The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS)

Changes from June 13, 2017 to October 11, 2017

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

Contents

- Background

- Establishment of CFIUS

- The "Exon-Florio" Provision

- Treasury Department Regulations

- The "Byrd Amendment"

- The Amended CFIUS Process

- Informal Actions

- Formal Actions

- National Security Review

- National Security Investigation

- Presidential Determination

- Committee Membership

- Covered Transactions

- Critical Infrastructure

- Foreign Ownership Control

- Factors for Consideration

- Confidentiality Requirements

- Mitigation and Tracking

- Congressional Oversight

- Recent CFIUS Reviews

- Notable Cases

- Verio

- Check Point Software

- JBS-Pilgrim's Pride

- Sprint Nextel

- Firstgold

- AMC Entertainment

- Dubai Ports World

- 3Com

- Ralls Wind Farm Acquisition

- A123 Systems

- Smithfield Foods

- Roscosmos

- Fairchild Semiconductor

- Micron/Western Digital

- Phillips-Lumileds

- Syngenta

- Chicago Stock Exchange

- Aixtron

- Global Communications Semiconductor

- Citgo-Rosneft

- Foreign Investment National Security Policies of Foreign Jurisdictions

- Government-Sponsored Firms and National Security

- Government-Sponsored Firms and National Security

- House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence

- U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission

- CFIUS-DIUx Report

- Other National Security Concerns

- Issues for Congress

- Proposed Legislation

- Issues for Congress

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. Selected Indicators of International Investment and Production, 2008-2015

- Table 2. Foreign Investment Transactions Reviewed by CFIUS, 2008-

20142015

- Table 3. Industry Composition of Foreign Investment Transactions Reviewed by CFIUS, 2008-

20142015

- Table 4. Country of Foreign Investor and Industry Reviewed by CFIUS,

2012-20142013-2015

- Table 5. Home Country of Foreign Acquirer of U.S. Critical Technology, 2013-2015

- Appendix A. Selected CFIUS Cases

Appendixes

Summary

The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) is an interagency body comprised of nine Cabinet members, two ex officio members, and other members as appointed by the President, that assists the President in overseeing the national security aspects of foreign direct investment in the U.S. economy. While the group often operated in relative obscurity, the perceived change in the nation's national security and economic concerns following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and the proposed acquisition of commercial operations at six U.S. ports by Dubai Ports World in 2006 placed CFIUS's review procedures under intense scrutiny by Members of Congress and the public. Prompted by this case, some Members of Congress questioned the ability of Congress to exercise its oversight responsibilities given the general view that CFIUS's operations lacked transparency. The current CFIUS process reflects changes Congress initiated in the first session of the 110th Congress, when the House and Senate adopted S. 1610, the Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007 (FINSA). In the 115th Congress, legislation has been introduced to include the Secretaries of Agriculture and Health and Human Services as permanent members of CFIUS and for other purposes.

Generally, efforts to amend CFIUS have been spurred by a specific foreign investment transaction that raised national security concerns. Despite various changes to the CFIUS statute, some Members and others are questioning the nature and scope of CFIUS's reviews. The CFIUS process is governed by statute that sets a legal standard for the President to suspend or block a transaction if no other laws apply and if there is "credible evidence" that the transaction threatens to impair the national security, which is interpreted as transactions that pose a national security risk.

The U.S. policy approach to international investment traditionally has been to establish and support an open and rules-based system that is in line with U.S. economic and national security interests. The current debate over CFIUS reflects long -standing concerns about the impact of foreign investment on the economy and the role of economics as a component of national security. Some Members question CFIUS's performance and the way the Committee reviews cases involving foreign governments, particularly with the emergence of state-owned enterprises. Some policymakers have suggested expanding CFIUS's purview to include a broader focus on the economic implications of individual foreign investment transactions and the cumulative effect of foreign investment on certain sectors of the economy or by investors from individual countries. Changes in U.S. foreign investment policy have potentially large economy-wide implications, since the United States is the largest recipient and the largest overseas investor of foreign direct investment. To date, only threefour investments have been blocked by previous Presidents, although proposed transactions may have been terminated by the firms involved in lieu of having a transaction blocked. President Obama used the FINSA authority in 2012 to block an American firm, Ralls Corporation, owned by Chinese nationals, from acquiring a U.S. wind farm energy firm located near a DOD facility and to block a Chinese investment firm in 2016 from acquiring Aixtron, a Germany-based firm with assets in the United States.

Background

The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) is an interagency committee that serves the President in overseeing the national security implications of foreign direct investment (FDI) in the economy. Since its inception, CFIUS has operated at the nexus of shifting concepts of national security, especially relative to various notions of national economic security, and a changing global economic order that is marked in part by emerging economies such as China that are playing a more active role in the global economy. As a basic premise, the U.S. historical approach to international investment has aimed to establish an open and rules-based system that is consistent across countries and in line with U.S. economic and national security interests. This policy also has fundamentally maintained that FDI has positive net benefits for the economy, except in certain cases in which national security concerns outweigh other considerations. More recently, some policymakers have argued that certain foreign investment transactions, particularly by entities owned or controlled by a foreign government, are compromising U.S. national economic security and argue for greater CFIUS scrutiny of foreign investment transactions, including a mandatory approval process. Some policymakers also argue that the CFIUS review process should have a more robust economic component, possibly even to the extent of an industrial policy-type approach that uses the CFIUS national security review process to protect and promote certain industrial sectors in the economy. Others argue, however, that this review process should maintain its current focus on national security issues.

Originally established by an Executive Order of President Ford in 1975, the committeeCommittee generally operated in relative obscurity.1 According to a Treasury Department memorandum, the Committee originally was established in order to "dissuade Congress from enacting new restrictions" on foreign investment, as a result of growing concerns over the rapid increase in investments by Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) countries in American portfolio assets (Treasury securities, corporate stocks and bonds), and to respond to concerns of some that much of the OPEC investments were being driven by political, rather than by economic, motives.2

Thirty years later, public and congressional concerns about the proposed purchase of commercial port operations of the British-owned Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O)3 in six U.S. ports by Dubai Ports World (DP World)4 sparked a firestorm of criticism and congressional activity during the 109th Congress concerning CFIUS and the manner in which it operated. As a result of the attention by the public and Congress, DP World officials decided to sell off the U.S. port operations to an American owner.5 On December 11, 2006, DP World officials announced that a unit of AIG Global Investment Group, a New York-based asset management company with large assets, but no experience in port operations, had acquired the U.S. port operations for an undisclosed amount.6

The DP World transaction revealed that the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks fundamentally altered the viewpoint of some Members of Congress regarding the role of foreign investment in the economy and the impact of such investment on the national security framework. Some Members argued that this change in perspective required a reassessment of the role of foreign investment in the economy and of the implications of corporate ownership on activities that fall under the rubric of critical infrastructure. The emergence of state-owned enterprises as commercial economic actors has raised additional concerns about whose interests and whose objectives such firms are pursuing in their foreign investment activities.

Members of Congress introduced more than 25 bills in the second session of the 109th Congress that addressed various aspects of foreign investment following the proposed DP World transaction. In the first session of the 110th Congress, Members approved, and President Bush signed, the Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007 (FINSA), (P.L. 110-49), which altered the CFIUS process in order to enable greater oversight by Congress and increased transparency and reporting by the Committee on its decisions. In addition, the Actact broadened the definition of national security and required greater scrutiny by CFIUS of certain types of foreign direct investments. Not all Members were satisfied with the law: some Members argued that the law remained deficient in reviewing investment by foreign governments through sovereign wealth funds (SWFs), an issue that was attracting attention when the law was adopted. Also left unresolved were issues concerning the role of foreign investment in the nation's overall security framework and the methods that are used to assess the impact of foreign investment on the nation's defense industrial base, critical infrastructure, and homeland security.

Information on international investment and production collected and published by the United Nations indicates that FDI peaked in 2007 prior to the global financial crisis and has not fully recovered. Similarly, from 2012 through 2014, international flows of FDI fell below the levels reached prior to the 2008-2009 financial crisis. Cross-border merger and acquisition activity (M&As) picked up in 2014, after lagging behind the pace set in 2008, although global nominal gross domestic product (GDP) generally has risen since 2009. Globally, at 79 million, employment by the foreign affiliates of international firms has surpassed the 77 million recorded in 2007. Globally, foreign direct investment totals about $25 trillion. Other measures of international production, sales, assets, value-added production, and exports all indicate higher nominal values in 2015, which provides further indication that global economic growth is recovering, although at a slow pace.

According to the United Nations,7 the global FDI position in the United States, or the cumulative amount, was recorded at around $5.6 trillion in 2015, with the U.S. outward FDI position of about $6.0 trillion. The next closest country in investment position to the United States is Germany with inward and outward investment positions of about one-fifth that of the United States.

Table 1. Selected Indicators of International Investment and Production, 2008-2015

(Billions of dollars)

|

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

|

|

FDI inflows |

$1,744.0 |

$1,198.0 |

$1,409.0 |

$1,700.0 |

$1,403.0 |

$1,427.0 |

$1,277.0 |

$1,762.0 |

|

FDI outflows |

1,911.0 |

1,175.0 |

1,505.0 |

1,712.0 |

1,284.0 |

1,311.0 |

1,318.0 |

$1,474.0 |

|

FDI inward stock |

15,295.0 |

18,041.0 |

20,380.0 |

21,117.0 |

22,073.0 |

24,533.0 |

25,113.0 |

24,983.0 |

|

FDI outward stock |

15,988.0 |

19,326.0 |

21,130.0 |

21,913.0 |

22,527.0 |

24,665.0 |

24,810.0 |

25,045.0 |

|

Cross-border M&As (number) |

707 |

250 |

344 |

556 |

328 |

263 |

432 |

721 |

|

Sales of foreign affiliates |

33,300.0 |

23,866.0 |

22,574.0 |

28,516.0 |

31,687.0 |

31,865.0 |

34,149.0 |

36,668.0 |

|

Value-added (product) of foreign affiliates |

6,216.0 |

6,392.0 |

5,735.0 |

6,262.0 |

7,105.0 |

7,030.0 |

7,419.0 |

7,903.0 |

|

Total assets of foreign affiliates |

64,423.0 |

74,910.0 |

78,631.0 |

83,754.0 |

88,536.0 |

95,671.0 |

101,254.0 |

105,778.0 |

|

Exports of foreign affiliates |

6,599.0 |

5,060.0 |

6,320.0 |

7,463.0 |

7,469.0 |

7,469.0 |

7,688.0 |

7,803.0 |

|

GDP |

61,147.0 |

57,920.0 |

63,468.0 |

71,314.0 |

73,457.0 |

75,887.0 |

77,807.0 |

73,152.0 |

|

Employment by foreign affiliates (thousands) |

64,484.0 |

59,877.0 |

63,043.0 |

63,416.0 |

69,359.0 |

72,239.0 |

76,821.0 |

79,505.0 |

Source: World Investment Report, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, June 2016.

Establishment of CFIUS

President Ford's 1975 Executive Order established the basic structure of CFIUS, and directed that the "representative"8 of the Secretary of the Treasury be the chairman of the Committee. The Executive Order also stipulated that the Committee would have "the primary continuing responsibility within the executive branch for monitoring the impact of foreign investment in the United States, both direct and portfolio, and for coordinating the implementation of United States policy on such investment." In particular, CFIUS was directed to (1) arrange for the preparation of analyses of trends and significant developments in foreign investment in the United States; (2) provide guidance on arrangements with foreign governments for advance consultations on prospective major foreign governmental investment in the United States; (3) review investment in the United States which, in the judgment of the Committee, might have major implications for United States national interests; and (4) consider proposals for new legislation or regulations relating to foreign investment as may appear necessary.9

President Ford's Executive Order also stipulated that information submitted "in confidence shall not be publicly disclosed" and that information submitted to CFIUS be used "only for the purpose of carrying out the functions and activities" of the order. In addition, the Secretary of Commerce was directed to perform a number of activities, including

(1) obtaining, consolidating, and analyzing information on foreign investment in the United States;

(2) improving the procedures for the collection and dissemination of information on such foreign investment;

(3) the close observing of foreign investment in the United States;

(4) preparing reports and analyses of trends and of significant developments in appropriate categories of such investment;

(5) compiling data and preparing evaluation of significant transactions; and

(6) submitting to the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States appropriate reports, analyses, data, and recommendations as to how information on foreign investment can be kept current.

|

CFIUS Legislative History 1975 CFIUS established by Executive Order. 1988 "Exon-Florio" amendment to Defense Production Act. Codified the process CFIUS used to review foreign investment transactions. 1992 "Byrd Amendment" to Defense Production Act. Required reviews in cases where foreign acquirer was acting on or behalf of a foreign government. 2007 Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007. Replaced Executive Order and codified CFIUS. |

The Executive Order, however, raised questions among various observers and government officials who doubted that federal agencies had the legal authority to collect the types of data that were required by the order. As a result, Congress and the President sought to clarify this issue, and in the following year President Ford signed the International Investment Survey Act of 1976.10 The act gave the President "clear and unambiguous authority" to collect information on "international investment." In addition, the act authorized "the collection and use of information on direct investments owned or controlled directly or indirectly by foreign governments or persons, and to provide analyses of such information to the Congress, the executive agencies, and the general public."11

By 1980, some Members of Congress had come to believe that CFIUS was not fulfilling its mandate. Between 1975 and 1980, for instance, the Committee had met only 10 times and seemed unable to decide whether it should respond to the political or the economic aspects of foreign direct investment in the United States.12 One critic of the Committee argued in a congressional hearing in 1979 that, "the Committee has been reduced over the last four years to a body that only responds to the political aspects or the political questions that foreign investment in the United States poses and not with what we really want to know about foreign investments in the United States, that is: Is it good for the economy?"13

From 1980 to 1987, CFIUS investigated a number of foreign investments, mostly at the request of the Department of Defense. In 1983, for instance, a Japanese firm sought to acquire a U.S. specialty steel producer. The Department of Defense subsequently classified the metals produced by the firm because they were used in the production of military aircraft, which caused the Japanese firm to withdraw its offer. Another Japanese company attempted to acquire a U.S. firm in 1985 that manufactured specialized ball bearings for the military. The acquisition was completed after the Japanese firm agreed that production would be maintained in the United States. In a similar case in 1987, the Defense Department objected to a proposed acquisition of the computer division of a U.S. multinational company by a French firm because of classified work engaged in by the computer division. The acquisition proceeded after the classified contracts were reassigned to the U.S. parent company.14

The "Exon-Florio" Provision

In 1988, amid concerns over foreign acquisition of certain types of U.S. firms, particularly by Japanese firms, Congress approved the Exon-Florio amendment to the Defense Production Act, which specifies the process by which foreign investments are reviewed.15 This statute grants the President the authority to block proposed or pending foreign "mergers, acquisitions, or takeovers" of "persons engaged in interstate commerce in the United States" that threaten to impair the national security. Congress directed, however, that before this authority can be invoked the President must conclude that (1) other U.S. laws are inadequate or inappropriate to protect the national security; and (2) he must have "credible evidence" that the foreign investment will impair the national security. This same standard was maintained in an update to the Exon-Florio provision in 2007, the Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007.

By the late 1980s, Congress and the public had grown increasingly concerned about the sharp increase in foreign investment in the United States and the potential impact such investment might have on the U.S. economy. In particular, the proposed sale in 1987 of Fairchild Semiconductor Co. by Schlumberger Ltd. of France to Fujitsu Ltd. of Japan touched off strong opposition in Congress and provided much of the impetus behind the passage of the Exon-Florio provision. The proposed Fairchild acquisition generated intense concern in Congress in part because of general difficulties in trade relations with Japan at that time and because some Americans felt that the United States was declining as an international economic and world power. The Defense Department opposed the acquisition because some officials believed that the deal would have given Japan control over a major supplier of computer chips for the military and would have made U.S. defense industries more dependent on foreign suppliers for sophisticated high-technology products.16

Although Commerce Secretary Malcolm Baldridge and Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger failed in their attempt to have President Reagan block the Fujitsu acquisition, Fujitsu and Schlumberger called off the proposed sale of Fairchild.17 While Fairchild was acquired some months later by National Semiconductor Corp. for a discount,18 the Fujitsu-Fairchild incident marked an important shift in the Reagan Administration's support for unlimited foreign direct investment in U.S. businesses and boosted support within the Administration for fixed guidelines for blocking foreign takeovers of companies in national security-sensitive industries.19

In 1988, after three years of often contentious negotiations between Congress and the Reagan Administration, Congress passed and President Reagan signed the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988.20 During consideration of the Exon-Florio proposal as an amendment to the 1988 Omnibus Trade bill, debate focused on three issues that generated a clash of views: (1) what constitutes foreign control of a U.S. firm?; (2) how should national security be defined?; and (3) which types of economic activities should be targeted for a CFIUS review? Of these issues, the most controversial and the most far-reaching was the lack of a definition of national security. As originally drafted, the provision would have considered investments which affected the "national security and essential commerce" of the United States. The term "essential commerce" was the focus of intense debate between Congress and the Reagan Administration.

The Treasury Department, headed by Secretary James Baker, objected to the Exon-Florio amendment, and the Administration vetoed the first version of the omnibus trade legislation, in part due to its objections to the language in the measure regarding "national security and essential commerce." The Reagan Administration argued that the language would broaden the definition of national security beyond the traditional concept of military/defense to one which included a strong economic component. Administration witnesses argued against this aspect of the proposal and eventually succeeded in prodding Congress to remove the term "essential commerce" from the measure and in narrowing substantially the factors the President must consider in his determination.

The final Exon-Florio provision was included as Section 5021 of the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988. The provision originated in bills reported by the Commerce Committee in the Senate and the Energy and Commerce Committee in the House, but the measure was transferred to the Senate Banking Committee as a result of a dispute over jurisdictional responsibilities.21 Through Executive Order 12661, President Reagan implemented provisions of the Omnibus Trade Act. In the Executive Order, President Reagan delegated his authority to administer the Exon-Florio provision to CFIUS,22 particularly to conduct reviews, undertake investigations, and make recommendations, although the statute itself does not specifically mention CFIUS. As a result of President Reagan's action, CFIUS was transformed from an administrative body with limited authority to review and analyze data on foreign investment to an important component of U.S. foreign investment policy with a broad mandate and significant authority to advise the President on foreign investment transactions and to recommend that some transactions be suspended or blocked.

In 1990, President Bush directed the China National Aero-Technology Import and Export Corporation (CATIC) to divest its acquisition of MAMCO Manufacturing, a Seattle-based firm producing metal parts and assemblies for aircraft, because of concerns that CATIC might gain access to technology through MAMCO that it would otherwise have to obtain under an export license.23

Part of Congress's motivation in adopting the Exon-Florio provision apparently arose from concerns that foreign takeovers of U.S. firms could not be stopped unless the President declared a national emergency or regulators invoked federal antitrust, environmental, or securities laws. Through the Exon-Florio provision, Congress attempted to strengthen the President's hand in conducting foreign investment policy, while limiting its own role as a means of emphasizing that, as much as possible, the commercial nature of investment transactions should be free from political considerations. Congress also attempted to balance public concerns about the economic impact of certain types of foreign investment with the nation's long-standing international commitment to maintaining an open and receptive environment for foreign investment.

|

Transactions Blocked by Presidents Since the creation of CFIUS, the President has blocked 1. In 1990, President Bush directed the China National Aero-Technology Import and Export Corporation (CATIC) to divest its acquisition of MAMCO Manufacturing. 2. In 2012, President Obama directed the Ralls Corporation to divest itself of an Oregon wind farm project. 3. In 2016, President Obama blocked the Chinese firm Fujian Grand Chip Investment Fund from acquiring Aixtron, a German-based semiconductor firm with U.S. assets. 4. In 2017, President Trump blocked the acquisition of Lattice Semiconductor Corp. of Portland, OR, for $1.3 billion by Canyon Bridge Capital Partners, a Chinese investment firm. |

Furthermore, Congress did not intend to have the Exon-Florio provision alter the generally open foreign investment climate of the country or to have it inhibit foreign direct investment in industries that could not be considered to be of national security interest. At the time, some analysts believed the provision could potentially widen the scope of industries that fell under the national security rubric. CFIUS, however, is not free to establish an independent approach to reviewing foreign investment transactions, but operates under the authority of the President and reflects his attitudes and policies. As a result, the discretion CFIUS uses to review and to investigate foreign investment cases reflects policy guidance from the President. Foreign investors also are constrained by legislation that bars foreign direct investment in such industries as maritime, aircraft, banking, resources, and power.24 Generally, these sectors were closed to foreign investors prior to passage of the Exon-Florio provision in order to prevent public services and public interest activities from falling under foreign control, primarily for national defense purposes.

Treasury Department Regulations

After extensive public comment, the Treasury Department issued its final regulations in November 1991 implementing the Exon-Florio provision.2524 Although these procedures were amended through FINSA, they continued to serve as the basis for the Exon-Florio review and investigation until new regulations were released on November 21, 2008.2625 These regulations created an essentially voluntary system of notification by the parties to an acquisition, and they allowed for notices of acquisitions by agencies that are members of CFIUS. Despite the voluntary nature of the notification, firms largely comply with the provision, because the regulations stipulate that foreign acquisitions that are governed by the Exon-Florio review process that do not notify the Committee remain subject indefinitely to possible divestment or other appropriate actions by the President. Under most circumstances, notice of a proposed acquisition that is given to the Committee by a third party, including shareholders, is not considered by the Committee to constitute an official notification. The regulations also indicated that notifications provided to the Committee would be considered confidential and the information would not be released by the Committee to the press or commented on publicly.

The "Byrd Amendment"

In 1992, Congress amended the Exon-Florio statute through Section 837(a) of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 1993 (P.L. 102-484). Known as the "Byrd" amendment after the amendment's sponsor, the provision requires CFIUS to investigate proposed mergers, acquisitions, or takeovers in cases where two criteria are met:

(1) the acquirer is controlled by or acting on behalf of a foreign government; and

(2) the acquisition results in control of a person engaged in interstate commerce in the United States that could affect the national security of the United States.27

This amendment came under scrutiny by the 109th Congress as a result of the DP World transaction. Many Members of Congress and others believed that this amendment required CFIUS to undertake a full 45-day investigation of the transaction because DP World was "controlled by or acting on behalf of a foreign government." The DP World acquisition, however, exposed a sharp rift between what some Members apparently believed the amendment directed CFIUS to do and how the members of CFIUS were interpreting the amendment. In particular, some Members of Congress apparently interpreted the amendment to direct CFIUS to conduct a mandatory 45-day investigation if the foreign firm involved in a transaction is owned or controlled by a foreign government. Representatives of CFIUS argued that they interpreted the amendment to mean that a 45-day investigation was discretionary and not mandatory. In the case of the DP World acquisition, CFIUS representatives argued that they had concluded as a result of an extensive review of the proposed acquisition prior to the case being formally filed with CFIUS and during the 30-day review that the DP World case did not warrant a full 45-day investigation. They conceded that the case met the first criterion under the Byrd amendment, because DP World was controlled by a foreign government, but that it did not meet the second part of the requirement, because CFIUS had concluded during the 30-day review that the transaction "could not affect the national security."28

The intense public and congressional reaction that arose from the proposed Dubai Ports World acquisition spurred the Bush Administration in late 2006 to make an important administrative change in the way CFIUS reviewed foreign investment transactions. CFIUS and President Bush approved the acquisition of Lucent Technologies, Inc. by the French-based Alcatel SA, which was completed on December 1, 2006. Before the transaction was approved by CFIUS, however, Alcatel-Lucent was required to agree to a national security arrangement, known as a Special Security Arrangement, or SSA, that restricts Alcatel's access to sensitive work done by Lucent's research arm, Bell Labs, and the communications infrastructure in the United States.

The most controversial feature of this arrangement is that it allows CFIUS to reopen a review of the deal and to overturn its approval at any time if CFIUS believed the companies "materially fail to comply" with the terms of the arrangement. This marked a significant change in the CFIUS process. Prior to this transaction, CFIUS reviews and investigations were portrayed and considered to be final. As a result, firms were willing to subject themselves voluntarily to a CFIUS review, because they believed that once an investment transaction was scrutinized and approved by the members of CFIUS the firms could be assured that the investment transaction would be exempt from any future reviews or actions. This administrative change, however, meant that a CFIUS determination may no longer be a final decision, and it added a new level of uncertainty to foreign investors seeking to acquire U.S. firms. A broad range of U.S. and international business groups objected to this change in the Bush Administration's policy.29

The Amended CFIUS Process

In the first session of the 110th Congress, Representative Maloney introduced H.R. 556, the National Security Foreign Investment Reform and Strengthened Transparency Act of 2007, on January 18, 2007. The House Financial Services Committee approved it on February 13, 2007, with amendments, and the full House amended and approved it on February 28, 2007, by a vote of 423 to 0. On June 13, 2007, Senator Dodd introduced S. 1610, the Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007 (FINSA). On June 29, 2007, the Senate adopted S. 1610 in lieu of H.R. 556 by unanimous consent. On July 11, 2007, the House accepted the Senate's version of H.R. 556 by a vote of 370-45 and sent the measure to President Bush, who signed it on July 26, 2007.3029 On January 23, 2008, President Bush issued Executive Order 13456 implementing the law.

|

CFIUS Risk Assessment In assessing the risk posed to national security by a foreign investment transaction, CFIUS considers three issues: 1. What is the threat posed by the foreign investment in terms of intent and capabilities? 2. What aspects of the business activity pose vulnerabilities to national security? 3. What are the national security consequences if the vulnerabilities are exploited? |

Similar to the Exon-Florio Amendment, FINSA grants the President the authority to block or suspend a proposed or pending foreign "mergers, acquisitions, or takeovers" of "persons engaged in interstate commerce in the United States" that threaten to impair the national security. Congress directed, however, that before this authority can be invoked the President must conclude that (1) other U.S. laws are inadequate or inappropriate to protect the national security; and (2) he/she must have "credible evidence" that the foreign interest exercising control might take action that threatens to impair the national security. According to CFIUS, it has interpreted this last provision to mean an investment that poses a risk to the national security. In assessing the national security risk, CFIUS looks at: (1) the threat, which involves an assessment of the intent and capabilities of the acquirer; (2) the vulnerability, which involves an assessment of the aspects of the U.S. business that could impact national security; and (3) the potential national security consequences if the vulnerabilities were to be exploited.3130

Major changes made by FINSA included the following:

- Codified the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), giving it statutory authority.

- Made CFIUS membership permanent and added the Secretary of Energy; added the Director of National Intelligence (DNI) and Secretary of Labor as ex officio members with the DNI providing intelligence analysis; also granted authority to the President to add members on a case-by-case basis.

- Required the Secretary of the Treasury to designate an agency with lead responsibility for reviewing a covered transaction.

- Increased the number of factors the President could consider in making his determination.

- Required that an individual no lower than an Assistant Secretary level for each CFIUS member must certify to Congress that a reviewed transaction has no unresolved national security issues; for investigated transactions, the certification must be at the Secretary or Deputy Secretary level.

- Provided Congress with confidential briefings upon request on cleared transactions and annual classified and unclassified reports.

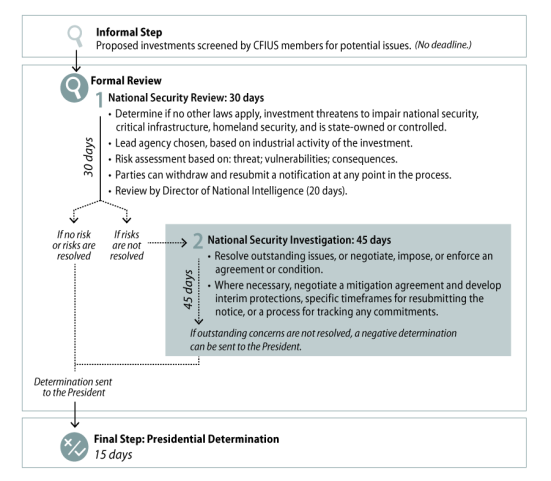

As indicated in Figure 1 below, the CFIUS foreign investment review process is comprised of an informal step and three formal steps: a National Security Review; a National Security Investigation; and a Presidential Determination.

|

Figure 1. Steps of a CFIUS Foreign Investment National Security Review |

|

|

Source: Chart developed by CRS. |

Informal Actions

Over time, the three-step CFIUS process has evolved to include an informal stage of unspecified length of time that consists of an unofficial CFIUS determination prior to the formal filing with CFIUS. This type of informal review likely developed because it serves the interests of both CFIUS and the firms that are involved in an investment transaction. According to Treasury Department officials, this informal contact enabledenables "CFIUS staff to identify potential issues before the review process formally begins."3231

Firms that are party to an investment transaction apparently benefit from this informal review in a number of ways. For one, it allows firms additional time to work out any national security concerns privately with individual CFIUS members. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, it provides a process for firms to avoid risking potential negative publicity that could arise if a transaction were blocked or otherwise labeled as impairing U.S. national security interests. For some firms, public knowledge of a CFIUS investigation has had a negative effect on the value of the firm's stock price.

For CFIUS members, the informal process is beneficial because it gives them as much time as they consider necessary to review a transaction without facing the time constraints that arise under the formal CFIUS review process. This informal review likely also gives the CFIUS members added time to negotiate with firms involved in a transaction to restructure the transaction in ways that can address any potential security concerns or to develop other types of conditions that members feel are appropriate in order to remove security concerns.

According to the amended CFIUS provision, the President or any member of CFIUS can initiate a review of an investment transaction, in addition to a review that is initiated by the parties to a transaction providing a formal notification. CFIUS has 30 days after it receives the initial formal notification by the parties to a merger, acquisition, or takeover to review the transaction to decide whether to investigate a case as a result of its determination that the investment "threatens to impair the national security of the United States." National security also includes "those issues relating to 'homeland security,' including its application to critical infrastructure," and "critical technologies." In addition, CFIUS is required to conduct an investigation of a transaction if the Committee determines that the transaction would result in foreign control of any person engaged in interstate commerce in the United States. During such a review, CFIUS members are required to consider the 12 factors mandated by Congress in assessing the impact of the investment. If during this 30-day period all members conclude that the investment does not threaten to impair the national security, the review is terminated. If, however, at least one member of the Committee determines that the investment threatens to impair the national security, CFIUS proceeds to a 45-day investigation.

According to anecdotal evidence, some firms believe the CFIUS process is not market neutral, but adds to market uncertainty that can negatively affect a firm's stock price and lead to economic behavior by some firms that is not optimal for the economy as a whole. Such behavior might involve firms expending resources to avoid a CFIUS investigation, or terminating a transaction that potentially could improve the optimal performance of the economy to avoid a CFIUS investigation. While such anecdotal accounts are not sufficient evidence for developing public policy, they raise concerns about the possible impact a CFIUS review may have on the market and the potential costs of redefining the concept of national security relative to foreign investment.

Formal Actions

FINSA codified CFIUS, gave it statutory authority, and designated the Secretary of the Treasury to serve as the chairman. The measure followed the same pattern that had been set by Executive Order 11858. The formal process has clear deadlines for action:

- 30 days to conduct a review;

- 45 days to conduct an investigation; and

- 15 days for a

Presidentialpresidential determination.

At any point during the CFIUS process, parties can withdraw and refile their notice, for instance, to allow additional time to discuss CFIUS's proposed resolution of outstanding issues. Under FINSA, the President retained his authority as the only officer capable of suspending or prohibiting mergers, acquisitions, and takeovers, and the measure placed additional requirements on firms that resubmitted a filing after previously withdrawing a filing before a full review was completed.

National Security Review

During the 30-day review stage, the Director of National Intelligence (DNI), an ex officio member of CFIUS, is required to carry out a thorough analysis of "any threat to the national security of the United States" of any merger, acquisition, or takeover. This analysis is required to be completed "within 20 days" of the receipt of a notification by CFIUS, but the statute directs that the DNI must be given "adequate time," presumably if this national security review cannot be completed within the 20-day requirement. This analysis would include a request for information from the Department of the Treasury's Director of the Office of Foreign Assets Control and the Director of the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. In addition, the Director of National Intelligence is required to seek and to incorporate the views of "all affected or appropriate" intelligence agencies. CFIUS also is required to review "covered" investment transactions in which the foreign entity is owned or controlled by a foreign government, but the law provides an exception to this requirement. A review is exempted if the Secretary of the Treasury and certain other specified officials determine that the transaction in question will not impair the national security.

National Security Investigation

The President, acting through CFIUS, is required to conduct a National Securitynational security investigation and to take any "necessary" actions as part of the 45-day investigation if the review indicates that at least one of three conditions exists: (1) CFIUS determines that the transaction threatens to impair the national security of the United States and that the threat has not been mitigated during or prior to a review of the transaction; (2) the foreign person is controlled by a foreign government; or (3) the transaction would result in the control of any critical infrastructure by a foreign person, the transaction could impair the national security, and such impairment has not been mitigated. At the conclusion of the investigation or the 45-day review period, whichever comes first, the Committee can decide to offer no recommendation or it can recommend that the President suspend or prohibit the investment.

During a review or an investigation, CFIUS and a designated lead agency have the authority to negotiate, impose, or enforce any agreement or condition with the parties to a transaction in order to mitigate any threat to U.S. national security. Such agreements are based on a "risk-based analysis" of the threat posed by the transaction. Also, if a notification of a transaction is withdrawn before any review or investigation by CFIUS is completed, the amended law grants the Committee the authority to take a number of actions. In particular, the Committee could develop (1) interim protections to address specific concerns about the transaction pending a resubmission of a notice by the parties; (2) specific time frames for resubmitting the notice; and (3) a process for tracking any actions taken by any parties to the transaction.

Presidential Determination

FINSA grants the President the authority to block proposed or pending foreign "mergers, acquisitions, or takeovers" of "persons engaged in interstate commerce in the United States" that threaten to impair the national security. The President, however, is under no obligation to follow the recommendation of the Committee to suspend or prohibit an investment. Congress directed that before this authority can be invoked (1) the President must conclude that other U.S. laws are inadequate or inappropriate to protect the national security; and (2) the President must have "credible evidence" that the foreign investment will impair the national security. As a result, if CFIUS determines, as was the case in the Dubai Ports transaction, that it does not have credible evidence that an investment will impair the national security, then it may argue that it is not required to undertake a full 45-day investigation, even if the foreign entity is owned or controlled by a foreign government. After considering the two conditions listed above (other laws are inadequate or inappropriate, and he has credible evidence that a foreign transaction will impair national security), the President is granted almost unlimited authority to take "such action for such time as the President considers appropriate to suspend or prohibit any covered transaction that threatens to impair the national security of the United States." In addition, such determinations by the President are not subject to judicial review, although the process by which the disposition of a transaction is determined may be subject to judicial review, as was emphasized in the ruling by the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia in the case of Ralls vs. the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States.

Committee Membership

President Bush's January 23, 2008, Executive Order 13456 implementing FINSA made various changes to the law. The Committee consists of nine Cabinet members, including the Secretaries of State, the Treasury, Defense, Homeland Security, Commerce, and Energy; the Attorney General; the United States Trade Representative; and the Director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy.3332 The Secretary of Labor and the Director of National Intelligence serve as ex officio members of the Committee.3433 The Executive Order added five executive office members to CFIUS in order to "observe and, as appropriate, participate in and report to the President": the Director of the Office of Management and Budget; the Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors; the Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs; the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy; and the Assistant to the President for Homeland Security and Counterterrorism. The President can also appoint members on a temporary basis to the Committee as he determines.

Covered Transactions

The law requires CFIUS to review all "covered" foreign investment transactions to determine whether a transaction threatens to impair the national security, or the foreign entity is controlled by a foreign government, or it would result in control of any "critical infrastructure that could impair the national security." A covered foreign investment transaction is defined as any merger, acquisition, or takeover which results in "foreign control of any person engaged in interstate commerce in the United States." According to CFIUS, the FINSA law increased accountability in the way CFIUS conducts its reviews. Since the review process involves numerous federal government agencies with varying missions, CFIUS seeks consensus among the member agencies on every transaction. Any agency that has a different assessment of the national security risks posed by a transaction has the ability to push that assessment to a higher level within CFIUS and, ultimately, to the President. As a matter of practice, before CFIUS clears a transaction to proceed, each member agency confirms to Treasury, at politically accountable levels, that it has no unresolved national security concerns with the transaction. CFIUS is represented through the review process by Treasury and by one or more other agencies that Treasury designates as a lead agency based on the subject matter of the transaction. At the end of a review or investigation, CFIUS provides a written certification to Congress that it has no unresolved national security concerns. This certification is executed by Senate-confirmed officials at these agencies at either the Assistant Secretary- or Deputy Secretary- level, depending on the stage of the process at which the transaction is cleared.3534

According to Treasury Department regulations, investment transactions that are not considered to be covered transactions under FINSA and, therefore, not subject to a CFIUS review are those that are undertaken "solely for the purpose of investment," or an investment in which the foreign investor has "no intention of determining or directing the basic business decisions of the issuer." In addition, investments that are solely for investment purposes are defined as those (1) in which the transaction does not involve owning more than 10% of the voting securities of the firm; or (2) those investments that are undertaken directly by a bank, trust company, insurance company, investment company, pension fund, employee benefit plan, mutual fund, finance company, or brokerage company "in the ordinary course of business for its own account."3635

Other transactions that are not covered include (1) stock splits or a pro rata stock dividend that does not involve a change in control; (2) an acquisition of any part of an entity or of assets that do not constitute a U.S. business; (3) an acquisition of securities by a person acting as a securities underwriter, in the ordinary course of business and in the process of underwriting; and (4) an acquisition pursuant to a condition in a contract of insurance relating to fidelity, surety, or casualty obligations if the contract was made by an insurer in the ordinary course of business. In addition, the Treasury regulations also stipulate that the extension of a loan or a similar financing arrangement by a foreign person to a U.S. business will not be considered a covered transaction and will not be investigated, unless the loan conveys a right to the profits of the U.S. business or involves a transfer of management decisions.

Critical Infrastructure

A new element to the CFIUS process added by FINSA is the addition of "critical industries" and "homeland security" as broad categories of economic activity that could be subject to a CFIUS national security review, ostensibly broadening CFIUS's mandate. The precedent for this action was set in the Patriot Act of 2001 and the Homeland Security Act of 2002, which define critical industries and homeland security and assign responsibilities for those industries to various federal government agencies. FINSA references those two acts and borrows language from them on critical industries and homeland security. After the September 11th terrorist attacks Congress passed and President Bush signed the USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 (Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism).3736 In this act, Congress provided for special support for "critical industries," which it defined as

systems and assets, whether physical or virtual, so vital to the United States that the incapacity or destruction of such systems and assets would have a debilitating impact on security, national economic security, national public health or safety, or any combination of those matters.38

This broad definition is enhanced to some degree by other provisions of the act, which identify certain sectors of the economy that are likely candidates for consideration as components of the national critical infrastructure. These sectors include telecommunications, energy, financial services, water, transportation sectors,3938 and the "cyber and physical infrastructure services critical to maintaining the national defense, continuity of government, economic prosperity, and quality of life in the United States."4039 The following year, Congress adopted the language in the Patriot Act on critical infrastructure into The Homeland Security Act of 2002.41

In addition, the Homeland Security Act added key resources to the list of critical infrastructure (CI/KR) and defined those resources as "publicly or privately controlled resources essential to the minimal operations of the economy and government."4241 Through a series of directives, the Department of Homeland Security identified 17 sectors4342 of the economy as falling within the definition of critical infrastructure/key resources and assigned primary responsibility for those sectors to various federal departments and agencies, which are designated as Sector-Specific Agencies (SSAs).4443 On March 3, 2008, Homeland Security Secretary Chertoff signed an internal DHS memo designating Critical Manufacturing as the 18th sector on the CI/KR list.

In 2013, the list of critical industries was altered through a Presidential Policy Directive (PPD-21).4544 The directive listed three "strategic imperatives" as drivers of the Federal approach to strengthening "critical infrastructure security and resilience":

- 1. Refine and clarify functional relationships across the Federal Government to advance the national unity of effort to strengthen critical infrastructure security and resilience;

- 2. Enable effective information exchange by identifying baseline data and systems requirements for the Federal Government; and

- 3. Implement an integration and analysis function to inform planning and operations decisions regarding critical infrastructure.

The directive assigns the main responsibility to the Department of Homeland Security for identifying critical industries and coordinating efforts among the various government agencies, among a number of responsibilities. The directive also assigns roles to other agencies and designated 16 sectors as critical to the U.S. infrastructure. The sectors are (1) chemical; (2) commercial facilities; (3) communications; (4) critical manufacturing; (5) dams; (6) defense industrial base; (7) emergency services; (8) energy; (9) financial services; (10) food and agriculture; (11) government facilities; (12) healthcare and public health; (13) information technology; (14) nuclear reactors, materials, and waste; (15) transportation systems; and (16) water and wastewater systems.46

Foreign Ownership Control

The CFIUS statute itself does not provide a definition of the term "control," but such a definition is included in the Treasury Department's regulations. According to those regulations, control is not defined as a numerical benchmark,4746 but instead focuses on a functional definition of control, or a definition that is governed by the influence the level of ownership permits the foreign entity to affect certain decisions by the firm. According to the Treasury Department's regulations:

The term control means the power, direct or indirect, whether or not exercised, and whether or not exercised or exercisable through the ownership of a majority or a dominant minority of the total outstanding voting securities of an issuer, or by proxy voting, contractual arrangements or other means, to determine, direct or decide matters affecting an entity; in particular, but without limitation, to determine, direct, take, reach or cause decisions regarding:

(1) The sale, lease, mortgage, pledge or other transfer of any or all of the principal assets of the entity, whether or not in the ordinary course of business;

(2) The reorganization, merger, or dissolution of the entity;

(3) The closing, relocation, or substantial alternation of the production operational, or research and development facilities of the entity;

(4) Major expenditures or investments, issuances of equity or debt, or dividend payments by this entity, or approval of the operating budget of the entity;

(5) The selection of new business lines or ventures that the entity will pursue;

(6) The entry into termination or non-fulfillmentnonfulfillment by the entity of significant contracts;

(7) The policies or procedures of the entity governing the treatment of non-publicnonpublic technical, financial, or other proprietary information of the entity;

(8) The appointment or dismissal of officers or senior managers;

(9) The appointment or dismissal of employees with access to sensitive technology or classified U.S. Government information; or

(10) The amendment of the Articles of Incorporation, constituent agreement, or other organizational documents of the entity with respect to the matters described at paragraph (a) (1) through (9) of this section.

The Treasury Department's regulations also provide some guidance to firms that are deciding whether they should notify CFIUS of a proposed or pending merger, acquisition, or takeover. The guidance states that proposed acquisitions that need to notify CFIUS are those that involve "products or key technologies essential to the U.S. defense industrial base." This notice is not intended for firms that produce goods or services with no special relation to national security, especially toys and games, food products (separate from food production), hotels and restaurants, or legal services. CFIUS has indicated that in order to ensure an unimpeded inflow of foreign investment it would implement the statute "only insofar as necessary to protect the national security," and "in a manner fully consistent with the international obligations of the United States."48

Neither Congress nor the Administration has attempted to define the term "national security." Treasury Department officials have indicated, however, that during a review or investigation each CFIUS member is expected to apply that definition of national security that is consistent with the representative agency's specific legislative mandate.4948 The concept of national security was broadened by P.L. 110-49 to include, "those issues relating to 'homeland security,' including its application to critical infrastructure."

Factors for Consideration

The CFIUS statute includes a list of 12 factors the President must consider in deciding to block a foreign acquisition, although the President is not required to block a transaction based on these factors. Additionally, the CFIUS members consider the factors as part of their own review process to determine if a particular transaction threatens to impair the national security. This list includes the following elements:

(1) domestic production needed for projected national defense requirements;

(2) capability and capacity of domestic industries to meet national defense requirements, including the availability of human resources, products, technology, materials, and other supplies and services;

(3) control of domestic industries and commercial activity by foreign citizens as it affects the capability and capacity of the U.S. to meet the requirements of national security;

(4) potential effects of the transactions on the sales of military goods, equipment, or technology to a country that supports terrorism or proliferates missile technology or chemical and biological weapons; and transactions identified by the Secretary of Defense as "posing a regional military threat" to the interests of the United States;

(5) potential effects of the transaction on U.S. technological leadership in areas affecting U.S. national security;

(6) whether the transaction has a security-related impact on critical infrastructure in the United States;

(7) potential effects on United States critical infrastructure, including major energy assets;

(8) potential effects on United States critical technologies;

(9) whether the transaction is a foreign government-controlled transaction;

(10) in cases involving a government-controlled transaction, a review of (A) the adherence of the foreign country to nonproliferation control regimes, (B) the foreign country's record on cooperating in counter-terrorism efforts, (C) the potential for transshipment or diversion of technologies with military applications;

(11) long-term projection of the United States requirements for sources of energy and other critical resources and materials; and

(12) such other factors as the President or the Committee determine to be appropriate.50

Factors 6-12 were added through the FINSA Act potentially broadening the scope of CFIUS's reviews and investigations. Previously, CFIUS had been directed by Treasury Department regulations to focus its activities primarily on investments that had an impact on U.S. national defense security. The additional factors, however, incorporate economic considerations into the CFIUS review process in a way that was specifically rejected when the original Exon-Florio amendment was adopted and refocuses CFIUS's reviews and investigations on considering the broader rubric of economic security. In particular, CFIUS is now required to consider the impact of an investment on critical infrastructure as a factor for considering recommending that the President block or postpone a transaction. As previously indicated, critical infrastructure is defined in broad terms within FINSA as "any systems and assets, whether physical or cyber-based, so vital to the United States that the degradation or destruction of such systems or assets would have a debilitating impact on national security, including national economic security and national public health or safety."

As originally drafted, the Exon-Florio provision also would have applied to joint ventures and licensing agreements in addition to mergers, acquisitions, and takeovers. Joint ventures and licensing agreements subsequently were dropped from the proposal because the Reagan Administration and various industry groups argued at the time that such business practices were deemed to be beneficial arrangements for U.S. companies. In addition, they argued that any potential threat to national security could be addressed by the Export Administration Act5150 and the Arms Control Export Act.52

Confidentiality Requirements

The FINSA Act codified confidentiality requirements that are similar to those that appeared in the Exon-Florio amendment and Executive Order 11858 by stating that any information or documentary material filed under the provision may not be made public "except as may be relevant to any administrative or judicial action or proceeding."5352 The FINSA provision does state, however, that this confidentiality provision "shall not be construed to prevent disclosure to either House of Congress or to any duly authorized committee or subcommittee of the Congress." The provision provides for the release of proprietary information "which can be associated with a particular party" to committees only with assurances that the information will remain confidential. Members of Congress and their staff members will be accountable under current provisions of law governing the release of certain types of information. FINSA requires the President to provide a written report to the Secretary of the Senate and the Clerk of the House detailing his decision and his actions relevant to any transaction that was subject to a 45-day investigation.54

Mitigation and Tracking

Since the implementation of the Exon-Florio provision in the 1980s, CFIUS had developed several informal practices that likely were not envisioned when the statute was drafted. In particular, members of CFIUS on occasion negotiated conditions with firms to mitigate or to remove business arrangements that raised national security concerns among the CFIUS members. Such agreements often were informal arrangements that had an uncertain basis in statute and had not been tested in court. These arrangements often were negotiated during the formal 30-day review period, or even during an informal process prior to the formal filing of a notice of an investment transaction.

Under FINSA, CFIUS must designate a lead agency to negotiate, modify, monitor, and enforce agreements in order to mitigate any threat to national security. Such agreements are required to be based on a "risk-based analysis" of the threat posed by the transaction. CFIUS is also required to develop a method for evaluating the compliance of firms that have entered into a mitigation agreement or condition that was imposed as a requirement for approval of the investment transaction. Such measures, however, are required to be developed in such a way that they allow CFIUS to determine that compliance is taking place without also (1) "unnecessarily diverting" CFIUS resources from assessing any new covered transaction for which a written notice had been filed; and (2) placing "unnecessary" burdens on a party to an investment transaction.

If a notification of a transaction is withdrawn before any review or investigation by CFIUS is completed, CFIUS can take a number of actions, including (1) interim protections to address specific concerns about the transaction pending a resubmission of a notice by the parties; (2) specific time frames for resubmitting the notice; and (3) a process for tracking any actions taken by any party to the transaction. Also, any federal entity or entities that are involved in any mitigation agreement are to report to CFIUS if there is any modification that is made to any agreement or condition that had been imposed and to ensure that "any significant" modification is reported to the Director of National Intelligence and to any other federal department or agency that "may have a material interest in such modification." Such reports are required to be filed with the Attorney General.

Congressional Oversight

The FINSA Act significantly increased the types and number of reports that CFIUS is required to send to certain specified Members of Congress. In particular, CFIUS is required to brief certain congressional leaders if they request such a briefing and to report annually to Congress on any reviews or investigations it has conducted during the prior year. CFIUS provides a classified report to Congress each year and a less extensive report for public release. Each report is required to include a list of all concluded reviews and investigations, information on the nature of the business activities of the parties involved in an investment transaction, information about the status of the review or investigation, and information on any transactions that were withdrawn from the process, any roll call votes by the Committee, any extension of time for any investigation, and any presidential decision or action taken under FINSA. In addition, CFIUS is required to report on trend information on the numbers of filings, investigations, withdrawals, and presidential decisions or actions that were taken. The report must include cumulative information on the business sectors involved in filings and the countries from which the investments originated; information on the status of the investments of companies that withdrew notices and the types of security arrangements and conditions CFIUS used to mitigate national security concerns; the methods the Committee used to determine that firms were complying with mitigation agreements or conditions; and a detailed discussion of all perceived adverse effects of investment transactions on the national security or critical infrastructure of the United States.

The Secretary of the Treasury, in consultation with the Secretaries of State and Commerce, was directed to conduct a study on investment in the United States, particularly in critical infrastructure and industries affecting national security, by (1) foreign governments, entities controlled by or acting on behalf of a foreign government, or persons of foreign countries which comply with any boycott of Israel; or (2) foreign governments, entities controlled by or acting on behalf of a foreign government, or persons of foreign countries which do not ban organizations designated by the Secretary of State as foreign terrorist organizations. In addition, CFIUS is required to provide an annual evaluation of any credible evidence of a coordinated strategy by one or more countries or companies to acquire U.S. companies involved in research, development, or production of critical technologies in which the United States is a leading producer. The report must include an evaluation of possible industrial espionage activities directed or directly assisted by foreign governments against private U.S. companies aimed at obtaining commercial secrets related to critical technologies.

The Inspector General of the Department of the Treasury must investigate any failure of CFIUS to comply with requirements for reporting that were imposed prior to the passage of FINSA and to report the findings of this report to Congress. In particular, the report must be sent to the chairman and ranking member of each committee of the House and the Senate with jurisdiction over any aspect of the report, including the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, the House Committees on Foreign Affairs, Financial Services, and Energy and Commerce.

The chief executive officer of any party to a merger, acquisition, or takeover must certify in writing that the information contained in a written notification to CFIUS fully complies with the CFIUS requirements and that the information is accurate and complete. This written notification would also include any mitigation agreement or condition that was part of a CFIUS approval.

Recent CFIUS Reviews

According to the annual report filed by CFIUS,5554 CFIUS activity dropped sharply in 2009 as a result of tight credit markets and hesitation by banks to fund acquisitions and takeovers during the global financial crisis, but rebounded in 2010, as indicated in Table 2. During the seveneight-year period 2008-20142015 (the latest years for which such data are available), foreign investors sent 782925 notices to CFIUS of plans to acquire, take over, or merge with a U.S. firm. In comparison, the Commerce Department reports there were over 1,800 foreign investment transactions in 2015, slightly less than half of which were acquisitions of existing U.S. firms. Acquisitions, however, accounted for 96% of the total annual value of foreign direct investments.5655 Of the investment transactions that were notified during the 2008-20142015 period, about 64% were withdrawn during the initial 30-day review; about 3136% of the total notified transactions required a 45-day investigation. Also, of the transactions that were investigated, about 76% were withdrawn before a final determination was reached. As a result, of the 782925 proposed investment transactions notified to CFIUS during this period, 700822 transactions, or 9089% of the transactions, were completed. The CFIUS report also indicates that a presidential decision was made in one of the transactions, the Ralls CorpCorporation acquisition of wind farm assets from Terna Energy SA (discussed in a later section of this report). President Obama blocked a Chinese investment firm in 2016 from acquiring Aixtron, a Germany-based firm with assets in the United States. In 2017, President Trump blocked the acquisition of Lattice Semiconductor Corp. by the Chinese investment firm Canyon Bridge Capital Partners.

|

Year |

Number of Notices |

Notices Withdrawn During Review |

Number of Investigations |

Notices Withdrawn During Investigation |

Presidential Decisions |

|||||||

|

2008 |

155 |

18 |

23 |

5 |

0 |

|||||||

|

2009 |

65 |

5 |

25 |

2 |

0 |

|||||||

|

2010 |

93 |

6 |

35 |

6 |

0 |

|||||||

|

2011 |

111 |

1 |

40 |

5 |

0 |

|||||||

|

2012 |

114 |

2 |

45 |

20 |

1 |

|||||||

|

2013 |

97 |

3 |

48 |

5 |

0 |

|||||||

|

2014 |

147 |

3 |

51 |

9 |

0 |

|||||||

|

Total |

782 |

3 |

267 |

43

|

66

|

10

|

0

|

Total

|

925

|

41

|

333 62 |

1 |

Source: Annual Report to Congress, Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, February 2016September 2017.

Note: Three additional foreign investment transactions have been blocked by presidential order.

The CFIUS report also indicates that 4243% of the foreign investment transactions that were notified to CFIUS from 2008 to 20142015 were in the manufacturing sector. Investments in the finance, information, and services sectors accounted for another 31% of the total notified transactions, as indicated in Table 3. Within the manufacturing sector, more than 4043% of all the investment transactions notified to CFIUS between 2013 and 2015 were in the computer and electronic products sectors, a share that rose to 49% in 2015. The next three. The next two sectors with the highest number of transactions were the transportation equipment sector and the machinery sector. Investment transactions in the services sector accounted for about half of the total number of investment transactions in the finance, information, and services category, which was recorded at 12% in the 2013-2015 period and in 2015, the machinery sector, which fell from 13% in the 2013-2015 period to 12% in 2015, and the electrical equipment and computer sector, which fell from 11% of manufacturing transactions in 2013-2015 to 3% in 2015. Within the finance, information, and services sector, professional services accounted for 20% of transactions 2015, down from 37% recorded in the 2013-2015 period. Notified transactions in publishing (21%), telecommunications (17%), and real estate (10%) comprised the next most active sectors.

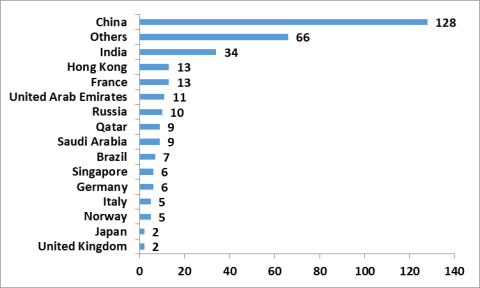

Table 4 shows foreign investment transactions by the home country of the foreign investor and the industry composition of the investment transactions. According to data based on notices provided to CFIUS by foreign investors, Chinese investors were the most active in acquisitions, takeovers, or mergers during the 2012-20142013-2015 period, accounting for 19% of the total number of transactions. The United Kingdom and Canada join China as the top three countries of origin for investors providing notifications to CFIUS. InFor China and the UK, investmentsinvestment notifications were concentrated in the manufacturing and finance, information, and services sectors, although nearly one-thirdfifth of Chinese transactions were in the mining, construction, and utilities sectors. The ranking of countries in Table 4 differs in a number of important ways from data published by the Bureau of Economic Analysis on the cumulative amount, or the total book value, of foreign direct investment in the United States, which places the United Kingdom, Japan, the Netherlands, Germany, Canada, and Switzerland as the most active countries of origin for foreign investment in the United States.

|

Year |

Manufacturing |

Finance, Information, and Services |

Mining, Utilities, and Construction |

Wholesale and Retail Trade |

Total |

|||||

|

2008 |

72 |

42 |

25 |

16 |

155 |

|||||

|

2009 |

21 |

22 |

19 |

3 |

65 |

|||||

|

2010 |

36 |

35 |

13 |

9 |

93 |

|||||

|

2011 |

49 |

38 |

16 |

8 |

111 |

|||||

|

2012 |

47 |

36 |

23 |

8 |

114 |

|||||

|

2013 |

35 |

32 |

20 |

10 |

97 |

|||||

|

2014 |

69 |

38 |

25 |

15 |

147

|

2015

|

68

|

42

|

21

|

12 143 |

|

Total |

329 |

2 |

1 |

69 |

782 |

Source: Annual Report to Congress, Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, February 2016September 2017.

|

Country |

Manufacturing |

Finance, Information, and Services |

Mining, Utilities, and Construction |

Wholesale Trade and Retail Trade |

Total |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

China |

33 15 |

13 |

7 74 Canada 9 9 |

3 |

68 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

United Kingdom |

25 15 3 4 47 Japan 20 12 | 16 |

5 |

4 |

45 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Canada |

4 |

6 |

20 |

10 |

40 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Japan

|

9 5 |

18 |

10 |

5 Netherlands |

4 |

37

|

2

|

0 14 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

France 10 |

12 |

8 |

0 |

3 | 21

|

Singapore

|

3

|

5

|

3

|

1 12 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Germany |

10 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

17 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Switzerland |

13 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

15 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Netherlands |

4 |

9

|

1

|

2

|

4

|

1

|

8 South Korea |

2 |

0 |

15 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Singapore |

2 |

3 |