Forest Management Provisions Enacted in the 115th Congress

The 115th Congress enacted several provisions affecting management of the National Forest System (NFS), administered by the Forest Service (in the Department of Agriculture), and the lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM, in the Department of the Interior). The provisions were enacted through two laws: the Stephen Sepp Wildfire Suppression Funding and Forest Management Activities Act, enacted as Division O of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141, commonly referred to as the FY2018 omnibus), and the Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-334, Title VIII, commonly referred to as the 2018 farm bill).

Many of the provisions enacted by the 115th Congress affect Forest Service and BLM implementation of two laws: the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and the Healthy Forests Restoration Act (HFRA). These laws, among others, authorize specific forest management activities and establish decisionmaking procedures for those activities. The enacted provisions are summarized and analyzed in the following categories: project planning and implementation, wildland fire management, forest management and restoration programs, and miscellaneous. Ongoing issues for Congress include oversight of (i) the agencies’ implementation of the new laws, and (ii) the extent these provisions achieve their specified purposes, such as improving agency efficiencies, increasing the scale, scope, and implementation of forest restoration projects, and reducing hazardous fuel levels to mitigate against the risk of catastrophic wildfire.

Both the FY2018 omnibus and 2018 farm bill included provisions that affect Forest Service and BLM decisionmaking processes by changing certain aspects of the NEPA process and the interagency consultation requirements established in Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act (ESA). For example, each law specified that certain forest management projects would be considered actions categorically excluded from the requirements of NEPA. Also, both laws expanded various authorities originally authorized in HFRA intended to expedite decisionmaking for specific projects. This included reauthorizing the use of procedures intended to expedite priority projects in designated NFS insect and disease treatment areas and amending the definition of an authorized fuel reduction project to include additional activities.

The FY2018 omnibus and 2018 farm bill also contained provisions that affect federal wildland fire management. The FY2018 omnibus directed the Secretary of Agriculture to adapt the national-scale wildfire hazard potential map for use at the community level to inform risk management decisions. Both laws directed Forest Service and DOI to provide annual reports on a variety of wildfire-related metrics. The FY2018 omnibus also changed how Congress appropriates funding specifically for wildfire suppression purposes. The so-called wildfire funding fix authorized an adjustment to the discretionary spending limits for wildfire suppression operations for each year from FY2020 through FY2027. However, statutory spending limits are set to expire after FY2021, meaning that the adjustment is effectively in place for two years.

Congress has established specific forest restoration programs for Forest Service and BLM, or has authorized forest restoration to be one of many activities or land management objectives for some programs. Forest restoration activities address concerns related to forest health, such as improving forest resistance and resilience to disturbance events (e.g., insect and disease infestation or uncharacteristically catastrophic wildfires). The 115th Congress established two new programs for Forest Service (water source protection and watershed condition framework) and amended three others: the Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program (CFLRP, available only for Forest Service), stewardship contracting authority, and the good neighbor authority. Aspects of several of these programs allow Forest Service and BLM to partner with various stakeholders in different ways to perform specified forest management and restoration activities.

Both the FY2018 omnibus and the 2018 farm bill enacted various other provisions related to land acquisition, exchange and disposal; the issuance of special use authorizations for the use or occupancy of federal lands; the payments, activities, and Resource Advisory Committees authorized by the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act; and forest management on tribal lands.

Forest Management Provisions Enacted in the 115th Congress

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- National Forest System

- Bureau of Land Management Public Lands

- National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)

- Healthy Forests Restoration Act (HFRA)

- HFRA Insect and Disease Designation Areas

- 2014 Farm Bill Insect and Disease NEPA Categorical Exclusion (CE)

- Planning and Project Implementation Requirements

- Statutorily Established NEPA CEs

- Wildfire Resilience CE

- Sage Grouse/Mule Deer CE

- Endangered Species Act Section 7 Consultation Requirements

- Summary of Changes and Discussion

- Wildland Fire Management

- Suppression Spending: Wildfire Funding Fix

- Wildfire Hazard Potential Maps

- Reporting

- Forest Management and Restoration Programs

- Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program (CFLRP)

- Summary of Changes and Discussion

- Good Neighbor Authority

- Summary of Changes and Discussion

- Stewardship Contracting

- Summary of Changes and Discussion

- Watershed Condition Framework

- Summary of Changes and Discussion

- Water Source Protection

- Summary of Changes and Discussion

- Miscellaneous Provisions

- Wilderness Designations

- Land Acquisition, Exchange, and Disposal

- Rights-of-Way (ROW) and Special Use Authorization Provisions

- Forest Service Communication Uses Fee Schedules and Processes

- Electricity Transmission and Distribution ROWs

- Forest Service Utility ROW Pilot Program

- Secure Rural Schools (SRS) Payments and Modifications

- Summary of Changes and Discussion

- Tribal Forestry

- Issues for Congress

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. Comparison of Statutorily Established Categorical Exclusions (CEs) under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)

- Table A-1. Comparison of Forestry Provisions in Prior Law to Changes Enacted in the FY2018 Omnibus (Wildfire Suppression Funding and Forest Management Activities Act)

- Table A-2. Comparison of Forestry Provisions in Prior Law to Changes Enacted in the 2018 Farm Bill

Summary

The 115th Congress enacted several provisions affecting management of the National Forest System (NFS), administered by the Forest Service (in the Department of Agriculture), and the lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM, in the Department of the Interior). The provisions were enacted through two laws: the Stephen Sepp Wildfire Suppression Funding and Forest Management Activities Act, enacted as Division O of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141, commonly referred to as the FY2018 omnibus), and the Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-334, Title VIII, commonly referred to as the 2018 farm bill).

Many of the provisions enacted by the 115th Congress affect Forest Service and BLM implementation of two laws: the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and the Healthy Forests Restoration Act (HFRA). These laws, among others, authorize specific forest management activities and establish decisionmaking procedures for those activities. The enacted provisions are summarized and analyzed in the following categories: project planning and implementation, wildland fire management, forest management and restoration programs, and miscellaneous. Ongoing issues for Congress include oversight of (i) the agencies' implementation of the new laws, and (ii) the extent these provisions achieve their specified purposes, such as improving agency efficiencies, increasing the scale, scope, and implementation of forest restoration projects, and reducing hazardous fuel levels to mitigate against the risk of catastrophic wildfire.

Both the FY2018 omnibus and 2018 farm bill included provisions that affect Forest Service and BLM decisionmaking processes by changing certain aspects of the NEPA process and the interagency consultation requirements established in Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act (ESA). For example, each law specified that certain forest management projects would be considered actions categorically excluded from the requirements of NEPA. Also, both laws expanded various authorities originally authorized in HFRA intended to expedite decisionmaking for specific projects. This included reauthorizing the use of procedures intended to expedite priority projects in designated NFS insect and disease treatment areas and amending the definition of an authorized fuel reduction project to include additional activities.

The FY2018 omnibus and 2018 farm bill also contained provisions that affect federal wildland fire management. The FY2018 omnibus directed the Secretary of Agriculture to adapt the national-scale wildfire hazard potential map for use at the community level to inform risk management decisions. Both laws directed Forest Service and DOI to provide annual reports on a variety of wildfire-related metrics. The FY2018 omnibus also changed how Congress appropriates funding specifically for wildfire suppression purposes. The so-called wildfire funding fix authorized an adjustment to the discretionary spending limits for wildfire suppression operations for each year from FY2020 through FY2027. However, statutory spending limits are set to expire after FY2021, meaning that the adjustment is effectively in place for two years.

Congress has established specific forest restoration programs for Forest Service and BLM, or has authorized forest restoration to be one of many activities or land management objectives for some programs. Forest restoration activities address concerns related to forest health, such as improving forest resistance and resilience to disturbance events (e.g., insect and disease infestation or uncharacteristically catastrophic wildfires). The 115th Congress established two new programs for Forest Service (water source protection and watershed condition framework) and amended three others: the Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program (CFLRP, available only for Forest Service), stewardship contracting authority, and the good neighbor authority. Aspects of several of these programs allow Forest Service and BLM to partner with various stakeholders in different ways to perform specified forest management and restoration activities.

Both the FY2018 omnibus and the 2018 farm bill enacted various other provisions related to land acquisition, exchange and disposal; the issuance of special use authorizations for the use or occupancy of federal lands; the payments, activities, and Resource Advisory Committees authorized by the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act; and forest management on tribal lands.

Introduction1

This report summarizes and analyzes selected forest management provisions enacted in the 115th Congress and compares them with prior law or policy. These provisions were enacted through two legislative vehicles

- The Stephen Sepp Wildfire Suppression Funding and Forest Management Activities Act, enacted as Division O of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141, commonly referred to as the FY2018 omnibus) and signed into law on March 23, 2018.2

- The Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-334, Title VIII), signed into law on December 20, 2018. This law is commonly referred to as the 2018 farm bill.

Both laws included provisions that address forest management through three general perspectives: (1) management of forested federal land, (2) federal programs to support forest management on nonfederal lands, known as forest assistance programs, and (3) programs to promote or conduct forestry research (to benefit both federal and nonfederal forests). This report focuses primarily on the provisions related to management of forested federal land.3 The federal forest management provisions change how the Forest Service (FS, within the Department of Agriculture (USDA)) and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM, within the Department of the Interior (DOI)) manage their lands. FS is responsible for managing the 193 million acres of the National Forest System (NFS), and BLM manages 246 million acres of public lands under its jurisdiction.

This report begins with background information on the NFS and BLM's public lands and an overview of two laws: the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and the Healthy Forests Restoration Act (HFRA).4 These laws, among others, authorize specific forest management activities and establish procedures relevant to the respective agency's decisionmaking processes for those activities. The 115th Congress enacted provisions that affect how FS and BLM implement those activities and procedural requirements.

The report summarizes and analyzes the provisions in the following categories: project planning and implementation, wildland fire management, forest management and restoration programs, and miscellaneous. Within each of those categories, the report broadly discusses relevant issues, summarizes the changes made in the 115th Congress, and discusses potential issues for Congress related to that category. Some provisions or sections are covered in more depth than others, generally reflecting the complexity of the issue, nature of the enacted changes, or level of congressional interest. A separate section at the end of the report discusses overall issues for Congress. The Appendix contains side-by-side tables comparing all of the forest-related provisions in each law to prior law (including provisions related to forestry assistance programs and forestry research).

Background

National Forest System

Approximately 145 million acres of the 193-million-acre NFS consists of forests and woodlands.5 Congress directed that management of the national forests shall be to protect watersheds and forests and provide a "continuous supply of timber for the use and necessities of citizens of the United States" and authorized the sale of "dead, matured, or large growth of trees."6 Congress added recreation, livestock grazing, energy and mineral development, and protection of wildlife and fish habitat as official uses of the national forests, in addition to watershed protection and timber production, in the Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act of 1960 (MUSY).7 Pursuant to MUSY, management of the resources is to be coordinated for multiple use—considering the relative values of the various resources but not necessarily maximizing dollar returns or requiring that any one particular area be managed for all or even most uses—and sustained yield, meaning maintaining a high level of resource outputs in perpetuity without impairing the productivity of the land.

The National Forest Management Act of 1976 (NFMA) requires FS to prepare and update comprehensive land and resource management plans (also referred to as forest plans) for each NFS unit.8 NFMA, as amended, specifies that the plans must be developed and revised with public involvement. Plans, like all discretionary actions taken by the FS, must also comply with any cross-cutting laws that apply broadly to all federal agency actions. This includes compliance with NEPA, as well as Section 7 of Endangered Species Act (ESA), and Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), among others.9 Each forest plan broadly describes a range of desired resource conditions across the specified NFS unit but does not authorize individual projects or specific on-the-ground actions.

Projects are the on-the-ground actions that implement the forest plan prepared for that site. These may include activities such as timber harvests, watershed restoration, trail maintenance, and hazardous fuel reduction, among many others. Projects must be consistent with the resource objectives established in the forest plans. These projects must be planned, evaluated, and implemented using FS procedures intended to ensure compliance with applicable requirements (e.g., NEPA, ESA, NHPA). The timing and scope of review for a given project may vary based on the specific statutory authority underpinning each project's implementation, the types of resources that could be affected at the site, and the level of those potential effects.

Bureau of Land Management Public Lands

BLM manages 246 million acres of public lands, primarily in the western United States. Approximately 38 million acres of those public lands are woodlands and forests.10 The public lands—forested and otherwise—are managed under the principles of multiple use and sustained yield, as directed by the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA).11 These principles are similar to those that govern the NFS. The 2.6 million acres of Oregon and California Railroad (O&C) Lands and Coos Bay Wagon Road (CBWR) Lands in western Oregon, however, are forested lands managed under a statutory direction for permanent forest production under the principle of sustained yield and with the purposes of providing timber, protecting watersheds, providing recreational opportunities, and contributing to the economic stability of the local communities.12 Similar to the requirements applicable to FS decisionmaking, FLPMA directs BLM to prepare and maintain comprehensive resource management plans and to revise them as necessary.13 Any proposed on-the-ground activities or projects must be consistent with those plans and must be planned, evaluated, and implemented using BLM's procedures for ensuring compliance with the laws that apply broadly to any federal agency action (e.g., NEPA, ESA, NHPA).

National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)14

Broadly, NEPA requires federal agencies to identify the environmental impacts of a proposed action before making a final decision about that action.15 How a federal agency demonstrates compliance with NEPA depends on the level of the proposal's impacts.16 A proposed action that would significantly affect the "quality of the human environment" requires the preparation of an environmental impact statement (EIS) leading to a Record of Decision.17 If the impacts are uncertain, an agency may prepare an environmental assessment (EA) to determine whether an EIS is necessary, or whether a finding of no significant impact (FONSI) may be issued through a Decision Notice. For actions that require an EA or EIS, an agency generally must evaluate the impacts of the proposed action and reasonable alternatives to it, including the alternative of taking no action (i.e., a no-action alternative). The analysis included in the EIS or EA/FONSI is used to inform the agency's decisionmaking process regarding the proposal.

Under NEPA implementing regulations, categorical exclusions (CEs) refer broadly to categories of actions that do not individually or cumulatively have a significant effect on the environment and hence are excluded from the requirement to prepare an EIS or an EA.18 FS and BLM have identified CEs based on each agency's past experience with similar actions. Some CEs have been explicitly established in statute by Congress, as discussed in the "Statutorily Established NEPA CEs" section of this report. Individual agencies also may determine whether or what additional documentation may be required for a CE. In its list of CEs, FS distinguishes between actions that generally do not require any further documentation and those that generally require the preparation of a decision memorandum as part of an administrative record supporting the decision to approve the proposal as a CE.19

In their agency-specific procedures implementing NEPA, each federal agency has identified and listed actions it is authorized to approve that normally require an EIS, or an EA resulting in a FONSI, or that can be approved using a CE.20 FS and BLM regulations also provide for and identify the resource conditions in which a normally excluded action may have the potential for a significant environmental effect and warrant further analysis in an EA or EIS.21 The presence of these resource conditions is termed extraordinary circumstances. For example, FS has identified the presence of flood plains, municipal watersheds, endangered species or their habitat, wilderness areas, inventoried roadless areas, and archaeological sites, among others, as potential extraordinary circumstances that may preclude the use of a CE for an otherwise eligible project.22

As commonly implemented, the process of identifying potential environmental impacts pursuant to NEPA serves as a framework to identify any other environmental requirements that may apply to that project as a result of those impacts. In this way, an agency's procedures to implement NEPA may serve as an umbrella compliance process. For example, within the framework of determining the resources affected and level of effects of a given proposal, the agency's NEPA process would identify project impacts that may trigger additional environmental review and consultation requirements under ESA and NHPA, among other laws. If compliance with NEPA was waived for a given category of action, the requirements triggered by impacts to those resources under other federal laws would still apply.

Healthy Forests Restoration Act (HFRA)

HFRA, among other purposes, was intended to expedite the planning and review process for hazardous fuel reduction and forest restoration projects on NFS and BLM lands.23 Hazardous fuel reduction projects are intended to reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfire by removing or modifying the availability of biomass (e.g., trees, shrubs, grasses, needles, leaves, and twigs) that fuel a wildland fire through a variety of methods and measures.

HFRA defined specific hazardous fuel reduction projects and authorized an expedited planning and review process for those projects. The authorization is available to be used for projects covering up to a cumulative total of 20 million acres of federal land. HFRA defined several other relevant terms, some of which are summarized below24

- At-Risk Community: an area that is comprised of an interface community as defined in the notice published in 66 Federal Register 753, or a group of homes and other structures with basic infrastructure and services within or adjacent to federal land, and an area in which conditions are conducive to a large-scale wildland fire disturbance event and for which a significant threat to human life or property exists as a result of significant wildland fire disturbance event.25

- Authorized Hazardous Fuels Reduction Projects (HFRA Projects): methods and measures for reducing hazardous fuels including prescribed fire, wildland fire use, and various mechanical methods (e.g., pruning or thinning, which is the removal of small-diameter trees to produce commercial and pre-commercial products).26

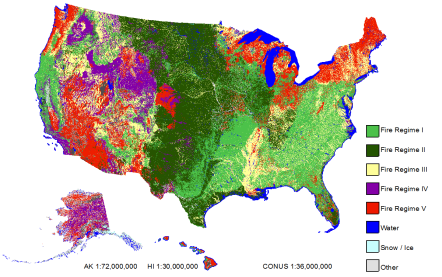

- Fire Regimes and Condition Classes: terms used to describe the relative change between the historical frequency and intensity of fire patterns across a vegetated landscape to the current fire patterns. These terms are used to prioritize and assess hazardous fuel reduction projects. For a complete definition, see the shaded text box and Figure 1.

- Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI): an area within or adjacent to an at-risk community with a community wildfire protection plan (CWPP), or an area within a specified distance to an at-risk community without a CWPP and with specified characteristics (e.g., steep slopes).27

HFRA projects may be conducted in the WUI; on specified areas within a municipal watershed and with moderate or significant departure from the historical fire regimes (see shaded text box); on wind-, ice-, insect-, or disease-damaged land, or land at risk of insect or disease damage; or on lands with threatened and endangered species habitat threatened by wildfire.28 HFRA explicitly excluded projects that would occur on designated wilderness areas, wilderness study areas, or areas that otherwise prohibit vegetation removal by an act of Congress or presidential proclamation.29 Also, HFRA projects must be consistent with the land and resource management plan in place for the area. Certain covered projects—basically, any HFRA project except those in response to or anticipation of wind, ice, insect, or disease damage—must focus on thinning, prescribed fire, or removing small-diameter trees to modify fire behavior, while maximizing large or old-growth tree retention (if retention promotes fire resiliency).30

|

Fire Regime Condition Class Fire regime condition class is a classification that describes the relative change between the historical (prior to modern human intervention) frequency and intensity of fire patterns across a vegetated landscape and the current fire patterns. More specifically, the term fire regime describes fire's relative frequency and severity in an ecosystem, and condition class describes the degree of departure from reference historical conditions. Fires in landscapes classified into Fire Regime 1 occur every 0-35 years, and the fires are of low to mixed severity. Fire Regime II also has a frequency of 0-35 years, but the fires are severe, resulting in stand replacement of over 75% of the dominant overstory vegetation. Fire Regime III has a frequency of fire that ranges from 35-200 years, and the fires are of low to mixed severity. Fire Regime IV also has a frequency ranging from 35-200 years, but the fires are severe. Fire Regime V has a frequency of more than 200 years and includes fires of any severity. With respect to departure from reference historical conditions, Condition Class 1 represents no or minimal departure; Condition Class 2 represents a moderate departure and declining ecological integrity; Condition Class 3 describes a high departure and poor ecological integrity. For more information, see S. Barrett et al., Interagency Fire Regime Condition Class (FRCC) Guidebook Version 3.0, 2010, http://www.frames.gov/. The Healthy Forest Restoration Act (HFRA) authorizes certain activities in areas classified as Condition Class 2 or 3 in Fire Regimes I, II, and III. HFRA's definition of these terms (see 16 U.S.C. §6511) is largely consistent with the above descriptions, except that HFRA defines Fire Regime III as mixed severity fires with a return frequency of 35-100 years; instead of 35-200 years. At the time of enactment, the return frequency for Fire Regime III was defined as 35-100+ years, and the classification scale has been refined as data availability, data reliability, and modeling capacity have improved. |

|

|

Source: Forest Service and DOI Landscape Fire and Resource Management Planning Tools (LANDFIRE) program, Fire Regime Group dataset, available from https://www.landfire.gov/frg.php. Notes: The term "Other" includes landscapes with indeterminate fire regime characteristics, or classified as barren or sparsely vegetated. |

HFRA also directed FS to establish a pre-decisional administrative review process—referred to as an objection process—for proposed HFRA projects.31 The review is called pre-decisional because HFRA explicitly requires objections to be filed within 30 days of the agency's publication of the draft decision documents associated with the proposed project (e.g., a draft Decision Notice and final EA, or draft Record of Decision and final EIS). Objections are limited to parties that submitted specific comments during the comment periods and may only be on issues raised within those comments. If no comments were received on a project, no objections will be accepted.32 HFRA also set forth requirements for judicial review. If the objector is still not satisfied with the agency's decision after the administrative review (i.e., objections) process has been exhausted, the next step is judicial review in federal court. However, only issues that were raised during the public comment period and the pre-decisional administrative review process may be considered during judicial proceedings, unless significant new issues arise after the conclusion of the administration review.33

Congress later directed FS to replace the post-decisional administrative appeals process used for non-HFRA projects with the pre-decisional objection process used by HFRA projects.34 As a result, all FS projects fall under the same pre-decisional objection process, although there are some differences between HFRA and non-HFRA projects. For example, the Chief of the Forest Service may declare a non-HFRA project an emergency situation and proceed directly to implementation after the publication of the decision document.

HFRA Insect and Disease Designation Areas

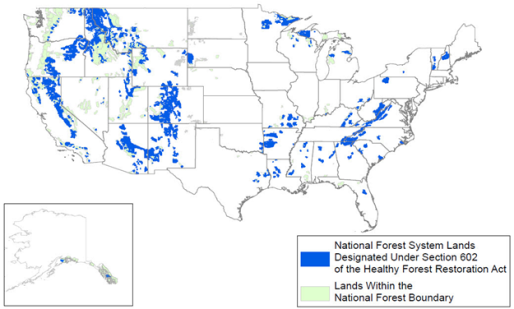

The Agricultural Act of 2014 (the 2014 farm bill) added a new Section 602 to HFRA and authorized the establishment of landscape-scale insect and disease treatment areas within the NFS, by state, as requested by the state governor and then designated by the Chief of the Forest Service.35 To be eligible for this insect and disease treatment area designation, the NFS area must be experiencing declining forest health based on annual forest health surveys, at risk of experiencing substantial tree mortality over the next 15 years, or in an area in which hazard trees pose an imminent risk to public safety. In total, FS has designated approximately 74.5 million acres nationwide (see Figure 2).36 (Hereinafter this report refers to these designated areas as I&D areas.)

|

Figure 2. Map of NFS HFRA Designated Insect and Disease Treatment Areas |

|

|

Source: Forest Service Geospatial Technology and Applications Center (2/21/2018), available at https://www.fs.fed.us/farmbill/documents/additional/NFS_Designations_HFRA_Map_20180201.pdf. Notes: Hawaii (not shown) has no such lands. Data displayed are for informational purposes only and depict designations made under section 602 of HFRA. |

The act specified that FS may prioritize projects that reduce the risk or extent of, or increase the resilience to, insect or disease infestations within the I&D areas. The act further specified that such projects initiated prior to the end of FY2018 are to be considered hazardous fuel reduction projects pursuant to HFRA.37 Thus, these projects also are subject to HFRA's pre-decisional objections process; must be developed through a collaborative process with state, local, and tribal government collaboration and participation of interested persons; consider the best available science; and maximize the retention of old-growth and large trees, as appropriate for the forest type and to the extent it would promote insect and disease resiliency. Also pursuant to HFRA, projects planned within the WUI require the analysis of the proposed action and one action alternative during the preparation of an EA or EIS. If the proposed action is within 1.5 miles to an at-risk community, then only analysis of the proposed action is required (i.e., the no-action alternative does not need to be analyzed). For projects outside of the WUI, the no-action alternative must also be considered.

In sum, Congress authorized FS to identify eligible NFS areas for designation as I&D areas, prioritize projects in those designated areas, and plan and implement those projects through a potentially expedited process. In some states, all eligible lands were designated. In those states, the expedited project planning procedures are thus broadly available, but any prioritization benefit is effectively nullified.

As of March, 2019, FS reports 206 projects across 59 national forests and 18 states have been proposed under these authorities.38 Of those, FS evaluated or is evaluating 20 using the EA analysis procedures and three using an EIS. The remaining 183 projects are being processed or were processed using a CE, described below.

2014 Farm Bill Insect and Disease NEPA Categorical Exclusion (CE)

The 2014 farm bill also added a new Section 603 to HFRA, which specified in statute that certain projects intended to reduce the risk or extent of insect or disease infestations within I&D areas would be considered actions categorically excluded from the requirements of NEPA (commonly referred to as the Farm Bill CE).39 (The 2018 farm bill added hazardous fuels projects as a priority project category eligible to be implemented through the CE, discussed in the "Planning and Project Implementation Requirements" section). The law specified that these projects are exempt from the pre-decisional administrative review objections process.40

To be eligible for the 2014 Farm Bill CE, projects must either

- 1. comply with the eligibility requirements of the Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program (CFLRP),41 or

- 2. consider the best available science; maximize the retention of old-growth and large trees, as appropriate for the forest type and to the extent that it would promote insect and disease resiliency; and be developed through a collaborative process that is transparent and nonexclusive, or which meets specified requirements.42

Projects may not establish any new permanent roads, and any temporary roads must be decommissioned within three years of the project's completion. However, maintenance and repairs of existing roads may be performed as needed to implement the project. Projects cannot exceed 3,000 acres. The projects must be located within designated I&D areas. In addition, projects may be located within the WUI, or outside of the WUI but in areas classified as Condition Classes 2 or 3 in Fire Regime Group I, II, or III, as defined by HFRA.43 FS policy is to document its decision on a proposal using the Farm Bill CE through a decision memorandum, after determining whether resource conditions at the site result in any extraordinary circumstances subject to further review and consultation.44

Planning and Project Implementation Requirements

The FY2018 omnibus and the 2018 farm bill both changed certain FS and BLM planning and project implementation requirements. For example, both laws expanded various HFRA authorities

- The FY2018 omnibus (§203) amended HFRA to expand the definition of an authorized fuel reduction project to include the installation of fuel breaks (e.g., measures that change fuel characteristics in an attempt to modify the potential behavior of future wildfires) and fire breaks (e.g., natural or constructed barriers to stop, or establish an area to work to stop, the spread of a wildfire). Thus, projects to build fuel or fire breaks may be planned and implemented using the procedures authorized under HFRA, such as requiring analysis of a specific number of alternatives depending on the proposed action's location.

- The 2018 farm bill reauthorized (through FY2023) the use of the procedures intended to expedite priority projects in I&D areas. It also added projects to reduce hazardous fuels as a priority project category (§8407(b)). This means that hazardous fuels reduction projects may be planned and implemented using the Farm Bill CE, if those actions are located within I&D areas and meet the other eligibility requirements.

In addition, both the FY2018 omnibus and the 2018 farm bill each established a new statutory NEPA CE. The 2018 farm bill also included provisions affecting the interagency consultation requirements under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).45 These changes are each discussed in the following sections.

Statutorily Established NEPA CEs

Both laws established new statutory CEs intended to expedite the planning and implementation of specific projects. The FY2018 omnibus established a CE for wildfire resilience projects, which is effectively available only for FS. The 2018 farm bill established a CE for projects related to greater sage grouse or mule deer habitat, which is available to both FS and BLM. The provisions of each CE share some similarities with the Farm Bill CE (see Table 1 for a side-by-side comparison of the three CEs).

It is difficult to assess the potential impact of these new CEs, either on the pace of project planning and implementation or on various forest management goals. Both of the statutory CEs—as well as the 2014 Farm Bill CE—allow FS (and BLM, as applicable) to plan for larger projects (up to 3,000 to 4,500 acres) through a CE. Some say larger project sizes—with or without a CE—will allow FS to achieve landscape-level goals more efficiently.46 Some also contend that using a CE for the environmental review will allow FS to proceed from project planning to project implementation at a faster pace, improving agency efficiency. For example, a 2014 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report found that FS took an average of 177 days to complete CEs, compared with 565 days to complete EAs, in FY2012.47 That same GAO report found that from FY2008 to FY2012, FS used CEs less frequently and the process took longer to complete compared with other agencies. However, the analysis period occurred before Congress authorized the Farm Bill CE, and it is possible that FS trends have since changed. In contrast, others are concerned that conducting landscape-scale projects without more detailed environmental reviews and documentation, or implementing projects of additional types and larger areas through CEs, may lead to undesirable resource effects.48

Wildfire Resilience CE

Section 202 of the FY2018 omnibus added a new Section 605 to HFRA and established a Wildfire Resilience CE for specified hazardous fuel reduction projects.49 The Wildfire Resilience CE is similar to the Farm Bill CE. Projects must be located within designated I&D areas on NFS lands. FS policy is to document the decision to use the Farm Bill CE through a decision memo, after determining if there are any extraordinary circumstances present that could have a significant environmental effect, as specified in the statute and consistent with FS regulations.50

Eligible projects must either

- 1. comply with the CFLRP eligibility requirements,51 or

- 2. maximize the retention of old-growth and large trees to the extent that the trees promote resiliency; consider best available science; and be developed through a collaborative process that is transparent and nonexclusive, or which meets specified requirements.52

Projects may not establish any new permanent roads, and temporary roads must be decommissioned within three years of project completion. However, maintenance and repairs of existing roads may be performed as needed to implement the project. Projects cannot exceed 3,000 acres. In addition to being located within I&D areas, the law specifies that projects located within the WUI are prioritized, but projects may be located outside the WUI if they are located in areas classified as Condition Class 2 or 3 in Fire Regime groups I, II, or III that contain very high wildfire hazard potential. The law further requires the Secretary to submit an annual report on the use of the CEs authorized under this section to specified congressional committees and GAO. FS reports that seven projects were proposed using the authority in FY2018.53

Many of the same location and purpose requirements for projects planned under the 2014 Farm Bill CE are required for projects that could be planned and implemented under the Wildfire Resilience CE (see Table 1). For example, both CEs require projects to be located within designated I&D areas. Both CEs also require projects located outside of the WUI to be in the same specified fire regime condition classes, but the Wildfire Resilience CE also specifies that those projects should be located in areas that also contain very high wildfire hazard potential. In addition, the Wildfire Resilience CE specifies that projects located within the WUI should be prioritized; the Farm Bill CE does not include that prioritization. The Wildfire Resilience CE is available only for specified hazardous fuels reduction projects, while the Farm Bill CE is also available for projects to address insect and disease infestation. In the Wildfire Resilience CE, Congress explicitly directed FS to apply its procedures for evaluating if the resource conditions identified as extraordinary circumstances are present on the project site, and if the presence of those extraordinary circumstances may thus preclude the use of the CE and require further analysis of potential impacts through an EA or EIS. Although similar legislative language was not included, FS must still also assess if there are extraordinary circumstances present that may preclude the use of the Farm Bill CE (and all other CEs).

Sage Grouse/Mule Deer CE

Section 8611 of the 2018 farm bill directs the Secretary of Agriculture, for NFS lands, and the Secretary of the Interior, for BLM lands, to establish a CE for specified projects to protect, restore, or improve greater sage-grouse and/or mule-deer habitat within one year of enactment. It also specifies requirements for applying the CE.54 Projects must protect, restore, or improve habitat in a sagebrush steppe ecosystem for either species, or concurrently for both species if the project is located in both mule deer and sage-grouse habitat.55 Projects must be consistent with the existing resource management plan and for projects on BLM lands, comply with DOI Secretarial Order 3336.56 The law also described the specific activities that may be part of a project, such as removal of juniper trees, cheat grass, and other nonnative or invasive vegetation; targeted use of livestock grazing to manage vegetation; and targeted herbicide use, subject to applicable legal requirements. Projects may not occur in designated wilderness areas, wilderness study areas, inventoried roadless areas, or any area where the removal of vegetation is restricted or prohibited. Projects may not include any new permanent roads, but may repair existing permanent roads. Temporary roads shall be decommissioned within three years of project completion, or when no longer needed. Projects may not be larger than 4,500 acres. On NFS lands, projects may occur only within designated I&D areas. The law directs each agency to apply its respective extraordinary circumstances procedures in determining whether to use the CE. In addition, the law directs the agencies to consider the relative efficacy of landscape-scale habitat projects, the likelihood of continued population declines in the absence of landscape-scale vegetation management, and the need for habitat restoration. The agencies must also develop a 20-year monitoring plan prior to using the CE.

This CE has some basic similarities to the other two CEs—such as requirements for projects to be developed through a collaborative process—but the project purposes and requirements differ significantly (see Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of Statutorily Established Categorical Exclusions (CEs) under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)

|

Farm Bill CE 2014 Farm Bill, (P.L. 113-79 §8204) |

Wildfire Resilience CE FY2018 omnibus (P.L. 115-141 §202) |

Sage Grouse/Mule Deer CE 2018 Farm Bill (P.L. 115-334 §8611) |

|

|

Available to |

Forest Service (FS) |

FS |

FS & Bureau of Land Management (BLM) |

|

Eligible lands |

National Forest System (NFS) designated insect and disease treatment areas (I&D areas) |

NFS I&D areas |

NFS I&D areas BLM lands |

|

Other Geographic Requirements |

I&D areas, and:

|

I&D areas, and:

|

Within range of sage grouse or mule deer. If located within range of both, activity must protect, restore, or improve habitat for both species. |

|

Prohibited Areas |

Wilderness, congressionally designated wilderness study areas (WSAs), any lands where removal of vegetation is prohibited through law or presidential proclamation, or area in which the activities would not be consisted with forest plan |

Same as Farm Bill CE |

Same as Farm Bill CE, except: All WSAs (including those designated administratively), inventoried roadless areas on NFS lands, and any activity for the construction of a permanent road or trail |

|

Project Purpose as described in the authorizing legislation |

Projects designed to reduce the risk or extent of, or increase the resilience to, insect and disease infestation; or to reduce hazardous fuels.b |

Hazardous fuels reduction project. |

Protects, restores, or improves sage grouse or mule deer habitat as described in: USGS Circular 1416c or Mule Deer Working Group of the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies.d |

|

Project Requirements |

Must implement a forest restoration treatment that either: |

Same as Farm Bill CE. |

Same as Farm Bill CE, and:

|

|

Other Requirements |

Consistent with forest plan |

Consistent with forest plan Extraordinary circumstances shall apply |

Same as Wildfire Resilience CE, and: Meets standards specified in DOI Secretarial Order 3336 (1/15/15).g Specific activities authorized (Sec. (a)(1)(B). For example, targeted herbicide use in accordance with law, procedures, and plans; targeted livestock grazing; temporary removal of wild horse & burros; modification or adjustment of grazing permit to achieve resource management objectives, among others Consider relative efficacy of landscape scale habitat projects; likelihood of continued population declines in the absence of landscape-scale vegetation management; and the need for post-disturbance habitat restoration treatments Develop long-term monitoring plan of at least 20 years Specifies any vegetative material requiring disposal may be used for fuel wood, other products, or piled/burned |

|

Maximum Acreage |

3,000 acres |

3,000 acres |

4,500 acres |

|

Roads |

No new permanent roads May perform maintenance on existing roads Temporary roads must be decommissioned within three years of project completion |

Same as Farm Bill CE |

Defines temporary road and specifies activities related to maintenance, repair, rehabilitation, or reconstruction of temporary or permanent roads are covered activities. Specifies temporary roads may only be used for two years and shall be decommissioned within three years of project completion or when no longer needed, and shall include reestablishing native vegetative cover within 10 years |

Source: CRS, compiled from legislative text and Forest Service Handbook FSH 1909.15 NEPA Handbook, Chapter 30 - Categorical Exclusion from Documentation, September 24, 2018, https://www.fs.fed.us/im/directives/fsh/1909.15/wo_1909.15_30_Categorical%20Exclusion%20from%20Documentation.doc.

Notes: The Farm Bill CE was established by the 2014 farm bill (P.L. 113-79 §8204); the Wildfire Resilience CE was established by the FY2018 omnibus (P.L. 115-141 §202); and the Sage Grouse/Mule Deer CE was established by the 2018 farm bill (P.L. 115-334 §8611).

a. For more information on Fire Regime Condition Classes, see the "Healthy Forests Restoration Act (HFRA)" section.

b. The 2018 farm bill (§8407(b)) added hazardous fuels reduction projects as an eligible project purpose.

c. USGS = U.S. Geological Survey. USGS Circular 1416 available from https://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/1416/cir1416.pdf.

d. https://www.wafwa.org/committees___groups/mule_deer_working_group/publications/.

e. CFLRP = Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program. The eligibility requirements for CFLRP proposals are specified in 16 U.S.C. §7303(b). This includes requiring the proposal to have been developed through a collaborative process. It also includes a range of requirements that may not be applicable for the insect and disease treatment projects, such as identifying a work plan of projects for a 10-year period and covering a project area of at least 50,000 acres, among others.

f. RAC = Resource Advisory Committees. The RAC requirements are specified in 16 U.S.C. §§7125(c)-7125(f).

g. Department of the Interior, Secretarial Order 3336, Rangeland Fire Prevention, Management and Restoration, January 5, 2015, among other items, established a Rangeland Fire Task Force to study and present a final report on policies for preventing and suppressing rangeland fire and restoring sagebrush landscapes. See DOI, An Integrated Rangeland Fire Management Strategy, May 2015, https://www.forestsandrangelands.gov/documents/rangeland/IntegratedRangelandFireManagementStrategy_FinalReportMay2015.pdf.

Endangered Species Act Section 7 Consultation Requirements57

The Endangered Species Act (ESA) has a stated purpose of conserving species identified as endangered or threatened with extinction and conserving ecosystems on which these species depend. It is administered primarily by the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS, in DOI) for terrestrial and freshwater species, but also by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS, in the Department of Commerce) for certain marine species.58 Under the ESA, individual species of plants and animals (both vertebrate and invertebrate) can be listed as either endangered or threatened according to assessments of the risk of their extinction.59 Once a species is listed, a set of prohibitions applies to the species.60 The ESA provides federal agencies with an opportunity to gain an exemption from the prohibitions under certain circumstances.61

Federal agencies must ensure that their actions—or the actions of nonfederal parties granted a federal approval, permit, or funding—are "not likely to jeopardize the continued existence" of any endangered or threatened species, or adversely modify their critical habitat.62 The federal agencies must consult with either FWS or NMFS if such an action might adversely affect a listed species as determined by the Secretary of the Interior or the Secretary of Commerce. This is referred to as a Section 7 consultation. Where a federal action is dictated by statute, a Section 7 consultation is not required, as it applies to only discretionary actions.

If the appropriate Secretary finds that an action would neither jeopardize a species nor adversely modify the critical habitat of that species, the Secretary issues a biological opinion (BiOp) to that effect. The BiOp specifies the terms and conditions under which the federal action may proceed to avoid jeopardy or adverse modification of critical habitat. Alternatively, if the proposed action is judged to jeopardize listed species or adversely modify critical habitat, the Secretary must suggest any reasonable and prudent alternatives that would avoid harm to the species. The great majority of consultations result in "no jeopardy" opinions, and nearly all of the rest find that the project has reasonable and prudent alternatives, which will permit it to go forward.63

Summary of Changes and Discussion

The FY2018 omnibus enacted changes to how the Section 7 consultation requirements interact with the development of land and resources management plans for the NFS and for the O&C and CBWR lands managed by the BLM in Oregon (§§208, 209). The law specifies that the listing of a species as threatened or endangered or the designation of critical habitat pursuant to the ESA does not require the Secretary of Agriculture (for NFS lands) or the Secretary of the Interior (for the O&C and CBWR lands) to engage in Section 7 consultation to update or revise a forest plan, unless the plan is older than 15 years and 5 years has passed since either the date of enactment or the listing of the species, whichever is later. The law further specifies, however, that this does not affect the requirements for Section 7 consultation for projects implementing forest plans or for plan updates or amendments.

The changes in the FY2018 omnibus are controversial, because some argue that they set a new precedent for implementing ESA.64 According to some, the provisions were needed to override a decision by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals that required FS to conduct re-consultation on its land management plans after critical habitat was designated for the Canada lynx.65 Those in favor of the enacted changes contend that not requiring Section 7 consultations for existing land management plans due to a species listing or designation of critical habitat will provide more flexibility in implementing plans, allow for consistency in keeping the plans in place, and enable plan and project implementation to proceed with fewer delays.66 The exceptions in the law would allow for changes in plans after a certain time, thereby reflecting changes to listed species and their critical habitat.

Those opposed to these provisions contend that not allowing for consultation or re-consultation to take place due to changes in listing species and critical habitat could negatively affect species if plans prescribe harmful activities and are allowed to be kept in place.67 In addition, some contend that the time lag before consultation is required could be long enough to harm species and negatively affect their habitat. Proponents of the change, however, note that projects under a plan are still required to undergo consultation, thereby making the consultation of the plan redundant. However, critics of the provision contend that plans address projects and activities at a higher level and could influence the cumulative effect of all projects and activities under the plan.68

|

Section 7 Interagency Working Group The 2018 farm bill also addressed the interaction between forestry issues and consultation under ESA. Under §10115 of the law, the Administrator of the EPA is to establish an interagency working group to create and implement a strategy for improving the Section 7 consultation process for evaluating the effects of pesticides on listed species and their habitat. The scope of the working group is to analyze law; recommend methods for scoping and identifying the effects of pesticides on species; review practices for consultation; and develop scientific and policy approaches to increase the accuracy and timeliness of consultation. This effort is to be directed at improving Section 7 consultations and Section 10 consultations (i.e., consultation with the private sector). The working group is to report its findings to Congress. Several stakeholders assert that this process should improve the ESA pesticide evaluation process and provide Congress with oversight over the improvements (See for example, Jake Li, Environmental Policy Innovation Center, "Farm Bill Will Improve how Endangered Species Act Evaluates Pesticides," press release, December 15, 2018, http://policyinnovation.org/farm-bill-will-improve-how-endangered-species-act-evaluates-pesticides/). Some others might contend that changes to streamline consultation might lower the level of scientific analysis needed to determine the effects of pesticides on listed species. |

Wildland Fire Management

The federal government's wildland fire management responsibilities—fulfilled primarily by FS and DOI—include fuel reduction, preparedness, prevention, detection, response, suppression, and recovery activities. The FY2018 omnibus and 2018 farm bill contained provisions that changed how Congress appropriates funding specifically for wildfire suppression purposes, added specific requirements for wildfire risk mapping (part of preparedness), and added specific reporting requirements. This section provides some background information on wildland fire appropriations and then discusses those changes in more detail. The laws also changed aspects of FS and DOI's hazardous fuel reduction programs. This included reauthorizing the use of procedures intended to expedite the priority projects in NFS areas designated as I&D areas and expanding the definition of an authorized fuel reduction project, as discussed previously in the "Planning and Project Implementation Requirements" section.

Congress provides discretionary appropriations for wildland fire management to both FS and DOI through the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies appropriations bill.69 Funding for DOI is provided to the department, which then allocates the funding to the Office of Wildland Fire and four agencies—BLM, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the National Park Service, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.70 Within FS's and DOI's respective Wildland Fire Management (WFM) account, funding is provided to the Suppression Operations program to fund the control of wildfires that originate on federal land.71 This includes firefighter salaries, equipment, aviation asset operations, and incident support functions in direct support of wildfire response, plus personnel and resources for post-wildfire response programs. If their suppression funding is exhausted during a fiscal year, FS and DOI are authorized to transfer funds from their other accounts to pay for suppression activities; this is often referred to as fire borrowing.72

Overall appropriations to FS and DOI for wildland fire management have increased considerably since the 1990s. A significant portion of that increase is related to rising suppression costs, even during years of relatively mild wildfire activity, although the costs vary annually and are difficult to predict. FS and DOI frequently have required more suppression funds than have been appropriated to them. This discrepancy often leads to fire borrowing, prompting concerns that increasing suppression spending may be detrimental to other agency programs. In response, Congress has typically enacted supplemental appropriations to repay the transferred funds and/or to replenish the agency's wildfire accounts. Wildfire spending—like all discretionary spending—is currently subject to procedural and budgetary controls. In the past, Congress has sometimes—but not always—effectively waived some of these controls for certain wildfire spending. This situation prompted the 115th Congress to explore providing wildfire spending outside of those constraints, as discussed below.

Suppression Spending: Wildfire Funding Fix

In the FY2018 omnibus, the 115th Congress established a new mechanism for suppression funding, commonly referred to as the wildfire funding fix (§102(a)). Pursuant to the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA), discretionary spending currently is subject to statutory limits for each of the fiscal years between FY2012 and FY2021.73 Enacted discretionary spending may not exceed these limits. If spending that exceeds a limit is enacted, the limit is to be enforced through sequestration, which involves the automatic cancellation of budget authority largely through across-the-board reductions of nonexempt programs and activities. Certain spending is effectively exempt from the discretionary spending limits pursuant to Section 251(b) of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act (BBEDCA), because those limits are "adjusted" upward each year to accommodate that spending. Spending for specified emergency requirements and disaster-relief purposes falls into this category.74 Section 102(a)(3) of the FY2018 omnibus amended BBEDCA to add a new adjustment to the nondefense discretionary spending limit for wildfire suppression operations. This new adjustment starts in FY2020 and continues for each year thereafter through FY2027.75 For the purposes of the adjustment, wildfire suppression operations includes spending for the purposes of

- the emergency and unpredictable aspects of wildland firefighting, including support, response, and emergency stabilization activities;

- other emergency management activities; and

- funds necessary to repay any transfers needed for these costs.

The new adjustment would apply to appropriations provided above an amount equal to the 10-year average spending level for wildfire suppression operations as calculated for FY2015 ("FY2015 baseline"). That is, an amount equal to the FY2015 baseline would be subject to the statutory discretionary limits, and then any additional funding appropriated would be considered outside the limits and would be the amount of the adjustment. The amount of the adjustment is capped each fiscal year, starting at $2.25 billion in FY2020 and increasing by $0.1 billion ($100 million) to $2.95 billion in FY2027.76

Whatever amount, if any, Congress elects to appropriate for wildfire suppression over the FY2015 baseline ($1.39 billion combined)77 effectively would not be subject to the discretionary spending limits established in the BCA for FY2020 and FY2021, up to the specified maximum. For example, in FY2020, Congress could appropriate the minimum FY2015 baseline of $1.39 billion for suppression operations, as requested by the agencies.78 This amount would be subject to the BCA discretionary limits. But then Congress could appropriate up to an additional $2.25 billion in FY2020, effectively outside of the discretionary limits.79 This means the agencies could be appropriated up to $3.64 billion in total in FY2020, for the same discretionary budget "score" as $1.39 billion. For context, FS and DOI combined received $2.05 billion for suppression purposes in FY2019 ($1.67 billion for FS; $388 million for DOI). Over the past 5 years, FS and DOI combined received $2.16 billion annually on average ($1.74 billion for FS; $428 million for DOI).

The enactment of the wildfire funding fix potentially removes some budget process barriers to providing additional wildfire suppression funds, at least for FY2020 and FY2021. This is because the BCA statutory limits for discretionary spending are only in effect until FY2021. If new limits are statutorily established for any year between FY2022 through FY2027, then the wildfire adjustment would still be applicable. If no new limits are enacted, though, the wildfire adjustment would no longer apply.

It is also unclear if Congress would continue to provide the fire borrowing authority to the agencies once the wildfire adjustment is in effect starting in FY2020. Section 103 of the FY2018 omnibus requires the applicable Secretary, in consultation with the Director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), to "promptly" submit a request to Congress for supplemental appropriations if the amount provided for wildfire suppression operations for a fiscal year is estimated to be exhausted within 30 days. This provision would give Congress notice of the likely need for additional funding but would require additional action from Congress to ensure the agencies have access to funds to enable continued federal services in response to wildfires.

The wildfire funding fix raises several potential concerns for Congress. As one example, FS did not report its 10-year suppression obligation for FY2020 since suppression appropriations are now tied to the FY2015 baseline (DOI reported its 10-year obligation average to be $403 million).80 This may raise concerns related to accountability and oversight of suppression spending. Another concern may be that the FY2015 baseline and the annual adjustment limits are not tied to any inflationary factors. Further, the wildfire funding fix is a temporary procedural change for how Congress funds suppression operations and does not address a variety of other concerns related to suppression costs, such as improving suppression cost forecasting, evaluating the effectiveness of suppression methods, or addressing any of the drivers of increasing suppression costs, among other concerns broadly related to wildland fire management.

Wildfire Hazard Potential Maps

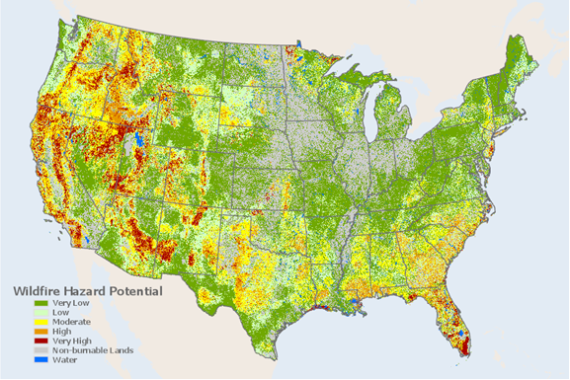

The Fire Modeling Institute, part of FS's Rocky Mountain Research Station, developed a Wildfire Hazard Potential (WHP) index and map to help inform strategic planning and fuel management decisions at a national scale (see Figure 3).81 Using vegetation, fuels, wildfire likelihood, wildfire intensity, and past wildfire location data, the WHP is an index that reflects the relative potential for a wildfire to occur that would then be difficult to suppress or contain.82 Based on this data, FS estimates that approximately 226 million acres of land in the continental United States are classified at high or very high WHP. Of those lands identified at high or very high WHP, 120 million acres (53%) are federal land (58 million acres of NFS lands and 62 million acres of DOI lands), and the remaining 106 million acres (47%) are state, tribal, other public, or private lands.83 According to the index, high or very high WHP reflects fuels that have a higher probability of experiencing extreme fire behavior given certain weather conditions. The WHP data, when paired with appropriate spatial data, can approximate the relative wildfire risk to resources and assets identified from that data.

The FY2018 omnibus directs FS to pair the WHP with the appropriate spatial data and scale for community use. Specifically, Section 210 directs FS to consult with federal and state partners, and relevant colleges and universities to develop, within two years, web-based wildfire hazard severity maps for use at the community level to inform risk management decisions for at-risk communities adjacent to NFS lands or affected by wildland fire.

|

|

Source: FS, https://www.firelab.org/document/classified-2018-whp-gis-data-and-maps. |

Reporting

Both the FY2018 omnibus and the 2018 farm bill require FS and BLM to submit reports to Congress on specified topics related to wildland fire management. Specifically, the FY2018 omnibus requires the Secretary of Agriculture (for FS) or the Secretary of the Interior to submit an annual report within 90 days after the end of a fiscal year in which the wildfire funding fix is used.84 The omnibus also establishes requirements for the report components (§104). The first possible report will be required by December 30, 2021, if the wildfire adjustment is used in the first possible year (FY2020). The Secretaries are to prepare the reports in consultation with the OMB Director. The report is to be available to the public and submitted to the House Committees on Appropriations, the Budget, and Natural Resources and the Senate Committees on Appropriations, the Budget, and Energy and Natural Resources. The report shall document the use of the wildfire funding fix (e.g., specific funding obligations and outlays) and overall wildland fire management spending, analyzed by fire size, costs, regional location, and other factors. The report also shall identify the "risk-based factors" that influenced suppression management decisions and describe any lessons learned. In addition, the law specified that the report shall include an analysis of a "statistically significant sample of large fires" across a variety of measures, including but not limited to: cost drivers and analysis, effectiveness of fuel treatments on fire behavior and suppression costs, and the impact of investments in preparedness activities, among others.

The 2018 farm bill also requires the Secretaries of Agriculture and the Interior to jointly compile and submit a report to Congress on wildfire, insect infestation, and disease prevention on federal land (§8706). The report must be submitted to the House Committee on Agriculture, House Committee on Natural Resources, Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry, and Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. The first report is due within 180 days of enactment of the farm bill (it is due on June 20, 2019) and then annually thereafter. The agencies shall report on the

- number of acres of federal land treated for wildfire, insect and infestation, and disease prevention;

- number of acres of federal land categorized as high or extreme fire risk;

- number of acres and average intensity of wildfires affecting federal land both treated and not treated for wildfire, insect infestation, or disease prevention;

- federal response time for each fire greater than 25,000 acres;

- total timber production on federal land;

- number of miles of roads and trails in need of maintenance;

- maintenance backlog for roads, trails, and recreational facilities on federal land;

- other measures needed to maintain, improve or restore water quality on federal land; and

- other measures needed to improve ecosystem function or resiliency on federal land.

Forest Management and Restoration Programs85

Forest restoration activities seek to establish or reestablish the composition, structure, pattern, and ecological processes and functioning necessary to facilitate resilience and resistance to disturbance events (e.g., insect or disease infestation, catastrophic wildfire, ice or windstorm). For example, forest restoration may include activities such as removing small-diameter trees (called thinning) to reduce tree density, potentially mitigating against the spread of some insect or disease infestations. Or, forest restoration may include prescribed fire to reduce the building up of understory vegetation or biomass, to mitigate the potential for a wildfire to increase in intensity and severity, and to facilitate post-fire recovery.

BLM's authority to conduct restoration projects is derived primarily from FLPMA. FS's authority is derived primarily from its responsibilities to:

- protect the NFS from destruction as specified in the Organic Administration Act of 1897;86

- manage the national forests for multiple use and sustained yield as specified in MUSY; and

- maintain forest conditions designed to secure the maximum benefits and provide for a diversity of plant and animal communities as specified in the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act of 1974, as amended by NFMA.87

Congress also has authorized specific forest restoration programs for FS and BLM, or has authorized forest restoration to be one of many activities or land management objectives for other programs.

The 115th Congress established two new programs for FS (watershed condition framework and water source protection), and amended three existing programs: the Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program (CFLRP, available only for FS), stewardship contracting authority, and the good neighbor authority. Among other provisions, aspects of these programs allow FS and BLM to partner with various stakeholders in different ways to identify forest restoration needs and perform specified forest management and restoration activities. These programs are elements of the FS's "Shared Stewardship" approach to address land management concerns at a landscape-scale and across ownership boundaries.88 These programs are generally perceived as offering opportunities to accelerate forest restoration to mitigate against insect and disease infestations or reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfires to federal lands and surrounding communities.89 In addition, proponents point to other potential benefits to the surrounding communities, such as providing forest products to support local industries, promoting new markets for restoration by-products (e.g., small diameter trees, woody biomass), and fostering collaboration.90 These programs are generally supported by many stakeholders, although some have raised concerns about specific aspects of each program.91

Collaborative Forest Landscape Restoration Program (CFLRP)

Title IV of the Omnibus Public Lands Management Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-11) established the CFLRP to select and fund the implementation of collaboratively developed restoration proposals for priority forest landscapes.92 The collaboration process must include multiple interested persons representing diverse interests and must be transparent and nonexclusive, or meet the requirements for Resource Advisory Committees (RACs, as specified by the Secure Rural Schools and Community Self-Determination Act (SRS)).93 Priority forest landscapes must be at least 50,000 acres and must consist primarily of NFS lands in need of restoration, but may include other federal, state, tribal, or private land within the project area. In addition, the proposal area should be accessible by wood-processing infrastructure. Proposals must incorporate the best available science, and include projects that would maintain or contribute to the restoration of old-growth stands, and restoration treatments that would reduce hazardous fuels, such as thinning small-diameter trees. The proposals may not include plans to establish any new permanent roads, and any temporary roads must be decommissioned. The law requires the publication of an annual accomplishments report and submission of 5-year status reports to specified congressional committees.94

The law authorized the Secretary of Agriculture to select and fund up to 10 proposals for any given fiscal year, but also gave the Secretary the discretion to limit the number of proposals selected based on funding availability. FS has selected and funded 23 proposals since the program was established in FY2010.95 Each selected proposal includes a range of individual projects to implement the proposal's forest restoration goals over the specified time period of the funding commitment. The law established a fund to pay for up to 50% of the costs to implement and monitor proposal projects, and authorizes up to $40 million in annual appropriations to the fund through FY2019. Each selected proposal can receive a funding commitment of up to $4 million per year for up to 10 years to fund project implementation, but appropriations from the fund may not be used to cover any costs related to project planning. The program received $40 million annually in appropriations from FY2014 through FY2019.

CFLRP is generally perceived as successful, achieving progress towards the specified land management objectives as well as contributing to local economies and fostering collaboration.96 Agency staff found the dedicated funding commitment to be one of the most valuable aspects of the program, providing long-term stability and predictability for project implementation and coordination.97 Some may note, however, that this funding commitment may direct resources away from NFS lands in areas not covered by selected projects. While the program provides some economic benefits, some feel it falls short in fostering new markets for smaller-scale wood products or reducing treatment costs.98 In addition, while the program is generally perceived as improving relationships with community stakeholders and fostering collaboration, some note that much of the collaboration had focused on relatively simple and noncontroversial issues and had not made progress towards resolving more complex or controversial issues.99

Summary of Changes and Discussion

Section 8629 of the 2018 farm bill reauthorized the program, and authorized up to $80 million in appropriations annually through FY2023. The law authorized the Secretary of Agriculture to issue a one-time waiver to extend the funding commitment to an existing project for up to an additional 10 years, subject to the project continuing to meet the specified eligibility criteria. The law also added the House and Senate Committees on Agriculture as recipients of the five-year program status reports.

The funding commitment for the 23 selected proposals is set to expire at the end of FY2019, so the reauthorization and extension of eligibility could result in some projects continuing beyond that initial time-frame. In addition, if Congress chooses to appropriate to the new authorization level, it could also result in more projects being selected and funded.100

Good Neighbor Authority

The 2014 farm bill authorized FS and BLM to enter into good neighbor agreements (GNAs) with state governments.101 The program was initially authorized as a temporary pilot on NFS land in Colorado in 2001, before the permanent authorization made it available nationwide for all NFS lands as well as BLM lands.102

Under an approved GNA, states are authorized to do restoration work on NFS and BLM public lands. The authorized restoration services include treating insect- and disease-infested trees, reducing hazardous fuels, and any other activities to restore or improve forest, rangeland, and watershed health. This could include activities such as fish and wildlife improvement projects, commercial timber removal, and tree planting or seeding, among others. The law prohibited treatments in designated wilderness areas, wilderness study areas, or areas where removal of vegetation is prohibited. The 2014 farm bill authorization did not include construction, reconstruction, repair, or restoration of paved or permanent roads, and did not specify any special treatment for any revenue generated through the sale of wood products from the federal lands. While states may perform the work, FS and BLM retain the responsibility to comply with all applicable federal laws regarding federal decisionmaking, including NEPA, as well as approving and marking any silvicultural prescriptions.103

Generally, a Master Agreement (MA) between the state and FS or BLM outlines the general scope of the GNA, and serves as an umbrella for Supplemental Project Agreements (SPAs).104 SPAs are tiered to the MA and outline the specific terms and conditions for project implementation. FS reports that they have executed 48 MAs in 33 states and 105 SPAs in 28 states, covering 82 national forests.105 While many of the GNAs are broad in scope—allowing for the full suite of authorized activities—they typically have a primary emphasis on a specific project type or purpose. This includes timber production (42%), wildlife or fisheries (18%), hazardous fuels management (16%), and other or unspecified activities (19%).

The good neighbor authority is generally perceived as successful, particularly in terms of enhancing state-federal relationships and performing cross boundary restoration work.106 Other benefits include leveraging state resources, although funding and other resource capacity varied across participating states. Some states reported concerns related to the uncertainty of sustained future GNA work, however.107

Summary of Changes and Discussion