Fintech: Overview of Innovative Financial Technology and Selected Policy Issues

Advances in technology allow for innovation in the ways businesses and individuals perform financial activities. The development of financial technology—commonly referred to as fintech—is the subject of great interest for the public and policymakers. Fintech innovations could potentially improve the efficiency of the financial system and financial outcomes for businesses and consumers. However, the new technology could pose certain risks, potentially leading to unanticipated financial losses or other harmful outcomes. Policymakers designed many of the financial laws and regulations intended to foster innovation and mitigate risks before the most recent technological changes. This raises questions concerning whether the existing legal and regulatory frameworks, when applied to fintech, effectively protect against harm without unduly hindering beneficial technologies’ development.

The underlying, cross-cutting technologies that enable much of fintech are subject to such policy trade-offs. The increased availability and use of the internet and mobile devices could offer greater convenience and access to financial services, but raises questions over how geography-based regulations and disclosure requirements can and should be applied. Rapid growth in the generation, storage, and analysis of data—and the subsequent use of Big Data and alternative data—could allow for more accurate risk assessment, but raises concerns over privacy and whether individuals’ data will be used fairly. Automated decisionmaking (and the related technologies of machine learning and artificial intelligence) could result in faster and more accurate assessments, but could behave in unintended or unanticipated ways that cause market instability or discriminatory outcomes. Increased adoption of cloud computing allows specialized companies to handle technology-related functions for financial institutions, including providing cybersecurity measures, but this may concentrate financial cyber risks at a relatively small number of nonfinancial companies who may not be entirely comfortable with their regulatory obligations as financial institution service providers. Concerns over cyber risks and whether adherence to cybersecurity regulations ensure appropriate safeguards against those risks permeate all fintech developments.

Fintech deployment in specific financial industries also raises policy questions. The growth of nonbank, internet lenders could expand access to credit, but industry observers debate the degree to which the existing state-by-state regulatory regime is overly burdensome or provides important consumer protections. As banks have increasingly come to rely on third-party service providers to meet their technological needs, observers have debated the degree to which the regulations applicable to those relationships are unnecessarily onerous or ensure important safeguards and cybersecurity. New consumer point-of-sale systems and real-time-payments systems are being developed and increasingly used, and while these systems are potentially more convenient and efficient, there are concerns about the market power of the companies providing the services and the effects on people with limited access to these systems. Meanwhile, cryptocurrencies allow individuals to make payments entirely outside traditional financial systems, which may increase privacy and efficiency but creates concerns over money laundering and consumer protection. Fintech is providing new avenues to raise capital—including through crowdfunding and initial coin offerings—and changing the way companies trade securities and manage investments and may increase the ability to raise funds but present investor protection challenges. Under statute passed by Congress, insurance is primarily regulated at the state level where agencies are considering the implications to efficiency and risk that fintech poses in that industry, including peer-to-peer insurance and insurance on demand. Finally, firms across industries are using fintech to help them comply with regulations and manage risk, which raises questions about what role finetch should play in these systems.

Regulators and policymakers have undertaken a number of initiatives to integrate fintech in existing frameworks more smoothly. They have made efforts to increase communication between fintech firms and regulators to help firms better understand how regulators view a developing technology, and certain regulators have established offices within their organizations to conduct outreach. In another approach, some regulators have announced research collaborations with fintech firms to improve their understanding of new products and technologies. If policymakers determine that particular regulations are unnecessarily burdensome or otherwise ill-suited to a particular technology, they might tailor the regulations, or exempt companies or products that meet certain criteria from such regulations. In some cases, regulators can do so under existing authority, but others might require congressional action.

Fintech: Overview of Innovative Financial Technology and Selected Policy Issues

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Finance, Technology, and Recent Innovation

- Selected Underlying Technological Developments

- Proliferation of Internet Access and Mobile Technology

- Big Data

- Alternative Data

- Automated Decisionmaking and Artificial Intelligence

- Cloud Computing

- Data Security

- Selected Technological Innovations in Finance

- Lending

- Banks and Third-Party Vendor Relationships

- Consumer Electronic Payments

- Real-Time Payments

- Cryptocurrency

- Capital Formation: Crowdfunding and ICOs

- High-Frequency Securities and Derivatives Trading

- Asset Management

- Insurance

- Risk Management and Regtech

- Potential Regulatory Approaches

Figures

Appendixes

Summary

Advances in technology allow for innovation in the ways businesses and individuals perform financial activities. The development of financial technology—commonly referred to as fintech—is the subject of great interest for the public and policymakers. Fintech innovations could potentially improve the efficiency of the financial system and financial outcomes for businesses and consumers. However, the new technology could pose certain risks, potentially leading to unanticipated financial losses or other harmful outcomes. Policymakers designed many of the financial laws and regulations intended to foster innovation and mitigate risks before the most recent technological changes. This raises questions concerning whether the existing legal and regulatory frameworks, when applied to fintech, effectively protect against harm without unduly hindering beneficial technologies' development.

The underlying, cross-cutting technologies that enable much of fintech are subject to such policy trade-offs. The increased availability and use of the internet and mobile devices could offer greater convenience and access to financial services, but raises questions over how geography-based regulations and disclosure requirements can and should be applied. Rapid growth in the generation, storage, and analysis of data—and the subsequent use of Big Data and alternative data—could allow for more accurate risk assessment, but raises concerns over privacy and whether individuals' data will be used fairly. Automated decisionmaking (and the related technologies of machine learning and artificial intelligence) could result in faster and more accurate assessments, but could behave in unintended or unanticipated ways that cause market instability or discriminatory outcomes. Increased adoption of cloud computing allows specialized companies to handle technology-related functions for financial institutions, including providing cybersecurity measures, but this may concentrate financial cyber risks at a relatively small number of nonfinancial companies who may not be entirely comfortable with their regulatory obligations as financial institution service providers. Concerns over cyber risks and whether adherence to cybersecurity regulations ensure appropriate safeguards against those risks permeate all fintech developments.

Fintech deployment in specific financial industries also raises policy questions. The growth of nonbank, internet lenders could expand access to credit, but industry observers debate the degree to which the existing state-by-state regulatory regime is overly burdensome or provides important consumer protections. As banks have increasingly come to rely on third-party service providers to meet their technological needs, observers have debated the degree to which the regulations applicable to those relationships are unnecessarily onerous or ensure important safeguards and cybersecurity. New consumer point-of-sale systems and real-time-payments systems are being developed and increasingly used, and while these systems are potentially more convenient and efficient, there are concerns about the market power of the companies providing the services and the effects on people with limited access to these systems. Meanwhile, cryptocurrencies allow individuals to make payments entirely outside traditional financial systems, which may increase privacy and efficiency but creates concerns over money laundering and consumer protection. Fintech is providing new avenues to raise capital—including through crowdfunding and initial coin offerings—and changing the way companies trade securities and manage investments and may increase the ability to raise funds but present investor protection challenges. Under statute passed by Congress, insurance is primarily regulated at the state level where agencies are considering the implications to efficiency and risk that fintech poses in that industry, including peer-to-peer insurance and insurance on demand. Finally, firms across industries are using fintech to help them comply with regulations and manage risk, which raises questions about what role finetch should play in these systems.

Regulators and policymakers have undertaken a number of initiatives to integrate fintech in existing frameworks more smoothly. They have made efforts to increase communication between fintech firms and regulators to help firms better understand how regulators view a developing technology, and certain regulators have established offices within their organizations to conduct outreach. In another approach, some regulators have announced research collaborations with fintech firms to improve their understanding of new products and technologies. If policymakers determine that particular regulations are unnecessarily burdensome or otherwise ill-suited to a particular technology, they might tailor the regulations, or exempt companies or products that meet certain criteria from such regulations. In some cases, regulators can do so under existing authority, but others might require congressional action.

Finance, Technology, and Recent Innovation

Finance and technological development have been inextricably linked throughout history. (Possibly, quite literally. The technology of writing in early civilization may have developed to record payments and debts.1) As a result, the term fintech is used to refer to a broad set of technologies being deployed across a variety of financial industries and activities. Although there is no consensus on which technologies qualify as new or innovative enough to be fintech, it is generally understood to mean recent innovations to the way a financial activity is performed that are made possible by rapid advances in digital information technology.2 Underlying, cross-cutting technological advancements that enable fintech include increasingly widespread, easy access to the internet and mobile technology; increased data generation and availability and use of Big Data and alternative data; increased use of cloud computing services; the development of algorithmic decisionmaking (and the related technological evolutions toward machine learning and artificial intelligence); and the coevolution of cyber threats and cybersecurity.

The complementary use of these technologies to deliver financial services could potentially create benefits.3 Many technologies aim to create efficiencies in financing, which reduce costs for financial service providers. Certain cost savings may be passed along to consumers through reduced prices. With lower prices, some customers that previously found services too expensive could enter the market. In addition, some individuals and businesses that previously could not access financial services because of price or lack of available financial information could gain access at lower prices or through increased data availability and improved data analysis. Fintech also may allow businesses to reach new customers that were previously restricted by geographic remoteness or unfamiliarity with products and services. Increased accessibility may be especially beneficial to traditionally underserved groups, such as low-income, minority, and rural populations.

However, fintech may also generate risks and result in undesirable outcomes. Predicting how an innovation with only a brief history of use will perform involves uncertainty, particularly without the experience of having gone through a recession. Thus, technologies may not ultimately allocate funds, assess risks, or otherwise function as efficiently and accurately as intended; they may instead generate unexpected losses. Some technologies aim to eliminate or replace a middle man, but in certain cases the middle man may in fact be useful or even necessary. For example, an experienced financial institution or professional may be able to explain and advise consumers on financial products and their risks. In addition, new fintech startups may be inexperienced in complying with consumer-protection laws. These characteristics may increase the likelihood that consumers using financial technology engage in a financial activity and take on risks that they do not fully understand and which unduly expose them to losses. Furthermore, some studies suggest that fintech's use can result in disparate impact on protected groups,4 and that the increasing use of high-speed internet and mobile devices in finance may be leaving behind groups that cannot afford those services and devices.5

As financial activity increasingly uses digital technology, sensitive data are generated. On the one hand, data can be used to assess risks and ensure customers receive the best products and services. On the other hand, data can be stolen and used inappropriately, and there are concerns over privacy. This raises questions over data ownership and control—including consumers' rights and companies' responsibilities in accessing and using data—and whether companies that use and collect data face appropriate cybersecurity requirements.

Given that fintech may produce both positive and negative outcomes, Congress and other policymakers may consider whether existing laws and regulations appropriately foster the development and implementation of potentially beneficial technologies while adequately mitigating the risks those technologies may present. This report examines (1) underlying technological developments that are being used in financial services, (2) selected examples of financial activities affected by innovative technology, and (3) some approaches regulators have used to integrate new technologies or technology companies into the existing regulatory framework. Policy issues that may be of interest to Congress are examined throughout the report. Additional CRS products and resources also are identified throughout the report and in the Appendix. For a detailed examination of how fintech is regulated, see CRS Report R46333, Fintech: Overview of Financial Regulators and Recent Policy Approaches, by Andrew P. Scott.

Selected Underlying Technological Developments

Fintech is generally enabled by advances in general-use technologies that are used to perform financial activities. This section examines certain of these underlying technologies, including their potential benefits and risks, and identifies policy issues related to their use in finance that Congress is considering or may choose to consider.

Proliferation of Internet Access and Mobile Technology6

The proliferation of online financial services has a number of broad implications. One consideration is that online companies can often quickly grow to significant size shortly after entering a financial market.7 This could enable the rapid growth of small fintech startups, possibly through capturing market share from incumbent financial firms. Adopting information technology, however, may require significant investment, which could advantage existing firms if they have increased access to capital. Larger technology firms—including Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google—have started financial services operations, and thus may become competitors to or partners with traditional financial institutions. Some industry experts predict that platforms offering the ability to engage with different financial institutions from a single channel will likely become the dominant model for delivering financial services.8 These developments may raise concerns that offering finance through digital channels could drive industry concentration.

Another consideration in this area involves consumer disclosures for financial products. In the past, voluntary or mandatory disclosures were designed to be delivered through paper. As firms move more of their processes online, they have begun to update these disclosures with electronic formats in mind. Consumers may interact differently with mobile or online disclosures than paper disclosures. Accordingly, firms may need to design online disclosures differently than paper disclosures to communicate the same level of information to consumers.

Possible Issues for Congress

The internet raises questions over what role geography-based financial regulations should play in the future. Many financial regulations are applied to companies and activities based on geographic considerations, as most areas of finance are subject to a dual federal-state regulatory system. For example, nonbank lenders and money transmitters are primarily regulated at the state level in each state in which they operate and are subject to those states' consumer-protection laws.9 Fintech proponents argue the internet facilitates the provision of products and services on a national scale, and 50 separate state regulatory regimes are inefficient when applied to internet-based businesses that are not constrained by geography.10 However, state regulators and consumer advocates assert state regulators' experience and local connection are best situated to regulate nonbank fintech companies.11 An Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) initiative to accept applications for special-purpose bank charters that would allow certain fintechs to enter the national bank regulator regime, and subsequent lawsuits filed by state regulators to block such charters, exemplify this policy debate.12 Another example is the debate over how a bank's geographic assessment area should be defined for the purposes of the Community Reinvestment Act (P.L. 95-128)—a law designed to encourage banks to meet the credit needs of the communities in which they operate—when so many services are delivered over the internet instead of at a physical branch location.13

Another area in which the internet raises concerns is how effective disclosure requirements are if they are sent electronically and read on a screen, when many disclosure forms may have been designed to be delivered and read on paper. Thus, although electronic disclosures can eliminate costs of printing and physically delivering disclosures, they may hinder customers' ability to read and understand them. Currently, financial regulatory agencies are responsible for implementing consumer-disclosure laws. Often, these agencies create either mandatory or safe harbor14 form designs that firms use to comply with these laws. Some financial regulatory agencies are either required or choose to test new consumer disclosures themselves before implementing a new disclosure requirement on the entities they regulate.15 In the past, when most consumer credit origination occurred in person, this testing generally focused on paper delivery. As firms move more of their origination processes online, financial regulatory agencies might consider updating their consumer testing research with this format in mind.

Big Data16

Today, companies can easily collect, cheaply store, and quickly process data, regardless of its size, frequency, type, or location. Big Data commonly refers to the vast amounts and types of data an information technology (IT) system may handle. Big Data data sets share characteristics that require different hardware and software in IT systems to store, manage, and analyze those data. The four characteristics of Big Data are volume, velocity, variety, and variability.17 Volume refers to a data set's extensive size. Velocity refers to the rate of flow for the data coming into, being processed by, and exiting the IT system. Variety refers to the differing types of data in a data set, such as information entered by a company analyst, images, data from a partner database, and data scraped from a website. Variety can also refer to different types of devices and subsystems in an IT system handling the data. Variability refers to the recognition that Big Data data sets can change with regard to the first three attributes. A data set may grow or shrink in volume, data may flow at different velocities, and a data set may include a different variety of data from one point in time to another. Changes in data variability drive IT systems to have a scalable architecture in order to manage the data sets.

Big Data is used to generate insights, support decisionmaking, and enable automation.18 Big Data allows extensive and complex information to be analyzed with new methods (e.g., cloud computing resources, which are discussed in more detail below), leading users to understand and use the data in novel ways. Loan underwriting (evaluating the likelihood that a loan applicant will make timely repayment) is an example from the financial services industry. Loan underwriting has relied on an in-person process, using only a few data sources that might have been months or years old. Big Data enables underwriting to be performed online using a greater variety of more current data sources, potentially allowing for greater speed, accuracy, and confidence in loan decisions, but raises concerns over privacy and questions over what information is appropriate to collect and use.19

In recent years, new technologies have led to the development of new products in the financial services sector.20 For example, as account information has become electronic, some products allow consumers to combine accounts with several financial services providers on a single software platform, sometimes in combination with financial advisory services.21 The underlying technology providers for these platforms are sometimes known as data aggregators, which refers to companies that compile information from multiple sources into a standardized, summarized form. One technology commonly used to collect account data is web scraping, a technique that scans websites and extracts data from them, and in general can be performed without a direct relationship with the website or financial firm maintaining the data.22 As an alternative to web scraping, the financial institution managing the account may provide customer account information through a structured data feed or application program interface (API). Advantages and disadvantages exist when accessing alternative data by API rather than web scraping. For example, in certain circumstances web scraping may be an easier way for companies to gather data because it does not rely on bilateral company agreements, but some industry observers assert that APIs are more secure in terms of cybersecurity and fraud risks.23 Using API banking standards to facilitate data sharing between financial firms is sometimes called open banking. New financial products that take advantage of data aggregation and open banking could provide benefits to consumers by enabling them to manage personal finances, automate or set goals for saving, receive personalized product recommendations, apply for loans, and perform other tasks. However, increasing access to these data may pose data security and privacy risks to consumers.

Possible Issues for Congress

Questions exist about how current laws and regulations should apply to Big Data. Typically, these questions relate to concerns about privacy and cybersecurity. One area of debate is whether data security standards should be prescriptive and government defined or flexible and outcome based. Some argue that a prescriptive approach can be inflexible and harm innovation, but others argue that an outcome-based approach might lead to institutions having to comply with a wide range of data standards.24 In addition, questions exist about whether relevant data security laws continue to cover all sensitive individual financial information, or whether the scope of these laws should be expanded.25

Alternative Data26

Alternative data generally refers to types of data that are not traditionally used by the national consumer reporting agencies to calculate a credit score.27 It can include both financial and nonfinancial data. New technology makes it more feasible for financial institutions to gather alternative data from a variety of sources.

For example, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) included the following list of alternative data in a 2017 Request for Information:

Data showing trends or patterns in traditional loan repayment data.

Payment data relating to non-loan products requiring regular (typically monthly) payments, such as telecommunications, rent, insurance, or utilities.

Checking account transaction and cashflow data and information about a consumer's assets, which could include the regularity of a consumer's cash inflows and outflows, or information about prior income or expense shocks.

Data that some consider to be related to a consumer's stability, which might include information about the frequency of changes in residences, employment, phone numbers or email addresses.

Data about a consumer's educational or occupational attainment, including information about schools attended, degrees obtained, and job positions held.

Behavioral data about consumers, such as how consumers interact with a web interface or answer specific questions, or data about how they shop, browse, use devices, or move about their daily lives.

Data about consumers' friends and associates, including data about connections on social media.28

Alternative data could potentially be used to expand access to credit for consumers, such as currently credit invisible or unscorable consumers,29 but also could create risks related to data security or consumer-protection violations.30 Financial institutions can mitigate some of these risks through data encryption and other robust data governance practices.31 Moreover, some prospective borrowers may be unaware that alternative data has been used in credit decisions, raising privacy and consumer-protection concerns.32 Additionally, alternative data may pose fair lending risks if alternative data elements are correlated with prohibited classes, such as race or ethnicity.33

Alternative data could potentially increase accuracy, visibility, and scorability in credit reporting by including additional information beyond that which is traditionally used. The ability to calculate scores for previously credit invisible or nonscoreable consumers could allow lenders to better determine their creditworthiness. Arguably, using alternative data would potentially increase access to—and lower the cost of—credit for some credit invisible or unscorable individuals by enabling lenders to find new creditworthy consumers.34 However, alternative data could potentially harm some consumers' existing credit scores if it includes negative or derogatory information.35

Possible Issues for Congress

The main statute regulating the credit reporting industry is the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA; P.L. 91-508), enacted in 1970. The FCRA requires "that consumer reporting agencies adopt reasonable procedures for meeting the needs of commerce for consumer credit ... in a manner which is fair and equitable to the consumer, with regard to the confidentiality, accuracy, relevancy, and proper utilization of such information."36 Using alternative data for credit reporting raises FCRA compliance questions. For example, alternative data providers outside of the traditional consumer credit industry may find FCRA data-furnishing requirements burdensome. Some alternative data may have accuracy issues, and managing consumer disputes requires time and resources. These regulations may discourage some organizations from furnishing alternative data, even if the data could potentially help some consumers become scorable or increase their credit scores. In addition, consumers may not know what specific information alternative credit scoring systems use and how to improve the credit scores produced by these models.37

The CFPB and federal banking regulators have been monitoring alternative data developments in recent years, and in December 2019 they released a policy statement on the appropriate use of alternative data in the underwriting process.38 The release followed a February 2017 CFPB request for information from the public about the use of alternative data and modeling techniques in the credit process.39 Information from this request led the CFPB to outline principles for consumer-authorized financial data sharing and aggregation in October 2017.40 These nine principles include, among other things, consumer access and usability, consumer control and informed consent, and data security and accuracy.41 In addition, the CFPB issued its first (and, to date, only) no-action letter in 2017 to the Upstart Network, a company that uses alternative data, such as education and employment history, to make credit and pricing decisions.42 In 2018, the Treasury Department released a report about regulatory recommendations, with a chapter on consumer financial data, including data sharing, aggregation, and other technology issues.43

|

Regulating Fintech: Consumer Protection Agencies The mandate for the consumer protection agencies—CFPB and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC)—is largely to ensure that consumers are not unfairly or deceptively harmed by the practices of businesses under their jurisdiction while maintaining a competitive marketplace. Within the context of fintech, there are trade-offs between these objectives. For instance, encouraging firms to offer new kinds of consumer-friendly financial services can help create a competitive market, but the new products also can create the potential for unforeseen risks to consumers. Similar to other financial regulators, the CFPB and FTC issue and promulgate regulations on issues pertinent to fintech,44 such as payments and data security. In addition, both agencies have created outreach offices. The consumer protection agencies also use enforcement actions as tools to manage the effects of fintech on the financial system. For a detailed examination of the consumer protection agencies' regulatory approaches and initiatives related to fintech, see CRS Report R46333, Fintech: Overview of Financial Regulators and Recent Policy Approaches, by Andrew P. Scott. |

Automated Decisionmaking and Artificial Intelligence45

Performing financial activities often involves making decisions about how to allocate resources (e.g., whether a particular borrower should be given a loan or whether shares of a particular stock should be purchased at the current price) based upon analysis of information (e.g., whether the borrower has successfully paid back loans in the past or how much profit the stock-issuing company made last year). Historically, these complex tasks could only be performed by a human. More recently, technological advances have enabled computers to perform these tasks. This development creates potential benefits and risks, and has a number of financial regulatory implications.

Financial firms have used algorithms—precoded sets of instructions and calculations executed automatically—to enable computers to make decisions for a number of years, notably in the lending and investment management industries. Such automation may produce benefits if algorithmic analysis—perhaps using Big Data and alternative data, discussed previously—is better able to assess risks, predict outcomes, and allocate capital across the financial system than traditional human assessments. Eliminating inefficiencies through such automation could reduce the prices and increase the availability of and access to financial services, including for consumers, small businesses, and the underserved.46

Automation can also create certain concerns, particularly if automated programs may not perform as intended, possibly resulting in market instability or discrimination against protected groups. Algorithms can fail to perform as expected for reasons such as programmer error or unforeseen conditions, potentially producing unexpected losses. Because algorithms can execute actions so quickly and at large scale, those losses can be quite large. An illustrative event is the Flash Crash of May 6, 2010, in which the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell by roughly 1,000 points (and then rebounded) in intraday trading. The event was caused in part by an automated futures selling program that made sales more quickly than anticipated, resulting in tremendous market volatility.47

In addition, automated decisions may result in adverse impacts on certain protected groups in a discriminatory way.48 In lending, for example, these discriminatory outcomes may include higher rates of denial for minority loan applicants than for white applicants with similar incomes and financial histories. Such discrimination can occur for a number of reasons, even if algorithm developers did not intend to discriminate. For example, the data set used to train the lending program is likely historical data of past loan recipients, and minorities may be underrepresented in that sample. By using these data to learn, the algorithm may similarly make fewer loans to underrepresented groups.49

Possible Issues for Congress

Programs enabled with artificial intelligence or machine-learning capabilities (i.e., automated programs that are able to change themselves with little or no human input) raise a number of policy concerns. The programs' complexity and the lack of human input needed to change their decisionmaking processes can make it exceedingly difficult for human programmers to predict what these programs will do and explain why they did it. Under these circumstances, the ability of regulators or other outside parties to understand what a program did, and why, may be limited or nonexistent. This poses a significant challenge for companies using AI programs to ensure they will produce outcomes that comply with applicable laws and regulations, and for regulators to effectively carry out their oversight duties.50 In order to address this black box problem, some observers assert that regulators should set standards for how AI programs are developed, tested, and monitored.51 If Congress decided such standards were necessary, it could encourage or direct financial regulatory agencies to develop them. In addition, it could direct the agencies to implement rules regarding the development and use of AI programs.

Cloud Computing52

Some have jokingly referred to cloud computing as "someone else's computer."53 Although this is a facetious characterization, it succinctly describes the technology's core tenet. Cloud computing users transfer their information from a resource (e.g., hard drives, servers, and networks) that they own to one that they lease. Cloud computing alleviates users from having to buy, develop, and maintain technical resources and recruit and retain the staff to manage those resources. Instead, cloud computing users pay providers who specialize in building and managing such resource infrastructures.

Cloud and high-performance computing architectures are better suited to processing Big Data than desktop computing. For many, this makes Big Data and cloud computing inextricably linked, and many commenters may refer to them interchangeably. Although this may be common practice, it is not technically accurate. Cloud computing refers to the computing resource (e.g., servers, applications, and service), whereas Big Data refers to the data a computing resource may use.

Cloud computing is used extensively by financial institutions, including banks,54 insurers, and securities firms. Most financial firms store and process large amounts of data related to customer accounts and transactions. Typically, they also provide internet-based access to accounts and services through websites and mobile device apps and attract customers with these services. Meeting these business needs requires significant IT infrastructures and capabilities. For some financial companies, it may be less costly to pay a cloud service provider than to do everything in-house.55

Cloud computing introduces certain information security considerations and risks. Because data are not physically under the user's direct control (i.e., the data are no longer on a local, owned or controlled data server), the risk that access to those data may spread beyond intended users may be higher. Cloud providers counter that although they have physical access to the data, they do not necessarily have logical access to the data, nor do they own the data. In other words, they argue that although the data are hosted on their servers, they are encrypted or otherwise segmented from the provider's ability to access them.

Another related potential risk is commonly referred to as the insider threat—the risk that a trusted insider may purposely harm an employer or clients. Although users may limit unauthorized access to their data through encryption, an insider may be able to manipulate the encrypted files in such a manner that the information is kept confidential, but is no longer available. Users would then depend on the provider to restore a functioning backup of the data to resume data access. Or, the provider may offer encryption and key-management services to the user. In doing so, providers keep the data in their servers confidential between clients, but in a way that continues to afford that provider access to the user's data through encryption and decryption protocol maintenance.56

It should be noted that financial institutions that keep IT operations in-house also face the insider threat. However, migrating to cloud computing adds the cloud service provider's employees to the set of people that could pose an insider threat. In addition, a portion of the risk shifts from being internally managed by the financial institution to being externally managed by the cloud service provider. How well a financial institution manages these changing risk exposures depends on the quality of its policies, programs, and relationship with its cloud provider.

Possible Issues for Congress

Policymakers may examine whether the existing regulatory framework and rules appropriately balance the goals of guarding against the risks cloud computing presents to individual financial institutions and systemic stability, while not hindering beneficial innovations. Firms face operational risk (including legal and compliance risks) whether they operate and maintain IT in-house or outsource to a cloud provider.57 Arguably, the risk of system disruptions and failures can be reduced by using a cloud provider with technical specialization in operating, maintaining, and protecting IT systems. Nevertheless, the nature of operational risk exposure changes when an institution adopts cloud computing.

This dynamic potentially raises friction between banks, cloud providers, and regulators regarding how banks' relationships with cloud providers should be regulated. The Bank Services Company Act (BSCA; P.L. 87-856) requires regulators to subject activities performed by bank service providers to the same regulatory requirements as if they were performed by the bank itself.58 This could place substantial regulatory burden on banks and cloud services providers that see potential benefit to working together.59

The BSCA gives bank regulators supervisory authority over service providers.60 Exercising this authority over cloud service providers, however, may raise challenges. At least initially, bank regulators may be unfamiliar with the cloud service industry, and cloud service providers may not be familiar with what is expected during bank-like examinations. The Federal Reserve's April 2019 examination of Amazon Websites Services (AWS; a cloud provider with bank clients) anecdotally illustrates the frictions in this area. Reportedly, AWS was wary of the process, and when examiners asked for additional documents and information, "the company balked, demanding to first see details about how its [AWS's] data would be stored and used, and who would have access and for how long."61

The cloud computing industry could pose risk to broader financial system stability in addition to risk at individual financial firms. Cloud computing resources are pooled, meaning cloud service providers build their resources to service many users simultaneously. This means many financial institutions could be using the same cloud provider, and are likely doing so because the cloud computing industry is highly concentrated at a small number of large providers (as discussed in more detail in the next section). Before cloud computing was available, successful cyberattacks or other technological disruptions would occur in individual institutions' systems. With cloud computing, an incident at one of the main cloud service providers could affect several firms simultaneously, thus affecting large portions of the entire financial system. Large, systemically important banks are reportedly moving significant portions of their operations onto cloud services, which could exacerbate the effects of a disruption at a cloud service provider.62 Certain financial regulators have mandates to ensure financial stability, so policymakers may choose to consider whether their authorities to regulate cloud service providers are appropriately calibrated.

Data Security63

Cybersecurity is a major concern of financial institutions and federal regulators.64 In many ways, it is an important extension of physical security. For example, banks are concerned about both physical and electronic theft of money and other assets, and they do not want their businesses shut down by weather events or denial-of-service attacks.65 Maintaining the confidentiality, security, and integrity of physical records and electronic data held by banks is critical to sustaining the level of trust that allows businesses and consumers to rely on the banking industry to supply services on which they depend.

Enormous amounts of data about individuals' personal and financial information are now generated and stored across numerous financial institutions. This could create additional opportunities for criminals to commit fraud and theft at a scale not previously possible. Instead of stealing credit cards one wallet at a time, someone hacking into a payment system can steal thousands of credit cards at once, and the internet allows stolen credit cards to be sold and used many times. For example, the 2013 Target data breach compromised approximately 70 million credit cards.66 Whereas a traditional criminal method might involve stealing tax refund checks from individual mail boxes, the IRS announced in May 2015 that its computer system was hacked, allowing unknown persons to file up to 15,000 fraudulent tax returns worth up to $50 million total.67 The Equifax breach that occurred between May and July 2017 potentially jeopardized almost 148 million U.S. consumers' identifying information.68

Possible Issues for Congress

To mitigate cybersecurity risks, financial institutions are subject to an array of laws and regulations. The basic authority that federal regulators use to establish cybersecurity standards emanates from the organic legislation that established the agencies and delineated the scope of their authority and functions. In addition, certain state and federal laws—including the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank; P.L. 111-203), the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999 (GLBA; P.L. 106-102), and the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-204)—have provisions related to the cybersecurity of financial services that are often performed by banks. In addition, regulators issue guidance in a variety of forms designed to help banks evaluate their risks and comply with cybersecurity regulations.69

The existing framework was implemented before certain developments in financial technology, and risks related to cybersecurity arguably have increased with digitization's proliferation in finance. Successful hacks of financial institutions, such as those mentioned above, highlight the importance of financial services cybersecurity oversight. The framework governing financial services cybersecurity reflects a complex and sometimes overlapping array of state and federal laws, regulators, regulations, and guidance. However, whether this framework is effective and efficient, resulting in adequate protection against cyberattacks without imposing undue cost burdens on banks, is an open question.70

Concerns about data security aside, generating and analyzing data also raises privacy concerns. Individuals' transactions are increasingly recorded and analyzed by financial institutions. Debates over how financial institutions should be allowed to use or share consumer data between institutions remain unresolved.

For more information on these issues, see CRS Report R44429, Financial Services and Cybersecurity: The Federal Role, by N. Eric Weiss and M. Maureen Murphy; CRS In Focus IF10559, Cybersecurity: An Introduction, by Chris Jaikaran; and CRS Report R45631, Data Protection Law: An Overview, by Stephen P. Mulligan, Wilson C. Freeman, and Chris D. Linebaugh.

Selected Technological Innovations in Finance

When innovative financial technology is developed for a specific financial market, activity, or product, it might raise questions over the degree to which existing applicable laws and regulations foster the potential benefits and protects against potential risks. This section examines certain fintech innovations, including their potential benefits and risks, and identifies related policy issues that Congress is considering or may choose to consider.

Lending71

Traditionally, consumer and small business lenders worked in person with prospective borrowers applying for a new loan. These lenders employed human underwriters to assess prospective borrowers' creditworthiness, determining whether the lender would extend credit to an applicant and under what terms. The underwriting process can be relatively laborious, time consuming, and costly. Dating back to at least 1989, with the debut of a general-purpose credit score called FICO,72 automation has increasingly become a part of the underwriting process.73 In general, automation in underwriting relies on algorithms—precoded sets of instructions and calculations executed by a computer—to determine whether to extend credit to an applicant and under what terms. In contrast, human underwriting relies on a person to use knowledge, experience, and judgement (perhaps informed by a numerical credit score) to make assessments.

More recently, with the proliferation of internet access and data availability, some new lenders—often referred to as marketplace lenders or fintech lenders—rely entirely or almost entirely on online platforms and algorithmic underwriting.74 In addition, the abundance of alternative data about prospective borrowers now available to lenders—either publicly accessible or accessed with the borrower's permission—means lenders can incorporate additional information beyond traditional data provided in credit reports and credit scores into assessments of whether a particular borrower is a credit risk.75 Potentially, more data about a borrower could allow a lender to accurately assess—and thus extend credit to—prospective borrowers for whom traditional information is lacking (e.g., people with thin credit histories)76 or insufficient to make a determination about creditworthiness (e.g., small businesses).77 However, such practices raise questions about what kind of data should be accessible and used in credit decisions and whether its use could result in disparate impacts or other consumer-protection violations. Although fintech lending remains a small part of the consumer lending market,78 it has been growing quickly in recent years. According to the GAO, "in 2017, personal loans provided by these lenders totaled about $17.7 billion, up from about $2.5 billion in 2013."79

Possible Issues for Congress

A general issue underlying many of the policy questions involving fintech in lending is whether the current regulatory framework appropriately fosters these technologies' potential benefits while mitigating the risks they may present. Some commentators argue that current regulation is unnecessarily burdensome or inefficient. Often these criticisms are based largely or in part on the argument that the state-by-state regulatory framework facing nonbank lenders is ill-suited to an internet-based (and hence borderless) industry.80 Opponents of this view assert that state-level licensing and consumer-protection laws, including usury laws (laws that target lending at unreasonably high interest rates), are important safeguards that should not be circumvented.81

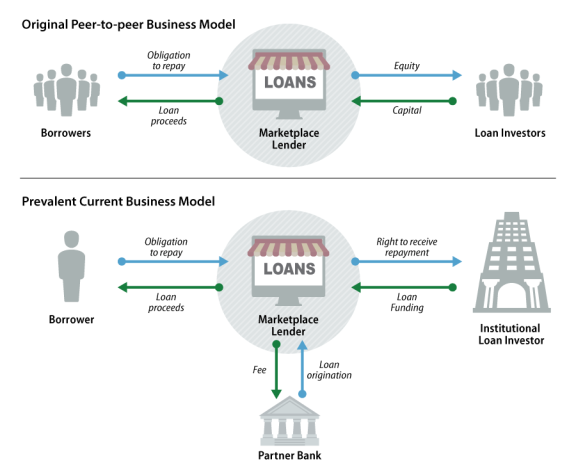

Additional policy questions arise in cases where banks and nonbanks have partnered with each other to issue loans, such as in an arrangement depicted in Figure 1. Fintech companies and banks enter into a variety of such arrangements in which one or the other may build the online, algorithmic platform; do the underwriting on the loan; secure the funding to make the loan; originate it; and hold it on its own balance sheet or sell it to investors.82 These arrangements generally require a bank to closely examine its compliance obligations related to vendor relationship requirements, discussed in more detail in this report's "Banks and Third-Party Vendor Relationships" section. In addition, certain arrangements have raised legal questions concerning federal preemption of state usury laws—specifically, whether federal laws that allow banks to export their home states' maximum interest rates apply to loans that are originated by banks but later purchased by nonbank entities.83 Whether applicable laws and regulations governing these arrangements are appropriately calibrated to ensure availability of needed and beneficial credit or expose consumers to potential harm through the preemption of important consumer protections is a matter of debate.

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service. |

Another area of debate is how consumers will be affected by fintech in lending. Fintech lending proponents argue that, because financial technologies increasingly use quantitative analysis of new data sources, the technologies may expand credit availability to individuals and small businesses in a fair, safe, and less costly way. Thus, these proponents argue that overly burdensome regulation of these technologies could cut off a beneficial credit source to individuals who may have previously lacked sufficient credit access. However, some consumer advocates argue that inexperienced fintech lenders with a relative lack of federal regulatory supervision could inadvertently violate consumer-protection regulations. For example, these lenders may make loan decisions that unintentionally have a disparate impact on protected groups,84 violating fair lending laws.85 Also, when lenders deny a loan application they generally must send a notice to the applicant explaining the reason for the denial, called an adverse action notice.86 Some commentators question how well lenders will understand and thus be able to explain the reasons for an adverse action resulting from a decision made by algorithm.

For more detailed examination of these topics, see CRS Report R44614, Marketplace Lending: Fintech in Consumer and Small-Business Lending, by David W. Perkins; and CRS Report R45726, Federal Preemption in the Dual Banking System: An Overview and Issues for the 116th Congress, by Jay B. Sykes.

Banks and Third-Party Vendor Relationships87

As more banking transactions are delivered through digital channels, insured depository institutions (i.e., banks and credit unions) that lack the in-house expertise to set up and maintain these technologies are increasingly relying on third-party vendors, specifically technology service providers (TSPs), to provide software and technical support. In light of banks' growing reliance on TSPs, regulators are scrutinizing how banks manage their operational risks, the risks of loss related to failed internal controls, people, and systems, or from external events.88 Rising operational risks—specifically cyber risks (e.g., data breaches, insufficient customer data backups, and operating system hijackings)—have compelled regulators to scrutinize banks' security programs aimed at mitigating operational risk. Regulators require an institution that chooses to use a TSP to ensure that the TSP performs in a safe and sound manner, and activities performed by a TSP for a bank must meet the same regulatory requirements as if they were performed by the bank itself.

The Bank Service Company Act (BSCA; P.L. 87-856) and the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA; P.L. 106-102) give insured depository institution regulators a broad set of authorities to supervise TSPs that have contractual relationships with banks. The BSCA directs the federal depository institution regulators to treat all activities performed by contract as if they were performed by the bank and grants them the authority to examine and regulate third-party vendors that provide services to banks, including check and deposit sorting and posting, statement preparation, notices, bookkeeping, and accounting. Section 501 of GLBA requires federal agencies to establish appropriate standards for financial institutions to ensure the security and confidentiality of customer information. Hence, the prudential depository regulators issued interagency guidelines in 2001 that require banks to establish information security programs. Among other things, banks must regularly assess the risks to consumer information (in paper, electronic, or other form) and implement appropriate policies, procedures, testing, and training to mitigate risks that could cause substantial harm and inconvenience to customers. The guidance requires banks to provide continuous oversight of third-party vendors such as TSPs to ensure that they maintain appropriate security measures. The regulators periodically update and have since released additional guidance pertaining to third-party vendors.89

Possible Issues for Congress

Regulation aimed at banks' relationships with third-party vendors such as TSPs has benefits in mitigating operational risks but imposes costs on banks that want to utilize available technologies. Banks, particularly community banks and small credit unions, may find it difficult to comply with regulator standards applicable to third-party vendors. For example, certain institutions may lack sufficient expertise to conduct appropriate diligence when selecting TSPs or to structure contracts that adequately protect against the risks TSPs may present. Some banks may also lack the resources to monitor whether the TSPs are adhering to GLBA and other regulatory or contract requirements. In addition, regulatory compliance costs are sometimes cited as a factor in banking industry consolidation, because compliance costs may be subject to economies of scale that incentivize small banks to merge with larger banks or other small banks to combine their resources to meet their compliance obligations.90

For more detailed examination of this issue, see CRS In Focus IF10935, Technology Service Providers for Banks, by Darryl E. Getter.

|

Regulating Fintech: Depository Regulators The depository regulators—the Federal Reserve, FDIC, OCC, and National Credit Union Administration (NCUA)—face particular fintech-related challenges regarding how to ensure banks and credit unions can efficiently and safely interact with nonbank fintech companies.91 Sometimes fintech companies partner with and offer services to banks or credit unions. Other times, they seek to compete with banks by offering bank or bank-like services directly to customers. In some circumstances, banks themselves can develop their own fintech. Given their broad responsibilities, banking regulators can engage with and respond to fintech in numerous ways, including by amending rules and issuing guidance to clarify how rules apply to new products; supervising the relationships banks form with fintech companies; granting banking licenses to fintech companies: and conducting outreach with new types of firms to facilitate communication between industry and regulators. For a detailed examination of the depository regulators' approaches and initiatives related to fintech, see CRS Report R46333, Fintech: Overview of Financial Regulators and Recent Policy Approaches, by Andrew P. Scott. |

Consumer Electronic Payments92

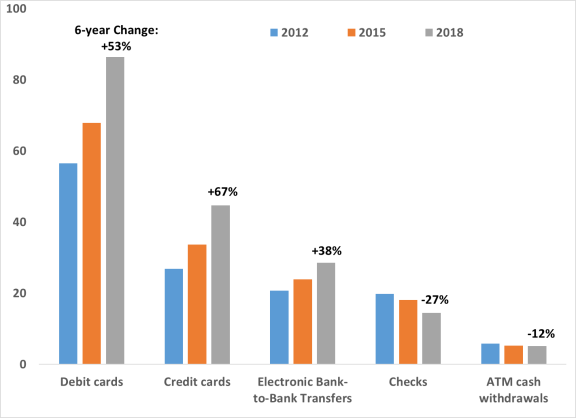

Consumers have several options to make electronic, noncash transactions, as shown in Figure 2. For instance, consumers can make purchases by swiping, inserting, or tapping a card to a payment terminal; they can store their preferred payment information in a digital wallet; or they can use an app to scan a barcode on a mobile phone that links to a payment of their choice. Merchants also enjoy electronic payments innovations that allow them to accept a range of payment types while limiting the need to manage cash.93

|

Figure 2. Consumers Payment Transactions, Selected Years Number of U.S. Transactions, In Billions |

|

|

Source: The 2019 Federal Reserve Payments Study: Initial Data Release, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/paymentsystems/fr-payments-study.htm. |

Despite the technology surrounding noncash payments, electronic payment networks eventually run through the banking system. Accessing these systems typically involves paying fees, which may be burdensome on certain groups. For instance, while most Americans have a bank account, a 2017 survey found that almost a third of those who left the banking system did so because of fees associated with their account.94 While some services, such as prepaid cards, allow individuals to make electronic payments without bank accounts, these options also often involve fees. As a result, cash payments may be the most affordable payment option for certain groups.

Possible Issues for Congress

If electronic payment methods significantly displace cash as a commonly accepted form of payment, that evolution could have both positive and negative outcomes. Proponents of reducing cash use argue that doing so will generate important benefits, such as reducing the costs associated with producing, transporting, and protecting cash. Conversely, opponents of reducing cash usage and acceptance argue that doing so would further marginalize people with limited access to the financial system. Although consumers tend to prefer using debit cards and credit cards, cash maintains an important role in retail payments and person-to-person (P2P) transfers, especially for smaller transactions and lower-income households.95

Electronic payments and cash displacement have various implications for the security and privacy of consumers and merchants. For example, not having cash on store premises can reduce the risk of theft while increasing fees paid to payment card processors.96 Similarly, consumers may be denied services if they only use cash, but if they transition to electronic payments, the privacy offered by cash transactions' anonymous nature is eroded. Further, as more transactions occur over electronic payment systems, the data processed in these transactions are exposed to cybersecurity attacks. Policymakers may examine whether they should encourage or discourage an evolution away from cash based on their assessments of such a change's benefits and costs.

For more information on this topic, see CRS Report R45716, The Potential Decline of Cash Usage and Related Implications, by David W. Perkins.

Real-Time Payments97

There are several steps in the process of completing a payment, involving multiple systems run by various actors. End user payment services accessed by consumers and retailers are only run by the private sector. On the other hand, bank-to-bank payment messaging, clearing, and settlement can currently be executed through systems run privately or by the Federal Reserve.98 The processing of these bank-to-bank electronic payments currently results in payment settlement occurring hours later or on the next business day after a payment is initiated.99 However, advances in technology have made systems featuring real-time payments (RTP)—payments that settle almost instantaneously—possible.

The Federal Reserve plans to introduce an RTP system called FedNow in 2023 or 2024.100 FedNow would be "a new interbank 24x7x365 real-time gross settlement service with integrated clearing functionality to support faster payments in the United States" that "would process individual payments within seconds ... (and) would incorporate clearing functionality with messages containing information required to complete end-to-end payments, such as account information for the sender and receiver, in addition to interbank settlement information."101 FedNow is to be available to all financial institutions with a reserve account at the Federal Reserve.102 It will require banks using FedNow to make funds transferred over it available to their customers immediately after being notified of settlement.103

Several private-sector initiatives are also underway to implement faster payments, some of which would make funds available to the recipient in real time (with deferred settlement) and some of which would provide real-time settlement.104 Notably, the Clearing House introduced its RTP network (with real-time settlement), which is jointly owned by its members (a consortium of large banks), in November 2017; according to the Clearing House, it currently "reaches 50% of U.S. transaction accounts, and is on track to reach nearly all U.S. accounts in the next several years."105

Possible Issues for Congress

According to Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, "the United States is far behind other countries in terms of having real-time payments available to the general public."106

Businesses and consumers would benefit from the ability to receive funds more quickly, particularly as a greater share of payments are made online or using mobile technology. A faster payment system may provide certain other benefits for low-income or liquidity-constrained consumers (colloquially, those living "paycheck to paycheck") who may more often need access to their funds quickly. In particular, many lower-income consumers say that they use alternative financial services, such as check cashing services and payday loans, because they need immediate access to funds.107 Faster payments may also help some consumers avoid checking account overdraft fees.108 Note, however, that some payments that households make would also be cleared faster—debiting their accounts more quickly—than they are in the current system, which could be harmful to some households.

The main policy issue regarding the Federal Reserve and RTP is whether Federal Reserve entry in this market is desirable. Some stakeholders question whether the Federal Reserve can justify creating a RTP system in the presence of competing private systems.109 They fear that FedNow will hold back or crowd out private-sector initiatives already underway and could be a duplicative use of resources.110 The Treasury Department supports Federal Reserve involvement on the grounds that it will help private-sector initiatives at the retail level.111 Others, including many small banks, fear that aspects of payment and settlement systems exhibit some features of a natural monopoly (because of network effects), and, in the absence of FedNow, private-sector solutions could result in monopoly profits or anticompetitive behavior, to the detriment of financial institutions accessing RTPs and their customers (merchants and consumers).112 From a societal perspective, it is unclear whether it is optimal to have a single provider or multiple providers in the case of a natural monopoly, particularly when one of those competitors is governmental. Multiple providers could spur competition that might drive down user costs, but more resources are likely to be spent on duplicative infrastructure.

RTP competition between the Federal Reserve and the private sector also has mixed implications for other policy goals, including innovation, ubiquity, interoperability, equity, and security.113

For more information on this topic, see CRS Report R45927, U.S. Payment System Policy Issues: Faster Payments and Innovation, by Cheryl R. Cooper, Marc Labonte, and David W. Perkins.

Cryptocurrency114

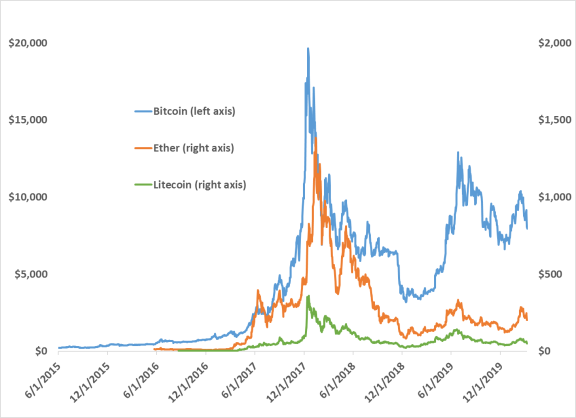

Cryptocurrencies are digital money in electronic payment systems that generally do not require government backing or the involvement of an intermediary, such as a bank. Instead, system users validate payments using public ledgers that are protected from invalid changes by certain cryptographic protocols. In these systems, individuals establish an account identified by a string of numbers and characters (often called an address or public key) that is paired with a password or private key known only to the account holder.115 A transaction occurs when two parties agree to transfer digital currency (perhaps in payment for a good or service) from one account to another. The buying party will unlock the currency used as payment with her private key, allowing some amount to be transferred from her account to the seller's. The seller then locks the currency in her account using her own private key.116 From the perspective of the individuals using the system, the mechanics are similar to authorizing payment on any website that requires an individual to enter a username and password. In addition, companies offer applications or interfaces that users can download onto a device to make transacting in cryptocurrencies more user-friendly. Individuals can purchase cryptocurrencies on exchanges for traditional government-issued money like the U.S. dollar (see Figure 3) or other cryptocurrencies, or they can earn them by doing work for the cryptocurrency platform.

Many digital currency platforms use blockchain technology to validate changes to the ledgers.117 In a blockchain-enabled system, payments are validated on a public or distributed ledger by a decentralized network of system users and cryptographic protocols.118 In these systems, parties that otherwise do not know each other can exchange something of value (i.e., a digital currency) because they trust the platform and its protocols to prevent invalid changes to the ledger.

|

|

Source: Coinbase data, accessed through the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Economic Data website at https://fred.stlouisfed.org/categories/33913. |

Cryptocurrency advocates assert that a decentralized payment system operated through the internet could be faster and less costly than traditional payment systems and existing infrastructures.119 Whether such efficiencies can or will be achieved remains an open question. However, the potential for increased payment efficiency from these systems is promising enough that certain central banks have investigated the possibility of issuing government-backed, electronic-only currencies—called central bank digital currencies (CBDCs)—in such a way that the benefits of certain alternative payment systems could be realized with appropriately mitigated risk. How CBDCs would be created and function are still matters of speculation at this time, and the possibility of their introduction raises questions about central banks' appropriate role in the financial system and the economy.120

Possible Issues for Congress

Whether cryptocurrencies are appropriately regulated is an open question. Cryptocurrency proponents argue that regulation should not stifle the development of a potentially beneficial payment system, while opponents argue that regulation should protect against criminals using cryptocurrency to evade or hide their activities from authorities, or consumers potentially suffering losses from an untested technology. For anti-money laundering purposes, cryptocurrency regulation occurs at the exchanges that allow people to buy and sell cryptocurrencies either for government-backed fiat currencies or other cryptocurrencies. Generally, these exchanges must register as money transmitters at the state level and must report to the U.S. Treasury's Financial Crimes Enforcement Network as money services businesses at the federal level, and are subject to the applicable anti-money laundering requirements those types of companies face. However, cryptocurrency critics warn that their pseudonymous, decentralized nature nevertheless provides a new avenue for criminals to launder money, evade taxes, or sidestep financial sanctions.121

Consumer groups and other commentators are also concerned that digital currency users are inadequately protected against unfair, deceptive, and abusive acts and practices. The way cryptocurrencies are sold, exchanged, or marketed can subject cryptocurrency exchanges or other cryptocurrency-related businesses to generally applicable consumer-protection laws, and certain state laws and regulations are being applied to cryptocurrency-related businesses.122 However, other laws and regulations aimed at protecting consumers engaged in electronic financial transactions may not apply. For example, the Electronic Fund Transfer Act of 1978 (EFTA; P.L. 95-630) requires traditional financial institutions engaging in electronic fund transfers to make certain disclosures about fees, correct errors when identified by the consumer, and limit consumer liability in the event of unauthorized transfers.123 Because no bank or other centralized financial institution is involved in digital currency transactions, EFTA generally has not been applied to these transactions.124

Finally, some central bankers and other experts and observers have speculated that widespread cryptocurrency adoption could affect the ability of the Federal Reserve and other central banks to implement and transmit monetary policy, if one or more additional currencies that were not subject to government supply controls were also prevalent and viable payment options.

For more information on these issues, see CRS Report R45427, Cryptocurrency: The Economics of Money and Selected Policy Issues, by David W. Perkins; CRS Report R45116, Blockchain: Background and Policy Issues, by Chris Jaikaran; and CRS Report R45664, Virtual Currencies and Money Laundering: Legal Background, Enforcement Actions, and Legislative Proposals, by Jay B. Sykes and Nicole Vanatko.

Capital Formation: Crowdfunding and ICOs125

Financial innovation in capital markets has generated new forms of fundraising for firms, including crowdfunding and initial coin offerings. Crowdfunding involves raising funds by soliciting investment or contributions from a large number of individuals, generally through the internet.126 Initial coin offerings (ICO) raise funds by selling digital coins or tokens—generally created and transferred using blockchain technology—to investors; the coins or tokens allow investors to access, make purchases from, or otherwise participate in the issuing company's platform, software, or other project.127 In cases where crowdfunding and ICOs meet the legal definition of a securities offering, they are subject to securities law and regulation by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).128

Four kinds of crowdfunding exist: (1) donation crowdfunding, where contributors give money to a fundraising campaign and receive in return, at most, an acknowledgment; (2) reward crowdfunding, where contributors give to a campaign and receive in return a product or a service; (3) peer-to-peer lending crowdfunding, where investors offer a loan to a campaign and receive in return their capital plus interest; and (4) equity crowdfunding, where investors buy stakes in a company and receive in return company stocks.129 Donation and reward crowdfunding are relatively lightly regulated because contributors are in effect giving without expectation of gaining anything of monetary value in return or preordering a product, respectively. Equity crowdfunding may meet the criteria of a securities offering, and in such cases it is subject to SEC regulation,130 as are certain peer-to-peer lending arrangements in which a security is issued.131

ICOs are a relatively new approach to raising capital.132 A typical ICO transaction involves the issuer selling new digital coins or tokens—also referred to as digital assets or, in cases in which they qualify as securities, digital asset securities—to individual or institutional investors. Investors can often pay in traditional fiat currencies (e.g., U.S. dollars) or cryptocurrencies (e.g., Bitcoin, Ethereum) pursuant to the terms of each individual ICO.133 ICOs are often compared with the traditional financial world's initial public offerings (IPOs) because both are methods companies use to acquire funding. The main difference is that IPO investors receive an equity stake representing company ownership, rather than a digital asset. Coin or token purchasers can generally redeem the coins for goods or services from the issuing enterprise, or hold them as investments in the hope that their value will increase if the company is successful. Although every ICO is different, issuers are generally able to make transfers without an intermediary or any geographic limitation.134

Possible Issues for Congress

Policymakers are now considering whether these new innovations fit well within the existing regulatory framework, or whether the framework should be adapted to address the risks and benefits that they pose. In general, policymakers and regulators have attempted to provide regulatory clarity and investor protection without hindering financial innovation and technological advancements.

Currently, equity crowdfunding debates typically involve questions over how broadly crowdfunding exemptions from certain SEC registration requirements should be applied. Generally, public equity offerings, such as stock issuances, involve a number of costs, including paying an investment bank to price the stock and find investors. In addition, the offering must be registered with the SEC and the company must disclose certain information to investors.135 Crowdfunding may be less costly than traditional public offerings in certain respects and thus might present a new avenue for small businesses without the resources or expertise to complete a traditional IPO to raise funds.

In 2012, Title III of the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act (JOBS Act; P.L. 112-106) created an exemption from registration for internet-based securities that made offerings of up to $1 million (inflation-adjusted) over a 12-month period.136 Certain companies that are still relatively small by some measures may nevertheless not qualify for the exemption, and certain of those companies may find the costs of raising funds through an equity issuance prohibitively high.137 Title III includes certain investor protection provisions, including limitations on investors' investment amounts and issuer disclosure requirements. However, exempting an issuer from registration may weaken investor protections. Thus, what the appropriate criteria should be to allow an equity crowdfunding issuer to forego registration requirements is a matter of debate.

Regarding ICOs, issuers and investors face varying degrees of uncertainty when determining how or if securities laws and regulations apply to them.138 It may not always be clear whether a digital asset is a security subject to SEC regulation. Meanwhile, ICO and digital asset investors—which may include less-sophisticated retail investors, who may not be positioned to comprehend or tolerate high risks—may be especially vulnerable to new types of fraud and manipulation, leading to questions about whether investor protections in this area are adequate. There appear to be high levels of ICO scams and business failures. For example, one 2018 study from the ICO advisory firm Satis Group found that 81% of ICOs are scams and another 11% fail for operational reasons.139 Digital assets may be an attractive method for scammers since transactions in digital assets do not have the same protections as traditional transactions. For example, banks can delay, halt, or reverse suspicious transactions and link transactions with user identity, while many digital asset transactions are generally irreversible.140

The SEC has taken initiatives to address some of these issues. In September 2017, the SEC established a new Cyber Unit and increased its monitoring of and enforcement actions against entities engaged in digital asset transactions.141 Since that time, the SEC has increased the frequency of enforcement actions against issuers—the end recipients of ICO funding—as well as market intermediaries (i.e., broker-dealers and investment managers). In addition to the enforcement activities against entities for noncompliance with securities regulations, the SEC has obtained court orders to halt allegedly fraudulent ICOs.142

|