North Korea: U.S. Relations, Nuclear Diplomacy, and Internal Situation

North Korea has posed one of the most persistent U.S. foreign policy challenges of the post-Cold War period due to its pursuit of proscribed weapons technology and belligerence toward the United States and its allies. With North Korea’s advances in 2016 and 2017 in its nuclear and missile capabilities under 34-year-old leader Kim Jong-un, Pyongyang has evolved from a threat to U.S. interests in East Asia to a potentially direct threat to the U.S. homeland. Efforts to halt North Korea’s nuclear weapons program have occupied the past four U.S. Administrations, and North Korea is the target of scores of U.S. and United Nations Security Council sanctions. Although the weapons programs have been the primary focus of U.S. policy toward North Korea, other U.S. concerns include North Korea’s illicit activities, such as counterfeiting currency and narcotics trafficking, small-scale armed attacks against South Korea, and egregious human rights violations.

In 2018, the Trump Administration and Kim regime appeared to open a new chapter in the relationship. After months of rising tension and hostile rhetoric from both capitals in 2017, including a significant expansion of U.S. and international sanctions against North Korea, Trump and Kim held a leaders’ summit in Singapore in June 2018. The meeting produced an agreement on principles for establishing a positive relationship. The United States agreed to provide security guarantees to North Korea, which committed to “complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.” The agreement made no mention of resolving significant differences between the two countries, including the DPRK’s ballistic missile program. Trump also said he would suspend annual U.S.-South Korea military exercises, labeling them “provocative,” during the coming U.S.-DPRK nuclear negotiations. Trump also expressed a hope of eventually withdrawing the approximately 30,000 U.S. troops stationed in South Korea.

The history of negotiating with the Pyongyang regime suggests a difficult road ahead, as officials try to implement the Singapore agreement, which contains few details on timing, verification mechanisms, or the definition of “denuclearization,” challenges that the United States has struggled to implement in the previous four major sets of formal nuclear and missile negotiations with North Korea that were held since the end of the Cold War. During that period, the United States provided over $1 billion in humanitarian aid and energy assistance. It is unclear how much assistance, if any, the Trump Administration is planning to commit to facilitate the current denuclearization talks.

The Singapore summit, which was partially brokered by South Korean President Moon Jae-in, has reshuffled regional diplomacy. In particular, the Chinese-North Korean relationship, which had cooled significantly in the past several years, appears to be restored, with Beijing offering its backing to Pyongyang and Kim able to deliver some benefits for Chinese interests as well. North Korea and South Korea also have restored more positive relations.

Kim Jong-un appears to have consolidated authority as the supreme leader of North Korea. Kim has ruled brutally, carrying out large-scale purges of senior officials. In 2013, he announced a two-track policy (the byungjin line) of simultaneously pursuing economic development and nuclear weapons development. Five years later, after significant advances, including successful tests of long-range missiles that could potentially reach the United States, Kim declared victory on the nuclear front, and announced a new “strategic line” of pursuing economic development. Market-oriented reforms announced in 2014 appear to be producing modest economic growth for many citizens. The economic policy changes, however, remain relatively limited in scope. North Korea is one of the world’s poorest countries, and more than a third of the population is believed to live under conditions of chronic food insecurity and undernutrition.

This report will be updated periodically.

North Korea: U.S. Relations, Nuclear Diplomacy, and Internal Situation

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- U.S.-DPRK Relations in 2018

- Advances in North Korea's Weapons of Mass Destruction Programs

- Trump Administration Policy

- 2017: "Maximum Pressure" and Hostile Rhetoric

- 2018: Shift to Diplomacy in Early 2018

- The June 2018 Trump-Kim Singapore Summit

- International and U.S. Sanctions

- U.N. Sanctions

- U.S. Sanctions

- North Korean Demands and Motivations

- History of Nuclear Negotiations

- Agreed Framework

- Missile Negotiations

- Six-Party Talks

- Obama Administration's "Strategic Patience" Policy and Leap Day Agreement

- China's Role

- North Korea's Internal Situation

- Kim Jong-un's Political Position

- North Korea Economic Conditions

- Increasing Access to Information Inside North Korea

- North Korean Security Threats

- North Korea's Military Capabilities

- North Korea's Conventional Military Forces

- Nuclear Weapons

- Ballistic Missiles

- Chemical and Biological Weapons

- Foreign Connections

- North Korea's Illicit Activities

- Narcotics Production and Distribution

- Arms Dealing

- Money Laundering

- North Korea's Human Rights Record

- Human Rights Diplomacy at the United Nations

- North Korean Refugees

- China's Policy on Repatriation of North Koreans

- The North Korean Human Rights Act

- North Korean Overseas Labor

- U.S. Engagement Activities with North Korea

- Official U.S. Assistance to North Korea

- POW-MIA Recovery Operations in North Korea

- Nongovernmental Organizations' Activities

- List of Other CRS Reports on North Korea

Summary

North Korea has posed one of the most persistent U.S. foreign policy challenges of the post-Cold War period due to its pursuit of proscribed weapons technology and belligerence toward the United States and its allies. With North Korea's advances in 2016 and 2017 in its nuclear and missile capabilities under 34-year-old leader Kim Jong-un, Pyongyang has evolved from a threat to U.S. interests in East Asia to a potentially direct threat to the U.S. homeland. Efforts to halt North Korea's nuclear weapons program have occupied the past four U.S. Administrations, and North Korea is the target of scores of U.S. and United Nations Security Council sanctions. Although the weapons programs have been the primary focus of U.S. policy toward North Korea, other U.S. concerns include North Korea's illicit activities, such as counterfeiting currency and narcotics trafficking, small-scale armed attacks against South Korea, and egregious human rights violations.

In 2018, the Trump Administration and Kim regime appeared to open a new chapter in the relationship. After months of rising tension and hostile rhetoric from both capitals in 2017, including a significant expansion of U.S. and international sanctions against North Korea, Trump and Kim held a leaders' summit in Singapore in June 2018. The meeting produced an agreement on principles for establishing a positive relationship. The United States agreed to provide security guarantees to North Korea, which committed to "complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula." The agreement made no mention of resolving significant differences between the two countries, including the DPRK's ballistic missile program. Trump also said he would suspend annual U.S.-South Korea military exercises, labeling them "provocative," during the coming U.S.-DPRK nuclear negotiations. Trump also expressed a hope of eventually withdrawing the approximately 30,000 U.S. troops stationed in South Korea.

The history of negotiating with the Pyongyang regime suggests a difficult road ahead, as officials try to implement the Singapore agreement, which contains few details on timing, verification mechanisms, or the definition of "denuclearization," challenges that the United States has struggled to implement in the previous four major sets of formal nuclear and missile negotiations with North Korea that were held since the end of the Cold War. During that period, the United States provided over $1 billion in humanitarian aid and energy assistance. It is unclear how much assistance, if any, the Trump Administration is planning to commit to facilitate the current denuclearization talks.

The Singapore summit, which was partially brokered by South Korean President Moon Jae-in, has reshuffled regional diplomacy. In particular, the Chinese-North Korean relationship, which had cooled significantly in the past several years, appears to be restored, with Beijing offering its backing to Pyongyang and Kim able to deliver some benefits for Chinese interests as well. North Korea and South Korea also have restored more positive relations.

Kim Jong-un appears to have consolidated authority as the supreme leader of North Korea. Kim has ruled brutally, carrying out large-scale purges of senior officials. In 2013, he announced a two-track policy (the byungjin line) of simultaneously pursuing economic development and nuclear weapons development. Five years later, after significant advances, including successful tests of long-range missiles that could potentially reach the United States, Kim declared victory on the nuclear front, and announced a new "strategic line" of pursuing economic development. Market-oriented reforms announced in 2014 appear to be producing modest economic growth for many citizens. The economic policy changes, however, remain relatively limited in scope. North Korea is one of the world's poorest countries, and more than a third of the population is believed to live under conditions of chronic food insecurity and undernutrition.

This report will be updated periodically.

Introduction

North Korea's threatening behavior; development of proscribed nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons capabilities; and pursuit of a range of illicit activities, including proliferation, has posed one of the most vexing and perpetual problems in U.S. foreign policy in the post-Cold War period. Since North Korea's creation in 1948, the United States has never had formal diplomatic relations with the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK, the official name for North Korea). Successive U.S. Administrations since the early 1990s have sought to use a combination of negotiations, aid, and bilateral and international sanctions to end North Korea's weapons programs, but have not curbed the DPRK's increasing capabilities.

U.S. interests in North Korea encompass grave security, political, and human rights concerns. Bilateral military alliances with the Republic of Korea (ROK, the official name for South Korea) and Japan obligate the United States to defend these allies from any attack from the North. Tens of thousands of U.S. troops based in South Korea and Japan, as well as tens of thousands of U.S. civilians residing in those countries, are stationed within striking range of North Korean intermediate-range missiles. North Korea's rapid advances in its nuclear and long-range missile capabilities may put the U.S. homeland at risk of a DPRK strike. A conflict on the Korean peninsula or the collapse of the government in Pyongyang would have severe implications for the regional—if not global—economy. Negotiations and diplomacy surrounding North Korea's nuclear weapons program influence U.S. relations with all the major powers in the region, particularly with China and South Korea.

At the center of this complicated intersection of geostrategic interests is the task of dealing with a totalitarian regime that is unfettered by many of the norms that govern international relations. A country of about 25 million people, North Korea was founded by Kim Jong-un's grandfather, Kim Il-sung, on an official philosophy of juche (self-reliance) that has led it to resist outside influences, which the regime generally has seen as a potential threat to its rule. The Kim family's near-totalitarian control has helped enable North Korea to resist outside influences, as well as to enter into and then break diplomatic and commercial agreements, to an extent surprising for a relatively small country surrounded by more materially powerful neighbors. Over the past 70 years, the Kims have created one of the world's largest militaries, which acts as a deterrent to outside military intervention and provides Pyongyang with a degree of leverage over foreign powers that has helped the regime extract diplomatic and economic concessions from its neighbors. This same militarization, however—combined with North Korea's often-provocative behavior, opaque policymaking system, and willingness to defy international conventions—also has severely stunted North Korea's economic growth by minimizing its interactions with the outside world.

Despite Kim's apparently solid hold on power and indications that the DPRK economy is strengthening, North Korea's internal situation remains difficult, with most of the population deeply impoverished, and slowly increasing access to information from the outside world potentially could lead to greater public discontent with the regime if growth does not continue.

Congress has both direct and indirect influence on the U.S. policy on North Korea. Through sanctions legislation, Congress has set the terms for U.S. restrictions on trade and engagement with the DPRK, as well as on the President's freedom to ease or lift sanctions against the DPRK. Congress has also passed and repeatedly reauthorized the North Korean Human Rights Act, which calls on the U.S. government to address the DPRK's poor human rights record as well as accept North Korean refugees. Under past nuclear agreements, Congress authorized millions of dollars in energy assistance, at times putting conditions on the provision of aid if it doubted North Korean compliance. In future arrangements, if the United States agrees to provide aid in exchange for DPRK steps on denuclearization, Congress will need to authorize and appropriate funds, as it presumably would if the Administration sought to normalize diplomatic relations as the June 2018 Singapore agreement implies. In its oversight capacity, Congress has held dozens of hearings with both government and private witnesses that question North Korea's capabilities, intentions, human rights record, sanctions evasion, and linkage with other governments, among other topics.

U.S.-DPRK Relations in 2018

Advances in North Korea's Weapons of Mass Destruction Programs

North Korea's rapid advances in missile and nuclear weapons capabilities in 2016 and 2017 have shifted U.S. policymakers' assessment of the regime's threat to the United States. Although North Korea has presented security challenges to U.S. interests for decades, recent tests have demonstrated that North Korea is nearly if not already capable of striking the continental United States with a nuclear-armed ballistic missile. This acceleration in capability made North Korea a top-line U.S. foreign policy and national security problem, outpacing the Middle East and terrorism in the first 18 months of the Trump Administration.

Pyongyang's threats have increased across several domains: nuclear weapons, long-range missile technology, submarine-based missiles, short-range artillery, and cyberattack capacity.1 North Korea conducted three nuclear tests between January 2016 and September 2017. The last test, its sixth, was its most powerful to date. Also in 2017, North Korea conducted multiple tests of missiles that some observers assert demonstrate a capability of reaching the continental United States.2 According to satellite imagery, Pyongyang appears to be developing its submarine-based ballistic missile program that could potentially help it evade U.S. missile defense programs. In December 2017, the Trump Administration publicly blamed North Korea for the cyberattack known as "WannaCry" that crippled computer networks worldwide earlier in the year, demonstrating North Korea's ability to use cyberattacks to disrupt critical operations.

|

|

Sources: Production by CRS using data from ESRI, and the U.S. State Department's Office of the Geographer. Notes: The "Cheonan Sinking" refers to the March 2010 sinking of a South Korean naval vessel that killed 46 sailors. Yeonpyeong Island was attacked in November 2010 by North Korean artillery, killing four South Koreans. |

Trump Administration Policy

2017: "Maximum Pressure" and Hostile Rhetoric

Initially, the Trump Administration responded by adopting a "maximum pressure" policy that sought to coerce Pyongyang into changing its behavior through economic and diplomatic measures. Many of the elements of the officially stated policy were similar to those employed by the Obama Administration: ratcheting up economic pressure against North Korea, attempting to persuade China—by far North Korea's most important economic partner—and others to apply more pressure against Pyongyang, and expanding the capabilities of the U.S.-South Korea and U.S.-Japan alliances to counter new North Korean threats. The Administration successfully led the United Nations Security Council (UNSC)—including North Korea's traditional supporters China and Russia—to pass four new sanctions resolutions that have expanded the requirements for U.N. member states to halt or curtail their military, diplomatic, and economic interaction with the DPRK. Both the Obama and Trump Administrations pushed countries around the globe to significantly cut and/or eliminate their ties to North Korea, often in ways that go beyond UNSC requirements. In a departure from previous Administrations, the Trump Administration emphasized the option of launching a preventive military strike against North Korea.3

Over the course of his presidency, to date, Trump and senior members of his Administration have issued seemingly contradictory statements on North Korea, particularly on the questions of U.S. conditions for negotiations, and whether the United States is prepared to launch a preventive strike against North Korea.4 The shifts in the Administration's public statements at times have created confusion about U.S. policy.

2018: Shift to Diplomacy in Early 2018

In early 2018, following months of outreach by South Korean officials hoping to lower tensions, North Korea accepted an invitation from ROK President Moon Jae-in to attend the 2018 Winter Olympics in PyeongChang, South Korea. Pyongyang sent a high-level delegation, including Kim Jong-un's sister, providing an opening for warmer North-South relations. Shortly afterward, President Trump accepted an invitation, delivered by ROK officials, to meet with Kim. Before the June 2018 Singapore Summit between Kim and Trump, Kim—having never met with a foreign head of state nor left North Korea since becoming leader—met twice with Moon and twice with Chinese President Xi Jinping to set the stage for the unprecedented meeting between U.S. and DPRK heads of state.

Opinions vary on why Kim adjusted course to launch a "charm offensive" after a series of provocations in the previous years. It was likely a combination of several factors that drove Kim to pursue diplomacy. These factors include (1) harsh rhetoric from the Trump Administration that emphasized military confrontation, (2) the increasingly punishing sanctions that limited the North's ability to grow its economy, (3) Moon Jae-in's aggressive outreach to North Korea, including during the 2018 Winter Olympics, and (4) Kim's confidence that he had secured a limited nuclear deterrent against the United States, providing him with additional leverage. Regardless of what spurred him to action, he found willing counterparts in Moon, Xi, and Trump to respond to his overtures.

The June 2018 Trump-Kim Singapore Summit

On June 12, 2018, President Trump and Kim met in Singapore to discuss North Korea's nuclear program, building a peace regime on the Korean Peninsula, and the future of U.S. relations with North Korea. Following the summit, Trump and Kim issued a brief joint statement in which Trump "committed to provide security guarantees to the DPRK," and Kim "reaffirmed his firm and unwavering commitment to complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula."5 The Singapore document is shorter on details than previous nuclear agreements with North Korea and acts as a statement of principles in the following four areas:

- Normalization. The two sides "commit to establish" new bilateral relations.

- Peace. The United States and DPRK agree to work to build "a lasting and stable peace regime."

- Denuclearization. North Korea "commits to work toward complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula."

- POW/MIA Remains. The two sides will work to recover the remains of thousands of U.S. troops unaccounted for during the Korean War.

The agreement made no mention of the DPRK's ballistic missile program. The two sides agreed to conduct follow-on negotiations, to be led on the U.S. side by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo.

In the press conference following the summit, Trump announced that the United States would suspend annual U.S.-South Korea military exercises, which Trump called "war games" and "provocative."6 He said the move, which was not accompanied by any apparent commensurate move by Pyongyang and reportedly surprised South Korea and U.S. military commanders, would save "a tremendous amount of money."7 Trump also expressed a hope of eventually withdrawing the approximately 30,000 U.S. troops stationed in South Korea. The week after the summit, the Defense Department announced that the annual U.S.-South Korea "Ulchi Freedom Guardian" exercises scheduled for August would be cancelled.

Many analysts observed that the agreement covered ground that had been included in previous agreements with North Korea, although those agreements were not made by the DPRK leader himself. Supporters of the agreement point out that the suspension of missile and nuclear tests would reduce North Korea's ability to further advance its capability. Critics of the agreement point out the lack of a timeframe or any reference to verification mechanisms for the denuclearization process, as well as the lack of commitment by Kim to dismantle the DPRK's ballistic missile program.8 The definition of denuclearization, the sequencing of the process of denuclearization, as well as the establishment of a peace regime, and normalization of diplomatic ties were left uncertain.9 Some analysts believe that the regime's attempt to secure a peace treaty ending the Korean War as a precondition for denuclearization talks is a ploy designed to stall for time and gain recognition as a de jure nuclear state.10 Some veterans of previous negotiations with the DPRK caution that North Korea may seek to delay and prolong the process while sanction pressure eases. Although U.S. and international sanctions remain in place, maintaining the political momentum to fully implement existing sanctions is challenging in the midst of an engagement initiative.

International and U.S. Sanctions

U.N. Sanctions

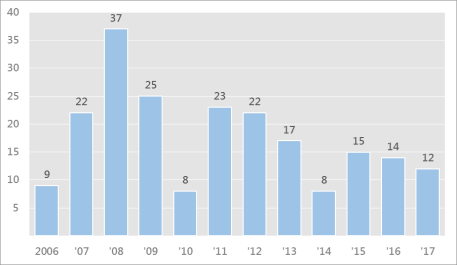

U.N. sanctions have been a major tool for imposing costs on North Korea, as they represent the collective will of the international community in holding the regime to account for pursuing weapons programs in violation of its international obligations, and must be implemented by all member states. Led by the United States, the UNSC in 2006 adopted its first resolution requiring member states to impose sanctions against North Korea, following North Korea's first nuclear test in October of that year. The UNSC has responded by passing additional sanctions resolutions—a total of 10 were adopted between 2006 and December 2017—that have expanded the requirements of U.N. member states to halt or curtail their military, diplomatic, and economic interaction with the DPRK. At first, the sanctions primarily targeted arms sales, trade in materials that could assist North Korea's weapons of mass destruction (WMD) programs, North Korean individuals and entities involved in its WMD activities, and transfers of luxury goods to North Korea.

North Korea's fourth nuclear test in January 2016 spurred a marked expansion of U.N. sanctions. Since then, six sanctions resolutions have been adopted, the most recent in December 2017, expanding sanctions to ban many types of financial interactions with North Korean entities, trade in entire industrial sectors (such as imports of DPRK coal, agriculture and agricultural products, seafood, textiles, and all weapons and military services), and interactions with North Korea and North Koreans in broad classes of activities (such as joint ventures with North Korean entities and the use of North Korean overseas workers). As a result, nearly all of North Korea's major export items are now banned in international markets. According to customs data published by its trading partners, the value of North Korean exports in 2017 declined by more than 30% compared with 2016.11

The Obama and Trump Administrations from early 2016 until at least the spring of 2018 also pushed countries around the globe to significantly cut and/or eliminate their ties to North Korea, often in ways that went beyond UNSC requirements. It is unclear to what extent the Trump Administration has continued this aggressive approach since it began its diplomatic outreach to Pyongyang in the spring of 2018.

|

The Scope of UNSC Sanctions Against North Korea Since 2006, the UNSC incrementally has expanded sanctions against North Korea.12 As of July 2018, UNSC sanctions require member states to, among other steps: Financial Services

Weapons

Transportation and Shipping

North Korean Diplomats

Training

Sectoral Bans

North Korean Overseas Workers

Many of these provisions contain exemptions, most of which are to be decided on a case-by-case basis by the UNSC Sanctions Committee. |

U.S. Sanctions

In addition to leading the sanctions effort in the UNSC, the United States also has imposed its own unilateral sanctions on North Korea in order to exert greater pressure. Presidents George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump have issued a series of executive orders targeting North Korea and North Korean entities. In 2016, the Obama Administration designated North Korea as a jurisdiction of primary money laundering concern, and in 2017, the Trump Administration redesignated North Korea as a state sponsor of terrorism. Since 2015, Congress has passed two North Korea-specific statutes, including the North Korea Sanctions and Policy Enhancement Act of 2016 (P.L. 114-122), and the Korean Interdiction and Modernization of Sanctions Act (Title III of the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act [CAATSA]; P.L. 115-44). Collectively, U.S. sanctions have the following consequences for U.S.-North Korea relations:

- trade is limited to food, medicine, and other humanitarian-related goods, all of which require a license;

- financial transactions are prohibited;

- U.S. new investment is prohibited, and the President has new authority to prohibit transactions involving North Korea's transportation, mining, energy, or financial sectors.

- U.S. foreign aid is minimal, emergency in nature, and administered through centrally funded programs to remove any possibility of the government of North Korea benefiting;

- U.S. persons are prohibited from entering into trade and transaction with those North Korean individuals, entities, and vessels designated by the Department of the Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC);

- foreign financial institutions could become subject to U.S. sanctions for facilitating transactions for designated DPRK entities;

- U.S. persons and entities are prohibited from entering into trade and transactions with Kim Jong-un, the Korean Workers' Party, and others; and

- U.S. travel to North Korea is limited and requires a special validation passport issued by the State Department.

North Korean Demands and Motivations

Over the years, North Korea's stated demands in negotiating the cessation of its weapons programs have repeatedly changed, and have at times included U.S. recognition of the regime as a nuclear weapons state and a peace treaty with the United States as a prerequisite to denuclearization.14 Identifying patterns in North Korean behavior is challenging, as Pyongyang often weaves together different approaches to the outside world. North Korean behavior has vacillated between limited cooperation, including multiple agreements on denuclearization, and overt provocations, including testing several long-range ballistic missiles over the last 20 years and six nuclear devices in 2006, 2009, 2013, 2016, and 2017. Pyongyang's willingness to negotiate has often appeared to be driven by its internal conditions: food shortages or economic desperation can push North Korea to reengage in talks, usually to extract more aid from China or, in the past, from the United States and/or South Korea. North Korea has proven skillful at exploiting divisions among the other five parties and taking advantage of political transitions in Washington to stall the nuclear negotiating process.

The seeming fickleness of North Korea's demands has contributed to debates over the utility of negotiating with North Korea. A small group of analysts argue not only that negotiations are necessary to reduce the chances of conflict, but also that they are feasible, because Kim Jong-un's "real goal is economic development," in the words of one North Korea-watcher.15 Implied in this vision is the concept of a basic bargain in which North Korea would obtain a more secure relationship with the United States, a formal end to the Korean War, as well as economic benefits and sanctions removal in exchange for nuclear weapons and missile dismantlement. Kim Jong-un's increased emphasis on economic development in 2018, discussed below, is often mentioned as a sign that he has made a decision to denuclearize; without breaking free of North Korea's isolation and obtaining relief from sanctions, it will be difficult for him to achieve his economic goals.

Many analysts believe, however, that the North Korean regime, regardless of inducements, will not voluntarily give up its nuclear weapons capability. After years of observing North Korea's negotiating behavior, many analysts now believe that Pyongyang's demands are tactical moves and that North Korea sees having a nuclear capability as essential to regime survival and has no intention of giving up its nuclear weapons in exchange for aid and recognition.16

Pyongyang's frequent statements of its determination to maintain its nuclear weapons program, also have led analysts to doubt the idea that the pledge at the Singapore summit has dramatically shifted its intentions. In April 2010, for instance, North Korea reiterated its demand to be recognized as an official nuclear weapons state and said it would increase and modernize its nuclear deterrent.17 On April 13, 2012, the same day as a failed rocket launch, the North Korean constitution was revised to describe the country as a "nuclear-armed nation." In March 2013, North Korea declared that its nuclear weapons are "not a bargaining chip" and would not be relinquished even for "billions of dollars."18 Following the successful test of the Hwasong-15 intercontinental ballistic missile in November 2017, official North Korean news outlets announced that the DPRK had "finally realized the great historic cause of completing the state nuclear force."19 North Korea has also suggested that it will not relinquish its nuclear stockpile until all nuclear weapons are eliminated worldwide.20

The multinational military intervention in 2011 in Libya, which abandoned its nuclear weapon program in exchange for the removal of sanctions, may have had the undesirable side effect of reinforcing the perceived value of nuclear arms for regime security. North Korean leaders may believe that, without the security guarantee of nuclear weapons, they are vulnerable to overthrow by a rebellious uprising aided by outside military intervention.

Some observers assert that the 2018 Singapore summit conferred a degree of legitimacy on North Korea as a nuclear state, in that the U.S. President sat down with Kim as he would any other world leader and agreed to the "denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula."21 The summit may have satisfied some of North Korea's past demands: the cancelation of U.S.-ROK military exercises, the easing of sanctions implementation, and the prestige conferred by meeting with other heads of state, including the President of the United States.

History of Nuclear Negotiations22

Prior to the Trump Administration's efforts, the United States engaged in four major sets of formal nuclear and missile negotiations with North Korea: the bilateral Agreed Framework (1994-2002), the bilateral missile negotiations (1996-2000), the multilateral Six-Party Talks (2003-2009), and the bilateral Leap Day Deal (2012). In general, the proposed formula for these negotiations has been for North Korea to halt, and in some cases disable, its nuclear or missile programs in return for economic and diplomatic concessions.

Agreed Framework

In 1986, U.S. intelligence detected the startup of a plutonium production reactor and reprocessing plant at Yongbyon that were not subject to international monitoring as required by the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which North Korea joined in 1985. In the early 1990s, after agreeing to and then obstructing International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspections of these facilities, North Korea announced its intention to withdraw from the NPT. According to statements by former Clinton Administration officials, a preemptive military strike on the North's nuclear facilities was seriously considered as the crisis developed. Discussion of sanctions at the UNSC and a diplomatic mission from former President Jimmy Carter persuaded North Korea to engage in negotiations and eventually led to the U.S.-North Korea 1994 Agreed Framework, under which the United States agreed to arrange for North Korea to receive two light water reactor (LWR) nuclear power plants and heavy fuel oil in exchange for North Korea freezing and eventually dismantling its plutonium program under IAEA supervision. The document also outlined a path toward normalization of diplomatic and economic relations as well as security assurances.

The Agreed Framework faced multiple reactor construction and funding delays. Still, the fundamentals of the agreement were implemented: North Korea froze its plutonium program, heavy fuel oil was delivered to the North Koreans, and LWR construction commenced. However, North Korea did not comply with commitments to declare all nuclear facilities to the IAEA and put them under safeguards. In 2002, the George W. Bush Administration confronted North Korea about a suspected secret uranium enrichment program, the existence of which the North Koreans denied publicly.23 As a result, the United States halted heavy fuel oil shipments and construction of the LWRs, which were already well behind schedule. North Korea then expelled IAEA inspectors from the Yongbyon site, announced its withdrawal from the NPT, and restarted its reactor and reprocessing facility after an eight-year freeze.

Missile Negotiations

Separately, in response to congressional pressure due to opposition to the Agreed Framework's terms, the Clinton Administration in 1996 began pursuing a series of negotiations with North Korea that focused on curbing the DPRK's missile program and ending its missile exports, particularly to countries in the Middle East. In September 1999, North Korea agreed to a moratorium on testing long-range missiles in exchange for the partial lifting of U.S. sanctions and a continuation of bilateral talks. Then-Secretary of State Madeleine Albright visited Pyongyang in October 2000 to finalize the terms of a new agreement, under which North Korea would end ballistic missile development and missile exports in exchange for international assistance in launching North Korean satellites. A final agreement proved elusive, however. North Korea maintained its moratorium until July 2006.

Six-Party Talks

Under the George W. Bush Administration, negotiations to resolve the North Korean nuclear issue expanded to include China, South Korea, Japan, and Russia. With China playing host, six rounds of the "Six-Party Talks" from 2003 to 2008 yielded occasional progress, but ultimately failed to resolve the fundamental issue of North Korean nuclear arms. The most promising breakthrough occurred in 2005, with the issuance of a Joint Statement in which North Korea agreed to abandon its nuclear weapons programs in exchange for aid, a U.S. security guarantee, and talks over normalization of relations with the United States. Despite the promise of the statement, the process eventually broke down, primarily due to an inability to come to an agreement on measures to verify North Korea's compliance.

Obama Administration's "Strategic Patience" Policy and Leap Day Agreement

The Obama Administration's policy toward North Korea, often referred to as "strategic patience," was to put pressure on the regime in Pyongyang while insisting that North Korea return to the Six-Party Talks. The main elements of the policy involved insisting that Pyongyang commit to steps toward denuclearization as previously promised in the Six-Party Talks; closely coordinating with treaty allies Japan and South Korea; attempting to convince China to take a tougher line on North Korea; and applying pressure on Pyongyang through arms interdictions and sanctions. U.S. officials stated that, under the right conditions, they would seek a comprehensive package deal for North Korea's complete denuclearization in return for normalization of relations and significant aid, but insisted on a freeze of its nuclear activities and a moratorium on testing before returning to negotiations. This policy was accompanied by large-scale military exercises designed to demonstrate the strength of the U.S.-South Korean alliance.

In addition to multilateral sanctions required by the U.N., the Obama Administration issued several executive orders to implement the U.N. sanctions or to declare additional unilateral sanctions. These included sanctioning entities and individuals involved in the sale and procurement of weapons of mass destruction, as well as those engaging in a number of North Korean illicit activities that help fund the WMD programs and support the regime, including money laundering, arms sales, counterfeiting, narcotics, and luxury goods. Following the November 2014 cyberattack on Sony Pictures Entertainment, which the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) attributed to North Korean hackers, President Obama issued E.O. 13687, enabling the U.S. government to seize the assets of designated DPRK officials and those working on behalf of North Korea.

Despite the overtures for engagement after Obama took office, a series of provocations by Pyongyang halted progress on restarting negotiations. These violations of international law initiated a periodic cycle of action and reaction, in which the United States focused on building consensus at the UNSC and pressuring North Korea through enhanced multilateral sanctions. The major exception to the pattern of mutual recrimination occurred in February 2012, shortly after the death of Kim Jong-il, the previous leader of North Korea and father of Kim Jong-un. The so-called "Leap Day Agreement" committed North Korea to a moratorium on nuclear tests, long-range missile launches, and uranium enrichment activities at the Yongbyon nuclear facility, as well as the readmission of IAEA inspectors. In exchange, the Obama Administration pledged 240,000 metric tons of "nutritional assistance"24 and steps to increase cultural and people-to-people exchanges with North Korea. North Korea scuttled the deal only two months later by launching a long-range rocket, followed by a third nuclear test in February 2013.

China's Role

The U.S. policy of putting economic and diplomatic pressure on North Korea depends heavily on China. In addition to being North Korea's largest trading partner by far—accounting for over 90% of North Korea's total trade since 2015—China also provides food and energy aid that is an essential lifeline for the regime and is one of Pyongyang's few diplomatic partners. Although not supportive of Pyongyang's nuclear goals—as seen in its voting for increasingly restrictive UNSC sanctions—China's overriding priority appears to be to maintain stability on the Korean Peninsula, and therefore to prevent the collapse of North Korea. Analysts assess that Beijing fears the destabilizing effects of a humanitarian crisis, significant refugee flows over its borders, and the uncertainty of how other nations, particularly the United States, would assert themselves on the peninsula in the event of a power vacuum. China also sees strategic value in having North Korea as a "buffer" between China and democratic, U.S.-allied South Korea.

Beijing often has been an obstacle to U.S. policy goals with regard to North Korea. Imposing harsher punishments on North Korea in international fora, such as the U.N., is frequently hindered by China's seat on the UNSC, where Beijing often waters down U.S. efforts to punish North Korea. Chinese companies often have been found to violate sanctions against North Korea, and the Chinese government's enforcement of sanctions has been uneven, with authorities often turning a blind eye to violations.25 However, according to a number of indicators China in 2017 significantly increased its enforcement of UNSC sanctions, perhaps to convince the United States not to follow through on the Trump Administration's threats of a military strike against North Korea. Additionally, Chinese trade with and aid to North Korea is presumed to be a fraction of what it might be if Beijing decided to fully support North Korea, likely due in part to Beijing's desire to appear to the international community as a responsible leader instead of an enabler of a rogue regime. This assumption is a key factor driving the U.S. and South Korean approach, which seeks to avoid pushing China to a place where it feels compelled to provide more diplomatic and economic assistance to North Korea.

Relations between Beijing and Pyongyang suffered after Kim Jong-un's rise to power in 2011. Beijing appeared displeased with Kim Jong-un, particularly after he executed his uncle Jang Song-taek in 2013, who had been the chief interlocutor with China. Chinese President Xi Jinping had several summits with former South Korean President Park Geun-hye, as well as with current President Moon, without meeting with Kim. In addition, an increasing number of Chinese academics called for a reappraisal of China's friendly ties with North Korea, citing the material and reputational costs to China. Chinese public opinion also seemed to turn against North Korea: two-thirds of 8,000 respondents on a Weibo (a Twitter-like Chinese social media platform) poll indicated that they favored a U.S. preemptive airstrike on North Korea's nuclear sites. Content ridiculing Pyongyang's leadership was regularly deleted by state censors.26 In 2017, China agreed to increasingly stringent UNSC sanctions resolutions and to an unprecedented degree appeared to be implementing these measures.

Trump and Kim's aggressive pursuit of a diplomatic opening in 2018 appeared to restore some of the previous closeness of the North Korea-China relationship. After Trump agreed to meet the North Korean leader, Kim traveled outside North Korea for the first time to Beijing, a move that suggested he was seeking to reaffirm a close relationship with China ahead of the meeting. (He traveled to China again in May.) Having achieved some results that China likely perceives as victories—the deescalation of hostilities, the turn to diplomacy and, notably, the cancelation of U.S.-South Korean military exercises that have long irked Beijing—Kim likely has new goodwill and leverage in his relationship with Beijing.

North Korea's Internal Situation

Kim Jong-un's Political Position

Kim Jong-un is the third generation of the Kim family to rule North Korea. His grandfather, Kim Il-sung, North Korea's first ruler, reigned from 1948 until his death in 1994. His father, Kim Jong-il, ruled for nearly 17 years until his death in December 2011, when Kim Jong-un was believed to be in his late 20s.

Although much uncertainty remains about the Pyongyang regime and its priorities given the opaque nature of the state, Kim Jong-un's bold emergence on the global stage in 2018 may be revealing. For many North Korea watchers, Kim's confidence in asserting himself on the world diplomatic stage reinforces the impression that he has consolidated power at the apex of the North Korean regime. Some analysts credit Kim with successfully pursuing a plan to both ensure the survival of his regime but also build up his country's struggling economy. Kim has promoted a two-track policy (the so-called byungjin line) of economic development and nuclear weapons development, explicitly rejecting the efforts of external forces to make North Korea choose between one or the other. Having achieved what some observers call a "limited nuclear deterrent," Kim has pursued better economic opportunities by launching a "charm offensive" to restore better relations with South Korea and China. In addition, Kim has achieved at least a temporary breakthrough with the United States and therefore staved off more punishing sanctions.

Initially, some observers held out hope that the young, European-educated Kim could emerge as a political reformer, but his behavior has not borne out these hopes. In fact, his ruthless drive to consolidate power demonstrates a keen desire to keep the dynastic dictatorship intact. Since he became supreme leader in late 2011, Kim has demonstrated a brutal hand in leading North Korea. He has carried out a series of purges of senior-level officials, including the execution of Jang Song-taek, his uncle by marriage, in 2013. In February 2017, Kim's half-brother Kim Jong-nam was killed at the Kuala Lumpur airport in Malaysia by two assassins using the nerve agent VX; the attack was widely believed to have been authorized by Kim Jong-un.27 South Korean intelligence sources say that over 300 senior military and civilian officials were replaced in Kim's first four years in office.28

Kim Jong-un has displayed a different style of ruling than his father, who generally was considered aloof and remote, gave few public speeches, and attempted to severely limited access to outside influences. Kim has allowed Western influences, such as clothing styles and Disney characters, to be displayed in the public sphere, and he is informal in his frequent public appearances. In a stark change from his father's era, Kim Jong-un's wife was introduced to the North Korean public, although the couple's offspring (they are believed to have three children) remain hidden from the public.29 Analysts depict these stylistic changes as Kim attempting to seem young and modern and to conjure associations with the "man of the people" image cultivated by his grandfather Kim Il-Sung, the revered founder of North Korea.

North Korea Economic Conditions

North Korea is one of the world's poorest countries, with an estimated per capita GDP of under $2,000, about 5% of South Korea's level.30 North Korea is also one of the world's most centrally planned economies. Under Kim, a series of economic policy changes appear to have spurred economic growth and lifted the living standards—including access to a wider array consumer products—for a sizable portion of ordinary North Koreans.31 Increased domestic production, from the loosening of restrictions, along with sanctions-evasion activities, may help to explain how North Korea appears to have weathered the steady tightening of international sanctions since early 2016, in particular the dramatic decline in North Korea's exports from 2016 to 2017, when international sanctions became much stricter.

Under Kim's changes, market principles have been permitted, in a limited manner, to govern some sectors of North Korean business, industry, and agriculture.32 The government has at least partially legalized consumer and business-to-business markets, both of which formerly had a quasi-legal existence, leading to an expansion not only in the number and size of markets but also the ancillary services—such as distribution systems—that enable their operations.33 In his speeches and public factory visits, Kim often emphasizes domestic manufacturing, calling for a shift in consumption from imported to domestically produced goods.34 The marketization process has been facilitated by international trade with China, which since 2016 has accounted for over 90% of North Korea's trade.35

North Korea's agricultural liberalization moves, along with more favorable planting conditions, appear to have contributed to much larger harvests since 2010 than previous decades. In another sign of increased stability in food production, North Korean food prices generally appear to have been stable since around 2012.36 However, even as the elite and those with access to hard currency appear to be faring better, the food security situation for many North Koreans remains tenuous. The United Nations Resident Coordinator for North Korea estimates that over 10 million North Koreans, or over 40% of the population, "continue to suffer from food insecurity and undernutrition."37

Analysts debate the extent to which Kim's changes can be considered "reforms" because it is unclear whether they are as sweeping as those adopted in the past by socialist countries that made a more definitive break from past economic policies. North Korea's penal code, for instance, expressly prohibits private enterprise.38 There is conflicting evidence of the government's willingness to tolerate marketization, particularly if it increases the spread of foreign ideas that the communist party feels could threaten its grip on power. Periodically, reports emerge of official crackdowns in various localities against market activity.39

Many North Koreans have limited access to health care and face significant food shortages. The regime claims it provides universal health care, but most of the country's hospitals are in a dismal state.40 In Pyongyang, health facilities are better than in the rest of the country, but only the elite have access to those facilities. The regime decides where families can live depending on their degree of loyalty to the state, and it tightly controls who can reside in and enter the capital. As a result, few people can get quality medical care, and many North Koreans cannot afford the necessary medications or bribes for their doctors.41

Increasing Access to Information Inside North Korea

Pyongyang appears to be slowly losing its ability to fully control information flows from the outside world into North Korea. Surveys of North Korean defectors reveal that some within North Korea are growing increasingly wary of government propaganda and turning to outside sources of news.42 The North Korean government tries to prevent its citizens from listening to foreign broadcasts. It often attempts to jam foreign stations, including VOA, RFA, and the BBC.43 The government also alters radios to prevent them from receiving outside broadcasts, but defectors report that some citizens have illegal radios—or legal ones that have been modified—to receive foreign programs.44 According to a 2015 survey of North Korean defectors, 29% of them listened to foreign broadcasts while they were in North Korea.45

After a short-lived attempt in 2004, North Korea in 2009 restarted a mobile phone network, in cooperation with the Egyptian telecommunications firm Orascom. The mobile network reportedly had over 3 million subscribers in 2017.46 The regime has allowed increased mobile-phone use, perhaps because it provides better surveillance opportunities. Some reports suggest that North Korean cadres consume foreign media, and that some are even involved in smuggling and selling operations.47 Although illegal to purchase and operate, Chinese cellphones can be used near the border to make international calls.

Although phone conversations in North Korea are monitored, the spread of cell phones likely enables faster and wider dissemination of information. A paper published by the Harvard University Belfer Center in 2015 argues that a campaign to spread information about the outside world within North Korea could produce positive changes in the political system there.48 In the 2015 survey of North Koreans, 28% of respondents reported that they owned domestic mobile phones—and 15% of them said they used their phones to access "sensitive media content."49 Increased access to information could be "the Achilles Heel of the Kim" regime, according to Thae Yong-ho, who served as North Korean deputy ambassador to Britain until his defection in 2016. For decades, the regime has indoctrinated its citizens—using plays, movies, and books—to instill a sense of loyalty to the Kim family and portray the outside world as economically, culturally, and militarily inferior to North Korea. Outside sources of information could inform the people about the reality of their living conditions and encourage them to question their regime.50

North Korean Security Threats

North Korea's Military Capabilities

North Korea fields one of the largest militaries in the world, estimated at 1.28 million personnel in uniform, with another 600,000 in reserves.51 Defense spending may account for as much as 24% of the DPRK's national income, on a purchasing power parity basis.52 The North Korean military has deployed approximately 70% of its ground forces and 50% of its air and naval forces within 100 kilometers of the demilitarized zone (DMZ) border, allowing it to rapidly deploy for full-scale conflict with South Korea.53

North Korea does not have the resources to modernize its entire military, and the U.S. intelligence community has assessed that North Korea is developing its WMD capabilities to offset deficiencies in its conventional forces.54 In particular, North Korea has made the development of nuclear weapons and long-range ballistic missiles a top priority. North Korea also has a large stockpile of chemical weapons and may have biological weapons as well. Analysts assess that in recent years Pyongyang has developed the ability to conduct offensive cyber operations, and the U.S. intelligence community assesses North Korea is among the four countries that "will pose the greatest cyber threats to the United States" in 2018.55 A 2014 Defense White Paper from South Korea's Defense Ministry asserts that North Korea has 6,000 cyber warfare troops.56 The sections below describe what is known from open sources about these programs.

North Korea's Conventional Military Forces

North Korea's conventional military capabilities have atrophied significantly since 1990, due to antiquated weapons systems and inadequate training, but North Korea could still inflict enormous damage on Seoul with artillery and rocket attacks.57 Security experts agree that, if there were a war on the Korean Peninsula, the United States and South Korea would prevail, but at great cost.58 Analysts estimate that North Korean artillery forces, fortified in thousands of underground facilities, could fire thousands of artillery rounds at metropolitan Seoul in the first hour of a war.59 Most North Korean major combat equipment is old and inferior to the modern systems of the U.S. and ROK militaries. With few exceptions, North Korean tanks, fighter aircraft, armored personnel carriers, and some ships are based on Soviet designs from the 1950s-1970s.

To compensate for its obsolete traditional forces, in recent years North Korea has sought to improve its asymmetric capabilities, such as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), offensive cyber operations, special operations forces, GPS jamming, stealth and infiltration, and electromagnetic pulse.60 In recent years, North Korea also has made some advancements in the following areas: long-range artillery, tanks, armored vehicles, infantry weapons, unmanned aerial vehicles, surface-to-air missiles, ballistic missile-capable submarines, and special operations forces.61 In the maritime domain, North Korea constructed two new helicopter-carrier corvettes and may be developing a new, larger model of submarine (perhaps to launch ballistic missiles).

The North Korean military suffers from institutional weaknesses that would mitigate its effectiveness in a major conflict. Because of the totalitarian government system, the North Korean military's command and control structure is highly centralized and allows no independent actions. North Korean war plans are believed to be highly "scripted" and inflexible in operational and tactical terms, and mid-level officers do not have the training and authority to act on their own initiative.62 The country's general resource scarcity affects military readiness in several ways: lack of fuel prevents pilots from conducting adequate flight training, logistical shortages could prevent troops from traveling as ordered, lack of spare parts could reduce the availability of equipment, and food shortages will likely reduce the endurance of North Korean forces in combat, among other effects.

Nuclear Weapons63

U.S. analysts remain concerned about the pace and success of North Korea's nuclear weapons development. In the past, the U.S. intelligence community has characterized the purpose of North Korean nuclear weapons as intended for "deterrence, international prestige, and coercive diplomacy."64 While the United States is in talks with North Korea about abandoning its nuclear weapons program, or "denuclearization," the intelligence community has expressed skepticism of Pyongyang's willingness to carry out that goal. In its most recent assessment to Congress, the DNI said in March 2018 that "Pyongyang's commitment to possessing nuclear weapons and fielding capable long-range missiles, all while repeatedly stating that nuclear weapons are the basis for its survival, suggests that the regime does not intend to negotiate them away."65 North Korean Foreign Ministry official Choe Son Hui said in October 2017 that the North Korean nuclear arsenal is meant to deter attack from the United States and that keeping its weapons is "a matter of life and death for us."66

North Korea in public statements has indicated it was building its nuclear force with an emphasis on developing "smaller, lighter, and more diversified" warheads, signaling a move to produce and deploy nuclear weapons. North Korea has tested nuclear explosive devices six times since 2006, including a hydrogen bomb (or two-stage thermonuclear warhead with a higher yield than previously tested devices) in September 2017 that it said it was perfecting for delivery on an intercontinental ballistic missile. According to U.S. and international estimates, each test produced underground blasts that were progressively higher in magnitude and estimated yield. In early 2018, North Korea announced that it had achieved its goals and would no longer conduct nuclear tests and would close down its test site.67 However, fissile material production and related facilities have not been shuttered.

The North Korean nuclear program began in the late 1950s with cooperation agreements with the Soviet Union on a nuclear research program near Yongbyon. Its first research reactor began operation in 1967. North Korea used indigenous expertise and foreign procurements to build a small (5MW(e)) nuclear reactor at Yongbyon. It was capable of producing about 6 kilograms (kg) of plutonium per year and began operating in 1986.68 Later that year, U.S. satellites detected high explosives testing and a new plant to separate plutonium from the reactor's spent fuel (a chemical reprocessing plant). Over the past two decades, the reactor and reprocessing facility have been alternately operational and frozen under safeguards put in place as the result of the 1994 Agreed Framework and again in 2007, under the Six Party Talks. Since the Six Party Talks' collapse in 2008, North Korea has restarted its 5MW(e) reactor and its reprocessing plant, has openly built a uranium enrichment plant for an alternative source of weapons material, and is constructing a new experimental light water reactor. It is generally estimated in open sources that North Korea had produced between 30 and 40 kilograms of separated plutonium, enough for at least half a dozen nuclear weapons.

While North Korea's weapons program was plutonium-based from the start, intelligence emerged in the late 1990s pointing to a second route to a bomb using highly enriched uranium (HEU). North Korea openly acknowledged a uranium enrichment program in 2009, but has said its purpose is the production of fuel for nuclear power.69 In November 2010, North Korea showed visiting American experts early construction of a 100 MWT light-water reactor and a newly built gas centrifuge uranium enrichment plant, both at the Yongbyon site. The North Koreans claimed the enrichment plant was operational, but this has not been independently confirmed. U.S. officials have said that it is likely other clandestine enrichment facilities exist. Open-source reports, citing U.S. government sources, in July 2018 identified one such site at Kangson.70

It is difficult to estimate warhead and material stockpiles due to lack of transparency and uncertainty about weapons design. U.S. official statements have not given warhead total estimates, but recent scholarly analyses give low, medium, and high scenarios for the amount of fissile material North Korea could produce by 2020, and therefore the potential number of nuclear warheads. If production estimates are correct, the low-end estimate for that study was 20 warheads by 2020, with a maximum of 100 warheads by 2020.71

Ballistic Missiles72

North Korea places a high priority on the continued development of its ballistic missile technology. Despite international condemnation and prohibitions in UNSC resolutions, since Kim Jong-un came to power in 2011 North Korea has conducted over 80 ballistic missile test launches, apparently aimed at increasing the range of its offensive weapons and improving its ability to evade or defeat U.S. missile defense systems. In 2016, North Korea conducted 26 ballistic missile flight tests on a variety of platforms. In 2017, North Korea test launched 18 ballistic missiles (with five failures), including two launches in July and another in November that many ascribe as ICBM tests (intercontinental ballistic missiles). North Korea also has an arsenal of approximately 700 Soviet-designed short-range ballistic missiles, according to unofficial estimates, although the inaccuracy of these antiquated missiles obviates their military effectiveness.73

The U.S. intelligence community has said that the prime objective of North Korea's nuclear weapons program is to develop a nuclear warhead that is "miniaturized" or sufficiently small to be mounted on long-range ballistic missiles, but assessments of progress differ. Miniaturization may require additional nuclear and missile tests. Perhaps the most acute near-term threat to other nations is from the medium-range Nodong missile, which could reach all of the Korean Peninsula and some of mainland Japan, including some U.S. military bases.74 Some experts for years have assessed that North Korea likely has the capability to mount a nuclear warhead on the Nodong missile.75

A December 2015 Department of Defense (DOD) report identifies two hypothetical ICBMs on which North Korea could mount a nuclear warhead and deliver it to the continental United States: the KN-08 and the Taepodong-2. North Korea has publicly displayed what are widely considered mock-ups or engineering models of the KN-08 and KN-14 ICBMs. In 2016, the intelligence community assessed that "North Korea has already taken initial steps toward fielding this [ICBM] system, although the system has not been flight-tested." In July 2017, the DPRK conducted what most have now assessed to be two ICBM tests. A December 2017 Department of Defense report recognized these tests but also said that additional testing may be required.76

North Korea has demonstrated limited but growing success in its medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) program and its submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) test program. Moreover, North Korea appears to be moving slowly toward solid rocket motors for its ballistic missiles. Solid fuel is a chemically more stable option that also allows for reduced reaction and reload times. Successful tests of the Pukguksong-2 (KN-15) solid fuel MRBM in 2017 led North Korea to announce it would now mass-produce those missiles.

A recent focus in North Korea's ballistic missile test program appears to be directed at developing a capability to defeat or degrade the effectiveness of missile defenses, such as Patriot, Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD), and the Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile defense system, all of which are deployed in the region. Some of the 2016 missile tests were lofted to much higher altitudes and shorter ranges than an optimal ballistic trajectory. On reentry, a warhead from such a launch would come in at a much steeper angle of attack and at much faster speed to its intended target, making it potentially more difficult to intercept with missile defenses. North Korea demonstrated in 2017 the ability to launch a salvo attack with more than one missile launched in relatively short order. This is consistent with a possible goal of being able to conduct large ballistic missile attacks with large raid sizes, a capability that could make it more challenging for a missile defense system to destroy each incoming warhead. Finally, North Korea's progress with SLBMs might suggest an effort to counter land-based THAAD missile defenses by launching attacks from positions at sea that are outside the THAAD system's radar field of view, but not necessarily outside the capabilities of Aegis BMD systems deployed in the region.

In the past, the United States has attempted to negotiate limits to North Korea's missile program. After its first long-range missile test in 1998, North Korea and the United States held several rounds of talks on a moratorium on long-range missile tests in exchange for the Clinton Administration's pledge to lift certain economic sanctions. Although Kim Jong-il made promises to Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, negotiators could not conclude a deal. These negotiations were abandoned at the start of the Bush Administration, which placed a higher priority on the North Korean nuclear program. Ballistic missiles were not on the agenda in the Six-Party Talks. In 2006, UNSC Resolution 1718 barred North Korea from conducting missile-related activities. North Korea flouted this resolution with its April 2009 test launch. The UNSC then responded with Resolution 1874, which further increased restrictions on the DPRK ballistic missile program. The 2012 Leap Day Agreement included a moratorium on ballistic missile tests, which North Korea claimed excludes satellite launches. Recent talks have not specifically included references to missiles.

Chemical and Biological Weapons

North Korea has active biological and chemical weapons programs, according to U.S. official reports. According to 2015 congressional testimony by Curtis Scaparrotti, then Commander of U.S. Forces Korea, North Korea has "one of the world's largest chemical weapons stockpiles."77 North Korea is widely reported to possess a large arsenal of chemical weapons, including mustard, phosgene, and sarin gas. Open-source reporting estimates that North Korea has approximately 12 facilities where raw chemicals, precursors, and weapon agents are produced and/or stored, as well as six major storage depots for chemical weapons.78 North Korea is estimated to have a chemical weapon production capability up to 4,500 metric tons during a typical year and 12,000 tons during a period of crisis, with a current inventory of 2,500 to 5,000 tons, according to the South Korean Ministry of National Defense.79 A RAND analysis says that "one ton of the chemical weapon sarin could cause tens of thousands of fatalities" and that if North Korea at some point decides to attack one or more of its neighbors with chemical weapons, South Korea and Japan would be "the most likely targets."80 North Korea is not a signatory to the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), which bans the use and stockpiling of chemical weapons. North Korea's apparent use of VX nerve agent to assassinate Kim's older brother, Kim Jong Nam, in a Malaysian airport in March 2017 focused attention on the North Korean chemical stockpile.

North Korea is suspected of maintaining an ongoing biological weapons production capability. The U.S. intelligence community continues to judge that North Korea has a "longstanding [biological weapons] capability and biotechnology infrastructure" to support such a capability, and "has a munitions production capacity that could be used to weaponize biological agents."81 South Korea's Ministry of National Defense estimated in 2012 that the DPRK possesses anthrax and smallpox, among other weapons agents.82

Foreign Connections

North Korea's proliferation of WMD and missile-related technology and expertise is another serious concern for the United States. Pyongyang has sold missile parts and/or technology to several countries, including Egypt, Iran, Libya, Burma, Pakistan, Syria, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen.83 Sales of missiles and telemetric information from missile tests have been a key source of hard currency for the Kim regime. North Korea assisted Syria with building a nuclear reactor, destroyed by Israel in 2007, that may have been part of a Syrian nuclear weapons program, according to U.S. official accounts.84 The U.N. Panel of Experts has reported transfers of chemical weapons-related materials to Syria by North Korea.

North Korea and Iran have cooperated on the technical aspects of missile development since the 1980s, exchanging information and components.85 Reportedly, scientific advisors from Iran's ballistic missile research centers were seen in North Korea leading up to the December 2012 launch and may have been a factor in its success.86 There are also signs that China has assisted the North Korean missile program, whether directly or through tacit approval of trade in sensitive materials. According to a U.N. panel of experts, a Chinese company sold heavy transport vehicles to North Korea, which the latter appeared to convert into missile transport-erector-launchers showcased in a military parade in April 2012.87

North Korea's Illicit Activities

The North Korean regime engages in a number of illicit activities aimed at earning hard currency to support the Kim regime and its weapons programs, among other goals, and uses a global network of official and commercial entities to support and protect these enterprises.

Narcotics Production and Distribution

The North Korean regime has been involved in the production and trafficking of illicit drugs, counterfeit currency, cigarettes, and pharmaceuticals.88 In general, the United States has not prioritized countering these illicit activities, but they are a source of foreign currency for the regime. One North Korean agency, known as Office 39, reportedly oversees many of the country's illicit dealings—which may generate between $500 million and $1 billion per year.89

The regime produces methamphetamine and it supplies international smuggling networks. In 2013, Thai authorities arrested several individuals who allegedly were conspiring to smuggle 100 kg of North Korean-origin methamphetamines into the United States.90 The DPRK reportedly ramped up its production of illegal narcotics around August 2017—perhaps because tighter sanctions have made it more difficult for the regime to obtain foreign currency—but that is difficult to verify.91 Indeed, it is not always clear who is directing North Korea's illicit activities—in other words, if those activities are being conducted by some state authority or by local criminal gangs.92

Arms Dealing

North Korea has emerged as a provider of cheap Cold War-era weapons, and it has sold arms and equipment to several states, especially to those in the Middle East and North Africa. In August 2016, authorities seized the Jie Shun outside of the Suez Canal, and found over 30,000 rocket-propelled grenades in the vessel. The authorities were acting on a U.S. tip, and the shipment was allegedly destined for the Egyptian military.93 North Korea also has cooperated with Iran and Syria. It has developed ballistic missiles with Iran, and it has shipped weapons and equipment, such as protective chemical suits, to Syria.

Money Laundering

The North Korean regime often relies on front companies—or companies acting on its behalf—so it can mask its illicit dealings and access the international financial system. These companies often are based in China, and some of the business partnerships are set up with the assistance of North Korean diplomats. The companies keep the regime's earnings in overseas bank accounts. They do not repatriate the funds to North Korea, thereby allowing the money to remain in the international financial system, where it is harder to track. In one case, a Chinese company used over 20 front companies—some of which were established in the British Virgin Islands and Hong Kong—to conduct transactions in U.S. dollars for a sanctioned North Korean bank.94

Increasingly, the U.S. government has been sanctioning companies working on behalf of the North Korean regime. In November 2017, the U.S. Treasury Department banned a Chinese bank from the U.S. financial system. The bank, Bank of Dandong, reportedly acted "as a conduit for illicit North Korean financial activity."95 Previously, in September 2005, the Treasury Department identified Banco Delta Asia, located in Macau, as a bank that distributed North Korean counterfeit currency, and helped to launder money for the country's criminal enterprises. The Department ordered that $24 million in North Korean accounts with the bank be frozen. The North Koreans, in response, boycotted the then-ongoing Six-Party Talks for several months until the funds were returned.96

North Korea's Human Rights Record

Although the nuclear issue has dominated interactions with Pyongyang, past Administrations have drawn attention to North Korea's abysmal human rights record. Congress has passed bills and held multiple hearings on the topic.

The plight of most North Koreans is dire. The State Department's annual human rights reports and reports from private organizations have portrayed a little-changing pattern of extreme human rights abuses by the North Korean regime over many years.97 The reports stress a total denial of political, civil, and religious liberties and say that no dissent or criticism of leadership is allowed. Freedoms of speech, the press, and assembly do not exist. There is no independent judiciary, and citizens do not have the right to choose their own government. Reports also document the extensive ideological indoctrination of North Korean citizens.

Severe physical abuse is meted out to citizens who violate laws and restrictions. Multiple reports have described a system of prison camps (kwanliso), often portrayed as concentration camps, that house roughly 100,000 political prisoners, including family members who are considered guilty by association.98 There reportedly are four kwanliso camps in the country plus one complex that remains as a holdover from an earlier camp that was closed. Each camp contains 5,000 to 50,000 political prisoners.99 Reports from survivors and escapees from the camps indicate that conditions are extremely harsh and that many do not survive. According to a Commission of Inquiry (COI) established in 2013 by the United Nations Human Rights Council to investigate North Korea's human rights violations, close to 400,000 prisoners perished while in captivity during the 31-year period.100 Reports cite starvation, disease, executions, and torture of prisoners as a frequent practice. (Conditions for nonpolitical prisoners in local-level "collection centers" and "labor training centers" are hardly better.) The number of political prisoners in North Korea appears to have declined in recent years, likely as a result of high mortality rates in the camps.101

Human Rights Diplomacy at the United Nations

For years, the United Nations has been the central forum calling attention to human rights violations in North Korea. In 2004, the U.N. created a new position, known as the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, to report on the country's human rights conditions. In 2013, the U.N. Human Rights Council established the Commission of Inquiry (COI) to investigate "the systematic, widespread and grave violations of human rights in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea ... with a view to ensuring full accountability, in particular where these violations may amount to crimes against humanity."102 For the next year, the commission conducted public hearings to collect information and shed light on the inhumane conditions in the country. In its final report, the COI stated that the North Korean regime had committed "crimes against humanity" and that the UNSC "should refer the situation in the Democratic People's Republic of Korea to the International Criminal Court" (ICC).103 In 2014, the U.N. General Assembly voted overwhelmingly for a resolution, recommending that the UNSC refer North Korea to the ICC. However, no further action has been taken—allegedly because China and Russia are resistant to bringing the measure to a vote in the UNSC.104 In March 2017, the U.N. Human Rights Council adopted a resolution establishing a repository to archive evidence detailing the country's human rights violations. That evidence could be used to prosecute North Korean officials in the future.105

North Korean Refugees