Mexico’s Free Trade Agreements

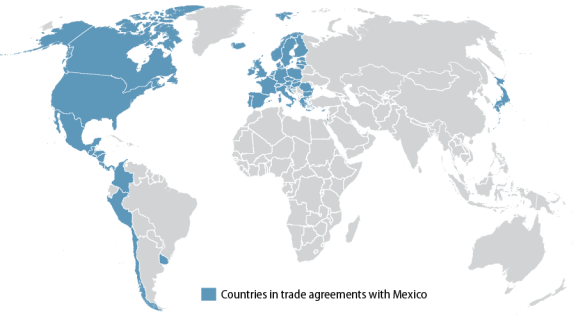

Mexico has had a growing commitment to trade integration and liberalization through the formation of free trade agreements (FTAs) since the 1990s, and its trade policy is among the most open in the world. Mexico’s pursuit of FTAs with other countries not only provides economic benefits, but could also potentially reduce its economic dependence on the United States. The United States is, by far, Mexico’s most significant trading partner. Approximately 80% of Mexico’s exports go to the United States, and about 47% of Mexico’s imports are supplied by the United States. In an effort to increase trade with other countries, Mexico has a total of 11 free trade agreements involving 46 countries. These include agreements with most countries in the Western Hemisphere, including the United States and Canada under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Peru, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. In addition, Mexico has negotiated FTAs outside of the Western Hemisphere and entered into agreements with Israel, Japan, and the European Union.

Economic motivations are generally the major driving force for the formation of free trade agreements among countries, but there are other reasons countries enter into FTAs, including political and security factors. One of Mexico’s primary motivations for its unilateral trade liberalization efforts of the late 1980s and early 1990s was to improve economic conditions in the country, which policymakers hoped would lead to greater investor confidence, attract more foreign investment, and create jobs. Mexico could also have other reasons for entering into FTAs, such as expanding market access and decreasing its reliance on the United States as an export market. The slow progress in multilateral trade negotiations may also contribute to the increasing interest throughout the world in bilateral and regional free trade agreements under the World Trade Organization (WTO). Some countries may see smaller trade arrangements as “building blocks” for multilateral agreements.

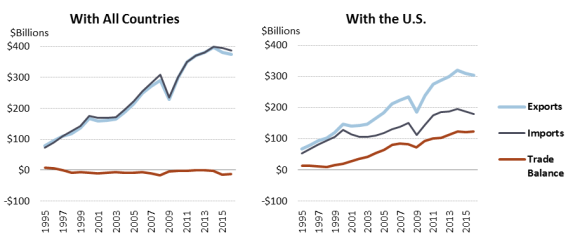

Since Mexico began liberalizing trade in the early 1990s, its trade with the world has risen rapidly, with exports increasing more rapidly than imports. Mexico’s exports to all countries increased 515% between 1994 and 2016, from $60.8 billion to $373.9 billion. Although the 2009 economic downturn resulted in a decline in exports, the value of Mexican exports recovered in the years that followed. Total imports also increased rapidly, from $79.3 billion in 1994 to $387.1 billion in 2016, an increase of 388%. The trade balance went from a deficit of $18.5 billion in 1994 to surpluses of $7.1 billion and $6.5 billion in 1995 and 1996. Since 1998, Mexico’s trade balance has remained a deficit, equaling $13.2 billion in 2016. Mexico’s top five exports in 2016 were passenger motor vehicles, motor vehicle parts, motor vehicles for the transport of goods, automatic data processing machines, and electrical apparatus for telephones. Mexico’s top five imports were motor vehicle parts, refined petroleum oil products, electronic integrated circuits, electric apparatus for telephones, and automatic data processing machines.

In the 115th Congress, issues of concern related to the trade and economic relationship with Mexico may involve a possible renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and its effects, Mexico’s external trade policy with other countries, Mexico’s intentions of moving forward with multilateral or bilateral free trade agreements with Asia-Pacific countries, economic conditions in Mexico and the labor market, and the status of Mexican migration to the United States. This report provides an overview of Mexico’s free trade agreements, its motivations for trade liberalization and entering into free trade agreements, and trade trends with the United States and other countries in the world.

Mexico's Free Trade Agreements

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Motivations for Trade Integration

- Mexican Trade Liberalization

- Mexico's Free Trade Agreements

- NAFTA

- Mexico-Chile

- Mexico-European Union

- Mexico-European Free Trade Association

- Mexico-Uruguay

- Mexico-Japan

- Mexico-Colombia

- Mexico-Israel

- Mexico-Peru

- Mexico-Central America

- Mexico-Panama

- Other Agreements

- Proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement

- Pacific Alliance

- Mexico-Bolivia Economic Complementation Agreement

- Partial Scope Agreements

- Mexico's Merchandise Trade

- Economic Policy Challenges for Mexico

- Implications for U.S. Interests

Figures

Summary

Mexico has had a growing commitment to trade integration and liberalization through the formation of free trade agreements (FTAs) since the 1990s, and its trade policy is among the most open in the world. Mexico's pursuit of FTAs with other countries not only provides economic benefits, but could also potentially reduce its economic dependence on the United States. The United States is, by far, Mexico's most significant trading partner. Approximately 80% of Mexico's exports go to the United States, and about 47% of Mexico's imports are supplied by the United States. In an effort to increase trade with other countries, Mexico has a total of 11 free trade agreements involving 46 countries. These include agreements with most countries in the Western Hemisphere, including the United States and Canada under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Peru, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. In addition, Mexico has negotiated FTAs outside of the Western Hemisphere and entered into agreements with Israel, Japan, and the European Union.

Economic motivations are generally the major driving force for the formation of free trade agreements among countries, but there are other reasons countries enter into FTAs, including political and security factors. One of Mexico's primary motivations for its unilateral trade liberalization efforts of the late 1980s and early 1990s was to improve economic conditions in the country, which policymakers hoped would lead to greater investor confidence, attract more foreign investment, and create jobs. Mexico could also have other reasons for entering into FTAs, such as expanding market access and decreasing its reliance on the United States as an export market. The slow progress in multilateral trade negotiations may also contribute to the increasing interest throughout the world in bilateral and regional free trade agreements under the World Trade Organization (WTO). Some countries may see smaller trade arrangements as "building blocks" for multilateral agreements.

Since Mexico began liberalizing trade in the early 1990s, its trade with the world has risen rapidly, with exports increasing more rapidly than imports. Mexico's exports to all countries increased 515% between 1994 and 2016, from $60.8 billion to $373.9 billion. Although the 2009 economic downturn resulted in a decline in exports, the value of Mexican exports recovered in the years that followed. Total imports also increased rapidly, from $79.3 billion in 1994 to $387.1 billion in 2016, an increase of 388%. The trade balance went from a deficit of $18.5 billion in 1994 to surpluses of $7.1 billion and $6.5 billion in 1995 and 1996. Since 1998, Mexico's trade balance has remained a deficit, equaling $13.2 billion in 2016. Mexico's top five exports in 2016 were passenger motor vehicles, motor vehicle parts, motor vehicles for the transport of goods, automatic data processing machines, and electrical apparatus for telephones. Mexico's top five imports were motor vehicle parts, refined petroleum oil products, electronic integrated circuits, electric apparatus for telephones, and automatic data processing machines.

In the 115th Congress, issues of concern related to the trade and economic relationship with Mexico may involve a possible renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and its effects, Mexico's external trade policy with other countries, Mexico's intentions of moving forward with multilateral or bilateral free trade agreements with Asia-Pacific countries, economic conditions in Mexico and the labor market, and the status of Mexican migration to the United States. This report provides an overview of Mexico's free trade agreements, its motivations for trade liberalization and entering into free trade agreements, and trade trends with the United States and other countries in the world.

Introduction

Regional trade agreements (RTAs) throughout the world have increased since the early 1990s. Many members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) are focusing on regional or bilateral free trade agreements as a key component of their foreign and commercial policy.1 This interest is evident among industrialized and developing countries, and throughout various world regions. Mexico is a member of the WTO, which permits members to enter into regional trade integration arrangements under certain conditions that are defined within specific WTO rules.2

Since the early 1990s, Mexico has had a growing commitment to trade liberalization and has a trade policy that is among the most open in the world. Mexico has actively pursued free trade agreements (FTAs) with other countries to help promote economic growth, but also to reduce its economic dependence on the United States. The United States is, by far, Mexico's most significant trading partner. Over 80% of Mexico's exports are destined for the United States. In an effort to increase trade with other countries, Mexico has entered into 11 free trade agreements with 46 countries.3 Mexico is a signatory to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a proposed free trade agreement (FTA) signed by 12 Asia-Pacific countries on February 4, 2016, after eight years of negotiation. It would require congressional ratification before it could become effective. On January 30, 2017, the United States gave notice to the other TPP signatories that it does not intend to ratify the agreement, effectively ending the U.S. ratification process and TPP's potential entry into force, unless the Administration changes its position. Mexico and other TPP countries have proposed moving forward on an FTA without the participation of the United States.4

In the 115th Congress, congressional interest related to the trade and economic relationship with Mexico may involve issues related to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and a possible renegotiation, the effects of NAFTA, Mexico's ongoing efforts to form trade agreements with other countries, the status of the proposed TPP and the possibility of its moving forward without the United States, economic conditions in Mexico, Mexico's labor market, and Mexican migration to the United States. This report provides an overview of Mexico's free trade agreements, its motivations for trade liberalization and entering into free trade agreements, trade trends with the United States and other countries, and some of the issues Mexico faces in addressing its economic challenges. This report will be updated as events warrant.

Motivations for Trade Integration

Economic motivations are generally the major driving force for the formation of free trade agreements among countries, but there are other reasons countries enter into FTAs, including political and security factors. Mexico's primary motivation for the unilateral trade liberalization efforts of the late 1980s and early 1990s was to improve economic conditions in the country, which policymakers hoped would lead to greater investor confidence and attract more foreign investment. This motivation was a major factor in negotiating NAFTA with the United States and Canada. The permanent lowering of trade and investment barriers and predictable trade rules provided by FTAs can improve investor confidence in a country, which helps attract foreign direct investment (FDI). Multinational firms invest in countries to gain access to markets, but they also do it to lower production costs.

Mexico has other motivations for continuing trade liberalization with other countries, such as expanding market access for its exports and decreasing its reliance on the United States as an export market. By entering into trade agreements with other countries, Mexico is seeking to achieve economies of scale in certain sectors of the economy and to expand its export market. FTAs provide partners with broader market access for their goods and services. Countries can benefit from trade agreements, because producers are able to lower their unit costs by producing larger volumes for regional markets in addition to their own domestic markets. When more units of a good or a service can be produced on a larger scale, companies are able to decrease cost of production.

Mexico's high dependence on the United States as an export market is a likely motivation for seeking FTAs and other regional trade arrangements with other countries. The slow progress in multilateral negotiations in the WTO may be another likely factor. Some countries see smaller trade arrangements as "building blocks" for multilateral agreements. Other motivations could be political. Mexico may be seeking to demonstrate good governance by locking in political and economic reforms through trading partnerships.

Mexican Trade Liberalization

From the 1930s through part of the 1980s, Mexico maintained a strong protectionist trade policy in an effort to be independent of any foreign power and as a means to promote domestic-led industrialization. Mexico established a policy of import substitution in the 1930s, consisting of a broad, general protection of the entire industrial sector through tight restrictions on foreign investment and by controlling the exchange rate to encourage domestic industrial growth. Mexico also nationalized the oil industry at this time. These protectionist economic policies remained in effect until the country began to experience a series of economic challenges several decades later.

In the mid-1980s, Mexico's economy was on the verge of collapse as a result of the 1982 debt crisis in which the Mexican government was unable to meet its foreign debt obligations. Much of the government's efforts in addressing these economic challenges were placed on privatizing state industries and moving toward trade liberalization. Mexico had few options but to open its economy through trade liberalization. In the late 1980s and early into the 1990s, Mexico implemented a series of measures to restructure the economy that included unilateral trade liberalization, replacing import substitution policies with others aimed at attracting foreign investment, lowering trade barriers, and making the country competitive in nonoil exports. In 1986, it acceded to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), assuring further trade liberalization measures that led to closer ties with the United States.

Mexico and the United States began NAFTA negotiations in the early 1990s. Canada later joined the negotiations, and the three countries signed the agreement on December 17, 1992. Before NAFTA came into force Mexico had already entered into its first agreement for free trade in goods, the Mexico-Chile FTA. NAFTA entered into force with much broader provisions than the Chile FTA, such as trade in services, government procurement, dispute settlement procedures, and intellectual property rights protection. In 1999, the original text of the Mexico-Chile FTA was complemented with broader provisions, similar to those under NAFTA. Mexico's initial motivation in pursuing FTAs with the United States and other countries was to stabilize the Mexican economy, which had experienced many difficulties throughout most of the 1980s with a significant deepening of poverty. The expectation in Mexico was that FTAs would increase export diversification; attract FDI; and help create jobs, increase wage rates, and reduce poverty.

|

|

Agreements (As of April 7, 2017) |

Date |

Date Entered into Force |

|

NAFTA (Mexico, Canada, United States) |

Dec. 17, 1992 |

Jan. 1, 1994 |

|

Chile |

April 17, 1998 |

Aug. 1, 1999 |

|

European Union (Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and United Kingdom) |

Dec. 8, 1997 |

Oct. 1, 2000 |

|

Nov. 27, 2000 |

July 1, 2001 |

|

|

Uruguay |

Nov. 15, 2003 |

July 15, 2004 |

|

Japan |

Sept. 17, 2004 |

April 1, 2005 |

|

Colombia |

June 13, 1994 |

Jan. 1, 2011 |

|

Israel |

April 10, 2000 |

Feb. 1, 2012 |

|

Peru |

April 6, 2011 |

Feb. 1, 2012 |

|

Central America (Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua) |

Nov. 22, 2011 |

Sept. 1, 2013 |

|

Panama |

April 3, 2014 |

July 1, 2015 |

Source: Trade agreement information from World Trade Organization, Regional Trade Agreement Database, at http://www.wto.org; and Organization of American States, Foreign Trade Information System, at http://www.sice.oas.org. Map created by CRS.

Notes: The WTO definition of a free-trade area is a group of two or more customs territories in which the duties and other restrictive regulations of commerce (except, where necessary, those permitted under Articles XI, XII, XIII, XIV, XV, and XX of the GATT) are eliminated on substantially all the trade between the constituent territories in products originating in such territories.

Mexico's Free Trade Agreements

Mexico's pursuit of free trade agreements with other countries is a way to bring benefits to the economy, but also to reduce its economic dependence on the United States. The United States is, by far, Mexico's most significant trading partner. Approximately 80% of Mexico's exports go to the United States and 47% of Mexico's imports come from the United States.5 In an effort to diversify and increase trade with other countries, Mexico has a total of 11 trade agreements involving 46 countries (see Figure 1). These include agreements with many countries in the Western Hemisphere including the United States and Canada, Chile, Colombia, Peru, and Uruguay.6 Mexico has also ratified an FTA with Central America (Costa Rica, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, and Nicaragua) that was signed on November 22, 2011. As of September 1, 2013, the FTA had entered into force among all 6 parties.

Mexico has also negotiated free trade agreements outside of the Western Hemisphere and, in July 2000, entered into agreements with Israel and the European Union. Mexico became the first Latin American country to have preferential access to these two markets. Mexico has completed a trade agreement with the European Free Trade Association of Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland. The Mexican government expanded its outreach to Asia in 2000 by entering into negotiations with Singapore, Korea, and Japan. In 2004, Japan and Mexico signed an Economic Partnership Agreement, the first comprehensive trade agreement that Japan signed with any country.7 However, the large number of trade agreements has not yet been successful in significantly decreasing Mexico's dependence on trade with the United States.

NAFTA

The North American Free Trade Agreement has been in effect since January 1, 1994. The agreement was signed in December 1992; NAFTA side agreements were signed in August 1993.8 At the time that NAFTA was implemented, the U.S.-Canada FTA was already in effect and U.S. tariffs on most Mexican goods were low. NAFTA opened up the Mexican market to the United States and Canada, creating the largest single market in the world. Some tariffs were eliminated immediately, while others were phased out in various schedules of 5 to 15 years. NAFTA provided the option of accelerating tariff reductions. It eliminated quotas and import licenses. It established rules on duty drawback programs, terminating all existing drawback programs by January 1, 2001. The agreement also contained provisions for market access in goods, agriculture, and most service sectors; foreign direct investment; intellectual property rights protection; sanitary and phytosanitary measures; government procurement; antidumping and countervailing duty matters; land transportation; dispute resolution; and special safeguard mechanisms. NAFTA was the first major free trade agreement that addressed environmental and labor concerns by including related provisions in separate side agreements that entered into force at the same time as NAFTA.

NAFTA provisions required that partner countries eliminate all nontariff barriers to agricultural trade, either through their conversion to tariff-rate quotas (TRQs) or ordinary tariffs. Mexico removed or replaced its import license requirements with TRQs and gradually phased these out over a 10-year period. Approximately one-half of U.S.-Mexico agricultural trade became duty-free when the agreement went into effect. Sensitive products receiving longer phaseout schedules of 14 to 15 years included sugar, corn, dry beans, frozen concentrated orange juice, winter vegetables, and peanuts. Trade in sugar, one of the most sensitive issues in the trade negotiations, received the longest TRQ phaseout period of 15 years. NAFTA included special safeguard provisions in which a partner country could apply the tariff rate in effect at the time the agreement entered into force if imports of a product reached a "trigger" level set out in the agreement.

Mexico-Chile

The Mexico-Chile FTA, completed in 1998, was enacted in Chile on July 7, 1999, and in Mexico on August 1, 1999. Mexico and Chile signed the agreement at the 1998 Summit of the Americas in Santiago, Chile, on April 17, 1998. The FTA was expected to deepen the growing trade relationship between the two countries and improve bilateral investment opportunities in both countries. The 1998 agreement replaced an earlier FTA that was reached between the two countries in 1991. It removed tariffs on almost all merchandise trade between the two countries.

The Mexico-Chile FTA includes provisions on national treatment and market access for goods and services; rules of origin; customs procedures; safeguards; standards; agriculture; sanitary and phytosanitary measures; investment; air transportation; telecommunications; temporary entry for business persons; IPR; dispute resolution; and other provisions. It does not include a chapter on energy, environment, or labor.9 A separate agreement, which was signed simultaneously, includes provisions to avoid double taxation for companies doing business in both countries. The FTA provisions are similar to those under NAFTA, but with no labor and environmental provisions. Other provisions that are not part of the FTA include financial services, patents, and government procurement.10

Mexico-European Union

The trade relationship between Mexico and the European Union is governed by a free trade agreement that entered into force on July 1, 2000, formally called the Economic Partnership Political Coordination and Cooperation Agreement and now known as the Global Agreement. Negotiations for the FTA began in October 1996 and the agreement was signed in March 2000. The motivations for the agreement were to expand market access for exports from the EU to Mexico and attract more FDI from the EU to Mexico.11 Since the entry into force of the Global Agreement, the two parties have entered into FTAs with other countries with updated provisions. Mexico and the EU agreed to conduct scoping exercises to determine whether the FTA needed modernizing to include provisions in more recent agreements that they had negotiated. In June 2015, the two parties announced that they would be launching negotiations for a new FTA.

Given the perceived possibility of a rising protectionist sentiment in the United States, some regional experts have suggested that Mexico and the European Union should seek to more aggressively negotiate new FTAs and deepen existing ones.12 On May 25, 2016, Mexico and the EU launched negotiations to renegotiate and modernize the Mexico-EU FTA. The initiative is meant to build on the existing FTA by drawing on FTAs with other countries. In February 2017, the EU Commissioner and Mexico's Minister of Economy announced that they would accelerate trade talks. They stated their intention to take their trade relations into the 21st century and deepen their openness to trade. Discussions have been held on government procurement, energy trade, IPR protection, rules of origin, and small- and medium-sized businesses.13

The current Mexico-EU Global Agreement includes provisions on national treatment and market access for goods and services; government procurement; IPR; investment; financial services; standards; telecommunications and information services; agriculture; dispute settlement; and other provisions. The agreement also includes chapters on cooperation in a number of areas, including mining, energy, transportation, tourism, statistics, science and technology, and the environment.14 On industrial goods, the EU agreed to eliminate tariffs on 82% of imports by value coming from Mexico on the date of entry into the agreement and to phase out remaining tariffs by January 1, 2003. Mexico agreed to eliminate tariffs on 47% of imports by value from the EU upon implementation of the agreement and to phase out the remaining tariffs by January 1, 2007. In agricultural products and fisheries, signatories agreed to phase out tariffs on 62% of trade within 10 years.15 Tariff negotiations were deferred on certain sensitive products, including meat, dairy products, cereals, and bananas. Most nontariff barriers, such as quotas and import/export licenses, were removed upon implementation of the agreement. Mexico agreed to phase out import restrictions of new automobiles from the EU by 2007. In government procurement, Mexico agreed to follow provisions similar to those under NAFTA to allow the EU to enter the Mexican market while the EU agreed to follow WTO rules.16 In services trade, the agreement goes beyond the WTO General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). It immediately provided European service operators "NAFTA-equivalent" access to Mexico in a number of areas, including financial services, energy, telecommunications, and tourism.17

Mexico-European Free Trade Association

Mexico and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), composed of Iceland, Lichtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland, signed a free trade agreement on November 27, 2000. The agreement entered into force on July 1, 2001. This was the first FTA that the EFTA had concluded with an overseas partner country. Since the agreement entered into force, Mexico and the EFTA have met at least four times to explore possibilities of further trade integration, including agricultural and services trade. In September 2008, the two parties agreed to adopt an amendment on transportation to the agreement to help facilitate trade. They also discussed possibilities of further amendments, such as banning export duties and extending the coverage of trade in processed agricultural products.18

The agreement includes provisions on national treatment and market access for goods; agriculture; rules of origin; safeguards; and other provisions.19 During the first six years, the FTA reduced the average Mexican tariff on EFTA industrial goods from 8% to zero. Mexican industrial exports to the EFTA have been free of duty since the entry into force of the FTA.20

Mexico-Uruguay

On November 15, 2003, the presidents of Mexico and Uruguay signed the Mexico-Uruguay free trade agreement. The agreement entered into force on July 15, 2004. In addition to market-opening measures, the Mexico-Uruguay FTA includes chapters on services trade, investment, intellectual property rights, dispute resolution procedures, government procurement, rules of origin, customs procedures, technical measures, sanitary and phytosanitary measures, and safeguard provisions. Upon entry into force, the agreement eliminated virtually all tariffs in most manufactured goods, with some exceptions. Tariffs on footwear are being phased out over a 10-year period. Wool products are subject to tariff-rate quotas, and automotive goods are covered under a separate economic complementation agreement. In agriculture, Uruguay lowered 240 tariff lines on products imported from Mexico. Sensitive products, such as corn, beans, poultry, and other meat products, were excluded from the agreement. Tariffs on bovine meat products were lowered from 10% to 7% over a three-year period.21

Mexico-Japan

Mexico and Japan signed a free trade agreement, the Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA), in September 2004. The EPA was Japan's second free trade agreement, and its most comprehensive bilateral agreement at that time. It was Japan's first agreement to liberalize trade in agricultural products, a factor that resulted in initial opposition in Japan. In addition to the removal of tariff barriers, it includes regulations in other areas, including labor mobility and investment.22 Since the signing of the EPA in 2004, Japan and Mexico further liberalized bilateral trade by entering into negotiations and agreeing to strengthen the EPA. After two-and-a-half years of talks, the countries announced an agreement to revise the EPA and signed the new agreement on September 23, 2011.23 Under the revised agreement, Japan expanded low-tariff import quotas for certain agricultural imports from Mexico, including beef, pork, chicken, and oranges. Mexico agreed to accelerate the removal of import tariffs, from 2014 to 2012, on auto parts and paper for ink-jet printers. Mexico also eliminated tariffs on mandarin oranges and established tariff rate quotas for apples and green tea.24

One of the goals of the Mexico-Japan EPA was to restore the competitiveness of Japanese companies in the Mexican market. Mexico already had free trade with the United States and Canada under NAFTA and with the European Union. These two agreements had placed Japanese companies at a disadvantage due to differences in tariff rates and exclusion of Japanese companies from public-works projects in Mexico. Mexico entered the agreement to increase Japanese investment in Mexico, and, thus, create jobs, expand Mexican exports to Japan, expand technology transfer from Japan, and strengthen Mexican industrial competitiveness.25

The agreement includes provisions on national treatment and market access for goods; sanitary and phytosanitary measures; standards; rules of origin; customs procedures; safeguards; IPR; dispute settlement; financial services; and government procurement. The revised agreement also includes chapters in which the two countries agreed to increase cooperation in a number of areas, including vocational education and training, agriculture, tourism, and the environment.26 Under the revised FTA, Japan agreed to expand low-tariff import quotas for agricultural items including beef, pork, chicken, and oranges. Mexico agreed to abolish import tariffs on auto parts and paper for ink-jet printers earlier than the initially scheduled 2014 date.27 Prior to the original EPA, only 16% of Japanese exports to Mexico entered duty free into the Mexican market, while 70% of Mexican exports to Japan entered duty free.

Mexico-Colombia

Colombia, Mexico, and Venezuela signed a free trade agreement on June 13, 1994. The trilateral agreement entered into force on January 1, 1995. In May 2006, Venezuela notified its partners of its intent to withdraw from the agreement, and by November 2006, Venezuela had officially withdrawn. The agreement between Mexico and Colombia remains in effect. The two countries have since expanded their agreement and further liberalized trade. Negotiations for the expanded bilateral trade agreement began in August 2009 and were concluded in 2011. The revised expansion of the Mexico-Colombia FTA went into effect on January 1, 2011. It includes five provisions related to market access, rules of origin, a regional trade integration committee, official duties of the treaty's administrative commission, and an official name change to the FTA.28

The agreement includes measures related to market access, antidumping and countervailing duties, rules of origin, customs procedures, dispute resolution, government procurement, intellectual property rights protection, investment, safeguard measures, sanitary and phytosanitary provisions, tariff-rate quotas, technical regulations, and technical barriers to trade.29 The new treaty includes expanded market access in the Colombian market for Mexican exports of semitrailers, nonalcoholic drinks, chickpeas, orange juice, hard wheat, turkey preparations, and tomatoes. It also opens up the Mexican market for Colombian crackers, citric acid, sodium and calcium citrate, palm oil, pork rinds, cigarettes, and other products. The agreement does not include trade liberalization for the following products: coffee, plantains, sugar, tobacco, and cacao. These products are major export products for Colombia but sensitive items for Mexico, according to Mexico's Economy Secretary, Bruno Ferrari.30 Mexico agreed to allow Colombia to export limited quantities of dairy and beef products.31

Mexico-Israel

After two years of negotiations, Mexico and Israel signed a free trade agreement on April 10, 2000, and implemented it on July 1, 2000. The agreement immediately eliminated tariffs on most products traded between Mexico and Israel at the time of the agreement with full tariff elimination scheduled by 2005. Policymakers expected the agreement to provide Mexico with more export access to the Israeli market, increase FDI from Israel to Mexico, and result in increased technology transfer from Israel to Mexico.

The agreement includes provisions on national treatment and market access for goods, rules of origin, customs procedures, emergency actions, competition policy, government procurement, dispute resolution, dispute resolution, and WTO rights and obligations.32 The agreement covers 98.6% of agricultural goods and 100% of industrial goods. Mexico received immediate duty-free access on 50% of its exports and tariff reductions on 12% of its exports to Israel. Tariff-rate quotas were applied on 25% of Mexican exports to Israel. Most remaining tariff barriers on Mexican exports had a five-year phaseout schedule. Israel received immediate duty-free access on about 72% of its exports to Mexico. Another 22.8% of tariffs on Israeli exports to Mexico were withdrawn in 2003 and another 4.4% were withdrawn in 2005.33

Mexico-Peru

In December 2005, Mexico and Peru began negotiations to broaden and deepen the Economic Cooperation Agreement (ECA) that had been in place since 1987. The two countries negotiated to deepen the trade relationship by liberalizing trade in all goods and form a free trade agreement. After six years, Mexico and Peru concluded negotiations and signed the free trade agreement, formally named the Mexico-Peru Trade Integration Agreement, on April 6, 2011. The Mexico-Peru FTA entered into force on February 1, 2012.

The FTA covers 12,017 products and replaces the 1987 ECA, which covered 765 products.34 Tariffs are to be phased out over a 10-year period. The agreement includes provisions on trade in goods and services, investment, sanitary and phytosanitary measures, dispute resolution procedures, rules of origin, safeguards, antidumping and countervailing duties, financial services, transparency procedures, and temporary entry of business persons.35

Mexico-Central America

The FTA between Mexico and Central America (Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua) was signed on November 22, 2011. The first round of negotiations took place in May 2010 in Mexico City. After a total of eight rounds of talks, the countries concluded negotiations on October 20, 2011.36 The FTA was ratified by the governments of all parties by September 1, 2013.37

Initiated in June 2008, the Mexico-Central America FTA converged existing free trade agreements between Mexico and Central American countries to create a single regional agreement with Mexico. Upon its entry into force, the FTA replaced the following three former FTAs:

- 1. Mexico-Costa Rica FTA. The former Mexico-Costa Rica FTA was signed on April 5, 1994, in Mexico City and entered into force on January 1, 1995. It was the first in a series of FTAs negotiated by Mexico loosely based on the NAFTA model of trade agreements. This agreement had been preceded by a partial scope agreement signed by the two countries on July 22, 1982, in which Mexico accorded preferential access to some Costa Rican products.

- 2. Mexico-Nicaragua FTA. The former FTA with Nicaragua was Mexico's second treaty with a Central American country, also loosely based on the NAFTA model. It was signed on December 18, 1997, and entered into force on July 1, 1998. Upon entry into force of the bilateral Mexico-Nicaragua agreement, 76% of tariffs on Nicaraguan exports to Mexico and 45% of tariffs on Mexican exports to Nicaragua were eliminated. The remaining tariffs were phased out in four stages over a 15-year period.

- 3. Mexico-Northern Triangle (El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras). Mexico and El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras signed the former FTA on June 29, 2000. Entering into force in 2001, the agreement was commonly referred to as the Mexico-Northern Triangle FTA. Negotiations for the FTA with all three countries began in 1992, stalled for four years, and resumed at the second Tuxtla Summit in 1996. Negotiations ended on May 10, 2000. This agreement was the final of Mexico's NAFTA-type agreements with all Central American countries. Prior to the conclusion of the Mexico-Northern Triangle FTA, Mexico had held separate partial scope agreements with each of the three countries, granting some products preferential access to the Mexican market.

Mexico-Panama

The Mexico-Panama FTA entered into force on July 1, 2015. Negotiations for the agreement began on May 25, 2013. After five rounds of negotiations, the talks were concluded on March 24, 2014, and the agreement was signed on April 3, 2014, in Panama City, Panama.38 The agreement completes one of the prerequisites for Panama to join the Pacific Alliance in which all members must have FTAs with each other. In addition to market access measures, the agreement includes provisions on intellectual property rights, rules of origin, dispute resolution, sanitary and phytosanitary measures, e-commerce, financial services, travel rules, and investment. The FTA has 21 chapters and covers about 4,000 tariffs.39

Other Agreements

Mexico has pursued further trade liberalization such as the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement, the Pacific Alliance, and other efforts.

Proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement

Mexico is a party to the TPP, a proposed FTA signed by the United States, Mexico, Canada, and nine other Asia-Pacific countries on February 4, 2016, after eight years of negotiation. In January 2017, the United States gave notice to the other TPP signatories that it does not intend to ratify the agreement. The other countries may move forward on an agreement and released a statement reiterating their commitment to liberalizing international markets, advancing a rules-based trading system, and their intent to continue the discussions.40 Mexico has repeatedly expressed its interest in pursuing a regional trade agreement with other TPP members, or even binational FTAs with the countries with which it does not have an FTA.41 TPP, or a similar agreement, if enacted by Mexico and other countries, would reduce and eliminate tariff and nontariff barriers on goods, services, and agriculture. It could establish trade rules and disciplines that expand on commitments at the World Trade Organization (WTO) and address new issues. If similar to the TPP, it would achieve a high standard and comprehensive regional FTA. Such an FTA could enhance the links Mexico already has through its FTAs with other TPP signatories—Canada, Chile, Japan, and Peru—and expand its trade relationship with other TPP countries, including Australia, Brunei, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, and Vietnam.

Pacific Alliance

Mexico is a party to the Pacific Alliance, a regional integration initiative formed by Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru on April 28, 2011. Its main purpose is for members to form a regional trading bloc and forge stronger economic ties with the Asia-Pacific region. Costa Rica and Panama are candidates to become full members once they meet certain requirements. The United States joined the Alliance as an observer on July 18, 2013. The United States has free trade agreements with all four countries and has significant trade and foreign policy ties with the region. The Alliance was officially created when the heads of state of Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru signed a Presidential Declaration for the Pacific Alliance, now known as the Lima Declaration. The objectives are to build an area of deep economic integration; to move gradually toward the free circulation of goods, services, capital, and persons; to promote economic development, regional competiveness, and greater social welfare; and to become a platform for trade integration with the rest of the world, with a special emphasis on the Asia-Pacific region. One of the requirements for membership is that a country must have free trade agreements with all other member countries.

The Alliance's approach to trade integration is often looked upon as a pragmatic way of deepening economic ties. It is more outwardly focused than other regional initiatives such as the Common Market of the South (Mercosur). Another unique characteristic is that the four member countries share similar economic and political ideals and are moving forward quickly to accomplish their goals. Member countries have signed various agreements to share use of their facilities or embassies and consulates to further advance the objectives of the integration process. In February 2014, Presidents of Pacific Alliance countries signed the Additional Protocol of the Framework Agreement, which immediately eliminated 92% of tariffs among members. Some analysts see the Pacific Alliance as a potential rival to Mercosur and have noted that it could put pressure on other Latin American countries to pursue more market-opening policies. The Alliance has a larger scope than free trade agreements, since the Alliance involves the free movement of people and includes measures to integrate the stock markets of member countries.

Mexico-Bolivia Economic Complementation Agreement

Mexico and Bolivia signed a comprehensive FTA, loosely based on the NAFTA model, in September 1994. The FTA entered into force on January 1, 1995, establishing a free trade area that would be phased in over a period of 15 years. On June 7, 2010, at the request of the Bolivian government, the two countries entered into an agreement called an Economic Complementation Agreement (ECA), effectively terminating the previous FTA that had been in effect for 16 years.

When the Bolivian government adopted a new constitution in February 2009, it determined that certain chapters of the FTA were incompatible under the new constitution and that the treaty with Mexico would have to be renegotiated. The government determined that the FTA chapters related to investment, services trade, intellectual property rights, and government procurement were unconstitutional. The 2010 ECA that replaced the 1995 FTA maintained the free trade of goods without changing the agreed preferential tariff treatment in the previous FTA.42

Partial Scope Agreements

Mexico has a number of partial scope agreements, which are integration agreements with more limited free trade coverage than a free trade agreement (see Table 1). Mexico is a party to the Agreement on the Global System of Trade Preferences Among Developing Countries (GSTP). The GSTP was established in 1988 as a framework for the exchange of trade preferences among developing countries to promote trade among developing countries. The agreement provides tariff preferences on merchandise trade among member countries. It is a treaty to which only Group of 77 member countries may enter.43 The text of the agreement was adopted after a round of negotiations that was concluded in Belgrade in 1988. The agreement, which entered into force on April 19, 1989, was envisaged as being a dynamic instrument which would be expanded in successive stages in additional rounds of negotiations and reviewed periodically.44 A second round of negotiations was proposed in the early 1990s to expand trade preferences, but negotiations faltered as members failed to ratify the agreement. In June 2004, GSTP participants launched a third round of negotiations. Forty-four countries have acceded to the agreement.45

Mexico is a signatory to the Latin American Integration Association (ALADI), which was established by the Treaty of Montevideo in August 1980 and entered into force on March 18, 1981. ALADI replaced the Latin American Free Trade Association established in 1960 with the goal of developing a common market in Latin America. ALADI members include Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, Mexico, Paraguay, Perú, Uruguay, and Venezuela. Signatory countries have sought economic cooperation among each other but have made little progress toward forming a common market. They maintain a flexible goal of encouraging free trade without a timetable for instituting a common market. Members approved a regional tariff preference arrangement in 1984 and expanded it in 1987 and 1990.46

In addition, Mexico is a member of the Protocol Relating to Trade Negotiations among Developing Countries (PTN). The PTN is a preferential arrangement involving Bangladesh, Brazil, Chile, Egypt, Israel, Mexico, Pakistan, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Republic of Korea, Serbia, Tunisia, Turkey, and Uruguay. It was signed in December 1971 and became effective on February 11, 1973.

|

Agreement |

Coverage |

Date of Signature |

Entry into Force |

WTO Legal Cover |

|

Global System of Trade Preferences Among Developing Countries (GSTP)a |

Goods |

April 13, 1988 |

April 19, 1989 |

Enabling Clause |

|

Latin American Integration Association (ALADI)b |

Goods |

August 12, 1980 |

March 18, 1981 |

Enabling Clause |

|

Protocol on Trade Negotiations (PTN)c |

Goods |

December 8, 1971 |

February 11, 1973 |

Enabling Clause |

Source: World Trade Organization, Regional Trade Agreement Database, available at http://www.wto.org.

a. Includes Algeria, Argentina, Bangladesh, Benin, Venezuela, Bolivia, Brazil, Cameroon, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, Egypt, Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Ghana, Guinea, Guyana, India, Indonesia, Islamic Republic of Iran, Iraq, Republic of Korea, Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Tanzania, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Vietnam, and Zimbabwe.

b. Includes Argentina, Venezuela, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, Mexico, Paraguay, Perú, and Uruguay.

c. Includes Bangladesh, Brazil, Chile, Egypt, Israel, Republic of Korea, Mexico, Pakistan, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Serbia, Tunisia, Turkey, and Uruguay.

Mexico's Merchandise Trade

In 2016, Mexico's leading export items were passenger motor vehicles, motor vehicle parts, motor vehicles for transport of goods, automatic data process machines, and electrical apparatus for telephones. Leading import items were motor vehicle parts, refined petroleum oil products, electronic integrated circuits, electric apparatus for telephones, and automatic data process machines (see Table 2). Since trade liberalization, Mexico's trade with the world has risen rapidly, with exports increasing faster than imports. Mexico's exports to all countries increased 515% between 1994 and 2016, from $60.8 billion to $373.9 billion (see Figure 2). Although the 2009 economic downturn resulted in a decline in the value of exports, exports regained their strength in the following years. Mexico's imports from all countries increased from $79.3 billion in 1994 to $387.1 billion in 2016, an increase of 388%. Mexico's trade balance went from a deficit of $18.5 billion in 1994 to surpluses of $7.1 billion in 1995 and $6.5 billion in 1996. Since 1998, Mexico's trade balance with all countries has remained in deficit, equaling $13.2 billion in 2016; its trade balance with the United States was a surplus of $122.0 billion in 2016 as shown in Figure 2.

|

Mexico's Leading Exports |

Mexico's Leading Imports |

||||||

|

Product |

Value |

Product |

Value |

||||

|

Passenger motor vehicles |

|

Motor vehicle parts |

|

||||

|

Motor vehicle parts |

|

Petroleum oil products (not crude) |

|

||||

|

Motor vehicles for transport of goods |

|

Electronic integrated circuits |

|

||||

|

Automatic data process machines |

|

Electric apparatus for telephones |

|

||||

|

Electrical apparatus for telephones |

|

Automatic data process machines |

|

||||

|

Other |

|

Other |

|

||||

|

Total |

|

Total |

|

||||

Source: Compiled by CRS using data from Mexico's Subsecretaría de Negociaciones Comerciales Internacionales.

|

|

Source: Compiled by CRS using data from Global Trade Atlas. |

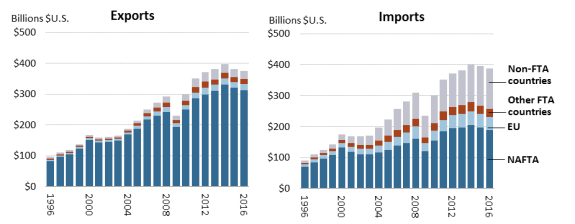

Mexico's reliance on the United States as a trade partner has remained at relatively the same level over the years, despite its efforts to diversify trade (see Figure 3). The percentage of total exports going to the United States decreased slightly between 1996 and 2016, from 83% to 81%. In 2016, 93% of Mexico's exports went to countries with which it has FTAs. Exports to the NAFTA countries accounted for 84% of total exports, while exports to the European Union accounted for only 5%.

In imports, the U.S. share of Mexico's total imports has declined steadily over the years. Between 1996 and 2016, the share of U.S. products entering the Mexican market decreased from 75% to 47%, while the share of products from NAFTA as a region declined from 77% to 49% (see Figure 3). During the same time period, the share of Mexico's imports from non-FTA countries increased from 8% to 34%. Although Mexico does not have an FTA with China, Mexico's imports from China have increased considerably in recent years. Imports from China went up from $760 million, or 1% of total imports, in 1996 to $69.5 billion, or 18% of total imports, in 2016. The value of Mexico's imports from China is higher than that from the European Union or Japan.

|

|

Source: Compiled by CRS using data from Mexico's Subsecretaria de Comercio Exterior. |

Economic Policy Challenges for Mexico

The United States continues to be the dominant export market for Mexican goods, despite the Mexican government's efforts to liberalize trade with other countries. The reliance on the United States as an export market makes the Mexican economy more susceptible to economic and political conditions in the United States. For example, the global financial crisis of 2009, which contributed to a downturn in the U.S. economy, resulted in the deepest recession in the Mexican economy since the 1930s. More recently, the Mexican peso weakened to record lows in the aftermath of the U.S. election of President Donald Trump in November 2016 in which he made campaign promises to withdraw from NAFTA and build a border wall with Mexico.47

Some industry experts maintain that Mexico's manufacturing sector has numerous strategic and financial benefits for foreign companies seeking a competitive advantage and that it can be more advantageous for U.S. manufacturers to invest in Mexico rather than China.48 For example, labor costs in China have risen over the past 10 years and are higher in some sectors than those in Mexico. Another advantage that Mexico has in comparison to China is the proximity it has to the United States, which provides more cultural similarities, increased efficiencies in manufacturing operations, lower transportation costs, and greater supply chain efficiencies.49 Nonetheless, Mexico continues to face strong competition from China and other Asian economies in the manufacturing sector. In 2003, China replaced Mexico as the second-highest source of U.S. imports.

Implications for U.S. Interests

Mexico's numerous free trade agreements and its trade liberalization policy are of interest to U.S. policymakers because of the implications for U.S.-Mexico trade, economic stability in Mexico, and the overall relationship between the two countries. Economic conditions in Mexico are important to the United States because of the proximity of Mexico to the United States, the close trade and investment interactions, and other social and political implications. Another issue of interest to U.S. policymakers is the effect of Mexico's FTAs on U.S. exports to Mexico. The liberalization of Mexico's trade and investment barriers to other countries has resulted in increasing competition for U.S. goods and services in the Mexican market. Consequently, the U.S. share of goods imported by Mexico has been falling steadily over the years.

The initial trade policies of the Trump Administration include U.S. withdrawal from TPP and the possibility of a renegotiation of NAFTA. In regard to the TPP, some TPP signatories have announced their intention to move forward on a similar agreement without the United States, which may affect U.S. competitiveness in certain markets. Canada and Mexico have numerous FTAs with other countries and may continue to seek to diversify trade through FTAs. Mexico's Economy Minister stated that Mexico is willing to negotiate a new agreement with the Asia-Pacific region that may be similar to TPP and include China in the discussions.50

In regard to NAFTA, none of the parties have formally announced what provisions they would seek in a renegotiation of the agreement. Any changes in NAFTA could bring disruptions to the extensive supply chains throughout North America, which could affect economic conditions and jobs in all three countries, especially in Mexico. A number of studies suggest that while Mexico's trade liberalization policy, mainly NAFTA, may have brought economic and social benefits to the Mexican economy as a whole, the benefits have not been evenly distributed throughout the country and poverty persists in some regions of the country.

Given that NAFTA is more than 20 years old, renegotiation may provide opportunities to address issues not currently covered in the agreement. Topics of renegotiations could include services trade, rules of origin, government procurement, intellectual property rights protection, labor issues, and the environment. Mexico has stated that it would consider modernizing NAFTA, but it is not clear how this would take place. Mexican government officials have hinted that Mexico may seek to broaden NAFTA negotiations to include bilateral or trilateral cooperation on various issues, especially security and immigration.51

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

[author name scrubbed], CRS Visual Information Specialist, and [author name scrubbed], CRS Information Resource Specialist, contributed to this report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

See CRS In Focus IF10002, The World Trade Organization, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 2. |

For more information on the specific sets of rules governing regional trade agreements among WTO members, see Regional Trade Agreements: Rules on the WTO website, available at http://www.wto.org. |

| 3. |

World Trade Organization (WTO), Regional Trade Agreement Database, available at http://www.wto.org; and Organization of American States, Foreign Trade Information System, available at http://www.sice.oas.org. |

| 4. |

See CRS In Focus IF10000, TPP: Overview and Current Status, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 5. |

Mexican government data from the Subsecretaría de Comercio Exterior. |

| 6. |

Mexico and Bolivia had a previous FTA that entered into force on January 1, 1995. The FTA was terminated 16 years later on June 7, 2010, at the request of the Bolivian government. The current agreement for Mexico and Bolivia is an "Economic Complementation Agreement", which ended most FTA provisions but maintained the same tariff levels on goods as the previous FTA. |

| 7. |

The Asahi Shimbun, "Japan: Free Trade with Mexico," March 12, 2004. |

| 8. |

See CRS Report R42965, The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed], and CRS In Focus IF10047, North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 9. |

Decreto Promulgatorio del Tratado de Libre Comercio entre el Gobierno de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos y el Gobierno de la República de Nicaragua. See WTO Regional Trade Agreement Database, http://www.wto.org. |

| 10. |

Bureau of National Affairs (BNA), International Trade Reporter, "Mexico and Chile Sign Off on Expanded Trade Agreement," April 22, 1998. |

| 11. |

Reuters, "Cumbre-México y Unión Europea Acuerdan Acelerar Libre Comercio," May 17, 2008. |

| 12. |

"Former Latin American Officials: Shift Trade Focus to EU and Asia over U.S.," World Trade Online, April 5, 2017. |

| 13. |

European Commission, EU and Mexico Agree to Accelerate Trade Talks, Brussels, Belgium, February 1, 2017, http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/press/index.cfm?id=1617. |

| 14. |

Global Agreement, Economic Partnership, Political Coordination and Cooperation Agreement between the European Community and its member States and the United Mexican States. See WTO Regional Trade Agreement Database, see http://www.wto.org. |

| 15. |

The Chinese University of Hong Kong, The Mexico-EU Free Trade Agreement, 2000, http://intl.econ.cuhk.edu.hk. |

| 16. |

Transnational Institute, Mexican Action Network on Free Trade (RMALC), The EU-Mexico Free Trade Agreement Seven Years On, June 2007. |

| 17. |

U.S.-Mexico Chamber of Commerce, The Free Trade Agreement Between Mexico and the European Union, August 2000. |

| 18. |

The European Free Trade Association (EFTA) Secretariat, EFTA and Mexico to Amend Free Trade Agreement, September 2008. |

| 19. |

Free Trade Agreement between the EFTA States the United Mexican States. . See WTO Regional Trade Agreement Database, see http://www.wto.org. |

| 20. |

Mexico-EU Trade Links, "Mexico-EFTA Free Trade Agreement: After Six Years," July 2007. |

| 21. |

Executive Office of the President of Mexico press release, "Las Buenas Noticias También Son Noticia: Entra en Vigor el TLC México-Uruguay," August 13, 2004. |

| 22. |

The Asahi Shumbun, "Japan, Mexico Ink Landmark Accord," September 20, 2004. |

| 23. |

The Journal of Commerce Online, "Japan, Mexico Sign Revised Trade Agreement," February 23, 2011. |

| 24. |

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, "Signing of the Protocol Amending the Agreement between Japan and the United Mexican States for the Strengthening of the Economic Partnership," September 23, 2011. |

| 25. |

Press Center Japan, "Japan and Mexico Agree on Conclusion of Free-Trade Agreement," March 31, 2004. |

| 26. |

Agreement Between Japan the United Mexican States for the Strengthening of the Economic Partnership. See WTO Regional Trade Agreement Database, see http://www.wto.org. |

| 27. |

The Journal of Commerce, "Japan, Mexico Sign Revised Trade Agreement," February 23, 2011. |

| 28. |

Colombian Government, Ministry of Commerce, "Entra en Vigencia Protocolo que Modifica el TLC con México," August 1, 2011. |

| 29. |

For more information, see World Trade Organization, Regional Trade Agreements database, at http://rtais.wto.org. |

| 30. |

Latino Fox News, "Mexico on verge of ratifying expanded FTA with Colombia," April 1, 2011. |

| 31. |

Ibid. |

| 32. |

Free Trade Agreement Between the State of Israel and the United Mexican States. See WTO Regional Trade Agreement Database, see http://www.wto.org. |

| 33. |

U.S.-Mexico Chamber of Commerce, "History of Mexico-Israel Trade Relations," September 2000. |

| 34. |

Vigo, Manuel, "Peru Free Trade Agreement Ratified by Mexico's Senate," Peru This Week, December 16, 2011. |

| 35. |

Mexico's Economic Ministry, "Concluye Negociación para un Acuerdo de Integración Comercial entre México y Perú," Boletín de Prensa, No. 68, June 4, 2011. |

| 36. |

OAS, Foreign Trade Information System, Background and Negotiations on the Central America Countries – Mexico, available at https://www.sice.oas.org. |

| 37. |

The Mexico-Central America FTA was ratified by Mexico on January 9, 2012; by Nicaragua and El Salvador on September 1, 2012; by Honduras on January 1, 2013; by Costa Rica on July 1, 2013; and by Guatemala on September 1, 2013. |

| 38. |

Organization of American States, Foreign Trade Information System, at http://www.sice.oas.org. |

| 39. |

Agencia EFE, "Panama-Mexico FTA will Boost Regional Integration, Officials Say," Panama City, July 1, 2015. |

| 40. |

See CRS Insight IN10669, Moving On: TPP Signatories Meet in Chile, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 41. |

Fran O'Sullivan, "Mexico Pushes for Trade Deal with New Zealand," February 4, 2017. |

| 42. |

Organization of American States, Foreign Trade Information System, Information on Mexico, retrieved on April 5, 2017, http://www.sice.oas.org/ctyindex/MEX/MEXagreements_e.asp. |

| 43. |

The Group of 77 (G-77) was established on June 15, 1964 by 77 developing countries, signatories of the "Joint Declaration of the Seventy-Seven Countries," issued at the end of the first session of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in Geneva. |

| 44. |

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Press Release, "Global System of Trade Preferences," June 16, 2004. |

| 45. |

Ibid. |

| 46. |

Latin American Integration Association (ALADI) website, see http://www.aladi.org. |

| 47. |

Economist Intelligence Unit, Mexico Country Analysis, "Peso Dynamics after Trump," March 17, 2017. |

| 48. |

Ricardo Rascon, "Manufacturing in Mexico vs. China: 7 Key Differentiators," Offshore Group Insights, December 21, 2015. |

| 49. |

Ibid. |

| 50. |

Gabriel Stargardter, "Mexico Sees Trade Deals in TPP Leftovers, Flags China Opportunity," Reuters, November 22, 2016. |

| 51. |

Elizabeth Malkin, "Mexico Takes First Step Before Talks With U.S. on NAFTA," The New York Times, February 1, 2017. |