Export-Import Bank: Overview and Reauthorization Issues

The Export-Import Bank of the United States (Ex-Im Bank or the Bank)—commonly referred to as the official export credit agency (ECA) of the United States—provides financing and insurance to facilitate the export of U.S. goods and services to support U.S. jobs. Ex-Im Bank, a wholly owned U.S. government corporation, operates pursuant to a renewable statutory charter (Export-Import Bank Act of 1945, as amended; 12 U.S.C. §635 et seq.), and also abides by international rules on ECA financing under the Organization for Economic Cooperation for Development (OECD). The Bank aims to provide support in two circumstances:

to fill gaps in the market—when the private sector is unwilling or unable to provide financing for U.S. exports; or

to counter foreign ECA competition—when U.S. exporters face competition from foreign businesses backed by foreign ECAs.

The activities of the Bank are “demand-driven,” meaning they depend on private sector demand and interest for such government support. Ex-Im Bank charges interest, premia, and other fees for its services. Ex-Im Bank’s rationales and activities are subject to legislative and policy debate.

In the 116th Congress, Senate confirmations to positions on the Board of Directors of the Bank restored a quorum of the Board and reinstated the Board’s full authority, including to approve financing transactions above $10 million with repayment terms of seven years or longer, generally for the first time in nearly four years.

Ex-Im Bank’s charter is scheduled to sunset on September 30, 2019, unless Congress takes action. Potential issues for the 116th Congress include whether to reauthorize Ex-Im Bank and, if so, under what terms, as well as Senate consideration of additional Board nominations and congressional consideration of reauthorizing Ex-Im Bank.

In deliberating on Ex-Im Bank’s authorization status, potential options for Congress include a “clean” extension of Ex-Im Bank’s sunset date (12 U.S.C. §635f), an extension with limited or significant changes to the charter, or other options, such as allowing the charter to lapse, terminating the Bank and setting specific parameters for a wind-down of Ex-Im Bank’s functions, or reorganizing its functions in the context of overall U.S. export promotion and financing activities of the federal government.

Potential issues for Congress include:

What should be the purpose of Ex-Im Bank? What are the economic, foreign competition, and other policy justifications for and against Ex-Im Bank?

What length of time is desirable for an extension of Ex-Im Bank’s charter?

What should be Ex-Im Bank’s exposure cap?

Are modifications needed to the Board of Director terms, succession rules, or quorum?

Should the scope of policy criteria for Ex-Im Bank be revisited?

Should Ex-Im Bank programs, policies, and/or risk management practices be modified?

Is Ex-Im Bank competitive with foreign ECAs? Do current international rules on export credit financing support U.S. policy goals, or are changes needed?

Export-Import Bank: Overview and Reauthorization Issues

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Select Developments on Reauthorization

- Background

- Historical Overview

- Authorization Status

- Board of Directors Leadership

- Ex-Im Bank in Context

- Requirements for Ex-Im Bank Financing and Insurance Support

- Financial Products

- Direct Loans

- Medium- and Long-Term Loan Guarantees

- Working Capital and Supply Chain Guarantee Programs

- Export Credit Insurance

- Specialized Finance Products

- Activity and Portfolio Exposure

- Appropriations and Budget

- Risk Management

- International Context

- Debate Over Ex-Im Bank

- Economic Issues

- International Competition Issues

- Potential Issues for Congress

Figures

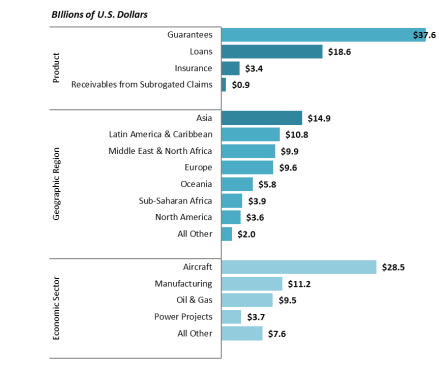

- Figure 1. Ex-Im Bank Direct Loan Structure

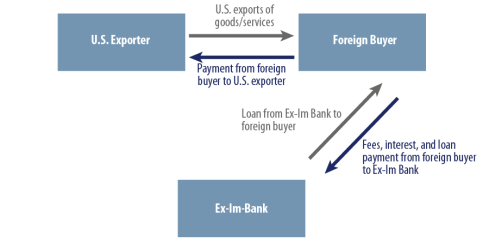

- Figure 2. Ex-Im Bank Loan Guarantee Structure

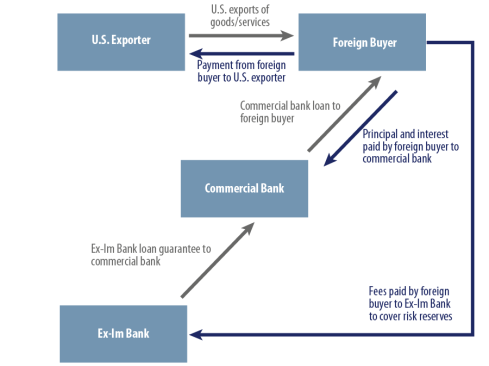

- Figure 3. Ex-Im Bank Exporter Insurance Structure

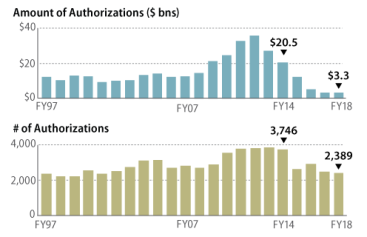

- Figure 4. Ex-Im Bank Authorizations, FY1997-FY2018

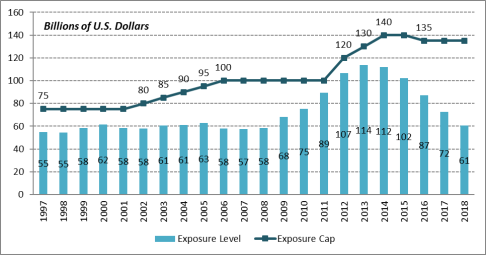

- Figure 5. Ex-Im Bank Exposure Levels and Exposure Cap, FY1997-FY2018

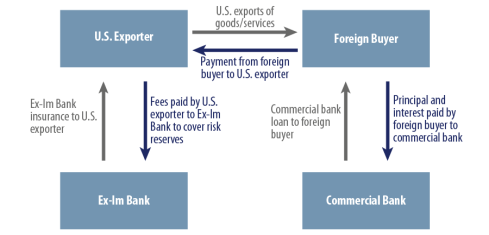

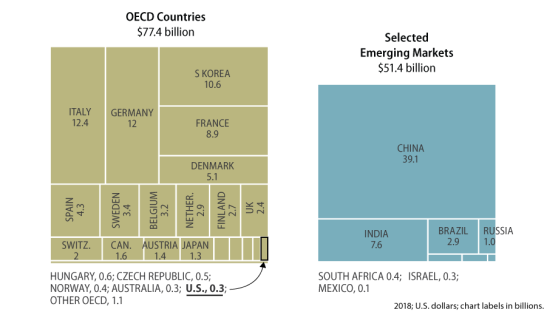

- Figure 6. Ex-Im Bank Exposure Level by Product, Region, and Sector, FY2018

- Figure 7. Export Financing by Selected ECAs in 2018

Summary

The Export-Import Bank of the United States (Ex-Im Bank or the Bank)—commonly referred to as the official export credit agency (ECA) of the United States—provides financing and insurance to facilitate the export of U.S. goods and services to support U.S. jobs. Ex-Im Bank, a wholly owned U.S. government corporation, operates pursuant to a renewable statutory charter (Export-Import Bank Act of 1945, as amended; 12 U.S.C. §635 et seq.), and also abides by international rules on ECA financing under the Organization for Economic Cooperation for Development (OECD). The Bank aims to provide support in two circumstances:

- to fill gaps in the market—when the private sector is unwilling or unable to provide financing for U.S. exports; or

- to counter foreign ECA competition—when U.S. exporters face competition from foreign businesses backed by foreign ECAs.

The activities of the Bank are "demand-driven," meaning they depend on private sector demand and interest for such government support. Ex-Im Bank charges interest, premia, and other fees for its services. Ex-Im Bank's rationales and activities are subject to legislative and policy debate.

In the 116th Congress, Senate confirmations to positions on the Board of Directors of the Bank restored a quorum of the Board and reinstated the Board's full authority, including to approve financing transactions above $10 million with repayment terms of seven years or longer, generally for the first time in nearly four years.

Ex-Im Bank's charter is scheduled to sunset on September 30, 2019, unless Congress takes action. Potential issues for the 116th Congress include whether to reauthorize Ex-Im Bank and, if so, under what terms, as well as Senate consideration of additional Board nominations and congressional consideration of reauthorizing Ex-Im Bank.

In deliberating on Ex-Im Bank's authorization status, potential options for Congress include a "clean" extension of Ex-Im Bank's sunset date (12 U.S.C. §635f), an extension with limited or significant changes to the charter, or other options, such as allowing the charter to lapse, terminating the Bank and setting specific parameters for a wind-down of Ex-Im Bank's functions, or reorganizing its functions in the context of overall U.S. export promotion and financing activities of the federal government.

Potential issues for Congress include:

- What should be the purpose of Ex-Im Bank? What are the economic, foreign competition, and other policy justifications for and against Ex-Im Bank?

- What length of time is desirable for an extension of Ex-Im Bank's charter?

- What should be Ex-Im Bank's exposure cap?

- Are modifications needed to the Board of Director terms, succession rules, or quorum?

- Should the scope of policy criteria for Ex-Im Bank be revisited?

- Should Ex-Im Bank programs, policies, and/or risk management practices be modified?

- Is Ex-Im Bank competitive with foreign ECAs? Do current international rules on export credit financing support U.S. policy goals, or are changes needed?

Introduction

The Export-Import Bank of the United States (Ex-Im Bank or the Bank)—commonly referred to as the official export credit agency (ECA) of the United States—provides financing and insurance to facilitate the export of U.S. goods and services to support U.S. jobs. Ex-Im Bank, a wholly owned U.S. government corporation, operates pursuant to a renewable, statutory charter (Export-Import Bank Act of 1945, as amended; 12 U.S.C. §635 et seq.), and also abides by international rules on ECA financing under the Organization for Economic Cooperation for Development (OECD). The Bank aims to provide support in two circumstances:

- to fill in gaps in the market—when the private sector is unwilling or unable to provide financing for U.S. exports; or

- to counter foreign ECA competition—when U.S. exporters face competition from foreign businesses backed by foreign ECAs.

The activities of the Bank are "demand-driven," meaning they depend on private sector demand and interest for such government support. Ex-Im Bank charges interest, premia, and other fees for its services. Ex-Im Bank's rationales and activities are subject to legislative and policy debate.

|

Ex-Im Bank: Key Dates July 1, 2015. The Bank's charter lapsed. July 20, 2015. Ex-Im Bank Board of Directors lost a quorum, rendering the Board unable to conduct policy, approve longer-term transactions above $10 million (with few exceptions), and do other business. December 4, 2015. Congress reauthorized Ex-Im Bank through September 30, 2019 (P.L. 114-94 ). May 8, 2019. Senate confirmations of Board members restored a quorum of the Board, and thus, restored Ex-Im Bank to full operational status. September 30, 2019. The Bank's charter is scheduled to lapse, unless Congress takes action. |

In the 116th Congress, Senate confirmations to positions on the Board of Directors of the Bank restored a quorum of the Board and reinstated the Board's full authority, including to approve financing transactions above $10 million with repayment terms of seven years or longer, generally for the first time in nearly four years (see text box).

Unless Congress takes action, Ex-Im Bank's charter is scheduled to sunset on September 30, 2019 and Ex-Im Bank will no longer have authority to authorize new transactions, but will be permitted to continue to serve its existing loan, guarantee, and insurance obligations and other functions "for purposes of an orderly liquidation."1

Potential issues for the 116th Congress include whether to reauthorize Ex-Im Bank and, if so, under what terms, as well as Senate consideration of additional Board nomination.

Select Developments on Reauthorization

In the 116th Congress, legislative and oversight developments include the following.

- The House Financial Services and Senate Banking Committee held hearings on reauthorization of the agency—on June 4, 2019 and June 27, 2019, respectively.

- H.R. 3407, the United States Export Finance Agency Act of 2019, was introduced on June 21, 2019 by House Financial Services Committee Chairwoman Waters and co-sponsored by Ranking Member McHenry. This bill would renew Ex-Im Bank's authority for seven years, raise its exposure cap to $175 billion by FY2026, and allow the Board of Directors to continue to operate and approve larger deals in the absence of a quorum through the creation of a temporary Board. The bill would also make a number of other changes to Ex-Im Bank's charter, including a controversial provision to restrict Ex-Im Bank's ability to finance and insure exports to Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The House Financial Services Committee scheduled a mark-up on June 26, 2019, but did not hold a vote due to opposition by some Members to some of the proposed changes in Chairwoman's bill. Some Members argued that proposed restrictions on Ex-Im Bank support for exports to Chinese SOEs would result in lost U.S. export opportunities and jobs, while others argued that they were important to address U.S. policy concerns with respect to China.

- S. 2293, the Export-Import Bank Reauthorization Act of 2019, which was introduced on July 25, 2019 by Senator Cramer, with nine original co-sponsors, would renew Ex-Im Bank for ten years, raise its statutory exposure cap to $175 billion, allow for the creation of a temporary Board of Directors to lead Ex-Im Bank if the Board of Directors loses a quorum of members necessary to approve larger deals. This bill has been referred to the Senate Banking Committee.

- H.R. 1910, the Export-Import Bank Termination Act, which was introduced on March 27, 2019 by Representative Amash, with five original co-sponsors, would terminate Ex-Im Bank. This bill has been referred to the House Financial Services Committee.

Background

Historical Overview

Ex-Im Bank's statutory basis is the Export-Import Bank Act of 1945, as amended, commonly referred to as the agency's "charter."2 The origins of Ex-Im Bank, however, date further back to two predecessor banks, established in 1934 as part of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Administration's New Deal response to the Great Depression.3 These origins are rooted in a combination of U.S. trade, economic, and foreign policy rationales.

In comparison to Ex-Im Bank's worldwide focus, the initial orientation of its predecessor banks was narrower; the Export-Import Bank of Washington ("first Bank") focused on supporting U.S. trade with the Soviet Union, while the Second Export-Import Bank of Washington (Second Bank) focused on supporting U.S. trade with Cuba. In both cases, the United States sought to stimulate U.S. international trade amid the Great Depression and to facilitate U.S. bilateral relations. The Second Bank's operations expanded to include supporting U.S. trade with all countries, save the Soviet Union. In 1936, the Second Bank's charter lapsed and its functions transferred to the first Bank. Congress extended the first Bank's charter several times, and in 1945, established the present-day Ex-Im Bank to supersede the first Bank—acting upon President Truman's proposal to use the first Bank to support post-war emergency reconstruction assistance in Europe.

In the immediate post-war period, Ex-Im Bank participated in reconstruction efforts through financial cooperation and physical rebuilding. Policymakers viewed Ex-Im Bank as a growing part of U.S. aid efforts. In the 1950s, Ex-Im Bank responded to requests from U.S. exporters by shifting away from aid-related activities to offering export credit financing for U.S. exports of goods and by confronting the competition that U.S. exporters faced in the form of officially-financed export credits. In the early 1960s, Ex-Im Bank further attempted to meet the needs of U.S. exporters by offering export credit guarantees to insure against political and exchange rate risk. In the 1970s, Ex-Im Bank funded large-scale infrastructure projects in numerous developing countries. By the early 1980s, small projects and capital goods and services constituted an increasingly larger share of Ex-Im Bank's business.4

Ex-Im Bank's name includes the word "import" and its formal statutory mission provides for facilitating both U.S. exports and imports.5 Historically, Ex-Im Bank's role in financing U.S. imports was negligible, as the financing of imports did not present the same challenges as financing U.S. exports linked to overseas credit.6 The agency does not support U.S. imports presently, focusing exclusively on support U.S. exports.

Authorization Status

Ex-Im Bank's full statutory authority is scheduled to sunset on September 30, 2019, unless Congress takes action. The primary method of continuing Ex-Im Bank's authority has been through the enactment of provisions extending the sunset date in the charter (12 U.S.C. §635f), most typically in authorizing laws (see Table 1). The average length of extension has been between four and five years.

Provisions in other laws, most typically appropriations acts, have also been used to provide for a continuation of functions during periods when the sunset date had lapsed and not yet been extended. The most recent extension of Ex-Im Bank authority through a provision in an appropriations act allowed Ex-Im Bank to exercise its functions for a little over eight months through June 30, 2015 (P.L. 114-164).

The agency's current authorization status follows years of active debate. After allowing Ex-Im Bank's full statutory authority to expire from July 1, 2015, until December 4, 2015, Congress reauthorized the agency through September 30, 2019 (P.L. 114-94). Congress also lowered Ex-Im Bank's portfolio "exposure cap" (total authorized outstanding and undisbursed financing and insurance) to $135 billion for FY2015-FY2019, subject to conditions, and made reforms in areas such as risk management, fraud controls, ethics, and the U.S. approach to international negotiations on ECA disciplines.

Board of Directors Leadership

By statute, a five-member Board of Directors, representing both political parties, leads the Bank. The Ex-Im Bank President and First Vice President serve as the Board Chairman and Vice Chairman, respectively. The Board needs a quorum (at least three members) to conduct business, including approving financing over $10 million with a repayment term of seven years or longer (with few exceptions), making policies, and delegating authority. The $10 million threshold is not a statutory parameter; rather, it arose through Board resolutions. Advisory and other committees provide support to the Board.

On May 8, 2019, the Senate confirmed three nominations to the Board: the President/Chairman, for a term expiring January 20, 2021 (79-17 vote); a member, for a term expiring January 20, 2023 (72-22); and another member, for a term expiring January 20, 2021 (77-19). The Senate action followed renewed calls by the Trump Administration for the Senate to restore the Bank to full capacity and subsequent cloture votes that limited debate. The nominations to the two other positions—one for First Vice President/Vice Chairman, for a term expiring January 20, 2021, and the other for a Board member, for a term expiring January 20, 2023—are available for action by the full Senate.

Previously, for nearly four years, starting on July 20, 2015, the Board lacked a quorum, as terms expired and no Board nominations were confirmed. No action was taken on Board nominations submitted during the 114th Congress. During the 115th Congress, some nominations were reported from committee, but none were confirmed.

With a restoration of a quorum, the Board of Directors has implemented outstanding requirements of the 2015 reauthorization act which required Board action. The Board appointed a chief ethics officer and a chief risk officer, raised the medium-term loan program cap from $10 million to $25 million, and increased staff authority to approve small business export financing from $10 million to $25 million. On July 30, 2019, the Board of Directors met for the first time since 2015 to consider transactions for approval.7

Ex-Im Bank in Context

Export financing and insurance are means of facilitating international trade to cover risks associated with the time between an export order being placed and payment being made. Exporters require due payment for goods and services, while importers need a guarantee they will be satisfied with delivery and status of purchased goods and services. Financing operations to bridge the time lag between product shipment and arrival by minimizing the risk of non-payment and other issues. There are many forms of trade finance, and usually, it is intermediaries such as banks or financing institutions that provide the financing.

Trade finance has been growing with international trade flows. No comprehensive source exists for measuring the magnitude and composition of the trade finance market globally, but general characterizations may be obtained by combining the statistics provided by certain national governments (whose coverage can vary) and other data sources.8 The global market for trade finance, when defined broadly, may be well above $12 trillion annual of $18 trillion of global exports.9 According to one industry report, about 80% of trade is financed by some form of credit, guarantee, or insurance.10 Globally, unmet demand for trade finance to support buyers and sellers of goods across countries could have been as high as $1.6 trillion in 2015—most related to proposals by smaller businesses and for transactions in low-income and emerging economies.11

Export financing is available through both the private sector and public sector. Commercial banks and insurance companies have been estimated to account for 80% of the trade finance market. Private lenders and insurers conduct the majority of short-term export financing, though ECAs may play a role in supporting certain sectors, such as taking on risks of financing small business exports. With respect to longer-term financing, the market can play an active role, but in certain cases, ECA support may help make transactions more commercially attractive by mitigating risks of financing or by providing an additional source of funding to diversify risks. Other sources of export financing are capital markets and manufacturer self-financing.

Ex-Im Bank is one of several federal government agencies involved in promoting U.S. exports of goods and services.12 It provides financing for U.S. exports of goods and services for companies of all sizes. Other U.S. government agencies also offer financing for exports, among other activities, including the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which finances U.S. agricultural exports, and the Small Business Administration (SBA), which provides export promotion-focused guarantee programs for small businesses.13 While Ex-Im Bank focuses on supporting exports in support of U.S. commercial interests, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) uses similar tools, but to support U.S. investment in developing and emerging economies to support U.S. foreign policy objectives.14 At the same time, Ex-Im Bank's activities can have U.S. foreign policy implications.

Requirements for Ex-Im Bank Financing and Insurance Support

Congress does not approve individual Ex-Im Bank transactions, and rather, has set statutory requirements for and prohibitions on the agency's activity in its charter and other laws. These statutory provisions serve as the basis of Ex-Im Bank policies and procedures.15

Ex-Im Bank's primary mission is to support U.S. exports of goods and services to support U.S. jobs.16 Under its charter, Ex-Im Bank-supported transactions must have a "reasonable assurance of repayment,"17 and Ex-Im Bank must charge fees and premiums "commensurate…with risks covered in connection with the contractual liability that the Bank incurs" for its support.18 The charter also directs Ex-Im Bank to provide exporters with financing terms and conditions that are "fully competitive" with those financing terms and conditions that foreign governments provide to their exporters.19 Under the charter, Ex-Im Bank financing must "supplement and encourage, and not compete with, private capital" (i.e., be "additional" to the private sector).20

What follows is an overview of select other provisions in Ex-Im Bank's statutory framework.21

Nonfinancial/Noncommercial Considerations. Ex-Im Bank is permitted to deny applications for credit on the basis of "nonfinancial and noncommercial considerations" only "in cases where the President, after consultation with the Committee on Financial Services of the House and the Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs of the Senate, determines" that the denial of such applications would be in the national interest in terms of advancing U.S. policy in areas such as international terrorism, nuclear proliferation, environmental protection, and human rights.22 The power to make a national interest determination has been delegated to the Secretary of State.

Economic Impact. Ex-Im Bank must determine whether the extension of its financing support would adversely affect the U.S. economy. 23 The charter also prohibits Ex-Im Bank from offering financial support for U.S. exports whose likely impact would prove negative on U.S. industries and employment.24 Ex-Im Bank has developed economic impact procedures and methodological guidelines to implement its statutory requirements and prohibitions.

Environment. Ex-Im Bank must consider the potential beneficial or adverse environmental effects of proposed transactions.25 The Board of Directors is authorized to grant or withhold financing support after taking into account the environmental impact of the proposed transaction.26 Ex-Im Bank has environmental and social due diligence procedures and guidelines.

- Coal. Ex-Im Bank environmental policies restrict support for coal-based power projects, but appropriations legislation prohibitions since FY2014 have resulted in Ex-Im Bank suspending these coal restrictions in lower-income countries—if doing so would prohibit Ex-Im Bank from supporting coal-fired or other power generation projects to provide affordable electricity in these countries.27

- Nuclear. Ex-Im Bank is prohibited from supporting "the purchase of any liquid metal fast breeder nuclear reactor or any nuclear fuel reprocessing facility."28 In most instances, the Board cannot give final approval for nuclear energy-related transactions unless Ex-Im Bank submits a detailed notification to Congress. For many years, appropriations laws have included a provision restricting the use of Ex-Im Bank program account funds for certain nuclear-related support.29

- Energy Source Nondiscrimination. Since 2015, Ex-Im Bank has been subject to a non-discrimination provision with respect to energy, prohibiting Ex-Im Bank from denying financing on the sole basis of industry, sector, or business, "for projects concerning the exploration, development, production, or export of energy sources and the generation or transmission of electrical power, or combined heat and power, regardless of the energy source involved."30

Content. In pursuit of its mandate to support U.S. jobs, Ex-Im Bank uses domestic "content"—the costs associated with the production of a U.S. export—as a proxy for U.S. jobs. Under its content policy, for all medium- and long-term transactions, Ex-Im Bank limits its support to the lesser of (1) 85% of the value of all goods and services contained within a U.S. supply contract; or (2) 100% of the U.S. content of an export contract. If the foreign content exceeds 15%, the Bank's support is lowered proportionally.31 For short-term export contracts, the minimum U.S. content for full Ex-Im Bank financing is generally 50%.32

Focus Areas. Congress directs Ex-Im Bank to support certain types of exports. Ex-Im Bank must make available not less than 25% of its total authority to finance small business exports, and to have a goal to increase the amount made available to finance exports by minority- and women-owned small businesses.33 The charter also directs Ex-Im Bank to promote renewable energy-related exports34 and exports to sub-Saharan Africa.35 While the Bank seeks to support these export goals, it is demand-driven and its activity depends on alignment with commercial opportunities.

Country, Sectoral, and Other Limitations. Congress prohibits Ex-Im Bank from supporting certain types of transactions subject to exceptions. Ex-Im Bank is prohibited from extending its support to countries that are in armed conflict with the United States,36 those subject to U.S. sanctions, those with balance of payment problems,37 those under the charter's "Marxist-Leninist" prohibition,38 or those for which a presidential determination has been issued.39 Ex-Im Bank also is prohibited from financing defense articles and defense services with certain limited exceptions, such as a national interest determination by the President.40

Notifications. Ex-Im Bank must submit proposed transactions of $100 million or more or transactions related to nuclear power and heavy water production facilities through a congressional notification process.41 Other notification and reporting requirements also apply.

- U.S. Flag Vessel. Under Ex-Im Bank's shipping policy, certain products supported by the Ex-Im Bank must be transported exclusively on U.S. vessels (e.g., generally direct loans of any amount, guarantees above $20 million, and products with repayment periods of more than seven years). Certain exceptions apply to this policy. This policy is based on Public Resolution 17 (PR-17, approved March 26, 1934, by the 73rd Congress).42

Financial Products

Ex-Im Bank provides direct loans, loan guarantees, and export credit insurance.43 Commitments and repayment periods can range from short-term (less than one year); to medium-term (one to seven years); to long-term (more than seven years). The Bank may determine repayment terms based on variables such as buyer, industry, and country conditions; common repayment terms that the market gives such products; terms of international rules on export credit activity; and the matching of terms offered by foreign ECAs. Ex-Im Bank, a demand-driven agency, charges interest, risk premia, and other fees for its services.

Direct Loans

Ex-Im Bank provides direct loans to foreign buyers of U.S. goods and services, usually for U.S. capital equipment and services (see Figure 1). Direct loans have no minimum or maximum size. The Bank extends to the U.S. company's foreign customer a loan covering 100% of U.S. content, up to 85% of the total contract amount. Direct loans are available for lengths up to 12 years generally and up to 18 years for renewable energy projects. The direct loans carry fixed interest rates and generally are made at terms that are the most attractive allowed under the provisions of the OECD Arrangement. The specific rates charged by Ex-Im Bank are based on the Commercial Interest Reference Rates (CIRR).44

|

|

Source: CRS, based on Ex-Im Bank information. Notes: This diagram is a general representation of Ex-Im Bank direct loans. Specifics vary by transaction. |

Prior to 1980, Ex-Im Bank's direct lending program was its chief financing vehicle. Both the budget authority requested by the Administration and the level approved by Congress for direct lending dropped sharply during the 1980s, reportedly as a target of budget cuts.45 In the past decade, demand for Ex-Im Bank direct loans has been limited due to low commercial interest rates.46 Demand for direct loans increased significantly with the international financial crisis of 2008-2009, as banking problems limited the ability of commercial banks to originate export finance transactions at competitive rates.

Medium- and Long-Term Loan Guarantees

Ex-Im Bank provides medium- and long-term guarantees of loans made by a lender to a foreign buyer of U.S. goods and services, promising to pay the lender, if the buyer defaults, the outstanding principal and accrued interest on the loan (see Figure 2).

|

|

Source: CRS, based on Ex-Im Bank information. Notes: This diagram is a general representation of Ex-Im Bank loan guarantees. Specifics vary by transaction. |

Loan guarantees are intended to cover repayment risk. Medium- and long-term loan guarantees are typically used to finance purchases of U.S. capital equipment and services. Unlike insurance (discussed below), loan guarantees are unconditional—representing Ex-Im Bank's commitment to a commercial bank for full repayment in the event of a default. The transaction size for a loan guarantee has no limit. Loan guarantees are up to 10 years generally, with exceptions up to 18 years for renewable energy projects. The guarantee covers 100% of the U.S. contact up to 85% of the total contract amount, with a minimum 15% down payment required from the buyer. The interest rate is negotiated between the commercial lender and the borrower.

Working Capital and Supply Chain Guarantee Programs

Ex-Im Bank also has specific loan guarantee programs for working capital guarantees and supply chain finance guarantees. These programs aim to make funds available for U.S. businesses to fulfill international sales orders.

The working capital guarantee program guarantees up to 90% of the principal and interest on a loan made to a participating lender for export-related inventory and accounts receivables. Ex-Im Bank's working capital program is intended to facilitate finance for businesses that have exporting potential but need working capital funds to produce or market their goods or services for export. A U.S. small business may have a cash flow shortage to fulfill an export order, and may seek a working capital loan to finance, for instance, its purchase of materials or supplies for the export order, the product of the good, or the collection of payment from the foreign buyer. However, the small business may face challenges obtaining this financing from the private sector, as the small business's inventory may not be a source of sufficient collateral for the loan and commercial banks are often unwilling to lend against export-related receivables. The Ex-Im Bank working capital guarantee may help the exporter expand its borrowing base by enabling the exporter to use these export-related assets as collateral for loans.

The supply chain finance guarantee program guarantees up to 90% to a participating lender that purchases accounts receivable from suppliers of an approved exporter. The program aims to allow U.S. suppliers to sell their accounts receivables to a private lender at a discounted rate to obtain early payment of their invoices and increase liquidity to fulfill export orders.

For both programs, the loan guarantee can be approved for a single loan or a revolving line of credit, and is a short-term guarantee of less than one year. Generally, each product must have more than 50% U.S. content based on all direct and indirect costs for eligibility. The interest rates for working capital loans guaranteed by Ex-Im Bank are set by the commercial lender.

Export Credit Insurance

Export credit insurance (see Figure 3) accounts for the majority of Ex-Im Bank's small business support, both by number and value of authorizations. Ex-Im Bank aims to support U.S. exporters by protecting their businesses against the risk of a foreign buyer (or other foreign debtor) defaulting on payment for political or commercial reasons.47 Export credit insurance could allow the exporter to extend more competitive terms of credit to foreign buyers, and/or allow the exporter to expand its borrowing base from a commercial lender, such as potentially by using Ex-Im Bank-insured receivables as additional collateral for financing.

Like loan guarantees, insurance is intended to reduce the risks involved in exporting by protecting against commercial or political uncertainty. However, in contrast, insurance is conditional on the fulfillment of various requirements for Ex-Im Bank to pay a claim (e.g., compliance with underwriting policies, deadlines for filing claims, payment of premiums and fees, and submission of proper documentation).48

For a qualified transaction, the small business may receive export credit insurance from Ex-Im Bank to cover 95% of the political and commercial losses of exporting. Export credit insurance can cover single buyers or multiple buyers in multiple countries. Ex-Im Bank charges insurance premia and other fees.

The Bank issues short-term insurance policies of less than one year to U.S. exporters to reduce their risk of nonpayment by the foreign buyer. Coverage is generally up to 95% of nonpayment losses due to commercial and political risks. Short-term exporter insurance is available for products shipped from the United States and with at least 50% U.S. content (excluding mark-up). Ex-Im Bank offers a renewable one-year policy that generally covers up to 180-day terms, but can be extended up to 360 days for qualifying transactions. Ex-Im Bank also maintains short-term insurance policies for lenders.

Ex-Im Bank can extend medium-term insurance policies generally for one to seven years and for amounts up to $25 million, to both exporters and lenders, covering one or a series of shipments. Coverage is for 100% of the U.S. content, up to 85% of the contract price. Ex-Im Bank requires the buyer to make cash payment to the exporter equal to 15% of the U.S. contract value.

|

|

Source: CRS, based on Ex-Im Bank information. Notes: This diagram is a general representation of Ex-Im Bank exporter insurance. Specifics vary by transaction. |

Specialized Finance Products

Ex-Im Bank's programs include specialized finance products,49 such as:

- project finance, which is limited recourse finance to newly created companies, usually in amounts greater than $10 million. Project finance typically covers large, long-term infrastructure and industrial projects (e.g., airport construction, oil and gas power sector projects, wind turbines), involving multiple contracts for completion and operation. Sponsor support during construction, combined with the project's future cash flows, form the basis for the Bank's analysis of the creditworthiness of the project, as well as its source of repayment (rather than repayments by foreign governments, financial institutions, or established corporations). Repayment terms are generally up to 14 years, but can be up to 18 years for renewable energy projects.

- structured finance, which is finance to existing companies located overseas, based on their balance sheets and other sources of collateral or security enhancements. Through structured finance, Ex-Im Bank has financed fiber-optic cable, oil and gas projects, air traffic control systems, satellites, and manufacturing equipment. Repayment terms generally are for up to 10 years, but can be up to 12 years for power transactions.

- transportation finance, including for aircraft, ship, and railroad exports, based on the guidelines set by sectoral understandings under the OECD Arrangement.

Activity and Portfolio Exposure

In FY2018, Ex-Im Bank authorized $3.3 billion for 2,389 transactions (see Figure 4), to support an estimated $6.8 billion in U.S. exports and 33,000 U.S. jobs. About $40 billion in transactions were pending Board consideration in FY2018. In FY2014, when fully operational, the Bank authorized $20.5 billion for 3,746 transactions, to support an estimated $27.5 billion in U.S. exports and more than 164,000 U.S. jobs. As in prior years, in FY2018, U.S. small businesses accounted for most authorizations by number (91%). At the same time, U.S. small businesses accounted for a growing share of authorizations by dollar amount—66% in FY2018, up from 25% in FY2014.

|

|

Source: CRS, based on data from Ex-Im Bank annual reports. |

Ex-Im Bank has a statutory limit on the aggregate amount of loans, guarantees, and insurance that it can have outstanding at any one time.50 The outstanding principal amount of all loans made, guarantees, or insured by the Bank is charged at the full value against the limitation. In FY2018, Ex-Im Bank's exposure was $61 billion—less than half of its statutory exposure cap of $135 billion that year (see Figure 5). Following record highs in exposure levels associated with increased demand for Ex-Im Bank services during the financial crisis, the Bank's exposure level has declined in recent years while the agency was not fully operational and repayments on outstanding transactions exceeded new activity. Ex-Im Bank examines its concentration by program, region, sector, and other measures (see Figure 6) as part of risk management.

|

Figure 5. Ex-Im Bank Exposure Levels and Exposure Cap, FY1997-FY2018 |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis of data from Ex-Im Bank annual reports. |

Appropriations and Budget

As with other federal credit programs, beginning with FY1992, Ex-Im Bank's activities have been subject to the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (FCRA, P.L. 101-508), which aimed to measure more accurately the cost of federal credit programs and to make the cost of such credit programs more comparable to direct federal outlays for budgetary purposes. For a given fiscal year, under FCRA, the cost of federal credit activities, including those of Ex-Im Bank, is reported on an accrual basis equivalent with other federal spending, rather than on a cash flow basis, as used previously. Under FCRA, credit subsidy estimates are calculated by discounting them using the rates on U.S. Treasury securities with similar terms to maturity—which traditionally have been considered to be risk-free—and are below the rates of commercial loans.51

Between 1992 and 2008, the Bank received direct appropriations for its administrative expenses and FCRA credit subsidy for those years in which the subsidy was estimated to be positive. Since 2008, Congress and the President gave the Bank permission to use its offsetting collections (e.g., interest, premia, and other fees charged for activities) to fund its administrative and program expenses and to retain a limited amount of any excess collections ("carryover funds") for a certain amount of time. The appropriations language provides that the receipts collected by Ex-Im Bank are credited as offsetting collections in the federal budget and are intended to cover the cost of the Bank's operations. Therefore, the offsetting collections are intended to reduce the appropriations from the General Fund to $0.

At the start of the fiscal year, the U.S. Treasury provides Ex-Im Bank with an "appropriation warrant" for operating costs and administrative expenses. The amount of the warrant is established by the spending limits set by Congress and agreed to by the President in the appropriations process. According to Ex-Im Bank, it uses these offsetting collections to repay the warrant. Thus, Ex-Im Bank initially receives funds from the U.S. Treasury and subsequently repays those funds as offsetting collections come in.

As part of the annual appropriations process, Congress provides a direct appropriation for Ex-Im Bank's Office of Inspector General (OIG) and sets an upper limit on the amount available to the Bank for administrative expenses to carry out its direct loan, loan guarantee, and export credit insurance programs. For FY2019, the President's budget requested $4.8 million in funding for the OIG, a limit of $90.0 million for administration expenses, a cancellation of $10 million carryover funds from prior appropriations, and a cancellation of $13.4 million in the Tied Aid Credit Fund.52 Compared to the President's budget request, congressionally appropriated amounts for FY2019 were $5.7 million for the OIG and $110.0 million for administrative expenses; Congress did not provide any carryover authority for the Bank and rejected the request to cancel tied aid funds. The President's FY2020 budget requests $5 million for the OIG, a limit of $95.5 million for administrative expenses, and a $106 million cancellation in unobligated funds for tied aid (see Table 2).

Ex-Im Bank's revenues include interest, risk premia, and other fees that it charges for its support. Revenues acquired in excess of forecasted losses are recorded as offsetting collections. According to the Bank, since 2000, it has contributed to the Treasury $14.8 billion after covering its administrative and program costs, and other expenses. (This is on a cash basis, and different from the amount calculated on a budgetary basis.53) In FY2017 and FY2018, Ex-Im Bank did not report any contributions to the Treasury. In comparison, Ex-Im Bank contributed to the Treasury $674.7 million in FY2014, $431.6 million in FY2015, and $283.9 million in FY2016. Compared to administration expenses, the portfolio of the agency shrank and its offsetting collections declined with the prior temporary lapse of the charter and loss of a quorum constraining Ex-Im Bank's authority to approve deals.

In addition, borrowings from the U.S. Treasury are used to finance medium- and long-term loans, and carry a fixed interest rate. Ex-Im Bank repays these borrowings primarily as repayments are received from recipients of its medium- and long-term loans.54

|

Category |

FY2014 |

FY2015 |

FY2016 |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

FY2020a |

|

Inspector General Amount |

5.1 |

5.8 |

6.0 |

5.7 |

5.7 |

5.7 |

5.0 |

|

Total Credit Subsidyb |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Total Administrative Budget |

115.5 |

106.3 |

106.3 |

110.0 |

110.0 |

110.0 |

95.5 |

|

Carryover amount |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

Tied aid amount cancelled |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

106.0 |

Source: Office of Management and Budget (OMB), Budget of the United States Government, various years; appropriations legislation, various years; and Ex-Im Bank documents. Differences in amounts requested and appropriated may vary due to different assumptions used in estimating credit subsidies by OMB and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

Note: (a) Requested. (b) Credit subsidy refers to program activities (the cost of direct loans, loan guarantees, insurance, and tied aid) conducted by Ex-Im Bank, as estimated for budgetary purposes under the Federal Credit Reform Act (FCRA). Subsidy costs are subject to reestimates.

Risk Management

Ex-Im Bank seeks to manage the risks it faces in its transactions (see Table 3). The charter requires a "reasonable assurance of repayment" for transactions supported by the Bank55 and for the Bank to have "reasonable provision for possible losses,"56 among other provisions. The Bank has a system in place to mitigate risks through credit underwriting and due diligence of potential transactions, as well as monitoring risks of current transactions. If a transaction has credit weaknesses, the Bank aims to try to restructure it to help prevent defaults and increase the likelihood of higher recoveries if the transaction does default. Ex-Im Bank also has a claims and recovery process for transactions in default. The effectiveness of Ex-Im Bank's risk management has been subject to congressional debate.

Based on its charter, Ex-Im Bank assesses and monitors credit and other risks of transactions, maintains reserves against losses, and provides a quarterly report on its default to Congress.57 It reported a default rate of 0.518% as of March 2019 (sent quarterly to Congress). In recent quarters, Ex-Im Bank's default rate has trended slightly upward, but is considered to be well-below that of commercial bank default rates.

In FY2018, Ex-Im Bank's reserves and allowances for total losses were $3.7 billion (6.4% of total outstanding balance). Since 1992, Ex-Im Bank has been able to recover 50 cents on the dollar on average for transactions in default. Backed by the U.S. government, Ex-Im Bank can take legal action against obligors for transactions in default. It is also able to recover assets because its loans are heavily collateralized, as a high percentage of its transactions are asset-backed (e.g., aircraft).

|

Risk |

Definition |

|

Repayment |

The risk that a borrower will not pay according to the original agreement and the Bank may eventually have to write-off some or all of the obligation because of credit or political reasons. |

|

Concentration |

Risk stemming from the composition of the credit portfolio as opposed to the risks related to specific obligors. Ex-Im Bank faces concentration risks in terms of the composition of its portfolio by geographic region, industry, and obligor. |

|

Foreign Currency |

Risk stemming from an appreciation or depreciation in the value of a foreign currency in relation to the U.S. dollar in Ex-Im Bank transactions denominated in that foreign currency. |

|

Operational |

The risk of material losses due to human error, system deficiencies, and control weaknesses. |

|

Interest Rate |

Ex-Im Bank makes fixed-rate loan commitments prior to borrowing to fund loans and takes on the risk of borrowing funds at an interest rate greater than the rate charged on the credit. |

International Context

The United States historically has been a leader in international efforts to develop rules within the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) on ECA financing. In the 1960s and 1970s, many ECAs offered financing at interest rates below market rates, raising concerns and market distortions and inefficiency and a "race to the bottom." The OECD Arrangement on Officially Supported Export Credits (the "Arrangement") arose out of U.S. and other major developed countries' efforts to create "rules of the road" to address such concerns.

Entering into effect in 1978, the Arrangement aims to ensure a level playing field for ECA activity such that the price and quality of exports, not their financing terms, guide purchasing decisions. The Arrangement, which applies to ECA financing with repayment terms of two years or more (medium-and long-term, or MLT, financing) sets minimum interest rates, maximum repayment terms, and other terms and conditions, including on tied aid and transparency, as well as certain sector-specific rules. The rules have been understood to govern "tied financing," that is, financing linked to the procurement of national goods and services. The Arrangement is a "non-binding" agreement but historically has generated compliance. Export credit financing that is covered by the OECD Arrangement generally is exempt from the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM), which disciplines the use of export subsidies and the actions countries can take to counter the effects of these subsidies. The SCM Agreement is interpreted to indicate that, for non-agricultural products, an export credit practice in conformity with the OECD Arrangement on export credits shall not be considered as an export subsidy prohibited by the SCM Agreement.58

Participants to the Arrangement are the United States, Australia, Canada, the European Union, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Norway, and Turkey—all OECD members. Brazil, which is not an OECD member, is participant of the aircraft sector understanding to the Arrangement.59

Presently, 112 ECAs or other official entities provide some form of export credit support globally.60 The size of ECA programs vary. In 2018, China's MLT export financing was estimated to be $39 billion—larger than that of the next three ECAs combined (Italy, Germany, and South Korea); in comparison, in 2018, Ex-Im Bank's MLT support was $300 million (see Figure 7).61

|

|

Source: CRS, based on Ex-Im Bank 2018 Competitiveness Report data. |

Over time, ECA financing that is outside of the scope of the OECD Arrangement has grown. One driver of this trend is that China and other non-OECD countries increasingly are active in operating ECAs; as non-OECD members, they do not necessarily abide by the rules of the Arrangement. China, in particular, poses the most extensive challenges for U.S. exporters. Over ten years, the level of Chinese ECA activity has grown from being one-tenth of that of the United States and other G-7 countries combined to roughly equal. In addition to the sheer magnitude of its financing, the characteristics of China's ECA financing—such as its opacity and flexibility to provide concessional loans—raise particular concern. Such concerns have intensified with Chinese initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative and China Made in 2025. Another driver of the growth of ECA financing outside of the OECD Arrangement's scope is that many OECD members are providing such financing. For example, through "market windows," ECAs offer pricing competitive with the commercial market; since market window transactions are not covered by the Arrangement, ECAs have more flexibility on terms and conditions for financing through them. Ex-Im Bank says it is the only ECA among major developed countries that fully abides by the Arrangement.

The international export finance landscape is undergoing other transformations as well. Many countries rely on exports for a more significant share of their economic growth than the United States, and historically they have placed greater emphasis on export promotion and financing at the highest levels as part of their national strategies.62 Many countries also view export financing and promotion as a way to support strategically important industries and protect "national champions" from foreign competition, such as energy, technology, and defense industries.

Market changes also have influenced the ECA landscape. Commercial banks are experiencing regulatory constraints on their international lending. Regulations imposed after the global financial crisis (more stringent capital and liquidity requirements) have incentivized commercial banks to accept less commercial risk. This has particularly affected the supply of MLT export financing for higher-risk, large-volume, and/or longer-tenor credits from commercial sources. The number of "mega-deals" greater than $1 billion also has grown significantly.

As such, the fundamental nature of ECAs is evolving. Historically, ECAs have operated as reactive "lenders-of-last-resort," and now, they are increasingly operating proactively. Many ECAs have boosted their export financing programs, introduced or expanded use of unregulated trade-related financing programs (including both united and investment financing), and increased the number and flexibility of programs and institutions. One example is new programs to encourage U.S. exporters to shift parts of their supply chain overseas; these programs guarantee access to high volumes of attractive financing that are not related to any specific project or transaction. Another example is increasing flexibility of "content" policies, including to decrease the level of domestic content required to obtain the maximum level of official ECA support (ranging from not requiring any in-country production to 30% domestic content), focusing more on "national interest" or "national benefit requirements," broadening the definition of domestic content to include factors such as research and development expenses, and permitting more exceptions to their content policies for transactions that meet other aims (such as ECA support to help companies shift part of their supply chains to those countries).63

These changes have called some policymakers and stakeholders to question the ongoing relevance of the OECD Arrangement. There have been calls to try to bring non-OECD countries such as China under the tent. As another approach, since 2012, an International Working Group (IWG), composed of the United States, China, and other countries, has been negotiating separate export credit disciplines. The IWG has taken a sectoral focus, and progress reportedly has been limited. China, India, Brazil, and other countries reportedly have expressed little interest in the negotiations, particularly while Ex-Im Bank was not fully authorized or operational.64

Debate Over Ex-Im Bank

Potential congressional consideration of Ex-Im Bank's reauthorization, and Senate consideration of additional nominations to the Board, may raise economic and other policy issues for Congress.

Economic Issues

Much of the economic debate centers on what role Ex-Im Bank plays relative to private financial markets, and whether such government intervention can produce net benefits to the U.S. economy.65 Economic theory predicts that government programs like Ex-Im Bank shift production among sectors within the economy by altering the allocation of capital and labor resources in the economy, and while they may increase exports of certain firms, they do not affect the overall level of exports and employment in the long-run. Rather, the main factors affecting the overall level of a country's exports are economic policies that determine interest rates, capital flows, and exchange rates. While most economists generally favor allowing the market to determine the allocation of resources, government intervention may be viewed as warranted in some instances to correct market limitations or failures.

Supporters assert that Ex-Im Bank supports U.S. jobs through facilitating viable exports that private financial institutions are unwilling or unable to support due to market limitations (such as domestic lending rules, bank-specific constraints, or lack of specialized knowledge of certain geographic regions or economic sectors) and market failures (such as times of financial crisis); these constraints lead commercial banks to charge unfeasible interest rates and other terms for a proposed transaction or to avoid the transaction altogether.66 Opponents question the market failure rationale, taking issue with the U.S. government assuming risks that the private sector deems prudent to avoid. They argue that Ex-Im Bank crowds out private sector activity and distorts the market by changing the allocation of resources among sectors, reducing economic efficiencies.67 Critics charge that Ex-Im Bank picks winners and losers; proponent counter that Ex-Im Bank subjects all transactions to statutory and policy requirements.

In highlighting Ex-Im Bank's "additional" role, supporters often focus on two areas where government-backed financing may play a more significant role. They argue that Ex-Im Bank helps small business exporters directly that face limited credit options because private lenders do not accept export receivables (unlike domestic receivables) as collateral for lending, as well as help the small businesses in the supply chains of larger exporters that are direct users of Ex-Im Bank. Supporters also underscore Ex-Im Bank's role in supporting capital goods exports and exports for large-scale, multi-year infrastructure projects. Commercial banks may lack the specialized information to accurately gauge risk in particular economies and sectors, or may be unwilling to assume longer-term risks or to be involved in regions or countries that they see as high-risk. Critics view Ex-Im Bank as "corporate welfare," as the majority of its transactions historically have been larger businesses by value. Critics also question Ex-Im Bank's actual benefit to small businesses and the agency's definition of small businesses.

In policy debates, a data point that often arises is that Ex-Im Bank activity supports a small share of U.S. exports (around 2%). Supporters argue that this small share means that Ex-Im Bank limits its activities to filling market gaps and is not market-distorting.68 Critics question Ex-Im Bank's significance if the vast majority of exports can go forward without its support, and they argue that the agency imposes more costs than benefits. As discussed earlier, Ex-Im Bank's activities are demand-driven, and they can vary depending on the overall level of activity in the global economy. The prior, more-limited operations of the Bank for nearly four years also may affect the policy debate; supporters argue that the lack of a quorum cost U.S. exports and jobs for direct Ex-Im Bank users and their supply chains. Critics dispute notions of economic loss, holding that private-sector financing was strong for historically major Bank users, such as Boeing.

The issue of whether Ex-Im Bank is a "subsidy" also often arises in economic debates. Supporters point out that Ex-Im Bank financing, as it is within the scope of the OECD Arrangement, is not a "subsidy" under international WTO subsidy rules, and that Ex-Im Bank, by statute, conducts economic impact analyses to measure the economic effects of transactions. Critics charge Ex-Im Bank with "subsidizing" exports purchased by foreign buyers since the terms may be more favorable than what the market charges. Supporters counter that Ex-Im Bank charges interest, premia, and other fees for its services. Critics argue that Ex-Im Bank's analyses do not take into account the full downstream effect. Some supporters also acknowledge that improvements to how Ex-Im Bank measures economic impact may be warranted.

International Competition Issues

Another aspect to the debate is the existence of foreign countries' export financing programs. Many countries have programs that are substantially larger than those of Ex-Im Bank (see Figure 7 above). Supporters of Ex-Im Bank assert that its services are critical to offset the effects of similar programs used by foreign governments and to boost U.S. exporters' competitiveness. Some supporters hold that even if critics' economic arguments have some basis, the foreign competition argument in favor of Ex-Im Bank prevails.69 Supporters further note that for some industries and projects (e.g., nuclear sector, infrastructure), foreign buyers frequently require or expect bidders to bring offers of government-backed export financing alongside their proposal as a prerequisite for being considered in the bid.70 Ex-Im Bank guarantees also may be important for some firms involved in long-term projects in which the implied backing of the U.S. government is needed, for instance, for transactions in countries where there may be political or economic instability and the threat of foreign government intervention may be possible.

Critics question whether the export promotion programs of other countries have a negative effect on U.S. exports. They note that some economists contend that the export promotion programs of other countries are likely to have little effect on the overall level of U.S. exports, although certain foreign government export policies may have harmed certain U.S. industries. Critics also argue that the U.S. policy focus should be on negotiating to further reduce and eliminate ECA financing internationally, and strengthening international rules and disciplines on ECA financing—particularly to make China and other countries that are not a part of the OECD Arrangement more accountable. Supporters may agree with critics on negotiating stronger ECA disciplines, but they counter that "unilateral disarmament" by abandoning Ex-Im Bank would diminish U.S. negotiating leverage, and they are skeptical that other countries would eliminate their ECA programs, given the central role of exports in many of their economies.

The debate over foreign competition increasingly has centered on China, which, as noted above, had MLT financing of nearly $40 billion in 2018—far surpassing that of other ECAs. Proponents hold that, while Ex-Im Bank does not favor one industry over another (rather, subjecting all transactions to the same statutory and policy requirements), Ex-Im Bank financing can support U.S. firms' competitiveness in strategic sectors, particularly vis-à-vis China. Critics oppose Ex-Im Bank support for U.S. exports to Chinese and other state-owned enterprises. They also question how "subsidizing" U.S. exports to China advances the Trump Administration's trade policy goals regarding China.71 Some supporters counter that without Ex-Im Bank, those exports may go to other countries. Some believe that the agency's activities with respect to Chinese SOEs should be restricted for broader trade and foreign policy reasons.

Potential Issues for Congress

Congress could take a range of approaches related to Ex-Im Bank's authority. One option is a "clean" renewal, which would extend the sunset date in the charter. Options to renew Ex-Im Bank's charter also could include limited changes (such as revising the agency's exposure cap) or more substantive "reforms" (such as also making modifications to Ex-Im Bank's scope, structure, conditions, risk management practices, and/or reporting requirements). A range of reasons may motivate "reforms," including enhancing Ex-Im Bank's ability to fill in gaps in private sector financing and offset competition from foreign ECAs; limiting the agency's size and scope and exposure to U.S. taxpayers; and furthering efforts to eliminate all ECA activity internationally. Proposed reforms may raise, among other things, issues regarding balancing Ex-Im Bank's core mission to boost U.S. exports and jobs with other policy goals. Other options include allowing a sunset in Ex-Im Bank's authority, such as by taking no legislative action, or passing legislation setting specific parameters for a wind-down in Ex-Im Bank's functions; the sunset provision in Ex-Im Bank's charter (12 U.S.C. 635f) would set in motion an "orderly liquidation" of Ex-Im Bank's assets, the details of which Congress may consider how to flesh out. Still other options include reorganization of Ex-Im Bank's functions; the existence of a range of federal government agencies that focus on export promotion has prompted debate about whether any overlap in functions constitutes duplication or the use of the same or similar tools to meet different goals.

If pursuing reauthorization, questions that Members may consider include the following.

What should be the purpose of Ex-Im Bank? Congress may revisit Ex-Im Bank's policy role. Historically, the role of ECAs has been to operate as a "lender of last resort." While Ex-Im Bank still subscribes to this model, many other ECAs are increasingly driven by strategic and foreign policy reasons. Ex-Im Bank activity can have strategic and foreign policy impacts, but when Ex-Im Bank is making decisions on what projects to support, it is looking at whether the project meets statutory and policy terms and conditions. In only limited circumstances can Ex-Im Bank make determinations based on noncommercial or nonfinancial reasons. A major point of debate over H.R. 3407 was its restriction on Ex-Im Bank activity with respect to Chinese SOEs.

What length of time is desirable for an extension of Ex-Im Bank's sunset date? Shorter extensions arguably have given Congress the opportunity to weigh in on Ex-Im Bank operations on a more frequent basis through the lawmaking process. On the other hand, Ex-Im Bank and certain stakeholders have asserted that longer-term extensions can enhance U.S. exporters' strategic planning and commercial certainty on the availability of Ex-Im Bank support without disruptions. During reauthorization hearings in the 116th Congress, U.S. businesses advocated for a longer reauthorization period of seven to ten years. H.R. 3407 would provide a seven-year extension of Ex-Im Bank's authority, and S. 2293 would provide a ten-year extension.

What should be Ex-Im Bank's exposure cap? Many past reauthorizations modified Ex-Im Bank's exposure cap. Debate over exposure cap can intersect with broader debates about the appropriate size and scope of the federal government. Supporters generally advocate for expanding Ex-Im Bank's exposure cap. Critics may favor reducing the cap to target Ex-Im Bank's activities, for instance, to supporting small businesses and limiting taxpayer risk. H.R. 3407 and S. 2293 would incrementally raise the exposure cap to $175 billion from the current $135 billion.

Are modifications needed to the Board of Director terms, succession rules, or quorum? For many supporters, the inability of Ex-Im Bank to operate at full capacity for nearly four years due to a lack of quorum of the Board underscored a need to change the current statutory framework for Board operations. Past proposals in appropriations would have relaxed the quorum requirement, while H.R. 3407 and S. 2293 would establish alternative procedures to ensure that Ex-Im Bank is able to continue operations in the event of a future quorum lapse by creating a temporary Board led by the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR). Some have also suggested considering allowing ex officio Board members to vote.

Should the scope of policy criteria for Ex-Im Bank be revisited? Some policymakers have expressed concern that Ex-Im Bank historically has had difficulty meeting its small business target by dollar amount, while others seek to raise the target. Responding to these issues, some emphasize Ex-Im Bank's demand-driven nature. Some Members and civil society groups also have expressed environmental concerns about Ex-Im Bank financing fossil fuel projects and aim to strengthen environmental assessments conducted by the Bank. Other Members and some industry groups favor maintaining the current statutory framework, which includes a requirement for Ex-Im Bank to not discriminate against transactions based on energy source.

Should Ex-Im Bank programs, policies, and/or risk management practices be modified? Supporters argue that Ex-Im Bank operates well overall, and some acknowledge that certain elements could be improved potentially through administrative action, such as further streamlining of operations for small business transactions and improving small business outreach. Critics argue that shortfalls remain in the charter. Areas of debate may include additionality; Ex-Im Bank requires applicants to explain the reason for seeking support (market-based or foreign competition reasons), and the Ex-Im Bank OIG has made recommendations for greater documentation of additionality determinations and evaluation of procedures, to which Ex-Im Bank management concurred.72 H.R. 3407 would impose further additionality documentation and reporting requirements. Some voice concern that such requirements could be overly burdensome for the agency and its users alike. Another area of debate could be risk management. Supporters highlight Ex-Im Bank's low default rate, high recovery rate, reserves, and implementation of reforms pursuant to the 2015 reauthorization act as demonstration of the agency's effective risk management.73 Critics express concern about taxpayer risk, and favor more transparency and accountability, as well as potentially imposing concentration limits on Ex-Im Bank's portfolio.74 Differing views exist on Ex-Im Bank's budgetary impact, with estimates varying based on "federal credit" and "fair value" methods of accounting.75

Is Ex-Im Bank competitive with foreign ECAs? Members may consider whether to press the Administration to modify the U.S. export financing approach to be more competitive with countries operating outside of the scope of the OECD rules, such as through greater use of the tied aid war chest or new flexibilities in policy areas identified by stakeholders in the annual competitiveness report (e.g., Ex-Im Bank's content policy, defense/nuclear prohibition, and U.S. flag shipping requirement). Members could also call for greater emphasis on "leveling the playing field"; they may examine the OECD Arrangement, as well as the status of negotiations under the International Working Group, to see if they comport with U.S. policy objectives and interests. They could direct the Administration to work more intensively to eliminate ECA financing, and/or to pursue ongoing international negotiations on new export credit rules more intensively to impose disciplines on Chinese and other non-OECD ECA activity. Another avenue could be considering ECA rules as part of a potential reform of the WTO.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

Amber Wilhelm, a Visual Information Specialist, and Jennifer Roscoe, a Research Assistant, provided assistance on visuals.

Footnotes

| 1. |

12 U.S.C. §635f. See Ex-Im Bank Office of Inspector General (OIG), Report on EXIM Bank's Activities in Preparation for and During its Lapse in Authorization, March 30, 2017, OIG-EV-17-02. |

| 2. |

P.L. 79-173; 59 Stat. 526. See also National Archives, "Records of the Export-Import Bank of the United States," http://www.archives.gov/research/guide-fed-records/groups/275.html. |

| 3. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Banking and Currency, Legislative History of the Export-Import Bank of Washington, committee print, 83rd Cong., 1st sess., 1953, p. 2. |

| 4. |

Jordan Jay Hillman, The Export-Import Bank at Work: Promotional Financing in the Public Sector (Westport 1982); and Ex-Im Bank, "80th Anniversary" history webpages, http://archive.exim.gov/about/whoweare/anniversary/History/1930s.cfm. |

| 5. |

12 U.S.C. §635(a). |

| 6. |

See excerpt from Jordan Jay Hillman, The Export-Import Bank at Work, Westport: Quorum Books, 1982, pp. 31-32: The era [1945 - 1953] cannot be brought to its conclusion without mention of imports—in name and formal statutory status constituting one-half of [Ex-Im Bank's] mission. Moreover, if trade-oriented exports were ever to be supported, this was the time. It was, after all, an era when a dominant goal of foreign lending programs was to increase the dollar earning capacity of recipient countries. Nevertheless, even in this period when imports were seen as a positive factor in reducing an excessive U.S. trade surplus, [Ex-Im Bank's] role in financing import trade, as such, was negligible. In general, the Bank considered commercial bank credits adequate for transactions at risk levels that the Bank itself was otherwise likely to undertake. Import trade, of course, involved the financing of U.S. domestic buyers. They presented neither the credit information nor security enforcement problems associated at the time with overseas credit. It thus remained the view of the Bank that efforts to aid and facilitate foreign sales in the United States were best directed to increasing the productive capabilities of foreign countries. Import trade transactions financed by [Ex-Im Bank] were, and were to remain, negligible. |

| 7. |

Ex-Im Bank, "EXIM Board of Directors Approves Preliminary Commitments for U.S. Exports to Projects in Cameroon and Iraq," press release, July 31, 2019. |

| 8. |

Bank for International Settlements (BIS), Committee on the Global Financial System (CGFS), Trade Finance: Developments and Issues, CGFS Papers No. 50 by Clark J. Basel, January 2014, https://www.bis.org/publ/cgfs50.pdf. |

| 9. |

World Trade Organization (WTO), Trade Finance and SMEs: Bridging the Gaps in Provision (interpreting the BIS 2014 report). |

| 10. |

International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), 2018 Global Trade – Securing Future Growth: ICC Global Survey on Trade Finance. |

| 11. |

Alisa DiCaprio et al., 2016 Trade Finance Gaps, Growth, and Jobs Survey, Asian Development Bank (ADB), August 2016. |

| 12. |

See CRS In Focus IF11016, U.S. Trade Policy Functions: Who Does What?, by Shayerah Ilias Akhtar. |

| 13. |

See CRS Report R44985, USDA Export Market Development and Export Credit Programs: Selected Issues, by Renée Johnson; and CRS Report R43155, Small Business Administration Trade and Export Promotion Programs, by Sean Lowry. |

| 14. |

CRS In Focus IF10659, Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC), by Shayerah Ilias Akhtar. The new International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) is to succeed OPIC as the U.S. government's development finance institution. See CRS Report R45461, BUILD Act: Frequently Asked Questions About the New U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, by Shayerah Ilias Akhtar and Marian L. Lawson. |

| 15. | |

| 16. |

12 U.S.C. §635(a)(1). |

| 17. |

12 U.S.C. §635(b)(1)(B). |

| 18. |

12 U.S.C. §635(c)(1). |

| 19. |

12 U.S.C. §635(b)(1)(A) ("fully competitive with the Government-supported rates and terms and other conditions available for the financing of exports of goods and services from the principal countries whose exporters compete with [U.S.] exporters, including countries the governments of which are not members of the [OECD] Arrangement") and 12 U.S.C. §635(b)(1)(B) ("fully competitive with exports of other countries and consistent with international agreements"). |

| 20. |

12 U.S.C. §635(b)(1)(B). |

| 21. |

Refer to Ex-Im Bank's charter (12 U.S.C. §635 et seq.) for full treatment. |

| 22. |

12 U.S.C. §635(b)(1)(B). |

| 23. |

The Bank is required to have "regulations and procedures ... to insure that full consideration is given to the extent that any loan or guarantee is likely to have an adverse effect on industries ... and employment in the United States... " (12 U.S.C. §635a-2). These regulations and procedures are in support of the congressional policy that in authorizing any loan or guarantee the Board of Directors shall take into account any serious adverse effect of such loan or guarantee (12 U.S.C. §635(b)(1)(B)). |

| 24. |

Ex-Im Bank is prohibited from extending any loan or guarantee "for establishing or expanding production of any commodity for export by any other country" if "the commodity is likely to be in surplus on world markets at the time the resulting commodity will first be sold" or "the resulting production capacity is expected to compete with [U.S.] production of the same, similar, or competing commodity" and "may cause substantial injury to [U.S.] producers of the same, or a similar commodity" (12 U.S.C. §635(e)(1)). The Bank also is prohibited from providing any loan or guarantee for the resulting production of substantially the same product that is subject to U.S. trade measures, such as anti-dumping or countervailing duties (12 U.S.C. §635(e)(2)). These prohibitions shall not apply if the Board of Directors determines that the proposed transaction's "short- and long-term benefits to industry and employment in the United States are likely to outweigh the short- and long-term injury to [U.S.] producers and employment of the same, similar, or competing commodity" (12 U.S.C. §635(e)(3)). |

| 25. |

12 U.S.C. §635i-5(a)(1). |

| 26. |

12 U.S.C. §635i-5(a)(2). |

| 27. |

The Ex-Im Bank Supplemental Guidelines for High-Carbon Projects (December 2013) state that: the Bank will not provide support for exports of high carbon intensity plants, except for high carbon intensity plants that (a) are located in the world's poorest countries, utilize the most efficient coal technology available and where no other economically feasible alternative exists, or (b) deploy carbon capture and sequestration (CCS), in each case, in accordance with the requirements set forth in these Supplemental Guidelines. Sec. 7062 of P.L. 116-6, the FY2019 Consolidated Appropriations Act, prohibits funding: …(4) for the enforcement of any rule, regulation, policy, or guidelines implemented pursuant to— …(C) the Supplemental Guidelines for High Carbon Intensity Projects approved by the Export-Import Bank of the United States on December 12, 2013, when enforcement of such rule, regulation, policy, or guidelines would prohibit, or have the effect of prohibiting, any coal-fired or other power-generation project the purpose of which is to: (i) provide affordable electricity in International Development Association (IDA)-eligible countries and IDA-blend countries; and (ii) increase exports of goods and services from the United States or prevent the loss of jobs from the United States. |

| 28. |

12 U.S.C. §635(b)(5). |

| 29. |