U.S. Trade in Services: Trends and Policy Issues

Trade in “services” refers to a wide and growing range of economic activities. These activities include transport, tourism, financial services, use of intellectual property, telecommunications and information services, government services, maintenance, and other professional services from accounting to legal services. Compared to goods, the types and volume of services that can be traded are limited by factors such as the requirement for direct buyer-provider contact, and other unique characteristics such as the reusability of services (e.g., professional consulting) for which traditional value measures do not account. In addition to services as independent exports, manufactured and agricultural products incorporate and depend on services, such as research and development or shipping of intermediate or final goods. As services account for 71% of U.S. employment, U.S. trade in services, both services as exports and as inputs to other exported products, can have a broad impact across the U.S. economy.

Rapid advances in information technology and the related growth of global value chains have expanded both the level and the range of services tradable across national borders. As a result, services have become a priority in U.S. trade policy, and a significant part of U.S. trade flows and of global trade in general, accounting for $827 billion in U.S. exports in 2018. As the United States is the world’s largest exporter and importer of services (14% and 10% of the global total in 2018), the Administration’s discussions on potential and existing trade agreements that include services are significant.

A number of economists argue that “behind the border” barriers imposed by foreign governments prevent U.S. trade in services from expanding to its full potential. The United States continues to negotiate trade agreements to lower these barriers. It was a leading force in concluding the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) in the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1994, and in past U.S. free trade agreements, all of which contain significant provisions on market access and rules for liberalizing trade in services. Trade negotiations involving trade in services currently under discussion include the following:

Expansion of services liberalization under WTO;

Recently approved U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA);

Phase One agreement with China and future Phase Two discussions; and

Potential bilateral trade agreement negotiations with the European Union (EU) and/or the United Kingdom (UK).

In each case, participants have difficult issues to address and the outlook for progress is uncertain. For most agreements, Congress may consider legislation to implement agreements potentially concluded in the future.

Congress and U.S. trade negotiators face additional issues, including how to balance the need for effective regulations of services with the objective of opening markets for U.S. exports and trade in services; ensuring adequate and accurate data to measure trade in services to inform trade policy; and determining whether further international cooperation efforts are needed to improve the regulatory environment for services trade beyond initial market access. This report provides background information and analysis on these and other emerging issues related to U.S. international trade in services. In addition, it examines existing and potential trade agreements as they relate to services trade.

U.S. Trade in Services: Trends and Policy Issues

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- U.S. Trade in Services

- Modes of Delivery

- Overall Trends

- Cross-Border Trade (Modes 1, 2, and 4)

- Commercial Presence (Mode 3)

- Geographical Distribution

- Trade by Type of Service

- World Trade in Services

- Global Value Chains and Services

- Barriers to Trade in Services

- The Economic Effects of Barriers to Services Trade

- U.S. Trade Agreements

- WTO

- GATS

- WTO Ongoing Negotiations

- Key Concepts for Services in FTAs

- Market Access and the Negative List Approach

- Rules of Origin

- Multiple Disciplines on Services

- Regulatory Transparency

- Regulatory Heterogeneity

- Current U.S. Trade Agreement Negotiations

- U.S. Trade Negotiating Objectives

- Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA)

- U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA)

- China

- Potential Trade Agreements with EU and/or UK

- Potential Issues for Congress

Figures

- Figure 1. Four Modes of Service Delivery

- Figure 2. U.S. Net Trade in Goods & Services, 1999-2018

- Figure 3. U.S. Exports by Mode, 2016

- Figure 4. U.S. Trade in Services by Geographic Region, 2018

- Figure 5. U.S. Services Supplied Through Majority-Owned Foreign Affiliates, 2017

- Figure 6. Services Supplied to U.S. Persons by Foreign MNEs Through Their MOUSAs, 2017

- Figure 7. U.S. Cross-Border Services Exports by Type of Service

- Figure 8. U.S. Services Exports by Type of Service Through U.S. Majority-Owned Foreign Affiliates

- Figure 9. Commercial Services Trade: Leading Exporters, 2018

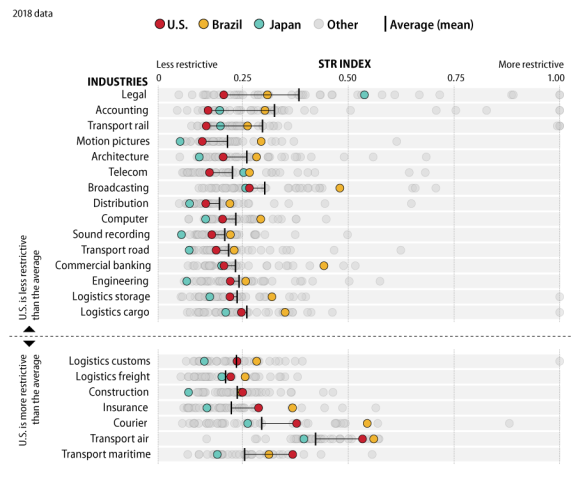

- Figure 10. Relative Trade Restrictiveness of the United States

Summary

Trade in "services" refers to a wide and growing range of economic activities. These activities include transport, tourism, financial services, use of intellectual property, telecommunications and information services, government services, maintenance, and other professional services from accounting to legal services. Compared to goods, the types and volume of services that can be traded are limited by factors such as the requirement for direct buyer-provider contact, and other unique characteristics such as the reusability of services (e.g., professional consulting) for which traditional value measures do not account. In addition to services as independent exports, manufactured and agricultural products incorporate and depend on services, such as research and development or shipping of intermediate or final goods. As services account for 71% of U.S. employment, U.S. trade in services, both services as exports and as inputs to other exported products, can have a broad impact across the U.S. economy.

Rapid advances in information technology and the related growth of global value chains have expanded both the level and the range of services tradable across national borders. As a result, services have become a priority in U.S. trade policy, and a significant part of U.S. trade flows and of global trade in general, accounting for $827 billion in U.S. exports in 2018. As the United States is the world's largest exporter and importer of services (14% and 10% of the global total in 2018), the Administration's discussions on potential and existing trade agreements that include services are significant.

A number of economists argue that "behind the border" barriers imposed by foreign governments prevent U.S. trade in services from expanding to its full potential. The United States continues to negotiate trade agreements to lower these barriers. It was a leading force in concluding the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) in the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1994, and in past U.S. free trade agreements, all of which contain significant provisions on market access and rules for liberalizing trade in services. Trade negotiations involving trade in services currently under discussion include the following:

- Expansion of services liberalization under WTO;

- Recently approved U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA);

- Phase One agreement with China and future Phase Two discussions; and

- Potential bilateral trade agreement negotiations with the European Union (EU) and/or the United Kingdom (UK).

In each case, participants have difficult issues to address and the outlook for progress is uncertain. For most agreements, Congress may consider legislation to implement agreements potentially concluded in the future.

Congress and U.S. trade negotiators face additional issues, including how to balance the need for effective regulations of services with the objective of opening markets for U.S. exports and trade in services; ensuring adequate and accurate data to measure trade in services to inform trade policy; and determining whether further international cooperation efforts are needed to improve the regulatory environment for services trade beyond initial market access. This report provides background information and analysis on these and other emerging issues related to U.S. international trade in services. In addition, it examines existing and potential trade agreements as they relate to services trade.

Introduction

Services are a significant element across the U.S. economy, at the national, state, and local levels. The term "services" refers to an expanding range of economic activities, such as audiovisual, construction, computer and related services, express delivery, telecommunications, e-commerce, financial, professional (such as accounting and legal services), retail and wholesaling, transportation, and tourism. Services not only function as end-use products but also facilitate the rest of the economy. For example, transportation services move intermediate products along global supply chains and final products to consumers; telecommunications services open e-commerce channels; and financial services provide credit for the manufacture and consumption of goods or the production of crops.

Services account for a majority of the U.S. economy—69% of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) and 71% of total U.S. employment.1 Services have also become a significant component of U.S. international trade, accounting for $827.0 billion of U.S. exports in 2018. As such, it is an increasingly important component of U.S. trade policy and of global trade in general.2

Rapid advances in information technology and the related growth of global value chains are making an expanding range of services tradable across national borders. However, certain characteristics have limited the types and volume of services that can be traded; for example, a hair stylist must be physically near a client. Other service providers are no longer required to be in the same location as the customer, such as a graphic designer who can send a product (e.g., an electronic file of a design) to a client across the globe.3 A number of economists have argued that foreign government barriers prevent U.S. trade in services from expanding to its full potential.4 Under the Trump Administration, the United States continues to engage in trade negotiations on multilateral, plurilateral, bilateral, and regional agreements with one goal being to lower these barriers.

Congress has a significant role to play in negotiating and implementing trade-liberalizing agreements, including those on services. In fulfilling its responsibilities for regulation of commerce and oversight of U.S. trade policymaking and implementation, Congress monitors trade negotiations and the implementation of trade agreements. Congress establishes trade negotiating objectives and priorities, including through trade promotion authority (TPA) legislation and consultations with the Administration. More directly, before a trade agreement requiring changes to U.S. law can enter into force in the United States, Congress would need to pass legislation to implement the agreement.

This report provides background information and analysis on U.S. international trade in services, including the types and volumes of traded services. It analyzes policy issues before the United States, especially relating to negotiating international disciplines on trade in services and the complexities in measuring trade in services. The report also examines emerging issues and current and potential trade agreements, including the recently approved U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) to replace the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), ongoing negotiations with China, ongoing multilateral and plurilateral negotiations at the World Trade Organization (WTO), and potential trade negotiations with the European Union and the United Kingdom.

U.S. Trade in Services

Modes of Delivery

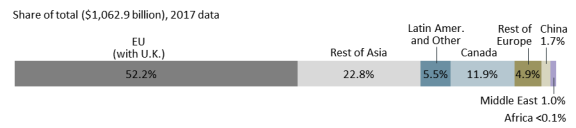

The basic characteristics of services are complex (especially compared to goods) due to their intangibility and their ability to be delivered via various formats, including electronically and direct provider-to-consumer contact. To address this complexity, members of the World Trade Organization have adopted a system of classifying four modes of delivery for services to measure trade in services and to classify government measures that affect trade in services in international agreements. The General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) modes of supply are defined based on the location of the service supplier and the consumer, taking into account their respective nationalities (see Figure 1).

|

|

Source: CRS based on WTO. |

Overall Trends

U.S. international trade in services plays an important role in the overall U.S. economy and global trade. The wide range of existing and potential services, from e-commerce to engineering, is delivered through multiple modes that often complement, or integrate with, one another.5

Measurements of trade in services are captured in two types of data: cross-border trade includes services sold via Modes 1, 2, and 4, described above.6 The second set of data measures services sold by an affiliate, that is, the services a local affiliate of a foreign company sells to a consumer of the local economy (Mode 3).7

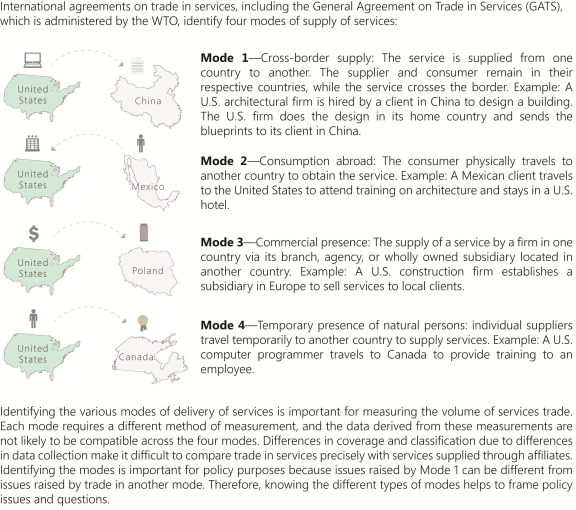

In 2018, total cross-border trade (Modes 1, 2, and 4), services accounted for 33.1% of the $2,501 billion total in U.S. exports (of goods and services) and 18.1% of the $3,129 billion in total U.S. imports.8 Figure 2 shows that the United States has continually realized surpluses in cross-border services trade, which have partially offset large trade deficits in goods trade in the U.S. current account.9 U.S. services net exports have been increasing in contrast to the expanding deficit in goods trade.

|

|

Source: CRS, based on data from U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. |

Cross-Border Trade (Modes 1, 2, and 4)

Information and communications technology (ICT)-enabled services fall under Mode 1 of cross-border services. These include services such as online banking, web-hosting, and services provided via telephone when providers and customers are from different countries. Given the increasing role of digital technologies in facilitating cross-border trade, in October 2016, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) began to identify trade in ICT services and potentially ICT-enabled (PICTE) services, reflecting the growth and economic impact of digital trade and digitally-enabled services.10 PICTE services include a wide array of services: insurance and financial services, as well as many business services like research, consulting, and engineering services which could be delivered electronically.

In 2018, exports of ICT services accounted for $71.4 billion of U.S. exports while potentially ICT-enabled services exports were another $451.9 billion, demonstrating the impact of the internet and digital revolution. Together, ICT and potentially ICT-enabled services were 63% of total U.S. service exports in (and 57% of U.S. service imports).

To measure the actual mode of cross-border delivery, as opposed to potential (e.g., a financial services consumer could travel abroad to a bank to conduct a transaction or do so online), BEA conducted a survey. BEA found that, for some sectors, such as computer and legal services, the vast majority is conducted via Mode 1 (e.g., by phone, online, etc.), while other services, such as education, are predominantly delivered in person with either the customer or provider traveling abroad (via Mode 2 or 4).11

Inbound travel and tourism is a big driver of Mode 2 exports (e.g., a Japanese tourist visits Washington, DC). Travel by foreigners to the United States had been increasing until April 2018. Since that time, it has declined slightly, apart from a rebound in February and March 2019. Some observers note the decline in U.S. travel exports reflects an overall global economic growth slowdown, while others contend it may be due to recent changes in U.S. domestic policies, including immigration and travel rules. U.S. exports of financial and business services has remained robust in 2019 (see Figure 6).

Commercial Presence (Mode 3)

Many services require direct contact between the supplier and consumer and, therefore, service providers often need to establish a presence in the country of the consumer through foreign direct investment (FDI). For example, providers of legal, accounting, and construction services usually prefer a direct presence because they need access to expert knowledge of the laws and regulations of the country in which they are doing business. They also require proximity to clients. Companies establish a commercial presence abroad through a foreign affiliate. It is unclear how advances in information and communications technology will affect trade in services via Mode 3 as virtual delivery via the internet expands the range of services offered and also drives increased demand.

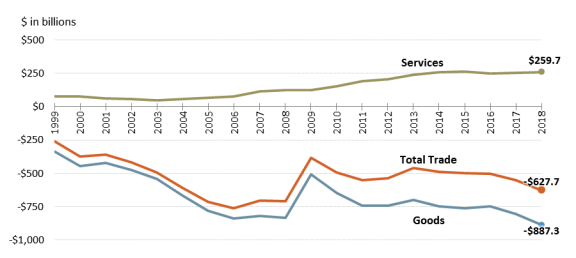

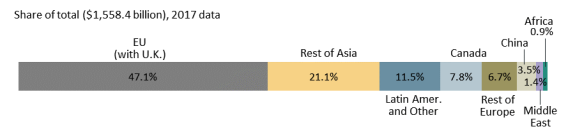

In 2017 (the latest year for which published data are available), U.S. firms sold $1,558 billion in services to foreigners through their majority-owned foreign affiliates, and foreign firms sold $1,083 billion in services to U.S. residents through their majority-owned foreign affiliates located in the United States.12 Although the data for cross-border trade and for sales by majority-owned affiliates are not directly comparable due to differences in coverage and classification, BEA created a mapping to measure services supplied by mode.13

The data presented in Figure 3 indicate that, in terms of magnitude, a large proportion of sales of services occurs through the commercial presence of companies in foreign markets rather than cross-border trade. Financial, computer, and distribution services are the largest sources of U.S. Mode 3 exports.

|

|

Source: CRS using data from Michael A. Mann, Measuring Trade in Services by Mode of Supply, U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, August 2019. Notes: * = n.i.e. (not included elsewhere.). Expend. = expenditures. |

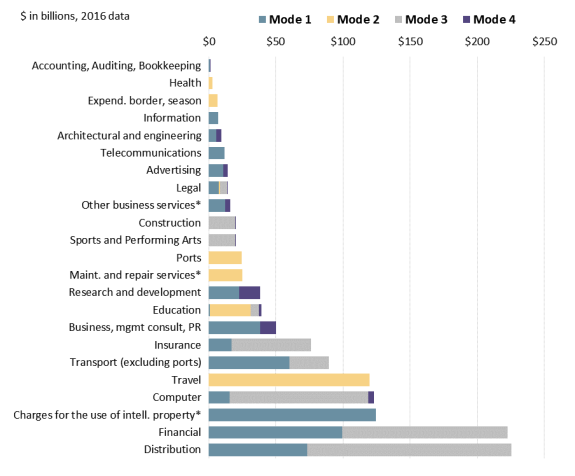

Geographical Distribution

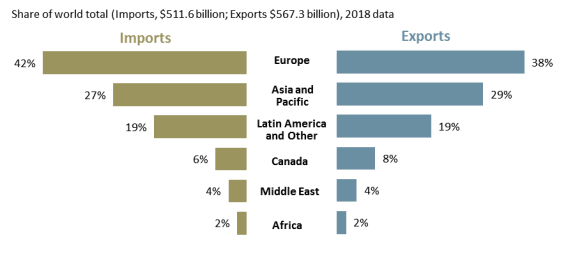

The United States supplies services (both via cross-border trade and FDI) to many different regions of the world (see Figure 4). Europe accounted for the majority of U.S. total trade in services. The United Kingdom (UK) alone accounted for 9% of U.S. services exports and 11% of services imports in 2018. Apart from the UK, 29% of U.S. exports of services went elsewhere in Europe, while 31% of U.S. imports of services came from those countries. Canada accounted for 8% of U.S. services exports and 6% of U.S. services imports; China was 7% and 3%, respectively, while other Asian and Pacific countries accounted for 23% of U.S. exports and 24% of imports of services in 2018. Japan's consumption of U.S. services was less than that of China, but Japan accounted for approximately double the amount of U.S. services imports, largely driven by U.S. affiliates of Japanese MNC's use of intellectual property.14

|

|

Source: CRS, based on data from the Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. |

Europe's dominance in U.S. services trade is more apparent when taking into account services that are provided through MNCs and their affiliates. In 2017 (latest data available), 47% of services supplied by U.S. MNCs were to foreign persons located in European Union countries, 25% to foreign persons located in Asian countries (including China), and 8% to foreign persons located in Canada (see Figure 5).

In 2017, 56% of sales of services to U.S. persons by U.S. affiliates of foreign-owned MNCs were by MNCs based in European countries; 25% by MNCs based in Asia (including China), Middle East, and Africa; and 12% by MNCs based in Canada.15

|

Figure 5. U.S. Services Supplied Through Majority-Owned Foreign Affiliates, 2017 |

|

|

Source: CRS, based on data from the Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. |

Trade by Type of Service

BEA divides cross-border services into nine categories:16

- Maintenance and repair;

- Transport;

- Travel (for all purposes including tourism, education);

- Insurance;

- Financial;

- Charges for the use of intellectual property (IP) (e.g., patents, trademarks, franchise fees);

- Telecommunications, computer, and information;

- Other business services (e.g., research and development, accounting, engineering); and

- Government goods and services.

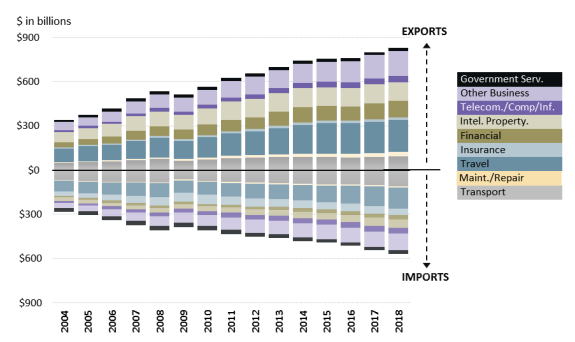

In 2018, U.S. exports covered a diverse range of services (see Figure 7). Travel accounted for the largest percent of U.S. services exports at 26%. Other business services, as well as royalties and fees generated from intellectual property, contributed another 20% and 16%, respectively. Transportation and financial services were 11% and 14%, respectively, of U.S. services exports.17

|

Figure 7. U.S. Cross-Border Services Exports by Type of Service |

|

|

Source: CRS, based on data from the Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. |

Sales of services by MNCs via commercial presence (Mode 3) include a broader range of industries. In 2017 (latest data available), the value of services sold by U.S.-owned MNCs through their foreign affiliates ranged from 17% for professional, scientific, and technical services and information services to 2% for manufacturing (see Figure 8).18

|

Figure 8. U.S. Services Exports by Type of Service Through U.S. Majority-Owned Foreign Affiliates |

|

|

Source: CRS, based on data from the Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. |

In the other direction, the total value of services supplied by foreign MNCs through their U.S. affiliates was smaller, but the composition of the services supplied was similar.

World Trade in Services

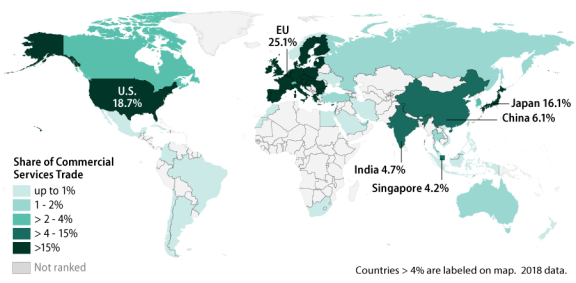

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) finds that services account for over two-thirds of global GDP and three-quarters of global FDI in advanced economies.19 According to the WTO, world exports of commercial services, excluding government procurement, increased to $5.63 trillion in 2018.20

The United States is the leading trader of services in global markets. If the European Union (EU) countries are treated separately, the United States was the largest single-country exporter (14.0%) and importer (9.8%) of global commercial services. 21 The United States was the second-largest exporter (18.7%) and importer (12.8%) in 2018, if the EU is treated as a single entity (see Figure 9).

|

Figure 9. Commercial Services Trade: Leading Exporters, 2018 |

|

|

Source: World Trade Organization, World Trade Statistical Review 2017. |

Global Value Chains and Services

Conventional trade data are not measured on a value-added basis and do not attribute any portion of the traded value of manufactured and agricultural products to services inputs, such as research and development, design, transportation costs, and finance. Instead, traditional data measure exports and imports of goods based on the value of the final product (e.g., medical device or t-shirt).

Measuring trade flows based on value-added22 rather than final cost, the OECD estimated that in 2015, close to 30% of the value of U.S. exports of manufactured goods was attributable to services inputs.23 Globally, approximately 75% of trade in services consists of intermediate inputs for the production of goods and services24 and services represent more than 50% of the value added in gross exports.25 This finding suggests a larger role for services in international trade than is reflected in conventional trade data.

The growth of global value chains (GVCs) in which economic activities are fragmented across multiple countries and regions has heightened the interdependence and interconnectedness of the global economy. GVCs provide industries access to wider markets and have the potential to increase productivity and efficiency, lower costs, and create new offerings for companies and consumers. U.S. firms have expanded global value chains using advances in information technology to bring goods and services to market. According to the WTO, GVCs covered 57% of world trade in 2015.26 China, the European Union, and United States were the top traders of intermediate goods in 2017.27 Computers, electronics, and optical products; motor vehicles; and textiles and apparel are the most "globally integrated" sectors, according to the OECD.28 GVCs may also serve as a motivator for countries involved at any point along a global value chain to seek more open markets for moving intermediate goods and service imports and exports.

Global value chains have expanded and redefined the role that services play in international trade and are one reason for growth in services trade. Despite a recent slowdown in globalization, the role of trade in services is likely to grow as global value chains expand in certain sectors and countries. Intermediate services embedded within a value chain include not only transportation and distribution to move goods along, but also research and development, design and engineering, as well as business services, such as legal, accounting, or financial services. The independent value of these services (as opposed to the value of the final product) can be captured in trade in value added statistics (see earlier discussion).29 As manufacturing and agriculture grow more complex and technologically advanced, their consumption of value-added services also grows.

Apart from producing and exporting intermediate goods, final imported goods often contain a significant amount of domestic services content. In the United States, the majority of value-added services in manufactured exports are domestic, but in some markets, such as Ireland, foreign services dominate the embedded value-added services. For example, a French wine imported into the United States may be transported by a U.S. express delivery service and use a label designed and printed by a U.S. marketing firm, while a gadget assembled domestically and exported by a U.S. firm may not only have components from abroad but also may rely on foreign research and engineering skills. With U.S. firms supplying many of the world's services, these findings imply that more U.S. services are traded internationally and many more service industry jobs in the United States are linked to international trade than traditional trade statistics indicate.

The WTO's "Made in the World" initiative finds that the increased use of GVCs has led industries to demand greater trade liberalization and lower protectionism as these firms depend on other links in the value chain, both domestic and foreign. The disaggregation of value chains into smaller pieces, or modules, opens up domestic and international business opportunities to specialized firms or small or mid-sized enterprises (SMEs) who can focus on one piece. As such, the strategic and potential economic impact of both trade barriers and efforts to liberalize trade in services may be greater than many people realize. By expanding through GVCs, U.S. industries could obtain greater and efficient access to markets, less expensive labor, and lower production costs, as well as talents and specializations from across the world.

However, using global supply chains entails potential costs and risks. Managing a complex supply chain across countries and/or time zones can be difficult and create additional costs. Some analysts point out that the benefits of increasingly interconnected supply chains may be offset by potential costs associated with overreliance on foreign or dispersed suppliers, or increased exposure or vulnerability to intellectual property rights theft or external shocks from abroad, such as an environmental disaster (e.g., earthquake) or market disturbances (e.g., financial crash or truck-driver strike).30

Unexpected changes in tariff rates is another risk that companies accept when sourcing from overseas. For example, the Trump Administration has imposed tariffs on multiple tranches of imports from China. China, in turn, has imposed retaliatory tariffs on certain U.S. imports.31 As a result of the ongoing trade dispute, some analysts and businesses have begun to question the merit of maintaining GVCs that rely on imports from other countries and some U.S. firms have shifted, or are considering shifting, supply chains to other countries or back to the United States.32

Barriers to Trade in Services

Liberalizing trade in services can be more complex than for goods, as the impediments are often "behind the border" barriers (occurring within the importing country) whereas those faced by goods suppliers, including tariffs and quotas, are frequently at the border.

The GATS identifies specific "market access" barriers and limits restrictions on the following: the number of foreign service suppliers, the total value of service transactions or assets, the number of transactions or value of output, the type of legal entity or joint venture through which services may be supplied, and the share of foreign capital in terms of maximum percentage limit on foreign shareholding or total value of foreign direct investment.

In many cases the impediments are government regulations or rules that appear legitimate but may intentionally or unintentionally discriminate against foreign providers and impede trade.

The right of governments to regulate service industries is widely recognized as prudent and necessary to protect consumers from harmful or unqualified providers. For example, doctors and other medical personnel must be licensed by government-appointed boards; lawyers, financial services providers, and many other professional service providers must be also certified in some manner. In addition, governments apply minimum capital requirements on banks to ensure their solvency. Each government can determine what it deems to be a prudent level of regulation. However, one concern in international trade is whether these regulations are applied to foreign service providers in a discriminatory and unnecessarily trade restrictive manner that limits market access. Because services transactions more often require direct contact between the consumer and provider than is the case with goods trade, many of the "trade barriers" that foreign companies face pertain to the establishment of a commercial presence in the consumers' country in the form of direct investment (Mode 3) or to the temporary movement of providers and consumers across borders (Modes 2 and 4).

|

Examples of Common Service Trade Barriers

|

The Economic Effects of Barriers to Services Trade

Most economists argue that by reducing barriers to trade in services, economies can more efficiently allocate resources, increasing general economic welfare. Opponents of liberalization in trade in services argue that a country would be forced to relinquish some regulatory control. Another factor to consider is that, as restrictions to trade are eliminated, cross-border trade via modes 1, 2, and 4 could grow at the expense of mode 3 if local presence is no longer a requirement to provide services in a particular country. However, removal of restrictions on foreign investment could offset any potential decline over the long term.34

The most significant barriers to trade in services are not readily quantifiable, and measuring their effects has challenges and limitations. Nontariff barriers for services specifically related to digital trade and data flows establish restrictions that may impact what a firm offers in a market or how it operates. For example, data transfer regulations that restrict cross-border data flows ("forced" localization barriers to trade), such as requiring locally-based servers, may limit the type of financial transactions and services that a firm can sell in a given country (see text box below). Similarly, country-specific data regulations may create a disincentive for U.S. firms to invest in certain markets if a firm is hindered in its ability to export its own data from a foreign affiliate to a U.S.-based headquarters in order to aggregate and analyze information from across its global operations. The proponents of data localization seek to ensure privacy of citizens, security, and domestic control. Others point out that maintaining data within a country does not necessarily guarantee security or protect a country from exposure to foreign attacks.35 Opponents of localization restrictions on digital trade also point to lost efficiencies and increased costs of not allowing a free flow of information across borders. According to the U.S. International Trade Commission, based on 2014 estimates, decreasing barriers to cross-border data flows would increase GDP in the United States by 0.1% to 0.3%.36

|

Localization Requirements as Trade Barriers Localization requirements by other countries can create trade barriers to U.S. businesses, whether in developed or developing economies. For example, the Reserve Bank of India's 2018 rule requires payment companies to locally store all information about transactions involving Indians, deterring U.S. payments providers and favoring domestic providers. Citing national security, China passed its cybersecurity law which requires companies that collect information on Chinese citizens to keep those data stored on domestic servers. According to the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR), abiding by such laws creates a challenge for U.S. companies seeking to do business in the growing Chinese market.37 |

The vast majority of U.S. small businesses that export rely on digital services such as online payment and e-commerce websites to facilitate export sales, but trade barriers (e.g., on the use of U.S. financial services) may limit the ability of U.S. firms to take advantage of online tools. A study by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and Google found that 9% of U.S. small businesses export but that more would do so given greater market access.38 The study estimates that with better access to export markets, small business exports would increase 14% over three years, generating $81 billion and adding over 900,000 U.S. jobs.

One OECD study analyzed the relationship between services trade restrictions, cross-border trade in services, and trade in downstream manufactured goods.39 The study finds that more restrictive countries not only import less in services but also export less, suggesting that restrictions also hurt the competitiveness of domestic industry. The negative effect of trade restrictions holds true across the various service sectors the researchers investigated. Financial services saw the greatest impact when restrictions changed; limitations on financial services were mostly in the form of market entry restrictions such as equity limits. Another OECD study finds that SMEs benefit relatively more compared to larger multinational firms from the reduction in market access barriers.40 U.S. SMEs cite foreign regulations as a top barrier hampering their ability to export services.41

According to the OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI), for 2018, the United States has a relatively open and competitive business environment in comparison to the 45 countries included in the study, as foreign providers have access and are allowed to compete equally in most sectors in the United States.42 The United States scored most open for rail freight transport, motion pictures, and distribution services, reflecting the highly competitive U.S. industry in these sectors. On the other hand, the study identifies air transport as the U.S. business sector with the most restrictions impacting foreign firms seeking to do business in the country. As an example, the STRI shows that the United States is much more open than Brazil for trade in broadcasting and commercial banking, but that both are relatively restrictive for international insurance trade. Figure 10 shows how the United States compares to other countries and the overall average score by sector. The STRI can also show the impact of a country's reform efforts. For example, reforms by Indonesia in 2016 reduced its trade restrictiveness in particular sectors, including sound recording and air transport, compared to 2014.43

|

Figure 10. Relative Trade Restrictiveness of the United States |

|

|

Source: CRS based on OECD, Services Trade Restrictiveness Index, http://www.oecd.org/tad/services-trade/services-trade-restrictiveness-index.htm. |

U.S. Trade Agreements

The United States has worked with trading partners to develop and implement rules on several fronts to reduce barriers and facilitate trade in services without infringing on the sovereign rights of governments to regulate services for prudential, sound regulatory, and national security reasons. The broadest and most challenging in terms of the number of countries involved are the multilateral rules contained in the General Agreement on Trade in Services that entered into force in 1995 and are administered by the 164-member World Trade Organization. The United States has also sought to go beyond the GATS (WTO-plus) under more comprehensive rules in the free trade agreements (FTAs) it has in force and in the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) to replace the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), as well as potential new trade agreements with China and the EU. Overall U.S. negotiating objectives, as defined in legislation (see "U.S. Trade Negotiating Objectives"), in each of these fora are to establish a more open, rules-based trade regime that is flexible enough to increase the flow of services and to take into account the expansion of types of services, but clear enough not to impede the ability of governments to regulate the sectors.44

|

Select Highlights of Services in Some U.S. Trade Agreements

|

One aspect of U.S. practice is that while trade negotiations are handled by the federal government, states often regulate services, including licensing and certification requirements. While regulations may vary across states, they all must comply with the commitments made by the federal government in international trade agreements.

WTO

The seeds for multilateral negotiations in services trade were planted more than 40 years ago. In the Trade Act of 1974, Congress instructed the Administration to push for an agreement on trade in services under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) during the Tokyo Round negotiations.45 While the Tokyo Round concluded in 1979 without a services agreement, the industrialized countries, led by the United States, continued to press for its inclusion in later negotiations. Developing countries, whose service sectors are less advanced than those of the industrialized countries, were reluctant to have services included. Eventually, services were included as part of the Uruguay Round negotiations launched in 1986.46 At the end of the round in 1994, countries agreed to a new set of rules for services, the GATS, and a new multilateral body, the WTO, to administer the GATS, the GATT, and the other agreements reached on financial services and telecommunications. Specific market access commitments were relatively limited.

GATS

The GATS provides the first and only multilateral framework of principles and rules for government policies and regulations affecting trade in services among the 164 WTO countries representing many levels of economic development. In so doing, it provides the foundation or floor on which rules in other agreements on services are based. As with the rest of the WTO, the GATS has remained a work in progress. The agreement is divided into six parts:47

Part I (Article I) defines the scope of the GATS. It provides that the GATS applies to the following:

- all services, except those supplied in the routine exercise of government authority;

- all government barriers to trade in services at all levels of government—national, regional, and local; and

- all four modes of delivery of services.

Part II (Articles II-XV) presents the "principles and obligations," some of which mirror those contained in the GATT for trade in goods, while others are specific to services. They include the following:

- unconditional most-favored-nation (MFN), nondiscriminatory treatment—services imported from one member country cannot be treated any less favorably than the services imported from another member country;48

- transparency—governments must publish rules and regulations;

- reasonable, impartial, and objective administration of government rules and regulations that apply to covered services;

- monopoly suppliers must act consistently with obligations under the GATS in covered services;

- a member incurring balance of payments difficulties may temporarily restrict trade in services covered by the agreement; and

- a member may circumvent GATS obligations for national security purposes.

Part III (Articles XVI-XVIII) of the GATS establishes market access and national treatment obligations for members. The GATS

- binds each member to its commitments once it has made them, that is, a member country may not impose less favorable treatment than that to which it has committed;

- provides market access by prohibiting member-country governments from placing limits on suppliers of services from other member countries regarding the number of foreign service suppliers, the total value of service transactions or assets, the number of transactions or value of output, the type of legal entity or joint venture through which services may be supplied, and the share of foreign capital or total value of foreign direct investment;

- requires that member governments accord service suppliers from other member countries national treatment, that is, a foreign service or service provider may not be treated any less favorably than a domestic provider of the service; and

- allows members to negotiate further reductions in barriers to trade in services.

Importantly, unlike MFN treatment and the other principles listed in Part II, which apply to all service providers more or less unconditionally, the obligations under Part III are restricted. They apply only to those services and modes of delivery listed in each member's schedule of commitments. Thus, unless a member country has specifically committed to open its market to service suppliers in a particular service that is provided via one or more of the four modes of delivery, the national treatment and market access obligations do not apply. This is often referred to as the positive list approach to trade commitments. Each member country's schedule of commitments is contained in an annex to the GATS.49 The schedules of market access commitments are, in essence, the core of the GATS.

|

Positive and Negative Lists Trade agreements may take a positive or negative list approach to identify each party's market access commitments and national treatment coverage. Positive list—Each member explicitly identifies which sectors and subsectors will be included and subject to the commitments of the agreement. Unless a member undertakes a specific commitment for a given category, it is not obliged to provide market access or national treatment to the service providers of other members. Parties may include different sectors and subsectors for market access and national treatment commitments. Each party may set conditions or exceptions to its commitments known as "limitations" or "reservations." The lists of sectors included by each member, and any exceptions, are usually included as an annex to the agreement, known as the schedules. Negative list—All sectors and subsectors are subject to the agreement's market access and national treatment commitments unless a member identifies specific exclusions through limitations or reservations. All newly created or domestically provided services are by default covered under this approach, unless explicitly excluded. The negative list is considered more comprehensive and clearly identifies sectors not opened. Nonconforming Measures (NCM)—Included in its list of exceptions, a party may list its nonconforming measures, any law, regulation, procedure, requirement, or practice that violates certain articles of the agreement but that the party will continue to enforce. |

Parts IV-VI (Articles XIX-XXIX) are technical elements of the agreement. Among other things, they require that, no later than 2000, the GATS members start new negotiations (which they did) to expand coverage of the agreement and that conflicts between members involving implementation of the GATS are to be handled in the WTO's dispute settlement mechanism. The GATS also includes eight annexes, including one on MFN exemptions. Another annex provides a "prudential carve out," that is, a recognition that governments take "prudent" actions to protect investors or otherwise maintain the integrity of the national financial system. These prudent actions are allowed, even if they conflict with obligations under the GATS.

Not all of the issues in services were resolved when the Uruguay Round negotiations ended in 1994. Fifty-six WTO members, mostly developed economies, negotiated and concluded an agreement in 1997 in which they made commitments on financial services. The schedules of commitments largely reflected national regimes already in place.50 Furthermore, 69 WTO members negotiated and concluded an agreement in 1997 on telecommunications services. That agreement laid out principles on competition safeguards, interconnection policies, regulatory transparency, and the independence of regulatory agencies. Both agreements were added to the GATS as protocols.51 Today, a total of 108 WTO members have made some level of commitment to facilitate trade in telecommunications services.52

WTO Ongoing Negotiations

Article XIX of the GATS required WTO members to begin a new set of negotiations on services in 2000 as part of the so-called WTO "built-in agenda" to complete what was unfinished during the Uruguay Round and to expand the coverage of the GATS to further liberalize trade in services. The Doha Round launched in November 2001 included services negotiations, but after nearly two decades of negotiations, members did not achieve its agenda. Put simply, the large and diverse membership of the WTO made consensus on the broad Doha mandate difficult. The latest WTO Ministerial Conference in December 2017 served as an opportunity for members to take stock of ongoing talks and further define priority work areas. Members did not conclude any multilateral agreements at the Ministerial, but there was a joint statement by at least 60 countries seeking to address domestic regulation. The group did not include the United States, although it may decide to join any agreement at a later date.

The U.S. delegation remains active in the broader Working Party on Domestic Regulation.53 The Committee on Specific Commitments continues discussing how members can classify digital services, whether they are new services or a new means for delivering existing services. The WTO continues to hold educational and outreach workshops on domestic regulations to facilitate services trade.54

Frustration with WTO negotiations has likely contributed to the proliferation of bilateral and regional trade agreements that include provisions on services and services-related activities (for example, foreign direct investment) and for alternative frameworks.

Key Concepts for Services in FTAs

The United States has made services a priority in each of its FTAs. While the specific treatment of services differs among the FTAs because of the status of U.S. trade relations with the partner(s) involved and the evolution of issues, the FTAs share some characteristics that define a framework of U.S. policy priorities. Some of these aspects reaffirm adherence to principles embedded in the GATS, while others go significantly beyond the GATS.

Market Access and the Negative List Approach

Each U.S. FTA uses a negative list in determining market access commitments and national treatment coverage and commitments from each partner. A negative list means that the FTA provisions for market access and national treatment apply to all categories and subcategories of services in all modes of delivery, unless a party to the agreement has listed a service or mode of delivery as an exception. The negative list implies that a newly created or domestically provided service is automatically covered under the FTA, unless it is specifically listed as an exception in an annex to the agreement. The negative list approach is widely considered to be more comprehensive and flexible than the positive list, which is used in the GATS and which some other countries use in their bilateral and regional FTAs.

Rules of Origin

Under FTAs in which the United States is a party, any service provider is eligible for the FTA benefits irrespective of ownership nationality as long as that provider is an enterprise organized under the laws of either the United States or the other party(ies) or is a branch conducting business in the territory of a party. Such criteria potentially expand the benefits of the FTA to service providers from other countries that are not direct parties to the FTA. For example, a U.S. subsidiary of a Canadian-owned insurance company would be covered by the U.S.-South Korea FTA. The FTAs do allow one party to deny benefits to a provider located in the territory of another party, if that provider is owned or controlled by a person from a nonparty country and does not conduct substantial business in the territory of the other party, or if the party denying the benefits does not otherwise conduct normal economic relations with the nonparty country.55

Multiple Disciplines on Services

In many U.S. FTAs, trade in services spans several chapters, indicating its prominence in U.S. trade policy, the complexity in addressing services trade barriers, and the specificity of U.S. trade policy negotiating objectives. Each FTA has a specific chapter on cross-border trade in services—trade by all modes except commercial presence (Mode 3). This chapter requires the United States and the FTA partner(s) to accord nondiscriminatory treatment—both MFN treatment and national treatment—to services originating in each other's territory. The agreement prohibits the FTA partner-governments from imposing restrictions on the number of service providers, the total value of service transactions that can be provided, the total number of service operations or the total quantity of services output, or the total number of natural persons that can be employed in a services operation. In addition, the governments cannot require a service provider from the other FTA partner to have a presence in its territory in order to provide services. The FTA partners may exclude categories or subcategories of services from the agreement, which they designate in annexes.

Each U.S. FTA also contains a chapter on foreign direct investment, including service providers that have a commercial presence (Mode 3) in the territory of an FTA partner and a chapter on intellectual property rights (IPR), which is also relevant to services trade.56 In addition, many U.S. FTAs contain separate provisions or chapters on specific service categories which have been priority areas in U.S. trade policy. They include the following:

- Financial Services: The FTAs define financial services to "include all insurance and insurance-related services, and all banking and other financial services, as well as services incidental or auxiliary to a service of a financial nature." Among other things, the financial services chapter allows governments to apply restrictions for prudential reasons and allows financial service providers from an FTA partner to sell a new financial service without additional legislative authority, if local service providers are allowed to provide the same service.

- Telecommunication Services: The United States and trading partners agree that enterprises from each other's territory are to have nondiscriminatory access to public telecommunications services. For example, both countries will ensure that domestic suppliers of telecommunications services who dominate the market do not engage in anticompetitive practices. They also ensure that public telecommunications suppliers provide enterprises based in the territory of the FTA partner with interconnection, number portability, dialing parity, and access to underwater cable systems.

- E-commerce/Digital Trade: The FTAs include provisions to ensure that electronically supplied services are treated no less favorably than services supplied by other modes of delivery and that customs duties are not applied to digital products whether they are conveyed electronically or via a tangible medium such as a disk. Recent and ongoing trade negotiations seek to ensure open digital trade by prohibiting "forced" localization or other requirements that limit cross-border flows.57

Regulatory Transparency

Many U.S. FTAs require FTA partners to practice transparency when implementing and developing domestic regulations that affect services. In particular, the FTAs require the partner countries to provide notice of impending investigations that might affect service providers from the other partner(s). The FTAs go beyond the transparency provisions in the GATS by providing mechanisms for interested parties to comment on proposed regulations and appeal adverse decisions.

Regulatory Heterogeneity

In addition to market access restrictions, firms operating in multiple countries or having a global supply chain may be subject to an array of local regulations that vary in each market, and impact the services that firms can access or sell. This regulatory heterogeneity, while neither discriminatory nor anticompetitive, may increase operational costs and thereby limit a firm's ability to do business in a foreign market. For example, regulatory heterogeneity can limit the access of professional service providers (e.g., architects, doctors) whose licenses or certifications may not be recognized in foreign markets. Because regulatory cooperation, such as when countries or regions harmonize to common standards or establish mutual recognition, can help minimize the impact of the differing regulatory regimes, some stakeholders seek to mandate such efforts under trade agreements.58 The U.S.-South Korea FTA is one example of using FTA negotiations to address differing regulatory regimes for services (see below). Regulatory cooperation to ease trade in services may also occur outside of FTA negotiations.

Current U.S. Trade Agreement Negotiations

U.S. Trade Negotiating Objectives

The Trade Promotion Authority legislation signed into law on June 29, 2015,59 contained specific provisions establishing U.S. trade negotiating objectives on services trade (P.L. 114-26). The text states that "[t]he principal negotiating objective of the United States regarding trade in services is to expand competitive market opportunities for the United States." Congress also specifically pointed to the utilization of global value chains and supported pursuing the objectives of reducing or eliminating trade barriers through "all means, including through a plurilateral agreement" with partners able to meet high standards.

Congress provided objectives specific to "digital trade in goods and services and cross-border data flows," instructing the President to ensure that cross-border data flows and electronically delivered goods and services have the same level of coverage and protection as those in physical form, and are not impeded by regulation, excepting for legitimate objectives. Congress recognized the challenges presented by localization regulations, and sought to ensure that trade agreements eliminate and prevent measures requiring the locating of "facilities, intellectual property, or other assets in a country."

Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA)60

Largely because of the lack of progress in the WTO, negotiations on a proposed Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) were launched in April 2013 to achieve a sector-specific, plurilateral agreement to liberalize trade in services.61 The group of 23 WTO members—including the United States—account for around 70% of world trade in services.62 The Trump Administration has not stated an official position on the continuation of TiSA negotiations, but USTR Robert Lighthizer indicated that the Trump Administration may support its continuation.63

For proponents of services trade liberalization, the plurilateral approach offers some advantages, such as holding negotiations among countries willing to negotiate further liberalization and thus potentially enhancing prospects for a successful conclusion; providing flexibility in the scope of the agreement that can be expanded as countries accede to its provisions; and aiming to reduce barriers to trade and services beyond the limited commitments under the GATS and the offers made in multilateral settings.

However, critics highlight possible drawbacks to the approach, including the lack of participation of some of the economically significant emerging economies, such as Brazil, India, and China, which present larger potential market opportunities for services but also impose significant impediments to trade and investment in services. In addition, a plurilateral services pact might further diminish the credibility of, and likelihood of concluding new agreements through, the multilateral trade negotiation framework.

If negotiations restart, participants would need to need to determine whether "new services" would be included under the nondiscrimination obligations. Many "new services" may be delivered digitally (e.g., telemedicine), and it is unclear how much overlap there would be with ongoing plurilateral negotiations on digital trade launched at the 2017 WTO Ministerial.64

U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA)

On May 18, 2017, the Trump Administration sent a 90-day notification to Congress of its intent to begin talks with Canada and Mexico to renegotiate and modernize NAFTA, as required by the TPA. Talks officially began on August 16, 2017. Negotiations were concluded on September 30, 2018, and Congress approved the final agreement on January 16, 2020.65

Since its entry into force on January 1, 1994, NAFTA largely has supported greater economic integration of the North America continent and a more competitive North American marketplace. The original NAFTA eliminated most tariff and non-tariff barriers and includes chapters on cross-border trade in services, telecommunications, and financial services, as well as temporary entry for business persons. 66 The Trump Administration aimed to "modernize" NAFTA through renegotiation and address new issues. NAFTA contained the first "negative list" services chapter in a U.S. free trade agreement, and it is maintained in the proposed USMCA. The USMCA builds on NAFTA services liberalization with additional commitments including on electronic payment cards, telecommunications mobile providers, and international roaming.

With highly integrated supply chains, North American countries rely on services trade to move and track products across borders multiple times before a finished product is ready for its final sale. Trade facilitation measures simplify and streamline procedures to allow the easier flow of trade across the borders of the three countries, reducing the costs of trade for service providers and customers. In the USMCA, parties affirmed their rights and obligations under the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA).67 In addition, the USMCA contains a separate annex on express delivery to ensure a level playing field between government-owned and -operated postal system and private firms.

Signed in 1993, NAFTA did not contain provisions to address barriers and rules and disciplines on digital trade. The new USMCA Digital Trade chapter promotes digital trade and the free flow of information, and ensures an open internet. USMCA aims to ensure a level playing field for ICT-enabled services with obligations covering non-discriminatory treatment, prohibitions on cross-border data flows restrictions and data localization requirements, and more. The financial services chapter also contains a prohibition on data localization requirements while guaranteeing regulators have the necessary access to data. Open data flows will provide more opportunities for U.S. businesses to serve customers in Mexico and Canada digitally through Mode 1. For example, if USMCA goes into force, Canada's government would be required to change procurement contracts with data localization provisions, allowing U.S.-based service providers to bid. On the other hand, Canada negotiated a carve-out for cultural industries from its audiovisual services commitments.

The U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement, signed in October 2019, parallels the USMCA digital trade chapter but does not cover broader trade in services liberalization.68

China69

China's services market is of strong interest to the United States because of U.S. industry's competitive position in services and the prospects for service sector growth in China. Current levels of U.S. service exports to China, however, remain low relative to U.S. service exports to other U.S. top trading partners (see "Geographical Distribution"). Many subsectors in China's services market remain heavily restricted, including banking, electronic payments, insurance, and fin tech; theatrical films and audio-visual services; express delivery, internet, cloud-based and technology services; legal services; value-added telecommunications; and transportation.70 Made in China 2025 and China's other industrial policies have strong services components, as China looks to reduce its reliance on foreign providers and promote national champions in service-oriented advanced manufacturing and a wide range of technology-related services.71 In 2017, the Chinese government announced plans to set up a $4.4 billion fund to increase value added exports in services, particularly financial services and technology.72

Of the $57.1 billion U.S. service exports to China in 2018, 65% ($37.1 billion) was travel services. The United States imported $18.3 billion in services from China in 2018, of which almost half ($8.8 billion) was transportation and travel services.73 Services constituted approximately 52% of China's nominal GDP in 2018. China's 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-2020) targeted boosting services as a percentage of China's GDP to 56% by 2020.

While China made significant market opening commitments in services when it joined the WTO in 2001, it has since been reluctant to make further significant services concessions. China's FTAs have focused on market access in goods for the most part, and its bilateral commitments in services have been minimal. For example, in its FTA with Australia in 2015, China made small concessions in some services sectors—telecommunications, health care, construction and engineering, tourism, and transport—but licensing was restricted to the Shanghai Free Trade Zone, denying national market access.74 China also deferred service openings in its FTA with South Korea in 2015.75 As noted, China is not party to TiSA discussions. This is in part because the United States and some other countries are concerned China could be obstructionist at the table. Analysts point to how China's reticence to make concessions in other plurilateral talks—such as the WTO Information Technology Agreement II in 2013 and environmental goods negotiations in 2016—prolonged negotiations, jeopardized outcomes, and raised concerns about how China might undermine other negotiations, such as TiSA.76 China also may not be as interested in trade agreements that require parties to liberalize in reciprocal fashion, at least with regard to certain types of services investments in developing markets. China's One Belt One Road (OBOR) strategy, for example, has allowed Chinese companies to expand into services markets overseas—including internet, finance, logistics, shipping, telecommunications, and transportation—through Chinese government-financed deals that do not require China having to reciprocate and liberalize access to these same sectors in China.

China has made some openings in financial services but liberalization and implementation are uneven. China often informally caps the number of firms eligible to participate in market openings and slows implementation through the licensing process.77 China has delayed implementation of its WTO accession commitments in bank card services since 2001 and stalled for more than seven years in fulfilling its obligations to license U.S. firms following a WTO ruling in 2012 that found China had discriminated against U.S. credit card companies in favor of a state monopoly, China UnionPay.78 As part of negotiations on a subset of trade and investment issues the United States raised in March 2018 under Section 301 of the U.S. Trade Act of 1974, China promised to selectively reduce some foreign equity limits and restrictions in financial services, likely in an effort to generate pockets of U.S. business support.79 China's Securities and Regulatory Commission announced in October 2019 a phased plan whereby it would remove ownership caps in futures, mutual funds and securities funds; allow some foreign financial firms to increase their minority stakes to 51%; and qualify a certain number of foreign firms to have full ownership of license ventures in futures (January 1), mutual funds (April 1), and securities (December 1).80 China has also said it will allow foreign financial firms to establish insurance firms and wholly-foreign owned banks in China.81 Next steps for the United States with China on services are likely to be a U.S. focus on China's implementation of these financial service commitments and attention to technology-related services as the United States turns to concerns about China's protectionist IP, innovation, and industrial policies.

Potential Trade Agreements with EU and/or UK

The United States and the EU share a massive, highly integrated economic relationship as each other's largest trade and FDI partners. U.S.-EU trade ties are deep, but some barriers to trade and investment remain. Over the years, the two sides have sought to further liberalize trade and investment ties, enhance regulatory cooperation, and work together on international economic issues of joint interest, including through international institutions, such as the WTO and TiSA negotiations.

On October 16, 2018, the Trump Administration notified Congress under TPA of its intent to enter into negotiations with the EU. The TPA notification followed the July 2018 Joint Statement (agreed between President Trump and European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker) that aimed to de-escalate existing trade tensions.82 USTR's negotiating objectives include trade in services, as well as additional commitments for specific sectors such as financial services, telecommunications, and express delivery.83 The United States seeks to negotiate on a negative list basis with narrow exceptions. U.S. objectives also include digital trade in services and cross-border data flows, essential for Mode 1 ICT-enabled services. The EU negotiating mandate, in contrast, is limited to the elimination of tariffs for industrial goods only and an agreement on conformity assessment.84 The negotiations appear to be at an impasse due to lack of U.S.-EU consensus on their scope, but this may change given the installation of the new EU Commission in December 2019.

Although it remains pending, the UK's withdrawal from the EU (so-called Brexit) could affect the negotiations, as it would remove a traditionally leading voice on trade liberalization from the EU. The UK accounted for approximately 10% of each U.S. service exports and imports in 2018, and 30% of U.S. services trade with the EU overall. Potential U.S.-UK trade negotiations could apply competitive pressure on U.S.-EU trade negotiations, but hinge on whether the UK regains an independent national trade policy or regulatory regime post-Brexit.85

Potential Issues for Congress

To date, the record on liberalization of trade in services through reciprocal trade agreements is mixed. The 164 members of the WTO negotiated and have maintained a basic set of multilateral rules in the form of the GATS. However, the GATS is largely viewed as limited in scope, predating significant technological developments over the past two decades, and in need of expansion if it is to be an effective instrument of trade liberalization. The efforts of the WTO members to expand on these rules have stalled, with little prospect of success in the foreseeable future. The lack of progress in the WTO negotiations due to the complexity of the issues and parties involved has led to the rise of sector-specific plurilateral agreements as an alternative path forward. In negotiating TiSA, the United States has been pursuing a services-specific plurilateral agreement that includes the 28-member EU and Japan—two of the most important U.S. trade partners that the United States does not have an FTA with—plus other participating countries.

The United States has made services trade liberalization and rules-setting an important component of the FTAs it has negotiated and is currently renegotiating. While these agreements have gone beyond the GATS in terms of coverage, they apply to a limited number of countries, accounting for small shares of U.S. trade in services.

The outlook for the ongoing negotiations remains uncertain, as participants in each negotiation deal with difficult and complex issues. Potential policy issues for Congress and negotiators to address include the following:

- To what extent are U.S. positions on trade in services in the USMCA, TiSA, or ongoing bilateral negotiations consistent with U.S. trade negotiating objectives on services as defined in the TPA legislation? How might Congress work with the Administration in relation to these negotiations?

- How could the conclusion of or withdrawal from one agreement impact negotiations in the others? What impact would these proposed agreements, or withdrawal from existing agreements, have on the U.S. economy and various stakeholders? How might the conclusion of more limited trade liberalization trade agreements that do not cover services with a trading partner (e.g., Japan or the EU) impact the likelihood of their future expansion to include services?86

- Advancements in information technology expand the number and types of services that can be traded and help to create new types of services. Is it possible to develop a trade arrangement that is clear enough to be effective and flexible enough to take into account rapid changes in the services sector? Should the U.S.-Japan Digital Trade Agreement serve as a model for future sectoral negotiations on digital services?

- Should the executive branch pursue enhanced regulatory cooperation with key trading partners or mutual recognition efforts in specific service sectors to lessen the burdens created by varied regulatory regimes and requirements across different markets? Given the role of state regulators, how might U.S. policymakers involve them in ongoing and future trade negotiations or regulatory cooperation efforts?

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

U.S. International Trade Commission, Recent Trends in U.S. Services Trade: 2019 Annual Report, Publication 4975, September 2019, p. 13. |

| 2. |

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Trade in Goods and Services table: http://www.bea.gov/international/index.htm. |

| 3. |

These services are considered Information and communications technology (ICT)-enabled or potentially ICT-enabled (PICTE) services. |

| 4. |

See, for example, J. Bradford Jensen, Global Trade in Services: Fear, Facts, and Offshoring, Peterson Institute for International Economics, August 2011, p. 7. |

| 5. |

U.S. International Trade Commission, Recent Trends in U.S. Services Trade: 2017 Annual Report, May 2017, p. 21, https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/pub4682.pdf. |

| 6. |

For example, the purchase by a foreign visitor of a hotel stay and of other services in the United States are counted as U.S. exports and such purchases by a U.S. visitor to a foreign country are counted as U.S. imports from that country. |

| 7. |

Affiliates are enterprises that are directly or indirectly owned or controlled by an entity in another country to the extent of 10% or more ownership of the voting stock for an incorporated business, or an equivalent interest for an unincorporated business. |

| 8. |

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, online tool http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_ita.cfm. |

| 9. |

The current account includes trade in goods and services as well as income earned on investments and unilateral transfers. |

| 10. |

For more information, see Grimm, Alexis N., BEA, Trends in U.S. Trade in Information and Communications Technology (ICT) Services and in ICT-Enabled Services, May 2016, http://www.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2016/05%20May/0516_trends_%20in_us_trade_in_ict_serivces2.pdf |

| 11. |

Michael A. Mann, "Measuring Trade in Services by Mode of Supply," BEA, August 2019. |

| 12. |

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, online tool http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_ita.cfm. |

| 13. |

More information on services data definitions can be found at http://www.bea.gov/international/international_services_definition.htm. |

| 14. |

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), online tool http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_ita.cfm. |

| 15. |

Ibid. |

| 16. |

As of June 4, 2014, the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) updated its presentation of trade in services to align with the International Monetary Fund Balance of Payments Manual. For additional information, see "Comprehensive Restructuring and Annual Revision of the U.S. International Transactions Accounts," published in the July 2014 BEA Survey of Current Business. |

| 17. |

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), online tool http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_ita.cfm. |

| 18. |

Ibid. Note that U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis uses the terms "MNE" to signify multinational enterprises which is equivalent to MNC, "MOUSAs" for majority-owned U.S. affiliates of foreign enterprises, and "MOFAs" for majority-owned foreign affiliates of U.S. enterprises. |

| 19. |

OECD (2017), Services Trade Policies and the Global Economy, OECD Publishing, Paris. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264275232-en. |

| 20. |

World Trade Organization, World Trade Statistical Review 2019, 2019, p. 9, https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/wts2017_e/wts2017_e.pdf. |

| 21. |

As of December 2019, the EU includes 28 member states. |

| 22. |

Trade in value-added is a statistical approach that estimates the source(s) of value (by country and industry) that is added in producing goods and services for export (and import). It traces the value added by each industry and country in the global supply chain and allocates the value-added to these source industries and countries. More information on Trade in Value Added can be found at http://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/whatistradeinvalueadded.htm. |

| 23. |

OECD, Trade in Value Added: United States, December 2018. |

| 24. |

OECD (2017), Services Trade Policies and the Global Economy, OECD Publishing, Paris, p. 19, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264275232-en. |

| 25. | |

| 26. |

WTO, World Trade Statistical Review 2019, 2019, p. 42, https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/wts2019_e/wts19_toc_e.htm. |

| 27. |

Ibid., Table A54. |

| 28. | |

| 29. |

Trade in value-added is a statistical approach that estimates the source(s) of value (by country and industry) that is added in producing goods and services for export (and import). It traces the value added by each industry and country in the global supply chain and allocates the value-added to these source industries and countries. More information on Trade in Value Added can be found at http://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/whatistradeinvalueadded.htm. |

| 30. |

Aaditya Mattoo, Services Trade and Regulatory Cooperation, E15, July 2015, http://e15initiative.org/. |

| 31. |

For more information on U.S.-China relations, see CRS Report R45898, U.S.-China Relations, coordinated by Susan V. Lawrence. |

| 32. |

AmCham China, "Impact of U.S. and Chinese Tariffs on American Companies in China," https://www.amchamchina.org/uploads/media/default/0001/09/7d5a70bf034247cddac45bdc90e89eb77a580652.pdf. |

| 33. |

OECD, Working Party of the Trade Committee Assessing Barriers to Trade in Services—Revised Consolidated List of Cross-Sectoral Barrier, Paris, February 28, 2001. |

| 34. |

For more information, see Tamar Khachaturian and David Riker, The Effects of U.S. Trade Agreements on Foreign Affiliate Transactions in Services, U.S. International Trade Commission, Working Paper 2017-03-C, March 2017, https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/fta_mt.pdf. |

| 35. |

For more on data vulnerabilities and cybersecurity, see CRS Report R43317, Cybersecurity: Legislation and Hearings, 115th-116th Congresses, by Rita Tehan. |

| 36. |

United States International Trade Commission, Digital Trade in the U.S. and Global Economies, Part 2, 2014, pp. 13-14. |

| 37. |

USTR, 2017 National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers, Office of the United States Trade Representative, 2017, p. 71, and Communication from the United States to the WTO Members of the Council for Trade in Services, Measures Adopted and Under Development by China Relating to its Cybersecurity Law, September 25, 2017. |

| 38. | |

| 39. |

Nordås, H. K. and D. Rouzet (2015), "The Impact of Services Trade Restrictiveness on Trade Flows: First Estimates", OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 178, OECD Publishing. |

| 40. |