Hunting and Fishing on Federal Lands and Waters: Overview and Issues for Congress

This report provides an overview of issues related to hunting and fishing on federal lands. Each year millions of individuals participate in hunting and fishing activities, bringing in billions of dollars for regional and national economies. Due to their popularity, economic value, constituent appeal, and nexus to federal land management issues, hunting and fishing issues are perennially addressed by Congress. Congress addresses these issues through oversight, legislation, and appropriations, which target issues such as access to federal lands and waters for sportsperson activities, and striking the right balance among hunting and fishing and other recreational, commercial, scientific, and conservation uses.

Most federal lands and waters are open to hunting and/or fishing; stakeholders contend that these areas provide many hunters and anglers with their only or best access to hunting and fishing. This is especially the case in the western United States. Federal lands and waters account for nearly 640 million acres (28%) of the 2.3 billion acres in the United States. Federal land management agencies manage recreational activities, including hunting and fishing, on federal lands. Four land management agencies—the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and National Park Service (NPS) within the Department of the Interior (DOI), and the U.S. Forest Service (FS) within the Department of Agriculture (USDA)—manage over 95% of federal lands, while the rest is administered by other agencies within DOI, the Department of Defense (DOD), the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), and others.

Federal land management agencies have hunting and fishing policies that are derived from statutes establishing the agencies as well as federal and state laws pertaining to hunting and fishing. In general, federal land management agencies have hunting and fishing policies that are either open unless closed or closed unless open, depending on the mission of the agency. In the case of the former, the default status of lands is open to hunting and fishing unless closed by the relevant agency. For these agencies, recreation, including hunting and fishing, is often included within the mission of the agency. For lands that are closed unless open, hunting and fishing are often a secondary use and allowed only when compatible with the primary purpose or mission of the agency or the federal land unit. Overall, based on CRS analysis of agency data, more than 80% of federal lands and waters appear to be open to hunting in some capacity.

Several federal statutes are applicable to hunting and fishing either directly or indirectly. For example, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 provides the federal government with the authority to regulate the hunting of migratory birds in the United States. Similarly, the Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp Act (better known as the Duck Stamp Act) authorizes the requirement for hunters to obtain a federal stamp to hunt migratory birds. Alternatively, federal laws may indirectly relate to hunting and fishing, such as the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act (also known as the Pittman-Robertson Act), which directs tax revenues from certain hunting and fishing equipment to states for wildlife restoration and hunter education.

In the 115th Congress, hunting and fishing issues have been addressed through oversight and proposed legislation. These bills (e.g., H.R. 3668 and H.R. 4489, and S. 733 and S. 1460) reflect some of the key issues being deliberated by Congress. These issues include access to federal lands for hunting and fishing, procedures for closing certain lands to these activities, the transport of firearms on federal lands, and the use of specific ammunition and tackle in hunting and fishing. Although there is general agreement among Members of Congress regarding the importance of balancing sportsperson activities and other activities on federal lands, the question of what the appropriate balance is, and the best means of achieving it, has in some cases been contentious.

Hunting and Fishing on Federal Lands and Waters: Overview and Issues for Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Hunting and Fishing Activities: Background and Statistics

- Hunting and Fishing on Federal Lands

- Bureau of Land Management

- Forest Service

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- National Park Service

- Bureau of Reclamation

- Department of Defense

- U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

- Federal Statutes Related to Hunting, Fishing, and Recreational Shooting

- Migratory Bird Treaty Act

- Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp Act

- Endangered Species Act

- Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act and Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration Act

- Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act

- Laws Related to International Hunting and Fishing

- Selected Administrative Actions on Hunting and Fishing

- E.O. 13433

- Department of the Interior Secretarial Orders in the 115th Congress

- Issues for Congress

- Access to Federal Lands and Waters

- Reauthorizations

- Regulation of Ammunition and Tackle

Figures

Tables

Summary

This report provides an overview of issues related to hunting and fishing on federal lands. Each year millions of individuals participate in hunting and fishing activities, bringing in billions of dollars for regional and national economies. Due to their popularity, economic value, constituent appeal, and nexus to federal land management issues, hunting and fishing issues are perennially addressed by Congress. Congress addresses these issues through oversight, legislation, and appropriations, which target issues such as access to federal lands and waters for sportsperson activities, and striking the right balance among hunting and fishing and other recreational, commercial, scientific, and conservation uses.

Most federal lands and waters are open to hunting and/or fishing; stakeholders contend that these areas provide many hunters and anglers with their only or best access to hunting and fishing. This is especially the case in the western United States. Federal lands and waters account for nearly 640 million acres (28%) of the 2.3 billion acres in the United States. Federal land management agencies manage recreational activities, including hunting and fishing, on federal lands. Four land management agencies—the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and National Park Service (NPS) within the Department of the Interior (DOI), and the U.S. Forest Service (FS) within the Department of Agriculture (USDA)—manage over 95% of federal lands, while the rest is administered by other agencies within DOI, the Department of Defense (DOD), the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), and others.

Federal land management agencies have hunting and fishing policies that are derived from statutes establishing the agencies as well as federal and state laws pertaining to hunting and fishing. In general, federal land management agencies have hunting and fishing policies that are either open unless closed or closed unless open, depending on the mission of the agency. In the case of the former, the default status of lands is open to hunting and fishing unless closed by the relevant agency. For these agencies, recreation, including hunting and fishing, is often included within the mission of the agency. For lands that are closed unless open, hunting and fishing are often a secondary use and allowed only when compatible with the primary purpose or mission of the agency or the federal land unit. Overall, based on CRS analysis of agency data, more than 80% of federal lands and waters appear to be open to hunting in some capacity.

Several federal statutes are applicable to hunting and fishing either directly or indirectly. For example, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 provides the federal government with the authority to regulate the hunting of migratory birds in the United States. Similarly, the Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp Act (better known as the Duck Stamp Act) authorizes the requirement for hunters to obtain a federal stamp to hunt migratory birds. Alternatively, federal laws may indirectly relate to hunting and fishing, such as the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act (also known as the Pittman-Robertson Act), which directs tax revenues from certain hunting and fishing equipment to states for wildlife restoration and hunter education.

In the 115th Congress, hunting and fishing issues have been addressed through oversight and proposed legislation. These bills (e.g., H.R. 3668 and H.R. 4489, and S. 733 and S. 1460) reflect some of the key issues being deliberated by Congress. These issues include access to federal lands for hunting and fishing, procedures for closing certain lands to these activities, the transport of firearms on federal lands, and the use of specific ammunition and tackle in hunting and fishing. Although there is general agreement among Members of Congress regarding the importance of balancing sportsperson activities and other activities on federal lands, the question of what the appropriate balance is, and the best means of achieving it, has in some cases been contentious.

Introduction

Hunting and fishing, often referred to as sportsmen and sportswomen (sportsperson) activities, on federal lands is a perennial issue for Congress. Members of Congress routinely introduce legislation and debate issues pertaining to recreational opportunities and access, federal land use, and the federal government's regulatory roles related to sportsperson activities. Hunting and fishing are also regularly addressed in the executive branch through executive and secretarial orders and federal rulemakings. These issues cut across all of the federal land management agencies—including Department of the Interior (DOI) agencies and the U.S. Forest Service (FS) in the Department of Agriculture (USDA) and other land management agencies and departments such as the Department of Defense (DOD) and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE).

This report addresses hunting and fishing activities on federal lands. It includes background information on the status of hunting and fishing activities in the United States (including related statistics), as well as major federal statutes that address hunting and fishing. It also discusses administrative actions relating to hunting and fishing and concludes with a section on potential hunting and fishing issues facing Congress, including a discussion of selected legislative proposals. This report focuses on recreational hunting and freshwater fishing activities on federal lands and freshwaters; it generally does not address hunting and fishing activities on state or private property, commercial activities, or ocean/marine recreational fishing. Similarly, although policy debates related to firearms are central to hunting issues, this report does not address in detail issues and legislation pertaining specifically to firearms and firearm-tax-related topics.

Hunting and Fishing Activities: Background and Statistics

Hunting and fishing are considered by many to be traditional American pastimes and are frequently cited as being integral to conservation and wildlife management.1 Sportsperson activities are further put forth as a means to connect participants to the land, promote conservation activities, and generate revenue. Proponents of this view often contend that throughout history, conservation leaders—such as President Theodore Roosevelt or Aldo Leopold—were avid sportspersons and supported land conservation needed for hunting and fishing.2 However, some have raised concerns that conservation interests and sportsperson activities can potentially conflict. For example, some have noted that unless closely regulated using sound science, hunting and fishing can become unsustainable and negatively affect some ecosystems and species.

Identifying an appropriate balance among multiple authorized uses for federal lands is seen by some as a role for Congress. Hunting and fishing activities are included in the management plans for many federally owned areas, and are authorized under law for some federal lands (see "Hunting and Fishing on Federal Lands" section below). The extent to which sportsperson activities should be allowed or prioritized on federal lands is often debated by Congress and stakeholders. Although hunting and fishing occur on federal, state, and private properties, some stakeholders claim that federal lands offer many participants their only or best opportunity to conduct sportsperson activities.3 Proponents of greater access to sportsperson activities on federal lands cite the importance of federal lands for these activities and contend that federal lands should be managed in a way that benefits and provides opportunities for all Americans, including hunters and anglers.4 Others have expressed concerns that prioritizing sportsperson activities can marginalize other users and negatively affect conservation efforts.5

Hunting and fishing are also drivers of local and regional economies and contribute to the multibillion-dollar outdoor economy, which includes other outdoor activities such as wildlife viewing, hiking, and camping. Since 1955, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) has conducted a national survey of hunting, fishing, and wildlife-associated recreation (i.e., wildlife-watching and other related activities) every five years.6 As part of the survey, the FWS estimates both the number of participants taking part in these activities and expenditures arising from them.7

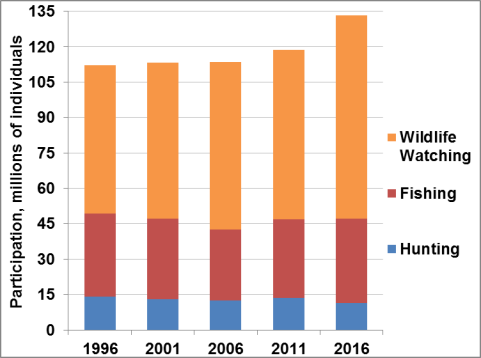

Figure 1 displays data on hunting and fishing participation between 1996 and 2016 as well as wildlife watching over the same period. Between 1996 and 2016, participation in hunting ranged from 11.5 million to 14.0 million sportspersons. Participation in fishing has been similarly variable, with a range between 30.0 million and 35.8 million individuals. For both hunting and fishing, there has not been a consistent trend across the 20-year period. During the same time period, however, participation in wildlife watching was estimated to have increased, from 62.9 million individuals in 1996 to 86.0 million in 2016.

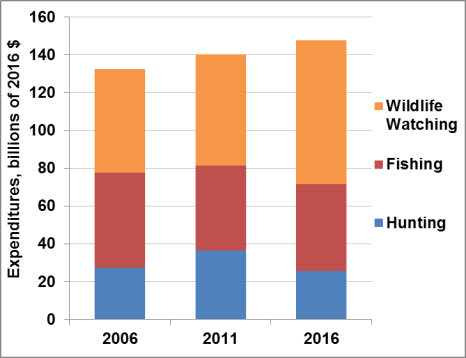

For 2016, FWS found that over 101 million Americans, or approximately 40% of the population, participated in one or more wildlife-related activity, which resulted in an estimated $156 billion in expenditures, or approximately 1% of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP); see Figure 2.8 Within that total, nearly 40 million people were estimated to have participated in hunting and fishing, each spending an average of over $2,000.9 However, the 2016 survey estimated that there were 2.2 million fewer hunters in the United States in 2016 than in 2011, a fact highlighted by DOI in subsequent administrative actions.10 Wildlife watching accounted for 86.0 million participants, who spent an average of $882 per participant.11

Overall, the survey results consistently indicate that a large portion of the U.S. population participates in hunting and fishing activities and that these activities contribute to both local and national economies. Supporters of hunting and fishing point to the wide base of participants in these activities and use these data to support arguments for providing greater access to federal lands and waters for hunting and fishing. Others have highlighted that, in light of the increase in wildlife watching, land management agencies may need to shift management plans to support nonconsumptive wildlife-related activities, such as bird watching. Still others have highlighted the importance of hunting and fishing for conservation and have suggested that wildlife watchers could disturb habitats.

Hunting and Fishing on Federal Lands

Federal lands and waters are a significant provider of opportunities for sportspeople to participate in hunting and fishing. The federal government owns approximately 640 million acres of land, accounting for about 28% of land within the United States.12 In 2011, 36% of hunters (4.9 million of 13.7 million hunters total) used public lands, which include federal lands as well as state, local, and municipal lands, although the percentage of hunters using public lands varied across U.S. regions.13 For example, in the western United States, nearly 1.5 million hunters (71% of hunters in this region) utilized public lands; in the eastern United States, 1.3 million hunters (33% of hunters in this region) used public lands.14 Within the public lands utilized by hunters and anglers, the federal lands and waters are managed by a number of different agencies, including agencies within the DOI and USDA as well as the DOD. However, states maintain ownership over some of the submerged lands (e.g., lakebeds) within some federal land units (e.g., certain national wildlife refuges and Bureau of Land Management [BLM] lands).15 Four agencies—BLM, National Park Service (NPS), and FWS in DOI and FS in USDA—account for roughly 95% of all federal acreage; DOD and USACE manage about 2% each; and the remainder is managed by a variety of other agencies. Each land management agency has its own established mission and purpose, which can lead to different approaches to managing specific activities on lands they oversee.

Policies related to hunting and fishing on federal lands and waters are variable and reflect overall agency missions and the specified unit or installation purposes. For example, although a land management agency may have a policy to allow hunting and fishing, an individual unit within the agency may not allow hunting and fishing in parts of the unit because of a specific purpose or need at the unit level. Furthermore, many federal and state laws can influence how hunting and fishing is regulated in agency units (see "Federal Statutes Related to Hunting, Fishing, and Recreational Shooting" for more information). In particular, states are responsible for managing wildlife within their borders, and hunters and anglers are, almost always, required to have relevant state licenses.16

Hunting and fishing management on federal lands and waters can be roughly divided into two categories based on agency policy. Land can be managed for hunting and fishing as open unless closed (e.g., BLM lands), or, conversely, as closed unless open (e.g., hunting on NPS lands). These two management conditions reflect the default status of the land management agency under its authorities, and whether the responsible agency head is tasked with justifying closing or opening of lands to hunting and fishing. This justification is typically derived as a result of whether these sportsperson activities are deemed compatible or consistent with the mission of the agency and the purpose of an individual unit. Implementation of these laws is outlined in agency policies, service manuals, and the Code of Federal Regulations.

Overall, there appears to be a wide variation in the portion of lands that are open to hunting and fishing. Among open unless closed lands, over 246 million acres (99%) of BLM lands are open to hunting and fishing,17 while the FS reports that 99% of the 193 million acres it administers are open to hunting and at least 99% of FS administered rivers, streams, and lakes are open to fishing.18 Among closed unless opened lands, 374 (66%) of the 566 FWS-administered wildlife refuges offer some form of hunting and/or fishing (hunting is allowed on 336, and fishing is allowed on 277), and 37 of 38 wetland management districts allow hunting and 34 permit fishing.19 In total, FWS administers about 86 million acres that allow hunting.20 Within the National Park System, 70 (17%) of 417 units managed by the NPS are statutorily mandated to allow hunting, and 6 units (1%) are authorized but not mandated to allow it.21 Although it is not possible to determine the precise percentage of federal acres open to hunting and/or fishing, based on these data, more than 80% of federal lands and waters appear to be open to hunting in some capacity.22 The below sections provide an overview of hunting and fishing policy for several of the major land management agencies and departments. Not all agencies managing federal lands and waters are included in this report (e.g., U.S. Postal Service).

Bureau of Land Management

BLM currently administers more acreage of federal lands in the United States than any other federal agency—248 million acres.23 BLM lands are largely (99.4%) located in the 11 contiguous western states and Alaska.24 In general, pursuant to the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA), BLM manages public lands according to multiple use and sustained yield principles.25 FLPMA defines multiple use to be a combination of uses that best meets present and future needs, including recreation, grazing, timber, energy and mineral development, wildlife and fish, conservation, and others.26 Sustained yield is defined as ensuring the land is productive in perpetuity for an output of renewable resources in a manner consistent with multiple use.27 In addition, FLPMA defines principal or major use of BLM lands to include "grazing, fish and wildlife development and utilization, mineral exploration and production, rights-of-way, outdoor recreation, and timber production."28

In line with BLM's guiding principles and the major uses outlined in FLPMA, over 99% of BLM lands are open to hunting and/or fishing pursuant to federal and state laws.29 In the case where states own submerged lands within water resources on BLM lands, BLM generally provides access for fishing, with the exception of certain seasonal closures.30 BLM lands are open to hunting and fishing "unless specifically prohibited."31 BLM is authorized to close or restrict uses of lands under certain circumstances. For instance, BLM has the authority to identify lands and periods that are off limits to hunting and fishing for reasons including public safety, administration, or compliance with law.32 These lands may include areas adjacent to improved areas, like campgrounds. Except in emergencies, BLM regulations related to hunting and fishing require consultation with the state. BLM regulations further guide closures and restrictions of uses on BLM lands. For example, they allow an authorized BLM officer to issue an order to close or restrict the use of designated public lands to protect people, property, public lands, and resources.33

Forest Service

The FS administers the National Forest System (NFS), which consists of 193 million acres of land in the United States, predominantly in the West (145 million acres).34 The NFS also includes 26 million acres in the East and 22 million acres in Alaska. Under the Organic Administration Act of 1897, national forests—then called forest reserves—were originally established to improve and protect federal forests and watersheds and provide a source of timber.35 The Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act of 1960 expanded the uses of the NFS to also include activities related to outdoor recreation, rangeland management, and wildlife and fish management.36 Multiple use and sustained yield as defined by the act have similar definitions to those provided in FLPMA.37 The NFS is to be managed so as to best meet the needs of the American people while ensuring the lands remain highly productive in perpetuity.38

FS, similar to BLM, generally allows hunting and fishing on lands and waters it manages pursuant to state laws and regulations, with some exceptions for certain areas.39 Areas may be off limits to hunting and fishing for reasons such as public safety, administration, fish and wildlife management, or public use and entertainment.40 For example, FS may prohibit some forms of hunting near administrative sites or campgrounds. Some NFS units or management areas have specific statutory directives for hunting and fishing. For instance, P.L. 102-220 established the Greer Spring Special Management Area within the Mark Twain National Forest and directed that the Secretary of Agriculture shall permit hunting and fishing within the special management area.41

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Excluding national monument areas, the FWS administers 89 million acres of federal land within the National Wildlife Refuge System (NWRS) in the United States, of which 77 million acres (87%) are in Alaska.42 The NWRS is composed of national wildlife refuges, which encompass refuge lands, wildlife ranges, wildlife management areas, game preserves and conservation areas, and waterfowl production and coordination areas. At the end of FY2017, the NWRS contained 566 national wildlife refuges.

The FWS has a primary-use mission—to conserve, manage, and, where appropriate, restore plants and animals—pursuant to the National Wildlife Refuge System Administration Act of 1966 (NWRSAA).43 In addition to the NWRS mission, each refuge or system unit is to be managed to fulfill any specific purposes for which the unit was established. Although not included as the primary use of conserving fish and wildlife, compatible wildlife-dependent recreational uses—such as hunting, fishing, bird-watching, hiking, and education, among others—are defined as priority public uses and are to receive priority consideration in planning and management pursuant to NWRSAA.44

Hunting and fishing are allowed in refuge units when determined by the Secretary to be compatible with the system mission and unit purpose.45 However, in contrast to BLM and FS, all uses, including hunting and fishing, are prohibited unless specifically allowed.46 Of the 566 wildlife refuges, 374 offer some form of hunting and/or fishing: Hunting is allowed on 336 and fishing is allowed on 277, pursuant to state and federal regulations.47 In addition, of the 38 wetland management districts in the NWRS, hunting is allowed on 37 and fishing is allowed on 34.48 Although NWRS units may offer hunting and fishing opportunities, specific areas within individual units may still be closed to these activities when they are not compatible with the mission of the system or purpose of the unit or not in the public interest.49

National Park Service

NPS's National Park System contains 417 units with 80.0 million federal acres.50 NPS-managed units have diverse titles—national park, national monument, national preserve, national historic site, national recreation area, national battlefield, and more.51 As established in the National Park Service Organic Act, the NPS has a dual mission "to conserve the scenery, natural and historic objects, and wild life in the System units and to provide for the enjoyment of the scenery, natural and historic objects, and wild life in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations."52

Hunting is allowed in NPS-managed units only where it is permitted (i.e., authorized as a discretionary activity) or mandated in statute.53 Hunting may be allowed at specific times for recreational, subsistence, tribal, or conservation reasons.54 In units where hunting is permitted, the park superintendent is to determine whether it is "consistent with public safety, enjoyment, and sound resource management principles."55 Recreational fishing is allowed in park units when it is "authorized or not specifically prohibited by federal law provided that it has been determined to be an appropriate use."56 Where allowed, anglers are subject to approved fishing methods and must fish in accordance with state laws and regulations.57 Within NPS-managed units, hunting is currently statutorily mandated to be allowed in 70 units and authorized to be allowed in 6 additional units, of which 4 allow hunting.58 In addition, elk harvest is allowed for population control in 1 additional unit.59

Bureau of Reclamation

The Bureau of Reclamation (BOR) is responsible for managing lands and waters associated with the construction and operation of many federal water resource development projects in the 17 western states.60 BOR manages 6.6 million acres of land and water and 0.6 million acres of easements.61 On BOR land, the bureau has 289 projects that have developed recreation areas and opportunities for public use.62 Many of these projects are managed by other federal agencies or nonfederal partners.63

The Federal Water Project Recreation Act of 1965 (P.L. 89-72) provides the primary framework for managing recreation and fish and wildlife facilities on BOR lands and waters. The law states that "full consideration shall be given to the opportunities, if any, which the project affords for outdoor recreation" for projects undertaken by the BOR.64 BOR lands and waters are open unless closed for hunting and fishing in accordance with state and federal law.65 Lands and waters may be closed to these activities or public access by an authorized official or by designation as a special use area.66 Special use areas can be designated to limit use of the area for reasons of public interest, such as the protection of health and safety, cultural and natural resources, and environmental and scenic values.67

Department of Defense

As of September 30, 2014, the DOD, excluding USACE civil works sites, administered 11.4 million acres of federally owned land in the United States.68

Management of military lands is the responsibility of each military department and defense agency under the direction of the Secretary of Defense. As amended, the Sikes Act requires the DOD to develop an integrated natural resources management plan for installations with "significant" natural resources, in cooperation with the FWS and appropriate state fish and wildlife agencies, to address the conservation, protection, and management of fish and wildlife resources.69 Further, the Sikes Act requires DOD to provide lands for conservation and sustainable multipurpose use—including hunting and fishing—"consistent with the use of military installations and State-owned National Guard installations to ensure the preparedness of the Armed Forces."70

Pursuant to the Sikes Act, DOD lands therefore may be open to hunting and fishing, if these uses would be consistent with the military mission of the installation. Hunting and fishing access is determined at the installation level based on compatibility both with the management of the natural resources and with military preparedness, safety, and security needs at each installation. Based on the site-specific conditions and needs, DOD policy notes that some installations may be open for public use, whereas others may be restricted to active or retired servicemembers or not open to hunting and fishing at all. Information on the total acreage of DOD lands open to hunting and/or fishing is not available.

Additional federal statutory authorities generally apply state fish and game laws to hunting and fishing that is allowed on military installations or facilities.71 However, the Secretary of Defense may waive the applicability of certain state fish and game laws at an installation for public health or safety reasons, except that the Secretary may not waive the requirement for a state license or the associated fee.72 In the event the Secretary determines a waiver is appropriate, the Secretary must provide written notice to the appropriate state officials at least 30 days prior to the implementation of the waiver. Some installations may also require added registration requirements in order to bring a firearm on base to hunt. The Sikes Act also authorizes the DOD to issue hunting and fishing permits and collect fees for hunting and fishing activities on military installations.73

Although hunting and fishing may be allowed at some installations, DOD policy states that the primary purpose of DOD lands, waters, airspace, and coastal resources is to support mission-related activities.74 In addition to military preparedness, DOD is to manage its natural resources in a way that sustains the long-term ecological integrity of the resource. Additional uses other than military preparedness, such as recreation and public access, can be considered only when compatible with the military mission of the installation and subject to safety requirements and military security. DOD has also promulgated regulations to implement the Sikes Act and other related statutory authorities to manage natural resources and public access, including hunting and fishing, on military installations.75

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

USACE is responsible for the management of 12 million acres of lands and waters as part of the agency's responsibilities to operate authorized water resources projects.76 As 90% of USACE projects are within 50 miles of a metropolitan center, USACE lands and waters are considered by some as an important provider of recreational opportunities.77

USACE project lands and waters are to be managed in the public interest and to provide recreational opportunities.78 As such, hunting is allowed except where prohibited by the overseeing USACE district commander; fishing is allowed except in swimming areas, at boat ramps, and other areas prohibited by the overseeing district commander. These activities are subject to applicable federal, state, and local laws. Fishing is addressed in the law for USACE recreational facilities at water resource development projects, which states that all waters shall be open to public use for boating, swimming, bathing, fishing, and other uses except where the Secretary of the Army finds that these uses are contrary to the public interest.79 Fishing on USACE water projects accounts for 18% of freshwater fishing in the United States;80 USACE projects receive roughly 6.6 million hunter visits annually.81

|

State Management of Hunting and Fishing For the most part, states have the right and responsibility to manage hunting and fishing on federal lands when not in conflict with federal law. This allows states to manage fish and wildlife species and require and provide licenses to hunt and fish, and state authority over hunting and fishing is addressed in several relevant federal statutes that address hunting and fishing. For example, P.L. 109-13 includes Section 6036, titled "Reaffirmation of State Regulation of Resident and Nonresident Hunting and Fishing Act of 2005," which states, "It is the policy of Congress that it is in the public interest for each State to continue to regulate the taking for any purpose of fish and wildlife within its boundaries." However, state authority to regulate hunting and fishing on federal lands does not supersede federal law. Statutes authorizing federal land management agency activities often clarify that agencies shall not impede upon state authority to manage fish and wildlife where it is not in conflict with federal law, and align federal management with state fish and wildlife laws and management to the maximum extent practicable. For example, with regard to state law, the National Fish and Wildlife Administration Act, which provides authority to the FWS to administer lands within the National Wildlife Refuge System, states the following: Nothing in this Act shall be construed as affecting the authority, jurisdiction, or responsibility of the several States to manage, control, or regulate fish and resident wildlife under State law or regulations in any area within the System. Regulations permitting hunting or fishing of fish and resident wildlife within the System shall be, to the extent practicable, consistent with State fish and wildlife laws, regulations, and management plans. (16 U.S.C. §668dd(m)) And FLPMA, which outlines how BLM shall manage public lands that it administers, states that nothing in this Act shall be construed as authorizing the Secretary concerned to require Federal permits to hunt and fish on public lands or on lands in the National Forest System and adjacent waters or as enlarging or diminishing the responsibility and authority of the States for management of fish and resident wildlife. (43 U.S.C. §1732(b)) Despite the predominant allowance for the continued primacy of state management, federal agencies do have the authority to open and close federal lands and waters to hunting and fishing. Furthermore, the federal agencies must also manage hunting and fishing on lands to be consistent with federal laws authorizing the land management agencies or those cited below, such as the Migratory Bird Treaty Act or the Endangered Species Act. For more information, see CRS Report R44267, State Management of Federal Lands: Frequently Asked Questions, by Carol Hardy Vincent and Alexandra M. Wyatt. |

Federal Statutes Related to Hunting, Fishing, and Recreational Shooting

Many federal laws are relevant to hunting and fishing on federal lands and waters. Furthermore, federal land management agencies manage lands and waters they administer pursuant to federal laws, even when they may conflict with state law.82 Federal laws can be specific to a particular land management agency, such as the agency-specific statutes cited above; to a particular species; or to a particular parcel of federal land, such as a wildlife refuge. These laws outline the purpose and mission of specific agencies and determine whether lands and waters managed by these agencies are open unless closed or closed unless open. (See "Hunting and Fishing on Federal Lands" for more information on agency-specific laws.) In contrast, other laws pertain to hunting and fishing at the national scale or are related to hunting- or fishing-related programs or taxation. This section will focus on the federal statutes applicable to hunting and fishing more generally.

Migratory Bird Treaty Act

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 (MBTA) implements a bipartite convention between the United States and Great Britain (on behalf of Canada).83 The original act has been amended several times to implement subsequent conventions between the United States and Mexico, Japan, and the Soviet Union (now Russia). The MBTA provides the authority to regulate the take (including through hunting) and transport of migratory game birds (and mammals in the case of the United States-Mexico agreement) as well as a framework for punishment of any violations under the conventions of the MBTA. The FWS has regulatory authority over MBTA provisions. The MBTA establishes that it is unlawful to take, possess, or trade any migratory bird or its parts covered by the conventions, unless specifically permitted by regulation pursuant to the MBTA.84

This law applies to species that are native to the United States or U.S. territories.85 In addition to the broad prohibitions, the MBTA authorizes the Secretary of the Interior to regulate hunting seasons for migratory birds, pursuant to the original bipartite treaties. The Secretary of the Interior, after taking into account environmental conditions and the terms of the original convention, can set hunting seasons and approve methods to hunt migratory birds.86 For migratory game birds, the agreements dictate the window within which the hunting season can be established.87 FWS is responsible for identifying the "outside limits (frameworks)" for the open season within this window annually.88 Setting the hunting season for migratory game birds occurs through the federal rulemaking process, which provides for opportunity for public comment on proposed rules. In addition to state-based hunting regulations, the MBTA also provides the framework to establish tribal hunting regulations for migratory game birds. Once FWS has established the outside limits for hunting, individual states are allowed to set their own hunting seasons within the federally approved season pursuant to the MBTA.

Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp Act

The Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp Act of 1934 (the Duck Stamp Act) requires that waterfowl hunters over the age of 16 annually purchase and carry a valid federal hunting stamp (known as a duck stamp) in addition to any required licenses under state laws for hunting waterfowl.89 Duck stamps are purchased by hunters as a requirement for hunting waterfowl and by collectors for collection and conservation purposes.90 The Duck Stamp Program provides a funding source to support bird habitat conservation. The Duck Stamp Program is jointly operated through the U.S. Postal Service and the Department of the Interior; duck stamps may be purchased in person or electronically.

The proceeds from duck stamp sales are deposited into the Migratory Bird Conservation Fund (MBCF).91 Monies from the fund are used for habitat conservation purposes through the acquisition of "waterfowl production areas" pursuant to the Migratory Bird Conservation Act.92 The price of the stamp has increased from $1 in 1934 to $25 as of 2018.93 All proceeds in excess of $15 from each stamp sold after 2013 are placed into a subaccount within the MBCF for the acquisition of conservation easements for migratory birds.94 Since 1934, the sale of duck stamps has generated over $950 million for the MBCF.95

Endangered Species Act

The Endangered Species Act (ESA) was passed in 1973 to protect and recover species and their ecosystems that are imperiled or at risk of extinction.96 Once a species is listed as threatened or endangered under ESA, certain prohibitions apply on interactions with the species. For example, listed species are not allowed to be "taken" without certain permits. Under ESA, "take" is defined as "to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or to attempt to engage in any such conduct."97

This prohibition directly relates to hunting and fishing.98 Some exceptions to prohibitions on take are provided for activities subject to the acquisition of a permit.99

Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act and Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration Act

The Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act (commonly referred to as the Pittman-Robertson Act) and the Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration Act (commonly referred to as the Dingell-Johnson Act) are both related to hunting and fishing.100 Both laws mandate excise taxes on hunting- and fishing-related equipment.101 The proceeds from these taxes are diverted to a fund (the Federal Aid to Wildlife Restoration Fund) and apportioned to states for conservation and education programs. Products taxed under the Pittman-Robertson Act include firearms, handguns, ammunition, and archery equipment. Products taxed under the Dingell-Johnson Act include sport fishing equipment, outboard boat motors, and motorboat and small engine fuels. In FY2016, receipts from excise taxes were estimated at $787 million for Pittman-Robertson and $628 million for Dingell-Johnson.102

Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act

Management of federal lands and waters in Alaska can be different than that of comparable lands and waters outside the state. In addition to authorities guiding the actions of federal land management agencies (e.g., FLPMA, National Wildlife Refuge System Administration Act, and National Park Service Organic Act), Alaskan federal lands and waters are also governed pursuant to the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA).103

ANILCA establishes requirements for both recreational (sport) and subsistence hunting and fishing on federal lands and waters.104 ANILCA generally specifies the importance of hunting and fishing in Alaska and directs the Secretary of the Interior to implement a subsistence hunting and fishing program for national parks in Alaska.105 ANILCA also mandates that sport hunting and fishing be allowed in national preserves, which are to be managed as units of the National Park System.106

Laws Related to International Hunting and Fishing

International sport and trophy hunting is managed by the foreign country in which the hunting takes place and can be subject to international treaties, such as the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES).107 Under CITES, species are categorized into one of three appendixes corresponding to how threatened their population is due to trade; Appendix I consists of species most threatened with extinction. Although commercial trade in Appendix I species generally is prohibited under CITES, sport hunting is not considered a commercial activity. However, the import and trade of foreign trophies and animal parts into and within the United States are subject to U.S. regulations, including ESA. If a species is listed as endangered, import of a sport-hunted trophy is prohibited unless an enhancement of survival permit is obtained and used. Enhancement of survival implies that the import of endangered animals or their parts or products will provide incentives for increasing the survival of the species in its native habitat. If a species is listed as threatened, the same rules as if the species were endangered apply unless there is a special rule, which may allow for a limited number of trophies to be imported.

The illegal killing of a foreign species (according to U.S. or foreign law) and the subsequent import of the animal or animal parts into the United States could be a violation of the Lacey Act.108 Under the Lacey Act, it is unlawful for any person to import, export, transport, sell, receive, acquire, or purchase in interstate or foreign commerce any wildlife taken, possessed, transported, or sold in violation of any law or regulation of any foreign law. Other laws—including the Marine Mammal Protection Act (16 U.S.C. §§1361 et seq.) and the Fisherman's Protection Act (22 U.S.C. §§1971-1979)—are also relevant to the import and trade of internationally hunted or fished species within the United States.

Selected Administrative Actions on Hunting and Fishing

Hunting and fishing issues have been addressed in administrative actions through a number of policy mechanisms, including executive, secretarial, and director's orders and the rulemaking process. Presidents have on many occasions worked to promote and protect opportunities for hunting and fishing on federal lands and waters as well as conservation and resource management efforts.109 For example, Presidents have used executive orders through their authority under the Antiquities Act of 1906 to designate national monuments, many of which have both conservation and recreation embedded within their purposes.110

These efforts to conserve federal lands and promote hunting and fishing have continued in recent administrative efforts. Table 1 contains a list of selected recent administrative actions pertaining to hunting and fishing.

|

Date |

Event |

Description |

|

August 16, 2007 |

E.O. 13443 issued by President George W. Busha |

E.O. 13443 directed federal agencies to facilitate the expansion and enhancement of hunting opportunities, called for a Conference on North American Wildlife Policy, and required publication of a Recreational Hunting and Wildlife Conservation Plan. |

|

April 16, 2010 |

Presidential Memorandum issued by President Barack Obamab |

Memorandum established the America's Great Outdoors Initiative aimed at promoting conservation and reconnecting Americans with the outdoors and called for the publication of an action plan as well as progress reports in 2011 and 2012. |

|

March 2, 2017 |

S.O. 3347 issued by DOI Secretary Ryan Zinkec |

S.O. 3347 sought to enhance conservation stewardship; increase outdoor recreation; and improve the management of game species and their habitat by assessing implementation of E.O. 13443. |

|

September 15, 2017 |

S.O. 3356 issued by DOI Secretary Ryan Zinked |

S.O. 3356 continued the Department of the Interior's efforts to enhance conservation stewardship; increase outdoor recreation opportunities; and improve the management of game species and their habitats. |

Source: CRS, using the following:

a. Executive Order 13443, "Facilitation of Hunting Heritage and Wildlife Conservation," 72 Federal Register 46537-46538, August 20, 2007.

b. Executive Office of the President, "A 21st Century Strategy for America's Great Outdoors," 75 Federal Register 20765-20769, April 20, 2010.

c. Department of the Interior Secretarial Order 3347, "Conservation Stewardship and Outdoor Recreation," March 2, 2017.

d. Department of the Interior Secretarial Order 3356, "Hunting, Fishing, Recreational Shooting, and Wildlife Conservation Opportunities and Coordination with States, Tribes, and Territories," September 15, 2017.

E.O. 13433

President George W. Bush issued Executive Order 13443 (E.O. 13443) on August 16, 2007.111 The purpose of E.O. 13443 was to facilitate the expansion and enhancement of hunting activities and game management by federal agencies on federal lands. To achieve this purpose, every agency with federal land management responsibilities was directed to expand and enhance hunting opportunities for the public, consistent with their missions.112 E.O. 13443 also required the completion of the Recreational Hunting and Wildlife Resource Conservation Plan and established the Wildlife and Hunting Heritage Conservation Council.113 The conservation plan provided a 10-year plan to implement E.O. 13433, and the council was tasked with advising the Secretaries of the Interior and Agriculture on wildlife conservation and hunting issues.

Department of the Interior Secretarial Orders in the 115th Congress

Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke has introduced several secretarial orders (S.O.s). Two of these—S.O. 3347 and S.O. 3356—are directly related to implementing E.O. 13443 and expanding hunting and fishing opportunities on federal lands and waters.114

S.O. 3347, "Conservation Stewardship and Outdoor Recreation," was issued by Secretary Zinke on March 2, 2017. S.O. 3347 required two reports: an assessment of the implementation of E.O. 13443 and recommendations to improve implementation and recommendations; the other report included recommendations to enhance and expand recreational fishing. S.O. 3347 required that these reports be shared with the Wildlife and Hunting Heritage Conservation Council and the Sport Fishing and Boating Partnership Council, respectively, for consensus recommendations so that DOI could identify specific actions to expand access for hunting, fishing, and recreational shooting activities; improve coordination with states; improve habitat for fish and wildlife; manage predators effectively; and facilitate greater public access to DOI lands.

S.O. 3356, "Hunting, Fishing, Recreational Shooting, and Wildlife Conservation Opportunities and Coordination with States, Tribes, and Territories," was issued on September 15, 2017. S.O. 3356 directed bureaus and offices within DOI, in collaboration with states, tribes, and territorial partners, to implement programs to promote conservation and enhance hunting, fishing, and recreational shooting opportunities on federal lands and waters.

Specifically, S.O. 3356 directed DOI bureaus and offices to

- implement recommendations from S.O. 3347;

- increase access to DOI lands and waters for sportsperson activities;

- update and amend regulations and management plans to include sportsperson activities, including increasing opportunities in national monuments;

- improve opportunities for underrepresented groups, such as veterans and youth, to enhance hunting and fishing traditions; and

- increase migratory waterfowl populations and hunting opportunities while improving habitat conservation efforts; among other activities.

Reactions to S.O.s 3347 and 3356 have been mixed.115 Proponents emphasize that federal lands are owned by all U.S. citizens and should be managed accordingly. Further, they note that the order will facilitate access to federal lands and waters for hunting and fishing opportunities and further conservation interests.116 Others have criticized S.O. 3356, stating that hunting and fishing activities are already included in existing multiple-use land management practices and that the purpose of the order was to distract from other administrative activities that could diminish environmental protection of federal lands, such as increasing energy and mineral production and altering national monuments.117

Issues for Congress

Issues related to hunting and fishing are routinely considered by Congress. Many of these issues pertain to federal lands and waters and how to balance opportunities for hunting and fishing with the conservation of ecosystems and species. Some issues related to hunting and fishing that are deliberated by Congress include establishing what federal lands can be accessed for hunting and fishing; determining what types of land should be open to hunting and fishing; how to regulate the opening and closing of land to hunting and fishing; whether to reauthorize or amend existing laws that are related to hunting and fishing; and regulating the use of ammunition and tackle on federal lands. These issues, which represent only a subset of the broader array of hunting and fishing issues Congress might consider, are discussed below. (See Appendix for more information on legislation proposed in the 115th Congress.)

Access to Federal Lands and Waters

Access to federal lands and waters is a concern for hunters and anglers. Access can refer to whether lands and waters are open to hunting and fishing, as well as what procedures are required to prohibit hunting and fishing, and whether individuals can physically access federal lands and waters. The latter is a concern when federal lands and waters are blocked from entry due to inholdings, historic land ownership patterns, or inadequate entry points, or when lands are barred from entry.118 Some contend that limited access to federal lands and waters can reduce opportunities for outdoor recreation, including hunting and fishing, and have suggested that Congress should increase efforts to authorize acquisition and expansion to ensure public lands are accessible.119 Others argue that the federal estate of lands and waters is too large and that there should be greater attention on managing existing lands and addressing the maintenance backlog rather than acquiring new lands.120 Others have also supported transferring federal lands to the states, but this suggestion has been contentious, and some have expressed concerns that transferring would diminish access for hunters and anglers.121

In the 115th Congress, several bills aim to identify barriers and opportunities to improve access for recreation on federal lands and waters. For example, H.R. 4489 (Title XV), S. 733 (§206), and S. 1460 (§8106) would require the Secretaries responsible for NPS, FWS, BLM, and FS to identify federal lands and waters that have limited or no access for hunting and fishing. The bills would also require the Secretaries to identify opportunities for improving access options.

Some bills also identify ways to improve access to restricted federal lands and waters, whereas others aim to improve opportunities for recreation on already accessible federal lands and waters. For example, H.R. 3400 and S. 1633 seek to streamline the permitting and renewal process for special recreation permits (including for cross-jurisdictional activities),122 provide increased opportunities for servicemembers and veterans to have access to outdoor recreation and volunteer activities, extend recreation seasons, and designate new national recreation areas. Although there is general support by many stakeholders for the concepts of streamlining permitting and increasing opportunities for veterans, some have commented that the bill language could be adjusted to clarify the intent of the bills as well as to ensure that the streamlining authority is provided through statute.123

Whether lands and waters are open to hunting and fishing is determined by authorizing statutes and missions for land management agencies as well as the purpose of individual units within the various land management systems. Some stakeholders contend that more federal lands and waters should be open to hunting and fishing. They support their position by stating that federal lands and waters are owned by all Americans and should be managed for the benefit of all Americans, including hunters and anglers.124 Others temper this sentiment by arguing that some lands should be kept off-limits for hunting and fishing, and that although multiple use is appropriate for some areas, it is inappropriate for some lands that should be set aside for conservation and preservation. Some also believe that hunting and fishing should be regulated where they affect other recreational activities on federal lands.

Several bills in the 115th Congress would also address opening and closing some federal lands to hunting and fishing. For example, H.R. 3668 (Title IV), H.R. 4489 (Title XII), S. 733 (Title II), and S. 1460 (Title VIII) would all clarify that BLM and FS lands are open to hunting and fishing unless specifically closed. Each bill also outlines the necessary procedures that would be required to close lands and waters to sportsperson activities. These requirements would include public comment and increased notification of local stakeholders. These bills would also codify the open unless closed policy for FS and BLM with regard to hunting and fishing activities. Although BLM and FS are the focus of these bills, both S. 733 and S. 1460 would also establish that it is the policy of the United States for all agencies and departments, in line with their missions, to facilitate the expansion and enhancement of hunting and fishing.125 Some titles within the legislation have been subject to controversy.126 Specific to the BLM and FS hunting and fishing provisions, some have argued that these provisions will ensure hunting and fishing are protected in the multiple-use mandates for FS and BLM, whereas others suggest that enactment of these changes could unjustifiably prioritize hunting and fishing activities while marginalizing other purposes, such as wilderness.

Reauthorizations

Congress routinely considers reauthorizing appropriations and/or programmatic authorities that are either directly or indirectly related to hunting and fishing. Within the deliberations regarding the reauthorization or modification of these laws, issues related to hunting and fishing on federal lands may surface. For example, several stakeholder groups have highlighted that certain conservation programs, such as the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF)127 and the North American Wetlands Conservation Act (NAWCA), directly relate to hunting and fishing because they can lead to greater access to federal lands and support the wildlife populations needed for hunting and fishing.128 Others have contended that programs that support acquiring more federal land are not the best means to support conservation or provide greater access for hunters and fishers.129 For example, some have suggested that LWCF should be made available for maintenance of existing federal land rather than acquisition of new lands.130 Similarly, hunting and fishing stakeholders have argued that the Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Act needs to be amended to reflect the needs of the states and provide greater support for hunter and angler retention and recruitment.131 Several bills in the 115th Congress would address these and other concerns (for specific examples, see Appendix).

Extension of LWCF has been proposed in several bills in the 115th Congress.132 H.R. 502, H.R. 4489 (Title III), S. 896, and S. 1460 (§5102) would provide a permanent authorization for LWCF and would require funds within LWCF to be used specifically for projects to secure recreational public access on existing federal lands for hunting, fishing, and other recreational purposes. S. 1460 would also amend LWCF to set minimum percentages for certain uses of the fund. Perspectives on if and how to reauthorize LWCF have been mixed.133 Proponents have stated that it is a necessary source of funding to acquire and protect lands, which is necessary to enhance public access; opponents have argued that LWCF, in its current form, is flawed and that the federal estate should not prioritize acquiring new lands through LWCF.134

Several bills have proposed reauthorization of NAWCA in the 115th Congress.135 H.R. 1099, H.R. 3668 (Title XIII), and H.R. 4489 (Title I) would all extend NAWCA through FY2022; S. 1460 (§8403) would extend authorization through FY2023. However, although H.R. 1099 would only extend authorization, the other bills would also amend NAWCA in other ways, including through requirements for notification (H.R. 4489 and S. 1460), provision for the long-term management of any acquired property or interest (H.R. 4489), and limitation on acquisition of lands administered by the federal government (H.R. 3668). Some also argue that NAWCA supports hunting and fishing activities by supporting projects to improve bird populations and wetland habitat.136 Some have also argued that language to limit acquisition authority under NAWCA (such as that proposed in H.R. 3668) is contrary to its purpose.137

Several bills—H.R. 788, H.R. 3668 (Title II), H.R. 4489 (Title XI), S. 593, S. 733 (§401), and S. 1460 (§8401)—would amend the Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Act to allow more funding allocated to the states to be used for target ranges. H.R. 2591 and S. 1613 would amend Pittman-Robertson to allow for the provision of financial and technical assistance to the states for the promotion of hunting and recreational shooting. Supporters of these bills note that they would allow Pittman-Robertson funds to be used in a way that is more in line with states' needs.138 Others may view them as diverting money from existing priority wildlife restoration activities.

Regulation of Ammunition and Tackle

Regulation of ammunition and tackle based on lead content is a contentious issue. Federal regulations for lead differ depending on both the hunting and fishing activity as well as location. Broadly, lead in ammunition is currently regulated for hunting waterfowl, coots, and those species included in aggregate bags and concurrent seasons with waterfowl and coots.139 Although lead in other ammunition and tackle is generally not regulated at the federal level, use of lead ammunition and tackle may be regulated for specific federal land units, such as on some national wildlife refuges, pursuant to federal regulations and/or state law.140 Some stakeholders have argued that regulating lead in other ammunition and fishing tackle is unnecessary and cost prohibitive. They note that the use of lead ammunition is already regulated for waterfowl hunting since regulations were phased in starting in 1987 and implemented nationwide in 1991.141 Other stakeholders argue that lead in fishing tackle and ammunition is dangerous to the environment and can poison species and threaten the health of consumers who eat animals killed by lead ammunition and tackle.142 Currently, ammunition is exempt from regulation under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), and tackle has recently been exempted from regulations based on lead content through annual appropriations bills.143

This issue has been addressed through administrative actions. For example, FWS Director's Order 219, issued on January 19, 2017, would phase out the use of lead ammunition and tackle on FWS-managed lands. However, on March 2, 2017, DOI Secretary Zinke issued S.O. 3346, rescinding the previous order. The rescinding action received mixed reactions, with supporters claiming that it would ease unnecessary restriction on hunters and anglers and opponents arguing that continued use of lead ammunition and tackle will threaten wildlife and pollute the environment.144

This issue has also been addressed in legislation in the 115th Congress. In addition to P.L. 115-31, which prohibited the use of funds to regulate tackle based on lead content in FY2017, the issue of regulating lead tackle has been raised in several other bills. For example, H.R. 3354 (the House version of the FY2018 Interior and Environment Appropriations bill) would extend the prohibition on using federal funds to regulate tackle, as has been mandated in recent years. Similarly, S. 1460 would prohibit the Environmental Protection Agency from regulating tackle based on lead content until 2028, and H.R. 3668 would prohibit any DOI or USDA bureaus or agencies from regulating ammunition or tackle based on lead content.145

Appendix. Summary of Selected Legislation in the 115th Congress Addressing Sportsperson Issues

The following table presents issues addressed within selected hunting and fishing legislation introduced in the 115th Congress. These four bills were selected from the many that have been introduced because they each address multiple sportsperson-related issues. Table A-1 includes selected sportsperson and general federal land issues included within these bills and, as such, includes certain issues that are outside the scope of this report.

|

Issue Area |

||||

|

Lead in fishing tackle |

Title I |

— |

— |

§8404 |

|

Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Act (16 U.S.C. §669 et seq.) |

Title II |

Title XI |

§401 |

§8401 |

|

Firearms at U.S. Army Corps of Engineers water resources development projects |

Title III |

— |

— |

§8107 |

|

Opening, closing, and access to federal lands and waters for hunting, fishing, and recreational shooting |

Title IV |

Titles XII, XIV, XV |

Title II |

§§8101-8104, 8106 |

|

No priority for hunting, fishing, or recreational shooting |

§403 |

Title XX |

§602 |

§8502 |

|

Volunteer hunters in wildlife management |

§404 |

Title XVIII |

§502 |

§7136 |

|

Clarifying agricultural practices and baiting in migratory game bird hunting |

Title V |

— |

— |

— |

|

Transporting bows across National Park Service lands |

Title VI |

Title XVII |

§501 |

§7135 |

|

Respect for treaties and rights |

Title VII |

Title XIX |

§601 |

§8501 |

|

State approval for fishing restriction within National Park Service or Office of National Marine Sanctuary managed waters |

Title VIII |

— |

— |

— |

|

Equal Access to Justice Act (5 U.S.C. §504; 28 U.S.C. §2412) |

Title IX |

— |

§205 |

§8105 |

|

Access to federal lands for Good Samaritan search and recovery |

Title X |

— |

— |

§6107 |

|

Interstate transportation of firearms and ammunition |

Title XI |

— |

— |

— |

|

Importation of polar bear trophies hunted legally in Canada before specified date |

Title XII |

— |

— |

— |

|

North American Wetlands Conservation Act (16 U.S.C. §4401 et seq.) |

Title XIII |

Title I |

— |

§8403 |

|

Gray wolves final rule reissuance |

Title XIV |

— |

— |

— |

|

Hearing protection (silencers) |

Title XV |

— |

— |

— |

|

Consideration of ammunition and firearms classification |

Title XVI |

— |

— |

— |

|

Federal Land Transaction Facilitation Act (43 U.S.C. §2301 et seq.) |

Title XVII |

Title II |

§207 |

§8201 |

|

Commercial filming and photography on federal lands |

Title XVIII |

Title XVI |

Title III |

§8301 |

|

Respect for state wildlife management authority |

Title XIX |

Title XXI |

§603 |

§8503 |

|

Bison management in the Grand Canyon |

Title XX |

— |

— |

— |

|

Recreation permits for guides and outfitters |

Title XXI |

— |

— |

— |

|

Hunting and fishing within certain National Forests |

Title XXII |

— |

— |

— |

|

Land and Water Conservation Fund (54 U.S.C. §200306) |

— |

Title III |

— |

§5102 |

|

National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (16 U.S.C. §§3701-3710) |

— |

Title IV |

— |

— |

|

Neotropical Migratory Bird Conservation Act (16 U.S.C. §6109) |

— |

Title V |

— |

— |

|

Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program (16 U.S.C. §3774) |

— |

Title VI |

— |

— |

|

Fish and wildlife coordination for invasive species |

— |

Title VII |

— |

— |

|

Multinational Species Conservation Funding |

— |

Title VIII |

— |

— |

|

Wildlife conservation prize competition establishment |

— |

Title IX |

— |

— |

|

Fish habitat conservation |

— |

Title X |

— |

— |

|

Wildlife Hunting and Heritage Conservation Council Advisory Committee authorization |

— |

Title XIII |

§402 |

§8402 |

|

Declaration of national policy regarding hunting, fishing, and recreational shooting |

— |

— |

Title I |

§8001 |

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

For example, see Department of the Interior Secretarial Order 3356, "Hunting, Fishing, Recreational Shooting, and Wildlife Conservation Opportunities and Coordination with States, Tribes, and Territories," September 15, 2017. |

| 2. |

U.S. Department of the Interior, "Everything You Need to Know About Hunting on Public Lands," Blog, https://www.doi.gov/blog/everything-you-need-know-about-hunting-public-lands. |

| 3. |

Ibid. |

| 4. |

For example, see U.S. Department of the Interior, "Secretary Zinke Signs Secretarial Order to Support Sportsmen & Enhance Wildlife Conservation," press release, September 15, 2017, https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/secretary-zinke-signs-secretarial-order-support-sportsmen-enhance-wildlife. |

| 5. |

For example, see Bo Peterson, "Hunters Want to Expand Reach in South Carolina's Federal Lands," The Post and Courier, October 7, 2017. |

| 6. |

The most recent survey analyzed 2016 data. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2016 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation: National Overview (Preliminary Findings), August 2017, https://wsfrprograms.fws.gov/subpages/nationalsurvey/nat_survey2016.pdf. |

| 7. |

The survey methodology focuses on participants 16 years old and older who actively participated in wildlife-related activities in the survey year. As such, it may undercount the total number of sportspersons in the United States by excluding hunters and anglers who did not actively engage in hunting and fishing during the survey year. |

| 8. |

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2016 Survey, "Director's Message." Individuals may have participated in multiple activities, resulting in a total participation number smaller than the sum of participation numbers across the various activities. |

| 9. |

Ibid., p. 4. |

| 10. |

Department of the Interior, "Secretary Zinke Signs Secretarial Order to Support Sportsmen & Enhance Wildlife Conservation," press release, September 15, 2017, https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/secretary-zinke-signs-secretarial-order-support-sportsmen-enhance-wildlife. |

| 11. |

Ibid., p. 8. |

| 12. |

For more information on the federal estate, see CRS Report R42346, Federal Land Ownership: Overview and Data, by Carol Hardy Vincent, Laura A. Hanson, and Carla N. Argueta. |

| 13. |

This number includes hunters who hunted on both public and a combination of public and private lands. A more detailed count for federal lands only is not available in the report. The 2011 survey is the most current complete survey. The 2016 Preliminary Results do not include a breakdown for hunting by land type. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2011 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting, and Wildlife-Associated Recreation, February 2014, p. 81, https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/fhwar/publications/2011/fhw11-nat.pdf. |

| 14. |

Ibid. Western states include Alaska, California, Hawaii, Oregon, Washington, Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming. Eastern states include Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Vermont, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia, and West Virginia. |

| 15. |

For example, see U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, FY 2016 Report: Status of Hunting and Fishing on National Wildlife Refuge System Lands, December 2016, p. 12, https://www.fws.gov/refuges/realty/pdf/2016_Hunting_Status.pdf. Also, personal communication between R. Eliot Crafton, Analyst in Natural Resources Policy, and Bureau of Land Management Legislative Affairs Division, February 6, 2018. |

| 16. |

Appropriate state licenses are generally required to hunt or fish on federal properties, but there are some exceptions to this requirement. For example, select national park units do not require state fishing licenses in order to fish within park boundaries. |

| 17. |

Approximately 2 million acres of BLM land are closed to hunting and/or shooting permanently or seasonally. Personal communication between R. Eliot Crafton, Analyst in Natural Resources Policy, and Bureau of Land Management Legislative Affairs Division, February 6, 2018. |

| 18. |

Personal communication between R. Eliot Crafton, Analyst in Natural Resources Policy, and U.S. Forest Service Legislative Affairs, February 7, 2018. |

| 19. |

Acreage for fishing is not available because, in some cases, states may own the submerged lands (e.g., lakebeds) within wetland refuge boundaries. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, FY 2016 Report: Status of Hunting and Fishing on National Wildlife Refuge System Lands, December 2016, https://www.fws.gov/refuges/realty/pdf/2016_Hunting_Status.pdf. |

| 20. |

Of the 38 wetland management districts, 35 include multiple waterfowl production areas, whereas 3 are individual waterfowl production areas that are not included within a wetland management district. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Statistical Data Tables for Fish & Wildlife Service Lands (9/30/2017), https://www.fws.gov/refuges/land/PDF/2017_Annual_Report_of_Lands_Data_Tables.pdf. |

| 21. |

Of the six NPS units where hunting is authorized but not mandated, four currently permit hunting. Personal communication between Laura B. Comay, Analyst in Natural Resources Policy, and National Park Service Office of Legislative and Congressional Affairs, May 25, 2016. |

| 22. |

CRS, based on analysis of data provided from sources in this section. |

| 23. |

Bureau of Land Management, Public Land Statistics 2016, May 2017, https://www.blm.gov/download/file/fid/15388. |

| 24. |

The 11 western states are Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. See U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Public Land Statistics, 2016, Table 1-4, https://www.blm.gov/about/data/public-land-statistics. |

| 25. |

43 U.S.C. §1701 et seq. FLPMA is sometimes called the BLM Organic Act. |

| 26. |

43 U.S.C. §1702(c). |

| 27. |

43 U.S.C. §1702(h). |

| 28. |

43 U.S.C. §1702(l). |

| 29. |

Personal Communication between R. Eliot Crafton, Analyst in Natural Resources Policy, and Bureau of Land Management Legislative Affairs Division, February 6, 2018. |

| 30. |

For example, access may be limited around elk wintering areas. Personal Communication between R. Eliot Crafton, Analyst in Natural Resources Policy, and Bureau of Land Management Legislative Affairs Division, February 6, 2018. |

| 31. |

Ibid. |

| 32. |

43 U.S.C. §1732(b). In addition, any management decision (or action pursuant to such decision) that excludes a major use, including fish and wildlife use and outdoor recreation, for two or more years on a tract of land of 100,000 acres or more, is subject to congressional review. See 43 U.S.C. §1712(e). This procedure and certain other provisions of FLPMA may be unconstitutional under Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919 (1983). |

| 33. |

43 C.F.R. §8364.1. |

| 34. |

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Land Areas Report—As of Sept 30, 2017, Tables 1 and 4, https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar/LAR2017/LAR_Book_FY2017.pdf. Data reflect land within the NFS, including national forests, national grasslands, purchase units, land utilization projects, experimental areas, and other areas. The west includes Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, Nevada, North Dakota, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. The east includes all of the other states except for Alaska, and also includes 28,849 acres in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. For more information on the NFS, see CRS Report R43872, National Forest System Management: Overview, Appropriations, and Issues for Congress. |

| 35. |

16 U.S.C. §475. |

| 36. |

16 U.S.C. §528. |

| 37. |

16 U.S.C. §531. |

| 38. |

16 U.S.C. §531. |

| 39. |

36 C.F.R. 241.1-241.3. For more information, see (1) U.S. Forest Service, Hunting, https://www.fs.fed.us/visit/know-before-you-go/hunting; (2) U.S. Forest Service, Great Places to Fish With Us, https://www.fs.fed.us/visit/know-before-you-go/great-places-to-fish-with-us; (3) Shooting, https://www.fs.fed.us/visit/know-before-you-go/shooting. |

| 40. |

For example, see 16 U.S.C. §539g(e), which addresses hunting and fishing in the Kings River Special Management Area in California. |

| 41. |

16 U.S.C. §539h. |

| 42. |

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Statistical Data Tables for Fish & Wildlife Service Lands (9/30/2017), https://www.fws.gov/refuges/land/PDF/2017_Annual_Report_of_Lands_Data_Tables.pdf. In total, the FWS manages 856 million acres of lands and submerged lands and waters either through either primary or secondary jurisdiction. Most of these acres are in several national marine monuments in the Pacific Ocean. |

| 43. |

16 U.S.C. §668dd. |

| 44. |

16 U.S.C. §668dd(a)(3)(C). |

| 45. |

50 C.F.R. §32 outlines provisions for opening refuges to hunting and fishing. |

| 46. |

This is true of all refuges except those in Alaska. |

| 47. |