Trade Promotion Authority (TPA): Frequently Asked Questions

Legislation to reauthorize Trade Promotion Authority (TPA)—sometimes called “fast track”—the Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015 (TPA-2015), was signed into law by former President Obama on June 29, 2015 (P.L. 114-26). If the President negotiates an international trade agreement that would reduce tariff or nontariff barriers to trade in ways that require changes in U.S. law, the United States can implement the agreement only through the enactment of legislation. If the trade agreement and the process of negotiating it meet certain requirements, TPA allows Congress to consider the required implementing bill under expedited procedures, pursuant to which the bill may come to the floor without action by the leadership, and can receive a guaranteed up-or-down vote with no amendments.

Under TPA, an implementing bill may be eligible for expedited consideration if (1) the trade agreement was negotiated during the limited time period for which TPA is in effect; (2) the agreement advances a series of U.S. trade negotiating objectives specified in the TPA statute; (3) the negotiations were conducted in compliance with an extensive array of notification and consultation with Congress and other stakeholders; and (4) the President submits to Congress a draft implementing bill, which must meet specific content requirements, and a range of required supporting information. If, in any given case, Congress judges that these requirements have not been met, TPA provides mechanisms through which the eligibility of the implementing bill for expedited consideration may be withdrawn in one or both chambers.

TPA is authorized through July 1, 2021. The United States has renegotiated the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), now known as the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) for which TPA could be used to consider implementing legislation. The issue of TPA reauthorization raises a number of questions regarding TPA, and this report addresses some of the most frequently asked questions, including the following:

What is trade promotion authority?

Is TPA necessary?

What are trade negotiating objectives and how are they reflected in TPA statutes?

What requirements does Congress impose on the President under TPA?

Does TPA affect congressional authority on trade policy?

For more information on TPA, see CRS Report RL33743, Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) and the Role of Congress in Trade Policy, by Ian F. Fergusson and CRS In Focus IF10038, Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), by Ian F. Fergusson.

Trade Promotion Authority (TPA): Frequently Asked Questions

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Background on Trade Promotion Authority (TPA)

- What is trade promotion authority?

- What is the current status of TPA?

- What was the legislative history of the current TPA?

- What is Congress's responsibility for trade under the Constitution?

- What authority does Congress grant to the President by enacting TPA legislation?

- Is TPA necessary?

- What requirements have been placed on the President under TPA?

- Is there a deadline for the President to submit a draft implementing bill to Congress?

- When was TPA/fast track first used?

- How many times has TPA/fast track been used?

- Do other countries have a TPA-type legislative mechanism?

- Can TPA procedures be used for consideration of the renegotiated North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)?

- Trade Negotiating Objectives

- What are U.S. trade negotiating objectives?

- Goods, Services, and Agriculture

- What are some of the negotiating objectives for market access for goods?

- Have U.S. negotiating objectives evolved on services trade?

- How did the negotiating objectives for agriculture differ from those in the 2002 TPA?

- Foreign Investment

- What are U.S. negotiating objectives on foreign investment?

- To what extent does TPA address investor-state dispute settlement?

- How have these provisions evolved over time?

- Will foreign investors be afforded "greater rights" than U.S. investors under U.S. trade agreements?

- Trade Remedies

- What are "trade remedies?"

- How does TPA address trade remedies?

- Currency Issues

- Have currency practices ever been addressed in a TPA authorization?

- How are currency issues addressed under TPA-2015?

- How have discussions on trade agreements that were considered after the expiration of TPA-2002 contributed to TPA-2015 objectives?

- Are the provisions of the May 10th Agreement incorporated into TPA-2015?

- Intellectual Property Rights (IPR)

- What are the key negotiating objectives concerning IPR?

- Does TPA-2015 contain new IPR negotiating objectives?

- Labor and Environment

- How do the negotiating objectives on labor under the 2002 TPA compare to those of TPA-2015?

- How do the environmental negotiating objectives under TPA-2015 compare to those of the 2002 TPA?

- Would the labor and environmental provisions negotiated be subject to the same dispute settlement provisions as other parts of the agreement?

- Regulatory Practices

- How does TPA-2015 seek to address regulatory practices?

- Does TPA-2015 address drug pricing and reimbursement issues?

- Dispute Settlement (DS)

- What are the principal negotiating objectives on DS in FTAs?

- How does TPA address DS at the WTO?

- New Issues Addressed in TPA-2015

- What new negotiating objectives are contained in TPA-2015?

- What new negotiating objectives were added as a result of Senate consideration?

- What changes were made as a result of House consideration?

- Congressional Consultation and Advisory Requirements

- How do the provisions on consultations in the TPA-2015 compare with previous statutes?

- What are the Congressional Advisory Groups on Negotiations (CAGS)?

- Who are Designated Congressional Advisors (DCAs)?

- Which Members of Congress have access to draft trade agreements and related trade negotiating documents?

- What are the requirements to consult with private sector stakeholders on trade policy?

- What are the requirements to consult with the public on trade policy?

- Do specific import sensitive industries have special negotiation and consultation requirements?

- Notification and Reporting Requirements

- Do congressional notification requirements change under TPA-2015?

- What is the role of the U.S. International Trade Commission?

- What are the various reporting requirements under TPA-2015?

- Expedited Procedures and the Congressional Role

- Do the expedited legislative procedures differ under the proposed TPA-2015?

- What is the purpose of the expedited procedures for considering implementing bills?

- Why do the expedited procedures for implementing bills prohibit amendments?

- What provisions are to be included in a trade agreement implementing bill to make it eligible for expedited consideration?

- Along with the draft implementing bill, what other documents must the President submit to Congress for approval?

- Must Congress consider covered trade agreements under the expedited legislative procedures?

- What is the effect of an "Extension Disapproval Resolution"?

- What is the effect of a "Procedural Disapproval Resolution"?

- What is a "mock markup," and how may Congress use it to assert control over a trade agreement implementing bill?

- What may Congress do if an implementing bill contains provisions inconsistent with negotiating objectives on trade remedies, and with what effect?

- How does TPA-2015 permit a single house to withdraw expedited consideration from a specific implementation bill?

- Does Congress have means of overriding the TPA procedures in addition to those provided by TPA statutes?

- Can Congress disapprove the President's launching trade negotiations with a trading partner?

- Does TPA constrain Congress's exercise of its constitutional authority on trade policy?

- National Sovereignty and Trade Agreements

- Can a trade agreement force the United States to change its laws?

- Would legislation implementing the terms of a trade agreement submitted under the TPA supersede existing law?

- What happens if a U.S. law violates a U.S. trade agreement?

Figures

Summary

Legislation to reauthorize Trade Promotion Authority (TPA)—sometimes called "fast track"—the Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015 (TPA-2015), was signed into law by former President Obama on June 29, 2015 (P.L. 114-26). If the President negotiates an international trade agreement that would reduce tariff or nontariff barriers to trade in ways that require changes in U.S. law, the United States can implement the agreement only through the enactment of legislation. If the trade agreement and the process of negotiating it meet certain requirements, TPA allows Congress to consider the required implementing bill under expedited procedures, pursuant to which the bill may come to the floor without action by the leadership, and can receive a guaranteed up-or-down vote with no amendments.

Under TPA, an implementing bill may be eligible for expedited consideration if (1) the trade agreement was negotiated during the limited time period for which TPA is in effect; (2) the agreement advances a series of U.S. trade negotiating objectives specified in the TPA statute; (3) the negotiations were conducted in compliance with an extensive array of notification and consultation with Congress and other stakeholders; and (4) the President submits to Congress a draft implementing bill, which must meet specific content requirements, and a range of required supporting information. If, in any given case, Congress judges that these requirements have not been met, TPA provides mechanisms through which the eligibility of the implementing bill for expedited consideration may be withdrawn in one or both chambers.

TPA is authorized through July 1, 2021. The United States has renegotiated the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), now known as the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) for which TPA could be used to consider implementing legislation. The issue of TPA reauthorization raises a number of questions regarding TPA, and this report addresses some of the most frequently asked questions, including the following:

- What is trade promotion authority?

- Is TPA necessary?

- What are trade negotiating objectives and how are they reflected in TPA statutes?

- What requirements does Congress impose on the President under TPA?

- Does TPA affect congressional authority on trade policy?

For more information on TPA, see CRS Report RL33743, Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) and the Role of Congress in Trade Policy, by Ian F. Fergusson and CRS In Focus IF10038, Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), by Ian F. Fergusson.

Background on Trade Promotion Authority (TPA)

What is trade promotion authority?

Trade promotion authority (TPA), sometimes called "fast track," refers to the process Congress has made available to the President for limited periods to enable legislation to approve and implement certain international trade agreements to be considered under expedited legislative procedures. Certain trade agreements negotiated by the President, such as agreements that reduce barriers to trade in ways that require changes in U.S. law, must be approved and implemented by Congress through legislation. If the content of the implementing bill and the process of negotiating and concluding it meet certain requirements, TPA ensures time-limited congressional consideration and an up-or-down vote with no amendments. In order to be eligible for this expedited consideration, a trade agreement must be negotiated during the limited time period for which TPA is in effect, and must advance a series of U.S. trade negotiating objectives specified in the TPA statute. In addition, the negotiations must be conducted in conjunction with an extensive array of required notifications to and consultations with Congress and other public and private sector stakeholders. Finally, the President must submit to Congress a draft implementing bill, which must meet specific content requirements, and a range of supporting information. If, in any given case, Congress judges that these requirements have not been met, TPA provides mechanisms through which the implementing bill may be made ineligible for expedited consideration. More generally, TPA defines how Congress has chosen to exercise its constitutional authority over a particular aspect of trade policy, while affording the President added leverage and credibility to negotiate trade agreements by giving trading partners assurance that final agreements can receive consideration by Congress in a timely manner and without amendments.1 TPA may apply both when the President is seeking a new agreement as well as when he is seeking changes to an existing agreement.2

What is the current status of TPA?

TPA can be used for legislation to implement trade agreements reached before July 1, 2021. Under TPA, it originally was effective until July 1, 2018, but it could be extended through July 1, 2021 provided the President asked for an extension—as he did on March 20, 2018—and Congress did not enact an extension disapproval resolution within 60 days of July 1, 2018. (See What is the effect of an "Extension Disapproval Resolution"?)

What was the legislative history of the current TPA?

The Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015 (TPA-2015) (H.R. 1890; S. 995) was introduced on April 16, 2015. Similar, though not identical, bills were ordered to be reported by the Senate Finance Committee on April 22, 2015, and by the House Ways and Means Committee the next day. The legislation, as reported by the Senate Finance Committee, was joined with legislation extending Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) into a substitute amendment to H.R. 1314 (an unrelated revenue measure), and that legislation was passed by the Senate on May 22 by a vote of 62-37.

In the House of Representatives, the measure was voted on under a procedure known as "division of the question," which requires separate votes on each component, but approval of both to pass. Voting on June 12, TPA (Title I) passed by a vote of 219-211, but TAA (Title II) was defeated 126-302. A motion to reconsider that vote was entered by then-Speaker Boehner shortly after that vote. On June 18, the House again voted on TPA, in an amendment identical to the Senate version attached to H.R. 2146, an unrelated House bill. This amendment did not include TAA. This legislation passed the House by a vote of 218-206 and by the Senate on June 24 by a vote of 60-38. It was signed by the President on June 29, 2015 (P.L. 114-26).

What is Congress's responsibility for trade under the Constitution?

The U.S. Constitution assigns express authority over the regulation of foreign trade to Congress. Article I, Section 8, gives Congress the power to "regulate Commerce with foreign Nations" and to "lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts, and Excises." In contrast, the Constitution assigns no specific responsibility for trade to the President. Under Article II, however, the President has exclusive authority to negotiate treaties (though his authority to enter into treaties is subject to the advice and consent of the Senate) and exercises broad authority over the conduct of the nation's foreign affairs.

What authority does Congress grant to the President by enacting TPA legislation?

In a sense, TPA grants no new authority to the President. The President possesses inherent authority to negotiate with other countries to arrive at trade agreements. However, some agreements require congressional approval in order to take effect. For example, if a trade agreement requires changes in U.S. law, it could be implemented only through legislation enacted by Congress. (In some cases, as well, Congress has enacted legislation authorizing the President in advance to implement certain kinds of agreements on his own authority. An example is the historical reciprocal tariff agreement authority described under the next question.) TPA legislation provides expedited legislative procedures (also known as "fast track" procedures) to facilitate congressional action on legislation to approve and implement trade agreements of the kinds specified in the TPA statute. TPA legislation also establishes trade negotiating objectives and notification and consultation requirements described later.

Is TPA necessary?

The President has the authority to negotiate international agreements, including free trade agreements (FTAs), but the Constitution gives Congress sole authority over the regulation of foreign commerce and tariffs. For 150 years, Congress exercised this authority over foreign trade by setting tariff rates directly. This policy changed with the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934, in which Congress delegated temporary authority to the President to enter into (sign) reciprocal trade agreements that reduced tariffs within preapproved levels and implement them by proclamation without further congressional action. This authority was renewed a number of times and has been included in successive versions of TPA.

In the 1960s, as international trade expanded, nontariff barriers, such as antidumping measures, safety and certification requirements, and government procurement practices, became subjects of trade negotiations and agreements. Congress altered the authority delegated to the President to require enactment of an implementing bill to approve the agreement and authorize changes in U.S. law required to meet obligations of these new kinds. For trade agreements that contained such provisions, preapproval was no longer an option. Because an implementing bill faced potential amendment by Members of Congress that could alter a long-negotiated agreement, Congress adopted fast track authority in the Trade Act of 1974 (P.L. 93-618) to ensure that the implementing bill could receive floor consideration and to provide a procedure under which it could not be amended. The act also established U.S. trade negotiating objectives and attempted to ensure executive branch notification of and consultation with Congress and the private sector. Fast track was renamed Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) in the Bipartisan Trade Promotion Authority Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-210).

Many observers point out that U.S. trade partners might be reluctant to negotiate with the United States, especially on politically sensitive issues, unless they are confident that the U.S. executive branch and Congress speak with one voice, that a trade agreement negotiated by the executive branch would receive timely legislative consideration, that it would not unravel by congressional amendments, and that the United States would implement the terms of the agreement reached. Others, however, have argued that because trade negotiations and agreements have become more complex and more comprehensive, bills to implement the agreements should be subject to amendment like other legislation. In practice, even though TPA is designed to ensure that Congress will act on implementing bills without amending them, it also affords Congress several procedural means to maintain its constitutional authority.3

What requirements have been placed on the President under TPA?

In general, under TPA, Congress has required the President to notify Congress and consult with Congress and with private sector stakeholders before, during, and upon completion of trade agreement negotiations, whether for a new agreement or changes to an existing agreement. TPA-2015 instituted additional requirements for consultation during implementation of agreements approved by Congress. Congress also has required the President to strive to adhere to general and specific principal trade negotiating objectives in any trade agreement negotiated under TPA. After signing the agreement, the President submits a draft implementing bill to Congress, along with the text of the trade agreement and a statement of administrative action required to implement it. (See sections below.)

Is there a deadline for the President to submit a draft implementing bill to Congress?

No. If the United States enters into (signs) a trade agreement within a period for which TPA is provided, the President may submit the implementing bill to Congress a day on which both the House and the Senate are in session, regardless of whether TPA expired before that date. In practice, the submission of the implementing bill usually has been coordinated with leadership of the House and Senate.

When was TPA/fast track first used?

Trade promotion authority was first enacted on January 1, 1975, under the Trade Act of 1974. It was used to enact the Tokyo Round Agreements Act of 1979 (P.L. 96-39), which implemented the 1974-1979 multilateral trade liberalization agreements reached under the Tokyo Round negotiations under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the predecessor to the World Trade Organization (WTO). Since that time it has been renewed four time times—1979, 1988, 2002, and 2015. In 1993, Congress provided a short-term extension to accommodate the completion of the GATT Uruguay Round negotiations.

How many times has TPA/fast track been used?

Since 1979, the authority has been used for 14 bilateral/regional free trade agreements (FTAs) and one additional set of multilateral trade liberalization agreements under the GATT (now the World Trade Organization [WTO])—the Uruguay Round Agreements Act of 1994.4 One FTA—the U.S.-Jordan FTA—was negotiated and approved by Congress without TPA. That FTA was largely considered noncontroversial and applies to only a small portion of U.S. total trade.

Do other countries have a TPA-type legislative mechanism?

In some countries, the executive may possess authority to conclude trade agreements without legislative approval. In others, especially in parliamentary systems, the head of government is typically able to secure approval of any requisite legislation without amendment under regular legislative procedures. In addition, some countries prohibit amendments to trade agreement legislation and others treat trade agreements as treaties that are self-executing.

Can TPA procedures be used for consideration of the renegotiated North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)?

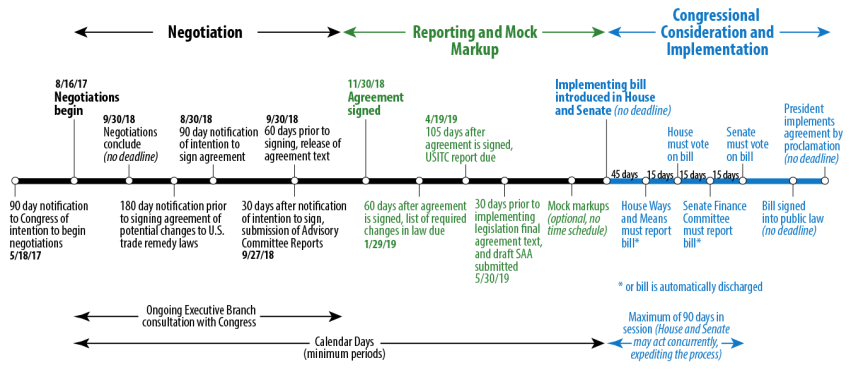

Yes. TPA applies both to negotiations of new agreements as well as changes to existing agreements.5 On May 18, 2017, pursuant to TPA, the President sent Congress a 90-day notification of his intent to begin talks with Canada and Mexico to renegotiate and modernize NAFTA, allowing the first round of negotiations to begin on August 16, 2017. The U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) submitted detailed negotiating objectives 30 days prior to the start of negotiations on July 17. USTR received public comments and held public hearings in June 2017.

After a year of negotiations, USTR Lighthizer announced a preliminary agreement with Mexico on August 27, 2018. On August 31, President Trump gave Congress the required notice 90-day notice that he would sign a revised deal with Mexico. After further negotiations, Canada joined the pact and it was concluded on September 30, 2018. The three nations signed what is now known as the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) on November 30, 2018. The Administration satisfied the requirement to provide Congress with a list of changes to U.S. law required to implement the agreement on January 29, 2019. However, the government shutdown delayed work on the International Trade Commission report on the economic effects of the agreement, and is now expected to be delivered to Congress by April 20, 2019.

Trade Negotiating Objectives

What are U.S. trade negotiating objectives?

Congress exercises its trade policy role, in part, by defining trade negotiating objectives in TPA legislation. The negotiating objectives are definitive statements of U.S. trade policy that Congress expects the Administration to honor, if the implementing legislation is to be considered under expedited rules. Since the original fast track authorization in the Trade Act of 1974, Congress has revised and expanded the negotiating objectives in succeeding TPA/fast track authorization statutes to reflect changing priorities and the evolving international trade environment. For example, since the last grant of TPA in 2002, new issues associated with state-owned enterprises, digital trade in goods and services, and localization policies have come to the forefront of U.S. trade policy and are included in TPA-2015 as principal negotiating objectives.

Under TPA-2015, Congress established trade negotiating objectives in three categories: (1) overall objectives; (2) principal objectives; and (3) capacity building and other priorities. These begin with broad goals that encapsulate the "overall" direction trade negotiations are expected to take, such as fostering U.S. and global economic growth and obtaining more favorable market access for U.S. products and services. Principal objectives are more specific and are considered the most politically critical set of objectives, the advancement of which is necessary for a U.S. trade agreement to receive expedited treatment under TPA. Capacity building objectives involve the provision of technical assistance to trading partners.

Goods, Services, and Agriculture

What are some of the negotiating objectives for market access for goods?

The market access negotiating objectives under TPA seek to reduce or to eliminate tariff and nontariff barriers and practices that decrease market access for U.S. products. One new provision in TPA-2015 considers the "utilization of global chains" in the goal of trade liberalization. It also calls for the use of sectoral tariff and nontariff barrier elimination agreements to achieve greater market access.6 Agriculture (see below) and textiles and apparel are addressed by separate negotiating objectives. For textiles and apparel, U.S. negotiators are to seek competitive export opportunities "substantially equivalent to the opportunities afforded foreign exports in the U.S. markets and to achieve fairer and more open conditions of trade" in the sector.7 Both the general market access provisions and the textile and apparel provisions in TPA-2015 are the same as those in the 2002 act.

Have U.S. negotiating objectives evolved on services trade?

Services have become an increasingly important element of the U.S. economy, and the sector plays a prominent role in U.S. trade policy.8 The rising importance of services is reflected in their treatment under TPA statutes as a principal negotiating objective beginning with the 1984 Trade Act.

Liberalization of trade in services was expressed in the 2002 Trade Act as a principal negotiating objective. It required that U.S. negotiators to make progress in reducing or eliminating barriers to trade in services, including regulations that deny nondiscriminatory treatment to U.S. services and inhibit the right of establishment (through foreign investment) to U.S. service providers. The content of the negotiating objective on services has not changed appreciably over the years. (Because foreign direct investment is an important mode of delivery of services, negotiating objectives on foreign investment [see below] pertain to services as well.)

TPA-2015 expands the principal negotiating objectives on services in the 2002 TPA by highlighting the role of services in global value chains and calling for the pursuit of liberalized trade in services through all means, including plurilateral trade agreements (presumably referring to the proposed Trade in Services Agreement [TISA]).9

How did the negotiating objectives for agriculture differ from those in the 2002 TPA?

TPA-2015 adds three new agriculture negotiating objectives to the 18 previously listed in the 2002 act.10 One lays out in greater detail what U.S. negotiators should achieve in negotiating robust trade rules on sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures (i.e., those dealing with a country's food safety and animal and plant health laws and regulations). This increased emphasis aims to address the concerns expressed by U.S. agricultural exporters that other countries use SPS measures as disguised nontariff barriers, which undercut the market access openings that the United States negotiates in trade agreements. The second calls for trade negotiators to ensure transparency in how tariff-rate quotas (TRQs)11 are administered that may impede market access opportunities. The third seeks to eliminate and prevent the improper use of a country's system to protect or recognize geographical indications (GI). These are trademark-like terms used to protect the quality and reputation of distinctive agricultural products, wines, and spirits produced in a particular region of a country. This new objective is intended to counter in large part the European Union's efforts to include GI protection in its bilateral trade agreements for the names of its products that U.S. and other country exporters argue are generic in nature or commonly used across borders, such as parma ham or parmesan cheese.

Foreign Investment

What are U.S. negotiating objectives on foreign investment?

The United States is the largest source and destination of foreign direct investment in the world. Both the 2002 act and TPA-2015 include identical principal negotiating objectives on foreign investment.12 The principal negotiating objectives on foreign investment are designed

to reduce or eliminate artificial or trade distorting barriers to foreign investment, while ensuring that foreign investors in the United States are not accorded greater substantive rights with respect to investment protections than domestic investors in the United States, and to secure for investors important rights comparable to those that are available under the United States legal principles and practices....13

TPA-2015 seeks to accomplish these goals by including provisions establishing protections for U.S. foreign investment, such as nondiscriminatory treatment, free transfer of investment-related capital flows, reducing or eliminating local performance requirements, and including established standards for compensation for expropriation consistent with U.S. legal principles and practices. These provisions are also part of the bilateral investments treaties (BIT) that the United States negotiates with other countries.

To what extent does TPA address investor-state dispute settlement?

Investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) allows for private foreign investors to seek international arbitration against host governments to settle claims over alleged violations of foreign investment provisions in FTAs. While TPA does not mention a specific ISDS mechanism, it states that trade agreements should

- provide meaningful procedures for resolving investment disputes;

- seek to improve mechanisms used to resolve disputes between an investor and a government through mechanisms to eliminate frivolous claims and to deter the filing of frivolous claims;

- provide procedures to ensure the efficient selection of arbitrators and the expeditious disposition of claims;

- provide procedures to enhance opportunities for public input into the formulation of government positions; and

- seek to provide for an appellate body or similar mechanism to provide coherence to interpretations of investment provisions in trade agreements.14

How have these provisions evolved over time?

Two negotiating objectives relating to foreign investment were initially listed under the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988 fast-track authority. The 2002 TPA and TPA-2015 list eight. In addition to TPA, U.S. investment negotiating objectives are shaped by the U.S. Model BIT, the template used to negotiate U.S. BITs and FTA investment chapters. The Model BIT has been revised periodically in an effort to balance investor protections and other policy interests. The 2004 Model BIT, for instance, narrowed the definitions of covered investment and minimum standard of treatment, and connected the definition of direct and indirect expropriation to "property rights or property interests," reflecting the U.S. Constitution's Takings Clause and with possible implications for expropriation protection depending on foreign countries' definitions of property. It also clarified that only in rare cases do nondiscriminatory regulatory actions by governments to protect legitimate public welfare objectives result in indirect expropriation. In response to global economic changes, the 2012 Model BIT, among other things, clarified that its obligations apply to state-owned enterprises, as well as to the types of financial services that may fall under a prudential exception (such as to address balance of payments problems). Other examples of revisions to the Model BIT over time include more detailed provisions on ISDS, stronger aspirational language on environmental and labor standards, and enhanced transparency obligations.

Will foreign investors be afforded "greater rights" than U.S. investors under U.S. trade agreements?

TPA-2015 states that no trade agreement is to lead to the granting of foreign investors in the United States greater substantive rights than are granted to U.S. investors in the United States. Some have argued, however, that the use of ISDS itself implies greater procedural rights.

Trade Remedies

What are "trade remedies?"

"Trade remedies" are statutory provisions that provide U.S. firms with the means to redress unfair trade practices by foreign actors, whether firms or governments. Examples are antidumping and countervailing duty laws.15 The "escape clause" or "safeguard provision" permits temporary restraints on import surges not considered to be unfairly traded that cause or threaten to cause serious injury, and thus may also be considered trade remedies.

How does TPA address trade remedies?

The principal trade negotiating objective concerning trade remedies in TPA-2015 and previous TPA legislation has been to "preserve the ability of the United States to rigorously enforce its trade laws" and to avoid concluding "agreements that weaken the effectiveness of domestic and international disciplines on unfair trade."16 Trade remedies have usually been addressed in the context of multilateral WTO negotiations, though some FTAs have included commitments related to trade remedies. Significantly, NAFTA includes—and the proposed USMCA maintains—a controversial mechanism ("Chapter 19" now Chapter 10.D) that enables other parties to challenge (and potentially overturn) trade remedy decisions using special tribunals. The objective reflects the perception by some Members of Congress that other countries have sought to weaken U.S. trade remedy laws. TPA-2015 also maintains past notification provisions that require the President to notify Congress about any proposals advanced in a negotiation that involve potential changes to U.S. trade remedy laws 180 days before signing (entering into) a trade agreement.

Currency Issues

Have currency practices ever been addressed in a TPA authorization?

The extent to which some countries may use the value of their currency to gain competitive market advantage is a source of concern for certain industries and some Members of Congress. In TPA-2002, the President was to seek to establish consultative mechanisms with trading partners to examine the trade consequences of significant and unanticipated currency movements and to scrutinize whether a foreign government has manipulated its currency to promote a competitive advantage in international trade. This provision was contained in the section on "Promotion of Certain Priorities."

How are currency issues addressed under TPA-2015?

TPA-2015 elevates the topic of currency manipulation to a principal U.S. negotiating objective. The legislation, as introduced, stipulates that U.S. trade agreement partners "avoid manipulating exchange rates in order to prevent effective balance of payments adjustment or to gain unfair competitive advantage."17 It does not specifically define currency manipulation to include or exclude central bank intervention in the domestic economy, and, hence, it does not differentiate among the ways a government can affect the value of its currency, such as currency market intervention or central bank activities to increase the money supply to stimulate the domestic economy. The language calls for multiple remedies, "as appropriate," including "cooperative mechanisms, enforceable rules, reporting, monitoring, transparency, or other means."

During floor consideration, the Senate considered and passed the so-called Hatch/Wyden amendment, which was adopted by the Senate by a vote of 70-29. This amendment sought to head off concerns that the language could be used to discourage central bank activities such as an increase in the money supply to stimulate the domestic economy, as well as to head off a currency amendment introduced by Senators Portman and Stabenow (defeated 48-51) that would have required the United States to negotiate "strong and enforceable rules against exchange rate manipulation," enforceable through the dispute settlement system of a potential agreement.

The Hatch/Wyden amendment modified the currency language of the bill as introduced, defining unfair currency practices as "protracted large scale intervention in one direction in the exchange market and a persistently undervalued foreign exchange rate to gain an unfair competitive advantage in trade." The amended objective seeks to "establish accountability" through potential remedies such as "enforceable rules, transparency, reporting, monitoring, cooperative mechanism, or other means to address exchange rate manipulation." The legislation contains the original negotiating objective, as well as the language of the Hatch/Wyden amendment.

How have discussions on trade agreements that were considered after the expiration of TPA-2002 contributed to TPA-2015 objectives?

On May 10, 2007, a bipartisan group of congressional leaders and the Bush Administration released a statement on agreed principles in five policy areas, which were subsequently reflected in four U.S. FTAs then being considered for ratification, with Colombia, Panama, Peru, and South Korea. The policy areas covered included worker rights, environment protection, intellectual property rights, government procurement, and foreign investment. This agreement has since been referred to as the "May 10th Agreement" (for details, see box on "The May 10th Agreement," below). The extent to which these principles would be incorporated in negotiating objectives in any renewal of TPA authority, and reflected in future FTAs, was a source of debate among policymakers.

|

The "May 10th Agreement" The agreement of May 10th, 2007, was a bipartisan statement of agreed principles between the President and the House leadership on labor, environment, IPR, government procurement, and foreign investment, to be applied to the four FTAs Congress would consider at that time: Colombia, Panama, Peru, and South Korea. Regarding worker rights, the May 10th Agreement (the Agreement) required the United States and FTA partners to commit to enforcing the five international labor principles enshrined in International Labor Organization's (ILO's) 1998 Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights At Work and that the commitment be enforceable under the FTA. These rights are the freedom of association, the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining, the elimination of all forms of compulsory or forced labor, the effective abolition of child labor, including the worst forms of child labor, and the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation. The Agreement also required FTAs to adhere to seven major multilateral environmental agreements: the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species; the Montreal Protocol on Ozone Depleting Substances; the Convention on Marine Pollution; the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Convention; the Ramsar Convention on the Wetlands; the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling; and the Convention on Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources. Furthermore, the parties were not to waive or otherwise derogate from their labor or environmental protection laws in a manner that would affect trade or investment with the FTA partner(s). In addition, the labor and environment provisions were to be enforceable, if consultation and other avenues fail, through the same dispute settlement procedures that apply to the other provisions in the FTA. The Agreement also required the FTAs to include provisions related to patents and approval of pharmaceuticals for marketing exclusivity with different requirements for developed and developing countries. Specifically, the Agreement requires provisions dealing with the effective period of data exclusivity (restrictions on the use of test data produced for market approval by generic drug producers); patent extensions; linkage of marketing approval of generic drugs to determination of possible patent infringement; and reaffirmation of adherence to the Doha Declaration on compulsory licensing of drugs to respond to public health crises. Regarding foreign investment, the Agreement required each of the FTAs to state that none of its provisions would accord foreign investors greater substantive rights in terms of foreign investment protection than are accorded U.S. investors in the United States. The Agreement also clarified that FTA parties may require compliance with core labor standards in government procurement contracts and may insert provisions to promote environmental protections. |

Are the provisions of the May 10th Agreement incorporated into TPA-2015?

TPA-2015 incorporates the labor and environmental principles of the May 10th agreement, including requirements that a negotiating party's labor and environmental statutes adhere to internationally recognized core labor standards and to obligations under common multilateral environmental agreements. TPA-2015 also includes the language of the May 10th agreement on investment, "ensuring that foreign investors in the United States are not granted greater substantive rights with respect to investment protections than U.S. investors in the United States."

TPA-2015 does not specifically refer to the language of the May 10th agreement on patent protection for pharmaceuticals, which were designed to achieve greater access to medicine in developing country FTA partners. Instead, TPA-2015 language seeks to "ensure that trade agreements foster innovation and access to medicine."

Intellectual Property Rights (IPR)

What are the key negotiating objectives concerning IPR?

The United States has long supported the strengthening of intellectual property rights through trade agreements, and Congress has placed IPR protection as a principal negotiating objective since the 1988 grant of fast-track authority.18 The overall objectives on IPR under the 2002 TPA authority were the promotion of adequate and effective protection of IPR; market access for U.S. persons relying on IPR; and respect for the WTO Declaration on the Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement and Public Health. This last objective addressed concerns for the effect of patent protection for pharmaceuticals on innovation and access to medicine, especially in developing countries.

These objectives are largely reflected in the five objectives in TPA-2015.19 The promotion of adequate and effective protection of IPR through the negotiation of trade agreements that reflect a standard of protection similar to that found in U.S. law is a key provision. Other provisions include strong protection of new technologies; standards of protection that keep pace with technological developments; nondiscrimination in the treatment of IPR; and strong enforcement of IPR. TPA-2015 also seeks to ensure that agreements negotiated foster innovation and access to medicine.

Does TPA-2015 contain new IPR negotiating objectives?

A new objective in TPA-2015 seeks to negotiate the prevention and elimination of government involvement in violations of IPR such as cybertheft or piracy.20 The enhanced protection of trade secrets and proprietary information collected by governments in the furtherance of regulations is contained in the negotiating objective on regulatory coherence.

Labor and Environment

How do the negotiating objectives on labor under the 2002 TPA compare to those of TPA-2015?

Both the 2002 TPA and TPA-2015 include several negotiating objectives on labor issues and worker rights.21 While similar, they also differ in some fundamental ways. For example, the 2002 authority states that trade agreements are to ensure that a trading partner does not fail effectively to enforce its own labor statutes. The TPA-2015 requires that the United States ensure not only that a trading partner enforces its own labor statutes but also that those statutes include internationally recognized core labor standards as defined in the bill to mean the "core labor standards as stated in the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights to Work and its Follow-Up (1998)."22 It also states that parties shall not waive or derogate statutes or regulations implementing internationally recognized core labor standards in a manner affecting trade or investment between the United States and the parties to an agreement.23

In addition, the 2002 TPA allowed some discretion on the part of a trading partner government in enforcing its laws and stated that the government would be considered fulfilling its obligations if it exercised discretion, either through action or inaction, reasonably. TPA-2015, on the other hand, states that while the government retains discretion in implementing its labor statutes, the exercise of that discretion is not a reason not to comply with its obligations under the trade agreement.24 The labor—and environmental—provisions also contain language to strengthen the capacity of trading partners to adhere to labor and environmental standards, as well as a provision to reduce or eliminate policies that unduly threaten sustainable development.

How do the environmental negotiating objectives under TPA-2015 compare to those of the 2002 TPA?

Like the labor negotiating objectives, TPA-2015 provides not only that a party enforce its own environmental standards as in the 2002 act, but also that those laws be consistent with seven internationally recognized multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) and other provisions.25 It also contains the abovementioned prohibition of waiver or derogation from environmental law in matters of trade and investment. The environmental objective contains language allowing a reasonable exercise of prosecutorial discretion in enforcement and allocation of resources: language similar to, but seemingly more flexible than, that included in the labor provisions.26

Would the labor and environmental provisions negotiated be subject to the same dispute settlement provisions as other parts of the agreement?

TPA-2015 commits negotiators "to ensure that enforceable labor and environmental standards are subject to the same dispute settlement and remedies as other enforceable provisions under the agreement."27 Under the most recent U.S. trade agreements, this could mean the withdrawal of trade concessions until a dispute is resolved. By contrast, the 2002 TPA did not prescribe particular remedies—only suggesting that remedies should be "equivalent"—and trade agreements implemented using 2002 TPA provided separate remedies under dispute settlement, including the use of monetary penalties and technical assistance.

Regulatory Practices

How does TPA-2015 seek to address regulatory practices?

The regulatory practices negotiation objective seeks to reduce or eliminate the use of governmental regulations (nontariff barriers)—such as discriminatory certification requirements or nontransparent health and safety standards—from impeding market access for U.S. goods, services, or investment.28 Like the 2002 TPA, it attempts to obtain commitments in trade agreements that proposed regulations are based on scientific principles, cost-benefit risk assessment, or other objective, nondiscriminatory standards. It also seeks more transparency and participation by affected parties in the development of regulations, consultative mechanisms to increase regulatory coherence, regulatory compatibility through harmonization or mutual recognition, and convergence in the standards-development process. A new provision in TPA-2015 seeks to limit governmental collection of undisclosed proprietary data—"except to satisfy a legitimate and justifiable regulatory interest"—and to protect those data against public disclosure.29

Does TPA-2015 address drug pricing and reimbursement issues?

Yes, the regulatory practices negotiating objective contains language applicable to a foreign country's drug pricing system. TPA-2015 seeks to eliminate government price controls and reference prices "which deny full market access for United States products." TPA-2015 also seeks to ensure that regulatory regimes adhere to principles of transparency, procedural fairness, and nondiscrimination.30

Dispute Settlement (DS)

What are the principal negotiating objectives on DS in FTAs?

TPA legislation has sought to establish DS mechanisms to resolve disputes first through consultation, then by the withdrawal of benefits to encourage compliance with trade agreement commitments. TPA-2015 provisions aim to apply the principal DS negotiating objectives equally through equivalent access, procedures, and remedies. In addition, as noted above, TPA requires that labor and environmental disputes be subject to the same procedures and remedies as other disputes—an obligation that, in practice, allows for full dispute settlement of labor and environmental disputes under the agreement.31

How does TPA address DS at the WTO?

TPA-2015, like its predecessors, also seeks to ensure that WTO DS panels and its appeals venue, the Appellate Body, "apply the WTO Agreement as written, without adding to or diminishing rights and obligations under the agreement," and use a standard of review applicable to the Uruguay Round Agreement in question, "including greater deference, where appropriate, to the fact finding and technical expertise of national investigating authorities."32 These provisions address the perception by some Members of Congress that the WTO dispute settlement bodies have interpreted WTO agreements in ways not foreseen or reflected in the agreement.

New Issues Addressed in TPA-2015

What new negotiating objectives are contained in TPA-2015?

Digital Trade in Goods and Services and Cross-Border Data Flows

The internet not only has become a facilitator of international trade in goods and services given its borderless nature, but also is itself a source of trade in digital services, such as search engines or data storage. At the same time, however, digital trade and cross-border data flows increasingly have become the target of trade restricting measures, especially in emerging markets. The digital trade provisions update and expand upon the e-commerce provisions from the 2002 TPA that call for trade in digital goods and services to be treated no less favorably than corresponding physical goods or services in terms of applicability of trade agreements, the classification of a good or service, or regulation. Aside from ensuring that governments refrain from enacting measures impeding digital trade in goods and services, TPA-2015 extends that commitment to cross-border data flows, data processing, and data storage. It also calls for enhanced protection of trade secrets and proprietary information collected by governments in the furtherance of regulations. The promotion of strong IPR for technologies to facilitate digital trade is included in the IPR objectives, which extends the existing WTO moratorium on duties on electronic commerce transactions.33

State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs)

U.S. firms often face competition from state-owned or state-influenced firms. The TPA-2015 principal negotiating objective for SOEs seeks to ensure that SOEs are not favored with discriminatory purchases or subsidies and that competition is based on commercial considerations in order that U.S. firms may compete on a "level playing field."34

Localization

TPA-2015 adds a principal negotiating objective on "localization," the practice by which firms are required to locate facilities, intellectual property, services, or assets in a country as a condition of doing business. While localization can be motivated by privacy and security interests, there are concerns that such measures can be trade distorting and may be used for protectionist purposes. TPA-2015 directs U.S. negotiators to prevent and eliminate such practices, as well as the practice of indigenous innovation, where a country seeks to develop local technology by the enforced use of domestic standards or local content.35 The digital trade objectives described above also include localization provisions concerning the free flow of data.36 Localization barriers are also addressed in the foreign investment chapter with provisions to restrict or eliminate performance requirements or forced technology transfers in the establishment or operation of U.S. investments abroad.37

Human Rights

TPA-2015 contains a negotiating objective to ensure the implementation of trade commitments through promotion of good governance, transparency, and the rule of law with U.S. trade partners, "which are important parts of the broader effort to create more open democratic societies and to promote respect for internationally recognized human rights."38 During floor consideration, the Senate adopted unopposed an amendment by Senator Lankford to add an overall negotiating objective to "take into account conditions relating to religious freedom of any party to negotiations for a trade agreement with the United States."39

What new negotiating objectives were added as a result of Senate consideration?

The Senate Finance Committee adopted three amendments to TPA-2015 that were incorporated into the legislation ultimately passed by Congress. These amendments

- Made the negotiating objective on human rights (see above) a principal negotiating objective. As with the other principal negotiating objectives, expedited procedures can be conditioned on progress toward achieving these objectives.

- Discouraged potential trading partners from adopting policies to limit trade or investment relations with Israel. This amendment was specific to the then-proposed Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership.40

- Prohibited expedited consideration of trade agreements with countries ranked in the most problematic category of countries for human trafficking concerns (Tier III) in the annual report by the Department of State on Trafficking in Persons.41

What changes were made as a result of House consideration?

The House placed its amendments to TPA-2015 in the subsequently passed Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-125).42 These five amendments added the following:

- An overall negotiating objective "to ensure that trade agreements do not require changes to the immigration laws or obligate the United States to grant access or expand access to visas issued under.... the Immigration and Nationality Act."

- An overall negotiating objective "to ensure that trade agreements do not require changes to U.S. law or obligate the United States with respect to global warming or climate change, other than those fulfilling the other negotiating objectives" in TPA.

- A principal negotiating objective to expand market access, reduce tariff and nontariff barriers, and eliminate subsidies that distort trade in fish, shellfish, and seafood products.

- An amendment to the Section 4(c) consultation provisions to allow for additional accreditation for staffers of the chair and ranking member of the committees of jurisdiction to serve as delegates to negotiations.

- An amendment to the human trafficking provision (above), which would allow the President to submit a waiver if the country has taken concrete steps to implement the principal recommendations of the United States to combat trafficking.

Congressional Consultation and Advisory Requirements

The consultative, notification, and reporting requirements of TPA are designed to achieve greater transparency in trade negotiations and to maintain the role of Congress in shaping trade policy. Congress has required the executive branch to consult with Congress prior to and during trade negotiations, as well as upon their completion and the signing of (entering into) a trade agreement. TPA/fast track statutes have required the USTR to meet and consult with the House Ways and Means Committee, the Senate Finance Committee, and other committees that have jurisdiction over laws possibly affected by trade negotiations.

How do the provisions on consultations in the TPA-2015 compare with previous statutes?

While many of the provisions on consultation have some precedent in past grants of TPA in terms of advisory structure and transparency commitments, TPA-2015 contains some new provisions. These provisions require the following:

- The appointment of a Chief Transparency Officer at USTR. This official is required "to consult with Congress on transparency policy, coordinate transparency in trade negotiations, engage and assist the public, and advise the U.S. Trade Representative on transparency policy."43

- That USTR make available, prior to initiating FTA negotiations with a new country, "a detailed and comprehensive summary of the specific objectives with respect to the negotiations, and a description of how the agreement, if successfully concluded, will further those objectives and benefit the United States," and periodically update the summary during negotiations.44

- That the President publicly release the assessment by the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) of the potential impact of the trade agreement (see below), which had not been the case under the previous authority.45

- That USTR consult with committees of jurisdiction after accepting a petition for review or taking enforcement actions in regard to potential violation of a trade agreement.46

- The release of the negotiating text to the public 60 days prior to the agreement's being signed by the Administration. In addition, the final text of the implementing legislation and a draft Statement of Administrative Action must be submitted to Congress 30 days prior to its introduction.47

What are the Congressional Advisory Groups on Negotiations (CAGS)?

TPA-2015 includes consultation requirements similar to those under the 2002 TPA and previous trade negotiating authorities. TPA-2015 provides for the establishment of separate Congressional Advisory Groups on Negotiations (CAGs) for each house—a House Advisory Group on Negotiations (HAGON), chaired by the chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, and a Senate Advisory Group on Negotiations (SAGON), chaired by the chairman of the Finance Committee. In addition to the chairmen, each CAG includes the ranking member and three additional members of the respective committee, no more than two of whom could be from the same political party. Each CAG also includes the chair and ranking member, or their designees, of committees of the respective chamber with jurisdiction over laws that could possibly be affected by the trade agreements.48 The CAGs replaces the Congressional Oversight Group (COG), a bicameral group with similar membership created under the 2002 TPA that reportedly met infrequently.

For the CAGs, USTR is required to develop guidelines "to facilitate the useful and timely exchange of information between them and the Trade Representative." These guidelines include fixed-timetable briefings and access by members of the CAG and their cleared staffers to pertinent negotiating documents. The President also is required to meet with either group upon the request of the majority of that group prior to launching negotiations or at any time during the negotiations. TPA-2015 mandates that the USTR draw up several sets of guidelines to enhance consultations with Congress, the private sector Advisory Committee for Trade Policy and Negotiations (see below), sectoral and industry advisory groups, and the public at large. USTR was directed to produce the guidelines, in consultation with the chairmen and ranking members of the Senate Finance Committee and the House Ways and Means Committee, no later than 120 days after TPA-2015 was enacted.49 The guidelines are to provide for timely briefings on the negotiating objectives for any specific trade agreement, the status of the negotiations, and any changes in laws that might be required to implement the trade agreement. In addition, TPA-2015 requires the USTR to consult on trade negotiations with any Member of Congress who requests to do so.

Who are Designated Congressional Advisors (DCAs)?

Designated Congressional Advisors (DCAs) are Members of Congress who are accredited as official advisers to U.S. delegations to trade negotiations. Under Section 161 of the Trade Act of 1974, as amended, the Speaker of the House selects five Members from the Ways and Means Committee (no more than three of whom are to be of the same political party), and the President Pro Tempore of the Senate selects five Members from the Senate Finance Committee (no more than three of whom can be of the same political party), as DCAs.50 In addition, the Speaker and the Senate President Pro Tempore may each designate as DCAs members of committees that would have jurisdiction over matters that are the subject of trade policy considerations or trade negotiations. Members of the CAG who are not already DCAs may also become DCA members.

Under TPA-2015, in addition to the above, any Member of the House may be designated by the Speaker as a DCA upon consultation with the chairman and ranking member of the House Ways and Means Committee and the chairman and ranking member of the committee from which the Member is selected. Similarly, any Member of the Senate may be designated a DCA upon consultation with the President Pro Tempore and the chairman and ranking member of the committee from which the Senator is selected. In addition, USTR is to accredit members of the HAGON and SAGON as official trade advisers to U.S. trade negotiation delegations by the USTR.51

Which Members of Congress have access to draft trade agreements and related trade negotiating documents?

Under the authority of Executive Order 13526, the USTR gives classified status to draft texts of trade agreements. According to USTR, nevertheless, any Member may examine draft trade agreements and related trade negotiating documents, although the 2002 TPA did not explicitly provide for this practice. TPA-2015 expressly requires that the USTR provide Members and their appropriate staff, as well as appropriate committee staff, access to pertinent documents relating to trade negotiations, including classified materials.52

What are the requirements to consult with private sector stakeholders on trade policy?

In order to ensure that private and public stakeholders have a voice in the formation of U.S. trade policy, Congress established a three-tier advisory committee system under Section 135 of the Trade Act of 1974, as amended. These committees advise the President on negotiations, agreements, and other matters of trade policy. At the top of the system is the 30-member Advisory Committee for Trade Policy and Negotiations (ACTPN) consisting of presidentially appointed representatives from local and state governments and representatives from the broad range of U.S. industries and labor groups. At the second tier are policy advisory committees—Trade and Environment Policy, Intergovernmental Policy, Labor Policy, Agriculture Policy, and Africa.53 The third tier consists of 17 sector-specific committees—one agricultural and 16 industrial sectors—which provide technical advice. In addition to consultations with the advisory committees, the USTR solicits the views of stakeholders through Federal Register notices and hearings. The legislation requires the USTR to develop guidelines on consultations with the private sector advisory committees also no later than 120 days after the legislation's entry into effect.54

The TPA/fast track authorities under the Trade Act of 1974, and under authorities thereafter, have required the President to submit reports from the various advisory committees on their views regarding the potential impact of an agreement negotiated under the TPA before the agreement is submitted for congressional approval. For example, the 2002 TPA requires the President to submit to Congress the reports of the advisory committees on a trade agreement no later than 30 calendar days after notifying Congress of his intent to enter into (sign) the trade agreement. Those reports are also required under TPA-2015.55

What are the requirements to consult with the public on trade policy?

TPA-2015 expands the existing statutory requirement for consultation with the public.56 For example, it requires the USTR to develop guidelines for enhanced consultation with the public and to provide these guidelines no later than 120 calendar days after the legislation's entry into effect.57 The guidelines committed USTR to provide detailed information regarding trade policy online, as well as to provide public stakeholder events for interested parties to meet with and share their views with negotiators, typically during negotiating rounds. The President also is required to make public other mandated reports on the impact of future trade agreements on the environment, employment, and labor rights in the United States (see below). These guidelines did not provide for the public release of negotiating positions or texts during the course of the negotiations.

Do specific import sensitive industries have special negotiation and consultation requirements?

Under the 2002 Trade Act and TPA-2015, import sensitive products58 in the agriculture, fishing, and textile sectors have special assessment and consultation requirements before initiating negotiations.

Notification and Reporting Requirements

Another tool Congress has employed under TPA to ensure transparency of the negotiating process is to require the President to notify Congress prior to launching trade negotiations and prior to entering into (signing) a trade agreement.

Do congressional notification requirements change under TPA-2015?

TPA 2015 maintains TPA-2002 requirements that the President

- notify Congress 90 calendar days prior to initiating negotiations on a reciprocal trade agreement with a foreign country;

- notify Congress 90 calendar days prior to entering into (signing) a trade agreement;

- notify Congress 60 days prior to entering into the agreement of any expected changes in U.S. law that would be required in order to be in compliance with the trade agreement;

- notify the House Ways and Means Committee and the Senate Finance Committee of any changes in U.S. trade remedy laws (discussed earlier) that would be required by the trade agreement 180 calendar days prior to entering into a trade agreement; and

- comply with special notification and reporting requirements for agriculture, fishing industry, and textiles and apparel.

What is the role of the U.S. International Trade Commission?

The U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) is an independent, quasijudicial federal agency with broad investigative responsibilities on matters related to international trade. One of its analytic functions is to examine and assess international trade agreements. Under TPA-2015, the President must submit the details of the proposed agreement to the ITC 90 calendar days prior to entering into (signing) the agreement. The ITC is required to produce an assessment of the potential economic impact of the agreement no later than 105 calendar days after the agreement is signed. Unlike TPA-2002, TPA-2015 requires that the reports be made public.59

What are the various reporting requirements under TPA-2015?

Several reporting requirements were established in past TPA legislation; TPA-2015 maintains similar requirements and establishes new ones. These include the following:

- Extension disapproval resolution (see below).60 TPA was extended to July 1, 2021 in 2018. The President was required to produce the following reports in support of that extension:

- The President must report to Congress on the status and progress of current negotiations, and why the extension is necessary to complete negotiations.

- The Advisory Committee on Trade Policy and Negotiations must report on the progress made in the negotiations and a statement of its views on whether the extension should be granted.

- The International Trade Commission (ITC) must report on the economic impact of all trade agreements negotiated during the current period TPA is in force.

- Report on U.S. trade remedy laws. The President must report on any proposals that could change U.S. trade remedy laws to the committees of jurisdiction (House Ways and Means Committee and the Senate Finance Committee). Must be submitted 180 days before an agreement is signed.61

- Upon entering into an agreement, the following reports must be completed:

- Advisory Committee Reports. The Advisory Committee for Trade Policy and Negotiations and appropriate policy, sectoral, and functional committees must report on whether and to what extent the agreement would promote the economic interests of the United States, and the overall and principal negotiating objectives of TPA. It must be submitted 30 days after the President notifies Congress of his intention to sign an agreement.62

- ITC Assessment. The ITC must report on the likely impact of the agreement on the economy as a whole and on specific economic sectors. The President must provide information to the ITC on the agreement as it exists no later than 90 days before an agreement is signed (entered into) to inform the assessment. The ITC must report to Congress within 105 days after the agreement is signed. This report is to be made public under TPA-2015.63

- Reports to be submitted by the President to committees of jurisdiction in relation to each trade agreement64

- Environmental review of the agreement and the content and operation of consultative mechanisms established pursuant to TPA.

- Employment Impact Reviews and Report. Reviews the impact of future trade agreement on U.S. employment and labor markets.

- Labor Rights. A "meaningful" labor rights report on the country or countries in the negotiations and a description of any provisions that would require changes to the labor laws and practices of the United States.

- Implementation and Enforcement. A plan for the implementation and enforcement of the agreement, including border personnel requirements, agency staffing requirements, customs infrastructure requirements, impact on state and local governments, and cost analyses.

- Report on Penalties. A report one year after the imposition of a penalty or remedy under the trade agreement on the effectiveness of the penalty or remedy applied in enforcing U.S. law, whether the penalty or remedy was effective in changing the behavior of the party, and whether it had any adverse impact on other parties or interests.65

- Report on TPA. The ITC is to submit a report on the economic impact of all trade agreements implemented under TPA procedures since 1984 one year after enactment and, again, no later than five years thereafter.66

Expedited Procedures and the Congressional Role

Do the expedited legislative procedures differ under the proposed TPA-2015?

TPA-2015 incorporates existing expedited procedures ("trade authorities procedures") prescribed in Section 151 of the Trade Act of 1974 for consideration of trade agreement implementing bills (see the text box).

|

Trade Authorities Procedures Under Section 151 of the Trade Act of 1974 (19 U.S.C. 2191), an implementing bill submitted by the President is automatically introduced in both chambers and referred to the appropriate committees of jurisdiction (normally Ways and Means in the House and Finance in the Senate, perhaps along with others). In each chamber, the committees have 45 session days to report the bill back to the floor, and they may not amend it or recommend amendments. If either committee does not report after 45 session days, it is discharged from considering the implementing bill, which makes the bill available for floor action (days on which the respective chamber does not meet are not counted toward the 45-day period). In each chamber, once the committee reports or is discharged, the implementing bill may be called up for consideration by a nondebatable motion, offered from the floor by any Member. In the House, this provision means that no special rule from the Committee on Rules is necessary in order to bring the bill to the floor; in the Senate, it means that Senators need not defer to the majority leader to call up the bill, and no super-majority vote is needed to limit debate on a motion to consider the legislation. In each chamber, once the measure is under consideration, debate is limited to 20 hours, no amendments may be considered, and various potentially dilatory motions are prohibited. In the Senate, this limit on debate means that no super-majority vote will be needed to overcome a filibuster. Each chamber can pass the implementing bill by a majority of the Members voting. If either chamber passes its bill, it sends the bill to the other; the receiving chamber then considers its own implementing bill under the expedited procedure, but takes its final vote on the bill received from the first. Because neither chamber can amend the implementing bill, the two bills must remain identical; as a result, if the chamber acting second passes the bill received from the other, this action clears the bill for the President's signature. Most trade agreements affect tariffs, in which case the implementing bill will be a revenue bill, which, under the Constitution, must be enacted as a House bill. In this case, the House usually acts first, and sends its bill to the Senate, where it is referred to committee. The Senate committee is automatically discharged from considering the House bill if it does not report it within 15 session days, or by the end of the 45 session days allowed for considering its own bill, whichever is later. After the committee reports the House bill or is discharged, the Senate then may consider that measure under the expedited procedure. However, the Senate can vote on its "S." numbered bill first, although it must ultimately pass the legislation received from the House and it is the House bill that will be presented to the President. This has been done for three FTAs in the past, usually for scheduling or political reasons. |

What is the purpose of the expedited procedures for considering implementing bills?

The expedited TPA procedures include three core elements: a mechanism to ensure timely floor consideration, limits on debate, and a prohibition on amendment. The guarantee of floor consideration is intended to ensure that Congress will have an opportunity to consider and vote on the implementing bill whether or not the committees of jurisdiction or the leadership favor the legislation. Especially in the Senate, the limitation on debate helps ensure that opponents cannot prevent a final vote on an implementation bill by filibustering. The prohibition on amendments is intended to ensure that Congress will vote on the implementing bill in the form in which it is presented to Congress.

In these ways, the expedited procedures help assure that Congress will act on an implementing bill, and that if the bill is enacted, its terms will implement the trade agreement that was negotiated. This arrangement helps to increase the confidence of U.S. negotiating partners that law enacted by the United States will implement the terms of the agreement, so that they will not be compelled to renegotiate it or give up on it.

Why do the expedited procedures for implementing bills prohibit amendments?

As noted above, if Congress were to amend an implementing bill, the legislation ultimately enacted might fail to implement the terms of the agreement that had been agreed to. In addition, if either house were to amend the implementing bill, it would likely become necessary to resolve the differences between the House and Senate versions through a conference committee (or through amendments between the houses). Since there is no way to compel the House and Senate to reach an agreement on a single version of the legislation, this prospect would make it impossible to ensure that Congress could complete action on the implementing bill expeditiously or, possibly, at all.

What provisions are to be included in a trade agreement implementing bill to make it eligible for expedited consideration?

Because trade agreement implementing bills are eligible for expedited congressional consideration under TPA, Congress has imposed restrictions on what may be included in these bills. The 2002 TPA legislation required that the implementing bill consist only of provisions that approve the trade agreement and a statement of administrative action proposed to implement it, together with provisions "necessary or appropriate" to implement the agreement, "repealing or amending existing laws or providing new statutory authority."