U.S. and Global Trade Agreements: Issues for Congress

Congress plays a prominent role in shaping, debating, and approving legislation to implement trade agreements, and over the past three decades, bilateral and regional trade agreements (RTAs, or free trade agreements (FTAs) in the U.S. context) have become a primary source of new international trade liberalization commitments. The United States has historically pursued FTAs to open markets for U.S. goods, services, and agriculture, and establish trade rules and disciplines to enhance overall domestic and global economic growth. They are actively debated and can be contentious due to concerns over the potential employment effects of greater import competition, among other reasons.

RTAs are reciprocal preferential arrangements among two or more parties. Their content has evolved significantly, partly as a result of change in the international economy where new trade barriers have been erected and/or where RTAs may provide a testing ground for new trade rules for potential future multilateral agreement. The United States historically has aimed for comprehensive coverage in eliminating barriers to trade and addressing all sectors in its FTAs. In addition to the reduction and elimination of tariffs and more traditional nontariff trade barriers, U.S. FTAs also cover services trade, enhance intellectual property rights (IPR), provide investment protections, and include enforceable labor and environmental commitments. Some countries pursue more limited agreements—only half of RTAs worldwide cover services and they rarely include labor and environmental provisions.

Congressional interest in U.S. and global RTAs stems from their potential economic and foreign policy implications, implementation issues, and Congress’ role in establishing U.S. trade policy (Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution grants Congress authority to regulate foreign commerce). In its 2015 grant of Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), Congress set specific negotiating objectives for U.S. trade agreements that must be advanced in order for Congress to provide expedited consideration to the implementing legislation needed to bring new agreements into force. TPA is scheduled to be in effect through July 2021, unless Congress, before July 1, 2018, enacts an extension disapproval resolution regarding the Administration’s recently submitted extension request.

Since 1990, the number of RTAs in force globally has grown six-fold from fewer than 50 to nearly 300. All 164 members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) are now party to at least one RTA; as of 2014 each member had on average 11 RTA partners. The United States began negotiating FTAs in the 1980s, and as of 2018, is party to 14 such agreements involving 20 trading partners. The multilateral trading system, meanwhile, has not produced a broad set of new trade liberalization agreements (excluding more limited scope agreements, such as the Trade Facilitation Agreement) since the Uruguay Round, which also established the WTO in 1995.

In the current environment of stalled multilateral negotiations, RTAs provide an alternative venue to pursue trade liberalization and establish new rules on emerging issues. RTAs are, however, inherently discriminatory given their limited membership (i.e., they provide preferential treatment to some countries and not others), leading to debate over their global economic effect and whether they serve to facilitate future multilateral agreements or lead to the creation of competing trade blocs. U.S. exporters benefit from the preferential aspects of FTAs when they gain better access to FTA partner markets than their foreign competitors, but may be similarly harmed when third parties negotiate agreements that do not include the United States.

To date there are no RTAs in force between the world’s largest economies (China, Japan, European Union (EU), and the United States). This could change in the near future as these and other major U.S. trading partners are involved in several pending RTAs, including an ongoing negotiation between 16 Asian nations that involves both China and Japan, and two recently concluded but not yet ratified and implemented RTAs: the EU-Japan agreement (one of twelve pending EU RTAs) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

In some ways, the United States has pulled back from its recent FTA policy. Under the Obama Administration, the United States pursued two major regional FTA negotiations, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) including Japan and 10 other Asia-Pacific nations, and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP) with the European Union. These FTAs would have nearly doubled the share of U.S. trade occurring with FTA partners. The Trump Administration, however, has criticized existing FTAs, withdrawn the United States from the concluded but not enacted TPP, placed the T-TIP negotiations on hold, and initiated renegotiation or modification of the largest U.S. FTAs with Canada, Mexico, and South Korea. The Administration has also stated its intent to negotiate future FTAs on a bilateral rather than multi-party basis.

As other countries move forward with new RTA negotiations that cover a significant share of world trade, a number of issues arise that may be of interest to Congress, including how these agreements will affect U.S. economic and strategic interests, their impact on U.S. leadership in trade liberalization efforts and establishing new trade rules, and the appropriate U.S. response.

U.S. and Global Trade Agreements: Issues for Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Overview

- Relationship to WTO

- WTO Rules on RTAs

- Debate over RTAs and Multilateral System

- Economic Effects

- Influence on the Multilateral System

- U.S. Free Trade Agreements (FTAs)

- Evolution of U.S. FTA Negotiations, Objectives, and Strategies

- Trump Administration FTA Policy and Recent Developments

- Content of U.S. FTAs

- Trade Trends under U.S. FTAs

- U.S. Trade Shares with FTA Partners

- Bilateral Trade Balances with FTA Partners

- Top Goods and Services Trade with FTA Partners

- Utilization Rates of U.S. FTAs (U.S. Imports)

- Global RTAs

- Global Growth in RTAs

- Rise of Mega-Regional Negotiations

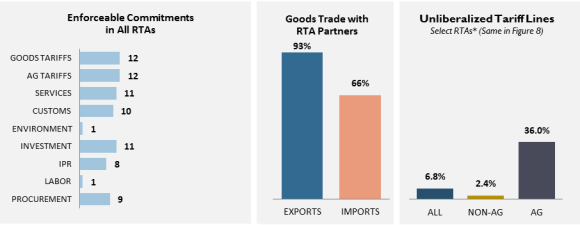

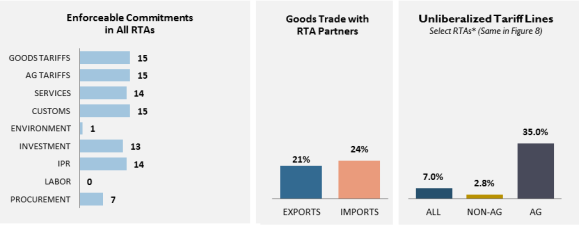

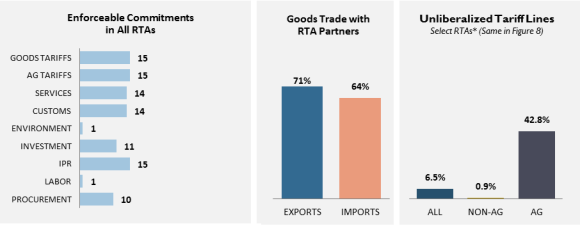

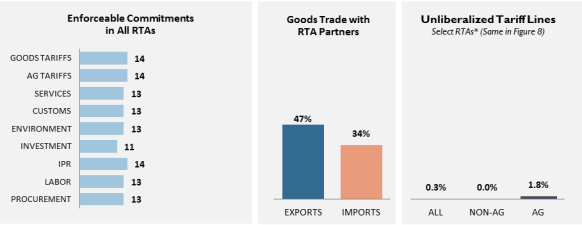

- Comparison of Provisions

- Extent of Tariff Liberalization

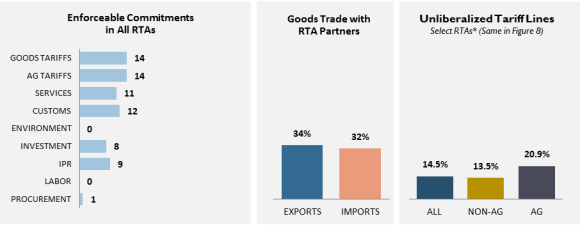

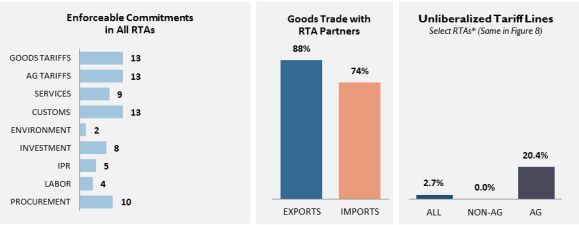

- Strength and Scope of Commitments

- Differing Approaches

- Potential for Discriminatory Treatment Affecting U.S. Trade

- Major U.S. Trade Partners' RTAs

- European Union

- China

- Canada

- Mexico

- Japan

- South Korea

- United States

- Issues for Congress

Figures

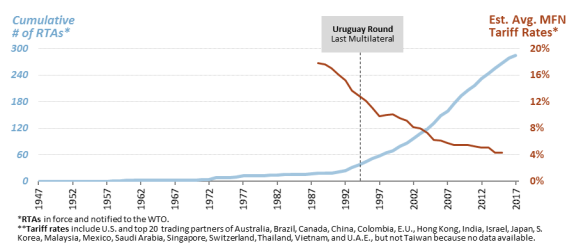

- Figure 1. RTAs and Average Tariff Rates

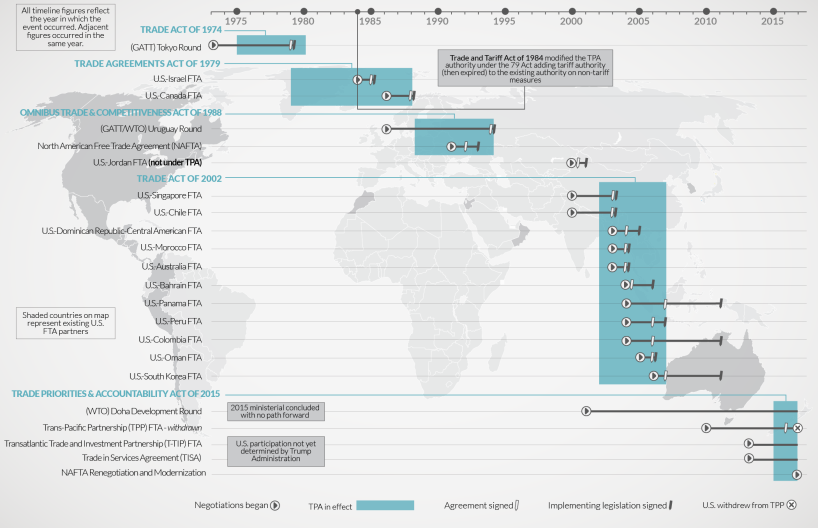

- Figure 2. Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) and U.S. Trade Agreements

- Figure 3. Shares of U.S. Total Trade with WTO and FTA Partners

- Figure 4. U.S. Trade Balances with FTA Partners

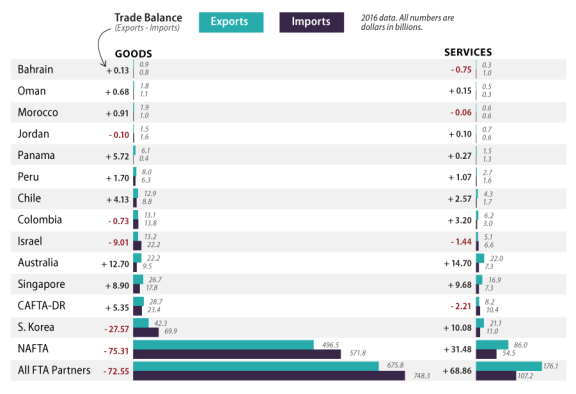

- Figure 5. U.S. Total Goods and Services Trade Balance with FTA Partners

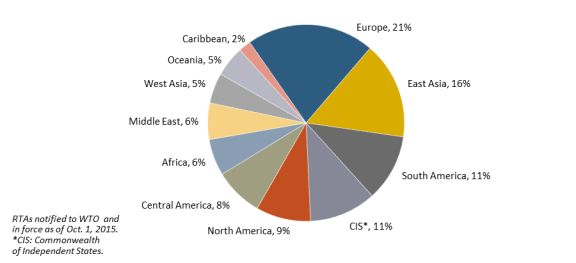

- Figure 6. RTAs by Region

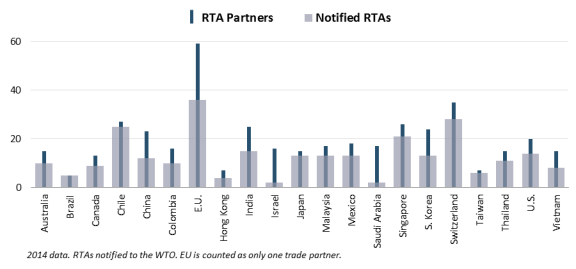

- Figure 7. RTAs of United States and Top 20 U.S. Trade Partners

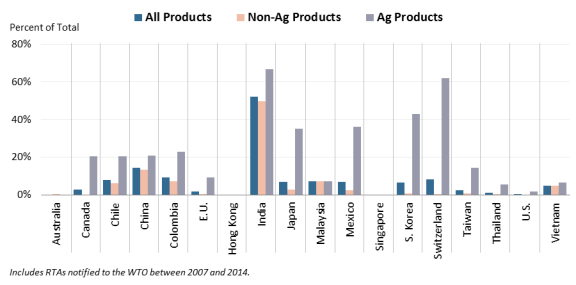

- Figure 8. Tariff Lines Not Eliminated in RTAs for Top 20 U.S. Trade Partners

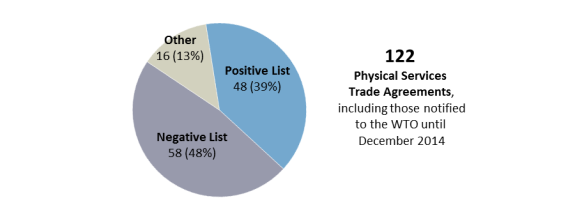

- Figure 9. Breakdown of Global Services RTAs by Type

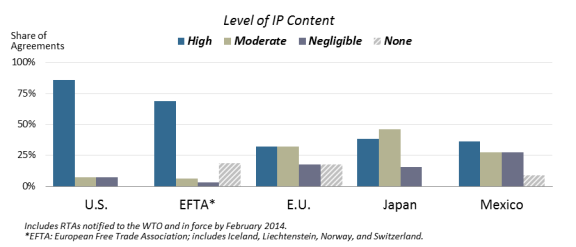

- Figure 10. Shares of Trade Agreements by Level of IP Content, Select Trade Partners

Tables

- Table 1. U.S. Goods Trade with Top FTA Partners

- Table 2. U.S. Services Trade with Top FTA Partners

- Table 3. U.S. Imports from FTA Partners Receiving Preferential Tariff Treatment

- Table 4. Selected Comparative Data on U.S. Exports to Major Trade Partners with RTAs that exclude the United States

- Table 5. European Union RTAs

- Table 6. China's RTAs

- Table 7. Canada's RTAs

- Table 8. Mexico's RTAs

- Table 9. Japan's RTAs

- Table 10. South Korea's RTAs

- Table 11. U.S. FTAs

Summary

Congress plays a prominent role in shaping, debating, and approving legislation to implement trade agreements, and over the past three decades, bilateral and regional trade agreements (RTAs, or free trade agreements (FTAs) in the U.S. context) have become a primary source of new international trade liberalization commitments. The United States has historically pursued FTAs to open markets for U.S. goods, services, and agriculture, and establish trade rules and disciplines to enhance overall domestic and global economic growth. They are actively debated and can be contentious due to concerns over the potential employment effects of greater import competition, among other reasons.

RTAs are reciprocal preferential arrangements among two or more parties. Their content has evolved significantly, partly as a result of change in the international economy where new trade barriers have been erected and/or where RTAs may provide a testing ground for new trade rules for potential future multilateral agreement. The United States historically has aimed for comprehensive coverage in eliminating barriers to trade and addressing all sectors in its FTAs. In addition to the reduction and elimination of tariffs and more traditional nontariff trade barriers, U.S. FTAs also cover services trade, enhance intellectual property rights (IPR), provide investment protections, and include enforceable labor and environmental commitments. Some countries pursue more limited agreements—only half of RTAs worldwide cover services and they rarely include labor and environmental provisions.

Congressional interest in U.S. and global RTAs stems from their potential economic and foreign policy implications, implementation issues, and Congress' role in establishing U.S. trade policy (Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution grants Congress authority to regulate foreign commerce). In its 2015 grant of Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), Congress set specific negotiating objectives for U.S. trade agreements that must be advanced in order for Congress to provide expedited consideration to the implementing legislation needed to bring new agreements into force. TPA is scheduled to be in effect through July 2021, unless Congress, before July 1, 2018, enacts an extension disapproval resolution regarding the Administration's recently submitted extension request.

Since 1990, the number of RTAs in force globally has grown six-fold from fewer than 50 to nearly 300. All 164 members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) are now party to at least one RTA; as of 2014 each member had on average 11 RTA partners. The United States began negotiating FTAs in the 1980s, and as of 2018, is party to 14 such agreements involving 20 trading partners. The multilateral trading system, meanwhile, has not produced a broad set of new trade liberalization agreements (excluding more limited scope agreements, such as the Trade Facilitation Agreement) since the Uruguay Round, which also established the WTO in 1995.

In the current environment of stalled multilateral negotiations, RTAs provide an alternative venue to pursue trade liberalization and establish new rules on emerging issues. RTAs are, however, inherently discriminatory given their limited membership (i.e., they provide preferential treatment to some countries and not others), leading to debate over their global economic effect and whether they serve to facilitate future multilateral agreements or lead to the creation of competing trade blocs. U.S. exporters benefit from the preferential aspects of FTAs when they gain better access to FTA partner markets than their foreign competitors, but may be similarly harmed when third parties negotiate agreements that do not include the United States.

To date there are no RTAs in force between the world's largest economies (China, Japan, European Union (EU), and the United States). This could change in the near future as these and other major U.S. trading partners are involved in several pending RTAs, including an ongoing negotiation between 16 Asian nations that involves both China and Japan, and two recently concluded but not yet ratified and implemented RTAs: the EU-Japan agreement (one of twelve pending EU RTAs) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

In some ways, the United States has pulled back from its recent FTA policy. Under the Obama Administration, the United States pursued two major regional FTA negotiations, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) including Japan and 10 other Asia-Pacific nations, and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP) with the European Union. These FTAs would have nearly doubled the share of U.S. trade occurring with FTA partners. The Trump Administration, however, has criticized existing FTAs, withdrawn the United States from the concluded but not enacted TPP, placed the T-TIP negotiations on hold, and initiated renegotiation or modification of the largest U.S. FTAs with Canada, Mexico, and South Korea. The Administration has also stated its intent to negotiate future FTAs on a bilateral rather than multi-party basis.

As other countries move forward with new RTA negotiations that cover a significant share of world trade, a number of issues arise that may be of interest to Congress, including how these agreements will affect U.S. economic and strategic interests, their impact on U.S. leadership in trade liberalization efforts and establishing new trade rules, and the appropriate U.S. response.

Introduction

Congress plays a central role in the negotiation, approval and implementation of U.S. trade agreements, reflecting its constitutional authority over foreign commerce.1 Congress shapes the Administration's trade agreement negotiations through enacting statutory U.S. trade negotiating objectives, ongoing consultations and oversight, and ratification of concluded agreements through implementing legislation. It also oversees trade agreement implementation and the enforcement of commitments.2 U.S. trade agreements can affect many facets of U.S. economic activity, including the cost and availability of goods and services in the United States, the competitiveness of U.S. firms both domestically and abroad, employment opportunities for U.S. workers, as well as broader U.S. strategic interests. The Trump Administration has altered U.S. trade agreement policy by withdrawing from the then-pending Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), starting renegotiations or modification of two existing free trade agreements (FTAs), and stating a preference for bilateral FTAs. It also has put forth a more skeptical approach toward multilateral trade agreements under the World Trade Organization (WTO), and has viewed bilateral trade imbalances as a measure of trade agreement success or failure. As Congress works with the Trump Administration in establishing and implementing U.S. trade policy, it may have interest in more closely examining the implications of the type and content of U.S. trade agreements and those pursued by major U.S. trading partners that exclude the United States.

Key questions to consider may include

- how other countries' trade agreements may affect U.S. economic and strategic interests and negotiating priorities;

- the influence of bilateral and regional agreements on broader international commercial norms and their impact on the multilateral trading system;

- the role of the United States in international trade agreement negotiations;

- whether the United States should pursue new trade agreement negotiations and if so how to prioritize potential partners; and

- the costs and benefits of bilateral versus multi-party or regional negotiating approaches.

To help inform this debate, this report analyzes bilateral and regional trade agreements, including a discussion of the relation between these types of agreements and broader multilateral negotiations. It also provides information on existing U.S. FTAs and their evolution over time. As other countries' trade agreement policies and negotiations may affect the costs and benefits of various U.S. approaches, it also looks at non-U.S. regional trade agreements (RTAs), and the specific RTA regimes of the top six U.S. trading partners: the European Union, China, Canada, Mexico, Japan, and South Korea.3 The report concludes with a discussion of potential issues for Congress by addressing key policy questions.

Overview

In the United States and internationally, trade agreements have changed considerably over the past 70 years, both in the types of agreements negotiated and their content. Those decades saw the creation, prevalence, and then relative stagnation of the multilateral trading system as the primary venue for the negotiated removal of barriers to international trade. Bilateral and now large regional (so-called mega-regional) trade liberalization agreements have become increasingly prominent, especially in the last two decades.4 Meanwhile, tariff barriers have fallen considerably in the United States and globally as a result of multilateral, bilateral/regional, and unilateral liberalization (Figure 1). As tariffs have become less economically significant, trade agreements have increasingly expanded their content coverage, with more recent agreements including provisions on issues such as worker rights and environmental protections, investment commitments, and enhanced standards for intellectual property rights.

|

|

Source: RTA data from the WTO. Tariff data from World Bank World Development Indicators. Notes: Tariffs are simple average applied most-favored nation (MFN) (i.e., tariffs applied on imports from WTO members). Bound rates can be significantly higher than applied rates for some countries. Data are not available for all countries for all years. Missing data were imputed by taking the average of the closest observations. |

Against this backdrop of evolving and increasingly complex trade agreement negotiations and a growing number of RTAs worldwide, the Trump Administration has raised doubts about the economic benefits of recent U.S. FTAs and has taken steps to alter the current and future U.S. FTA landscape. This includes the U.S. withdrawal from the signed but not ratified 12-party Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), renegotiation of existing FTAs, including with a stated intent to place a major focus on trade imbalances, and a stated preference to negotiate future agreements bilaterally, rather than on a multi-party or regional basis. Congress will likely play a critical role in shaping future U.S. trade agreements since it must pass implementing legislation to bring FTAs into force. In order to receive expedited legislative consideration, such trade agreements must advance the U.S. trade negotiating objectives Congress established in its 2015 grant of Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), which is scheduled to remain in effect until July 1, 2021 unless Congress enacts, by July 1, 2018, an extension disapproval resolution regarding the Administration's recently submitted extension request.

|

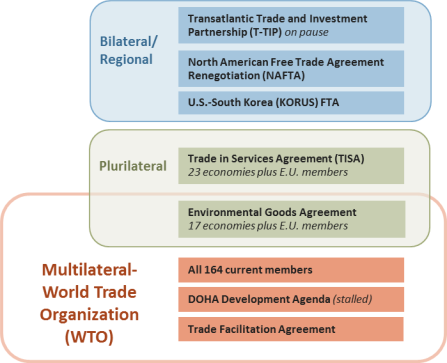

Types of Trade Agreements There are many different types of international trade agreements. It is useful to distinguish among three major categories for the discussion that follows. Multilateral trade agreements refer to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), and the subsequent World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements to which164 countries are now party. These agreements generally establish the foundation of the international trading system. This report focuses specifically on a second category of agreement, bilateral and regional trade agreements (RTAs), defined as reciprocal preferential arrangements outside the multilateral system and among two or more parties. This definition of RTAs encompasses both preferential trade areas in which two or more countries reduce or eliminate tariffs on trade among one another but maintain independent external tariff regimes, as well as customs unions, which go further and include the coordination of a common external tariff. In U.S. trade policy, RTAs are typically referred to as free trade agreements (FTA), and for clarity this report reserves the use of FTA strictly to discuss U.S. bilateral and regional agreements. In some cases, RTAs build upon existing multilateral commitments, for example by further reducing tariffs among the parties. They may establish new commitments not covered in the WTO, such as U.S. FTA provisions on investment protections and labor rights. Plurilateral agreements, typically refer to a third category of agreement that has elements of both RTAs and multilateral agreements. Like RTAs, only a subset of WTO members participate in plurilateral agreements, but participating members may extend the benefits negotiated in the agreement to all WTO members. For example, the 17 participants of the Environmental Goods Agreement negotiations have agreed that they will extend negotiated tariff reductions on environmental goods to all WTO members. The United States is currently involved in all three types of trade agreements as seen here.

|

Since the passage of the 1934 Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act, U.S. trade policy, and particularly trade agreement negotiations, have focused largely on reducing international barriers to trade on a reciprocal basis.5 In the immediate aftermath of World War II (WWII), policymakers in the United States and Europe, in particular, aimed to reverse past policies of the late 1920s and 1930s, when countries raised tariffs against one another, thereby exacerbating and prolonging the Great Depression and contributing to the economic and financial dislocation that many believe led to the outbreak of the war. These countries, motivated by a desire to prevent a future escalation in tariff barriers and to use trade liberalization to promote economic growth, peace and stability, created the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947, establishing the foundation of the modern multilateral trading system.6

In 1995, as part of the Uruguay Round negotiations, the GATT became part of the World Trade Organization (WTO), alongside major agreements covering services, intellectual property rights, agriculture and binding dispute settlement for the first time. Since the creation of the GATT, the United States, as the world's largest economy, has been a key driver of multilateral trade agreement negotiations, including in expanding the depth and scope of commitments. For many reasons, since the conclusion of the Uruguay Round, it has been increasingly difficult to conclude another major round of multilateral trade liberalization negotiations, such that since that time new trade rules have been established largely in RTAs.

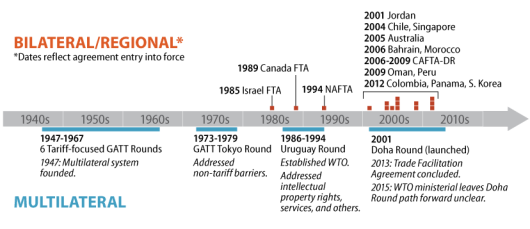

In the 1980s, the United States began negotiating FTAs, the first of which entered into force with Israel in 1985. Bilateral negotiations on tariffs were part of U.S. trade policy long before the advent of the multilateral system, but U.S. FTAs are more extensive than earlier bilateral agreements, including the near complete elimination of tariffs among the parties, and a broad range of commitments beyond tariffs. While new provisions have been added over time, the general outlines of a U.S. FTA have remained largely consistent since the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) entered into force in 1994. Non-U.S. RTAs vary considerably in terms of the scope and depth of commitments. There is extensive debate over the effect of these agreements on trade negotiations at the broader multilateral level, with some evidence that they have both spurred and impeded multilateral efforts toward liberalization. The number of bilateral and regional agreements, including U.S. FTAs, has grown significantly in number since the conclusion of the Uruguay Round, the last major multilateral agreement, in 1994.

While the overarching goal of U.S. trade negotiations in the postwar period has focused on trade liberalization and its broad economic welfare gains, concerns over the effects of import competition on certain domestic U.S. industries and workers have always been present to varying degrees and have influenced policy decisions. In addition to transition periods for removing certain barriers in specific trade agreements, the United States and other countries have special safeguard mechanisms to address harmful import surges and enable adjustment to trade competition. Other trade policy tools are also in place to provide remedies from injury resulting from unfair trade practices such as dumping and subsidies.

In several instances, action on trade agreement implementation has been accompanied by new or enhanced trade adjustment programs to help workers and firms adversely affected by more open markets adjust to greater trade competition through training and income support. For example, the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, which authorized tariff reductions of up to 50%, also created the first iteration of the Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA) program that provides compensation and assistance to workers and firms negatively affected by trade.7 The Trade Act of 1974, which authorized the Administration to negotiate reductions in both tariff and nontariff barriers and created the modern TPA, also expanded TAA and provided new authorities under Section 301 allowing the President to take action to address foreign trade barriers.8

The evolution of U.S. trade agreements has been informed by ongoing debate among some Members of Congress and affected stakeholders, whose varied interests include market access abroad, domestic import competition, and access to lower-cost and a greater variety of goods, services, and agriculture. The 115th Congress will likely continue to debate many aspects of U.S. trade agreement policy as it engages with the Trump Administration regarding possible modifications to existing U.S. FTAs, including NAFTA and the U.S.-South Korea (KORUS) FTA, and potential new trade negotiations.

|

|

||||||||||||||

Relationship to WTO

The relationship between regional trade agreements (RTAs) and the broader multilateral system (i.e., the WTO) is complex. While permitted by WTO rules, RTAs are technically a violation of a fundamental principle of the WTO, the most-favored nation (MFN) concept. MFN requires WTO adherents to treat all other members uniformly in their trade policies. RTAs, however, are explicitly discriminatory, committing participants to treat trade partners inside the agreement differently than those outside, except for certain provisions that may be applied on an MFN basis. The WTO agreements allow an exception for RTAs on the theory that such agreements, subject to certain rules, may further WTO goals of increasing trade and economic openness and could eventually facilitate a multilateral agreement. There is considerable debate, however, over how these agreements affect multilateral negotiations, with some historical examples suggesting they can both incentivize as well as impede multilateral action. In addition to affecting the pace of multilateral negotiations, RTAs may also influence their outcomes, including the type and level of commitments negotiated multilaterally. They may serve as incubators for new trade policies, or potentially create different standards that could complicate the international commercial environment. These concerns are particularly heightened today given the proliferation of RTAs and the rise of mega-regionals.

WTO Rules on RTAs

The WTO Agreements provide three different exceptions for RTAs. Article XXIV of the GATT allows for both free trade areas and customs unions (free trade areas with a common external tariff).9 Similar language in Article V of the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) allows for economic integration agreements outside the WTO relating to services trade.10 Recognizing that such agreements can lead to negative effects on other WTO members and the multilateral system as a whole, these provisions require that RTAs be notified to the other members, cover "substantially all trade," and do not effectively raise barriers on imports from third parties.11 The WTO agreements also set out special provisions relating to developing countries. Paragraph 2(c) of the "enabling clause," which deals with special and differential treatment for developing countries,12 allows RTAs among developing countries with the "mutual reduction or elimination of tariffs."13 In addition, the RTA provisions in the GATS also clarify that services agreements that include a developing country can have greater flexibility regarding the extent of their sector coverage.

There are questions over the degree to which RTAs adhere to these criteria, particularly regarding notification and coverage. Estimates suggest roughly 100 RTAs are in force but not notified to the WTO.14 In addition, there is considerable variation in the scope and extent of liberalization in existing RTAs.

The WTO itself has had difficulty in assessing RTAs against these metrics. One issue is ambiguity in the requirements (e.g., how does one define "substantially all trade"?). Another challenge is the transparency and notification process. If WTO members are not made aware of ongoing trade agreement negotiations, or only after they are already in effect, it is difficult to weigh in on their design. The WTO Doha Round of multilateral negotiations, which began in 2001, potentially was to address some of these issues and revisit the WTO RTA review process. As those negotiations remain stalled, reviews currently take place under a provisional 2006 transparency initiative.15 As part of that initiative, the WTO Secretariat makes a factual presentation on the contents of new agreements and their provisions after they have been notified.16

Individual WTO members have the option to use the institution's dispute settlement proceedings to address perceived violations of WTO rules on the requirements of RTAs.17 While some members, including the United States,18 have raised concerns that some RTAs do not adhere to WTO rules, including that they cover substantially all trade, such concerns have rarely been taken to a formal dispute settlement proceeding.19 Some trade scholars argue that the rationale behind this lack of formal objection stems from the proliferation of RTAs among nearly all members, and hence a desire to keep one's own RTAs from excessive scrutiny.20 Even among U.S. FTAs, which include near complete tariff elimination, there are some provisions that could violate WTO RTA rules. For example, the signed but not implemented TPP agreement included a 30-year tariff phase-out period for U.S. light truck tariffs. WTO rules technically require that the implementation of RTAs take no longer than 10 years except in exceptional circumstances.21

Debate over RTAs and Multilateral System

Since the modern multilateral trading system was first established in 1947, there has been ongoing debate over the effects of RTAs on the system and its members. This debate intensified as agreements proliferated, particularly after the United States began pursuing its own FTAs in the 1980s. Some key aspects of this debate are the economic effects of RTAs on countries within and outside these agreements, the prospects for liberalization under either type of agreement, and how RTAs influence the multilateral system. In recent years, the rise of "mega-regional" RTA negotiations, such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and TPP, or agreements involving multiple countries of considerable economic significance, has added another layer of complexity to this question. On one hand, as these agreements encompass a large number of trading partners they provide opportunities to consolidate existing agreements under one uniform framework; on the other hand, they could potentially cover such a significant share of world trade as to render questions over the WTO's primacy as the trade liberalization and rule-making forum for international commerce.22

Economic Effects

Multilateral and RTA trade liberalization can have different economic outcomes. Generally, the economic benefits of trade liberalization result from the removal of tariff and nontariff barriers (i.e., policies that distort underlying price signals in international commerce), which allows countries to specialize in the production of goods and services in which they have a relative comparative advantage. Economic theory posits that this shift in production should allocate resources most efficiently within and among countries, resulting in lower prices that benefit consumers, and therefore nondiscriminatory trade liberalization (i.e., multilateral tariff reductions) should generally lead to an unambiguous increase in global aggregate welfare.23

The economic effects of trade liberalization under RTAs are less clear, due to their discriminatory nature. Countries inside the agreement face one set of tariff and nontariff barriers, while those outside face another. Therefore the lowering of trade barriers among RTA partners, could lead both to trade creation whereby higher cost domestic production is replaced by imports from a lower cost RTA partner (an efficiency gain), as well as trade diversion whereby imports from a low-cost producer outside the agreement are replaced by imports from a higher cost producer inside the agreement (an efficiency loss).24 This possibility for trade diversion is what distinguishes RTAs from multilateral agreements in economic analysis. These trade diversion effects can negatively affect economic welfare of countries both inside and outside the RTA. In practice, it is typically countries outside the RTA that are expected to face negative trade diversion effects. For example, economic modeling of the potential effects of TPP, estimated welfare gains for the 12 countries participating in the agreement, but slight losses for China, India, and Thailand due to trade diverting from these countries to TPP members.25

|

Trade Diversion vs. Trade Creation Consider a three-country world of apparel trade between Brazil, Vietnam, and the United States (see table below). Suppose production costs for t-shirts are $3 in Vietnam, $4 in Brazil, and $5 in the United States. (A) If the United States imposes a 100% tariff on t-shirts, costs for U.S. retailers would initially be $6 on imports from Vietnam, $8 on imports from Brazil, or $5 for U.S.-made shirts. The United States would import no t-shirts. (B) Now, suppose a multilateral agreement reduces U.S. tariffs on all partners by 50%. Costs for U.S. retailers are now $4.50 on t-shirts from Vietnam, $6 on t-shirts from Brazil, and $5 for U.S.-made shirts. After the tariff reduction, U.S. buyers would shift to imports from Vietnam. This agreement would be trade creating since the United States would now import t-shirts from a lower cost producer, resulting in a more efficient allocation of production. (C) Now further suppose the United States and Brazil form an RTA that eliminates remaining tariffs, but only between each other. Costs for U.S. retailers would still be $4.50 for Vietnamese t-shirts and $5 for U.S. shirts, but now Brazilian shirts would cost only $4. This agreement would be trade diverting since the United States would now import t-shirts from Brazil, despite lower cost production in Vietnam, resulting in an overall global loss of economic efficiency relative to a scenario in which imports from all nations faced the same duty rate.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Whether such RTAs are welfare enhancing then depends on the relative degree of trade diversion and creation resulting from an agreement. Empirical studies vary on their estimates of trade diversion and the significance of this problem, and such studies are inherently challenging exercises given the difficulty in parsing out the other factors simultaneously influencing trade flows.26 Concerns over the trade diverting aspects of RTAs, however, may be waning, in large part because tariffs have fallen dramatically worldwide through a combination of multilateral, bilateral/regional, and unilateral actions. According to one international economist, "the specter that regional trading agreements would inefficiently divert trade never really appeared."27 However, more recent research highlights that trade agreements may have a strong effect on trade flows even when applied tariffs are already low because they lower uncertainty over fluctuations in trade barriers, including by lowering bound tariff rates to applied levels.28 Therefore, while most economists acknowledge the potential benefits of RTAs, many also urge continued evaluation regarding their effects on economic welfare,29 and some remain very skeptical of their overall benefit.30

The trade creation and diversion debate has largely focused on tariff commitments. Nontariff commitments, however, are increasingly important components of RTAs, especially U.S. FTAs (see "Content of U.S. FTAs" for discussion of FTA commitments). Such commitments often involve domestic regulatory changes, and therefore may be less discriminatory against non-RTA parties than in the case of tariffs—in other words, non-RTA parties can also benefit from a country's lowering of nontariff barriers, often called "spillover" effects.31 It is often difficult, if not impossible, to apply nontariff commitments on a country-by-country basis. Moreover, the WTO exemptions regarding RTAs do not apply to all commitments, such as the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS). Therefore, IPR commitments in RTAs are not allowed to discriminate against other WTO members.32

Influence on the Multilateral System

Perhaps more consequential in today's trading environment than the debate over the issue of trade creation and trade diversion resulting from RTAs is the dynamic question of how RTAs influence the pace and scope of negotiations at the multilateral level.

Again, the evidence is inconclusive.33 The two types of agreements have worked simultaneously, and at times RTAs may have spurred action at the multilateral level.34 For example, some trade scholars argue that the formation and then expansion of the European Union led the United States and Japan to push for the Kennedy Round of multilateral trade negotiations in the 1960s in order to minimize export disadvantages in European markets as a result of the expanded customs union.35 Similarly, NAFTA, which eliminated most tariff barriers between the United States, Canada, and Mexico and was passed by Congress in 1993, may have spurred action on the Uruguay Round agreements, which were signed the following year.36 Some, however, question whether the more recent surge in the number of RTAs has removed incentives for members of the WTO to pursue multilateral negotiations, or has simply drawn needed energy and resources away from the multilateral process.37 Economists have also found empirical evidence, specifically in the case of U.S. multilateral tariff offers, that existing RTAs lessen members' willingness to lower tariffs via multilateral negotiations.38

Yet, few experts argue that RTAs alone are the cause of the stagnation in successful multilateral negotiations since 1995. Some economists suggest the global trading system's difficulties are a result of its own success, as the major reduction of tariff and certain nontariff barriers over the past seven decades has hampered incentives for new agreements. Other possible explanations for the more challenging multilateral environment today include the greater number of participants, the growing role of developing countries in world trade and the fact that their priorities sometimes differ from those of developed countries, and the increasingly complex nature of nontariff issues and inherent challenges of measuring compliance.39

As new RTAs increasingly include commitments on various nontariff barriers and trade issues not currently addressed at the WTO, there are growing questions over how these new provisions may eventually affect multilateral rules. There are historical cases, such as NAFTA and its commitments on intellectual property rights (IPR) and dispute settlement for example, in which commitments similar to those found in RTAs quickly made their way into the multilateral system. There are also concerns, however, over the potential for a two-tiered system to emerge, one based on older multilateral rules, and another based on more modern commitments found in RTAs.40 Another concern is how different RTAs may craft their rules, and to the extent they diverge whether this would create impediments for international commerce, or at least limit the benefits of liberalization.41 On the other hand, some see RTAs as a trial space to explore different options for updating international trade rules, such as new commitments on digital trade.

In the view of two authoritative figures on international trade issues:

Preferential trade agreements represent a challenge and an opportunity for the multilateral trading system. The opportunity is to use them as experimental laboratories for cooperation on issues that have not (yet) been addressed multilaterally, especially issues where the outcome is applied on a MFN basis. The challenge is to control the discrimination that is inherent in any PTA [preferential trade agreement].42

There may also be a first-mover advantage in establishing RTAs. Economic theorists have created models that show a domino effect of RTAs, whereby countries are induced to join based in part on the potential for lost competitiveness from staying outside the agreement (also referred to as competitive liberalization).43 In practice, this may have been the motivation behind the expanding list of countries interested in the U.S.-led TPP negotiations during the Obama Administration. Japan, for example, announced its intent to participate in TPP shortly after the United States and South Korea implemented their bilateral FTA. Japan and South Korea compete in the U.S. market on a range of products, including motor vehicles, both countries' top export to the United States. China also expressed "interest" in the TPP to U.S. officials.

This dynamic could have significant implications in terms of establishing new trade rules, giving original members of trade pacts outsized influence, especially in the current landscape of mega-regional negotiations. Indeed, influencing global trading rules was a major stated goal of the Obama Administration in its pursuit of the TPP.44 Concerns over competitiveness in export markets may also be important in providing political cover to economic reformers within countries debating participation in trade liberalizing agreements and facing opposition from domestic interests that expect increased import competition.

U.S. Free Trade Agreements (FTAs)45

The United States has been a major advocate of trade liberalization through multilateral agreements, but since the late 1980s has simultaneously pursued FTAs for numerous economic, political, and strategic reasons. Through both bilateral and multi-party negotiations the United States has negotiated, signed, and implemented 14 FTAs with 20 different countries.46 Implementing legislation for the first U.S. FTA, the agreement with Israel, was signed in June 1985, while the most recent FTAs passed by Congress—agreements with Colombia, Panama, and South Korea—were signed into law in October 2011. During that time, U.S. FTAs have evolved with certain commitments clarified and expanded, new issues added, and some commitments dropped. These agreements have generally built upon one another, often seeking higher standards beyond WTO provisions, and have a number of common elements. This section provides a brief history of U.S. FTA negotiations and discussion of Trump Administration FTA policies to date, an examination of the typical components of U.S. FTAs, and analysis of trade trends under U.S. trade agreements.

Evolution of U.S. FTA Negotiations, Objectives, and Strategies

From the creation of the GATT in 1947 until the 1980s, U.S. efforts toward trade liberalization focused primarily on agreements in the multilateral setting, with the United States and other countries strongly eschewing discriminatory bilateral arrangements.47 The U.S. focus on the multilateral system during this time in part reflected a reaction to the tit-for-tat trade discrimination that occurred in the 1930s and a desire to establish mechanisms to avoid such actions in the future. Judged by the metric of global tariff rates, the multilateral system was successful as successive rounds of multilateral negotiations achieved a significant reduction in average tariffs (above 30% reduction in weighted average in some rounds).48 However, nontariff barriers became increasingly problematic both due to their growing relative significance as tariffs fell, and due to their increased use as an alternative mechanism to restrict imports in sensitive areas.49

Congress attempted to address this concern over the growth in nontariff barriers, as well as general concerns over less than reciprocal U.S. access to foreign markets, in the Trade Act of 1974 (P.L. 93-618). Some in Congress also raised concerns at that time over the discriminatory effects of preferential agreements, specifically the expansion of the European Community.50 In response, Congress encouraged the executive branch to engage in new international negotiations covering a wider range of topics and approaches, including commitments on nontariff barriers. Specifically, Congress created a new negotiating authority for the executive branch, today known as Trade Promotion Authority (TPA), ensuring expedited legislative consideration for trade agreements and specifically mandating negotiation on nontariff issues (Section 102).51 At the same time, Congress clarified that this authority applied not only to multilateral negotiations (the primary venue for engagement at the time), but also to bilateral agreements, and encouraged the Administration to undertake such a negotiation with Canada (Sections 105 & 612).

It would take roughly another decade before the first U.S. FTA negotiations began under the Reagan Administration. Since that time, every U.S. President has initiated or concluded at least one U.S. FTA. Presidents Clinton, George W. Bush, and Obama, each also worked with Congress to implement FTAs concluded by their immediate predecessor.

Reagan Administration. The first U.S. FTA negotiations, under the Reagan Administration, took place under two subsequent grants of TPA in the Trade Agreements Act of 1979 (P.L. 96-39) and Trade and Tariff Act of 1984 (P.L. 98-573) (Figure 2).52 Scholars assert that the rationale for the U.S.-Israel FTA, concluded and passed by Congress in 1985 (P.L. 99-47), was largely based on foreign policy dynamics.53 Meanwhile, the second agreement, with Canada, at the time the largest U.S. trading partner, was primarily done for commercial reasons. Some argue the United States may have also sought the agreement with Canada to generate interest in a new multilateral round of negotiations.54 The U.S.-Canada FTA negotiations began in May 1986 and the multilateral Uruguay Round negotiations got underway the following September. The U.S.-Canada FTA was concluded and implementing legislation was passed by Congress in 1988 (P.L. 100-449).

George H.W. Bush Administration. The next significant step in U.S. FTA negotiations occurred simultaneously with the ongoing multilateral Uruguay Round negotiations under a TPA grant in the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988 (P.L. 100-418). In 1991, three years after the U.S.-Canada FTA was concluded, the United States began trilateral negotiations with Canada and Mexico on the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). NAFTA was signed in 1992 in the last days of the George H.W. Bush Administration, but not considered by Congress at the time due to concerns in part over a lack of labor and environmental provisions.

Clinton Administration. The Clinton Administration began its FTA efforts negotiating additional labor and environmental side agreements to NAFTA to address congressional concerns. Congress passed NAFTA at the end of 1993 (P.L. 103-182).55 The Uruguay Round negotiations, ongoing since 1986, were concluded and signed shortly after NAFTA under a special extension of the 1988 TPA grant, which had by then expired, and were subsequently passed by Congress in 1994 (P.L. 103-465). At the end of his Administration, President Clinton also negotiated and signed an FTA with Jordan. The agreement is the only U.S. FTA not signed or implemented by Congress under TPA procedures, as Congress did not pass new TPA legislation during the Clinton presidency. Before leaving office, President Clinton also initiated FTA negotiations with Chile and Singapore.

George W. Bush Administration. President George W. Bush greatly expanded the number and regional coverage of U.S. FTA negotiations. In addition to finalizing and implementing the three agreements begun at the end of the Clinton Administration, President Bush initiated and concluded negotiations on nine additional FTAs. The Bush Administration pursued these agreements simultaneously with and viewed them as complementary to the multilateral Doha Development Agenda, which was launched in 2001. After passing implementing legislation for the Jordan FTA (P.L. 107-43), Congress established a new set of trade negotiating objectives and provided the Bush Administration with a new grant of TPA in the Trade Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-210). The eight agreements passed by Congress during the Bush Administration under the 2002 TPA include

- Three agreements with relatively small U.S. trading partners in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, which were motivated by strong foreign policy objectives: Morocco (P.L. 108-302), Bahrain (P.L. 109-169), and Oman (P.L. 109-283);

- The first two U.S. FTAs with trading partners in Asia, including Singapore (P.L. 108-78) and Australia (P.L. 108-286); and

- Three agreements with Latin American trading partners, including a bilateral agreement with Chile (P.L. 108-77), the U.S.-Dominican Republic-Central America FTA (CAFTA-DR, P.L. 109-53), which is a multi-party agreement with Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and the Dominican Republic, and a bilateral agreement with Peru (P.L. 110-138).

President Bush also concluded and signed three trade agreements—with Colombia, Panama, and South Korea—which were not considered by Congress during his Administration. He formally entered the United States into the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations, though no negotiating rounds were held during his presidency.

Obama Administration. The Obama Administration addressed congressional concerns regarding the three pending George W. Bush Administration FTAs including on auto56 and labor57 issues, paving the way for their entry into force. Congress ultimately passed the agreements with Colombia (P.L. 112-42), Panama (P.L. 112-43), and South Korea (P.L. 112-41) under expedited legislative procedures in October 2011. Although the 2002 TPA grant had expired in 2007, the three agreements had been signed and notified to Congress while TPA was in effect and therefore were still eligible for consideration under the TPA procedures. The Obama Administration also pursued two major multi-party FTA negotiations, which, if implemented, would have nearly doubled the share of U.S. trade occurring with FTA partners.

The TPP negotiations included three of the four largest U.S. trading partners (Canada, Japan, and Mexico) and eight other countries in the Asia-Pacific region. In order to provide for potential expedited legislative consideration of TPP and to set updated trade negotiating objectives, Congress passed a new grant of TPA in 2015 (P.L. 114-26) as the TPP talks were nearing conclusion. The 12 TPP participants signed an agreement in February 2016, but President Obama never submitted implementing legislation to Congress due to ongoing consultations with Congress on key provisions and uncertain congressional support.

The Obama Administration also initiated negotiations with the European Union (EU), collectively the largest U.S. trade and investment partner, on a potential Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (T-TIP). The T-TIP negotiations remained ongoing at the end of the Obama presidency. With the multilateral Doha Round negotiations still stalled, the Obama Administration viewed both TPP and T-TIP as an opportunity to establish new regional trading rules with economically significant trading partners on emerging issues like state-owned enterprises and digital trade.

|

Figure 2. Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) and U.S. Trade Agreements |

|

|

Source: CRS with data from U.S. trade promotion authority and trade agreement legislation. |

Trump Administration FTA Policy and Recent Developments

President Trump took office after running a campaign that was highly critical of U.S. trade agreements, arguing that they negatively affected U.S. workers and industries. During his tenure in office, the President has continued to express dissatisfaction with U.S. trade agreements, referring to the KORUS FTA, for example, as "a disaster for the United States."58 Much of the President's concern with U.S. FTAs relates to the U.S. trade deficit, which he asserts stems from bad trade deals and "unfair trading practices" of U.S. FTA partners. In order to investigate this relationship, the Administration undertook examinations of U.S. bilateral trade deficits and the outcomes of existing U.S. FTAs focused on potential violations of commitments or negative effects. To date those studies have not been made public, but may inform U.S. negotiations moving forward.59

The President has also taken issue with U.S. participation in multi-party FTA negotiations, arguing that bilateral negotiations create more leverage for the United States, given the much greater size of the U.S. economy relative to most potential FTA partners. Many trade policy experts have argued conversely, noting particular benefits from a multi-party approach. They suggest that, especially in the context of TPP, the multiparty approach made concessions by other countries more politically feasible, in part, by lessening the appearance of submitting solely to U.S. interests, and have highlighted the benefit of such an approach in establishing more uniform regional trade rules and disciplines.60

To date, the President has taken a number of steps to alter U.S. FTA policy. The first, in January 2017, was the withdrawal of the United States as a signatory to the TPP.61 After withdrawing from TPP, the Trump Administration set out to revisit commitments in existing U.S. FTAs. This has included initiating a renegotiation of NAFTA and bilateral talks toward modifications to the KORUS FTA. Despite questioning the value of the TPA process, the President has followed TPA procedures with regard to the NAFTA renegotiation.62 Therefore, changes to NAFTA requiring congressional action could receive expedited legislative consideration if the agreement is signed while TPA is in effect. The President has not followed TPA procedures, however, with respect to the KORUS FTA talks. In March 2018, the Administration announced an agreement in principle on modifications to KORUS.63 The limited commitments, including tariff schedule modifications and South Korean regulatory changes will likely not require implementing legislation in order to become effective, since the legislation implementing the original KORUS agreement gives the Administration authority to make tariff modifications on U.S. imports from South Korea.

In many areas, including digital trade and state-owned enterprises, the Trump Administration's negotiating objectives for the NAFTA modernization talks are similar to U.S. positions in the TPP negotiations under President Obama, which included NAFTA partners Canada and Mexico.64 In other areas, such as proposed modifications to rules of origin, investor-state dispute settlement, government procurement, and a "sunset provision" that would reportedly require a renewal of the agreement every five years, the Trump Administration's proposals differ considerably from prior U.S. policy.65

Despite a critical view of existing agreements, the Trump Administration has also expressed interest in negotiating new bilateral FTAs, including with the United Kingdom and TPP countries like Japan. To date no TPP country has formally endorsed a new FTA negotiation with the United States, which may, in part, reflect wariness toward the contentious nature of the ongoing NAFTA talks. The President has repeatedly stated his willingness to unilaterally withdrawal the United States from NAFTA should current talks not reach a satisfactory conclusion.

Content of U.S. FTAs66

U.S. FTAs have evolved in the scope and depth of their commitments since the 1980s. Despite the variation in each U.S. FTA, there has been a general trend toward more comprehensive and enforceable commitments. The first bilateral U.S. FTA, with Israel, is only 14 pages in length and focused primarily on the elimination of tariffs. Other provisions, such as services and intellectual property rights, are included in the text but with few explicit commitments.67 Since that time, U.S. FTAs have expanded to include enforceable and extensive provisions on a range of trade-related issues. Key observations regarding the content of existing U.S. FTAs include

- NAFTA represented a major step in establishing the current nature of U.S. FTAs and even multilateral commitments, serving in many ways, as a template for future agreements;

- A limited number of provisions included in NAFTA and early FTAs have been restricted or eliminated in later U.S. FTAs. These include NAFTA's Chapter 19 commitments, which allow for review of trade remedy cases, a provision not incorporated in any other U.S. FTA. Commitments affecting visa issuance for temporary entry of business persons, are only included in NAFTA and bilateral FTAs with Chile and Singapore;68

- Significant changes in U.S. FTA provisions since NAFTA, particularly the agreements with Colombia, Peru, and South Korea, include modifications to commitments on labor and environment, e-commerce, services, and intellectual property rights. These stem in part from updated negotiating objectives in the 2002 grant of TPA as well as the 2007 agreement between the George W. Bush Administration and congressional leadership known as the "May 10th Agreement," which further clarified U.S. trade negotiating objectives;69

- The Jordan FTA was negotiated and ratified without TPA procedures in effect in 2001, and generally has less extensive commitments than NAFTA (e.g., the FTA contains no commitments on investment); and

- The multilateral Uruguay Round Agreements entered into force in 1995, one year after NAFTA became effective, and included commitments on issues also included in NAFTA, such as services trade, intellectual property rights protections, agriculture and dispute settlement. U.S. FTAs after 1995 reinforce and build upon these multilateral commitments.

In terms of the specific commitments included in existing U.S. FTAs, there is variation among the 14 agreements, particularly in the precise language included in the texts. However, NAFTA and later FTAs have certain common elements, including core rules such as nondiscriminatory and national treatment among the parties (i.e., treating the goods, services, and investment of another party the same as domestic sources), and transparency in the regulatory process. Major elements (beginning with tariffs and then in alphabetical order) in U.S. FTAs include

- Tariffs and Market Access. U.S. FTAs generally eliminate most tariffs on manufactured goods and most tariffs and quotas on agriculture products among the parties immediately. Tariffs and quotas on more import sensitive items are usually phased out over time, generally within a few years, but ranging up to 20 years.70 Some tariffs or quotas remain in place indefinitely on the most import sensitive agricultural products.71 U.S. FTAs also include nontariff market access provisions covering issues such as import and export restrictions, import licensing, and export taxes. U.S. FTAs implemented after the Jordan FTA also ban import duties on remanufactured goods traded between the parties.72

- Competition Policy, Monopolies, and State Enterprises. First established in NAFTA and included in U.S. FTAs with Australia, Chile, Colombia, Peru, Singapore, and South Korea, these provisions commit the parties to maintain or establish laws that prohibit anticompetitive business behavior, though certain aspects are often not subject to dispute settlement procedures. The later agreements expanded the commitments to require nondiscriminatory treatment in the application of anti-competition laws with respect to entities of the other party and to specify transparency and administrative requirements.

These chapters also address concerns over competition with monopolies requiring that they act in accordance with commercial considerations and in a nondiscriminatory manner in purchase and sale decisions. They also prohibit monopolies from engaging in anticompetitive behavior including through cross-subsidization. More limited commitments on the activities of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are also included, requiring nondiscriminatory treatment in the sale of goods and services. The U.S. Singapore FTA includes the most extensive language on SOEs, requiring, for example, nondiscriminatory treatment in the purchase and sale of goods and services. - Customs and Trade Facilitation. NAFTA established rules on customs procedures and administration, including what may be required of an importer to claim preferential treatment and prove origin under the agreement as well as what is expected of customs agencies in responding to requests for advance rulings on potential imports. Later U.S. FTAs expanded those commitments to include broader trade facilitation provisions related to: the release of goods, in some cases with target maximum timeframes; automation, including electronic systems; expedited customs procedures for express delivery shipments; and publication of customs laws, regulations, and procedures. U.S. FTAs with Colombia, Oman, Panama, Peru, and South Korea also establish a minimum de minimis threshold (generally $200) on the value of imports, below which expedited customs procedures apply and taxes and duties are generally not applicable. The de minimis threshold in the United States is currently $800.73 All 14 U.S. FTAs were implemented prior to the 2013 conclusion of the multilateral WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA), which entered into force in February 2017 and includes related provisions.74

- Cross-Border and Financial Services.75 NAFTA includes the three core services commitments of national treatment, most-favored nation treatment, and prohibition of local presence requirements to access markets. It applies these commitments to all services on a negative list basis, excluding only those services explicitly exempted in the schedules of nonconforming measures. The negative list feature has become a hallmark objective of U.S. services negotiations, and is included in all subsequent U.S. FTAs, except the U.S.-Jordan FTA. The NAFTA financial services chapter also establishes transparency commitments in the regulatory process, including time limits for responses to administrative requests. It also requires that opportunities to supply newly approved financial services in any party's market are accessible to the firms of all parties, and includes a requirement that companies be able to transfer "information in electronic form" in and out of each party's territory (Article 1407).76

In addition to the three core commitments listed above, U.S. FTAs subsequent to NAFTA also include market access provisions in both cross-border and financial services chapters, which prohibit restrictions on the number of service providers, value of service transactions, and types of legal entities allowed to supply services. They also set out additional transparency and regulatory requirements. - Dispute Settlement.77 U.S. FTAs include provisions for a dispute settlement mechanism, which may be used to resolve disputes regarding each party's adherence to agreement obligations. These enforcement commitments require the parties to attempt to resolve disputes through consultation before pursuing the formal dispute settlement process. If resolution of the dispute cannot be achieved through consultation, a panel, typically consisting of three arbiters, may be convened to adjudicate. U.S. FTA dispute settlement cases, excluding disputes under NAFTA's Chapter 19 provisions, are rare, as most issues are resolved through consultation, or adjudicated at the WTO if multilateral obligations are also relevant to the dispute. To date only four cases have been resolved through a U.S. FTA dispute settlement panel, three under NAFTA and one under CAFTA-DR (Guatemala).

- E-commerce.78 U.S. FTA commitments in e-commerce chapters have expanded considerably in their scope and enforceability since they were first included in the U.S.-Jordan FTA (NAFTA does not contain an e-commerce chapter). The main provisions include language to: (1) prohibit customs duties on electronically transmitted products, (2) disallow discriminatory treatment of digital products on the basis of their origin; and (3) subject digitally delivered services to the relevant provisions of the investment, cross-border services, and financial services chapters. The KORUS FTA represents the most expansive e-commerce chapter, including provisions on electronic authentication and electronic signatures and committing the parties to endeavor to limit barriers to data flows across borders. A strengthened version of the latter provision was a key component of the TPP's digital trade provisions.

- Government Procurement. U.S. FTAs include commitments to provide certain levels of access to and nondiscriminatory and national treatment in the pursuit of FTA parties' government procurement markets. The extent of new access granted by the FTA depends on whether or not the U.S. FTA partner is already a member of the plurilateral WTO Government Procurement Agreement (GPA). For U.S. FTA partners that are GPA members, FTA commitments may expand on GPA commitments by, for example, setting a lower monetary threshold for covered procurement. U.S. states may include their procurement in U.S. FTA commitments, but the number of states choosing to do so has fallen considerably over time, from 37 state participants in the U.S.-Chile FTA to 10 in the KORUS FTA. Among the 20 U.S. FTA partner countries, Canada, Israel, Singapore, and South Korea are currently members of the GPA.

- Intellectual Property Rights (IPR).79 NAFTA's commitments on intellectual property rights represented a major step in the evolution of international trade agreements. Negotiated at the same time as the Uruguay Round agreements, they share much in common with the multilateral Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). NAFTA includes protections for copyrights (life of the author plus 50 years), patents (20 years) including exclusivity periods for test data (5 years for pharmaceuticals), trade secrets, trademarks, and geographical indications, as well as specific requirements on the enforcement of these provisions.

The negotiating objectives in the 2002 TPA established a new iteration of U.S. FTA commitments on IPR, specifically calling for provisions that "reflect a standard of protection similar to that found in United States law."80 Thus the FTAs negotiated under that grant of TPA include strengthened provisions such as longer copyright protection (life of the author plus 70 years), mandate patent term extensions for unreasonable delays in the approval process, and include patent linkage provisions, which seek to ensure that marketing approvals for generic versions of patented products fully respect existing patent protections. These later agreements also include new provisions related to IPR in the digital environment such as internet service provider liability and safe harbor provisions. They also specify domain name dispute resolution commitments.

Due to concerns over the appropriate balance between strong IPR commitments and providing adequate access to medicines in developing countries, the "May 10th Agreement" included certain modifications to U.S. FTA IPR commitments related to patents for pharmaceutical products. As a result, the U.S. FTAs with Colombia, Panama, and Peru make optional the patent term extension and patent linkage provisions and put limitations on the five-year data exclusivity period for pharmaceutical patents. - Investment.81 Excluding agreements with Bahrain, Israel, and Jordan, U.S. FTAs include a chapter with commitments to reduce restrictions on investment and ensure investor protections, a key area in which U.S. FTAs extend beyond multilateral commitments, which consist only of limited provisions in the Agreement on Trade-Related Investment Measures (TRIMs). Core commitments beginning with NAFTA include: (1) nondiscriminatory treatment relative to both domestic and other foreign parties; (2) minimum standard of treatment (MST), including "fair and equitable treatment and full protection and security"; (3) requirements for compensation in the case of direct or indirect expropriation; (4) restrictions on performance requirements that would condition investment access; (5) provisions for expeditious transfer of funds; (6) denial of benefits to investors with limited commercial activity in the FTA region; and (7) an investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanism that allows private investors to take host governments to binding arbitration regarding potential violations of the FTA investment provisions.82 Among the 11 U.S. FTAs with investment chapters, only the U.S.-Australia agreement does not include an ISDS mechanism.

- Labor and Environment.83 NAFTA also represented a major step forward in U.S. FTA provisions on labor and environmental protections. Although the original text of the agreement did not include labor and environment commitments, the United States, Canada and Mexico later negotiated legally binding side agreements on labor and the environment that were included in NAFTA implementing legislation. These agreements require the parties to effectively enforce their labor and environmental laws, and ensure these laws provide for "high labor standards" and "high levels of environmental protection." The agreements include separate enforcement mechanisms with limited monetary penalties applicable to select provisions.

Beginning with the Jordan FTA, U.S. FTAs have included specific labor and environmental commitments in the main FTA text. The strength of these commitments has evolved from those first contained in the NAFTA side agreements. The "May 10th Agreement" in particular represented a significant progression in U.S. FTA labor and environmental commitments. U.S. FTAs have advanced to not only require that parties enforce their own labor and environmental laws, but also that parties shall adopt and maintain laws guaranteeing specific internationally recognized worker rights84 and fulfilling obligations under certain multilateral environmental agreements.85 U.S. labor and environmental chapters in the most recent FTAs are also enforceable under the regular FTA dispute settlement procedures, and therefore subject to the same potential penalties.86 In practice, there have been few disputes under U.S. FTAs in these areas; the United States has brought one labor case to dispute settlement involving Guatemala under CAFTA-DR. - Rules of Origin.87 These provisions set criteria to determine if a product is considered to have originated within a party or trading bloc of the FTA and therefore if it is eligible for preferential duty treatment under the agreement. U.S. FTAs vary in their origin requirements in a number of ways including the specific content requirements by product, as well as in the methodologies used to determine origin. For example, under NAFTA 62.5% of an automobile's value must originate within the NAFTA region to qualify for NAFTA benefits. By contrast in the KORUS FTA, the regional value content requirement for autos is 35%.

- Safeguards.88 Beginning with the U.S.-Israel FTA, U.S. FTAs have included provisions allowing for temporary reinstatement of tariffs to protect against serious injury to domestic industries from specific imports. These commitments generally also reaffirm rights and obligations under the multilateral Safeguards Agreement, and discuss the ability to exclude FTA partners from global safeguard cases. The strongest language on this provision is included in NAFTA, which requires that parties shall exclude imports from other FTA parties in any global safeguard case unless they account for a substantial share of imports or are causing particular harm. Most U.S. FTAs also include commitments reaffirming each party's rights and obligations under the multilateral antidumping and countervailing duty agreements.

- Sanitary and Phytosanitary Standards (SPS).89 SPS commitments in U.S. FTAs address trade-related measures countries take to protect the health and safety of human, plant, and animal life, which can have a major impact on agricultural trade. NAFTA and the multilateral SPS agreement were negotiated simultaneously and contain similar enforceable provisions designed to ensure SPS measures are transparent, nondiscriminatory, not intended as a disguised restriction on trade, applied to the extent necessary to achieve the appropriate level of protection, adapted to varying regional conditions, and based on scientific analysis and risk assessments. After the SPS agreement entered into force in 1995, subsequent U.S. FTA commitments on SPS issues largely reinforce the multilateral SPS agreement and are not themselves subject to FTA dispute-settlement mechanisms. U.S. FTAs also generally establish a committee tasked with consultation and cooperation on SPS issues. Certain agriculture industries report that these committees have been instrumental in removing SPS barriers to U.S. exports.90

- Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT). TBT, like SPS issues, relate to regulations or standards set by governments to protect various domestic interests from harm. They were first covered in NAFTA, followed by multilateral commitments in the Uruguay Round Agreements. These commitments seek to ensure TBT measures are transparent, nondiscriminatory, based on science and risk assessments, distort trade as little as possible, and require the use of international standards as the basis of domestic standards where they exist. Later U.S. FTAs build on and affirm rights and obligations under the TBT Agreement and are generally enforceable under dispute-settlement procedures. Some U.S. FTAs also establish industry-specific TBT commitments. For example, the KORUS FTA includes a section specifically on motor vehicle standards and technical regulations (Article 9.7).91

- Telecommunications. NAFTA and subsequent U.S. FTAs (except the U.S.-Jordan FTA) include commitments related to access, transparency, and competition in the telecommunications sector. Specifically, these commitments require that all parties have access to any public telecommunications network on reasonable and nondiscriminatory terms. U.S. FTAs starting with Chile and Singapore also require number portability, independent regulatory bodies, and timely, transparent, and nondiscriminatory allocation of scarce resources like frequencies, among other provisions. These U.S. FTA commitments build on multilateral commitments including a telecommunications annex to the GATS and a 1996 telecommunications reference paper which some governments have made part of their GATS commitments.92

- Transparency and Good Governance. Transparency commitments are included in many NAFTA chapters, but the U.S. FTAs with Chile and Singapore were the first to include stand-alone transparency chapters, which became the norm for subsequent U.S. FTAs. These commitments require parties to publish any relevant laws, regulations, procedures, or administrative rulings in advance and allow stakeholders an opportunity to comment. They also include notification, and review and appeal provisions for administrative actions. Later U.S. FTAs also include provisions related to anti-corruption, including a requirement to establish laws that make corruption affecting international trade and investment a criminal offense.

Trade Trends under U.S. FTAs93

This section provides an overview of U.S. trade patterns under U.S. FTAs. Specifically, it examines the share of U.S. trade covered by FTAs, bilateral trade balances, top products traded with each U.S. FTA partner, and the utilization rates of U.S. FTAs. Services trade data are not yet available for 2017, so most of the discussion focuses on 2016 trade flows. Sections that only cover goods trade use data from 2017.

U.S. Trade Shares with FTA Partners

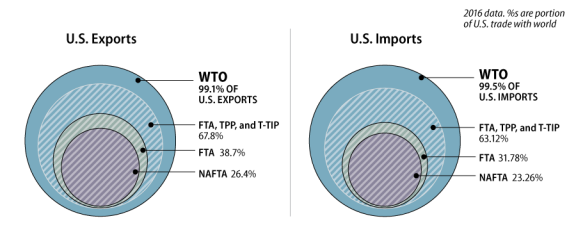

U.S. FTAs have been a significant component of U.S. trade policy, have been influential in establishing new rules for the global trading system, and are a major focus of the current U.S. trade debate. Less than half of U.S. trade, however, takes place with FTA partners while virtually all trade takes place with members of the multilateral trading system. In 2016, 99% of all U.S. trade took place with WTO members (Figure 3), while 39% of U.S. exports and 32% of imports were with U.S. FTA partners (all U.S. FTA partners are also WTO members). NAFTA alone accounts for the majority of U.S. trade with FTA partners (68% of FTA exports and 73% of FTA imports) so the remaining 13 U.S. FTAs comprise a relatively small share of U.S. trade. This number, of course, could grow depending on future U.S. FTA negotiations. For example, the mega-regional agreements pursued by the Obama Administration, including TPP and T-TIP, would have expanded the share of U.S. trade covered by FTAs to roughly 65%. In examining these trade flows it is important to note that not all trade with FTA partners makes use of the FTA benefits (see "Utilization Rates of U.S. FTAs"), and that FTA benefits are only one of several factors that affect trade flows.

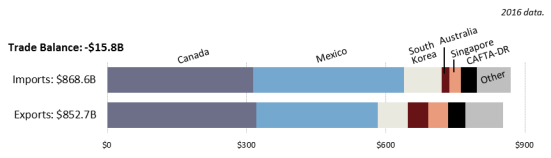

Bilateral Trade Balances with FTA Partners