U.S.-UK Free Trade Agreement: Prospects and Issues for Congress

Prospects for a bilateral free trade agreement (FTA) between the United States and the United Kingdom (UK) are of increasing interest for both sides. In a national referendum held on June 23, 2016, a majority of British voters supported the UK exiting the European Union (EU), a process known as “Brexit.” The Brexit referendum has prompted calls from some Members of Congress and the Trump Administration to launch U.S.-UK FTA negotiations, though other Members have moderated their support with calls to ensure that such negotiations do not constrain the promotion of broader transatlantic trade relations. On January 27, 2017, President Trump and UK Prime Minister Theresa May discussed how the two sides could launch high-level talks and “lay the groundwork” for a future U.S.-UK FTA. In July, the two sides launched a U.S.-UK Trade and Investment Working Group to explore a possible post-Brexit FTA. Negotiations on a bilateral FTA between the United States and UK would represent a change in U.S. transatlantic trade policy, which under the Obama Administration had focused on negotiating a U.S.-EU Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP) FTA.

Formal U.S.-UK FTA negotiations cannot start immediately. On March 29, 2017, Prime Minister May sent a letter to the European Council notifying it of the UK’s intention to leave the EU. This triggered the two-year Article 50 exit process under the Treaty of the European Union. Until the UK formally exits, it remains a member of the EU, which retains exclusive competence over trade negotiations. During this time, and in the absence of any preferential trade agreement between the United States and the EU, World Trade Organization (WTO) parameters continue to govern U.S.-UK trade—as they do for U.S. trade with all other EU member states. In the meantime, the United States and the UK could pursue preliminary “informal” discussions on a potential bilateral FTA.

The prospects for a future U.S.-UK FTA depend on a number of variables, including the terms of the UK’s negotiated withdrawal from, and future trade relationship with, the EU, as well as the UK’s redefined terms of trade within the WTO. A U.S.-UK FTA could include reciprocal provisions to expand access to goods, services, agriculture, and government procurement markets; enhance and develop new bilateral trade-related rules and disciplines in areas such as intellectual property rights (IPR), investment, and digital trade; and cooperate on regulatory issues such as transparency and sector-specific concerns.

Congress has important legislative, oversight, and advisory responsibilities with respect to any potential U.S.-UK FTA. The U.S. Constitution grants Congress the power to regulate commerce with foreign nations. Congress also establishes overall U.S. trade negotiating objectives, which it updated in the 2015 Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) legislation (P.L. 114-26). In addition, Congress would face a decision on future implementing legislation for a final U.S.-UK FTA to enter into force. Under TPA, an FTA could be eligible to receive expedited legislative consideration if Congress determines that the FTA advances trade negotiating objectives and satisfies TPA’s various other requirements, including notification to and consultations with Congress on the status of the negotiations.

U.S.-UK Free Trade Agreement: Prospects and Issues for Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- U.S.-UK Trade and Investment Trends

- U.S.-UK FTA Prospects

- Brexit Variables Affecting U.S.-UK FTA Prospects

- UK-EU Trade Relations

- UK Relations with the WTO

- Specific Issues in Potential U.S.-UK FTA

- Market Access

- Trade-Related Rules

- Regulatory Cooperation and Standard-Setting

- Issues for Congress

- Prospects for a "Successful" U.S.-UK FTA

- Economic and Strategic Impact

- Role in U.S. Trade Policy

- Implications for T-TIP and Transatlantic Relations

- Outlook

Figures

- Figure 1. U.S. Trade with the UK in Goods and Services, 2003-2016

- Figure 2. U.S. Trade with the UK and the Rest of the EU

- Figure 3. U.S. Investment with the UK and the Rest of the EU

- Figure 4. Brexit Variables that May Affect U.S.-UK FTA Prospects

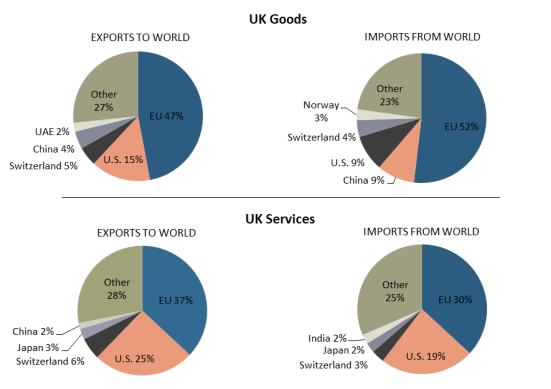

- Figure 5. UK Goods and Services Trade with the World, 2016

Summary

Prospects for a bilateral free trade agreement (FTA) between the United States and the United Kingdom (UK) are of increasing interest for both sides. In a national referendum held on June 23, 2016, a majority of British voters supported the UK exiting the European Union (EU), a process known as "Brexit." The Brexit referendum has prompted calls from some Members of Congress and the Trump Administration to launch U.S.-UK FTA negotiations, though other Members have moderated their support with calls to ensure that such negotiations do not constrain the promotion of broader transatlantic trade relations. On January 27, 2017, President Trump and UK Prime Minister Theresa May discussed how the two sides could launch high-level talks and "lay the groundwork" for a future U.S.-UK FTA. In July, the two sides launched a U.S.-UK Trade and Investment Working Group to explore a possible post-Brexit FTA. Negotiations on a bilateral FTA between the United States and UK would represent a change in U.S. transatlantic trade policy, which under the Obama Administration had focused on negotiating a U.S.-EU Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP) FTA.

Formal U.S.-UK FTA negotiations cannot start immediately. On March 29, 2017, Prime Minister May sent a letter to the European Council notifying it of the UK's intention to leave the EU. This triggered the two-year Article 50 exit process under the Treaty of the European Union. Until the UK formally exits, it remains a member of the EU, which retains exclusive competence over trade negotiations. During this time, and in the absence of any preferential trade agreement between the United States and the EU, World Trade Organization (WTO) parameters continue to govern U.S.-UK trade—as they do for U.S. trade with all other EU member states. In the meantime, the United States and the UK could pursue preliminary "informal" discussions on a potential bilateral FTA.

The prospects for a future U.S.-UK FTA depend on a number of variables, including the terms of the UK's negotiated withdrawal from, and future trade relationship with, the EU, as well as the UK's redefined terms of trade within the WTO. A U.S.-UK FTA could include reciprocal provisions to expand access to goods, services, agriculture, and government procurement markets; enhance and develop new bilateral trade-related rules and disciplines in areas such as intellectual property rights (IPR), investment, and digital trade; and cooperate on regulatory issues such as transparency and sector-specific concerns.

Congress has important legislative, oversight, and advisory responsibilities with respect to any potential U.S.-UK FTA. The U.S. Constitution grants Congress the power to regulate commerce with foreign nations. Congress also establishes overall U.S. trade negotiating objectives, which it updated in the 2015 Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) legislation (P.L. 114-26). In addition, Congress would face a decision on future implementing legislation for a final U.S.-UK FTA to enter into force. Under TPA, an FTA could be eligible to receive expedited legislative consideration if Congress determines that the FTA advances trade negotiating objectives and satisfies TPA's various other requirements, including notification to and consultations with Congress on the status of the negotiations.

Introduction

In a June 23, 2016, national referendum, a majority of British voters supported the United Kingdom (UK) exiting the European Union (EU), a process known as "Brexit." Since then, various Members of Congress have voiced support for launching U.S.-UK free trade agreement (FTA) negotiations, while other Members have moderated their support with calls to ensure that such negotiations do not undercut the promotion of broader U.S.-EU trade relations.1 President Donald Trump, since taking office, has continued to express support for Brexit, and stated his intention to negotiate a U.S.-UK FTA "quickly" that is "[g]ood for both sides."2 During a meeting on January 27, 2017, President Trump and UK Prime Minister Theresa May discussed how the two sides could launch high-level talks and "lay the groundwork" for a future U.S.-UK FTA.3 In July, the two sides launched a U.S.-UK Trade and Investment Working Group to explore a possible post-Brexit FTA.

U.S.-UK FTA negotiations would represent a change in U.S. transatlantic trade policy, which, under the Obama Administration, focused on negotiating a U.S.-EU Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP) FTA.4 Bilateral FTA negotiations also would represent a change from the Obama Administration's focus on multiparty regional negotiations, such as on T-TIP and notably the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).5 At the same time, the United States and the UK have had long-standing trade ties. The United States has viewed the UK as a liberalizing force within the EU, and often has found itself more aligned with the UK on trade policy approaches than with the EU overall.

At the same time, the notion of a U.S.-UK FTA is not new. For example, some policymakers expressed interest previously in exploring the possibility of the UK joining the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).6 More broadly, the notion of a "special relationship" between the United States and UK is long-standing.7

Formal U.S.-UK FTA negotiations cannot start immediately. The UK is legally precluded from engaging in its own trade negotiations under its EU membership terms. On March 29, 2017, Prime Minister May sent a letter to the European Council notifying the body of the UK's intention to leave the EU. This action triggered the two-year Article 50 exit process under the Treaty on European Union.8 Until the UK completes what could be prolonged negotiations with the EU on its terms of withdrawal and formally exits, the UK remains a member of the EU, which retains competence over trade negotiations.9 So long as the UK is a member of the EU and in the absence of any preferential trade agreement between the United States and the EU, World Trade Organization (WTO) parameters continue to govern U.S.-UK trade—as they do for U.S. trade with all other EU member states. Meanwhile, the United States and the UK could pursue informal discussions on a potential bilateral FTA.

Congress has important legislative, oversight, and advisory responsibilities regarding a potential U.S.-UK FTA. The role of Congress in U.S. trade policy is rooted in Article 1, Section 8, of the U.S. Constitution, which grants Congress the power to regulate commerce with foreign nations. Congress establishes overall U.S. trade negotiating objectives, which it updated in the 2015 Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) legislation (P.L. 114-26).10 This grant of TPA is valid through 2021 (unless Congress enacts a possible extension disapproval resolution in 2018). Congress also would face a decision on future implementing legislation for a U.S.-UK FTA to enter into force. An FTA could receive expedited legislative consideration if Congress determines that it advances trade negotiating objectives in TPA and meets TPA's other requirements, including for the President to notify and consult with Congress on the status and content of the negotiations.

U.S.-UK Trade and Investment Trends

The United States and the UK have a deep, extensive economic relationship. U.S. firms, large and small, are involved in U.S.-UK trade, directly and as a part of integrated supply chains. In 2016, U.S. goods and services exports to the UK totaled about $121 billion, and U.S. goods and services imports from the UK reached $107 billion, yielding a $15 billion U.S. trade surplus (Figure 1).11 In terms of the EU, the UK accounted for about one-fifth of U.S. total trade with the EU-28, making it the United States' second-largest trading partner within the EU after Germany.

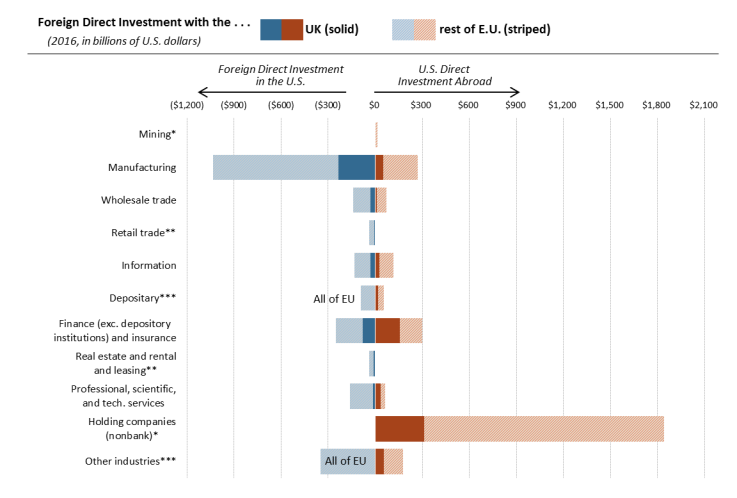

|

Figure 1. U.S. Trade with the UK in Goods and Services, 2003-2016 |

|

|

Source: CRS, based on data from Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). |

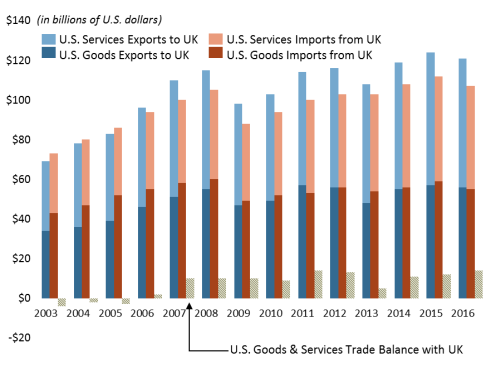

Globally, in goods trade, the UK ranked as the United States' fifth-largest export destination and seventh-largest source of imports. Top U.S. goods exports to the UK include civilian aircraft and parts, nonmonetary gold bullion (bulk gold before coining), pharmaceutical products, and art. Top U.S. imports from the UK include machines and machinery, motor vehicles, and pharmaceutical products.12 The UK is the United States' largest services trading partner, accounting for close to one-tenth of U.S. total trade in services and spanning sectors such as financial services, tourism, education, and business services.13 The United States is the UK's largest food and agricultural trading partner outside the EU for both exports and imports.14 While the U.S.-UK trade is significant and stands out in particular sectors, it is outweighed by U.S. trade with the rest of the EU (Figure 2).

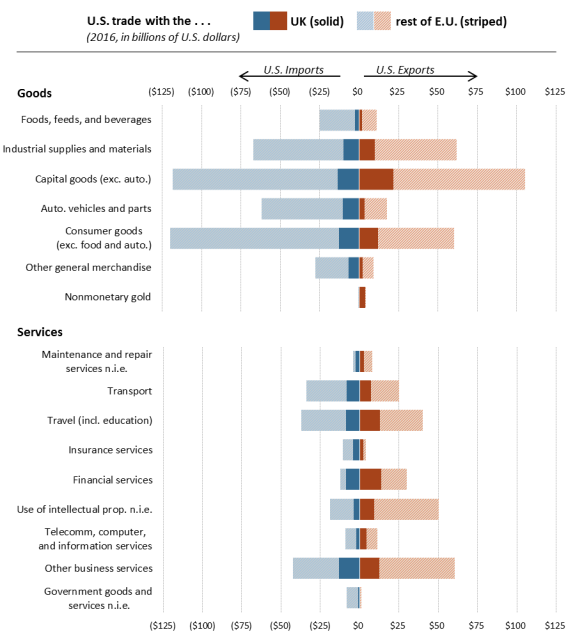

Bilateral foreign direct investment (FDI) is also prominent in the relationship (see Figure 3). In recent years, U.S. and UK majority-owned multinational enterprises (MNEs) have employed over 2 million employees combined at their subsidiaries in each other's markets.15 In 2015, U.S.-UK FDI totaled $1.2 trillion, composed of $682 billion of U.S. outbound FDI and $556 billion of inbound FDI to the United States. The UK ranked as the second-largest destination for U.S. FDI abroad (the Netherlands being the largest), and the largest source of FDI in the United States (ahead of Japan).

|

|

Source: CRS, data from U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Notes: The term "n.i.e." denotes "not included elsewhere."<del> </del> |

A number of industries stand out in the U.S.-UK investment relationship, notably finance and insurance, "professional, scientific, and technical" services, and manufacturing (particularly chemicals, transportation, equipment, and primary and fabricated metals). U.S. companies are attracted to the UK for its open business environment, workforce skills, and (current) access to the EU Single Market, among other things (see text box). U.S. financial companies in the UK presently can take advantage of "passporting rights," through which they can set up a "hub" in the UK and then carry out their activities across the EU without having to establish a separate entity and/or obtain authorization in each individual member country.16

|

Is Brexit Affecting U.S. Companies Operating in the UK? Many large U.S. companies, in a range of sectors, have a presence in the UK. The Brexit vote does not immediately affect U.S. trade and investment with the UK, but presumably would when the UK's withdrawal from the EU takes effect. Meanwhile, the uncertainty over the outcome of Brexit may affect the business planning and investment decisions of U.S. firms operating in the UK. To what extent U.S. companies generally maintain their significant presence in a post-Brexit UK as a base for their European operations is unclear. One survey found that 40% of U.S. firms with a base in the UK were considering shifting operations to other places in the EU due to Brexit.17 In contrast, Apple announced plans to build a new UK headquarters in London.18 U.S. financial companies may be particularly affected, for instance, if Brexit results in a loss of "passporting rights." U.S. banks such as Citi, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, and Morgan Stanley reportedly are considering reducing their UK presence in preparation for Brexit.19 Brexit also might affect the attractiveness of the UK as a "jumping-off point" to access the broader EU market for trade; potential loss of UK access to the EU Single Market could increase tariffs for U.S. businesses in the UK that export from the UK to other parts of the EU. Whirlpool is planning to reorient a factory in the UK to focus on producing dryers solely for UK customers, and to use a Poland factory instead to make dryers for continental Europe—a change it said was due to a reorganization of its regional operations, though some see the move as a response to Brexit. Other companies have said that their business decisions in the UK are not related to Brexit. For instance, Ford says that it plans to cut jobs from its Welsh engine facility because of underperformance, not Brexit.20 |

UK majority-owned MNEs with U.S. operations also play a role in U.S. trade. They represented $43.1 billion of U.S. exports of goods and $48.7 billion of U.S. imports of goods with affiliates in 2015.21

The United States and UK have had minimal trade frictions. However, the UK notably has been a part of the long-running U.S.-EU dispute in the WTO over subsidies to Boeing and Airbus.

U.S.-UK FTA Prospects

Brexit is expected to return authority to the UK to set its own external tariffs and its trade policy more broadly, a competence that currently resides with the EU for all EU member states. Formal U.S.-UK FTA negotiations, nevertheless, cannot start immediately. Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) sets a two-year period for exit negotiations, although some analysts raise the possibility of the process taking longer. Until the UK completes what could be prolonged negotiations for its withdrawal from the EU and formally exits, the UK remains a member of the EU, and the EU continues to have exclusive competence over the UK's trade policy as it does for other EU member states—meaning that the EU negotiates a common trade policy with non-EU countries on behalf of (and with input from) its member states.22 In the meantime, the United States and the UK could pursue preliminary "informal" discussions. The line between "formal" and "informal" negotiations may be blurry, but moves such as exchanging tariff offers presumably would cross the line. A European Commission spokesperson described informal discussions as, "You can read the menu, but you can't order the food."23

Brexit Variables Affecting U.S.-UK FTA Prospects

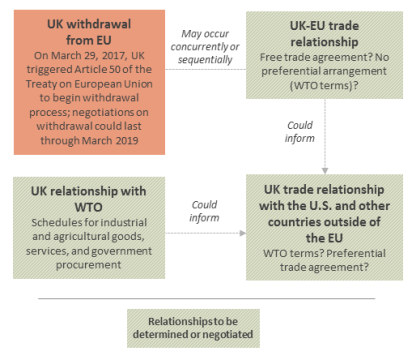

Several variables in Brexit could affect prospects for a U.S.-UK FTA (see Figure 4). These include UK-EU negotiations on the UK's withdrawal from the EU, UK-EU negotiations on their trade relationship once the UK has formally exited the EU, and UK negotiations with other WTO members on its WTO schedule, as well as any transitional arrangements that the UK negotiates until final agreements in these areas are concluded.

|

Figure 4. Brexit Variables that May Affect U.S.-UK FTA Prospects |

|

|

Source: CRS. Notes: This is a highly simplified representation of the many variables in the Brexit process. |

How long it takes to negotiate Brexit would affect when the UK is legally free to pursue formal FTA negotiations with the United States or other countries. The trade relationship that the UK negotiates with the EU could affect what positions the United States and the UK may take in their own bilateral FTA negotiations. Finally, the terms that the UK negotiates with the WTO could set a baseline for the U.S.-UK FTA negotiations, since U.S. FTAs traditionally have built on WTO terms and rules for enhanced market access.

UK-EU Trade Relations

The status of UK trade relations with the United States depends, to a large degree, on UK-EU trade relations going forward, as U.S. businesses that currently trade and invest with the UK benefit from the UK's access to the Single Market. Without clarity on the UK's internal market, it is difficult for U.S. negotiators to know the starting point for negotiating an FTA with the UK.

Future UK-EU trade relations, in turn, depend on the outcomes of two negotiations: (1) the terms of the UK's negotiated withdrawal from the EU under the two-year Article 50 process of the Treaty on European Union (TEU); and (2) UK-EU negotiations on their future trade relationship. Regarding sequencing, the UK favors conducting the negotiations about the UK-EU future partnership in parallel with the withdrawal negotiations.24 In contrast, the EU has stated that the withdrawal negotiations must precede the negotiations over trade relations.25

From a trade policy perspective, Brexit presents the question of the extent to which, if at all, the UK would retain access to the Single Market for goods and services, as well as what EU regulations the UK chooses to retain, and the associated trade-offs. Such questions underscore the high level of integration between the UK and the EU-27; the EU is the UK's largest trading partner for both goods and services (see Figure 5), though its share has declined in recent years.

|

|

Source: CRS, data from World Trade Organization. |

In a January 17, 2017, speech, Prime Minister May set out the British government's negotiating objectives and plan for exiting the EU.26 A February 2017 white paper subsequently released by the UK government elaborated on these positions.27 The Prime Minister confirmed that the UK is not seeking membership in the EU Single Market, but rather the negotiation of an FTA with the EU to allow "the freest possible trade in goods and services between Britain and the EU's member states" (see text box).28 The Prime Minister further noted that

[the] agreement [between the UK and EU] may take in elements of current single market arrangements in certain areas—on the export of cars and lorries for example, or the freedom to provide financial services across national borders – as it makes no sense to start again from scratch when Britain and the remaining [m]ember [s]tates have adhered to the same rules for so many years....29

At the same time, the Prime Minister left open the possibility of no trade agreement with the EU if negotiations between the UK and the EU do not lead to an acceptable outcome, saying "no deal for Britain is better than a bad deal for Britain."30 EU officials and some industry groups have pushed back on this view.31 Some have characterized scenarios of a negotiated UK-EU trade deal as a "soft" Brexit and the absence of such a deal as a "hard" Brexit.32

The UK government also stated a goal of being able to pursue new trade agreements with other countries post-Brexit. The Prime Minister observed that "full [c]ustoms [u]nion membership," which binds the UK to the EU's common external tariff, prevents the UK from negotiating its own trade deals with other countries, and the white paper stated, "the UK will seek a new customs arrangement with the EU...." For some observers, questions arose over the extent to which the UK might remain a part of the EU customs union. Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond later confirmed that it is "clear" that the UK cannot stay in the customs union, as that would prevent the UK from independently negotiating its own trade deals outside of the EU.33

On March 29, 2017, Prime Minister May triggered the two-year Article 50 process for withdrawal from the EU.34 June 2017 marked the start of the withdrawal negotiations.35 After reported infighting over how to implement Brexit, UK Cabinet ministers jointly affirmed the importance of a "time-limited" transition period to cushion Brexit's impact after the UK exits the EU, while underscoring that this period is not a way for the UK to stay in the EU "through the backdoor."36

|

Examples of Possible Forms for UK-EU Trade Relationship The aftermath of the Brexit vote saw many possible scenarios for the post-Brexit UK-EU trade relationship.37 These scenarios vary in their level of Single Market access, obligations to implement EU rules and regulations, opportunity to participate in EU decisionmaking, requirements to contribute to the EU's budget, and political feasibility. UK Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union David Davis stated that the UK was not seeking an "off the shelf" model.38 Nevertheless, existing arrangements between the EU and other countries could shed light on some possibilities for negotiating approaches. WTO Terms? If the UK does not negotiate preferential market access with the EU, the "default" would be that WTO commitments govern the UK-EU relationship. WTO terms for the UK and, to some extent, the EU would have to be renegotiated as a result of Brexit (see next section). Under its WTO commitments, EU average tariff rates are low (see Table 1), but are significant compared to the zero tariffs that apply to intra-EU trade, and would be especially consequential for sectors such as autos where the UK-EU market is deeply integrated. Free Trade Agreement? The UK could negotiate a comprehensive bilateral FTA with the EU. For example, the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), concluded in 2014, covers tariff and nontariff barriers related to goods, services, agriculture, investment, government procurement, and regulatory cooperation. EU FTAs have varied in their scope of trade liberalization and rules-setting. The EU has said the UK cannot have a better trade relationship with the EU outside of the Single Market than within it. Specialized Arrangements? Other arrangements could serve as models. For example, Norway, as a member of certain European groupings, has full access to the Single Market, in exchange for which it must implement EU rules for the internal market. In contrast, Switzerland has more limited, but tailored and arguably more complex, access to the Single Market; it has numerous bilateral agreements with the EU covering various sectors, giving it partial access to the Single Market, in exchange for which it must incorporate related EU regulations and directives into its legal framework. Even more limited access occurs for Turkey through its customs union with the EU, which gives it access to the Single Market for goods, but not for agriculture or services. As a customs union member, Turkey adopted the EU's common external tariff for the products covered. Under these arrangements, the countries have no vote in EU decisions on rules and regulations and, in the case of Norway and Switzerland, must contribute to the EU's budget. |

The EU has relatively low external tariffs on goods, but the UK may seek lower or no tariffs in certain sectors. Some observers expect the UK to focus on certain sectors in its trade negotiations with the EU given these sectors' high level of UK-EU integration, such as autos, chemicals, manufactured goods, and mineral fuels—sectors in which a large share of UK exports go to the EU.39 Financial services also may be a focal point (see text box). Agriculture may be sensitive, given various interests and the EU's higher average tariffs on agricultural.

In the meantime, in what may be a lengthy negotiation with the EU of its terms of withdrawal, the UK remains an EU member, and the EU continues to have exclusive competence over the UK's trade policy as it does for other EU member states.40 This precludes formal U.S.-UK FTA negotiations starting immediately, but does not preclude informal discussions.

|

Financial "Passporting" Rights Presently, U.S. and other financial companies in the UK can take advantage of "passporting rights," through which they can incorporate in one EU member state (e.g., the UK) and carry out activities in other member states "solely on the basis of their authori[z]ation and prudential supervision by their state of incorporation."41 Brexit confronts financial companies operating in the UK with uncertainty over the level of future access to the broader EU market from the UK. As noted earlier, several U.S. banks, such as Citi, Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, and Morgan Stanley, reportedly are considering reducing their UK presence in preparation for expected disruption from Brexit.42 UK banks such as HSBC and UBS also have announced similar plans or considerations.43 New locations could include Brussels, Dublin, Frankfurt, and New York. Some analysts point out that the EU has established an "equivalence" regime that extends limited access rights to non-EU countries, such as the United States, that have rules that the EU considers to be "equivalent." This approach grants weaker rights than those under full "passporting."44 |

UK Relations with the WTO

Another factor affecting U.S.-UK FTA prospects is any redefinition of the UK's commitments in the WTO, which would form the basis for any future trade relationships that the UK negotiates outside the EU, such as with the United States or other countries.45 Redefinition of the UK's terms in the WTO raises unprecedented issues for the WTO.46

The UK is a founding member of the WTO. It currently has WTO membership both on an individual basis and as a part of the EU. The UK's commitments to other WTO members presently are through the EU's schedule of commitments in the WTO. Transitioning to an independent position in the WTO will require the UK to negotiate new goods and services schedules on its WTO market access commitments (see text box). The WTO, which currently has 164 members, operates on a consensus basis. Some aspects of the UK's WTO transition, such as establishing its most-favored-nation (MFN) tariff levels, may be relatively straightforward.47 The UK could "cut and paste" the EU's bound tariff rates to its own schedule, though, of course, the UK's internal economic and political dynamics may lead it to pursue different tariff levels. Establishing tariff-rate quotas (TRQs) may be more complicated, as doing so will require reallocation of the EU's quotas under the WTO. The EU maintains TRQs on products such as beef, poultry, dairy, cereals, rice, sugar, fruits, and vegetables. Other aspects include commitments under the Government Procurement Agreement (GPA), of which the UK is a member through its EU membership but is not currently a nation-state member.

Some observers note that the UK may face difficulty securing approval from WTO members for its proposed schedule, pointing to the possibility that countries that have territorial disputes with the UK—such as Argentina over the Falkland Islands or Spain over Gibraltar—could use the WTO negotiation process as leverage to address these issues with the UK.48 Others say that any lack of formal approval ("certification") of the UK's proposed new schedule should not be a bar to the UK negotiating trade agreements with other countries. They note that the EU's schedule as the EU-28 has lacked full certification, and that has not stopped the EU from entering into FTAs. Under this view, so long as the UK does not make its trade terms more restrictive than the EU's schedule, it may not run afoul of WTO obligations.49

|

WTO Schedule of Commitments Each WTO member negotiates "schedules" on the market access it commits to providing other WTO members. The UK will have to reestablish its independent goods and services schedules, as well as in the plurilateral Government Procurement Agreement (GPA). Goods Schedule. A country's goods schedule includes its most-favored-nation (MFN) "bound" tariff rates (i.e., the maximum tariff level) for manufactured goods and agricultural products. The schedule also includes tariff-rate quotas (TRQs) for agricultural products, under which rates for imports inside a quota are lower, and in many cases significantly so, than for those outside the quota. In addition, agreements on export subsidies and domestic support for particular industries, among other things, are a part of a goods schedule. Services Schedule. Services commitments include commitments to provide market access and national treatment for service activities, subject to any terms and conditions specified in the schedule. Countries can take exception to providing MFN treatment to the services sectors that they specify. Government procurement. A country also specifies which central and sub-central government entities, and above which thresholds, it commits to complying with the GPA, a plurilateral WTO agreement of which both the United States and the EU are members. |

In terms of sequencing, negotiations for UK's transition in the WTO could happen alongside UK withdrawal negotiations. According to UK's Secretary of State for International Trade Liam Fox,

[i]n order to minimi[z]e disruption to global trade as we leave the EU, over the coming period the Government will prepare the necessary draft schedules which replicate as far as possible our current obligations. The Government will undertake this process in dialogue with the WTO membership. This work is a necessary part of our leaving the EU. It does not prejudge the outcome of the eventual UK-EU trading arrangement.50

Meanwhile, the UK's WTO commitments remain as set out in the EU's schedules that apply to all EU member states until Brexit occurs.51

In the absence of any preferential trade arrangement with a country, WTO terms would form the basis of the UK's trade relationship with that country. Since the United States and the EU do not have an FTA with each other (T-TIP negotiations are on pause), WTO terms already govern U.S. trade with the UK, as they do with other EU member countries. Those terms would continue to govern unless and until a U.S.-UK FTA is negotiated and enters into force.

Specific Issues in Potential U.S.-UK FTA

Congress established U.S. trade negotiating objectives in the 2015 Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) legislation (P.L. 114-26).52 U.S.-UK FTA negotiations, if launched in the next few years, presumably would be conducted under TPA. Such negotiating objectives, as well as TPA's notification and consultation requirements, would be expected to guide the administration's negotiations on a potential U.S.-UK FTA.

Based on U.S. trade negotiating objectives, the past U.S. approach has been to negotiate comprehensive and high standard FTAs to liberalize trade and investment through reciprocal commitments to reduce and eliminate tariff and nontariff barriers in goods, services, and agriculture, as well as to establish trade rules and disciplines to govern trade among the parties. These commitments expand on WTO obligations and address new issues.

Possible areas in U.S.-UK FTA negotiations are highlighted below.

Market Access

Commitments to expand and enhance market access have been a core part of U.S. FTAs. Enhanced market access addresses a number of issues, including reducing and eliminating tariff and nontariff barriers. Tariff liberalization could be a component of a potential U.S.-UK FTA. Industrial tariffs applied by the United States and UK (through the EU's tariff schedule) are already relatively low (see Table 1), but higher in certain sensitive sectors.53 For instance, EU tariffs on automobiles are 10%. Expanding agricultural market access could be a key area of focus for the United States, given high EU average tariffs or tariff-rate quotas (TRQs) on products such as meat, fish, sugar, dairy products, soft drinks, and wine.

|

Tariff |

UK (EU tariff schedule) |

United States |

|

Overall |

||

|

Simple average MFN applied |

5.2% |

3.5% |

|

Trade-weighted average |

3.0% |

2.4% |

|

Agriculture |

||

|

Simple average MFN applied |

11.1% |

5.2% |

|

Trade-weighted average |

7.8% |

3.8% |

|

Non-agriculture |

||

|

Simple average MFN applied |

4.2% |

3.2% |

|

Trade-weighted average |

2.6% |

2.3% |

Source: CRS compilation, WTO Tariff Profiles.

Notes: Data for "simple average MFN applied" are from 2016, and for "trade-weighted average" from 2015.

It remains to be seen if a U.S.-UK FTA would face the same issues with respect to market access that confronted U.S. and EU negotiators in T-TIP. In those negotiations, the United States and the EU exchanged tariff offers to reduce and eliminate tariffs on most industrial goods, but opted to leave agricultural tariff issues, which were highly sensitive, until "end-game" negotiations.

Services market access could be significant in potential FTA negotiations, given the high level of U.S.-UK services trade. Regulatory and other barriers to trade in services could be a focal point (see "Regulatory Cooperation and Standard-Setting" section below). Other areas of interest could include issues such as licensing and qualification requirements for professional service providers, as well as rules on the movement of foreign nationals for temporary entry and stay for business travel.54 Some services issues that were complex in T-TIP may be less so in U.S.-UK FTA negotiations. For instance, "cultural exceptions" were controversial in T-TIP due to the interest of countries like France in protecting its audiovisual sector.55

Other market access issues could arise in terms of public procurement. U.S. FTAs include rules to ensure transparent, nondiscriminatory access for U.S. firms to trading partners' public procurement markets in covered sectors at certain thresholds, and vice versa. In the transatlantic context, frictions have included, on the U.S. side, concerns about the transparency of EU public procurement policies, and on the EU side, concerns about U.S. restrictions to certain sensitive sectors, Buy American legislation, and access to U.S. state-level government procurement markets.56 These issues could also be politically sensitive in U.S.-UK FTA negotiations. President Trump has advocated for a "Buy American" and "Hire American" policy, while the UK released a post-Brexit industrial strategy including a goal of using "strategic government procurement to drive innovation and enable the development of UK supply chains."57 More restrictive Buy American policies may run afoul of the WTO Government Procurement Agreement (GPA); the United States is a member of the GPA, and the UK also is a GPA member through its membership in the EU (but is not currently a nation-state member of that agreement).

Trade-Related Rules

U.S. FTAs contain rules and disciplines governing a range of trade-related areas. Potential areas of interest in a bilateral FTA include the following.

Investment. Given high levels of bilateral FDI, investment rules could be a major part of a U.S.-UK FTA. U.S. international agreements on investment typically include market access commitments, investor protections such as nondiscriminatory and minimum standard of treatment, and compensation for direct and, in limited cases, indirect expropriation, as well as enforcement of these obligations through investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS).58 An open question could be treatment of ISDS, a mechanism for an investor to take a host country to binding arbitration for alleged breaches of obligations. Historically favored by U.S. government and business, ISDS has been a core part of many U.S. and European investment agreements, but triggered public debates on T-TIP because of potential implications for regulatory sovereignty and other issues. An added dynamic is the EU's proposal for an "Investment Court System," which the EU included in recent trade agreements. It differs from ISDS; for example, it has an appellate mechanism while ISDS decisions are final. It is not clear what position the Trump Administration or the UK would take regarding this issue.

Digital trade. Cross-border data flows are key to the U.S.-UK trading relationship, whether for manufacturing operations or financial services firms. Similar to provisions in TPP, a U.S.-UK FTA could address ways to facilitate cross-border data flows for business transactions and reduce barriers to digital trade, such as "forced" localization requirements.59 Any future UK-EU regulatory relationship may inform the nature of U.S.-UK FTA negotiations on digital trade. Discussions on cross-border flows in a bilateral FTA may not have the same level of sensitivities over privacy issues that constrained the T-TIP negotiations in the wake of disclosures of National Security Agency (NSA) surveillance activity.60 Such issues were particularly controversial for countries like Germany.

Intellectual property rights (IPR). Another area of significant interest is rules on IPR protection and enforcement. Both the United States and the UK are major centers of research and development and innovation, view intellectual property as a source of comparative advantage, and are strong proponents of advancing trade-related rules for IP R protection and enforcement.61 A U.S.-UK FTA could present opportunities for cooperation on IPR issues, such as combating cyber theft of trade secrets and enhancing protections for biologics. A bilateral FTA may not face the same challenges as did T-TIP on IPR issues such as geographical indications (GIs), which protect regional food names. Protection of GIs is a key priority for countries like France and Italy, but less so for the UK (though the UK does have over 60 registered GIs, including for Stilton Cheese and Cornish Pasty).62 The United States has favored protecting regional food names primarily through trademarks.

Other issues. A U.S.-UK FTA could also include rules and disciplines in a range of other areas. Some of these are areas that "traditionally" have been a part of U.S. FTAs, such as labor and the environment. The UK's status as a developed economy with strong environmental protections could mitigate concerns of some stakeholders about U.S. outsourcing or reducing environmental standards through an FTA. Other issues for possible discussion have been more recent additions to U.S. FTAs, including rules on state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and commitments to support exports by small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).63

Regulatory Cooperation and Standard-Setting

A U.S.-UK FTA could include commitments on regulatory cooperation and standard-setting, both in terms of horizontal commitments, such as transparency and stakeholder input in regulatory processes, as well as sector-specific commitments. Many of the products in which in the United States and UK trade are in high-value-added but heavily regulated sectors that intersect with consumer safety issues.64 Sectoral issues of potential interest might include motor vehicle, pharmaceutical, chemical, and food safety regulatory regimes. The United States may view a U.S.-UK FTA as an opportunity to open the UK market to U.S. exports currently constrained by EU restrictions, such as sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) barriers and technical barriers to trade (TBT). For instance, frictions on the U.S. side have included EU restrictions such as those on chlorine-washed chicken, hormone-raised beef, and genetically engineered food.65 In general, the UK is more closely aligned with the U.S. approach to regulatory issues than the EU but not necessarily in all areas. For instance, some UK consumers continue to reject genetically engineered foods.

|

Financial Services Regulatory Cooperation? Regulatory cooperation in the financial services sector, a key sector in the bilateral economic relationship, could be a significant focus in FTA negotiations. In the T-TIP context, UK officials and financial services industries favored including financial services regulatory issues as part of the U.S.-EU FTA negotiations, a sentiment echoed by some in the U.S. Congress and in the U.S. financial services sector. Some Members of Congress previously called on the Obama Administration to address regulatory discrepancies between the U.S. and EU financial systems in the negotiations, while other Members raised concerns about potentially reopening the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 111-203). The Trump Administration's position is unclear. |

Regulatory cooperation has been a major sticking point in the overall transatlantic relationship because of differing regulatory approaches. Broadly speaking, the United States prefers risk-based assessments, while the EU favors the "precautionary principle" through preventive decisionmaking in case of risk; both sides view their approaches as science-based.66 T-TIP negotiations became weighted down by EU public debate over the impact of a U.S.-EU FTA on food safety and other regulatory concerns, though subsequent progress has been made in some areas. For example, in March 2017, the United States and the EU amended a 1998 U.S.-EU Mutual Recognition Agreement to allow for U.S. and EU regulators to rely upon each other's inspections of pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities to avoid duplication of inspections.67

How the United States and the UK approach regulatory cooperation and standard setting within the context of a bilateral FTA will depend in large part on the extent to which the UK reclaims its regulatory authority from the EU during Brexit negotiations, including whether the UK will choose to retain EU regulations or adopt its own national regulations. The UK has said that it plans to introduce a "Great Repeal Bill" to remove the European Communities Act 1972 from its statute book and convert the body of existing EU law (known as "acquis") into domestic law where practical and appropriate, after which the UK will decide which elements of the law to keep, amend, or repeal.68 To the extent that UK regulations align with EU regulations, it may be easier for the UK to continue trading with the EU, but compatibility with U.S. standards could be an issue. In some areas, UK divergences from the EU in regulatory approaches that minimize inefficiencies could translate into advantages for UK trade relations with the United States or other countries.

Issues for Congress

Prospects for a "Successful" U.S.-UK FTA

Prospects for a U.S.-UK FTA depend on a number of factors over which Congress may conduct oversight in the near term. These include how U.S.-UK FTA negotiations could best advance U.S. trade negotiating objectives established in TPA, as well as the barriers to addressing those negotiating objectives. Other issues include timing for when formal negotiations could start legally. As discussed, this depends in large part on the outcome of the UK's Brexit negotiations with the EU. The United States and UK also may have political considerations to take into account in determining when to launch trade negotiations, including in the context of overall trade policy priorities. Capacity to negotiate may be an issue on the UK side. The UK has "outsourced" trade negotiating skills to Brussels for decades as part of the EU's exclusive competence over trade policy, but has sought to rebuild that capacity in recent months. The UK has also indicated interest in negotiating a number of trade agreements, including with countries that have FTAs with the EU and those that do not. The EU has concluded over 50 trade agreements worldwide.69 Given the many directions UK interest could go and the still growing UK negotiating capacity, an open question is where a U.S.-UK FTA would rank in the priorities.

Some analysts believe that, once legal and procedural roadblocks to U.S.-UK FTA negotiations are removed, the negotiations would be relatively easy and fast to conclude. One reason is that the UK has been characterized as a liberalizing force within the EU that has shared the United States' traditional support for trade liberalization and a rules-based international trade system. Another reason is that the negotiating dynamics presumably would be less complex because U.S.-UK FTA negotiations would involve two economies, rather than T-TIP's 29 economies (United States and EU-28 member states). Some may counter, however, that the economic impact of a U.S.-UK FTA also would be smaller than T-TIP (see next section).

Some analysts believe that U.S.-UK FTA negotiations would not face the level of substantive and procedural difficulty that beset the T-TIP negotiations. Given these dynamics, some have called for a U.S.-UK FTA to be implemented within 90 days after Brexit—90 days being the amount of time the executive branch must give Congress before it signs a trade agreement under TPA.70 Others caution that U.S. FTAs typically take much longer to negotiate and that, even among like-minded trading partners, domestic political interests can complicate trade negotiations.71

Economic and Strategic Impact

Presently, U.S.-UK FTA talks are in an informal, pre-negotiations stage. U.S. FTAs are generally viewed as having widely distributed economic benefits and concentrated economic costs. The economic impact of a specific FTA would depend, in part, on the breadth and depth of FTA commitments. Yet, broad macroeconomic factors generally are considered to play an important role in affecting the U.S. economy as a whole.72 Given the openness of the U.S. and UK economies, a U.S.-UK FTA may be expected to generate modest economic benefits.73 Nevertheless, due to the size of the bilateral economic relationship, further trade liberalization could yield significant benefits for particular industries. Regarding the enhanced market access and other benefits that a concluded FTA could bring, some experts caution that no U.S.-UK FTA would replicate the broader EU market access that U.S. affiliates in the UK enjoy by virtue of the UK's membership in the EU and access to the EU Single Market.74 A potential bilateral FTA could present costs, such as in terms of job losses and other transition costs stemming from increased competition. Such costs, however, could be less than those of other U.S. FTAs, as the United States and the UK are both highly advanced economies.

As U.S.-UK FTA negotiations advance, Congress likely would examine various studies by the U.S. government (e.g., the U.S. International Trade Commission) and external organizations to assess the expected impact of the agreement on the U.S. economy. 75 It should be kept in mind that economic models are highly sensitive to assumptions. Further, data limitations and other issues—including the fact that a number of variables beyond trade affect economic performance—make it difficult to develop precise estimates of the impact of a particular trade agreement on the economy.

Any economic impact of a U.S.-UK FTA is in the longer term, given that the commencement of U.S.-UK FTA negotiations is at least two years away. Over the short run, Brexit-specific factors may have more economic impact on the United States. These factors include the economic impact of Brexit on the EU and on the UK, the amount of time it takes for the UK withdrawal from the EU, and the final composition of the UK-EU economic relationship—all of which could have implications for U.S. trade and investment with both the UK and the EU. Another aspect of the economic relationship is the impact Brexit will have on financial flows and any secondary impact on the dollar if markets perceive additional uncertainty for a EU economic recovery.

A U.S.-UK FTA could have broader strategic implications. For instance, a U.S.-UK FTA could play a similar role to what TPP and T-TIP were expected to play in setting globally relevant rules and disciplines to support economic growth and multilateral trade liberalization through the WTO.76 It also could strengthen the broader U.S.-UK relationship and add a new dimension to the transatlantic trade relationship. In addition, a U.S.-UK FTA could apply pressure on unlocking past stumbling blocks to progress in T-TIP, assuming that both the United States and EU seek to continue negotiations.

Role in U.S. Trade Policy

A potential U.S.-UK FTA would fit into a new U.S. emphasis on bilateral trade deals under the Trump Administration, which has expressed a clear preference for focusing on bilateral trade deals in lieu of multiparty ones.77 The Trump Administration has argued that a bilateral approach allows the United States to use its economic strength and focus on U.S. priorities. This represents a shift from the Obama Administration, which made it a priority to negotiate multiparty regional trade deals, such as TPP and T-TIP. Regional negotiations, while more complex, offer the opportunity for mutually beneficial but politically challenging trade-offs to occur across multiple countries.78

Once Brexit procedural roadblocks to U.S.-UK FTA negotiations are overcome, the question arises of when the administration may launch formal negotiations, amid other potential U.S. trade negotiations and other trade policy actions. The Trump Administration says that it aims to focus its future trade efforts on the possibility of renegotiating and reviewing existing FTAs, turning first to NAFTA,79 and pursuing new bilateral FTAs, including with TPP participants, particularly Japan, and possibly other countries.

Given the already relatively low levels of trade and investment barriers between the United States and the UK, some question whether it is appropriate for the administration to give priority to negotiating a U.S.-UK FTA. Proponents of a U.S.-UK FTA argue that concluding a bilateral FTA between two economic and political international heavyweights will contribute to future trade liberalization efforts. Others say that, in light of resource constraints and other factors, the United States should pursue FTAs with other countries that present greater barriers to trade. For example, some may argue that the United States would benefit more from resuming T-TIP negotiations or pursuing bilateral deals with countries that were a part of the TPP.

Implications for T-TIP and Transatlantic Relations

Since July 2013, the United States and the EU have engaged in T-TIP negotiations to liberalize U.S.-EU trade and investment and set globally relevant rules and disciplines to boost economic growth and support multilateral trade liberalization.80 The 15th round, the last under the Obama Administration, occurred in October 2016. By then, the United States and the EU had consolidated texts in a number of areas, but unresolved complex and sensitive issues remained and raised questions over whether political momentum exists to overcome differences. For instance, public opposition to T-TIP runs high in the EU due to concerns over issues such as over food safety regulations, ISDS, and data privacy. Aspects of T-TIP also were controversial among U.S. stakeholders.

T-TIP negotiations are on pause, and the Trump Administration has stated that it is "currently evaluating the status of these negotiations."81 Should the United States and the EU decide to resume T-TIP negotiations prior to the UK exiting the EU, the European Commission would continue negotiating the T-TIP on behalf of all 28 member states, including the UK.

Brexit presents uncertainties for T-TIP, despite the Trump Administration's expressions of support for expanding transatlantic trade. Some observers argue that Brexit is a major setback given the UK's historical liberalizing role in the EU on trade issues. Others argue that a U.S.-UK FTA could pressure the EU to reenergize T-TIP, as the EU may be wary of the UK receiving preferential access to the U.S. market without the EU securing similar access. Likewise, if the agreement "in principle" announced in July 2017 on an EU-Japan FTA leads to a ratified FTA between those two economies, it could accelerate U.S. interest in resuming negotiations to ensure U.S. firms' competitiveness in the EU market.82 Should the United States and the EU decide to resume T-TIP negotiations prior to the UK exiting the EU, the European Commission would continue negotiating the FTA on behalf of all 28 member states, including the UK. After Brexit, the UK could seek to remain in the T-TIP negotiations or could join a potential concluded agreement.

Outlook

While U.S. and UK interest in negotiating a bilateral FTA is high, including on the part of the Trump Administration and many Members of Congress, the Brexit process means that formal negotiations are at least two years off. In the meantime, the United States and UK can discuss an FTA informally, though such discussions may be constrained by uncertainty surrounding the status of the future UK-EU trade relationship, among other factors. Congress has an important role in examining a potential U.S.-UK trade agreement, U.S. trade negotiating priorities, and other issues through oversight of, and consultations with, the Trump Administration.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

[author name scrubbed], Visual Information Specialist, provided assistance with the graphics in this report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

In the 115th Congress, see H.Res. 60 (Dent), and U.S. Congress, House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Subcommittee on Terrorism, Nonproliferation, and Trade and Subcommittee on Europe, Eurasia, and Emerging Threats, Next Steps in the "Special Relationship"-Impact of a U.S.-UK Free Trade Agreement, 115th Cong., 1st sess., February 1, 2017. In the 114th Congress, see S. 3123 (Lee), S.Res. 520 (Rubio), H.Res.817 (Dent), and concurrent resolutions H.Con.Res. 146 (Brady) and S.Con.Res. 47 (Hatch), as well as Speaker of the House, "Speaker Ryan Calls for Free Trade Agreement with UK After Brexit," press release, June 27, 2016. |

| 2. |

Shawn Donnan, "Trump's UK Trade Pledge: Hurdles to a Quick Deal," Financial Times, January 15, 2017. For statements since President Trump entered office, see CSPAN, "President Trump and British Prime Minister Theresa Hold News Conference," January 27, 2017; and CSPAN, "President Trump Rally in Melbourne, Florida," February 18, 2017. Transcripts for these events are not available on the White House website as of the time of this writing. |

| 3. |

The White House, "President Trump and Prime Minister May's Opening Remarks," press release, January 27, 2017. |

| 4. |

CRS In Focus IF10120, Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP), by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 5. |

The United States and 11 other Asia-Pacific countries signed the TPP in February 2016 under the Obama Administration, but the United States withdrew from TPP in January 2017 under the Trump Administration. CRS Insight IN10443, CRS Products on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 6. |

U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC), The Impact on the U.S. Economy of Including the United Kingdom in a Free Trade Arrangement With the United States, Canada, and Mexico, Publication 3339, August 2000. |

| 7. |

CRS Report RL33105, The United Kingdom: Background and Relations with the United States, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 8. |

UK Department of Exiting the EU, "Prime Minister's Letter to Donald Tusk Triggering Article 50," correspondence, March 29, 2017. |

| 9. |

CRS Report RS21372, The European Union: Questions and Answers, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 10. |

CRS Report RL33743, Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) and the Role of Congress in Trade Policy, by [author name scrubbed]; and CRS In Focus IF10038, Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 11. |

The UK also reports having an overall surplus in trade in goods and services with the United States. See, e.g., UK Office for National Statistics (ONS), "The UK trade and investment relationship with the United States of America: 2015," September 5, 2016. Factors may include possible methodological differences in U.S. and UK statistical agencies' trade data calculations. |

| 12. |

Data from Global Trade Atlas. |

| 13. |

Data from U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). |

| 14. |

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS), United Kingdom: Exporter Guide 2016, December 13, 2016. |

| 15. |

BEA, "United Kingdom – International Trade and Investment Country Facts." |

| 16. |

Her Majesty's Government (HM Government), Review of the Balance of Competences between the United King and the European Union, The Single Market: Financial Services and the Movement of Capital, February 2014, p. 30. |

| 17. |

Zlata Rodionova, "Brexit: 40% of US Firms with British Offices are Considering Relocating to the EU," Independent, December 14, 2016. |

| 18. |

U.S. Chamber of Commerce, "Apple 'Optimistic' About Post-Brexit UK," press release, February 14, 2017. |

| 19. |

Silvia Sciorilli Borrelli, "U.S. Banks Lay Groundwork to Leave London—Reluctantly," PoliticoPro, November 18, 2016. |

| 20. |

Peter Campbell and Jim Pickard, "Ford Plans to Cut More Than 1,100 Jobs at UK's Bridgend Plant," Financial Times, March 1, 2017. |

| 21. |

Sarah Stutzman, "Activities of U.S. Affiliates of Foreign Multinational Enterprises in 2015," BEA, August 2017. |

| 22. |

CRS Report RS21372, The European Union: Questions and Answers, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 23. |

Josh Lowe, "Why a U.S.-UK Trade Deal Could Be Harder Than It Sounds," Newsweek, January 26, 2017. |

| 24. |

UK Department of Exiting the EU, "Prime Minister's Letter to Donald Tusk Triggering Article 50," correspondence, March 29, 2017. |

| 25. |

European Council, "Statement by the European Council (Art. 50) on the UK Notification," March 29, 2017; Duncan Robinson and Mehreen Khan, "European Parliament Adopts Brexit Resolution," Financial Times, April 5, 2017. |

| 26. |

UK Government, "The Government's Negotiating Objectives for Exiting the EU: PM Speech," January 17, 2017. The Single Market entails "four freedoms"— free movement of goods, capital, services, and people within the EU. |

| 27. |

HM Government, The United Kingdom's exit from and new partnership with the European Union, white paper, February 2017. |

| 28. |

UK Government, "The Government's Negotiating Objectives for Exiting the EU: PM Speech," January 17, 2017. |

| 29. |

Ibid. |

| 30. |

Ibid. |

| 31. |

For instance, see U.S.-UK Business Council, "Toward a New UK-EU Relationship: The Importance of Transitional Arrangements," January 26, 2017. |

| 32. |

The terms "soft Brexit" and "hard Brexit" also have been used to describe the possibilities of the UK exiting the EU with a withdrawal agreement in place or without such an agreement, respectively. |

| 33. |

Alex Morales and Robert Hutton, "Hammond Confirms Brexit Means U.K. Also Leaving Customs Union," Bloomberg Government, March 9, 2017. |

| 34. |

UK Department of Exiting the EU, "Prime Minister's Letter to Donald Tusk Triggering Article 50," correspondence, March 29, 2017. |

| 35. |

European Commission, "State of Play of Article 50 Negotiations with the United Kingdom," press release, July 12, 2017. |

| 36. |

Andrew Sparrow, "Hammond and Fox: We Will Leave Customs Union During Brexit Transition," The Guardian, August 13, 2017; Simon Marks, "Infighting UK Ministers Seek Truce on Brexit Transition Period," Politico, August 13, 2017. |

| 37. |

Jean-Claude Piris, If the UK Votes to Leave: The Seven Alternatives to EU Membership, Centre for European Reform, January 2016. |

| 38. |

UK Government, "Exiting the European Union: Ministerial Statement," oral statement by Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union David Davis in the House of Commons on the work of the Department for Exiting the European Union, September 5, 2016. |

| 39. |

Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), United Kingdom, Country Report, generated February 1, 2017. |

| 40. |

CRS Report RS21372, The European Union: Questions and Answers, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 41. |

HM Government, Review of the Balance of Competences Between the United King and the European Union, The Single Market: Financial Services and the Movement of Capital, February 2014, p. 30. |

| 42. |

Silvia Sciorilli Borrelli, "U.S. Banks Lay Groundwork to Leave London—Reluctantly," PoliticoPro, November 18, 2016. |

| 43. |

Pamela Barbagalia, "HSBC, UBS to Shift 1,000 Jobs Each from UK in Brexit Blow to London," Reuters, January 18, 2017. |

| 44. |

Marcin Szczepański, Understanding Equivalence and the Single Passport in Financial Services: Third-country Access to the Single Market, European Parliamentary Research Service, February 2017. |

| 45. |

UK Government, "The government's negotiating objectives for exiting the EU: PM speech," January 17, 2017. |

| 46. |

WTO, "Azevȇdo addresses World Trade Symposium in London on the state of global trade," press release, June 7, 2016. |

| 47. |

The MFN tariff is the normal nondiscriminatory tariff that a WTO member charges on imports from another WTO member, excluding preferential tariffs under FTAs and other schemes or tariffs charged inside quotas. |

| 48. |

Joe Watts, "Brexit: UK's WTO Status 'Could Be Blocked Over Territorial Disputes'," Independent, December 11, 2016. |

| 49. |

Geoff Raby, "The EU's Ambiguous Legal Position in the WTO Reduces the Uncertainty over Britain's Post-Brexit Trading Relationships," Policy Exchange, November 19, 2016; Aakanksha Mishra, "A Post Brexit UK in the WTO: The UK's New GATT Tariff Schedule," in Legal Aspects of Brexit: Implications of the United Kingdom's Decision to Withdraw from the European Union, ed. Jennifer Hillman and Gary Horlick (Washington, DC 2017). |

| 50. |

UK Parliament, "UK's Commitment at the World Trade Organization: Written Statement – HCWS316," made by Secretary of State for International Trade and President of the Board of Trade Liam Fox, December 5, 2016. |

| 51. |

Julian Braithwaite, "Ensuring a Smooth Transition in the WTO as We Leave The EU," blog post, January 23, 2017. |

| 52. |

CRS Report RL33743, Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) and the Role of Congress in Trade Policy, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 53. |

WTO, Tariff Profiles. |

| 54. |

CRS Report R44354, Trade in Services Agreement (TiSA) Negotiations: Overview and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 55. |

Through cultural exceptions, countries provide special support to domestic industries that they consider culturally sensitive, such as through broadcasting quotas, subsidies, and local content requirements. These measures can limit market access to such industries for foreigners. For example, France maintains cultural exceptions for its film and television industries. Led by France, some EU member states called for the exclusion of the audiovisual services sector from the T-TIP negotiations. |

| 56. |

European Commission, Report from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament on Trade and Investment Barriers and Protectionist Trends, for the period July 1, 2014 through December 31, 2015, June 20, 2016. |

| 57. |

HM Government, Building our Industrial Strategy, Green Paper, January 2017. |

| 58. |

CRS In Focus IF10052, U.S. International Investment Agreements (IIAs), by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 59. |

CRS Report R44565, Digital Trade and U.S. Trade Policy, coordinated by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 60. |

CRS Report R44257, U.S.-EU Data Privacy: From Safe Harbor to Privacy Shield, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 61. |

UK Government, "IP and Brexit: The Facts," August 2, 2016. |

| 62. |

EU, Database of Origin & Registration (DOOR), accessed March 15, 2017. For background, see CRS Report R44556, Geographical Indications (GIs) in U.S. Food and Agricultural Trade, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 63. |

CRS Insight IN10443, CRS Products on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 64. |

Chad P. Bown, "A UK-US Trade Stumbling Block: Regulations" (video), Peterson Institute for International Economics, January 27, 2017. |

| 65. |

CRS Report R44564, Agriculture and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP) Negotiations, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 66. |

CRS Report R43450, Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) and Related Non-Tariff Barriers to Agricultural Trade, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 67. |

U.S. Food & Drug Administration, "Mutual Recognition Promises New Framework for Pharmaceutical Inspections for United States and European Union," press release, March 2, 2017. |

| 68. |

HM Government, The United Kingdom's Exit From and a New Partnership with the European Union, February 2017, p. 9. |

| 69. |

European Commission, "The EU's Bilateral Trade and Investment Agreements – where are we?", memo, December 3, 2013, http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2012/november/tradoc_150129.pdf. |

| 70. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Subcommittee on Terrorism, Nonproliferation, and Trade, Next Steps in the "Special Relationship": Impact of a U.S.-UK Free Trade Agreement, Testimony by Nile Gardiner, The Heritage Foundation, 115th Cong., 1st sess., February 1, 2017. |

| 71. |

Caroline Freund and Christine McDaniel, "How Long Does It Take to Conclude a Trade Agreement With the US?", blog, Peterson Institute for International Economics, July 21, 2016; Doug Palmer, "Trump Could Face Long Path to US-UK Trade Deal," POLITICO, December 30, 2016. |

| 72. |

CRS Report R44546, The Economic Effects of Trade: Overview and Policy Challenges, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 73. |

For instance, the ITC conducted a study finding that, in 2012, existing U.S. bilateral and regional trade agreements expanded U.S. aggregate trade by about 3%, and U.S. real gross domestic product (GDP) and U.S. employment each by less than 1%. See ITC, Economic Impact of Trade Agreements Implemented Under Trade Authorities Procedures, 2016 Report, Publication Number: 4614, June 2016. |

| 74. |

Daniel S. Hamilton and Joseph P. Quinlan, The Transatlantic Economy 2017, American Chamber of Commerce to the European Union (AmCham EU) and Center for Transatlantic Relations, p. 2. |

| 75. |

Of historical interest may be an ITC study exploring the economic impact of the UK joining the NAFTA. ITC, The Impact on the U.S. Economy of Including the United Kingdom in a Free Trade Arrangement With the United States, Canada, and Mexico, Publication 3339, August 2000, p. iii. |

| 76. |

CRS Report R44361, The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP): Strategic Implications, coordinated by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 77. |

USTR, The President's 2017 Trade Policy Agenda, March 2017. |

| 78. |

Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), "The Future of Global Trade" Armchair Conversation with: Ambassador Michael Froman, USTR, and John J. Hamre, President and CEO, CSIS, January 13, 2016. |

| 79. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, Nomination Hearing for Wilbur Ross to be next Secretary of Commerce, 115th Cong., January 5, 2017. For an overview of NAFTA, see CRS In Focus IF10047, North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 80. |

CRS In Focus IF10120, Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP), by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 81. |

USTR, 2017 Trade Policy Agenda and 2016 Annual Report, March 2017, p. 136. |

| 82. |

CRS Insight IN10738, The Proposed EU-Japan FTA and Implications for U.S. Trade Policy, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |