USDA Export Market Development and Export Credit Programs: Selected Issues

Agricultural exports are important to both farmers and the U.S. economy. With the productivity of U.S. agriculture growing faster than domestic demand, farmers and agriculturally oriented firms rely heavily on export markets to sustain prices and revenue. The 2014 farm bill (Agricultural Act of 2014, P.L. 113-79) authorizes a number of programs to promote farm exports that are administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). There are two main types of agricultural trade and export promotion programs:

Export market development programs assist efforts to build, maintain, and expand overseas markets for U.S. agricultural products. Programs include the Market Access Program (MAP), the Foreign Market Development Program (FMDP), the Emerging Markets Program (EMP), the Quality Samples Program (QSP), and the Technical Assistance for Specialty Crops Program (TASC).

Export financing assistance programs provide payment guarantees on commercial financing to facilitate U.S. agricultural exports. Programs include the Export Credit Guarantee Program (GSM-102) and the Facility Guarantee Program (FGP).

Annual funding for USDA’s export market promotion programs is authorized at about $255 million (not including reductions due to sequestration). In addition, USDA’s export credit guarantee programs provide commercial bank financing of up to $5.5 billion of U.S. agricultural exports annually. Funding for USDA’s programs is mandatory through the Commodity Credit Corporation and is not subject to annual appropriations.

USDA has commissioned a number of economic studies to assess the effects of its export market development programs on U.S. agricultural exports, export revenue, and other economy-wide effects. Most studies measure the “economic return ratio” or the ratio of the estimated returns compared to the estimated costs. USDA’s most recently commissioned study claims that MAP and FMDP return $28 for each dollar spent. USDA’s studies also claim broader economy-wide returns in terms of farm revenue, economic output, and full-time jobs.

However, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) has raised many questions regarding USDA’s export promotion programs. GAO’s reports have generally been critical of USDA-reported estimates of the economic effects of USDA’s programs on U.S. agricultural exports, export revenue, and other economy-wide effects. The most recent GAO report expressed ongoing concerns about USDA’s assessment methodologies for estimating program effectiveness, citing the need for improved methods and cost-benefit analysis. USDA’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) also conducted a review of its export market development programs and recommended certain changes with regard to data and information collection by program participants.

In anticipation of the next farm bill debate, legislation introduced in both the House and Senate (Cultivating Revitalization by Expanding American Agricultural Trade and Exports Act or CREAATE Act, H.R. 2321/S. 1839) would progressively double annual funding for MAP and FMDP to $400 million and $69 million, respectively, by 2023. The Coalition to Promote U.S. Agricultural Exports and the National Association of State Departments of Agriculture also support doubling funding for MAP and FMDP. However, some in Congress have long opposed USDA’s export and market promotion programs, especially MAP, calling for its elimination and/or reduced program funding. President Trump’s FY2018 budget proposes to eliminate both MAP and FMDP.

USDA Export Market Development and Export Credit Programs: Selected Issues

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- USDA Trade and Export Promotion Programs

- Compliance with International Trade Rules

- Evaluation of USDA's Export Market Programs

- Results of USDA-Commissioned Studies

- Critique of USDA's Methodologies and Estimates

- Support for USDA's Export Market Programs

- Opposition to USDA's Export Market Programs

- Other Federal Export Financing Programs

- Export-Import Bank

- Small Business Administration (SBA)

Figures

Summary

Agricultural exports are important to both farmers and the U.S. economy. With the productivity of U.S. agriculture growing faster than domestic demand, farmers and agriculturally oriented firms rely heavily on export markets to sustain prices and revenue. The 2014 farm bill (Agricultural Act of 2014, P.L. 113-79) authorizes a number of programs to promote farm exports that are administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). There are two main types of agricultural trade and export promotion programs:

- 1. Export market development programs assist efforts to build, maintain, and expand overseas markets for U.S. agricultural products. Programs include the Market Access Program (MAP), the Foreign Market Development Program (FMDP), the Emerging Markets Program (EMP), the Quality Samples Program (QSP), and the Technical Assistance for Specialty Crops Program (TASC).

- 2. Export financing assistance programs provide payment guarantees on commercial financing to facilitate U.S. agricultural exports. Programs include the Export Credit Guarantee Program (GSM-102) and the Facility Guarantee Program (FGP).

Annual funding for USDA's export market promotion programs is authorized at about $255 million (not including reductions due to sequestration). In addition, USDA's export credit guarantee programs provide commercial bank financing of up to $5.5 billion of U.S. agricultural exports annually. Funding for USDA's programs is mandatory through the Commodity Credit Corporation and is not subject to annual appropriations.

USDA has commissioned a number of economic studies to assess the effects of its export market development programs on U.S. agricultural exports, export revenue, and other economy-wide effects. Most studies measure the "economic return ratio" or the ratio of the estimated returns compared to the estimated costs. USDA's most recently commissioned study claims that MAP and FMDP return $28 for each dollar spent. USDA's studies also claim broader economy-wide returns in terms of farm revenue, economic output, and full-time jobs.

However, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) has raised many questions regarding USDA's export promotion programs. GAO's reports have generally been critical of USDA-reported estimates of the economic effects of USDA's programs on U.S. agricultural exports, export revenue, and other economy-wide effects. The most recent GAO report expressed ongoing concerns about USDA's assessment methodologies for estimating program effectiveness, citing the need for improved methods and cost-benefit analysis. USDA's Office of Inspector General (OIG) also conducted a review of its export market development programs and recommended certain changes with regard to data and information collection by program participants.

In anticipation of the next farm bill debate, legislation introduced in both the House and Senate (Cultivating Revitalization by Expanding American Agricultural Trade and Exports Act or CREAATE Act, H.R. 2321/S. 1839) would progressively double annual funding for MAP and FMDP to $400 million and $69 million, respectively, by 2023. The Coalition to Promote U.S. Agricultural Exports and the National Association of State Departments of Agriculture also support doubling funding for MAP and FMDP. However, some in Congress have long opposed USDA's export and market promotion programs, especially MAP, calling for its elimination and/or reduced program funding. President Trump's FY2018 budget proposes to eliminate both MAP and FMDP.

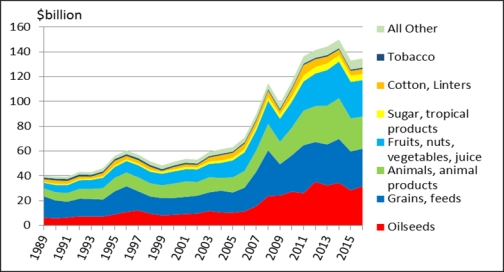

Agricultural exports are important to both farmers and the U.S. economy. In 2016, U.S. agricultural exports totaled nearly $135 billion. Major U.S. agricultural exports, by value, were oilseeds and grains, meat and animal products, tree nuts, and fruit and vegetable products (Figure 1). As U.S. agricultural production has grown faster than domestic demand, farmers and agriculturally oriented firms rely heavily on export markets to sustain prices and revenue. Accordingly, the 2014 farm bill (Agricultural Act of 2014, P.L. 113-79) authorizes a number of programs to promote farm exports. These programs are administered by the Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). This report also discusses how these programs comply with international trade rules under the World Trade Organization (WTO). Other federal agencies also play a role in supporting agricultural exports through various finance, insurance, and loan programs.

Following an overview of USDA's export promotion programs, this report describes available research and analysis of the effectiveness of these programs, highlighting advocacy positions both for and against USDA's programs. These programs could become an issue for Congress in the next farm bill debate: Legislation introduced in both the House and the Senate seeks to double available annual funding for some of these programs, while others in Congress who have long opposed these programs have called for reduced funding and/or program elimination.

|

|

Source: CRS from USDA trade (https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/default.aspx). |

USDA Trade and Export Promotion Programs

USDA's FAS administers a series of programs to develop export markets for U.S. agricultural products.1 These programs are authorized in periodic omnibus farm bills.2

USDA administers two types of agricultural trade and export promotion programs:

- 1. Export market development programs assist U.S. industry efforts to build, maintain, and expand overseas markets for U.S. agricultural products. USDA administers five programs: the Market Access Program (MAP), the Foreign Market Development Program (FMDP), the Emerging Markets Program (EMP), the Quality Samples Program (QSP), and the Technical Assistance for Specialty Crops (TASC) program. In general, these programs provide matching funds to U.S. organizations to conduct a wide range of activities, including information and market research, consumer promotion, counseling and assistance, trade servicing, capacity building, and market access support to potential U.S. exporters of agricultural products.

- 2. Export financing assistance programs, such as the Export Credit Guarantee Program (GSM-102) and the Facility Guarantee Program (FGP), provide payment guarantees on commercial financing to facilitate U.S. agricultural exports. These programs provide loan guarantees to lower the cost of borrowing to foreign countries to buy U.S. agricultural products. GSM-102 guarantees repayment of commercial financing by approved foreign banks, mainly of developing countries, for up to two years for the purchase of U.S. farm and food products. FGP guarantees financing of goods and services exported from the United States to improve or establish agriculture-related facilities in emerging markets.

Table 1 and Table 2 and provides additional information on these programs.3

The 2014 farm bill reauthorized many of these programs and extended their funding through FY2018. Funding for USDA's market development and export assistance programs is mandatory through the borrowing authority of the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC)4 and therefore is not subject to annual appropriations. Annual mandatory CCC funding for USDA's export market promotion programs is authorized at approximately $255 million (not including reductions due to sequestration).

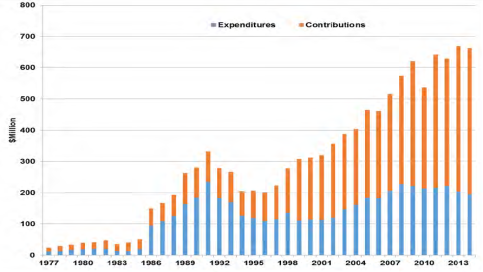

MAP and FMDP account for more than 90% of authorized funding for USDA's export market promotion programs. In recent years, as reported by USDA, annual funding allocations for these two programs have averaged about $200 million (FY2014-FY217), reflecting sequestration reductions and other reductions.5 However, both MAP and FMDP require some type of contribution or (in some cases) matching funds by USDA's industry partners. Contributions by industry partners have been increasing, accounting for more than 70% of total MAP and FDMP funding in 2014. Estimated total available funds for these two programs (of combined public and private funding) was roughly $680 million (based on USDA-reported data for 2014) (Figure 2). USDA reports program administration costs for MAP and FMDP at between $6.3 million and $7.0 million.6

|

Market Access Program (MAP) Helps finance activities to market and promote U.S. agricultural commodities and products worldwide. USDA partners with U.S. agricultural trade associations, cooperatives, state and regional trade groups, and small businesses to share the costs of overseas marketing and promotional activities that help build commercial export markets. USDA provides cost-share assistance to eligible U.S. organizations for activities such as consumer advertising, public relations, participation in trade fairs and consumer exhibits, electronic and print media advertising, point-of-sale demonstrations, brand development, market research, and technical assistance. Funds used for generic marketing and promotion require a minimum 10% contribution. Promotion of branded products requires a dollar-for-dollar match. Mandatory CCC funding is authorized at $200 million annually through FY2018. USDA-reported funding allocations in FY2017 were $173.5 million. |

Emerging Markets Program (EMP) Provides funding for technical assistance activities to promote U.S. agricultural exports to emerging markets worldwide. EMP helps U.S. organizations promote U.S. exports to countries that have or are developing market-oriented economies and that have the potential to be viable commercial markets. USDA provides cost-share funding for technical assistance activities such as feasibility studies, market research, sectorial assessments, orientation visits, specialized training, and business workshops. EMP supports exports of generic U.S. agricultural commodities and products: Projects that endorse or promote branded products or specific companies are not eligible. Mandatory CCC funding is authorized at $10 million annually through FY2018. |

|

Foreign Market Development Program (FMD) Provides cooperator organizations with cost-share funding for activities that help create, expand, and maintain long-term export markets for U.S. agricultural products. USDA partners with U.S. agricultural producers and processors, who are represented by nonprofit commodity or trade associations ("cooperators"), to promote U.S. commodities overseas. FMD focuses on generic promotion of U.S. commodities. Preference is given to organizations that represent an entire industry or are nationwide in membership and scope. Funded projects generally address long-term opportunities to reduce foreign import constraints or expand export growth opportunities. These include projects that:

|

Technical Assistance for Specialty Crops (TASC) Funds projects that address sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) and technical barriers to trade (TBT) that prohibit or threaten the export of U.S. specialty crops. Eligible activities include seminars and workshops, study tours, field surveys, pest and disease research, and pre-clearance programs. Eligible crops include all cultivated plants and their products produced in the United States except wheat, feed grains, oilseeds, cotton, rice, peanuts, sugar, and tobacco. TASC is intended to benefit an entire industry or commodity rather than a specific company or brand. U.S. nonprofit, for-profit, and government entities are all eligible to apply. Proposals may target individual countries or reasonable regional groupings of countries. Mandatory CCC funding is authorized at $9 million annually through FY2018. |

|

Quality Samples Program (QSP) Assists U.S. agricultural trade organizations by providing small samples of their products to potential importers in emerging markets overseas. Allows overseas manufacturers to assess how U.S. food and fiber products can best meet their production needs, focusing on industry and manufacturing, as opposed to end-use consumers. Mandatory CCC funding has ranged from about $1million to $2 million annually. QSP was authorized under Section 5(f) Commodity Credit Corporation Charter Act Charter Act (15 U.S.C. §714c(f)), as amended. |

Source: USDA, "Market Development and Export Assistance," https://www.fas.usda.gov/about-fas.

|

Export Credit Guarantee Program (GSM-102) Guarantees payment against default when U.S. commercial banks extend credit to foreign banks to finance sales of U.S. agricultural products. Credit guarantees encourage financing of commercial exports of U.S. agricultural products. By reducing financial risk to lenders, credit guarantees encourage exports to foreign buyers (mainly in developing countries) that have sufficient financial strength to have foreign exchange available for scheduled payments. The program is available to exporters of:

In 2015, the largest markets covered by the program were South America, Mexico, and South Korea. Commodities registered most were bulk commodities (soybeans, corn, wheat, meal, and rice) but also sales of fruit, wine, wood and wood products, animal hides, and other high-value commodities. Under the program, a CCC guarantee typically covers 98% of the port value of the export item, determined at the U.S. point of export, plus a portion of interest on the financing. Guarantee coverage is usually limited to the value of the commodity only, even though the sale may have been made on a cost and freight or cost, insurance, and freight basis. Under unusual circumstances, however, the CCC may offer coverage on credit extended for freight costs. Available mandatory CCC funds are authorized up to $5.5 billion annually. The program was initially authorized under the Agricultural Trade Act of 1978 (7 U.S.C. §5622), as amended. |

Facility Guarantee Program (FGP) Designed to boost sales of U.S. agricultural products in countries where demand may be limited due to inadequate storage, processing, handling, or distribution capabilities. Provides payment guarantees to facilitate the financing of manufactured goods and U.S. services to improve or establish agriculture-related facilities in emerging markets where private sector financing is otherwise not available.

|

Source: USDA, "Market Development and Export Assistance," https://www.fas.usda.gov/about-fas; USDA, "What Every Importer Should Know About the GSM-102 and GSM-103 Programs," November 1996, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/excredits/english.html; and Office of Management and Budget, Budget of the U.S. Government, FY2018, appendix, https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Appendix.

USDA's GSM-102 export credit guarantee program facilitates commercial bank financing of up to $5.5 billion of U.S. agricultural exports annually.7 The program's total guarantee value has been reported at $2.1 billion in FY2016 and about $3.5 billion in FY2017.8 Under the program, CCC does not provide financing per se but guarantees payments due from foreign banks and buyers—usually guaranteeing 98% of the principal payment due and interest rates based on a percentage of the one-year Treasury rate.9 Given that the program's repayment terms (from nine to 18 months), budgetary outlays are mostly associated with administrative expenses totaling about $7 million annually.10

|

Figure 2. USDA Export Market Development Program Funding, 1977-2014 Federal Expenditures and Private Sector Contributions |

|

|

Source: FAS (cited in Informa Economics IEG, Economic Impact of USDA Export Market Development Programs, report prepared for the U.S. Wheat Associates, the USA Poultry and Egg Export Council, and the Pear Bureau Northwest, July 2016, https://www.fas.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2016-10/2016econimpactsstudy.pdf). Notes: MAP was established in 1985 as the Targeted Export Assistance program (Food Security Act of 1985, P.L. 99-198, §1124), replaced with the Market Promotion Program (Food, Agriculture, Conservation, and Trade Act of 1990, P.L. 101-624, §§1531, 1572(3)), and then renamed MAP (Federal Agriculture Improvement and Reform Act of 1996, P.L. 104-127, §244). FMDP was first established by the Agricultural Trade Development and Assistance Act of 1954 and reauthorized in 1996 by an amendment to Title VII of the Agricultural Trade Act of 1978 (P.L. 480) and Federal Agriculture Improvement and Reform Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-127, Title II, § 252). |

Compliance with International Trade Rules

As a member of the WTO, the United States has committed to abide by WTO rules and disciplines, including those that govern the use of and funding for export subsidies as well as domestic farm support measures.11 Both export subsidies and domestic farm support measures were subject to reduction commitments under WTO's Agreement on Agriculture (AoA), which entered into force in 1995.12 AoA also requires that member countries notify the WTO Committee on Agriculture annually with respect to export subsidies and other forms of agricultural domestic support measures.13 USDA's market development and export assistance programs, however, were not subject to commitment reductions, nor are they notified to the WTO under rules governing notification of export subsidies or domestic farm support measures.14

Under WTO rules, market research and promotion services are generally considered to be "green box"15 policies and not subject to commitment reductions. Such services mostly provide information and technical assistance, involve public-private partnerships, and (unlike export subsidies) do not lower prices to foreign buyers.16 As a justification for exemption from WTO rules, some also continue to cite a provision initially included in the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM Agreement, Article 8).17 The provision (now lapsed) identified certain "Non-Actionable Subsidies" to include generic research and promotion.18

By contrast, some export subsidies are considered "amber box" and are subject to limits under WTO rules.19 Export subsidies include direct subsidies (e.g., "payments-in-kind, to a firm, to an industry, to producers of an agricultural product, to a cooperative or other association of such producers, or to a marketing board, contingent on export performance"); the sale or disposal for export by governments of agricultural products at below-market prices; payments financed from the proceeds of government taxes imposed on an agricultural product; subsidies to reduce the costs of marketing exports of agricultural products; and internal transport and freight charges on export shipments, among other types of subsidies.20 The SCM Agreement's Annex I (Illustrative List of Export Subsidies) item (j) further lists among other types of export subsidies21

[t]he provision by governments (or special institutions controlled by governments) of export credit guarantee or insurance programs, of insurance or guarantee programs against increases in the cost of exported products or of exchange risk programs, at premium rates which are inadequate to cover the long term operating costs and losses of the programs.

Export subsidies were further addressed as part of both the WTO's Bali Ministerial Decision (December 2013)22 and the Nairobi Ministerial Decision (December 2015).23 Member countries agreed to exercise "utmost restraint" with regard to the use of export subsidies and other forms of "export competition" policies that have the effect of subsidizing exports in international markets. "Export competition" policies include direct export subsidies, export credits, export credit guarantees or insurance programs, international food aid, and agricultural exporting state trading enterprises.24 The Nairobi Ministerial Decision also specified certain terms and conditions for conformity regarding export financing support: Maximum repayment terms should be no more than 18 months, and such support should be self-financing (via fees or contract premiums charged). To obtain a guarantee, an exporter has to pay premium rates (i.e., fees) charged to program beneficiaries and should adequately cover the long-term operating costs of the program, thus avoiding imparting an implicit subsidy benefit. Fees are generally calculated on the basis of guaranteed value, according to a schedule of rates applicable to different credit terms and repayment intervals.

U.S. trade officials have long argued that the U.S. export credit guarantee programs are consistent with WTO obligations and not subject to reduction commitments.25 Furthermore, the United States has asserted that the AoA (Article 10.2) reflects the deferral of disciplines on export credit guarantee programs until the next WTO multilateral negotiating round (Doha Round). The United States' most recent U.S. notification to the WTO concerning its export subsidy commitments covers 2014 and shows zero outlays and zero quantities of subsidized agricultural products for the year.26 Nevertheless, as part of the 2014 farm bill (P.L. 113-79, §3101), Congress shortened the loan term on which export credit guarantees would be made available from 36 months to 24 months in order to conform to U.S. WTO commitments. In practice, USDA currently limits the term of loan guarantees under GSM-102 to a maximum of 18 months.27 Congress also authorized USDA to make other changes to the GSM-102 program to meet the terms and conditions of the 2010 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between Brazil and the United States related to the WTO cotton dispute. (See text box on next page for more information on the dispute.) USDA implemented subsequent changes to the program in 2014, further addressing repayment terms and guarantee fees, among other changes.28

In general, the United States abides by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development Arrangement on Officially Supported Export Credits (OECD Arrangement) in its export credit financing activities involving other federal agencies. The OECD Arrangement establishes minimum interest rates, maximum repayment terms, guidelines for classifying risks, and other terms and conditions for government-backed export financing. Export credit financing that is covered by the OECD Arrangement is generally exempt from the WTO SCM Agreement. The SCM Agreement has been interpreted to indicate that, for non-agricultural products, an export credit practice in conformity with the OECD Arrangement on export credits shall not be considered as an export subsidy prohibited by the SCM Agreement.29

|

The GSM-102 Program and Brazil's WTO Case Against the U.S. Cotton Program In 2002, Brazil initiated WTO consultations with the United States involving "subsidies provided to US producers, users and/or exporters of upland cotton, as well as legislation, regulations, statutory instruments and amendments thereto providing such subsidies (including export credits), grants, and any other assistance to the US producers, users and exporters of upland cotton." The case involved a number of issues raised by the Brazilians including measures and obligations under both the AoA and the SCM Agreement, including its Annex I (Illustrative List of Export Subsidies). Following is a discussion of the case's actions involving U.S. export credit guarantee programs. For information about other aspects of the WTO case, see CRS Report RL32571, Brazil's WTO Case Against the U.S. Cotton Program. Regarding U.S. export credit guarantees, Brazil claimed that the favorable terms (i.e., the interest rate and time period that countries have to pay back the financing) provided under U.S. export credit guarantee programs were effectively export subsidies inconsistent with the WTO's AoA and SCM Agreements. These programs included three principal export credit guarantee programs that the United States was operating to facilitate the export of U.S. agricultural products (including but not limited to cotton) at the time that Brazil initiated the case. These were the GSM-102 program (which extended credit for periods ranging from 90 days to three years), the GSM-103 Intermediate Export Credit Guarantee Program (which extended credit for periods of more than three years but not more than 10 years), and the Supplier Credit Guarantee Program (SCGP)—all CCC-funded export credit guarantee programs. The GSM-103 and SCGP programs were part of Brazil's original case. These two programs were eliminated as part of the 2008 farm bill (P.L. 110-246; §3101(a)). Brazil also argued that the GSM-102 program operated as a prohibited export subsidy under the SCM Agreement regarding export credit guarantees (Annex I, item (j)) because the premium rates (i.e., fees) "paid by the exporter to obtain a guarantee were inadequate to cover the long-term operating costs of the program, thus imparting an implicit subsidy benefit. U.S. trade officials argued that the U.S. export credit guarantee programs were consistent with WTO obligations. However, the WTO Appellate Body upheld the dispute panel's finding that export credit guarantee programs "constitute a per se export subsidy within the meaning of item (j) of the Illustrative List of Export Subsidies in Annex I of the SCM Agreement" as well as the panel's findings that these export credit guarantee programs are export subsidies under the SCM Agreement and are inconsistent with Articles 3.1(a) and 3.2 of the SCM Agreement (para. 763). The United States made changes to its GSM-102 program in 2014 as part of the 2014 farm bill (P.L. 113-79, §3101) and in subsequent USDA rulemaking (70 Federal Register 68589). These changes addressed repayment terms and fees, among other changes, reflecting terms and conditions in the 2010 MOU between Brazil and the United States related to the cotton dispute. Source: CRS Report RL32571, Brazil's WTO Case Against the U.S. Cotton Program; WTO, "DS267: United States, Subsidies on Upland Cotton," https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds267_e.htm; and WTO, "United States – Subsidies on Upland Cotton," AB-2004-5WT/DS267/AB/R, March 3, 2005, p. 293. The SCM Agreement and Annex I (Illustrative List of Export Subsidies) are available at https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/24-scm_03_e.htm. The U.S.-Brazil 2010 MOU is at https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/20141001201606893.pdf. |

Evaluation of USDA's Export Market Programs

Results of USDA-Commissioned Studies

USDA has commissioned a number of economic studies to assess the effects of USDA's export market development programs on U.S. agricultural exports, export revenue, and other economy-wide effects, including impacts on the farm economy, macroeconomic output, and full-time U.S. civilian jobs. These studies utilize various approaches, including computable general equilibrium models, IMPLAN (IMpact Analysis for PLANning) input-output models, and benefit-cost ratios, among other types of methodological approaches. These studies often yield widely differing results. Similar studies have not been conducted to assess the effectiveness of USDA's export credit programs.

Most studies measure the "economic return ratio," or the ratio of the estimated returns compared to the estimated costs. Economic return estimates from these studies range from $24 to $37 for each dollar spent on FAS's market development programs (generally focused on MAP and FMDP). A summary of these studies is posted at https://www.agexportscount.com/resources/. USDA's most recent commissioned study suggests that MAP and FMDP return $28 for each dollar spent on these programs.30 This updates a 2010 USDA-commissioned study that estimated that U.S. food and agricultural exports increased by $35 for every additional $1 spent by government and industry on market development.31 Other estimates by USDA indicate that FAS market development programs return $37 for each dollar spent on the programs.32 The National Association of State Departments of Agriculture (NASDA) finds that the return on investment from MAP is $24 for every $1 spent in foreign market development.33

These studies make additional claims regarding the broader economy-wide returns in terms of farm revenue, economic output, and full-time U.S. jobs. USDA's most recently commissioned study states that spending on MAP and FMDP resulted in increased export volumes, higher prices, and greater farm income levels. These studies regularly include other estimates such as changes in economic output, gross domestic product, labor income, and U.S. economic welfare. Specifically, USDA's most recent study concludes that from 2002 to 2014, MAP and FMDP added $12.5 billion to export value and added $1 billion to $2 billion to farm income on average annually (depending on the modeling approach used). The study also concludes that MAP and FMDP added up to 240,000 full- and part-time jobs across the entire U.S. economy over the 2002-2014 period.34

Because the estimated benefits of USDA's programs are large relative to the cost of these programs, some contend that the programs are vastly underfunded from an economic optimization standpoint.35

Critique of USDA's Methodologies and Estimates

Over the years, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) has raised many questions regarding USDA's export promotion programs. These reports have generally been critical of USDA-reported estimates of the economic effects of its export market development programs on U.S. agricultural exports, export revenue, and other economy-wide effects.

The most recent of these reports, in 2013, expressed ongoing concerns about USDA's assessment methodologies for estimating program effectiveness, citing the need for improved methods and cost-benefit analysis.36 Regarding the study USDA commissioned in 2010, GAO concluded that methodological limitations may affect the accuracy and magnitude of USDA's estimated benefits. GAO criticized this study because "the model used to estimate changes in market share omitted important variables and, second, a sensitivity analysis of key assumptions was not conducted for that and another model that the study used," among other types of concerns. These criticisms may have prompted USDA's more recent 2016 commissioned study.37 GAO's report further highlighted that USDA's program funding has been spent on a consistent set of participants and in a consistent group of countries. It also confirmed that industry contributions often exceed matching contribution requirements (Figure 2). GAO also noted the potential (despite management efforts) for duplication risks38 and cited the need to improve reporting requirements for program participants.

Previously, in a 1997 report, GAO concluded that "no conclusive evidence exists that these programs have measurably expanded aggregate employment and output or reduced the trade and budget deficits."39 GAO also concluded that there is "limited evidence" of benefits to the U.S. agricultural sector in terms of farm income and employment. GAO identified a "lack of transparency" in participant reporting as contributing to the limitations in USDA's analysis. GAO further noted that "there are widely divergent views about the amount of leverage these programs provided in the past." GAO's recommendations focused on the need for USDA to develop more systematic information on the potential strategic value of USDA's export assistance programs.

In its 1997 review, GAO also noted that other economic factors are often more important in influencing export markets, such as expanding global markets and rising demand for U.S. products, making it difficult to determine how USDA's export assistance programs may be influencing U.S. export markets. Other economic studies reviewed as part of GAO's 1997 review indicate that evidence is mixed regarding the relevance of export assistance program, especially in terms of impacts to the overall economy, the U.S. agricultural sectors, and specific products. A 1999 GAO review further concluded that "few studies show an unambiguously positive effect of government promotional activities on exports."40 Other studies GAO reviewed found "no evidence that advertising and promotion expenditures had an expansionary effect" on foreign demand for some agricultural products.

Other GAO assessments of USDA's export assistance programs have been similarly critical.41 During the 1990s, GAO testified and made recommendations to Congress on a range of issues regarding USDA's export programs, including the need for USDA to improve its agricultural trade office operations and program management and strategic planning,42 as well as the need to assess the benefits of these programs and provide assurances that public funds are being spent effectively.43

USDA's Office of Inspector General (OIG) also conducted a review of USDA's export market development programs to determine whether these programs foster expanded trade activities in the exporting of U.S. agricultural products. The review focused on data and information collection under MAP.44 OIG recommended that USDA "identify those areas where tracking and analyzing specific data would be useful to the agency's efforts to expand exports of U.S. agricultural products, and based on this documented analysis, implement a formal system to track this information." This included implementing "methodologies to ensure participants conduct periodic program evaluations to effectively measure their accomplishments with MAP funding" in addition to implementing standard reporting requirements. OIG also recommended that USDA conduct more outreach and provide information on foreign trade constraints and business opportunities.

Support for USDA's Export Market Programs

The Coalition to Promote U.S. Agricultural Exports consists of more than 75 organizations representing farmers, ranchers, fishermen, forest product producers, cooperatives, small businesses, regional trade organizations, and the state departments of agriculture that are actively supporting the continuation and expansion of USDA's export market development programs. (Other sponsor groups include the Coalition to Promote Agricultural Exports, the Agribusiness Coalition for Foreign Market Development, and the U.S. Agricultural Export Development Council).45 The coalition continues to express its support for MAP and other USDA export programs,46 building on its efforts in prior years.47

In anticipation of the next farm bill debate, legislation introduced in both the House and Senate (Cultivating Revitalization by Expanding American Agricultural Trade and Exports Act, or CREAATE Act, H.R. 2321/S. 1839) would double annual funding for MAP and FMDP to $400 million and $69 million, respectively, by 2023. The coalition supports doubling funding for MAP and FMDP.48 NASDA also supports doubling annual MAP funding.49

Researchers point out that government intervention is warranted in the case of market promotion to address market failure50 and to avoid the "free rider" problem. For example, in this case, if no single exporter has an incentive to spend his/her own resources on export market promotion, this could result in underinvestment in the market.51 Researchers also note that, alternatively, if someone were to invest in export market promotion, others would not see the need to contribute and instead would "free ride" (i.e., benefit from market promotion efforts without paying for it).52 Others cite the need to proactively promote U.S. exports to communicate to foreign buyers what differentiates U.S. farm products from those of other global suppliers53 and to offset subsidies offered by some U.S. competitors, such as in the European Union.54

Opposition to USDA's Export Market Programs

Some in Congress have long opposed some of USDA's export and market promotion programs, especially MAP, and have called for their elimination and/or reduced program funding.55 President Trump's FY2018 budget also proposes to eliminate both MAP and FMDP.56 MAP has also been targeted by outside groups, including the Heritage Foundation,57 Citizens Against Government Waste,58 Taxpayers for Common Sense,59 and National Taxpayers Union (NTU).60

Previous legislation has sought to limit federal spending on some export promotion programs through the appropriations process. For example, an amendment (S.Amdt. 3323, Flake) to the FY2015 Agricultural Appropriations minibus bill (H.R. 4660, 113th Congress) would have prohibited USDA from spending money to fund QSP. The amendment was not agreed to. Another amendment (H.Amdt. 480, Flake) to the FY2012 Agricultural Appropriations House bill (H.R. 2112, 112th Congress) would have prohibited USDA from using available funds to carry out MAP. That amendment was also not agreed to.

Other Members of Congress have proposed legislative changes to MAP as well. During the 2014 farm bill debate, an amendment (S.Amdt. 1007, McCain/Coburn) to the Senate farm bill (S. 954, 113th Congress) would have (1) reduced MAP funding by 20%, (2) prohibited the use of funding for certain activities (including animal spa products; reality television shows; cat or dog food or other pet food; wine, beer and spirits tastings, festivals, or other related activities; and cheese award shows and contests); and (3) required USDA to disclose annually all MAP-related travel-related expenses. No vote was taken on the amendment.61

Some contend that MAP funding is corporate welfare that subsidizes overseas advertising. These critics point to funding provided to some large companies—including Welch Food, Sunkist Growers, Blue Diamond Growers, Sunsweet, Sun-Maid, Cal-Pure Pistachios, and Ocean Spray—as well as other large producer groups such as the California Wine Institute, Brewers Association, Cotton Council International, and the Pet Food Institute. GAO reported that, in 2011, about 85% of MAP funding was spent on overseas promotion of generic commodities while the remaining 15% was spent to promote branded products.62

Other Federal Export Financing Programs

In addition to USDA's export financing assistance through GSM-102 and FGP, other federal agencies also provide assistance to U.S. agricultural exporters such as the Export-Import Bank (Ex-Im Bank) and the Small Business Administration (SBA).63

These agencies provide support to both agricultural and non-farm exporting companies. However, data and information are not publicly available to indicate the extent to which these agencies have provided support to agricultural exporters.

Export-Import Bank64

Ex-Im Bank, a wholly owned U.S. government corporation, finances and insures U.S. exports of goods and services in order to support U.S. jobs. It aims to do so when the private sector is unwilling or unable to finance exports alone at commercially viable terms and/or to counter financing offered by foreign countries through their counterparts to Ex-Im Bank.65 Ex-Im Bank takes the lead in financing and insuring non-agricultural U.S. exports66 but also plays a role in supporting agricultural exports through its finance and insurance programs.

Structurally, agricultural export support through Ex-Im Bank and USDA takes place through separate operations. However, by statute, Ex-Im Bank's agricultural export support is influenced by USDA's programs and positions. Specifically, Ex-Im Bank's charter67 states that it must supplement, but not compete with, private capital or the CCC agricultural commodity programs.68 In addition, the charter requires Ex-Im Bank, in carrying out its agricultural export support, to (1) consult with the Secretary of Agriculture, (2) take into consideration any recommendations that the Secretary of Agriculture makes against Ex-Im Bank financing the export of a particular agricultural commodity, and (3) consider the importance of agriculture commodity exports to the U.S. export market and the nation's trade balance in deciding whether or not to provide agricultural export support.

Ex-Im Bank's charter also requires the bank, when providing agricultural export support, to seek to minimize competition in government-backed export financing. It is further required to cooperate with other U.S. government agencies to seek international agreements to reduce what it refers to as government-subsidized export financing. The United States has negotiated with other OECD members on agreed disciplines for government-backed export credit financing.

In terms of agriculture, historically, the view was that Ex-Im Bank focused on export financing of agricultural equipment and inputs, while USDA focused on export financing of agricultural commodities.69 However, Ex-Im Bank's role in supporting agricultural exports appears to have evolved to include

- agricultural commodities and consumables (e.g., grain, soil additives) through its short-term insurance program;

- livestock through its short- or medium-term programs;

- the export of agricultural equipment (various machinery, such as seeders and combines), through its medium-term financing; and

- the export of goods and services for agricultural projects (e.g., meat processing facilities) through project financing.70

Ex-Im Bank's short-term export credit insurance programs are comparable to USDA's GSM-102 program in their availability to support U.S. agricultural commodity exports. Ex-Im Bank's direct loan, loan guarantee, and insurance programs have been characterized as comparable to USDA's FGP in their availability to support U.S. agricultural capital goods exports.71

Support for agricultural goods and services by Ex-Im Bank constitutes a small share of Ex-Im Bank's total authorizations and estimated total U.S. exports supported. In addition, it is significantly less than the amount that USDA directs to agricultural export financing.72 For instance, in FY2016, Ex-Im Bank authorized over $190 million (out of $5 billion in total authorizations) to support nearly $520 million of U.S. agricultural exports (out of $8 billion in total U.S. exports estimated to be supported by Ex-Im Bank).73 In comparison, GSM-102 program's total guarantee value was $2.1 billion in FY2016 and $3.5 billion in FY2017.74 Other differences between USDA and Ex-Im programs vary also in terms of mission, eligibility, repayment terms, and specific program requirements.75

Given that Ex-Im Bank and USDA both support U.S. agricultural exports through similar tools, policymakers have periodically raised questions about whether their activities are duplicative. On one hand, the agencies have different missions and have fashioned their programs accordingly to serve different constituencies. As such, the programs have different features. For example, if USDA-supported export financing is unavailable due to program restrictions or the sales contract terms proposed by the foreign buyer, Ex-Im Bank support may be an alternative.76 On the other hand, the diffusion of agricultural export financing services across two agencies may cause confusion for U.S. businesses and raise inefficiencies in the provision of government services.

Small Business Administration (SBA)77

SBA administers several types of programs to support small businesses, including loan guarantee and venture capital programs to enhance small business access to capital; contracting programs to increase small business opportunities in federal contracting; direct loan programs for businesses, homeowners, and renters to assist their recovery from natural disasters; and small business management and technical assistance training programs to assist business formation and expansion.

With respect to international trade, SBA provides financial assistance, technical assistance, and grants to states for the purposes of supporting small businesses (generally defined as firms with fewer than 500 employees) involved in international trade.78 SBA serves all businesses defined as "small" by the agency, and it makes no distinction among exporters in different industries for the purposes of its trade and export promotion programs.79

SBA has three variations of its broader financing programs that are targeted to exporters:

- 1. The Export Express loan program, which provides working capital or fixed asset financing for small businesses that will begin or expand exporting,

- 2. The Export Working Capital loan program, which provides financing to support export orders or the export transaction cycle from purchase order to final payment, and

- 3. The International Trade loan program, which provides long-term financing to support small businesses that are expanding because of growing export sales or have been adversely affected by imports and need to modernize to meet foreign competition.

All of SBA's loan guarantee programs require personal guarantees from borrowers and share the risk of default with lenders by making the guarantee less than 100%. Compared to its more general purpose business loan guarantees, though, SBA provides a higher rate of guarantee on the principal value of loans issued through its export financing programs (ranging from 75% to 90% in the trade loans, depending on the purpose and size of the loan, compared to 50% to 85% in the more general business loan guarantee programs).80 SBA provides loan guarantees for small businesses that cannot obtain credit elsewhere. In FY2016, SBA guaranteed $1.55 billion in loans to 1,550 small business exporters.81

In terms of technical assistance, SBA's Office of International Trade works in coordination with SBA district offices, resource partners (such as Small Business Development Centers), and U.S. Export Assistance Centers to provide technical assistance to small businesses that are looking to start exporting or already export.

SBA also awards grants to states through its State Trade Expansion Program (STEP) for various activities intended to increase the number and volume of small business exports, such as participation in foreign trade missions, trade show exhibitions, or export training workshops. SBA's most recent round of STEP awards for FY2017 totaled $18 million.82

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

FAS "links U.S. agriculture to the world to enhance export opportunities and global food security." USDA, "About FAS," https://www.fas.usda.gov/about-fas. |

| 2. |

For more information on the farm bill, see CRS In Focus IF10187, The 2014 Farm Bill (Agricultural Act of 2014); and CRS Report R43076, The 2014 Farm Bill (P.L. 113-79): Summary and Side-by-Side. Unlike most of these programs, the Quality Samples Program was authorized under the Commodity Credit Corporation Charter Act Charter Act (15 U.S.C. §714), as amended. |

| 3. |

For more detail on these programs, see USDA's website at https://www.fas.usda.gov/programs. See also testimony before the House Agriculture Committee, Subcommittee on Rural Development, Research, Biotechnology, and Foreign Agriculture, "Hearing to Review Market Promotion Programs and their Effectiveness on Expanding Exports of U.S. Agricultural Products," April 7, 2011; and CRS Report R43696, Agricultural Exports and 2014 Farm Bill Programs: Background and Current Issues. |

| 4. |

For more information, see CRS Report R44606, The Commodity Credit Corporation: In Brief. |

| 5. |

Based on annual funding allocations reported by USDA at https://www.fas.usda.gov/programs. |

| 6. |

USDA, "2017 President's Budget Foreign Agricultural Service," p. 33-5. |

| 7. |

A portion of the GSM-102 guarantees—about $500 million—is made available as Facilities Guarantees whereby the CCC guarantees export financing for capital goods and services to improve handling, marketing, processing, storage, or distribution of imported agricultural commodities and products. |

| 8. |

GSM-102, FY2016 Year Activity Report, and USDA, "FY2017 GSM-102 Allocations" (as of September 22, 2017). |

| 9. |

Office of Management and Budget, Appendix of the Budget of the U.S. Government, FY2018, p. 105. |

| 10. |

Ibid. For additional information, see USDA, "2017 President's Budget Foreign Agricultural Service," p. 33-29. |

| 11. |

WTO's Agreement on Agriculture (AoA) also spells out the rules for countries to determine whether their policies for any given year are potentially trade-distorting, how to calculate the costs of any distortion, and how to report those costs to the WTO in a public and transparent manner. For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10192, WTO Disciplines of Domestic Support for Agriculture; and CRS Report RS20840, Agriculture in the WTO: Rules and Limits on Domestic Support. |

| 12. |

The agreement is available at https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/14-ag_01_e.htm. Agricultural products are those defined in AoA, Annex 1, https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/14-ag_02_e.htm#annI. |

| 13. |

Only export subsidies that have been notified in each WTO Member's country schedule are permitted. Each countries' schedule specifies both how much can be exported with subsidy as well as the permitted subsidy expenditure for each listed commodity. For more information, see pp. 9-12 of CRS Report RL32916, Agriculture in the WTO: Policy Commitments Made Under the Agreement on Agriculture. |

| 14. |

CRS communications with USDA personnel, September 15, 2017. See WTO Committee on Agriculture, "Domestic Support: United States" (Reporting Period 2012), G/AG/N/USA/100/Rev. 1, February 3, 2017. |

| 15. |

The WTO uses a traffic light analogy to classify programs, and "green box" programs are minimally or non-trade distorting and exempted from spending limits. See AoA, Annex 2, https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/14-ag_02_e.htm#annII. |

| 16. |

J. J. Reimer et al., "Agricultural Export Promotion Programs Create Positive Economic Impacts," CHOICES Magazine, 3rd Quarter 2017; and P. De Baere and C. du Parc, "Export Promotion and the WTO: A Brief Guide," International Trade Center, 2009. |

| 17. |

The SCM Agreement disciplines the use of export subsidies and the actions countries can take to counter the effects of these subsidies. For more information, see WTO, "Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures," https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/24-scm_01_e.htm. |

| 18. |

See, for example, De Baere and du Parc, "Export Promotion and the WTO." |

| 19. |

Only export subsidies that have been notified in each WTO member's country schedule are permitted. Each countries' schedule specifies both how much can be exported with subsidy as well as the permitted subsidy expenditure for each listed commodity. Under AoA, all domestic support in favor of agricultural producers is subject to rules, and the aggregate monetary value of amber box measures is, with certain exceptions, subject to reduction commitments as specified in the schedule of each WTO member providing such support. The reductions occurred over two time periods: 1995 to 2000 for developed nations and 1995 to 2005 for self-identified developing nations. Special terms applied for Least-Developed Countries. For more information, see CRS Report RL32916, Agriculture in the WTO: Policy Commitments Made Under the Agreement on Agriculture, pp. 9-12. |

| 20. |

AoA (Article 9). For a full listing, see WTO, "Export Competition/Subsidies," https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/agric_e/ag_intro04_export_e.htm. |

| 21. |

SCM Agreement, Annex I (j), https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/24-scm_03_e.htm#annI. |

| 22. |

WTO, Export Competition, Ministerial Decision of 7 December 2013, WT/MIN(13)/40, WT/L/915. |

| 23. |

WTO, Export Competition, Ministerial Decision of 19 December 2015, WT/MIN(15)/45—WT/L/980. |

| 24. |

Ibid. See also CRS Report R43592, Agriculture in the WTO Bali Ministerial Agreement. |

| 25. |

See, for example, CRS Report RL32571, Brazil's WTO Case Against the U.S. Cotton Program, p. 8; and WTO, "United States, Subsidies on Upland Cotton," https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds267_e.htm. |

| 26. |

WTO Committee on Agriculture, "Export Subsidies: United States" (Reporting Period 2014), G/AG/N/USA/112, March 30, 2017. Reports are available at https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/countries_e/usa_e.htm. |

| 27. |

Information on USDA's terms and fees under the GSM-102 program are at https://www.fas.usda.gov/programs/export-credit-gurantee-program-gsm-102/gsm-fee-schedule. |

| 28. |

70 Federal Register 222: 68589, November 18, 2014. |

| 29. |

The relationship between the OECD Arrangement and the SCM Agreement is established by Section (k) of Annex I to the SCM. See WTO, "Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures," http://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/analytic_index_e/subsidies_05_e.htm. |

| 30. |

Informa Economics IEG, Economic Impact of USDA Export Market Development Programs, report prepared for the U.S. Wheat Associates, the USA Poultry and Egg Export Council, and the Pear Bureau Northwest, July 2016, https://www.fas.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2016-10/2016econimpactsstudy.pdf. See also infographic summarizing the estimated economic effects based on this USDA-commissioned study (https://www.agexportscount.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/emd-3a-infographic.pdf). |

| 31. |

IHS Global Insight, "A Cost-Benefit Analysis of USDA's International Market Development Programs," March 2010, https://www.fas.usda.gov/sites/development/files/2013-09/market_development_eval-2010.pdf. See also testimony before the House Agriculture Committee, Subcommittee on Rural Development, Research, Biotechnology, and Foreign Agriculture, "Hearing to Review Market Promotion Programs and their Effectiveness on Expanding Exports of U.S. Agricultural Products," April 7, 2011. |

| 32. |

USDA, "2017 President's Budget Foreign Agricultural Service," p. 33-52, https://www.obpa.usda.gov/33fas2017notes.pdf. |

| 33. |

NASDA press release, "Putting Food Producers on the MAP in the Next Farm Bill," May 23, 2017. |

| 34. |

See footnote 30. In general, USDA estimates that each $1 billion in U.S. agricultural exports supports approximately 8,000 jobs throughout the economy and that each $1 of agricultural exports stimulated another $1.27 in business activity (based on 2015 data). Accordingly, USDA reports that U.S. agricultural exports supported nearly 1.1 million full-time American jobs, both on- and off-farm, and contributed to about $300 billion in total economic output in 2011. For more information, see USDA, "Effects of Trade on the U.S. Economy," 2015, https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/agricultural-trade-multipliers/effects-of-trade-on-the-us-economy-2015/. |

| 35. |

See, for example, Reimer et al., "Agricultural Export Promotion Programs Create Positive Economic Impacts." |

| 36. |

GAO, Agriculture Trade: USDA Is Monitoring Market Development Programs as Required but Could Improve Analysis of Impact, GAO-13-740, July 2013. |

| 37. |

Informa Economics IEG, Economic Impact of USDA Export Market Development Programs. |

| 38. |

Although MAP and FMDP overlap in both their form and their function, each program differs in terms of program focus and types of services provided, support for generic and branded product promotion, partner contribution requirements, and funding levels, among other differences (Table 1). See also Reimer et al., "Agricultural Export Promotion Programs Create Positive Economic Impacts." |

| 39. |

GAO, U.S. Agricultural Exports: Strong Growth Likely but Export Assistance Program's Contribution Uncertain, GAO-NSIAD-97-260, September 1997. |

| 40. |

GAO, U.S. Agricultural Exports: Agricultural Trade: Changes Made to Market Access Program, but Questions Remain on Economic Impact, GAO-NSIAD-99-38, April 1999. |

| 41. |

See, for example, GAO, U.S. Agricultural Exports: Strong Growth Likely but U.S. Export Assistance Programs' Contribution Uncertain, NSIAD-97-260. |

| 42. |

GAO, USDA: Improved Management Could Increase the Effectiveness of Export Promotion Activities, GAO/T-GGD-92-30, April 7, 1992; GAO, USDA: Improvements Needed in Foreign Agricultural Service Management, GAO/T-GGD-94-56, November 10, 1993; and GAO, International Trade: Agricultural Trade Offices' Role in Promoting U.S. Exports Is Unclear, NSIAD-92-65, January 16, 1992. |

| 43. |

GAO, High-Value Products and U.S. Export Promotion Efforts, GAO/T-GGD-92-64, July 28, 1992. |

| 44. |

USDA/OIG, Audit Report Foreign Agricultural Service Trade Promotion Operations, Report No. 07601-1-Hy, February 2007. |

| 45. |

Additional information is at http://www.usaedc.org/. |

| 46. |

Letters from the coalition to leadership of the Senate and House Subcommittees on Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies, Committee on Appropriations, June 23, 2017, and May 8, 2014, supporting full funding for MAP and FMDP. |

| 47. |

See, for example, letter to Senate Agriculture Committee leadership from a group of 140 organizations in opposition to S.Amdt. 1007 (S. 954, 113th Congress) that would reduce funding for MAP (May 2013). |

| 48. |

Letter to House Agriculture Committee leadership from the Coalition to Promote U.S. Agricultural Exports, August 31, 2017. |

| 49. |

NASDA press release, "Putting Food Producers on the MAP in the Next Farm Bill," May 23, 2017. |

| 50. |

Market failure refers to a situation in which the free market does not result in the efficient allocation of resources. It is widely recognized in the economic literature as typical of certain public goods. Economic theory also asserts that government intervention may be warranted in cases when the marginal social benefit of an action exceeds the marginal benefit to any one individual. |

| 51. |

See, for example: Reimer et al., "Agricultural Export Promotion Programs Create Positive Economic Impacts." |

| 52. |

J. P. Nichols, "Marketing by Design," Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, vol. 46, number 3 (August 2014). |

| 53. |

Reimer et al., "Agricultural Export Promotion Programs Create Positive Economic Impacts." |

| 54. |

NASDA, "Putting Food Producers on the MAP in the Next Farm Bill." |

| 55. |

See, for example: Senator Jeff Flake, "Wastebook: The Farce Awakens," pp. 55-57. See also Senator Flake's press release "#PorkChops: MAP Men," May 18, 2015; Senator James Lankford, "Federal Fumbles: 100 Ways the Government Dropped the Ball," 2015; Representative Steve Russell, "Waste Watch," September 2016; and Senator Tom Coburn, "Treasure Map: The Market Access Program's Bounty of Waste, Loot, and Spoils Plundered from Taxpayers," June 2012. |

| 56. |

USDA, "2018 President's Budget, Foreign Agricultural Service," p. 33-5; and USDA, "USDA: FY2018 Budget Summary," pp. 32, 96, https://www.obpa.usda.gov/budsum/fy18budsum.pdf. |

| 57. |

Heritage Foundation, Budget Book, "Eliminate the Market Access Program," #50. See also Heritage Foundation, "Addressing Waste, Abuse, and Extremism in USDA Programs," May 30, 2014. |

| 58. |

Citizens Against Government Waste, "Prime Cuts," June 2015. |

| 59. |

Taxpayers for Common Sense, "U.S. Department of Agriculture's Market Access Program," May 2013. |

| 60. |

Statement by B. Arnold, NTU, at a House of Representatives hearing ("Waste in Government: What's Being Done?") before the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, January 9, 2014. See also NTU press release and letter to the U.S. Senate, June 4, 2013, urging support for a series of amendments, including S.Amdt. 1007, which would reduce MAP funding, to the Senate farm bill, S. 954. |

| 61. |

U.S. Senate Democrats, "Objections to Additional Pending Amendments to S. 954, the Farm Bill," June 4, 2013. |

| 62. |

GAO, USDA Is Monitoring Market Development Programs as Required but Could Improve Analysis of Impact, GAO-13-740, July 2013. GAO reported that support for branded products was provided to more than 600 small companies and seven agricultural cooperatives. |

| 63. |

Not discussed here are programs administered by other federal agencies, such as the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, which also provides loan guarantees and risk insurance for overseas investments by qualifying U.S. private investors. For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10659, Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC). |

| 64. |

This section was written by Shayerah Ilias Akhtar. |

| 65. |

12 U.S.C. §635 et seq. Despite being authorized through FY2019, Ex-Im Bank is currently not fully operational because its Board of Directors lacks a quorum and cannot approve medium- and long-term transactions over $10 million. See CRS In Focus IF00021, Export-Import Bank (Ex-Im Bank) Reauthorization (available to congressional clients from the author). |

| 66. |

U.S. Department of Commerce, Trade Finance Guide, "Agricultural Export Financing" section. |

| 67. |

12 U.S.C. §635(8)(b). |

| 68. |

USDA's agricultural export guarantees are issued by the CCC. |

| 69. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Financial Services, Subcommittee on Domestic and International Monetary Policy, Trade, and Technology, Oversight of the Export-Import Bank of the United States, Ex-Im Bank 2003 Advisory Committee Recommendations to the Board of Directors (submitted for the record), 108th Cong., 2nd sess., May 6, 2004, Serial No. 108-84, p. 119. |

| 70. |

Ex-Im Bank, "Key Industries." Typically, short-term finance programs have repayment terms of less than two years, medium-term finance programs have repayment terms of between two to seven years, and long-term finance programs have repayment terms over seven years. See Ex-Im Bank, Report to the U.S. Congress on Global Export Credit Competition, for the period January 1, 2016, through December 31, 2016 (June 2017). |

| 71. |

Based on comparisons in U.S. Congress, House Committee on Financial Services, Subcommittee on Domestic and International Monetary Policy, Trade, and Technology, Oversight of the Export-Import Bank of the United States, May 6, 2004, p. 119. |

| 72. |

Obama White House, "Detailed Information on the Agricultural Export Credit Guarantees Program Assessment," https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/omb/expectmore///detail/10002020.2004.html. |

| 73. |

The agricultural export support share was also low in FY2014, the last year in which Ex-Im Bank was fully operational. That year, Ex-Im Bank authorized $501 million (out of $20.5 billion) to support $1.2 billion of U.S. exports (out of $27.5 billion in total U.S. exports estimated to be supported by Ex-Im Bank). |

| 74. |

USDA, "GSM-102, FY2016 Year Activity Report" and "FY2017 GSM-102 Allocations, as of September 22, 2017." |

| 75. |

For more detailed information on specific similarities and differences between the agricultural programs of Ex-Im Bank and USDA, please contact the author to receive a Congressional Distribution memo dated September 27, 2017. |

| 76. |

Department of Commerce, Trade Finance Guide, "Agricultural Export Financing." |

| 77. |

This section was written by Sean Lowry. |

| 78. |

For information, see CRS Report R43155, Small Business Administration Trade and Export Promotion Programs. |

| 79. |

See CRS Report R40860, Small Business Size Standards: A Historical Analysis of Contemporary Issues. |

| 80. |

For a comparison of key features of SBA's business loan programs, see SBA, "Loan Program Quick Reference Guide," https://www.sba.gov/content/loan-program-quick-reference-guide. |

| 81. |

SBA, FY2018 Congressional Budget Justification and FY2016 Annual Performance Report, May 22, 2017, pp. 62-63. These guarantees could have been approved under the three trade-related variations of its general business loan guarantee programs or through non-export related variations of these programs. |

| 82. |

SBA, "SBA Announces FY 2017 State Trade Expansion Program (STEP) Awards," September 14, 2017. |