Introduction

The term "services" refers to an expanding range of economic activities, such as audiovisual; construction; computer and related services; energy; express delivery; e-commerce; financial; professional (such as accounting and legal services); retail and wholesaling; transportation; tourism; and telecommunications. Services account for a majority of the U.S. economy—78% of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) and 82% of U.S. civilian employment.1 Services are an important element across the U.S. economy, at the national, state, and local levels. They not only function as end-use products but also act as the "lifeblood" of the rest of the economy. For example, transportation services move intermediate products along global supply chains and final products to consumers; telecommunications services open e-commerce channels; and financial services provide credits for the manufacture and consumption of goods.

Services have become an important component in U.S. international trade and, therefore, an increasingly important priority of U.S trade policy and of global trade in general. Services accounted for $752.4 billion of U.S. exports in 2016.2

Rapid advances in information technology and the related growth of global value and supply chains are making an expanding range of services tradable across national borders. However, the intangibility of services and other characteristics have limited the types and volume of services that can be traded. A number of economists have argued that foreign government barriers prevent U.S. trade in services from expanding to their full potential.3 Under the Trump Administration, the United States may continue to engage in trade negotiations on multilateral, plurilateral, bilateral, and regional agreements to lower these barriers.

Congress has a significant role to play in negotiating and implementing trade liberalizing agreements, including those on services. In fulfilling its responsibilities for oversight of U.S. trade policymaking and implementation, Congress monitors trade negotiations and the implementation of trade agreements. Congress establishes trade negotiating objectives and priorities, including through trade promotion authority (TPA) legislation and consultations with the Administration. More directly, Congress must pass legislation to implement a trade agreement requiring changes to U.S. law before it can enter into force in the United States.

This report provides background information and analysis on U.S. international trade in services. It analyzes policy issues before the United States, especially relating to negotiating international disciplines on trade in services and dealing complexities in measuring trade in services. The report also examines emerging issues and current and potential trade agreements, including the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA), and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP).

U.S. Trade in Services

Modes of Delivery

The basic characteristics of services (especially compared to goods) are complex due to their intangibility and their ability to be conveyed via various formats, including electronically and direct provider-to-consumer contact. To address this complexity, members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) have adopted a system of classifying four modes of delivery for services to measure trade in services and to classify government measures that affect trade in services in international agreements (see the text box below).

|

Four Modes of Services Delivery4 International agreements on trade in services, including the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), which is administered by the WTO, identify four modes of supply of services: Mode 1—Cross-border supply: The service is supplied from one country to another. The supplier and consumer remain in their respective countries, while the service crosses the border. Example: A U.S. architectural firm is hired by a client in China to design a building. The U.S. firm does the design in its home country and sends the blueprints to its client in China. Mode 2—Consumption abroad: The consumer physically travels to another country to obtain the service. Example: A Mexican client travels to the United States to attend training on architecture and stays in a U.S. hotel. Mode 3—Commercial presence: The supply of a service by a firm in one country via its branch, agency, or wholly owned subsidiary located in another country. Example: A U.S. construction firm establishes a subsidiary in Europe to sell services to local clients. Mode 4—Temporary presence of natural persons: individual suppliers travel temporarily to another country to supply services. Example: A U.S. computer programmer travels to Canada to provide training to an employee. Identifying the various modes of delivery of services is important for measuring the volume of services trade. Each mode requires a different method of measurement, and the data derived from these measurements are not likely to be compatible across the four modes, that is, one cannot combine the data on services traded via Mode 1 with data derived from services traded via Mode 3 in order to obtain a total. Identifying the modes is also important for policy purposes because issues raised by trade in Mode 1 can be different from issues raised by trade in another mode. Therefore, knowing the different modes helps to frame policy issues and solutions. |

Overall Trends

U.S. international trade in services plays an important role in overall U.S. economy and international trade. The wide-range of existing and potential services, from e-commerce to engineering, is delivered through multiple modes that often complement, or integrate with, one another.5

Measurements of trade in services are captured in two types of data: cross-border trade includes services sold via Modes 1, 2, and 4, described above.6 The second set of data measures services sold by an affiliate of a company from one country in the territory and to a consumer of another country (Mode 3).7

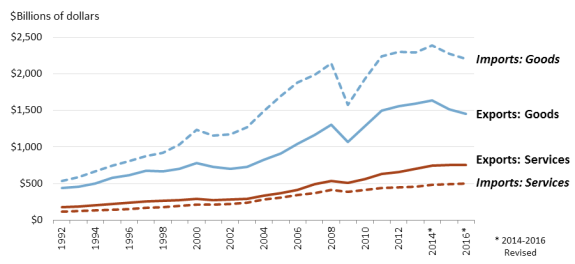

For cross-border trade, in 2016, services accounted for 34.1% of the $2,208 billion total U.S. exports (of goods and services) and 18.6% of the $2,713 billion total U.S. imports.8 Figure 1 shows that the United States has continually realized surpluses in services trade, which have partially offset large trade deficits in goods trade in the U.S. current account.9

|

Figure 1. U.S. Cross-Border Trade in Goods and Services, 1993-2016 |

|

|

Source: CRS, based on data from U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. |

Many services require direct contact between the supplier and consumer and, therefore, service providers often need to establish a presence in the country of the consumer through foreign direct investment (FDI). For example, providers of legal, accounting, and construction services usually prefer a direct presence because they need access to expert knowledge of the laws and regulations of the country in which they are doing business and they require proximity to clients. One question is whether this will change with advances in technology and as virtual presence by service provider becomes easier, allowing for greater cross-border trade.

In 2014 (the latest year for which published data are available), U.S. firms sold $1,503.4 billion in services to foreigners through their majority-owned foreign affiliates. In 2014, foreign firms sold $918.7 billion in services to U.S. residents through their majority-owned foreign affiliates located in the United States.10 The data for cross-border trade and for sales by majority-owned affiliates are not directly compatible due to differences in coverage and classification.11 Nevertheless, the data presented in Table 1 indicate that, in terms of magnitude, a large proportion of sales of services occur through the commercial presence of companies in foreign markets.

Table 1. Services Supplied to Foreign and U.S. Markets through

Cross-Border Trade and Affiliates, 2011-2015

(billions of dollars)

|

U.S. Exports |

U.S. Imports |

|||

|

Cross-Border Trade |

Through U.S.-owned Affiliates |

Cross-Border Trade |

Through Foreign-owned Affiliates |

|

|

2015 |

$750.9 |

$488.7 |

||

|

2014 |

$743.3 |

$1,503.4 |

$481.3 |

$918.7 |

|

2013 |

$701.5 |

$1,321.5 |

$461.1 |

$891.9 |

|

2012 |

$656.4 |

$1,285.9 |

$452.0 |

$813.3 |

|

2011 |

$627.8 |

$1,247.0 |

$435.8 |

$781.6 |

Source: Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, available at http://www.bea.gov. Foreign owned affiliate data lags by one year.

Although services contribute to the value of manufactured and agricultural products, conventional trade data, which are not on a value-added basis, do not attribute any portion of their traded value to services trade. Data measure exports and imports of goods based on the value of the final product (e.g., medical device or t-shirt). Included in that measurement, but not disaggregated, is the value of such services as research and development, design, transportation costs, and finance, among others, that are imbedded in the final product. However, the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the WTO have undertaken a project to measure trade flows based on value-added12 rather than final cost. They estimate that in 2009, close to 50% of the value of U.S. exports of manufactured goods was attributable to services inputs.13 This finding suggests a larger role for services in international trade than is reflected in conventional trade data, and is likely to grow in importance with the growth of global supply chains. An economist at Standard Chartered also argues that there are discrepancies in trade statistics, showing that by traditional measures services are 20% of global exports but, by his estimates of value-added, services account for 45%.14

Geographical Distribution

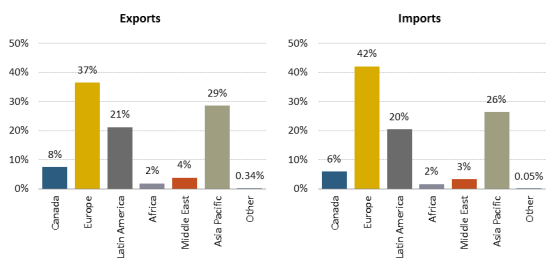

The United States conducts trade in services (both via cross border trade and FDI) with many different regions of the world (see Figure 2). Europe accounted for the majority of U.S. cross-border exports, with the United Kingdom (UK) alone accounting for 9% of U.S. services exports and 11% of services imports in 2015. Apart from the UK, 28% of U.S. exports of services went to the rest of Europe, while 31% of U.S. imports of services came from those countries. Canada accounted for 8% of U.S. services exports and 6% of U.S. services imports; China was 6% and 3% respectively, while other Asian and Pacific countries accounted for 22% of U.S. exports and 23% of imports of services in 2015. Japan's consumption of U.S. services was similar to that of China but Japan accounted for approximately double the amount of U.S. services imports.15

|

Figure 2. U.S. Services Cross-Border Trade by Geographic Region, 2015 (Percentage of Total) |

|

|

Source: CRS, based on data from the Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. |

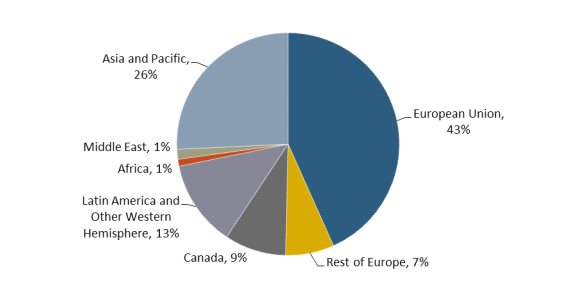

Europe's dominance in U.S. services trade is even more apparent when taking into account services that are provided through multinational corporations (MNCs) and their affiliates (see Figure 3). In 2014 (latest data available), 43% of services supplied by U.S. MNCs were to foreign persons located in European Union countries, 26% to foreign persons located in Asian countries, and 9% to foreign persons located in Canada. In 2014, 58% of sales of services to U.S. persons by U.S. affiliates of foreign-owned MNCs were by MNCs based in European countries; 24% by MNCs based in Asia, Middle East, and Africa; and 10% by MNCs based in Canada.16

|

Figure 3. U.S. Services Exports through Affiliates, 2013 (percentages of total) |

|

|

Source: CRS, based on data from the Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. |

Trade by Services Type

The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis divides services into nine categories:17

- Maintenance and repair services;

- Transport;

- Travel (for all purposes including tourism, education);

- Insurance services;

- Financial services;

- Charges for the use of intellectual property (IP) (e.g., trademarks, franchise fees);

- Telecommunications, computer, and information services;

- Other business services (e.g., research and development, accounting, engineering); and

- Government goods and services.

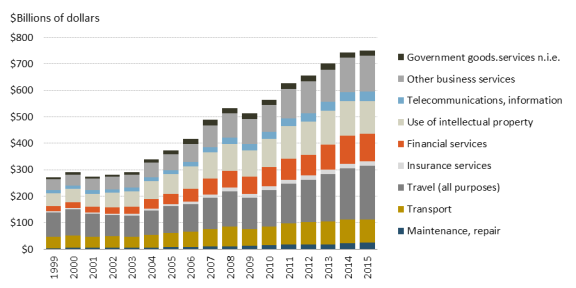

In 2015, U.S. exports covered a diverse range of services (see Figure 4). Travel accounted for the largest percent of cross-border U.S. exports at 27%. Royalties and fees generated from intellectual property as well as other business services contributed another 17% and 18% respectively. Transportation and financial services were 12% and 14% respectively of cross-border exports.18

|

|

Source: CRS, based on data from the Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. Notes: n.i.e. = not included elsewhere. |

Sales of services by MNCs via commercial presence (Mode 3) include a broader range of industries. In 2014 (latest data available), 25% of the value of services sold to foreign persons by U.S.-owned MNCs was from wholesale and retail trade services. Additionally, financial services accounted for 15% of the value; sales of professional services, including computer systems management and design, architectural, engineering, and other professional services for 16%; information-related services for 15%; and "other industries" (a category that includes mining, utilities, transportation, and other services) for 19%. Manufacturing accounted for the smallest share at 2%, followed by real estate at 4%.19

The total value of services supplied to U.S. persons by U.S. affiliates of foreign MNCs was less than two-thirds the size of the value of services supplied to foreign persons by U.S.-owned MNCs. The composition of the services supplied, though, was similar in both directions. In 2014, for sales of services to U.S. persons by U.S. affiliates of foreign MNCs, wholesale and retail trade accounted for 22%, and financial services providers for 20%. Another 22% was by providers from "other industries."20

|

Trade in ICT and Potentially ICT-Enabled Services In October 2016, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Statistics began to identify trade in Information and Communications Technology (ICT) and potentially ICT-enabled services, reflecting the growth and economic impact of digital trade and digitally-enabled services. ICT services include telecommunications and computer services as well as related charges for the use of intellectual property (e.g., licenses and rights). In addition, ICT-enabled services are those services with outputs delivered remotely over ICT networks such as online banking or education. For many types of services, however, the actual mode of delivery is not known (e.g., a consumer could go to a bank to conduct a transaction or do so online). As such, BEA tracks potentially ICT-enabled services which include a variety of services, including insurance and financial services, as well as many business services like research, architectural, and engineering services which could be delivered electronically. In 2015, exports of ICT services accounted for $65 billion of U.S. exports while potentially ICT-enabled services exports were another $399 billion, demonstrating the impact of the Internet and digital revolution. Together, ICT and potentially enabled ICT services were 62% of total U.S. service exports in 2015 (and 57% of U.S. service imports). (For more information, see Grimm, Alexis N., BEA, Trends in U.S. Trade in Information and Communications Technology (ICT) Services and in ICT-Enabled Services, May 2016, http://www.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2016/05%20May/0516_trends_%20in_us_trade_in_ict_serivces2.pdf). |

World Trade in Services

Globally, the OECD finds that services account for over two-thirds of global GDP and three-quarters of global FDI in advanced economies.21 The WTO recorded a 6% decline in the value of global services exports and attributes a large portion of the decline to changes in exchange rates, especially given the depreciation of the euro and pound as well as other currencies against the dollar.22 A decline in merchandise trade may also impact trade in services if fewer services are needed for tracking, transport, and supply chain management.

The United States is a major exporter and importer of services in global markets. According to the WTO, if the European Union (EU)23 countries are treated separately, the United States was the largest single-country exporter (14.5%) and importer (10.2%) of global commercial services in 2015 (see Table 2). The United States was the second-largest exporter (18.8%) and importer (12.9%) in 2015, if the EU is treated as a single entity (see Table 3).

|

Rank |

Exporter |

Value ($ bn) |

Share (%) |

Annual % Change |

Rank |

Importer |

Value ($ bn) |

Share (%) |

Annual % Change |

|

|

1 |

United States |

690 |

14.5 |

0 |

1 |

United States |

469 |

10.2 |

3 |

|

|

2 |

United Kingdom |

345 |

7.3 |

-5 |

2 |

China |

466 |

10.1 |

3 |

|

|

3 |

China |

285 |

6.0 |

2 |

3 |

Germany |

289 |

6.3 |

-12 |

|

|

4 |

Germany |

247 |

5.2 |

-9 |

4 |

France |

228 |

4.9 |

-9 |

|

|

5 |

France |

240 |

5.0 |

-13 |

5 |

United Kingdom |

208 |

4.5 |

-1 |

|

|

6 |

Netherlands |

178 |

3.7 |

-9 |

6 |

Japan |

174 |

3.8 |

-9 |

|

|

7 |

Japan |

158 |

3.3 |

0 |

7 |

Netherlands |

157 |

3.4 |

-9 |

|

|

8 |

India |

155 |

3.3 |

0 |

8 |

Ireland |

152 |

3.3 |

4 |

|

|

9 |

Singapore |

139 |

2.9 |

-7 |

9 |

Singapore |

143 |

3.1 |

-8 |

|

|

10 |

Ireland |

128 |

2.7 |

-5 |

10 |

India |

122 |

2.7 |

-4 |

Source: World Trade Organization, World Trade Statistical Review 2016, p. 96.

Note: Based on Balance of Payments data that may underestimate some items.

|

Rank |

Exporter |

Value |

Share (%) |

Annual % Change |

Rank |

Importer |

Value ($ bn) |

Share (%) |

Annual % Change |

|

|

1 |

Extra-EU(28) exports |

915 |

24.9 |

-9 |

1 |

Extra-EU(28) exports |

732 |

20.2 |

-7 |

|

|

2 |

United States |

690 |

18.8 |

0 |

2 |

United States |

469 |

12.9 |

3 |

|

|

3 |

China |

285 |

7.8 |

2 |

3 |

China |

466 |

12.9 |

3 |

|

|

4 |

Japan |

158 |

4.3 |

0 |

4 |

Japan |

174 |

4.8 |

-9 |

|

|

5 |

India |

155 |

4.2 |

0 |

5 |

Singapore |

143 |

3.9 |

-8 |

|

|

6 |

Singapore |

139 |

3.8 |

-7 |

6 |

India |

122 |

3.4 |

-4 |

|

|

7 |

Switzerland |

108 |

2.9 |

-7 |

7 |

Korea, Republic of |

112 |

3.1 |

-2 |

|

|

8 |

Hong Kong, China |

104 |

2.8 |

-2 |

8 |

Canada |

95 |

2.6 |

-11 |

|

|

9 |

Korea, Republic of |

97 |

2.6 |

-13 |

9 |

Switzerland |

92 |

2.5 |

-6 |

|

|

10 |

Canada |

76 |

2.1 |

-10 |

10 |

Russian Federation |

87 |

2.4 |

-27 |

Source: World Trade Organization, World Trade Statistical Review 2016, p. 97.

Note: Excludes Intra-EU trade.

Global Value Chains and Services

U.S. firms are using advances in information technology and expanding global value chains to bring goods and services to market. Today, more than half of global manufacturing imports are intermediate goods traveling within supply chains while over 75% of the world's services imports are intermediate services.24 Intermediate services embedded within a value chain include not only transportation and distribution to move goods along, but also research and development, design and engineering, as well as business services such as legal, accounting, or financial services. As manufacturing and agriculture grow more complex and technologically advanced, their consumption of services also grows.

With U.S. firms supplying many of the world's services, these findings imply that more U.S. services are traded internationally than traditional trade statistics indicate, and that many more service industry jobs in the United States are linked to international trade than traditionally thought. In addition, the disaggregation of value chains into smaller pieces, or modules, opens up domestic and international business opportunities to specialized firms or small or mid-sized enterprises (SMEs) who can focus on one piece. As such, the strategic and potential economic impact of both trade barriers and efforts to liberalize trade in services may be greater than many people realize. The growth of global value chains (GVCs) in which economic activities are fragmented across multiple countries and regions has heightened the interdependence and interconnectedness of economies. U.S. industries could potentially gain access to a wider marketplace for raw materials, less expensive labor, lower production costs, as well as talents and specializations from across the world. By creating global supply chains, businesses may increase productivity and efficiency, lower costs, and create new offerings for companies and consumers. Using global supply chains, however, entails potential costs and risks. Managing a complex supply chain across countries and/or time zones can be difficult and create additional costs. Some analysts point out that the benefits of increasingly interconnected supply chains may also be offset by potential costs associated with over-reliance on foreign or dispersed suppliers, or increased exposure or vulnerability to intellectual property rights theft or external shocks from abroad, such as environmental disaster (e.g., earthquake) or market disturbances (e.g., financial crash or truck driver strike).25

Global value chains have expanded and redefined the role that services play in international trade and are one reason for the growth in services. Furthermore, GVCs may also serve as a motivator for countries involved at any point along a global value chain to seek more open and level markets for moving intermediate goods and service imports and exports. According to one study, a domestically manufactured good contains over 20% of foreign value added in many countries, and over 50% in some countries and industries.26 Similarly, imported goods often contain a significant amount of domestic content. For example, a French wine imported into the United States may be transported by a U.S. express delivery service and use a label designed and printed by a U.S. marketing firm, while a gadget assembled domestically and exported by a U.S. firm may not only have components from abroad but also may rely on foreign research and engineering skills.

The WTO's "Made in the World" initiative finds that the increase use of GVCs has led industries to demand greater trade liberalization and lower protectionism as these firms depend on other links in the value chain, both domestic and foreign.27

Barriers to Trade in Services

Liberalizing trade for services can be more complex than for goods, as the impediments that service providers face are often different from those faced by goods suppliers. Many impediments in goods trade—tariffs and quotas, for example—are at the border.

By contrast, restrictions on services trade occur largely within the importing country, "behind the border" barriers. Some of these restrictions are in the form of government regulations. The right of governments to regulate service industries is widely recognized as prudent and necessary to protect consumers from harmful or unqualified providers. For example, doctors and other medical personnel must be licensed by government-appointed boards; lawyers, financial services providers, and many other professional service providers must be also certified in some manner. In addition, governments apply minimum capital requirements on banks to ensure their solvency. Each government can determine what it deems to be a prudent level of regulation. However, one concern in international trade is whether these regulations are applied to foreign service providers in a discriminatory and unnecessarily trade restrictive manner that limits market access. Because services transactions more often require direct contact between the consumer and provider than is the case with goods trade, many of the "trade barriers" that foreign companies face pertain to the establishment of a commercial presence in the consumers' country in the form of direct investment (Mode 3) or to the temporary movement of providers and consumers across borders (Modes 2 and 4).

The GATS under the WTO identifies specific "market access" restrictions as proscribed under its provisions. These include limits on the following: the number of foreign service suppliers, the total value of service transactions or assets, the number of transactions or value of output, the type of legal entity or joint venture through which services may be supplied, and the share of foreign capital or total value of foreign direct investment.

In many cases the impediments are government regulations or rules that are ostensibly legitimate but may intentionally or unintentionally discriminate against foreign providers and impede trade. Examples of such barriers include the following:

- restrictions on international payments, including repatriation of profits, mandatory currency conversions, and restrictions on current account transactions;

- requirements that foreign professionals pass certification exams or obtain extra training that is not required for local nationals;

- forced localization requirements;

- restrictions on data flows and information transfer imposed to protect data and maintain privacy or other localization requirements;

- "buy national" requirements in government procurement;

- lack of national treatment in taxation policy or protection from double taxation;

- government-owned monopoly service providers and requirements that foreign service providers use a monopoly's network access or communications connection providers;

- government subsidization of domestic service suppliers;

- discriminatory licensing and certification of foreign professional services providers;

- restrictions on the movement of personnel, including temporary business visa and work permit restrictions; and

- limitations on foreign direct investment, such as equity ceilings; restrictions on the form of investment and rights of establishment, that is, a branch, subsidiary, joint venture, etc.; and requirements that the chief executive officer or other high-level company officials be local nationals or that a certain proportion of a company's directors be local nationals.28

The Economic Effects of Barriers to Services Trade

As the most significant barriers to trade in services are not readily quantifiable, measuring their effects is challenging. Economists have constructed methods to at least estimate the effects, which can help to inform trade policy. However, these studies have limitations, are sensitive to the assumptions made, and may not necessarily reflect the entire range of factors influencing trade flows. Another consideration is that, as restrictions to trade are eliminated, cross-border trade via modes 1, 2, and 4 could grow at the expense of mode 3 if local presence is no longer a requirement to provide services in a particular country. However, removal of restrictions on foreign investment could offset any potential decline over the long term.29

Most economists argue that by reducing overall barriers to trade in services, economies can more efficiently allocate resources, increasing general economic welfare. Opponents of liberalization in trade in services argue, however, that the United States would be forced to relinquish some regulatory control that could affect the viability of service sectors.

Economists at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) published the results of one such method in several related studies. They first determined that U.S. trade in "business services"—a category that includes such activities as information, financial, scientific, and management services—is lower than one might expect given U.S. comparative advantage in those services. To come to this conclusion, the PIIE economists first determined that many business services are tradable, that is, capable of being sold from one region to another because many of them are "traded" between regions within the United States. Based on these assumptions, they compared the trade profiles of manufacturing firms and those of service firms and concluded that while about 27% of U.S. manufacturing firms export, only 5% of U.S. firms providing business services engage in exporting, even though the United States has a comparative advantage in business services. The PIIE study concludes that foreign government trade barriers are a major factor in the relatively low participation of U.S. service providers in trade. It also calculated the export/total sales ratios of manufacturing firms compared to business services firms, with the former being 0.20 and the latter 0.04. The study argues that if the ratio of business services could be raised to 0.1 or half of the manufacturers' ratio, it would increase total U.S. goods and services exports by 15%.30 Given that four-fifths of the U.S. private sector workforce is in services, a change in the ratio of exporting service businesses could have a significant impact.31 Presumably, U.S. imports of services would also increase.

Nontariff barriers for services specifically related to digital trade and data flows establish restrictions that may impact what a firm offers in a market or how it operates. For example, data transfer regulations that restrict cross-border data flows ("forced" localization barriers to trade), such as requiring locally based servers, may limit the type of financial transactions and services that a firm can sell in a given country (see text box below). Similarly, country-specific data regulations may create a disincentive for U.S. firms to invest in certain markets if a firm is hindered in its ability to export its own data from a foreign affiliate to a U.S.-based headquarters in order to aggregate and analyze information from across its global operations. The proponents of data localization seek to ensure privacy of citizens, security, and domestic control. Others point out that maintaining data within a country does not necessarily guarantee security or protect a country from exposure to foreign attacks.32 Opponents of localization restrictions on digital trade also point to lost efficiencies and increased costs of not allowing a free flow of information across borders. According to the U.S. International Trade Commission, based on 2014 estimates, decreasing barriers to cross -border data flows would increase GDP in the United States by 0.1% to 0.3%.33

|

Localization Requirements as Trade Barriers Localization requirements by other countries can create trade barriers to U.S. businesses, whether in developed or developing economies. For example, under a Canadian federal initiative to consolidate information technology services across 63 Canadian federal government email systems, the government prohibits the contracting company from allowing data to go outside of Canada based on a national security rationale. U.S. firms leveraging new technologies such as cloud-based services are therefore precluded from competing for the project. U.S. federal agencies may impose similar requirements. Also citing national security, China passed its cybersecurity law which requires companies that collect information on Chinese citizens to keep those data stored on domestic servers. Abiding by such laws creates a challenge for U.S. companies seeking to do business in the growing Chinese market.34 |

An Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) study on services trade restrictions analyzed the relationship between services trade restrictions, cross-border trade in services, and trade in downstream manufactured goods.35 The study finds that more restrictive countries not only import less in services but also export less, suggesting that restrictions also hurt the competitiveness of domestic industry. The negative effect of trade restrictions holds true across the various service sectors the researchers investigated. Financial services saw the greatest impact when restrictions changed; limitations on financial services were mostly in the form of market entry restrictions such as equity limits. Another OECD study finds that SMEs benefit relatively more compared to larger multinational firms from the reduction in market access barriers.36

According to the OECD Service Trade Restrictiveness Index (STRI),37 the United States has a relatively open and competitive business environment in comparison to the 40 countries included in the study, as foreign providers have access and are allowed to compete equally in most sectors in the United States. The United States scored as the most open country for sound recording, motion pictures, and distribution services, as reflected by the highly competitive U.S. industry in these sectors. On the other hand, the study identifies air transport, maritime transport, and courier services as the U.S. business sectors with the most restrictions impacting foreign firms seeking to do business in the country. The STRI can also show the impact of a country's reform efforts. For example, reforms by Indonesia in 2016 reduced its trade restrictiveness in particular sectors, including sound recording and air transport, compared to 2014.38

The United States has worked with trading partners to develop and implement rules on several fronts in order to reduce barriers and facilitate trade in services without infringing on the sovereign rights of governments to regulate services for prudential and sound regulatory reasons. The broadest and most challenging in terms of the number of countries involved are the multilateral rules contained in the GATS that entered into force in 1995 and are administered by the 161-member World Trade Organization (WTO). The United States has also sought to go beyond the GATS (WTO-plus) under more comprehensive rules in the free trade agreements (FTAs) it has in force and presumably in upcoming discussions on NAFTA. The Administration may also decide to continue services discussions in TiSA and T-TIP. The U.S. overall objective in each of these fora has been to establish a more open, rules-based trade regime that is flexible enough to increase the flow of services and to take into account the expansion of types of services, but clear enough to not impede the ability of governments to regulate the sectors.

One complication for the United States is that while trade negotiations are handled by the federal government, it is often the states that regulate services, including licensing and certification requirements. While regulations may vary across states, they all must comply with the commitments made by the federal government in international trade agreements.

The WTO and GATS

The seeds for multilateral negotiations in services trade were planted more than 40 years ago. In the Trade Act of 1974, Congress instructed the Administration to push for an agreement on trade in services under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) during the Tokyo Round negotiations. While the Tokyo Round concluded in 1979 without a services agreement, the industrialized countries, led by the United States, continued to press for its inclusion in later negotiations. Developing countries, whose service sectors are less advanced than those of the industrialized countries, were reluctant to have services included. Eventually services were included as part of the Uruguay Round negotiations launched in 1986.39 At the end of the round in 1993, countries agreed to a new set of rules for services, the GATS, and a new multilateral body, the WTO, to administer the GATS, the GATT, and the other agreements reached.

The GATS

The GATS provides the first and only multilateral framework of principles and rules for government policies and regulations affecting trade in services among the 161 WTO countries representing many levels of economic development. In so doing, it provides the foundation or floor on which rules in other agreements on services are based. As with the rest of the WTO, the GATS has remained a work in progress. The agreement is divided into six parts.40

Part I (Article I) defines the scope of the GATS. It provides that the GATS applies

- to all services, except those supplied in the routine exercise of government authority;

- to all government barriers to trade in services at all levels of government—national, regional, and local; and

- to all four modes of delivery of services.

Part II (Articles II-XV) presents the "principles and obligations," some of which mirror those contained in the GATT for trade in goods, while others are specific to services. They include

- unconditional most-favored-nation (MFN), nondiscriminatory treatment—services imported from one member country cannot be treated any less favorably than the services imported from another member country;41

- transparency—governments must publish rules and regulations;

- reasonable, impartial, and objective administration of government rules and regulations that apply to covered services;

- monopoly suppliers must act consistently with obligations under the GATS in covered services;

- a member incurring balance of payments difficulties may temporarily restrict trade in services covered by the agreement; and

- a member may circumvent GATS obligations for national security purposes.

Part III (Articles XVI-XVIII) of the GATS establishes market access and national treatment obligations for members. The GATS

- binds each member to its commitments once it has made them, that is, a member country may not impose less favorable treatment than what it has committed to;

- prohibits member-country governments from placing limits on suppliers of services from other member countries regarding the number of foreign service suppliers, the total value of service transactions or assets, the number of transactions or value of output, the type of legal entity or joint venture through which services may be supplied, and the share of foreign capital or total value of foreign direct investment;

- requires that member governments accord service suppliers from other member countries national treatment, that is, a foreign service or service provider may not be treated any less favorably than a domestic provider of the service; and

- allows members to negotiate further reductions in barriers to trade in services.

Importantly, unlike MFN treatment and the other principles listed in Part II, which apply to all service providers more or less unconditionally, the obligations under Part III are restricted. They apply only to those services and modes of delivery listed in each member's schedule of commitments. Thus, unless a member country has specifically committed to open its market to service suppliers in a particular service that is provided via one or more of the four modes of delivery, the national treatment and market access obligations do not apply. This is often referred to as the positive list approach to trade commitments. Each member country's schedule of commitments is contained in an annex to the GATS.42 The schedules of market access commitments are, in essence, the core of the GATS.

Parts IV-VI (Articles XIX-XXIX) are technical elements of the agreement. Among other things, they require that, no later than 2000, the GATS members start new negotiations (which they did) to expand coverage of the agreement and that conflicts between members involving implementation of the GATS are to be handled in the WTO's dispute settlement mechanism. The GATS also includes eight annexes, including one on MFN exemptions. Another annex provides a "prudential carve out," that is, a recognition that governments take "prudent" actions to protect investors or otherwise maintain the integrity of the national financial system. These prudent actions are allowed, even if they conflict with obligations under the GATS.

Not all of the issues in services were resolved when the Uruguay Round negotiations ended in 1994. Fifty-six WTO members, mostly developed economies, negotiated and concluded an agreement in 1997 in which they made commitments on financial services. The schedules of commitments largely reflected national regimes already in place.43 Furthermore, 69 WTO members negotiated and concluded an agreement in 1997 on telecommunications services. That agreement laid out principles on competition safeguards, interconnection policies, regulatory transparency, and the independence of regulatory agencies. Both agreements were added to the GATS as protocols.44 Today, a total of 108 WTO members have made some level of commitment to facilitate trade in telecommunications services.45

Services and the Doha Development Agenda (Doha Round)

Article XIX of the GATS required WTO members to begin a new set of negotiations on services in 2000 as part of the so-called WTO "built-in agenda" to complete what was unfinished during the Uruguay Round and to expand the coverage of the GATS to further liberalize trade in services. However, because no agreement was reached, the services negotiations were folded—along with agriculture and nonagriculture negotiations—into the agenda of the Doha Development Agenda (Doha Round) round that launched in December 2001.46

U.S. priorities in the services negotiations included the following areas:

- removing unnecessary restrictions on foreign providers establishing a commercial presence;

- improving the quality of commitments from what was established originally in the GATS;

- regulatory transparency so that foreign services providers are better informed about host country regulations that may affect them; and

- expanding market access in financial services, telecommunication services, express delivery, energy services, environmental services, distribution services, education and training services, professional services, computer and related services, and audiovisual and advertising services.

In general, the Doha Round negotiations were characterized by persistent differences among developed and developing countries on major issues in tariffs and nontariff barriers for goods, services, and agriculture. For example, developing countries (including emerging economic powerhouses such as China, Brazil, and India) sought the reduction of agriculture tariffs and subsidies among developed countries, nonreciprocal market access for manufacturing sectors, and protection for their services industries. In contrast, the United States, the EU, and other developed countries sought reciprocal trade liberalization, especially commercially meaningful access to advanced developing countries' industrial and services sectors, while attempting to retain some measure of protection for their agricultural sectors. The developed countries also sought to incorporate new issues that impact services, such as digital trade (data flows, cybertheft, and trade secrets) and global value chains.

The complexity of the services agenda and the number of players involved may have contributed to the lack of progress in the Doha Round negotiations. The term "services" includes a broad range of economic activities, many with few characteristics in common except that they are not goods. The trade barriers exporters face differ across service sectors, making the formulation of trade rules a significant challenge. For example, licensing regulations are especially important to professional service providers, such as lawyers and medical professionals, while data transfer regulations are important to financial services providers. Furthermore, services negotiations include many participants. In addition to trade ministers, they include representatives of finance ministries and regulatory agencies, many of whom do not consider trade liberalization a primary part of their mission. In addition, negotiators found it difficult to formulate mechanisms that distinguish between government regulations that are purely protectionist and those that have legitimate purposes.47

After 14 years, the divisions in the Doha Round called into question the viability of the "single undertaking" (one package to address all trade issues together) type of negotiation and some parties voiced a need for institutional reform. After the WTO's 2015 Ministerial was held in Nairobi, Kenya, the Ministerial Declaration acknowledged the division over the future of the Doha Round, and failed to reaffirm its continuation. Despite the disagreements, there was some progress in certain issues, such as the LDC Services Waiver to provide preferential treatment to least-developed countries (LDCs) for specific service sectors and modes.48

Frustration with the Doha Round negotiations has likely contributed to the proliferation of bilateral and regional trade agreements that include provisions on services and services-related activities (for example, foreign direct investment) and for alternative frameworks.

Services in U.S. FTAs

The United States has made services a priority in each of the 15 FTAs it has negotiated that cover trade with 20 countries (including the U.S.-Canada FTA, which was superseded by the entry into force of the North American Free Trade Agreement [NAFTA] on January 1, 1994). While the specific treatment of services differs among the FTAs because of the status of U.S. trade relations with the partner(s) involved and the evolution of issues involved, the FTAs share some characteristics that define a framework of U.S. policy priorities. Some of the major characteristics are examined below. Some of these aspects reaffirm adherence to principles embedded in the GATS, while others go beyond the GATS.

Negative List

Each U.S. FTA uses a negative list in determining market access and national treatment coverage and commitments from each partner. A negative list means that the FTA provisions for market access and national treatment apply to all categories and subcategories of services in all modes of delivery, unless a party to the agreement has listed a service or mode of delivery as an exception. The negative list also implies that a newly created or domestically provided service is automatically covered under the FTA unless it is specifically listed as an exception in an annex to the agreement. The negative list approach is widely considered to be more comprehensive and flexible than the positive list, which is used in the GATS and which some other countries use in their bilateral and regional FTAs.

Rules of Origin

Under FTAs in which the United States is a party, any service provider is eligible irrespective of ownership nationality as long as that provider is an enterprise organized under the laws of either the United States or the other party(ies) or is a branch conducting business in the territory of a party. Such criteria potentially expand the benefits of the FTA to service providers from other countries that are not direct parties to the FTA. For example, a U.S. subsidiary of a Canadian-owned insurance company would be covered by the U.S.-South Korea FTA. The FTAs do allow one party to deny benefits to a provider located in the territory of another party, if that provider is owned or controlled by a person from a nonparty country and does not conduct substantial business in the territory of the other party, or if the party denying the benefits does not otherwise conduct normal economic relations with the nonparty country.49

Multiple Chapters on Services

In many U.S. FTAs, trade in services spans several chapters, indicating its prominence in U.S. trade policy, the complexity in addressing services trade barriers, and the specificity of U.S. trade policy negotiating objectives. Each FTA has a specific chapter on cross-border trade in services—trade by all modes except commercial presence (Mode 3). This chapter requires the United States and the FTA partner(s) to accord nondiscriminatory treatment—both MFN treatment and national treatment—to services originating in each other's territory. The agreement prohibits the FTA partner-governments from imposing restrictions on the number of service providers, the total value of service transactions that can be provided, the total number of service operations or the total quantity of services output, or the total number of natural persons that can be employed in a services operation. In addition, the governments cannot require a service provider from the other FTA partner to have a presence in its territory in order to provide services. The FTA partners may exclude categories or subcategories of services from the agreement, which they designate in annexes.

Each U.S. FTA also contains a chapter on foreign direct investment, including service providers that have a commercial presence (Mode 3) in the territory of an FTA partner and a chapter on intellectual property rights (IPR), which is also relevant to services trade.50 In addition, many U.S. FTAs contain separate provisions or chapters on specific service categories which have been priority areas in U.S. trade policy. They include the following:

- Financial Services: The FTAs define financial services to "include all insurance and insurance-related services, and all banking and other financial services, as well as services incidental or auxiliary to a service of a financial nature." Among other things, the financial services chapter allows governments to apply restrictions for prudential reasons and allows financial service providers from an FTA partner to sell a new financial service without additional legislative authority, if local service providers are allowed to provide the same service.

- Telecommunication Services: The United States and trading partners agree that enterprises from each other's territory are to have nondiscriminatory access to public telecommunications services. For example, both countries will ensure that domestic suppliers of telecommunications services who dominate the market do not engage in anticompetitive practices. They also ensure that public telecommunications suppliers provide enterprises based in the territory of the FTA partner with interconnection, number portability, dialing parity, and access to underwater cable systems.

- e-commerce/Digital Trade: The FTAs include provisions to ensure that electronically supplied services are treated no less favorably than services supplied by other modes of delivery and that customs duties are not to be applied to digital products whether they are conveyed electronically or via a tangible medium such as a disk. Recent and ongoing trade negotiations seek to ensure open digital trade by prohibiting "forced" localization or other requirements that limit cross-border flows.51

Regulatory Transparency

Many U.S. FTAs require FTA partners to practice transparency when implementing and developing domestic regulations that affect services. In particular, the FTAs require the partner countries to provide notice of impending investigations that might affect service providers from the other partner(s). The FTAs go beyond the transparency provisions in the GATS by providing mechanisms for interested parties to comment on proposed regulations and appeal adverse decisions.

Regulatory Heterogeneity

In addition to market access restrictions, firms operating in multiple countries or having a global supply chain may be subject to an array of local regulations that vary in each market, and impact the services that firms can access or sell. This regulatory heterogeneity, while neither discriminatory nor anticompetitive, may increase operational costs and thereby limit a firm's ability to do business in a foreign market. For example, regulatory heterogeneity can limit the access of professional service providers (e.g., architects, doctors, etc.) whose licenses or certifications may not be recognized in foreign markets. Regulatory cooperation, such as when countries or regions harmonize to common standards or establish mutual recognition, can help minimize the impact of the differing regulatory regimes.52 Regulatory cooperation to ease trade in services may occur outside or within the context of trade agreement negotiations. Regulatory cooperation in financial services under the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision that drafted BASEL III53 and U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) efforts toward recognition of the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) for accounting standards54 are examples of international regulatory cooperation happening outside of FTA negotiations. The U.S.-South Korea FTA is one example of using FTA negotiations to address differing regulatory regimes for services.

|

A Recent Case Study: The U.S.-South Korea FTA (KORUS FTA)55 On March 15, 2012, the U.S.-South Korean FTA (KORUS FTA) entered into force. Industry representatives referred to the services-related provisions of the agreement as "the gold standard" for the treatment of services in FTAs. However, concerns have been raised regarding implementation and the effectiveness of the agreement's provisions. Examining some of the KORUS provisions may provide an indication of trends for U.S. objectives and issues in trade in services in current services trade negotiations. The United States sought transparency provisions to ensure transparency into the South Korean trading and regulatory systems. Under KORUS, each side agreed to publish relevant regulations and administrative decisions as well as proposed regulations; allow persons from the other party to make comments and ask questions regarding proposed regulations; notify such persons of administrative proceedings and allow them to make presentations before final administrative action is taken; and allow such persons to request review and appeal of administrative decisions. For the first time in any trade agreement, KORUS contains in the financial services annex a specific reference to data transfer, enabling U.S. companies to freely transfer customer data into and out of a partner country. Data transfer has become a significant U.S. objective in current trade agreement negotiations as globalization has fragmented business operations across borders and multinational firms want to be able to maintain central locations for data storage and avoid having to locate servers in multiple locations. In doing so, the multinational companies confront some governments' privacy concerns and localization requirements. Under KORUS, the United States worked with South Korea to revise the latter's vague guidelines, strict rules, and lengthy application process after U.S. stakeholders raised concerns about South Korea's implementation of commitments to allow data transfers. The role of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in services trade is another U.S. trade policy issue addressed in KORUS, making it a possible model for other U.S. FTAs.56 Under KORUS, South Korea agreed that those entities will be subject to an independent state regulator as opposed to being self-regulated. In telecommunications services, South Korea agreed to reduce government restrictions on foreign ownership of South Korean telecommunications companies. The United States sought greater reciprocity and market openness in the treatment of professional services. The United States and South Korea agreed to form a professional services working group to develop methods to recognize mutual standards and criteria for the licensing of professional service providers. Legal services represent one area where there have been implementation challenges. While specific commitments were made to open up the legal services market over three stages, the United States voiced concern about recent legislation that could limit the benefits expected under KORUS. In addition to its KORUS commitments, South Korea has also committed to opening up its legal services market to foreign law firms in its free trade agreements with the EU, the UK, Australia, and Canada. |

Services in the Current Trade Promotion Authority

The Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) legislation signed into law on June 29, 2015,57 contained specific provisions establishing U.S. trade negotiating objectives on services trade (P.L. 114-26). The text broadly states that "[t]he principal negotiating objective of the United States regarding trade in services is to expand competitive market opportunities for the United States." Congress also specifically pointed to the utilization of global value chains and supported pursuing the objectives of reducing or eliminating trade barriers through "all means, including through a plurilateral agreement" with partners able to meet high standards.

Congress provided objectives specific to "digital trade in goods and services and cross-border data flows," instructing the President to ensure that cross-border data flows and electronically delivered goods and services have the same level of coverage and protection as those in physical form, and are not impeded by regulation, excepting for legitimate objectives. Congress recognized the challenges presented by localization regulations, and sought to ensure that trade agreements eliminate and prevent measures requiring the locating of "facilities, intellectual property, or other assets in a country."

Services negotiation likely will take place in the upcoming renegotiation of NAFTA based on the provisions of trade promotion authority (TPA). Services discussions related to TiSA, TPP, and T-TIP (see below) took place during the Obama Administration. While President Trump withdrew U.S. participation in the TPP, the future of TiSA and T-TIP is uncertain. Congress may review potential results of NAFTA and possibly other agreements against the negotiation objectives set in TPA if and when it considers legislation necessary to implement the agreements.

The Potential Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA)

Largely because of the lack of progress in the Doha Round of negotiations in the WTO, a group of 23 WTO members—including the United States—is engaged in discussions on a possible sector-specific, plurilateral agreement to liberalize trade in services among them.58 The group accounts for around 70% of world trade in services.59 Negotiations on a proposed Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) were launched in April 2013. The United States and Australia have been at the forefront of the TiSA negotiations, with other WTO members, including some developing countries, becoming increasingly active as the discussions progress.

While not directly linked currently to the WTO, TiSA participants are taking as their guide the "Elements of Political Guidance" issued at the end of the 8th WTO ministerial in December 2011. It stipulated that members could pursue negotiations outside of the single undertaking in order to accomplish the objectives of the Doha Round.60

For proponents of services trade liberalization, the plurilateral approach offers some advantages:

- progress in the services negotiations would no longer be tied to progress in other negotiations as has been in the case under the "single-undertaking" rule in the Doha Round;

- participating members include those countries that account for the majority of global services trade;

- since negotiations are confined to countries willing to negotiate, prospects for a successful conclusion may be enhanced;

- coverage of the agreement can be expanded as countries accede to its provisions; and

- negotiating members are likely to be more willing to commit to reducing barriers to trade and services beyond the limited commitments under the GATS and the offers made during the Doha Round.

However, critics highlight possible drawbacks to the approach:

- TiSA participants do not as a group currently include some of the economically significant emerging economies, such as Brazil, India, and China, which present larger potential market opportunities for services but also impose significant impediments to trade and investment in services;

- breaking from the single-undertaking framework could undermine the opportunity for concessions in other areas, including agriculture and manufactured goods, that result from the "give-and-take" of broader negotiations; and

- a plurilateral services pact might diminish the credibility of the multilateral trade negotiation framework at a time when its credibility has already been weakened by the stalled Doha Round.

The participants agreed to a framework of five basic objectives on which the negotiations are to be conducted.61 The agreement should

(1) be compatible with the GATS to attract broad participation and possibly be brought within the WTO framework in the future;

(2) be comprehensive in scope, with no exclusions of any sector or mode of supply;

(3) include commitments that correspond as closely as possible to applied practices and provide opportunities for improved market access;

(4) include new and enhanced disciplines to be developed on the basis of proposals brought forward by participants during the negotiations; and

(5) be open to new participants who share the objectives but also should take into account the development objectives of least developed countries (LDCs).

Participants needed to decide whether to schedule trade liberalization commitments according to a negative list or a positive list. As noted earlier, under a negative list, the FTA provisions apply to all categories and subcategories of services in all modes of delivery, unless a party to the agreement has listed a service or mode of delivery as an exception. In contrast, under a positive list, each party must specifically opt in for a service to be covered. The United States typically prefers the more comprehensive and flexible negative list approach. Because of disagreements within the group, and to be compatible with GATS, TiSA negotiating parties decided to use a "hybrid" approach: market access obligations are being negotiated under a positive list, while national treatment obligations are being negotiated under a negative list.62

Another issue was the application of the TiSA commitments to nonparticipants. The participants agreed to conduct the negotiations on a non-MFN basis, that is, the benefits of the commitments made by the participants in the TiSA would apply to only those countries that have signed on to the agreement, thereby avoiding "free-riders." This exception to the general WTO MFN principle is consistent with Article V of the GATS, which allows WTO members to form preferential agreements to liberalize trade in services as long as the agreement has substantial service sectoral coverage and provides for the absence or elimination of substantially all discrimination between or among the parties.

Many members of the U.S. business community, especially service providers and related industries, strongly support the formation of TiSA. They view the agreement as an opportunity to strengthen rules and achieve greater market access on trade in services beyond what are contained in the GATS—which are largely considered to be weak.

Some opponents of trade-in-services liberalization, such as labor unions and some civil society groups, argue that, rather than employing TiSA as a means to expand on the GATS, it should be used to reverse what they consider to be infringements of GATS provisions on the authority of national, state, and local governments to regulate services.

Since negotiations launched in April 2013, 21 rounds of TiSA negotiations and intercessional meetings occurred in an effort to make further progress. The agreement, whose status is unknown, would likely include a core text, as well as sections on transparency, movement of natural persons, domestic regulation, and government procurement. The current text is said to contain sectoral annexes for air transport, e-commerce, maritime transport, telecommunications, and financial services. As many of these topics and sectors may be sensitive or controversial among and within some of the negotiating parties, the final structure of TiSA is not yet decided.

One area of contention is whether "new services" would be included under the nondiscrimination obligations. While the United States supports the inclusion of all yet-to-be-defined services, the EU has stated that it wants to preserve so-called policy space in that area and exempt all new services.63 The e-commerce annex reportedly covers cross-border data flows, consumer online protection, interoperability, and international regulatory cooperation, among other provisions.64 To date, however, the EU has not engaged in discussions on data flows, creating an obstacle in the negotiations. As financial services may not be covered by the e-commerce provisions, the United States separately proposed a ban on data localization for financial services that the parties continue to discuss.65

For professional services, current negotiations do not include explicit mutual recognition agreements, but rather discussion aims to recognition of foreign professionals and expedite licensing procedures.

One issue that has emerged is China's interest in joining the TiSA negotiations. While the issue is still pending, it has generated differences among the participants. Reportedly, the United States had expressed concerns about China's readiness to undertake the commitments that TiSA would require, given China's limited implementation of other agreements to date; the EU had argued for China's participation sooner.66 The United States and a subset of the other participants were to review China's level of compliance with and implementation of other trade agreements. To date, no other large emerging market has expressed interest in joining TiSA. However, the agreement overall is reportedly being structured so that it can be "multi-lateralized" in the future and incorporated into the GATS and made applicable to all WTO members.67 The chances or timeline of such an event are uncertain, as the TiSA itself remains uncertain. The Trump Administration has not stated an official position on the continuation of TiSA negotiations, but USTR Robert Lighthizer indicated that the Trump Administration may support its continuation.68

TiSA arguably has been a significant focal point of trade policy on services for the United States and other major trade powers. If successful, it could form the basis of multilateral rules on trade in services for the 21st century.69 The United States is engaged with other trade dialogues, including the renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the potential Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP), in which trade in services is playing an important role and where U.S. objectives could complement as well as overlap with U.S. objectives in the TiSA.

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)

On May 18, 2017, the Trump Administration sent a 90-day notification to Congress of its intent to begin talks with Canada and Mexico to renegotiate NAFTA.70 Since its entry into force on January 1, 1994, NAFTA largely has been responsible for the economic integration of the North America continent as well as the creation of a more competitive North American marketplace. Today, North American countries rely on services trade to move and track products across borders multiple times before a finished product is ready for its final sale.

The original NAFTA includes chapters on cross-border trade in services, telecommunications, and financial services, as well as temporary entry for business persons.71 Unlike TiSA, the NAFTA employs the "negative list approach" for liberalization of cross-border trade in services so that the provisions apply to all types of services unless specifically excluded by a partner country as a reservation or nonconforming measure (NCM) listed in the agreement's Annexes. The negative list approach implies that any new type of service that is developed after the agreement enters into force is automatically covered unless it is specifically excluded.

The Trump Administration aims to "modernize" NAFTA through renegotiation by updating the provisions in multiple areas, including services and digital trade, two areas that were not comprehensively addressed by NAFTA. Many U.S. stakeholders see a NAFTA renegotiation as an opportunity to obtain greater market access into Canada and Mexico, regulatory harmonization across the three markets, and improved regional trade facilitation. However, Canada and Mexico also have goals to further open U.S. markets, and stakeholders in each country voice concerns that any renegotiation could potentially disrupt existing regional supply chains.72

Some, including Members of Congress, have suggested that the provisions of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) could serve as a starting point for NAFTA negotiations, as both Canada and Mexico were involved in TPP negotiations. The TPP was a proposed FTA among 12 Asia-Pacific countries, including the United States, to reduce and eliminate tariff and nontariff barriers on goods, services, and agriculture, and establish trade rules and disciplines that expand on existing WTO commitments and address new issues.73 Similar to other U.S. FTAs, due to the complexity of services trade barriers, TPP addressed services in multiple chapters, including Cross Border Trade in Services, Financial Services, Temporary Entry, Telecommunications, and Electronic Commerce. Updates to NAFTA could draw on the TPP chapters.

On January 30, 2017, the United States gave notice to the other TPP signatories that it does not intend to ratify the agreement, effectively ending the U.S. ratification process and TPP's potential entry into force, unless the Administration changes its position. The 11 remaining TPP countries—Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam—continue to discuss how and if the TPP can come into force without the United States.74

The Potential Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP)

Given the importance of services in the U.S. and EU economic relationship, the potential T-TIP could include provisions to address barriers in transatlantic trade in services. The general structure of the T-TIP agreement, including its services component, remains uncertain as the negotiations are currently on hold. One source of debate in the T-TIP negotiations is the treatment of financial services. The United States advocated including market access for financial services in T-TIP. However, the United States is currently opposed to discussing financial regulation, unlike the EU, which seeks to include both financial services market access and regulatory cooperation in T-TIP, viewing the two as connected. According to some observers, U.S. opposition is due to concern over the potential impact to ongoing implementation of financial services regulation under the Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (frequently referred to as Dodd-Frank, P.L. 111-203). The United States is said to prefer handling regulatory cooperation through ongoing bilateral dialogues with the EU or through multilateral fora such as the G-20.75

Both U.S. and EU negotiators have stated that their services offers under T-TIP would go beyond the commitments being discussed in TiSA ("TiSA-plus").76 Though the U.S. proposal is not public, the services provisions in KORUS are a likely starting point (see text box on KORUS FTA). According to the former U.S. Trade Representative, the United States sought to "obtain improved market access in the EU on a comprehensive basis" and also "reinforce transparency, impartiality, and due process."77 While the United States used a negative list approach in its FTA with South Korea, the EU used a positive list approach with the FTA it signed with South Korea that went into effect in 2010, which may lead T-TIP negotiators to adopt a hybrid approach similar to that being employed in TiSA negotiations.78

With the 10th round of T-TIP negotiation, held in July 2015, the EU published its initial textual proposal on services, investment, and e-commerce.79 The proposal is based on a positive list of commitments so that sectors not specified would not be covered by the agreement; the EU offer did cover computer and telecommunications services, international maritime and air transport, and postal and courier services, as well as business and professional services. In addition to "carving out" public services, such as public health, education, social services, and water, the EU's proposal excludes audiovisual services under a "cultural exception,"80 conforming to the limitations included in its original mandate to negotiate the T-TIP passed by the European Commission.81

Unlike in TiSA, the EU proposal addresses worker mobility with a draft framework for mutual recognition of professional qualifications. Just as a mutual recognition agreement would cover the licensing requirements of all 50 states, it would cover those of all EU member states regardless of diversity among the member states' own regulations.

While electronic commerce is included in the EU proposal, it specifically excludes data flows and online consumer protection. U.S.-EU cross-border data flows are the highest in the world and, in 2012, U.S. exports of digitally deliverable services to the EU were $140.6 billion while imports were $86.3 billion.82 The absence of these sensitive areas from the EU proposal has disappointed some in the U.S. business community.83 The EU-U.S. Privacy Shield agreement84 could help facilitate further discussions in T-TIP on data protection, as the agreement facilitates cross-border data flows between the United States and EU, though it faces challenges in court.85

As stated, T-TIP negotiations are on hold as the Trump Administration has not stated if and when they will resume.

Outlook

To date, the record on liberalization of trade in services through reciprocal trade agreements is mixed. The 164 members of the WTO negotiated and have maintained a basic set of multilateral rules in the form of the GATS. However, the GATS is largely viewed as limited in scope, predating significant technological developments over the past two decades, and in need of expansion if it is to be an effective instrument of trade liberalization. The efforts of the WTO members to expand on these rules have stalled, with little prospect of success at least in the foreseeable future. The lack of progress in the WTO Doha Round negotiations due to the complexity of the issues and parties involved has led to the rise of sector-specific plurilateral agreements as an alternative path forward. In negotiating TiSA, the United States has been pursuing a services-specific plurilateral agreement that includes the 28-member EU and Japan—two of the most important U.S. trade partners—plus other participating countries.

The United States has made services trade liberalization and rules-setting an important component of the FTAs it has negotiated over the past two decades. While these agreements have gone beyond the GATS in terms of coverage, they apply to a limited number of countries, accounting for small shares of U.S. trade in services.

Issues for Congress

The outlook for the ongoing negotiations remains uncertain, as participants in each negotiation deal with difficult and complex issues. Potential policy issues for Congress and negotiators to address include the following:

- To what extent are U.S. positions on trade in services in the renegotiation of NAFTA, and TiSA and T-TIP if resumed, consistent with U.S. trade negotiating objectives on services as defined in the TPA legislation? How might Congress work with the Administration in relation to these pending negotiations?

- What are the prospects for concluding each of these trade agreements with comprehensive and high-standard commitments on services? How could the conclusion of one agreement impact negotiations in the others? What impact would these proposed agreements have on the U.S. economy and various stakeholders?

- Should Congress conduct hearings to examine potential new bilateral FTA negotiations with specific countries, such as other TPP members?

- Could the pursuit of bilateral, regional, and plurilateral agreements undermine the pursuit of broader multilateral rules in the GATS or would it encourage future multilateral action? Would the United States be able to set common rules across sufficient bilateral and plurilateral agreements to cover services trade across its major partners without major discrepancies?

- The United States has negotiated a number of FTAs with substantial services components. Might Congress direct USTR to use these FTAs to build a model services agreement that identifies U.S. interests across services?

- Advancements in information technology expand the number and types of services that can be traded and help to create new types of services. Is it possible to develop a trade arrangement that is clear enough to be effective and flexible enough to take into account rapid changes in the services sector?