Grazing Fees: Overview and Issues

Charging fees for grazing private livestock on federal lands is a long-standing but contentious practice. Generally, livestock producers who use federal lands want to keep fees low, whereas conservation groups believe fees should be increased. The current formula for determining the grazing fee for lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the Forest Service (FS) was established in the Public Rangelands Improvement Act of 1978 (PRIA) and continued by a 1986 executive order issued by President Reagan. The fee is based on grazing of a specified number of animals for one month, known as an animal unit month (AUM). The fee is set annually under a formula that uses a base value per AUM. The base value is adjusted by three factors—the lease rates for grazing on private lands, beef cattle prices, and the cost of livestock production.

For 2019, BLM and FS are charging a grazing fee of $1.35 per AUM. This fee is in effect from March 1, 2019, through February 29, 2020, and is the minimum allowed. Since 1981, when BLM and FS began charging the same grazing fee, the fee has ranged from $1.35 per AUM (for about half the years) to $2.31 per AUM (for 1981). The average fee during the period was $1.55 per AUM. In recent decades, grazing fee reform has occasionally been considered by Congress or proposed by the President, but no fee changes have been adopted.

The grazing fees collected by each agency essentially are divided between the agency, Treasury, and states/localities. The agency portion is deposited in a range betterment fund in the Treasury and is subject to appropriation by Congress. The agencies use these funds for on-the-ground activities, such as range rehabilitation and fence construction. Under law, BLM and FS allocate the remaining collections differently between the Treasury and states/localities.

Issues for Congress include whether to retain the current grazing fee or alter the charges for grazing on federal lands. The current BLM and FS grazing fee is generally lower than fees charged for grazing on state and private lands. Comparing the BLM and FS fee with state and private fees is complicated, due to factors including the purposes for which fees are charged, the quality of the resources on the lands being grazed, and whether the federal grazing fee alone or other nonfee costs are considered.

Unauthorized grazing occurs on BLM and FS lands in a variety of ways, including when cattle graze outside the allowed areas or seasons or in larger numbers than allowed under permit. In some cases, livestock owners have intentionally grazed cattle on federal land without getting a permit or paying the required fee. The agencies have responded at times by fining the owners, as well as by impounding and selling the trespassing cattle. BLM continues to seek a judicial resolution to a long-standing controversy involving cattle grazed by Cliven Bundy on lands in Nevada.

There have been efforts to end livestock grazing in specific areas through voluntary retirement of permits and leases and subsequent closure of the allotments to grazing. Congress has enacted some such proposals. Congress also has considered measures to reduce or end grazing in specified states or to allow a maximum number of permits to be waived yearly. Among other reasons, such measures have been supported to protect range resources but opposed as diminishing ranching operations.

Another issue involves expiring grazing permits. Both BLM and FS have a backlog of permits needing evaluation for renewal. To allow for continuity in grazing operations, P.L. 113-291 made permanent the automatic renewal (until the evaluation process is complete) of permits and leases that expire or are transferred. The law provided that the issuance of a grazing permit “may” be categorically excluded from environmental review under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) under certain conditions. NEPA categorical exclusions have been controversial.

Grazing Fees: Overview and Issues

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Current Grazing Fee Formula and Distribution of Receipts

- The Fee Formula

- Distribution of Receipts

- History of Fee Evaluation and Reform Attempts

- Current Issues

- Fee Level

- State and Private Grazing Fees

- Grazing Without Paying Fees

- Voluntary Permit Retirement

- Extension of Expiring Permits

Figures

Summary

Charging fees for grazing private livestock on federal lands is a long-standing but contentious practice. Generally, livestock producers who use federal lands want to keep fees low, whereas conservation groups believe fees should be increased. The current formula for determining the grazing fee for lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the Forest Service (FS) was established in the Public Rangelands Improvement Act of 1978 (PRIA) and continued by a 1986 executive order issued by President Reagan. The fee is based on grazing of a specified number of animals for one month, known as an animal unit month (AUM). The fee is set annually under a formula that uses a base value per AUM. The base value is adjusted by three factors—the lease rates for grazing on private lands, beef cattle prices, and the cost of livestock production.

For 2019, BLM and FS are charging a grazing fee of $1.35 per AUM. This fee is in effect from March 1, 2019, through February 29, 2020, and is the minimum allowed. Since 1981, when BLM and FS began charging the same grazing fee, the fee has ranged from $1.35 per AUM (for about half the years) to $2.31 per AUM (for 1981). The average fee during the period was $1.55 per AUM. In recent decades, grazing fee reform has occasionally been considered by Congress or proposed by the President, but no fee changes have been adopted.

The grazing fees collected by each agency essentially are divided between the agency, Treasury, and states/localities. The agency portion is deposited in a range betterment fund in the Treasury and is subject to appropriation by Congress. The agencies use these funds for on-the-ground activities, such as range rehabilitation and fence construction. Under law, BLM and FS allocate the remaining collections differently between the Treasury and states/localities.

Issues for Congress include whether to retain the current grazing fee or alter the charges for grazing on federal lands. The current BLM and FS grazing fee is generally lower than fees charged for grazing on state and private lands. Comparing the BLM and FS fee with state and private fees is complicated, due to factors including the purposes for which fees are charged, the quality of the resources on the lands being grazed, and whether the federal grazing fee alone or other nonfee costs are considered.

Unauthorized grazing occurs on BLM and FS lands in a variety of ways, including when cattle graze outside the allowed areas or seasons or in larger numbers than allowed under permit. In some cases, livestock owners have intentionally grazed cattle on federal land without getting a permit or paying the required fee. The agencies have responded at times by fining the owners, as well as by impounding and selling the trespassing cattle. BLM continues to seek a judicial resolution to a long-standing controversy involving cattle grazed by Cliven Bundy on lands in Nevada.

There have been efforts to end livestock grazing in specific areas through voluntary retirement of permits and leases and subsequent closure of the allotments to grazing. Congress has enacted some such proposals. Congress also has considered measures to reduce or end grazing in specified states or to allow a maximum number of permits to be waived yearly. Among other reasons, such measures have been supported to protect range resources but opposed as diminishing ranching operations.

Another issue involves expiring grazing permits. Both BLM and FS have a backlog of permits needing evaluation for renewal. To allow for continuity in grazing operations, P.L. 113-291 made permanent the automatic renewal (until the evaluation process is complete) of permits and leases that expire or are transferred. The law provided that the issuance of a grazing permit "may" be categorically excluded from environmental review under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) under certain conditions. NEPA categorical exclusions have been controversial.

Introduction

Charging fees for grazing private livestock on federal lands is statutorily authorized and has been the policy of the Forest Service (FS, Department of Agriculture) since 1906, and of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM, Department of the Interior) since 1936. Today, fees are charged for grazing on BLM and FS land basically under a fee formula established in the Public Rangelands Improvement Act of 1978 (PRIA) and continued administratively.1

BLM manages a total of 245.7 million acres, primarily in the West. Of total BLM land, 154.1 million acres were available for livestock grazing in FY2017.2 The acreage used for grazing during 2017 was 138.7 million acres.3 FS manages a total of 192.9 million acres. Although this land is predominantly in the West, FS manages more than half of all federal lands in the East.4 Of total FS land, more than 93 million acres were available for grazing in FY2017, with 74 million used for livestock grazing.5 For both agencies, the acreage available for livestock grazing reflects lands within grazing allotments. However, the acreage in those allotments that is capable of forage production is substantially less, according to the FS, because some lands lack forage (e.g., are forested or contain rockfalls). In addition, for both agencies, acreage used for grazing is less than the acreage available due to voluntary nonuse for economic reasons, resource protection needs, and forage depletion caused by drought or fire, among other reasons. Because BLM and FS are multiple-use agencies, lands available for livestock grazing generally are also available for other purposes.

On BLM rangelands, in FY2017, there were 16,357 operators authorized to graze livestock, and they held 17,886 grazing permits and leases.6 Under these permits and leases, a maximum of 12,333,568 animal unit months (AUMs) of grazing potentially could have been authorized for use. Instead, 8,820,617 AUMs were authorized for use.7 BLM defines an AUM, for fee purposes, as a month's use and occupancy of the range by one animal unit, which includes one yearling, one cow and her calf, one horse, or five sheep or goats.8

On FS rangelands, in FY2017, there were 5,725 permit holders permitted (i.e., allowed) to graze commercial livestock, with a total of 6,146 active permits. A maximum of 8,238,429 head-months (HD-MOs) of grazing were under permit and thus potentially could have been authorized for use. Instead, 6,803,425 HD-MOs were authorized for use.9 FS uses HD-MO as its unit of measurement for use and occupancy of FS lands. This measurement is nearly identical to AUM as used by BLM for fee purposes.10 Hereinafter, AUM is used to cover both HD-MO and AUM.

BLM and FS are charging a 2019 grazing fee of $1.35 per AUM. This annual fee is in effect from March 1, 2019, through February 29, 2020. This is the minimum fee allowed. (See "The Fee Formula" section, below.) BLM and FS typically spend more managing their grazing programs than they collect in grazing fees.11 For example, $79.0 million was appropriated to BLM for rangeland management in FY2017. Of that amount, $32.4 million was used for administration of livestock grazing, according to the agency. The remainder was used for other range activities, including weed management, habitat improvement, and water development. For the same fiscal year, BLM collected $18.3 million in grazing fees.12 The FY2017 appropriation for FS for grazing management was $56.9 million. The funds are used primarily for grazing permit administration and planning.13 FS collected $7.6 million in grazing fees during FY2017.14

Grazing fees have been contentious since their introduction. Generally, livestock producers who use federal lands want to keep fees low. They assert that federal fees are not comparable to fees for leasing private rangelands because public lands often are less productive; must be shared with other public users; and often lack water, fencing, or other amenities, thereby increasing operating costs. They fear that fee increases may force many small and medium-sized ranchers out of business. Conservation groups generally assert that low fees contribute to overgrazing and deteriorated range conditions. Critics assert that low fees subsidize ranchers and contribute to budget shortfalls because federal fees are lower than private grazing land lease rates and do not cover the costs of range management. They further contend that, because some of the collected fees are used for range improvements, higher fees could enhance the productive potential and environmental quality of federal rangelands.

Current Grazing Fee Formula and Distribution of Receipts

The Fee Formula

The fee charged by BLM and FS is based on the grazing on federal rangelands of a specified number of animals for one month. PRIA establishes a policy of charging a grazing fee that is "equitable" and prevents economic disruption and harm to the western livestock industry. The law requires the Secretaries of Agriculture and the Interior to set a fee annually that is the estimated economic value of grazing to the livestock owner. The fee is to represent the fair market value of grazing, beginning with a 1966 base value of $1.23 per AUM. This value is adjusted for three factors based on costs in western states of (1) the rental charge for pasturing cattle on private rangelands, (2) the sales price of beef cattle, and (3) the cost of livestock production. Congress also established that the annual fee adjustment could not exceed 25% of the previous year's fee.15

PRIA required a seven-year trial (1979-1985) of the formula while BLM and FS undertook a study to help Congress determine a permanent fee or fee formula. President Reagan issued Executive Order 12548 (February 14, 1986) to continue indefinitely the PRIA fee formula, and established the minimum fee of $1.35 per AUM.16

The 2019 grazing fee of $1.35 per AUM represents a 4% decrease from the 2018 fee. Since 1981, BLM and FS have been charging the same fee, as shown in Table 1. The fee has ranged from $1.35 per AUM (for about half of the years during the 39-year period) to $2.31 per AUM (for 1981). The fee averaged $1.55 per AUM over the period.

|

1981.....................$2.31 |

1991.....................$1.97 |

2001.....................$1.35 |

2011.....................$1.35 |

|

1982.....................$1.86 |

1992.....................$1.92 |

2002.....................$1.43 |

2012.....................$1.35 |

|

1983.....................$1.40 |

1993.....................$1.86 |

2003.....................$1.35 |

2013.....................$1.35 |

|

1984.....................$1.37 |

1994.....................$1.98 |

2004.....................$1.43 |

2014.....................$1.35 |

|

1985.....................$1.35 |

1995.....................$1.61 |

2005.....................$1.79 |

2015.....................$1.69 |

|

1986.....................$1.35 |

1996.....................$1.35 |

2006.....................$1.56 |

2016.....................$2.11 |

|

1987.....................$1.35 |

1997.....................$1.35 |

2007....................$1.35 |

2017....................$1.87 |

|

1988.....................$1.54 |

1998.....................$1.35 |

2008.....................$1.35 |

2018....................$1.41 |

|

1989.....................$1.86 |

1999.....................$1.35 |

2009.....................$1.35 |

2019....................$1.35 |

|

1990.....................$1.81 |

2000.....................$1.35 |

2010.....................$1.35 |

Sources: Data for 1981-2005 are primarily derived from p. 83 of a 2005 Government Accountability Office report, GAO-05-869, at https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-05-869. Data for 2006-2019 are primarily derived from annual BLM press releases. See for instance the 2019 press release containing the 2019 fee, at https://www.blm.gov/press-release/blm-and-forest-service-grazing-fees-lowered-2019.

Distribution of Receipts

Fifty percent of grazing fees collected by each agency, or $10.0 million—whichever is greater—go to a range betterment fund in the Treasury. BLM and FS grazing receipts are deposited separately.17 Monies in the fund are subject to appropriations. BLM typically has requested and received an annual appropriation of $10.0 million for the fund. FS generally requests and receives an appropriation that is less than the $10.0 million minimum authorized in law. For instance, for FY2017, the agency received an appropriation of $4.2 million, roughly half the fees collected.18

The agencies use the range betterment fund for range rehabilitation, protection, and improvement, including grass seeding and reseeding, fence construction, weed control, water development, and fish and wildlife habitat. Under law, one-half of the fund is to be used as directed by the Secretary of the Interior or of Agriculture, and the other half is authorized to be spent in the district, region, or forest that generated the fees, as the Secretary determines after consultation with user representatives.19 Agency regulations contain additional detail. For example, BLM regulations provide that half of the fund is to be allocated by the Secretary on a priority basis, and the rest is to be spent in the state and district where derived. Forest Service regulations provide that half of the monies are to be used in the national forest where derived, and the rest in the FS region where the forest is located. In general, FS returns all range betterment funds to the forest that generated them.20

|

|

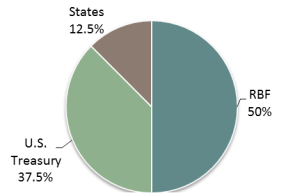

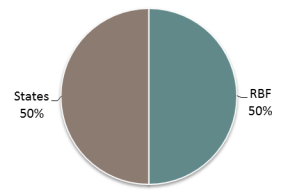

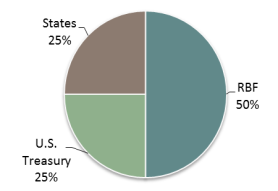

Source: CRS. Note: RBF = Range Betterment Fund. |

The agencies allocate the remaining 50% of the collections differently.21 For FS, 25% of the funds are deposited in the Treasury and 25% are subject to revenue-sharing requirements. The revenue-sharing payments are made to states, but the states do not retain any of the funds. The states pass the funds to specified local governmental entities for use at the county level (16 U.S.C. §500; see Figure 1).22 For BLM, states receive 12.5% of monies collected from lands defined in Section 3 of the Taylor Grazing Act and 37.5% is deposited in the Treasury.23 Section 3 lands are those within grazing districts for which BLM issues grazing permits. (See Figure 2.) By contrast, states receive 50% of fees collected from BLM lands defined in Section 15 of the Taylor Grazing Act. Section 15 lands are those outside grazing districts for which BLM leases grazing allotments. (See Figure 3.) For both agencies, any state share is to be used to benefit the counties that generated the receipts.

|

|

|

History of Fee Evaluation and Reform Attempts

PRIA directed the Interior and Agriculture Secretaries to report to Congress, by December 31, 1985, on the results of their evaluation of the fee formula and other grazing fee options and their recommendations for implementing a permanent grazing fee. The Secretaries' report included (1) a discussion of livestock production in the western United States; (2) an estimate of each agency's cost for implementing its grazing programs; (3) estimates of the market value for public rangeland grazing; (4) potential modifications to the PRIA formula; (5) alternative fee systems; and (6) economic effects of the fee system options on permittees.24 A 1992 revision of the report updated the appraised fair market value of grazing on federal rangelands, determined the costs of range management programs, and recalculated the PRIA base value through the application of economic indexes. The study results, criticized by some as using faulty evaluation methods, were not adopted.

In the 1990s, grazing fee reform was considered by Congress but no change was enacted. In particular, in the 104th Congress (1995-1996), the Senate passed a bill to establish a new grazing fee formula and alter rangeland regulations. The formula was to be derived from the three-year average of the total gross value of production for beef and no longer indexed to operating costs and private land lease rates, as under PRIA. By one estimate, the measure would have resulted in an increase of about $0.50 per AUM. In the 105th Congress (1997-1998), the House passed a bill with a fee formula based on a 12-year average of beef cattle production costs and revenues. The formula would have resulted in a 1997 fee of about $1.84 per AUM. Since the 1990s, it appears that no major bills to alter the grazing fee have passed the chambers.

Also in the 1990s—and in subsequent years—certain Presidents proposed changes to grazing fees and related policies. However, these changes were not adopted. As one example, in 1993, the Clinton Administration proposed an administrative increase in the fee and revisions of other grazing policies. The proposed fee formula started with a base value of $3.96 per AUM and was to be adjusted to reflect annual changes in private land lease rates in the West (called the Forage Value Index). The current PRIA formula is adjusted using multiple indexes. As a second example, for some fiscal years (e.g., FY2008), President George W. Bush proposed terminating the deposit of 50% of BLM's grazing fees into the range betterment fund. The fee collections would have gone instead to the General Fund of the U.S. Treasury. As a third example, for some fiscal years, President Obama proposed a grazing administrative fee for BLM and FS (e.g., of $1.00 per AUM in FY2015 and $2.50 per AUM in FY2017). These administrative fees would have been additional to the annual grazing fee, and the agencies would have used them to offset the cost of administering the livestock grazing programs.

Current Issues

Fee Level

There is ongoing debate about the appropriate grazing fee, with several key areas of contention. First, there are differences over which criteria should prevail in setting fees: fair market value; cost recovery (whereby the monies collected would cover the government's cost of running the program); sustaining ranching, or resource-based rural economies generally; or diversification of local economies. Second, there is disagreement over the validity of fair market value estimates for federal grazing because federal and private lands for leasing are not always directly comparable. Third, whether to have a uniform fee, or varied fees based on biological and economic conditions, is an area of debate. Fourth, there are diverse views on the environmental costs and benefits of grazing on federal lands and on the environmental impact of changes in grazing levels. Fifth, it is uncertain whether fee increases would reduce the number of cattle grazing on sensitive lands, such as riparian areas.25 Sixth, some environmentalists assert that the fee is not the main issue, but that all livestock grazing should be barred to protect federal lands.

As noted, there have been proposals to alter the grazing fee in recent years, but these proposals have not been adopted. For example, the Obama Administration's proposed grazing administration fee of $2.50 per AUM in 2017 would have been in addition to the annual fee of $2.11 per AUM. The monies would have been used for administering grazing to shift a portion of the costs to permit holders. Use of the fees would have been subject to appropriations. BLM estimated that the proposed administrative fee would have generated $16.5 million in FY2017, and FS estimated revenues of $15.0 million in FY2017.26 Livestock organizations, among others, opposed the proposal as an unnecessary and burdensome cost for the livestock industry. The Administration had included similar proposals in earlier budget requests; none of these proposals were enacted.

As another example, in 2005, several groups petitioned BLM and FS to raise the grazing fees, asserting that the fees did not reflect the fair market value of federal forage. When the agencies did not respond to the petition, the groups sued.27 In addition to asserting that BLM and FS unreasonably delayed response to their petition, the petitioners argued that the agencies were required to conduct a study under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) to determine the environmental impacts of the current grazing fee rate. In January 2011, BLM and FS responded to the petition, denying the request for a fee increase, and the lawsuit was settled.28

State and Private Grazing Fees

The BLM and FS grazing fee has generally been lower than fees charged for grazing on other federal lands as well as on state and private lands, as shown in studies over the past 15 years. For instance, a 2005 Government Accountability Office (GAO) study found that other federal agencies29 charged $0.29 to $112.50 per AUM in 2004, when the BLM and FS fee was $1.43 per AUM. While BLM and FS use a formula to set the grazing fee, most agencies charge a fee based on competitive methods or a market price for forage. Some seek to recover the costs of their grazing programs. GAO also reported that in 2004, state fees ranged from $1.35 to $80 per AUM and private fees ranged from $8 to $23 per AUM.30

In 2010, when the BLM and FS fee was $1.35 per AUM, state grazing fees continued to show wide variation. They ranged from $2.28 per AUM for Arizona to $65-$150 per AUM for Texas. Moreover, some states did not base fees on AUMs, but rather had fees that were variable, were set by auction, were based on acreage of grazing, or were tied to the rate for grazing on private lands.31 Further, a 2018 study of state grazing fees in 11 western states continued to show widely differing fees, ranging from $3.50 per AUM for New Mexico to $65-$100 per AUM for Texas. Fees for these states were higher than the 2018 BLM and FS fee ($1.41 per AUM).32

For grazing on private lands in 2017, the average monthly lease rate for lands in 16 western states was $23.40 per head. Fees ranged from $11.50 in Oklahoma to $39.00 in Nebraska.33 For comparison, in 2017, the BLM and FS grazing fee was $1.87 per AUM.

Comparing the BLM and FS grazing fee with state and private fees is complicated due to a number of factors. One factor is the varying purposes for which the fees are charged. Many states and private landowners seek market value for grazing. As noted above, PRIA established the BLM and FS fee in accordance with multiple purposes. They included preventing economic disruption and harm to the western livestock industry as well as being "equitable" and representing the fair market value of grazing. While the base fee originally reflected what was considered to be fair market value, the adjustments included in the formula have not resulted in fees comparable to state and private fees. According to GAO's 2005 study, "it is generally recognized that while the federal government does not receive a market price for its permits and leases, ranchers have paid a market price for their federal permits or leases—by paying (1) grazing fees; (2) nonfee grazing costs, including the costs of operating on federal lands, such as protecting threatened and endangered species (i.e., limiting grazing area or time); and (3) the capitalized permit value."34 Regarding the latter, the capitalized value of grazing permits typically is reflected in higher purchase prices that federal permit holders pay for their ranches.

A second factor is the quality of resources on the lands being grazed and the number and types of services provided by the landowners. For example, in its 2005 study, GAO noted advantages of grazing on private lands over federal lands. They included generally better forage and sources of water; services provided by private landowners, such as watering, fencing, feeding, veterinary care, and maintenance; the ability of lessees to sublease, thus generating revenue; and limited public access. With regard to state lands, the study indicated that states also typically limit public access to their lands, while the quality of forage and the availability of water are more comparable to federal lands.35

A third factor is whether the federal grazing fee alone or other nonfee costs of operating on federal lands are considered in comparing federal and nonfederal costs. Some research suggests that ranchers might spend more to graze on federal lands than private lands when both fee and nonfee costs are considered. Nonfee costs relate to maintenance, herding, moving livestock, and lost animals, among other factors.36

Grazing Without Paying Fees

Unauthorized grazing occurs on BLM and FS lands in a variety of ways, including when cattle graze outside the allowed areas or seasons or in larger numbers than allowed under permit. According to GAO, the frequency and extent of unauthorized grazing is not known, because many cases are handled informally by agency staff. However, during the five-year period spanning 2010 to 2014, BLM and FS documented nearly 1,500 instances of unauthorized grazing, some of which involved the livestock owners having to pay penalties and, less frequently, livestock impoundment.37

In many cases the unauthorized grazing is unintentional, but in other cases livestock owners have intentionally grazed cattle on federal land without getting a permit or paying the required fee. The livestock owners have claimed that they do not need to have permits or pay grazing fees for various reasons, such as that the land is owned by the public; that the land belongs to a tribe under a treaty; or that other rights, such as state water rights, extend to the accompanying forage.

A particularly long-standing controversy involves cattle grazed by Cliven Bundy in Nevada.38 After about two decades of pursuing administrative and judicial resolutions, in April 2014, BLM and the National Park Service began impounding Mr. Bundy's cattle on the grounds that he did not have authority to graze on certain federal lands and had not been paying grazing fees for more than 20 years. BLM estimated at that time that Mr. Bundy owed more than $1 million to the federal government (including grazing fees and trespassing fees) as a result of unauthorized grazing. However, the agencies ceased the impoundment of the cattle due to fears of confrontation between private citizens opposed to the roundup and federal law enforcement officials present during the impoundment. Mr. Bundy had not been paying grazing fees to the federal government primarily on the assertion that the lands do not belong to the United States but rather to the state of Nevada, and that his ancestors used the land before the federal government claimed ownership.39 However, courts determined that the United States owns the lands, enjoined Mr. Bundy from grazing livestock in these areas, and authorized the United States to impound cattle remaining in the trespass areas.40 BLM continues to seek to resolve the issue through the judicial process.

BLM estimated that during the two decades prior to the 2014 intended impoundment of Mr. Bundy's cattle, the agency had impounded cattle about 50 times. The operation to remove Mr. Bundy's cattle from federal lands in Nevada was the biggest removal effort, in terms of the number of cattle and the area involved, according to BLM.41 It was also one of the most controversial, in part because of the number and role of law enforcement officials and the temporary closures of land to conduct the impoundment.42

Voluntary Permit Retirement

There have been efforts to end livestock grazing on certain federal lands through voluntary retirement of permits and leases and subsequent closure of the allotments to grazing. This practice is supported by those who view grazing as damaging to the environment, more costly than beneficial, and difficult to reconcile with other land uses. This practice is opposed by those who support ranching on the affected lands, fear a widespread effort to eliminate ranching as a way of life, or question the legality of the process. In some cases, supporters seek to have ranchers relinquish their permits to the government in exchange for compensation by third parties, particularly environmental groups. The third parties seek to acquire the permits through transfer, and advocate agency amendments to land use plans to permanently devote the grazing lands to other purposes, such as watershed conservation.43

Legislation to authorize an end to grazing in particular areas through voluntary donations of the permits by the permit holders has been introduced in recent Congresses. These measures generally provide for the Secretary of the Interior and/or the Secretary of Agriculture to accept the donation of a permit, terminate the permit, and end grazing on the associated land (or reduce grazing where the donation involves a portion of the authorized grazing). Provisions authorizing such voluntary permit donations in specific areas have sometimes been enacted.44

Other bills have sought to establish pilot programs for livestock operators to voluntarily relinquish permits and leases in particular states. Still other measures have proposed allowing the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of Agriculture to accept a certain number of waived permits, such as a maximum of 100 each year. Under both types of measures, when the Secretaries accept waived permits, they would permanently retire such permits and leases and end grazing on the affected allotments (or reduce grazing where the relinquishment involves a portion of the authorized grazing). Provisions authorizing such pilot programs for particular states or authorizing acceptance of a certain number of waived permits have not been enacted.

In earlier Congresses, legislation was introduced to buy out grazing permittees (or lessees) on federal lands generally or on particular allotments.45 Such legislation provided that permittees who voluntarily relinquished their permits would be compensated at a certain dollar value per AUM, generally significantly higher than the market rate. The allotments would have been permanently closed to grazing. Such legislation, which had been backed by the National Public Lands Grazing Campaign, was advocated to enhance resource protection, resolve conflicts between grazing and other land uses, provide economic options to permittees, and save money. According to proponents, while a buyout program would be costly if all permits were relinquished, it would save more than the cost over time. Opponents of buyout legislation include those who support grazing, others who fear the creation of a compensable property right in grazing permits, some who contend that it would be too costly, or still others who support different types of grazing reform.

Extension of Expiring Permits

The extension, renewal, transfer, and reissuance of grazing permits have been issues for Congress. Both BLM and FS have a backlog of permits needing evaluation for renewal. For instance, BLM's backlog has been increasing for more than a decade, with a backlog of more than 7,000 permit renewals as of September 30, 2017.46 To allow for continuity in grazing operations, Congress had enacted a series of temporary provisions of law allowing the terms and conditions of grazing permits to continue in effect until the agencies complete processing of a renewal. The most recent provision, P.L. 113-291 (Section 3023), made permanent the automatic renewal (until the renewal evaluation process is complete) of grazing permits and leases that expire or are transferred.47

Agency decisions regarding permit issuance are subject to environmental review under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). That environmental review would include the identification of any additional state, tribal, or federal environmental compliance requirements, such as the Endangered Species Act (ESA), that would apply to a permitted grazing operation. P.L. 113-291 provided that the issuance of a grazing permit "may" be categorically excluded from this NEPA requirement under certain conditions.48 Provisions regarding categorical exclusions have been controversial. Supporters assert that they will expedite the renewal process, foster certainty of grazing operations, and reduce agency workload and expenses. Opponents have expressed concern that categorical exclusions could result in insufficient environmental review and public comment to determine range conditions.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

P.L. 95-514, 92 Stat. 1803; 43 U.S.C. §§1901, 1905. Executive Order 12548, 51 Fed. Reg. 5985 (February 19, 1986), at https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/codification/executive-order/12548.html. These authorities govern grazing on the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the Forest Service (FS) lands in 16 contiguous western states, which are the focus of this report. These states are Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. Forest Service grasslands and "nonwestern" states have different fees. In addition, grazing occurs on some other federal lands, not required to be governed by PRIA fees, including certain areas managed by the National Park Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, Department of Defense, and Department of Energy. |

| 2. |

This figure was provided to CRS by BLM on December 10, 2018. It reflects BLM acreage within grazing allotments during FY2017. |

| 3. |

This figure was provided to CRS by BLM on December 10, 2018. It is an estimate of the acreage within BLM allotments for which BLM billed grazing permit and lease holders. |

| 4. |

East is used here to refer to all states except the following 12 states: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming. For more information on federal land ownership by state, see CRS Report R42346, Federal Land Ownership: Overview and Data, by Carol Hardy Vincent, Laura A. Hanson, and Carla N. Argueta. |

| 5. |

These figures were provided to CRS by FS on November 30, 2018. Nearly all of this acreage is in the 16 western states covered by this report. The acreage used for livestock grazing (74 million) reflects FS acreage in active allotments. Additional acres under other ownerships also were in active allotments. Active means that livestock use was permitted during the year. |

| 6. |

BLM uses both permits and leases to authorize grazing. Permits are used for lands within grazing districts (under Section 3 of the Taylor Grazing Act, 43 U.S.C. §315b). Leases are used for lands outside grazing districts (under Section 15 of the Taylor Grazing Act, 43 U.S.C. §315m). |

| 7. |

Statistics in this paragraph were taken from U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI), BLM, Public Land Statistics, 2017, Table 3-8c and Table 3-9c, at https://www.blm.gov/sites/blm.gov/files/PublicLandStatistics2017.pdf. The numbers of operators and animal unit months (AUMs) used are reported as of September 30, 2017, and the number of permits and leases and maximum AUMs are reported as of January 3, 2018. |

| 8. |

Specifically, BLM regulations at 43 C.F.R. §4130.8-1 provide that in general, "[f]or the purposes of calculating the fee, an animal unit month is defined as a month's use and occupancy of range by 1 cow, bull, steer, heifer, horse, burro, mule, 5 sheep, or 5 goats: (1) Over the age of 6 months at the time of entering the public lands or other lands administered by BLM; (2) Weaned regardless of age; or (3) Becoming 12 months of age during the authorized period of use." |

| 9. |

Statistics in this paragraph were provided to CRS by FS on November 30, 2018. |

| 10. |

Specifically, FS regulations at 36 C.F.R. §222.50 provide that "[a] grazing fee shall be charged for each head month of livestock grazing or use. A head month is a month's use and occupancy of range by one animal, except for sheep or goats. A full head month's fee is charged for a month of grazing by adult animals; if the grazing animal is weaned or 6 months of age or older at the time of entering National Forest System lands; or will become 12 months of age during the permitted period of use. For fee purposes 5 sheep or goats, weaned or adult, are equivalent to one cow, bull, steer, heifer, horse, or mule." |

| 11. |

Past estimates of the cost of livestock grazing have varied considerably for a number of reasons, including the following. Some estimates might reflect the entirety of BLM and FS appropriations for rangeland management, whereas others might reflect the subset of these appropriations for administration of livestock grazing. Another variable is whether the estimates reflect any indirect costs to the federal government of livestock grazing, such as programs that might benefit livestock grazing or compensate for impacts of livestock grazing, or indirect costs to ranchers, such as for maintenance of fences and water sources. A 2015 study by the Center for Biological Diversity identifies BLM, FS, and other federal programs that might fund indirect costs of livestock grazing. The study also identifies potential nonfederal costs, such as at the state or local level. The study, entitled Costs and Consequences: The Real Price of Grazing on America's Public Lands," 2015, is available at https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/programs/public_lands/grazing/pdfs/CostsAndConsequences_01-2015.pdf. Another 2015 assessment, by the Public Lands Council, identifies the costs to ranchers of grazing on federal lands in addition to the grazing fee. See Public Lands Council, The Value of Ranching, 2015, at http://publiclandscouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/ValueofRanching_Onesheet-1.pdf. |

| 12. |

The amount used for livestock grazing administration versus other rangeland management activities and the amount of fees collected were provided to CRS by BLM on December 10, 2018. |

| 13. |

The FS appropriation for grazing management was taken from appropriations documents. Other FS appropriations also support livestock grazing but are not separately identifiable. For instance, appropriations for vegetation and watershed management, within the National Forest System account, have been used for range improvements, restoration, and invasive species management. A total of $184.7 million was appropriated for vegetation and watershed management in FY2017, but the portion for activities that benefitted livestock grazing is not identifiable. |

| 14. |

The amount of grazing fees was taken from appropriations documents. |

| 15. |

43 U.S.C. §1905. |

| 16. |

The executive order is available at https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/codification/executive-order/12548.html. |

| 17. |

43 U.S.C. §1751(b)(1). |

| 18. |

This amount is the actual appropriation based on collections. It differs from the amount the agency requested and received in the appropriations law ($2.3 million), which was an estimate. See USDA, FS, FY2019 Budget Justification, p. 110, at https://www.fs.fed.us/sites/default/files/usfs-fy19-budget-justification.pdf. |

| 19. |

43 U.S.C. §1751(b)(1). |

| 20. |

For BLM, see regulations at 43 C.F.R. §4120.3-8. For FS, see regulations at 36 C.F.R. §222.10. |

| 21. |

The allocations described in this paragraph are made regardless of the amount of fees collected by an agency, including whether the total collection is less than the $10.0 million authorized for the range betterment fund (described above). |

| 22. |

More specifically, FS is required to share the annual average of 25% of the revenue generated on NFS land over the previous seven fiscal years with the counties containing those lands. Starting in 2000, however, Congress has at times authorized counties containing national forest system lands to receive revenue-sharing payments through an alternative payment program called Secure Rural Schools (SRS) payments. Payments made through SRS are based not on current revenue but on a formula that accounts for historic revenue. For more information, see CRS Report R41303, Reauthorizing the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act of 2000, by Katie Hoover. Under separate provisions of law (16 U.S.C. §501), 10% of monies received from national forests are to be allocated to the National Forest Roads and Trails Fund. However, these funds sometimes have stayed in the Treasury, as directed by recent annual Interior appropriations laws. |

| 23. |

Taylor Grazing Act of June 28, 1934; ch. 865, 48 Stat. 1269. 43 U.S.C. §§315, 315i. |

| 24. |

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, and U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Grazing Fee Review and Evaluation, A Report from the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of the Interior (Washington, DC: February 1986). |

| 25. |

As described in a BLM glossary, riparian areas are "[l]ands adjacent to creeks, streams, and rivers where vegetation is strongly influenced by the presence of water." See DOI, BLM, Public Land Statistics, 2017, p. 247, at https://www.blm.gov/sites/blm.gov/files/PublicLandStatistics2017.pdf. |

| 26. |

DOI, BLM, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2017, p. II-6 and VII-35 – VII–36, athttps://edit.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/uploads/FY2017_BLM_Budget_Justification.pdf. USDA, FS, FY2017 Budget Justification, pp. 39-40, at https://www.fs.fed.us/sites/default/files/fy-2017-fs-budget-justification.pdf. |

| 27. |

Center for Biological Diversity v. U.S. Department of the Interior, No. 10-CV-952 (D.D.C. Complaint filed June 7, 2010). |

| 28. |

Center for Biological Diversity v. U.S. Department of the Interior, No. 10-CV-952 (D.D.C. Order filed February 23, 2011). |

| 29. |

Other federal agencies covered by the GAO study included the Department of Energy, agencies (in addition to BLM) within the Department of the Interior, and agencies within the Department of Defense. |

| 30. |

GAO, Livestock Grazing: Federal Expenditures and Receipts Vary, Depending on the Agency and the Purpose of the Fee Charged, GAO-05-869 (Washington, DC: September 2005), pp. 37-40, at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-05-869. Hereinafter cited as GAO, Livestock Grazing, 2005. |

| 31. |

These figures and information are derived from an April 2011 study by the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation. The report is at https://web.archive.org/web/20120930233640/http:/dnrc.mt.gov/Trust/AGM/GrazingRateStudy/Documents/GrazingReviewByBioeconomics.pdf. In particular, Table 1 (p. 9) compares fees on state lands in 17 western states. |

| 32. |

Holly Dwyer, WY Office of State Lands & Investments, 2018, State Trust Land Grazing Fees, at https://www.wyoleg.gov/InterimCommittee/2018/05-20180927StateLandsGrazingFees.pdf. |

| 33. |

Statistics on grazing fees on private lands were taken from U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service, Charts and Maps, Grazing Fees: Per Head Fee, 17 States, January 2018, at https://www.nass.usda.gov/Charts_and_Maps/Grazing_Fees/gf_hm.php. Including Texas, which also had a fee of $11.50, the 17-state average fee was $20.60 in 2017. For many years, the National Agricultural Statistics Service has published fees for grazing on private lands. |

| 34. |

GAO, Livestock Grazing, 2005, pp. 49-50, at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-05-869. |

| 35. |

GAO, Livestock Grazing, 2005, p. 49, at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-05-869. |

| 36. |

Neil Rimbey and L. Allen Torrell, Grazing Costs: What's the Current Situation?, University of Idaho, March 22, 2011. |

| 37. |

GAO, Unauthorized Grazing: Actions Needed to Improve Tracking and Deterrence Efforts, GAO-16-559 (Washington, DC: July 2016), pp. 12-13, at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-16-559. |

| 38. |

Except where otherwise noted, information in this paragraph was derived from information provided to CRS by BLM on April 24, 2014, and information formerly on BLM's website (since removed). |

| 39. |

See for example, CBS/AP, CBS News, "Nevada Rancher Cliven Bundy: 'The Citizens of America' Got My Cattle Back," April 13, 2014, at http://www.cbsnews.com/news/nevada-rancher-cliven-bundy-the-citizens-of-america-got-my-cattle-back/. |

| 40. |

For example, court orders were issued on July 9, 2013, and October 9, 2013. |

| 41. |

Telephone communication between BLM and the Congressional Research Service, April 23, 2014. |

| 42. |

Jon Ralston, "Former BLM Director: Bundy is Not a Victim but BLM Mishandled Roundup," Ralston Reports, April 14, 2014, at http://www.ralstonreports.com/blog/former-blm-director-bundy-not-victim-blm-mishandled-roundup. |

| 43. |

The third parties would not pay grazing fees under their permits if they opt not to graze during the amendment process, because fees are paid for actual grazing. |

| 44. |

See, for example, P.L. 114-46, Section 102(e), for certain wilderness areas in Idaho and P.L. 112-74, Section 122, for the California Desert Conservation Area. |

| 45. |

For example, see H.R. 3166 in the 109th Congress. |

| 46. |

DOI, BLM, Budget Justifications and Performance Information, Fiscal Year 2019, p. VI-37, at https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/uploads/fy2019_blm_budget_justification.pdf. The figure in the document shows grazing permits processed by BLM, and permits in an unprocessed status, annually from FY1999-FY2017. |

| 47. |

This provision was enacted as an amendment to portions of the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (specifically 43 U.S.C. 1752) pertaining to livestock grazing on BLM and FS lands in 16 contiguous western states, which is the focus of this report. Annual appropriations laws for Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies have continued to provide automatic extension of grazing permits on other FS lands. |

| 48. |

For information about the various levels of environmental review required under NEPA, see CRS Report RL33152, The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA): Background and Implementation, by Linda Luther. |