The Proposed EU-Japan FTA and Implications for U.S. Trade Policy

On July 6, 2017, ahead of the G-20 annual summit, the European Union (EU) and Japan announced reaching an agreement "in principle" on a bilateral free trade agreement (FTA), following 18 rounds of negotiations over four years. The EU and Japan aim for entry-into-force (EIF) of the agreement in early 2019. Considerable uncertainty surrounds the agreement, however, as some commitments remain under negotiation and current United Kingdom (UK) negotiations over withdrawal from the EU ("Brexit") further complicate the path forward. (The European Commission negotiates FTAs on behalf of the EU and its member states, under the EU's common external trade policy.)

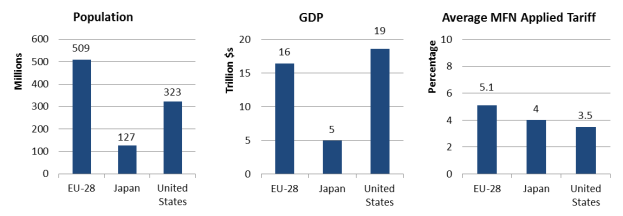

The two partners characterized the proposed FTA as strategically significant and as a strong message of support for trade liberalization. Though average tariffs are already relatively low in both countries, the agreement, which eliminates most tariffs and establishes common trade rules and disciplines on a number of issues, could be economically and strategically consequential. The two partners account for nearly 30% of global production, are home to many of the world's largest companies in key industries, and include more than 630 million consumers (Figure 1). Some analysts downplay the significance of the agreement due to uncertainty over its final content and the extent to which it would affect trade and investment outcomes in each party. The proposed FTA could place U.S. companies at a competitive disadvantage in two major markets and affect U.S. ability to shape international trade norms.

|

Figure 1. EU, Japan, and U.S. Demographics |

|

|

Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF) World Economic Outlook, April 2017; and WTO Tariff Profiles. Notes: Applied MFN tariffs are the most-favored-nation tariffs that each WTO member applies on imports from other WTO members. MFN tariffs currently apply to trade between the EU, Japan, and the United States. |

Agreement Contents

Market access. The proposed agreement would commit the two partners to eliminate nearly all tariffs between them, most upon EIF, with tariffs on more sensitive items, including autos and many agricultural products, phased out over time. Once fully implemented, 99% of EU and 97% of Japanese tariff lines would be eliminated. Some observers have called the agreement a "cars for cheese" deal, as key commitments in economically significant sectors include the EU's elimination of its 10% tariff on passenger motor vehicle imports, and Japan's removal of restrictions on imports of dairy, cheese, and other agricultural products. The agreement also would liberalize several services sectors, cover temporary movement of business personnel, and increase public procurement access, including railways, between the parties.

Regulatory cooperation. The two partners provisionally agree to strengthen regulatory cooperation and address technical barriers to trade (TBT), such as by using the same international standards for motor vehicle product safety, and using a framework for developing sector-specific mutual recognition agreements (MRAs). The parties also commit to addressing sanitary and phytosanitary standards (SPS) barriers to agriculture trade, but reserve as domestic policy choices treatment of hormones and genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

Rules. The agreement would build on WTO intellectual property rights (IPR) commitments, including trade secret protection; require Japan to protect over 200 EU geographical indications (GIs) on foodstuffs, wines, and spirits, a top EU commercial interest and longstanding concern of the United States; and establish rules regarding labor, the environment, and state-owned enterprises. Some rules remain under negotiation, including treatment of investment disputes. The EU favors its Investment Court System proposal, while Japan reportedly favors existing investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) frameworks, similar to U.S. FTAs. Other issues are expected to be excluded entirely, such as whaling and illegal logging, to some environmental groups' dismay, as well as substantive commitments on cross-border data flows, sensitive issues in the EU.

U.S. Trade Policy Implications

The implications of the proposed EU-Japan FTA may influence Congress' oversight of, and legislation on, U.S. trade policy. The agreement demonstrates that some major economies aim to continue with trade liberalization and rules-setting, despite shifts in U.S. trade policy under President Trump's "America First" approach, which has increasingly focused on "unfair" trading practices related to U.S. domestic import competition and review of past U.S. FTAs such as NAFTA. It also raises the questions of whether the United States will play a leading or reactive role in future international trade agreement negotiations and the associated costs and benefits of either approach.

U.S. trade agreement negotiations. Favoring bilateral over multi-country FTAs, the President withdrew the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and is reviewing the status of the now-paused Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP) FTA negotiations. If the EU-Japan FTA becomes effective, it could hasten U.S. interest in resuming the T-TIP negotiations and pursuing a bilateral FTA with Japan to ensure U.S. firms' competitiveness in these markets. Many argue that the 2010 completion of the EU-South Korea FTA similarly spurred U.S. ratification of its own FTA with South Korea in 2011.

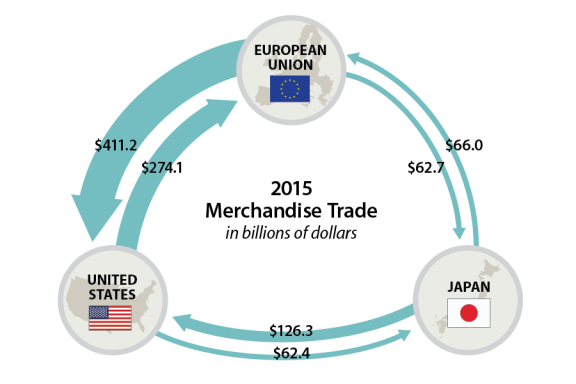

U.S. commercial implications. An EU-Japan FTA could increase the relative price of U.S. goods and services exports to both the EU and Japan, lowering their competitiveness in key U.S. markets (Figure 2). The impact on U.S. firms would vary by product, with intensively traded products and those with the highest preference margin (the spread between MFN tariff levels and preferential (lower) rates under the FTA) the most affected. In addition, the agreement would provide lower cost access to intermediate goods in both the EU and Japan, which could have longer term effects on supply chains and multinational firms' decisions on production locations.

|

Figure 2. U.S., EU, and Japanese Goods Trade |

|

|

Source: IMF Direction of Trade Statistics. Note: Data reported by exporting country. |

Strategic Implications/Rule-writing. The Obama Administration cast TPP and T-TIP as an opportunity to lead in setting global trade rules with like-minded trading partners. With the U.S. withdrawal from TPP and the stalled T-TIP negotiations, the EU-Japan FTA, which includes two of the world's four largest exporters and importers and largest U.S. trading partners (Table 1), presents strategic questions regarding U.S. ability to shape international trade norms. For example, on regulatory issues, an EU-Japan FTA could make the EU's precautionary principle approach more dominant than the U.S. risk-based approach. Many U.S. businesses oppose the EU push to expand GI protections, viewing it as a constraint on using generic food names. The absence of data flow commitments in the agreement contrasts the U.S. approach to data provisions in the TPP, which many stakeholders in the United States continue to support. The EU's Investment Court System also differs from ISDS; while the subject of contentious debate in the United States, ISDS has been the system historically favored by the U.S. government for resolving investor-state disputes.

Table 1. Top World Exporters and Importers

(billions of dollars)

|

World Merchandise Trade |

World Commercial Services trade |

||||||

|

Exports (share) |

Imports (share) |

Exports (share) |

Imports (share) |

||||

|

China |

2,275 (17%) |

U.S. |

2,308 (17%) |

EU-28 |

915 (25%) |

EU-28 |

732 (20%) |

|

EU-28 |

1,985 (15%) |

EU-28 |

1,914 (14%) |

U.S. |

690 (19%) |

U.S. |

469 (13%) |

|

U.S. |

1,505 (12%) |

China |

1,682 (13%) |

China |

285 (8%) |

China |

466 (13%) |

|

Japan |

625 (5%) |

Japan |

648 (5%) |

Japan |

158 (4%) |

Japan |

174 (5%) |

Source: WTO World Trade Statistical Review, 2016.

Notes: Excludes intra-EU trade.