China-U.S. Trade Issues

U.S.-China economic ties have expanded substantially since China began reforming its economy and liberalizing its trade regime in the late 1970s. Total U.S.-China merchandise trade rose from $2 billion in 1979 (when China’s economic reforms began) to $636 billion in 2017. China is currently the United States’ largest merchandise trading partner, its third-largest export market, and its biggest source of imports. In 2015, sales by U.S. foreign affiliates in China totaled $482 billion. Many U.S. firms view participation in China’s market as critical to their global competitiveness. U.S. imports of lower-cost goods from China greatly benefit U.S. consumers. U.S. firms that use China as the final point of assembly for their products, or use Chinese-made inputs for production in the United States, are able to lower costs. China is also the largest foreign holder of U.S. Treasury securities (at $1.2 trillion as of April 2018). China’s purchases of U.S. debt securities help keep U.S. interest rates low.

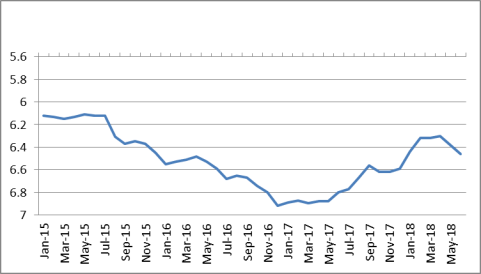

Despite growing commercial ties, the bilateral economic relationship has become increasingly complex and often fraught with tension. From the U.S. perspective, many trade tensions stem from China’s incomplete transition to a free market economy. While China has significantly liberalized its economic and trade regimes over the past three decades, it continues to maintain (or has recently imposed) a number of state-directed policies that appear to distort trade and investment flows. Major areas of concern expressed by U.S. policymakers and stakeholders include China’s alleged widespread cyber economic espionage against U.S. firms; relatively ineffective record of enforcing intellectual property rights (IPR); discriminatory innovation policies; mixed record on implementing its World Trade Organization (WTO) obligations; extensive use of industrial policies (such as subsidies and trade and investment barriers) to promote and protect industries favored by the government; and interventionist policies to influence the value of its currency. Many U.S. policymakers argue that such policies adversely impact U.S. economic interests and have contributed to U.S. job losses in some sectors.

The Trump Administration has pledged to take a more aggressive stance to reduce U.S. bilateral trade deficits, enforce U.S. trade laws and agreements, and promote “free and fair trade,” including in regard to China. On March 8, 2018, President Trump announced a proclamation imposing additional tariffs on steel (25%) and aluminum (10%), based on Section 232 national security justifications (China is the world’s largest producer of both of these commodities). On April 1, China announced that it had retaliated against the U.S. action by raising tariffs (from 15% to 25%) on various U.S. products, which together totaled $3 billion in 2017. On March 22, President Trump announced that action would be taken against China under Section 301 over its IPR policies deemed harmful to U.S. stakeholders. In addition, he stated that he would seek commitments from China to reduce the bilateral trade imbalance and to achieve “reciprocity” on tariff levels. On June 15, the United States Trade Representative (USTR) announced a two-stage plan to impose 25% ad valorem tariffs on $50 billion worth of Chinese imports. Under the first stage, U.S. tariffs would be increased on $34 billion worth of Chinese products and effective July 6. For the second stage, the USTR proposed increasing tariffs on $16 billion worth of Chinese imports, mainly targeting China’s industrial policies. China released its own two-stage list of counter-retaliation of equal magnitude. President Trump then threatened 10% ad valorem tariffs on another $400 billion worth of Chinese products. On July 6, the Trump Administration implemented the first round of tariff increases and China retaliated in kind. These tit-for-tat actions threaten to sharply reduce U.S.-China commercial ties, disrupt global supply chains, raise import prices for U.S. consumers and importers of Chinese inputs, and diminish economic growth in the United States and abroad.

China-U.S. Trade Issues

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Most Recent Developments

- U.S. Trade with China

- U.S. Merchandise Exports to China

- Major U.S. Merchandise Imports from China

- Trade in Services

- The U.S. Merchandise Trade Deficit with China

- The Transfer of Pacific Rim Production to China by Multinational Firms

- China as a Major Center for Global Supply Chains

- China Trade and U.S. Jobs

- U.S.-China Investment Ties: Overview

- China's Holdings of U.S. Public and Private Securities

- U.S. Residential Real Estate

- Bilateral Foreign Direct Investment Flows

- Alternative Measurements of Bilateral FDI Flows

- Chinese Restrictions on U.S. FDI in China

- Negotiations for a Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT)

- Concerns About Chinese FDI in the United States

- Major U.S.-China Trade Issues

- Chinese "State Capitalism"

- China's Plan to Modernize the Economy and Promote Indigenous Innovation

- New Restrictions on Information and Communications Technology

- Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) Issues

- Technology Transfer Issues

- Cyber-security Issues

- China's Obligations in the World Trade Organization

- WTO Implementation Issues

- China's Currency Policy

- The Trump Administration's Approach to Commercial Relations with China

- The Administration's Section 301 Case on China's IPR Policies

- U.S. and Chinese Products that Have Been or Could Be Subject to Increased Tariffs Resulting from the Section 301 Dispute

- Economic Effects of Section 301 Tariff Increases

- Section 232 Tariffs on Steel and Aluminum

- Implications of Recent Trade Action against China

Figures

- Figure 1. Top 5 U.S. Merchandise Export Markets in 2017

- Figure 2. Top 5 Sources of U.S. Merchandise Imports: 2017

- Figure 3. Major U.S. Services Trading Partners in 2017

- Figure 4. U.S. Merchandise Trade Balance with China: 2000-2017

- Figure 5. Five Largest U.S. Merchandise Trade Imbalances in 2017

- Figure 6. U.S. Manufactured Imports from Pacific Rim Countries as a Percentage of Total U.S. Manufactured Imports: 1990 and 2017

- Figure 7. U.S. Manufactured Imports from China and Japan as a Percentage of U.S. Total Imports: 1990-2017 (%)

- Figure 8. Estimated Percentage Foreign Value-Added to China's Exports in 2011

- Figure 9. Two Measurements of U.S. Trade in Goods and Services: 2011

- Figure 10. Top Five Country Locations of Facilities that Supplied Apple Corporation in 2017

- Figure 11. China's Holdings of U.S. Treasury Securities: 2002-2017

- Figure 12. Sales by Foreign Affiliates of U.S. Firms by Country in 2015

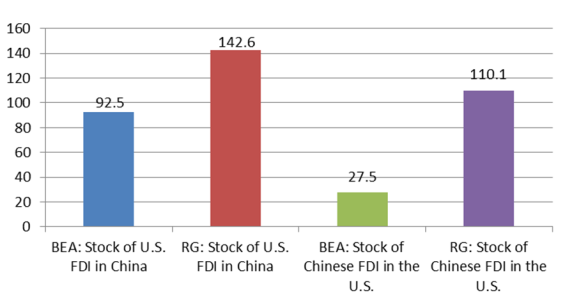

- Figure 13. BEA and RG Estimates of the Stock of U.S.-China FDI through 2016

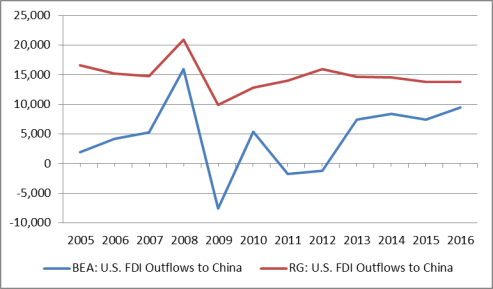

- Figure 14. BEA and RG Data on Annual U.S. FDI Flows to China: 2005-2016

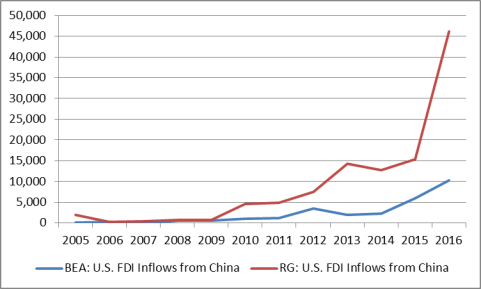

- Figure 15. BEA and RG Data on Chinese FDI Flows to the United States: 2005-2016

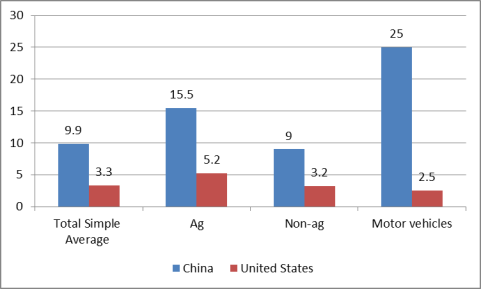

- Figure 16. China and U.S. Simple Average MFN Tariff Rates

- Figure 17. RMB-Dollar Exchange Rates: January 2015 to June 2018

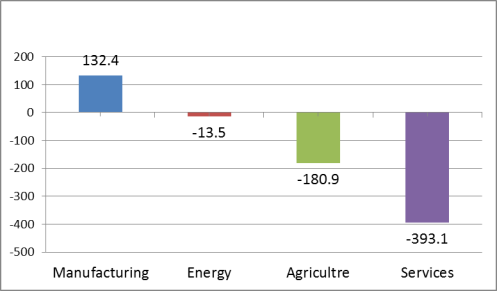

- Figure 18. Estimated Sector Effect on U.S. Employment if Both U.S. and China Increased Tariffs by 25% on $150 Billion Worth of Imports from Each Other

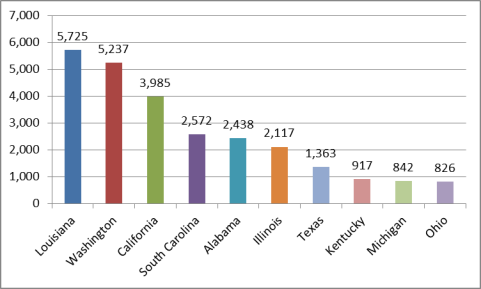

- Figure 19. Estimate of the Top 10 States that Could be Impact by Lost Exports if China Retaliated Against U.S. Section 301-Related Tariffs

Tables

- Table 1. U.S. Merchandise Trade with China: 1980-2017

- Table 2. Major U.S. Exports to China in 2017: NAIC 4-Digit Level

- Table 3. Major U.S. Merchandise Export Markets

- Table 4. Major U.S. Merchandise Imports From China in 2017: NAIC 4-Digit Level

- Table 5. U.S Imports of ATP Products from China by Major Category in 2017

- Table 6. China's Holdings of U.S. Treasury Securities: 2002-2017

- Table 7. Summary of BEA Data on U.S.-China FDI Flows: 2016

- Table 8. Top 10 Chinese Investments in the United States: 2005-2017

- Table 9. Top 20 Chinese Companies on Fortune's Global 500 in 2018

- Table 10. Summaries of WTO U.S. Dispute Settlement Cases Against China

- Table 11. Top 15 Merchandise Imports from China on an HTS 2-Digit Level and Summary of Categories Impacted by Actual or Proposed U.S. Section 301 Tariffs

- Table 12. U.S. Section 301 First Round of 25% Ad Valorem Tariffs on $34 Billion Worth of Imports from China (Implemented July 6)

- Table 13. U.S. Section 301 Second Round of 25% Ad Valorem Tariffs on $16 Billion Worth of Imports from China (Proposed)

- Table 14. China's First Round of Retaliatory of 25% Ad Valorem Tariffs on U.S. Products in Response to U.S. Section 301 Action (Implemented July 6)

- Table 15. China's Proposed Second Round Retaliatory List of 25% of Ad Valorem Tariffs if U.S. Second Round of Section 301 Tariff Increases are Implemented

- Table 16. Trump Administration's Proposed 10% Ad Valorem Tariffs on $200 Billion Worth of Chinese Imports

- Table 17. Sales by Selective U.S. Firms to China in 2017

- Table 18. China's Retaliatory Tariffs Against the U.S. for Increased Steel and Aluminum Tariffs

Summary

U.S.-China economic ties have expanded substantially since China began reforming its economy and liberalizing its trade regime in the late 1970s. Total U.S.-China merchandise trade rose from $2 billion in 1979 (when China's economic reforms began) to $636 billion in 2017. China is currently the United States' largest merchandise trading partner, its third-largest export market, and its biggest source of imports. In 2015, sales by U.S. foreign affiliates in China totaled $482 billion. Many U.S. firms view participation in China's market as critical to their global competitiveness. U.S. imports of lower-cost goods from China greatly benefit U.S. consumers. U.S. firms that use China as the final point of assembly for their products, or use Chinese-made inputs for production in the United States, are able to lower costs. China is also the largest foreign holder of U.S. Treasury securities (at $1.2 trillion as of April 2018). China's purchases of U.S. debt securities help keep U.S. interest rates low.

Despite growing commercial ties, the bilateral economic relationship has become increasingly complex and often fraught with tension. From the U.S. perspective, many trade tensions stem from China's incomplete transition to a free market economy. While China has significantly liberalized its economic and trade regimes over the past three decades, it continues to maintain (or has recently imposed) a number of state-directed policies that appear to distort trade and investment flows. Major areas of concern expressed by U.S. policymakers and stakeholders include China's alleged widespread cyber economic espionage against U.S. firms; relatively ineffective record of enforcing intellectual property rights (IPR); discriminatory innovation policies; mixed record on implementing its World Trade Organization (WTO) obligations; extensive use of industrial policies (such as subsidies and trade and investment barriers) to promote and protect industries favored by the government; and interventionist policies to influence the value of its currency. Many U.S. policymakers argue that such policies adversely impact U.S. economic interests and have contributed to U.S. job losses in some sectors.

The Trump Administration has pledged to take a more aggressive stance to reduce U.S. bilateral trade deficits, enforce U.S. trade laws and agreements, and promote "free and fair trade," including in regard to China. On March 8, 2018, President Trump announced a proclamation imposing additional tariffs on steel (25%) and aluminum (10%), based on Section 232 national security justifications (China is the world's largest producer of both of these commodities). On April 1, China announced that it had retaliated against the U.S. action by raising tariffs (from 15% to 25%) on various U.S. products, which together totaled $3 billion in 2017. On March 22, President Trump announced that action would be taken against China under Section 301 over its IPR policies deemed harmful to U.S. stakeholders. In addition, he stated that he would seek commitments from China to reduce the bilateral trade imbalance and to achieve "reciprocity" on tariff levels. On June 15, the United States Trade Representative (USTR) announced a two-stage plan to impose 25% ad valorem tariffs on $50 billion worth of Chinese imports. Under the first stage, U.S. tariffs would be increased on $34 billion worth of Chinese products and effective July 6. For the second stage, the USTR proposed increasing tariffs on $16 billion worth of Chinese imports, mainly targeting China's industrial policies. China released its own two-stage list of counter-retaliation of equal magnitude. President Trump then threatened 10% ad valorem tariffs on another $400 billion worth of Chinese products. On July 6, the Trump Administration implemented the first round of tariff increases and China retaliated in kind. These tit-for-tat actions threaten to sharply reduce U.S.-China commercial ties, disrupt global supply chains, raise import prices for U.S. consumers and importers of Chinese inputs, and diminish economic growth in the United States and abroad.

Introduction

Economic and trade reforms begun in 1979 have helped transform China into one of the world's biggest and fastest-growing economies. China's economic growth and trade liberalization, including comprehensive trade commitments made upon its entry to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, have led to a sharp expansion in U.S.-China commercial ties. Yet, bilateral trade relations have become increasingly strained in recent years over a number of issues, including China's mixed record on implementing its WTO obligations; infringement of U.S. intellectual property (such as through cyber-theft of U.S. trade secrets and forced technology requirements placed on foreign firms); increased use of industrial policies to promote and protect domestic Chinese firms; extensive trade and foreign investment restrictions; lack of transparency in trade rules and regulations; distortionary economic policies that have led to overcapacity in several industries; and its large merchandise trade surplus with the United States. China's economic and trade conditions, policies, and acts have a significant impact on the U.S. economy as whole as well as specific U.S. sectors and thus are of concern to Congress. This report provides an overview of U.S.-China commercial ties, identifies major issues of contention, describes the Trump Administration's trade policies toward China, and reviews possible outcomes.

Most Recent Developments

U.S.-China commercial ties are complex and have become increasingly contentious, due largely to China's incomplete transition to a free market economy. The Trump Administration has indicated its intent to take a harder line on trade policy towards China (and other countries). The most significant action it has taken to date has been the initiation of a Section 301 case against China's policies on intellectual property rights, which could result in several rounds of tit-for-tat trade sanctions and retaliation.1

- A July 25 joint statement by the United States and European Union, said that the two sides would "work closely together with like-minded partners to reform the WTO and to address unfair trading practices, including intellectual property theft, forced technology transfer, industrial subsidies, distortions created by state owned enterprises, and overcapacity." (This appears to have been largely aimed at China).2

- On July 6, the Trump Administration raised tariffs by 25% on $34 billion worth of imports from China. On the same day, China announced it would retaliate against a comparable level of U.S. products. In response to China's tariff increases, the United States Trade Representative (USTR) on July 10, threatened to increase tariffs by 10% on $200 billion worth of Chinese products.

- On March 8, 2018, the Trump Administration announced that it would impose additional imports tariffs on steel (by 25%) and aluminum (10%), based on "national security" justifications under the 1962 Trade Act, as amended. On April 2, China raised duties (by 15% to 25%) on about $3 billion worth of imports frim from the United States, largely targeting agricultural products.

U.S. Trade with China3

U.S.-China trade rose rapidly after the two nations reestablished diplomatic relations in January 1979, signed a bilateral trade agreement in July 1979, and provided mutual most-favored-nation (MFN) treatment, beginning in 1980.4 In that year (which was shortly after China's economic reforms began), total U.S.-China trade (exports plus imports) was approximately $4 billion. China ranked as the United States' 24th-largest trading partner, 16th-largest export market, and 36th-largest source of imports. In 2017, total U.S. merchandise trade with China was $636 billion, making China the United States' largest trading partner (see Table 1).

|

Year |

U.S. Exports |

U.S. Imports |

U.S. Trade Balance |

|

1980 |

3.8 |

1.1 |

+2.7 |

|

1990 |

4.8 |

15.2 |

-10.4 |

|

2000 |

16.3 |

100.1 |

-83.8 |

|

2010 |

91.9 |

365.0 |

-273.0 |

|

2011 |

104.1 |

399.4 |

-295.3 |

|

2012 |

110.5 |

425.6 |

-315.1 |

|

2013 |

121.7 |

440.4 |

-318.7 |

|

2014 |

123.7 |

468.5 |

-344.8 |

|

2015 |

115.9 |

483.2 |

-367.3 |

|

2016 |

115.6 |

462.6 |

-347.0 |

|

2017 |

130.4 |

505.6 |

-375.2 |

Source: U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) DataWeb.

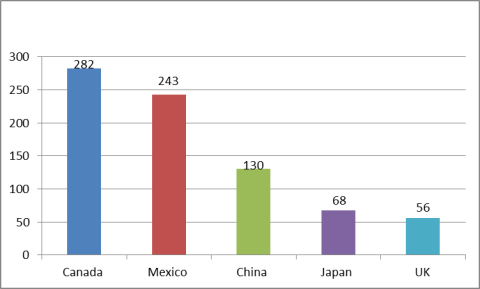

U.S. Merchandise Exports to China

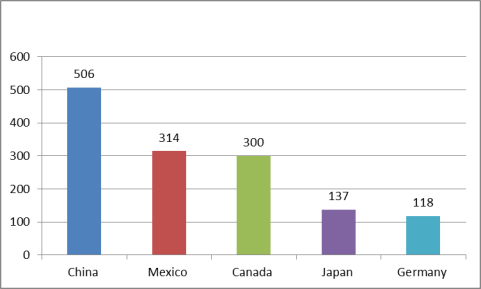

U.S. merchandise exports to China in 2017 were $115.6 billion, up 12.8% from the previous year. China was the third-largest U.S. merchandise export market after Canada and Mexico (see Figure 1). China was the second-largest U.S. agricultural export market in 2017, at $19.6 billion, 63% of which consisted of soybeans. From 2000 to 2017, the share of total U.S. merchandise exports going to China rose from 2.1% to 8.4%. As indicated in Table 2, the top five U.S. goods exports to China in 2017 were (1) aerospace products (mainly civilian aircraft and parts); (2) oil seeds and grains (mainly soybeans); (3) motor vehicles; (4) semiconductors and electronic components; and (5) waste and scrap. From 2002 to 2017, U.S. exports to China rose by 491%, faster than the growth rate for U.S. exports to any of its top 10 export markets in 2017 (see Table 3). During the first five months of 2018, U.S. merchandise exports to China rose by 7.8% year-on-year.

|

Figure 1. Top 5 U.S. Merchandise Export Markets in 2017 ($ in billions) |

|

|

Source: USITC DataWeb. |

Table 2. Major U.S. Exports to China in 2017: NAIC 4-Digit Level

($ in millions and percentage change)

|

NAIC Code |

Products |

2016 |

2017 |

Change |

||||

|

3364 |

AEROSPACE PRODUCTS & PARTS |

|

|

|

||||

|

1111 |

OILSEEDS & GRAINS |

|

|

|

||||

|

3361 |

MOTOR VEHICLES |

|

|

|

||||

|

3344 |

SEMICONDUCTORS & OTHER ELECTRONIC COMPONENTS |

|

|

|

||||

|

2111 |

OIL & GAS |

|

|

|

||||

|

9100 |

WASTE AND SCRAP |

|

|

|

||||

|

3345 |

NAVIGATIONAL/MEASURING/MEDICAL/CONTROL INSTRUMENTS |

|

|

|

||||

|

3251 |

BASIC CHEMICALS |

|

|

|

||||

|

3252 |

RESIN, SYN RUBBER, ARTF & SYN FIBERS/FIL |

|

|

|

||||

|

3254 |

PHARMACEUTICALS & MEDICINES |

|

|

|

||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

Source: USITC DataWeb.

Note: NAIC is the North American Industrial Classification system.

|

Country |

2002 |

2017 |

Percent Change |

||||

|

Canada |

|

|

|

||||

|

Mexico |

|

|

|

||||

|

China |

|

|

|

||||

|

Japan |

|

|

|

||||

|

United Kingdom |

|

|

|

||||

|

Germany |

|

|

|

||||

|

Korea |

|

|

|

||||

|

Netherlands |

|

|

|

||||

|

Hong Kong |

|

|

|

||||

|

Brazil |

|

|

|

||||

|

Global Total |

|

|

|

Source: USITC DataWeb and Global Trade Atlas.

Note: Ranked according to the top 10 U.S. merchandise export markets in 2017.

Many trade analysts argue that China could prove to be a much more significant market for U.S. exports in the future. China is one of the world's fastest-growing economies, and healthy economic growth is projected to continue in the years ahead, provided that it implements new comprehensive economic reforms. China's goals of modernizing its infrastructure, rebalancing the economy, upgrading industries, boosting the services sector, and enhancing the social safety net could generate substantial new demand for foreign goods and services. Economic growth has improved the purchasing power of Chinese citizens considerably, especially those living in urban areas along the east coast of China. In addition, China's large foreign exchange reserves (at $3.1 trillion as of May 2018) and its huge population (at 1.39 billion) make it a potentially enormous market. To illustrate

- A January 2017 study prepared by Oxford Economics for the U.S.-China Business Council estimated that in 2015 U.S. exports of goods and services to China plus bilateral FDI flows directly and indirectly supported 2.6 million U.S. jobs and contributed $216 billion to U.S GDP. The study further predicted that U.S. exports of goods and services to China would grow from $165 billion in 2015 to over $520 billion by 2030.5

- In 2016, Chinese visitors to the United States totaled 3.0 million (up 15.4% over the previous year), ranking China as the fifth-largest source of foreign visitors to the United States.6 Chinese visitors spent $33 billion in the United States in 2016 (including on education), which was the largest source of visitor spending in the United States.7 The U.S. Department of Commerce projects that by 2021, Chinese visitors to the United States will total 5.7 million.8

- China has the world's largest mobile phone network with 1.48 billion mobile phone subscribers as of April 2018,9 and the largest number of internet users at 753 million,10 as of December June 2017.

- China's online sales in 2016 totaled $752 billion (more than double the U.S. level at $369 billion).11

- Boeing Corporation delivered 202 planes to China in 2017 (26% of total global deliveries), making it Boeing's largest market outside the United States.12 Boeing predicts that over the next 20 years (2017-2036), China will need 7,240 new airplanes valued at nearly $1.1 trillion and will be Boeing's largest commercial airplane customer outside the United States.13

- General Motors (GM) reported that it sold more cars and trucks in China than in the United States each year from 2010 to 2017.14 GM's China sales in 2017 were 4.0 million vehicles, compared to 3.0 million in the United States. Equity income from GM's joint venture operations in China was $2.0 billion in 2017. GM vehicle unit sales to China accounted for 42.1% of its global total.15 GM expects China's vehicle market to increase by 5 million units or more by 2020.16 In addition, U.S. motor vehicle exports to China were $9.9 billion in 2017, making it the second-largest U.S. motor vehicle export market after Canada.17

- According to estimates by Credit Suisse (a global financial services company), China overtook the United States in 2015 to become the country with the largest middle class at 109 million adults (with wealth between $50,000 and $500,000); the U.S. level was estimated at 92 million.18 A study by the Brookings Institute predicts that spending by China's middle class (using 2011 purchasing power parity measurements) will rise from $4.2 trillion in 2015 (12% of global total) to $14.3 trillion (22% of global total) in 2030. China's 2030 middle class consumption levels are predicted to be more than three times U.S. levels.19

- From 2007 to 2016, China's private consumption grew at an average annual rate of 8.9%, compared to 1.6% growth in the United States.20

Major U.S. Merchandise Imports from China

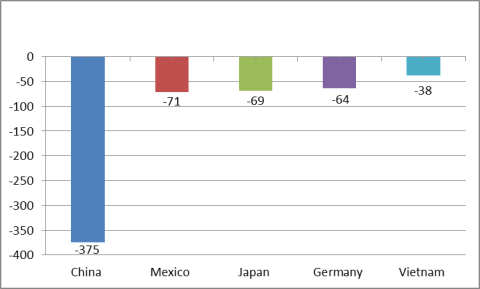

China was the largest source of U.S. merchandise imports in 2017, at $506 billion, up 9.3% over the previous year. China's share of total U.S. merchandise imports rose from 8.2% in 2000 to 21.6% in 2017. The importance (ranking) of China as a source of U.S. imports has risen sharply, from eighth largest in 1990, to fourth in 2000, to second in 2004-2006, and to first in 2007-present (see Figure 2). The top five U.S. imports from China in 2017 were (1) communications equipment; (2) computer equipment; (3) miscellaneous manufactured commodities (such as toys and games); (4) apparel; and (5) semiconductors and other electronic components (see Table 4). China was also the fourth-largest source of U.S. agricultural imports in 2017 at $4.5 billion.

|

Figure 2. Top 5 Sources of U.S. Merchandise Imports: 2017 ($ in billions) |

|

|

Source: USITC DataWeb. |

Table 4. Major U.S. Merchandise Imports From China in 2017: NAIC 4-Digit Level

($ in millions and percentage change)

|

NAIC Code |

Products |

2016 |

2017 |

Percent Change |

||||

|

3342 |

COMMUNICATIONS EQUIPMENT |

|

|

|

||||

|

3341 |

COMPUTER EQUIPMENT |

|

|

|

||||

|

3399 |

MISCELLANEOUS MANUFACTURED COMMODITIES |

|

|

|

||||

|

3152 |

APPAREL |

|

|

|

||||

|

3344 |

SEMICONDUCTORS & OTHER ELECTRONIC COMPONENTS |

|

|

|

||||

|

3371 |

HOUSEHOLD & INSTITUTIONAL FURN & KITCHEN CABINETS |

|

|

|

||||

|

3352 |

HOUSEHOLD APPLIANCES AND MISC MACHINES |

|

|

|

||||

|

3162 |

FOOTWEAR |

|

|

|

||||

|

3261 |

PLASTICS PRODUCTS |

|

|

|

||||

|

3363 |

MOTOR VEHICLE PARTS |

|

|

|

||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

Source: USITC DataWeb.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, nearly all U.S. imports from China were low-value, labor-intensive products, such as toys and games, consumer electronic products, footwear, and textiles and apparel. However, over the past few years, an increasing proportion of U.S. imports from China are more technologically advanced products (see text box below).

|

U.S.-China Trade in Advanced Technology Products According to the U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. imports of "advanced technology products" (ATP) from China in 2017 totaled $171.1 billion. Information and communications products were by far the largest U.S. ATP import from China, accounting for 91% of U.S. ATP imports from China and 60% of U.S. global imports of this category (see Table 5). ATP products accounted for 33.8% of total U.S. merchandise imports from China. In addition, 36.8% of total U.S. ATP imports were from China (compared with 14.1% in 2003). U.S. ATP exports to China in 2017 were $35.7 billion; these accounted for 27.4% of total U.S. exports to China and 10.1% of U.S. global ATP exports. In comparison, U.S. ATP exports to China in 2003 were $8.3 billion, which accounted for 29.2% of U.S. exports to China and 4.6% of total U.S. ATP exports.21 The United States ran a $135.3 billion deficit in its ATP trade with China in 2017, up from a $21.0 billion deficit in 2003. Some see the large and growing U.S. trade deficit in ATP with China as a source of concern, contending that it signifies the growing international competitiveness of China in high technology. Others dispute this, noting that a large share of the ATP imports from China are in fact relatively low-end technology products and parts, such as notebook computers, or are products that are assembled in China using imported high technology parts that are largely developed and/or made elsewhere. Some Members of Congress have raised concerns over possible national security implications of China's significant role in global supply chains for various ATP products, especially those that may be procured by U.S. government agencies.22 |

|

Advanced Technology Products (ATP) Category |

U.S. Imports from China |

Total U.S. Imports |

Imports from China |

|

Biotechnology |

194 |

26,127 |

0.7 |

|

Life Sciences |

2,594 |

45,705 |

5.7 |

|

Opto-Electronics |

5,132 |

23,036 |

22.3 |

|

Information & communications |

155,535 |

259,392 |

60.0 |

|

Electronics |

4,482 |

41,426 |

10.8 |

|

Flexible Manufacturing |

1,347 |

13,726 |

9.8 |

|

Advanced Materials |

413 |

2,844 |

14.5 |

|

Aerospace |

1,027 |

48,592 |

2.1 |

|

Weapons |

138 |

902 |

15.3 |

|

Nuclear Technology |

25 |

1,698 |

1.5 |

|

Total U.S. ATP imports |

171,067 |

464,258 |

36.8 |

Source: U.S. Census Bureau.

Trade in Services

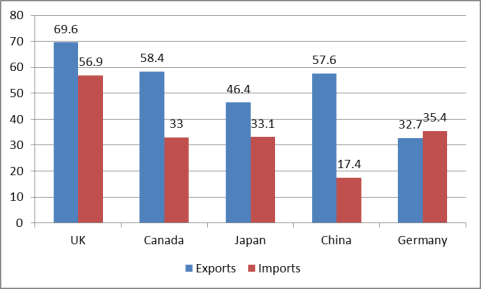

China is a major U.S. trading partner in services. In 2017, China was the 4th-largest services trading partner at $75 billion, the 3rd-largest services export market at $57.6 billion, and the 8th-largest source of services imports at $17.4 billion (see Figure 3). The United States ran a $40.2 billion services trade surplus with China, which was the largest services surplus of any U.S. trading partner.

|

Figure 3. Major U.S. Services Trading Partners in 2017 ($ in billions) |

|

|

Source: BEA. Note: Top five U.S. trading partners in total services trade (exports plus imports) in 2017. |

The U.S. Merchandise Trade Deficit with China

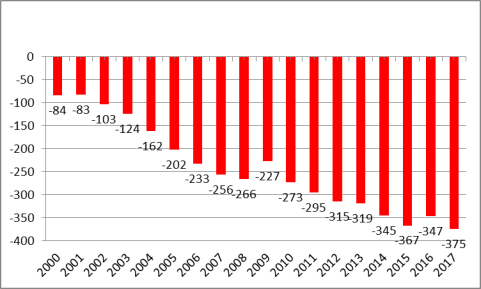

A major concern among some U.S. policymakers is the size of the U.S. merchandise trade deficit with China, which rose from $10 billion in 1990 to $367 billion in 2015 (see Figure 4). The deficit fell to $347 billion in 2016, but rose to $375 billion in 2017.23 For the past several years, the U.S. merchandise trade deficit with China has been significantly larger than with any other U.S. trading partner (see Figure 5). Some analysts contend that the large U.S. merchandise trade deficits with China indicate that the trade relationship is somehow unbalanced, unfair, and damaging to the U.S. economy. Others argue that such deficits are largely a reflection of shifts in global production and the emergence of extensive and complex supply chains, where China is often the final point of assembly for export-oriented multinational firms that source goods from multiple countries.

|

Figure 4. U.S. Merchandise Trade Balance with China: 2000-2017 ($ in billions) |

|

|

Source: USITC DataWeb. |

|

Figure 5. Five Largest U.S. Merchandise Trade Imbalances in 2017 ($ in billions) |

|

|

Source: USITC DataWeb. |

The Transfer of Pacific Rim Production to China by Multinational Firms

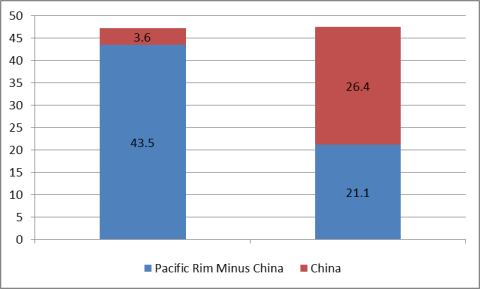

Many analysts contend that the sharp increase in U.S. imports from China (and hence the growing bilateral trade imbalance) is largely the result of movement in production facilities from other (primarily Asian) countries to China. That is, various products that used to be made in such places as Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, etc., and then exported to the United States, are now made in China (in many cases, by foreign firms). To illustrate, in 1990, the share of U.S. manufactured imports from Pacific Rim countries (including China) was 47.1%, and in 2017, that share remained relatively constant at 47.1% (see Figure 6).24 What changed was the country source of those imports. In 1990, China accounted for 7.6% of the share of U.S. manufactured imports from the Pacific Rim, but by 2017, that share increased to 55.4%. In other words, between 1990 and 2016, the role of China as a supplier of U.S. manufactured products among Pacific Rim countries increased sharply, while the relative importance of the rest of the Pacific Rim (excluding China) for these products sharply decreased. This was partly due to many multinational firms shifting their export-oriented manufacturing facilities from other countries to China.

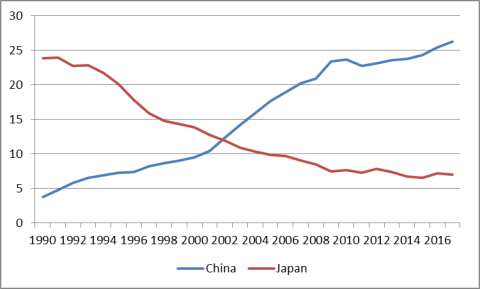

A significant amount of the shift in production appears to have involved Japan. In 1990, Japan was the source of 23.8% of U.S. manufactured imports, but by 2017 this level had dropped to 7.0%. Conversely, China's share of U.S. manufactured imports rose from 3.8% to 26.2% (see Figure 7). Japan accounted for the single largest U.S. bilateral merchandise trade deficit for many years until it was overtaken by China in 2000.

|

Figure 7. U.S. Manufactured Imports from China and Japan as a Percentage of U.S. Total Imports: 1990-2017 (%) |

|

|

Source: USITC DataWeb. |

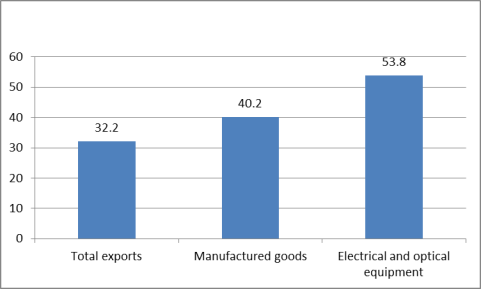

China as a Major Center for Global Supply Chains

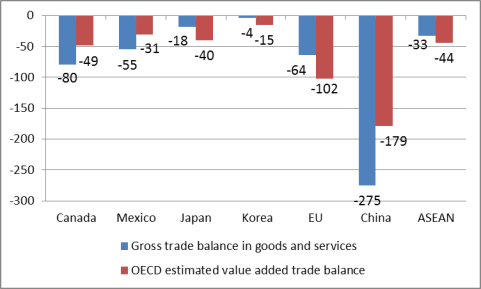

A joint study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the WTO has sought to estimate trade flows according to the value that was added in each country. For example, the OECD/WTO study estimated that in 2011, 32.2% of the overall value of China's gross exports was comprised of foreign imports. This level increased to 40.2% for China's total manufactured exports, and for electrical and optical equipment, it was 53.8% (see Figure 8). The study estimated that if bilateral trade imbalances were measured according to the value of trade that occurred domestically in each country, the U.S. trade deficit in goods and services with China in 2011 (the most recent year available) would decline by 35% (from $278.6 billion to $181.1 billion) (see Figure 9). This is largely because of the role of trade in intermediate goods (parts and materials imported to make products). For example, the World Bank estimates that U.S. intermediate exports and imports to and from China in 2016 were $19.3 billion and $33.5 billion, respectively.25 Thus, many Chinese products contain U.S.-made inputs and some U.S. products contain Chinese-made inputs.

|

Figure 8. Estimated Percentage Foreign Value-Added to China's Exports in 2011 |

|

|

Source: OECD/WTO Trade in Value-Added, October 2015. |

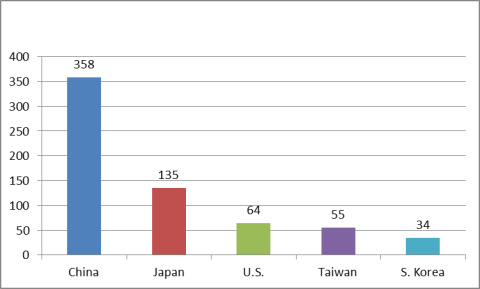

According to Apple Corporation, it used over 200 corporate suppliers with nearly 900 facilities located around the world. The top five largest country sources of these facilities in 2017 were China (358), Japan (137), the United States (64), Taiwan (55), and South Korea (34) (see Figure 10). Some U.S. corporate suppliers to Apple have facilities located in many countries. For example, Intel Corporation has 10 facilities that supply products to Apple, three of which are located in the United States, two in China, two in Malaysia, and one each in Ireland, Israel, Malaysia, and Vietnam.26 Apple iPhones are mainly assembled in China by Taiwanese companies (Foxconn and Pegatron) using a number of intermediate goods imported from abroad (or in many cases, intermediates made by foreign firms in China). Many analysts have estimated that the value-added that occurs in China in the production of the iPhone is small relative to the total value of the product because it mainly involves assembling foreign-made or foreign-owned components. Apple Corporation, on the other hand, is thought to be the single largest beneficiary (in terms of gross profit) on the sale of the iPhone. However, conventional trade data does not accurately attribute the value-added that occurs in each stage of making the iPhone. Rather, when the United States imports iPhones from China, U.S. trade data attributes nearly the full value of the product as originating in China, which some argue artificially inflates the size of the U.S. trade deficit with China.

One 2010 study estimated that in 2009, China exported 11.3 million iPhones to the United States, with a shipping price of $179 per unit and total export value at $2.0 billion. The study estimated that 96.4% of the value of the iPhone was attributed to foreign suppliers and producers of components and parts, including the United States (at $122 million). Standard trade data would put China's trade surplus in iPhone trade with the United States at $1.9 billion, but that level would fall to $73.5 million if that trade was measured according to the value-added that occurred in each country.27 Several analysts have concluded that Apple's innovation in developing and engineering its products, along with its ability to source most of its production in low-cost countries, such as China, has helped enable the company to become a highly competitive and profitable firm (as well as a source for high-paying jobs in the United States).28 Apple products illustrate that the rapidly changing nature of global supply chains has made it increasingly difficult to interpret the implications of U.S. trade data because, while they may show where products are being imported from, they often fail to reflect who benefits from that trade.

China Trade and U.S. Jobs

Measuring and assessing the benefits and costs of growing U.S.-China economic ties are often hotly debated among U.S. policymakers and economists, particularly in regard to its impact on various manufacturing sectors and workers.

The impact on U.S. employment (especially in various manufacturing sectors) resulting from imports from China (particularly after it joined the WTO in 2001) has been a major point of contention. Some critics of U.S. trade policy toward China attempt to link U.S. job losses to the growth and size of U.S. imports from China and/or the bilateral trade imbalance. For example, a study by the Economic Policy Institute (EPI) in December 2014 claims that growth in the U.S. goods trade deficit with China between 2001 and 2013 "eliminated or displaced" 3.2 million U.S. jobs (three-fourths of which were in manufacturing).29 The authors stated that they used an input-output model that "estimated the amount of labor, or number of jobs, that is required to produce a given volume of exports and the labor displaced when a given volume of imports is substituted for domestic output." The difference between the two numbers is thus the estimated jobs displaced by the trade deficit. Critics of the EPI study argue that the methodology used is flawed. First, the study essentially takes the Department of Commerce's estimates of the number of jobs "supported" by each $1 billion in exports (5,744 in 2016)30 and makes the assumption that each $1 billion in imports must displace the same level of jobs, a notion that most economists would disagree with. For example, not all imports from China compete directly with U.S. producers. Many are products that used to be made in other countries, and thus an increase in imports from China alone did not necessarily displace U.S. domestic producers. In addition, some imports from China contain U.S.-made intermediate parts (such as semiconductors) made in the United States. Many imports from China are final assembled products (such as Apple iPhones) with a relatively small share of value-added from China, and the jobs generated or supported by innovating the products are not accounted for in the trade data. Finally, factors other than trade, such as technological innovation, may also affect job levels in some sectors.

Similarly, while China is the largest source of U.S. merchandise imports, the overall impact on the U.S. economy is relatively small. A Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco study examined U.S. consumer spending and estimated that, in 2010, U.S. personal consumption expenditures (PCE) of domestically sourced goods and services goods was 88.5% of total U.S. PCE (total imports accounted for 11.5%). Imports from China accounted for 2.7% of U.S. PCE, but less than half of this amount was attributed to the actual cost (price) of Chinese imports—the rest went to U.S. businesses and workers transporting, selling, and marketing the Chinese-made products, which, the study estimated, would reduce China's share of U.S. PCE to 1.9%.31

Economists generally argue that trade has an overall positive impact on the economy. Low-cost imports boost consumer welfare, increase consumer choices, and help lower inflation. However, some economists contend that the benefits of trade are not equally spread. Some sectors can be negatively impacted, affecting employment and wages, and such negative effects can be concentrated in certain regions or industries, and adjusting to such shocks can be challenging. A 2014 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) concluded that increased import penetration from China from 1999 to 2011 directly and indirectly resulted in net U.S. job losses of 2.0 million to 2.4 million U.S. jobs, and accounted for 10% of the decline in U.S. manufacturing jobs during this period.32

Another NBER study asserted that China's rise as an economic power has "induced an epochal shift in patterns of world trade" and has "challenged much of the received empirical wisdom about how labor markets adjust to trade shocks." The study said that for workers in import-competing firms, "adjustment in local labor markets is remarkably slow, with wages and labor-force participation rates remaining depressed and unemployment rates remaining elevated for at least a full decade after the China trade shock commences. Exposed workers experience greater job churning and reduced lifetime income," in part because workers that may lose their jobs due to imports often remain in highly exposed industries or regions, which are subject to further trade shocks.33 The study claimed that there is little evidence for substantial off-setting employment gains in local industries not exposed to the trade shock.

Critics of the two NBER studies contend that while trade may impact the composition of jobs in the U.S. economy, it has little long-term effect on the number of jobs, which they argue is largely a function of aggregate demand. They also point out that between 2010 and 2015, the number of U.S. manufacturing jobs rose by 6.8% even though U.S. imports from China increased by 32.4%. In addition, U.S. manufacturing output during this period rose by 15.3%. Some economists contend that U.S. productivity has been a major cause of job losses in manufacturing. A study by Ball State University attributed 88% of U.S. manufacturing job losses from 2000 to 2010 to productivity gains, noting that had the United States "kept 2000-levels of productivity and applied them to 2010-levels of production, we would have required 20.9 million manufacturing workers. Instead, we employed only 12.1 million."34

Similarly, while China is the largest source of U.S. merchandise imports, the overall impact on the U.S. economy is relatively small. A Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco study examined U.S. consumer spending and estimated that, in 2010, U.S. personal consumption expenditures (PCE) of domestically sourced goods and services goods was 88.5% of total U.S. PCE (total imports accounted for 11.5%). Imports from China accounted for 2.7% of U.S. PCE, but less than half of this amount was attributed to the actual cost (price) of Chinese imports—the rest went to U.S. businesses and workers transporting, selling, and marketing the Chinese-made products, which, the study estimated, would reduce China's share of U.S. PCE to 1.9%.35

U.S.-China Investment Ties: Overview

Investment plays a large and growing role in U.S.-China commercial ties.36 China's investment in U.S. assets can be broken down into several categories, including holdings of U.S. securities, foreign direct investment (FDI), and other non-bond investments. The Department of the Treasury defines foreign holdings of U.S. securities as "U.S. securities owned by foreign residents (including banks and other institutions), except where the owner has a direct investment relationship with the U.S. issuer of the securities."37 U.S. statutes define FDI as "the ownership or control, directly or indirectly, by one foreign resident of 10% or more of the voting securities of an incorporated U.S. business enterprise or the equivalent interest in an unincorporated U.S. business enterprise, including a branch."38 The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) is the main U.S. government agency that collects and reports data on FDI flows to and from the United States, which is done on a balance of payment basis.39 China has also invested in a number of U.S. companies, projects, and various ventures that do not meet the U.S. definition of FDI, and thus, are not reflected in BEA's data.

For many years, the accumulation of foreign exchange reserves (FERs) has been a major driver of China's overseas investment. China's FERs result from: (1) large annual trade surpluses and FDI inflows; (2) intervention by the Chinese government to halt or slow the value of its currency, the renminbi (RMB); and (3) restrictions on capital outflows by private Chinese citizens. Rather than holding foreign currencies, such as U.S. dollars which would earn no interest, the Chinese government has invested much of those reserves abroad. For many years, much of that investment has gone into U.S. Treasury securities. Although they generate low returns, such securities are generally viewed globally as a relatively safe investment because they are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government and are liquid (e.g., easily sold), albeit generating relatively small rates of returns. More recently, the Chinese government has diversified its investments in order to obtain higher returns, such as by encouraging its firms (especially SOEs) to invest overseas to become more globally competitive, as well as to help China gain access to raw materials (such as oil), food, and technology. As a result, Chinese annual FDI outflows have grown significantly in recent years, rising from $21 billion in 2006 to $183 billion in 2016, making China the second-largest source of annual global FDI outflows.40

U.S. investment in China has largely been in the form of FDI flows (due in part to Chinese restrictions on portfolio investment).41 Initially, most U.S. FDI flows (especially after China began to open up its economy in 1979) likely went toward export-oriented manufacturing to take advantage of China's relatively low wages. In more recent years, as China's economy has rapidly grown, a larger share of U.S. FDI in China has gone to tap into the country's booming domestic demand for goods and services. However, many U.S. firms raise concerns that Chinese investment restrictions and requirements (such as technology sharing) often hamper their efforts.

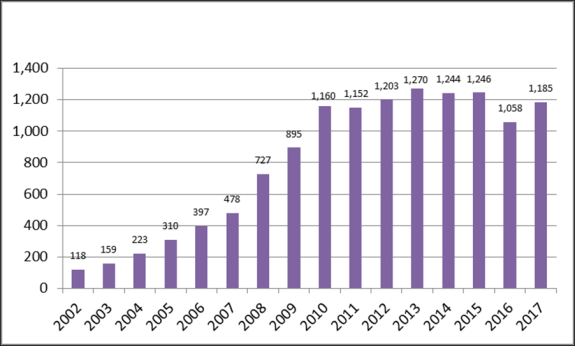

China's Holdings of U.S. Public and Private Securities42

China's holdings of U.S. public and private securities are significant and by far constitute the largest category of Chinese investment in the United States.43 These securities include U.S. Treasury securities, U.S. government agency (such as Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae) securities, corporate securities, and equities (such as stocks). China's investment in public and private U.S. securities totaled $1.54 trillion as of June 2017, making it the fourth-largest holder after Japan, the Cayman Islands, and the United Kingdom.44 U.S. Treasury securities, which help the federal government finance its budget deficits, are the largest category of U.S. securities held by China.45 As indicated in Table 6 and Figure 11 (which show end-year data), China's holdings of U.S. Treasury securities increased from $118 billion in 2002 to $1.24 trillion in 2014, but fell to $1.06 trillion in 2016. They rose to nearly $1.19 trillion in 2017, making China the largest foreign holder of U.S. Treasury securities.46 China's holdings of U.S. Treasury securities as a share of total foreign holdings rose from 9.6% in 2002 to a historical high of 26.1% in 2010. That level fell to 17.6% in 2016, but rose to 18.8% in 2017.47 China's holdings of U.S. Treasury securities as of April 2018 were $1.18 trillion and constituted 19.2% of total foreign holdings.

|

2002 |

2004 |

2006 |

2008 |

2010 |

2012 |

2014 |

2016 |

2017 |

|

|

China's holdings ($ billions) |

118 |

223 |

397 |

727 |

1,160 |

1,203 |

1,244 |

1,058 |

1,185 |

|

China's holdings as a percentage of total foreign holdings |

9.6% |

12.1% |

18.9% |

23.6% |

26.1% |

23.0% |

21.7% |

17.6% |

18.7% |

Source: U.S. Department of the Treasury.

Note: Annual data are year-end. Data excludes Hong Kong and Macau which are treated separately.

Some analysts and Members of Congress have sometimes raised concerns that China's large holdings of U.S. debt securities could give it leverage over U.S. foreign policy, including trade policy. They argue, for example, that China might attempt to sell (or threaten to sell) a large share of its U.S. debt securities over a policy dispute, which could damage the U.S. economy. Others counter that China's holdings of U.S. debt give it very little practical leverage over the United States. They argue that, given China's economic dependency on a stable and growing U.S. economy, and its substantial holdings of U.S. securities, any attempt to try to sell a large share of those holdings would likely damage both the U.S. and Chinese economies. It could also cause the U.S. dollar to sharply depreciate against global currencies, which could reduce the value of China's remaining holdings of U.S. dollar assets.

In the 112th Congress, the conference report accompanying the National Defense Authorization Act of FY2012 (H.R. 1540, P.L. 112-81) included a provision requiring the Secretary of Defense to conduct a national security risk assessment of U.S. federal debt held by China. The Secretary of Defense issued a report in July 2012, stating that "attempting to use U.S. Treasury securities as a coercive tool would have limited effect and likely would do more harm to China than to the United States. As the threat is not credible and the effect would be limited even if carried out, it does not offer China deterrence options, whether in the diplomatic, military, or economic realms, and this would remain true both in peacetime and in scenarios of crisis or war."48

U.S. Residential Real Estate

Over the past few years, Chinese purchases of U.S. residential real estate have risen sharply, from $11.2 billion in 2010 to $31.7 billion in 2017. Chinese investors were the largest foreign purchases of U.S. residential restate buyers each year from 2015 to 2017. In 2017, Chinese investors purchased 40,572 properties.49

Bilateral Foreign Direct Investment Flows50

The level of foreign direct investment (FDI) flows between China and the United States is relatively small given the large volume of trade between the two countries. Many analysts contend that an expansion of bilateral FDI flows could greatly expand commercial ties.51 BEA data on U.S.-China FDI (see Table 7) indicate that in 2016

- U.S. FDI flows to China were $9.5 billion (up 28.2% over 2015 flows), making China the ninth-largest destination of U.S. FDI outflows.

- The stock of U.S. FDI in China on a historical-cost basis (i.e., the book value) was $92.5 billion (up 9.4% over the previous year), making China the 12th-largest overall destination of U.S. FDI through 2016.

- Chinese FDI flows to the United States were $10.3 billion (up 74.7% over 2015 levels), making China the 11th-largest source of U.S. FDI inflows in 2016.

At the end of 2016, the stock of Chinese FDI in the United States on a historical-cost basis, was $27.5 billion (up 63.7% over the previous year), making China the 16th-largest overall source of U.S. FDI through 2016.52

|

FDI Data |

Quantity ($millions) |

Ranking of FDI Flows |

|

|

U.S. FDI flows to China in 2016 |

9,474 |

|

|

|

China FDI flows to U.S. in 2016 |

10,337 |

|

|

|

Stock of U.S. FDI in China through 2016 |

92,481 |

|

|

|

Stock of Chinese FDI in U.S. through 2016 |

58,154 |

|

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Notes: FDI stock data are on a historical-cost basis. Rankings were made using only countries and exclude broad groupings of territories or islands. Data for China exclude Hong Kong and Macau which are counted separately.

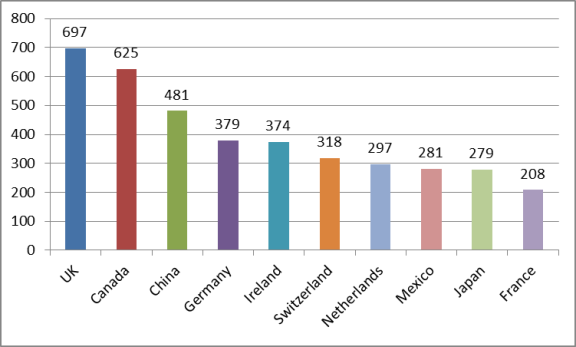

BEA also collects various financial data of foreign-invested multilateral firms. Data for 2015 (the most recent year available) indicate that sales by foreign affiliates of U.S. firms in China totaled $481 billion,53 which was the third-largest market for U.S.-affiliated firms overseas, after the United Kingdom ($697 billion) and Canada ($625 billion) (see Figure 12). In addition, U.S. affiliates in China employed 2.1 million workers, paid $35 billion in employment compensation, and spent $3.4 billion on R&D.54

|

Figure 12. Sales by Foreign Affiliates of U.S. Firms by Country in 2015 ($ in billions) |

|

|

Source: BEA. |

Alternative Measurements of Bilateral FDI Flows

The Rhodium Group (RG), a private consulting firm, estimates that Chinese FDI in the United States is significantly higher than BEA estimates. RG notes that "official data often exhibit a 1-2 year time lag and do not capture major trends, due to problems such as significant round tripping and trans-shipping of investments."55 The Rhodium Group's approach is to calculate the full value of a Chinese acquisition in the year it was made, attributing it to China if a Chinese entity is the investor, regardless of where the financing of the deal originated (such as through oft-used Hong Kong and Caribbean offshore centers). RG's data on U.S.-China FDI are significantly higher than BEA's data (see Figure 13, Figure 14, and Figure 15).56 To illustrate

- RG's data on the stock of Chinese FDI in the United States through 2016 ($110.1 billion), is 300.4% higher than BEA's data (at $27.5 billion).

- RG's estimate of the stock of U.S. FDI in China, at $242.6 billion, is 162.3% higher than BEA's estimate (at $92.5 billion).

- RG puts Chinese FDI flows to the United States in 2016 at $46.2 billion, which was 348.5% higher than BEA's data ($10.3 billion).

- RG's estimate of U.S. FDI flows to China in 2016, at $13.8 billion, was 45.3% higher than BEA's data ($9.5 billion).

Both BEA and RG data indicate a sharp increase in Chinese FDI flows to the United States in 2016 over the previous year. BEA's data show a 28.2% rise while RG's data indicate a 201.9% surge.

The Chinese government reports in 2017 that its global overseas nonfinancial FDI dropped by 29.4% over the same period in 2016.57 The RG's data of 2017 indicate that Chinese FDI flows to the United States in 2017 were $29.4 billion, a 36.4% decline over the previous year, RG estimates that during the first half of 2018, Chinese FDI in the United States totaled $1.8 billion, a 90% drop over the first half of 2017 and the lowest level in seven years.58 Some of the decline in China's overseas FDI appears to be largely driven by new Chinese policies to seek to increase scrutiny of proposed overseas investments to ensure that they are not "irrational or illegal." In February 2018, the Chinese government announced that it would take over Anbang Insurance Company (which owns the Waldorf Astoria in New York City and other U.S. properties) for a year because of illegal business practices that allegedly threatened the solvency of the company.59 Falling Chinese FDI in the United States may also be the result of closer scrutiny to proposed Chinese acquisitions of U.S. assets by U.S. officials.

The American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and the Heritage Foundation jointly maintain the China Global Investment Tracker database, which lists Chinese global investments of $100 million or more since 2005. Table 8 lists the 10 largest Chinese investments in the United States through 2017, which include HNA's purchase of CIT Group's aircraft leasing business for $10.4 billion; Shuanghui's (now called WH Group) purchase of Smithfield Foods for $7.1 billion; HNA's $6.5 billion investment in Hilton from Blackstone; HNA's purchase of Ingram Micro for $6 billion; and Anbang's $5.7 billion acquisition of hotel properties from Blackstone.

|

Year |

Investor |

Transaction Value ($millions) |

Share Size |

Transaction Party |

Sector |

|

2017 |

HNA |

10,380 |

CIT Group |

Transport |

|

|

2013 |

Shuanghui |

7,100 |

100% |

Smithfield Foods |

Agriculture |

|

2016 |

HNA |

6,500 |

25% |

Blackstone |

Tourism |

|

2016 |

HNA |

6,000 |

100% |

Ingram Micro |

Technology |

|

2016 |

Anbang |

5,720 |

Blackstone |

Tourism |

|

|

2016 |

Haier |

5,400 |

General Electric |

Other |

|

|

2007 |

CIC |

5,000 |

10% |

Morgan Stanley |

Finance |

|

2016 |

Dalian Wanda |

3,500 |

100% |

Legendary Entertainment |

Entertainment |

|

2016 |

Zhuhai Seine Technology and Legend |

3,400 |

Lexmark |

Technology |

|

|

2007 |

CIC |

3,030 |

9% |

Blackstone |

Finance |

Source: American Enterprise Institute and Heritage Foundation, China Global Investment Tracker.

Chinese Restrictions on U.S. FDI in China

U.S. trade officials have urged China to liberalize its FDI regime in order to boost U.S. business opportunities in, and expand U.S. exports to, China. Although China is one of the world's top recipients of FDI, the Chinese central government imposes numerous restrictions on the level and types of FDI allowed in China. According to the U.S.-China Business Council (USCBC), China imposes ownership barriers on nearly 100 industries.60 The OECD's 2016 FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index, which measures statutory restrictions on FDI in 62 countries, ranked China's FDI regime as the fourth most restrictive.61

Some recent surveys by U.S. and European business groups suggest that foreign firms in China may be less optimistic about the Chinese market than in the past, due in part to perceived growing protectionism. To illustrate:

- A 2017 American Chamber of Commerce in China (AmCham China) business climate survey of 500 member companies found that while a majority of respondents felt optimistic about their investments in China, 81% said that foreign businesses in China were less welcome in China than before, compared to 41% who asserted that in 2013. The survey found that 55% of respondents said that foreign firms are treated less favorably treated by the Chinese government than domestic Chinese firms.62

- A 2016 European Union Chamber of Commerce in China business confidence survey stated that the business environment in China was becoming "increasingly hostile" and "perpetually tilted in favor of domestic enterprises." For example, among respondents, 56% said doing business in China was becoming more difficult and 57% claimed foreign companies tend to receive unfavorable treatment in China compared to domestic Chinese firms.63

Negotiations for a Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT)64

The United States and China initiated negotiations on reaching a bilateral investment treaty (BIT) in 2008, with the goal of expanding bilateral investment opportunities. U.S. negotiators hoped such a treaty, if implemented, would improve the investment climate for U.S. firms in China by enhancing legal protections and dispute resolution procedures, and by obtaining a commitment from the Chinese government that it would treat U.S. investors no less favorably than Chinese investors.

In April 2012, the Obama Administration released a "Model Bilateral Investment Treaty" that was developed to enhance U.S. objectives in the negotiation of new BITs.65 The new model BIT addressed six core principles or issues for investors, including national treatment and most-favored nation (MFN) treatment at all stages of investment, rules on expropriations and compensation if this occurs, ability to transfer funds in and out of the country, limits on performance requirements (such as domestic content targets or mandated technology transfer), neutral arbitration of disputes, and freedom by investors to appoint their own senior officials.66

During the July 10-11, 2013 session of the U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue (S&ED), China indicated its intention to negotiate a high-standard BIT with the United States that would include all stages of investment and all sectors, a commitment a U.S. official described as "a significant breakthrough, and the first time China has agreed to do so with another country."67 A press release by the Chinese Ministry of Commerce stated that China was willing to negotiate a BIT on the basis of nondiscrimination and a negative list, meaning the agreement would identify only those sectors not open to foreign investment on a nondiscriminatory basis (as opposed to a BIT with a positive list which would only list sectors open to foreign investment).

During the July 9-10, 2014 S&ED session, the two sides agreed to a broad timetable for reaching agreement on core issues and major articles of the treaty text, and committed to initiate the "negative list" negotiation early in 2015.68 During BIT negotiations held in June 2015, each side submitted their first negative list proposals, and later agreed to submit a revised list in September 2015 right before President Xi's summit visit to the United States, which they did, but a breakthrough was not achieved. New negative lists were submitted in June 2016 and August 2016,69 and the BIT was discussed at the September 2016 G-20 Summit held in Hangzhou, China, but no breakthrough was announced.

Many analysts contend that a U.S.-China BIT could have significant implications for bilateral commercial relations and the Chinese economy. According to then-USTR Michael Froman, such an agreement "offers a major opportunity to engage on China's domestic economic reforms and to pursue greater market access, a more level playing field, and a substantially improved investment environment for U.S. firms in China."70 For China, a high-standard BIT could help facilitate greater competition in China and result in a more efficient use of resources, factors which economists contend could boost economic growth. Some observers contend that China's pursuit of a BIT with the United States represents a strategy that is being used by reformers in China to jumpstart widespread economic reforms (which appear to have stalled in recent years). This strategy, it is argued, is similar to that used by Chinese reformers in their efforts to get China into the WTO in 2001. Such international agreements may give political cover to economic reformers because they can argue that the agreements build on China's efforts to become a leader in global affairs. This may make it harder for vested interests in China who benefit from the status quo to resist change. Some critics raise concerns that even if a high standard BIT is reached, ensuring China's full compliance may prove difficult, given China's extensive use of industrial policies. Others have raised questions as to the effect of such an agreement in boosting FDI flows and how that might impact U.S. jobs in affected industries.71 A BIT would have to be approved in the U.S. Senate by a two-thirds majority.

The BIT was not concluded by the end of the Obama Administration's term (the original goal of completion). While the Chinese government has indicated that it supports continuing BIT negotiations, the Trump Administration has been less clear on its position. U.S. Secretary of Treasury Steven Mnuchin was quoted by Inside Trade in June 2017 as saying:

It's on our agenda; I wouldn't say it's at the very top of our agenda. I think what we're looking for is, opposed to just negotiating a large agreement, we're looking to negotiate very specific issues that deal with market issues today, deal with market fairness today, deal with opening their markets to the same extent that our markets are open, and that's really our focus.... Once we can make progress in that we can turn to the bilateral investment treaty.72

The U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission's (USCC's) November 2015 annual report recommended that the Administration provide a comprehensive, publicly available assessment of Chinese FDI in the United States prior to completion of BIT negotiations that includes an identification of the nature of investments, whether investments received support of any kind from the Chinese government and at any level, and the sector in which the investment was made.73 The USCC's 2016 annual report recommended that Congress should "amend the statute authorizing the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States to bar Chinese state-owned enterprises from acquiring or otherwise gaining effective control of U.S. companies."74

Concerns About Chinese FDI in the United States

Chinese FDI in the United States has come under increasing scrutiny by U.S. policymakers. Some have expressed concerns over Chinese investments (especially by SOEs or government-backed entities) that appear to target industries and technologies that the Chinese government has identified as critical to China's future economic development. Some have called for reforms to the process in which the Federal government evaluates certain FDI, such as the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), an interagency committee that reviews the national security aspects of certain foreign acquisitions, seek to modify the terms of the proposed acquisition, and makes recommendations to the President, who can block the transaction.75

The USCC's 2017 Annual Report identified three trends that may impact the ability of CFIUS to review Chinese investment in the United States, including China's targeting investments in industries it deems as strategic, the use of private entities as fronts by the Chinese government SOEs to obtain assets in strategic sectors; and attempting to bypass U.S. regulatory procedures (such as investing through shell companies outside China) and using cyber-espionage to financially undermine the targeted firm before acquiring it.76 The commission made a number of recommendations to Congress on Chinese investment in the United States, including a ban on acquisition of U.S. assets by Chinese state-owned or state-controlled entities, including sovereign wealth funds.

In September 2017, President Trump, citing national security concerns, blocked the acquisition of the U.S. firm Lattice Semiconductor by China Venture Capital Fund Corporation Limited77 for $1.3 billion.78 In March 2018, national security concerns were also used by President Trump when he blocked a bid to purchase Qualcomm Incorporated (a U.S. high-technology firm) to Broadcom Limited (a semiconductor firm headquartered in Singapore). The decision to block the sale appears to have been motivated in part by concerns it would weaken Qualcomm's position and enable China to, according to CFIIUS, dominate 5G technology and the standards setting process.79

Some Members of Congress argue that the structure and scope of CFIUS needs to modernized and strengthened in order to close loopholes that may exist in the current system for certain types of foreign investments. Several CFIUS bills have been introduced in Congress, many of which be appear to be largely aimed at Chinese FDI activities. For example, a press release by Representative Pittenger for his introduction of H.R. 4311 (the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2017) stated

China is buying American companies at a breathtaking pace. While some are legitimate business investments, many others are part of a backdoor effort to compromise U.S. national security.... For example, China recently attempted to purchase a U.S. missile defense supplier using a shell company to evade detection. The global economy presents new security risks, and so our bipartisan legislation provides Washington the necessary tools to better track and evaluate Chinese investment.80

Some CFIUS reform bills have been taken up by Congress, including H.R. 5841 (the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018, introduced by Representative Pittenger), which passed the House on June 26, 2018); and S. 2098 (the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018, introduced by Senator Cornyn), which was added as an amendment by the Senate to H.R. 5515 (the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019) and passed by the Senate on June 18.81There is also support by some in Congress to modernize and reform U.S. export control laws, such as H.R. 5040 (the Export Control Reform Act of 2018).82 The Trump Administration had indicated under its Section 301 investigation of China's IPR policies that it would to impose new FDI restrictions and tighter export controls against China. However, on June 27, President Trump announced that legislation currently under consideration in Congress to reform CFIUS and export control laws would, if enacted, meet the Administration's goals on these issues.83

Major U.S.-China Trade Issues

China's economic reforms and rapid economic growth, along with the effects of globalization, have caused the economies of the United States and China to become increasingly integrated.84 Although growing U.S.-China economic ties are considered by most analysts to be mutually beneficial overall, tensions have risen over a number of Chinese economic and trade policies that many U.S. critics charge are protectionist, economically distortive, and damaging to U.S. economic interests. According to the USTR, most U.S. trade disputes with China stem from the consequences of its incomplete transition to a free market economy. Major areas of concern for U.S. stakeholders include China's

- Extensive network of industrial policies (including widespread use of trade and investment barriers, financial support, and indigenous innovation policies) that seek to promote and protect domestic sectors and firms, especially SOEs, deemed by the government to be critical to the country's future economic growth;

- Failure to provide adequate protection of U.S. intellectual property rights (IPR) and (alleged) widespread government-directed cyber-theft of U.S. trade secrets security to help Chinese firms;

- Mixed record on implementing its WTO obligations; and

- Government-directed financial policies that promote high savings (but reduce private consumption), encourage high fixed investment levels (but may contribute to overcapacity in many industries), and a managed exchange rate policy that may distort trade flows.

Chinese "State Capitalism"

Currently, a significant share of China's economy is thought to be driven by market forces. A 2010 WTO report estimated that the private sector now accounted for more than 60% of China's gross domestic product (GDP).85 A 2016 WTO study estimated that the private sector accounted for 41.8% of China's exports.86

However, the Chinese government continues to play a major role in economic decision-making. For example, at the macroeconomic level, the Chinese government maintains policies that induce households to save a high level of their income, much of which is deposited in state-controlled Chinese banks. This enables the government to provide low-cost financing to Chinese firms, especially SOEs. At the microeconomic level, the Chinese government (at the central and local government level) seeks to promote the development of industries deemed critical to the country's future economic development by using various policies, such as subsidies, tax breaks, preferential loans, trade barriers, FDI restrictions, discriminatory regulations and standards, export restrictions on raw materials (including rare earths), technology transfer requirements imposed on foreign firms, public procurement rules that give preferences to domestic firms, and weak enforcement of IPR laws.

Many analysts argue that the Chinese government's intervention in various sectors through industrial policies has intensified in recent years. The December 2013 USTR report on China's WTO trade compliance stated

During most of the past decade, the Chinese government emphasized the state's role in the economy, diverging from the path of economic reform that had driven China's accession to the WTO. With the state leading China's economic development, the Chinese government pursued new and more expansive industrial policies, often designed to limit market access for imported goods, foreign manufacturers and foreign service suppliers, while offering substantial government guidance, resources and regulatory support to Chinese industries, particularly ones dominated by state-owned enterprises. This heavy state role in the economy, reinforced by unchecked discretionary actions of Chinese government regulators, generated serious trade frictions with China's many trade partners, including the United States.87

The extent of SOE involvement in the Chinese economy is difficult to measure, due to the opaque nature of the corporate sector in China and the relative lack of transparency regarding the relationship between state actors (including those at the central and noncentral government levels) and Chinese firms. According to one study by the USCC

The state sector in China consists of three main components. First, there are enterprises fully owned by the state through the State-owned Assets and Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) of the State Council and by SASACs of provincial, municipal, and county governments. Second, there are SOEs that are majority owners of enterprises that are not officially considered SOEs but are effectively controlled by their SOE owners. Finally, there is a group of entities, owned and controlled indirectly through SOE subsidiaries based inside and outside of China. The actual size of this third group is unknown. Urban collective enterprises and Government-owned Township and village enterprises (TVEs) also belong to the state sector but are not considered SOEs. The state-owned and controlled portion of the Chinese economy is large. Based on reasonable assumptions, it appears that the visible state sector—SOEs and entities directly controlled by SOEs, accounted for more than 40 percent of China's nonagricultural GDP. If the contributions of indirectly controlled entities, urban collectives, and public TVEs are considered, the share of GDP owned and controlled by the state is approximately 50 percent.88

According to the Chinese government, there are 150,000 state-owned or state-controlled enterprises at the central and local government excluding financial institutions, with total assets worth $15.2 trillion, and 30 million workers.89 Chinese SOEs have undergone significant restructuring over the years. The government contends that 68% of all SOE-funded firms in 2016 were mixed-ownership. The Chinese government has identified a number of industries where the state should have full control or where the state should dominate. These include autos, aviation, banking, coal, construction, environmental technology, information technology, insurance, media, metals (such as steel), oil and gas, power, railways, shipping, telecommunications, and tobacco.90

Many SOEs are owned or controlled by local governments. According to one analyst

The typical large industrial Chinese company is ...wholly or majority-owned by a local government which appoints senior management and provides free or low-cost land and utilities, tax breaks, and where possible, guarantees that locally made products will be favored by local governments, consumers, and other businesses. In return, the enterprise provides the local state with a source of jobs for local workers, tax revenues, and dividends.91

China's banking system is largely dominated by state-owned or state-controlled banks. In 2011, the top five largest banks in China, all of which were shareholding companies with significant state ownership, accounted for 57.5% of Chinese banking assets. The Chinese government also has four banks that are 100% state-owned and holds shares in a number of joint stock commercial banks.92 SOEs are believed to receive preferential credit treatment by government banks, while private firms must often pay higher interest rates or obtain credit elsewhere. According to one estimate, SOEs accounted for 85% ($1.4 trillion) of all bank loans in 2009.93

Not only are SOEs dominant players in China's economy, many are quite large by global standards. Fortune's 2018 list of the world's 500 largest companies includes 111 Chinese firms (compared to 29 listed firms in 2007), the top 20 of which are listed in Table 9.94

|

Company |

Global 500 Rank |

State or Nonstate |

Industry |

Revenue ($billions) |

|

State Grid |

2 |

State |

Utility |

349 |

|

Sinopec Group |

3 |

State |

Energy |

327 |

|

China National Petroleum |

4 |

State |

Energy |

326 |

|

China State Construction Engineering |

23 |

State |

Engineering & Construction |

156 |

|

Industrial & Commercial Bank of China |

26 |

State |

Banking |

153 |

|

Ping An Insurance |

29 |

Nonstate |

Insurance |

144 |

|

China Construction Bank |