Introduction

Federal land management decisions influence the U.S. economy, environment, and social welfare. These decisions determine how the nation's federal lands will be acquired or disposed of, developed, managed, and protected. Their impact may be local, regional, or national. This report discusses selected federal land policy issues that the 116th Congress may consider through oversight, authorizations, or appropriations. The report also identifies CRS products that provide more detailed information.1

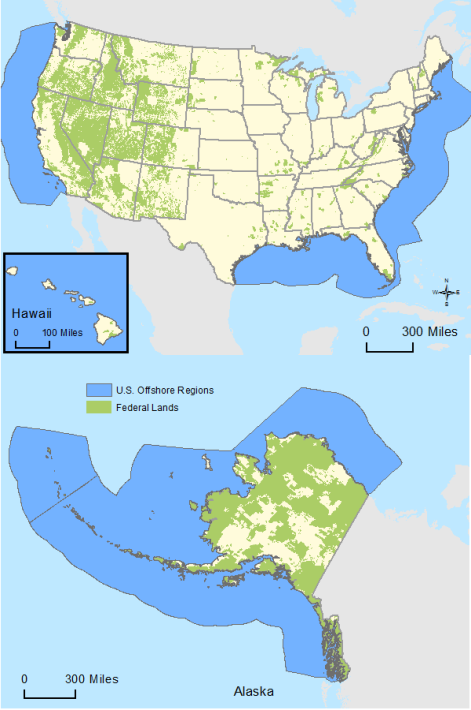

The federal government manages roughly 640 million acres of surface land, approximately 28% of the 2.27 billion acres of land in the United States.2 Four agencies (referred to in this report as the federal land management agencies, or FLMAs) administer a total of 608 million acres (~95%) of these federal lands:3 the Forest Service (FS) in the Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and National Park Service (NPS), all in the Department of the Interior (DOI). Most of these lands are in the West and Alaska, where the percentage of federal ownership is significantly higher than elsewhere in the nation (see Figure 1). In addition, the Department of Defense administers approximately 11 million acres in military bases, training ranges, and more; and numerous other agencies administer the remaining federal acreage.4

The federal estate also extends to energy and mineral resources located below ground and offshore. BLM manages the federal onshore subsurface mineral estate. The Bureau of Ocean and Energy Management (BOEM), also in DOI, manages access to about 1.7 billion offshore acres located beyond state coastal waters, referred to as U.S. offshore areas or the outer continental shelf (OCS). Not all of these acres can be expected to contain extractable mineral and energy resources, however.

|

|

Source: CRS, using data from the National Atlas, Marine Regions, and Esri. Notes: This figure reflects the approximately 608 million acres of surface federal lands managed by the federal land management agencies (FLMAs) in the 50 states and the District of Columbia. This map shows a generalized image of federal lands and DOI offshore planning regions without attempting to demonstrate with any specificity the geographical area of the U.S. outer continental shelf (OCS) or the U.S. exclusive economic zone (EEZ) as defined by state, federal, or international authorities. The Great Lakes are not included in the OCS or EEZ and are largely managed under state authorities. Due to scale considerations, all of the ocean area surrounding Hawaii in the figure is within U.S. waters. |

Federal land policy and management issues generally fall into several broad thematic questions: Should federal land be managed to produce national or local benefits? How should current uses be balanced with future resources and opportunities? Should current uses, management, and protection programs be replaced with alternatives? Who decides how federal land resources should be managed, and how are the decisions made?

Some stakeholders seek to maintain or enhance the federal estate, while others seek to divest the federal estate to state or private ownership. Some issues, such as forest management and fire protection, involve both federal and nonfederal (state, local, or privately owned) land. In many cases, policy positions on federal land issues do not divide along clear party lines. Instead, they may be split along the lines of rural-urban, eastern-western, and coastal-interior interests.

Several committees in the House and Senate have jurisdiction over federal land issues. For example, issues involving the management of the national forests cross multiple committee jurisdictions, including the Committee on Agriculture and the Committee on Natural Resources in the House, and the Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry and Committee on Energy and Natural Resources in the Senate. In addition, federal land issues are often addressed during consideration of annual appropriations for the FLMAs' programs and activities. These agencies and programs typically receive appropriations through annual Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies appropriations laws.

This report introduces selected federal land issues, many of which are complex and interrelated.5 The discussions are broad and aim to introduce the range of issues regarding federal land management, while providing references to more detailed and specific CRS products. The issues are grouped into these broad categories

- Federal Estate Ownership,

- Funding Issues Related to Federal Lands,

- Climate Policy and Federal Land Management,

- Energy and Minerals Resources,

- Forest Management,

- Range Management,

- Recreation,

- Other Land Designations,

- Species Management, and

- Wildfire Management.

This report generally contains the most recent available data and estimates.

Federal Estate Ownership

Federal land ownership began when the original 13 states ceded title of some of their land to the newly formed central government. The early federal policy was to dispose of federal land to generate revenue and encourage western settlement and development. However, Congress began to withdraw, reserve, and protect federal land through the creation of national parks and forest reserves starting in the late 1800s. This "reservation era" laid the foundation for the current federal agencies, whose primary purpose is to manage natural resources on federal lands. The four FLMAs and BOEM were created at different times, with different missions and purposes, as discussed below.

The ownership and use of federal lands has generated controversy since the late 1800s. One key area of debate is the extent of the federal estate, or, in other words, how much land the federal government should own. This debate includes questions about whether some federal lands should be disposed to state or private ownership, or whether additional land should be acquired for recreation, conservation, open space, or other purposes. For lands retained in federal ownership, discussion has focused on whether to curtail or expand certain land designations (e.g., national monuments proclaimed by the President or wilderness areas designated by Congress) and whether current management procedures should be changed (e.g., to allow a greater role for state and local governments or to expand economic considerations in decisionmaking). A separate issue is how to ensure the security of international borders while protecting the federal lands and resources along the border, which are managed by multiple agencies with their own missions.6

In recent years, some states have initiated efforts to assume title to the federal lands within their borders, echoing efforts of the "Sagebrush Rebellion" during the 1980s. These efforts generally are in response to concerns about the amount of federal land within the state, as well as concerns about how the land is managed, fiscally and otherwise. Debates about federal land ownership—including efforts to divest federal lands—often hinge on constitutional principles such as the Property Clause and the Supremacy Clause. The Property Clause grants Congress authority over the lands, territories, or other property of the United States: "the Congress shall have Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States."7 The Supremacy Clause establishes federal preemption over state law, meaning that where a state law conflicts with federal law, the federal law will prevail.8 Through these constitutional principles, the U.S. Supreme Court has described Congress's power over federal lands as "without limitations."9 For instance, Congress could choose to transfer to states or other entities the ownership of areas of federal land, among other options.

CRS Products

CRS Report R42346, Federal Land Ownership: Overview and Data, by Carol Hardy Vincent, Laura A. Hanson, and Carla N. Argueta.

CRS Report R44267, State Management of Federal Lands: Frequently Asked Questions, by Carol Hardy Vincent.

Agencies Managing Federal Lands

The four FLMAs and BOEM manage most federal lands (onshore and offshore, surface and subsurface)

- Forest Service (FS), in the Department of Agriculture, manages the 193 million acre National Forest System under a multiple-use mission, including livestock grazing, energy and mineral development, recreation, timber production, watershed protection, and wildlife and fish habitat.10 Balancing the multiple uses across the national forest system has sometimes led to a lack of consensus regarding management decisions and practices.

- Bureau of Land Management (BLM), in the Department of the Interior (DOI), manages 246 million acres of public lands, also under a multiple-use mission of livestock grazing, energy and mineral development, recreation, timber production, watershed protection, and wildlife and fish habitat.11 Differences of opinion sometimes arise among and between users and land managers as a result of the multiple use opportunities on BLM lands.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), in DOI, manages 89 million acres as part of the National Wildlife Refuge System (NWRS) as well as additional surface, submerged, and offshore areas.12 FWS manages the NWRS through a dominant-use mission—to conserve plants and animals and associated habitats for the benefit of present and future generations. In addition, FWS administers each unit of the NWRS pursuant to any additional purposes specified for that unit.13 Other uses are permitted only to the extent that they are compatible with the conservation mission of the NWRS and any purposes identified for individual units. Determining compatibility can be challenging, but the FWS's stated mission generally has been seen to have helped reduce disagreements over refuge management and use.

- National Park Service (NPS), in DOI, manages 80 million acres in the National Park System. The NPS has a dual mission—to preserve unique resources and to provide for their enjoyment by the public. NPS laws, regulations, and policies emphasize the conservation of park resources in conservation/use conflicts. Tension between providing recreation and preserving resources has produced management challenges for NPS.

- Bureau of Ocean Management (BOEM), also in DOI, manages energy resources in areas of the outer continental shelf (OCS) covering approximately 1.7 billion acres located beyond state waters. These areas are defined in the Submerged Lands Act and the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (OCSLA).14 BOEM's mission is to balance energy independence, environmental protection, and economic development through responsible, science-based management of offshore conventional and renewable energy resources. BOEM schedules and conducts OCS oil and gas lease sales, administers existing oil and gas leases, and issues easements and leases for deploying renewable energy technologies,15 among other responsibilities.

CRS Products

CRS In Focus IF10585, The Federal Land Management Agencies, by Katie Hoover.

CRS Report R42656, Federal Land Management Agencies and Programs: CRS Experts, by R. Eliot Crafton.

CRS Report R45340, Federal Land Designations: A Brief Guide, coordinated by Laura B. Comay.

CRS In Focus IF10832, Federal and Indian Lands on the U.S.-Mexico Border, by Carol Hardy Vincent and James C. Uzel.

CRS Report R45265, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: An Overview, by R. Eliot Crafton.

CRS Report RS20158, National Park System: Establishing New Units, by Laura B. Comay.

CRS Report R43872, National Forest System Management: Overview, Appropriations, and Issues for Congress, by Katie Hoover.

Agency Acquisition and Disposal Authorities

Congress has granted the FLMAs various authorities to acquire and dispose of land. The extent of this authority differs considerably among the agencies. The BLM has relatively broad authority for both acquisitions and disposals under the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA).16 By contrast, NPS has no general authority to acquire land to create new park units or to dispose of park lands without congressional action. The FS authority to acquire lands is limited mostly to lands within or contiguous to the boundaries of a national forest, including the authority to acquire access corridors to national forests across nonfederal lands.17 The agency has various authorities to dispose of land, but they are relatively constrained and infrequently used. FWS has various authorities to acquire lands, but no general authority to dispose of its lands. For example, the Migratory Bird Conservation Act of 1929 grants FWS authority to acquire land for the National Wildlife Refuge System—using funds from sources that include the sale of hunting and conservation stamps—after state consultation and agreement.18

The current acquisition and disposal authorities form the backdrop for consideration of measures to establish, modify, or eliminate authorities, or to provide for the acquisition or disposal of particular lands. Congress also addresses acquisition and disposal policy in the context of debates on the role and goals of the federal government in owning and managing land generally.

CRS Product

CRS Report RL34273, Federal Land Ownership: Acquisition and Disposal Authorities, by Carol Hardy Vincent et al.

Funding Issues

Funding for federal land and FLMA natural resource programs presents an array of issues for Congress. The FLMAs receive their discretionary appropriations through Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies appropriations laws. In addition to other questions related directly to appropriations, some funding questions relate to the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF). Congress appropriates funds from the LWCF for land acquisition by federal agencies, outdoor recreation needs of states, and other purposes. Under debate are the levels, sources, and uses of funding and whether some funding should be continued as discretionary. A second set of questions relates to the compensation of states or counties for the presence of nontaxable federal lands and resources, including whether to revise or maintain existing payment programs. A third set of issues relates to the maintenance of assets by the agencies, particularly how to address their backlog of maintenance projects while achieving other government priorities.

CRS Products

CRS Report R44934, Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies: Overview of FY2019 Appropriations, by Carol Hardy Vincent.

CRS Report R43822, Federal Land Management Agencies: Appropriations and Revenues, coordinated by Carol Hardy Vincent.

CRS In Focus IF10381, Bureau of Land Management: FY2019 Appropriations, by Carol Hardy Vincent.

CRS In Focus IF10846, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: FY2019 Appropriations, by R. Eliot Crafton.

CRS In Focus IF10900, National Park Service: FY2019 Appropriations, by Laura B. Comay.

CRS In Focus IF11178, National Park Service: FY2020 Appropriations, by Laura B. Comay.

CRS In Focus IF11169, Forest Service: FY2019 Appropriations and FY2020 Request, by Katie Hoover.

Land and Water Conservation Fund

The Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965 was enacted to help preserve, develop, and assure access to outdoor recreation facilities to strengthen the health of U.S. citizens.19 The law created the Land and Water Conservation Fund in the U.S. Treasury as a funding source to implement its outdoor recreation purposes. The LWCF has been the principal source of monies for land acquisition for outdoor recreation by the four FLMAs. The LWCF also has funded a matching grant program to assist states with outdoor recreational needs and other federal programs with purposes related to lands and resources.

The provisions of the LWCF Act that provide for $900 million in specified revenues to be deposited in the fund annually have been permanently extended.20 Nearly all of the revenues are derived from oil and gas leasing in the OCS. Congress determines the level of discretionary appropriations each year, and yearly appropriations have fluctuated widely since the origin of the program. In addition to any discretionary appropriations, the state grant program receives (mandatory) permanent appropriations.21

There is a difference of opinion as to how funds in the LWCF should be allocated. Current congressional issues include deciding the amount to appropriate for land acquisition, the state grant program, and other purposes. Several other issues have been under debate, including whether to provide the fund with additional permanent appropriations; direct revenues from other activities to the LWCF; limit the use of funds for particular purposes, such as federal land acquisition; and require some of the funds to be used for certain purposes, such as facility maintenance. Another area of focus is the state grant program, with issues including the impact of anticipated increases in mandatory funding, the way in which funds are apportioned among the states, and the extent to which the grants should be competitive.

CRS Products

CRS In Focus IF10323, Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF): Frequently Asked Questions Related to Provisions Scheduled to Expire on September 30, 2018, by Carol Hardy Vincent and Bill Heniff Jr.

CRS Report RL33531, Land and Water Conservation Fund: Overview, Funding History, and Issues, by Carol Hardy Vincent.

CRS Report R44121, Land and Water Conservation Fund: Appropriations for "Other Purposes," by Carol Hardy Vincent.

Federal Payment and Revenue-Sharing Programs

As a condition of statehood, most states forever waived the right to tax federal lands within their borders. However, some assert that states or counties should be compensated for services related to the presence of federal lands, such as fire protection, police cooperation, or longer roads to skirt the federal property. Under federal law, state and local governments receive payments through various programs due to the presence of federally owned land.22 Some of these programs are run by specific agencies and apply only to that agency's land. Many of the payment programs are based on revenue generated from specific land uses and activities, while other payment programs are based on acreage of federal land and other factors. The adequacy, coverage, equity, and sources of the payments for all of these programs are recurring issues for Congress.

The most widely applicable onshore program, administered by DOI, applies to many types of federally owned land and is called Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILT).23 Each eligible county's PILT payment is calculated using a complex formula based on five factors, including federal acreage and population. Most counties containing the lands administered by the four FLMAs are eligible for PILT payments. Counties with NPS lands receive payments primarily under PILT. Counties containing certain FWS lands are eligible to receive PILT payments, and FWS also has an additional payment program for certain refuge lands, known as the Refuge Revenue Sharing program. In addition to PILT payments, counties containing FS and BLM lands also receive payments based primarily on receipts from revenue-producing activities on their lands. Some of the payments from these other programs will be offset in the county's PILT payment in the following year. One program (Secure Rural Schools, or SRS) compensated counties with FS lands or certain BLM lands in Oregon for declining timber harvests. The authorization for the SRS program expired after FY2018, and the last authorized payments are to be disbursed in FY2019.

The federal government shares the revenue from mineral and energy development, both onshore and offshore. Revenue collected (rents, bonuses, and royalties) from onshore mineral and energy development is shared 50% with the states, under the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 (less administrative costs).24 Alaska, however, receives 90% of all revenues collected on federal onshore leases (less administrative costs).

Revenue collected from offshore mineral and energy development on the outer continental shelf (OCS) is shared with the coastal states, albeit at a lower rate. The OCSLA allocates 27% of the revenue generated from certain federal offshore leases to the coastal states.25 Separately, the Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act of 2006 (GOMESA; P.L. 109-432) provided for revenue sharing at a rate of 37.5% for four coastal states,26 up to a collective cap.27 Some coastal states have advocated for a greater share of the OCS revenues based on the impacts oil and gas projects have on coastal infrastructure and the environment, while other states and stakeholders have contended that more of the revenue should go to the general fund of the Treasury or to other federal programs.

CRS Products

CRS Report RL31392, PILT (Payments in Lieu of Taxes): Somewhat Simplified, by Katie Hoover.

CRS Report R41303, Reauthorizing the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act of 2000, by Katie Hoover.

CRS Report R42404, Fish and Wildlife Service: Compensation to Local Governments, by R. Eliot Crafton.

CRS Report R42951, The Oregon and California Railroad Lands (O&C Lands): Issues for Congress, by Katie Hoover.

CRS Report R43891, Mineral Royalties on Federal Lands: Issues for Congress, by Marc Humphries.

CRS Report R42439, Compensating State and Local Governments for the Tax-Exempt Status of Federal Lands: What Is Fair and Consistent?, by Katie Hoover.

Deferred Maintenance

The FLMAs have maintenance responsibility for their buildings, roads and trails, recreation sites, and other infrastructure. Congress continues to focus on the agencies' deferred maintenance and repairs, defined as "maintenance and repairs that were not performed when they should have been or were scheduled to be and which are put off or delayed for a future period."28 The agencies assert that continuing to defer maintenance of facilities accelerates their rate of deterioration, increases their repair costs, and decreases their value and safety.

Congressional and administrative attention has centered on the NPS backlog, which has continued to increase from an FY1999 estimate of $4.25 billion in nominal dollars. Currently, DOI estimates deferred maintenance for NPS for FY2017 at $11.2 billion.29 Nearly three-fifths of the backlogged maintenance is for roads, bridges, and trails. The other FLMAs also have maintenance backlogs. DOI estimates that deferred maintenance for FY2017 for FWS is $1.4 billion and the BLM backlog is $0.8 billion. FS estimated its backlog for FY2017 at $5.0 billion, with approximately 70% for roads, bridges, and trails.30 Thus, the four agencies together had a combined FY2017 backlog estimated at $18.5 billion.

The backlogs have been attributed to decades of funding shortfalls to address capital improvement projects. However, it is not always clear how much total funding has been provided for deferred maintenance each year because some annual presidential budget requests and appropriations documents did not identify and aggregate all funds for deferred maintenance. Currently, there is debate over the appropriate level of funds to maintain infrastructure, whether to use funds from other discretionary or mandatory programs or sources, how to balance maintenance of the existing infrastructure with the acquisition of new assets, and the priority of maintaining infrastructure relative to other government functions.

CRS Products

CRS Report R43997, Deferred Maintenance of Federal Land Management Agencies: FY2007-FY2016 Estimates and Issues, by Carol Hardy Vincent.

CRS Report R44924, The National Park Service's Maintenance Backlog: Frequently Asked Questions, by Laura B. Comay.

CRS In Focus IF10987, Legislative Proposals for a National Park Service Deferred Maintenance Fund, by Laura B. Comay.

Climate Policy and Federal Land Management

Scientific evidence shows that the United States' climate has been changing in recent decades.31 This poses several interrelated and complex issues for the management of federal lands and their resources, in terms of mitigation, adaptation, and resiliency. Overall, climate change is introducing uncertainty about conditions previously considered relatively stable and predictable. Given the diversity of federal land and resources, concerns are wide-ranging and include invasive species, sea-level rise, wildlife habitat changes, and increased vulnerability to extreme weather events, as well as uncertainty about the effects of these changes on tourism and recreation. Some specific observed effects of climate change include a fire season that begins earlier and lasts longer in some locations, warmer winter temperatures that allow for a longer tourism season but also for various insect and disease infestations to persist in some areas, and habitat shifts that affect the status of sensitive species but may also increase forest productivity.32 Another concern is how climate change may affect some iconic federal lands, such as the diminishing size of the glaciers at Glacier National Park in Montana and several parks in Alaska, or the flooding of some wildlife refuges.33

The role of the FLMAs in responding to climate change is an area under debate. Some stakeholders are concerned that a focus on climate change adaptation may divert resources and attention from other agency activities and near-term challenges. Others see future climate conditions as representing an increased risk to the effective performance of agency missions and roles.

A related debate concerns the impact of energy production on federal lands. Both traditional sources of energy (nonrenewable fossil fuels such as oil, gas, and coal) and alternative sources of energy (renewable fuels such as solar, wind, and geothermal) are available on some federal lands. A 2018 report from the U.S. Geological Survey estimated that greenhouse gas emissions resulting from the extraction and use of fossil fuels produced on federal lands account for, on average, approximately 24% of national emissions for carbon dioxide, 7% for methane, and 1.5% for nitrous oxide.34 In addition, the report estimated that carbon sequestration on federal lands offset approximately 15% of those carbon dioxide emissions over the study period, 2005 through 2014. This, along with other factors, has contributed to questions among observers about the extent to which the agencies should provide access to and promote different sources of energy production on federal lands based on the effects on climate from that production. Since fossil fuel emissions contribute to climate change, some stakeholders concerned about climate change assert that the agencies should prioritize renewable energy production on federal lands over traditional energy sources. Others assert that, even with renewable energy growth, conventional sources will continue to be needed in the foreseeable future, and that the United States should pursue a robust traditional energy program to ensure U.S. energy security and remain competitive with other nations, including continuing to make fossil fuel production available on federal lands.

Specific legislative issues for Congress may include the extent to which the FLMAs manage in furtherance of long-term climate policy goals, and proposals to restructure or improve collaboration among the FLMAs regarding climate change activities and reporting.

CRS Products

CRS Report R43915, Climate Change Adaptation by Federal Agencies: An Analysis of Plans and Issues for Congress, coordinated by Jane A. Leggett.

Energy and Mineral Resources

Much of the onshore federal estate is open to energy and mineral exploration and development, including BLM and many FS lands. However, many NPS lands and designated wilderness areas, as well as certain other federal lands, have been specifically withdrawn from exploration and development.35 Most offshore federal acres on the U.S. outer continental shelf are also available for exploration and development, although BOEM has not scheduled lease sales in all available areas.36 Energy production on federal lands contributes to total U.S. energy production. For example, in 2017, as a percentage of total U.S. production, approximately 24% of crude oil and 13% of natural gas production came from federal lands.37 Coal production from federal lands has consistently accounted for about 40% of annual U.S. coal production over the past decade.

Federal lands also are available for renewable energy projects. Geothermal capacity on federal lands represents 40% of U.S. total geothermal electric generating capacity.38 Solar and wind energy potential on federal lands is growing and, based on BLM-approved projects, there is potential for 3,300 megawatts (MW) of wind and 6,300 MW of solar energy on federal lands.39 The first U.S. offshore wind farm began regular operations in 2016, and BOEM has issued 13 wind energy leases off the coasts of eight East Coast states.

The 116th Congress may continue debate over issues related to access to and availability of onshore and offshore federal lands for energy and mineral development. This discussion includes how to balance energy and mineral development with environmental protection, postproduction remediation, and other uses for those federal lands. Some would like to open more federal lands for energy development, whereas others have sought to retain or increase restrictions and withdrawals for certain areas they consider too sensitive or inappropriate for traditional and/or renewable energy development. Congress also continues to focus on the energy and mineral permitting processes, the timeline for energy and mineral development, and issues related to royalty collections. Other issues may include the federal management of split estates, which occur when the surface and subsurface rights are held by different entities.

Onshore Resources

Oil and Natural Gas

Onshore oil and natural gas produced on federal lands in 2017 accounted for 5% and 9% of total U.S. oil and gas production, respectively.40 Development of oil, gas, and coal on federal lands is governed primarily by the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 (MLA).41 The MLA authorizes the Secretary of the Interior—through BLM—to lease the subsurface rights to most BLM and FS lands that contain fossil fuel deposits, with the federal government retaining title to the lands.42 Leases include an annual rental fee and a royalty payment generally determined by a percentage of the value or amount of the resource removed or sold from the federal land. Congress has at times debated raising the onshore royalty rate for federal oil and gas leases, which has remained at the statutory minimum of 12.5% since the enactment of the MLA in 1920.

Access to federal lands for energy and mineral development has been controversial. The oil and gas industry contends that entry into currently unavailable areas is necessary to ensure future domestic oil and gas supplies. Opponents maintain that the restricted lands are unique or environmentally sensitive and that the United States could realize equivalent energy gains through conservation and increased exploration on current leases or elsewhere. Another controversial issue is the permitting process and timeline, which the Energy Policy Act of 2005 (EPAct05) revised for oil and gas permits.43 An additional contested issue has been whether to pursue oil and gas development in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in northeastern Alaska. P.L. 115-97, enacted in December 2017, provided for the establishment of an oil and gas program in the refuge.

CRS Products

CRS In Focus IF10127, Energy and Mineral Development on Federal Land, by Marc Humphries.

CRS Report R42432, U.S. Crude Oil and Natural Gas Production in Federal and Nonfederal Areas, by Marc Humphries.

CRS Report RL33872, Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR): An Overview, by Laura B. Comay, Michael Ratner, and R. Eliot Crafton.

CRS Report R43891, Mineral Royalties on Federal Lands: Issues for Congress, by Marc Humphries.

Coal

Congress debates several issues regarding coal production on federal lands, including how to balance coal production against other resource values and the potential effects of coal production on issues related to climate change. Other concerns include how to assess the value of the coal resource, what is the fair market value for the coal, and what should be the government's royalty. A 2013 GAO analysis found inconsistencies in how BLM evaluated and documented federal coal leases.44 In addition, a 2013 DOI Inspector General report found that BLM may have violated MLA provisions by accepting below-cost bids for federal coal leases.45 The Obama Administration issued a new rule for the valuation of coal, which reaffirmed that the value for royalty purposes is at or near the mine site and that gross proceeds from arm's-length contracts are the best indication of market value.46 This rule was repealed by the Trump Administration on August 7, 2017 (to comply with Executive Order (E.O.) 13783),47 returning to the previous valuation rules in place.48 E.O. 13783 also lifted "any and all" moratoria on federal coal leasing put in place by the Obama Administration.

CRS Products

CRS Report R44922, The U.S. Coal Industry: Historical Trends and Recent Developments, by Marc Humphries.

Renewable Energy on Federal Land

Both BLM and FS manage land that is considered suitable for renewable energy generation and as such have authorized projects for geothermal, wind, solar, and biomass energy production. BLM manages the solar and wind energy programs on about 20 million acres for each program and about 800 geothermal leases on federal lands.49 Interest in renewable energy production comes in part from concern over the impact of emissions from fossil fuel-fired power plants and the related adoption of statewide renewable portfolio standards that require electricity producers to supply a certain minimum share (which varies by state) of electricity from renewable sources. Congressional interest in renewable energy resources on onshore federal lands has focused on whether to expand the leasing program for wind and solar projects versus maintaining the current right-of-way authorization process, and how to balance environmental concerns with the development and production of these resources.

- Geothermal Energy. Geothermal energy is produced from heat stored under the surface of the earth. Geothermal leasing on federal lands is conducted under the authority of the Geothermal Steam Act of 1970, as amended,50 and is managed by BLM, in consultation with FS.

- Wind and Solar Energy. Development of solar and wind energy sources on BLM and FS lands is governed primarily by right-of-way authorities under Title V of FLPMA.51 The potential wildlife impacts from wind turbines and water supply requirements from some solar energy infrastructure remain controversial. Issues for Congress include how to manage the leasing process and whether or how to balance such projects against other land uses identified by statute.

- Woody Biomass.52 Removing woody biomass from federal lands for energy production has received special attention because of biomass's widespread availability. Proponents assert that removing biomass density on NFS and BLM lands also provides landscape benefits (e.g., improved forest resiliency, reduced risk of catastrophic wildfires). Opponents, however, identify that incentives to use wood and wood waste might increase land disturbances on federal lands, and they are concerned about related wildlife, landscape, and ecosystem impacts. Other issues include the role of the federal government in developing and supporting emerging markets for woody biomass energy production, and whether to include biomass removed from federal lands in the Renewable Fuel Standard.53

Locatable Minerals

Locatable minerals include metallic minerals (e.g., gold, silver, copper), nonmetallic minerals (e.g., mica, gypsum), and other minerals generally found in the subsurface.54 Developing these minerals on federal lands is guided by the General Mining Law of 1872. The law, largely unchanged since enactment, grants free access to individuals and corporations to prospect for minerals in public domain lands,55 and allows them, upon making a discovery, to stake (or "locate") a claim on the deposit. A claim gives the holder the right to develop the minerals and apply for a patent to obtain full title of the land and minerals. Congress has imposed a moratorium on mining claim patents in the annual Interior appropriations laws since FY1995, but has not restricted the right to stake claims or extract minerals.

The mining industry supports the claim-patent system, which offers the right to enter federal lands and prospect for and develop minerals. Critics consider the claim-patent system to not properly value publicly owned resources because royalty payments are not required and the amounts paid to maintain a claim and to obtain a patent are small. New mining claim location and annual claim maintenance fees are currently $37 and $155 per claim, respectively.56

Offshore Resources

The federal government is responsible for managing energy resources in approximately 1.7 billion acres of offshore areas belonging to the United States (see Figure 1). These offshore resources are governed by the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act of 1953 (OCSLA), as amended, and management involves balancing domestic energy demands with protection of the environment and other factors.57 Policymakers have debated access to ocean areas for offshore drilling, weighing factors such as regional economic needs, U.S. energy security, the vulnerability of oceans and shoreline communities to oil-spill risks, and the contribution of oil and gas drilling to climate change. Some support banning drilling in certain regions or throughout the OCS, through congressional moratoria, presidential withdrawals, and other measures. Others contend that increasing offshore oil and gas development will strengthen and diversify the nation's domestic energy portfolio and that drilling can be done in a safe manner that protects marine and coastal areas.

Offshore Oil and Gas Leases

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management administers approximately 2,600 active oil and gas leases on nearly 14 million acres on the OCS.58 Under the OCSLA, BOEM prepares forward-looking, five-year leasing programs to govern oil and gas lease sales. BOEM released its final leasing program for 2017-2022 in November 2016, under the Obama Administration. The program schedules 10 lease sales in the Gulf of Mexico region and 1 in the Alaska region, with no sales in the Atlantic or Pacific regions.59 In January 2018, under the Trump Administration, BOEM released a draft proposed program for 2019-2024, which would replace the final years of the Obama Administration program.60 The program proposes 12 lease sales in the Gulf of Mexico region, 19 sales in the Alaska region, 9 lease sales in the Atlantic region, and 7 lease sales in the Pacific region. The proposed sales would cover all U.S. offshore areas not prohibited from oil and gas development, including areas with both high and low levels of estimated resources.61 The draft proposal is the first of three program versions; under the OCSLA process, subsequent versions could remove proposed lease sales but could not add new sales.62

Under the OCSLA,63 the President may withdraw unleased lands on the OCS from leasing disposition. President Obama indefinitely withdrew from leasing disposition large portions of the Arctic OCS as well as certain areas in the Atlantic region, but these withdrawals were modified by President Trump.64 Congress also has established leasing moratoria; for example, the GOMESA established a moratorium on preleasing, leasing, and related activity in the eastern Gulf of Mexico through June 2022.65

The 116th Congress may consider multiple issues related to offshore oil and gas exploration, including questions about allowing or prohibiting access to ocean areas and how such changes may impact domestic energy markets and affect the risk of oil spills. Other issues concern the use of OCS revenues and the extent to which they should be shared with coastal states (see "Federal Payment and Revenue-Sharing Programs" section).

Offshore Renewable Energy Sources

BOEM also is responsible for managing leases, easements, and rights-of-way to support development of energy from renewable ocean energy resources, including offshore wind, thermal power, and kinetic forces from ocean tides and waves.66 As of January 2019, BOEM had issued 13 offshore wind energy leases in areas off the coasts of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, New York, New Jersey, and North Carolina.67 In December 2016, the first U.S. offshore wind farm, off the coast of Rhode Island, began regular operations. Issues for Congress include whether to take steps to facilitate the development of offshore wind and other renewables, such as through research and development, project loan guarantees, extension of federal tax credits for renewable energy production, or oversight of regulatory issues for these emerging industries.

CRS Products

CRS Report R44504, The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management's Five-Year Program for Offshore Oil and Gas Leasing: History and Final Program for 2017-2022, by Laura B. Comay, Marc Humphries, and Adam Vann.

CRS Report R44692, Five-Year Program for Federal Offshore Oil and Gas Leasing: Status and Issues in Brief, by Laura B. Comay.

CRS Report RL33404, Offshore Oil and Gas Development: Legal Framework, by Adam Vann.

Forest Management

Management of federal forests presents several policy questions for Congress. For instance, there are questions about the appropriate level of timber harvesting on federal forest lands, particularly FS and BLM lands, and how to balance timber harvesting against the other statutory uses and values for these federal lands. Further, Congress may debate whether or how the agencies use timber harvesting or other active forest management techniques to achieve other resource-management objectives, such as improving wildlife habitat or improving a forest's resistance and resilience to disturbance events (e.g., wildfire, ice storm).

FS manages 145 million acres of forests and woodlands in the National Forest System (NFS).68 In FY2018, approximately 2.8 billion board feet of timber and other forest products were harvested from NFS lands, at a value of $188.8 million.69 BLM manages approximately 38 million acres of forest and woodlands.70 The vast majority are public domain forests, managed under the principles of multiple use and sustained yield as established by FLPMA.71 The 2.6 million acres of Oregon & California (O&C) Railroad Lands in western Oregon, however, are managed under a statutory direction for permanent forest production, as well as watershed protection, recreation, and contributing to the economic stability of local communities and industries.72 In FY2018, approximately 177.8 million board feet of timber and other forest products were harvested from BLM lands, at a value of $41.3 million.73 The NPS and FWS have limited authorities to cut, sell, or dispose of timber from their lands and have established policies to do so only in certain cases, such as controlling for insect and disease outbreaks.

In the past few years, the ecological condition of the federal forests has been one focus of discussion. Many believe that federal forests are ecologically degraded, contending that decades of wildfire suppression and other forest-management decisions have created overgrown forests overstocked with biomass (fuels) that are susceptible to insect and disease outbreaks and can serve to increase the spread or intensity of wildfires. These observers advocate rapid action to improve forest conditions, including activities such as prescribed burning, forest thinning, salvaging dead and dying trees, and increased commercial timber production. Critics counter that authorities to reduce fuel levels are adequate, treatments that remove commercial timber degrade other ecosystem conditions and waste taxpayer dollars, and expedited processes for treatments may reduce public oversight of commercial timber harvesting. The 115th Congress enacted several provisions intended to expedite specific forest management projects on federal land and encourage forest restoration projects across larger areas, including projects which involve nonfederal landowners.74

CRS Products

CRS Report R45696, Forest Management Provisions Enacted in the 115th Congress, by Katie Hoover et al.

CRS Report R45688, Timber Harvesting on Federal Lands, by Anne A. Riddle.

CRS Report R43872, National Forest System Management: Overview, Appropriations, and Issues for Congress, by Katie Hoover.

CRS Report R42951, The Oregon and California Railroad Lands (O&C Lands): Issues for Congress, by Katie Hoover.

Range Management

Livestock Grazing

Management of federal rangelands, particularly by BLM and FS, presents an array of policy matters for Congress. Several issues pertain to livestock grazing. There is debate about the appropriate fee that should be charged for grazing private livestock on BLM and FS lands, including what criteria should prevail in setting the fee. Today, these federal agencies charge fees under a formula established by law in 1978, then continued indefinitely through an executive order issued by President Reagan in 1986.75 The BLM and FS are generally charging a 2019 grazing fee of $1.3576 per animal unit month (AUM)77 for grazing on their lands. Conservation groups, among others, generally seek increased fees to recover program costs or approximate market value, whereas livestock producers who use federal lands want to keep fees low to sustain ranching and rural economies.

The BLM and FS issue to ranchers permits and/or leases that specify the terms and conditions for grazing on agency lands. Permits and leases generally cover a 10-year period and may be renewed. Congress has considered whether to extend the permit/lease length (e.g., to 20 years) to strengthen the predictability and continuity of operations. Longer permit terms have been opposed because they potentially reduce the opportunities to analyze the impact of grazing on lands and resources.

The effect of livestock grazing on rangelands has been part of an ongoing debate on the health and productivity of rangelands. Due to concerns about the impact of grazing on rangelands, some recent measures would restrict or eliminate grazing, for instance, through voluntary retirement of permits and leases and subsequent closure of the allotments to grazing. These efforts are opposed by those who assert that ranching can benefit rangelands and who support ranching on federal lands for not only environmental but lifestyle and economic reasons. Another focus of the discussion on range health and productivity is the spread of invasive and noxious weeds. (See "Invasive Species" section, below.)

Wild Horses and Burros

There is continued congressional interest in management of wild horses and burros, which are protected on BLM and FS lands under the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971.78 Under the act, the agencies inventory horse and burro populations on their lands to determine appropriate management levels (AMLs). Most of the animals are on BLM lands, although both BLM and FS have populations exceeding their national AMLs. BLM estimates the maximum AML at 26,690 wild horses and burros, and it estimates population on the range at 81,951.79 Furthermore, off the range, BLM provides funds to care for 50,864 additional wild horses and burros in short-term corrals, long-term (pasture) holding facilities, and eco-sanctuaries.80 The Forest Service estimates population on lands managed by the agency at 9,300 wild horses and burros.81

The agencies are statutorily authorized to remove excess animals from the range and use a variety of methods to meet AML. This includes programs to adopt and sell animals, to care for animals off-range, to administer fertility control, and to establish ecosanctuaries. Questions for Congress include the sufficiency of these authorities and programs for managing wild horses and burros. Another controversial question is whether the agencies should humanely destroy excess animals, as required under the 1971 law, or whether Congress should continue to prohibit the BLM from using funds to slaughter healthy animals. Additional topics of discussion center on the costs of management, particularly the relatively high cost of caring for animals off-range.82 Other options focus on keeping animals on the range, such as by expanding areas for herds and/or changing the method for determining AML.

CRS Products

CRS Report RS21232, Grazing Fees: Overview and Issues, by Carol Hardy Vincent.

CRS In Focus IF11060, Wild Horse and Burro Management: Overview of Costs, by Carol Hardy Vincent.

Recreation

The abundance and diversity of recreational uses of federal lands and waters has increased the challenge of balancing different types of recreation with each other and with other land uses. One issue is how—or whether—fees should be collected for recreational activities on federal lands. The Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act (FLREA) established a recreation fee program for the four FLMAs and the Bureau of Reclamation.83 The authorization ends on September 30, 2020.84 FLREA authorizes the agencies to charge, collect, and spend fees for recreation on their lands, with most of the money remaining at the collecting site. The 116th Congress faces issues including whether to let lapse, extend, make permanent, or amend the program. Current oversight issues for Congress relate to various aspects of agency implementation of the fee program, including the determination of fee changes, use of collected revenue, and pace of obligation of fee collections. Supporters of the program contend that it sets fair and similar fees among agencies and keeps most fees on-site for improvements that visitors desire. Some support new or increased fees or full extension of the program to other agencies, especially the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Among critics, some oppose recreation fees in general. Others assert that fees are appropriate for fewer agencies or types of lands, that the fee structure should be simplified, or that more of the fees should be used to reduce agency maintenance backlogs.

Another contentious issue is the use of off-highway vehicles (OHVs)—all-terrain vehicles, snowmobiles, personal watercraft, and others—on federal lands and waters. OHV use is a popular recreational activity on BLM and FS land, while NPS and FWS have fewer lands allowing them. OHV supporters contend that the vehicles facilitate visitor access to hard-to-reach natural areas and bring economic benefits to communities serving riders. Critics raise concerns about disturbance of nonmotorized recreation and potential damage to wildlife habitat and ecosystems. Issues for Congress include broad questions of OHV access and management, as well as OHV use at individual parks, forests, conservation areas, and other federal sites.

Access to opportunities on federal lands for hunting, fishing, and recreational shooting (e.g., at shooting ranges) is of perennial interest to Congress. Hunting and fishing are allowed on the majority of federal lands, but some contend they are unnecessarily restricted by protective designations, barriers to physical access, and agency planning processes. Others question whether opening more FLMA lands to hunting, fishing, and recreational shooting is fully consistent with good game management, public safety, other recreational uses, resource management, and the statutory purposes of the lands. Issues for Congress include questions of whether or how to balance hunting and fishing against other uses, as well as management of equipment used for hunting and fishing activities, including types of firearms and composition of ammunition and fishing tackle.

CRS Products

CRS In Focus IF10151, Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act: Overview and Issues, by Carol Hardy Vincent.

CRS Report R45103, Hunting and Fishing on Federal Lands and Waters: Overview and Issues for Congress, by R. Eliot Crafton.

CRS In Focus IF10746, Hunting, Fishing, and Related Issues in the 115th Congress, by R. Eliot Crafton.

Other Land Designations

Congress, the President, and some executive branch officials may establish individual designations on federal lands. Although many designations are unique, some have been more commonly applied, such as national recreation area, national scenic area, and national monument. Congress has conferred designations on some nonfederal lands, such as national heritage areas, to commemorate, conserve, and promote important natural, scenic, historical, cultural, and recreational resources. Congress and previous Administrations also have designated certain offshore areas as marine national monuments or sanctuaries. Controversial issues involve the types, locations, and management of such designations, and the extent to which some designations should be altered, expanded, or reduced.

In addition, Congress has created three cross-cutting systems of federal land designations to preserve or emphasize particular values or resources, or to protect the natural conditions for biological, recreation, or scenic purposes. These systems are the National Wilderness Preservation System, the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System, and the National Trails System. The units of these systems can be on one or more agencies' lands, and the agencies manage them within parameters set in statute.

CRS Products

CRS Report R45340, Federal Land Designations: A Brief Guide, coordinated by Laura B. Comay.

CRS Report RL33462, Heritage Areas: Background, Proposals, and Current Issues, by Laura B. Comay and Carol Hardy Vincent.

CRS Report R41285, Congressionally Designated Special Management Areas in the National Forest System, by Katie Hoover.

National Monuments and the Antiquities Act

The Antiquities Act of 1906 authorizes the President to proclaim national monuments on federal lands that contain historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, or other objects of natural, historic, or scientific interest.85 The President is to reserve "the smallest area compatible with the proper care and management of the objects to be protected."86 Seventeen of the 20 Presidents since 1906, including President Trump, have used this authority to establish, enlarge, diminish, or make other changes to proclaimed national monuments. Congress has modified many of these proclamations, abolished some monuments, and created monuments under its own authority.

Since the enactment of the Antiquities Act, presidential establishment of monuments sometimes has been contentious. Most recently, the Trump Administration has reviewed and recommended changes to some proclaimed national monuments,87 and President Trump has modified and established some monuments.

Congress continues to address the role of the President in proclaiming monuments. Some seek to impose restrictions on the President's authority to proclaim monuments. Among the bills considered in recent Congresses are those to block monuments from being declared in particular states; limit the size or duration of withdrawals; require the approval of Congress, the pertinent state legislature, or the pertinent governor before a monument could be proclaimed; or require the President to follow certain procedures prior to proclaiming a new monument.

Others promote the President's authority to act promptly to protect valuable resources on federal lands that may be vulnerable, and they note that Presidents of both parties have used the authority for over a century. They favor the Antiquities Act in its present form, asserting that the courts have upheld monument designations and that large segments of the public support monument designations for the recreational, preservation, and economic benefits that such designations can bring.

CRS Products

CRS Report R41330, National Monuments and the Antiquities Act, by Carol Hardy Vincent.

CRS Report R44988, Executive Order for Review of National Monuments: Background and Data, by Carol Hardy Vincent and Laura A. Hanson.

CRS Report R44886, Monument Proclamations Under Executive Order Review: Comparison of Selected Provisions, by Carol Hardy Vincent and Laura A. Hanson.

Wilderness and Roadless Areas

In 1964, the Wilderness Act created the National Wilderness Preservation System, with statutory protections that emphasize preserving certain areas in their natural states. Units of the system can be designated only by Congress. Many bills to designate wilderness areas have been introduced in each Congress. As of March 1, 2019, there were 802 wilderness areas, totaling over 111 million acres in 44 states (and Puerto Rico) and managed by all four of the FLMAs.88 A wilderness designation generally prohibits commercial activities, motorized access, and human infrastructure from wilderness areas, subject to valid existing rights. Advocates propose wilderness designations to preserve the generally undeveloped conditions of the areas. Opponents see such designations as preventing certain uses and potential economic development in rural areas where such opportunities are relatively limited.

Designation of new wilderness areas can be controversial, and questions persist over the management of areas being considered for wilderness designation. FS reviews the wilderness potential of NFS lands during the forest planning process and recommends any identified potential wilderness areas for congressional consideration.89 Management activities or uses that may reduce the wilderness potential of a recommended wilderness area may be restricted.90

Questions also persist over BLM wilderness study areas (WSAs).91 These WSAs are the areas BLM studied as potential wilderness and made subsequent recommendations to Congress regarding their suitability for designation as wilderness. BLM is required by FLPMA to protect the wilderness characteristics of WSAs, meaning that many uses in these areas are restricted or prohibited. Congress has designated some WSAs as wilderness, and has also included legislative language releasing BLM from the requirement to protect the wilderness characteristics of other WSAs.

FS also manages approximately 58 million acres of lands identified as "inventoried roadless areas."92 These lands are not part of the National Wilderness Preservation System, but certain activities—such as road construction or timber harvesting—are restricted on these lands, with some exceptions. The Clinton and George W. Bush Administrations each promulgated different roadless area regulations. Both were heavily litigated; however, the Clinton policy to prohibit many activities on roadless areas remains intact after the Supreme Court refused to review a lower court's 2012 decision striking down the Bush rule.93 In 2018, the Forest Service initiated a rulemaking process to develop a new roadless rule specific to the national forests in the state of Alaska.94

CRS Products

CRS Report RL31447, Wilderness: Overview, Management, and Statistics, by Katie Hoover.

CRS Report R41610, Wilderness: Issues and Legislation, by Katie Hoover and Sandra L. Johnson.

The National Wild and Scenic Rivers System and the National Trails System

Congress established the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System with the passage of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968.95 The act established a policy of preserving designated free-flowing rivers for the benefit and enjoyment of present and future generations. River units designated as part of the system are classified and administered as wild, scenic, or recreational rivers, based on the condition of the river, the amount of development in the river or on the shorelines, and the degree of accessibility by road or trail at the time of designation. The system contains both federal and nonfederal river segments. Typically, rivers are added to the system by an act of Congress, but may also be added by state nomination with the approval of the Secretary of the Interior. As of March 1, 2019, there are more than 200 river units with roughly 13,300 miles in 40 states and Puerto Rico, administered by all four FLMAs, or by state, local, or tribal governments.96

Designation and management of lands within river corridors has been controversial in some cases. Issues include concerns about private property rights and water rights within designated river corridors. Controversies have arisen over state or federal projects prohibited within a corridor, such as construction of major highway crossings, bridges, or other activities that may affect the flow or character of the designated river segment. The extent of local input in developing river management plans is another recurring issue.

The National Trails System Act of 1968 authorized a national system of trails, across federal and nonfederal lands, to provide additional outdoor recreation opportunities and to promote access to the outdoor areas and historic resources of the nation.97 The system today consists of four types of trails and can be found in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. This includes 11 national scenic trails and 19 national historic trails that covers roughly 55,000 miles.98 In addition, almost 1,300 national recreation trails and 7 connecting-and-side trails have been established administratively as part of the system. National trails are administered by NPS, FS, and BLM, in cooperation with appropriate state and local authorities. Most recreation uses are permitted, as are other uses or facilities that do not substantially interfere with the nature and purposes of the trail. However, motorized vehicles are prohibited on many trails.

Ongoing issues for Congress include whether to designate additional trails, whether or how to balance trail designation with other potential land uses, what activities should be permitted on trails, and what portion of trail funding should be from federal versus nonfederal sources. Some Members have expressed interest in new types of trails for the system, such as "national discovery trails," which would be interstate trails connecting representative examples of metropolitan, urban, rural, and backcountry regions.

CRS Products

CRS Report R42614, The National Wild and Scenic Rivers System: A Brief Overview, by Sandra L. Johnson and Laura B. Comay.

CRS Report R43868, The National Trails System: A Brief Overview, by Sandra L. Johnson and Laura B. Comay.

National Marine Sanctuaries and Marine National Monuments

The National Marine Sanctuaries Act (NMSA)99 authorizes the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to designate specific areas for protection of their ecological, aesthetic, historical, cultural, scientific, or educational qualities. The NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries serves as the trustee for the 13 national marine sanctuaries (NMSs) designated under NMSA. Sanctuaries are located in marine areas and waters under state or federal jurisdiction. Sites are designated for specific reasons, such as protecting cultural artifacts (e.g., sunken vessels), particular species (e.g., humpback whales), or unique areas and entire ecosystems (e.g., Monterey Bay). Two areas currently under consideration for designation are Mallows Bay, Potomac River, MD, and Lake Michigan, WI.100

The NMSA requires the development and implementation of management plans for each sanctuary, which provide the basis for managing or limiting incompatible activities. For most NMSs, questions related to developing or amending management plans have focused on identifying and limiting incompatible activities.

Five large marine national monuments have been designated by the President under the Antiquities Act, the most recent being the Northeast Canyons and Seamounts Marine National Monument in 2016,101 the first designated in the Atlantic Ocean.102 Within the monuments, the removing, taking, harvesting, possessing, injuring, or damaging of monument resources is prohibited except as provided under regulated activities. For example, some exceptions have been provided for recreational fishing and subsistence use within certain marine national monuments. All five marine national monuments are managed cooperatively by the Department of the Interior (FWS) and Department of Commerce (NOAA).103

One of the main differences between national marine sanctuaries and marine national monuments is their designation process. While monuments are designated by presidential proclamation or through congressional legislation, the NMS designation process is an administrative action, requiring nomination, public scoping, public comment, and congressional and state review prior to the Secretary of Commerce's approval of the designation. Some stakeholders from extractive industries, such as the fishing industry, have voiced concerns that the national monument designation process does not provide opportunities to examine the tradeoffs between resource protection and resource use. On the other hand, some environmentalists have voiced concerns with the low number of NMS designations and what they see as inadequate protection of some sanctuary resources, such as fish populations. Some observers question whether the overriding purpose of the NMSA is to preserve and protect marine areas or to create multiple use management areas.104 Most agree that the designation and management of national marine sanctuaries and marine national monuments will continue to inspire debate over the role of marine protected areas. The Trump Administration has reviewed and recommended changes to the size and management of some marine national monuments.105

Species Management

Each FLMA has a responsibility to manage the plant and animal resources under its purview. An agency's responsibilities may be based on widely applicable statutes or directives, including the Endangered Species Act, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act, executive orders, and other regulations. Species management could also be based on authorities specific to each FLMA. In addition, each FLMA must work closely with state authorities to address species management issues.

In the case of the National Wildlife Refuge System (administered by FWS), the conservation of plants and animals is the mission of the system, and other uses are allowed to the extent they are compatible with that mission and any specific purposes of an individual system unit.106 While most refuges are open for public enjoyment, some refuges or parts of refuges (such as island seabird colonies) might be closed to visitors to preserve natural resources. For the National Park System, resource conservation (including wildlife resources) is part of the National Park Service's dual mission, shared with the other goal of public enjoyment.107 The FS and BLM have multiple use missions, with species management being one of several agency responsibilities.108

The federal land management agencies do not exercise their wildlife authorities alone. Often, Congress has directed federal agencies to share management of their wildlife resources with state agencies.109 For example, where game species are found on federal land and hunting is generally allowed on that land, federal agencies work with states on wildlife censuses and require appropriate state licenses to hunt on the federal lands.110 In addition, federal agencies often cooperate with states to enhance wildlife habitat for the benefit of both jurisdictions.

The four FLMAs do not each maintain specific data on how many acres of land are open to hunting, fishing, and recreational shooting. However, both BLM and FS are required to open lands under their administration to hunting, fishing, and recreational shooting, subject to any existing and applicable law, unless the respective Secretary specifically closes an area.111 Both agencies estimate that nearly all of their lands are open to these activities.112 FWS is required to report the number of refuges open to hunting and fishing as well as the acreage available for hunting on an annual basis.113 As of FY2017, there were 277 refuges open to fishing and 336 refuges open to hunting, providing access to 86 million acres for hunting.114 Congress frequently considers species management issues, such as balancing land and resources use, providing access to hunting and fishing on federal lands, and implementing endangered species protections.

Endangered Species

The protection of endangered and threatened species—under the 1973 Endangered Species Act (ESA)115—can be controversial due to balancing the needs for natural resources use and development and species protection. Under the ESA, all federal agencies must "utilize their authorities in furtherance of the purposes of this Act by carrying out programs for the conservation of endangered species and threatened species listed pursuant to ... this Act."116 As a result, the FLMAs consider species listed as threatened or endangered in their land management plans, timber sales, energy or mineral leasing plans, and all other relevant aspects of their activities that might affect listed species. They consult with FWS (or NMFS, for most marine species and for anadromous fish such as salmon) about those effects. The majority of these consultations result in little or no change in the actions of the land managers.

Congress has considered altering ESA implementation in various ways. For example, bills were introduced in the 115th Congress that would have redefined the process for listing a species, defined the types of data used to evaluate species, and changed the types of species that can be listed under ESA, among others. Debate has also centered on certain species, particularly where conservation of species generates conflict over resources in various habitats. Examples of these species include sage grouse (energy and other resources in sage brush habitat), grey wolves (ranching), and polar bears (energy development in northern Alaska), among others. Proposals resulting from issues regarding certain species include granting greater authority to states over whether a species may be listed, changing the listing status of a species, and creating special conditions for the treatment of a listed species.

CRS Products

CRS Report RL31654, The Endangered Species Act: A Primer, by Pervaze A. Sheikh.

CRS Report RL32992, The Endangered Species Act and "Sound Science," by Pervaze A. Sheikh.

CRS Report R40787, Endangered Species Act (ESA): The Exemption Process, by Pervaze A. Sheikh.

Invasive Species

While habitat loss is a major factor in the decline of species, invasive species have long been considered the second-most-important factor.117 Invasive species—nonnative or alien species that cause or are likely to cause harm to the environment, the economy, or human health upon introduction, establishment, and spread—have the potential to affect habitats and people across the United States and U.S. territories, including on federal lands and waters.118 For example, gypsy moths have been a pest in many eastern national forests as well as Shenandoah National Park. A fungus causing white-nose syndrome has caused widespread mortality in bat populations in the central and eastern states, including those in caves on national park and national forest lands. Burmese pythons prey on native species of birds, mammals, and reptiles in south Florida, including in the Everglades National Park. Many stakeholders believe the most effective way to deal with invasive species is to prevent their introduction and spread. For species already introduced, finding effective management approaches is important, though potentially difficult or controversial. Control efforts can be complex and expensive, and may require collaboration and coordination between multiple stakeholders.

Addressing invasive species is a responsibility shared by several federal agencies, in addition to the FLMAs.119 These agencies are required to plan and carry out control activities and to develop strategic plans to implement such activities.120 Control activities are required to manage invasive populations, prevent or inhibit the introduction and spread invasive species, and to restore impacted areas. Further, agencies must consider both ecological and economic aspects in developing their strategic plans and implementing control activities, and they must coordinate with state, local, and tribal representatives. Legislation to address the introduction and spread of invasive species as well as the impacts that arise from these species is of perennial interest to Congress.

CRS Product

CRS Report R43258, Invasive Species: Major Laws and the Role of Selected Federal Agencies, by Renée Johnson, R. Eliot Crafton, and Harold F. Upton.

CRS In Focus IF11011, Invasive Species: A Brief Overview, by R. Eliot Crafton and Sahar Angadjivand.

Wildfire Management

Wildfire is a concern because it can lead to loss of human life, damage communities and timber resources, and affect soils, watersheds, water quality, and wildlife. Management of wildfire—an unplanned and unwanted wildland fire—includes preparedness, suppression, fuel reduction, site rehabilitation, and more.121 A record-setting 10.1 million acres burned in 2015 due to wildfire, and 10.0 million acres burned two years later in 2017.122 In 2018, 8.8 million acres burned.

The federal government is responsible for managing wildfires that begin on federal land. FS and DOI have overseen wildfire management, with FS receiving approximately two-thirds of federal funding.123 Wildfire management funding—including supplemental appropriations—has averaged $3.8 billion annually over the last 10 years (FY2009 through FY2018), ranging from a low of $2.7 billion in FY2012 to a high of $4.9 billion in both FY2016 and FY2018.124

Congressional activity regarding wildfire management typically peaks during the fire season, and during the early part of the budget process.125 Legislative issues for Congress include oversight of the agencies' fire management activities and other wildland management practices that have altered fuel loads over time, and consideration of programs and processes for reducing fuel loads. Funding also is a perennial concern, particularly for suppression purposes, an activity for which costs are generally rising but vary annually and are difficult to predict. The 115th Congress enacted a new adjustment to the discretionary spending limits for wildfire suppression operations, starting in FY2020.126 This means that Congress can appropriate some wildfire suppression funds—subject to certain criteria—effectively outside of the discretionary spending limits. There is also congressional interest in the federal roles and responsibilities for wildfire protection, response, and damages, including activities such as air tanker readiness and efficacy and liability issues. Other issues include the use of new technologies for wildfire detection and response, such as unmanned aircrafts. Another issue is the impact of the expanding wildland-urban interface (WUI), which is the area where structures (usually homes) are intermingled with or adjacent to vegetated wildlands (forests or rangelands).127 The proximity to vegetated landscapes puts these areas at a potential risk of experiencing wildfires and associated damage. Approximately 10% of all land within the lower 48 states is classified as WUI.128

CRS Products

CRS In Focus IF10244, Wildfire Statistics, by Katie Hoover.

CRS In Focus IF10732, Federal Assistance for Wildfire Response and Recovery, by Katie Hoover.

CRS Report R44966, Wildfire Suppression Spending: Background, Issues, and Legislation in the 115th Congress, by Katie Hoover and Bruce R. Lindsay.

CRS Report R45005, Wildfire Management Funding: Background, Issues, and FY2018 Appropriations, by Katie Hoover, Wildfire Management Funding: Background, Issues, and FY2018 Appropriations, by Katie Hoover.