Overview1

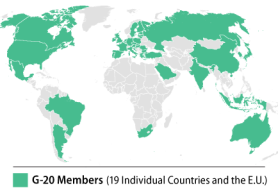

Members of Congress may address numerous ongoing and new policy issues in the second session of the 116th Congress. The changing dynamics and composition of international trade and finance can affect the overall health of the U.S. economy, the success of U.S. businesses and workers, and the U.S. standard of living. They also have implications for U.S. geopolitical interests. Conversely, geopolitical tensions, risks, and opportunities can have major impacts on international trade and finance. These issues are complex and at times controversial, and developments in the global economy often make policymaking more challenging. Congress is in a unique position to address these and other issues given its constitutional authority for legislating and overseeing international commerce.

A major focus of the 116th Congress during its first session was overseeing the Trump Administration's evolving trade policy. The Trump Administration's approach to international trade arguably represents a significant shift from the approaches of prior administrations, in that it questions the benefits of U.S. leadership in the rules-based global trading system and expresses concern over the effectiveness of this system. As such, the Administration's imposition of unilateral trade restrictions on various U.S. imports—particularly from China, efforts to ratify the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), trade negotiations with China, Japan, and the European Union, and continued review of U.S. participation in the World Trade Organization (WTO) were among the most notable developments in U.S. trade policy over the past year. Other issues before Congress included overseeing the implementation of legislation to strengthen the process used to review the national security implications of foreign investment transactions in the United States, as well as to modernize U.S. development finance tools that help advance U.S. national economic interests and global influence. Continued focus on economic sanctions against Turkey, Russia, North Korea, Iran, Cuba, and other countries were also of interest to many in Congress.

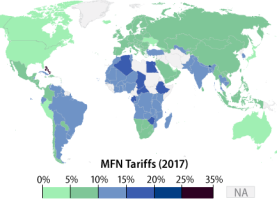

The Trump Administration has displayed a more critical view than past administrations of U.S. trade agreements, made greater use of various U.S. trade laws with the potential to restrict U.S. imports, and focused on bilateral trade balances as a key metric of the health of U.S. trading relationships. As part of this shift in focus, the Administration has placed a greater emphasis on "fair" and "reciprocal" trade. China has also been a center of attention as the Administration seeks to address longstanding concerns over its policies on intellectual property (IP), forced technology transfer, and innovation. Citing these concerns and others, the President has unilaterally imposed trade restrictions on a number of U.S. imports under U.S. laws and authorities—most of which have been used infrequently since the establishment of the WTO in 1995. During the first session, many Members continued to weigh in on the President's trade actions. While some supported his use of unilateral trade measures, others raised concerns about potential negative economic implications of these actions for U.S. firms, farmers and workers, and the risks they may pose to the rules-based international trading system. Several Members introduced bills to amend some of the President's trade authorities—for example, to require congressional consultation or approval before imposing new trade barriers on imports for national security reasons.

The implications of changes in the U.S. trade policy landscape for the next year will depend on a number of factors, including the impact of the Administration's trade actions—particularly increased tariffs—on U.S. industries, firms, workers, and supply chains; the reaction of U.S. trading partners; and the extent to which future actions are in line with core U.S. commitments and obligations under the WTO and other trade agreements. The U.S.-China trade and economic relationship is complex and wide-ranging, and it may entail continued close examination by Congress. In addition to specific trade practices of concern, Congress may continue to scrutinize the economic and geopolitical implications of China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which finances and develops infrastructure projects across a number of countries and regions. Congress may also examine the U.S.-China Phase One trade deal and next steps, and the ongoing economic implications of China's industrial policies in high technology sectors, which could potentially challenge U.S. firms and disrupt global markets.

How these issues play out, combined with the evolving global economic landscape, raise potentially significant legislative and policy questions for Congress. Members may consider (1) the implementation of the USMCA, once it is ratified by the government of Canada; (2) next steps in future U.S.-China trade talks and the next phase of the U.S.-Japan trade agreement negotiations; (3) measures to reassert its constitutional authority over tariffs and other trade restrictions or to narrow the scope of how the president can use delegated authorities to impose such restrictions; (4) the extent to which past U.S. FTAs should be modernized or revised and, if so, in what manner; (5) what priority should be given to negotiating new U.S. FTAs with the European Union, the United Kingdom, and other trading partners, as well as the scope of negotiations; and (6) the impact of FTAs excluding the United States on U.S. economic and broader interests, and the appropriate U.S. response to the proliferation of such agreements. Another major issue is the role of the United States in the multilateral, rules-based trading system underpinned by the WTO. Historically, U.S. leadership in the global trading system has enabled the United States to shape the international trade agenda in ways that both advance and defend U.S. interests. The growing debate over the role and future direction of the WTO may raise important issues for Congress, such as how current and future WTO agreements affect the U.S. economy, the value of U.S. membership and leadership in the WTO, and the need to update or adapt WTO rules to reflect 21st century realities. Such updates might address advances in technology, new forms of trade barriers, and market-distorting government policies.

This report provides a broad overview of select topics in international trade and finance. It is not an exhaustive look at all issues, nor is it a detailed examination of any one issue. Rather, it provides concise background information of certain prominent issues that have been the subject of recent discussion and debate, and that may come before the 116th Congress during its second session. It also include references to more in-depth CRS products on the issues.

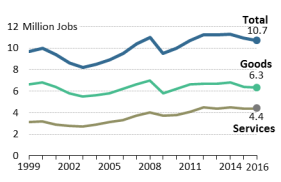

The United States in the Global Economy2

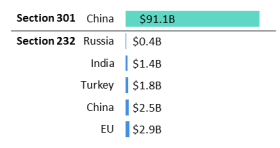

In 2018, the global economy began to display signs of a synchronized slowdown, which some analysts contend continued into 2019.3 The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that real global gross domestic product (GDP) fell from 3.8% in 2017 to 3.6% in 2018—the most recent year for which annual data are available (Figure 1). As a group, advanced economies grew 2.3% (down from 2.5% in 2017),4 while emerging market and developing economies grew 4.5% (down from 4.8% in 2017). The growth performance of major U.S. trading partners diverged widely in 2018, affecting both their bilateral trade and investment relations with the United States and their exchange rates against the U.S. dollar. The European Union (EU)'s real GDP growth rate fell from 2.5% in 2017 to 1.9% in 2018, while that of Canada dropped to 1.9% (from 3.0% in 2017). Other top U.S. trading partners, including China, Mexico, Japan, South Korea, India, and Taiwan experienced lower growth in 2018 than in 2017.

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS with data from the International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019; World Bank, World Development Indicators, 2019; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, UNCTADstat, 2019. Notes: 2018 is the most recent year for which yearly data are available. Real GDP Growth: percent change in gross domestic product (GDP) from preceding year; Share of World GDP: each country's GDP as a share of world GDP (in current U.S. dollars); Share of World Exports and Imports: each country's total exports (imports) of goods and services as a share of total world exports (imports) of goods and services; Share of World FDI: each country's inward (outward) foreign direct investment (FDI) flows as a share of world inward (outward) FDI flows. |

The IMF forecasts weaker performance in the short-term for both advanced economies—1.7% for 2019—and emerging market and developing economies—3.9% in 2019.5 This growth is projected to improve in the medium term, however, as output gaps close and advanced economies return to their potential output paths.6 Beyond the short term, growth rates are expected to fall below pre-recession levels, as the aging populations and shrinking labor forces in advanced economies are expected to act as a drag on expansion. Overall fiscal policy is expected to remain expansionary in 2020. In addition, monetary policy may remain supportive in the Eurozone and Japan. In early 2019, the U.S. Federal Reserve reversed its policy of slight monetary tightening due to U.S. and global economic and financial market developments. More broadly, global financial conditions are expected to remain generally accommodative.

Emerging markets (EMs) as a group face growing vulnerabilities to their economies due to uncertainties about global trade, depreciating currencies and risks of capital flight, volatile equity markets, large debts denominated in foreign currencies, and, in certain areas, the lack of deeper economic reform. Increased uncertainty over political and policy direction could continue to constrain the rate of growth in Argentina, Brazil, Pakistan, Turkey, and South Africa. Additionally, China is expected to experience slower growth rates in the coming years, as the economy is affected by U.S.-China trade tensions and rebalances away from investment toward private consumption, and from industry to services. The rise in China's nonfinancial debt as a share of GDP is likely to contribute to this downward trend. In Venezuela, the economy has collapsed, with the inflation rate forecast by the IMF to reach 200,000% in 2019. In addition, low commodity prices, particularly oil, could increase concerns in commodity-producing economies—many of them EMs—and destabilize national incomes. These and other developments could add to uncertainties in global financial markets, raise risks for U.S. banks of nonperforming loans, complicate the efforts of some banks to rebuild their capital bases, and potentially dampen prospects for long-term gains in productivity and higher rates of economic growth.

The United States continues to experience strong economic fundamentals and remains a relatively bright spot within the global economy, which could help it sustain its position as one of the main drivers of global economic growth. With 4% of the world's population, it accounted for almost 24% of the world's output in nominal U.S. dollars, close to 10% of its exports (goods and services), and approximately 21% of its growth in 2018.7 The U.S. economy grew faster in 2018 than in 2017: U.S. real GDP increased 2.9% in 2018, up from 1.6% in 2016 and 2.4% in 2017. The latest U.S. data show signs of continuing relative strong performance in 2019, with the IMF forecasting 2.4% growth and the U.S. Federal Reserve estimating growth between 2.1% and 2.4%.8 (According to the most recent official estimate, in the third quarter of 2019, real U.S. GDP increased at an annual rate of 2.1%, up from 2.0% in the second quarter.9) Some forecasts indicate that U.S. growth could decelerate in the coming years, for reasons such as higher commodity prices, upward inflationary pressures, a return to monetary policy tightening by the U.S. Federal Reserve, trade policy uncertainties, and global risks.10 Labor market data indicate that the United States might be at full employment, as the jobless rate reached 3.5% at the end of 2019 and is projected to remain below 4.0% in 2020. The relatively low price of oil (and fluctuations thereof) is affecting not only the global economy, but also the U.S. economy. While drops in energy prices may raise U.S. consumers' real incomes and improve the competitive position of some U.S. industries, these positive effects may be offset to some extent by a drop in employment and investment in the U.S. energy sector.

Amid potential downside risks in the global economy, the IMF and the WTO have downgraded their forecasts for trade growth in 2019 and 2020. Risks include continued trade tensions between major economies like the United States and China, and continued trade policy uncertainty.11 Restrictive trade policy measures imposed by the United States and some of its major trading partners may continue to affect trade flows and prices in targeted sectors. Analysts claim that some recent policy announcements also have harmed business outlooks and investment plans, due to heightened concern over possible disruptions to supply chains and the risks of potential increases in the scope or intensity of trade restrictions.12 The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) projects that a further rise in trade tensions may have additional adverse effects on global investment, economic growth, and job creation.13

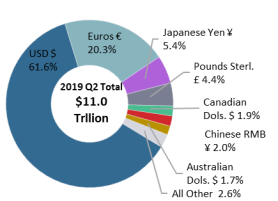

In addition, in 2018, exchange rates experienced volatility, with a number of currencies depreciating against the U.S. dollar, including the Chinese renminbi, Argentine peso, and Brazilian real. Volatile currency and equity markets—combined with uncertainties over global trade and rates of inflation that remain below the target levels of a number of central banks—could further complicate efforts by the U.S. Federal Reserve to normalize monetary policy.14 Other major economies, such as Eurozone and Japan, may continue to pursue unconventional monetary policies. Uncertainties in global financial markets could put additional upward pressure on the U.S. dollar, as investors may seek "safe haven" currencies and dollar-denominated investments. For some economies, volatile currencies and continued low commodity prices could add to debt issues, raising the prospect of defaults and potential economic crises.

The Role of Congress in International Trade and Finance15

The U.S. Constitution assigns authority over foreign trade to Congress. Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution gives Congress the power to "lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts, and Excises" and to "regulate Commerce with foreign Nations." For the first 150 years of the United States, Congress exercised its power to regulate foreign trade by setting tariff rates on all imported products. Congressional trade debates in the 19th century often pitted Members from northern manufacturing regions, who benefitted from high tariffs, against those from largely southern raw material exporting regions, who gained from and advocated for low tariffs.

A major shift in U.S. trade policy occurred after Congress passed the highly protective "Smoot-Hawley" Tariff Act of 1930, which significantly raised U.S. tariff levels and led U.S. trading partners to respond in kind. As a result, world trade declined rapidly, exacerbating the impact of the Great Depression. Since the passage of the Tariff Act of 1930, Congress has delegated certain trade authority to the executive branch. First, Congress enacted the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934, which authorized the President to enter into reciprocal agreements to reduce tariffs within congressionally pre-approved levels, and to implement the new tariffs by proclamation without additional legislation. Congress renewed this authority periodically until the 1960s. Subsequently, Congress enacted the Trade Act of 1974, aimed at opening markets and establishing nondiscriminatory international trade norms for nontariff barriers as well. Because changes in nontariff barriers in reciprocal bilateral, regional, and multilateral trade agreements may involve amending U.S. law, the agreements require congressional approval and implementing legislation. Congress has renewed or amended the 1974 Act five times. Since 2002, "fast track" has been known as trade promotion authority (TPA). In 2015, Congress authorized a new TPA through July 1, 2021 (see below).

Congress also exercises trade policy authority through the enactment of laws authorizing trade programs and measures to address unfair and other trade practices. Additionally, it conducts oversight of the implementation of trade policies, programs, and agreements. These include such areas as U.S. trade agreement negotiations, tariffs and nontariff barriers, trade remedy laws, import and export policies, economic sanctions, and the trade policy functions of the federal government.

Over the years, Congress has authorized a number of trade laws that delegate a range of authorities to the President to investigate and take actions on imported goods for national security purposes (Section 232, Trade Expansion Act of 1962), trade remedies to counter dumping and subsidy practices by other countries, unfair trade practices (Section 301, Trade Act of 1974), or safeguard measures (Section 201, Trade Act of 1974). The Trump Administration is using these provisions to impose steel and aluminum tariffs on major trading partners and for possible tariffs on vehicles and auto parts for national security purposes,16 and on a range of Chinese products for what the Administration deems as unfair trading practices, including intellectual property theft and other practices. Some Members of Congress have opposed the use of these tariffs and in its second session, Congress may seek to revisit or curtail these statutes.

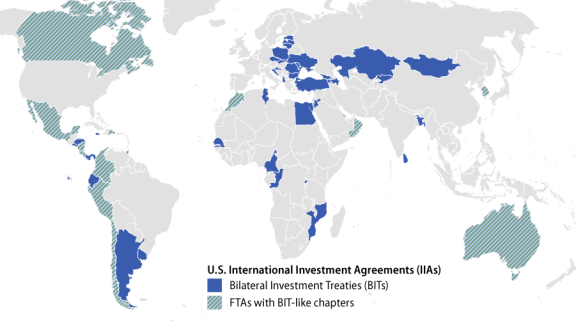

Additionally, Congress has an important role in international investment and finance policy. Under its treaty powers, the U.S. Senate considers bilateral investment treaties (BITs), and Congress sets the level of U.S. financial commitments to the multilateral development banks (MDBs), including the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. It also funds the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) and other trade agencies, and authorizes the activities of various agencies, such as the Export-Import Bank (Ex-Im Bank) and the newly operational U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), which is the successor to the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC). Congress also has oversight responsibilities over these institutions, as well as the Federal Reserve and the U.S. Department of the Treasury, whose activities can affect international capital flows and short-term movements in the international exchange value of the U.S. dollar. Congress also closely monitors developments in international financial markets that could affect the U.S. economy.

Trade Promotion Authority (TPA)17

Trade Promotion Authority is a primary means by which Congress asserts its constitutional authority over trade policy, particularly U.S. trade agreements. TPA—the Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-26)—which was signed by President Obama on June 29, 2015, is in place until July 1, 2021. Any agreement entered in by that date, which includes the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, is eligible for consideration under TPA. TPA authorizes qualifying implementing legislation for trade agreements to be considered under expedited legislative procedures—limited debate, no amendments, and an up or down vote—provided the President observes certain statutory obligations in negotiating trade agreements. These obligations include achieving progress in meeting congressionally defined U.S. trade policy negotiating objectives, as well as congressional notification and consultation requirements before, during, and after the completion of the negotiation process.

|

TPA: Key Facts

|

The primary purpose of TPA is to preserve the constitutional role of Congress with respect to the consideration of implementing legislation for trade agreements that require changes in domestic law. Another rationale for TPA has been to bolster the negotiating credibility of the executive branch by ensuring that trade agreements will not be changed once concluded. However, more recent FTAs, including the USMCA, have undergone additional negotiation after conclusion, perhaps eroding some of this rationale for TPA. Since the authority was first enacted in the Trade Act of 1974 (P.L. 93-618), Congress has renewed TPA four times (1979, 1988, 2002, and 2015) and amended it in 1984 to allow for the negotiation of bilateral agreements. In addition, TPA legislative procedures are considered rules of the House and Senate, and, as such, can be changed at any time. Precedent exists for implementing legislation to have its eligibility for expedited treatment under TPA removed by Congress. In 2020, Congress may use TPA to consider trade agreements negotiated by the Administration. It may also begin debate and examine future prospects for renewing and potentially revising the authority in light of its expiration in 2021.

Key International Economic and Trade Debates18

The United States has been a driving force in breaking down trade and investment barriers across the globe and constructing an open and rules-based global trading system through a wide range of international institutions and agreements. Since 1934, U.S. policymakers across political parties have recognized the importance of pursuing trade policies that promote more open, rules-based, and reciprocal international commerce, while being cognizant of potential costs to specific segments of the population, particularly through greater competition.19 Although there is a general consensus that, in the aggregate, the overall economic benefits of reducing barriers to trade and investment outweigh the costs, the processes of trade and financial liberalization, and of globalization more broadly, have presented both opportunities and challenges for the United States. Many U.S. consumers, workers, farmers, firms, and industries have benefited from increased trade. On the consumption side, U.S. households have enjoyed lower product prices and a broader variety of goods and services—some of which the United States does not produce in large quantities. On the production side, stronger linkages to the global economy force U.S. industries and firms to focus on areas in which they have a comparative advantage, provide them with export and import opportunities, enable them to realize economies of scale, and encourage them to innovate.

At the same time, some stakeholders argue that globalization is not inclusive, benefiting some more than others. They point to job losses, stagnant wages, and rising income inequality among some groups—as well as to environmental degradation—as indicators of the negative impact of globalization on the U.S. economy, although the causes of these trends are highly contested. Some policymakers also perceive growing bilateral U.S. trade deficits as evidence that U.S. trade with other nations is "uneven" or that foreign countries engage in "unfair" trade practices. Others view many of the existing global trade rules as outdated, since they do not reflect the realities of the 21st century—particularly when it comes to technological advances, new forms of trade (such as digital trade), and market-distorting government policies. Finally, some experts argue that the 2008-2009 financial crisis caused painful adjustment and costs for some segments of the population, which have exacerbated concerns related to U.S. trade policy and have led to increased domestic nationalism.

A longstanding objective of some Members of Congress and administrations has been to achieve a "level playing field" for U.S. industries, farmers and workers, and to preserve the United States' high standard of living—all while remaining innovative, productive, and internationally competitive, as well as safeguarding those stakeholders who otherwise may be left behind in a fast-changing global economy. Given Congress' constitutional authority over U.S. trade policy, Members are in a unique to position to influence, legislate, and oversee responses that support these goals and that reduce or soften the hardships and costs from international trade.

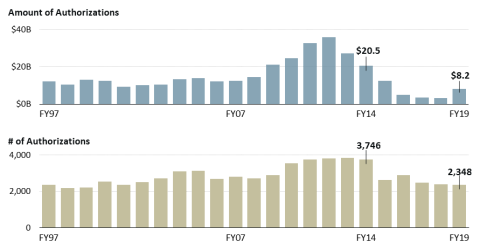

Trade and U.S. Employment20

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS with data from the U.S. Department of Commerce's International Trade Administration. |

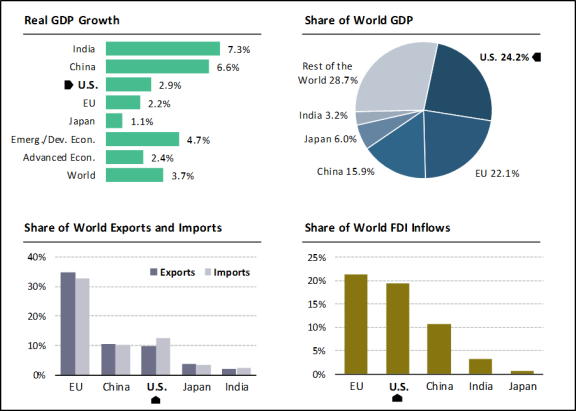

A key question in policy debates over international trade is its impact on U.S. jobs. Trade is one among a number of forces that drive changes in employment, wages, the distribution of income, and ultimately the U.S. standard of living. Most economists argue that macroeconomic forces within an economy, including technological and demographic changes, are the dominant factors that shape trade and foreign investment relationships and complicate efforts to disentangle the distinct impact that trade has on the economy. In a dynamic economy like that of the United States, jobs are constantly being created and replaced as some economic activities expand, while others contract. Various measures are used to estimate the role and impact of trade in the economy and of trade on employment. One measure developed by the U.S. Department of Commerce concludes that, as of 2016 (the most recent year for which data is available), exports support, directly and indirectly, 10.7 million jobs in the U.S. economy: 6.3 million in the goods-producing sectors and 4.4 million in the services sector (Figure 2). According to these estimates, jobs associated with international trade, especially jobs in export-intensive manufacturing industries, earn 18% more on a weighted average basis than comparable jobs in other manufacturing industries.21

Trade and trade liberalization can have a differential effect on workers and firms in the same industry. Some estimates indicate that the short-run costs to workers who attempt to switch occupations or switch industries in search of new employment opportunities may experience substantial effects. One study concluded that workers who switched jobs as a result of trade liberalization generally experienced a reduction in their wages, particularly in occupations where workers performed routine tasks.22 These negative income effects were especially pronounced in occupations exposed to imports from low-income countries. In contrast, occupations associated with exports experienced a positive relationship between rising incomes and growth in export shares. As a result of the differing impact of trade liberalization on workers and firms, Congress created Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) programs to mitigate the potential adverse effects of trade liberalization on workers, firms, and farmers (see text box below).

|

Trade Adjustment Assistance23 Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) is a group of programs that provide federal assistance to parties that have been adversely affected by foreign trade. TAA programs are authorized by the Trade Act of 1974, as amended, and were last reauthorized by the Trade Adjustment Assistance Reauthorization Act of 2015 (TAARA; Title IV of P.L. 114-27). The largest TAA program, TAA for Workers (TAAW), provides federal assistance to workers who have been separated from their jobs because of increases in directly competitive imports or because their jobs moved to a foreign country. The largest components of the TAAW program are (1) funding for career services and training to prepare workers for new occupations and (2) income support for workers who are enrolled in an eligible training program and have exhausted their unemployment compensation. In most cases, the benefits available to TAAW-eligible workers are more robust than those available to other unemployed workers. The TAAW program is administered at the federal level by the U.S. Department of Labor and the FY2020 appropriation was $680 million. In addition to the workers program, TAA programs are also authorized for firms and farmers that have been adversely affected by international competition. TAA for Firms is administered by the U.S. Department of Commerce and the FY2020 appropriation was $13 million. The TAA for Farmers program was reauthorized by TAARA, but the program has not received an appropriation since FY2011. TAA programs have historically been reauthorized in conjunction with other expansionary trade policies. For example, TAARA was enacted alongside renewal of the Trade Promotion Authority in 2015. Supporters of TAA view it as a means of offsetting some of the negative domestic effects of increased imports and increased offshoring that may result from expansionary trade policy. Some TAA supporters have proposed further expanding TAAW eligibility, such as including domestic workers who are adversely affected by reduced exports due to tariffs. Opponents of TAA typically view the program as duplicative, noting that trade-affected workers can be served by more general workforce programs that serve all unemployed workers. |

U.S. Trade Deficit24

The overall U.S. trade deficit, or more broadly the current account balance, represents an accounting principle that expresses the difference between the country's exports and imports of goods and services. The United States has experienced annual current account deficits since the mid-1970s. Congressional interest in the trade deficit has been heightened by the Trump Administration's approach to international trade. The Administration has used the U.S. trade deficit as a barometer for evaluating the success or failure of the global trading system, U.S. trade policy, and U.S. trade agreements. It has characterized the trade deficit as a major factor in a number of perceived ills afflicting the U.S. economy—including the rate of unemployment in some sectors and slow gains in wages—and partially as the result of unfair trade practices by foreign competitors.

Many economists, however, argue that this characterization misrepresents the nature of the trade deficit and the role of trade in the U.S. economy.25 In general, traditional economic theory holds that the overall size of the U.S. trade deficit stems largely from U.S. macroeconomic policies and an imbalance between saving and investment in the U.S. economy. Currently, the demand for capital in the U.S. economy outstrips the amount of gross savings supplied by households, firms, and the government (a savings-investment imbalance). Therefore, many observers argue that attempting to alter the trade deficit without addressing the underlying macroeconomic issues would be counterproductive and create distortions in the economy. A concern expressed by some analysts and policymakers is the debt accumulation associated with sustained trade deficits. They argue that the long-term impact on the U.S. economy of borrowing to finance imports depends on whether those funds are used for greater investments in productive capital with high returns that raise future standards of living, or whether they are used for current consumption. These concerns and the various policy approaches that have been used to alter the savings-investment imbalance in the economy are beyond the scope of this report.

Managed Trade26

During 2018 and 2019, the Trump Administration turned to quotas and quota-like arrangements to achieve some of its trade objectives. It negotiated potential quotas on autos through side letters to the proposed United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement27, as well as quota arrangements that allowed certain U.S. trading partners to avoid U.S. tariff increases on steel and aluminum imports. In addition, in trade negotiations, the Administration has demanded that China increase its purchases of U.S. agricultural products by specific amounts. Some Members of Congress have questioned whether these actions represent an undesirable shift in U.S. trade policy—towards one that some analysts have labeled managed trade. Managed trade generally refers to government efforts to achieve measurable results by establishing—through quantitative restrictions on trade and other numerical targeted approaches—specific market shares or targets for certain products. These are met through mutual agreement or under threat of trade action (e.g., increased tariffs). During the second session, the 116th Congress may examine the extent to which the Administration is adopting such an approach, including its effectiveness and impact on U.S. and international trade.

Advocates of managed trade policies contend that, by negotiating results-oriented agreements and using the size of the U.S. economy as leverage, the United States can ensure that trade with certain trading partners is "fair," "balanced," and "reciprocal." In addition, they argue, it will force countries to change their distortive economic policies, decrease the size of the U.S. trade deficit and, by reducing U.S. imports, help strengthen certain U.S. industries and boost U.S. employment. Other policymakers view these measures as protectionist and harmful to the economy. Many economists question the efficacy of prodding U.S. trading partners into negotiating or accepting quotas or numerical targets, as well as the ability of the state, rather than market forces, to provide the most efficient allocation of scarce resources—even when attempting to respond to trade-distorting measures by trading partners. They also note that policies that restrict U.S. imports and boost U.S. exports may not decrease the overall size of the U.S. trade deficit, as it is primarily the result of macroeconomic forces—namely the low level of U.S. savings relative to total investment. According to some observers, a move away from a market-driven, multilateral rules-based system to one driven by numerical outcomes and targets could lead to increasing trade restrictions, retaliation or replication by other countries, higher prices, lower global economic growth, and erosion of the international trading system.

Trade and Technology28

The rapid growth of digital technologies has created new opportunities for U.S. consumers and businesses but also new challenges in international trade. For example, consumers today access e-commerce, social media, telemedicine, and other offerings not available thirty years ago. Businesses use advanced technology to reach new markets, track global supply chains, analyze big data, and create new products and services. New technologies and the convergence between telecommunications, media and consumer electronics, and information technology facilitate economic activity but also create new trade policy questions and concerns.

No comprehensive agreement on digital trade exists in the WTO nor is there a single set of international rules or disciplines that govern key digital trade issues. The lack of multilateral rules governing the digital economy has led, on the one hand, to countries establishing diverging national policies that may create discriminatory and trade distorting barriers and, on the other hand, to efforts to establish common global rules through trade negotiations.

Recent international negotiations have sought to improve and remove barriers to market access for trade in digital goods and services and address other concerns, such as cybersecurity and privacy protection. Traditional trade barriers such as tariffs or export controls can hinder trade in information and communication technologies (ICT) products, whether physical goods (e.g., laptops) or emerging technologies, including algorithms and artificial intelligence. Nontariff barriers impede U.S. firms' market access by limiting what companies can offer or how they can operate in a foreign market, such as requiring local content or partners. Another often-cited digital trade barrier is data localization requirements or cross-border data flows restrictions that policymakers may enact to promote safety, security, privacy or favor domestic firms but that raise costs and risks for foreign firms.29 Technology transfer requirements and cybersecurity issues include the infringement of intellectual property and theft of trade secrets, economic espionage, and may touch on national security concerns.

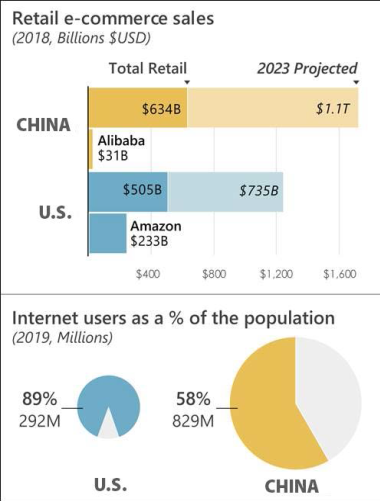

China, in particular, presents a number of significant opportunities and challenges for the United States in digital trade. The Chinese retail e-commerce is expected to grow 70% from 2018 to 2023, compared to 45% U.S. growth over the same time period, making it an attractive market for U.S. businesses (Figure 3).30 However, China's trade and internet policies reflect state direction and industrial policy and discriminate against foreign companies. For example, under its concept of "internet sovereignty," China seeks to control what digital data is permitted within its borders and how it is used, limiting the free flow of information and individual privacy as well as market access by U.S. firms.

|

|

Source: U.N. population statistics, Statista.com, Internetworldstats.com. |

During its second session, the 116th Congress may consider a variety of issues related to technology and trade. These include provisions in the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, U.S. participation in e-commerce negotiations at the World Trade Organization, evolving online privacy policies in the United States and other countries, such as the implementation of the European Union's privacy regulation and pending digital legislation. Additional issues involve technology trade issues with China, such as those outlined in the Trump Administration's investigation under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 (see Tariff Actions by the Trump Administration).

Economics and National Security31

U.S. officials have long recognized that U.S. economic interests are vital to national security concerns and have considered the concepts of "geoeconomics"32 and "economic statecraft" in relation to national security strategy.33 Broadly speaking, these terms refer to the political consequences of economic decisions or the economic consequences of political trends and the dynamics of national power.

In recent years, a combination of domestic and international forces are challenging the U.S. leadership role in ways that are unprecedented in the post-World War II era. For some observers, these challenges are not just about economic growth and international economic engagement, but directly affect U.S. national security. In their view, China's growing economic competition for leading-edge technologies, in particular, challenges not only U.S. commercial interests, but potentially threatens U.S. national security interests.

According to some observers, since taking office, the Trump Administration has promoted a form of national security that mixes trade and economic relationships with national security, defense, and foreign policy objectives in ways that seem more confrontational than cooperative, more unilateral than multilateral, and more central to its overall agenda than in previous administrations. For example, the Trump Administration has used the U.S. trade deficit and import tariffs to support the defense industrial base by placing tariffs on the imports of strategic security partners as a form of national economic security. Despite existing National Security Strategy (NSS) reports and previous executive branch efforts, there is a view that the United States lacks a holistic, whole-of-government approach for thinking about economic challenges and opportunities in relation to U.S. national security.34 In 2018, Congress adopted and President Trump signed the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 (FIRRMA) to expand the scope of national reviews by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) to determine if foreign investment transactions "threaten to impair the national security" of the United States. On January 13, 2020, the U.S. Treasury issued final regulations concerning implementation of various provisions of FIRRMA, which are to become effective on February 13, 2020. Also, on November 7, 2019, Senators Todd Young, Christopher Coons, Jeff Merkley, and Marco Rubio introduced S. 2826, the Global Economic Security Strategy of 2019 to "ensure Federal policies, statutes, regulations, procedures, data gathering, and assessment practices are optimally designed and implemented to facilitate the competitiveness, prosperity, and security of the United States." This and similar legislation may be considered in the second session of the 116th Congress.

Policy Issues for Congress

Policy debates in the coming year may include the use and impact of unilateral tariffs imposed by the Trump Administration under various U.S. trade laws, as well as potential legislation that alters the authority granted by Congress to the President to do so; U.S.-China trade relations; implementation of the proposed United States-Mexico-Canada Trade Agreement, which awaits ratification by the government of Canada; and the Administration's launch of bilateral trade negotiations with the European Union and the United Kingdom, among many others. The following section provides a broad overview of the potentially more prominent issues in international trade and finance that the 116th Congress may consider during its second session.

Tariff Actions by the Trump Administration35

The Trump Administration has focused on concerns over trading partner trade practices, the U.S. trade deficit, and potential negative effects of U.S. imports. Citing these concerns and others, the President has unilaterally imposed increased tariffs under three U.S. laws:

- (1) Section 20136 of the Trade Act of 1974 on U.S. imports of washing machines and solar products due to concerns over their effects on U.S. domestic industry;

- (2) Section 23237 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 on U.S. imports of steel and aluminum, and potentially motor vehicles/parts and titanium sponge due to concerns over their effects on U.S. national security;38 and

- (3) Section 30139 of the Trade Act of 1974 on U.S. imports from China due to concerns over its intellectual property rights practices, on U.S. imports from the EU due to the EU's WTO-inconsistent subsidies on the manufacture of large civil aircraft (and the EU's failure to implement WTO Dispute Settlement Body recommendations), and potentially on U.S. imports from France due to concerns over its digital services tax (DST).40

The President also proposed increasing tariffs on imports from Mexico, due to concerns over Mexico's immigration policies, using authorities delegated by Congress under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA),41 but subsequently suspended the proposed tariffs citing an agreement reached with Mexico.42

Congress delegated aspects of its constitutional authority to regulate foreign commerce to the President through these trade laws. They allow presidential action, based on agency investigations and other criteria, to impose import restrictions to address specific concerns (Table 1). They have been used infrequently in the past two decades, in part due to the 1995 creation of the World Trade Organization and its dispute settlement system. The Administration argues the unilateral tariffs are a necessary U.S. response to challenges in the global trading system, which the WTO has been unable to address effectively, and that they provide the United States with leverage for broader trade negotiations with affected trading partners, such as China, Japan, and the EU. While the tariffs benefit some import-competing U.S. firms, they also increase costs for downstream users of imported products and consumers and may have broader negative effects on the U.S. economy, as well as several policy implications.

|

Section 201 Trade Act of 1974 |

Allows the President to impose temporary duties and other trade measures if the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) determines a surge in imports is a substantial cause or threat of serious injury to a U.S. industry. |

|

Section 232 Trade Expansion Act of 1962 |

Allows the President to take action to adjust imports of products the U.S. Department of Commerce finds to be imported into the United States in such quantities or under such circumstances as to threaten to impair U.S. national security. |

|

Section 301 Trade Act of 1974 |

Allows the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) to suspend trade agreement concessions or impose import restrictions if it determines a U.S. trading partner is violating trade agreement commitments or engaging in discriminatory or unreasonable practices that burden or restrict U.S. commerce. |

|

International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) of 1977 |

Allows the President to regulate the importation of any property in which any foreign country or a national thereof has any interest if the President declares a national emergency to deal with an unusual and extraordinary threat, which has its source in whole or substantial part outside the United States, to the national security, foreign policy, or economy of the United States. |

Source: Trade Act of 1974 (P.L. 93-618, as amended), Trade Expansion Act of 1962 (P.L. 87-794, as amended), and International Emergency Economic Powers Act (P.L. 95-223, as amended).

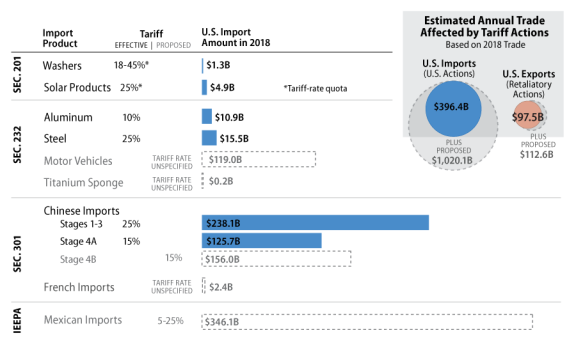

The multiple tariff increases applied to date, ranging from 10% to 45%, affect approximately 16% of U.S. annual imports. This amounts to $396.4 billion of imports using 2018 annual data (Figure 4). Section 301 tariffs on U.S. imports from China, which have been imposed in four successive stages to date, account for more than 90% of trade affected by the Administration's tariff actions. While the Administration has taken some steps to reduce the scale of imports affected by the tariffs since they were initially imposed in 2018 (e.g., by exempting Canada and Mexico from the steel and aluminum duties and creating processes by which certain products may be excluded), the general trend has been an escalation of tariff actions. Since May 2019, the Administration has increased existing tariffs on Chinese imports and broadened the scope of products covered; declared motor vehicle imports, particularly from Japan and the EU, a national security threat, granting the President authority to impose tariff increases on such imports; and proposed an additional 5%-25% on all imports from Mexico and tariffs on $2.4 billion of imports from France. In total, the existing and proposed actions would potentially affect over $1 trillion of U.S. imports, or 40% of the annual total. However, some de-escalation of tariff activity looks likely in the near term: the Administration indefinitely suspended its proposed stage 4B tariffs on Chinese imports, and announced a partial reduction in existing stage 4A tariffs as part of the Phase One Trade Deal with China, which the Administration signed on January 15.43

As tariffs act as a tax on foreign-produced goods, they distort price signals, potentially leading to less efficient consumption and production patterns, which may ultimately reduce U.S. and global economic growth rates. As of November 6, 2019, the United States collected $45.5 billion from the additional taxes paid by U.S. importers, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP).44 Increasing tariffs also creates a general environment of economic uncertainty, potentially dampening business investment and creating a further drag on growth. Estimates of the tariffs' overall economic effects vary, depending on modeling assumptions and the specific set of tariffs considered. Most studies, however, predict declines in GDP growth: the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that the tariffs in effect as of July 25, 2019, would lower U.S. GDP by roughly 0.3% by 2020 below a baseline without the tariffs;45 considering also more recent actions, the IMF estimated that the tariffs would reduce global GDP in 2020 by 0.8%.46 Preliminary analysis from researchers at the U.S. Federal Reserve Board finds that the tariffs have had a negative aggregate effect on the manufacturing sector with increased input costs more than offsetting gains to the sector resulting from increased protection from foreign competition.47

Many Members of Congress, U.S. businesses, farmers, interest groups, and trading partners, including major allies, have weighed in on the President's actions. While some U.S. stakeholders support the President's use of unilateral tariffs to the extent they result in a more level playing field for U.S. firms, many have raised concerns over their potential negative economic implications and impact on U.S. allies, the process for seeking exclusions to the tariffs, and the potential implications for the global trading system. Some Members of Congress also question whether the President's actions adhere to the intent of the trade laws used. Several Members have introduced legislation in the 116th Congress that would alter the President's current authorities, particularly Section 232, and Senator Charles E. Grassley, chair of the Senate Finance Committee, has expressed interest in considering such legislation in committee.48 The issue may be the subject of further debate and possible legislative activity in the second session of the 116th Congress.

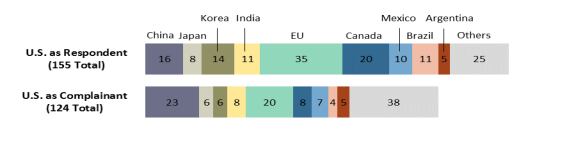

Trading Partner Retaliation and Countermeasures

Increasing U.S. tariffs or imposing other import restrictions potentially opens the United States to complaints that it is violating its World Trade Organization and free trade agreement (FTA) commitments. In response to the U.S. unilateral tariff actions, several U.S. trading partners, including China and the European Union, have initiated dispute settlement proceedings, which are now at various stages in the WTO dispute settlement process.49 Multiple countries have also imposed retaliatory tariffs, most in the range of 5%-25%, and the United States has similarly responded by initiating additional dispute settlement measures at the WTO, arguing that the retaliatory measures do not adhere to WTO commitments. Some analysts argue that this escalating series of unilateral tariff actions, retaliations, and resulting WTO disputes may threaten the stability of the multilateral trading system, given the political sensitivity of a potential WTO panel ruling on issues related to national security (Section 232) and the possibility of countries potentially disregarding WTO rulings not in their favor.50

Economically, retaliation amplifies the potential negative effects of the U.S. tariff measures. It broadens the scope of U.S. industries potentially harmed by making targeted U.S. exports less competitive in foreign markets. U.S. exports of targeted industries have declined, with U.S. agricultural exports subject to retaliation down 27% in 2018 compared to 2017.51 Five U.S. trading partners currently impose retaliatory tariffs affecting approximately $9 billion of U.S. annual exports in response to Section 232 actions, while China has imposed retaliatory tariffs in response to Section 301 actions affecting more than $91 billion of U.S. annual exports (Figure 5). As part of the U.S.-China Phase One trade deal, China suspended planned increases in its retaliatory tariffs and committed to increase purchases of various U.S. exports, including agricultural products. The products affected by retaliation to date cover a range of U.S. industries, but the largest export categories include soybeans, pork, whiskies, wood products, steel, and aluminum. Lost market access resulting from the retaliatory tariffs may compound concerns that U.S. exporters increasingly face higher tariffs than some competitors in foreign markets, as other countries proceed with trade liberalization agreements, such as the EU-Japan FTA, which do not include the United States.

U.S.-China Economic Issues52

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS with data from U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). |

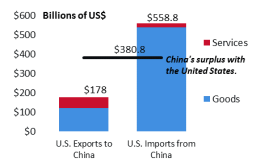

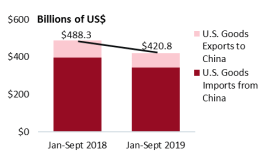

The U.S.-China economic relationship has expanded significantly over the past three decades. In 2018, China was, in terms of goods, the largest U.S. trading partner (with total trade more than $730 billion), the third-largest U.S. export market (at $120 billion), and the largest source of U.S. imports (at $540 billion) (Figure 6).53 China is the second-largest foreign holder of U.S. Treasury securities, at $1.11 trillion as of June 2019.54

Against the backdrop of growing commercial ties, U.S. concerns about China's trade and investment policies, business practices, and asymmetries in the bilateral commercial relationship have been building over the past decade. The Chinese government's unwillingness to acknowledge and address priority U.S. concerns, while Chinese firms expand their activities in the United States and globally, has highlighted uneven levels of market openness, divergent approaches to global rules, and significant differences in the operating conditions and tenets of the U.S. and Chinese economic systems. These differences relate to foundational elements of the U.S. market-based system that are lacking in China, including a clear separation of government and business roles, freedom of information and expression, protections of privacy and intellectual property rights (IPR), and the rule of law that is created to protect individual rights, not the interests and power of the ruling party or government. Problems that individual companies have faced in China for some time are now coalescing and intensifying—particularly with the emergence of new technologies such as 5G and artificial intelligence—in ways that are raising U.S. government concerns about the broader effects of Chinese commercial behavior on U.S. economic competitiveness and national security.

China's Trade Practices

U.S. concerns relate primarily to the Chinese state's increasingly direct and powerful role in the economy through a web of reinforcing industrial policies, government funding, and the influence of the Chinese government and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in corporate decision-making. Of particular concern are China's industrial policies requiring U.S. firms to disclose and transfer proprietary operational and technical information and intellectual property, often in areas where U.S. firms are global leaders, as a precondition to operate in China. Other developments feeding U.S. concerns include:

An uptick in reports of Chinese corporate espionage;

China's use of access to U.S. universities to conduct political operations and participate in American research and development in emerging technologies;

China's tightening of information controls (and pressure on U.S. firms to abide by these controls);

China's use of tit-for-tat retaliation and economic coercion against U.S. businesses, and;

New Chinese policies incentivizing the transfer of advanced civilian technical capabilities to the military (including capabilities obtained from U.S. firms).

China's Global Expansion

China's rapid commercial expansion offshore is raising concerns among many observers about unfair business practices, such as government subsidies and lack of reciprocal market access, global overcapacity,55 and China's potential to challenge U.S. global economic leadership. Some in Congress are concerned that China's use of concessional lending is advancing Chinese state firms at the expense of private enterprise and potentially economically weakening host governments while promoting authoritarian trends overseas.56 China's One Belt One Road (OBOR) program aims to promote economic integration for China around the world through new infrastructure—including energy, financial, ICT, and transportation—that is invested, controlled and increasingly vertically integrated into Chinese supply chains.57 The effort leans heavily on standards interoperability to connect Chinese projects across regions and globally. While China has released little official information on overseas lending and investment, a review of available information shows that almost all of China's overseas lending and investment activities are undertaken by the Chinese government, state-owned companies or state banks. There appears to be a split among experts who seek to improve the terms and quality of China's investment as the main concern and those who seek to restrict cooperation because of the strategic implications of connectivity and interoperability across the energy, ICT, and transportation projects that China is building around the world.

As Chinese companies expand into global markets, Beijing is looking to dilute or change global rules that challenge its state-led economic model and advance new rules, principles, and standards that could legitimize and protect China's model from challenge and, particularly in the area of technical standards, pave the way for new business opportunities from Chinese firms who benefit from the ability to build and operate against indigenous standards introduced on the bilateral, multilateral or global level. China has adopted a technical approach in assuming leadership of key multilateral functional organizations and introducing policies and standards in these obscure but influential bodies, including the International Standards Organization (ISO) and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). If Chinese standards proliferate across global markets—particularly Chinese standards in 5G and other technologies—the competitive advantage of many U.S. exporters could erode.58

U.S. Policy Response

The Trump Administration has undertaken a number of policy actions to begin to address these issues. In March 2018, the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) concluded under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 (19 U.S.C. §2411) that four Chinese trade practices justified U.S. action: forced technology transfer requirements, cyber-enabled theft of U.S. IPR and trade secrets, discriminatory and nonmarket licensing practices, and state-funded strategic acquisition of U.S. companies.59 In response to these findings, the Trump Administration, over the course of four rounds, increased import tariffs on about $360 billion of Chinese imports. China, in response, raised tariffs on more than $90 billion worth of U.S. products. As the United States and China have increased tariffs since 2018, bilateral trade flows decreased in the first three quarters of 2019 (Figure 7).60

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS with data from U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). |

The Trump Administration announced in December 2019 a draft Phase One trade deal with the Chinese government on a subset of U.S. concerns, including some aspects of IPR, technology transfer, agriculture, financial services, exchange rates, and dispute resolution. As part of this agreement, which was signed on January 15, 2020, the Administration has indefinitely suspended its proposed stage 4B tariffs on U.S. imports from China and announced a partial reduction in existing stage 4A tariffs in return for China committing to purchase an additional $200 billion of U.S. agriculture, energy, and manufacturing goods over the next two years. The deal is a first step that appears to leave tough systemic issues on IP, technology transfer, and state subsidies to phase two talks. U.S. firms facing tariffs that remain in place are concerned about the effects on their businesses.61 Meanwhile, Beijing appears to have preserved space to implement industrial policies in strategic sectors of concern to the United States and may delay phase two talks to gain time to implement new government programs to support sectors such as advanced manufacturing.

The Administration, in response to legislation, strengthened U.S. investment review and export control authorities, stepped up efforts to stem Chinese economic espionage, and sanctioned specific Chinese firms for violations of U.S. sanctions and the theft of U.S. IPR. The Administration placed additional restrictions on U.S. technology that may have the potential for "dual use" in China's civilian and military sectors, as well as surveillance technology used by Chinese authorities in the western Chinese region of Xinjiang.The Administration has also taken steps to confront China globally. Administration officials have tried to reform China's behavior and role in international organizations, including China's status as a developing country in the World Bank, the WTO, and the International Postal Union (IPU), which affords China certain preferential terms. The Administration has worked diplomatically to discourage countries from signing below par infrastructure agreements with China and to emphasize the security risks of including Chinese suppliers in their domestic 5G information communications technology (ICT) systems. To provide project finance alternatives to China, the Administration, in collaboration with Congress, created the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation and a Blue Dot infrastructure network to promote collaborative project finance among Australia, Japan, and the United States.62

In its second session, the 116th Congress continues to face these China-related concerns on a range of fronts and is positioned to provide oversight of the Administration's implementation of new policies, respond to potential gaps and counter effects of current policies, and call for a comprehensive look at the broader policy challenges with China to identify what new authorities and approaches may be needed. There appears to be bipartisan consensus about the imperative of sustained policy attention to address China-related concerns. In addition to monitoring the status of bilateral trade talks, Congress may consider the following issues:

- Search for new policy options to address China's continued use of industrial policies and subsidies;

- Examine how best to address a perceived lack of transparency, accountability, and legal recourse involving Chinese firms listed on stock exchanges in the United States;

- Exercise oversight to assess the effectiveness of new U.S. investment security review and export control authorities and address potential gaps;

- Examine U.S. 5G infrastructure exposure to Chinese firms other than Huawei and emerging technology sectors beyond telecommunications (e.g., messaging apps, fintech);

- Explore opening U.S. FTA talks with Taiwan and assess Taiwan's central role in both U.S. and China's microelectronics supply chains; and

- Exercise oversight authorities to monitor and sanction China's activities of concern in multilateral development banks and international financial institutions.

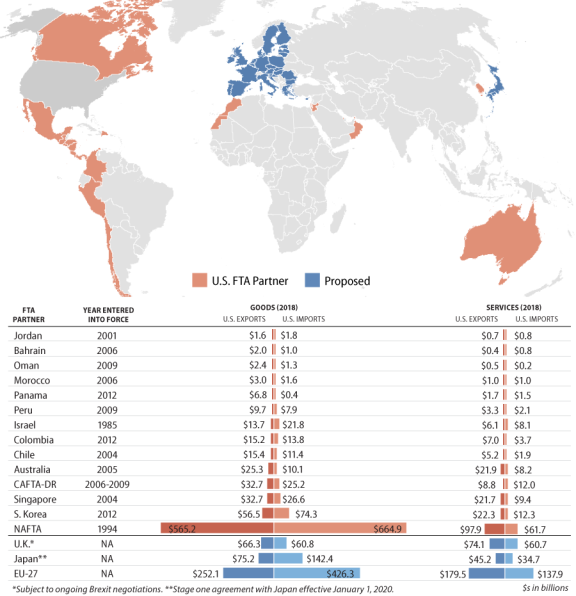

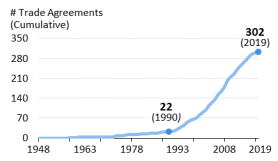

U.S. Trade Agreements and Negotiations63

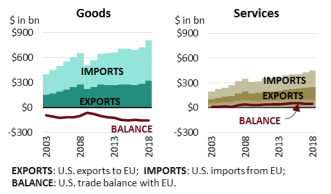

In addition to multilateral efforts through the World Trade Organization, the United States has worked to reduce and eliminate barriers to trade and create nondiscriminatory rules and principles to govern trade through bilateral and regional trade agreements.64 Over the past two decades, these agreements, generally referred to as free trade agreements (FTAs) in the U.S. context, have proliferated globally in part due to difficulty in reaching consensus on new agreements at the WTO. In total, the United States has implemented 14 comprehensive FTAs with 20 countries since 1985, when the first bilateral FTA was concluded with Israel (Figure 8).

Trade agreements have been a top priority of the Trump Administration and the issue is likely to be a continued focus during the second session of the 116th Congress. After withdrawing the United States from the 12-member Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2017, which had been signed but not ratified during the Obama Administration, President Trump initiated new negotiations with the three largest economies and biggest U.S. trade partners among the TPP members—Canada, Mexico, and Japan. The new United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, if ratified by the government of Canada, would replace the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the largest existing U.S. FTA. Legislation to implement and bring into force USMCA, signed in 2018, passed the House of Representatives in December 2019 and the Senate in January 2020. The Administration has taken a staged approach to negotiations with Japan, signing two initial agreements on limited tariff reductions and digital trade in 2019, with more extensive negotiations to follow. Due to their limited scope, the Administration enacted the initial agreements with Japan, as well as minor revisions to the U.S.-South Korea (KORUS) FTA,65 using delegated tariff authorities, without formal approval or action by Congress. These actions have elicited debate among Members over the appropriate congressional role in the negotiation and implementation of partial scope free trade agreements, which is likely to continue in the second session.

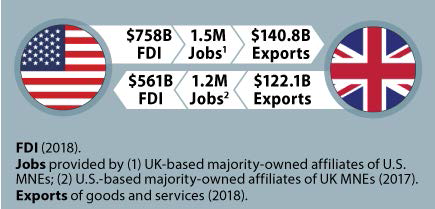

Looking forward, several new trade agreement negotiations may begin during the second session of the 116th Congress. The Administration expects to start talks toward a more comprehensive second stage agreement with Japan in early 2020, and notified Congress under Trade Promotion Authority of its intent to negotiate trade agreements with the European Union and the United Kingdom (UK). Such efforts, however, have been complicated by the ongoing Brexit negotiations and differing U.S. and EU views on their appropriate scope.66 The Administration has also informally expressed interest in new trade negotiations with a number of countries, including Brazil.67 Congress is expected to weigh in on the scope and objectives for any new agreements throughout the negotiating process, especially through the TPA negotiating objective and requirements for the Executive Branch to conduct ongoing consultations before, during, and after the completion of the negotiations. Congress may also advise the Administration on congressional priorities for potential trade agreement partners.68

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS with data from the U.S. Department of Commerce's Census Bureau and Bureau of Economic Analysis. Notes: Note: EU-27 excludes trade with United Kingdom. |

Core Provisions in U.S. Trade Agreements69

U.S. free trade agreements (FTAs) generally are negotiated on the basis of U.S. trade negotiating objectives established by Congress under Trade Promotion Authority.70 Since the 1980s, U.S. FTAs have evolved in the scope and depth of their commitments.71 The first U.S. bilateral FTA was with Israel. It was14 pages in length and focused primarily on the elimination of tariffs. In subsequent agreements, the United States pursued increasingly comprehensive and high-standard, enforceable commitments. NAFTA, which entered into force in 1994, was the first FTA that incorporated groundbreaking rules included in subsequent U.S. FTAs. It initiated a new generation of U.S. trade agreements in the Western Hemisphere and other parts of the world, influencing negotiations in areas such as market access, rules of origin, intellectual property rights (IPR), foreign investment, and dispute resolution. NAFTA was the first trade agreement to include provisions on IPR protection, labor, and the environment. Although not all FTAs are identical, core provisions incorporated into most U.S. FTAs include the following:

- Tariffs and Market Access. Gradual elimination of most tariffs and nontariff barriers on goods, services, and agriculture, and specific rules of origin requirements.

- Services. Commitments on national treatment, most-favored nation (MFN) treatment, and prohibition of local presence requirements.

- IPR Protection. Minimum standards of protection and enforcement for patents, copyrights, trademarks, and other forms of IPR. FTAs after NAFTA have new commitments, reflecting standard protection similar to that found in U.S. law.

- Foreign Investment. Removal of investment barriers, basic protections for investors, with exceptions, and mechanisms for dispute settlement.

- Labor and Environmental Provisions. NAFTA's commitments for each party to enforce their own laws evolved in later FTAs to commitments to adopt, maintain, and not derogate from laws incorporating specific standards, among other provisions.

- Government Procurement. Commitments to provide certain levels of access to and nondiscriminatory treatment in parties' government procurement markets.

- Dispute Settlement. Provisions for dispute settlement mechanism to resolve disputes regarding each party's adherence to agreement obligations.

- Other Provisions. Other core provisions have included those related to competition policy, monopolies, and state enterprises, sanitary and phytosanitary standards, safeguards, technical barriers to trade, transparency, and good governance.

The governments of all parties generally must ratify an FTA before it can enter into force. In the United States, Congress must pass legislation to implement any part of an FTA that requires a change in U.S. law. Before voting on an agreement, Congress may review whether progress was made in achieving the negotiating objectives it established in TPA legislation. Congress may also evaluate the overall economic effect on the U.S. economy, including through a mandated report by the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC), determine whether the agreement would promote U.S. standards such as IPR, labor, and the environment in other countries, or consider the level of commitments and enforceability of the agreement and its rules.

U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA)72

|

NAFTA and USMCA Fast Facts Significant Dates

Proposed USMCA: Retains most of NAFTA's chapters with new, updated or revised provisions on rules of origin for motor vehicle and agricultural products, IPR protection, digital trade, investment, dispute settlement, services, labor and the environment, state-owned enterprises, currency misalignment, and periodic review of the agreement. |

On November 30, 2018, President Trump and the leaders of Canada and Mexico signed the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, a proposed trilateral free trade agreement that, if ratified by all governments, would revise and modernize the North American Free Trade Agreement. Pursuant to Trade Promotion Authority, the Administration notified Congress on August 31, 2018 of its intention to sign the agreement, in part to allow for the signing of the agreement prior to Mexico's president-elect Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador taking office on December 1. Mexico became the first party to ratify the agreement on June 17, 2019. On December 13, the Trump Administration submitted to Congress the proposed USMCA implementing legislation, which reflects recent amendments negotiated by some Members of Congress and the USTR. On the same day, the United States-Mexico-Canada Implementation Act (H.R. 5430) was introduced in the House of Representatives. On December 16, the companion bill was introduced in the Senate (S. 3052). H.R. 5430 was passed by the House on December 19, 2019, and by the Senate on January 16, 2020.

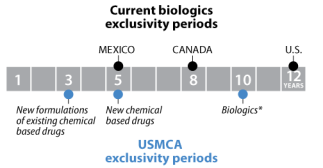

The 116th Congress debate on USMCA centered on whether USMCA advanced TPA negotiating objectives, the enforceability of labor and environmental provisions, the extent to which Mexico implements its labor reform commitments under USMCA, and the affordability of biologics under the proposed intellectual property rights (IPR) provision.73 Other congressional concerns included the economic effects of the agreement, the implications for U.S. trade policy in areas in which USMCA scales back NAFTA commitments, such as motor vehicle rules of origin (ROO) and investor state dispute settlement provisions, and political implications if the agreement was not approved by Congress or if President Trump moved forward on his threat to withdraw from NAFTA.

Many trade policy experts and economists give credit to FTAs such as NAFTA for expanding trade and economic linkages among countries, creating more efficient production processes, increasing the availability of lower-priced consumer goods, and improving living standards and working conditions. Other proponents contend that NAFTA has political dimensions that create positive ties within North America and improve democratic governance. At the same time, some policymakers, labor groups, and consumer advocacy groups argue that NAFTA has had a negative effect on U.S. jobs and wages. They often refer to labor provisions as being weak and maintained that the proposed USMCA should have stronger, more enforceable labor provisions to address issues such as outsourcing, lower wages, and job dislocation.

The USMCA, comprised of 34 chapters and 12 side letters, retains most of NAFTA's chapters, including the elimination of tariff and nontariff trade barriers, while making notable changes to ROO for motor vehicle and agriculture products and modernizing provisions on IPR, digital trade, and services trade. The agreement also allows some greater access to the Canadian dairy market to U.S. dairy producers and adds new obligations on currency misalignment, a new chapter on state-owned enterprises, and a new chapter on anti-corruption. Other USMCA provisions that are new to U.S. FTAs include: a sunset clause provision, which requires a joint review and agreement on renewal issues after six years, revised provisions on government procurement and investment, and a provision that allows a party to withdraw from the agreement if another party enters into an FTA with a country it deems to be a nonmarket economy (e.g., China).

During the negotiations, the Trump Administration's proposals on ROO in motor vehicle products were among the more contentious issues. Under NAFTA, the ROO requirement for autos, light trucks, engines, and transmissions is 62.5%; for all other vehicles and parts, it is 60%. USMCA raises these requirements to 75% of a motor vehicle's content and to 70% of its steel and aluminum content. It requires that 70% of a motor vehicle's steel and aluminum must originate (melted and poured) in North America by years seven (for aluminum) and ten (for steel) of its entry into force. It also adds a wage requirement, for the first time in any FTA, stating that 40%-45% of auto content must be made by workers earning at least $16 per hour.

Supporters of the proposed USMCA contend that the agreement modernizes NAFTA by including updated provisions in areas such as digital trade and financial services. Some analysts believe that the updated auto ROO requirements contained in the USMCA could raise compliance and production costs and lead to higher prices, which could possibly negatively affect U.S. vehicle sales. Overall, the full economic effects of the proposed USMCA likely would not be significant because nearly all U.S. trade with Canada and Mexico is now conducted duty and barrier free.74 Many economists and other observers believe that it is not expected to have a measurable effect on United States-Mexico trade and investment, jobs, wages, or overall economic growth, and that it would probably not have a measurable effect on the U.S. trade deficit with Mexico.75

Core issues at the center of the USMCA congressional debate were some policymakers' concerns over effective dispute settlement provisions, enforcement of labor and environmental provisions, the enforceability of Mexico's labor reforms, and IPR protections for biologic drugs, which are large-molecule drugs developed from living organisms. The USTR and some Members of Congress negotiated proposed changes to the USMCA to address congressional concerns. USTR then negotiated the amendments with USMCA parties. On December 10, 2019, the United States, Canada, and Mexico agreed to a protocol of amendment to the proposed USMCA, which includes modifications to key elements of the original text in regard to dispute settlement, labor and environmental provisions, IPR, and steel and aluminum requirements in the motor vehicle ROO. Mexico was the first country to approve the amendments by a 107-1 vote in the Mexican Senate on December 12. The agreement awaits ratification by the government of Canada.

U.S.-Japan Trade Negotiations76

|

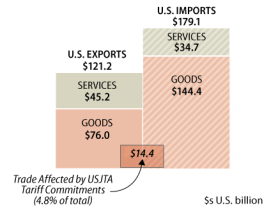

Figure 9. U.S.-Japan Bilateral Trade (2018) |

|

|

Source: Figure created by CRS with data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, USTR, USJTA Tariff Schedules. |

On October 7, 2019, after six months of formal negotiations, the United States and Japan signed two trade agreements covering market access for industrial and agricultural goods and rules on digital trade.77 The market access agreement would reduce or eliminate tariffs on approximately $14.4 billion or 5% of bilateral trade ($7.2 billion each of U.S. imports and exports) (Figure 9). USTR has referred to the digital trade commitments as "most comprehensive and high-standard trade agreement" negotiated.78 These agreements constitute what the Trump and Abe Administrations envision as the "first stage" of a broader trade negotiation, and the two sides intend to continue talks on a more comprehensive deal in coming months.79 In a departure from past U.S. FTA practice, Congress did not have a formal role in approving the agreements as the Trump Administration used delegated tariff proclamation authorities under TPA to enact the tariff changes and no other changes to U.S. laws were required. The digital trade commitments, which did not require changes to U.S. law, are in the form of an Executive Agreement. Japan's Diet, however, needed to ratify the pact, and did so on December 5, 2019, paving the way for the agreements to enter into force on January 1, 2020.

A major motivation for the Trump Administration to pursue these initial agreements was Japan's recent conclusion of other FTAs with major trading partners. In particular, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP or TPP-11) and the Japan-EU FTA had weakened the competitive position of U.S. exporters. The U.S.-Japan deal will put most U.S. agriculture exporters on par with Japan's other trading partners in terms of tariffs, but the agreement excludes most other goods from the tariff commitments and does not cover market access for services, rules beyond digital trade, or nontariff barriers. Notably, the agreement does not cover trade in autos, an industry accounting for one-third of U.S. imports from Japan. Japan's decision to participate in bilateral talks came after President Trump threatened to impose additional auto tariffs on Japan, based on national security concerns.