U.S. Sanctions and Russia’s Economy

In response to Russia’s annexation of the Crimean region of neighboring Ukraine and its support of separatist militants in Ukraine’s east, the United States imposed a number of targeted economic sanctions on Russian individuals, entities, and sectors. The United States coordinated its sanctions with other countries, particularly the European Union (EU). Russia retaliated against sanctions by banning imports of certain agricultural products from countries imposing sanctions, including the United States.

U.S. policymakers are debating the use of economic sanctions in U.S. foreign policy toward Russia, including whether sanctions should be kept in place or further tightened. A key question in this debate is the impact of the Ukraine-related sanctions on Russia’s economy and U.S. economic interests in Russia.

Economic Conditions in Russia

Russia faced a number of economic challenges in 2014 and 2015, including capital flight, rapid depreciation of the ruble, exclusion from international capital markets, inflation, and domestic budgetary pressures. Growth slowed to 0.7% in 2014 before contracting sharply by 3.7% in 2015. The extent to which U.S. and EU sanctions drove the downturn is difficult to disentangle from the impact of a dramatic drop in the price of oil, a major source of export revenue for the Russian government, or economic policy decisions by the Russian government.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimated in 2015 that U.S. and EU sanctions in response to the conflict in Ukraine and Russia's countervailing ban on agricultural imports reduced Russian output over the short term by as much as 1.5%. Russia's economy, more recently, is showing some signs of recovery, in part due to higher oil prices, a flexible exchange rate regime, and sizeable foreign exchange reserves, among other factors. The IMF projects Russia’s economy will grow by 1.1% in 2017.

U.S. Economic Interests

When the sanctions were announced in 2014, U.S. business groups raised concerns that sanctions harm American manufacturers, jeopardize American jobs, and cede business opportunities to firms from other countries. When the sanctions were rolled out in 2014, news reports cited a number of U.S. firms that were adversely affected by U.S. sanctions on Russia and Russia’s retaliatory measures. There are questions about the overall impact of the sanctions on the U.S. economy, however. Russia accounts for a small portion of total U.S. trade and foreign investment. U.S. sanctions also target specific Russian individuals and entities and, in some cases, restrict only specific types of economic transactions.

U.S. Sanctions and Russia's Economy

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- U.S. Sanctions in Response to the Ukraine Conflict

- Economic Implications for Russia

- Recent Trends in Russia's Economy

- Estimates of the Sanctions' Impact on the Russian Economy

- U.S. Economic Interests

- U.S.-Russia Trade and Investment Relations

- U.S.-Russia Economic Ties at the Firm Level

- Conclusion

Summary

In response to Russia's annexation of the Crimean region of neighboring Ukraine and its support of separatist militants in Ukraine's east, the United States imposed a number of targeted economic sanctions on Russian individuals, entities, and sectors. The United States coordinated its sanctions with other countries, particularly the European Union (EU). Russia retaliated against sanctions by banning imports of certain agricultural products from countries imposing sanctions, including the United States.

U.S. policymakers are debating the use of economic sanctions in U.S. foreign policy toward Russia, including whether sanctions should be kept in place or further tightened. A key question in this debate is the impact of the Ukraine-related sanctions on Russia's economy and U.S. economic interests in Russia.

Economic Conditions in Russia

Russia faced a number of economic challenges in 2014 and 2015, including capital flight, rapid depreciation of the ruble, exclusion from international capital markets, inflation, and domestic budgetary pressures. Growth slowed to 0.7% in 2014 before contracting sharply by 3.7% in 2015. The extent to which U.S. and EU sanctions drove the downturn is difficult to disentangle from the impact of a dramatic drop in the price of oil, a major source of export revenue for the Russian government, or economic policy decisions by the Russian government.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimated in 2015 that U.S. and EU sanctions in response to the conflict in Ukraine and Russia's countervailing ban on agricultural imports reduced Russian output over the short term by as much as 1.5%. Russia's economy, more recently, is showing some signs of recovery, in part due to higher oil prices, a flexible exchange rate regime, and sizeable foreign exchange reserves, among other factors. The IMF projects Russia's economy will grow by 1.1% in 2017.

U.S. Economic Interests

When the sanctions were announced in 2014, U.S. business groups raised concerns that sanctions harm American manufacturers, jeopardize American jobs, and cede business opportunities to firms from other countries. When the sanctions were rolled out in 2014, news reports cited a number of U.S. firms that were adversely affected by U.S. sanctions on Russia and Russia's retaliatory measures. There are questions about the overall impact of the sanctions on the U.S. economy, however. Russia accounts for a small portion of total U.S. trade and foreign investment. U.S. sanctions also target specific Russian individuals and entities and, in some cases, restrict only specific types of economic transactions.

Introduction

Over the course of 2014, the U.S. government rolled out targeted economic sanctions on Russian individuals and entities in critical commercial sectors in response to that country's annexing of the Crimean region of neighboring Ukraine and its support of separatist militants in Ukraine's east.1 Designed to change behavior of the Russian government by putting pressure on the Russian economy, sanctions include asset freezes for specific Russian individuals and entities; restrictions on financial transactions with Russian firms operating in key sectors; restrictions on U.S. exports, services, and technology for specific Russian oil exploration or production projects; and tighter restrictions on U.S. exports of dual-use and military items to Russia.

The United States coordinated its sanctions with other countries, particularly with the European Union (EU). Russia retaliated against sanctions by banning imports of certain agricultural products from countries imposing sanctions, including the United States.

U.S. policymakers are debating the use of economic sanctions in U.S. foreign policy toward Russia, including whether sanctions should be kept in place or further tightened. For example, in the Senate, legislation has been introduced to impose additional sanctions in response to Russia's alleged hacking of U.S. persons and institutions, including U.S. political organizations, and other aggressive actions, including in Ukraine (S. 94), and to provide congressional oversight of actions that would limit Russia sanctions (S. 341, H.R. 1059). Legislation has also been introduced in the House to tighten sanctions, for example by prohibiting certain transactions in areas controlled by Russia (H.R. 830), and to prohibit U.S. recognition of Russian sovereignty over Crimea (H.R. 463). Some Members of Congress have proposed codifying existing sanctions, which could make them more difficult to ease or remove.2 Most of the current restrictions were put in place by President Barak Obama issuing Executive Orders under emergency authorities.

On February 2, 2017, U.N. Ambassador Nikki Haley opened her first public remarks by referring to a recent flare-up of violence in Ukraine, noting that "the dire situation in eastern Ukraine is one that demands clear and strong condemnation of Russian actions." She stated that "the United States continues to condemn and call for an immediate end to the Russian occupation of Crimea" and that "Crimea-related sanctions will remain in place until Russia returns control of the peninsula to Ukraine."3

A key question in this debate is the impact of the Ukraine-related sanctions on Russia's economy and U.S. economic interests in Russia. The subsequent discussion on recent economic trends in Russia and U.S. economic ties with Russia may provide insight.

U.S. Sanctions in Response to the Ukraine Conflict

The Obama Administration first imposed sanctions relating to the events in Ukraine in March 2014, and announced additional sanctions over subsequent months, working in coordination with the EU. The Obama Administration explained that the targeted sanctions on specific individuals, firms, and sectors "aim to increase Russia's political isolation as well as the economic costs to Russia, especially in areas of importance to President Putin and those close to him."4

In 2014, Congress also passed, and President Obama signed into law, the Support for the Sovereignty, Integrity, Democracy, and Economic Stability of Ukraine Act of 2014 (P.L. 113-95; 22 U.S.C. 8901 et seq.) and the Ukraine Freedom Support Act of 2014 (P.L. 113-272; 22 U.S.C. 8921 et seq.). These acts contain provisions on U.S. sanctions in response to the conflict in Ukraine.5

U.S. sanctions on Russia in response to the Ukraine conflict include the following:

- Asset freezes and prohibitions against transactions with specific Russian individuals. The U.S. government has frozen assets under U.S. jurisdiction and prohibited U.S. persons from engaging in transactions with a number of Russian individuals, including Russian officials, deputies, businesspeople, and associates with ties to the Kremlin.

- Asset freezes and prohibitions against transactions with specific entities. Some Russian companies are subject to U.S. asset freezes and are prohibited from engaging in economic transactions with U.S. individuals and entities. Examples include Bank Rossiya, which has been called the "personal bank of Putin"; the Volga Group, a holding company owned by a close ally of Putin; and Almaz-Antey, a state-owned defense company.6

- Restrictions on financial transactions with Russian firms operating in key sectors. Sanctions target sectors in Russia's financial services, energy, and defense sectors. U.S. individuals and entities face restrictions on select financial transactions, such as prohibitions on extending new debt with maturities longer than 30 or 90 days (depending on the sector). Examples of Russian firms subject to these sanctions include Rosoboronexport, a state-owned arms exporter; Rosneft, a state-owned oil company and the world's largest publicly traded oil producer; Rostec, a major Russian hi-tech and defense conglomerate; and Sberbank, the largest bank in Russia.

- Restrictions on specific oil-related exports, services, and technology to Russia. The United States restricts U.S. individuals and entities from exporting goods, services, or technology in support of exploration or production for deepwater, Artic offshore, or shale projects that have the potential to produce oil in Russia or in the maritime area claimed by Russia.

- Restrictions on specific exports. The United States has tightened restrictions on U.S. exports of dual-use and military items to Russia.

The United States urged other countries to impose sanctions on Russia, and coordinated sanctions with a number of other countries, particularly in the EU. In August 2014, Russia announced a retaliatory ban on the import of certain foods from the United States, the EU, and other countries imposing sanctions.

In 2014, the United States and other countries also began opposing new projects in Russia at the World Bank and European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), to put additional pressure on the Russian government in response to Russia's actions in Ukraine.7 Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States suspended the G-8 and instead resumed convening as the G-7, of which Russia is not a member, for the first time since the late 1990s. Russian officials still attend G-20 meetings, which include a broader group of advanced and emerging-market economies.8

|

Sanctions, Retaliatory Measures, and the World Trade Organization Some Russian officials have argued that Western sanctions in response to the conflict in Ukraine breach the rules and principles of the World Trade Organization (WTO).9 Similarly, some U.S. and European officials have questioned whether Russia's ban on agricultural imports from the United States, the EU, and other countries is a violation of WTO rules. Neither side, however, has initiated any formal proceedings under the WTO dispute settlement process with regards to the sanctions or retaliatory measures. Some analysts argue that such measures are permitted under the WTO's national security exemption.10 |

Economic Implications for Russia

U.S. and EU sanctions on Russian individuals, firms, and sectors in 2014 came at a time when Russia's economy was still struggling to recover from the global financial crisis of 2008-2009. In the early 2000s, Russia's economy benefited from rising oil prices. Its economy was hit hard by the global financial crisis and ensuing global economic downturn, as demand for its exports fell, particularly in Europe. Russia's economy contracted sharply, by 7.8%, in 2009.11 The economy rebounded the following year, growing by 4.5%, before slowing between 2010 and 2013. Economists argue that the financial crisis and weak economic performance highlighted fundamental problems in Russia's economy, including the economy's dependence on the production and export of oil and gas, as well as the need for reform in a number of areas, including governance (including the need to address corruption), regulation, privatization, competition, the banking sector, and utility pricing.12

Recent Trends in Russia's Economy

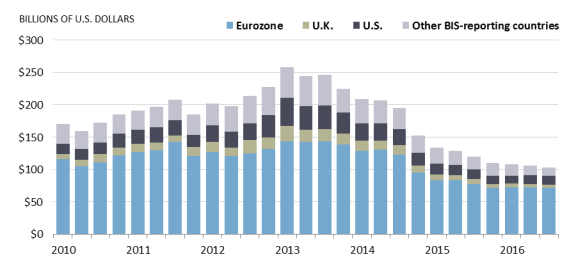

It is difficult to assess whether, and to what extent, the targeted U.S. and EU sanctions in response to the conflict in Ukraine, and Russia's retaliatory measures, have impacted the Russian economy broadly over the past two to three years. Sanctions hit at the same time the price of oil, a major export and source of revenue for the Russian government, dropped dramatically, by more than 60% between the start of 2014 and the end of 2015.13 That said, many economists, including at the IMF, have argued that the twin shocks of multilateral sanctions and low oil prices were the major driver behind Russia's economic challenges in 2014 and 2015 (Figure 1).14 In particular, Russia grappled with

- economic contraction, with growth slowing to 0.7% in 2014, before contracting sharply by 3.7% in 2015;

- capital flight, with net private capital outflows from Russia totaling $152 billion in 2014, compared to $61 billion in 2013;

- rapid depreciation of the ruble, more than 50% against the dollar over the course of 2015;

- a higher rate of inflation, from 6.8% in 2013 to 15.5% in 2015;

- budgetary pressures, with the budget deficit widening to 3.2% in 2015, up from 0.9% in 2013;

- tapping international reserve holdings to offset fiscal challenges, including exclusion from international capital markets, as reserves fell from almost $500 billion at the start of 2014 to $368 billion at the end of 2015; and

- more widespread poverty, which increased by 3.1 million to 19.2 million in 2015 (13.4% of the population).15

|

|

Source: Created by CRS using data from the IMF World Economic Outlook and the Bank of Russia. Note: GDP growth, inflation, and government budget graphs compare IMF forecasts from April 2014 with IMF forecasts from October 2016. |

During 2016, Russia's economy largely stabilized, even as the sanctions remained in place. Russia's economy contracted at a slower rate (0.8%); net private sector capital outflows slowed, from over $150 billion in 2014 to $15 billion in 2016; inflation fell by more than half, to 7.2%; the value of the ruble stabilized; and the government successfully sold new bonds in international capital markets in May 2016 for the first time since the sanctions were imposed.

Russia's economy benefited from rising oil prices in 2016, from about $30/barrel to over $50/barrel.16 Additionally, the IMF argued that the sanctions and oil shocks were cushioned by a flexible exchange rate regime, which allowed the ruble to depreciate and support exports; banking sector capital and liquidity injections; regulatory forbearance for the banking sector, to help banks avoid regulatory triggers due to acute ruble depreciation and volatile securities market prices; and limited fiscal stimulus, particularly tapping the reserve fund to finance deficit spending, which reached 3.7% in 2016.17 Unemployment has remained broadly stable, at around 5.6%, and poverty is projected around 14.6% in the first half of 2016.18

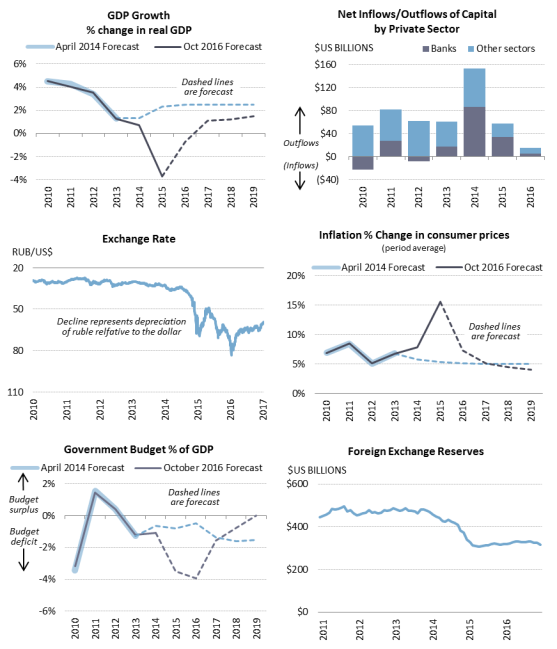

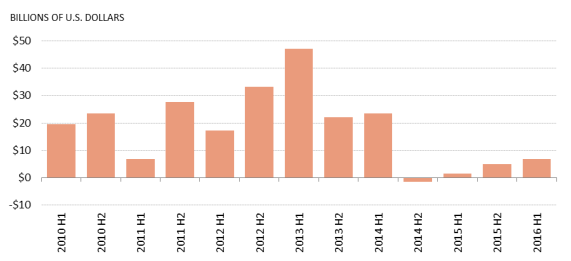

Although the economy is no longer in acute crisis, Russia's access to foreign capital remains limited. For countries reporting banking data to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), foreign bank loans to Russia (including private and public sectors) have fallen by more than half between the end of 2013 and the third quarter of 2016, from $225 billion to $103 billion (Figure 2).19 However, there is also some evidence that investor sentiment for Russia is improving. Russia's government has been able to resume bond sales in international capital markets, and net private capital outflows have slowed. Additionally, net inward FDI into Russia, which essentially came to a halt in late 2014 and early 2015, has started to resume, although it has not reached pre-2014 levels (Figure 3). News reports indicate that some major Western companies, such as Ikea, Pfizer, and Mars (food products), are looking to open new stores and factories in Russia.20

According to the IMF, Russia's economy is projected to resume modest growth of 1.1% in 2017 and 1.2% in 2018. The IMF argues that the medium-term prospects for Russia's economy are subdued due to the impact of sanctions on productivity and investment, as well as a number of unrelated long-standing structural challenges, including slow economic diversification, weak protection of property rights, burdensome administrative procedures, state involvement in the economy, corruption, and adverse demographic dynamics (declining population and lower labor force participation).21 Some analysts have also noted that the low value of the ruble may hamper Russia's attempts to innovate and modernize its economy, and that the economy's continued reliance on oil makes it vulnerable to another drop in oil prices.22

|

Figure 3. Inward Foreign Direct Investment in Russia Net Inflows |

|

|

Source: Created by CRS from Central Bank of Russia data. |

Estimates of the Sanctions' Impact on the Russian Economy

Some analysts have used statistical models to estimate the precise impact of sanctions imposed by the United States, the EU, and other countries on Russian individuals, firms, and sectors since 2014 relative to other factors, including oil prices. In 2015, the IMF estimated that U.S. and EU Ukraine-related sanctions and Russia's retaliatory ban on agricultural imports reduced output in Russia over the short term between 1.0% and 1.5%.23 The IMF's models suggest that the effects on Russia over the medium term could be more substantial, reducing output by up to 9%, as lower capital accumulation and technological transfers weaken already declining productivity growth. At the start of 2016, a State Department official argued that sanctions were not designed to push Russia "over the economic cliff" in the short run, but are designed to exert long-term pressure on Russia.24

In November 2014, Russian Finance Minister Anton Siluanov estimated the annual cost of sanctions to the Russian economy at $40 billion (2% of GDP), compared to $90 billion to $100 billion (4% to 5% of GDP) lost due to lower oil prices.25 Similarly, Russian economists estimated that the financial sanctions would decrease Russia's GDP by 2.4% by 2017, but the effect would be 3.3 times lower than the effect from the oil price shock.26

Russian President Vladimir Putin stated in November 2016 that the sanctions are "severely harming Russia" in terms of access to international financial markets, although the impact is not as severe as the harm from the decline in energy prices.27 Some analysts have noted that sanctions do not prohibit the Russian government from selling government bonds to Western investors, and as the Russian government resumes bond sales in international capital markets, it may lend the money on to sanctioned entities, easing their access to financing.28

In December 2016, the Office of the Chief Economist at the U.S. State Department published estimates of the impact of the U.S. and EU sanctions in 2014 on a firm-level basis.29 The main finding is that the average sanctioned company or associated company in Russia lost about one-third of its operating revenue, over one-half of its asset value, and about one-third of its employees relative to non-sanctioned peers. Their research also suggests that sanctions had a relatively smaller impact on Russia's economy overall (Russian GDP and import demand) compared to oil prices.

U.S. Economic Interests

There is debate about the economic impact of the Ukraine-related sanctions for the United States. When the sanctions were announced, U.S. business groups, including the Chamber of Commerce and the National Association of Manufacturers, raised concerns that U.S. sanctions on Russia could disrupt the operations of U.S. firms in Russia, thereby harming American manufacturers, jeopardizing American jobs, and ceding business opportunities to firms from other countries.30

Other analysts argued that the targeted sanctions were designed to minimize the impact on the U.S. economy while meeting foreign policy obligations to Europe and Ukraine and advancing U.S. national security interests. They note that Russia is a relatively minor trading and investment partner for the United States as a whole. Additionally, sanctions do not prohibit all economic transactions between the United States and Russia. They target a small portion of Russian individuals and entities and, in some cases, only restrict specific types of economic transactions.

U.S.-Russia Trade and Investment Relations

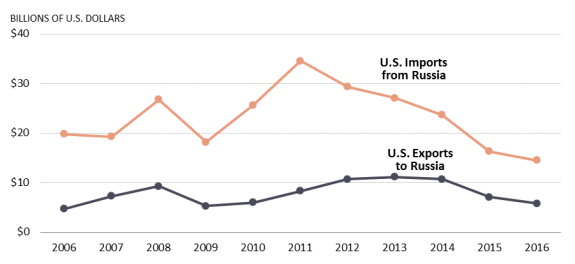

Although Russia is a major player in the international economy—it is the world's 12th-largest economy, is home to a population of more than 140 million, and is a major producer and exporter of natural gas and oil—U.S.-Russia economic ties have been historically relatively limited.31 Russia accounts for a small portion of overall U.S. international economic activity. Even before the Ukraine-related sanctions were imposed, the United States had little direct trade and investment with Russia. Over the past decade, Russia has accounted for less than 2% of total U.S. merchandise imports, less than 1% of total U.S. merchandise exports, less than 1% of U.S. foreign direct investment (FDI), and less than 1% of FDI in the United States.32

|

|

Source: Created by CRS using U.S. Census Bureau data, as accessed from Global Trade Atlas. |

Over the past three years, U.S. commodity trade with Russia has fallen by almost half (Figure 4). U.S. merchandise exports to Russia fell from $11.1 billion in 2013 to $5.8 billion in 2016. U.S. merchandise imports from Russia fell from $27.1 billion in 2013 to $14.5 billion in 2016. U.S. investment ties with Russia also continued to weaken. U.S. investment in Russia was $9.2 billion in 2015, and down from a peak of $20.8 billion in 2009.33 Russian investment in the United States was $4.5 billion, down from a peak of $8.4 billion in 2009.

It is difficult to assess the extent to which the downward trend in U.S. trade and investment with Russia was driven by the Ukraine-related sanctions. The sanctions target specific transactions with specific Russian individuals, firms, and sectors. Many trade and investment transactions between U.S. and Russian individuals and entities are not directly impacted by sanctions. Other factors may have driven the downturn, such as the economic contraction in Russia, structural problems in Russia's economy, or an inward-looking policy shift by the Russian government.34 Factors in the U.S. economy could also be at play, such as strengthening in the value of the U.S. dollar.

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of data from Global Trade Atlas, Bank for International Settlements, and Bank of Russia. |

|

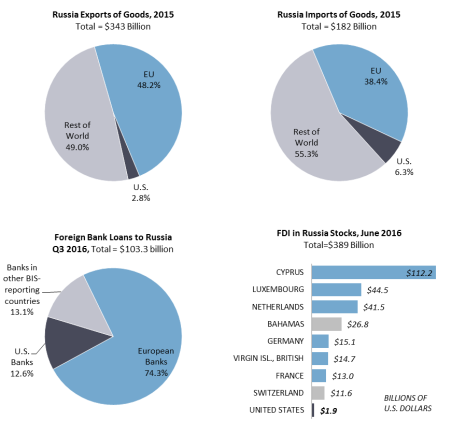

EU-Russian Economic Ties Russia has a much stronger economic relationship with Europe than with the United States (Figure 5). In 2015, nearly 50% of Russia's exports of goods went to EU member countries, compared to less than 3% to the United States. Nearly 40% of Russia's imports of goods came from EU member countries, compared to about 6% from the United States. In the financial sector, European banks accounted for about 75% of Russia's foreign bank loans in the third quarter of 2016 for countries reporting data to the BIS. Russia is also important economically to Europe, including as a supplier of natural gas and oil. The close economic relationship between Russia and the EU is one reason why analysts have argued that U.S.-EU cooperation on sanctions with Russia is critical for their success, but at times has created debate about the sanctions among European leaders. |

U.S.-Russia Economic Ties at the Firm Level

Several large U.S. companies have been actively engaged with Russia: exporting to Russia, entering joint ventures with Russian partners, and relying on Russian suppliers for inputs. A notable example is ExxonMobil, which in 2011 signed a strategic cooperation agreement with Rosneft, the Russian state-owned oil company, to drill in the Russian Arctic, among other activities now subject to sanctions.35 Other examples include PepsiCo, the largest food and beverage company in Russia; Ford Motor Co., which has a partnership with Sollers, a Russian car company; General Electric, which has joint ventures with Russian firms to manufacture gas turbines; Boeing, among the top U.S. exporters to Russia; Visa and MasterCard, which provide payment services to 90% of the Russian market; and United Launch Alliance, a Lockheed Martin and Boeing joint venture, which imports Russian rocket engines.36 Russia is also an important market for Philip Morris and Avon Products.37 The U.S.-Russia Business Council, a Washington-based trade association that provides services to U.S. and Russian member companies, has a membership of 170 U.S. companies conducting business in Russia.38

When new U.S. sanctions on Russia were implemented in 2014 in response to the conflict in Ukraine, news reports cited a number of U.S. firms whose operations were disrupted. For example, sanctions forced ExxonMobil to suspend its $700 million exploration in Russia's Kara Sea (a joint venture with Rosneft).39 During the first seven months of sanctions, Exxon reported losses amounting to about $1 billion from its Russian operations.40 Oilfield service companies, including Halliburton and National Oilwell Varco, reported that sanctions restricted their operations in Russia and expressed concern that sanctions will limit their profits.41 Likewise, John Deere, which makes heavy farm equipment and has two factories in Russia, attributed weaker sales to the sanctions.42 U.S. gun dealers also face restrictions on imports of Russian-made Kalashnikov rifles, of which they have reportedly sold tens of thousands in previous years.43 Additionally, U.S. financial institutions have reportedly needed to hire additional legal and technical staff to monitor accounts and review any financing arrangements with Russian entities.44

It is difficult to extrapolate the full impact of sanctions on U.S. firms from these examples. One reason is that Russia may not be a critical economic partner for some U.S. firms and industries affected by the sanctions. For example, in response to the sanctions, Russia announced plans to accelerate the development of its own national payments system, which would undermine MasterCard and Visa's dominance in the Russian market.45 Although no such system has been rolled out to date, Russia only accounts for a small portion (2%) of MasterCard's and Visa's profits.46 In at least one case following the new sanctions, a U.S. subsidiary of a Russian company cut ties with the parent company and relocated manufacturing to the United States.47

Another factor is that the implementation of sanctions in phases or "rounds" gave U.S. companies some time to prepare for disruptions in economic transactions with Russia. According to news reports, many multinational companies have developed contingency plans that would allow them to adjust to suppliers and banks outside of Russia and minimize the impact of sanctions on their operations.48 There is likely less press coverage of U.S. firms that have been able to minimize the impact of the sanctions on Russia or the effects of Russian retaliation.

Moreover, aggregate trade and investment trends mask differences at the firm and sector level. Although trade in most sectors has declined, in some cases, ties strengthened. For example, U.S. imports of aluminum from Russia increased by $536 million (68%) between 2014 and 2016.49

Some U.S. agricultural producers have been adversely affected by Russia's retaliatory ban on agricultural imports. Although Russia accounted for about 1% of the United States' total food and agricultural exports at the time the ban was imposed, specific producers within the United States have been adversely affected. For example, the congressional delegation from Alaska expressed concerns about the impact on Alaska's seafood industry.50 Another example is Washington State apple and pear producers, who sold $23 million worth of pears and apples to Russia in 2013 and had to locate new purchasers at the start of the new harvest season.51 Over the longer term, however, the impact of the sanctions could be mitigated in part as alternative markets for U.S. agricultural exports are located. For example, even though Russia's ban on agricultural imports impacted the U.S. poultry sector, which exported about $300 million to Russia a year, the industry downplayed the impact of the ban, stressing that Russia had already become a less important export market.52

|

In Response to Sanctions, Is Russia Turning to Emerging Markets? Some U.S. stakeholders are concerned that sanctions will cause Russia to turn away from U.S. companies and seek alternative economic partners, particularly in emerging markets (which have not imposed sanctions on Russia).53 There is some evidence to support this concern. For example, in October 2014, Russia and China completed approximately 40 agreements related to finance and technology.54 Russia is also reportedly turning to Brazil and other Latin American countries for food imports to compensate for losses resulting from its ban on agricultural imports from other countries.55 However, total Russian exports of goods to other key emerging markets, including Brazil, China, and India, fell between 2013 and 2015. Additionally, it is also not clear whether and to what extent these relationships would continue in the absence of U.S. sanctions on Russia. |

Conclusion

The United States, in coordination with the EU, implemented targeted sanctions on key Russian individuals, entities, and sectors in response to Russia's actions in Ukraine. U.S. sanctions include, for example, targeting officials in Putin's inner circle and placing restrictions on new debt to specific financial institutions. As Congress evaluates U.S. foreign policy toward Russia and the role that sanctions may or may not play in advancing U.S. national security interests, it may consider the impact of current economic sanctions on Russia's economy and foreign policy, in addition to their impact on U.S. foreign policy and economic interests.

Russia's economy faced a number of challenges in 2014 and 2015, including capital flight, depreciation of the ruble, rising inflation, weaker growth prospects, and budgetary pressures. Many experts believe that sanctions are contributing to Russia's economic challenges. However, it is difficult to assess the impact of sanctions separate from other domestic and international factors, particularly low oil prices. The effectiveness of the sanctions in inducing a change in the behavior of the Russian government remains to be seen. Although the Russian government continues to face a number of economic challenges, many of which are unrelated to sanctions, economic forecasts suggest that the Russian economy is stabilizing and there is some evidence that investor sentiment toward Russia may be improving.

Some U.S. business groups have raised concerns about the economic costs of sanctions on Russia to the United States. News reports indicate that some U.S. firms and industries have been adversely affected. Longer-term, the impact of the sanctions, if they are kept in place, may depend on a number of factors, such as the ability of U.S. firms to find alternative markets, potential spillover effects from a slowdown in Russia, and whether Russia implements additional retaliatory measures against the United States.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

Amber Wilhelm, Visual Information Specialist, helped prepare the figures.

Footnotes

| 1. |

For more information on Ukraine-related sanctions, see CRS In Focus IF10552, U.S. Sanctions on Russia Related to the Ukraine Conflict, coordinated by Cory Welt. A number of Russian individuals and entities are also subject to economic sanctions related to human rights violations, corruption, conflict in Syria, terrorism, transnational crime, and weapons proliferation. For more information on the different types of sanctions on Russia individuals and entities, see CRS Insight IN10634, Overview of U.S. Sanctions Regimes on Russia, by Cory Welt and Dianne E. Rennack and CRS In Focus IF10576, The Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act, by Dianne E. Rennack. In December 2016, the Obama Administration imposed additional sanctions on Russian individuals and entities in response to malicious cyber activity, including relating to the election process. For more information, see CRS Insight IN10635, Russia and the U.S. Presidential Election, by Catherine A. Theohary and Cory Welt. |

| 2. |

For example, see S. 94, Senator John McCain, "Statement by SASC Chairman John McCain on President Trump's Phone Call with Vladimir Putin," January 27, 2017. |

| 3. |

Ambassador Nikki Haley, "Remarks at a UN Security Council Briefing on Ukraine," U.S. Mission to the United Nations, February 2, 2017, at https://usun.state.gov/remarks/7668. |

| 4. |

White House, "Statement by the President on New Sanctions Related to Russia," Office of the Press Secretary, September 11, 2014. For more on the Executive Orders and legislation on Ukraine-related sanctions, see CRS In Focus IF10552, U.S. Sanctions on Russia Related to the Ukraine Conflict, coordinated by Cory Welt. |

| 5. |

No designations have been made to date under P.L. 113-95. The President issued a signing statement with P.L. 113-272, stating that he would not impose sanctions under the act but that it "gives the Administration additional authorities that could be utilized, if circumstances warranted." For more on the Executive Orders and legislation on Ukraine-related sanctions, and resulting designations, see CRS In Focus IF10552, U.S. Sanctions on Russia Related to the Ukraine Conflict, coordinated by Cory Welt. |

| 6. |

Steven Lee Myers, "Private Bank Fuels Fortunes of Putin's Inner Circle," New York Times, September 27, 2014; Carol Matlack, "Why the U.S. is Targeting the Business Empire of a Putin Ally," Bloomberg Businessweek, April 28, 2014. |

| 7. |

Sandrine Rastello and Helene Fouquet, "G-7 Nations Said to Oppose New World Bank Russia Projects," Bloomberg, August 1, 2014; EBRD, "EBRD Statement on Operation Approach in Russia," EBRD Press Release, July 23, 2014. |

| 8. |

For more on the G-20, see CRS Report R40977, The G-20 and International Economic Cooperation: Background and Implications for Congress, by Rebecca M. Nelson. |

| 9. |

For example, see Alexander Kolyandr, "Russia's Putin Slams Sanctions as Breach of WTO Rules," Wall Street Journal, September 18, 2014. |

| 10. |

For example, see Kathrin Hille and Shawn Donnan, "Russia Threatens US with WTO Action over Crimea Sanctions," Financial Times, April 16, 2014; "USTR Signals Russia Ag Ban Violates WTO Rules; Faults Procurement Policies," Inside U.S. Trade, January 8, 2015. |

| 11. |

Unless otherwise noted, macroeconomic data (for example, on growth, inflation, and debt levels) is from the IMF, World Economic Outlook, October 2014. |

| 12. |

"Geopolitical Risks Cloud Future of Russian Economy," IMF Survey, June 30, 2014. |

| 13. |

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Global Price of Brent Crude, Accessed February 2, 2017. |

| 14. |

For example, see IMF, "IMF Staff Concludes Visit to Russian Federation," November 29, 2016. |

| 15. |

International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, October 2016; Central Bank of Russia statistics, World Bank, Russia Economic Report 35, April 6, 2016. |

| 16. |

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Global Price of Brent Crude, Accessed February 2, 2017. |

| 17. |

International Monetary Fund, Russian Federation: Staff Report for the 2016 Article IV Consultation, July 2016; International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, October 2016. |

| 18. |

World Bank, Russia Economic Report 36, November 9, 2016. |

| 19. |

Bank for International Settlements, Consolidated Banking Statistics. Data is for consolidated international bank claims on an ultimate risk basis, accessed on February 2, 2017. Reporting countries include Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Chinese Taipei, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hong Kong, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Singapore, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States. It does not include several large emerging markets, like Brazil or China. |

| 20. |

Ilya Khrennikov, "Big Western Companies are Pumping Cash into Russia," Bloomberg, November 22, 2016. |

| 21. |

International Monetary Fund, Russian Federation: Staff Report for the 2016 Article IV Consultation, July 2016. |

| 22. |

Pavel Koshkin and Ksenia Zubacheva, "The World of the Economic Crisis in Russia Lies Ahead," Russia Direct, January 22, 2016. |

| 23. |

International Monetary Fund, Russian Federation: Staff Report for the 2015 Article IV Consultation, August 2015, pp. 5. |

| 24. |

Robin Emmott, "Sanctions Impact on Russia to be Longer Term, U.S. Says," Reuters, January 12, 2016. |

| 25. |

European Parliamentary Research Service, "Sanctions over Ukraine: Impact on Russia," March 2016. |

| 26. |

Evsey Gurvich and Ilya Prilepskiy, "The Impact of Financial Sanctions on the Russian Economy," Russian Journal of Economics, 2015, pp. 359-385. |

| 27. |

Nikolaus Blome, Kai Kiekmann, and Daniel Biskup, Interview with Putin, Bild, November 1, 2016. |

| 28. |

Max Seddon and Elaine Moore, "Russia Plans First Bond Issuance Since Sanctions," Financial Times, February 7, 2016. |

| 29. |

Daniel Ahn and Rodney Ludema, "Measuring Smartness: Understanding the Economic Impact of Targeted Sanctions," Office of the Chief Economist, U.S. Department of State, December 2016, Working Paper 2017-01. |

| 30. |

For example, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the National Association of Manufacturers ran ads in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post, warning about the potential implications of sanctions on Russia for the United States. See Mike Dorning, "Business at Odds with Obama Over Russia Sanctions Threat," Bloomberg News, June 24, 2014. In September 2014, USA*Engage, a coalition of manufacturing, agricultural, and services producers sponsored by the National Foreign Trade Council, cautioned that "U.S. sanctions are exacting substantial collateral damage to U.S. investments and operations in Russia across sectors." See "USA*Engage Opposes S. 2828, 'Ukraine Freedom Support Act of 2014,'" USA*Engage, September 18, 2014. |

| 31. |

The relative ranking of Russia's economy is based on one conventional measure: nominal gross domestic product (GDP) measured in current prices. Alternative measures of GDP, such as adjusted for differences in price levels across countries, may produce different orderings. |

| 32. |

In this report, trade data is from the U.S. Census Bureau, the Customs Committee of Russia, and Eurostat, as accessed from Global Trade Atlas, unless otherwise noted. U.S. investment data is from the U.S. Bureau of Economic analysis (on a historical-cost basis). |

| 33. |

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Data show U.S. direct investment position abroad on a historical-cost basis. |

| 34. |

The 2016 report by the U.S. Trade Representative on the implementation and enforcement of Russia's WTO commitments notes that broadly, Russia's actions continued to depart from the WTO's core tenets of liberal trade, transparency, and predictability in favor of inward-looking, import-substitution economic policies. U.S. Trade Representative, 2016 Report on the Implementation and Enforcement of Russia's WTO Commitments, December 2016. |

| 35. |

Andrew E. Kramer, "Exxon Reaches Arctic Oil Deal with Russians," New York Times, August 30, 2011; Rosneft, "Rosneft and ExxonMobil to Join Forces in the Artic and Black Sea Offshore, Enhance Co-operation through Technology Sharing and Joint International Projects," Press Release, August 30, 2011. |

| 36. |

Howard Schneider and Holly Yeager, "As Talk of Russia Sanctions Heats Up, Business Draws a Cautionary Line," Washington Post, March 7, 2014; "Visa, MasterCard Will Continue to Work in Russia," Wall Street Journal, May 20, 2014; Robert Wright, "Satellite Pinpoints US's Russian Space Dependence," Financial Times, May 16, 2014. |

| 37. |

Myles Udland, "Here's a List of Stocks with Lots of Exposure to Russia," Business Insider, July 17, 2014. |

| 38. |

U.S.-Russia Business Council. |

| 39. |

Clifford Krauss, "Exxon Halts Oil Drilling in Waters of Russia," New York Times, September 16, 2014. |

| 40. |

Irina Slav, "Russian Sanctions Have Cost Exxon over $1 Billion," Business Insider, October 17, 2016. |

| 41. |

Ryan Holeywell, "Russia Sanctions May Squeeze Oil Services Profits," Houston Chronicle, August 12, 2014. |

| 42. |

Adam Shell, "U.S. Companies Get Hurt by Sanctions Targeting Russia," USA Today, May 14, 2014. |

| 43. |

However, the restriction resulted in a run these types of rifles already in the United States (and thus not subject to the restriction), providing a short-term boost to U.S. gun dealers. Joshua Green, "Banned by U.S. Sanctions, AK-47s are Going, Going, Gone," Bloomberg Businessweek, September 4, 2014. |

| 44. |

Emma Ashford, "Not-So-Smart Sanctions: The Failure of Western Restrictions Against Russia," Foreign Affairs, January/February 2016. |

| 45. |

Natalia Kaurova and Anastasia Nesvetailova, "Making a Non-Western Payment Card System, in Russia," FT Alphaville, April 25, 2014. |

| 46. |

Elizabeth Dexheimer, "MasterCard CEO Sees Russia Having Small Impact on Profit," Bloomberg, May 1, 2014; Elizabeth Dexheimer, "Visa Profit Beats Estimates as Card Spending Climbs," Bloomberg, July 25, 2014. |

| 47. |

Aaron Smith and Abigail Brooks, "Kalashnikov Cranking up AK-47 Factory in Florida," CNN, January 27, 2016. |

| 48. |

"Too Smart by Half?: Effective Sanctions Have Always Been Hard to Craft," Economist, September 6, 2014. |

| 49. |

Global Trade Atlas. |

| 50. |

For example, see Lisa Murkowski, "Alaska Delegation: U.S. Should Push Back against Russian Seafood Boycott," press release, August 26, 2014. |

| 51. |

Ross Courtney, "Russia Sanctions Affect Washington Apples, Pears," Yakima Herald, August 8, 2014. |

| 52. |

U.S. Chicken Industry Statement on Russian Ban on U.S. Chicken Imports, August 6, 2014. |

| 53. |

"International Producers Risk Losing Russian Market over Sanctions," RT, November 13, 2014. |

| 54. |

Olga Razumovskaya, "An Isolated Russia Signs Business, Finance Pacts with China," Wall Street Journal, October 13, 2014. |

| 55. |

"Russia's Import Ban Means Big Business for Latin America," RT, August 7, 2014. |