National Park Service Deferred Maintenance: Frequently Asked Questions

This report addresses frequently asked questions about the National Park Service’s (NPS’s) backlog of deferred maintenance—maintenance that was not performed as scheduled or as needed and was put off to a future time. NPS’s deferred maintenance, also known as the maintenance backlog, was estimated for FY2018 (the most recent year available) at $11.920 billion. More than half of the NPS backlog is in transportation-related assets. Other federal land management agencies also have maintenance backlogs, but NPS’s is the largest and has drawn the most congressional attention.

During the past decade (FY2009-FY2018), NPS’s maintenance backlog grew by $1.751 billion in nominal dollars while declining by $0.368 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars. Many factors might contribute to growth or reduction in deferred maintenance, including the aging of NPS assets, the availability of funding for maintenance activities, acquisitions of new assets, agency management of the backlog, completion of individual projects, changes in construction and related costs, and changes in measurement and reporting methodologies. The backlog is distributed unevenly among states and territories, with California, the District of Columbia, and Virginia having the largest amounts of NPS deferred maintenance. The amounts also vary among individual park units. In terms of individual projects, transportation-related projects are among those with the highest deferred maintenance estimates.

Sources of funding to address NPS deferred maintenance include discretionary appropriations, allocations from the Department of Transportation, park entrance and concessions fees, donations, and others. It is not possible to determine the total amount of funding from these sources that NPS has allocated each year to address deferred maintenance, because NPS does not aggregate these amounts in its budget reporting.

NPS prioritizes its deferred maintenance projects based on the condition of assets and their importance to the parks’ mission, as well as other criteria related to financial sustainability, resource protection, visitor use, and health and safety. NPS has taken a number of steps over the decade to improve its asset management systems and strategies. Some observers, including the Government Accountability Office (GAO), have recommended further improvements. Both GAO and NPS itself have identified some challenges to managing the maintenance backlog, such as challenges related to disposing of unneeded assets.

Congress has addressed NPS deferred maintenance through oversight, appropriations, and other legislation. For example, the National Parks Centennial Act (P.L. 114-289) established two new funding sources available for NPS maintenance needs. Some Members of Congress and other stakeholders have proposed additional measures. Bills in the 116th Congress to increase NPS funding for deferred maintenance—including H.R. 1225, S. 500, and S. 3422—would draw from federal energy revenues currently going to the Treasury. Other proposed funding sources have included monies from the Land and Water Conservation Fund, income tax overpayments and contributions, new motorfuel taxes, coin and postage stamp sales, and new fees on visas and travel authorizations for foreign visitors (S. 2783), among others. Other bills focus on funding and prioritization for transportation-related deferred maintenance in particular (H.R. 5503).

The extent to which NPS deferred maintenance funding should be a priority, given other NPS and broader governmental needs, has been under debate. The additional funding sources in some bills have been opposed for various reasons. Some stakeholders have suggested that NPS’s maintenance backlog could be reduced without additional funding—for example, by improving the agency’s capital investment strategies or increasing the role of nonfederal partners in park management.

National Park Service Deferred Maintenance: Frequently Asked Questions

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- General Questions

- What Is Deferred Maintenance?

- How Big Is NPS's Maintenance Backlog?

- Has the Maintenance Backlog Been Increasing or Decreasing?

- What Factors Contribute to Growth or Reduction of the Backlog?

- How Does NPS's Backlog Compare with Those of Other Land Management Agencies?

- Which States Have the Largest NPS Maintenance Backlog?

- Which Park Units Have the Largest Maintenance Backlog?

- What Types of Projects Account for the Largest Share of NPS Deferred Maintenance?

- Funding for NPS Deferred Maintenance

- How Much Has NPS Spent in Recent Years to Address the Maintenance Backlog?

- What Are the Funding Sources for NPS to Address the Maintenance Backlog?

- Have Additional Types of Funding Been Proposed to Address the Backlog?

- Is Additional Deferred Maintenance Funding Needed?

- Management of the Maintenance Backlog

- How Does NPS Prioritize Its Deferred Maintenance Needs?

- What Challenges May Exist in Managing the Maintenance Backlog?

- Role of Congress

- How Has Congress Addressed NPS's Maintenance Backlog?

- What Laws Have Been Enacted in Recent Years to Address NPS Deferred Maintenance?

- What Legislation Has Been Proposed in the 116th Congress to Address NPS Deferred Maintenance?

Summary

This report addresses frequently asked questions about the National Park Service's (NPS's) backlog of deferred maintenance—maintenance that was not performed as scheduled or as needed and was put off to a future time. NPS's deferred maintenance, also known as the maintenance backlog, was estimated for FY2018 (the most recent year available) at $11.920 billion. More than half of the NPS backlog is in transportation-related assets. Other federal land management agencies also have maintenance backlogs, but NPS's is the largest and has drawn the most congressional attention.

During the past decade (FY2009-FY2018), NPS's maintenance backlog grew by $1.751 billion in nominal dollars while declining by $0.368 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars. Many factors might contribute to growth or reduction in deferred maintenance, including the aging of NPS assets, the availability of funding for maintenance activities, acquisitions of new assets, agency management of the backlog, completion of individual projects, changes in construction and related costs, and changes in measurement and reporting methodologies. The backlog is distributed unevenly among states and territories, with California, the District of Columbia, and Virginia having the largest amounts of NPS deferred maintenance. The amounts also vary among individual park units. In terms of individual projects, transportation-related projects are among those with the highest deferred maintenance estimates.

Sources of funding to address NPS deferred maintenance include discretionary appropriations, allocations from the Department of Transportation, park entrance and concessions fees, donations, and others. It is not possible to determine the total amount of funding from these sources that NPS has allocated each year to address deferred maintenance, because NPS does not aggregate these amounts in its budget reporting.

NPS prioritizes its deferred maintenance projects based on the condition of assets and their importance to the parks' mission, as well as other criteria related to financial sustainability, resource protection, visitor use, and health and safety. NPS has taken a number of steps over the decade to improve its asset management systems and strategies. Some observers, including the Government Accountability Office (GAO), have recommended further improvements. Both GAO and NPS itself have identified some challenges to managing the maintenance backlog, such as challenges related to disposing of unneeded assets.

Congress has addressed NPS deferred maintenance through oversight, appropriations, and other legislation. For example, the National Parks Centennial Act (P.L. 114-289) established two new funding sources available for NPS maintenance needs. Some Members of Congress and other stakeholders have proposed additional measures. Bills in the 116th Congress to increase NPS funding for deferred maintenance—including H.R. 1225, S. 500, and S. 3422—would draw from federal energy revenues currently going to the Treasury. Other proposed funding sources have included monies from the Land and Water Conservation Fund, income tax overpayments and contributions, new motorfuel taxes, coin and postage stamp sales, and new fees on visas and travel authorizations for foreign visitors (S. 2783), among others. Other bills focus on funding and prioritization for transportation-related deferred maintenance in particular (H.R. 5503).

The extent to which NPS deferred maintenance funding should be a priority, given other NPS and broader governmental needs, has been under debate. The additional funding sources in some bills have been opposed for various reasons. Some stakeholders have suggested that NPS's maintenance backlog could be reduced without additional funding—for example, by improving the agency's capital investment strategies or increasing the role of nonfederal partners in park management.

The National Park Service's (NPS's) backlog of deferred maintenance (DM)—maintenance that was not performed as scheduled or as needed—is an issue of ongoing interest to Congress. The agency estimated its DM needs for FY2018 (the most recent year available) at $11.920 billion. Although other federal land management agencies also have DM backlogs, NPS's backlog is the largest.1 Because unmet maintenance needs may damage park resources, adversely affect visitors' enjoyment of the parks, and jeopardize safety, NPS DM has been a topic of concern for Congress and for nonfederal stakeholders. Potential issues for Congress include, among others, how to weigh NPS maintenance needs against other financial demands within and outside of the agency, how to ensure that NPS is managing its maintenance activities efficiently and successfully, and how to balance the maintenance of existing parks with the establishment of new park units. This report addresses frequently asked questions about NPS DM. The discussion is organized under the headings of general questions, funding-related questions, management-related questions, and questions on Congress's role in addressing the backlog.

General Questions

What Is Deferred Maintenance?

The Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board defines deferred maintenance and repairs (DM&R) as "maintenance and repairs that were not performed when they should have been or were scheduled to be and which are put off or delayed for a future period."2 NPS uses similar language to define deferred maintenance.3 Although NPS uses the term DM rather than DM&R, its estimates also include repair needs. Following NPS's usage, this report uses the term DM to refer to NPS's deferred maintenance and repair needs. Members of Congress and other stakeholders also often refer to DM as the maintenance backlog.4

As suggested by the above definition, DM does not include all maintenance, only maintenance that was not accomplished when scheduled or needed and was put off to a future time. Another type of maintenance is cyclic maintenance—that is, maintenance performed at regular intervals to prevent asset deterioration, such as to replace a roof or upgrade an electrical system at a scheduled or needed time.5 Although NPS considers cyclic maintenance separately from DM for budgeting purposes, NPS has emphasized the importance of cyclic maintenance for controlling DM costs. Cyclic maintenance, the agency has stated, "is a central element of NPS efforts to curtail the continued growth of deferred maintenance and promote asset lifecycle management."6 NPS also performs routine, day-to-day maintenance as part of its facility operations activities. Such activities include, for example, mowing and weeding of landscapes and trails, conducting custodial and janitorial functions, and removing litter.7

How Big Is NPS's Maintenance Backlog?

NPS estimated its total DM for FY2018 at $11.920 billion.8 This amount is split between transportation-related DM in the "Paved Roads and Structures" category and mostly non-transportation-related DM for all other assets (see Table 1). The Paved Roads and Structures category includes paved roadways, bridges, tunnels, and paved parking areas. The other assets are in eight categories: Buildings, Housing, Campgrounds, Trails, Wastewater Systems, Water Systems, Unpaved Roads, and All Other.9

|

Paved Roads and Structures |

$6.154 |

|

All Other Facilities |

$5.766 |

|

Buildings |

$2.034 |

|

Housing |

$0.187 |

|

Campgrounds |

$0.079 |

|

Trails |

$0.461 |

|

Wastewater Systems |

$0.290 |

|

Water Systems |

$0.426 |

|

Unpaved Roads |

$0.185 |

|

All Other |

$2.103 |

|

Total |

$11.920 |

Source: NPS, Servicewide NPS Asset Inventory Summary, September 30, 2018, at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/infrastructure/upload/NPS-Asset-Inventory-Summary-FY18-Servicewide_2018.pdf.

Note: Totals may not sum precisely due to rounding.

Has the Maintenance Backlog Been Increasing or Decreasing?

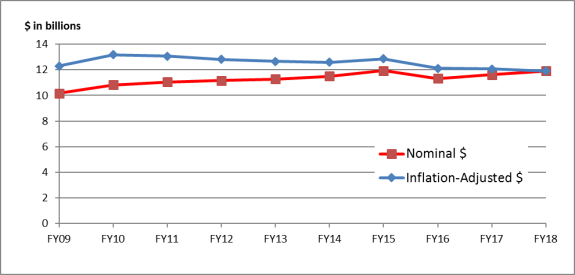

NPS's estimated maintenance backlog has increased over the past decade (FY2009-FY2018) in nominal dollars but decreased when adjusted for inflation. Figure 1 and Table 2 show a growth in NPS DM of $1.751 billion in nominal dollars and a decline of $0.368 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars.

|

Figure 1. NPS Maintenance Backlog Estimates, FY2009-FY2018 ($ in billions) |

|

|

Nominal $ |

Inflation-Adjusted $ |

|

|

FY2009 |

10.169 |

12.288 |

|

FY2010 |

10.828 |

13.176 |

|

FY2011 |

11.044 |

13.067 |

|

FY2012 |

11.158 |

12.811 |

|

FY2013 |

11.269 |

12.664 |

|

FY2014 |

11.493 |

12.599 |

|

FY2015 |

11.927 |

12.865 |

|

FY2016 |

11.332 |

12.110 |

|

FY2017 |

11.607 |

12.079 |

|

FY2018 |

11.920 |

11.920 |

|

Change, FY2009-FY2018 |

+1.751 |

-0.368 |

Sources for Figure 1 and Table 2: Nominal-dollar estimates for FY2009-FY2013 were calculated by CRS based on deferred maintenance ranges provided to CRS by the Department of the Interior (DOI) Budget Office. Nominal-dollar estimates for FY2014-FY2018 are from NPS, "NPS Deferred Maintenance Reports," at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/plandesignconstruct/defermain.htm. See page 5 for additional information on sources. Adjustments for inflation (shown in 2018 dollars) use the Bureau of Economic Analysis, Table 3.9.4, "Price Indexes for Government Consumption Expenditures and Gross Investment," for nondefense structures, annual indexes, at https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm.

What Factors Contribute to Growth or Reduction of the Backlog?

Multiple factors may contribute to growth or reduction in the NPS maintenance backlog. One key driver of growth in NPS maintenance needs has been the increasing age of agency infrastructure. Many agency assets—such as visitor centers, roads, utility systems, and other assets—were constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s or as part of the agency's Mission 66 infrastructure initiative in the 1950s and 1960s.10 As these structures have reached or exceeded the end of their anticipated life spans, unfunded costs of repair or replacement have contributed to the DM backlog. Further, agency officials point out, as time goes by and needed repairs are not made, the rate at which such assets deteriorate is accelerated and can result in "a spiraling burden."11

Another key factor is the amount of funding available to the agency to address DM. The sources and amounts of NPS funding for DM are discussed in greater detail below, in the section on "Funding for NPS Deferred Maintenance." NPS does not aggregate the amounts it receives and uses each year to address deferred maintenance, but agency officials have stated repeatedly that available funding has been inadequate to meet DM needs.12 In recent years, Congress has increased NPS appropriations to address DM.13 NPS has stated that these funding increases, although helping the agency with some of its most urgent needs, have been insufficient to address the total problem.14 Some observers have advocated for further increases in agency funding as a way to address DM; some others have recommended reorienting existing funding to prioritize maintenance over other purposes.

Another subject of attention is the extent to which acquisition of new properties—for example, through the creation of new parks or the expansion of existing parks—may add to the maintenance burden. To the extent that newly acquired lands contain assets with maintenance and repair needs that are not met, these additional assets would increase NPS DM. The agency has stated in the past that new additions with infrastructure in need of maintenance and repair have been relatively rare, and most acquired lands have been unimproved or have contained assets in good condition.15 NPS also has stated that some acquisitions of "inholdings" within existing parks have facilitated maintenance and repair efforts by providing needed access for maintenance activities.16 Others have contended that even if new acquisitions do not immediately contribute to the backlog, they likely will do so over time, and that further expansion of the National Park System is inadvisable until the maintenance needs of existing properties have been addressed. For example, the Administration's FY2021 budget proposes to eliminate funding for NPS federal land acquisition projects in order to "focus … available funds on the protection and management of existing lands and assets."17

Some observers also have expressed concerns that growth in NPS DM may be at least partially due to inefficiencies in the agency's asset management strategies and/or the implementation of these strategies. The section of this report on "Management of the Maintenance Backlog" gives further details on NPS's management of its DM backlog. NPS has taken a number of steps over the decade to improve its asset management systems and strategies. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has recommended further improvements.18

Still another issue is that the methods used by NPS and the Department of the Interior (DOI) to estimate DM have varied over time and for different types of maintenance reporting.19 What portion of the overall change in NPS DM over the decade may be attributable to changes in methodology or data completeness, rather than to other factors, is unclear.

From year to year, the completion of individual projects, changes in construction and repair costs, and similar factors play a role in the growth or reduction of NPS DM. The DM amounts reported by NPS for each fiscal year represent a snapshot of the backlog on the applicable date. The amount of DM changes frequently as NPS managers and staff complete or cancel maintenance work, recalculate costs, and record new maintenance and repair needs. For example, the change in the DM amount between FY2017 ($11.607 billion) and FY2018 ($11.920 billion) included work order completions, cancellations, and cost changes that reduced DM by $1.313 billion, along with new work orders and cost changes that added $1.626 billion to the backlog.20

How Does NPS's Backlog Compare with Those of Other Land Management Agencies?

Although all four major federal land management agencies—NPS, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and the Forest Service (FS)—have DM backlogs, NPS's backlog is the largest. For FY2018, NPS reported DM of $11.920 billion, whereas FS reported DM of less than half that amount ($5.217 billion), and FWS and BLM reported $1.301 billion and $0.955 billion, respectively. DM for the four agencies is discussed further in CRS Report R43997, Deferred Maintenance of Federal Land Management Agencies: FY2009-FY2018 Estimates and Issues.

Which States Have the Largest NPS Maintenance Backlog?

NPS reports DM by state and territory in its report titled NPS Deferred Maintenance by State and Park.21 The 20 states (including the District of Columbia) with the highest NPS DM estimates are shown in Table 3.

|

State |

NPS Deferred Maintenance Estimate |

|

California |

1.890 |

|

Washington, DC |

1.269 |

|

Virginia |

1.137 |

|

New York |

0.871 |

|

Wyoming |

0.771 |

|

Arizona |

0.507 |

|

North Carolina |

0.459 |

|

Washington |

0.428 |

|

Mississippi |

0.326 |

|

Pennsylvania |

0.314 |

|

Maryland |

0.293 |

|

Tennessee |

0.291 |

|

Nevada |

0.252 |

|

Colorado |

0.247 |

|

Massachusetts |

0.244 |

|

Florida |

0.240 |

|

New Jersey |

0.223 |

|

Utah |

0.219 |

|

Montana |

0.187 |

|

Hawaii |

0.165 |

Source: NPS, NPS Deferred Maintenance by State and Park, September 30, 2018, at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/infrastructure/upload/NPS-Deferred-Maintenance-FY18-State_and_Park_2018.pdf.

The states with the highest DM are not necessarily those with the most park acreage. For example, Alaska contains almost two-thirds of the total acreage in the National Park System but accounts for less than 1% of the agency's DM backlog. Instead, the amount, type, and condition of infrastructure in a state's national park units are the primary determinants of DM for each state. For example, transportation assets are a major component of NPS DM, and states with NPS-administered parkways—the George Washington Memorial Parkway (mainly in Virginia and Washington, DC), the Natchez Trace Parkway (mainly in Mississippi and Tennessee), the Blue Ridge Parkway (North Carolina and Virginia), and the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Memorial Parkway (Wyoming)—are all among the 20 states with the highest DM.22

Which Park Units Have the Largest Maintenance Backlog?

Table 4 shows the 20 individual park units with the highest maintenance backlogs.

|

Park Unit |

State |

NPS Deferred Maintenance Estimate |

|

Gateway National Recreation Area |

NJ, NY |

0.774a |

|

George Washington Memorial Parkway |

DC, MD, VA |

0.717b |

|

National Mall and Memorial Parks |

DC |

0.655 |

|

Yosemite National Park |

CA |

0.646 |

|

Yellowstone National Park |

ID, MT, WY |

0.586c |

|

Blue Ridge Parkway |

NC, VA |

0.508d |

|

Colonial National Historical Park |

VA |

0.434 |

|

Natchez Trace Parkway |

AL, MS, TN |

0.369e |

|

Golden Gate National Recreation Area |

CA |

0.324 |

|

Grand Canyon National Park |

AZ |

0.314 |

|

Lake Mead National Recreation Area |

AZ, NV |

0.237f |

|

Great Smoky Mountains National Park |

NC, TN |

0.236g |

|

National Capital Parks–East |

DC, MD |

0.195h |

|

Mount Rainier National Park |

WA |

0.186 |

|

Grand Teton National Park |

WY |

0.181 |

|

Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Park |

CA |

0.170 |

|

Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area |

NJ, PA |

0.147i |

|

San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park |

CA |

0.146 |

|

Glacier National Park |

MT |

0.131 |

|

Death Valley National Park |

CA, NV |

0.129j |

Source: NPS, NPS Deferred Maintenance by State and Park, September 30, 2018, at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/infrastructure/upload/NPS-Deferred-Maintenance-FY18-State_and_Park_2018.pdf.

a. DM for Gateway National Recreation Area consists of $123.3 million in New Jersey and $651.1 million in New York.

b. DM for the George Washington Memorial Parkway consists of $393.9 million in the District of Columbia, $29.8 million in Maryland, and $293.5 million in Virginia.

c. DM for Yellowstone National Park consists of $0.1 million in Idaho, $22.1 million in Montana, and $563.4 million in Wyoming.

d. DM for the Blue Ridge Parkway consists of $295.4 million in North Carolina and $212.7 million in Virginia.

e. DM for the Natchez Trace Parkway consists of $9.0 million in Alabama, $290.0 million in Mississippi, and $70.0 million in Tennessee.

f. DM for Lake Mead National Recreation Area is attributed entirely to Nevada, although a portion of the unit is in Arizona.

g. DM for Great Smoky Mountains National Park consists of $73.1 million in North Carolina and $162.8 million in Tennessee.

h. DM for National Capital Parks–East consists of $76.2 million in Washington, DC, and $119.0 million in Maryland.

i. DM for Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area consists of $84.3 million in New Jersey and $63.2 million in Pennsylvania.

j. DM for Death Valley National Park is attributed entirely to California, although a portion of the unit is in Nevada.

Various factors may contribute to the relatively high DM estimates for these park units as compared to others. For example, many of them are older units whose infrastructure was largely built in the mid-20th century. Some sites, such as Gateway National Recreation Area and Golden Gate National Recreation Area, are located in or near urban areas and contain more buildings, roads, and other built assets than some more remotely located parks. Three of the units with the highest estimated DM are national parkways, consistent with the high proportion of NPS's overall DM backlog that is related to road needs.23

What Types of Projects Account for the Largest Share of NPS Deferred Maintenance?

Transportation-related projects are among those with the highest DM estimates. As shown in Table 1, more than half of NPS's DM backlog is attributed to transportation assets. The agency reported that two-fifths of paved roads in the National Park System were rated in "fair" or "poor" condition as of the end of FY2018.24

In particular, NPS reports a number of transportation "mega-projects" that require "a much larger amount of funding than is available on an annual basis."25 These include projects such as rehabilitation of the Arlington Memorial Bridge (crossing the Potomac River between the District of Columbia and northern Virginia), with repair work estimated at $227 million;26 and modifications to the Tamiami Trail in Everglades National Park, with an estimated cost of $240 million.27 Other examples involve road, trail, or bridge work on the Natchez Trace Parkway, at Colonial National Historical Park, and at Great Smoky Mountains National Park.28 In some cases, NPS has worked with states to seek project-specific grants, outside of standard NPS funding sources, for these high-cost transportation projects (see "What Are the Funding Sources for NPS to Address the Maintenance Backlog?").

Projects related to other types of park infrastructure also may have high DM estimates. For example, DM needs for the Trans-Canyon Water Pipeline in Grand Canyon National Park have been estimated at more than $150 million, and DM needs for the infrastructure surrounding East Potomac Park (part of the National Mall and Memorial Parks in Washington, DC), including a deteriorating seawall, have been estimated to exceed $500 million.29

Funding for NPS Deferred Maintenance

How Much Has NPS Spent in Recent Years to Address the Maintenance Backlog?

It is not possible to determine the total amount of funding allocated each year to address NPS's DM backlog, because NPS does not aggregate these amounts in its budget reporting. Funding to address DM comes from a variety of NPS budget sources, and each of these budget sources also funds activities other than DM. NPS does not report how much of each funding stream was used for DM in any given year.30 Some estimates have suggested that annual funding of roughly $800 million per year would be required simply to maintain NPS assets at existing conditions, without addressing the DM backlog.31

What Are the Funding Sources for NPS to Address the Maintenance Backlog?

NPS has used discretionary appropriations, allocations from the Department of Transportation, park entrance and recreation fees, donations, and other funding sources to address the maintenance backlog. Most of the funding for DM comes from discretionary appropriations, primarily under two budget activities, titled "Repair and Rehabilitation" and "Line-Item Construction."

- The Repair and Rehabilitation (R&R) budget subactivity, within the NPS's Operation of the National Park System (ONPS) budget account,32 focuses on large-scale, nonrecurring repair needs in cases where scheduled maintenance is no longer sufficient to improve the condition of the facility.33 R&R funds are used for projects with projected costs of less than $2 million each. These projects may include both DM and other types of maintenance.34 FY2020 appropriations for the R&R subactivity in P.L. 116-94 were $136.0 million.

- The Line-Item Construction budget activity, within the NPS's Construction account, provides funding for major maintenance, repair, and replacement of high-priority NPS assets.35 This funding is used for projects expected to cost $2 million or more. NPS prioritizes projects based on "monetary and nonmonetary benefits, return on investment, and overall risk."36 As with the R&R budget subactivity, the projects may include both DM and other types of maintenance.37 FY2020 appropriations in P.L. 116-94 for Line-Item Construction were $283.0 million.

- Portions of other NPS discretionary budget activities and accounts also are used for DM. These include various budget activities within the ONPS and Construction accounts, as well as NPS's Centennial Challenge account. The Centennial Challenge account provides federal funds to match outside donations for "signature" NPS parks and programs. The funding is used to enhance visitor services, reduce DM, and improve natural and cultural resource protection.38 The FY2020 appropriation for the Centennial Challenge program in P.L. 116-94 was $15 million.

Beyond NPS discretionary appropriations, a number of other, nondiscretionary agency revenue streams also are used partially or mainly to address DM. Where applicable, the discussion below gives estimates of revenues from these sources for FY2020, as provided in NPS's FY2021 budget justification. These estimates would not reflect factors arising since preparation of the budget justification, such as the closure of many national park units during the COVID-19 outbreak.39

- NPS receives an annual allocation from the Highway Trust Fund to address transportation needs, including transportation-related DM.40 Funds are provided to NPS (and other federal land management agencies) by the Federal Highway Administration, primarily under the Federal Lands Transportation Program. The program was most recently reauthorized by the Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act (FAST Act; P.L. 114-94). In recent years, these allocations have accounted for more than half of NPS's transportation-related maintenance spending.41 For FY2020, NPS's allocation from the Federal Lands Transportation Program is $300.0 million.42 Through related federal highway programs, NPS could potentially receive additional funding.43 For some of its "mega-projects," NPS has worked with states to apply for transportation grants not otherwise available to the agency.44

- Park entrance and recreation fees collected under the Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act (16 U.S.C. §§6801-6814) may be used for DM, among other purposes. The fees are available for use without further appropriation, and most are retained at the collecting parks.45 Fee collections may be used for a variety of purposes benefiting visitors, including facility maintenance and repair, interpretation and visitor services, law enforcement, and others. In its FY2021 budget justification, NPS estimates entrance and recreation fee collections of $344.4 million for FY2020.46 Under NPS policy, parks must obligate at least 55% of recreation fee allocations to DM projects.47

- NPS collects concessions franchise fees from park concessioners who provide services such as lodging and dining at park units. The fees, collected under the National Park Service Concessions Management Improvement Act of 1998 (54 U.S.C. §§101911 et seq.), are available for use without further appropriation and are mainly retained at the collecting parks.48 They may be used to reduce DM, among other purposes, with priority given to concessions-related DM.49 In its FY2021 budget justification, NPS estimates concessions franchise fee collections of $135.8 million for FY2020.50

- The National Park Service Centennial Act (P.L. 114-289) established the NPS Centennial Challenge Fund. In addition to discretionary appropriations (discussed above), the fund is authorized to receive, as offsetting collections, certain amounts from the sales of entrance passes to seniors.51 NPS estimates that the senior pass sales will provide an additional $4.0 million for the account in FY2020, on top of discretionary appropriations.52 Federal funds must be matched by nonfederal donations on at least a 50:50 basis. The funding may be used for a variety of projects but must prioritize DM, improvements to visitor services facilities, and trail maintenance.53 The Centennial Act also established the NPS Second Century Endowment and directed that the endowment receive, as offsetting collections, revenues from senior pass sales totaling $10 million annually.54 The endowment also is authorized to receive gifts, devises, and bequests from donors. The funds may be used for projects approved by the Secretary of the Interior that further the purposes of NPS, including projects on the maintenance backlog. More broadly, other types of donations to NPS may be used for projects that reduce DM, among a variety of other purposes.55 NPS estimated that, through all of these programs combined, the agency would receive donations of $52.0 million in FY2020 (in addition to the revenues generated from the sales of the senior passes).56

- Other NPS mandatory appropriations also have been partially used for DM. These include monies collected under the Park Building Lease and Maintenance Fund, transportation fees collected under the Transportation Systems Fund, and rents and payroll deductions for the use and occupancy of government quarters, among others. NPS estimated varying amounts for these mandatory appropriations for FY2020.

Have Additional Types of Funding Been Proposed to Address the Backlog?

Some Members of Congress and other stakeholders have proposed sources of additional funding to address NPS's DM needs. Stakeholders have advocated for increases in both discretionary and mandatory appropriations for this purpose. Some have contended that NPS maintenance projects, which often require multiyear investments, are hampered by the agency's heavy reliance on discretionary appropriations, which are uncertain from year to year. These stakeholders seek greater funding certainty through mandatory appropriations.57 Others contend that discretionary appropriations provide an important level of congressional oversight over each year's funding that would not be present if funds were provided outside that annual process.58

Legislative proposals in the 116th Congress are discussed in the "Role of Congress" section, below. A number of these bills would address deferred maintenance through a mandatory fund drawn from federal energy development revenues.59 Supporters of this type of funding have expressed the principles that monies derived from energy development on federal lands should be used in part to conserve and maintain federal lands, and that NPS maintenance is a particular priority given the park system's highly valued natural and cultural resources, its contributions to the outdoor recreation economy, and its substantial DM backlog. Opponents of proposals to use federal energy revenues for NPS deferred maintenance have debated the extent to which these revenues should be prioritized for NPS DM versus other potential uses, such as for other federal programs, sharing with states, or contributing to the General Treasury. Some also have expressed concerns that an approach based on energy revenues could incentivize federal fossil fuel leasing as a means of financing NPS maintenance, with associated climate impacts that could have negative consequences for parks over time.60

Outside of proposals to use federal energy revenues for NPS DM, stakeholders also have proposed to increase DM funding by other means, such as through visa fees paid by foreign visitors to the United States, monies from the Land and Water Conservation Fund, income tax overpayments and contributions, motorfuel taxes, DOI land sales, or revenues from coin and postage stamp sales.61 Other suggestions have involved ways to increase the revenues that NPS itself collects, such as by raising park entrance fees, offering new types of products or services to visitors for a fee, or introducing tolling on park highways that are used as major commuter routes (especially in the region around Washington, DC).62 Some have opposed such proposals as diverting federal funds from other valued uses or imposing unnecessary fees on the public.

Is Additional Deferred Maintenance Funding Needed?

The extent to which NPS deferred maintenance funding should be a priority, given other NPS and broader governmental needs, has been under debate. As discussed, the funding sources in some proposals have been opposed for various reasons. In an environment of constrained federal budgets, measures to increase financial support for NPS DM generally would reduce funds available to other programs or to the General Treasury or would require imposition of new fees that some may view as burdensome.

Some proposals have focused on ways NPS could reduce DM without the application of additional funds. Some have suggested that this could be accomplished by improving the agency's capital investment strategies, increasing the role of nonfederal partners in park management, disposing of unneeded structures in poor repair, or transferring some NPS assets (such as commuter roads) out of federal ownership.63

Management of the Maintenance Backlog

How Does NPS Prioritize Its Deferred Maintenance Needs?

NPS uses standardized inputs and measures, captured in electronic management systems, to prioritize its DM projects.64 Two primary factors in the priority assessments are the condition of an asset and its importance to the NPS missions of resource preservation and visitor use.65 To determine the condition of assets, agency staff at each park perform condition assessments according to specified standards.66 Park managers separately assign ratings of an asset's importance, using DOI-wide "asset priority" standards that take into account an asset's contribution to natural and cultural resource preservation, visitor use, and park operations, as well as the availability of other comparable assets that could fulfill similar functional requirements.67 These ratings of condition and asset priority are captured in the work orders that park managers generate for maintenance and repairs, using a Facility Management Software System.

Park managers also classify assets in broad optimizer bands indicating "the level of maintenance that each asset should receive."68 Of the five optimizer band ratings, the highest level (band 1) is defined as "critical to the operations and mission of the park or having high visitor use; require the highest base funding."69 Subsequent levels are labeled high, medium, low, and lowest, with the lowest level (band 5) defined as "assets not required for the operations and mission of the park, such as inactive assets, or those fully maintained by partners. These assets are often in poor condition. Many are good candidates for disposal."70 For FY2018, of the total $11.920 billion in deferred maintenance, NPS categorized $5.814 billion in optimizer band 1 (highest level), $3.298 billion in band 2 (high), $1.942 billion in band 3 (medium), $0.551 billion in band 4 (low), and $0.316 billion in band 5 (lowest).71

NPS regional offices prioritize maintenance projects within their regions, and national-level officials assign service-wide priorities in the five-year project plans submitted as part of annual NPS budget justifications. NPS projects may include work classified as deferred maintenance along with other related infrastructure work that might be classified as other types of maintenance.72

What Challenges May Exist in Managing the Maintenance Backlog?

In addition to the funding challenges discussed earlier, NPS faces other issues in managing the maintenance backlog. In 2016, GAO reported on NPS management of maintenance activities, and identified both successes and challenges.73 Among successes in NPS asset management, GAO reported that the agency's assessment tools were consistent with federally prescribed standards and that it was working with partners and volunteers to address maintenance needs.74 In terms of challenges, GAO reported that competing duties often made it difficult for park staff to perform facility condition assessments in a timely manner, that the remote location of some assets contributed to this difficulty, that the agency's focus on high-priority assets might lead to continued deterioration of lower-priority assets, and that NPS lacked a process for verifying that its Capital Investment Strategy was producing the intended outcomes.75

A particular challenge identified by NPS relates to the disposal of unneeded assets to reduce the agency's maintenance burden.76 Such "excess" facilities, NPS has stated, can create health and safety hazards in addition to adding to the DM backlog.77 However, NPS has at times stated that the cost of demolishing or disposing of these assets precludes the use of this option.78 NPS has requested and received funding under the Line-Item Construction budget activity for demolition and disposal of unneeded assets. NPS received appropriations of $5.0 million for this activity in FY2020. GAO identified that legal requirements—such as the requirement in the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act (P.L. 100-77, as amended) that federal buildings slated for disposal must be assessed for their potential to provide homeless assistance before being disposed of by other means—create additional obstacles for NPS disposal of unneeded properties.79 NPS wrote that the McKinney-Vento assessment process can take 8-12 months and "has been onerous and has not resulted [in] a benefit for either the NPS or any qualified organization."80 NPS stated that as of July 2019, it had processed more than 400 "excess buildings" under requirements of the act, and none had been found suitable for homeless use.81

Role of Congress

How Has Congress Addressed NPS's Maintenance Backlog?

Congress has addressed NPS's maintenance backlog through oversight, appropriations, and other legislation. For example, the natural resources committees in the House and Senate have held oversight hearings to investigate options for addressing the DM needs of NPS and other federal land management agencies.82 Congress has provided both discretionary and mandatory appropriations to address NPS DM, as discussed in the section on "Funding for NPS Deferred Maintenance."83 Additionally, Congress has considered and enacted other statutory changes to address the backlog, as discussed below.

What Laws Have Been Enacted in Recent Years to Address NPS Deferred Maintenance?

In addition to annual appropriations acts and surface transportation legislation with NPS allocations, the National Parks Centennial Act (P.L. 114-289), enacted in December 2016, addressed the maintenance backlog in multiple ways. The act created two funds that may be used to reduce DM—the National Park Centennial Challenge Fund and the Second Century Endowment for the National Park Service.84 Both funds receive federal monies from the sale of senior recreation passes, as well as donations. DM projects are a prioritized use of the Centennial Challenge Fund and are among the potential uses of endowment funds.85 In addition, the act authorized appropriations of $5.0 million annually for FY2017-FY2023 for the National Park Foundation to match nonfederal contributions. Contributions to the foundation are used for a variety of NPS projects and programs, including projects on the maintenance backlog. The law also made changes to extend the eligible ages for participants in the Public Land Corps and increase the authorization of appropriations for the Volunteers in the Parks program.86 Participants in these programs perform a variety of duties that help address DM, among other activities.87 The John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act (P.L. 116-9), enacted in March 2019, made additional changes to extend eligibility for the Public Land Corps.88

The Helium Stewardship Act of 2013 provided mandatory appropriations totaling $50 million over two fiscal years (FY2018 and FY2019) to pay the federal share of NPS challenge cost-share projects aimed at addressing DM and correcting deficiencies in NPS infrastructure.89 The projects require at least a 50% match from a nonfederal funding source (including in-kind contributions). The act provided $20 million of the funding in FY2018 and $30 million in FY2019. After sequestration, NPS reported $18.7 million as the FY2018 mandatory appropriation and $28.1 million as the FY2019 appropriation.

What Legislation Has Been Proposed in the 116th Congress to Address NPS Deferred Maintenance?

Bills in the 116th Congress related to NPS deferred maintenance include the following. For further discussion of some of these proposals, see CRS In Focus IF10987, Legislative Proposals to Address National Park Service Deferred Maintenance, by Laura B. Comay.

- S. 3422, the Great American Outdoors Act, was introduced on March 9, 2020, and placed on the Senate calendar on March 10, 2020. The bill would establish a National Parks and Public Land Legacy Restoration Fund, which would receive annual deposits over five years of 50% of all federal energy development revenues (from both conventional and renewable sources) credited, covered, or deposited as miscellaneous receipts under federal law, up to a cap of $1.9 billion annually. Deposits to the fund would be available as mandatory spending to address the deferred maintenance backlogs of several federal agencies under specified terms. NPS would receive 70% of available funds.90

- S. 500, the Restore Our Parks Act, was reported by the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources on February 25, 2020. The bill would establish a National Park Service Legacy Restoration Fund, with a similar funding mechanism to that of S. 3422 but with a cap of $1.3 billion annually over five years. The funding would go entirely to NPS as mandatory appropriations to address "priority deferred maintenance projects" under specified terms.

- H.R. 1225, the Restore Our Parks and Public Lands Act, was reported by the House Committee on Natural Resources on October 22, 2019. This bill would establish a National Park Service and Public Lands Legacy Restoration Fund, also with a similar funding mechanism to that of S. 3422 but with a cap of $1.3 billion annually over five years. The funding would be available as mandatory appropriations. NPS would receive 80% of available amounts, to be used for "priority deferred maintenance projects" under specified terms. FWS would receive 10%, and BLM and the Bureau of Indian Education would receive 5% each for their deferred maintenance.

- S. 2783 was introduced on November 5, 2019. It would establish a National Park Service Legacy Restoration Fund supported by a $5 increase in entrance fees across the National Park System, a fee increase to international visitors for temporary visas, and a fee increase for use of the Electronic System for Travel Authorization available to countries in the U.S. Visa Waiver Program.91 The funds would be deposited annually for 10 years and would be available as mandatory spending to NPS "to carry out repair, restoration, or rehabilitation projects" under specified terms.

- H.R. 5503, the Commuter Parkway Safety and Reliability Act, was introduced on December 20, 2019. It would require NPS to prioritize its allocation from the Federal Lands Transportation Program for use on "high-commuter corridors," defined in the bill as NPS roads with average annual daily traffic of at least 20,000 vehicles. It also would establish a process for the NPS Director to request that states transfer portions of their federal surface transportation funding to NPS or the Federal Highway Administration to address NPS road maintenance needs that exceed the agency's available funding.

In addition to the proposals in 116th Congress bills, stakeholders within and outside of Congress have proposed other ideas for addressing NPS deferred maintenance. Additional proposals are discussed under the questions "Have Additional Types of Funding Been Proposed to Address the Backlog?" and "Is Additional Deferred Maintenance Funding Needed?"

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

For more information on the maintenance backlogs of the four major federal land management agencies—the Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, and Fish and Wildlife Service in the Department of the Interior, and the Forest Service in the Department of Agriculture—see CRS Report R43997, Deferred Maintenance of Federal Land Management Agencies: FY2009-FY2018 Estimates and Issues, by Carol Hardy Vincent. |

| 2. |

Financial Accounting Standards Advisory Board (FASAB), Statement of Federal Financial Accounting Standards 42: Deferred Maintenance and Repairs: Amending Statements of Federal Financial Accounting Standards 6, 14, 29 and 32, April 25, 2012, p. 5, at http://www.fasab.gov/pdffiles/handbook_sffas_42.pdf. The FASAB is a federal advisory committee that develops accounting standards for U.S. government agencies. For more information, see CRS Report R42975, Federal Financial Reporting: An Overview, coordinated by Garrett Hatch. |

| 3. |

National Park Service (NPS), "Planning, Design, and Construction Management: NPS Deferred Maintenance Reports," at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/plandesignconstruct/defermain.htm. Specifically, according to NPS, "DM is maintenance and repairs of assets that was not performed when it should have been and is delayed for a future period." |

| 4. |

This report uses the terms deferred maintenance (DM) and maintenance backlog interchangeably. |

| 5. |

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) defines cyclic maintenance as "significant, regularly occurring maintenance projects designed to prevent assets from degrading to the point that they need to be repaired." GAO, National Park Service: Process Exists for Prioritizing Asset Maintenance Decisions, but Evaluation Could Improve Efforts, GAO-17-136, p. 11, at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-17-136, hereinafter referred to as "2017 GAO Report." NPS states that its Cyclic Maintenance Program "provides funding for prioritized projects that focus on addressing preventive, planned maintenance activities." NPS, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2021, p. ONPS-66, at https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/uploads/fy2021-nps-budget-justification.pdf, hereinafter referred to as "NPS FY2021 budget justification." |

| 6. |

NPS FY2021 budget justification, p. ONPS-66. |

| 7. |

NPS FY2021 budget justification, p. ONPS-59. |

| 8. |

NPS, "What Is Deferred Maintenance?," at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/plandesignconstruct/defermain.htm. This estimate is developed by the NPS Park Facility Management Division. |

| 9. |

NPS, "NPS Asset Inventory Summary," at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/infrastructure/upload/NPS-Asset-Inventory-Summary-FY18-Servicewide_2018.pdf. The "Unpaved Roads" category includes unpaved roadways and unpaved parking areas. The "All Other" category includes utility systems, dams, constructed waterways, marinas, aviation systems, railroads, ships, monuments, fortifications, towers, interpretive media, and amphitheaters. |

| 10. |

The Civilian Conservation Corps was a 1930s program established by President Franklin Roosevelt to create jobs and enhance the nation's natural resources. For more information, see John C. Paige, The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933-1942: An Administrative History, 1985, at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/ccc/. Under the Mission 66 program, Congress appropriated roughly $1 billion over a decade for NPS infrastructure improvements, leading up to NPS's 50th anniversary in 1966. For more information, see Sarah Allaback, Mission 66 Visitor Centers: The History of a Building Type, 2000, at https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/allaback/; and Ethan Carr, Mission 66: Modernism and the National Park Dilemma (Univ. of Massachusetts Press, 2007). |

| 11. |

NPS Park Facility Management Division, "Deferred Maintenance Backlog," September 24, 2014, at https://www.nps.gov/transportation/pdfs/DeferredMaintenancePaper.pdf. Also see NPS statements in House Committee on Natural Resources, Legislative Hearing: H.R. 5210, "National Park Restoration Act"; and H.R. 2584, "National Park Service Legacy Act of 2017," H.Hrg. 115-42, March 20, 2018, p. 14, at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-115hhrg29422/pdf/CHRG-115hhrg29422.pdf; hereinafter cited as H.Hrg. 115-42. NPS stated: "The longer that an asset's deferred maintenance goes unaddressed, the faster that asset will deteriorate," and provided a detailed example. |

| 12. |

See, for example, House Committee on Natural Resources, Exploring Innovative Solutions to Reduce the Department of the Interior's Maintenance Backlog, H.Hrg. 115-39, 115th Cong. 2nd sess., March 6, 2018, p. 34, at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-115hhrg28851/pdf/CHRG-115hhrg28851.pdf, hereinafter cited as H.Hrg. 115-39; House Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies, National Park Service Budget Oversight Hearing, 114th Cong., 2nd sess., March 16, 2016, pp. 123-124, at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-114hhrg20144/pdf/CHRG-114hhrg20144.pdf; and Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, Supplemental Funding Options to Support the National Park Service, S.Hrg. 113-82, 113th Cong., 1st sess., July 25, 2013, pp. 20-21, at https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-113shrg82796/pdf/CHRG-113shrg82796.pdf, hereinafter cited as S.Hrg. 113-82. |

| 13. |

For information on NPS appropriations in the past decade, see CRS Report R42757, National Park Service Appropriations: Ten-Year Trends, by Laura B. Comay. |

| 14. |

See, for example, NPS statements in H.Hrg. 115-39 and H.Hrg. 115-42; and DOI testimony at U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, Full Committee Hearing to Examine Deferred Maintenance Needs and Potential Solutions, 116th Cong., 1st sess., June 18, 2019, at https://www.energy.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/hearings-and-business-meetings?ID=69C0BD6D-0DAD-4CEC-8FE0-06946A0EA883, hereinafter cited as "Senate ENR Committee June 18, 2019, hearing." DOI stated: "[P]rivate industry standards require 2-4% of the replacement value of constructed assets be invested in maintenance each year to maintain constructed assets in good condition. In contrast, currently DOI is able to invest less than 0.5% each year." |

| 15. |

CRS communication with NPS Land Resources Division, March 16, 2017. |

| 16. |

See, for example, S.Hrg. 113-82, p. 25; and H.Hrg. 115-39, p. 48. |

| 17. |

NPS FY2021 budget justification, p. LASA-10. Also see, for example, testimony of Senator Tom Coburn, S.Hrg. 113-82, pp. 8-10. |

| 18. |

GAO, National Park Service: Process Exists for Prioritizing Asset Maintenance Decisions, but Evaluation Could Improve Efforts, GAO-17-136, December 2016, at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-17-136, hereinafter cited as "GAO December 2016 report." |

| 19. |

For example, the estimates in Figure 1 and Table 2 draw on two different types of DM reports. For FY2009-FY2013, the estimates are calculated from DM ranges that NPS provided to DOI for annual departmental financial reports. Starting in FY2014, NPS began to publish separate estimates of agency DM on its website, which include some assets—such as buildings that NPS maintains but does not own—that were not included in the earlier DOI estimates. Additionally, during the earlier FY2009-FY2013 period, DOI made changes to the upper and lower boundaries of the ranges it reports for each year's DM (for more information, see CRS Report R43997, Deferred Maintenance of Federal Land Management Agencies: FY2009-FY2018 Estimates and Issues, by Carol Hardy Vincent, section on "Methodology"), Also, during the past decade, NPS was completing baseline assessments of the maintenance needs of its non-industry-standard assets (NPS FY2017 budget justification, pp. ONPS-Ops&Maint-7 to ONPS-Ops&Maint-8); and in 2014, NPS reported unpaved roads for the first time as part of its DM estimate (CRS communication with DOI, February 27, 2015). |

| 20. |

NPS, "Deferred Maintenance 101," July 2019, p. 7, at https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1892/upload/DM101_Presentation.pdf; and CRS communication with NPS Park Facility Management Division, May 5, 2020. |

| 21. |

NPS, NPS Deferred Maintenance by State and Park, September 30, 2018, at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/infrastructure/upload/NPS-Deferred-Maintenance-FY18-State_and_Park_2018.pdf. |

| 22. |

However, Wyoming's total is due mainly to DM for Yellowstone National Park ($563.4 million) rather than DM for the John D. Rockefeller Memorial Parkway ($7.6 million), which has significantly lower DM than the other three parkways. |

| 23. |

Additionally, DM for Colonial National Historical Park, also among the units with the highest backlogs, is largely attributed to maintenance needs for the Colonial Parkway. See, for example, Alexa Doiron, "Colonial National Historical Park Awaits $420 Million in Backlogged Repairs," Williamsburg Yorktown Daily, February 25, 2019, at https://wydaily.com/local-news/2019/02/25/colonial-national-historical-park-awaits-420-million-in-backlogged-repairs-now-what/. |

| 24. |

NPS, "Preserving National Parks for the 21st Century," at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/infrastructure/upload/NPS_DM_FactSheet-Infograph1_FINAL_508-1.pdf. |

| 25. |

NPS, "Mega Projects: Transportation Needs Beyond the Capacity of the Core Program," at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/transportation/megaprojects.htm. See https://www.nps.gov/subjects/transportation/megaprojects.htm for a list of transportation mega-projects that NPS deemed "compliance-ready" as of February 2020, meaning that regulatory compliance work was complete or almost complete as of that time. |

| 26. |

The estimate of $227 million applied to the project as a whole, but does not represent current needs, since a portion of the work has already been completed (see, e.g., NPS, "Arlington Memorial Bridge rehabilitation project reaches halfway point," press release, October 9, 2019, at https://www.nps.gov/gwmp/learn/news/arlington-memorial-bridge-rehabilitation-project-reaches-halfway-point.htm). For further information on the Memorial Bridge project, see NPS, "Mega-Projects Fact Sheets: Arlington Memorial Bridge Rehabilitation," at https://www.nps.gov/articles/memorial-bridge-repair-and-reconstruction.htm; and NPS, "Arlington Memorial Bridge Rehabilitation," at https://www.nps.gov/gwmp/learn/management/amb-rehabilitation.htm. |

| 27. |

For more information on the Tamiami Trail project, see NPS, "Mega-Projects Fact Sheets: Tamiami Trail, Next Steps," at https://www.nps.gov/articles/tamiami-trial-next-steps.htm. |

| 28. |

See NPS, "Series: Mega-Projects Fact Sheets," at https://www.nps.gov/articles/series.htm?id=1B696982-A2CF-34EA-97A9AF144A5F163C. |

| 29. |

Pew Charitable Trusts, "Grand Canyon National Park fact sheet," 2017, at https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2017/08/parks_grand_canyon_updated.pdf; Pew Charitable Trusts, "National Mall and Memorial Parks fact sheet," 2018, at https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2018/01/national-mall-and-memorial-parks-case-study.pdf. |

| 30. |

Although it is not possible to determine amounts allocated to NPS deferred maintenance, GAO estimated amounts allocated for all NPS maintenance (including DM, cyclic maintenance, and day-to-day maintenance activities) for FY2006-FY2015. GAO estimated that, over that decade, NPS's annual spending for all types of maintenance averaged $1.182 billion per year (GAO December 2016 report, figure 2, p. 9). GAO did not determine what portion of this funding went specifically to DM. The report evaluates maintenance spending from four major sources: NPS's "Facility Operations and Maintenance" budget activity, the agency's "Line Item Construction" budget activity, recreation fees, and NPS allocations from the Department of Transportation under the Federal Lands Transportation Program. It does not include some additional types of funding that may be used for maintenance (including DM), such as funding received through donations. See p. 11 of the GAO December 2016 report for a description of the different types of maintenance activities covered by each funding source. |

| 31. |

See, for example, testimony of Marcia Argust, Pew Charitable Trusts, H.Hrg., 115-42, March 20, 2018, p. 20. In 2013, NPS had testified that DM funding of $700 million annually would be required to hold the maintenance backlog steady without further growth (S.Hrg. 113-82, p. 20). |

| 32. |

Specifically, "Repair and Rehabilitation" is a budget subactivity within a broader budget activity titled "Facility Operations and Maintenance," which in turn lies within the Operation of the National Park System (ONPS) account. The "Line-Item Construction" activity lies within a larger budget account titled "Construction." |

| 33. |

NPS FY2021 budget justification, pp. ONPS-65 to ONPS-66. |

| 34. |

For example, NPS estimated that over the FY2012-FY2017 period, a range from 49% to 83% of R&R funds were specifically targeted to DM, as opposed to other types of maintenance. NPS, "Deferred Maintenance 101," July 2019, p. 8, at https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1892/upload/DM101_Presentation.pdf; CRS communication with NPS Park Facility Management Division, May 5, 2020; and CRS communication with NPS Offices of Budget, Commercial Services, and Park Facility Management, May 25, 2017. |

| 35. |

NPS FY2021 budget justification, pp. CONST-11. This budget activity also supports construction of new facilities in some cases, "when supported by an approved planning document, economic analysis, and business case." |

| 36. |

NPS FY2021 budget justification, pp. CONST-11. |

| 37. |

For example, NPS estimated that over the FY2012-FY2017 period, annual Line-Item Construction funds used specifically for DM ranged from a low of 59% to a high of 87%. "Deferred Maintenance 101," July 2019, p. 8, at https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1892/upload/DM101_Presentation.pdf; CRS communication with NPS Park Facility Management Division, May 5, 2020; and CRS communication with NPS Offices of Budget, Commercial Services, and Park Facility Management, May 25, 2017. |

| 38. |

NPS FY2021 budget justification, p. CC-1. |

| 39. |

For example, the closures, and any potential reductions in visitation due to COVID-19 after parks reopen, could potentially affect revenues from entrance fees and concessions. |

| 40. |

Allowable uses of the funding include, among others, transportation planning, program administration, research, preventive maintenance, engineering, rehabilitation, restoration, construction, and reconstruction of federal lands transportation facilities (23 U.S.C. §203(a)). |

| 41. |

NPS budget justifications (see, for example, NPS FY2021 budget justification, p. CONST-47). The remaining transportation improvements were funded through sources such as NPS discretionary appropriations in the ONPS account, transportation fees, and assistance provided through NPS agreements with nonprofit organizations and private corporations. |

| 42. |

The FAST Act authorization expires after FY2020. For a discussion of surface transportation reauthorization, see CRS In Focus IF11300, Surface Transportation Reauthorization and the America's Transportation Infrastructure Act (S. 2302), by Robert S. Kirk. |

| 43. |

Related programs include the Federal Lands Access Program and others. For more information, see Federal Highway Administration, Office of Federal Lands Highway, "Programs," at https://flh.fhwa.dot.gov/programs/. |

| 44. |

See, for example, DOI, "Under Budget & Ahead of Schedule: Secretary Zinke Announces Full Funding to Repair Arlington Memorial Bridge," press release, December 1, 2017, at https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/under-budget-ahead-schedule-secretary-zinke-announces-full-funding-repair-arlington. For more information on NPS mega-projects, see the question on "What Types of Projects Account for the Largest Share of NPS Deferred Maintenance?" |

| 45. |

In most cases, at least 80% of the revenue collected is retained and used at the site where it was generated. The remaining collections are placed in a central fund that can be used throughout the park system. The funds are available without further appropriation. For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10151, Federal Lands Recreation Enhancement Act: Overview and Issues, by Carol Hardy Vincent. |

| 46. |

NPS FY2021 budget justification, p. Rec Fee-1. The estimates include fees collected under a separate program, the Deed-Restricted Parks Fee Program, which covers recreation fees collected at three park units that are prohibited by deed restrictions from collecting entrance fees. |

| 47. |

NPS FY2021 budget justification, p. RecFee-2. Specifically, these must be facility projects, a majority of whose net construction costs consist of deferred maintenance. Parks may expend the remainder of their revenues on cost of collection and on any projects or programs that meet FLREA requirements at 16 U.S.C. §6807, including facility projects that have a smaller share of costs attributed to DM. Parks may request temporary waivers of the 55% target, especially to address significant capital improvement needs that directly benefit visitors (CRS communication with NPS Park Facility Management Division, May 5, 2020). |

| 48. |

The collecting unit retains 80% of the fees, and the remainder are placed in a special account to support activities throughout the park system (54 U.S.C. §101917(c)). |

| 49. |

CRS communication with NPS Offices of Budget, Commercial Services, and Park Facility Management, May 25, 2017. |

| 50. |

NPS FY2021 budget justification, p. OPA-1. The amounts include both concessions franchise fees and an earlier type of fee recovery used in some older concessions contracts, whereby companies deposited a portion of gross receipts or a fixed sum of money in "concessions improvement accounts." |

| 51. |

Specifically, any amounts collected in excess of $10 million from NPS sales of age-discounted National Parks and Federal Recreational Lands Passes for seniors are to be deposited into the Centennial Challenge Fund as offsetting collections (P.L. 114-289). |

| 52. |

NPS FY2021 budget justification, p. CCF-1. |

| 53. |

P.L. 114-289, §101. |

| 54. |

P.L. 114-289, §201. |

| 55. |

54 U.S.C. §101101 authorizes the Secretary of the Interior to accept donations for the purposes of the park system. In addition to direct donations to NPS, the agency receives donated funds through the congressionally chartered National Park Foundation and through individual park "friends groups," among other sources. |

| 56. |

NPS FY2021 budget justification, p. MTF-1. |

| 57. |

See, for example, H.Hrg. 115-39, March 6, 2018, p. 36. |

| 58. |

See, for example, H.Hrg. 115-42, March 20, 2018, p. 40. |

| 59. |

In addition to the bills discussed below in the section on 116th Congress legislation, an NPS DM fund from energy revenues has also been proposed in previous Congresses. See, for example, H.R. 2584 (115th Congress); H.R. 5210 (115th Congress); H.R. 6510 (115th Congress); S. 751 (115th Congress); S. 1460 (115th Congress); S. 2509 (115th Congress); S. 3172 (115th Congress); H.R. 4151 (114th Congress); S. 2011 (114th Congress); S. 2012 (114th Congress); and S. 2817 (110th Cong.). |

| 60. |

See, for example, statement of Rep. Raúl Grijalva, House Committee on Natural Resources, Exploring Innovative Solutions to Reduce the Department of the Interior's Maintenance Backlog, H.Hrg. 115-39, March 6, 2018, p. 3, at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-115hhrg28851/pdf/CHRG-115hhrg28851.pdf; and statements in H.Hrg. 115-42, March 20, 2018, pp. 22, 26, and 36. As a possible way of using energy revenues for NPS DM without incentivizing additional production, some have suggested that DM should be funded from new fees and charges on existing production, such as an increase in rents and royalty rates for oil and gas production on federal lands. See, for example, Center for Western Priorities, Funding America's Public Lands Future: How Innovation and Leadership Can Conserve Our Natural Heritage for Future Generations, November 2019, at https://westernpriorities.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Conservation_Funding_2019_FINAL_CWP.pdf. |

| 61. |

In addition to S. 2783 in the 116th Congress (discussed below), see, for example, H.R. 2863 (115th Congress); S. 268 (114th Congress); H.R. 5220 (113th Congress); H.R. 1731 (110th Congress); H.R. 3094 (110th Congress); S. 2817 (110th Congress); S. 886 and H.R. 1124 (109th Congress); and H.R. 5358 (108th Congress). Also see Heritage Foundation, Budget Proposals: Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies, section on "Prohibit the net acquisition of land and shift federal land holdings to states and the private sector," May 20, 2019, at https://www.heritage.org/blueprint-balance/budget-proposals/interior-environment-and-related-agencies; Heritage Foundation, "Permanent Reauthorization of Land and Water Conservation Fund Opens Door to Permanent Land Grabs," January 22, 2019, at https://www.heritage.org/environment/report/permanent-reauthorization-land-and-water-conservation-fund-opens-door-permanent; and National Park Hospitality Association and National Parks Conservation Association, Sustainable Supplementary Funding for America's National Parks, March 19, 2013. |

| 62. |

In addition to S. 2783 in the 116th Congress (discussed below), see Pew Charitable Trusts and AECOM, Protecting Our Parks: A Strategic Approach to Reducing the Deferred Maintenance Backlog Facing the National Park Service, Spring 2019, at https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2019/05/protecting-our-parks-report_low-res.pdf; Property and Environment Research Center, Breaking the Backlog: Seven Ideas to Address the National Park Deferred Maintenance Problem, February 2016, pp. 15-19, at https://www.perc.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/BreakingtheBacklog_7IdeasforNationalParks.pdf; and National Park Hospitality Association and National Parks Conservation Association, Sustainable Supplementary Funding for America's National Parks, March 19, 2013. |

| 63. |

See, for example, H.R. 1577 (115th Congress); Pew Charitable Trusts and AECOM, Protecting Our Parks: A Strategic Approach to Reducing the Deferred Maintenance Backlog Facing the National Park Service, Spring 2019, at https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2019/05/protecting-our-parks-report_low-res.pdf; and Property and Environment Research Center, Breaking the Backlog: Seven Ideas to Address the National Park Deferred Maintenance Problem, February 2106, pp. 15-19, at https://www.perc.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/BreakingtheBacklog_7IdeasforNationalParks.pdf. |

| 64. |

For general information on NPS management of the DM backlog, see NPS, "Identifying & Reporting Deferred Maintenance," at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/infrastructure/identifying-reporting-deferred-maintenance.htm; NPS FY2021 budget justification, p. ONPS-65; and NPS, "Deferred Maintenance 101," July 2019, at https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1892/upload/DM101_Presentation.pdf. Also see NPS Director's Order 80, "Real Property Asset Management," at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/policy/upload/DO_80_11-20-2006.pdf. |

| 65. |

The agency defines an asset as "real property that the NPS tracks and manages as a distinct, identifiable entity. These entities may be physical structures or groupings of structures; landscapes; or other tangible properties that have a specific service or function, such as a farm, cemetery, campground, marina, or sewage treatment plant." NPS, "Identifying & Reporting Deferred Maintenance," at https://www.nps.gov/subjects/infrastructure/identifying-reporting-deferred-maintenance.htm. |

| 66. |

Park managers assign to each asset a facility condition index (FCI) rating—a ratio representing the cost of DM for the asset divided by the asset's replacement value. (A lower FCI rating indicates a better condition.) The replacement value is defined as "the standard industry costs and engineering estimates of materials, supplies and labor required to replace a facility at its existing size and functional capability." NPS, "Deferred Maintenance 101," July 2019, at https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1892/upload/DM101_Presentation.pdf. |

| 67. |

These factors collectively make up the asset priority index (API) rating for a given asset. For more information, see NPS Park Facility Management Division, "Park Facility Maintenance—Explanation of Some Terminology and Concepts," at https://mylearning.nps.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Park_Facility_Management_Terminology_and_Concepts.pdf. |

| 68. |

NPS Park Facility Management Division, "Park Facility Maintenance—Explanation of Some Terminology and Concepts," at https://mylearning.nps.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Park_Facility_Management_Terminology_and_Concepts.pdf. |

| 69. |

NPS, "Park Planning, Facilities, and Lands: Asset Portfolio Fact Sheet," November 2018, at https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1892/upload/NPS-Asset-Portfolio-Fact-Sheet-FY2018.pdf. |

| 70. |

Ibid. |

| 71. |

Ibid. |

| 72. |

NPS, "Deferred Maintenance 101," July 2019, p. 6, at https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1892/upload/DM101_Presentation.pdf. NPS has stated that "[m]ost projects … include both deferred and non-deferred maintenance components" (H.Hrg. 115-42, March 20, 2018, p. 13, at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-115hhrg29422/pdf/CHRG-115hhrg29422.pdf). |

| 73. |

GAO December 2016 report. GAO also had reported in earlier years on successes and challenges in NPS asset management; see, for example, GAO, National Park Service: Status of Efforts to Develop Better Deferred Maintenance Data, April 2002, at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-02-568R; and GAO, National Park Service: Efforts to Identify and Manage the Maintenance Backlog, May 1998, at http://www.gao.gov/products/RCED-98-143. |

| 74. |

Ibid., pp. 34-37. |

| 75. |

Ibid., pp. 30-37. The Capital Investment Strategy used during the Obama Administration sought to guide park managers in evaluating and prioritizing capital investment projects, in order "to focus capital investments on a subset of our facilities that represent our highest priority needs with a commitment for long-term maintenance component" (NPS, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2015, at https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/upload/FY-2015-Greenbook-Linked.pdf). The strategy contains a scoring algorithm based on financial sustainability, visitor use, resource protection, and health and safety (NPS, "Park Planning, Facilities, and Lands: Asset Portfolio Fact Sheet," November 2018, at https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1892/upload/NPS-Asset-Portfolio-Fact-Sheet-FY2018.pdf). |

| 76. |

Part of NPS's asset management strategy includes identifying assets that may be candidates for demolition or disposal. For example, some assets may have high FCI ratings, indicating expensive maintenance needs, along with low API ratings, indicating that they are not of high importance to the NPS mission. NPS identifies assets that are candidates for disposal as part of its real property reporting to the General Services Administration (GSA). GSA's Federal Real Property Public Data Set, available at https://www.gsa.gov/policy-regulations/policy/real-property-policy/asset-management/federal-real-property-profile-frpp/federal-real-property-public-data-set, includes DOI-wide properties with the status "Determination to Dispose." |

| 77. |

NPS, FY2021 Budget Justification, p. CONST-45. |

| 78. |

See, for example, NPS, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2018, p. ONPS-Ops&Maint-11, at https://www.nps.gov/aboutus/upload/FY-2018-NPS-Greenbook.pdf. |

| 79. |

GAO, Federal Real Property: Improving Data Transparency and Expanding the National Strategy Could Help Address Long-Standing Challenges, March 2016, at http://www.gao.gov/assets/680/676406.pdf. For more information on the McKinney-Vento Act and disposal of federal property, see CRS Report R43247, Disposal of Unneeded Federal Buildings: Legislative Proposals in the 113th Congress, by Garrett Hatch. |

| 80. |

Letter from P. Daniel Smith, NPS Deputy Director Exercising the Authority of the Director, to Rep. Rob Bishop, July 2, 2019. |

| 81. |