The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) entered into force on January 1, 1994. The agreement was signed by President George H. W. Bush on December 17, 1992, and approved by Congress on November 20, 1993. The NAFTA Implementation Act was signed into law by President William J. Clinton on December 8, 1993 (P.L. 103-182). The overall economic impact of NAFTA is difficult to measure since trade and investment trends are influenced by numerous other economic variables, such as economic growth, inflation, and currency fluctuations. The agreement likely accelerated and also locked in trade liberalization that was already taking place in Mexico, but many of these changes may have taken place without an agreement. Nevertheless, NAFTA is significant, because it was the most comprehensive free trade agreement (FTA) negotiated at the time and contained several groundbreaking provisions. A legacy of the agreement is that it has served as a template or model for the new generation of FTAs that the United States later negotiated, and it also served as a template for certain provisions in multilateral trade negotiations as part of the Uruguay Round.

The 115th Congress faces numerous issues related to NAFTA and international trade. On May 18, 2017, the Trump Administration sent a 90-day notification to Congress of its intent to begin talks with Canada and Mexico to renegotiate NAFTA, as required by the 2015 Trade Promotion Authority (TPA). The Administration also began consulting with Members of Congress on the scope of the negotiations. Alternatively President Trump, at times, has threatened to withdraw from the agreement without satisfactory results. Congress may wish to consider the ramifications of renegotiating or withdrawing from NAFTA and how it may affect the U.S. economy and foreign relations with Mexico and Canada. It may also wish to examine the congressional role in a possible renegotiation, as well as the negotiating positions of Canada and Mexico. Mexico has stated that, if NAFTA is reopened, it may seek to broaden negotiations to include security, counter-narcotics, and transmigration issues. Mexico has also indicated that it may choose to withdraw from the agreement if the negotiations are not favorable to the country. Congress may also wish to address issues related to the U.S. withdrawal from the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) free trade agreement among the United States, Canada, Mexico, and 9 other countries. Some observers contend that the withdrawal from TPP could damage U.S. competitiveness and economic leadership in the region, while others see the withdrawal as a way to prevent lower cost imports and potential job losses. Key provisions in TPP may also be addressed in “modernizing” or renegotiating NAFTA, a more than two decade-old FTA.

NAFTA was controversial when first proposed, mostly because it was the first FTA involving two wealthy, developed countries and a developing country. The political debate surrounding the agreement was divisive with proponents arguing that the agreement would help generate thousands of jobs and reduce income disparity in the region, while opponents warned that the agreement would cause huge job losses in the United States as companies moved production to Mexico to lower costs. In reality, NAFTA did not cause the huge job losses feared by the critics or the large economic gains predicted by supporters. The net overall effect of NAFTA on the U.S. economy appears to have been relatively modest, primarily because trade with Canada and Mexico accounts for a small percentage of U.S. GDP. However, there were worker and firm adjustment costs as the three countries adjusted to more open trade and investment.

The rising number of bilateral and regional trade agreements throughout the world and the rising presence of China in Latin America could have implications for U.S. trade policy with its NAFTA partners. Some proponents of open and rules-based trade contend that maintaining NAFTA or deepening economic relations with Canada and Mexico will help promote a common trade agenda with shared values and generate economic growth. Some opponents argue that the agreement has caused worker displacement, and renegotiation could cause further job losses.

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Market Opening Prior to NAFTA

- The U.S.-Canada Free Trade Agreement of 1989

- Mexico's Pre-NAFTA Unilateral Trade Liberalization

- Overview of NAFTA Provisions

- Removal of Trade Barriers

- Tariff Changes

- Trade Barrier Removal by Industry

- Services Trade Liberalization

- Other Provisions

- NAFTA Side Agreements on Labor and the Environment

- Trade Trends and Economic Effects

- U.S. Trade Trends with NAFTA Partners

- Overall Trade

- Trade Balance and Petroleum Oil Products

- Trade by Product

- Trade with Canada

- Trade with Mexico

- Effect on the U.S. Economy

- U.S. Industries and Supply Chains

- Auto Sector

- Effect on Mexico

- U.S.-Mexico Trade Market Shares

- U.S. and Mexican Foreign Direct Investment

- Income Disparity

- Effect on Canada

- U.S.-Canada Trade Market Shares

- Foreign Direct Investment

- Procedures for NAFTA Renegotiation or Withdrawal

- Renegotiation

- Withdrawal

- Issues for Congress

- Potential Topics for Prospective NAFTA Renegotiation

- Automotive Sector

- Services

- E-Commerce, Data Flows, and Data Localization

- Intellectual Property Rights (IPR)

- State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs)

- Investment

- Dispute Settlement

- Labor

- Environment

- Energy

- Customs and Trade Facilitation

- Sanitary and Phytosanitary Standards (SPS)

- Issues Specific to Mexico

- Issues Specific to Canada

- North American Supply Chains

- Trans-Pacific Partnership Withdrawal

Figures

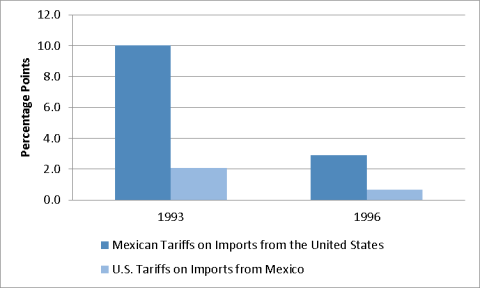

- Figure 1. Average Applied Tariff Levels in Mexico and the United States (1993 and 1996)

- Figure 2. U.S. Merchandise Trade with NAFTA Partners: 1993-2016

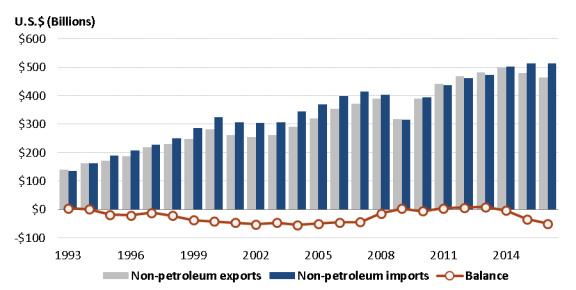

- Figure 3. Trade with NAFTA Partners Excluding Petroleum Oil and Oil Products: 1993-2016

- Figure 4. Top Five U.S. Import and Export Items to and from NAFTA Partners

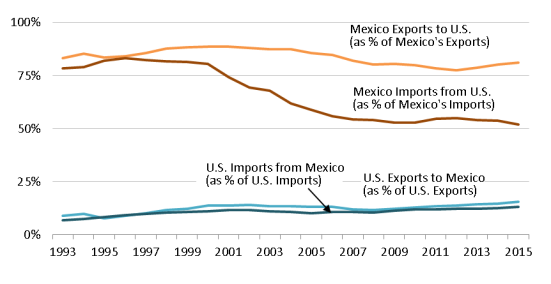

- Figure 5. Market Share as Percentage of Total Trade: Mexico and the United States

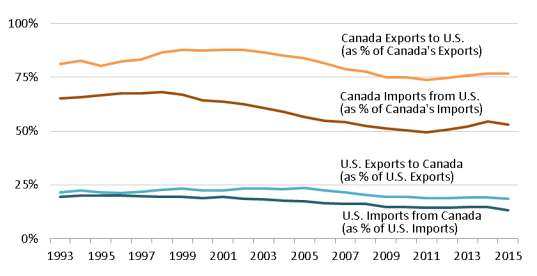

- Figure 6. Market Share as Percentage of Total Trade: Canada and the United States

Tables

- Table 1. U.S. Trade in Motor Vehicles and Parts: 1993 and 2016

- Table A-1. U.S. Merchandise Trade with NAFTA Partners

- Table A-2. U.S. Private Services Trade with NAFTA Partners

- Table A-3. U.S. Trade with NAFTA Partners by Major Product Category: 2016

- Table A-4. U.S. Foreign Direct Investment Positions with Canada and Mexico

Summary

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) entered into force on January 1, 1994. The agreement was signed by President George H. W. Bush on December 17, 1992, and approved by Congress on November 20, 1993. The NAFTA Implementation Act was signed into law by President William J. Clinton on December 8, 1993 (P.L. 103-182). The overall economic impact of NAFTA is difficult to measure since trade and investment trends are influenced by numerous other economic variables, such as economic growth, inflation, and currency fluctuations. The agreement likely accelerated and also locked in trade liberalization that was already taking place in Mexico, but many of these changes may have taken place without an agreement. Nevertheless, NAFTA is significant, because it was the most comprehensive free trade agreement (FTA) negotiated at the time and contained several groundbreaking provisions. A legacy of the agreement is that it has served as a template or model for the new generation of FTAs that the United States later negotiated, and it also served as a template for certain provisions in multilateral trade negotiations as part of the Uruguay Round.

The 115th Congress faces numerous issues related to NAFTA and international trade. On May 18, 2017, the Trump Administration sent a 90-day notification to Congress of its intent to begin talks with Canada and Mexico to renegotiate NAFTA, as required by the 2015 Trade Promotion Authority (TPA). The Administration also began consulting with Members of Congress on the scope of the negotiations. Alternatively President Trump, at times, has threatened to withdraw from the agreement without satisfactory results. Congress may wish to consider the ramifications of renegotiating or withdrawing from NAFTA and how it may affect the U.S. economy and foreign relations with Mexico and Canada. It may also wish to examine the congressional role in a possible renegotiation, as well as the negotiating positions of Canada and Mexico. Mexico has stated that, if NAFTA is reopened, it may seek to broaden negotiations to include security, counter-narcotics, and transmigration issues. Mexico has also indicated that it may choose to withdraw from the agreement if the negotiations are not favorable to the country. Congress may also wish to address issues related to the U.S. withdrawal from the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) free trade agreement among the United States, Canada, Mexico, and 9 other countries. Some observers contend that the withdrawal from TPP could damage U.S. competitiveness and economic leadership in the region, while others see the withdrawal as a way to prevent lower cost imports and potential job losses. Key provisions in TPP may also be addressed in "modernizing" or renegotiating NAFTA, a more than two decade-old FTA.

NAFTA was controversial when first proposed, mostly because it was the first FTA involving two wealthy, developed countries and a developing country. The political debate surrounding the agreement was divisive with proponents arguing that the agreement would help generate thousands of jobs and reduce income disparity in the region, while opponents warned that the agreement would cause huge job losses in the United States as companies moved production to Mexico to lower costs. In reality, NAFTA did not cause the huge job losses feared by the critics or the large economic gains predicted by supporters. The net overall effect of NAFTA on the U.S. economy appears to have been relatively modest, primarily because trade with Canada and Mexico accounts for a small percentage of U.S. GDP. However, there were worker and firm adjustment costs as the three countries adjusted to more open trade and investment.

The rising number of bilateral and regional trade agreements throughout the world and the rising presence of China in Latin America could have implications for U.S. trade policy with its NAFTA partners. Some proponents of open and rules-based trade contend that maintaining NAFTA or deepening economic relations with Canada and Mexico will help promote a common trade agenda with shared values and generate economic growth. Some opponents argue that the agreement has caused worker displacement, and renegotiation could cause further job losses.

Introduction

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) has been in effect since January 1, 1994. NAFTA was signed by President George H. W. Bush on December 17, 1992, and approved by Congress on November 20, 1993. The NAFTA Implementation Act was signed into law by President William J. Clinton on December 8, 1993 (P.L. 103-182). NAFTA continues to be of interest to Congress because of the importance of Canada and Mexico as trading partners, and because of the implications NAFTA has for U.S. trade policy under the Administration of President Donald J. Trump. During his election campaign, President Trump stated his desire to renegotiate NAFTA and that he would examine the ramifications of withdrawing from the agreement once he entered into office. He has also raised the possibility of imposing tariffs or a border tax on products from Mexico. This report provides an overview of North American market-opening provisions prior to NAFTA, provisions of the agreement, economic effects, and policy considerations.

On May 18, 2017, the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) sent the 90-day notification to Congress of its intent to begin talks with Canada and Mexico to renegotiate the NAFTA, as required by the 2015 Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) (P.L. 114-26). Some trade issues that Congress may address in regard to NAFTA, and the prospective renegotiation of the agreement, include the economic effects of withdrawing from the agreement, the impact on relations with Canada and Mexico, the demands that Canada and Mexico may bring to the negotiations, and an evaluation of how to "modernize" or renegotiate NAFTA. Another issue relates to the consequences of the U.S. withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a proposed free trade agreement among the United States and 11 other countries, including Canada and Mexico. Some TPP participants support moving forward on a similar agreement without the participation of the United States, which may have implications for U.S. competitiveness in certain markets.1 It also has implications for NAFTA renegotiation as it addressed several new issues not in NAFTA.

Some trade policy experts and economists give credit to NAFTA and other free trade agreements (FTAs) for expanding trade and economic linkages between countries, creating more efficient production processes, increasing the availability of lower-priced consumer goods, and improving living standards and working conditions. Others blame FTAs for disappointing employment trends, a decline in U.S. wages, and for not having done enough to improve labor standards and environmental conditions abroad.

NAFTA influenced other FTAs that the United States later negotiated and also influenced multilateral negotiations. NAFTA initiated a new generation of trade agreements in the Western Hemisphere and other parts of the world, influencing negotiations in areas such as market access, rules of origin, intellectual property rights, foreign investment, dispute resolution, worker rights, and environmental protection. The United States currently has 14 FTAs with 20 countries. As with NAFTA, these trade agreements have often been supported or criticized on similar arguments related to jobs.

Market Opening Prior to NAFTA

The concept of economic integration in North America was not a new one at the time NAFTA negotiations started. In 1911, President William Howard Taft signed a reciprocal trade agreement with Canadian Prime Minister Sir Wilfred Laurier. After a bitter election, Canadians rejected free trade and ousted Prime Minister Laurier, thereby ending the agreement. In 1965, the United States and Canada signed the U.S.-Canada Automotive Products Agreement that liberalized trade in cars, trucks, tires, and automotive parts between the two countries.2 The Auto Pact was credited as a pioneer in creating an integrated North American automotive sector. In the case of Mexico, the government began implementing reform measures in the mid-1980s, prior to NAFTA, to liberalize its economy. By 1990, when NAFTA negotiations began, Mexico had already taken significant steps towards liberalizing its protectionist trade regime.

The U.S.-Canada Free Trade Agreement of 1989

The United States and Canada signed a bilateral free trade agreement (CFTA) on October 3, 1987. The FTA was the first economically significant bilateral FTA signed by the United States.3 Implementing legislation4 was approved by both houses of Congress under "fast-track authority"—now known as trade promotion authority (TPA)—and signed by President Ronald Reagan on September 28, 1988. While the FTA generated significant policy debate in the United States, it was a watershed moment for Canada. Controversy surrounding the proposed FTA led to the so-called "free trade election" in 1988, in which sitting Progressive Conservative Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, who negotiated the agreement, defeated Liberal party leader John Turner, who vowed to reject it if elected. After the election, the FTA was passed by Parliament in December 1988, and it came into effect between the two nations on January 1, 1989. At the time, it probably was the most comprehensive bilateral FTA negotiated worldwide and contained several groundbreaking provisions. The agreement

- Eliminated all tariffs by 1998. Many were eliminated immediately, and the remaining tariffs were phased out in 5-10 years.

- Continued the 1965 U.S.-Canada Auto Pact, but tightened its rules of origin. Some Canadian auto sector practices not covered by the Auto Pact were ended by 1998.

- Provided national treatment for covered services providers and liberalized financial services trade. Facilitated cross-border travel for business professionals.

- Committed to provide prospective national treatment for investment originating in the other countries, although established derogations from national treatment, such as for national security or prudential reasons, were allowed to continue.

- Banned imposition of performance requirements, such as local content, import substitution, or local sourcing requirements.

- Expanded the size of federal government procurement markets available for competitive bidding from suppliers of the other country. It did not include sub-federal government procurement.

- Provided for a binding binational panel to resolve disputes arising from the agreement (a Canadian insistence).

- Prohibited most import and export restrictions on energy products, including minimum export prices. This was carried forth in NAFTA only with regard to Canada-U.S. energy trade.

Many of these provisions were incorporated into, or expanded in, NAFTA. However, the FTA did not include, or specifically exempted, some issues that would appear in NAFTA for the first time. These include

- Intellectual property rights (IPR). The FTA did not contain language on intellectual property rights. NAFTA was the first FTA to include meaningful disciplines on IPR.

- Cultural exemption. It exempted the broadcasting, film, and publishing sectors. This exemption continues in NAFTA, due to Canadian concerns.

- Transportation services and investment in the Canadian energy sector were excluded from the FTA. These exclusions were limited in NAFTA.

- Trade remedies. Neither the FTA nor NAFTA ended the use of trade remedy actions (anti-dumping, countervailing duty, or safeguards) against the other. This was a key Canadian goal of the FTA. NAFTA did create a separate dispute settlement mechanism to review national decisions on trade remedy decisions, but this mechanism has not been replicated in other FTAs.

- Softwood lumber. The FTA grandfathered in the then-present 1986 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) governing softwood lumber trade. However, it did not permanently settle the softwood lumber issue. Since then, the MOU has been replaced by other agreements, and, at times, by resort to trade remedy actions.

- Agricultural supply management. Canada was able to exempt its agriculture supply management system, although it committed to allow a small increase in imports of dairy, poultry, and eggs, which carried over into the NAFTA.

Mexico's Pre-NAFTA Unilateral Trade Liberalization

Well before NAFTA negotiations began, Mexico was liberalizing its protectionist trade and investment policies that had been in place for decades (see page 9 of this report). The restrictive trade regime began after Mexico's revolutionary period and remained until the early- to mid-1980s when the country was facing a debt crisis. It was at this time that the government took unilateral steps to open and modernize its economy by relaxing investment policies and liberalizing trade barriers. The trade liberalization measures that began in the mid-1980s shifted Mexico from one of the world's most protected economies into one of the most open. Mexico now has 12 FTAs involving 46 countries.5

Mexico's first steps in opening its closed economy focused on reforming its import substitution policies in the mid-1980s. Further reforms were made in 1986 when Mexico became a member of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). As a condition of becoming a GATT member, for example, Mexico agreed to lower its maximum tariff rates to 50%. Mexico went further by reducing its highest tariff rate from 100% to 20%. Mexico's trade-weighted average tariff fell from 25% in 1985 to about 19% in 1989.6

Although Mexico had been lowering trade and investment restrictions since 1986, the number of remaining barriers for U.S. exports remained high at the time of the NAFTA negotiations. Mexico required import licenses on 230 products from the United States, affecting about 7% of the value of U.S. exports to Mexico. Prior to its entry into GATT, Mexico required import licenses on all imports. At the time of the NAFTA negotiations, about 60% of U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico required import licenses. Mexico also had numerous other nontariff barriers, such as "official import prices," an arbitrary customs valuation system that raised duty assessments.7

For Mexico, an FTA with the United States represented a way to lock in the reforms of its market opening measures from the mid-1980s to transform Mexico's formerly statist economy after the devastating debt crisis of the 1980s.8 The combination of the severe economic impact of the debt crisis, low domestic savings, and an increasingly overvalued peso put pressure on the Mexican government to adopt market-opening economic reforms and boost imports of goods and capital to encourage more competition in the Mexican market. An FTA with the United States was a way of blocking domestic efforts to roll back Mexican reforms, especially in the politically sensitive agriculture sector. NAFTA helped deflect protectionist demands of industrial groups and special interest groups in Mexico.9 One of the main goals of the Mexican government was to increase investment confidence in order to attract greater flows of foreign investment and spur economic growth. Since the entry into force of NAFTA, Mexico has used the agreement as a basic model for other FTAs Mexico has signed with other countries.10

For the United States, NAFTA represented an opportunity to expand the growing export market to the south, but it also represented a political opportunity for the United States and Mexico to work together in resolving some of the tensions in the bilateral relationship.11 An FTA with Mexico would help U.S. businesses expand exports to a growing market of 100 million people. U.S. officials also recognized that imports from Mexico would likely include higher U.S. content than imports from Asian countries. In addition to the trade and investment opportunities that NAFTA represented, an agreement with Mexico would be a way to support the growth of political pluralism and a deepening of democratic processes in Mexico. NAFTA also presented an opportunity for the United States to spur the slow progress on the Uruguay Round of multilateral trade negotiations.12

Overview of NAFTA Provisions

At the time that NAFTA was implemented, the U.S.-Canada FTA was already in effect and U.S. tariffs on most Mexican goods were low, while Mexico had the highest protective trade barriers. Under the agreement, the United States and Canada gained greater access to the Mexican market, which was the fastest growing major export market for U.S. goods and services at the time.13 NAFTA also opened up the U.S. market to increased imports from Mexico and Canada, creating one of the largest single markets in the world. Some of the key NAFTA provisions included tariff and non-tariff trade liberalization, rules of origin, services trade, foreign investment, intellectual property rights protection, government procurement, and dispute resolution. Labor and environmental provisions were included in separate NAFTA side agreements.

Removal of Trade Barriers

The market opening provisions of the agreement gradually eliminated all tariffs and most non-tariff barriers on goods produced and traded within North America over a period of 15 years after it entered into force. Some tariffs were eliminated immediately, while others were phased out in various schedules of 5 to 15 years. Most tariffs were phased out within 10 years. U.S. import-sensitive sectors, such as glassware, footwear, and ceramic tile, received longer phase-out schedules.14 NAFTA provided the option of accelerating tariff reductions if the countries involved agreed.15 The agreement included safeguard provisions in which the importing country could increase tariffs, or impose quotas in some cases, on imports during a transition period if domestic producers faced serious injury as a result of increased imports from another NAFTA country. It terminated all existing drawback programs by January 1, 2001.16

Tariff Changes

Most of the market opening measures from NAFTA resulted in the removal of tariffs and quotas applied by Mexico on imports from the United States and Canada. Because Mexican tariffs were substantially higher than those of the United States, it was expected that the agreement would cause U.S. exports to expand more quickly than imports from Mexico. The average applied U.S. duty for all imports from Mexico was 2.07% in 1993.17 Moreover, many Mexican products entered the United States duty-free under the U.S. Generalized System of Preferences (GSP). In 1993, over 50% of U.S. imports from Mexico entered the United States duty-free. In contrast, the United States faced considerably higher tariffs, in addition to substantial non-tariff barriers, on exports to Mexico. In 1993, Mexico's average tariffs on all imports from the United States was 10% (Canada's was 0.37%).18 In agriculture, Mexico's trade-weighted tariff on U.S. products averaged about 11%. Also affecting U.S.-Mexico trade were both countries' sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) rules, Mexican import licensing requirements, and U.S. marketing orders.19

Trade Barrier Removal by Industry

Some of the more significant changes took place in the textiles, apparel, automotive, and agricultural industries. Elimination of trade barriers in these key industries are summarized below.

- Textiles and Apparel Industries. NAFTA phased out all duties on textile and apparel goods within North America meeting specific NAFTA rules of origin20 over a 10-year period. Prior to NAFTA, 65% of U.S. apparel imports from Mexico entered duty-free and quota-free, and the remaining 35% faced an average tariff rate of 17.9%. Mexico's average tariff on U.S. textile and apparel products was 16%, with duties as high as 20% on some products.21

- Automotive Industry. NAFTA phased out Mexico's restrictive auto decree. It phased out all U.S. tariffs on imports from Mexico and Mexican tariffs on U.S. and Canadian products as long as they met the rules of origin requirements of 62.5% North American content for autos, light trucks, engines and transmissions; and 60% for other vehicles and automotive parts. Some tariffs were eliminated immediately, while others were phased out in periods of 5 to 10 years. Prior to NAFTA, the United States assessed the following tariffs on imports from Mexico: 2.5% on automobiles, 25% on light-duty trucks, and a trade-weighted average of 3.1% for automotive parts. Mexican tariffs on U.S. and Canadian automotive products were as follows: 20% on automobiles and light trucks, and 10%-20% on auto parts.22

- Agriculture. NAFTA set out separate bilateral undertakings on cross-border trade in agriculture, one between Canada and Mexico, and the other between Mexico and the United States. As a general matter, U.S.-Canada FTA provisions continued to apply on trade with Canada.23 Regarding U.S.-Mexico agriculture trade, NAFTA eliminated most non-tariff barriers in agricultural trade, either through their conversion to tariff-rate quotas (TRQs)24 or ordinary tariffs. Tariffs were phased out over a period of 15 years with sensitive products such as sugar and corn receiving the longest phase-out periods. Approximately one-half of U.S.-Mexico agricultural trade became duty-free when the agreement went into effect. Prior to NAFTA, most tariffs, on average, in agricultural trade between the United States and Mexico were fairly low though some U.S. exports to Mexico faced tariffs as high as 12%. However, approximately one-fourth of U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico (by value) were subjected to restrictive import licensing requirements.25

Services Trade Liberalization

NAFTA services provisions established a set of basic rules and obligations in services trade among partner countries. The agreement expanded on provisions in the U.S.-Canada FTA and in the then-negotiation in the Uruguay Round of multilateral trade negotiations to create internationally agreed disciplines on government regulation of trade in services.26 The agreement granted services providers certain rights concerning nondiscriminatory treatment, cross-border sales and entry, investment, and access to information. However, there were certain exclusions and reservations by each country. These included maritime shipping (United States), film and publishing (Canada), and oil and gas drilling (Mexico).27 Although NAFTA liberalized certain service sectors in Mexico, particularly financial services, which profoundly altered its banking sector, other sectors were barely affected.28 In telecommunications services, NAFTA partners agreed to exclude provision of, but not the use of, basic telecommunications services. NAFTA granted a "bill of rights" for the providers and users of telecommunications services, including access to public telecommunications services; connection to private lines that reflect economic costs and available on a flat-rate pricing basis; and the right to choose, purchase, or lease terminal equipment best suited to their needs.29 However, NAFTA did not require parties to authorize a person of another NAFTA country to provide or operate telecommunications transport networks or services. NAFTA did not bar a party from maintaining a monopoly provider of public networks or services, such as Telmex, Mexico's dominant telecommunications company.30

Other Provisions

In addition to market opening measures through the elimination of tariff and non-tariff barriers, NAFTA incorporated numerous other provisions to establish rules or achieve greater market access on foreign investment, intellectual property rights (IPR), dispute resolution, and government procurement.

- Foreign Investment. NAFTA removed significant investment barriers, ensured basic protections for NAFTA investors, and provided a mechanism for the settlement of disputes between investors and a NAFTA country. NAFTA provided for "non-discriminatory treatment" for foreign investment by NAFTA parties in certain sectors of other NAFTA countries. The agreement included country-specific liberalization commitments and exceptions to national treatment. Exemptions from NAFTA investment provisions included the energy sector in Mexico, in which the Mexican government reserved the right to prohibit foreign investment. It also included exceptions related to national security and to Canada's cultural industries.31

- IPR. NAFTA built upon the then-ongoing Uruguay Round negotiations that would create the Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement in the World Trade Organization and on various existing international intellectual property treaties. The agreement set out specific enforceable commitments by NAFTA parties regarding the protection of copyrights, patents, trademarks, and trade secrets, among other provisions.

- Dispute Settlement Procedures. NAFTA's provisions for preventing and settling disputes were built upon provisions in the U.S.-Canada FTA. NAFTA created a system of arbitration for resolving disputes that included initial consultations, taking the issue to the NAFTA Trade Commission, or going through arbitral panel proceedings.32 NAFTA included separate dispute settlement provisions for addressing disputes over antidumping and countervailing duty determinations.

- Government Procurement. NAFTA opened up a significant portion of federal government procurement in each country on a nondiscriminatory basis to suppliers from other NAFTA countries for goods and services. It contains some limitations for procurement by state-owned enterprises.33

|

Mexico's Protectionist Trade/Investment Policies Prior to NAFTA For decades prior to NAFTA, Mexico relied on protectionist trade and investment policies that were intended to help foster domestic growth and to protect itself from a perceived risk of foreign domination, but that failed to achieve the intended outcomes. State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs). Strong state presence prior to NAFTA. During the late 1950s and 1960s, the number of state-owned enterprises almost doubled. By 1982, the number of SOEs had grown to more than 1,000. Starting in 1983, economic reforms and divestiture of the state-owned sector significantly decreased the number of SOEs (down to 210 by 2003). Import Licenses. In the early 1980s, import licenses were required on most, if not all, imports. In the mid-1980s, the government began to phase these out. By the time NAFTA negotiations started, import licenses were required on only 230 products of the nearly 12,000 items in the Mexican tariff schedule. Agricultural Products. Prior to NAFTA, 60% of U.S. agricultural exports to Mexico required import licenses or faced other nontariff barriers. There was also a lack of transparency of procedures through which exporters to Mexico could apply for the proper license, certificate, or test. Foreign Investment Restrictions. Mexico's restrictive Law to Promote Mexican Investment and Regulate Foreign Investment restricted U.S. investment in Mexico. In 1991, about a third of Mexican economic activity was not open to majority foreign ownership. Auto Industry Import Substitution Policy (Auto Decrees). Mexico had a restrictive import substitution policy that began in the 1960s through a series of Mexican Auto Decrees in which the government sought to supply the entire Mexican market through domestically-produced automotive goods. The decrees established high import tariffs and had high restrictions on auto production by foreign companies. Restrictions in Agricultural Production. In the period after the 1910 revolution and until the 1980s, Mexico had a land distribution system in which land was redistributed from wealthy land owners and managed by the government. This ejido system, formed under Mexico's Agrarian Law, changed in the 1980s when the government began to implement agricultural and trade policy reform measures. Changes included the privatization of the ejido system in order to stimulate competition. Mexico's unilateral reform measures included eliminating state enterprises related to agriculture and removing staple price supports and subsidies. Mexico also had a government agency known as CONASUPO which intervened in the agriculture sector. The agency bought staples from farmers at guaranteed prices and processed the products or sold them at low prices to processors and consumers. Many of Mexico's domestic reforms in agriculture coincided with NAFTA negotiations, beginning in 1991, and continued beyond the implementation of NAFTA in 1994. The unilateral reforms in the agricultural sector make it difficult to separate those effects from the effects of NAFTA. By 1999, CONASUPO had been abolished. Sources: United States International Trade Commission (USITC), The Likely Impact on the United States of a Free Trade Agreement with Mexico, Publication 2353, February 1991.Gary Clyde Hufbauer and Jeffrey J. Schott, Institute for International Economics, NAFTA Revisited, October 2005. Alberto Chong and Florencio López-de-Silanes, Privatization in Mexico, Inter-American Development Bank, Working Paper #513, August 2004. |

NAFTA Side Agreements on Labor and the Environment

The NAFTA text did not include labor or environmental provisions, which was a major concern to many in Congress at the time of the agreement's consideration. Some policymakers called for additional provisions to address numerous concerns about labor and environmental issues, specifically in Mexico. Other policymakers argued that the economic growth generated by the FTA would increase Mexico's resources available for environmental and worker rights protection. However, congressional concerns from policymakers, as well as criticisms from labor and environmental groups, remained strong.

Shortly after he began his presidency, President Clinton addressed labor and environmental issues by joining his counterparts in Canada and Mexico in negotiating formal side agreements. The NAFTA implementing legislation included provisions on the side agreements, authorizing U.S. participation in NAFTA labor and environmental commissions and appropriations for these activities. The North American Agreement on Labor Cooperation (NAALC) and the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation (NAAEC) entered into force on January 1, 1994, the same day as NAFTA.34 NAFTA implementing legislation also included two adjustment assistance programs, designed to ease trade-related labor and firm adjustment pressures: the NAFTA Transitional Adjustment Assistance (NAFTA-TAA) Program and the U.S. Community Adjustment and Investment Program (USCAIP).

The labor and environmental side agreements included language to promote cooperation on labor and environmental matters as well as provisions to address a party's failure to enforce its own labor and environmental laws. Perhaps most notable were the side agreements' dispute settlement processes that, as a last resort, may impose monetary assessments and sanctions to address a party's failure to enforce its laws.35 NAFTA marked the first time that labor and environmental provisions were associated with an FTA. For many, it represented an opportunity for cooperating on environmental and labor matters across borders and for establishing a new type of relationship among NAFTA partners.36

In addition to the two trilateral side agreements, the United States and Mexico entered into a bilateral side agreement to NAFTA on border environmental cooperation.37 In this agreement, the two governments committed to cooperate on developing environmental infrastructure projects along the U.S.-Mexico border to address problems regarding the degradation of the environment due to increased economic activity. The agreement established two organizations to work on these issues: the Border Environment Cooperation Commission (BECC), located in Juárez, Mexico, and the North American Development Bank (NADBank), located in San Antonio, Texas. The sister organizations work closely together and with other partners at the federal, state and local level in the United States and Mexico to develop, certify, and facilitate financing for water and wastewater treatment, municipal solid waste disposal, and related projects on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border region. These projects have provided border residents with more access to drinking water, sewer and wastewater treatment. In December 2014, the Board of NADBank and BECC approved a merger of the two organizations, which has not been completed as of the date of this report.38

Trade Trends and Economic Effects

Most economists contend that trade liberalization promotes overall economic growth and efficiency among trading partners, although there are short-term adjustment costs. NAFTA was unusual in global terms because it was the first time that an FTA linked two wealthy, developed countries with a low-income developing country. For this reason, the agreement received considerable attention by U.S. policymakers, manufacturers, service providers, agriculture producers, labor unions, non-government organizations, and academics. Proponents argued that the agreement would help generate thousands of jobs and reduce income disparity between Mexico and its northern neighbors. Opponents warned that the agreement would create huge job losses in the United States as companies moved production to Mexico to lower costs.39

Estimating the economic impact of trade agreements is a daunting task due to a lack of data and important theoretical and practical matters associated with generating results from economic models. In addition, such estimates provide an incomplete accounting of the total economic effects of trade agreements.40 Numerous studies suggest that NAFTA achieved many of the intended trade and economic benefits.41 Other studies suggest that NAFTA has come at some cost to U.S. workers.42 This has been in keeping with what most economists maintain, that trade liberalization promotes overall economic growth among trading partners, but that there are both winners and losers from adjustments.

Not all changes in trade and investment patterns within North America since 1994 can be attributed to NAFTA because trade has also been affected by a number of factors. The sharp devaluation of the peso at the end of the 1990s and the associated recession in Mexico had considerable effects on trade, as did the rapid growth of the U.S. economy during most of the 1990s and, in later years, the economic slowdown caused by the 2008 financial crisis. Trade-related job gains and losses since NAFTA may have accelerated trends that were ongoing prior to NAFTA and may not be totally attributable to the trade agreement.

U.S. Trade Trends with NAFTA Partners

Overall Trade

U.S. trade with its NAFTA partners has more than tripled since the agreement took effect. It has increased more rapidly than trade with the rest of the world. Since 1993, trade with Mexico grew faster than trade with Canada or with non-NAFTA countries. In 2011, trilateral trade among NAFTA partners reached the $1 trillion threshold. In 2016, Canada was the leading market for U.S. exports, while Mexico ranked second. The two countries accounted for 34% of total U.S. exports in 2016. In imports, Canada and Mexico ranked second and third, respectively, as suppliers of U.S. imports in 2016. The two countries accounted for 26% of U.S. imports.43

Most of the trade-related effects of NAFTA may be attributed to changes in trade and investment patterns with Mexico because economic integration between Canada and the United States had already been taking place. As mentioned previously, while NAFTA may have accelerated U.S.-Mexico trade since 1993, other factors, such as economic growth patterns, also affected trade. As trade tends to increase during cycles of economic growth, it tends to decrease as growth declines. The economic downturns in 2001 and 2009, for example, likely played a role in the decline in both U.S. exports to and imports from Canada and Mexico, as shown in Figure 2.

|

Figure 2. U.S. Merchandise Trade with NAFTA Partners: 1993-2016 (billions of nominal dollars) |

|

|

Source: Compiled by CRS using trade data from the U.S. International Trade Commission's Interactive Tariff and Trade Data Web, at http://dataweb.usitc.gov. |

Trade Balance and Petroleum Oil Products

Trade in crude oil and petroleum products is a central component of U.S. trade with both Canada and Mexico. If these products are excluded from the trade balance, the deficit with NAFTA partners has been lower than the overall deficit in some years. In some years, the balance in non-energy merchandise has been positive. For example, the balance in non-petroleum products went from a surplus of $8.7 billion in 2013 to a deficit of $49.8 billion in 2016 as shown in Figure 3. Petroleum products have accounted for 10-17% of total trade with NAFTA partners over the past 10 years.

|

Figure 3. Trade with NAFTA Partners Excluding Petroleum Oil and Oil Products: 1993-2016 (billions of nominal dollars) |

|

|

Source: Compiled by CRS using trade data from the U.S. International Trade Commission's (USITC's) Interactive Tariff and Trade Data Web, at http://dataweb.usitc.gov. Notes: The United States uses different classifications of trade for trade statistics. Trade data in this chart excludes energy trade in three categories: Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) code 2709, petroleum oils and oils from bituminous minerals, crude; HTS code 2710, petroleum oils and oils from bituminous minerals (other than crude) and products therefrom, NESOI, containing 70% (by weight) or more of these oils; and HTS code 2711, petroleum gases and other gaseous hydrocarbons. See http://dataweb.usitc.gov. |

Trade by Product

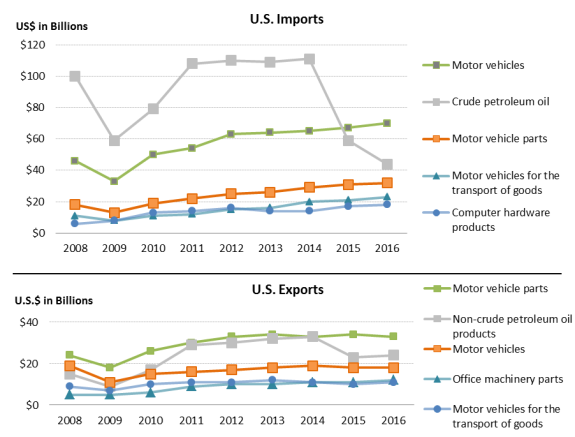

In 2016, U.S. imports in motor vehicles ranked first among the five leading import items from NAFTA partners, as shown in Figure 4.44 The next leading import items were crude petroleum oil, motor vehicle parts, motor vehicles for the transport of goods, and computer hardware. In 2016, the top five U.S. export items to NAFTA partners were motor vehicle parts, non-crude petroleum oil products (mainly gasoline), motor vehicles, office machinery parts, and motor vehicles for the transport of goods, as shown in Figure 4.

|

Figure 4. Top Five U.S. Import and Export Items to and from NAFTA Partners (billions of nominal dollars) |

|

|

Source: Compiled by CRS using trade data from the USITC at http://dataweb.usitc.gov. Notes: This figure does not include low-value export shipments. Statistics are derived from the harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) of the United States at the 4-digit level. The HTS comprises a hierarchical structure for describing all goods in trade for duty, quota, and statistical purposes. This structure is based on the international Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System (HS), administered by the World Customs Organization in Brussels. |

Trade with Canada

U.S. trade with Canada more than doubled in the first decade of the FTA/NAFTA (1989-1999) from $166.5 billion to $362.2 billion. U.S. exports to Canada increased from $100.2 billion in 1993 to $312.1 billion in 2014, and then decreased to $266.8 billion in 2016. U.S. imports from Canada increased from $110.9 billion in 1993 to $349.3 billion in 2014, and then decreased to $278.1 billion in 2016 (see Table A-1). After falling off during the recession of 2001, total trade with Canada reached a new high of $600.6 billion in 2008, only to fall victim to the financial crisis in 2009 when it fell to $430.9 billion. The United States has run a trade deficit with Canada since the FTA/NAFTA era, increasing from $9.9 billion in 1989 to $78.3 billion in 2008, before falling back during the 2009 recession. In 2016, the trade deficit with Canada decreased further to $11.2 billion. While the trade deficit with Canada has been attributed to the FTA/NAFTA, increases have been uneven and may also be attributed to other economic factors, such as energy prices.45

In services, the United States had a surplus of $27.4 billion in 2015 in trade with Canada. U.S. private services exports to Canada increased from $17.0 billion in 1993 to $56.4 billion in 2015. U.S. private services imports from Canada increased from $9.1 billion in 1993 to $29.0 billion in 2015, as shown in Table A-2.46

Trade with Mexico

The United States is, by far, Mexico's leading partner in merchandise trade. U.S. exports to Mexico increased rapidly since NAFTA, increasing from $41.6 billion in 1993 to $231.0 billion in 2016, an increase of 455% (see Table A-1). U.S. imports from Mexico increased from $39.9 billion in 1993 to $294.2 billion in 2016, an increase of 637%. The trade balance with Mexico went from a surplus of $1.7 billion in 1993 to a deficit of $74.8 billion in 2007. Since then, the trade deficit with Mexico has fallen to $63.2 billion in 2016.47

In services, the United States had a surplus of $9.6 billion in 2016 in trade with Mexico. U.S. private services exports to Mexico increased from $10.4 billion in 1993 to $31.5 billion in 2015. U.S. private services imports from Mexico increased from $7.4 billion in 1993 to $21.9 billion in 2015, as shown in Table A-2.48

Effect on the U.S. Economy

The overall net effect of NAFTA on the U.S. economy has been relatively small, primarily because total trade with both Mexico and Canada was equal to less than 5% of U.S. GDP at the time NAFTA went into effect. Because many, if not most, of the economic effects came as a result of U.S.-Mexico trade liberalization, it is also important to take into account that two-way trade with Mexico was equal to an even smaller percentage of GDP (1.4%) in 1994. Thus, any changes in trade patterns would not be expected to be significant in relation to the overall U.S. economy. A major challenge in assessing NAFTA is separating the effects that came as a result of the agreement from other factors. U.S. trade with Mexico and Canada was already growing prior to NAFTA and it likely would have continued to do so without an agreement. A 2003 report by the Congressional Budget Office observed that it was difficult to precisely measure the effects of NAFTA. It estimated that NAFTA likely increased annual U.S. GDP, but by a very small amount—"probably no more than a few billion dollars, or a few hundredths of a percent."49 In some sectors, trade-related effects could have been more significant, especially in those industries that were more exposed to the removal of tariff and non-tariff trade barriers, such as the textile, apparel, automotive, and agriculture industries.

Studies by the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) on the effects of NAFTA pointed out the difficulty in isolating the agreement's effects from other factors. Although the effects of NAFTA are not easily measured, the USITC provided some estimates over the years. A 2003 study estimated that U.S. GDP could experience an increase between 0.1% and 0.5% upon full implementation of the agreement.50 A more recent USITC report written in June 2016 on the economic impact of trade agreements implemented under Trade Promotion Authority provides a summary of the findings from literature on NAFTA after 2002.51 The report states that, in general, the findings show that NAFTA led "to a substantial increase in trade volumes for all three countries; a small increase in U.S. welfare; and little to no change in U.S. aggregate employment."52 The 2016 USITC report also states that some studies find that trade with Mexico depressed U.S. wages in some industries and states, while wages in other industries increased. According to ITC, other studies show that, in general, NAFTA had "essentially no effect on real wages in the United States of either skilled or unskilled workers."53

U.S. Industries and Supply Chains

Many economists and other observers have credited NAFTA with helping U.S. manufacturing industries, especially the U.S. auto industry, become more globally competitive through greater North American economic integration and the development of supply chains.54 Much of the increase in U.S.-Mexico trade, for example, can be attributed to specialization as manufacturing and assembly plants have reoriented to take advantage of economies of scale. As a result, supply chains have been increasingly crossing national boundaries as manufacturing work is performed wherever it is most efficient.55 A reduction in tariffs in a given sector not only affects prices in that sector but also in industries that purchase intermediate inputs from that sector. The importance of these direct and indirect effects is often overlooked, according to one study. The study suggests that these linkages offer important trade and welfare gains from free trade agreements and that ignoring these input-output linkages could underestimate potential trade gains.56

Much of the trade between the United States and its NAFTA partners occurs in the context of production sharing as manufacturers in each country work together to create goods. The expansion of trade has resulted in the creation of vertical supply relationships, especially along the U.S.-Mexico border. The flow of intermediate inputs produced in the United States and exported to Mexico and the return flow of finished products greatly increased the importance of the U.S.-Mexico border region as a production site.57 U.S. manufacturing industries, including automotive, electronics, appliances, and machinery, all rely on the assistance of Mexican manufacturers. One report estimates that 40% of the content of U.S. imports from Mexico and 25% of the content of U.S. imports from Canada are of U.S. origin. In comparison, U.S. imports from China are said to have only 4% U.S. content. Taken together, goods from Mexico and Canada represent about 75% of all the U.S. domestic content that returns to the United States as imports.58

Auto Sector

NAFTA removed Mexico's protectionist auto decrees and was instrumental in the integration of the auto industry in all three countries. The auto sector experienced some of the most significant changes in trade following the agreement. NAFTA provisions consisted of a phased elimination of tariffs and the gradual removal of many non-tariff barriers to trade. It provided for uniform country of origin provisions, enhanced protection of intellectual property rights, adopted less restrictive government procurement practices, and eliminated performance requirements on investors from other NAFTA countries. U.S. auto manufacturers, such as Ford Motor Company, often rely on parts from the United States, Canada, and Mexico in the final assembly of a motor vehicle. Northern American auto parts producers may use inputs and components produced by another NAFTA partner to assemble parts, which are then shipped to another NAFTA country where they are assembled into a vehicle that is sold in any of the three countries.59 According to some estimates, autos manufactured in North America that are sold in the United States have a domestic content of between 47% and 85%.60

|

Mexico's Restrictive Auto Decrees Prior to NAFTA Beginning in the 1960s, Mexico had a restrictive import substitution policy through a series of Mexican Auto Decrees in which the government sought to supply the entire Mexican market through domestically produced automotive goods. The decrees:

After joining the GATT, the government of Mexico issued the final decree in 1989, liberalizing rules on the industry, but not entirely eliminating them. At the time of NAFTA negotiations, auto manufacturers were still required to have a certain percentage of domestic content in their products and meet export requirements, both of which were considered huge impediments to the industry. In addition, Mexico had tariffs of 20% or more on imports of automobiles and auto parts. These trade restrictions were eliminated under NAFTA. Note: For more information, see Gary Clyde Hufbauer and Jeffrey J. Schott, Institute for International Economics, North American Free Trade, Issues and Recommendations, 1992, pp. 209-234. |

After NAFTA's entry into force, U.S. trade in vehicles and auto parts increased rapidly. Mexico became a more significant trading partner in the motor vehicle market as U.S. auto exports to Mexico increased 262% while imports increased 765% between 1993 and 2016 as shown in Table 1. Mexico's share in U.S. total trade in motor vehicles increased during this time period, while the share from Canada and other countries decreased. Mexico was the leading supplier of automotive goods for the United States in 2016, accounting for 30% ($96.0 billion) of total U.S. motor vehicle and auto parts imports. Canada ranked second, accounting for 19% ($60.7 billion) of total U.S. imports in motor vehicles and auto parts in 2016.61

|

1993 |

2016 |

% Change 1993-2016 |

||||||

|

Exports |

Imports |

Total |

Exports |

Imports |

Total |

Exports |

Imports |

|

|

Mexico |

||||||||

|

Vehicles |

0.2 |

3.7 |

3.9 |

4.6 |

49.7 |

54.3 |

2222% |

1242% |

|

Parts |

7.3 |

7.4 |

14.7 |

22.5 |

46.3 |

68.9 |

209% |

526% |

|

Total |

7.5 |

11.1 |

18.6 |

27.2 |

96.0 |

123.2 |

262% |

765% |

|

Canada |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Vehicles |

8.2 |

26.7 |

34.9 |

26.1 |

46.7 |

72.7 |

218% |

75% |

|

Parts |

18.2 |

10.3 |

28.5 |

26.4 |

14.0 |

40.5 |

45% |

36% |

|

Total |

26.4 |

37.0 |

63.4 |

52.5 |

60.7 |

113.2 |

99% |

64% |

|

World |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

Vehicles |

18.9 |

63.0 |

81.9 |

68.4 |

199.5 |

267.9 |

262% |

217% |

|

Parts |

33.4 |

38.3 |

71.7 |

64.08 |

115.4 |

179.5 |

92% |

201% |

|

Total |

52.3 |

101.3 |

153.6 |

132.5 |

314.9 |

447.4 |

153% |

211% |

Source: Compiled by CRS using trade data from the USITC at http://dataweb.usitc.gov. For 2016, "vehicles" consists of items under the North American Industrial Classification System (NAICS) number 3361 and "parts" consists of items under NAIC number 3363. The NAICS is the standard used by Federal statistical agencies in classifying business establishments for the purpose of collecting, analyzing, and publishing statistical data related to the U.S. business economy.

Effect on Mexico

A number of studies have found that NAFTA has brought economic and social benefits to the Mexican economy as a whole, but that the benefits have not been evenly distributed throughout the country.62 The agreement also had a positive impact on Mexican productivity. A 2011 World Bank study found that the increase in trade integration after NAFTA had a positive effect on stimulating the productivity of Mexican plants.63 Most post-NAFTA studies on economic effects have found that the net overall effects on the Mexican economy tended to be positive but modest. While there have been periods of positive and negative economic growth in Mexico after the agreement was implemented, it is difficult to measure precisely how much of these economic changes was attributed to NAFTA. A World Bank study assessing some of the economic impacts from NAFTA on Mexico concluded that NAFTA helped Mexico get closer to the levels of development in the United States and Canada. The study states that NAFTA helped Mexican manufacturers adapt to U.S. technological innovations more quickly; likely had positive impacts on the number and quality of jobs; reduced macroeconomic volatility, or wide variations in the GDP growth rate, in Mexico; increased the levels of synchronicity in business cycles in Mexico, the United States, and Canada; and reinforced the high sensitivity of Mexican economic sectors to economic developments in the United States.64

Other studies suggest that NAFTA has been disappointing in that it failed to significantly improve the Mexican economy or lower income disparities between Mexico and its northern neighbors.65 Some argue that the success of NAFTA in Mexico was probably limited by the fact that NAFTA was not supplemented by complementary policies that could have promoted a deeper regional integration effort. These policies could have included improvements in education, industrial policies, and/or investment in infrastructure.66

One of the more controversial aspects of NAFTA is related to the agricultural sector in Mexico and the perception that NAFTA has caused a higher amount of Mexican worker displacement in this sector than in other economic sectors. Many critics of NAFTA say that the agreement led to a large number of job losses in Mexican agriculture, especially in the corn sector. One study estimates these losses to have been over 1 million lost jobs in corn production between 1991 and 2000.67 However, while some of the changes in the agricultural sector are a direct result of NAFTA as Mexico began to import more lower-priced products from the United States, many of the changes can be attributed to Mexico's unilateral agricultural reform measures in the 1980s and early 1990s. Most domestic reform measures consisted of privatization efforts and resulted in increased competition. Measures included eliminating state enterprises related to agriculture and removing staple price supports and subsidies.68 These reforms coincided with NAFTA negotiations and continued beyond the implementation of NAFTA in 1994. The unilateral reforms in the agricultural sector make it difficult to separate those effects from the effects of NAFTA.

U.S.-Mexico Trade Market Shares

Mexico relies heavily on the United States as an export market; this reliance has diminished very slightly over the years. The percentage of Mexico's total exports going to the United States decreased from 83% in 1993 to 81% in 2015 (see Figure 5). In addition, its share of the U.S. market has lost ground since 2003 when China surpassed Mexico as the second-leading supplier of U.S. imports. The United States is losing market share of Mexico's import market. Between 1993 and 2015, the U.S. share of Mexico's imports decreased from 78% to 54%. China is Mexico's second-leading source of imports.

U.S. and Mexican Foreign Direct Investment

Foreign direct investment (FDI) has been an integral part of the economic relationship between the United States and Mexico for many years, especially after NAFTA. Two-way investment increased rapidly after the agreement went into effect. The United States is the largest source of FDI in Mexico. The stock of U.S. FDI in Mexico increased from $15.2 billion in 1993 to $104.4 billion in 2012 (587%), and then decreased to $92.8 billion in 2015 (see Table A-4). The flows of FDI have been affected by other factors over the years, with higher growth during the period of economic expansion during the late 1990s, and slower growth in recent years, possibly due to the economic downturn caused by the 2008 global financial crisis and/or the increased violence in Mexico. Mexican FDI in the United States, while substantially lower than U.S. investment in Mexico, has also increased rapidly, from $1.2 billion in 1993 to $16.6 billion in 2015 (1283% increase) (See Table A-4.)69

While Mexico's unilateral trade and investment liberalization measures in the 1980s and early 1990s contributed to the increase of U.S. FDI in Mexico, NAFTA provisions on foreign investment may have helped to lock in Mexico's reforms and increase investor confidence. NAFTA helped give U.S. and Canadian investors nondiscriminatory treatment of their investments as well as investor protection in Mexico. Nearly half of total FDI investment in Mexico is in the manufacturing industry.

Income Disparity

One of the main arguments in favor of NAFTA at the time it was being proposed by policymakers was that the agreement would improve economic conditions in Mexico and narrow the income disparity between Mexico and the United States and Canada. Studies that have addressed the issue of economic convergence70 have noted that economic convergence in North America has failed to materialize. One study states that NAFTA failed to fulfill the promise of closing the Mexico-U.S. development gap and that this was partially due to the lack of deeper forms of regional integration or cooperation between Mexico and the United States.71 The study contends that domestic policies in both countries, along with underlying geographic and demographic realities, contribute to the continuing disparities in income. The authors argue that neither Mexico nor the United States adopted complementary policies after NAFTA that could have promoted a more successful regional integration effort. These policies could include education, industrial policies, and more investment in border and transportation infrastructure. The authors also note that other developments, such as increased security along the U.S.-Mexico border after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, have made it much more difficult for the movement of goods and services across the border and for improving regional integration. They argue that the two countries could cooperate on policies that foster convergence and economic development in Mexico instead of increasing security and "building walls."72

A World Bank study states that NAFTA brought economic and social benefits to the Mexican economy, but that it is not enough to help narrow the disparities in economic conditions between Mexico and the United States.73 It contends that Mexico needs to invest more in education, innovation, and infrastructure, and in the quality of national institutions. The study also states that income convergence between a Latin American country and the United States is limited by the wide differences in the quality of domestic institutions, in the innovation dynamics of domestic firms, and in the skills of the labor force. While NAFTA had a positive effect on wages and employment in some Mexican states, the wage differential within the country increased as a result of trade liberalization.74 Another study also notes that the ability of Mexico to improve economic conditions depends on its capacity to improve its national institutions, adding that Mexican institutions did not improve significantly more than those of other Latin American countries since NAFTA went into effect.75

Effect on Canada

As noted earlier, the U.S.-Canada FTA came into effect on January 1, 1989. Thus, trade liberalization between the two countries was well underway—or already completed—by the time of the implementation of NAFTA. This section summarizes the effect of trade liberalization from both agreements on Canada.

From the Canadian perspective, the important consequence of the FTA may have been what did not happen, that is, that many of the fears of opening up trade with the United States did not come to pass. Canada did not become an economic appendage or "51st state," as many had feared. It did not lose control over its water or energy resources; its manufacturing sector was not gutted from the agreement. Rather, as one Canadian commentator remarked, "free trade helped Canada to grow up, to turn its face out to the world, to embrace its future as a trading nation, [and] to get over its chronic sense of inferiority."76 However, some hopes for the FTA, for example, that it would be a catalyst for greater productivity in Canadian industry, also have not come to pass.

U.S.-Canada Trade Market Shares

Canada is the second largest trading partner of the United States with $578.6 billion crossing the border in both directions in 2016, resulting in a trade deficit of $12.1billion. The United States is the number one purchaser of Canadian goods and supplier of imports to Canada. Canada's share of its exports going to the United States steadily increased during the 1980s, from 60.6% in 1980 to 70.7% in 1989, the first year of the FTA. Canada's percentage of total exports to the United States continued to increase, reaching 87.7% in 2002. The relative importance of the value of U.S. and Canadian trade with each other, however, has been falling in recent years. Since 2002, this percentage has fallen back to 76.4% in 2016. The U.S. share of Canada's total imports, which reached a peak of 70.0% in 1983, has steadily declined to a recent 52.1% in 2015 (Figure 6). Canada likes to point out that it is the leading export destination for 35 U.S. states.77

Traditionally, Canada was the largest purchaser of U.S. exports and supplier of U.S. imports; however, shares of both peaked before the FTA. Canada purchased 23.5% of U.S. exports in 1987 and equaled that figure in 2005, but it has since fallen to 18.3% in 2016. Canada traditionally was the largest supplier of U.S. imports, peaking at 20.6% in 1984, reaching a NAFTA high of 20.1% in 1996, but declining thereafter to 12.6% in 2016. China displaced Canada as the largest supplier of U.S. imports in 2007, and Mexico edged out Canada for second spot in 2015. Canada remains the largest trading partner of the United States when trade in services is taken into account.

The composition of trade has also changed. Canada initially entered a manufacturing recession after the FTA entered into force as branch plants of U.S. companies set up behind the Canadian tariff wall were abandoned. However, more internationally competitive manufacturing sectors thrived as long as the Canadian dollar (nicknamed the loonie for the soaring loon pictured on its reverse) was relatively cheap. From a low point of a Canadian dollar worth US$0.65 in 2002, the loonie reached parity in 2007, and has hovered around the parity point until 2013 before sliding to a recent US$ 0.75 at the end of 2016. The appreciation was attributed to the boom in Canada's natural resources—oil and gas displaced motor vehicles as Canada's largest export to the United States in 2005. The value of Canadian dollar is dependent on its commodity exports, and the depreciation resulted from the end of the boom that accompanied China's slowdown.

The "great recession" resulting from the 2008 financial crisis took a toll on Canadian manufacturing, which was exacerbated by the strong loonie in the 2010-2013 period. However, the recovery of the North American economy and the fall of the loonie after 2013 has not significantly improved the fortunes of some sectors of Canadian manufacturing. The Canadian auto sector is a case in point. Despite contributing C$12 billion to the bailout of General Motors and Chrysler, no new auto assembly plant in Canada has opened since 2009, model lines have been shifted to Mexico or the United States,78 and by 2014, Canada's share of North American vehicle output fell to 14%. According to the Royal Bank of Canada, "Planned capacity expansion in Mexico, including several new plants in the next few years, as well as stronger investment in the United States, could result in further erosion of Canadian producers' market share ... the same is true for Canadian parts manufacturers, who have lost a significant share of the US import market."79

For some advocates in Canada, free trade was meant to alleviate the long-term labor productivity gap between the United States and Canada. Open competition was seen as forcing Canadian industry to be more productive. Since NAFTA, this gap could be accounted for by the low value of the Canadian dollar. As adding capital equipment (often purchased from the United States) was relatively more expensive than hiring extra workers, the latter was often employed. The appreciation of the Canadian dollar made additional capitalization more attractive, but labor productivity recently remained only at 72% of U.S. levels.80 The relatively low productivity levels of Canadian industry, as well as its relatively low investments in research and development (R&D), and relatively lower expenditures on information technology, are seen as threatening to Canadian long-term competitiveness. This remains a concern to Canadian policymakers despite Canada leading the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development's (OECD) ranking in population with post-secondary education.81

Foreign Direct Investment

Two-way investment has also increased markedly since NAFTA, both in terms of stock and flow of investment. The United States is the largest single investor in Canada with a stock of FDI into Canada reaching $352.9 billion in 2015, up from a stock of $69.9 billion in 1993 (see Table A-4). U.S. investment represents 49.4% of the total stock of FDI in Canada from global investors. U.S. FDI flows into Canada averaged $3.28 billion in the five years prior to the FTA, and actually fell to an average of $1.7 billion in the first six years of the FTA, mainly attributed to divestments of U.S.-owned branch plants in Canada. However, U.S. flows into Canada have increased markedly to an average of $20.1 billion during the 10 years from 2005-2015.82 The stock of U.S. FDI is now equivalent to 22% of the value of Canadian GDP, in contrast to 1% at the beginning of the FTA.

While Canada is not the largest investor in the United States, the United States was the largest destination for Canadian FDI in 2015 with a stock of $269.0 billion, an increase from $26.6 billion in 1988.83 Approximately 42.2% of Canadian FDI was invested in the United States in 2014. Canadian FDI flows into the United States annually averaged $2.3 billion in five years prior to the FTA, and an annual average of $1.8 billion during the FTA years, but more recently increased to an annual average of $9.9 billion in the 10 years to 2015. These trends highlight the changing view of FDI among Canadians, from one that could be considered fearful or hostile to FDI as vehicles of foreign control over the Canadian economy, to one that is more welcoming of new jobs and techniques that result from FDI.

Procedures for NAFTA Renegotiation or Withdrawal

On May 18, 2017, the U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer sent a 90-day notification to Congress of the Administration's intent to begin talks with Canada and Mexico to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). As noted above, President Trump advocated for the renegotiation of NAFTA in the 2016 election campaign, or, perhaps, even withdrawing from the agreement itself. The following is a discussion of the procedural aspects of reopening NAFTA and the respective roles of the President and Congress.

Renegotiation

NAFTA provides that

- 1. The Parties may agree on any modification of or addition to this Agreement.

- 2. When so agreed, and approved in accordance with the applicable legal procedures of each party, a modification or addition shall constitute an integral part of the agreement.84

Under Article II of the Constitution, the President has the authority to negotiate with foreign countries. If President Trump decides to renegotiate NAFTA, implementation of the renegotiated agreement in domestic law would likely take one of two forms, depending on the subject of the negotiations: Presidential proclamation85 or, if renegotiation is expected to result in changes to U.S. law, the President likely would seek expedited treatment of the implementing legislation under the Bipartisan Comprehensive Trade Promotion and Accountability Act of 2015 (TPA).86

Some modifications to NAFTA may be proclaimed by the President pursuant to existing statutory authority. These include tariff modifications, basic and specific rules of origin, and certain customs provisions. In these cases, they can take effect 15 days after proclamation. However, certain proclamations are subject to consultation and layover requirements, including "such additional duties as the President determines to be necessary or appropriate to maintain the general level of reciprocal and mutually advantageous concessions with respect to Canada or Mexico provided for by the Agreement.87

The consultation and layover provisions are applicable to proclamations concerning

- tariff modification, including acceleration of tariff staging;

- modification of rules of origin specific to carpets and sweaters (Annex 300-B);

- modifications to specific rules of origin (Annex 401);

- automotive tracing requirement (Annexes 403.1, 403.2);

- regional value-content provisions for certain autos (Annex 403.3); and

- modification of rules of origin definitions.

NAFTA's implementing legislation did not provide for expedited procedures for legislative changes resulting from amendments to the agreement. The Senate report language on the implementing bill suggested that "[i]t is expected that normal legislative procedures would apply to any such legislation."88

Renegotiation of other provisions of NAFTA that would require changes to U.S. law likely would require implementing legislation. Such legislation could be considered under TPA.89 TPA is the time-limited authority that Congress uses to set trade negotiating objectives, to establish notification and consultation requirements, and to have implementing bills for certain reciprocal trade agreements considered under expedited procedures, provided certain requirements are met. TPA currently is in effect until July 1, 2021, provided that Congress does not pass an extension disapproval resolution in the sixty days prior to July 1, 2018. Under TPA, the President can initiate negotiations whenever

one or more existing duties or any other import restriction of any foreign country or the United States or any other barrier to, or other distortion of, international trade unduly burdens or restricts the foreign trade of the United States or adversely affects the United States economy ... 90

In order to use the expedited procedures of TPA, the President must notify and consult with Congress before initiating negotiations, give Congress a 90-day notice of intent to begin negotiations (sent on May 18, 2017), notify and consult with Congress during the course of the negotiations, and must adhere to several reporting requirements following the conclusion of any negotiations resulting in an agreement. The President must conduct the negotiations based on the negotiating objectives set forth by Congress in TPA legislation. If the President adheres to these and other requirements, then implementing legislation from the resulting agreement can be considered under expedited procedures, including guaranteed consideration, no amendments, and an up-or-down vote.

Withdrawal

NAFTA provides that a country can withdraw from the agreement "six months after it has provided written notice of withdrawal to the other parties." It also provides that the agreement shall remain in force for the other parties.91