program, TAA for Workers (TAAW), provides federal assistance to workers who have been separated from their jobs because of increases in directly competitive imports or because their jobs moved to a foreign country. The largest components of the TAAW program are (1) funding for career services and training to prepare workers for new occupations and (2) income support for workers who are enrolled in an eligible training program and have exhausted their unemployment compensation. The TAAW program is administered at the federal level by the Department of Labor and FY2017 appropriations were $849 million.

TAA programs are also authorized for firms and farmers that have been adversely affected by international competition. TAA for Firms supports trade-impacted businesses by providing technical assistance in developing business recovery plans and by providing matching funds to implement those plans. TAA for Firms is administered by the Department of Commerce and the FY2017 appropriation was $13 million. The TAA for Farmers program was reauthorized by TAARA, but the program has not received an appropriation since FY2011.

Intellectual Property Rights (IPR)49

|

Examples of IPR Patents protect new innovations and inventions, such as pharmaceutical products, chemical processes, new business technologies, and computer software. Copyrights protect artistic and literary works, such as books, music, and movies. Trademarks protect distinctive commercial names, marks, and symbols. Trade secrets protect confidential business information that is commercially valuable because it is secret, including formulas, manufacturing techniques, and customer lists. Geographical indications (GIs) protect distinctive products from a certain region, applying primarily to agricultural products. |

Intellectual property (IP) is a creation of the mind embodied in physical and digital objects. IPR are legal, private, enforceable rights that governments grant to inventors and artists that generally provide time-limited monopolies to right holders to use, commercialize, and market their creations and prevent others from doing the same without their permission.

IP is a source of comparative advantage of the United States, and IPR infringement has adverse consequences for U.S. commercial, health, safety, and security interests. Protection and enforcement of IPR in the digital environment is of increasing concern, including cyber-theft. At the same time, lawful limitations to IPR, such as exceptions in copyright law for media, research, and teaching (known as "fair use"), also may have benefits.

IPR in Trade Agreements & Negotiations

IPR protection and enforcement has been a long-standing objective in U.S. trade agreement negotiations. The United States generally seeks IP commitments that exceed the minimum standards of the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement), known as "TRIPS-plus." The 2015 Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) incorporated past trade negotiating objectives to ensure that U.S. free trade agreements (FTAs) "reflect a standard of protection similar to that found in U.S. law" ("TRIPS-plus") and to apply existing IPR protection to digital media through adhering to the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) "Internet Treaties." The TPA also contained new objectives on addressing cyber-theft and protecting trade secrets and proprietary information.

Treatment of IPR may be a key issue in the upcoming negotiations on NAFTA.50 The proposed NAFTA renegotiation may include such IPR provisions as

- pharmaceutical patent protections, with measures to protect public health consistent with TRIPS;

- data exclusivity periods for biologics—the United States sought a 12-year period consistent with U.S. law in TPP, while Canada and Mexico provide 8-year and 5-year periods of exclusivity, respectively, for both biologic and chemical compounds.

- copyright protections, penalties for circumventing technological protection measures, safe harbor measures for Internet Service Providers (ISPs), and goals to achieve an appropriate balance between the interests of copyright holders and users (known as "fair use" in the U.S. context);

- enhanced trademark protection and disciplines for geographic indicators (GIs), with the U.S. goal to ensure that widely used geographic terms are available for generic use juxtaposed against expanded GI recognition in the Canada-EU Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA); and

- enhanced enforcement measures, including new criminal penalties for trade secret theft, clarification that criminal penalties apply to infringement in the digital environment, and ex officio authority for customs agents to seize counterfeit and pirated goods.

Although many of these provisions were adopted in the TPP negotiations, it is unclear whether they automatically would be written into a revised NAFTA, given the different negotiating dynamics. In considering any revised NAFTA agreement, Congress could examine whether the IPR outcomes in a possible revised NAFTA outcome are consistent with U.S. trade negotiating objectives in TPA. The T-TIP negotiations, if resumed, present possible areas of congressional oversight, particularly on treatment of GIs, IPR protection and enforcement in the digital environment, and cooperation to address trade secret theft. Additionally, U.S. government actions to enforce foreign trading partners' IPR obligations within the WTO and under existing U.S. FTAs could intensify. Possible oversight issues for Congress include approaches to, as well as prioritization of, potential future U.S. trade enforcement actions in the IPR context.

Other IPR Trade Policy Tools

The United States maintains other trade policy tools to advance IPR goals. These tools may be particularly relevant in addressing U.S. issues with respect to emerging economies, such as China, India, and Brazil, which are not a part of existing U.S. trade agreements or negotiations and present significant IPR challenges.

- Special 301. The United States Trade Representative (USTR) publishes annually a "Special 301" report, pursuant to the Trade Act of 1974, as amended. This report identifies countries that do not offer "adequate and effective" IPR protection, for example for patents and copyrights, and designates them on various "watch lists." The Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-125) required USTR to identify issues in countries' protection of trade secrets in the "Special 301" report. China has been a top country of concern, and continues to be identified on the Special 301 "Priority Watch List" (among other countries, such as India). An August 14, 2017 presidential memorandum directs USTR to determine whether to initiate an investigation of China's IPR practices under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, as amended. Alternatively, Special 301 could be an avenue to pursue such an investigation if the United States designates China as a Special 301 "Priority Foreign Country," a category reserved for the most egregious IPR offenders. Although both Section 301 and Special 301 could result in trade enforcement action, they are distinct remedies in statute (see China section).

- Section 337. The U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC), pursuant to the Tariff Act of 1930, as amended, conducts "Section 337" investigations into allegations that U.S. imports infringe U.S. IP. Based on the investigations, ITC can issue, among other things, orders prohibiting counterfeit and pirated products from entering the United States.

The 115th Congress could examine the effectiveness of Special 301 and Section 337. Given President Trump's expressed intent to focus on trade enforcement, such tools may take on greater prominence.

International Investment

U.S. investment policy has become a focal point of the U.S. trade policy debate, intersecting with questions about economic impact, trade restrictions, national security, and regulatory sovereignty. Congress influences all aspects of these international issues.

The United States is both a major source and recipient of foreign direct investment (FDI). In 2016, the total stock of global FDI was $26.73 trillion, with the United States continuing to have the world's largest cumulative share of FDI on a country basis ($6.39 trillion).51 Global FDI flows decreased slightly (around 2%) to $1.75 trillion. FDI flows to developing economies were especially hard hit, with a decline of 14% to $646 billion. Flows to developed economies increased further, after significant growth in the previous year. Inflows rose by 5% to $1 trillion, with FDI growth in the United States particularly strong over the past year. In 2016, the United States was the largest recipient of inward FDI ($391 billion), followed by the United Kingdom ($254 billion), China ($134 billion), Hong Kong ($108 billion), and the Netherlands ($92 billion).

The U.S. dual position as a leading source and destination for FDI argues that globalization, the spread of economic activity by firms across national borders, has become a prominent feature of the U.S. economy. This means that the United States has important economic, political, and social interests at stake in the development of international policies regarding direct investment. In recent decades, U.S. presidents have issued statements affirming an open U.S. investment policy.52 President Trump has not issued a similar statement, but Trump Administration statements have declared the Administration's openness to global investment.53 Some analysts, however, point to legislative efforts to expand the jurisdiction of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS)54 as a potential harbinger of a more restrictive attitude toward foreign investment in the United States. The Administration's approach to investment issues in the NAFTA renegotiation also may be indicative of any possible changes in the direction of U.S. investment policy.

Foreign Investment and National Security55

The United States has established domestic policies that treat foreign investors no less favorably than U.S. firms, with some exceptions for national security. Under current U.S. law, the President exercises broad discretionary authority over developing and implementing U.S. direct investment policy, including the authority to suspend or block investments that "threaten to impair the national security." At the same time, Congress also is directly involved in formulating the scope and direction of U.S. foreign investment policy. For instance, following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001, some Members questioned the traditional U.S. open door policy for foreign investment and argued for greater consideration of the long-term impact of foreign direct investment on the structure and industrial capacity of the economy, and on the ability of the economy to meet the needs of U.S. defense and security interests. More recently, concerns have been raised by some Members over China's acquisitions of technology-related firms, and new legislation is being contemplated to reform the CIFUS process.

In July 2007, Congress asserted its own role in making and conducting foreign investment policy when it adopted and the President signed the Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007 (P.L. 110-49) that formally established the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). This law broadens Congress's oversight role, and explicitly includes homeland security and critical infrastructure as separately identifiable components of national security that the President must consider when evaluating the national security implications of foreign investment transactions. The law also grants the President the authority to suspend or block foreign investments that are judged to threaten U.S. national security, although the law does not define what constitutes national security relative to a foreign investment. It also requires review of investments by foreign investors owned or controlled by foreign governments. Through the fall of 2016, the law has been used twice to block a foreign acquisition of a U.S. firm.56 At times, the law has drawn Congress into a greater dialogue over the role of foreign investment in the economy and the relationship between foreign investment and the general concept of national economic security.

Internationally, over the past decade national security-related concerns have become more prominent in the investment policies of numerous countries.57 As a result, countries have adopted new measures to restrict foreign investment or have amended existing laws concerning investment-related national security reviews. International organizations have long recognized the legitimate concerns of nations in restricting foreign investment in certain sectors of their economies, but the recent increase in such restrictions has raised a number of policy issues. Countries have different approaches for reviewing and restricting foreign investment on national security-related grounds. These range from formal investment restrictions to complex review mechanisms with broad definitions and broad scope of application to provide host country authorities with wide discretion in the review process. As a result of these differences, foreign investors can face different entry conditions in different countries in similar economic activities.58

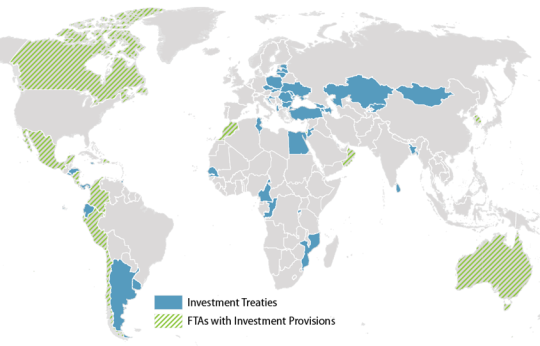

U.S. International Investment Agreements (IIAs)59

The United States negotiates international investment agreements (IIAs), based on a "model" Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT), to reduce restrictions on foreign investment, ensure nondiscriminatory treatment of investors and investment, and advance other U.S. interests. U.S. IIAs typically take two forms: (1) BITs, which require a two-thirds vote of approval in the Senate; or (2) BIT-like chapters in free trade agreements (FTAs), which require simple majority approval of implementing legislation by both houses of Congress (Figure 3). While U.S. IIAs are a small fraction of the more than 3,300 IIA agreements worldwide,60 they are often viewed as more comprehensive and of a higher standard than those of other countries. U.S. trade negotiating objectives, renewed in 2015 through Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), retained a principal negotiating objective to reduce or eliminate barriers to foreign investment while ensuring that foreign investors in the United States are not accorded "greater substantive rights" for investment protections than domestic investors.

|

|

Source: CRS, based on information from USTR and the Department of State. |

A focal point for Congress on investment issues likely will be the NAFTA renegotiation. Negotiators may look to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which represented the most recent set of investment rules negotiated by the United States. It carried over core investor protections (see text box), as well as added new provisions, including clarification of protections for investors and governments' right to regulate in the public interest, enhanced investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) procedures for transparency and public participation, and an exception allowing governments to decline to accept ISDS challenges against tobacco control measures. Although President Trump withdrew the United States from TPP, Congress may nevertheless revisit specific TPP provisions in considering NAFTA and future investment negotiations. For instance, Congress could examine how TPP's investor protections balance against other interests (such as protecting governments' regulatory ability) and the debates those provisions generated.

|

Core Investor Protections in U.S. IIAs Market access for investments. Non-discriminatory treatment of foreign investors and investments compared to domestic investors (national treatment) and to those of another country (most-favored-nation treatment). Minimum standard of treatment in accordance with customary international law, including fair and equitable treatment and full protection and security. Prompt, adequate, and effective compensation for expropriation, both direct and indirect, recognizing that, except in rare circumstances, non-discriminatory regulation is not an indirect expropriation. Timely transfer of funds into and out of the host country without delay using a market rate of exchange. Limits on performance requirements that, for example, condition approval of an investment on using local content. Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) for binding international arbitration of private investors' claims against host country governments for violation of investment obligations, along with requirements for transparency of ISDS proceedings. Exceptions for national security and prudential interests, among others. |