U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: An Overview

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), an agency within the Department of the Interior (DOI), is the principal federal agency tasked with the conservation, protection, and restoration of fish and wildlife resources across the United States and insular areas. This report summarizes the history, organizational structure, and selected functions of FWS and provides an overview of the agency’s appropriations structure. The report describes the actions Congress has taken to shape FWS’s structure and functions over time and notes selected issues of interest to Congress.

The current structure of FWS is the result of more than 150 years of agency and departmental reorganizations. FWS began as two agencies: the Office of the Commission of Fish and Fisheries (established as an independent agency in 1871) and the Bureau of the Biological Survey (established in 1885 as an outgrowth of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s [USDA’s] Division of Entomology). These two entities evolved into the Bureau of Fisheries (in the Department of Commerce) and the Bureau of Biological Survey in USDA. They were consolidated and established within DOI as the Fish and Wildlife Service in 1939. After that time, the service was further restructured on several occasions through both presidential reorganizations and congressional statutes. The most recent major reorganization took place in 1970, although FWS has continued to evolve pursuant to the passage of additional laws and the addition of new responsibilities. In its current form, FWS contains national, regional, and field offices spread across the United States, including its headquarters in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area, eight regional headquarter offices, and other field and FWS-administered sites.

Pursuant to authorizing statutes, FWS is responsible for a multitude of fish- and wildlife-related activities. These activities include administering the National Wildlife Refuge System; managing migratory bird species; protecting endangered and threatened species; restoring fish species and aquatic habitats; enforcing fish, wildlife, and conservation laws; conducting international conservation efforts; and disbursing financial and technical assistance to states, territories, and Indian tribes for wildlife and sport fish restoration and other activities.

For example, FWS is responsible for the enforcement of several wildlife-related statutes and international agreements, such as the Endangered Species Act (16 U.S.C. §§1531 et seq.), the Lacey Act (16 U.S.C. §§3371-3378 and 18 U.S.C. §§42-43), and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (16 U.S.C. §§703-712). The service administers the National Wildlife Refuge System pursuant to the National Wildlife Refuge System Administration Act (16 U.S.C. §§668dd-668ee), as amended, which includes more than 800 million acres of lands and waters that FWS administers through either primary or secondary jurisdiction, including 566 national wildlife refuges as well as other service lands and waters. FWS also manages more than 70 national fish hatcheries, fish health centers, and fish technology centers and oversees the Aquatic Animal Drug Approval Partnership Program. In addition, FWS coordinates both domestic and international conservation activities, including administering multiple international conservation statutes. FWS also is responsible for disbursing financial assistance pursuant to the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act (known as the Pittman-Robertson Act; 16 U.S.C. §§669 et seq.) and the Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration Act (commonly known as the Dingell-Johnson Act; 16 U.S.C. §§777 et seq.), as well as State and Tribal Wildlife grants. From FY2014 through FY2018, Pittman-Robertson and Dingell-Johnson allocations together provided more than $1 billion annually to states, territories, and DC for wildlife and sport fish restoration and hunter education.

FWS is funded through a mix of discretionary and mandatory appropriations. Discretionary appropriations, which averaged $1.5 billion annually from FY2009 through FY2018, regularly have been allocated across nine accounts and have supported many of the agency’s essential functions. FWS mandatory funding, which averaged $1.2 billion annually from FY2009 through FY2018, predominately has been derived through revenues generated from excise taxes on hunting- and fishing-related equipment. Mandatory funding supports land acquisition and financial assistance activities, including a significant portion of FWS’s grant-making activities to states and insular areas.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: An Overview

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- History of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- Agencies Preceding the Fish and Wildlife Service

- Fish and Fisheries

- Wildlife and Birds

- Reorganization and Establishment

- The Fish and Wildlife Service

- The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- Further Reorganization

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Organizational Structure

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Regions

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Programs

- National Wildlife Refuge System

- Fish and Aquatic Conservation

- Endangered and Protected Species

- Migratory Birds

- International Conservation

- Law Enforcement

- Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Grant Programs

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Appropriations

- Discretionary Appropriations

- Mandatory Appropriations

- Supplemental Appropriations

- American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009

- Disaster Relief Appropriations Act of 2013

- Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018

Figures

- Figure 1. Timeline of Selected Establishments and Reorganizations Related to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS)

- Figure 2. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Organizational Chart

- Figure 3. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Regional Boundaries

- Figure 4. Timeline of Selected Statutes and Conventions Relevant to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- Figure 5. Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration (Pittman-Robertson) and Sport Fish Restoration (Dingell-Johnson) Funding, FY1939-FY2018

- Figure 6. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Discretionary and Mandatory Appropriations, FY2009-FY2018

- Figure 7. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Discretionary Appropriations by Account, Average FY2009-FY2018

- Figure 8. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Mandatory Appropriations by Account, Average FY2009-FY2018

Summary

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), an agency within the Department of the Interior (DOI), is the principal federal agency tasked with the conservation, protection, and restoration of fish and wildlife resources across the United States and insular areas. This report summarizes the history, organizational structure, and selected functions of FWS and provides an overview of the agency's appropriations structure. The report describes the actions Congress has taken to shape FWS's structure and functions over time and notes selected issues of interest to Congress.

The current structure of FWS is the result of more than 150 years of agency and departmental reorganizations. FWS began as two agencies: the Office of the Commission of Fish and Fisheries (established as an independent agency in 1871) and the Bureau of the Biological Survey (established in 1885 as an outgrowth of the U.S. Department of Agriculture's [USDA's] Division of Entomology). These two entities evolved into the Bureau of Fisheries (in the Department of Commerce) and the Bureau of Biological Survey in USDA. They were consolidated and established within DOI as the Fish and Wildlife Service in 1939. After that time, the service was further restructured on several occasions through both presidential reorganizations and congressional statutes. The most recent major reorganization took place in 1970, although FWS has continued to evolve pursuant to the passage of additional laws and the addition of new responsibilities. In its current form, FWS contains national, regional, and field offices spread across the United States, including its headquarters in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area, eight regional headquarter offices, and other field and FWS-administered sites.

Pursuant to authorizing statutes, FWS is responsible for a multitude of fish- and wildlife-related activities. These activities include administering the National Wildlife Refuge System; managing migratory bird species; protecting endangered and threatened species; restoring fish species and aquatic habitats; enforcing fish, wildlife, and conservation laws; conducting international conservation efforts; and disbursing financial and technical assistance to states, territories, and Indian tribes for wildlife and sport fish restoration and other activities.

For example, FWS is responsible for the enforcement of several wildlife-related statutes and international agreements, such as the Endangered Species Act (16 U.S.C. §§1531 et seq.), the Lacey Act (16 U.S.C. §§3371-3378 and 18 U.S.C. §§42-43), and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (16 U.S.C. §§703-712). The service administers the National Wildlife Refuge System pursuant to the National Wildlife Refuge System Administration Act (16 U.S.C. §§668dd-668ee), as amended, which includes more than 800 million acres of lands and waters that FWS administers through either primary or secondary jurisdiction, including 566 national wildlife refuges as well as other service lands and waters. FWS also manages more than 70 national fish hatcheries, fish health centers, and fish technology centers and oversees the Aquatic Animal Drug Approval Partnership Program. In addition, FWS coordinates both domestic and international conservation activities, including administering multiple international conservation statutes. FWS also is responsible for disbursing financial assistance pursuant to the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act (known as the Pittman-Robertson Act; 16 U.S.C. §§669 et seq.) and the Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration Act (commonly known as the Dingell-Johnson Act; 16 U.S.C. §§777 et seq.), as well as State and Tribal Wildlife grants. From FY2014 through FY2018, Pittman-Robertson and Dingell-Johnson allocations together provided more than $1 billion annually to states, territories, and DC for wildlife and sport fish restoration and hunter education.

FWS is funded through a mix of discretionary and mandatory appropriations. Discretionary appropriations, which averaged $1.5 billion annually from FY2009 through FY2018, regularly have been allocated across nine accounts and have supported many of the agency's essential functions. FWS mandatory funding, which averaged $1.2 billion annually from FY2009 through FY2018, predominately has been derived through revenues generated from excise taxes on hunting- and fishing-related equipment. Mandatory funding supports land acquisition and financial assistance activities, including a significant portion of FWS's grant-making activities to states and insular areas.

Introduction

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), an agency within the Department of the Interior (DOI), is the principal federal agency tasked with the conservation, protection, and restoration of fish and wildlife resources across the United States and insular areas. The service's history dates to 1871, when the Office of the Commission of Fish and Fisheries—a predecessor to FWS—was established. FWS manages both regional and national programs, which are carried out by FWS staff at headquarters, regional offices, and field offices. FWS functions include administering the National Wildlife Refuge System, managing migratory bird species, protecting endangered and threatened species, and restoring fish species and aquatic habitats, as well as enforcing fish, wildlife, and conservation laws and conducting international conservation efforts. FWS also is responsible for the disbursement of fish and wildlife conservation and restoration funds to states, territories, and tribal governments.

This report summarizes the history, organizational structure, and selected functions of FWS and provides an overview of the agency's appropriations structure. The report describes the actions Congress has taken to shape the structure and functions of FWS over time and notes selected issues of interest to Congress.

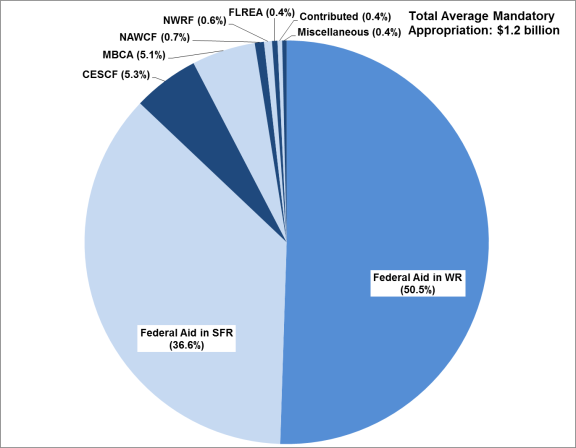

History of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

The origins of FWS date back to the formation of two agencies in the late 1800s. In 1871, the first of FWS's predecessor agencies, the Office of the Commission of Fish and Fisheries (an independent agency), was established. In 1885, the second agency that later would become part of FWS, the Section of Economic Ornithology, was formed within the Department of Agriculture (USDA). After several administrative and legislative reorganizations to these agencies, FWS took its current form in DOI in the second half of the 20th century. (See Figure 1 for a timeline of selected events that helped to structure the agency.) Additional details on the administrative and congressional actions that have shaped the agency are provided below.

|

Figure 1. Timeline of Selected Establishments and Reorganizations Related to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) |

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS). See relevant subsection of "History of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service" for individual citations. |

Agencies Preceding the Fish and Wildlife Service

Fish and Fisheries

On February 9, 1871, Congress created the Office of the Commission of Fish and Fisheries, commonly referred to as the Fish Commission, to respond to a perceived decline in marine and freshwater fish stocks in American waters.1 The Fish Commission was established as an independent agency and tasked with investigating the cause of the decline and providing recommendations to mitigate it. In this role, the Fish Commission analyzed and reported on the commercial fishing industry and actively propagated species of interest to bolster populations.

The Fish Commission remained an independent agency until February 1903, after which the office was integrated into the newly created Department of Commerce and Labor and renamed the Bureau of Fisheries.2 In addition to the responsibilities held by the Fish Commission, the Bureau of Fisheries assumed responsibility for several additional activities, including management of the salmon fishery and fur-bearing animals in Alaska.3

In 1913, the Department of Commerce and Labor was divided into two separate departments, the newly created Department of Labor and the renamed Department of Commerce (DOC).4 After the division, the Bureau of Fisheries, which remained in DOC, again was tasked with additional responsibilities, including the enforcement of the Federal Black Bass Act and the Whaling Treaty Act, as well as increased responsibilities in Alaska.5 In addition to these and other activities, the Bureau of Fisheries continued to work to mitigate threats to fisheries and bolster fish stocks, including through the operation of fish hatcheries.

The Bureau of Fisheries remained within DOC through June 1939.

Wildlife and Birds

In 1885, USDA established the Section of Economic Ornithology within the Division of Entomology, using funds appropriated to the division.6 The section was tasked with investigating the food habits, distribution, and migrations of birds in relation to agriculture, including insects and plants.7 In 1886, the section became a stand-alone division within USDA, known as the Division of Economic Ornithology and Mammalogy, and its responsibilities were expanded to include mammals.8 The mandate for the division continued to expand over the next several years to include mammals and birds as they related to agriculture, horticulture, and forestry, as well as the general geographic distribution of animals and plants.9

The Division of Economic Ornithology and Mammalogy later was renamed the Division of Biological Survey in 1896.10 The renaming recognized the expansion of the division's responsibilities to broadly investigate America's wildlife and plants, including their geographic distribution. The division was renamed again in 1905 as the Bureau of Biological Survey.11

Over the next 34 years, the bureau's responsibilities broadened to include various conservation and regulatory activities. During this time, several sections and divisions were created within the bureau. Each of these divisions had specific responsibilities, including habitat loss, non-native species, species endangerment, and control of predatory and injurious wildlife. In addition, the bureau was tasked with the enforcement of conservation laws and the administration of wildlife refuge lands, which were designated by Administrations and Congress for the conservation of wildlife and birds. These wildlife refuges ultimately would be consolidated into the National Wildlife Refuge System (see "National Wildlife Refuge System").

The Bureau of Biological Survey remained within USDA through June 1939.

Reorganization and Establishment

The Fish and Wildlife Service

The Bureau of Fisheries and the Bureau of Biological Survey were transferred from their respective homes within DOC and USDA by Reorganization Plan Number II of 1939.12 To consolidate conservation and wildlife resource activities, the reorganization plan moved the bureaus to DOI, effective July 1, 1939. The plan transferred all of the bureaus' associated responsibilities and authorities with them,13 including the regulatory authorities over fisheries and the whaling industry for the Bureau of Fisheries and the conservation of wildlife, game, and migratory birds and conservation law enforcement for the Bureau of Biological Survey.

In a message regarding Reorganization Plan Number II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt provided justification for the transfer:

The plan provides for the transfer to the Department of the Interior of the Bureau of Fisheries from the Department of Commerce and of the Bureau of Biological Survey from the Department of Agriculture. These two Bureaus have to do with conservation and utilization of the wildlife resources of the country, terrestrial and aquatic. Therefore, they should be grouped under the same departmental administration, and in that Department which, more than any other, is directly responsible for the administration and conservation of the public domain.14

One year after the bureaus were transferred to DOI, the President proposed a further consolidation as part of Reorganization Plan Number III of 1940.15 Effective June 30, 1940, the Bureau of Fisheries and the Bureau of Biological Survey were combined to form the Fish and Wildlife Service.16 In establishing the Fish and Wildlife Service, the plan also created the position of director within the agency and abolished the former positions heading the two original bureaus.

In his attached message, President Roosevelt explained the further consolidation:

Reorganization Plan II transferred the Bureau of Fisheries of the Department of Commerce and the Bureau of Biological Survey of the Department of Agriculture to the Department of the Interior and thus concentrated in one department the two bureaus responsible for the conservation and utilization of the wildlife resources of the Nation. On the basis of experience gained since this transfer, I find it necessary and desirable to consolidate these units into a single bureau to be known as the Fish and Wildlife Service.

The Bureau of Biological Survey administers Federal laws relating to birds, land mammals, and amphibians whereas the Bureau of Fisheries deals with fishes, marine mammals, and other aquatic animals. The natural areas of operation of these two bureaus frequently coincide, and their activities are interrelated and similar in character. Consolidation will eliminate duplication of work, facilitate coordination of programs, and improve service to the public.17

Shortly after the consolidation, the Fish and Wildlife Service's headquarters was temporarily relocated from Washington, DC, to Chicago, IL, in 1942 due to World War II. The service returned to Washington, DC, in 1947.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (as opposed to its earlier moniker, the Fish and Wildlife Service), or FWS, was established as a result of legislation passed in 1956.18 The Fish and Wildlife Act of 1956 both established FWS and created the position of Commissioner of Fish and Wildlife to lead the agency.19 The act also created the position of Assistant Secretary for Fish and Wildlife within DOI and established that FWS would be comprised of two bureaus—the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries and the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife—each headed by its own director.

The Fish and Wildlife Act further specified the division of the existing responsibilities held within the predecessor agency between the two new bureaus. Specifically, the act states

(1) The Bureau of Commercial Fisheries shall be responsible for those matters to which this Act applies relating primarily to commercial fisheries, whales, seals, and sea-lions, and related matters;

(2) The Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife shall be responsible for those matters to which this Act applies relating primarily to migratory birds, game management, wildlife refuges, sport fisheries, sea mammals (except whales, seals and sea-lions), and related matters.... 20

In addition to renaming and reorganizing FWS, the act declared as policy that fish and wildlife resources "make a material contribution to our national economy and food supply, as well as a material contribution to the health, recreation, and well-being of our citizens."21 The act also stipulated that all functions related to fisheries, wildlife management, and conservation previously administered by DOC and USDA were to be transferred to DOI.22

Further Reorganization

Reorganization Plan Number IV of 1970 restructured FWS by transferring the responsibilities entrusted to the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA; also created by the reorganization plan), housed within DOC.23 This reorganization shifted back much of the responsibility that had grown out of the original Bureau of Fisheries, which had been housed in DOC prior to being transferred to DOI in 1939.24 (See "Fish and Fisheries," above.)

Since its passage, the Fish and Wildlife Act of 1956 has been amended multiple times.25 In particular, P.L. 93-271 (enacted in 1974) provided for further reorganization of FWS, paving the way for the agency's current structure.26 Among other things, P.L. 93-271 consolidated the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife under FWS. FWS, under the act, was to "succeed to and replace the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (as constituted on June 30, 1974) and the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife (as constituted on such date)."27 In replacing the previous FWS structure, the act transferred all existing authorities and responsibilities to the consolidated FWS.

P.L. 93-271 also abolished the position of Commissioner of Fish and Game and established the position of the Director of FWS to administer the agency under the supervision of the Assistant Secretary of Fish and Wildlife within DOI. The law stipulated that the director position requires appointment by the President and confirmation by the Senate. In addition, the act established a positive education and experience requirement for the director: "No individual may be appointed as the Director unless he is, by reason of scientific education and experience, knowledgeable in the principles of fisheries and wildlife management."28

Since 1974, the service has grown and adapted to its current structure and continued as the principal federal agency responsible for the conservation, protection, and restoration of fish and wildlife resources in the United States. FWS reorganization is still a topic of interest to both the Administration and Congress. Congress has regularly debated shifting responsibilities into or out of FWS jurisdiction. Likewise, on several occasions, Administrations have discussed or proposed reorganizations that would shift responsibilities and redistribute FWS staff and resources.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Organizational Structure

FWS is composed of a three-tier structure, including national, regional, and field offices spread across the United States and insular areas. In 2017, FWS employed approximately 9,000 people, though the number of employees varied throughout the year.29 The national level is primarily responsible for policy formulation and budget allocation, and the regional and field offices are responsible for implementing and enforcing policy.30 In addition, FWS administers 566 national wildlife refuges and 70 national fish hatcheries, as well as national monuments (four within the National Wildlife Refuge System and three under other authorities), other fisheries offices, and field stations.31 In total, FWS administers 856 million acres of lands, submerged lands, and waters, under primary or secondary jurisdiction, of which 146 million acres are included in national wildlife refuges and 705 million acres are in mostly marine national monuments.32

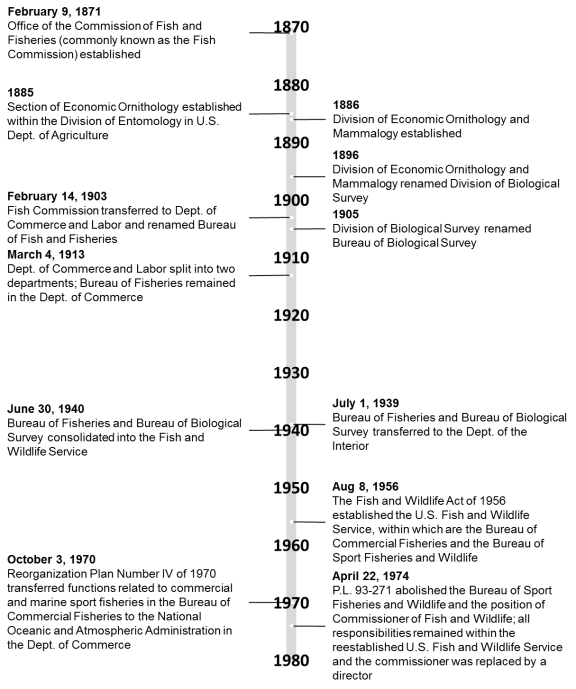

At the national level, which has its headquarters in the Washington, DC, metropolitan area, FWS is administered by the Director of FWS, who is supervised by the Assistant Secretary for Fish and Wildlife within the DOI.33 There are 13 FWS programs, such as the National Wildlife Refuge System or Law Enforcement, which are overseen by 11 assistant directors and 2 chiefs (see Figure 2).34 Most of the assistant directors and chiefs in turn supervise deputies and one or more divisions within their programs. Selected assistant director and chief positions were established in statute. For example, the position of Assistant Director for Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration was established by the Fish and Wildlife Programs Improvement and National Wildlife Refuge System Centennial Act of 2000.35

|

Figure 2. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Organizational Chart |

|

|

Source: CRS, using information from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), "National Organizational Chart," at https://www.fws.gov/offices/orgcht.html. |

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Regions

FWS is divided into eight regions, each headed by a regional director (Figure 2). The eight regions predominately coincide with state boundaries, though Oregon and Nevada each are split across two regions (see Figure 3). In addition to the continental United States, Regions 1 and 4 contain the Pacific, including Hawaii, and the Caribbean, respectively.

The programmatic structure at the regional level is similar to FWS headquarters. In addition to each regional director, regions have a leadership team composed of deputy regional directors, assistant regional directors, special agents, and regional chiefs for various programs. Assistant regional directors and/or assistant regional chiefs are responsible for programs including fisheries and aquatic conservation, the National Wildlife Refuge System, ecological services, migratory birds, science applications, budget and administration, external affairs, and wildlife and sport fish restoration. However, every region may not have an assistant regional director or chief for every program that is included at the national level. In addition, regions can have special program managers for region-specific activities (e.g., the DOI case manager for the Deepwater Horizon Natural Resource Damage Assessment in Region 4).36 Within each region are FWS sites and numerous field offices.

|

Figure 3. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Regional Boundaries |

|

|

Sources: CRS, with data from FWS Geospatial Services, "Regional Boundaries," at https://ecos.fws.gov/ServCat/Reference/Profile/52322; U.S. Census Bureau, "Cartographic Boundary Shapefiles, 2017," at https://www.census.gov/geo/maps-data/data/cbf/cbf_state.html; and ESRI. Note: Figure components are not mapped on the same scale. * Region 1 also includes other Pacific Islands not depicted here. Headquarters locations are approximate and for general orientation only. Regional headquarters are located in the following cities: Region 1—Portland, OR; Region 2—Albuquerque, NM; Region 3—Bloomington, MN; Region 4—Atlanta, GA; Region 5—Hadley, MA; Region 6—Lakewood, CO; Region 7—Anchorage, AK; and Region 8—Sacramento, CA. |

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Programs

FWS's mission is to "work with others to conserve, protect and enhance fish, wildlife and plants and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people."37 To accomplish this mission, FWS performs numerous administrative and enforcement activities, which are reflected in the agency's programmatic structure. These activities include but are not limited to the following:

- operation of the National Wildlife Refuge System;

- restoration of fisheries and fish habitats;

- protection of threatened and endangered species;

- management of migratory birds;

- assistance in international conservation efforts;

- enforcement of federal wildlife laws; and

- disbursement of funds to states and territories for wildlife and sport fish restoration and for hunting and fishing safety and education.

In addition to activities entirely carried out by FWS, cooperation, coordination, and partnerships are integral to FWS activities. The service routinely partners with other federal, state, local, tribal, and private partners to carry out activities.

Congress has codified several of FWS's programs in statutes, which provide guidance to the agency. In cases where programs are not directly established in statute, authority is derived from other FWS enabling legislation, such as the Fish and Wildlife Act of 1956 or the National Wildlife Refuge System Administration Act of 1966.38

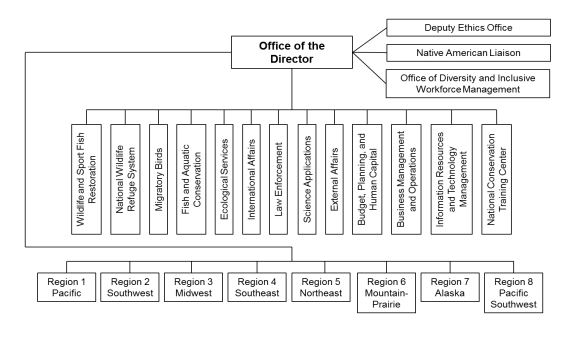

The following sections provide an overview of selected FWS programs and certain statutes, treaties, and agreements relevant to each program. (See Figure 4 for a timeline of selected statutes related to FWS.) Although many of FWS's primary responsibilities are described, not all of the service's programmatic responsibilities are discussed herein. Selected issues that may be of interest to Congress are noted in each section.

|

Figure 4. Timeline of Selected Statutes and Conventions Relevant to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |

|

|

Source: CRS. See "U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Programs" for individual citations for referenced statutes. |

National Wildlife Refuge System

The National Wildlife Refuge System (NWRS) is one of the primary public faces of FWS. The NWRS is a network of FWS-administered lands, submerged lands, and waters that provide habitat for fish and wildlife resources across the United States, U.S. territories, and other insular areas. Many NWRS units are open to the public and provide recreational opportunities, including hunting, fishing, bird-watching, and other activities. In addition to refuges, the NWRS includes several national monuments, wetland management districts, waterfowl production areas, and coordination areas.

The first wildlife conservation area that eventually would become part of the NWRS was the Pelican Island National Bird Reservation, established by President Theodore Roosevelt through an executive order signed on March 14, 1903.39 As of September 30, 2017, the NWRS contained 566 national wildlife refuges (which include wildlife refuges, wildlife ranges, wildlife management areas, game preserves, and conservation areas); 4 national monuments; 210 waterfowl production areas, which are almost entirely consolidated into 38 wetland management districts; and 50 coordination areas.40 FWS is responsible for administering, either through primary or secondary jurisdiction, more than 836 million acres as part of the NWRS; of this total, national wildlife refuges make up 146 million acres. Almost 90 million acres of these national wildlife refuges are in the 50 states; the remaining acreage is comprised of land, submerged land, and water in the territories and insular areas.41

The areas managed by FWS were not formally consolidated into a unified system until the enactment of the National Wildlife Refuge System Administration Act of 1966 (NWRSAA).42 NWRSAA has been amended several times, including through the National Wildlife Refuge System Improvement Act of 1997.43 The National Wildlife Refuge System Improvement Act, among other things, formally established that "the mission of the System is to administer a national network of lands and waters for the conservation, management, and where appropriate, restoration of the fish, wildlife, and plant resources and their habitats within the United States for the benefit of present and future generations of Americans."44 NWRSAA, as amended, further specified activities permitted within the NWRS and required that most activities that occur in national wildlife refuges be compatible with the NWRS's mission and with the purpose for which an NWRS unit was established.45 Further, NWRSAA established that wildlife-dependent recreation, including hunting and fishing, shall be priority uses of the NWRS, when it is compatible with the mission and purpose of a given unit.46

NWRS units may be established through multiple methods, including through legislation and administrative actions, such as executive orders, public land withdrawals, and agreements with other federal agencies.47 Of the 566 refuges, approximately 500 were established through administrative actions; the remaining refuges were established, reestablished, or repurposed through congressional actions.48 However, Congress has acted to modify and codify many of the administratively created refuges, making it difficult to clearly differentiate which refuges were established through administrative versus congressional action.49 Further, lands and interests in lands, including easements and other agreements, can be acquired through purchase or donation pursuant to NWRSAA and other authorities, including migratory bird-related authorities, with funds from the Migratory Bird Conservation Fund (MBCF) and the Land and Water Conservation Fund.50 (For more information on migratory bird authorities and the MBCF, see "Migratory Birds," below.)

The NWRS is served by the Refuge Law Enforcement program. Refuge law enforcement is staffed by federal wildlife officers who serve specifically in the NWRS. They provide a safe and secure visitor experience and protect FWS employees, federal property, and fish and wildlife resources. Federal wildlife officers working within the NWRS are distinct from personnel within the Office of Law Enforcement (see "Law Enforcement," below).

Congress routinely addresses issues related to the administration and funding of the NWRS. Issues of interest to Congress may include the establishment and naming of refuges and the compatibility of different activities within the NWRS, such as hunting and fishing and oil and gas activities.51

Fish and Aquatic Conservation

The Fish and Aquatic Conservation Program within FWS works to conserve, manage, and restore fish populations and their aquatic habitats. The conservation and restoration of aquatic species has been part of FWS core functions since the 1871 establishment of the Office of the Commission of Fish and Fisheries (see "Fish and Fisheries" section, above). The Fish and Aquatic Conservation program's mission is to "conserve, restore and enhance fish and other aquatic resources for the continuing benefit of the American people."52 To fulfill its mission, the Fisheries Program focuses on the propagation of fish species, species and habitat conservation, invasive species management, and the provision of recreational and educational opportunities for the public.53 Of particular importance is supporting recreational freshwater fishing opportunities across the country (NOAA in the DOC has jurisdiction over living marine resources per the 1970 reorganization that shifted the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries from DOI to DOC; see "Further Reorganization"), including through promoting public access, protecting and restoring fish habitat, and bolstering fish populations while minimizing risks associated with the introduction and spread of non-native species.

The Fish and Aquatic Conservation Program includes the National Fish Hatchery System, which is composed of 70 national fish hatcheries as well as fish health centers, fish technology centers, and the Aquatic Animal Drug Approval Partnership Program.54 The first hatchery, known as the Baird Hatchery, was established in 1872 on the McCloud River in California under the Fish Commission.55Authority for construction and operation of fish hatcheries is vested in FWS by numerous statutes, including statutes establishing specific hatcheries and those providing FWS with broader conservation and restoration authorities.56 Other fish hatcheries have been established through appropriations acts. Congress also has provided for the transfer of some fish hatcheries to nonfederal entities, such as states or universities.

National fish hatcheries are responsible for the propagation of fish species related to recreation and public use, endangered and imperiled species recovery, and fulfillment of tribal partnerships and responsibilities.57 In addition, in cooperation with states, tribes, and other groups, FWS works to conduct research aimed at better understanding the ecology of fish species, and the Fisheries Program uses applied science to inform fisheries' conservation practices. Both fish health centers and fish technology centers are integral to scientific pursuits undertaken by the National Fish Hatchery System.

In addition to conducting research into fish diversity, distributions, conservation, and management, the Fish and Aquatic Conservation Program contains the Aquatic Animal Drug Approval Partnership Program, which works to obtain approval of medications used in fish culture and fisheries management from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.58

The Fisheries Program also is responsible for addressing aquatic invasive species, also known as aquatic nuisance species. The Aquatic Invasive Species (AIS) Program is authorized through the National Invasive Species Act of 1996,59 which amended the Nonindigenous Aquatic Nuisance Prevention and Control Act of 1990.60 The AIS Program funds regional invasive species coordinators and facilitates activities undertaken in coordination with public and private partners. In addition, the AIS Program provides funding for the Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force, a multiagency task force chaired by FWS and NOAA that implements a national program to address aquatic invasive species.61 The Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force was established through the Nonindigenous Aquatic Nuisance Prevention and Control Act. In addition, the AIS Program assists in the evaluation and listing of injurious wildlife under the Lacey Act (see "Law Enforcement" for more information on the Lacey Act) and in the development and implementation of integrated natural resources management plans for military installations under the Sikes Act.62

Congress has regularly addressed issues related to the funding and administration of national fish hatchery programs and the implementation of fish habitat conservation activities. In addition, Members of Congress have frequently addressed questions pertaining to interagency cooperative efforts, including those led or contributed to by FWS, to address habitat conservation and invasive species, including zebra and quagga mussels. In particular, questions related to how to address existing invasions and prevent future invasions may be important to Congress.

Endangered and Protected Species

The Secretaries of the Interior and Commerce are primarily responsible for implementing and enforcing the Endangered Species Act (ESA), which provides for the protection and recovery of threatened and endangered species and their habitats.63 This responsibility generally is delegated to FWS for the Secretary of the Interior and to NOAA Fisheries for the Secretary of Commerce. FWS is responsible for terrestrial and freshwater species; NOAA Fisheries is responsible for marine species.64 NOAA Fisheries also has jurisdiction for most anadromous species—species that are born in freshwater, migrate to the ocean to mature, and return to freshwater to reproduce—such as some salmon, river herring, and sturgeon species. NOAA Fisheries and FWS are jointly responsible for the management of some species, such as Atlantic salmon. Catadromous species—species that spend most of their lives in freshwater but reproduce in marine waters (e.g., some American eels)—are under FWS jurisdiction, though no catadromous species are currently listed under ESA.

ESA provides a comprehensive legal framework for the protection and recovery of threatened and endangered species. FWS conducts and administers multiple activities under ESA, including

- species conservation, listing, and delisting;

- critical habitat identification;

- development and implementation of recovery plans for listed species;

- federal consultations on projects that may impact listed species;

- coordination with nonfederal stakeholders on activities that may impact listed species, including the development of habitat conservation plans;

- grants for species conservation on nonfederal lands (i.e., Cooperative Endangered Species Conservation Grants);

- cooperation with tribes and other partners for species conservation;

- implementation of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES); and

- other species conservation activities.65

One of the primary—and, according to some stakeholders, most contentious—responsibilities that FWS undertakes pursuant to ESA is identifying and listing species of plants and animals as either endangered or threatened, depending on the species' risk of extinction.66 Once a species is added to the federal list of endangered and threatened species, it can receive protection under ESA. During the listing process, FWS also must determine if there are any critical habitat areas for a species. Once a species is listed, FWS develops a recovery plan for the species, and legal tools are available to aid the species' recovery and protect its habitat. One of the best-known tools is the prohibition of unpermitted take (e.g., killing, capturing, or harming) of endangered and threatened species. ESA also requires that federal agencies consult with the Secretary responsible for implementing ESA, usually the Secretary of the Interior or Commerce (depending on the species), to ensure federal actions do not jeopardize listed species.67 In addition, ESA provides for permitting authority related to incidental take of listed species and the import and export of wildlife.68 Other ESA activities are broad-reaching and include providing financial assistance, coordinating conservation efforts with landowners, and forming partnerships with nonfederal stakeholders to protect and recover listed species.69

In addition to listing and protecting species, ESA is the implementing legislation for CITES.70 The Secretary of the Interior is designated as the management and scientific authority to implement CITES, and this authority is statutorily designated to FWS.71 Similar to ESA, CITES divides listed species into groups according to their risk of extinction. However, CITES uses three categories, known as Appendix I, II, and III, which range from most threatened to least threatened. CITES focuses exclusively on the regulation of trade and does not consider or attempt to control habitat loss. Under ESA, a violation of CITES is considered a violation of U.S. law if the violation is committed within U.S. jurisdiction.72

Similar to ESA, the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) is administered jointly by the Secretaries of the Interior and Commerce, as delegated to FWS and NOAA Fisheries.73 MMPA makes it illegal to harass, hunt, capture, or kill a marine mammal in U.S. waters or by U.S. citizens outside of U.S. waters. MMPA defines marine mammal as

any mammal which (A) is morphologically adapted to the marine environment (including sea otters and members of the orders Sirenia [sea cows], Pinnipedia [seals, sea lions, and walruses] and Cetacea [dolphins, porpoises, and whales]), or (B) primarily inhabits the marine environment (such as the polar bear); and, for the purposes of this chapter, includes any part of any such marine mammal, including its raw, dressed, or dyed fur or skin.74

The Secretary of the Interior, delegated to FWS, is responsible for the implementation of MMPA for marine mammals other than "members of the order Cetacea and members, other than walruses, of the order Pinnipedia," which are under the jurisdiction of the Secretary of Commerce, delegated to NOAA.75 FWS has jurisdiction over polar bears, sea otters, walruses, manatees, and dugongs. MMPA also prohibits the import and export of marine mammals and marine mammal products in the United States. These prohibitions are subject to limited exemptions, including for subsistence or traditional uses by selected Alaska Native groups. Several marine mammals protected by MMPA also are listed under ESA or CITES.

Administration and funding related to endangered and otherwise protected species is of perennial interest to Congress. Issues include how species are listed and delisted, the permitting process, requirements for consultation, regulations surrounding exporting wildlife, and the importation of trophies from international hunting activities. In addition, both Congress and various Administrations have discussed the divided jurisdiction between FWS and NOAA Fisheries for implementing ESA and MMPA, which has led to consideration of shifting jurisdiction over protected species programs and moving NOAA Fisheries into FWS (see "Further Reorganization").

Migratory Birds

The Migratory Bird Program at FWS is tasked with protecting, conserving, and restoring migratory bird populations and their habitat for the benefit of the American people.76 The program is responsible for the conservation of more than 1,000 species and their habitats.77 FWS works in cooperation with federal, state, local, tribal, and nongovernmental partners to achieve the program's objectives.

The Migratory Bird Program is tasked with several responsibilities, including bird population monitoring, habitat conservation, permits and regulations, consultation, and recreation.78

Bird populations and their habitats are protected through a large number of statutes and international treaties, which have been enacted and ratified over more than a century.79 These include species-specific statutes (e.g., Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act80), general conservation statutes (e.g., Migratory Bird Treaty Act [MBTA]81), and broader wildlife-related statutes (e.g., ESA and Lacey Act). Some statutes, such as the MBTA, which reflects multiple bipartite agreements between the United States and other countries, also serve as implementing legislation for international treaties.

Similar to statutes aimed at protecting specific or multiple migratory bird species, habitat protection statutes related to migratory birds protect both domestic (e.g., North American Wetlands Conservation Act [NAWCA] and Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp Act [commonly known as the Duck Stamp Act]82) and international bird habitats (e.g., NAWCA and Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Act83). Habitat protection statutes generate revenues and allocate funds to be used for the acquisition and conservation of migratory bird habitats. For example, the Duck Stamp Act generates revenue through the sale of federal waterfowl hunting stamps, which are required for waterfowl hunters 16 years of age and older.84 These revenues are deposited into the Migratory Bird Conservation Fund and used to acquire property interests for waterfowl habitat.85 Certain international treaties also provide for habitat protection, such as the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitats (also known as the RAMSAR Convention), which was ratified by the Senate in 1986.86

The Migratory Bird Program carries out several actions related to promulgating regulations, providing educational resources, and administering grant programs. For example, FWS annually promulgates rules pertaining to the hunting of migratory birds, as authorized by the MBTA, that establish the framework (e.g., the eligible opening and closing dates) for migratory bird hunting seasons for states and tribes.87 States are then allowed to determine their hunting seasons and bag limits within the federal framework. Other regulations pertain to permitting activities that fall under the oversight of either the MBTA or the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, such as incidental take and depredation permits as well as scientific research and falconry. Depredation permits allow for the regulated take of species protected under migratory bird statutes, for example "to reduce damage caused by birds or to protect other interest such as human health and safety or personal property."88 The environmental impact and issuance of depredation permits may be contentious among some stakeholders. Additionally, FWS allows stakeholders to take specific species, without requiring an individual depredation permit, through the issuance of a depredation order that is subject to specific restrictions and conditions.89

The Migratory Bird Program participates in several educational programs to develop "an understanding of and an appreciation for wildlife and nature."90 The program provides several educational activities and resources to connect youth, parents, educators, and others with migratory bird conservation. These activities include the Junior Duck Stamp Conservation and Design Program, International Migratory Bird Day, and the Shorebird Sister Schools Program.91 The education program also provides resources for bird identification and for people interested in bird watching.

A significant component of the Migratory Bird Program is administering grant programs for bird habitat conservation. In particular, NAWCA, the Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Act,92 and the Urban Conservation Treaty for Migratory Birds provide resources, including grant funding, to conserve migratory birds and their habitats.93 These programs support partnerships to conduct habitat restoration projects both domestically and internationally across the Western Hemisphere. Further, by requiring matching funds, these programs seek to leverage federal funds for conservation activities.

Several issues related to migratory birds are of general interest to Congress. For example, Congress may be interested in how hunting regulations are established for migratory birds, the extent of migratory bird habitats that are acquired, and the permitting process for the incidental take of species protected by migratory bird statutes.

International Conservation

The International Affairs program at FWS "coordinates domestic and international efforts to protect, restore, and enhance the world's diverse wildlife and their habitats with a focus on species of international concern."94 The program has multiple responsibilities, including administering grant programs, providing technical assistance to wildlife managers in other countries, and helping to conserve foreign and domestic species through the regulation of international trade and wildlife trafficking.

The International Affairs program derives its authorities through multiple statutes and international agreements.95 Authorizing statutes, treaties, and agreements take many forms and can focus on wildlife and habitat conservation, individual species, or species groups. Although several of these laws and treaties overlap with other functions of FWS—such as the MBTA, migratory bird bilateral treaties and conventions, CITES, and ESA—others focus on international conservation efforts for specific species or groups of species. For example, the International Affairs program administers funds associated with the African Elephant Conservation Act,96 Rhinoceros and Tiger Conservation Act,97 Asian Elephant Conservation Act,98 Great Ape Conservation Act,99 and Marine Turtle Conservation Act.100

To conserve these species, FWS partners with and supports a wide array of international partners, including foreign state, educational, nonprofit, and multinational organizations. Each species conservation act is associated with a fund to protect that species or species group, which supports international grants for conservation efforts. These funds typically are provided for in annual discretionary appropriations.

Although the import of trophies and illegal wildlife trade generally falls under ESA, the Lacey Act, and related statutes, international conservation statutes also can be a mechanism for implementing trade restrictions on certain products (e.g., ivory from African elephants under the African Elephant Conservation Act).101 As such, Congress may consider international conservation efforts as both mechanisms to promote and fund conservation activities and as ways to address the importation of foreign wildlife products. In addition, the reauthorization of existing international conservation statutes is a common issue of interest for Congress.

Law Enforcement

FWS is responsible for enforcing fish and wildlife conservation laws across the country.102 FWS law enforcement has a long history dating back to FWS's predecessor agency, the Division of Biological Survey (see "Agencies Preceding the Fish and Wildlife Service," above). In 1900, Congress enacted the Lacey Act, and the Division of Biological Survey was tasked with enforcing it.103 The Lacey Act, as amended, "prohibits the importation, exportation, transportation, sale, or purchase of fish, wildlife, or plants taken or possessed in violation of federal, state, tribal, or foreign laws."104 Since being tasked with enforcing the Lacey Act, FWS's law enforcement mission has expanded to include

- investigating wildlife crime, habitat destruction, and environmental contamination;

- combating invasive species;

- regulating wildlife trade, shipment, importation, and exportation;

- enforcing federal hunting regulations;

- protecting endangered species and their critical habitat; and

- educating the public about federal wildlife and conservation laws.

FWS's law enforcement authority is derived from a number of federal wildlife statutes and from the implementation of selected international treaties.105 (Many of these laws are discussed in other sections of this report, including NWRSAA, Lacey Act, ESA, MMPA, MBTA, Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act, and several of the international conservation agreements.)

The Office of Law Enforcement operates at the national, regional, and field levels. The national office provides "oversight, support, policy, and guidance."106 At the regional and field levels, where most personnel are located, special agents and wildlife inspectors execute on-the-ground law investigations and wildlife inspection. Special agents carry out investigations of wildlife trafficking to disrupt illegal trade and dismantle smuggling networks, among other responsibilities.107 Wildlife inspectors oversee wildlife transiting through U.S. ports. In addition, they are tasked with processing shipments to identify and intercept illegal wildlife in trade before it enters the country or continues in transit.

The Office of Law Enforcement is distinct from the Refuge Law Enforcement program. Funding for both programs is included under the same appropriation account within the FWS budget, Resource Management, but through different activities (see "Discretionary Appropriations" within "U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Appropriations," below).108

Ensuring that conservation laws are implemented effectively is a perennial issue of interest to Congress. To do so, Congress considers not only questions pertaining to funding the FWS Law Enforcement but also questions of introducing new or amending existing environmental statutes that would modify the responsibilities of law enforcement personnel. For example, these modifications might include altering responsibilities for special agents in the field or wildlife inspectors in ports of entry. Many of the issues of interest to Congress in other programs (such as protected species or international conservation) have the potential to impact the FWS Law Enforcement program.

Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Grant Programs

The Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration program "works with states, insular areas and the District of Columbia to conserve, protect, and enhance fish, wildlife, their habitats, and the hunting, sport fishing and recreational boating opportunities they provide."109 The program is responsible for administering and disbursing funds associated with multiple grant programs that support wildlife and sport fish restoration, as well as hunting- and boating-related activities. Grants are available for states, territories, tribes, and DC, though eligibility differs by grant type. Authority for several FWS-administered grant programs is provided in two statutes, the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act of 1937 (commonly known as the Pittman-Robertson Act) and the Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration Act of 1950 (commonly known as the Dingell-Johnson Act).110 Authority for the State and Tribal Wildlife grant program is routinely provided through annual appropriations legislation.

Pittman-Robertson and Dingell-Johnson are supported through revenues generated by excise taxes on hunting- and fishing-associated equipment, respectively.111 These programs are premised on a user-pay, user-benefit model, in which taxes on hunting equipment support hunting-related activities and wildlife restoration and taxes on fishing and related equipment support boating-related activities and sport fish restoration. Revenues generated from these taxes are deposited into trust funds administered by the Department of the Treasury and used to provide for mandatory appropriations to support the respective grant programs. Funding is allocated to states and territories (and, in the case of Dingell-Johnson, to Washington, DC) according to program-apportionment formulas.

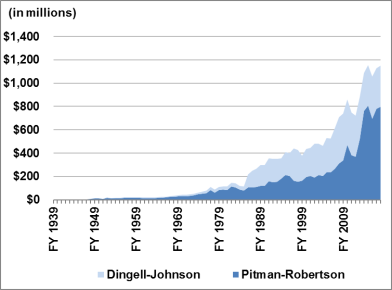

Pittman-Robertson provides funding for wildlife restoration and hunter education and safety programs. Dingell-Johnson provides funding for sport fish restoration and other activities. Sport fish restoration accounts for approximately 58% of funding from the Dingell-Johnson fund (excluding administration and multistate grants); the remaining 42% supports boating access and infrastructure, aquatic education, and coastal and wetland conservation, among other uses.112 Both acts provide funding for administration and multistate conservation grant programs. Since their enactment, Pittman-Robertson and Dingell-Johnson have provided nearly $21 billion dollars in financial assistance for states, territories, and DC for wildlife restoration, hunter safety and education, and sport fish restoration, not including other Dingell-Johnson uses (see Figure 5).113 From FY2014 through FY2018, these programs were provided a combined total of more than $1 billion annually, on average, for wildlife and sport fish restoration and hunter education.

|

Figure 5. Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration (Pittman-Robertson) and Sport Fish Restoration (Dingell-Johnson) Funding, FY1939-FY2018 (in nominal dollars) |

|

|

Sources: CRS, with data from FWS, "Wildlife Restoration Program – Funding: 1939 Through 2018 WR Apportionments (includes Hunter Ed)," at https://wsfrprograms.fws.gov/Subpages/GrantPrograms/WR/WRApportionmentsHE-1939-2018.xlsx, and FWS, "Sport Fish Restoration Program – Funding: 1952 Through 2018 SFR Apportionments, at https://wsfrprograms.fws.gov/Subpages/GrantPrograms/SFR/SFRApportionments-1952-2018.xlsx. Notes: Funding for the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act of 1937 (16 U.S.C. §§669 et seq., also known as the Pittman-Robertson Act) includes disbursements for wildlife restoration and hunter education programs pursuant to 16 U.S.C. §§669c, 669g-1, and 669h-1. Funding for the Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration Act of 1950 (16 U.S.C. §§777 et seq., commonly known as the Dingell-Johnson Act) includes only disbursements for the Sport Fish Restoration program, which under current law accounts for 58.012% of Dingell-Johnson funding, excluding the funding set aside for administration and multistate grants pursuant to 16 U.S.C. §§777c and 777k. |

State and Tribal Wildlife grants are used to support state fish and wildlife agencies and tribal governments in developing and implementing plans and programs that benefit wildlife and its habitat. Historically, state assistance has been disbursed in two parts, one based on a formula and one based on a competitive grant process. Tribal grants are awarded based on an application process, which is open to federally recognized tribes.

Congress routinely considers issues related to wildlife and sport fish restoration grants. Members of Congress regularly introduce legislation to amend Pittman-Robertson and Dingell-Johnson, including bills that would alter what types of activities are funded, the allocation of funding, and the sources of funding.114 Additionally, Congress annually considers funding levels for the State and Tribal Wildlife grants, and the Trump Administration has proposed to eliminate funding for competitive State and Tribal Wildlife grants.

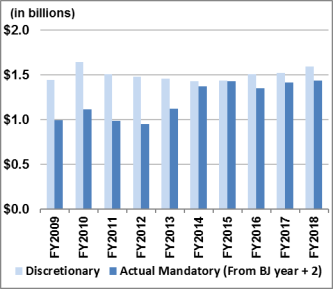

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Appropriations

FWS is funded through both discretionary and mandatory appropriations, which are provided on an annual basis. Discretionary funding is used to support many of the agency's essential functions, and mandatory funding supports selected activities specified in previously enacted statutes, including a significant portion of FWS's financial assistance activities. Both discretionary and mandatory appropriations have fluctuated over time (Figure 6). From FY2009 through FY2018, FWS discretionary appropriations totaled $1.5 billion annually, on average; over the same period, mandatory appropriations amounted to $1.2 billion annually, on average. Whereas discretionary appropriations have for the most part remained flat over the past 10 years, mandatory appropriations for FWS have generally increased.

|

Figure 6. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Discretionary and Mandatory Appropriations, FY2009-FY2018 (in nominal dollars) |

|

|

Sources: CRS, with data from FWS budget justifications for FY2011-FY2019 and P.L. 111-8, P.L. 111-88, P.L. 112-10, P.L. 112-74, P.L. 113-6, P.L. 113-76, P.L. 113-235, P.L. 114-113, P.L. 115-31, and P.L. 115-141. Mandatory appropriations based on mandatory appropriations reported in budget justification for fiscal year plus two years (e.g., for FY2017, mandatory appropriations information is from FY2019 budget justification), except for FY2018, which is from the FY2019 budget justification. Notes: Appropriations do not include supplementary appropriations. See Table 1 for more information on supplemental funding. |

Discretionary Appropriations

Congress generally funds FWS in annual appropriations laws for the Department of the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies. In some years, funding for DOI agencies, including FWS, is provided through either continuing resolutions or omnibus/consolidated appropriations acts. Discretionary appropriations for FWS are provided to carry out many of the essential functions related to the agency's mission, namely the conservation; protection; and enhancement of fish, wildlife, and plants and their habitats. This aim is accomplished through various activities: resource management, construction projects, land acquisition, international conservation, and payments and grants to states and other parties.

During the appropriations process, Congress faces several perennial issues, including the overall level of discretionary funding, its distribution across agency programs, and consideration of an Administration's proposals to eliminate or change levels of funding for some functions. Congress also routinely considers FWS policy issues, such as those discussed in the "U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Programs" section above.

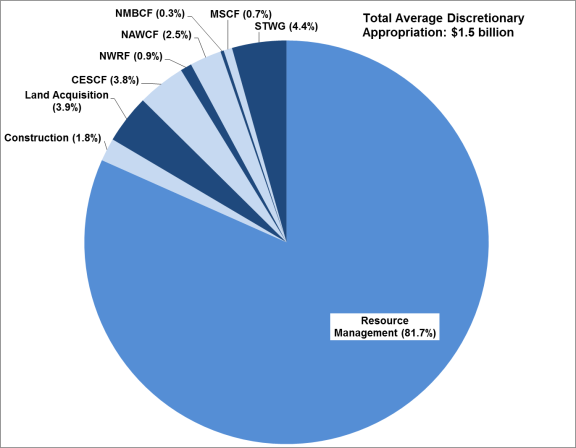

From FY2009 through FY2018, FWS discretionary funding has averaged $1.5 billion, allocated across nine appropriations accounts (Figure 7).115 During this time period, the majority of FWS discretionary funding (81.67%) has been provided to the Resource Management account, which provides funding for several activities, including

- Ecological Services, which includes activities related to FWS's role in ESA implementation;

- Habitat Conservation;

- National Wildlife Refuge System;

- Conservation and Law Enforcement;

- Fish and Aquatic Conservation;

- Cooperative Landscape Conservation;

- Science Support; and

- General Operations.

The remaining 18.33% has been allocated across eight appropriations accounts, each receiving between 0.27% and 4.35% of the total appropriation, on average (Figure 7). The remaining accounts include

- Construction (1.84%);

- Land Acquisition (3.91%);

- Cooperative Endangered Species Conservation Fund (3.84%);

- National Wildlife Refuge Fund (0.91%);

- North American Wetlands Conservation Fund (2.53%);

- Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Fund (0.27%);

- Multinational Species Conservation Fund (0.68%); and

- State and Tribal Wildlife Grants (4.35%).

The Construction account funds engineering design and construction throughout FWS facilities and infrastructure through three activities: Line Item Construction Projects, Bridge and Dam Safety Programs, and Nationwide Engineering Services. Funding for the Land Acquisition account generally is derived from the Land and Water Conservation Fund and is used to acquire land for recreation and conservation purposes.116 The remaining six accounts fund conservation activities and payments to states and tribes for conservation and in-lieu-of tax reasons. These programs support grant, financial, and technical assistance programs to states, international partners, tribes, and other stakeholders.

|

Figure 7. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Discretionary Appropriations by Account, Average FY2009-FY2018 |

|

|

Sources: CRS, with data from P.L. 111-8, P.L. 111-88, P.L. 112-10, P.L. 112-74, P.L. 113-6, P.L. 113-76, P.L. 113-235, P.L. 114-113, P.L. 115-31, and P.L. 115-141. Notes: CESCF = Cooperative Endangered Species Conservation Fund; NWRF = National Wildlife Refuge Fund; NAWCF = North American Wetlands Conservation Fund; NMBCF = Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Fund; MSCF = Multinational Species Conservation Fund; STWG = State and Tribal Wildlife Grants. Rescissions in FY2009 ($0.50 million) and FY2011 ($4.94 million) are not included. |

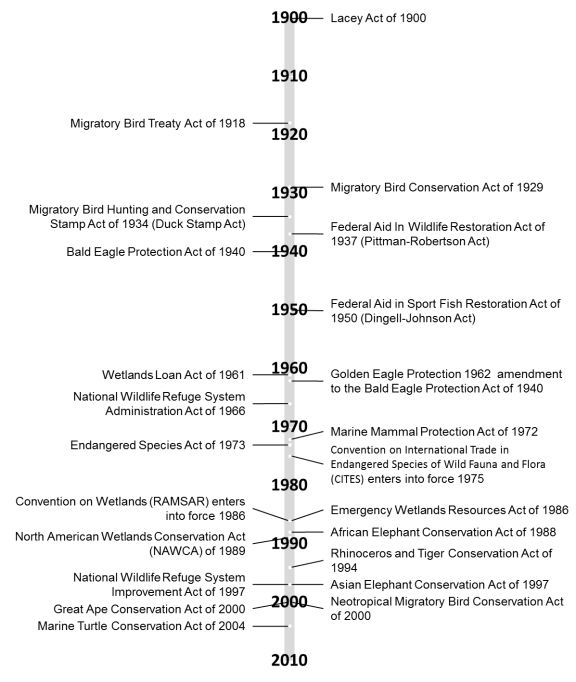

Mandatory Appropriations

From FY2009 through FY2018, FWS received $1.2 billion on average, annually, in mandatory (also called permanent) appropriations. Mandatory appropriations have ranged from 39% (FY2012) to 50% (FY2015) of the total FWS budget (Figure 6) in recent years. FWS mandatory appropriations fund land acquisition for migratory bird habitat conservation, financial assistance to the states and territories for fish and wildlife conservation and related activities, and other purposes. From FY2009 through FY2018, each account received between 0.36% and 50.51% of total mandatory appropriations, on average (Figure 8). FWS mandatory appropriations are spread across several accounts:

- Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration (50.51%);

- Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration (36.57%);

- Cooperative Endangered Species Conservation Fund (5.30%);

- Migratory Bird Conservation (5.09%);

- North American Wetlands Conservation Fund (0.73%);

- National Wildlife Refuge Fund (0.64%);

- Federal Lands Recreational Enhancement Act funds (0.44%);

- contributed funds (0.37%); and

- other miscellaneous permanent appropriations (0.36%).

The majority of FWS mandatory appropriations are included in two accounts, the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration (also known as the Pittman-Robertson) account and the Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration (also known as Dingell-Johnson) account (for more information on these activities, see "Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration" section, above). Both of these accounts are funded through excise taxes on various sporting goods related to hunting and fishing. Receipts for these taxes are collected annually and deposited into trust funds for each program. Disbursements from the funds are then allocated to states and territories (and Washington, DC, in the case of Dingell-Johnson) in the year following their collection.

Funding for the Migratory Bird Conservation account is derived from the sale of federal duck stamps pursuant to the Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp Act, commonly known as the Duck Stamp Act (see "Migratory Birds" section, above) and an import duty on arms and ammunition implemented by the Emergency Wetlands Resource Act of 1986.117 Funds in the Migratory Bird Conservation Fund support the acquisition of interests, either through title or easement, of wetlands and upland habitat for the conservation of migratory birds.

The Cooperative Endangered Species Conservation Fund is supported through both discretionary and mandatory appropriations. The fund, established by Section 6 of ESA,118 supports grants for states and territories to conduct species and habitat conservation activities on nonfederal lands. Funding for the Cooperative Endangered Species Conservation Fund is derived from 5% of the total amounts deposited into the Pittman-Robertson and Dingell-Johnson accounts.119 In addition, any balance in excess of $500,000 dollars derived from amounts collected on fines, penalties, or property forfeiture for ESA and Lacey Act violations is to be transferred to the Cooperative Endangered Species Conservation Fund.120

Mandatory appropriations for the North American Wetlands Conservation Fund are derived from multiple sources, including interest on the Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration account and fines related to violations of the Migratory Bird Conservation Treaty Act.121 In addition, the Coastal Wetlands Planning, Protection and Restoration Act provides funding from the Dingell-Johnson Sport Fish Restoration account to complete NAWCA-authorized projects in coastal states.122 NAWCA mandatory funds supplement NAWCA discretionary funds to support cooperative efforts to protect, enhance, and restore habitat for wetland species. These funds support domestic programs and conservation efforts in Canada and Mexico (see "Migratory Birds" section, above).

Supplemental Appropriations

From FY2009 through FY2018, FWS has received supplemental appropriations outside the annual discretionary and mandatory appropriations cycle on three occasions: in 2009, 2013, and 2018 (see Table 1). Each of these three acts is discussed in more detail below.

Table 1. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Supplemental Appropriations, FY2009-FY2018

(in millions of nominal dollars)

|

Appropriations Account |

||||||||

|

Resource Management |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Construction |

|

|

|

|||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

Source: CRS, with data from the referenced public laws.

Notes: Totals do not include adjustments pursuant to the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act, as amended (2 U.S.C. §901a).

a. Total includes funding appropriated directly to FWS. Funding also was appropriated to the Department of the Interior Office of the Secretary, part of which was allocated to FWS.

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009

On February 17, 2009, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 was enacted.123 Through the act, FWS received an additional $280 million divided between the Resource Management and Construction appropriations accounts.

The Resource Management account received $165 million for "deferred maintenance, construction, and capital improvements on national wildlife refuges and national fish hatcheries and for high priority habitat restoration projects."124

The Construction account received $115 million for "construction, reconstruction, and repair of roads, bridges, property, and facilities and for energy efficient retrofits of existing facilities."125

Funding from the act was used to facilitate capital improvements, deferred maintenance, habitat restoration, visitor center construction, facility repair, and energy efficiency projects. The service prioritized projects that could be completed in the shortest amount of time, generate the most jobs, and create lasting value for the American people.126

Disaster Relief Appropriations Act of 2013

In response to damages resulting from Hurricane Sandy, the Disaster Relief Appropriations Act of 2013 was enacted on January 29, 2013.127 Through this act, the FWS's Construction account received $68.2 million for "necessary expenses related to the consequences of Hurricane Sandy."128 In addition to funds appropriated directly to FWS, DOI's Office of the Secretary was appropriated $360 million for Departmental Operations.129 In total, including both directly appropriated funds and funds provided through the DOI appropriation, FWS received $167 million for Hurricane Sandy recovery.130 This funding supported projects such as direct recovery actions (e.g., beach and shoreline recovery and refuge and hatchery rebuilding) and resilience and preparedness activities (e.g., dam removal, shoreline modification, and modernization of the Coastal Barrier Resource System maps).131

Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018

Congress included supplemental funding for FWS for damages associated with Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria under Division B of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018.132 Pursuant to the act, $210.6 million was appropriated to the FWS Construction account for "necessary expenses related" to the hurricanes.133

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

The joint resolution providing the authority for the Fish Commission (No. 22, 16 Stat. 593) created the job of the Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries and instructed that this position be held by an existing government employee with no additional salary. The first commissioner appointed to this position was Spencer Fullerton Baird, an employee of the Smithsonian Institution. |

| 2. |

The integration occurred as part of the Department of Commerce Act, which was enacted on February 14, 1903 (C. 552, 32 Stat. 825). |

| 3. |

Prior to the passage of the Department of Commerce Act in 1903, the Secretary of the Treasury was tasked with regulating the fur industry (C. 273 §6, 15 Stat. 241) and the salmon industry (C. 415, 25 Stat. 1009) within Alaska. Upon passage of the Department of Commerce Act, these responsibilities were transferred to the Department of Commerce and Labor, where they eventually were tasked to the Bureau of Fisheries. Additional authorities to regulate the Alaska salmon fisheries were provided in C. 3547, 34 Stat. 478. |

| 4. |

C. 141, 37 Stat. 736, An Act to Create the Department of Labor, March 4, 1913. |

| 5. |

C. 801, 46 Stat. 845, An Act to Amend the Act Entitled "An Act to Regulate the Interstate Transportation of Black Bass, and for Other Purposes," July 2, 1930; C. 251, 49 Stat. 1246, the Whaling Treaty Act, May 1, 1936; C. 272, 43 Stat. 464, An Act for the Protection of the Fisheries of Alaska, and for Other Purposes, June 6, 1924. |

| 6. |

The Section of Economic Ornithology, which was sometimes referred to as an office or a branch, was first led by C. Hart Merriam. |

| 7. |

These responsibilities were outlined in the bill providing for the U.S. Department of Agriculture's (USDA's) appropriations for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1886. The appropriations provided funding for the establishment of what became the Section of Economic Ornithology (C. 338, 23 Stat. 354). |

| 8. |

The elevation to a stand-alone division and expansion to include mammals were included within USDA's appropriations bill for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1987 (C. 575, 24 Stat. 101). |

| 9. |

For example, see USDA's appropriations bill for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1891 (C. 707, 26 Stat. 285), which states that the Division of Economic Ornithology and Mammalogy is responsible for "investigating the geographic distribution of animals and plants, and for the promotion of economic ornithology and mammalogy, and investigation of the food-habit of North American birds and mammals in relation to agriculture, horticulture, and forestry." |

| 10. |

As with the establishment of the Division of Economic Ornithology and Mammalogy, the renaming of the division as the Division of Biological Survey occurred through USDA's appropriations bill for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1897 (C. 140, 29 Stat. 100). |

| 11. |

The elevation to a bureau occurred as part of USDA's appropriations bill for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1906 (C. 1405, 33 Stat. 877). |

| 12. |

Reorganization Plan Number II of 1939 was submitted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to Congress on May 9, 1939. The plan was approved by Congress on June 7, 1939, with an effective date of July 1, 1939 (C. 193, 53 Stat. 813). |

| 13. |

Reorganization Plan Number II of 1939, 5 U.S.C Appendix—Reorganization Plans. |

| 14. |

Reorganization Plan Number II of 1939. |

| 15. |

Reorganization Plan Number III of 1940, 5 U.S.C Appendix—Reorganization Plans. |

| 16. |

Reorganization Plan Number III of 1940 was submitted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to Congress on April 2, 1940. The plan was approved by Congress on June 4, 1940, with an effective date of June 30, 1940 (C. 236, 54 Stat. 231). |

| 17. |

Reorganization Plan Number III of 1940, Message of the President. |

| 18. |

Fish and Wildlife Act of 1956, P.L. 1024. |

| 19. |

P.L. 1024, §3 (C. 1036 §3, 70 Stat. 1120). |

| 20. |

P.L. 1024, §3 (C. 1036 §3, 70 Stat. 1120). |

| 21. |

P.L. 1024, §2 (C. 1036 §2, 70 Stat. 1119). |