Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) Negotiations: Overview and Issues for Congress

Congress has broad interest in trade in services, which are a large and growing component of the U.S. economy. It also has a direct interest in establishing trade negotiating objectives and potential consideration of a future Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA). Services account for 78% of U.S. private sector gross domestic product (GDP), 82% of private sector employees in 2015, and an increasing portion of U.S. international trade. “Services” refer to a growing range of economic activities, such as audiovisual, construction, and computer and related services; energy; express delivery; e-commerce; financial, legal, and accounting services; retail and wholesaling; transportation; telecommunications; and travel. Services include end-use products, such as legal services and financial products. Many services, such as distribution or transportation services, also facilitate other parts of the economy, helping goods move through global supply chains.

To open foreign markets to U.S. businesses and address trade barriers to services, which may be in the form of government regulations, the United States has engaged in multiple trade agreement negotiations. The World Trade Organization (WTO) General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) provides the foundation or floor on which rules in other agreements on services are based, including in U.S. free trade agreements (FTAs). Trade in services is addressed in U.S. bilateral and regional FTAs, including the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), concluded in October 2015. However, ongoing negotiation efforts to update GATS are stalled, even as technology and services trade have evolved significantly since GATS went into effect in 1995. To address these issues, 23 parties are engaged in discussions on a potential sector-specific, plurilateral agreement to further liberalize trade in services.

Negotiations on a proposed Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) were launched in April 2013, with the United States and Australia initially at the lead. TiSA participants account for about 70% of world trade in services and include the European Union, in addition to the United States and Australia. Some key major emerging markets, including Brazil, China, and India, are not currently parties to the TiSA negotiations, though China has indicated an interest in joining. While TiSA negotiations are occurring outside of the WTO, the agreement is reportedly being structured so that it can be potentially “multi-lateralized” in the future and incorporated into the GATS, making it applicable to all WTO members.

The final structure and sectors to be covered in TiSA remain under negotiation, but some key issues have emerged. For the United States, significant interests include expanding market access beyond the current GATS commitments, building disciplines on transparency, setting common rules for cross-border data flows and digital trade, and ensuring fair competition with state-owned enterprises. TiSA participants have conducted 21 negotiating rounds through 2016, and aim to complete negotiations in 2017 but no new rounds are scheduled. The outlook and timeline for the ongoing TiSA negotiations remains uncertain, as participants are tackling difficult and complex issues such as regulatory processes and digital trade frameworks. The new U.S. administration position on TiSA is unclear.

TiSA is one of several trade agreements that may be considered by Congress in the near future. Congress passed, and the President signed into law, Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) legislation in June 2015 which expires on July 1, 2018, with a possible extension to July 1, 2021. As part of TPA, Congress established principal trade negotiating objectives for services. If agreement on TiSA is reached while TPA is in effect, and if certain statutory requirements are met, TPA would provide for expedited legislative consideration of legislation to implement a final TiSA. Congress may opt to exercise oversight on the progress of the ongoing TiSA negotiations and consider a number of related factors such as comparisons with other agreements.

Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) Negotiations: Overview and Issues for Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Trade in Services Background

- Services in U.S. Trade Agreements

- WTO General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS)

- Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) Negotiations

- Key Provisions and Negotiating Issues

- Disciplines and Rules

- Market Access

- Sectoral Annexes

- Institutional Provisions

- Potential Areas of Controversy

- Current Outlook

- Issues for Congress

Summary

Congress has broad interest in trade in services, which are a large and growing component of the U.S. economy. It also has a direct interest in establishing trade negotiating objectives and potential consideration of a future Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA). Services account for 78% of U.S. private sector gross domestic product (GDP), 82% of private sector employees in 2015, and an increasing portion of U.S. international trade. "Services" refer to a growing range of economic activities, such as audiovisual, construction, and computer and related services; energy; express delivery; e-commerce; financial, legal, and accounting services; retail and wholesaling; transportation; telecommunications; and travel. Services include end-use products, such as legal services and financial products. Many services, such as distribution or transportation services, also facilitate other parts of the economy, helping goods move through global supply chains.

To open foreign markets to U.S. businesses and address trade barriers to services, which may be in the form of government regulations, the United States has engaged in multiple trade agreement negotiations. The World Trade Organization (WTO) General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) provides the foundation or floor on which rules in other agreements on services are based, including in U.S. free trade agreements (FTAs). Trade in services is addressed in U.S. bilateral and regional FTAs, including the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), concluded in October 2015. However, ongoing negotiation efforts to update GATS are stalled, even as technology and services trade have evolved significantly since GATS went into effect in 1995. To address these issues, 23 parties are engaged in discussions on a potential sector-specific, plurilateral agreement to further liberalize trade in services.

Negotiations on a proposed Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) were launched in April 2013, with the United States and Australia initially at the lead. TiSA participants account for about 70% of world trade in services and include the European Union, in addition to the United States and Australia. Some key major emerging markets, including Brazil, China, and India, are not currently parties to the TiSA negotiations, though China has indicated an interest in joining. While TiSA negotiations are occurring outside of the WTO, the agreement is reportedly being structured so that it can be potentially "multi-lateralized" in the future and incorporated into the GATS, making it applicable to all WTO members.

The final structure and sectors to be covered in TiSA remain under negotiation, but some key issues have emerged. For the United States, significant interests include expanding market access beyond the current GATS commitments, building disciplines on transparency, setting common rules for cross-border data flows and digital trade, and ensuring fair competition with state-owned enterprises. TiSA participants have conducted 21 negotiating rounds through 2016, and aim to complete negotiations in 2017 but no new rounds are scheduled. The outlook and timeline for the ongoing TiSA negotiations remains uncertain, as participants are tackling difficult and complex issues such as regulatory processes and digital trade frameworks. The new U.S. administration position on TiSA is unclear.

TiSA is one of several trade agreements that may be considered by Congress in the near future. Congress passed, and the President signed into law, Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) legislation in June 2015 which expires on July 1, 2018, with a possible extension to July 1, 2021. As part of TPA, Congress established principal trade negotiating objectives for services. If agreement on TiSA is reached while TPA is in effect, and if certain statutory requirements are met, TPA would provide for expedited legislative consideration of legislation to implement a final TiSA. Congress may opt to exercise oversight on the progress of the ongoing TiSA negotiations and consider a number of related factors such as comparisons with other agreements.

Introduction

"Services" refers to a range of economic activities that involve the sale and delivery of an intangible product, such as audiovisual, construction, and computer and related services; energy; express delivery; e-commerce; financial, accounting, and legal services; retail and wholesaling; transportation; telecommunications; and travel. For many countries, including the United States, trade in services is a large and growing component of their overall trade. The 1995 World Trade Organization (WTO) General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), and subsequent annexes, established basic rules for global trade in services. The purpose of the ongoing Trade in Services (TiSA) negotiations is to build on those rules by further increasing liberalization among the 23 negotiating parties, including the United States and European Union (EU), to open markets to foreign service providers and enhance rules governing services trade.

Congress has interest in the TiSA negotiations, as services accounted for $750.9 billion (33%) of U.S. exports in 2015.1 Congress also has a direct role in overseeing the ongoing TiSA negotiations, including in the context of the U.S. trade negotiating objectives on services it set under the Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) legislation passed in June 2015 (P.L. 114-26). If TiSA is concluded, Congress would face legislation to approve and implement U.S. commitments under TiSA.

This report provides a brief overview of U.S. trade in services, background on services in U.S. trade agreements, and an in-depth discussion of the ongoing TiSA negotiations. For more information on trade in services, please see CRS Report R43291, U.S. Trade in Services: Trends and Policy Issues, by Rachel F. Fefer. For an executive-level summary of the TiSA negotiations, please see CRS In Focus IF10311, Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) Negotiations, by Rachel F. Fefer.

Trade in Services Background

The United States is a global leader in services and the service sector is an important part of the overall U.S. economy. Services accounted for 78% of U.S. private sector gross domestic product (GDP)2 and for 91.8 million (82%) private sector employees in 2015.3

Services encompass a broad range of economic participants and activities from express delivery to education and digital trade. Services not only function as end-use products but are often referred to as the "lifeblood" of the rest of the economy, facilitating goods and enhancing productivity and overall competitiveness of an economy.

Global value chains, where different stages of production are located in different countries, are redefining the role that services play in international trade. Today, more than half of global manufacturing imports are intermediate goods traveling within supply chains, while over 70% of the world's services imports are intermediate services.4 Intermediate services embedded within a value chain include, for example, transportation, logistics, and distribution to move goods along; research and development to invent new products; telecommunications to open e-commerce channels; business services such as legal, accounting, marketing or human resources; and financial services to provide credits for the manufacture and consumption of goods.

Compared to goods, the basic characteristics of services are complex. Services are intangible and can be conveyed in various formats, including electronically and direct provider-to-consumer contact. To address this complexity, members of the WTO have adopted a system of classifying four modes of delivery for services to measure trade in services (see the text box below). These modes are also used to classify government policies that affect trade in services in international agreements.

|

Classifying Different Types of Services: Four Modes of Services Delivery5 International agreements on trade in services, including the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), which is administered by the WTO, identify four modes of supply of services: Mode 1—Cross-border supply: The service is supplied from one country to another. The supplier and consumer remain in their respective countries, while the service crosses the border. Example: A U.S. architectural firm is hired by a client in Mexico to design a building. The U.S. firm does the design in its home country and sends the blueprints to its client in Mexico. Mode 2—Consumption abroad: The consumer physically travels to another country to obtain the service. Example: A European client travels to the United States to attend training on architecture and stays in a U.S. hotel. Mode 3—Commercial presence: The supply of a service by a firm in one country via its branch, agency, or wholly-owned subsidiary located in another country. Example: A U.S. construction firm establishes a subsidiary in China to sell services to local clients. Mode 4—Temporary presence of natural persons: Individual suppliers travel temporarily to another country to supply services. Example: A U.S. computer programmer travels to Canada to provide training to an employee. Source: World Trade Organization, Guide to reading the GATS schedules of specific commitments and the list of article II (most-favored-nation [MFN])) exemptions. |

Distinguishing among the various modes of delivery of services is important for analyzing and measuring the volume of services trade, and because the different modes of delivery can raise different policy issues. There are two distinct categories for measuring trade in services: cross-border trade and services supplied through affiliates.

Cross-border services trade data measures U.S. exports and imports, and includes Modes 1, 2, and 4, as noted above. Looking at total cross-border trade, in 2015, services accounted for 33.2% of the $2.2 trillion total U.S. exports (of goods and services) and 17.7% of the $2.76 trillion total U.S. imports.6 The United States has continually realized surpluses in services trade, which have partially offset large trade deficits in goods trade in the U.S. current account.7

Many services require direct contact between the supplier and consumer and, therefore, service providers often need to establish a presence in the country of the consumer through foreign direct investment (FDI) as characterized by Mode 3. In 2013, U.S. firms supplied $1.3 trillion in services to foreigners through their majority-owned foreign affiliates. In 2013, foreign firms sold $878.5 billion in services to U.S. residents through their majority-owned foreign affiliates located in the United States (Table 1).8

Table 1. Services Supplied to Foreign and U.S. Markets through

Cross-Border Trade and Affiliates, 2010-2013

(billions of dollars)

|

U.S. Exports |

U.S. Imports |

|||

|

Cross-Border Trade |

Through U.S.-owned Affiliates in Foreign Countries |

Cross-Border Trade |

Through Foreign-owned Affiliates in the United States |

|

|

2010 |

$563.3 |

$1,155.2 |

$409.3 |

$701.2 |

|

2011 |

$627.8 |

$1,247.0 |

$435.8 |

$781.6 |

|

2012 |

$656.4 |

$1,285.9 |

$452.0 |

$813.3 |

|

2013 |

$687.9 |

$1,320.9 |

$463.7 |

$878.5 |

Source: Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, available at http://www.bea.gov.

Services in U.S. Trade Agreements

Unlike goods trade where many trade barriers are primarily at the border (e.g., tariffs or quotas), restrictions on services trade occur largely within the importing country, so-called "behind-the-border" barriers. These non-tariff barriers (NTBs) are often in the form of government regulations. Governments regulate service industries to pursue legitimate policy objectives and protect consumers from harmful or unqualified providers (e.g., licensing doctors to ensure they have the relevant medical training to protect public health). Concerns may arise if regulations are protectionist or are applied in a discriminatory and unnecessarily trade restrictive manner to foreign service providers that limits market access, favoring domestic providers. Because services transactions more often require direct contact between the consumer and provider than is the case with goods trade, many of the "trade barriers" that foreign companies face pertain to the establishment of a commercial presence in the consumers' country in the form of direct investment (Mode 3) or to the temporary movement of providers and consumers across borders (Modes 2 and 4).

As the world's largest exporter of services,9 the United States has an interest in opening international markets and has been at the forefront of efforts to liberalize trade in services. The United States has a long history in tackling trade barriers in services in multiple forums, most recently in the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).10

The Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) legislation that Congress renewed and was signed into law on June 29, 2015 (P.L. 114-26),11 contains specific provisions establishing U.S. trade negotiating objectives on services trade. The text broadly states that "[t]he principal negotiating objective of the United States regarding trade in services is to expand competitive market opportunities for the United States." Congress also specifically pointed to the utilization of global value chains and supported pursuing the objectives of reducing or eliminating trade barriers through "all means, including through a plurilateral agreement" with partners able to meet high standards. If the parties reach agreement on TiSA while TPA is in effect, and if the Administration meets certain statutory requirements and timelines, TPA allows Congress to consider the required implementing bill under expedited ("fast track") procedures.

WTO General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS)

The 1995 multilateral GATS is the first and only multilateral framework of principles and rules for government policies and regulations affecting trade in services among the current 162 WTO members.12 The GATS also contains annexes for specific sectors: movement of natural persons, financial services, telecommunications, and air transport services.13

|

Basic Principles of WTO GATS The GATS can be summarized by the basic principles listed below.

|

In the GATS, market access obligations and national treatment commitments are made on a positive, or opt-in, basis subject to a member's specific reservations. That is, each member identifies only those sectors and the modes covered by their liberalization commitments.15 As members can tailor the sectoral coverage to fit their national policy objectives, certain limitations, such as the number of suppliers, may be imposed.

The GATS provides the foundation or floor on which rules in other agreements on services are based, including in U.S. free trade agreements (FTAs). Trade in services has been included in subsequent U.S. bilateral and regional FTAs, including in the TPP. These agreements have built on the GATS, and on each other, to further liberalize trade in services.16

Services and services trade have evolved significantly since GATS went into effect in 1995. Technology innovation such as the Internet has allowed for a greater volume and range of services to be traded and also has led to new barriers to trade in services. Efforts to expand the GATS have been ongoing as part of the WTO Doha Development Agenda (Doha Round) that was launched in December 2001.17 The Doha negotiations are stalled, and the 10th Ministerial Conference of the World Trade Organization (WTO), held in Nairobi, Kenya, concluded in December 2015 with no clear path forward on the Doha Round. The Nairobi Declaration underscored the importance of a multilateral rules-based trading system with complementary regional and plurilateral agreements.18

Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) Negotiations

Largely because of the lack of progress in the WTO Doha Round, a group of 23 WTO members are engaged in discussions on a potential sector-specific, plurilateral agreement to liberalize trade in services.19 Contrary to the WTO MFN principle, a plurilateral agreement applies only to those countries that have signed it. The WTO has allowed exceptions to MFN in plurilateral agreements, such as the WTO Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) and WTO Information Technology Agreement (ITA). Negotiations on a Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) were launched in April 2013, initially led by Australia and the United States.

|

Proposed Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) at a Glance

|

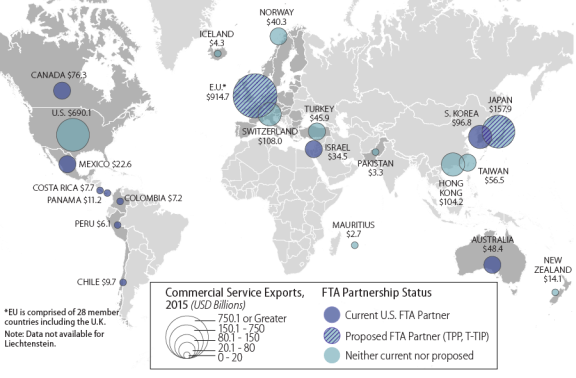

The 23 TiSA participants account for about 70% of world trade in services (see Figure 1).20 The group has been referred to as a "coalition of the willing," as each participant sees a national interest in further liberalizing trade in services. The United States has, or is negotiating, regional and bilateral FTAs with most of the TiSA partners (see Figure 1). Supporters believe a single plurilateral agreement would ensure a common level playing field across a broad set of countries, simplifying conducting business across multiple TiSA counties, and set a new global standard for services trade that could ultimately be incorporated into the WTO in the future. Critics contend that the United States could achieve a higher level of ambition by negotiating separate agreements rather than a "one size fits all" agreement.

|

|

Source: CRS analysis based on WTO Services Profile, http://stat.wto.org/ServiceProfile/WSDBServicePFHome.aspx?Language=E |

Twelve of the Group of 20 (G-20) members are participating in TiSA,21 but some key major emerging markets in the G-20 are not currently parties to the TiSA negotiations, including Brazil, China, and India. While many large emerging economies have relatively small service markets today, the potential for expansion of their markets as providers and consumers of services is great. This not only gives the industries in those countries room to grow domestically, but could make these emerging markets attractive to foreign providers as well.

Of those emerging market countries currently not participating, only China has expressed interest in joining TiSA to date. China's interest has generated differences among TiSA participants. Reportedly, the United States has expressed concerns about China's readiness to undertake the commitments that TiSA would require, given China's limited implementation of other agreements to date, including its GATS commitments and its failure to date to join the GPA.22 The EU and some observers have argued for China's participation sooner rather than waiting for the conclusion of TiSA.

Other observers argue it would be easier to conclude TiSA negotiations without the involvement of these large emerging economies, and then invite those countries to join once the high level of liberalization commitment is established. Supporting this argument is the concept that the agreement overall is reportedly being structured so that it can be "multi-lateralized" in the future and incorporated into the WTO. The chances or timeline of such an event are uncertain, as the TiSA itself remains under negotiation. If TiSA is incorporated into the GATS, in whole or in parts, one concern may be whether it would become harder to update as services evolve, as any new negotiations could be impeded similar to the Doha Round. On the other hand, participants may be able to update TiSA as a stand-alone agreement similar to the current negotiation.

Key Provisions and Negotiating Issues

The structure of the agreement, while still under negotiation, is expected to include four parts:

- A core text that incorporates and builds on key provisions of the GATS and includes horizontal provisions that would apply to all parts of the agreement;

- Commitments on market access and national treatment with each party's schedule and list of exceptions or non-conforming measures;

- Specific sectoral regulatory annexes; and

- Institutional provisions that set the ground rules for how TiSA would function, addressing issues such as amending the agreement in the future or how new members could join.

The current text reportedly contains multiple proposed sectoral annexes, including on land and air transport, e-commerce, distribution/direct selling, energy and environmental services, telecommunications, financial services, and performance requirements, among others.23 The United States Trade Representative (USTR) and many observers have expressed a desire for TiSA to meet or exceed the level of ambition in the services chapters of the proposed TPP, but have acknowledged that this may not be possible for all aspects given the diversity of TiSA parties' level of development and priority interests.24

Like GATS, TiSA would not apply to "services supplied in the exercise of governmental authority."25 TiSA would not constrain a government from taking measures for legitimate policy reasons to protect national security or maintain public order; protect human, animal, or plant health; prevent fraud and deception; or protect individual privacy and safety.

Disciplines and Rules

TiSA would build on the foundational principles of the GATS. Some rules, such as non-discrimination among TiSA partners, would be in the core text and apply horizontally to all sectors across the agreement. Other rules would be sector-specific.

- General Obligations. As mentioned, the core text of TiSA would reinforce and build on the core disciplines of GATS, including most-favored nation treatment, national treatment, and facilitating agreements between parties to establish sector-specific mutual recognition agreements (MRAs).26

- Transparency. Improved transparency and predictability are key principles the United States seeks in its trading partners. TiSA provisions may include good governance and regulatory practices similar to those in other U.S. FTAs. These commitments go beyond GATS, including requirements to publish current and proposed regulations and provide a sufficient period for anyone to comment.27 Negotiators are working to reconcile the regulatory obligations with the varied processes for consulting with public stakeholders that are used by various TiSA participants. The United States and EU, for example, have different processes for developing regulations and timelines for permitting public comment. One option may be for TiSA to permit multiple pathways for parties to achieve transparency and public consultation objectives. According to the EU report of the November 2016 round, the Transparency annex is complete though the text is not yet public.28

- Domestic Regulation. The section on domestic regulation would establish rules related to the licensing and qualification requirements for professional services that are set by each party.

- Movement of Natural Persons. Rules on the movement of foreign nationals (Mode 4) aim to facilitate people providing services through temporary entry and stay for business travel. This has been an issue of concern to Congress. As such, the United States has not yet put forward an offer in this category and may only extend a limited offer, if at all.29 In the proposed TPP, USTR Ambassador Michael Froman committed that the agreement would not have an impact on U.S. immigration law or policy or visa system.30 The EU has proposed including commitments on the temporary entry and stay of highly skilled professionals in a separate protocol rather than within the TiSA core text.31

- State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs). The United States has proposed rules on SOEs, a newer discipline that has gained importance because of the growing economic significance of SOEs in some markets. The TPP SOE chapter is said to be the basis for the TiSA text to ensure non-discrimination, transparency, competition, and fair treatment regardless of ownership.32 The United States reportedly is seeking to expand on the TPP definition of SOEs to also include cooperatives.33

- Government Procurement. TiSA participants are discussing whether to include disciplines on government procurement of services to complement the WTO Government Procurement Agreement (GPA). Most TiSA participants, including the United States and EU, are active or observer parties to the GPA. The TiSA could present an opportunity to encourage or require that all participants become members of the GPA or could build on the GPA commitments. Reportedly, the draft TiSA language is less ambitious than the GPA, and the United States is currently deferring to the existing WTO GPA rather than seeking additional commitments in TiSA.

Market Access

To address market access liberalization commitments, TiSA participants have agreed to a hybrid approach, combining both a negative list and a positive list. Under a negative list, FTA provisions apply to all categories and subcategories of services in all modes of delivery, unless a party to the agreement has listed a service or mode of delivery as an exception. In contrast, under a positive list, each party must specifically opt in for a service sector to be covered and may include limitations. The United States typically uses a more comprehensive negative list approach in its bilateral and regional FTAs for both market access and national treatment. Because of disagreements among the TiSA participants, and in the interest of being compatible with the positive list approach in the GATS, TiSA negotiating parties decided to use a hybrid approach: market access obligations to liberalize service markets are being negotiated under a positive list, while national treatment obligations are being negotiated under a negative list. Each participant's offer is built on the GATS structure for market access commitments, including horizontal commitments and those by individual service sector.34 The positive list may be viewed as less ambitious because new inventions or sectoral innovations would not be covered under TiSA unless they are explicitly added in the future. As national treatment obligations are made on a negative list basis, each participant's schedule would list any reservations that would be excluded from the obligations (including existing measures, or specific sectors or areas of regulation). One source of contention is whether parties are able to broadly carve out "new services." The EU and some other negotiating parties are pressing to exempt all "new services" from all non-discrimination rules to ensure their ability to regulate in the future, but others fear the precedent it would set for future TiSA participants.35

Participants agreed to submit their "best FTA" commitments for TiSA market access offers. This concept is not without controversy, as some participants have limited liberalization commitments in other trade agreements. The U.S. market access offer is reportedly similar to that of the services portion of the TPP,36 and, as mentioned, is said to exclude Mode 4 for temporary movement of people. Some parties express concern that some participants have included a high number of market access reservations, or exemptions.

Sectoral Annexes

Trade agreements on services often require sectoral annexes because many trade barriers are sector-specific. As mentioned, after the Uruguay Round, WTO members reached agreement on sectoral annexes on telecommunications, financial services, and movement of natural persons. TiSA participants are negotiating which sectoral annexes to include, and some of the sectors under discussion are of particular interest to U.S. stakeholders.

Audiovisual

Given the competitiveness of U.S. industry in the audiovisual sector, the United States supports this sector's inclusion in TiSA. Some other countries have traditionally opposed including audiovisual, citing their exception aligns with the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) agreement.37 France and Canada, for example, advocate the "cultural exception" concept, and seek to exclude cultural goods and services from international trade agreements, and thus protect and promote domestic artists and other elements of their domestic culture.38

Express Delivery and Logistics

With competitive industries in express delivery, the United States and EU have put forward a proposal to open markets, but it is unclear what the scope of this annex would include.

E-commerce/Digital Trade

A chapter or annex on e-commerce or digital trade would likely address trade barriers to cross-border data flows, consumer online protection, and interoperability, among other areas, similar to the provisions in TPP.39 It is not clear if TiSA would specify international regulatory cooperation on matters of cybersecurity or in support of small and mid-sized enterprises as in TPP.

Data localization and cross-border data flows are a contentious topic in international trade. Data transfer regulations that restrict cross-border data flows ("forced" localization barriers to trade), such as requiring locally based servers, may limit the type of transactions and services that a firm can sell in a given country. These types of regulations can create additional costs and may serve as a deterrent for firms seeking to enter new markets. On the other hand, localization supporters claim they increase local control and data security.

In its report to the USTR, the Information Technology Industry Council (ITI) noted that its members have experienced "a significant increase in the use" of forced localization requirements that has inhibited their ability to conduct business or do so efficiently. While most of the examples cited by ITI are in non-TiSA countries, the potential future expansion of TiSA makes this a key issue for U.S. technology companies seeking greater access to markets abroad.40 The U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) noted that localization measures often create trade barriers, citing examples from multiple countries, including TiSA participants such as the EU.41

In TPA, Congress provided trade negotiating objectives specific to "digital trade in goods and services and cross-border data flows," instructing the President to ensure that cross-border data flows and electronically delivered goods and services have the same level of coverage and protection as those in physical form, and are not impeded by regulation, except for legitimate objectives. Congress recognized the challenges presented by localization regulations, and sought to ensure that trade agreements eliminate and prevent measures requiring the locating of "facilities, intellectual property, or other assets in a country."

While the United States and EU completed negotiations of the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield replacing the Safe Harbor agreement to permit Trans-Atlantic data flows,42 the Privacy Shield has been challenged, renewing legal uncertainty for such data flows.43 TiSA discussions on cross border data flows had been on hold during the Privacy Shield negotiations and the EU yet to put forward a proposal on cross-border data flows.44

Additionally, a group of U.S. and EU privacy experts issued a report recommending a set of "privacy bridges" to resolve differences via regulatory cooperation.45 Requiring such regulatory cooperation and ongoing dialogue between TiSA members could provide a path forward without changing existing laws in each TiSA country. Negotiators may aim for language that is open enough to enable trade and address evolving technology, but concrete enough for regulators to protect privacy and safeguard cybersecurity.

The United States also proposed provisions in TiSA on the liability of Internet platforms.46 Many U.S. companies in the technology and Internet industry raise concerns that holding intermediaries accountable for content or transactions hosted on their platforms impedes the growth of the digital economy, deterring companies from investing and entering new markets.47 Many seek provisions similar to those in the U.S. Digital Millennium Copyright Act (P.L. 105-304) safe harbors and Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (P.L. 104-104).48

Supporters point to a United Nations joint declaration stating

internet service intermediaries must not be held responsible for content generated by third parties; nor may they be required to control user-generated content. They shall be held responsible only when they fail to exclude content when directed to do so in a lawful court order, issued in accordance with due process, and provided that they have the technical capacity to do so. The intermediaries must be required to be transparent with respect to their practices for the management of traffic or information, and must not discriminate in any way in the treatment of data or traffic.49

Others, including some musicians whose content has been pirated online, believe intermediaries should be held responsible for reviewing all content posted to their online properties.50

Financial Services

TiSA is expected to build on the commitments in the GATS annex on financial services and any additional commitments put forward during earlier discussions in the stalled Doha round.51

In the proposed TPP, financial services are explicitly carved out of the e-commerce chapter, and are therefore not covered by provisions to remove data flow restrictions and localization requirements. Instead, the financial services chapter provision that protects data flows for this sector is more limited. U.S. financial regulators advocated for the explicit ability to restrict cross-border data flows in TPP,52 in addition to the flexibility provided by the prudential exception.53 To address concerns raised by Congress and many in the financial services industry opposed to a potential sector-specific carve out in TiSA (as in TPP), the United States proposed new language for TiSA that would prohibit financial services regulators from imposing barriers to cross-border data flows and data localization requirements except in certain circumstances.54 The U.S. proposal is based on post-TPP discussions between U.S. regulators, Congress, and industry that resulted in support of TPP by many financial services stakeholders.55 Eight of the TPP partners are participating in the TiSA negotiations.56

EU positions in the financial services negotiations also raise potential concerns. For example, the EU stated its position in TiSA is to maintain all existing EU and national laws on privacy protection pertaining to financial services which may not align with the U.S. proposal.57 The continued uncertainty over the United Kingdom's status and the potential political and economic impact of the vote to exit the EU (the so-called "Brexit") also raises questions about the EU's negotiating position given London's current status as the largest global financial center.58

Another question is to what extent TiSA will include regulatory cooperation on financial services, whether through TiSA or another venue such as the G-20. The EU has pressed for regulatory cooperation on financial services in the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP) negotiations between the United States and EU. The United States, however, currently supports regulatory cooperation for financial services through other venues such as (1) the Joint Financial Regulatory Forum, established in July 2016 to replace the U.S.-EU Financial Markets Regulatory Dialogue and include more representatives of regulatory agencies from each side,59 (2) the broader G-20, or (3) Basel III.60

In most U.S. FTAs, including the proposed TPP, and in U.S. bilateral investment treaties (BITs), the financial services provisions incorporate selected investor-state dispute settlement provisions (ISDS) from the applicable investment chapter. This provides private financial service providers access to ISDS under certain circumstances to resolve disputes about alleged breaches of investment obligations by host governments. As TiSA does not include an investment chapter, no ISDS mechanism would exist. Rather, disagreements presumably would be resolved through any government-to-government dispute settlement mechanism set up under TiSA, rather than through an arbitration panel as in ISDS.

Maritime Services. While many countries may seek to include this sector to gain greater access to foreign markets, the United States and some other parties may oppose it. U.S. negotiators are currently constrained by law that prohibits any foreign-built or foreign-flagged vessel from engaging in coastwise trade within the United States.61 Maritime services potentially could be addressed in a broader transportation services annex but a U.S. market access offer would likely not include this sector or would be limited to those port services as allowed for by existing U.S. law.

Professional Services. Current negotiations do not include explicit mutual recognition agreements, but rather discussion aims to facilitate interested parties in recognizing foreign professionals (e.g., lawyers, accountants) and expediting their licensing (similar to TPP provisions). Medical services are said to be excluded from TiSA.

Telecommunications. TiSA would likely build on the GATS telecommunications annex and commitments made by parties to facilitate trade and open markets to competition.62 According to reports, the scope is undetermined as participants debate whether obligations would apply to measures relating to access and use of only public telecommunications networks or to measures related to value added services.63 Initial GATS offers focused on value added services, but, in the context of Doha, many members have put forward offers to improve their existing GATS commitments or to make initial commitments. TiSA could leverage or build on these offers.64 Telecommunications is one of the most restricted sectors in foreign markets for U.S. companies, according to the USTR's annual "National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers."65

Institutional Provisions

The institutional provisions in the proposed TiSA would provide clarity on how the agreement would operate. This section could address how to admit observers or new members into the agreement, or how TiSA could be incorporated into the WTO in the future. Negotiators are also considering whether to implement a rotating secretariat position.66 A state-to-state dispute settlement mechanism will reportedly be included, but no investor-state dispute settlement mechanism as is contained in more comprehensive U.S. FTAs that have a broader scope beyond services.67

Potential Areas of Controversy

Trade negotiations can be a contentious issue in the United States as in other countries. On one hand, the limited scope and focus on services of TiSA may make it less controversial compared to other trade agreements because it excludes sensitive areas of investment, agriculture, and certain manufactured goods that are often hotly debated in trade discussions. Many in the business community support TiSA as an opportunity to increase consistency and predictability among trading partners, to eliminate trade barriers, and to strengthen and update multilateral rules on trade in services beyond the WTO GATS.68 On the other hand, TiSA may raise general debates about agreements to liberalize trade, as well as debates specific to liberalization in the services sector, especially as services can cover sensitive public policy issues like healthcare. Opponents of services liberalization, including some labor unions and civil society groups, are concerned about a number of issues, including the potential impact of TiSA on wages and employment as well as the authority of national, state, and local governments to regulate services. Import-sensitive sectors that might become more open under TiSA, and thus more competitive, may be more likely to oppose it.

One issue specific to services regulation is that, while USTR is the lead trade negotiator for the United States, individual U.S. states and localities regulate many services. Lawyers, for example, are state-licensed and are often required to re-apply in order to practice in other states. Similarly, insurance services are regulated at a state level. Some observers contend that it is unclear how USTR is consulting with state regulators who would be responsible for implementing any commitments made by USTR. The USTR has taken different approaches in the past. For example, in the proposed TPP, the United States listed all state regulations as non-conforming measures and thus excluded them from any TiSA requirements.69 Another option could be for USTR to engage a subset of state regulators and potentially open market access in some sectors in a subset of states who voluntarily agree to the commitments.

One current issue is the application of the TiSA commitments to non-participants. TiSA participants agreed to conduct the negotiations on a non-MFN basis, that is, the benefits of the commitments made by TiSA participants would apply to only those countries that have signed on to the agreement, thereby avoiding "free-riders."

Also being debated is whether or not each TiSA participant would be required to automatically extend to all TiSA participants the same benefits that it grants to other countries in future bilateral or regional free trade deals it enters. The United States supports this "MFN-forward" approach for future trade agreements while others, including the EU, oppose it.70 Negotiators are said to be considering a compromise proposal that would allow TiSA parties to opt-in to the MFN-forward approach.71

Current Outlook

Since negotiations were launched in April 2013, 21 rounds of TiSA negotiations and intercessional meetings have taken place in an effort to make further progress. Recognizing that outstanding issues remain and the U.S. position under a new administration is unclear, the parties canceled the planned December 2016 meeting but are meeting to determine how best to move forward in 2017.72 Given the progress to date, it is unlikely new members will join the TiSA negotiations unless they are willing to accept the provisions agreed to thus far in negotiations.

|

How would TiSA compare with other U.S. FTAs? TiSA could create a common set of rules across trading partners where the United States currently has a patchwork of other trade agreements and commitments. TiSA could be seen as an opportunity to fill gaps in the services liberalization area compared to other FTAs.

|

Issues for Congress

The outlook and timeline for the ongoing TiSA negotiations remain uncertain, as participants are tackling difficult and complex issues. The congressional oversight role in trade negotiations could include monitoring progress on the TiSA negotiations and whether they are advancing or fulfilling TPA negotiating objectives on services trade.

Over the past two years, Congress has conducted oversight of TiSA during House and Senate hearings in the context of digital trade and cross-border data flows, the USTR budget and nominations, and TPA. Some Members voiced support of using TiSA to set "21st century rules" and open markets to expand exports, while others have expressed concern about potential policy impacts in such areas as immigration and cybersecurity. Congress may consider holding TiSA-specific hearings to focus on certain aspects or areas of concern for members.

Potential policy issues for Congress and negotiators to address include the following.

- To what extent are TiSA negotiations consistent with U.S. trade negotiating objectives on services as defined in the TPA legislation? How would TiSA fit with other existing and potential U.S. FTAs, such as the proposed TPP and T-TIP?

- What impact would a completed TiSA have on the U.S. economy and various stakeholders? What would be the positive and negative impacts of completing TiSA?

- Should TiSA participants encourage other countries, such as the emerging economies with potentially large services markets and industries—Brazil, China, and India—to join? Would their presence dilute the negotiations' current level of ambition or spur more countries to join?

- Would the incorporation of TiSA into the WTO GATS make it more effective because of the expanded geographic reach or less effective if it becomes harder to update due to diverse interest of WTO members?

- As advancements in information technology expand the number and types of services that can be traded and help to create new types of services, traditional companies and start-ups are pushing for a modernized legal and regulatory framework to reflect the fast-evolving digital world. Is it possible to develop a trade arrangement that is precise enough to be effective and flexible enough to take into account rapid changes in the services sector?

- How should policymakers balance the responsibility of sovereign governments to regulate services to ensure the safety and privacy of their citizens against the objective of expanding markets in order to increase economic growth and efficiency?

- Should the United States pursue regulatory cooperation efforts in addition to trade agreements in specific service areas such as cross-border data flows where cultural and legal differences and changes in technology limit what can be achieved in trade agreements?

- Given that many regulations in the United States are set by states, should federal policymakers involve states on a regular or formalized basis in ongoing and future trade negotiations or regulatory cooperation efforts, and if so, how? Are there significant service trade barriers to U.S. service providers at the sub-central level in key markets overseas?

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

The graphic of the TiSA parties was created by CRS staff Calvin DeSouza and Amber Wilhelm.

Footnotes

| 1. |

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Trade in Goods and Services table, http://www.bea.gov/international/index.htm. |

| 2. |

Bureau of Economic Analysis, Value Added by Industry as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Product, April 21, 2016, http://www.bea.gov/industry/gdpbyind_data.htm. |

| 3. |

U.S. International Trade Commission, "Recent Trends in U.S. Services Trade: 2016 Annual Report," Investigation 332-345, October 2016, https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/pub4643_0.pdf. |

| 4. |

OECD, Interconnected Economies: Benefitting from Global Value Chains – Synthesis Report, 2013, http://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/interconnected-economies-GVCs-synthesis.pdf. |

| 5. |

The description and examples of modes of delivery are based on, and adapted from, the description contained in Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), GATS: The Case for Open Services Markets, Paris, 2002, p. 60. |

| 6. |

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, online tool http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_ita.cfm. |

| 7. |

The current account includes trade in goods and services as well as income earned on foreign investments and unilateral transfers. |

| 8. |

For more information on U.S. trade in services, see CRS Report R43291, U.S. Trade in Services: Trends and Policy Issues, by Rachel F. Fefer. |

| 9. |

If the European Union (EU) countries are treated separately, the United States was the largest single-country exporter (14.1%) and importer (9.6%) of global commercial services in 2014. World Trade Organization, World Trade Report 2015, p. 30, https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/world_trade_report15_e.pdf. |

| 10. |

For more on TPP see, CRS In Focus IF10000, TPP: An Overview, by Brock R. Williams and Ian F. Fergusson, and CRS Report R44278, The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP): In Brief, by Ian F. Fergusson, Mark A. McMinimy, and Brock R. Williams. |

| 11. |

For more information on TPA, see CRS In Focus IF10038, Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), by Ian F. Fergusson, and CRS Report RL33743, Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) and the Role of Congress in Trade Policy, by Ian F. Fergusson. |

| 12. |

This number does not include Afghanistan or Liberia who will each need to ratify their membership in 2016. |

| 13. |

World Trade Organization, Services: Rules for Growth and Investment, https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/agrm6_e.htm. |

| 14. |

The WTO principle of most-favored-nation (MFN) treatment means that countries cannot normally discriminate between their trading partners, and if a country improves the benefits that it gives to one trading partner, it has to give the same "best" treatment to all the other WTO members so that they all remain "most-favored". |

| 15. |

For more on WTO and GATS, see CRS Report R43291, U.S. Trade in Services: Trends and Policy Issues, by Rachel F. Fefer, and CRS In Focus IF10002, The World Trade Organization, by Ian F. Fergusson and Rachel F. Fefer. |

| 16. |

For example, see CRS Report RL34330, The U.S.-South Korea Free Trade Agreement (KORUS FTA): Provisions and Implementation, coordinated by Brock R. Williams. |

| 17. |

For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10002, The World Trade Organization, by Ian F. Fergusson and Rachel F. Fefer. |

| 18. |

For more on WTO Nairobi Ministerial, see CRS Insight IN10422, The WTO Nairobi Ministerial, by Rachel F. Fefer. |

| 19. |

The participating members are: Australia, Canada, Chile, Taiwan, Colombia, Costa Rica, the EU, Hong Kong, Iceland, Israel, Japan, Korea, Liechtenstein, Mauritius, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Pakistan, Panama, Peru, Switzerland, the United States, and Turkey. Uruguay and Paraguay were participants but withdrew from negotiations in 2015. |

| 20. |

Swiss National Center for Competence in Research, A Plurilateral Agenda for Services?: Assessing the Case for a Trade in Services Agreement, Working Paper No. 2013/29, May 2013, p. 10. |

| 21. |

The Group of Twenty (G-20) is a forum for advancing international cooperation and coordination among 20 major advanced and emerging-market economies. The G-20 members are: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, France, the EU, Germany, India, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Turkey, UK, and United States. For more information on the G-20, see CRS Report R40977, The G-20 and International Economic Cooperation: Background and Implications for Congress, by Rebecca M. Nelson. |

| 22. |

Inside U.S. Trade, "USCBC Head Sees ITA Collapse As Casting Doubt On Chinese Reforms", February 14, 2015. |

| 23. |

Elina Viilup, The Trade in Services Agreement (TISA): An end to negotiations in sight?, European Parliament Directorate-General for External Policies, October 2015, http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2015/570448/EXPO_IDA%282015%29570448_EN.pdf. Bryce Baschuk, "Services Negotiators Anxious to Move Forward," BNA International Trade Reporter, October 13, 2015. |

| 24. |

Trade Reports International Group, "TISA Trouble," Washington Trade Daily, December 7, 2015. |

| 25. |

WTO General Agreement on Trade in Services Part 1, Art 1, 3b. |

| 26. |

A mutual recognition agreement (MRA) is an international agreement by which two or more countries agree to recognize one another's certifications, qualifications, or conformity assessment procedures. |

| 27. |

For more on TPP, see CRS In Focus IF10000, TPP: An Overview, by Brock R. Williams and Ian F. Fergusson. |

| 28. |

European Commission, "Report of the 21st TiSA negotiation round," November 17, 2016, http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2016/november/tradoc_155095.pdf. |

| 29. |

ibid. |

| 30. |

Michael B.G. Froman, Letter to Chairman Orrin Hatch, USTR, April 22, 2015, http://insidetrade.com/sites/insidetrade.com/files/documents/apr2015/wto2015_1321b.pdf. |

| 31. |

European Commission, EU to use its chairmanship of TiSA talks on services to push for major progress, November 30, 2015. The EU proposal can be found here: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2015/december/tradoc_154125.pdf. |

| 32. |

Ibid. Released TPP text: https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/TPP-Final-Text-State-Owned-Enterprises-and-Designated-Monopolies.pdf. |

| 33. |

Inside U.S. Trade, "U.S. Seeking Improvements On Delivery, E-Pay, Postal Services In TISA," August 5, 2016. In the proposed TPP text, a state-owned enterprise is defined as one "(a) that is principally engaged in commercial activities; and (b) in which a Party: (i) directly owns more than 50 percent of the share capital; (ii) controls, through ownership interests, the exercise of more than 50 percent of the voting rights; or (iii) holds the power to appoint a majority of members of the board of directors or any other equivalent management body." |

| 34. |

The European Commission published its initial market access offer as well as explanations for reading it: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/press/index.cfm?id=1133. The U.S. offer would follow a similar format using the GATS classifications for sectors and sub-sectors. |

| 35. |

Adam Behsudi, "Battle lines harden in push for services deal," Politico Pro, July 21, 2016. |

| 36. |

For TPP market access for services, the U.S. non-conforming measures are listed in two annexes: https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/TPP-Final-Text-Annex-I-Non-Conforming-Measures-United-States.pdf and https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/TPP-Final-Text-Annex-II-Non-Conforming-Measures-United%20States.pdf. |

| 37. |

The exemption of audio-visual services is in accordance with the UNESCO Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. Paris, 20 October 2005. EU Member States as well as many developed and developing countries with whom the United States is currently negotiating trade agreements are members of the Convention; the United States is not a member. |

| 38. |

European Parliamentary Research Service, TTIP and the Cultural Exception, August 29, 2014, http://epthinktank.eu/2014/08/29/ttip-and-the-cultural-exception/. |

| 39. |

Inside U.S. Trade, "Despite 'TISA-Plus' Aims, EU's E-Commerce Proposal For T-TIP Falls Short," August 13, 2015. |

| 40. |

Information Technology Industry Council, USTR Request for Public Comments to Compile the National Trade Estimate Report (NTE) on Foreign Trade Barriers, October 28, 2015, http://www.itic.org/dotAsset/c/2/c28b5c56-ef55-488c-bc2b-f8a562f3bb79.pdf. |

| 41. |

U.S. International Trade Commission, Digital Trade in the U.S. and Global Economies, Part 1, July 2013, pp. 5-2. |

| 42. |

Negotiations were completed in June 2016, and the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield went into effect in July 12, 2016. European Commission Press Release, "European Commission launches EU-U.S. Privacy Shield: stronger protection for transatlantic data flows," July 12, 2016, http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-16-2461_en.htm. For more information on Safe Harbor and new Privacy Shield, see CRS Report R44257, U.S.-EU Data Privacy: From Safe Harbor to Privacy Shield, by Martin A. Weiss and Kristin Archick. |

| 43. |

Inside U.S. Trade, "Legal challenges against Privacy Shield begin to mount in Europe," November 3, 2016. |

| 44. |

Inside U.S. Trade, "'MFN-forward' compromise appears set in TISA; deal this year still in doubt," November 17, 2016. |

| 45. |

2015 International Conference of Privacy and Data Protection Commissioners, Privacy Bridges: EU and US Privacy Experts in Search of Transatlantic Privacy Solutions, 2015, https://privacybridges.mit.edu/. |

| 46. |

European Commission, "Report of the 19th TiSA negotiation round 8 – 18 July 2016," July 27, 2016. |

| 47. | |

| 48. |

Ed Black, Computer & Communications Industry Association, submission for U.S. House of Representatives Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property, and the Internet hearing on "International Data Flows: Promoting Digital Trade in the 21st Century," November 3, 2015, http://cdn.ccianet.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/EBlack-Intl-Data-Flows-Testimony-Nov2015.pdf. |

| 49. |

Organization of American States, Press Release R50/11 "Freedom of Expression Rapporteurs Issue Joint Declaration Concerning the Internet," June 1, 2011, http://www.oas.org/en/iachr/expression/showarticle.asp?artID=848. |

| 50. |

Laura Sydell, "Why Taylor Swift Is Asking Congress To Update Copyright Laws," NPR All Tech Considered, August 8, 2016. |

| 51. |

World Trade Organization General Agreement on Trade in Services Annex on financial services, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/serv_e/10-anfin_e.htm. |

| 52. |

Inside U.S. Trade, "Financial Services Firms Fight TPP Data Flow Rules, Backed By House GOP," November 19, 2015. |

| 53. |

The prudential exception in TPP states: The Parties understand that the term "prudential reasons" includes the maintenance of the safety, soundness, integrity, or financial responsibility of individual financial institutions or cross-border financial service suppliers as well as the safety, and financial and operational integrity of payment and clearing systems," https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/TPP-Final-Text-Financial-Services.pdf. |

| 54. |

The U.S. proposed language has not been made public. For more information, see Inside U.S. Trade, "TPP Data Fix Floated In TTIP, TISA Rounds; Brady Hopeful On Enforcement," July 14, 2016. |

| 55. |

Inside U.S. Trade, "Coalition Of Services Industries Announces Support For TPP, Urges Passage This Year," July 12, 2016. |

| 56. |

TPP countries involved in TiSA negotiations are the United States, Canada, Mexico, Peru, Chile, Japan, Australia, New Zealand. TPP participants Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei are not in TiSA. |

| 57. |

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2015/570448/EXPO_IDA%282015%29570448_EN.pdf. |

| 58. |

For more information on Brexit, please see CRS Insight IN10513, United Kingdom Votes to Leave the European Union, by Derek E. Mix, United Kingdom Votes to Leave the European Union, by Derek E. Mix, and CRS Insight IN10517, Possible Economic Impact of Brexit, by James K. Jackson and Shayerah Ilias Akhtar. |

| 59. |

http://ec.europa.eu/finance/docs/160718-fmrd-enhancement_en.pdf and https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/jl0528.aspx. |

| 60. |

Stephen Joyce, "EU, U.S. Continue to Spar Over Treatment of Financial Rules," BNA Bloomberg, July 5, 2016. For more information on Basel III, see CRS In Focus IF10205, Leverage Ratios in Bank Capital Requirements, by Marc Labonte. |

| 61. |

Section 18, Merchant Marine Act of 1920 [P.L. 66-261]. For more information on cargo preferences, see CRS Report R44254, Cargo Preferences for U.S.-Flag Shipping, by John Frittelli. |

| 62. |

World Trade Organization General Agreement on Trade in Services Decision on negotiations on basic telecommunications, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/serv_e/19-bastl_e.htm. |

| 63. |

Inside U.S. Trade, "TISA Parties Plan Four Rounds By July 2016 To Advance Priority Annexes," November 1, 2015. |

| 64. |

https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/serv_e/s_propnewnegs_e.htm#telecommunication. |

| 65. |

Ambassador Michael B.G. Froman, 2015 National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers, U.S. Trade Representative, 2015, https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/2015%20NTE%20Combined.pdf. |

| 66. |

Baschuk, Bryce, "Services Negotiators Anxious to Move Forward", BNA Blooomberg, October 13, 2015. |

| 67. |

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2015/570448/EXPO_IDA%282015%29570448_EN.pdf. |

| 68. |

Coalition of Service Industries, https://www.servicescoalition.org/negotiations/trade-in-services-agreement. Team TiSA, http://teamtisa.org/the-tisa-agreement/what-is-the-tisa. |

| 69. |

The released TPP text, for example, lists as a non-conforming measure "All existing non-conforming measures of all states of the United States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico" in Annex I. |

| 70. |

Inside U.S. Trade, "Leaked TISA Core Text Shows 'MFN Forward' Fight Still Dragging On," July 9, 2015. |

| 71. |

Inside U.S. Trade, "'MFN-forward' compromise appears set in TISA; deal this year still in doubt," November 17, 2016. |

| 72. |

Baschuk, Bryce, "Election Sinks Global Services Pact, Trade Officials Say", BNA Blooomberg, November 18, 2016. |

| 73. |

For more on U.S. FTA partners, see CRS Report R44044, U.S. Trade with Free Trade Agreement (FTA) Partners, by James K. Jackson. |