BUILD Act: Frequently Asked Questions About the New U.S. International Development Finance Corporation

Members of Congress and Administrations have periodically considered reorganizing the federal government’s trade and development functions to advance various U.S. policy objectives. The Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development Act of 2018 (BUILD Act), which was signed into law on October 5, 2018 (P.L. 115-254), represents a potentially major overhaul of U.S. development finance efforts. It establishes a new agency—the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (IDFC)—by consolidating and expanding existing U.S. government development finance functions, which are conducted primarily by the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) and some components of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).

While the IDFC is expected to carry over OPIC’s authorities and many of its policies, there are some key distinctions. For example, in comparison to OPIC, the new IDFC, by statute, is to have the following:

More “tools” to provide investment support (e.g., authority to make limited equity investments and provide technical assistance).

More capacity (a $60 billion exposure cap compared to OPIC’s $29 billion exposure cap).

A longer authorization period (seven years compared to OPIC’s year-to-year authorization through appropriations legislation in recent years).

More specific oversight and risk management (including its own Inspector General [IG], compared to OPIC, which is under the USAID IG’s jurisdiction).

A key policy rationale for the BUILD Act was to respond to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and China’s growing economic influence in developing countries. In this regard, the IDFC aims to advance U.S. influence in developing countries by incentivizing private investment as an alternative to a state-directed investment model. The BUILD Act also aims to increase the effectiveness and efficiency of U.S. government development finance functions, as well as to achieve greater cost savings through consolidation.

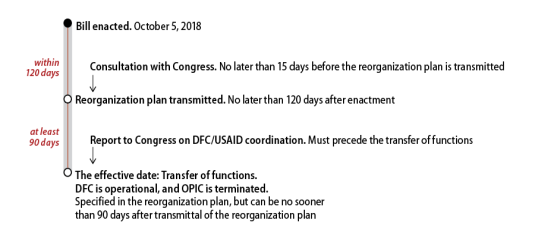

The BUILD Act requires the Administration to submit to Congress a reorganization plan within 120 days of enactment of the act, and the IDFC is not permitted to become operational any sooner than 90 days after the President has transmitted the reorganization plan.

The 116th Congress will have responsibility for overseeing the Administration’s implementation of the BUILD Act. As the IDFC is operationalized, Members of Congress may examine whether the current statutory framework allows the IDFC to balance both its mandates to support U.S. businesses in competing for overseas investment opportunities and to support development, as well as whether it enables the IDFC to respond effectively to strategic concerns especially vis-à-vis China. Congress also may consider whether to press the Administration to pursue international rules on development finance comparable to those that govern export credit financing. More broadly, the IDFC’s establishment could renew legislative debate over the economic and policy benefits and costs of U.S. government activity to support private investment, and whether such activity is an effective way to promote broad U.S. foreign policy objectives.

BUILD Act: Frequently Asked Questions About the New U.S. International Development Finance Corporation

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Background

- What is the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (IDFC)?

- What existing agency functions are consolidated?

- What is development finance?

- What are development finance institutions (DFIs)?

- How does development finance relate to foreign assistance?

- How does the IDFC aim to respond to China's growing economic influence in developing countries?

- BUILD Act Formulation and Debate

- What is the BUILD Act's legislative history?

- What is the Trump Administration's development finance policy approach?

- What was the policy debate over the BUILD Act?

- IDFC Organizational Structure and Management

- What are the congressional committees of jurisdiction?

- What is the IDFC's mission?

- How will the IDFC be managed?

- What will be the responsibilities of the officers?

- Will the IDFC have any advisory support?

- What oversight structures will the IDFC have?

- IDFC Operations

- For what purposes can the IDFC use its authorities?

- What financial authorities and tools will the IDFC have?

- Will the IDFC's activities have U.S. government backing?

- Will the IDFC have an exposure limit?

- How will the IDFC be funded?

- How are losses to be repaid?

- For how long is the IDFC authorized?

- Statutory Parameters for IDFC Project Support

- Will there be terms and conditions of IDFC support?

- In which countries can the IDFC operate?

- What considerations will factor into the IDFC's decision to support projects?

- What limitations will there be on the IDFC's support?

- What requirements will the IDFC have to avoid market distortion?

- Monitoring and Transparency

- What performance measures and evaluation will the IDFC have?

- What are the IDFC's reporting and notification requirements?

- What information must it make to the public?

- Implementation

- How and when is the IDFC expected to become operational?

- How will the IDFC relate to other U.S. trade and investment promotion efforts?

- Issues for the 116th Congress

Figures

Summary

Members of Congress and Administrations have periodically considered reorganizing the federal government's trade and development functions to advance various U.S. policy objectives. The Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development Act of 2018 (BUILD Act), which was signed into law on October 5, 2018 (P.L. 115-254), represents a potentially major overhaul of U.S. development finance efforts. It establishes a new agency—the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (IDFC)—by consolidating and expanding existing U.S. government development finance functions, which are conducted primarily by the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) and some components of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID).

While the IDFC is expected to carry over OPIC's authorities and many of its policies, there are some key distinctions. For example, in comparison to OPIC, the new IDFC, by statute, is to have the following:

- More "tools" to provide investment support (e.g., authority to make limited equity investments and provide technical assistance).

- More capacity (a $60 billion exposure cap compared to OPIC's $29 billion exposure cap).

- A longer authorization period (seven years compared to OPIC's year-to-year authorization through appropriations legislation in recent years).

- More specific oversight and risk management (including its own Inspector General [IG], compared to OPIC, which is under the USAID IG's jurisdiction).

A key policy rationale for the BUILD Act was to respond to China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and China's growing economic influence in developing countries. In this regard, the IDFC aims to advance U.S. influence in developing countries by incentivizing private investment as an alternative to a state-directed investment model. The BUILD Act also aims to increase the effectiveness and efficiency of U.S. government development finance functions, as well as to achieve greater cost savings through consolidation.

The BUILD Act requires the Administration to submit to Congress a reorganization plan within 120 days of enactment of the act, and the IDFC is not permitted to become operational any sooner than 90 days after the President has transmitted the reorganization plan.

The 116th Congress will have responsibility for overseeing the Administration's implementation of the BUILD Act. As the IDFC is operationalized, Members of Congress may examine whether the current statutory framework allows the IDFC to balance both its mandates to support U.S. businesses in competing for overseas investment opportunities and to support development, as well as whether it enables the IDFC to respond effectively to strategic concerns especially vis-à-vis China. Congress also may consider whether to press the Administration to pursue international rules on development finance comparable to those that govern export credit financing. More broadly, the IDFC's establishment could renew legislative debate over the economic and policy benefits and costs of U.S. government activity to support private investment, and whether such activity is an effective way to promote broad U.S. foreign policy objectives.

Background

What is the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (IDFC)?

The IDFC is authorized by statute to be a "wholly owned Government corporation ... under the foreign policy guidance of the Secretary of State" in the executive branch. Its purpose is to "mobilize and facilitate the participation of private sector capital and skills in the economic development" of developing and transition countries, in order to complement U.S. development assistance objectives and foreign policy interests (§1412).1 In other words, the IDFC's mission is to promote private investment in support of both U.S. global development goals and U.S. economic interests. Not yet operational, the IDFC represents a potentially major overhaul of U.S. development finance efforts.

The IDFC's enabling legislation is the Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development Act of 2018 (BUILD Act), which was enacted on October 5, 2018, as Division F of a law to reauthorize the (unrelated) Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) (H.R. 302/P.L. 115-254).2 Under the BUILD Act, the IDFC is to consolidate and expand the U.S. government's existing development finance functions—currently conducted primarily by the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). By statute, the IDFC is a successor agency to OPIC, which is to terminate when the IDFC is operational.

What existing agency functions are consolidated?

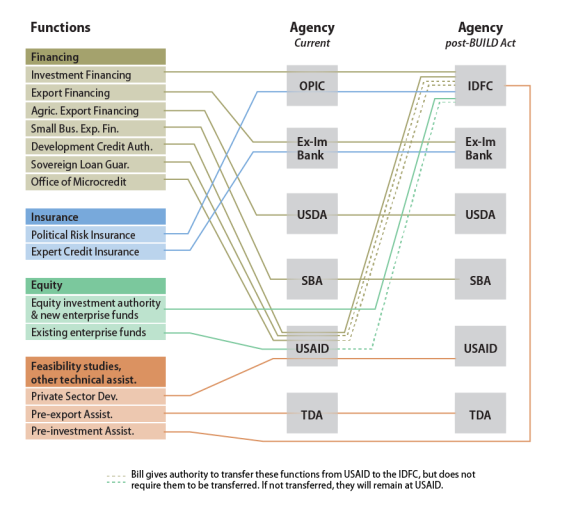

The BUILD Act consolidates functions currently carried out primarily by OPIC and certain elements of USAID (see Appendix).

The act established the new IDFC to be a successor entity to OPIC, taking over all of its functions and authorities and adding new ones. The IDFC's authorities would expand beyond OPIC's existing authorities to make loans and guarantees and issue insurance or reinsurance. They would also include the authority to take minority equity positions in investments, subject to limitations. In addition, unlike OPIC, the IDFC would be able to issue loans in local currency.

The extent to which USAID functions will be transferred to the new IDFC is less clear. The act specifies that the Development Credit Authority (DCA), the existing legacy credit portfolio under the Urban and Environment Credit Program, and any other direct loan programs and non-DCA guarantee programs shall be transferred to the IDFC. It also provides the authority for, but does not require, the transfer of USAID's Office of Private Capital and Microenterprise, the existing USAID-managed enterprise funds (it gives the IDFC authority to establish new funds), and the sovereign loan guarantee portfolio. The disposition of these functions is to be detailed in the reorganization plan that the Administration must submit to Congress within 120 days of enactment. The reorganization plan is expected to be submitted by early February 2019.

In addition, the IDFC would have the authority to conduct feasibility studies on proposed investment projects (with cost sharing) and provide technical assistance.

What is development finance?

"Development finance" is a term commonly used to describe government-backed financing to support private sector capital investments in developing and emerging economies. It can be viewed on a continuum of public and private support, situated between pure government support through grants and concessional loans and pure commercial financing at market-rate terms.

Development finance generally is targeted toward promoting economic development by supporting foreign direct investment (FDI) in underserved types of projects, regions, and countries; undercapitalized sectors; and countries with viable project environments but low credit ratings. Such support is aimed to increase private sector activity and public-private partnerships that would not happen otherwise in the absence of development finance support because of the actual or perceived risk associated with the activity. Tools of development finance may include equity (raising capital through the sale of ownership shares), direct loans, loan guarantees, political risk insurance, and technical assistance.

Development financing is particularly important for infrastructure funding, where annual global investment in transportation, power, water, and telecommunications systems falls, by one account, almost $800 million short of the estimated $3.3 trillion required to keep pace with projected economic growth. The largest infrastructure investment gaps are in the road and electricity sectors in developing and emerging economies.3

What are development finance institutions (DFIs)?

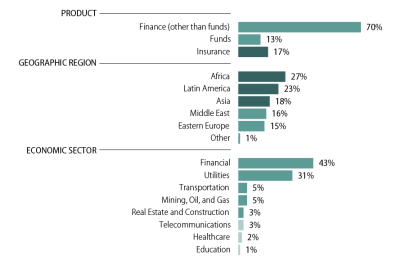

DFIs are specialized entities that supply development finance, generally aiming to be catalytic agents in promoting private sector investment in developing countries. In the United States, OPIC has been the primary DFI since the 1970s.4 In FY2017, OPIC reported authorizing $3.8 billion in new commitments for 112 projects, and its exposure reached a record high of $23.2 billion (see Figure 1). OPIC estimated that it helped mobilize $6.8 billion in capital and supported 13,000 new jobs in host countries that year. Sub-Saharan Africa represents the largest share of OPIC's portfolio by region. OPIC has committed $2.4 billion in financing and political risk insurance for Power Africa−a major public-private partnership coordinated by USAID−to date, including committing $12.4 million for a loan to support construction of a hydropower plant in Uganda in FY2017. Among other focus areas, OPIC currently has $5 billion invested in the Indo-Pacific in projects to expand access to energy, education, and financial services, as well as to support local farmers. On July 30, 2018, OPIC, the Japanese Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC, Japan's counterpart to OPIC), and the Australian government announced a trilateral partnership to mobilize investments in infrastructure projects in the Indo-Pacific region to support development, connectivity, and economic growth in the region.5

Other agencies, such as the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), also provide development finance. The IDFC is to take on the DFI mantle for the United States under the BUILD Act.

|

|

Source: CRS, based on data from OPIC's FY2018 congressional budget justification (CBJ). Notes: Based on OPIC's portfolio of $22.5 billion on March 31, 2017. The CBJ did not specify the date of exposure used for the portfolio breakdown by region and sector. Finance involves OPIC support through direct loans and loan guarantees. Funds are a specific type of finance that combines OPIC debt with private equity from a private source. |

At the bilateral level, national governments can operate DFIs. The United Kingdom was the first country to establish a DFI in 1948. Many countries have followed suit. In the United States, OPIC began operations in 1971, but the U.S. government's role in overseas investment financing predates OPIC's formal establishment.

Bilateral DFIs are typically wholly or majority government-owned. They operate either as independent institutions or as a part of larger development banks or institutions. Their organizational structures have evolved, in some cases, due to changing perceptions of how to address identified development needs in the most effective way possible. Unlike OPIC, other bilateral DFIs tend to be permanent and not subject to renewals by their countries' legislatures.

DFIs also can operate multilaterally, as parts of international financial institutions (IFIs), such as the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private-sector arm of the World Bank. They can operate regionally through regional development banks as well. Examples of these banks include the African Development Bank (AfDB), the Asian Development Bank (AsDB), the European Bank for Reconstruction & Development (EBRD), and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB).6

DFIs vary in their specific objectives, management structures, authorities, and activities.

How does development finance relate to foreign assistance?

Historically, official development assistance (ODA) has been a primary way that the United States and other developed countries have provided support for infrastructure projects in developing countries.7 However, foreign aid for infrastructure has declined over decades while the growth of direct private investment flows has outpaced ODA, making development finance an increasingly prominent way to encourage private investment in undercapitalized areas. Private investors face challenges investing in developing countries due to political risk, exchange rate risk, and weaknesses in legal, regulatory, and institutional environments, among other things. In such cases, government support, whether through equity, financing, or political risk insurance, may provide needed liquidity or assurances to catalyze private investment.

How does the IDFC aim to respond to China's growing economic influence in developing countries?

While it does not mention China by name, the BUILD Act alludes to concerns with state-directed investments, such as China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which launched in 2013. The act states that it is U.S. policy to "facilitate market-based private sector development and inclusive economic growth in less developed countries" through financing, including

to provide countries a robust alternative to state-directed investments by authoritarian governments and [U.S.] strategic competitors using best practices with respect to transparency and environmental and social safeguards, and which take into account the debt sustainability of partner countries (§1411).

Supporters view the IDFC as a central part of the U.S. response to China's growing economic influence in developing countries, exemplified by the BRI—which could provide, by some estimates, anywhere from $1 trillion to $8 trillion in Chinese investments and development financing for infrastructure projects in developing countries (see text box). The Administration and many Members of Congress have been critical of China's financing model, which they find to lack transparency, operate under inadequate environmental and social safeguards for projects, and employ questionable lending practices that may lead to unsustainable debt burdens in some poorer countries (so-called "debt diplomacy"). Under this view, the IDFC (when operational) may help the United States compete more effectively or strategically with China. While even a strengthened OPIC may not be able to compete "dollar-for-dollar" with China's DFI activity, supporters argue that the United States "can and should do more to support international economic development with partners who have embraced the private sector-driven development model."8 Others, however, argued that the act could have tightened the IDFC's focus with respect to China, for instance, by requiring the IDFC to have a specific focus on countering China's investment and economic influence; from this perspective, the failure to narrow the IDFC's scope makes it likely that the new entity may support projects of limited U.S. foreign policy and strategic interest—a concern that some critics have levied against OPIC.9

|

China's DFIs and Development Finance Activity China's primary DFIs are the state-owned China Development Bank (CDB) and the recently established multilateral Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and New Development Bank (NDB), also known as the BRICS development bank.10 Data on China's development finance activities are limited and estimates vary widely. China's development finance activities have been prominent in their linkages to major Chinese national efforts, notably the BRI.11 CDB reportedly has provided support for 100 BRI projects valued at $30 billion.12 Much of China's support for development is directed toward infrastructure and energy projects and involves Chinese firms, including state-owned enterprises (SOEs). China's development finance activity in Asia, Africa, and Latin America has been a focal point for development finance watchers, but its range is broader, particularly in light of the BRI. Some recipient governments may welcome that Chinese support is not as conditional as that of other DFIs on environmental and social requirements, but such projects also raise questions about such risks as displacement of large local populations due to a lack of safeguards.13 Many of the countries in which China invests also have high debt-to-GDP ratios, raising questions about debt sustainability.14 |

BUILD Act Formulation and Debate

What is the BUILD Act's legislative history?15

In February 2018, two proposed versions of the BUILD Act, H.R. 5105 in the House and S. 2463 in the Senate, were introduced to create a new U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (IDFC). Both bills proposed consolidating all of OPIC's functions and certain elements of USAID—including the Development Credit Authority (DCA), Office of Private Capital and Microenterprise, and enterprise funds. A major difference between the two bills, as introduced, was that H.R. 5105 would have authorized the IDFC for seven years, while S. 2463 would have authorized it for two decades, until September 30, 2038. The House-passed version (July 17, 2018; H.Rept. 115-814) and Senate committee-reported version (June 27, 2018) bridged some differences, including both providing a seven-year authorization.

On September 26, 2018, the House adopted a resolution (H.Res. 1082) to pass the BUILD Act as part of the Federal Aviation Administration Reauthorization Act of 2018 (FAA Reauthorization Act; H.R. 302). The Senate followed with its passage of the BUILD Act as part of the FAA Reauthorization Act on October 3, 2018. On October 5, 2018, the President signed into law the FAA Reauthorization Act, with the BUILD Act in Division F.

What is the Trump Administration's development finance policy approach?

Although the President's FY2018 budget request called for eliminating OPIC's funding as part of its critical view of U.S. government agencies with international development orientations,16 the Administration ultimately pursued development finance reform through OPIC as an opportunity to respond to China's growing economic influence in developing countries. The Trump Administration included development finance consolidation in its FY2019 budget request and subsequent set of government-wide reorganization proposals.17 The Administration supported the BUILD Act bills introduced in Congress (H.R. 5105, S. 2320), viewing them as broadly consistent with its goals, while calling for some modifications.18 It later said that amendments to the BUILD Act fulfilled the Administration's goals, including to "align U.S. government development finance with broader foreign policy and development goals, enhancing the competitiveness and compatibility of the U.S. development finance toolkit."19

|

Administration Statements President Trump's remarks at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) CEO Summit (November 2017). "[The United States is] committed to reforming our development finance institutions so that they better incentivize private sector investment in your economies and provide strong alternatives to state-directed initiatives that come with many strings attached."20 National Security Strategy (December 2017). Identified modernizing U.S. development finance tools as a priority to advance U.S. global influence. It noted that, "[w]ith these changes, the United States will not be left behind as other states use investment and project finance to extend their influence."21 |

What was the policy debate over the BUILD Act?

The BUILD Act follows long-standing debate among policymakers over whether or not government financing of private-sector activity is appropriate. Supporters argued that OPIC helps fill in gaps in private-sector support that arise from market failures and helps U.S. firms compete against foreign firms backed by foreign DFIs for investment opportunities—thereby advancing U.S. foreign policy, national security, and economic interests. Various civil society stakeholders have proposed consolidating the development finance functions of OPIC and other agencies into a new DFI in order to boost OPIC and make U.S. development finance efforts more competitive with those of foreign countries.22 Opponents held that OPIC diverts capital away from efficient uses and crowds out private alternatives, criticized OPIC for assuming risks unwanted by the private sector, and questioned the development benefits of its programs. They have called for terminating OPIC's functions or privatizing them.23

While the BUILD Act garnered overall support, specific aspects of it were subject to debate. Some development advocates expressed concern that the BUILD Act's transfer of DCA and other credit program authority from USAID to the IDFC may sever the close link between these funding mechanisms and the USAID development programs into which they have been embedded, potentially making the tools less effective and less development-oriented. Others saw potential for the DCA to become a more robust financing option for USAID programs under the new IDFC, with its expanded authorities. In response to these concerns, the BUILD Act includes many provisions, discussed later in this report, to promote coordination and linkages between USAID and the IDFC, and to emphasize the development mission of the IDFC. Some in the development community also questioned whether the new DFI would have a sufficiently strong development mandate, as well as raised concerns about the transparency, environmental, and social standards of the new DFI relative to OPIC.24 Some critics of OPIC supported strengthening statutorily the aim of the IDFC in specifically countering China's influence in the developing countries.25 Other possible policy alternatives include focusing on enhancing coordination of development finance functions among agencies or supporting development goals through multilateral and regional DFIs in which the United States plays a major leadership role.

IDFC Organizational Structure and Management

While the IDFC authorized by the BUILD Act has yet to be established, and some implementation questions remain, the act detailed many aspects of how the new entity should be structured, managed, and overseen by Congress. This section discusses the BUILD Act provisions that describe how the new IDFC is expected to function once established.

What are the congressional committees of jurisdiction?

The BUILD Act defines "appropriate congressional committees" as the Senate Foreign Relations and Appropriations committees and the House Foreign Affairs and Appropriations committees (§1402(1)). It imposes a number of reporting and notification requirements on the IDFC with respect to these congressional committees. These committees have typically been the same ones in which legislation related to OPIC and USAID is introduced.

What is the IDFC's mission?

The BUILD Act establishes the IDFC for the stated purpose of mobilizing private-sector capital and skills for the economic benefit of less-developed countries, as well as countries in transition from nonmarket to market economies, in support of U.S. development assistance and other foreign policy objectives (§1412(b)). This is very similar to the mission of OPIC, as described in the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended.

The legislation includes several provisions intended to ensure that the corporation remains focused on this development mission. The act directs the IDFC to prioritize support to countries with low-income or lower-middle-income economies, establishes a position of Chief Development Officer on the board, and requires that a performance measurement system be developed that includes, among other things, standards and methods for ensuring the development performance of the corporation's portfolio. The annual report required by the BUILD Act also must include an analysis of the desired development outcomes for IDFC-supported projects and the extent to which the corporation is meeting associated development metrics, goals, and objectives.

How will the IDFC be managed?

The BUILD Act establishes a Board of Directors ("Board"), a Chief Executive Officer (CEO), a Deputy Chief Executive Officer (Deputy CEO), a Chief Risk Officer, a Chief Development Officer, and any other officers as the Board may determine, to manage the IDFC (§1413(a)).

The BUILD Act vests all powers of the IDFC in the nine-member Board of Directors (§1413(b)). By statute, the Board is composed of

- a Chief Executive Officer;

- four U.S. government officials—the Secretary of State, USAID Administrator, Secretary of the Treasury, and Secretary of Commerce (or their designees); and

- four nongovernment members appointed by the President of the United States by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, with "relevant experience" to carry out the IDFC's purpose, which "may include experience relating to the private sector, the environment, labor organizations, or international development." These members have three-year terms, can be reappointed for one additional term, and serve until their successors are appointed and confirmed.

The Board's Chairperson is the Secretary of State and the Vice Chairperson is the USAID Administrator (or their designees).

The Board differs in size and potentially composition from that of OPIC's Board. By statute, OPIC's 15-member Board of Directors is composed of eight "private sector" Directors, with specific requirements for representation of small business, labor, and cooperatives interests, and seven "federal government" Directors (including the OPIC President, USAID Administrator, U.S. Trade Representative, and a Labor Department officer). The President of the United States appoints the Board Chairman and Vice Chairman from among the members of the Board.

Five members of the Board constitutes a quorum for the transaction of business. The Board is required to hold at least two public hearings each year to allow for stakeholder input.

What will be the responsibilities of the officers?

The BUILD Act establishes four officers for IDFC management. A Chief Executive Officer, who is under the Board's direct authority, is responsible for the IDFC's management and exercising powers and duties as the Board directs (§1413(d)). The BUILD Act also establishes a Deputy Chief Executive Officer (§1413(e)). The Chief Executive Officer and Deputy Chief Executive Officer are appointed by the President of the United States, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, and serve at the pleasure of the President.

The act outlines the positions of the Chief Risk Officer and Chief Development Officer in more detail. Both officers are to be appointed by the CEO, subject to Board approval, from among individuals with senior-level experience in financial risk management and development, respectively. They each are to report directly to the Board and are removable only by a majority Board vote. The Chief Risk Officer, in coordination with the Audit Committee established by the act, is responsible for developing, implementing, and managing a comprehensive process for identifying, assessing, monitoring, and limiting risks to the IDFC (§1413(f)). The Chief Development Officer's responsibilities include coordinating the IDFC's development policies and implementation efforts with USAID, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), and other relevant U.S. government departments and agencies; managing IDFC employees dedicated to working on transactions and projects codesigned with USAID and other relevant U.S. government entities; and authorizing and coordinating interagency transfers of funds and resources to support the IDFC (§1413(g)). OPIC's enabling legislation does not include either a specific Chief Risk Officer or Chief Development Officer.

Will the IDFC have any advisory support?

The BUILD Act establishes a Development Advisory Council to advise the Board on the IDFC's development objectives (§1413(i)). By statute, its members are Board-appointed on the recommendation of the CEO and Chief Development Officer, and composed of no more than nine members "broadly representative" of NGOs and other international development-related institutions. Its functions are to advise the Board on the extent to which the IDFC is meeting its development mandate and any suggestions for improvements.

What oversight structures will the IDFC have?

The BUILD Act establishes several oversight structures to govern the agency overall and particular aspects.

Unlike OPIC, which is overseen by the USAID Inspector General, the IDFC is to have its own Inspector General (IG) (§1414) to conduct reviews, investigations, and inspections of its operations and activities. In addition, the act requires the Board to establish a "transparent and independent accountability mechanism" to annually evaluate and report to the Board and Congress regarding statutory compliance with environmental, social, labor, human rights, and transparency standards; provide a forum for resolving concerns regarding the impacts of specific IDFC-supported projects with respect to such standards; and provide advice regarding IDFC projects, policies, and practices (§1415).

The BUILD Act also requires the IDFC to establish a Risk Committee and Audit Committee to ensure monitoring and oversight of the IDFC's investment strategies and finances (§1441). Both committees are under the direction of the Board. The Risk Committee is responsible for overseeing the formulation of the IDFC's risk governance structure and risk profile (e.g., strategic, reputational, regulatory, operational, developmental, environmental, social, and financial risks) (§1441(b)), while the Audit Committee is responsible for overseeing the IDFC's financial performance management structure, including the integrity of its internal controls and financial statements, the performance of internal audits, and compliance with legal and regulatory finance-related requirements (§1444(c)).

IDFC Operations

For what purposes can the IDFC use its authorities?

In general, the IDFC's authorities are limited to (§1421(a))

- carrying out U.S. policy and the IDFC's purpose, as outlined in the statute;

- mitigating risks to U.S. taxpayers by sharing risks with the private sector and qualifying sovereign entities through cofinancing and structuring of tools; and

- ensuring that support provided is "additional" to private-sector resources by mobilizing private capital that would otherwise not be deployed without such support.

The emphasis on additionality reflects OPIC's current policy, but is not explicitly in OPIC's enabling legislation. Policymakers have debated whether OPIC supports or crowds out private-sector activity.

What financial authorities and tools will the IDFC have?

Under the BUILD Act, the IDFC's authorities would expand beyond OPIC's existing authorities to make loans and guarantees and issue insurance or reinsurance (see Table 1). They would also include the authority to take minority equity positions in investments. USAID-drawn authorities include technical assistance and the establishment of enterprise funds. In addition, the IDFC would have the authority to conduct feasibility studies on proposed investment projects (with cost-sharing) and provide technical assistance. A chart depicting the current development finance functions of relevant U.S. agencies, as well as how those functions may be shifted by the BUILD Act, is in the Appendix.

The IDFC's functions are discussed below.

|

Function |

IDFC |

OPIC |

USAID |

|

Loans |

|||

|

Guarantees |

|||

|

Equity investments |

X* |

X |

|

|

Insurance |

X |

||

|

Reinsurance |

X |

||

|

Feasibility studies |

X |

||

|

Technical assistance |

X** |

||

|

Enterprise funds |

X |

Source: BUILD Act, FAA, agency documents.

Notes: *Pilot equity authority but no funding. **In limited circumstances; not routine part of OPIC support. Terms and conditions may differ across IDFC, OPIC, and USAID, such as on the ability to extend financing in U.S. and/or foreign currency.

Loan and Guarantees. The IDFC is authorized to make loans or guarantees upon the terms and conditions that it determines (§1421(b)). Loans and guarantees are subject to the Federal Credit Reform Act of 1990 (FCRA).26

IDFC financing may be denominated and repayable in either U.S. dollars or foreign currencies, the latter only in cases where the Board determines there is a "substantive policy rationale." This is distinct from OPIC, which is limited to making loans in U.S. currency.

Equity Investments. The BUILD Act authorizes the IDFC to take equity stakes in private investments (§1421(c)). The IDFC can support projects as a minority investor acquiring equity or quasiequity stake of any entity, including as a limited partner or other investor in investment funds, upon such terms and conditions as the IDFC may determine. Loans and guarantees may be denominated and repayable in either U.S. dollars or foreign currencies, the latter only in cases where the Board determines there is a "substantive policy rationale." The IDFC is required to develop guidelines and criteria to require that the use of equity authority has a clearly defined development and foreign policy purpose, taking into account certain factors.

The BUILD Act places limitations on equity investment, both in terms of the specific project and the overall support. The total amount of support with respect to any project cannot exceed 30% of the total amount of all equity investment made to that project at the time the IDFC approves support. Furthermore, equity support is limited to no more than 35% of the IDFC's total exposure. The BUILD Act directs the IDFC to sell and liquidate its equity investment support as soon as commercially feasible commensurate with other similar investors in the project, taking into account national security interests of the United States.

The addition of equity authority is potentially significant. OPIC does not have the capacity to make equity investments; it can only provide debt financing as a senior lender, meaning it is repaid first in the event of a loss. Foreign DFIs often have been reluctant to partner with OPIC because they would prefer to be on an equal footing. Potential expansion of OPIC's equity authority capability has met resistance from some Members of Congress in the past, based on discomfort with the notion of the U.S. government acquiring ownership stakes in private investments, among other concerns.

Insurance and reinsurance. The IDFC may issue insurance or reinsurance to private-sector entities and qualifying sovereign entities assuring protection of their investments in whole or in part against political risks (§1421(d)). Examples include currency inconvertibility and transfer restrictions, expropriation, war, terrorism, civil disturbance, breach of contract, or non-honoring of financial obligations.

Investment promotion. The IDFC is authorized to initiate and support feasibility studies for planning, developing, and managing of and procurement for potential bilateral and multilateral development projects eligible for support (§1421(e)). This includes training on how to identify, assess, survey, and promote private investment opportunities. The BUILD Act directs the IDFC, to the maximum extent practicable, to require cost-sharing by those receiving funds for investment promotion.

Special projects and programs. The IDFC is authorized to administer and manage special projects and programs to support specific transactions, including financial and advisory support programs that provide private technical, professional, or managerial assistance in the development of human resources, skills, technology, capital savings, or intermediate financial and investment institutions or cooperatives (§1421(f)). This includes the initiation of incentives, grants, or studies for the energy sector, women's economic empowerment, microenterprise households, or other small business activities.

Enterprise funds. The BUILD Act authorizes but does not require the transfer of existing USAID enterprise funds to the IDFC (§1421(g)). Existing Europe/Eurasia enterprise funds are winding down. The two newer funds, in Tunisia and Egypt, remain primarily funded by U.S. government grant funds and are private sector-managed, arguably requiring close USAID oversight and an in-country presence to ensure the funds fulfill a development, rather than a purely for-profit, mission. As such, their removal to an agency without either feature may make this model less effective as a development instrument. The BUILD Act also gives the IDFC authority to establish new enterprise funds. It has been argued, however, that the IDFC's authority to conduct equity investment would make enterprise funds unnecessary.

Will the IDFC's activities have U.S. government backing?

All of the IDFC's authorities, like prior support by OPIC and USAID components, are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. In other words, the full faith and credit of the U.S. government is pledged for full payment and performance of obligations under these authorities (§1434(e)).

Will the IDFC have an exposure limit?

The maximum contingent liability (overall portfolio) that the IDFC can have outstanding at any one time cannot exceed $60 billion (§1433). This is more than double OPIC's current exposure limit—$29 billion. In recent years, OPIC support has reached record highs—totaling $23.2 billion in FY2017. While the IDFC's exposure cap is small compared to the potentially trillions of dollars that China is pouring into development efforts like the BRI, supporters argue that the IDFC could catalyze other private investment to developing countries through the U.S. development finance model.

How will the IDFC be funded?

According to the BUILD Act, the IDFC will be funded through a Corporate Capital Account comprised of fees for services, interest earnings, returns on investments, and transfers of unexpended balances from predecessor agencies (§1434). Annual appropriations legislation will designate a portion of these funds that may be retained for operating and program expenses, while the rest will revert to the Treasury, much like the current OPIC funding process. Like OPIC, the new IDFC is expected to be self-sustaining, meaning that anticipated collections are expected to exceed expenses, resulting in a net gain to the Treasury. The act also authorizes transfers of funds appropriated to USAID and the State Department to the IDFC. This authority will allow USAID missions and bureaus to continue to fund DCA activities related to their projects through transfers, as they now do through transfers to the DCA office within USAID.

The BUILD Act does not authorize annual appropriations levels for administrative and program expenses for the new IDFC, and it is unclear how future appropriations provisions for the IDFC will compare to current OPIC and DCA provisions. In FY2018, appropriators made $79.2 million of OPIC revenue available for OPIC's administrative expenses and $20 million available for loans and loan guarantees. DCA was appropriated $10 million for administrative expenses and authorized to use up to $55 million transferred from foreign assistance accounts managed by USAID to support loan guarantees.

How are losses to be repaid?

In general, if the IDFC determines that the holder of a loan guaranteed by the IDFC suffers a loss as a result of default by the loan borrower, the IDFC shall pay to the holder the percentage of loss per contract after the holder of the loan has made further collection efforts and instituted any required enforcement proceedings (§1423). The IDFC also must institute recovery efforts on the borrower. The BUILD Act puts limitations on the payment of losses, such as generally limiting it to the dollar value of tangible or intangible contributions or commitments made in the project plus interest, earnings, or profits actually accrued on such contributions or commitments to the extent provided by such insurance, reinsurance, or guarantee. The Attorney General must take action as may be appropriate to enforce any right accruing to the United States as a result of the issuance of any loan or guarantee under this title. The BUILD Act also imposes certain limitations on payments of losses.

For how long is the IDFC authorized?

The BUILD Act provides that the IDFC's authorities terminate seven years after the date of the enactment of the act (§1424). It also provides that the IDFC terminates on the date on which its portfolio is liquidated. This is markedly different from the annual extensions of authority required for OPIC in recent years. A longer-term authorization as given to the IDFC could be beneficial for supporting investments in infrastructure projects, which often are multiyear endeavors, as well as underscore a sustained U.S. commitment to respond to China's BRI.

Statutory Parameters for IDFC Project Support

Will there be terms and conditions of IDFC support?

The BUILD Act authorizes the IDFC to set terms and conditions for its support, subject to certain parameters.

Reason for support. The IDFC is only permitted to provide its support if it is necessary either to alleviate a credit market imperfection or to achieve a specified goal of U.S. development or foreign policy by providing support in the most efficient way to meet those objectives on a case-by-case basis (§1422(b)(1)).

Length of support. The final maturity of a loan or guarantee cannot exceed 25 years or the debt servicing capabilities of the project to be financed by the loan, whichever is lesser (§1422(b)(2)).

Risk-sharing. With respect to any loan guarantee to a project, the IDFC must require parties to bear the risk of loss in an amount equal to at least 20% of the guaranteed support by the IDFC to the project (§1422(b)(3))—compared to 50% risk-sharing in most cases for OPIC.

U.S. financial interest. The IDFC may not make a guarantee or loan unless it determines that the borrower or lender is responsible and that adequate provision is made for servicing the loan on reasonable terms and protecting the U.S. financial interest (§1422(b)(4)).

Interest rate. The interest rate for direct loans and interest supplements on guaranteed loans shall be set by reference to a benchmark interest rate (yield) on marketable Treasury securities or other widely recognized or appropriate comparable benchmarks, as determined in consultation with the Director of the Office of Management and Budget and the Secretary of the Treasury. The IDFC must establish appropriate minimum interest rates for loan guarantees, and other instruments as necessary. The minimum interest rate for new loans must be adjusted periodically to account for changes in the interest rate of the benchmark financial interest (§1422(b)(5) and (6)).

Fees and premiums. The IDFC must set fees or premiums for support at levels that minimize U.S. government cost while supporting the achievement of objectives for that support. The IDFC must review fees for loan guarantees periodically to ensure that fees on new loan guarantees are at a level sufficient to cover the IDFC's most recent estimates of its cost (§1422(b)(7)).

Budget authority. The IDFC may not make loans or loan guarantees except to the extent that budget authority to cover their costs is provided in advance in an appropriations act (§1422(b)(10)).

Standards. The IDFC must prescribe explicit standards for use in periodically assessing the credit risk of new and existing direct loans or guaranteed loans. It also must rely upon specific standards to assess the developmental and strategic value of projects for which it provides support and should only provide the minimum level of support needed to support such projects (§1422(b)(9) and (11)).

Seniority. Any loan or guarantee by the IDFC is to be on a senior basis or pari passu with other senior debt unless there is a substantive policy rationale for otherwise (§1422(b)(12)).

In which countries can the IDFC operate?

In general, the IDFC is to prioritize support for less-developed countries (i.e., with a "low-income economy or a lower-middle-income economy"), as defined by the World Bank (§1402 and §1411). It must restrict support in less-developed countries with "upper-middle-income economies" unless (1) the President certifies to Congress that such support furthers U.S. national economic or foreign policy interests; and (2) such support is designed to have "significant development outcomes or provide developmental benefits to the poorest population" of that country (§1412). This arguably narrows the IDFC's focus to low-income and lower-middle-income countries, compared to OPIC's statutory requirements and practice.27

The IDFC may provide support in any country the government of which has entered into an agreement with the United States authorizing the IDFC to provide support (§1431).

What considerations will factor into the IDFC's decision to support projects?

Preference for U.S. sponsors. The IDFC must give preferential consideration to projects sponsored by or involving private-sector entities that are "U.S. persons"—defined as either U.S. citizens or entities owned or controlled by U.S. citizens (§1451(b)). This presumably eases OPIC's requirement for projects to have a "U.S. connection" based on U.S. citizenship or U.S. ownership shares; the particular requirements vary by program. This change arguably opens up the possibility that the IDFC could support investments by foreign project sponsors, assuming they meet other statutory requirements.

Preference for countries in compliance with international trade obligations. The IDFC must consult at least annually with the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) regarding countries' eligibility for IDFC support and compliance with international trade obligations (§1451(c)). The IDFC must give preferential consideration to countries in compliance with (or making substantial progress in coming into compliance with) their international trade obligations. While OPIC does not have a comparable obligation, the USTR (or a designated Deputy USTR) is a member of OPIC's Board of Directors.

Worker rights. The IDFC can only support projects in countries taking steps to adopt and implement laws that extend internationally recognized worker rights (as defined in §507 of the Trade Act of 1974, 19 U.S.C. 2467) to workers in that country. It must include specified language in all contracts for support regarding worker rights and child labor (§1451(d)). These provisions appear to be similar to OPIC's requirements in terms of worker rights.

Environmental and social impact. The Board is prohibited from voting in favor of any project that is likely to have "significant adverse environmental or social impact impacts that are sensitive, diverse, or unprecedented" unless it provides an impact notification (§1451(e)). The act requires that (1) the notification be at least 60 days before the date of the Board vote and take the form of an environmental and social impact assessment or initial audit; (2) the notification be made available to the U.S. public and locally affected groups and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in the host country; and (3) the IDFC include provisions in any contract relating to the project to ensure mitigation of any such adverse environmental or social impacts. OPIC's enabling legislation has substantially similar requirements as the IDFC's first two requirements with respect to environmental and social impacts.

Women's economic empowerment consideration. The IDFC must consider the impact of its support on women's economic opportunities and outcomes and take steps to reduce gender gaps and maximize development impact by working to improve women's economic opportunities (§1451(f)). This is distinct from OPIC's statutory requirements.

Countries embracing private enterprise. The IDFC is directed to give preferential consideration to projects for which support may be provided in countries whose governments have demonstrated "consistent support for economic policies that promote the development of private enterprise, both domestic and foreign, and maintain the conditions that enable private enterprise to make full contribution to the development of such countries" (§1451(g)). The BUILD Act gives examples of market-based economic policies, protection of private property rights, respect for rule of law, and systems to combat corruption and bribery. OPIC's private enterprise-related requirement appears to be more limited.

Small business support. The IDFC must, using broad criteria, to the maximum extent possible, give preferential consideration to supporting projects sponsored by or involving small business, and ensure that small business-related projects are not less than 50% of all projects for which the IDFC provides support and that involve U.S. persons (§1451(i)). OPIC's small business support requirement has a 30% target.

What limitations will there be on the IDFC's support?

Limitation on support for a single entity. No entity receiving IDFC support may receive more than an amount equal to 5% of the IDFC's maximum contingent liability (§1451(a)). In comparison, OPIC has specific limitations by program; for example, no more than 10% of maximum contingent liability of investment insurance can be issued to a single investor, and no more than 15% of maximum contingent liability of investment guarantees can be issued to a single investor.

Boycott restriction. When considering whether to approve a project, the IDFC must take into account whether the project is sponsored by or substantially affiliated with any individual involved in boycotting a country that is "friendly" with the United States and is not subject to a boycott under U.S. law or regulation (§1451(h)). The measure is aimed at ensuring that beneficiaries of the new DFI's support are "not undermining [U.S.] foreign policy goals." Concerns about boycotts against Israel appear to figure prominently.28

International terrorism/human rights violations restriction. The IDFC is prohibited from providing support for a government or entity owned or controlled by a government if the Secretary of State has determined that the government has repeatedly provided support for acts of international terrorism or has engaged in a consistent pattern of gross violations of internationally recognized human rights (§1453(a)). In comparison, OPIC must take into account human rights considerations in conducting its programs.29

Sanctions restriction. The IDFC is also prohibited from all dealings related to any project prohibited under U.S. sanctions laws or regulations, including dealings with persons on the list of specially designated persons and blocked persons maintained by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) of the Department of the Treasury, except to the extent otherwise authorized by the Secretaries of the Treasury or State (§1453(b) and (c)). OPIC is subject to sanctions restrictions as well.

What requirements will the IDFC have to avoid market distortion?

Commercial banks can provide financing for foreign investment, such as through project finance, and political risk insurance. The BUILD Act requires that before the IDFC provides support, it must ensure that private-sector entities are afforded an opportunity to support the project. The IDFC must develop safeguards, policies, and guidelines to ensure that its support supplements and encourages, but does not compete with, private-sector support; operates according to internationally recognized best practices and standards to avoid market-distorting government subsidies and crowding out of private-sector lending; and does not have significant adverse impact on U.S. employment (§1452).

Monitoring and Transparency

What performance measures and evaluation will the IDFC have?

The BUILD Act requires the IDFC to develop a performance measurement system to evaluate and monitor its projects and to guide future project support, using OPIC's current development impact measurement system as a starting point (§1442). The IDFC must develop standards for measuring the projected and ex post development impact of a project. It also must regularly make information about its performance available to the public on a country-by-country basis.

Measuring development impact can be complicated for a number of reasons, including definitional issues, difficulties isolating the impact of development finance from other variables that affect development outcome, challenges in monitoring projects for development impact after DFI support for a project ends, and resource constraints. Comparing development impacts across DFIs is also difficult as development indicators may not be harmonized. To the extent that the proposed DFI raises questions within the development community about whether it would be truly "developmental" at its core, rigorous adherence to development objectives through a measurement system will likely be critical to gauging its effectiveness. Moreover, Congress may choose to take a broader view of U.S. development impact, given the active U.S. contributions to regional and multilateral DFIs.

What are the IDFC's reporting and notification requirements?

At the end of each fiscal year, the IDFC must submit to Congress a report including an assessment of its economic and social development impact, the extent to which its operations complement or are compatible with U.S. development assistance programs and those of qualifying sovereign entities, and the compliance of projects with statutory requirements (§1443). In addition, no later than 15 days before the IDFC makes a financial commitment over $10 million, the Chief Executive Officer must submit to the appropriate congressional committees a report with information on the financial commitment (§1446(a) and (b)). The CEO also must notify the committees no later than 30 days after entering into a new bilateral agreement (§1446(c)).

What information must it make available to the public?

The IDFC must "maintain a user-friendly, publicly available, machine-readable database with detailed project-level information," including description of support provided, annual report information provided to Congress, and project-level performance metrics, along with a "clear link to information on each project" online (§1444).

The new agency also must cooperate with USAID to engage with investors to develop a strategic relationship "focused at the nexus of business opportunities and development priorities" (§1445). This includes IDFC actions to develop risk mitigation tools and provide transaction-structuring support for blending finance models (generally referring to the strategic use of public or philanthropic capital to catalyze private-sector investment for development purposes).

Implementation

How and when is the IDFC expected to become operational?

The BUILD Act requires the President to submit to Congress within 120 days of enactment a reorganization plan that details the transfer of agencies, personnel, assets, and obligations to the IDFC. The reorganization plan is expected to be submitted by early February 2019.

The President must consult with Congress on the plan not less than 15 days before the date on which the plan is transmitted, and before making any material modification or revision to the plan before it becomes operational.

The reorganization plan becomes effective for the IDFC on the date specified in the plan, which may not be earlier than 90 days after the President has transmitted the reorganization plan to Congress (§1462(e)). The actual transfer of functions may occur only after the OPIC President and CEO and the USAID Administrator jointly submit to the foreign affairs committees a report on coordination, including a detailed description of the procedures to be followed after the transfer of functions to coordinate between the IDFC and USAID (§1462(c)). During the transition period, OPIC and USAID are to continue to perform their existing functions.

Thus, the IDFC could become operational as early as summer 2019 based on this timeline (Figure 2). OPIC anticipates that the IDFC could become operational as of October 1, 2019.30 At that time, OPIC is to be terminated and its enabling legislation is to be repealed (§1464).

|

|

Source: Created by CRS using information from the BUILD Act. |

How will the IDFC relate to other U.S. trade and investment promotion efforts?

The IDFC is to replace OPIC, and, as such, would be among other federal entities that play a role in promoting U.S. trade and investment efforts. The Export-Import Bank (Ex-Im Bank) provides direct loans, loan guarantees, and export credit insurance to support U.S. exports, in order to support U.S. jobs.31 The Trade and Development Agency (TDA) aims to link U.S. businesses to export opportunities in overseas infrastructure and other development projects, in order to support economic growth in these overseas markets.32 TDA provides funding for project preparation activities, such as feasibility studies, and partnership building, such as reverse trade missions bringing foreign decisionmakers to the United States. The IDFC's authority to conduct feasibility studies and provide other forms of technical assistance has raised questions about overlap with the functions of TDA, but BUILD Act supporters note that while functions may overlap, they will be for different purposes—supporting U.S. investment abroad in the case of the IDFC and supporting U.S. exports in the case of TDA.

There may also be some overlap of function between the IDFC and USAID if the reorganization plan calls for the transfer of the Office of Private Capital and Microenterprise from USAID to the IDFC and the IDFC starts its own microfinance programs, as microfinance activities are integrated throughout USAID and would not cease with the transfer of the office. Similarly, if the IDFC uses its authority to create new enterprise funds while declining to transfer existing funds under USAID authority, there may be some overlap in that authority as well.

Issues for the 116th Congress

The 116th Congress will have responsibility for overseeing the implementation of the BUILD Act, including review of the reorganization plan, the transition it prescribes, and impact on U.S. foreign policy objectives. As part of this process, Congress may consider a number of policy issues, including the following:

- Is the Administration meeting the implementation requirements of the BUILD Act? Does the reorganization plan reflect congressional intent, and are the choices made within the discretion allowed by the BUILD Act justified?

- How can the IDFC best balance its mission to support U.S. businesses in competing for overseas investment opportunities with its development mandate? What are the policy trade-offs associated with the capacity limits, authorities, policy parameters, and other features formulated by Congress in the BUILD Act? Does the legislation find the right balance, or does the implementation process identify areas where legislative changes might be beneficial?

- In creating the BUILD Act, Congress gave great consideration to strategic foreign policy concerns. In addition to providing commercial opportunities for U.S. firms, development finance may shape how countries connect to the rest of the world through ports, roads, and other transportation and technological links, providing footholds for the United States to advance its approaches to regulations and standards. Another potential role for development finance is to provide a means to spread U.S. values on governance, transparency, and environmental and social safeguards. Does the current statutory framework enable the IDFC to respond effectively to U.S. strategic concerns, particularly with regard to China's BRI? More fundamentally, is the IDFC's aim to compete with, contain, or counter the BRI and Chinese world vision it represents?

- Beyond establishing the IDFC, Congress may consider whether to advocate for creating international "rules for the road" for development finance. Such rules could help ensure that the IDFC operates on a "level playing field" relative to its counterparts, given the variation in terms, conditions, and practices of DFIs internationally. U.S. involvement in developing such rules could help advance U.S. strategic interests. However, such rules would only be effective to the extent that major suppliers of development finance are willing to abide by them. For example, China is not a party to international rules on export credit financing, though it has been involved in recent negotiations to develop new rules on such financing. Should Congress press the Administration to pursue international rules on development finance? Is it feasible to engage China in this regard?

Appendix. Reorganization of U.S. Government Development and/or Finance Functions

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Unless otherwise noted, section citations in parentheses as here refer to provisions of the BUILD Act as enacted. |

| 2. |

For more information on the legislative debate in the 115th Congress, see the archived CRS Report R45180, OPIC, USAID, and Proposed Development Finance Reorganization, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 3. |

Jonathan Woetzel et al., Bridging Global Infrastructure Gaps, McKinsey Global Institute, June 2016; and Oxford Economics, Global Infrastructure Outlook: Infrastructure Investment Needs, 50 Countries, 7 Sectors 2040, A G20 Initiative, July 2017. |

| 4. |

See CRS In Focus IF10659, Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC), by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 5. |

OPIC, "U.S.-Japan-Australia Announce Trilateral Partnership for Indo-Pacific Infrastructure Investment," July 30, 2018, press release. |

| 6. |

CRS Report R41170, Multilateral Development Banks: Overview and Issues for Congress, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 7. |

ODA is provided by the 29 members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee, which includes the United States. |

| 8. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Financing Overseas Development: The Administration's Proposal, Opening Statement of Ed Royce, Chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, 115th Cong., 1st sess., April 11, 2018. As noted earlier, on July 30, 2018, OPIC, the Japanese Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC, Japan's counterpart to OPIC), and the Australian government announced a trilateral partnership to mobilize investments in infrastructure projects in the Indo-Pacific region to support development, connectivity, and economic growth in the region. See OPIC, "U.S.-Japan-Australia Announce Trilateral Partnership for Indo-Pacific Infrastructure Investment," July 30, 2018, press release. |

| 9. |

See, for example, James Roberts and Brett Schaefer, House and Senate Revisions Have Not Improved the BUILD Act Enough to Warrant Conservative Support, The Heritage Foundation, July 24, 2018. |

| 10. |

See CRS Report R44754, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), by [author name scrubbed], and CRS In Focus IF10154, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 11. |

CRS In Focus IF10273, China's "One Belt, One Road", by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

| 12. |

Office of the Leading Group for the BRI, China's Contribution, May 2017, p. 32. |

| 13. |

Sabrina Snell, China's Development Finance: Outbound, Inbound, and Future Trends in Financial Statecraft, U.S.-China Economic and Security Commission, December 16, 2015, p. 2. |

| 14. |

One illustration of debt challenges associated with China's lending is Sri Lanka; in December 2017, Sri Lanka leased its Hambantota port to Beijing for 99 years after finding itself unable to repay China-backed loans to fund the port. This has "grant[ed] China a foothold in the Indian Ocean and its critical shipping lanes." U.S. Congress, House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development Act of 2018, H.Rept. 115-814, 115th Cong., 2nd sess., July 11, 2018, p. 25. |

| 15. |

For a fuller history of congressional action, see archived report CRS Report R45180, OPIC, USAID, and Proposed Development Finance Reorganization, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed], and CRS Report WPD00009, The BUILD Act and the New U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed] (a web podcast). |

| 16. |

Congress rejected the President's request and continued extending OPIC's authority and providing appropriations for the agency. |

| 17. |

Office of Management and Budget (OMB), An American Budget – President's Budget FY2019, p. 81; and OMB, Delivering Government Solutions in the 21st Century: Reform Plan and Reorganization Recommendations, June 21, 2018, p. 45. |

| 18. |

White House, "Statement from the Press Secretary Supporting the Goals of the Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development (BUILD) Act of 2018," press release, April 10, 2018. |

| 19. |

White House, "Statement from the Press Secretary on H.R. 5105/S. 2463, the Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development (BUILD) Act of 2018," press release, July 17, 2018. |

| 20. |

The White House, "Remarks by President Trump at APEC CEO Summit," press release, November 10, 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-apec-ceo-summit-da-nang-vietnam/. |

| 21. |

The White House, National Security Strategy of the United States of America, December 2017, p. 39. |

| 22. |

See, for example, Benjamin Leo and Todd Moss, Bringing US Development Finance into the 21st Century: Proposal for a Self-Sustaining, Full-Service USDFC, Center for Global Development, March 2015. |

| 23. |

See J.P. Morgan Securities, Inc., Overseas Private Investment Corporation: Final Report on the Feasibility of Privatization, New York, February 7, 1996, cited in GAO, Overseas Investment: Issues Related to the Overseas Private Investment Corporation's Reauthorization, GAO/NSIAD-97-230, September 1997, p. 24. |

| 24. |

Adva Saldinger, "BUILD Act for New U.S. Development Finance Corporation Sails Through Senate Committee Vote," Devex, June 27, 2018; and George Ingram, Building a Robust U.S. Development Finance Institution, Brookings, March 29, 2018. |

| 25. |

James Robert and Brett Schaefer, The BUILD Act's Proposed Development Finance Corporation Would Supersize OPIC But Not Improve It, Heritage Foundation, May 2, 2018. |

| 26. |

FCRA prescribes how to estimate the costs of profits of U.S. government programs that use direct loans and loan guarantees. CRS Report R44193, Federal Credit Programs: Comparing Fair Value and the Federal Credit Reform Act (FCRA), by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 27. |

By statute (22 U.S.C. §2191), OPIC must give preferential consideration to investment projects in less-developed countries and restrict its support in other higher-income countries. However, OPIC, based on legislative history, interprets the statutory requirement as allowing it to support projects in higher income countries that are highly developmental, focus on underserved areas or populations, or support U.S. small business. |

| 28. |

Congressman Brad Sherman, "Congressman Sherman's Pro-Israel Amendments Unanimously Pass the House Foreign Affairs Committee," press release, May 9, 2018. |

| 29. |

Specifically, OPIC is required to take into account in conducting its programs in a country, in consultation with the Secretary of State, "all available information about observance of and respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms in such country and the effect the operation of such programs will have on human rights and fundamental freedoms in such country" (22 U.S.C. §2199(i)). |

| 30. |

OPIC, "The BUILD Act," https://www.opic.gov/build-act/overview. |

| 31. |

See CRS Report R43581, Export-Import Bank: Overview and Reauthorization Issues, by [author name scrubbed]; and CRS In Focus IF10017, Export-Import Bank of the United States (Ex-Im Bank), by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 32. |

CRS In Focus IF10673, U.S. Trade and Development Agency (TDA), by [author name scrubbed]. |