Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB)

In October 2013, at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Summit in Bali, Indonesia, China proposed creating a new multilateral development bank (MDB), the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). As its name suggests, the Bank's stated purpose is to provide financing for infrastructure needs throughout Asia, as well as in neighboring regions. As of January 2017, the AIIB has approved nine projects, investing a total of $1.7 billion.

The AIIB commenced operations on January 16, 2016. Membership in the AIIB is open to all members of the World Bank or the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The AIIB’s Articles of Agreement create two classes of membership: regional and non-regional members. According to the AIIB articles, regional members hold 75% of the total voting power in the Bank. Fourteen of the G-20 nations are AIIB members. The United States is not an AIIB member.

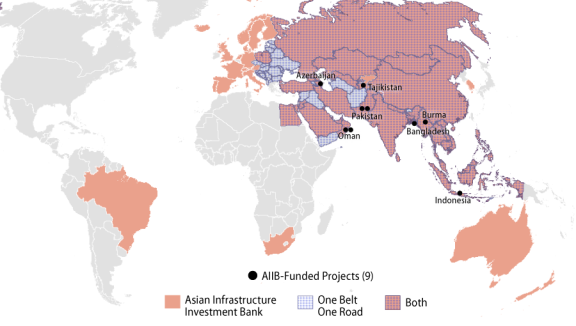

The AIIB was initially conceived as a regional financing mechanism for Chinese President Xi Jinping’s “One Belt, One Road (OBOR)” initiative. This initiative is a central component of President Xi’s regional economic and foreign policy and aims to boost economic connectivity from China to Central and South Asia, the Middle East, and Europe (the Silk Road Economic Belt) and, along a maritime route, from Southeast Asia to the Middle East, Africa, and Europe (the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road). President Xi, more than previous Chinese leaders, has pursued policies to establish new China-led trade and financial institutions, as well as to further integrate China within the existing international financial institutions. President Xi said that the AIIB would “promote interconnectivity and economic integration in the region” and “cooperate with existing multilateral development banks,” including the World Bank and the ADB.

As AIIB membership has expanded to include developed countries in Asia and Europe (and possibly Canada), China has since tried to distance the AIIB from the OBOR initiative through co-financing arrangements for its initial loans. It is uncertain how China will balance its stated goal of establishing an independent and high-standard MDB, while pursuing China’s own economic and national security priorities.

The AIIB's initial total capital is $100 billion, with 20% paid-in and 80% callable. China has subscribed to $29.7 billion as authorized under the Articles. India is the second-largest shareholder, contributing $8.4 billion. The Bank is based in Beijing, China, and headed by Jin Liqun, a former Chinese vice minister of finance, Chinese sovereign wealth fund chairman, and ADB vice president.

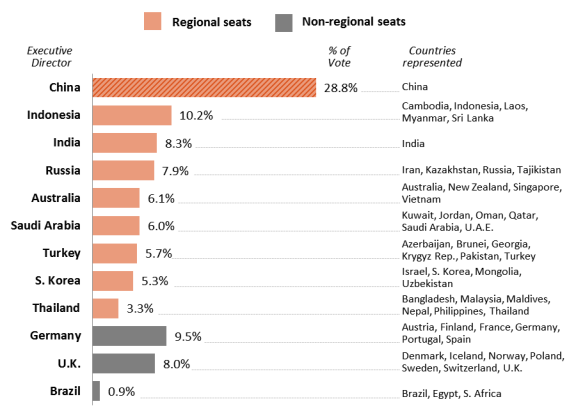

China's voting share at the AIIB (28.7%) is substantially larger than that of the second-largest AIIB member nation, India (8.3%). This is the largest gap between the first- and second-largest shareholders at any existing MDB. Voting share will reduce as remaining capital is subscribed by remaining permanent founding members and any new members. The AIIB has a governance structure similar to other MDBs.

The AIIB presents several policy issues for Members of Congress to consider, including

the future direction of the AIIB and potential U.S. role, including the question of whether the United States should join and U.S. policy toward the new institution;

independence, transparency, and governance of the bank and implications for other MDBs, particularly projects that are co-financed with other MDBs; and

commercial implications for U.S. firms, including procurement opportunities.

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB)

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- China's Motivation for Creating the AIIB

- Reforming Global Economic Governance

- MDB and Chinese Financing of Infrastructure

- AIIB Membership and Operations

- Membership

- Governance

- AIIB Presidency and Staff

- Capital Structure

- Operational Policies and Procedures

- AIIB Lending

- U.S. Policy Toward the AIIB

- Issues for Congress

- Oversight of the AIIB's Operations

- Potential U.S. Role

- Implications for MDB Governance

- Commercial Implications for U.S. Firms

Figures

Summary

In October 2013, at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Summit in Bali, Indonesia, China proposed creating a new multilateral development bank (MDB), the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). As its name suggests, the Bank's stated purpose is to provide financing for infrastructure needs throughout Asia, as well as in neighboring regions. As of January 2017, the AIIB has approved nine projects, investing a total of $1.7 billion.

The AIIB commenced operations on January 16, 2016. Membership in the AIIB is open to all members of the World Bank or the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The AIIB's Articles of Agreement create two classes of membership: regional and non-regional members. According to the AIIB articles, regional members hold 75% of the total voting power in the Bank. Fourteen of the G-20 nations are AIIB members. The United States is not an AIIB member.

The AIIB was initially conceived as a regional financing mechanism for Chinese President Xi Jinping's "One Belt, One Road (OBOR)" initiative. This initiative is a central component of President Xi's regional economic and foreign policy and aims to boost economic connectivity from China to Central and South Asia, the Middle East, and Europe (the Silk Road Economic Belt) and, along a maritime route, from Southeast Asia to the Middle East, Africa, and Europe (the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road). President Xi, more than previous Chinese leaders, has pursued policies to establish new China-led trade and financial institutions, as well as to further integrate China within the existing international financial institutions. President Xi said that the AIIB would "promote interconnectivity and economic integration in the region" and "cooperate with existing multilateral development banks," including the World Bank and the ADB.

As AIIB membership has expanded to include developed countries in Asia and Europe (and possibly Canada), China has since tried to distance the AIIB from the OBOR initiative through co-financing arrangements for its initial loans. It is uncertain how China will balance its stated goal of establishing an independent and high-standard MDB, while pursuing China's own economic and national security priorities.

The AIIB's initial total capital is $100 billion, with 20% paid-in and 80% callable. China has subscribed to $29.7 billion as authorized under the Articles. India is the second-largest shareholder, contributing $8.4 billion. The Bank is based in Beijing, China, and headed by Jin Liqun, a former Chinese vice minister of finance, Chinese sovereign wealth fund chairman, and ADB vice president.

China's voting share at the AIIB (28.7%) is substantially larger than that of the second-largest AIIB member nation, India (8.3%). This is the largest gap between the first- and second-largest shareholders at any existing MDB. Voting share will reduce as remaining capital is subscribed by remaining permanent founding members and any new members. The AIIB has a governance structure similar to other MDBs.

The AIIB presents several policy issues for Members of Congress to consider, including

- the future direction of the AIIB and potential U.S. role, including the question of whether the United States should join and U.S. policy toward the new institution;

- independence, transparency, and governance of the bank and implications for other MDBs, particularly projects that are co-financed with other MDBs; and

- commercial implications for U.S. firms, including procurement opportunities.

Introduction

In October 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced the establishment of a new China-led multilateral development bank, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), to "promote interconnectivity and economic integration in the region" and "cooperate with existing multilateral development banks," such as the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank (ADB).1 After two years of negotiations, the AIIB was formally established on December 25, 2015. The Bank currently has 52 members, including four G-7 economies (France, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom). The first AIIB-financed operations were approved by the Board of Directors at its June 2016 meeting. Approximately 25 additional countries are expected to join in 2017.2

According to the AIIB's Articles of Agreement:

The purpose of the Bank shall be to: (i) foster sustainable economic development, create wealth and improve infrastructure connectivity in Asia by investing in infrastructure and other productive sectors; and (ii) promote regional cooperation and partnership in addressing development challenges by working in close collaboration with other multilateral and bilateral development institutions.3

While there are large financing needs in the region, some observers question China's motives in establishing the AIIB, and argue that China is seeking to create an alternative to the World Bank and the ADB. As one non-Chinese individual involved in the AIIB negotiations told the Financial Times in June 2014, "China feels it can't get anything done in the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund so it wants to set up its own World Bank that it can control itself."4 A broader concern for the United States is the emergence of Chinese-led regional economic institutions, such as the AIIB, in which the United States has little influence, as alternatives to the World Bank and other long-established multilateral bodes in which the United States has historically led.5

Others see the AIIB proposal and other Chinese economic statecraft efforts as direct Chinese challenges to U.S. monetary and economic leadership.6 Instead of joining an MDB dominated by China and closely linked to China's foreign and economic policy goals, some analysts argue that the United States would be better served by supporting reforms at the World Bank and other MDBs to make the institutions more inclusive of developing country priorities and to make loans that are more attractive to borrower countries. These reforms could include shortening the time needed to approve loans, and reducing reporting requirements and loan conditionality.

China's Motivation for Creating the AIIB

The creation of the AIIB is part of a broader reorientation of Chinese foreign and international economic policy that has taken place since Xi Jinping became Chinese Communist Party General Secretary in 2012 and president in 2013.7 In contrast to his predecessor Hu Jintao, Xi has pursued an ambitious foreign policy agenda to deepen economic, security, and political ties with neighboring countries. Over the past several years, President Xi has spoken of building a "community of common destiny," first in the Asia-Pacific region and then throughout the globe.8 His overarching goal, according to one observer, is to

[L]everage China's economic power to build a network of new institutions, inspired by new ideas, to pursue new projects that will knit Eurasia, the South Pacific, and Eastern Africa into a tight network of economic, cultural, political, and strategic relationships.9

The centerpiece of Chinese foreign economic policy since 2013 is the "One Belt, One Road" (OBOR) initiative.10 A report released by the China International Trade Institute in August 2015 identified 65 countries along the Belt and Road that will be participating in the Initiative, which aims to use trade promotion, infrastructure development, and regional connectivity, to boost economic linkages between China and dozens of countries along a land route (the Silk Road Economic Belt) and a sea route (the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road).11 To realize this vision, China is investing in a range of institutions and initiatives, including the AIIB, and other funding mechanisms such as the Silk Road Fund and the New Development Bank (also known as the BRICS Bank), a collective arrangement with Brazil, Russia, India, and South Africa.12

China also seeks to influence the emerging structure of regional trade and investment relations. By helping to finance OBOR, AIIB may influence these relationships. It may also reinforce a regional infrastructure that has China as its hub. As a result, regional economies may be more inclined to augment trade and investment relations with China rather than with other economies, such as Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and the United States.

Reforming Global Economic Governance

While working to deepen its economic relationships with its neighbors through OBOR, China has also intensified its engagement with the "Bretton Woods Institutions"—the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the regional development banks—with the aim of reforming the governance and operations of these institutions to accommodate China's increased economic influence in the global economy.13

For many years, Chinese leaders have argued that international financial institutions have failed to recognize China's elevated stature in the global economy.14 While recent reforms have boosted China's contributions and voting shares, China remains underrepresented with respect to its weight in the global economy.15 Since beginning market-oriented economic reforms in the late 1970s, China has averaged nearly 10% real GDP growth a year and is now the second-largest global economy in nominal terms behind the United States.16

Some observers, including Members of Congress, have linked China's creation of the AIIB directly to the long delay in U.S. approval of IMF governance reforms, which among other things, increased China's financial contributions and voting power in the IMF.17 Despite approval by the IMF members in December 2010, Congress did not approve the reform package until 2015. While a full discussion of the reasons for the delay in IMF quota reform is outside the scope of this report, the delay contributed to a narrative that China was taking advantage of slow progress in reforming the main international financial institutions (IFIs) to build support for the AIIB.

MDB and Chinese Financing of Infrastructure

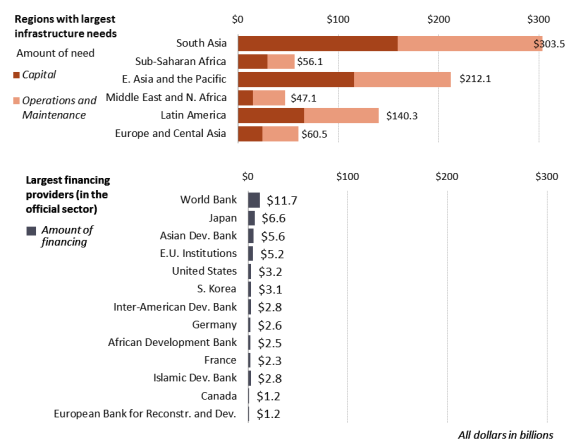

Many countries face substantial infrastructure needs. Demand continues to grow as the pace of economic growth and development increases and more of the population in developing countries moves out of rural areas into urban centers. In 2015, World Bank economists estimated global and regional infrastructure investment requirements needed to satisfy consumer and producer demand in developing countries through 2020.18 Their analysis found that developing countries would require annual investments of $819 billion to prevent a decrease in economic growth over the previous five-year period (2010-2015). South Asia and East Asia and the Pacific combined account for 63% ($516 billion) of the needed investment.19

In aggregate figures, the MDBs are among the largest providers of development support for infrastructure financing, although MDB financing for infrastructure has declined in recent decades (see text box). According to data compiled by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), total official support for infrastructure projects was $60 billion in 2013 and the World Bank was the largest provider, channeling $11.7 billion to infrastructure projects (Figure 1).

China has financed and built large-scale infrastructure projects, such as roads, dams, and water pipelines, throughout Asia, Africa, and Latin America, allegedly with little regard for social or environmental standards.20 Chinse projects also disproportionately use Chinese construction companies and laborers.21 This has led to criticism that Chinese assistance is undermining efforts by the United States and other countries to promote good governance and democracy in developing countries. Critics further charge that China's interest in providing development assistance and establishing the AIIB is self-serving, designed to enhance China's influence and access to raw materials, especially in Africa and Asia, at the expense of the United States. The AIIB, according to one observer, "can be seen as another prong in China's Monroe Doctrine, a signal that it should be free to call the shots in its own back yard."22

|

The Decline of Infrastructure Financing at the MDBs MDB lending for infrastructure projects has declined over the past several decades. The World Bank was explicitly created to support infrastructure development as part of the economic reconstruction of Europe after World War II. Infrastructure was also the primary focus for the regional development banks when they were established in the 1950s and 1960s. By the early 1980s, however, MDBs had begun shifting their focus away from heavy infrastructure lending. Since then, the MDBs have largely embraced a view of economic development, shared by the United States and other developed economies, that places a greater emphasis on developing a robust investment climate (legal, political, economic ministries, for example) in developing countries rather than on funding basic infrastructure.23 At the same time, nongovernmental interest groups have pressured the MDBs to "to rationalize major infrastructure projects on social and environmental grounds."24 The U.S. government considers policy conditionality, environmental and social safeguards, and measures such as rules on anti-corruption and best practices in procurement as being central to the effectiveness of development assistance, and has used its leadership in the MDBs to advance these priorities. Many MDB borrowers, however, view these conditions as restrictive. Setting aside the debate over the appropriate scope and content of MDB policy conditionality, the practical impact of these policies has been a shift, to a certain extent, away from financing infrastructure projects. Since the AIIB was proposed, however, the MDBs have reinvigorated their efforts to increase infrastructure financing in member countries.25 |

|

Figure 1. Annual Developing Country Infrastructure Needs (2015-2020) and Official Sector Financing (2013) |

|

|

Source: Data from IMF and the OECD, Graphic created by CRS. |

As Figure 1 illustrates, the need for infrastructure financing is far greater than the amounts that are currently being provided by the MDBs and other official sources. Addressing Asia's large infrastructure gap will thus require mobilizing a variety of public and private sources of financing, as well as engaging with new sources of long-term development finance. Efforts include the creation in 2012 of an Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Infrastructure Fund (AIF), which began lending in 2013. In October 2014, the World Bank launched a Global Infrastructure Facility (GIF) to facilitate the preparation and structuring of complex infrastructure public-private partnerships (PPPs) to mobilize private sector infrastructure investments.

AIIB Membership and Operations

Chinese President Xi Jinping first proposed the AIIB in October 2013, at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Summit in Bali, Indonesia. In October 2014, 21 regional countries met in China's capital, Beijing, and signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) that set out the general principles for the new bank. China set the deadline for expressing interest in becoming a founding member of the AIIB for the end of March 2015.

Initially, the United States government was opposed to the AIIB's creation and reportedly urged its allies and partners in Europe and in Asia not to join the AIIB, ostensibly because of concerns about the Bank's proposed policy guidelines and standards, and whether they would undermine existing MDB standards.26 U.S. officials were caught off-guard when, in early 2015, the United Kingdom, followed by several other European countries, sought membership in the AIIB.27 The Obama Administration later softened its criticism of the AIIB and would urge the other MDBs to work with the AIIB on the development of robust standards and practices.

As of March 2017, AIIB has 52 members.28 As AIIB membership grew to include European and other advanced economies, Chinese officials distanced the AIIB from China's OBOR initiative. During the early stages of the AIIB's creation, prior to the U.K.'s application, many OBOR documents explicitly referenced AIIB. In November 2014, shortly after China signed the MOU to begin negotiations, Chinese President Xi said that "China's inception and joint establishment of the AIIB with some countries is aimed at providing financial support for infrastructure development in countries along the 'One Belt, One Road' and promoting economic cooperation."29 This view of the AIIB's role was reinforced by the spokesperson for the National People's Congress in March 2015: "AIIB and the Silk Road Fund are both created for the better implementation of 'One Belt, One Road.'"30

Beginning in mid-2015, Chinese officials created more distance between the rapidly expanding AIIB and China's OBOR strategy. In June 2016, during a meeting with global executives, AIIB President Jin Liqun clarified China's position, saying that while the Bank would support OBOR projects, the AIIB was not created exclusively for this initiative. Speaking in Washington, DC, alongside the World Bank's spring 2016 meetings, President Xi said "We would finance infrastructure projects in all emerging market economies even though they don't belong to the Belt and Road initiative."31

China has also differentiated AIIB projects from its other foreign assistance projects by co-financing its initial projects with the preexisting MDBs.32 For example, according to a former director of economics at the National Security Council, co-financing, combined with European membership, "will make it more likely this institution largely conforms to the international standards" and potentially will steer the AIIB away from becoming solely a tool of Chinese foreign policy.33 It supports China's stated intention to complement existing MDBs rather than compete with them. It also means the AIIB can depend on its partners for expertise on a wide range of policy and procedural issues as it develops its lending portfolio.

Nonetheless, the AIIB's approved projects largely overlap with the geographic area of the OBOR initiative (see section below). Many initial projects are part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, a central component of OBOR (Figure 2).34 It is uncertain how China will balance its stated goal of establishing an independent and high-standard MDB with pursuing its own economic and national security priorities for the region.

|

|

Source: AIIB. Graphic by CRS |

Membership

Membership in the AIIB is open to all members of the World Bank or the ADB and is divided into regional and non-regional members. Regional members are those located within areas classified as Asia and Oceania by the United Nations. The AIIB allows for non-sovereign entities to apply for AIIB membership, assuming their home country is a member. Thus, sovereign wealth funds (such as the China Investment Corporation) or state-owned enterprises of member countries could potentially join the Bank. The AIIB has potentially 57 permanent founding members (Table 1).35 Over half of the members of the ADB have joined the AIIB and only two of the European ADB members have so far not joined (Belgium and Ireland). According to AIIB officials, approximately 25 additional countries are expected to join in 2017.36

|

Region |

Countries |

|

Southeast Asia (10) |

Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam |

|

Northeast Asia (3) |

China, Mongolia, South Korea |

|

South Asia (6) |

Bangladesh, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka |

|

Australasia (2) |

Australia, New Zealand |

|

Central Asia (5) |

Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan |

|

Middle East (9) |

Israel, Iran, Jordan, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates |

|

Africa (2) |

Egypt, South Africa |

|

Europe (19) |

Austria, Denmark, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom |

|

South America (1) |

Brazil |

|

Others (1) |

Hong Kong |

Source: AIIB website.

Japan has argued that until the AIIB has proven its adherence to international standards, any moves toward membership are premature.37 In August 2016, Canada became the first North American country to apply for membership.38 Canadian officials, like other advanced economies who joined the AIIB, argue that it is preferable to have a seat at the table during the establishment of the Bank and help ensure that the Bank adheres to international standards.39 Its application is under consideration.

Governance

The AIIB has a governance structure similar to the other MDBs, with two key differences: the AIIB does not have a resident board of executive directors, and the AIIB's articles give a larger degree of decisionmaking authority to regional countries and the largest shareholder country, China.40

The main MDBs typically have a board of governors, a board of executive directors (executive board), a president, and several vice presidents. The board of governors is the highest decisionmaking body and typically comprises treasury secretaries or finance ministers of member countries. The AIIB's board of governors, which consists of senior government officials from each member nation, is responsible for making major decisions involving, for example, changes in AIIB membership, election of the president, and whether to increase the capital of the institution.

Management of an MDB's day-to-day activities (approving loans, establishing policies, and overseeing MDB management) is typically delegated to a resident board of directors, which meets at least once a week. According to the articles, the AIIB's executive board comprises nine individuals elected by regional members and three elected by non-regional members. Each director has one or more alternate directors, depending on the number of countries in the constituency.41

While all AIIB lending projects, to date, have been submitted to the AIIB's board of directors for approval, the board is expected to consider at some point a delegation of authority to the president to approve certain projects.42 The AIIB's Articles of Agreement include the number of shares allocated to each AIIB member based on a formula that takes into account the size of the economy and whether they are a regional or non-regional member. The articles also include provisions to determine how voting power is determined (based on a country's shareholding) that are strongly based on weighted voting.

China is the largest shareholder of the AIIB and maintains a 28% voting share. The disparity in voting shares between China and other member countries is striking. China's voting share at the AIIB (28%) is over 350% that of the second-largest AIIB member nation, India (8%). This is currently the largest gap between the first- and second-largest shareholders at any of the MDBs, although the United States has the largest voting share in any single other MDB (30% at the Inter-American Development Bank). The largest shareholders after India are Russia (6%), Australia (4%), and Turkey (3%).43

Figure 3 illustrates the composition of the AIIB executive board and the total share of votes of each constituency. Unless the AIIB's Articles of Agreement expressly provide otherwise, executive board votes are decided by a majority of votes cast. Given China's 28% voting share, a majority of votes could be achieved with as few as four members voting in favor. For special votes, such as approving membership, selecting the president, increasing the capital stock of the AIIB, and changing the size or composition of the executive board, the Articles of Agreement require either a super majority (75% of total voting power with two-thirds of the membership) or a special majority (50% of total voting power with one-half of the membership) of the Board of Governors. As China will have more than a quarter of the votes, it will have an effective veto over these types of decisions. The United States has veto power over major governance decisions at the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank, and the IMF.

|

|

Source: AIIB, CRS. |

Since China proposed the AIIB and is its largest shareholder, it is not surprising that it is exerting political influence in the AIIB. One high-profile example is China's rejection of Taiwan's membership, despite its full membership in many other international organizations. The AIIB's articles state that any full ADB member can join the AIIB. Taiwan is a full ADB member under its preferred nomenclature "Taipei, China." China rejected Taiwan's application to be a founding member and has said that Taiwan can apply to be a regular member, but only if it asks China's Ministry of Finance to apply for membership on Taiwan's behalf, and if Taiwan uses an "appropriate name."44 The assumption is that China will want Taiwan to enter as a subregion of China. However, these discussions took place before the AIIB was formally established and may not be indicative of what would happen now that membership decisions are made by the AIIB's own governance organs.

In April 2016, Taiwanese officials announced that it would not seek membership in the AIIB and "Taiwan would only apply for AIIB membership if we could do it with equality and dignity."45 According to Rajiv Biswas, Asia Pacific chief economist of IHS Global Insight, "China's unilateral decision about Taiwan's membership indicates that China is essentially driving the decisionmaking, at least up to this stage, even though there are many other countries which have become founding members of the AIIB."46

Unlike the other MDBs (of which the United States is a member), in the AIIB the board of directors will function on a nonresident basis, except as otherwise decided by the board of governors. Some critics argue that the AIIB's nonresident board of directors, meeting once or twice a year, is substantially removed from the day-to-day activities of the institution and may be unable to focus on anything but the most important strategic decisions. Critics of the current resident executive boards at the IMF, the World Bank, and the regional development banks have, however, long argued that resident boards are too expensive to maintain, costing between 3% and 7% of the institutions' operating budgets.47 Proponents of resident boards argue they are essential for ensuring proper shareholder oversight, especially on matters of transparency and accountability. According to Robert Orr, a former U.S. executive director at the ADB:

[T]he AIIB is not a corporation, rather an institution that represents nation-states. The shareholders in the new bank therefore represent taxpayers, whose interests must be guaranteed. Without a permanent board that has day-to-day oversight, the bank's ability to ensure these interests are greatly diminished.48

AIIB Presidency and Staff

At the AIIB's inaugural board of governors meeting in January 2016, Mr. Jin Liqun of China was elected AIIB president for a five-year term. Prior to his selection as president-designate in September 2015, Jin served as secretary-general of the AIIB's Multilateral Interim Secretariat (MIS), the entity tasked with preparing the legal, policy, and administrative frameworks and undertaking other preparatory work required for the establishment of AIIB. Mr. Jin worked previously as chairman of China's first joint-venture investment bank, China International Capital Corporation, Ltd (CICC); chairman of the Supervisory Board of China's sovereign wealth fund, the China Investment Corporation (CIC); vice president of the ADB; and vice minister of China's Ministry of Finance.49 In addition to President Jin, the AIIB's senior management consists of five vice presidents and a general counsel, drawn from several AIIB member countries.50

Capital Structure

As a regional bank, the AIIB's regional members will hold the majority of the Bank's capital stock: a minimum of 75%, except as otherwise agreed by the board of governors. Other regional development banks, such as the African Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and Inter-American Development Bank, have similar arrangements.

The initial subscribed capital of the AIIB is $100 billion. As of the end of 2016, $89 billion was subscribed.51 Like other MDBs, the capital that shareholders contribute to the AIIB (as well as the other MDBs) comes in two forms: "paid-in capital," which generally requires the payment of cash to the MDB; and "callable capital," funds that shareholders agree to provide, but only when necessary to avoid a default on a borrowing or payment under a guarantee. Callable capital serves as ultimate backing for MDB borrowing in capital markets, though the MDBs have never called upon those resources. Callable capital cannot be used to finance loans, but only to pay off bondholders if the MDB is insolvent and unable to pay its bondholders.

At 20% of total capital, the AIIB will have a much higher share of paid-in capital than the World Bank and other MDBs. Out of $20 billion in initial authorized AIIB paid-in capital, $19.6 billion is already committed.52

The World Bank and the regional development banks began their operations with 20%-50% paid-in capital. This figure has fallen to around 5% for most of the MDBs, with the exception of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). After the 2008 financial crisis, MDB member countries approved $350 billion in capital increases for the MDBs, but only agreed to pay in $15 billion, 4.2% of the total capital increase.53 As a result of its large percentage of paid-in capital, the AIIB would be able to ramp up lending quickly. According to analysis prepared by the Overseas Development Institute, the AIIB could conservatively achieve a portfolio of around $120 billion by 2025.54 An AIIB portfolio of $120 billion would be larger than any of other regional MDBs and almost as large as the World Bank's non-concessional lending window ($167.76 billion as of FY2016).

Operational Policies and Procedures

Responding to concerns about the AIIB's governance, the AIIB website announces that the AIIB will be "lean, clean, and green":

AIIB's modus operandi is "lean, clean and green: lean with a small efficient management team and highly skilled staff; clean, an ethical organization with zero tolerance for corruption; and green, an institution built on respect for the environment."55

Whether the AIIB embraces strong environmental and social safeguards, and other policy-related conditions, remains a concern for many analysts, including Members of Congress, who played a major role in establishing robust safeguard policies at the MDBs and have used U.S. leadership at the institutions to advance best practices on these issues. These reforms have been instrumental in reducing the impact of MDB projects on local communities and limiting MBD funding for carbon-intensive energy projects, as well as stopping projects where corruption was apparent. At the same time, according to Yukon Huang, a former World Bank director for operations in Asia and Europe, many standards and procedures of existing MDBs are "frustratingly bureaucratic, costly and ill-suited to dealing with the real needs of client borrowers."56

Recent research finds that many developing countries increasingly avoid seeking MDB financing, especially for large infrastructure projects that trigger safeguards policies, a long-standing priority for the United States and other advanced economies at the MDBs.57

Overall, it is too early to assess the impact of the AIIB's performance standards, especially since the AIIB's co-financed projects are required to adhere to the partner agency's safeguards. However, since the AIIB is China's first foray into leading an MDB and China has many other vehicles to finance overseas infrastructure projects, many observers expect China to follow best practices at the AIIB. According to one Chinese analyst, "One thing is certain: the AIIB is determined to avoid reputational damage by making mistakes in its first projects."58 To date, the AIIB has published several operational policies, including an Environmental and Social Framework (ESF) and policies on procurement and preventing corrupt practices, among others.

For example, the AIIB's Environmental and Social Framework (ESF) was approved in February 2016, with the possibility for updates after the first three years of AIIB operations. Environmental groups were invited to comment on a draft of the framework. According to the World Resources Institute, a global environmental research organization:

[T]he Framework's vision recognizes many of the issues such as climate change, gender, biodiversity and ecosystems, resettlement, labor practices and Indigenous Peoples that AIIB will encounter as it begins to make investments. It also makes very important commitments around transparency, information disclosure and public participation that exceed those of a number of national development banks, including key players such as the China Development Bank and the China Export-Import Bank.59

Other observers were more critical, pointing out concerns including

[T]he reliance on corporate and country systems; lack of detail on the AIIB's oversight mechanism; the omission of coal from its exclusion list; its adoption of the phased approach, which allows plans for impacts on indigenous groups to be made after project approval; and the lack of mandatory environmental or social impact assessments for projects in Category B, defined as having limited environmental and social impacts.60

In October, 2016, the AIIB joined a statement by the heads of the IMF and the other MDBs affirming that their operations would be grounded in the latest international agreements on sustainable development (the 2015 Paris Agreement on Climate Change and the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development).61

AIIB Lending

According to the AIIB's articles, recipients of AIIB financing may include member countries (or agencies and entities or enterprises in member territories), as well as international or regional agencies concerned with the economic development of the Asia-Pacific region.

The AIIB has signed a co-financing framework agreement with the World Bank and three non-binding Memoranda of Understanding with the ADB, EBRD, and the European Investment Bank (EIB). To date, the AIIB has approved nine projects worth $1.7 billion, most of which are being co-financed with established MDBs (Table 2). No procurement information on these projects is currently available. It is unclear if information on which firms are winning projects and related procurement information will be made publically available.

According to documents prepared for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), AIIB officials foresee its lending program growing to $1.5-$2.5 billion in 2017 and $2.5-$3.5 billion in 2018.62 Despite recent distancing from China's OBOR initiative by Chinese and AIIB leadership, many of the approved projects are closely aligned with the OBOR initiative. The project pipeline for the next two years includes projects in Azerbaijan, Georgia, India, Indonesia, and Oman, among others.

Denmark and the United Kingdom requested that AIIB lending be included in the OECD's statistics on Official Development Assistance (ODA), a multilateral "stamp of approval" of the quality of the AIIB's activities. In March 2016, the Secretariat of the OECD's Development Advisory Committee reported that a review of the AIIB's mandate, activities, and budget supports the AIIB's inclusion in the ODA statistics.63 To date, the OECD has not taken any decisions on the matter.

|

Project Name |

Country |

Sector |

Partner |

Project size |

AIIB funding |

|

Myingyan power plant |

Myanmar |

Energy |

IFC/ADB |

N/A |

$20m |

|

Tarbela 5 hydropower extension |

Pakistan |

Energy |

World Bank |

$824m |

$300m |

|

National motorway M-4 |

Pakistan |

Transport |

ADB/DFID |

$273m |

$100m |

|

Distribution system upgrade |

Bangladesh |

Energy |

None |

$262m |

$165m |

|

Dushanbe-Uzbekistan border road |

Tajikistan |

Transport |

EBRD |

$106m |

$28m |

|

National slum upgrading |

Indonesia |

Urban infrastructure |

World Bank |

$1.7bn |

$217m |

|

Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline |

Azerbaijan |

Energy |

World Bank |

$8.6bn |

$600m |

|

Duqm Port Commercial Terminal |

Oman |

Transport |

None |

$353m |

$265m |

|

Railway System Preparation |

Oman |

Transport |

None |

$36m |

$60m |

U.S. Policy Toward the AIIB

Some observers have criticized the U.S. approach toward the AIIB during the Obama Administration. The criticism is well captured by Evan Feigenbaum, a former State Department official in the George W. Bush Administration, who has written that, "The U.S. attempt to halt or marginalize the AIIB failed miserably."64 Feigenbaum and others argue that the United States erred by resisting China's efforts and should have welcomed the institution when it was proposed or should join it now in order to help shape its policies and procedures.65 In a bipartisan-chaired report making economic policy recommendations for the Trump Administration, the Center for Strategic & International Studies writes:

[I]n recognition of Asians' desire for more ownership of regional economic architecture, the new administration should consider some form of U.S. participation in the AIIB.66

According to a November 2016 report from the Institute for the Analysis of Global Security,

Now that the bank is in operation and that it has taken encouraging steps to demonstrate its transparency and fidelity the United States should consider changing its approach toward it and take steps toward joining it. A U.S. accession of the AIIB would be an important gesture. Most important, it would signal to private sector players that it is safe to invest in projects co-financed by the AIIB.67

Others argue that the Obama Administration's focus on AIIB transparency and best practices was appropriate and provided constructive pressure on China. For example, China's efforts to integrate AIIB financing into the existing development system were praised by Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew at a March 2016 hearing before the House Appropriations Committee, where he took credit for pushing the Chinese to adopt high standards at the AIIB:

[O]ur position on the Asian Infrastructure bank has been, on the one hand, we think it's a good thing that there's more support for international infrastructure investment in Asia. But it's very important that it be done in a way that's consistent with standards, like the standards that we pursue in our multilateral development banks that we're involved in.

We have made that case to all the participants; we've made that case to the Chinese. And I think we've had a lot of success. They have now adopted operating rules that are very much leaning towards observing the kinds of norms that we support in the multilateral institutions that we contribute to.

But now the question is what the actions will be. And we'll start to know when they make loans. The more they partner with the multilateral institutions that have high standards, the more likely they are to operate in a way that's consistent with the kinds of norms that are good for a growing, global economy and other values that we pursue in the multinational space.68

Turning to potential U.S. participation, the AIIB maintains that it is open to U.S. membership.69 Some analysts argue that the U.S. government should reconsider its position and consider joining the AIIB.70 David Dollar, a former World Bank economist and senior official in President Obama's Department of the Treasury, has emerged as one of the AIIB's main boosters in Washington, DC, and has argued that joining would be a "good investment" for the United States.71

Issues for Congress

The establishment of AIIB raises several political and economic issues for Congress as it examines the AIIB's activities and considers potential U.S. involvement with the Bank.

Typically, Congress exercises its influence over MDB policy through its control over authorizations and appropriations, as well as through oversight. The authorizing committees have included in MDB authorizing legislation many directives which affect the goal and direction of U.S. policy. Congress has also used its control over the funding process—its "power of the purse"—to set priorities and encourage the Administration and MDBs to consider changes in their policies or procedures.

Congress has used hearings and required reports to get information about U.S. policy and the MDBs into the public record and to draw the Treasury Department's attention to issues of pressing concern. Since the Administration knows it must come to Congress for future authorizations and MDB funding, the views expressed by Congress through hearings have often had an impact on the focus and direction of U.S. policy regarding particular concerns.

While the United States is not a member of the AIIB, and thus will not be authorizing and appropriating financial contributions, there are several avenues through which Congress can shape U.S. policy toward the institution. These include oversight of the AIIB's operations and shaping the evolving relationship between the AIIB and the MDBs where the United States is a member.

Oversight of the AIIB's Operations

Members of Congress may want to follow the AIIB's initial group of projects to gain a better understanding of whether and to what extent China is using the AIIB to finance its political and economic priorities in the region. Chinese officials see economic development in the region as helping to guard against regional instability (e.g., in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Central Asia) and to deepen regional political and economic linkages to Beijing.

Members may also consider looking at the possible impact of AIIB financing for regional infrastructure, interconnectivity, and trade relations. The strategic or security issues raised by greater economic linkages between China and developing countries in Central and South Asia may are also worth considering. For example, Members may consider how the AIIB may facilitate a reordering of Asian trade and investment relations toward China.

Regional Chinese infrastructure financing may also serve to channel China's overcapacity in its manufacturing and construction sectors. Over the past decade, China has devoted around half of its GDP to domestic investment. If the current slowdown in the Chinese economy continues, regional infrastructure financing would be a way to redirect China's excess capacity in sectors such as rail and highways or port construction.

China's efforts on behalf of the AIIB also raise questions about China's relationship with the existing MDBs, where it remains a large borrower ($390 million of operations were approved in 2016).72 Critics question why China still borrows large volumes from the MDBs, often for infrastructure projects, yet believes it has sufficient management expertise to lead a new MDB. Meanwhile, China continues to support its own large national development banks such as the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China.

Potential U.S. Role

Members of Congress could consider possible ways to participate with the AIIB beyond the co-financing of projects between the AIIB and U.S.-led institutions such as the World Bank and the ADB. Members of Congress could recommend that the President pursue membership in the institution or direct the Treasury Department to report on the feasibility and costs and benefits of U.S. membership in the institution. Members could consider ways to influence the AIIB's activities outside of joining, such as encouraging further co-financing arrangements and/or participating as an observer.

Another option to facilitate U.S. cooperation with the AIIB would be to extend diplomatic privileges and immunities to AIIB personnel. As international organizations have become increasingly important for multilateral relations and cooperation, representatives to and employees of such organizations have occasionally been granted privileges and immunities similar to those traditionally accorded to diplomats or consular officials. The International Organizations Immunities Act (IOIA) provides a significant number of privileges and immunities for international organizations designated by the President, such as immunity from suit for its official acts, and tax benefits that could make it easier for AIIB to invest and raise funds in U.S. markets, among other things. Covered institutions include the United Nations, IMF, World Bank, and several dozen other international organizations; the United States is not a member of some of these organizations.73 For example, the United States is not a member of the African Union.74 In 2007, President Bush extended diplomatic immunities and privileges to the African Union Mission to the United States.75

Others argue that U.S. officials should focus their efforts on increasing the attractiveness of the World Bank and the other MDBs where the United States is a dominant member, by advocating for and approving greater representation by developing countries in the institutions and embracing innovative financing mechanisms, such as the World Bank's Program-for-Results, which seeks to promote greater reliance on domestic regulatory regimes while linking finance to performance and development outcomes.76

Members might also want to consider a broader review of the MDB system in light of the proliferation of sources of development finance. Compared to 15 or 20 years ago, when the MDBs and other traditional donors provided the bulk of development assistance, the current environment is characterized as an "age of choice," with a variety of new donors, multilateral funds, private investment funds, etc.77 In light of the new landscape for development finance, Members may consider whether MDBs are still a preferred means for providing official development assistance. Members may also want to consider the extent to which there may be duplication of efforts across the MDBs, and the role of private financing.

Implications for MDB Governance

Several operational aspects of the proposed AIIB raise concerns for some U.S. officials. China's large voting power combined with the AIIB's nonresident executive board has led some analysts to question the AIIB's independence from Chinese leaders. The exact nature of the relationship between the AIIB and China's domestic foreign and economic policy agenda remains unclear.

Prior to the establishment of the AIIB, China, through its bilateral aid, has supported large-scale infrastructure projects throughout Asia often with less regard to social or environmental standards, or the underlying institutions in the recipient country. Some observers are concerned that some developing countries will resist the safeguards and conditions attached to World Bank or ADB loans and turn to the AIIB instead.78 Other analysts stress that the AIIB's safeguards policies and operating procedures are largely drawn from the policies of the other MDBs, and have been largely well received by the official and NGO community. Since most of the AIIB's initial projects are co-financed with more established MDBs and must follow their safeguards and standards, it is still too early to evaluate the AIIB's compliance with its own stated policies.

Commercial Implications for U.S. Firms

Members might want to consider the implications for U.S. firms if the AIIB facilitates the emergence of China-focused regional standards or norms. For example, if Chinese policymakers use the AIIB to install network and telecommunications equipment made by the Chinese companies Huawei and ZTE throughout the Asia-Pacific region, U.S. technology firms might be effectively kept out of the Asia-Pacific market.

Members of Congress may also want to follow the procurement contracting for the AIIB's initial projects. While China has issued assurances that there will be open and transparent procurement, and the AIIB has issued procurement policies and guidelines in January and July 2016, it remains uncertain to what extent firms from non-AIIB member countries will be considered and/or chosen for bidding on AIIB projects.79 Will U.S. firms be able to bid fairly and participate in projects funded by the AIIB? As with MDB governance policies, it remains too early to evaluate the AIIB's commitment to open and transparent procurement.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

"President Xi Jinping Holds Talks with President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono of Indonesia," Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China, October 2, 2013. |

| 2. |

James Kynge and David Pilling, "China-Led Investment Bank Attracts 25 New Members," Financial Times, January 24, 2017. |

| 3. |

Articles of Agreement, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. |

| 4. |

Jamil Anderlini, "China Expands Plans for World Bank Rivals," Financial Times, June 24, 2014. |

| 5. |

For example, China is actively involved in negotiations on a Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) among the ten members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and their trade agreements partners. For more information, visit https://aric.adb.org/fta/regional-comprehensive-economic-partnership. |

| 6. |

Sabrina Snell, China's Development Finance: Outbound, Inbound, and Future Trends in Financial Statecraft, U.S.-China Economic, and Security Review Commission, Washington, D.C., December 16, 2015. |

| 7. |

For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10029, China, U.S. Leadership, and Geopolitical Challenges in Asia, by Susan V. Lawrence. |

| 8. |

Jin Kai, "Can China Build a Community of Common Destiny?" The Diplomat, November 28, 2013. |

| 9. |

William A Callahan, "China's "Asia Dream"; The Belt and Road Initiative and the new regional order," Asian Journal of Comparative Politics, vol. 1, no. 3 (2016), pp. 226-243. |

| 10. |

CRS In Focus IF10273, China's "One Belt, One Road", by Susan V. Lawrence and Gabriel M. Nelson. |

| 11. |

Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, the National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Ministry of Commerce of the People's Republic of China, March 2015. |

| 12. |

Kevin P. Gallagher, Rohini Kamal, Yongzhong Wang and Yanning Chen, "Fueling Growth and Financing Risk," Boston University Global Economic Governance Initiative, Working Paper 002, May 2016. See also, Kevin P. Gallagher and Amos Irwin, "Exporting National Champions: China's OFDI Finance in Comparative Perspective," China and the World Economy, Vol. 22., Is. 6. 2014. See also, Deborah Brautigam, Testimony on China's Growing Role in Africa before the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Subcommittee on African Affairs, November 1, 2011. |

| 13. |

Honying Yang, From "Taoguang Yanghui" to "Yousuo Zuowei": China's Engagement in Financial Minilateralism, Center for Global Governance Innovation, CIGI Working Paper No. 52, Waterloo, Canada, December 12, 2014. See also, Hai Yang, "The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and Status-Seeking: China's Foray into Global Economic Governance," China Political Science Review, October 20, 2016. |

| 14. |

"China's calls for reform at the World Bank, IMF and ADB cannot be ignored any longer," South China Morning Post, September 12, 2016. |

| 15. |

Alex He, The Dragon's Footprints: China in the Global Economic Governance System (McGill-Queens University Press, 2016). |

| 16. |

CRS Report RL33534, China's Economic Rise: History, Trends, Challenges, and Implications for the United States, by Wayne M. Morrison. |

| 17. |

CRS In Focus IF10134, IMF Quota and Governance Reforms, by Martin A. Weiss and Rebecca M. Nelson. |

| 18. |

Fernanada Ruiz-Nunez and Zichao Wei, Infrastructure Investment Demands in Emerging Markets and Developing Economies, World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper 7414, Washington, DC, September 2015. |

| 19. |

Ibid. |

| 20. |

Kevin P. Gallagher, Rohini Kamal, Yongzhong Wang and Yanning Chen, "Fueling Growth and Financing Risk," Boston University Global Economic Governance Initiative, Working Paper 002, May 2016. |

| 21. |

Clifford Krauss and Keith Bradsher, "China's Global Ambitions, Cash and Strings Attached," The New York Times, July 24, 2015. |

| 22. |

Yoichi Funabashi, "A Futile Boycott of China's Bank Will Not Push Xi Out of His Back Yard," Financial Times, December 9, 2014. |

| 23. |

Christopher Humphrey, Infrastructure Finance in the Developing World: Challenges and Opportunities for Multilateral Development Banks in 21st Century Infrastructure Finance, Intergovernmental Group of Twenty Four/Global Green Growth Institute, Seoul, Korea, June 2015. |

| 24. |

Ibid. |

| 25. |

For example, see G20 Development Working Group and G20 Investment and Infrastructure Working Group, Partnering to Build a Better World: MDB's Common Approach to Supporting Infrastructure Development, September 18, 2015. |

| 26. |

Jamil Anderlini, "Big Nations Snub Beijing Bank Launch after US Lobbying," Financial Times, October 23, 2014. |

| 27. |

Nicholas Watt, Paul Lewis, and Tania Branigan, "US anger at Britain joining Chinese-led investment bank AIIB," The Guardian, March 13, 2015. |

| 28. |

The AIIB's Articles of Agreement were opened for signature on June 29, 2015. 50 countries signed that day and an additional seven signed before the end of year deadline. Membership for these Signatories requires signing and ratification. As of March 2017, AIIB has 52 members. The deadline for the remaining five signatories to complete ratification was December 31, 2016 and was extended to December 31, 2017 by decision of the Board of Governors. |

| 29. |

Quoted in Yun Sun, "China and the Evolving Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank," in Daniel Bob, ed. Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: China as Responsible Stakeholder, Sasakawa USA, 2015. |

| 30. |

Ibid. |

| 31. |

Zhong Nan and Cai Xiao, "AIIB Leas support for Belt and Road Infrastructure Projects," China Daily, June 8, 2016. |

| 32. |

Ibid. |

| 33. |

Matthew Goodman, quoted in Ian Talley, "U.S. Looks to Work with China-Let Infrastructure Fund," The Wall Street Journal, March 22, 2015. |

| 34. |

A listing of these projects can be found at http://euweb.aiib.org/html/2016/PROJECTS_1010/163.html. |

| 35. |

Of the 57 founding members, all but five countries have ratified the AIIB's Articles of Agreement: Brazil, Kuwait, Spain, South Africa and Uzbekistan. The ratification status of prospective AIIB founding members are available at http://euweb.aiib.org/html/aboutus/introduction/Membership/?show=0. |

| 36. |

James Kynge and David Pilling, "China-Led Investment Bank Attracts 25 New Members," Financial Times, January 24, 2017. |

| 37. |

Kazuyuki Suwa, Japan's AIIB Quandary, The Tokyo Foundation, August 3, 2015. |

| 38. |

Pei Li, "Canada Applies to Join AIIB," The Wall Street Journal, August 31, 2016. |

| 39. |

Jane Perlez, "Canada to Join China-Led Bank, Signaling Readiness to Bolster Ties," The New York Times, August 31, 2016. |

| 40. |

Mike Gallagher and Paul Hubbard, "The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: Multilateralism on the Silk Road," China Economic Journal, vol. 9, no. 2 (2016). |

| 41. |

The nations currently represented on the AIIB Board of Directors are; Australia, China, Egypt, Germany, India, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Russia, Thailand, Turkey, and the United Kingdom. |

| 42. |

AIIB Operational Policy on Financing, January 2016. |

| 43. |

AIIB Membership, shareholding and voting power is available at http://euweb.aiib.org/html/aboutus/governance/MoB/?show=1. |

| 44. |

Cheng Ting-Fang, "Taiwan rejects joining AIIB under China's supervision," Nikkei Asian Review, April 13, 2016. |

| 45. |

Ibid. |

| 46. |

Kit Tang, "China says no to Taiwan on AIIB: What it means," CNBC, April 14, 2015. |

| 47. |

Leonardo Martinez-Diaz, "Executive Boards in International Organizations: Lessons for Strengthening IMF Governance," International Monetary Fund, Independent Evaluation Office, Background Paper 08, May 2008. |

| 48. |

Robert M. Orr, Why the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank needs resident directors, Chinadialogue, August 23, 2016. |

| 49. |

"AIIB President Mr. Jin Liqun," Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank website, http://euweb.aiib.org/html/aboutus/governance/president/. |

| 50. |

"AIIB Vice Presidents and General Counsel," Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank website, http://euweb.aiib.org/html/aboutus/governance/Senior_Management/Vice_Presidents/?show=1. |

| 51. |

Several countries are in the process of completing the AIIB's membership process: Iran, Kuwait, Malaysia and Philippines (Regional); and Brazil, Portugal, South Africa and Spain (non-Regional). A table showing the Membership status of Founding Signatories to the Bank's Articles is available at http://euweb.aiib.org/html/aboutus/governance/Membership/?show=1. |

| 52. |

Chris Humphrey, "Will the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank's Development Effectiveness Be a Victim of China's Diplomatic Success?" in "Multilateral Development Banks in the 21st century: Three Perspectives on the China and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank," Overseas Development Institute, November 2015. |

| 53. |

CRS Report R41672, Multilateral Development Banks: General Capital Increases, by Martin A. Weiss. |

| 54. |

Ibid. Assumptions include: return on equity of 3.5% per year, equity/loans ratio of 20%, no returns on lending for first two years and paid-in capital of $19.6 paid in over five years. Depending on how the AIIB manages its finances, this figure could grow even higher. |

| 55. |

AIIB website. |

| 56. |

Yukon Huang, "China has a role to play in setting the 'right' standards," Financial Times, April 8, 2015. |

| 57. |

Christopher Humphrey, "Time for a new approach to environmental and social protection at multilateral development banks," Overseas Development Institute, April 2016. |

| 58. |

Liu Qin, "China-led development bank careful to co-operate with critics," Thethirdpole.net, August 5, 2016. |

| 59. |

Gaia Larson and Sean Gilbert, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank Releases New Environmental and Social Standards. How Do They Stack Up?" World Resources Institute, March 4, 2016. |

| 60. |

Rohini Kamal and Kevin Gallagher, "China Goes Global with Development Banks," Bretton Woods Project, April 5, 2016. |

| 61. |

Delivering on the 2030 Agenda, October 9, 2016. |

| 62. |

OECD DAC Working Party on Development Finance Statistics, Proposals for changes to Annex 2 of the Converged Statistical Reporting Directives for the Creditor Reporting System (CRS) and the Annual DAC Questionnaire, March 16, 2016. |

| 63. |

Ibid. |

| 64. |

Evan Feigenbaum, "China and the World," Foreign Affairs, January/February 2017. |

| 65. |

James Woolsey Jnr., "Under Donald Trump, the US will accept China's rise – as long as it doesn't challenge the status quo," South China Morning Post, November 10, 2016. Jim Zarolli, "New Asian Development Bank Seen As Sign Of China's Growing Influence," National Public Radio, April 16, 2015. |

| 66. |

Charlene Barshefsky, Evan G. Greenberg, and Jon Huntsman Jr., Reinvigorating U.S. Economic Strategy in the Asia Pacific, Center for Strategic & International Studies, Washington, DC, January 2017. |

| 67. |

Gal Luft, China's One Belt One Road Initiative: An American Response to the New Silk Road, Institute for the Analysis of Global Security, November 2016. |

| 68. |

House Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs, Budget Hearing - Department of Treasury International Programs, March 15, 2016. |

| 69. |

"AIIB's Jin Says Bank's Door Still Open to Trump After Obama Snub," Bloomberg, January 8, 2017. |

| 70. |

"China on the World Stage: A bridge not far enough," The Economist, March 21, 2015. |

| 71. |

Chen Weihua, "AIIB is 'good investment for US'" China Daily USA, October 20, 2016. |

| 72. |

Data on China's lending from the World Bank is available at http://data.worldbank.org/country/china. |

| 73. |

International Organizations Immunities Act, 22 U.S.C. § 288 et seq. For more information, see Aaron I Young, "Deconstructing International Organization Immunity," Georgetown Journal of International Law, vol. 44, 2012. |

| 74. |

CRS Report R44713, The African Union (AU): Key Issues and U.S.-AU Relations, by Nicolas Cook and Tomas F. Husted. |

| 75. |

Exec. Ord. No. 13444, September 12, 2007, 72 Fed. Reg. 52747. |

| 76. |

Scott Morris, "Responding to AIIB," Council on Foreign Relations, September 2016. |

| 77. |

Romily Greenhill, Annalisa Prizzon, and Andrew Rogerson, "The age of choice: developing countries in the new aid landscape," Overseas Development Institute, January 2013. |

| 78. |

Paola Subacchi, "The AIIB Is a Threat to Global Economic Governance," Foreign Policy, March 31, 2015. |

| 79. |

The AIIB's Procurement Policy is available at http://www.aiib.org/uploadfile/2016/0226/20160226051326635.pdf. For more information, see Jedrzej Gorski, An Update on AIIB's Procurement Regulations, Procurement Policy and Co-operation with Other Multilateral Development Banks, Centre for Financial Regulation and Economic Development, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Working Paper No. 17, May 2016. |