The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS)

The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) is an interagency body comprised of nine Cabinet members, two ex officio members, and other members as appointed by the President, that assists the President in reviewing the national security aspects of foreign direct investment in the U.S. economy. While the group often operated in relative obscurity, the perceived change in the nation’s national security and economic concerns following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and the proposed acquisition of commercial operations at six U.S. ports by Dubai Ports World in 2006 placed CFIUS’s review procedures under intense scrutiny by Members of Congress and the public. In 2018, prompted by concerns over Chinese and other foreign investment in U.S. companies with advanced technology, Members of Congress and the Trump Administration enacted the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 (FIRRMA), which became effective on November 11, 2018. This measure marked the most comprehensive revision of the foreign investment review process under CFIUS since the previous revision in 2007, the Foreign Investment and National Security Act (FINSA). On February 13, 2020, the Department of the Treasury issued final regulations, including implementing key parts of FIRRMA concerning how investments in “critical technologies,” “critical infrastructure,” sensitive personal data, and certain real estate and noncontrolling investments will be scrutinized

Generally, efforts to amend CFIUS have been spurred by a specific foreign investment transaction that raised national security concerns. Despite various changes to the CFIUS statute, some Members and others question the nature and scope of CFIUS reviews. The CFIUS process is governed by statute that sets a legal standard for the President to suspend or block a transaction if no other laws apply and if there is “credible evidence” that the transaction threatens to impair the national security, which is interpreted as transactions that pose a national security risk.

The U.S. policy approach to international investment traditionally established and supported an open and rules-based trading system that is in line with U.S. economic and national security interests. Recent debate over CFIUS reflects long-standing concerns about the impact of foreign investment on the economy and the role of economics as a component of national security. Some Members question CFIUS’s performance and the way the Committee reviews cases involving foreign governments, particularly with the emergence of state-owned enterprises, and acquisitions involving leading-edge or foundational technologies. Recent changes expand CFIUS’s purview to include a broader focus on the economic implications of individual foreign investment transactions and the cumulative effect of foreign investment on certain sectors of the economy or by investors from individual countries.

Changes in U.S. foreign investment policy have potentially large economy-wide implications, since the United States is the largest recipient and the largest overseas investor of foreign direct investment. To date, five investments have been blocked, although proposed transactions may have been withdrawn by the firms involved in lieu of having a transaction blocked. President Obama used the FINSA authority in 2012 to block an American firm, Ralls Corporation, owned by Chinese nationals, from acquiring a U.S. wind farm energy firm located near a Department of Defense (DOD) facility and to block a Chinese investment firm in 2016 from acquiring Aixtron, a Germany-based firm with assets in the United States. In 2017, President Trump blocked the acquisition of Lattice Semiconductor Corp. by the Chinese investment firm Canyon Bridge Capital Partners; in 2018, he blocked the acquisition of Qualcomm by Broadcom; and in 2019, the Committee raised concerns over Beijing Kunlun Company’s investment in Grindr LLC, an online dating site, over concerns of foreign access to personally identifiable information of U.S. citizens. Subsequently, the Chinese firm divested itself of Grindr. Given the number of regulatory changes mandated by FIRRMA, Congress may well conduct oversight hearings to determine the status of the changes and their implications.

The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS)

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Background

- The Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 (FIRRMA)

- Foreign Investment Data

- Origins of CFIUS

- Establishment of CFIUS

- The "Exon-Florio" Provision

- Treasury Department Regulations

- The "Byrd Amendment"

- Recent Legislative Reforms

- FIRRMA Legislation: Key Provisions

- CFIUS: Major Provisions

- National Security Reviews

- Informal Actions

- Formal Actions

- National Security Review

- National Security Investigation

- Presidential Determination

- Committee Membership

- Covered Transactions

- Foreign Ownership Control

- Factors for Consideration

- Confidentiality Requirements

- Mitigation and Tracking

- Funding and Staff Requirements

- Congressional Oversight

- Recent CFIUS Reviews

- Issues for Congress

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. Selected Indicators of International Investment and Production, 2011-2017

- Table 2. Foreign Investment Transactions Reviewed by CFIUS, 2009-2017

- Table 3. Industry Composition of Foreign Investment Transactions Reviewed by CFIUS, 2009-2017

- Table 4. Country of Foreign Investor and Industry Reviewed by CFIUS, 2015-2017

- Table 5. Home Country of Foreign Acquirer of U.S. Critical Technology, 2016-2017

Summary

The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) is an interagency body comprised of nine Cabinet members, two ex officio members, and other members as appointed by the President, that assists the President in reviewing the national security aspects of foreign direct investment in the U.S. economy. While the group often operated in relative obscurity, the perceived change in the nation's national security and economic concerns following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and the proposed acquisition of commercial operations at six U.S. ports by Dubai Ports World in 2006 placed CFIUS's review procedures under intense scrutiny by Members of Congress and the public. In 2018, prompted by concerns over Chinese and other foreign investment in U.S. companies with advanced technology, Members of Congress and the Trump Administration enacted the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 (FIRRMA), which became effective on November 11, 2018. This measure marked the most comprehensive revision of the foreign investment review process under CFIUS since the previous revision in 2007, the Foreign Investment and National Security Act (FINSA). On February 13, 2020, the Department of the Treasury issued final regulations, including implementing key parts of FIRRMA concerning how investments in "critical technologies," "critical infrastructure," sensitive personal data, and certain real estate and noncontrolling investments will be scrutinized

Generally, efforts to amend CFIUS have been spurred by a specific foreign investment transaction that raised national security concerns. Despite various changes to the CFIUS statute, some Members and others question the nature and scope of CFIUS reviews. The CFIUS process is governed by statute that sets a legal standard for the President to suspend or block a transaction if no other laws apply and if there is "credible evidence" that the transaction threatens to impair the national security, which is interpreted as transactions that pose a national security risk.

The U.S. policy approach to international investment traditionally established and supported an open and rules-based trading system that is in line with U.S. economic and national security interests. Recent debate over CFIUS reflects long-standing concerns about the impact of foreign investment on the economy and the role of economics as a component of national security. Some Members question CFIUS's performance and the way the Committee reviews cases involving foreign governments, particularly with the emergence of state-owned enterprises, and acquisitions involving leading-edge or foundational technologies. Recent changes expand CFIUS's purview to include a broader focus on the economic implications of individual foreign investment transactions and the cumulative effect of foreign investment on certain sectors of the economy or by investors from individual countries.

Changes in U.S. foreign investment policy have potentially large economy-wide implications, since the United States is the largest recipient and the largest overseas investor of foreign direct investment. To date, five investments have been blocked, although proposed transactions may have been withdrawn by the firms involved in lieu of having a transaction blocked. President Obama used the FINSA authority in 2012 to block an American firm, Ralls Corporation, owned by Chinese nationals, from acquiring a U.S. wind farm energy firm located near a Department of Defense (DOD) facility and to block a Chinese investment firm in 2016 from acquiring Aixtron, a Germany-based firm with assets in the United States. In 2017, President Trump blocked the acquisition of Lattice Semiconductor Corp. by the Chinese investment firm Canyon Bridge Capital Partners; in 2018, he blocked the acquisition of Qualcomm by Broadcom; and in 2019, the Committee raised concerns over Beijing Kunlun Company's investment in Grindr LLC, an online dating site, over concerns of foreign access to personally identifiable information of U.S. citizens. Subsequently, the Chinese firm divested itself of Grindr. Given the number of regulatory changes mandated by FIRRMA, Congress may well conduct oversight hearings to determine the status of the changes and their implications.

Background

The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) is an interagency committee that serves the President in overseeing the national security implications of foreign direct investment (FDI) in the economy. Since its inception, CFIUS has operated at the nexus of shifting concepts of national security and major changes in technology, especially relative to various notions of national economic security, and a changing global economic order that is marked in part by emerging economies such as China that are playing a more active role in the global economy. As a basic premise, the U.S. historical approach to international investment has aimed to establish an open and rules-based international economic system that is consistent across countries and in line with U.S. economic and national security interests. This policy also has fundamentally maintained that FDI has positive net benefits for the U.S. and global economy, except in certain cases in which national security concerns outweigh other considerations and for prudential reasons. The Committee's annual report issued in December 2019 indicates that CFIUS has increased the average annual number of investigations it has conducted.1

Recently, some policymakers argued that certain foreign investment transactions, particularly by entities owned or controlled by a foreign government, investments with leading-edge or foundational technologies, or investments that may compromise personally identifiable information, are affecting U.S. national economic security. As a result, they supported greater CFIUS scrutiny of foreign investment transactions, including a mandatory approval process for some transactions. Some policymakers also argued that the CFIUS review process should have a more robust economic component, possibly even to the extent of an industrial policy-type approach that uses the CFIUS national security review process to protect and promote certain industrial sectors in the economy. Others argued, however, that the CFIUS review process should be expanded to include certain transactions that had not previously been reviewed, but that CFIUS' overall focus should remain fairly narrow.

The Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 (FIRRMA)

In 2018, Congress and the Trump Administration adopted the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 (FIRRMA), Subtitle A of Title XVII of P.L. 115-232 (August 13, 2018), which became effective on November 11, 2018.2 The impetus for FIRRMA was based on concerns that ''the national security landscape has shifted in recent years, and so has the nature of the investments that pose the greatest potential risk to national security ....''3 As a result, FIRRMA provided for some programs to become effective upon passage, while a pilot program was developed to address immediate concerns relative to other provisions and allow time for additional resources to be directed at developing a more permanent response in these areas. Interim rules for the pilot program developed by the Treasury Department covered two provisions of FIRRMA. First was an expanded scope of transactions subject to a review by CFIUS including noncontrolling investments by foreign persons in U.S. firms involved in critical technologies, critical infrastructure, and personal data related to specified industries and industrial sectors. A second part of the pilot program implemented FIRRMA's mandatory declarations provision for all transactions that fall within the specific scope of the pilot program. The pilot program became effective February 13, 2020; provisions requiring a mandatory filing under the pilot program were made permanent and the regulations provided for all firms to have the option of using the short-form voluntary declaration.4 Previously, the Treasury Department had issued final regulations, which became effective February 13, 2020, concerning the review process for certain real estate and noncontrolling investments.

Upon enactment, FIRRMA: (1) expanded the scope and jurisdiction of CFIUS by redefining such terms as "covered transactions" and "critical technologies"; (2) refined CFIUS procedures, including timing for reviews and investigations; and (3) required actions by CFIUS to address national security risks related to mitigation agreements, among other areas. Treasury's interim rules updated and amended existing regulations in order to implement certain provisions immediately. FIRRMA also required CFIUS to take certain actions within prescribed deadlines for various programs, reporting, and other plans.

FIRRMA also broadened CFIUS' mandate by explicitly including for review certain real estate transactions in close proximity to a military installation or U.S. government facility or property of national security sensitivities. In addition, FIRRMA provides for CFIUS to review: (1) any noncontrolling investment in U.S. businesses involved in critical technology, critical infrastructure, or collecting sensitive data on U.S. citizens; (2) any change in foreign investor rights; (3) transactions in which a foreign government has a direct or indirect substantial interest (defined below); and (4) any transaction or arrangement designed to evade CFIUS. Through a "sense of Congress" provision in FIRRMA, CFIUS reviews potentially can discriminate among investors from certain countries that are determined to be a country of "special concern" (specified through additional regulations) that has a "demonstrated or declared strategic goal of acquiring a type of critical technology or critical infrastructure that would affect U.S. leadership in areas related to national security."5

Foreign Investment Data

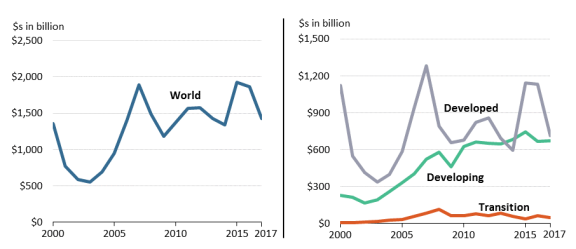

Information on international investment and production collected and published by the United Nations indicates that global annual inflows of FDI peaked in 2015, surpassing the previous record set in 2007, but has fallen since, as indicated in Figure 1. Similarly, from 2012 through 2014, international flows of FDI fell below the levels reached prior to the 2008-2009 financial crisis, but revived in 2015. Between 2015 and 2017, FDI inflows fell by nearly $500 million to $1.4 billion, largely reflecting lower inflows to developed economies as a result of a 22% decline in cross-border merger and acquisition activity (M&As).

FDI inflows to developing economies also declined, but at a slower rate than among flows to developed economies, while investment flows to economies in transition continued to increase at a steady pace. Other cross-border capital flows (portfolio investments and bank loans) continued at a strong pace in 2017, contrary to the trend in direct investment. Globally, the foreign affiliates of international firms employed 73 million people in 2017, as indicted in Table 1. Globally, the stock, or cumulative amount, of FDI in 2017 totaled about $31 trillion. Other measures of international production, sales, assets, value-added production, and exports generally indicate higher nominal values in 2017 than in the previous year, providing some indication that global economic growth was recovering.

|

Figure 1. Foreign Direct Investment, Annual Inflows, World and Major Country Groups ($ in billions) |

|

|

Source: World Investment Report, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. |

According to the United Nations,6 the global FDI position in the United States, or the cumulative amount of inward foreign direct investment, was recorded at around $7.8 trillion in 2017, with the U.S. outward FDI position of about $7.9 trillion. The next closest country in investment position to the United States was Hong Kong with inward and outward investment positions of about one-fourth that of the United States. In comparison, the 28 counties comprising the European Union (EU) had an inward investment position of $9.1 trillion in 2017 and an outward position of $10.6 trillion.

|

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

||||||||

|

FDI inflows |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

FDI outflows |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

FDI inward stock |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

FDI outward stock |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Cross-border M&As (number) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Sales of foreign affiliates |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Value-added (product) of foreign affiliates |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Total assets of foreign affiliates |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Exports of foreign affiliates |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

GDP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

|

Employment by foreign affiliates (thousands) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: World Investment Report, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, June 2018.

Origins of CFIUS

Established by an executive order of President Ford in 1975, CFIUS initially operated in relative obscurity.7 According to a Treasury Department memorandum, the Committee was established in order to "dissuade Congress from enacting new restrictions" on foreign investment, as a result of growing concerns over the rapid increase in investments by Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) countries in American portfolio assets (Treasury securities, corporate stocks and bonds), and to respond to concerns of some that much of the OPEC investments were being driven by political, rather than by economic, motives.8

Thirty years later in 2006, public and congressional concerns about the proposed purchase of commercial port operations of the British-owned Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O)9 in six U.S. ports by Dubai Ports World (DP World)10 sparked a firestorm of criticism and congressional activity during the 109th Congress concerning CFIUS and the manner in which it operated. As a result of attention from the public and Congress, DP World officials decided to sell off the U.S. port operations to an American owner.11 On December 11, 2006, DP World officials announced that a unit of AIG Global Investment Group, a New York-based asset management company with large assets, but no experience in port operations, had acquired the U.S. port operations for an undisclosed amount.12

The DP World transaction revealed that the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks fundamentally altered the viewpoint of some Members of Congress regarding the role of foreign investment in the economy and the potential impact of such investment on U.S. national security. Some Members argued that this change in perspective required a reassessment of the role of foreign investment in the economy and of the implications of corporate ownership on activities that fall under the rubric of critical infrastructure. The emergence of state-owned enterprises as commercial economic actors has raised additional concerns about whose interests and whose objectives such firms are pursuing in their foreign investment activities.

More than 25 bills were introduced in the second session of the 109th Congress that addressed various aspects of foreign investment following the proposed DP World transaction. In the first session of the 110th Congress, Congress passed, and President Bush signed, the Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007 (FINSA) (P.L. 110-49), which altered the CFIUS process in order to enable greater oversight by Congress and increased transparency and reporting by the Committee on its decisions. In addition, the act broadened the definition of national security and required greater scrutiny by CFIUS of certain types of foreign direct investment. Not all Members were satisfied with the law: some Members argued that the law remained deficient in reviewing investment by foreign governments through sovereign wealth funds (SWFs). Also left unresolved were issues concerning the role of foreign investment in the nation's overall security framework and the methods that are used to assess the impact of foreign investment on the nation's defense industrial base, critical infrastructure, and homeland security.

Establishment of CFIUS

President Ford's 1975 executive order established the basic structure of CFIUS, and directed that the "representative"13 of the Secretary of the Treasury be the chairman of the Committee. The executive order also stipulated that the Committee would have "the primary continuing responsibility within the executive branch for monitoring the impact of foreign investment in the United States, both direct and portfolio, and for coordinating the implementation of United States policy on such investment." In particular, CFIUS was directed to (1) arrange for the preparation of analyses of trends and significant developments in foreign investment in the United States; (2) provide guidance on arrangements with foreign governments for advance consultations on prospective major foreign governmental investment in the United States; (3) review investment in the United States which, in the judgment of the Committee, might have major implications for U.S. national interests; and (4) consider proposals for new legislation or regulations relating to foreign investment as may appear necessary.14

President Ford's executive order also stipulated that information submitted "in confidence shall not be publicly disclosed" and that information submitted to CFIUS be used "only for the purpose of carrying out the functions and activities" of the order. In addition, the Secretary of Commerce was directed to perform a number of activities, including

(1) Obtaining, consolidating, and analyzing information on foreign investment in the United States;

(2) Improving the procedures for the collection and dissemination of information on such foreign investment;

(3) Observing foreign investment in the United States;

(4) Preparing reports and analyses of trends and of significant developments in appropriate categories of such investment;

(5) Compiling data and preparing evaluation of significant transactions; and

(6) Submitting to the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States appropriate reports, analyses, data, and recommendations as to how information on foreign investment can be kept current.

|

CFIUS Legislative History 1975 CFIUS established by executive order. 1988 "Exon-Florio" amendment to Defense Production Act. Codified the process CFIUS used to review foreign investment transactions. 1992 "Byrd Amendment" to Defense Production Act. Required reviews in cases where foreign acquirer was acting on or in behalf of a foreign government. 2007 Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007 replaced executive order and codified CFIUS. 2018 Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 provided a comprehensive reform of the CFIUS process. |

The executive order, however, raised questions among various observers and government officials who doubted that federal agencies had the legal authority to collect the types of data that were required by the order. As a result, Congress and the President sought to clarify this issue, and in the following year President Ford signed the International Investment Survey Act of 1976.15 The act gave the President "clear and unambiguous authority" to collect information on "international investment." In addition, the act authorized "the collection and use of information on direct investments owned or controlled directly or indirectly by foreign governments or persons, and to provide analyses of such information to the Congress, the executive agencies, and the general public."16

By 1980, some Members of Congress raised concerns that CFIUS was not fulfilling its mandate. Between 1975 and 1980, for instance, the Committee met only 10 times and seemed unable to decide whether it should respond to the political or the economic aspects of foreign direct investment in the United States.17 One critic of the Committee argued in a congressional hearing in 1979 that, "the Committee has been reduced over the last four years to a body that only responds to the political aspects or the political questions that foreign investment in the United States poses and not with what we really want to know about foreign investments in the United States, that is: Is it good for the economy?"18

From 1980 to 1987, CFIUS investigated a number of foreign investment transactions, mostly at the request of the Department of Defense. In 1983, for instance, a Japanese firm sought to acquire a U.S. specialty steel producer. The Department of Defense subsequently classified the metals produced by the firm because they were used in the production of military aircraft, which caused the Japanese firm to withdraw its offer. Another Japanese company attempted to acquire a U.S. firm in 1985 that manufactured specialized ball bearings for the military. The acquisition was completed after the Japanese firm agreed that production would be maintained in the United States. In a similar case in 1987, the Defense Department objected to a proposed acquisition of the computer division of a U.S. multinational company by a French firm because of classified work conducted by the computer division. The acquisition proceeded after the classified contracts were reassigned to the U.S. parent company.19

The "Exon-Florio" Provision

In 1988, amid concerns over foreign acquisition of certain types of U.S. firms, particularly by Japanese firms, Congress approved the Exon-Florio amendment to the Defense Production Act, which specified the basic review process of foreign investments.20 The statute granted the President the authority to block proposed or pending foreign "mergers, acquisitions, or takeovers" of "persons engaged in interstate commerce in the United States" that threatened to impair the national security. Congress directed, however, that the President could invoke this authority only after he had concluded that (1) other U.S. laws were inadequate or inappropriate to protect the national security; and (2) "credible evidence" existed that the foreign interest exercising control might take action that threatened to impair U.S. national security. This same standard was maintained in an update to the Exon-Florio provision in 2007, the Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007, and in FIRRMA.

After three years of often contentious negotiations between Congress and the Reagan Administration, Congress passed and President Reagan signed the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988.21 During consideration of the Exon-Florio proposal as an amendment to the omnibus trade bill, debate focused on three controversial issues: (1) what constitutes foreign control of a U.S. firm? (2) how should national security be defined? and (3) which types of economic activities should be targeted for a CFIUS review? Of these issues, the most controversial and far-reaching was the lack of a definition of national security. As originally drafted, the provision would have considered investments which affected the "national security and essential commerce" of the United States. The term "essential commerce" was the focus of intense debate between Congress and the Reagan Administration.

The Treasury Department, headed by Secretary James Baker, objected to the Exon-Florio amendment, and the Administration vetoed the first version of the omnibus trade legislation, in part due to its objections to the language in the measure regarding "national security and essential commerce." The Reagan Administration argued that the language would broaden the definition of national security beyond the traditional concept of military/defense to one that included a strong economic component. Administration witnesses argued against this aspect of the proposal and eventually succeeded in prodding Congress to remove the term "essential commerce" from the measure and narrow substantially the factors the President must consider in his determination.

The final Exon-Florio provision was included as Section 5021 of the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988. The provision originated in bills reported by the Commerce Committee in the Senate and the Energy and Commerce Committee in the House, but the measure was transferred to the Senate Banking Committee as a result of a dispute over jurisdictional responsibilities.22 Through Executive Order 12661, President Reagan implemented provisions of the Omnibus Trade Act. In the executive order, President Reagan delegated his authority to administer the Exon-Florio provision to CFIUS,23 particularly to conduct reviews, undertake investigations, and make recommendations, although the statute itself does not specifically mention CFIUS. As a result of President Reagan's action, CFIUS was transformed from an administrative body with limited authority to review and analyze data on foreign investment to an important component of U.S. foreign investment policy with a broad mandate and significant authority to advise the President on foreign investment transactions and to recommend that some transactions be suspended or blocked.

In 1990, President Bush directed the China National Aero-Technology Import and Export Corporation (CATIC) to divest its acquisition of MAMCO Manufacturing, a Seattle-based firm producing metal parts and assemblies for aircraft, because of concerns that CATIC might gain access to technology through MAMCO that it would otherwise have to obtain under an export license.24

Part of Congress's motivation in adopting the Exon-Florio provision apparently arose from concerns that foreign takeovers of U.S. firms could not be stopped unless the President declared a national emergency or regulators invoked federal antitrust, environmental, or securities laws. Through the Exon-Florio provision, Congress attempted to strengthen the President's hand in conducting foreign investment policy, while limiting its own role as a means of emphasizing that, as much as possible, the commercial nature of investment transactions should be free from political considerations. Congress also attempted to balance public concerns about the economic impact of certain types of foreign investment with the nation's long-standing international commitment to maintaining an open and receptive environment for foreign investment.

Furthermore, Congress did not intend to have the Exon-Florio provision alter the generally open foreign investment climate of the country or to have it inhibit foreign direct investment in industries that could not be considered to be of national security interest. At the time, some analysts believed the provision could potentially widen the scope of industries that fell under the national security rubric. CFIUS, however, is not free to establish an independent approach to reviewing foreign investment transactions, but operates under the authority of the President and reflects his attitudes and policies. As a result, the discretion CFIUS uses to review and to investigate foreign investment cases reflects policy guidance from the President. Foreign investors also are constrained by legislation that bars foreign direct investment in such industries as maritime, aircraft, banking, resources, and power. Generally, these sectors were closed to foreign investors prior to passage of the Exon-Florio provision in order to prevent public services and public interest activities from falling under foreign control, primarily for national defense purposes.

Treasury Department Regulations

After extensive public comment, the Treasury Department issued its final regulations in November 1991 implementing the Exon-Florio provision.25 Although these procedures were amended through FINSA, they continued to serve as the basis for the Exon-Florio review and investigation until new regulations were released on November 21, 2008.26 These regulations created an essentially voluntary system of notification by the parties to an acquisition, and they allowed for notices of acquisitions by agencies that are members of CFIUS. Despite the voluntary nature of the notification, firms largely complied with the provision, because the regulations stipulate that foreign acquisitions that are governed by the Exon-Florio review process that do not notify the Committee remain subject indefinitely to possible divestment or other appropriate actions by the President. Under most circumstances, notice of a proposed acquisition that is given to the Committee by a third party, including shareholders, is not considered by the Committee to constitute an official notification. The regulations also indicated that notifications provided to the Committee would be considered confidential and the information would not be released by the Committee to the press or commented on publicly.

The "Byrd Amendment"

In 1992, Congress amended the Exon-Florio statute through Section 837(a) of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1993 (P.L. 102-484). Known as the "Byrd" amendment after the amendment's sponsor, Senator Byrd, the provision requires CFIUS to investigate proposed mergers, acquisitions, or takeovers in cases where two criteria are met:

(1) the acquirer is controlled by or acting on behalf of a foreign government; and

(2) the acquisition results in control of a person engaged in interstate commerce in the United States that could affect the national security of the United States.27

This amendment came under scrutiny by the 109th Congress as a result of the DP World transaction. Many Members of Congress and others believed that this amendment required CFIUS to undertake a full 45-day investigation of the transaction because DP World was "controlled by or acting on behalf of a foreign government." The DP World acquisition, however, exposed a sharp rift between what some Members apparently believed the amendment directed CFIUS to do and how the members of CFIUS interpreted the amendment. In particular, some Members of Congress apparently interpreted the amendment to direct CFIUS to conduct a mandatory 45-day investigation if the foreign firm involved in a transaction is owned or controlled by a foreign government.

Representatives of CFIUS argued they interpreted the amendment to mean that a 45-day investigation was discretionary and not mandatory. In the case of the DP World acquisition, CFIUS representatives argued they had concluded as a result of an extensive review of the proposed acquisition prior to the case being formally filed with CFIUS and during the then-existing 30-day review that the DP World case did not warrant a full 45-day investigation. They conceded that the case met the first criterion under the Byrd amendment, because DP World was controlled by a foreign government, but that it did not meet the second part of the requirement, because CFIUS had concluded during the 30-day review that the transaction "could not affect the national security."28

The intense public and congressional reaction that arose from the proposed Dubai Ports World acquisition spurred the Bush Administration in late 2006 to make an important administrative change in the way CFIUS reviewed foreign investment transactions. CFIUS and President Bush approved the acquisition of Lucent Technologies, Inc. by the French-based Alcatel SA, which was completed on December 1, 2006. Before the transaction was approved by CFIUS, however, Alcatel-Lucent was required to agree to a national security arrangement, known as a Special Security Arrangement, or SSA, that restricts Alcatel's access to sensitive work done by Lucent's research arm, Bell Labs, and the communications infrastructure in the United States.

The most controversial feature of this arrangement was that it allowed CFIUS to reopen a review of a transaction and to overturn its approval at any time if CFIUS believed the companies "materially fail to comply" with the terms of the arrangement. This marked a significant change in the CFIUS process. Prior to this transaction, CFIUS reviews and investigations were portrayed and considered to be final. As a result, firms were willing to subject themselves voluntarily to a CFIUS review, because they believed that once an investment transaction was scrutinized and approved by the members of CFIUS the firms could be assured that the investment transaction would be exempt from any future reviews or actions. This administrative change, however, meant that a CFIUS determination may no longer be a final decision, and it added a new level of uncertainty to foreign investors seeking to acquire U.S. firms. A broad range of U.S. and international business groups objected to this change in the Bush Administration's policy.29

Recent Legislative Reforms

|

CFIUS Risk Assessment In assessing the risk posed to national security by a foreign investment transaction, CFIUS considers three issues: 1. What is the threat posed by the foreign investment in terms of intent and capabilities? 2. What aspects of the business activity pose vulnerabilities to national security? 3. What are the national security consequences if the vulnerabilities are exploited? |

In the first session of the 110th Congress, Representative Maloney introduced H.R. 556, the National Security Foreign Investment Reform and Strengthened Transparency Act of 2007, on January 18, 2007. The House Financial Services Committee approved it on February 13, 2007, with amendments, and the full House amended and approved it on February 28, 2007, by a vote of 423 to 0. On June 13, 2007, Senator Dodd introduced S1610, the Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007 (FINSA). On June 29, 2007, the Senate adopted S. 1610 in lieu of H.R. 556 by unanimous consent. On July 11, 2007, the House accepted the Senate's version of H.R. 556 by a vote of 370-45 and sent the measure to President Bush, who signed it on July 26, 2007.30 On January 23, 2008, President Bush issued Executive Order 13456 implementing the law.

FINSA made a number of major changes, including the following:

- Codified the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), giving it statutory authority.

- Made CFIUS membership permanent and added the Secretary of Energy, the Director of National Intelligence (DNI), and Secretary of Labor as ex officio members with the DNI providing intelligence analysis; also granted authority to the President to add members on a case-by-case basis.

- Required the Secretary of the Treasury to designate an agency with lead responsibility for reviewing a covered transaction.

- Increased the number of factors the President could consider in making his determination.

- Required that an individual no lower than an Assistant Secretary level for each CFIUS member must certify to Congress that a reviewed transaction has no unresolved national security issues; for investigated transactions, the certification must be at the Secretary or Deputy Secretary level.

- Provided Congress with confidential briefings upon request on cleared transactions and annual classified and unclassified reports.

FIRRMA Legislation: Key Provisions

During the 115th Congress, many Members expressed concerns over China's growing investment in the United States, particularly in the technology sector. On November 8, 2017, Senators John Cornyn and Dianne Feinstein and Representative Robert Pittenger introduced companion measures in the Senate (S. 2098) and the House (H.R. 4311), respectively, identified as the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 (FIRRMA) to provide comprehensive revision of the CFIUS process. On May 22, 2018, the Senate Banking and House Financial Services Committees held their respective markup sessions and approved different versions of the legislation. The Senate version of FIRRMA was added as Subtitle A of Title 17 of the Senate version of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 (S. 2987, incorporated into the Senate amendments to H.R. 5515), which passed the Senate on June 18, 2018. The House version of FIRRMA, H.R. 5841 was passed as a standalone bill under suspension vote on June 26, 2018. On August 13, 2018, President Trump signed FIRRMA, identified as P.L. 115-232.

Similar to previous measures, FIRRMA grants the President the authority to block or suspend proposed or pending foreign "mergers, acquisitions, or takeovers" by or with any foreign person that could result in foreign control of any United States business, including such a merger, acquisition, or takeover carried out through a joint venture that threaten to impair the national security.31 Congress directed, however, that before this authority can be invoked the President must conclude that (1) other U.S. laws are inadequate or inappropriate to protect the national security; and (2) he/she must have "credible evidence" that the foreign interest exercising control might take action that threatens to impair the national security. According to CFIUS, it has interpreted this last provision to mean an investment that poses a risk to the national security. In assessing the national security risk, CFIUS looks at (1) the threat, which involves an assessment of the intent and capabilities of the acquirer; (2) the vulnerability, or an assessment of the aspects of the U.S. business that could impact national security; and (3) the potential national security consequences if the vulnerabilities were to be exploited.32

In general, FIRRMA:

- Broadens the scope of transactions under CFIUS' purview by including for review real estate transactions in close proximity to a military installation or a U.S. government facility or property of national security sensitivities; any nonpassive investment in a critical infrastructure or critical technologies; transactions that may result in compromising personally identifiable information of U.S. citizens; any change in foreign investor rights regarding a U.S. business; transactions in which a foreign government has a direct or indirect substantial interest; and any transaction or arrangement designed to evade CFIUS regulations.

- Mandates various deadlines, including: a report on Chinese investment in the United States, a plan for CFIUS members to recuse themselves in cases that pose a conflict of interest, an assessment of CFIUS resources and plans for additional staff and resources, a feasibility study of assessing a fee on transactions reviewed unofficially prior to submission of a written notification, and a report assessing the national security risks related to investments by state-owned or state-controlled entities in the manufacture or assembly of rolling stock or other assets used in freight rail, public transportation rail systems, or intercity passenger rail system in the United States.

- Allows CFIUS to discriminate among foreign investors by country of origin in reviewing investment transactions by labeling some countries as "a country of special concern"—a country that has a demonstrated or declared strategic goal of acquiring a type of critical technology or critical infrastructure that would affect United States leadership in areas related to national security.

- Shifts the filing process for foreign firms from voluntary to mandatory in certain cases and provides for a two-track method for reviewing investment transactions, with some transactions requiring a declaration to CFIUS and receiving an expedited process, while transactions involving investors from countries of special concern would require a written notification of a proposed transaction and would receive greater scrutiny.

- Provides for additional factors for consideration that CFIUS and the President may use to determine if a transaction threatens to impair U.S. national security, as well as formalizes CFIUS' use of risk-based analysis to assess the national security risks of a transaction by assessing the threat, vulnerabilities, and consequences to national security related to the transaction.

- Lengthens most time periods for CFIUS reviews and investigations and for a national security analysis by the Director of National Intelligence.

- Provides for more staff to handle an expected increased workload and provides for additional funding for CFIUS through a filing fee structure for firms involved in a transaction and a $20 million annual appropriation.

- Modifies CFIUS' annual reporting requirements, including its annual classified report to specified Members of Congress and nonclassified reports to the public to provide for more information on foreign investment transactions.

- Mandates separate reforms related to export controls, with requirements to establish an interagency process to identify so-called "emerging and foundational technologies"—such items are to also fall under CFIUS review of critical technologies—and establish controls on the export or transfer of such technologies.

CFIUS: Major Provisions

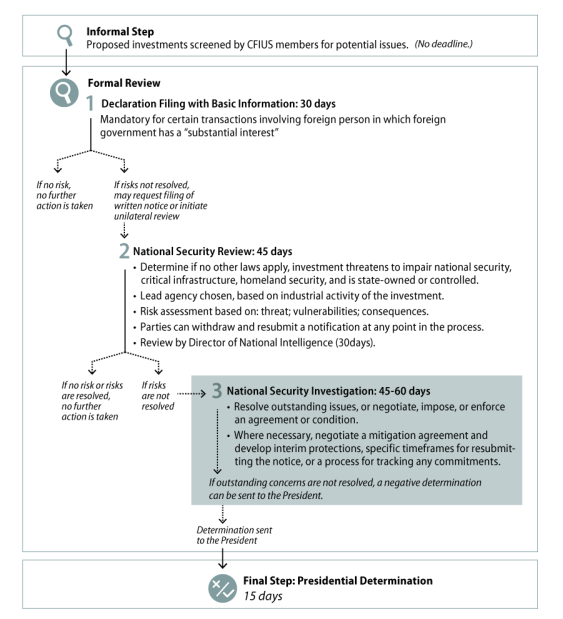

As indicated in Figure 2 below, the CFIUS foreign investment review process is comprised of an informal step and three formal steps: a Declaration or written notice; a National Security Review; and a National Security Investigation. Depending on the outcome of the reviews, CFIUS may forward a transaction to the President for a Presidential Determination. In some cases, FIRRMA increased the allowable time for reviews and investigations: (1) 30 days to review a declaration or written notification to determine if the transaction involves a foreign person in which a foreign government has a substantial financial interest, defined as 25% ownership interest between a foreign person and U.S. business and 49% ownership interest or greater between a foreign government and foreign person; (2) a 45-day national security review (from 30 days), including an expanded time limit for analysis by the Director of National Intelligence (from 20 to 30 days) and (3) 45 days for a national security investigation, with an option for a 15-day extension for "extraordinary circumstances;" and a 15-day presidential determination (unchanged).

FIRRMA provides a "sense of Congress" concerning six additional factors that CFIUS and the President may consider to determine if a proposed transaction threatens to impair U.S. national security. These include:

- 1. Covered transactions that involve a country of "special concern" that has a demonstrated or declared strategic goal of acquiring a type of critical technology or critical infrastructure that would affect U.S. leadership in areas related to national security;

- 2. The potential effects of the cumulative control of, or pattern of recent transactions involving, any one type of critical infrastructure, energy asset, critical material, or critical technology by a foreign government or person;

- 3. Whether any foreign person engaged in a transaction has a history of complying with U.S. laws and regulations;

- 4. Control of U.S. industries and commercial activity that affect U.S. capability and capacity to meet the requirements of national security, including the availability of human resources, products, technology, materials, and other supplies and services;

- 5. The extent to which a transaction is likely to expose personally identifiable information, genetic information, or other sensitive data of U.S. citizens to access by a foreign government or person that may exploit that information to threaten national security; and

- 6. Whether a transaction is likely to exacerbate or create new cybersecurity vulnerabilities or is likely to result in a foreign government gaining a significant new capability to engage in malicious cyber-enabled activities.

- 7.

|

Figure 2. Steps of a CFIUS Foreign Investment National Security Review |

|

|

Source: Chart developed by CRS. |

National Security Reviews

Informal Actions

Over time, the three-step CFIUS process has evolved to include an informal stage of unspecified length of time that consists of an unofficial review by individual CFIUS members prior to the formal filing with CFIUS. This type of informal review likely developed because it serves the interests of both CFIUS and the firms that are involved in an investment transaction. According to Treasury Department officials, this informal contact enabled "CFIUS staff to identify potential issues before the review process formally begins."33 FIRMMA directed CFIUS to analyze the feasibility and potential impact of charging a fee for conducting such informal reviews.

Firms that are party to an investment transaction apparently benefit from this informal review in a number of ways. For one, it allows firms additional time to work out any national security concerns privately with individual CFIUS members. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, it provides a process for firms to avoid risking potential negative publicity that could arise if a transaction were blocked or otherwise labeled as impairing U.S. national security interests. For some firms, public knowledge of a CFIUS investigation has had a negative effect on the value of the firm's stock price.

For CFIUS members, the informal process is beneficial because it gives them as much time as they deem necessary to review a transaction without facing the time constraints that arise under the formal CFIUS review process. This informal review likely also gives CFIUS members added time to negotiate with firms involved in a transaction to restructure the transaction in ways that can address any potential security concerns or to develop other types of conditions that members feel are appropriate in order to remove security concerns.

According to anecdotal evidence, some firms believe the CFIUS process is not market neutral, but adds to market uncertainty that can negatively affect a firm's stock price and lead to economic behavior by some firms that is not optimal for the economy as a whole. Such behavior might involve firms expending resources to avoid a CFIUS investigation, or terminating a transaction that potentially could improve the optimal performance of the economy to avoid a CFIUS investigation. While such anecdotal accounts generally are not a basis for developing public policy, they raise concerns about the possible impact a CFIUS review may have on financial markets and the potential costs of redefining the concept of national security relative to foreign investment.

Formal Actions

Part of FIRRMA directed Treasury to develop pilot programs to address concerns related to some provisions and allow time for additional resources to be directed at developing a more permanent regulatory response. The 2018 pilot program implemented authorities in two sections of FIRRMA by (1) expanding the scope of transactions subject to a CFIUS review to include certain investments involving foreign persons and critical technologies, and (2) implementing mandatory declarations for transactions within the program's scope, exclusive of real estate transactions.

On January 13, 2020, the Treasury Department issued final regulations for FIRRMA, which became effective on February 13, 2020.34 According to Treasury, the final regulations differ from the initial draft regulations by "defining additional terms, adding specificity to a number of provisions, and including illustrative examples, among other things. The final regulations also implement FIRRMA's requirement that the Committee limit the application of its expanded jurisdiction to certain categories of foreign persons."35 The regulations expand and clarify new authority for CFIUS to review certain real estate and other noncontrolling foreign investments on the basis of threats, vulnerabilities, and consequences to national security. Reviews of noncontrolling investments are limited to certain U.S. businesses (referred to as "TID businesses" for Technology, Infrastructure, and Data) that: (1) produce, design, test, manufacture, fabricate, or develop one or more critical technologies in 27 specified industrial sectors;36 or (2) own, operate, manufacture, supply, or service critical infrastructure (28 areas specified);37 or (3) maintain or collect sensitive personal data. One major aim of the proposed regulations reportedly is to "provide clarity to the business and investment communities with respect to the types of U.S. businesses that are covered under FIRRMA's other investment authority." The regulations limit the application of the expanded review process to certain categories of foreign persons, introducing new terms such as "excepted investor" and "excepted foreign state" for noncontrolling transactions. On February 13, 2020, the Treasury Department designated Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom, defined as Great Britain and Northern Ireland, as excepted foreign states. The Department indicated that it would publish at a later date the criteria CFIUS will consider when making its determination to designate a country an excepted foreign state.38

Critical Infrastructure / Critical Technologies

An element of the CFIUS process added by FINSA and reinforced by FIRRMA is the addition of "critical industries" and "critical technologies" as broad categories of economic activity, in addition to homeland security, that could be subject to a CFIUS national security review, broadening CFIUS's mandate. The precedent for this action was set in the Patriot Act of 2001 and the Homeland Security Act of 2002, which define critical industries and homeland security and assign responsibilities for those industries to various federal government agencies. FINSA references those two acts and borrows language from them on critical industries and homeland security. After the September 11th terrorist attacks, Congress passed and President Bush signed the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 (Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism).39 In this act, Congress provided for special support for "critical industries," which it defined as

systems and assets, whether physical or virtual, so vital to the United States that the incapacity or destruction of such systems and assets would have a debilitating impact on security, national economic security, national public health or safety, or any combination of those matters.40

This broad definition is enhanced to some degree by other provisions of the act, which identify certain sectors of the economy that are likely candidates for consideration as components of the national critical infrastructure. These sectors include telecommunications, energy, financial services, water, transportation sectors,41 and the "cyber and physical infrastructure services critical to maintaining the national defense, continuity of government, economic prosperity, and quality of life in the United States."42 The following year, Congress adopted the language in the Patriot Act on critical infrastructure into The Homeland Security Act of 2002.43

In addition, the Homeland Security Act added key resources to the list of critical infrastructure (CI/KR) and defined those resources as "publicly or privately controlled resources essential to the minimal operations of the economy and government."44 Through a series of directives, the Department of Homeland Security identified 17 sectors45 of the economy as falling within the definition of critical infrastructure/key resources and assigned primary responsibility for those sectors to various federal departments and agencies, which are designated as Sector-Specific Agencies (SSAs).46 On March 3, 2008, Homeland Security Secretary Chertoff signed an internal DHS memo designating Critical Manufacturing as the 18th sector on the CI/KR list.

In 2013, the list of critical industries was altered through a Presidential Policy Directive (PPD-21).47 The directive listed three "strategic imperatives" as drivers of the Federal approach to strengthening "critical infrastructure security and resilience:"

- 1. Refine and clarify functional relationships across the Federal Government to advance the national unity of effort to strengthen critical infrastructure security and resilience;

- 2. Enable effective information exchange by identifying baseline data and systems requirements for the Federal Government; and

- 3. Implement an integration and analysis function to inform planning and operations decisions regarding critical infrastructure.

The directive assigns the main responsibility to the Department of Homeland Security for identifying critical industries and coordinating efforts among the various government agencies, among a number of responsibilities. The directive also assigns roles to other agencies and designated 16 sectors as critical to the U.S. infrastructure. The sectors are (1) chemical; (2) commercial facilities; (3) communications; (4) critical manufacturing; (5) dams; (6) defense industrial base; (7) emergency services; (8) energy; (9) financial services; (10) food and agriculture; (11) government facilities; (12) health care and public health; (13) information technology; (14) nuclear reactors, materials, and waste; (15) transportation systems; and (16) water and wastewater systems.48 Under FIRRMA, the term "critical infrastructure" is applied to 28 areas listed in an appendix (such as telecommunications, energy, and transportation), and specific business functions (see footnote 37).

FIRRMA regulations elaborate a number of definitions that define and constrain the scope of CFIUS's reviews. The term, "critical technologies" reflects the definition provided in FIRRMA that covers 27 industrial activities in which critical technologies may be developed or used, including "emerging and foundational technologies," which are or may be subject to export controls, pursuant to the Export Control Reform Act of 2018. The term "critical technologies" is defined by FIRRMA according to US-export-controlled technologies, and includes:

- Defense articles and defense services included on the United States Munitions List set forth in the International Traffic in Arms Regulations under subchapter M of Chapter I of Title 22, Code of Federal Regulations.;

- Civilian/military dual-use technologies included on the Commerce Control List set forth in Supplement No. 1 to part 774 of the Export Administration Regulations under subchapter C of Chapter VII of Title 15, Code of Federal Regulations that are either: under multilateral regimes relating to national security, chemical and biological weapons proliferation, nuclear nonproliferation, or missile technology (i.e., excluding, for instance, "EAR99" items, as well items controlled only for anti-terrorism reasons), or included for reasons relating to regional stability or surreptitious listening;

- Nuclear technologies covered by rules relating to foreign atomic energy activities and export and import of nuclear equipment and materials, software, and technology covered by part 810 of Title 10, Code of Federal Regulations (relating to assistance to foreign atomic energy activities).;

- Select agents and toxins covered by part 331 of Title 7, Code of Federal Regulations, part 121 of Title 9 of such Code, or part 73 of Title 42 of such Code; or

- Emerging and foundational technologies controlled pursuant to the Export Control Reform Act of 2018 (not yet defined, but expected to be forthcoming from the U.S. Commerce Department).

"Sensitive personal data" that may be exploited to threaten national security includes 10 categories of data maintained or collected by U.S. businesses that (1) "target or tailor" products or services to "sensitive populations," like U.S. government personnel; (2) maintain or collect data on more than 1 million individuals; or (3) have a demonstrated objective to maintain or collect data on more than 1 million individuals as part of its primary product or service. Notably, genetic information is included in the definition, regardless of these parameters. Other types of data include financial, geolocation, health, and others. Treasury emphasized that these parameters were drafted to provide as much clarity and specificity as possible to businesses. These specifications do not constrain CFIUS's traditional review of any transaction resulting in foreign control of a U.S. business.

The regulations do not target any particular country for greater scrutiny by CFIUS—a major topic of congressional debate during consideration of FIRRMA. FIRRMA did however, mandate criteria that exempts certain categories of foreign investors from CFIUS's expanded jurisdiction. These criteria include the principal place of business and incorporation, as well as ties to certain eligible countries. Treasury is to publish a list of criteria for determining a limited number of "excepted foreign states"—a status determined by the Treasury Secretary and a supermajority of CFIUS member agencies. As previously indicated, on February 13, 2020, the Treasury Department designated Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom, defined as Great Britain and Northern Ireland, as excepted foreign states. One major factor in determining an excepted state is whether that country is "utilizing a robust process to assess foreign investments for national security risks and to facilitate coordination with the United States on matters relating to investment security." Treasury delayed implementing this requirement to allow countries to enhance their review processes. "Excepted investors," however, would not be exempt from CFIUS's review of controlling-interest transactions.

CFIUS Filing Requirements

Under FIRRMA, the process of notifying a transaction to CFIUS remains largely voluntary, but FIRRMA provided new authority to require a declaration, an abbreviated filing (not to exceed five pages), with basic information on the transaction. A declaration is mandatory for transactions in which a foreign person has a "substantial interest" in a U.S. business, and a foreign government holds a "substantial interest" in the foreign entity making the investment. The regulations specify a voting interest (direct or indirect) threshold for "substantial interest" of 25% between a foreign person and U.S. business and 49% or greater between a foreign government and foreign person. (Any voting interest of a parent entity in a subsidiary is deemed to be a 100% voting interest.) The regulations also implement FIRRMA's mandate that CFIUS take certain actions in response to a declaration. FIRRMA also authorizes CFIUS to impose fees and to create a mandatory filing process: those areas are expected to be covered in future proposed regulations.

Within the regulations, Treasury clarified that declarations and written notices are distinguished according to three criteria: 1) the length of the submission; 2) the time for CFIUS' consideration of the submission; and 3) the Committee's options for disposition of the submission. To qualify for an expedited review declaration, the parties to a transaction can voluntarily stipulate that a transaction is a covered transaction, whether the transaction could result in control of a U.S. business by a foreign person, and whether the transaction is a foreign-government controlled transaction. CFIUS would be required to respond within 30 days to the filing of a declaration, whereas CFIUS would have 45 days to respond to a written notification. Regulations specify the content and filing processes for declarations and notices; misstatements or omissions are subject to a fine of $250,000 per violation

CFIUS is required to respond in one of four ways to a declaration: (1) request that the parties file a written notice; (2) inform the parties that CFIUS cannot complete the review on the basis of the declaration and that they can file a notice to seek a written notification from the Committee that it has completed all the action relevant to the transaction; (3) initiate a unilateral review of the transaction through an agency notice; or (4) notify the parties that CFIUS has completed its action under the statute.

Mandatory filings through declarations are required for some investments in certain U.S. businesses that produce, design, test, manufacture, fabricate, or develop one or more critical technologies in 27 specified industries (see footnote 36). Critical technologies are defined as those that are (1) used in a U.S. business's activity in the specified industries, or (2) designed by the U.S. business specifically for use in those industries. The 27 identified industries are characterized as those in which a "certain strategically motivated foreign investment" could pose a threat to US technological superiority and national security and as "target industries that face imminent threats of erosion of technological superiority from foreign direct investment," according to Treasury regulations.49 According to the Treasury Department,

....some foreign direct investment threatens to undermine the technological superiority that is critical to U.S. national security. Specifically, the threat to critical technology industries is more significant than ever as some foreign parties seek, through various means, to acquire sensitive technologies with relevance for U.S. national security. Foreign investment in U.S. critical technologies has grown significantly in the past decade, and an enhanced framework is needed to address the potential impacts of this growth on U.S. national security.50

Noncontrolling Equity Investments

CFIUS's expanded authority under FIRRMA directs it to review investment transactions whether or not the investment conveys a controlling equity interest in certain cases.51 In particular, this review occurs where a foreign person has: (1) access to information, certain rights, or involvement in the decisionmaking of certain U.S. businesses involved in critical technologies, critical infrastructure, or sensitive personal data (i.e., TID businesses); (2) any change in a foreign person's rights, if such change could result in foreign control of a U.S. business or a covered investment in certain U.S. businesses; and (3) any other transaction, transfer, agreement, or arrangement, designed or intended to evade or circumvent the CFIUS review process.

Specifically, such noncontrolling investments are covered, or subject to a review, if they would grant the foreign investor:

- Access to any material nonpublic technical information in the possession of the target U.S. business;

- Membership or observer rights on the board of directors or equivalent governing body of the U.S. business, or the right to nominate an individual to a position on the board of directors or equivalent governing body of the U.S. business; or

- Any involvement, other than through voting of shares, in substantive decisionmaking of the U.S. business regarding the use, development, acquisition, or release of critical technology.

Additional regulations further define the terms "material non-public technical information" and "substantive decisionmaking." The regulations also clarify circumstances under which CFIUS can review an indirect investment through investment funds. As indicated, this new authority is limited to "TID U.S. businesses." Prior to this change, a controlling interest was determined to be greater than 10% of the voting shares of a publicly traded company, or greater than 10% of total assets of a non-publicly traded U.S. company.

This change in coverage was precipitated by concerns that investments in which foreign firms have a noncontrolling interest could nevertheless "affect certain decisions made by, or obtain certain information from, a U.S. business with respect to the use, development, acquisition, or release of critical technology." Final regulations allow any firm the opportunity to file a short-form declaration, but CFIUS can require a longer-form filing if it determines that such a filing is necessary. Mandatory declarations may be subject to other criteria as defined by regulations.

The chief executive officer of any party to a merger, acquisition, or takeover must certify in writing that the information contained in a written notification to CFIUS fully complies with the CFIUS requirements and that the information is accurate and complete. This written notification would also include any mitigation agreement or condition that was part of a CFIUS approval.

At any point during the CFIUS process, parties can withdraw and refile their notice, for instance, to allow additional time to discuss CFIUS's proposed resolution of outstanding issues. Under FINSA and FIRRMA, the President retains his authority as the only officer capable of suspending or prohibiting mergers, acquisitions, and takeovers, and the measures place additional requirements on firms that resubmitted a filing after previously withdrawing a filing before a full review was completed.

Some stakeholders expressed concern over the potential impact of CFIUS's expanded jurisdiction on smaller U.S. businesses that rely on foreign investment. Treasury indicated that it could not project the economic impact of reviewing certain real estate transactions, but it estimated that the change was not expected to have a "significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities." Similarly, regarding noncontrolling equity investments, Treasury concluded that less than 1% of U.S. small businesses likely would be subject to a review.

Real Estate

CFIUS's expanded jurisdiction over certain real estate (land and structures) transactions includes the purchase or lease by, or a concession to, a foreign person of certain private or public real estate located in the United States.52 Real estate transactions are defined as those that accord the investor certain fundamental property rights. In particular, the provision focuses on real estate that is in proximity of certain airports, maritime ports, and other facilities and properties of the U.S. Government that are sensitive for national security reasons (military installations include 190 facilities located across 40 States and Guam). CFIUS additionally retains the authority to review any transaction that raises national security concerns on the basis of proximity to sensitive sites and activities.

The regulations specify various definitions, such as:

- Stipulated airports: As defined by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), major passenger and cargo airports based on volume and "joint use airports" that serve civilian and military aircraft;

- Close proximity: Areas within one mile of a relevant military installation or other facility or property of the U.S. Government;

- Extended range: Areas between one and 100 miles;

- Facilities located within designated counties, according to Appendix A of the proposed regulations; and

- Off-shore ranges: Within 12 nautical miles of the U.S.

Excepted real estate transactions include: (1) certain real estate investors, defined as those with a substantial connection to certain foreign countries and who have not violated U.S. laws; (2) housing units; (3) urbanized areas and urban clusters (both defined by the Census Bureau); (4) commercial office space (with some exceptions); (5) retail trade, accommodation, or food service establishments; (6) lands held by Native Americans and some Alaskan Natives; and (7) certain lending and contingent equity transactions. Requirements for filing a voluntary declaration or written notice are similar to those for other investment transactions, except that a filing is not mandatory for a real estate transaction. The regulations define an excepted foreign investor through various criteria, including holding the right to 5% or more of the profit of the investing foreign firm, or the ability to exercise control.

National Security Review

After a transaction is filed with CFIUS and depending on an initial assessment, the transaction can be subject to a 45-day national security review (increased from 30 days by FIRRMA). During a review, CFIUS members are required to consider the 12 factors mandated by Congress through FINSA and six new factors in FIRRMA that reflect the "sense of Congress" in assessing the impact of an investment. If during the 45-day review period all members conclude that the investment does not threaten to impair the national security, the review is terminated.

During the 45-day review stage, the Director of National Intelligence (DNI), an ex officio member of CFIUS, is required to carry out a thorough analysis of "any threat to the national security of the United States" of any merger, acquisition, or takeover. This analysis is required to be completed "within 30 days" (modified by FIRRMA from 20 to 30 days) of the receipt of a notification by CFIUS. This analysis could include a request for information from the Department of the Treasury's Director of the Office of Foreign Assets Control and the Director of the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. In addition, the Director of National Intelligence is required to seek and to incorporate the views of "all affected or appropriate" intelligence agencies. CFIUS also is required to review "covered" investment transactions in which the foreign entity is owned or controlled by a foreign government, but the law provides an exception to this requirement. If the Secretary of the Treasury and certain other specified officials determine that the transaction in question will not impair the national security, the investment is not subject to a formal review.

National Security Investigation

If a national security review indicates that at least one of three conditions exists, the President, acting through CFIUS, is required to conduct a National Security Investigation and to take any "necessary" actions as part of an additional 45-day investigation, with a possible 15-day extension for "extraordinary circumstances." The three conditions are: (1) CFIUS determines that the transaction threatens to impair the national security of the United States and that the threat has not been mitigated during or prior to a review of the transaction; (2) the foreign person is controlled by a foreign government; or (3) the transaction would result in the control of any critical infrastructure by a foreign person, the transaction could impair the national security, and such impairment had not been mitigated. At the conclusion of the investigation or 45-day review period, whichever comes first, the Committee can offer no recommendation, approve a mitigation agreement, or it can recommend to the President that he/she suspend or prohibit the investment.

During a review or an investigation, CFIUS and a designated lead agency have the authority to negotiate, impose, or enforce any agreement or condition with the parties to a transaction in order to mitigate any threat to U.S. national security. Such agreements are based on a "risk-based analysis" of the threat posed by the transaction. Also, if a notification of a transaction is withdrawn before any review or investigation by CFIUS is completed, the amended law grants the Committee the authority to take a number of actions. In particular, the Committee could develop (1) interim protections to address specific concerns about the transaction pending a resubmission of a notice by the parties; (2) specific time frames for resubmitting the notice; and (3) a process for tracking any actions taken by any parties to the transaction.

|

Transactions Blocked by Presidents Since the creation of CFIUS, presidential action blocked five transactions based on CFIUS recommendations: 1. In 1990, President Bush directed the China National Aero-Technology Import and Export Corporation (CATIC) to divest its acquisition of MAMCO Manufacturing. 2. In 2012, President Obama directed the Ralls Corporation to divest itself of an Oregon wind farm project. 3. In 2016, President Obama blocked the Chinese firm Fujian Grand Chip Investment Fund from acquiring Aixtron, a German-based semiconductor firm with U.S. assets. 4. In 2017, President Trump blocked the acquisition of Lattice Semiconductor Corp. of Portland, OR, for $1.3 billion by Canyon Bridge Capital Partners, a Chinese investment firm. 5. In 2018, President Trump blocked the acquisition of semiconductor chip maker Qualcomm by Singapore-based Broadcom for $117 billion. |

Presidential Determination