Guns, Excise Taxes, Wildlife Restoration, and the National Firearms Act

Federal taxes on firearms and ammunition are collected through different methods and used for different purposes, depending on the nature of the firearms. Some tax receipts are used for wildlife restoration and for hunter education and safety, for example, whereas others are deposited into the General Fund of the U.S. Treasury. The assessment of these taxes and the uses of generated revenues are routinely of interest to many in Congress.

In general, taxes on the manufacture of firearms (including pistols and revolvers as well as rifles and other long guns) and ammunition are collected as excise taxes based on the manufacturer’s or importer’s sales price, under the Internal Revenue Code (26 U.S.C. §4181). These taxes are imposed on the manufacturer’s sales price at a rate of 10% on pistols and revolvers and 11% on ammunition and other firearms. (Pistols and revolvers, ammunition, and other firearms each account for about a third of these tax revenues.) The tax, which raised $761.6 million in FY2017, is administered by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) in the Department of the Treasury.

These revenues are allocated to the Federal Aid to Wildlife Restoration Fund, also known as the Wildlife Restoration Trust Fund, and used for wildlife restoration and for hunter safety and education purposes. Established by the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act of 1937 (16 U.S.C. §§669-669k, commonly known as the Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Act), the Wildlife Restoration Trust Fund is administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in the Department of the Interior. It also receives revenues from taxes on bows and arrows (26 U.S.C. §4161(b)). Amounts in the fund are allocated to states and selected territories based on formulas, with the largest share for wildlife restoration, apportioned one-half according to the size of the area and one-half according to the area’s share of the overall number of hunting licenses (with a floor and ceiling on these allocations). The federal cost share for most activities receiving support from the fund is capped at 75%.

Taxes also are collected for the making and transfer of certain types of firearms and equipment (such as machine guns, short-barreled firearms, and silencers) regulated under the National Firearms Act (NFA; 26 U.S.C. §§5801 et seq.). These taxes originally were set at a level intended to slow the transfer of these weapons, although the tax has not been raised since the NFA was enacted in 1934. In addition, special occupational taxes are collected from federally licensed gun dealers who manufacture, import, or sell NFA firearms. NFA-generated tax receipts are deposited into the General Fund of the Treasury. These tax receipts totaled $68.6 million in FY2016.

A variety of proposals have been advanced in recent Congresses that could affect the taxes on firearms and the uses of resulting revenues. In the 115th Congress, some legislative proposals, several of which are known as the Hearing Protection Act, would remove firearm silencers from regulation and taxation under the NFA; firearm silencers would be taxed along with pistols and revolvers at 10%, with revenues deposited into the Wildlife Restoration Trust Fund primarily in support of public target ranges. Other proposals would allow funds to be used to promote hunting and recreational shooting or for Mexican gray wolf management. Still other proposals would increase taxes on guns or ammunition, with proceeds used for gun-violence concerns (e.g., compensation to teachers who are victims of a school shooting, hiring law enforcement personnel, and neighborhood safety).

Guns, Excise Taxes, Wildlife Restoration, and the National Firearms Act

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- The Excise Taxes on Firearms, Ammunition, and Archery Equipment

- The Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Trust Fund: Apportionment and Use

- Types of P-R Funding

- Taxes and Fees Under the 1934 National Firearms Act and Gun Control Act of 1968

- Legislative Proposals

- Proposals to Modify the Treatment of Silencers

- Proposals to Modify Pittman-Robertson Act

- Proposals to Increase Taxes

Summary

Federal taxes on firearms and ammunition are collected through different methods and used for different purposes, depending on the nature of the firearms. Some tax receipts are used for wildlife restoration and for hunter education and safety, for example, whereas others are deposited into the General Fund of the U.S. Treasury. The assessment of these taxes and the uses of generated revenues are routinely of interest to many in Congress.

In general, taxes on the manufacture of firearms (including pistols and revolvers as well as rifles and other long guns) and ammunition are collected as excise taxes based on the manufacturer's or importer's sales price, under the Internal Revenue Code (26 U.S.C. §4181). These taxes are imposed on the manufacturer's sales price at a rate of 10% on pistols and revolvers and 11% on ammunition and other firearms. (Pistols and revolvers, ammunition, and other firearms each account for about a third of these tax revenues.) The tax, which raised $761.6 million in FY2017, is administered by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) in the Department of the Treasury.

These revenues are allocated to the Federal Aid to Wildlife Restoration Fund, also known as the Wildlife Restoration Trust Fund, and used for wildlife restoration and for hunter safety and education purposes. Established by the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act of 1937 (16 U.S.C. §§669-669k, commonly known as the Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Act), the Wildlife Restoration Trust Fund is administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in the Department of the Interior. It also receives revenues from taxes on bows and arrows (26 U.S.C. §4161(b)). Amounts in the fund are allocated to states and selected territories based on formulas, with the largest share for wildlife restoration, apportioned one-half according to the size of the area and one-half according to the area's share of the overall number of hunting licenses (with a floor and ceiling on these allocations). The federal cost share for most activities receiving support from the fund is capped at 75%.

Taxes also are collected for the making and transfer of certain types of firearms and equipment (such as machine guns, short-barreled firearms, and silencers) regulated under the National Firearms Act (NFA; 26 U.S.C. §§5801 et seq.). These taxes originally were set at a level intended to slow the transfer of these weapons, although the tax has not been raised since the NFA was enacted in 1934. In addition, special occupational taxes are collected from federally licensed gun dealers who manufacture, import, or sell NFA firearms. NFA-generated tax receipts are deposited into the General Fund of the Treasury. These tax receipts totaled $68.6 million in FY2016.

A variety of proposals have been advanced in recent Congresses that could affect the taxes on firearms and the uses of resulting revenues. In the 115th Congress, some legislative proposals, several of which are known as the Hearing Protection Act, would remove firearm silencers from regulation and taxation under the NFA; firearm silencers would be taxed along with pistols and revolvers at 10%, with revenues deposited into the Wildlife Restoration Trust Fund primarily in support of public target ranges. Other proposals would allow funds to be used to promote hunting and recreational shooting or for Mexican gray wolf management. Still other proposals would increase taxes on guns or ammunition, with proceeds used for gun-violence concerns (e.g., compensation to teachers who are victims of a school shooting, hiring law enforcement personnel, and neighborhood safety).

Taxes on firearms and ammunition are collected through different methods and used for different purposes, depending on the nature of the firearm. In general, taxes on the manufacture of firearms (including pistols and revolvers as well as rifles and other long guns) and ammunition are collected as excise taxes based on the manufacturer's or importer's sales price. Pursuant to the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act of 1937 (now referred to as the Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Act [P-R Act]; 16 U.S.C. §§669-669k), these revenues are allocated to the Federal Aid to Wildlife Restoration Fund, also known as the Wildlife Restoration Trust Fund, and used for wildlife restoration and for hunter safety and education purposes.

Taxes also are collected for the making and transfer of certain types of firearms and equipment (such as machine guns, short-barreled firearms, and silencers) regulated under the National Firearms Act (NFA; 26 U.S.C. §§5801 et seq.). These taxes originally were set at a level intended to slow the transfer of these weapons, but the tax has not been raised since the NFA was enacted in 1934. In addition, special occupation taxes are collected from federally licensed gun dealers who manufacture, import, or sell NFA firearms. NFA-generated tax receipts are deposited into the General Fund of the U.S. Treasury.

A variety of proposals have been advanced that could affect the taxes on firearms and the uses of resulting revenues. This report explains these taxes and discusses the uses of some of these tax receipts through the Wildlife Restoration Trust Fund. In addition, it provides information on a variety of legislative proposals that have been advanced in the current and recent Congresses and that could affect the taxes on the manufacture and transfer of firearms and ammunitions and the use of tax revenues. Specifically, this report addresses legislative proposals that would (1) modify the regulation of silencers under the NFA; (2) amend the allowed uses of the Wildlife Restoration Trust Fund; and (3) increase the tax rate for firearms.

The Excise Taxes on Firearms, Ammunition, and Archery Equipment

The P-R Act directed the proceeds of an existing federal excise tax on firearms and ammunition, under the Internal Revenue Code (26 U.S.C. §4181), to be deposited into the Wildlife Restoration Trust Fund to fund programs and grants for states and territories to use on projects that (1) benefit wildlife resources, and (2) support hunter safety and education. The excise tax predates the act, having been enacted under separate legislation and first assessed in 1919. The tax is set at 10% of the manufacturer's price for pistols and revolvers and 11% of the manufacturer's price for other firearms, shells, and cartridges.1 It is collected by the manufacturer, and it also applies to imports. In addition, an 11% tax on archery equipment is deposited into the Wildlife Restoration Trust Fund, although this tax accounts for a relatively small share of the total amount in the Fund. For this report, the excise taxes on pistols, revolvers, firearms, ammunition, and archery equipment are collectively referred to as the P-R tax. The P-R tax is applied whether or not the equipment is likely to be used for hunting.

Total collections from the firearms and ammunition taxes were $749.8 million in FY2016 and $761.6 million in FY2017. Approximately one-third of the non-archery excise tax components of the P-R tax revenues can be attributed to each major source: for FY2017, 34% of tax revenues came from pistols and revolvers, 32% from other firearms, and 33% from ammunition.2 (These amounts do not include revenues from taxes on archery equipment.) The funds collected in a given fiscal year become available for expenditure in the fiscal year following their collection.

The P-R tax has some of the same exemptions and tax-free sales that typically apply to other excise taxes: sales are tax-free to the Department of Defense and the Coast Guard, state and local governments, and nonprofit organizations, and for export or use in vessels and aircraft. Additionally, producers of fewer than 50 guns a year are exempt. There is also a personal-use exemption for manufacturers, importers, or producers who incidentally produce firearms and ammunition for their own use. There are no data on the revenue loss incurred from all the exemptions; loss due to the personal-use exemption likely would be relatively small.

The tax is currently administered by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) in the Department of the Treasury (Treasury). It was formerly administered by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF) from 1991 until the transfer of the ATF from Treasury to the Department of Justice as part of the Homeland Security Act in 2002 (P.L. 107-296). Prior to the ATF's establishment in 1972, the bureau's functions were administered by the Internal Revenue Service.3 Because the taxes are allocated to wildlife restoration and hunter education, the tax may be characterized as a use tax (to support the activities of those taxed), much like gasoline taxes that pay for roads, rather than a "sin" tax, such as those on alcohol and tobacco, which are intended to curtail use of these products.

The Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Trust Fund: Apportionment and Use

The revenues from P-R taxes go into a special account called the Federal Aid to Wildlife Restoration Fund, also known as the Wildlife Restoration Trust Fund. The fund is administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) in the Department of the Interior.4 In the P-R Act, Congress provided a permanent appropriation for the fund, to be apportioned and distributed to states and territories; P-R tax revenues are available for obligation in the fiscal year following their collection.5 Any interest that may accrue on moneys in the fund before they are expended is allocated to the North American Wetlands Conservation Fund6 rather than being retained in the P-R Trust Fund.

Apportionment of the fund (and fundable activities) is based on relevant sections of the P-R Act:

- Administration (16 U.S.C. §669c(a)(1) and 16 U.S.C. §669h). Funds may be used "only for expenses for administration that directly support the implementation of this chapter."

- Enhanced Hunter Education and Safety Grants (16 U.S.C. §669h-1). Funds may be used for the enhancement of hunter education, safety, and development programs as well as the construction or development of firearm and archery ranges.7

- Multistate Conservation Grants (16 U.S.C. §669h-2). Funds may be used for wildlife restoration projects that will benefit at least 26 states; a majority of states in an FWS region; or a regional association of state fish and game departments.

- Payments to States, for the following purposes:

- Basic Hunter Education (16 U.S.C. §669c(c)). Funds may be used for the costs related to hunter safety programs and the public target ranges as outlined in 16 U.S.C. §669g(b).

- Wildlife Restoration Programs (16 U.S.C. §669c(b)). Funds may be used to carry out wildlife restoration projects and related maintenance of completed projects.8

In most cases, any projects or activities funded through the P-R Act programs are subject to a 75% federal cost-share cap.

Types of P-R Funding

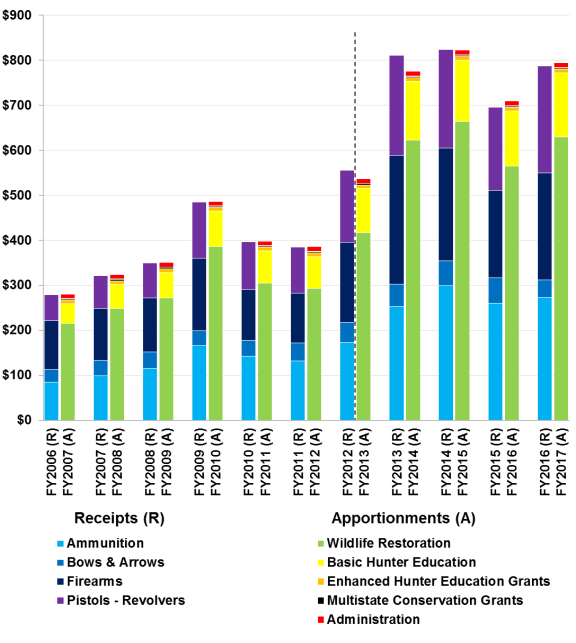

Annual apportionment of the fund is by formula. (See Figure 1 for an annual breakdown of P-R tax receipts by tax type and apportionments by program between FY2007 and FY2017.) The 50 states, as well as Guam, the Virgin Islands, American Samoa, Puerto Rico, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands are eligible to receive distributions from the fund.9 States and territories receive funds in two phases. A preliminary apportionment is made to the states and territories each October based on early data on receipts, and a final apportionment of the remainder of funds is made the following February.

FWS may deduct administrative expenses from the fund, subject to an annual cap.10 From FY2007 through FY2017, the annual average amount set aside for administrative expenses was $10.1 million (2.15% of the average annual apportionment). Additionally, the P-R Act limits the types of administrative expenses that may be charged to funding for personnel, support, and administration costs directly related to the P-R Trust Fund.11

Starting in FY2003, $8.0 million has been set aside annually for firearm and bow hunter education and safety program grants (known as Enhanced Hunter Education or Section 10 grants).12 These grants can be used to support hunter education, development, and safety activities and the construction or maintenance of public target ranges.13 From FY2007 through FY2017, Enhanced Hunter Education grants accounted for 1.72% of the average annual apportionment. These grants are distributed to the states according to a formula based on the ratio of each state's population compared to the population of all the states.14 No state can receive more than 3% or less than 1% of the total funds in the annual apportionment for Enhanced Hunter Education. Eligible territories receive a fixed percentage of the Enhanced Hunter Education set-aside.15 The federal share of costs for eligible Enhanced Hunter Education grant projects is not to exceed 75%, although the nonfederal requirement may be waived for some territories.16

A maximum of $3.0 million is set aside annually for the Multistate Conservation Grants Program.17 From FY2007 through FY2017, multistate conservation grants have accounted for 0.65% of average annual apportionments. Grants provided under this section are intended to benefit several states or a regional association of state fish and game departments.18 Multistate conservation grants can be awarded to one or more states, the FWS, or a nongovernmental organization for activities outlined in the Multistate Conservation Grant Program.

The remaining apportionments are divided between two funding programs. Funds from these programs are paid to states and together made up 95.48% of the average annual apportionment from FY2007 through FY2017.

Half of the excise tax on pistols, revolvers, bows, and arrows, but not other firearms, is allocated to states for hunter education and safety programs (known as the Basic Hunter Education or 4(c) program).19 On average, the Basic Hunter Education program received $91.4 million dollars annually from FY2007 through FY2017 (17.11% of the average annual apportionment). Apportionment for the Basic Hunter Education program is made according to the same formula as the Enhanced Hunter Education grants. The formula is based on a state's population, with upper and lower limits for states and a fixed percentage for territories.20 The federal cost share for the Basic Hunter Education apportionment is capped at 75%.

The remaining amount in the fund available for obligation in a given year is apportioned for wildlife restoration projects.21 On average, $419.6 million has been apportioned annually for wildlife restoration from FY2007 through FY2017 (78.37% of the annual apportionment on average). A small percentage—around 1%—of the wildlife restoration funding is apportioned to the eligible territories.22 The remainder of the wildlife restoration apportionment is divided in half: one-half is apportioned in proportion to the area of the state relative to the area of all states, and one-half is apportioned in proportion to the number of paid hunting licenses in the state relative to the number of paid hunting licenses in all states.23 Apportionments to the states under this section are restricted to not less than 0.5% and not more than 5% of the total amount apportioned. The federal cost share for wildlife restoration activities is capped at 75%.

Taxes and Fees Under the 1934 National Firearms Act and Gun Control Act of 1968

Two major federal statutory frameworks regulate the commerce in and possession of firearms: the 1934 National Firearms Act (NFA) and the Gun Control Act of 1968 (GCA; codified as amended at 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, §§921 et seq.). As part of the Internal Revenue Code, the NFA regulates—largely through taxation—all aspects of the manufacture and distribution of certain firearms that Congress deemed especially "dangerous and unusual" or to be the chosen weapons of "gangsters," most notably machine guns, short-barreled shotguns, and silencers.24 The GCA, by comparison, contains the principal federal restrictions on domestic commerce in firearms and ammunition not regulated under the NFA.25 The ATF administers both the GCA and the NFA.26 All ATF-collected taxes and fees are deposited into the General Fund of the Treasury. These tax receipts totaled $68.6 million in FY2016.27

The GCA requires all persons manufacturing, importing, or selling firearms as a business to be federally licensed. These license holders are commonly known as federal firearms licensees (FFLs). In addition, the GCA

- prohibits interstate firearms transfers between unlicensed persons;

- prohibits interstate sale of handguns generally;

- sets forth categories of persons to whom firearms or ammunition may not be sold, such as persons under a specified age or with criminal records;

- authorizes the Attorney General to prohibit the importation of nonsporting firearms; and

- requires that dealers maintain records of all commercial gun sales.

Manufacturers and importers of non-NFA firearms must pay an initial $150 license or renewal fee every three years. Dealers in non-NFA firearms, including pawnbrokers, pay a $200 license fee for the first three years of licensure and a $90 renewal fee every three years thereafter.

To deal in NFA firearms, an individual is required to be licensed as an FFL under the GCA and a special occupational taxpayer under the NFA.28 Federally licensed manufacturers, importers, and dealers in NFA firearms must pay an initial license or renewal fee of $3,000 every three years under the GCA. In addition, importers and manufacturers pay a special occupational tax annually (on July 1 of each year) of $1,000 under the NFA. Those manufacturers and importers whose gross receipts for the most recent taxable year are less than $500,000 pay a reduced special occupational tax. Dealers pay a special occupational tax of $500 per year. Licensees who deal exclusively with, or on the behalf of, an agency of the United States are exempted from the special occupational tax.

The NFA generally imposes a $200 "making" tax on unlicensed, private persons who build NFA firearms by either assembling a firearm from premanufactured parts or customizing an existing firearm. It also imposes a $200 transfer tax for transfers of NFA firearms to unlicensed, private persons.29 These $200 making and transfer taxes were established in statute in 1934 and have not been increased since. For non-tax-exempt transfers, the ATF places a tax stamp on the tax-paid transfer document upon the transfer's approval.30 The transferee may not take possession of the firearm until he or she holds the approved transfer document. Unlicensed, private persons who are not otherwise prohibited by law may acquire an NFA firearm in one of three ways:

- a registered owner of an NFA firearm may apply for ATF approval to transfer the firearm to another unlicensed, private person residing in the same state or to an FFL in another state;

- an individual may apply to ATF for approval to make and register an NFA firearm (except machine guns);31 or

- an individual may inherit a lawfully registered NFA firearm.

The NFA also compels the disclosure, through registration with the Attorney General, of the production and distribution system of NFA firearms from licensed manufacturer/importer to licensed dealer and from licensed dealer to unlicensed buyer.32 The ATF maintains a registry of NFA firearms known as the National Firearms Registry and Transfer Record (NFRTR). It is a felony to receive, possess, or transfer an unregistered NFA firearm.33

Legislative Proposals

This section discusses three categories of recent legislative proposals from recent Congresses. The first set of proposals, several of which are known as the Hearing Protection Act (HPA), would modify the NFA by shifting silencers out of NFA coverage and make them subject to the excise taxes that go to the Wildlife Restoration Trust Fund. The second set of proposals would expand the activities financed by the trust fund. The third set of proposals, including some proposals introduced in response to the shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, CT, in December 2012, would increase firearm excise taxes.

Proposals to Modify the Treatment of Silencers

In the 115th Congress, the HPA would remove firearm silencers from regulation under the NFA but would continue to allow for some regulation under the GCA in a manner similar to the way long guns (rifles and shotguns) are regulated under this statute. On September 18, 2017, the House Committee on Natural Resources reported the HPA as Title XV of the Sportsmen's Heritage and Recreational Enhancement Act (H.R. 3668). This bill was referred to other committees, which discharged it without further consideration. (See also H.R. 367, S. 59, and H.R. 3139 and S. 1505 for other versions of the HPA.)

Firearm silencers currently are regulated under the NFA and the GCA. Both statutes use the definition of a silencer/muffler included in the GCA. Under the GCA, the terms firearm silencer and firearm muffler mean

any device for silencing, muffling, or diminishing the report of a portable firearm, including any combination of parts, designed or redesigned, and intended for use in assembling or fabricating a firearm silencer or firearm muffler, and any part intended only for use in such assembly or fabrication.34

Firearm silencers and mufflers are also commonly known as suppressors.

Under the GCA, the term firearm means

(A) any weapon (including a starter gun) which will or is designed to or may readily be converted to expel a projectile by the action of an explosive;

(B) the frame or receiver of any such weapon; 35

(C) any firearm muffler or firearm silencer [italics added]; or

(D) any destructive device.36

H.R. 3668 would preempt any state or local government from imposing a "tax, other than a generally applicable sales or use tax, on making, transferring, using, possessing, or transporting a firearms silencer." In addition, it would prevent state and local governments from imposing any marking or recordkeeping requirements on silencers and would require ATF to destroy all records on silencers in its NFRTR.

The bill would redefine the terms firearm silencer and firearm muffler as follows:

(A) The terms "firearm silencer" and "firearm muffler" mean any device for silencing, muffling, or diminishing the report of a portable firearm, including the "keystone part" of such a device.

(B) The term "keystone part" means, with respect to a firearm silencer or firearm muffler, an externally visible part of a firearm silencer or firearm muffler, without which a device capable of silencing, muffling, or diminishing the report of a portable firearm cannot be assembled, but the term does not include any interchangeable parts designed to mount a firearm silencer or firearm muffler to a portable firearm.37

H.R. 3668 would require that FFL manufacturers and importers identify silencers by a serial number. It would amend the Internal Revenue Code to levy a 10% P-R excise tax on the making or importing of silencers.38

Proposals to Modify Pittman-Robertson Act

Several Congresses have considered proposals to amend the P-R Act. Typically, bills have been proposed that would add new purposes to the act, provide for selected activities to qualify for P-R funding, or adjust the federal cost share on existing funding programs. These proposals have been introduced as stand-alone legislation in both the House and the Senate and have been included within larger legislative vehicles.

In the 115th Congress, S. 593, S. 733, S. 1460, S. 1514, H.R. 788, H.R. 3668, and H.R. 4489 all would allow U.S. states and territories to use more of the funds distributed under the P-R Act for public target-range projects for the purposes of land acquisition, expansion, and construction by adjusting the federal cost-share cap on these activities.39 Similar language to amend sections of the P-R Act related to public target-range construction and expansion activities was introduced in the 114th Congress in S. 405, S. 659, S. 721, S. 992, S. 2012, and H.R. 2406.40

All of the bills under consideration in the 115th Congress would adjust the federal cost-share limit for construction, expansion, and land acquisition associated with public shooting ranges for both the Basic and Enhanced Hunter Education components of the bill. Under current law, the maximum federal cost share related to public shooting ranges is capped at 75% for activities related to construction, operation, maintenance, development, and updating activities.41 These bills would increase the federal cost-share cap to 90% for land acquisition, expansion, and construction related to ranges, and they would leave range operation and other activities capped at 75%.

Each of these bills would amend 16 U.S.C. §669g(b) to include the following language:

Exception.—Notwithstanding the limitation described in paragraph (1), a State may pay up to 90 percent of the cost of the land for, expanding, or constructing a public target range.42

The way this provision is written may be subject to different interpretations. For instance, it could be interpreted to mean that a state is limited to pay a maximum of 90% of the cost of the land acquisition related to, the construction, or the expansion of a target range (i.e., placing a cap on state contributions). Alternatively, it may be interpreted to mean that federal funds apportioned under the referenced section can be used for up to 90% of the cost of land acquisition, expansion, and construction, thereby adjusting the maximum contribution of the federal cost share.

In addition, these bills would allow states to access up to 10% of the funds made available to supplement enhanced education and safety grant money for land acquisition, construction, or expansion of a target range. These bills also would extend the deadline for using grant money for land acquisition, construction, and expansion related to a target range from within the same fiscal year to five fiscal years.

In addition to amending funding parameters related to target ranges, these bills all state the sense of Congress that the U.S. Forest Service (in the Department of Agriculture) and the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (in the Department of the Interior) should cooperate with state and local authorities to carry out waste-removal activities at public target ranges on federal lands. S. 593, H.R. 788, and H.R. 3668 also would include language on "limits on liability." This language would provide that "any action by an agent or employee of the United States" related to the management of federal land for target-shooting purposes is a discretionary function.43 The limits on liability also would extend to exempting the United States from civil action or claim "for money damages for any injury to or loss of property, personal injury, or death caused by an activity occurring at a public target range that is" funded by the P-R Act or on federal land.

Other legislation in the 115th Congress (S. 1613 and H.R. 2591) would broaden the purposes of the P-R Act to include extending financial and technical assistance to states to promote hunting and recreational shooting.44 The bills would amend the P-R Act to allow for funding hunter and recreational shooter recruitment and retention activities through wildlife restoration programs, Basic Hunter Education, and Enhanced Hunter Education grant funding. These bills also would amend the Multistate Conservation Grant Program section45 within the P-R Act to provide up to $5 million of revenues deposited into the Wildlife Restoration Trust Fund from archery-related excise taxes for grants to support hunter and recreational shooter recruitment. Similar legislation was introduced in the 114th Congress (S. 2690 and H.R. 4818).

Other legislative proposals have been introduced in the 114th and 115th Congresses that relate to the P-R Act. In the 115th Congress, S. 368 would provide that state wildlife authorities would be eligible for funding allocated from the P-R fund for the purpose of Mexican gray wolf management. An identical provision was included in S. 2876 in the 114th Congress. Also in the 114th Congress, H.R. 5650 would have transferred revenues from energy and mineral development on federal lands and outer continental shelves to a subaccount in the P-R Fund. Beginning in FY2016, this bill would have transferred $1.3 billion annually to be used for the management of "fish and wildlife species of greatest conservation need."46

In the 114th Congress, several bills were introduced to extend the date after which interest earned on obligations held in the P-R fund would become available for apportionment under the P-R Act. Extension of this date would have ensured that interest earned on the P-R Fund would remain available for the North American Wetlands Conservation Fund. Some bills would have extended this date from FY2016 by one year (S. 1645 and S. 2132), whereas others would have extended it to FY2026 (S. 722 and H.R. 2345). The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113), which was signed into law on December 18, 2015, extended the interest availability to FY2026.

Proposals to Increase Taxes

Other proposals in recent Congresses would increase taxes on firearms. In the 115th Congress, H.R. 167 would increase excise taxes on ammunition from 11% to 13% and would allocate the increase in revenues due to the additional 2% rate to the Teacher Victims Family Trust, with the proceeds used to provide assistance to the immediate family of a teacher or other school employee killed in an act of violence while performing school duties. Representatives Pascrell and Danny K. Davis announced the reintroduction of the Gun Violence Prevention and Safe Communities Act introduced as H.R. 4214 in the 114th Congress (see description below).47

H.R. 3668 proposes to move silencers out of coverage under the NFA and would extend the 10% P-R Act tax to silencers (see "Proposals to Modify the Treatment of Silencers"). This approach would lower tax receipts overall from the NFA but would increase revenues accruing to the P-R fund.

In the 114th Congress, the Gun Violence and Safe Communities Act (H.R. 4214) would have increased excise taxes on firearms from 10% for pistols and revolvers and 11% for other firearms to 20% (see "The Excise Taxes"), added lower frames or receivers to the definition of firearms (components not currently subject to the tax),48 and increased the excise tax on shells and cartridges from 11% to 50%. The additional revenues from this change would have been allocated as follows: 35% for hiring law enforcement personnel, 35% for Project Safe Neighborhoods, 10% for Centers for Disease Control National Center for Injury Prevention and Control research on gun violence and prevention, 5% for the National Criminal History Improvement Program, 5% for the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) Act Record Improvement Program, 5% for Community-Based Violence Prevention, and 5% for schools to implement strategies to improve school discipline.

The bill also would have doubled occupational taxes (currently $1,000 a year for importers and manufacturers, $500 for dealers, and $500 for small importers and manufacturers; see "Taxes and Fees Under the 1934 National Firearms Act and Gun Control Act of 1968") and would have included an adjustment for inflation. It would have increased the transfer tax on firearms from $200 to $500 and the tax on other weapons from $5 to $100, also adjusting for inflation. It would have reclassified a semiautomatic pistol chambered for cartridges commonly considered rifle rounds, configured with receivers often associated with rifles and capable of accepting detachable magazines, as a firearm subject to the $500 transfer tax. A similar bill also was introduced in the 113th Congress as H.R. 3018.

Also in the 114th Congress, H.R. 3830 would have imposed an additional tax of $100 on the sale of a firearm, with 50% of the proceeds used for block grants for community mental health services and the other 50% to carry out Subpart 1 of Part E of the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act (P.L. 90-351). The bill also would have directed that regulations require a passive identification capability, which enables a firearm to be identified by a mobile or fixed reading device. In addition, it would have established a database in ATF of firearms reported lost or stolen.

In the 113th Congress, H.R. 793 would have imposed a 10% retail tax on any concealable firearm. It also would have provided grants to buy back firearms (handled by state, local, or tribal governments), financed by these new revenues (a fixed additional amount of $1 million would have been authorized for the first fiscal year).

None of the legislative proposals to increase taxes saw further action in the 113th or 114th Congresses.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Certain weapons and manufacturers are subject to separate taxes based on the National Firearms Act (NFA; 26 U.S.C. §§5801 et seq.) and subsequent legislation. These are rare weapons that, in private hands, are older collectibles. The regulation of these weapons is by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF). The collected amounts appear inconsequential. |

| 2. |

Taxes are collected by the U.S. Department of the Treasury's Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB). Data on total collections are at https://www.ttb.gov/tax_audit/tax_collections.shtml. Data on the distribution of taxes between pistols and revolvers, other firearms, and ammunition are found in Frequently Requested FOIA Documents at https://www.ttb.gov/foia/err.shtml. The data in three sources: directly in the TTB calculations, in the special data on allocation by type, and in the share received by the fund, reflect differences in timing, in amounts before and after adjustments, as well as the archery tax. These collections fluctuate substantially from one year to another. |

| 3. |

Under the Homeland Security Act, Congress established the TTB at Treasury. The TTB generally consists of those administrative units charged with regulating alcohol and tobacco products that previously were housed in ATF. In the act, Congress also changed the title of ATF to include explosives—the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (still ATF)—and transferred the bureau to the Department of Justice (DOJ). Although ATF remains responsible for most aspects of regulating and enforcing firearms and explosives laws, as well as for enforcing some aspects of alcohol and tobacco laws, Congress charged TTB with administering the P-R firearms and ammunition excise tax provisions. |

| 4. |

For further information about the Wildlife Restoration Trust Fund, see U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Program, "Wildlife Restoration Program–Funding," at http://wsfrprograms.fws.gov/Subpages/GrantPrograms/WR/WR_Funding.htm. |

| 5. |

16 U.S.C. §§669-669k. |

| 6. |

16 U.S.C. §669b(b). These funds are to be used for wetland conservation projects (see 16 U.S.C. §4407 for additional allocation information). For more information about the North American Wetlands Conservation Act, see FWS, "North American Wetlands Conservation Act," at https://www.fws.gov/birds/grants/north-american-wetland-conservation-act.php. |

| 7. |

Allowed uses of Enhanced Hunter Education and Safety grants are determined based on whether a state has used all funding provided under 16 U.S.C. §669c(c). If a state has not used all such funding, it is restricted to funding certain projects outlined in the text. If it has used all of those funds, Enhanced Hunter Education and Safety grant funding may be used for any use authorized under the chapter. |

| 8. |

Wildlife restoration project is defined in the P-R Act as the selection, restoration, rehabilitation, and improvement of areas of land or water adaptable as feeding, resting, or breeding places for wildlife, including acquisition of such areas or estates or interests therein as are suitable or capable of being made suitable therefor, and the construction thereon or therein of such works as may be necessary to make them available for such purposes and also including such research into problems of wildlife management as may be necessary to efficient administration affecting wildlife resources, and such preliminary or incidental costs and expenses as may be incurred in and about such projects (16 U.S.C. §669a). |

| 9. |

Washington, D.C., is not eligible for apportionment. |

| 10. |

16 U.S.C. §669c(a)(1). Since FY2004, the cap on administration expenses has been tied to the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers published by the Department of Labor (16 U.S.C. §669c). Prior to FY2004, the Fish and Wildlife Programs Improvement and National Wildlife Refuge System Centennial Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-408) provided that the set-aside for administrative expenses not exceed $8.2 million in FY2003 and $9 million in both FY2002 and FY2001. |

| 11. |

The limitations in types of allowed administration expenses are outlined at 16 U.S.C. §669h. |

| 12. |

16 U.S.C. §669h-1; P.L. 106-408. $7.5 million was set aside for Enhanced Hunter Education grants in FY2001 and FY2002. |

| 13. |

The amount set aside for Enhanced Hunter Education grants has varied slightly since FY2013 due to the sequester pursuant to the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act, as amended (2 U.S.C. §§900 et seq.). |

| 14. |

Apportionment is structured in the same way as the Basic Hunter Education program as provided in 16 U.S.C. §669c(c). Population is based on the last census figures. See U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, "Wildlife Restoration Program Funding Flowchart," at https://fawiki.fws.gov/display/TRNG/WSFR+Funding+Flowcharts?preview=/37060948/37060963/Wildlife%20Restoration%20Program%20Funding%20Flowchart.pdf. |

| 15. |

Guam, the Virgin Islands, American Samoa, Puerto Rico, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands each receive 0.17% of the total allocation. |

| 16. |

The waiver provision for territories is found in 48 U.S.C. §1469a(d). U.S. territories eligible for the waiver are American Samoa, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, and the Virgin Islands. Puerto Rico is not eligible for the waiver. |

| 17. |

The P-R Act was amended to include the Multistate Conservation Grant Program section (16 U.S.C. §669h-2) on November 1, 2000, by P.L. 106-408. The amount set aside for multistate conservation grants has varied slightly since FY2013 due to the sequester pursuant to the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act, as amended (2 U.S.C. §900 et seq.). |

| 18. |

For a project to be eligible for a grant under this section, benefits from the project must accrue to at least 26 states; a majority of states within an FWS region; or a regional association of state fish and game departments. |

| 19. |

The funding for this program is allocated pursuant to 16 U.S.C. §669c(c). 16 U.S.C. §669g outlines allowable uses for the funding. |

| 20. |

The formula is based on population and is limited to not more than 3% and not less than 1% of the total funding for each state. Guam, the Virgin Islands, American Samoa, Puerto Rico, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands each receive 0.17% of the total allocation. |

| 21. |

See "The Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Trust Fund: Apportionment and Use," above, for more information on wildlife restoration projects. |

| 22. |

Pursuant to 16 U.S.C. §669g-1. Puerto Rico receives not more than 0.5%, and Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, American Samoa, and Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands each receive 0.17% of the total funds apportioned. |

| 23. |

This formula does not distinguish between in-state and out-of-state hunters. A hunting license purchased by a nonresident would count the same under this formula as one purchased by a resident. Each state's fish and game department is responsible for reporting the number of hunting-license holders in a given year. |

| 24. |

The other firearms regulated under the NFA include destructive devices (e.g., grenades and firearms with barrel bores of greater than one-half inch) and certain concealable firearms under the term any other weapon (e.g., pen, cane, and belt-buckle guns). For further information, see DOJ, ATF, National Firearms Act Handbook, ATF E-Publication 5320.8, April 2009, p. 16-19. |

| 25. |

The Gun Control Act of 1968 (GCA; codified as amended at 18 U.S.C. Chapter 44, §§921 et seq.) was preceded by the Federal Firearms Act of 1938 (FFA; P.L. 75-585; June 30, 1938; 52 Stat. 1240). The FFA, in some ways, was very similar and parallel to the GCA with regard to imposing licensing and recordkeeping requirements on firearms manufacturers, importers, and dealers. The GCA repealed the FFA. In addition, Title II of the GCA amended and recodified the NFA. With the exception of antique firearms and replicas of such firearms, the GCA regulates all firearms not regulated under the NFA. Under the GCA, the term handgun means a firearm with a short stock that is designed to be fired using a single hand (see 18 U.S.C. §921(a)(29)). The term long gun generally refers to shotguns and rifles (see 18 U.S.C. §§921(a)(5) and (7)). Long guns are intended to be fired from the shoulder; hence, long-gun designs usually include a shoulder stock and longer barrels to improve accuracy and range. Under current law, a shotgun with a barrel of less than 18 inches or a rifle with a barrel of less than 16 inches, and either firearm with an overall length of less than 26 inches, is a short-barreled shotgun or a short-barreled rifle, respectively. As noted above, those firearms are regulated under the NFA. |

| 26. |

ATF was originally established as a stand-alone bureau in the Department of the Treasury (Treasury) in 1972 by Treasury Department Order No. 120-1. As part of the Homeland Security Act, Congress transferred ATF's enforcement and regulatory functions for firearms and explosives to DOJ from Treasury, adding "explosives" to ATF's title. See P.L. 107-296, 116 Stat. 2135, November 25, 2002, §1111 (effective January 24, 2003). The regulatory aspects of alcohol and tobacco commerce are the domain of the TTB, which encompasses former components of ATF that remained at Treasury when the components of ATF described above were transferred to DOJ. |

| 27. |

DOJ, ATF, Firearms Commerce in the United States Annual Statistical Update 2017, September 2017, p. 11. |

| 28. |

Class I special occupational taxpayers (SOTs) are importers of NFA firearms, Class II SOTs are manufacturers of NFA firearms, and Class III SOTs are dealers. NFA firearms often are referred to as Class III weapons, for Class III dealers. |

| 29. |

Transfers of NFA-covered firearms incur a tax of $200, except for those classified as "any other weapon[s]," which are taxed at a reduced $5 rate. |

| 30. |

Certain NFA firearm transfers are tax-exempt. They include transfers to a lawful heir from an estate, transfers between federal firearms licensees who are also SOTs, and transfers of "unserviceable firearms." |

| 31. |

Under the Firearms Owners' Protection Act of 1986 (P.L. 99-308, §102(9); 100 Stat. 449, 452-453; codified at 18 U.S.C. §922(o)), Congress banned the transfer or possession of any machine gun that was not lawfully possessed before the date of enactment (May 19, 1986). Exemptions were provided in this provision for machine guns held under the authority of any department or agency of the U.S. government or any department, agency, or political subdivision of a state. According to one estimate, as of November 2007, approximately 182,600 machine guns were available for transfer to civilians in the United States. See John Brown, "182,619—Is That All There Is," Small Arms Review, vol. 13, no. 9 (June 2010) p. 22. |

| 32. |

The GCA generally prohibits the importation of NFA firearms. |

| 33. |

26 U.S.C. §§5861(d) and (j). |

| 34. |

18 U.S.C. §921(a)(24). |

| 35. |

At 27 C.F.R. §478.11, the term firearm frame or receiver is defined as "that part of a firearm which provides housing for the hammer, bolt or breechblock, and firing mechanism, and which is usually threaded at its forward portion to receive the barrel." |

| 36. |

18 U.S.C. §921(a)(3). |

| 37. |

H.R. 3668, §1506. |

| 38. |

H.R. 3668, Title XV. |

| 39. |

These bills also would amend the P-R Act to include that a public target range is defined as a location identified by a government agency for recreational shooting that is open to the public; may be supervised; and can accommodate archery or rifle, pistol, or shotgun shooting. |

| 40. |

S. 405 was placed directly on the Senate Legislative Calendar on February 5, 2015. S. 659 was reported by the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works on February 24, 2016. S. 2012 was considered in conference between the House of Representatives and the Senate; conference agreed to by the Senate on July 12, 2016. H.R. 2406 passed out of the House of Representatives on February 26, 2016. |

| 41. |

See 16 U.S.C. §669g (Basic Hunter Education funding) and 16 U.S.C. §669h-1 (Enhanced Hunter Education grants). |

| 42. |

S. 593 (§4), S. 733 (§401), S. 1460 (§8401), S. 1514 (§2), H.R. 788 (§4), H.R. 3668 (§203), and H.R. 4489 (§1103). |

| 43. |

The discretionary function exception of the Federal Tort Claims Act prevents the government from being sued for "any claim ... based upon the exercise or performance or the failure to exercise or perform a discretionary function or duty on the part of a federal agency or an employee of the government, whether or not the discretion involved be abused." See 28 U.S.C. §2680(a). |

| 44. |

These bills also would define hunter recruitment and recreational shooter recruitment as an activity to recruit or retain hunters and recreational shooters. |

| 45. |

16 U.S.C. §669h-2. |

| 46. |

H.R. 5650, Recovering America's Wildlife Act of 2016, Section 3. |

| 47. |

See press release at https://pascrell.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/pascrell-and-davis-re-introduce-gun-violence-prevention-and-safe. |

| 48. |

The frame or receiver is the part of a firearm that houses the trigger assembly, hammer, bolt and carrier, firing mechanism, and a magazine well for multiple-shot firearms. For some firearm designs, the receiver may consist of more than one part. For AR-15 type firearms, for example, the receiver consists of a lower and an upper. AR-15 type lower and upper receivers are available for transfer in the United States to civilians, who often build customized handguns or rifles from such components. For purposes of implementing the GCA, the ATF has ruled that the lower receiver is the core component of the firearm. As such, federally licensed firearms manufacturers and importers must mark each lower receiver with an embossed or engraved serial number and a manufacturer's or importer's stamp. In addition, whenever a federally licensed firearms dealer intends to transfer a lower receiver to any person who is not a federally licensed dealer, manufacturer, or importer, the dealer must initiate a background check through the National Instant Criminal History Background Check System (NICS) for the intended transferee under 18 U.S.C. §922(t). The P-R Act tax is paid on firearm receivers that are manufactured as a single unit, but it is not paid on AR-15 type lower receivers or upper receivers, unless those parts are manufactured or imported as part of a complete, fully assembled firearm. |