Marketplace Lending: Fintech in Consumer and Small-Business Lending

Marketplace lending—also called peer-to-peer lending or online platform lending—is a nonbank lending industry that uses innovative financial technology (fintech) to make loans to consumers and small businesses. Although marketplace lending is small compared to traditional lending, it has grown quickly in recent years. In general, marketplace lenders accept applications for small, unsecured loans online and determine applicants’ creditworthiness using an automated algorithm. Often, the loans are then sold—individually or in pieces—directly to investors (although holding the loans on their own balance sheet is not uncommon). More traditional lenders are more apt to use employees to make credit assessments and to have a greater need for office and retail space. Traditional lenders also may hold loans themselves, but when they sell loans they are more apt to package many loans together into large securities rather than to sell a single loan or pieces of a single loan, like marketplace lenders. Due to these differences and to marketplace lending’s lack of industry track record, marketplace lending is facing uncertainty about its advantages, its risks, and how it should be treated by regulators.

Some observers assert that marketplace lending may pose an opportunity to expand the availability of credit to individuals and small businesses in a fair, safe, and efficient way. Marketplace lenders may have lower costs than traditional lenders, potentially allowing them to make more small loans than would be profitable for traditional lenders. In addition, some observers believe the accuracy of credit assessments will improve by using more data and advanced statistical modeling, as marketplace lenders do through their automated algorithms, leading to fewer delinquencies and write-offs. They argue that using more comprehensive data could also allow marketplace lenders to make credit assessments on potential borrowers with little or no traditional credit history.

Other observers warn about the uncertainty surrounding the industry and the potential risks marketplace lending poses to borrowers, loan investors, and the financial system. The industry only began to become prevalent during the current economic expansion and low-interest-rate environment, so little is known about how it will perform in other economic conditions. Many marketplace lenders do not hold the loans they make themselves and earn much of their revenue through origination and servicing fees, which potentially creates incentives for weak underwriting standards. Finally, some observers argue that lack of oversight may allow marketplace lenders to engage in unsafe or unfair lending practices.

Marketplace lenders are subject to existing federal and state regulations related to lending and security issuance, and some observers assert that the existing system is appropriate for regulating this lending. However, existing regulations were developed and implemented largely prior to the emergence of marketplace lending. Some observers argue that current regulation is unnecessarily burdensome or inefficient. By contrast, others argue that regulatory gaps and weaknesses exist and regulation should be strengthened. In addition, there is some uncertainty surrounding exactly how certain aspects of federal and state laws and regulations may be applied to marketplace lenders. Congress may consider policy issues related to these debates and uncertainties.

The evolution of the regulatory environment facing marketplace lenders is just one development that likely will occur in coming years. Traditional lenders that compete with marketplace lenders will adapt to the market entrants and market conditions, perhaps adopting certain marketplace lender technologies and practices. In addition, marketplace lending has not been through an entire economic cycle, and rising interest rates or the onset of a recession likely will reveal certain strengths and weaknesses of marketplace lending.

Marketplace Lending: Fintech in Consumer and Small-Business Lending

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Overview of Marketplace Lending

- Business Models

- Size and Growth

- Participants

- Marketplace-Lending Companies

- Funding Providers

- Banks

- Potential Opportunities

- Potential Industry Advantages

- Potential Beneficial Outcomes

- Potential Risks

- Potential Sources of Risk

- Potential Adverse Outcomes

- Regulation

- Existing Regulatory Framework

- Federal Securities Regulation

- Federal Consumer Protection Regulation

- State Laws

- Regulatory Issues

- Federal and State Regulation: Debate and Uncertainty

- Federal Supervisory Authority

- "Originate-to-Sell" and the Risk-Retention Rule

- Potential Future Developments

- Traditional Lender Response

- Performance in Recession

- Regulatory Developments

- Conclusion

Appendixes

Summary

Marketplace lending—also called peer-to-peer lending or online platform lending—is a nonbank lending industry that uses innovative financial technology (fintech) to make loans to consumers and small businesses. Although marketplace lending is small compared to traditional lending, it has grown quickly in recent years. In general, marketplace lenders accept applications for small, unsecured loans online and determine applicants' creditworthiness using an automated algorithm. Often, the loans are then sold—individually or in pieces—directly to investors (although holding the loans on their own balance sheet is not uncommon). More traditional lenders are more apt to use employees to make credit assessments and to have a greater need for office and retail space. Traditional lenders also may hold loans themselves, but when they sell loans they are more apt to package many loans together into large securities rather than to sell a single loan or pieces of a single loan, like marketplace lenders. Due to these differences and to marketplace lending's lack of industry track record, marketplace lending is facing uncertainty about its advantages, its risks, and how it should be treated by regulators.

Some observers assert that marketplace lending may pose an opportunity to expand the availability of credit to individuals and small businesses in a fair, safe, and efficient way. Marketplace lenders may have lower costs than traditional lenders, potentially allowing them to make more small loans than would be profitable for traditional lenders. In addition, some observers believe the accuracy of credit assessments will improve by using more data and advanced statistical modeling, as marketplace lenders do through their automated algorithms, leading to fewer delinquencies and write-offs. They argue that using more comprehensive data could also allow marketplace lenders to make credit assessments on potential borrowers with little or no traditional credit history.

Other observers warn about the uncertainty surrounding the industry and the potential risks marketplace lending poses to borrowers, loan investors, and the financial system. The industry only began to become prevalent during the current economic expansion and low-interest-rate environment, so little is known about how it will perform in other economic conditions. Many marketplace lenders do not hold the loans they make themselves and earn much of their revenue through origination and servicing fees, which potentially creates incentives for weak underwriting standards. Finally, some observers argue that lack of oversight may allow marketplace lenders to engage in unsafe or unfair lending practices.

Marketplace lenders are subject to existing federal and state regulations related to lending and security issuance, and some observers assert that the existing system is appropriate for regulating this lending. However, existing regulations were developed and implemented largely prior to the emergence of marketplace lending. Some observers argue that current regulation is unnecessarily burdensome or inefficient. By contrast, others argue that regulatory gaps and weaknesses exist and regulation should be strengthened. In addition, there is some uncertainty surrounding exactly how certain aspects of federal and state laws and regulations may be applied to marketplace lenders. Congress may consider policy issues related to these debates and uncertainties.

The evolution of the regulatory environment facing marketplace lenders is just one development that likely will occur in coming years. Traditional lenders that compete with marketplace lenders will adapt to the market entrants and market conditions, perhaps adopting certain marketplace lender technologies and practices. In addition, marketplace lending has not been through an entire economic cycle, and rising interest rates or the onset of a recession likely will reveal certain strengths and weaknesses of marketplace lending.

Introduction

This report examines marketplace lending, a type of nonbank lending done by online companies that make loans to consumers and small businesses using innovative technology. The marketplace-lending industry has experienced rapid growth and, with that growth, an increase in scrutiny by regulators, the media, and the public. Marketplace lending could create both benefits and risks, and it raises several policy questions.

This report begins by providing an overview of the marketplace-lending industry. The report then analyzes the potential benefits and risks the industry creates. Next, it describes existing regulation relevant to marketplace lending before examining some regulatory issues surrounding the industry. The report concludes with an examination of possible future developments.

Overview of Marketplace Lending

Marketplace lending refers to certain online lending that relies on innovative financial technology, or fintech.1 The industry is rapidly growing and evolving, and companies are continually developing new variants of existing business models.2 In addition, incumbent lenders—including banks and nonbanks—are using and increasingly adopting some of the technologies and practices of marketplace lending to varying degrees. For these reasons, it is difficult to construct a concise definition that neatly divides all lending into either marketplace or not marketplace. Instead, this report will examine certain characteristics central to the business model of marketplace lenders, compare and contrast the characteristics with those of more traditional lenders, and examine issues regarding future performance and regulation of the marketplace-lending industry.

Marketplace lending combines all of the following characteristics:

- Loans are made to individuals and small businesses.

- Marketplace lenders operate almost entirely online, with no physical retail space.

- Underwriting is almost entirely automated and algorithmic.

- Marketplace lenders are funded by issuing equity or selling loans to investors.

This report will treat marketplace lending as lending in which all of these characteristics are the basis for the lender's business model. Additionally, the following characteristics are common and important to an examination of the current state of the industry, although they are not universal across all marketplace lending:

- Loans are unsecured, small, and short term.

- Loans are sold whole or in pieces as a security or "note" backed by a single loan, as opposed to the more traditional practice of pooling many loans together into a security backed by payments made across that portfolio of loans.

These characteristics can be found across all types of lenders. For example, many banks and nonbank lenders may offer online and automated application processes. However, lending done by a bank will not be considered marketplace lending, because bank business models also involve physical retail locations, loan officers to underwrite loans, deposit-taking as a funding source, and a diverse menu of available financial services. Other forms of nonbank lending deviate from marketplace lending models in ways that include pooling many loans together into a single security.3

The distinction between marketplace lending and traditional forms of lending is becoming increasingly blurred as marketplace lenders expand their activities and traditional lenders adopt the practices of marketplace lenders. Nevertheless, the characteristics listed above are pertinent to discussion of benefits, risks, regulatory issues, and possible future developments in consumer and small-business lending related to innovative financial technology and so will be the focus of this report.

Business Models

Marketplace lenders typically make relatively small and short-term loans that are unsecured by collateral.4 Most companies focus on a certain type of loan, such as personal, small business, or student loans, and the borrowers are usually individuals or small businesses. Interest rates on loans made through marketplace lending vary depending on the assessed creditworthiness of the borrower, but unsecured loans generally have relatively high interest rates regardless of the type of lender.5

Marketplace lenders rely solely on automated, online processes. A typical application process would require prospective borrowers to fill out online forms that provide information about themselves (such as employment status and income) and the size, term, and purpose of the loan they are seeking. Applicants also may be required to give permission to the lender to access other information, such as credit scores. An algorithm uses this information and perhaps other publicly available information to assess the creditworthiness of the potential borrowers. Borrowers are then quoted a rate, and, if borrowers accept, they can have the money within a few days. Many observers assert that the process is shorter and more convenient than traditional loan applications.6

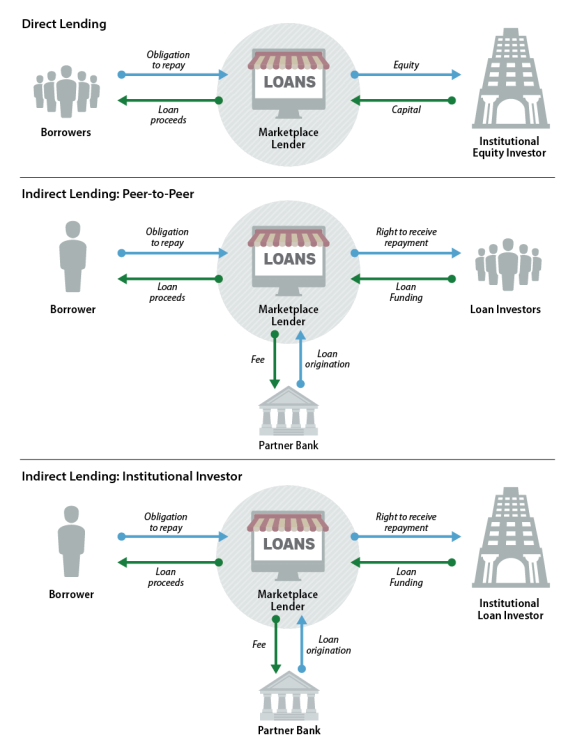

Marketplace lenders may hold loans once they have been originated or sell the loans to investors. Direct lenders, or balance-sheet lenders, hold most or all of the loans on their own balance sheets, earn the interest on the loans, and face the credit risk if a borrower does not repay, as shown in the top panel of Figure 1. These lenders typically raise funds to make loans by issuing equity to large investors, such as hedge funds and venture capitalists. Direct lenders are increasingly using new methods to raise funds, which make these lenders increasingly resemble more established nonbank lenders. In cases where an online lender securitized many loans that the lender originated, the lender would not be engaged in marketplace lending as described in this report.

Indirect lenders, or platform lenders, rarely hold loans themselves. Instead, they match individual loans to investors that want to purchase the loans, as shown in the bottom two panels of Figure 1. Prospective loan investors—individuals, financial institutions, or investment funds—select loans with interest rates and risk profiles that they want to own to earn interest. When investors have committed to fund a loan, marketplace lenders use a partner bank to originate the loan.7 The marketplace lender buys the loan from the bank and then sells the loan to the investors, often using an instrument called a payment dependent note, which directs payments to the investor based on the performance of the loan. Generally, these marketplace lenders earn origination and servicing fees on the loan and do not face losses in the event of a default.8

|

|

Source: Congressional Research Service (CRS). Note: This figure does not contain an exhaustive list of marketplace lending business models. These are stylized examples that illustrate some common lending and funding practices. |

Size and Growth

Marketplace lending is small relative to total personal and small-business credit outstanding in the United States. According to one industry data provider, marketplace lenders originated almost $26 billion of loans in 2017, an increase of 34% from the $19 billion originated in 2016.9 However, this figure accounted for less than 1% of the total consumer and small-business loan market, as total consumer credit outstanding was more than $3.8 trillion and nonfinancial, noncorporate business loans outstanding—a category that includes many small-business loans—totaled about $1.5 trillion at the end of 2017.10

However, growth in recent years has been rapid. Marketplace origination experienced an annual compounding growth rate of 163% between 2011—when originations were $473 million—and 2015.11 One market analysis predicts originations could grow to $90 billion by 2020.12 Another analysis identified $386 billion in personal and small-business lending that potentially could migrate from banks to marketplace lenders by sometime between 2020 and 2025.13

Participants

The borrowers in the marketplace lending industry are individuals and small businesses. Making the loan involves the marketplace lender, funding providers, and sometimes banks.

Marketplace-Lending Companies

One online compendium lists 111 marketplace lenders operating in the United States but does not claim to be exhaustive.14 Many of these marketplace lenders are still small, but a few prominent companies are originating billions of dollars of loans. For example, Lending Club focuses on personal loans and originated $9.0 billion of loans in 2017,15 and OnDeck is a small-business lender that originated $2.1 billion in loans in 2017.16

Funding Providers

Funding for the loans comes from both individuals and large institutional investors. Initially, the industry mostly relied on peer-to-peer lending, in which individuals invested small amounts to purchase a piece of a loan. However, large institutional investors—such as hedge funds and private investment firms—have become an increasingly important source of funding in recent years through whole loan purchases and equity investments. Matching specific loans to individual investors was initially a very distinctive characteristic of marketplace lending, and the migration toward institutional funding makes the industry increasingly similar to incumbent nonbank lenders.

This transformation likely has several causes. Marketplace lenders had to establish a track record of low delinquency and charge-off rates before institutional investors would purchase loans. Also, large investors are searching for assets with relatively high yields in a low-interest-rate environment. Finally, some institutional loan owners have had success securitizing marketplace loans.17

Banks

Some banks are collaborating with the new marketplace lenders in a variety of ways. As mentioned earlier, indirect lenders use an issuing bank to originate loans for a fee, which the indirect lender buys within a few days. Although this business model is widely used and involved in issuing billions of dollars of loans, only a few specialized banks currently participate.

Small and large banks are involved in marketplace lending as purchasers of loans. According to reports, one marketplace lender finances almost 10% of its loans with small banks, and another reportedly has an agreement with a single bank that allows the bank to purchase up to 25% of the lender's loans. Typically, banks apply their own automated filters on loan characteristics to determine which loans they want to purchase. This arrangement allows banks to use the low-cost underwriting of marketplace lenders without having to create their own online platforms. Banks are able to acquire loans that they otherwise may not originate themselves because of high underwriting and servicing costs relative to the income generated by small loans. However, the borrowers in such arrangements often are not aware of a bank's involvement. Thus, a bank may not able to build customer relationships or offer additional products, as it would if it made the loan itself.18

Banks also enter into arrangements with marketplace lenders in ways that allow the banks to maintain closer relationships with the borrowers. In referral partnerships, a bank will refer customers—usually those who do not meet underwriting standards or are looking for a product the bank does not offer—to a marketplace lender. Often the bank collects a fee from the lender, but the interaction with the borrower may allow the bank to establish or maintain a business relationship.

White label or co-branded partnerships allow banks to be more closely associated with the provision of credit to a customer, while still taking advantage of the cost advantages of a marketplace lender. These partnerships are also an example of how marketplace-lending activities are increasingly being adopted by traditional lenders. In these partnerships, a bank sets underwriting standards, originates the loans, and holds the loan once issued.19 The marketplace lender sets up the online application platform and automation of the underwriting.20 In this case, the lending ceases to be marketplace lending in the sense that this report uses the term, as the marketplace lending company acts as a third-party vendor for a bank.

Potential Opportunities

Some industry observers assert that marketplace lending has inherent advantages over traditional lending, including the following:

- Cost structures may be lower.

- Underwriting may be more accurate.

- The application and underwriting processes may be faster, more convenient, and more aligned with certain customer preferences for financial-service delivery.

Proponents argue that these advantages will allow marketplace lending to continue to grow and transform the way individuals and small businesses acquire credit. Furthermore, proponents assert that the changes will provide an opportunity for improvements in financial and societal outcomes:

- Credit could become less expensive for individuals and small businesses.

- Credit could become more available, especially for traditionally underserved or unserved market segments, such as small businesses and people with thin credit histories.

- Returns for credit investors could be higher.

This section analyses those arguments.

Potential Industry Advantages

Marketplace lenders likely hold operating-cost advantages over banks, because online-only application processes, automated underwriting, and a lack of branch infrastructure keep labor and overhead costs low. One analysis estimates that loan processing and servicing costs as a percentage of loan amounts were 61% lower for marketplace lenders than traditional banks. Whether marketplace lenders could hold operating-cost advantages over other nonbank lenders is not clear, but it is possible if older nonbank lenders have more costly legacy systems.21

Some analysts question whether marketplace lenders have a total cost advantage over banks, because banks have lower funding and marketing costs. Early analyses find that marketplace lenders' total costs as a portion of loan amount are similar to the largest banks.22 However, it may be too early to make these comparisons. Marketplace lenders have only recently begun to build their business, whereas the largest banks have achieved economies of scale that reduce average costs. Marketplace lenders' costs per loan may decrease as these lenders become bigger and refine their business models and practices. For example, the technology-driven innovations used to process and service loans are likely scalable, meaning costs will not increase substantially as lending volumes do. Therefore, operating-cost advantages could grow as the industry does.23

Some marketplace lending proponents argue that the automated underwriting used by marketplace lenders may be more accurate than traditional underwriting processes.24 Traditional lenders use income, debt, and credit score information—such as FICO scores, a measure of past debt-repayment performance—to assess the likelihood that a borrower will repay the loan.25 Whereas traditional credit scores are largely based on a customer's repayment performance on past debt, marketplace lenders may analyze more factors.26 Each company uses different variables in its proprietary algorithm, but data used in some algorithms may include information such as utility bill payment history, monthly cash flow and expenses, government records, internet presence, and social-network activity. Whatever advantage marketplace lenders may have in this area is precarious, because established lenders can adopt similar technologies and practices.

Another potential advantage that the marketplace-lending industry holds over incumbent bank and nonbank lenders is its ability to better satisfy the preferences of and reduce time costs for potential borrowers. Consumers are increasingly comfortable using the internet and mobile devices for the delivery of financial services, and many may value the speed and convenience offered by marketplace lenders. Whereas traditional lenders have to adjust legacy systems and existing infrastructure to use these technologies, marketplace lenders may be able to design their processes to fit current customer needs. However, certain traditional lenders possibly could update their large existing infrastructures to meet their customers' preferences at less cost than start-up companies could build a new infrastructure and customer base.27

Potential Beneficial Outcomes

Although there are no official data to accurately measure the effects of marketplace lending on financial markets and the economy, it is possible that the advantages described above could result in desirable outcomes, such as lower rates for borrowers, better returns for investors, and increased credit availability for some borrowers without access to bank credit.

If the costs of originating and servicing loans and the costs of losses from nonperforming loans (due to more accurate underwriting) are lower, then these savings could be passed on to consumers in the form of lower interest rates and lower loan fees.28 In addition, lowering the cost of making loans and reducing losses on the loans improves the efficiency of financial intermediation—the matching of a borrower's need for funds to a saver's or an investor's available funds. If marketplace lenders as intermediators are able to charge less to cover their costs, that could result in higher returns for the investor as well as lower costs for the borrower.29

Accurate underwriting using a greater number of factors could also result in the extension of credit to creditworthy borrowers that otherwise would not have been approved. Small businesses and people with a lack of credit history—many of whom are low-income earners, minorities, or immigrants—are often cited as being at particular risk of being denied credit, even if they may be creditworthy. Marketplace lenders could overcome two potential causes for this lack of available credit. One potential challenge facing traditional lenders is that small loans generate little revenue relative to large ones, but underwriting and processing a small loan carries similar costs to underwriting and processing a large one.30 Thus, traditional lenders may find it difficult to make small lending profitable, whereas a marketplace lender with lower underwriting and processing costs could profitably make those loans.

Another challenge to traditional lenders is that assessing borrowers with a lack of credit history—which is vital to traditional credit assessments through credit scores—may involve too much uncertainty about the likelihood of repayment.31 For marketplace lenders, innovative use of a wider array of data could reduce the uncertainty of credit assessments compared with traditional underwriting.

These improved outcomes need not necessarily come from marketplace lenders alone. Better credit availability also could be realized if traditional banks and nonbank lenders adopted similar methods to reduce costs and expand data usage in underwriting.

Potential Risks

Some observers are concerned that a great deal of uncertainty surrounds the marketplace lending industry. Skeptics argue that the industry is creating risks for borrowers, investors, and the financial system. The sources of potential risk include the following:

- Underwriting accuracy and loan performance has not been tested by economic recession.

- Some marketplace lenders—including a number of the largest—generate revenue from origination fees but do not hold the resultant loans and are not subject to risk-retention rules, possibly creating an incentive to make excessively risky loans.

- Funding availability and demand for loans has been high during a period of economic expansion with low interest rates, but the ability to raise funds and attract borrowers in other economic conditions is unproven.

- Servicing of loans in the event of a failure of a marketplace lender could be disrupted.

These risks potentially threaten the borrowers of and investors in marketplace loans, marketplace lending companies themselves, and—if marketplace lending grows sufficiently in coming years—the financial system. The adverse outcomes could include the following:

- Loan delinquency and default rates could grow to an unexpectedly high rate, harming borrowers' future credit availability and inflicting large, unanticipated losses on investors.

- Credit determinations by marketplace lenders could disparately impact minorities and other protected groups.

- Loan demand or funding for marketplace loans could contract to the point that marketplace lenders fail, potentially stopping the flow of payments to loan investors.

- If the industry grows sufficiently large in the future, bad underwriting, large losses on marketplace loans, or marketplace lender failures could create systemic stress.

This section analyses those arguments.

Potential Sources of Risk

The accuracy of the data-driven algorithms used by marketplace lenders is hard to determine without a long history of data for these types of loans to compare their performance with that of traditionally originated loans. Importantly, marketplace lending has only grown into a substantial financial activity during the current expansion, when loans of almost all types are expected to perform well. All new lending companies and underwriting methods remain untested for a period, but the rapid growth of marketplace lending has occurred during relatively favorable economic conditions, which could create a concentration of underwriting risk. A more revealing test will come during the next economic downturn, when delinquency and default rates across assets can be expected to rise.32

Some observers are concerned that certain marketplace-lending companies could be threatened by changing economic conditions. Marketplace lenders need to continually attract both borrowers demanding loans and investors willing to fund loans. Lenders have been able to do this successfully in recent years, but exclusively in a time of economic expansion and low interest rates. During expansion, credit demand is relatively high, which results in more loans to originate. Investors have been willing to fund relatively high-interest-rate loans, potentially because investors are seeking out higher rates of return in a low-rate environment. When these conditions change, marketplace lending may not remain viable.

Banks and some nonbank lenders, by contrast, may be better able to withstand a change in these conditions. Unlike many indirect marketplace lenders, banks and nonbank companies that hold assets on their balance sheets will earn interest on those assets and their portfolios of loans, and other assets may be more diversified than those of direct marketplace lenders. Additionally, deposits give banks a source of stable funding.33

Some finance companies—nonbank lenders that hold consumer and business loans and leases on their balance sheets—share important characteristics with marketplace lenders; they make loans and rely on market funding rather than deposits. The experience of finance companies during the financial crisis illustrates the potential risk marketplace lenders face. When market funding contracted, many finance companies failed or were bought by banks.34

Certain aspects of some marketplace-lender business models could create incentives to weaken underwriting and originate bad loans. Many marketplace lenders originate a loan for a fee but do not hold the loan on their balance sheets. If the borrower defaults, the loan investor bears the loss. Thus, a marketplace lender could make bad loans and collect fees but not suffer the ensuing losses, potentially creating the incentive to make bad loans. This activity is also common among traditional bank and nonbank lenders, but these lenders are subject to risk-retention rules—which will be discussed in more detail in the "Regulatory Issues" section—designed to mitigate this risk. However, marketplace lenders are generally not subject to these rules, provided they do not pool numerous loans together into a single security. Such originate-to-sell models concern some observers.35

The potential for marketplace-lender failure creates uncertainty surrounding loan servicing—a process that includes taking payments from borrowers and delivering these payments to the investors. After marketplace lenders sell loans, they often still perform loan servicing for a fee. Typically, when a mortgage servicer fails the servicing rights are quickly reassigned. Whether a marketplace-lending company would be able to continue to process these payments or transfer the mortgage servicing to another company in the event of a failure is unclear. This risk exists for any mortgage servicer, but the risk of disruption may be greater at marketplace lenders that are relatively inexperienced.36

Potential Adverse Outcomes

Borrowers could potentially be harmed in several ways as a result of these risks. Faulty underwriting could result in borrowers being rated as being a higher credit risk than they actually are and having to pay unnecessarily high interest rates. Alternatively, if the underwriting is too lenient, loans could be made to borrowers that lack the ability to repay the loans. Defaulting would then restrict these borrowers' future access to and prices paid for credit.

Another possibility is that the algorithms and data used in automated underwriting could make credit assessments that are correlated to borrower characteristics protected by fair-lending laws, such as race or gender. Whether this correlation were intentional or unintentional, it could result in borrowers from a protected group being disproportionately denied credit or charged higher interest rates compared with other groups.37

Investors in marketplace loans also face risks related to the accuracy of credit assessment. Proprietary underwriting systems' lack of a track record through all types of economic and credit conditions introduces uncertainty regarding the future performance of marketplace loans. If the underwriting proves to be inaccurate, investors could be buying inappropriately high-risk loans and eventually could suffer unexpected losses.

The failure of marketplace lending firms is not problematic per se. Uncompetitive or unsustainable business models failing and equity holders suffering losses after taking informed risks is a central dynamic to a market economy. However, widespread failure of marketplace lenders—especially if these lenders grow to the point that they provide a substantial amount of credit to consumers and small businesses—could lead to a sharp contraction in the availability of credit to the economy. Also, because marketplace lenders often service loans they make, marketplace lenders' failure could disrupt payment to investors from performing loans.38

Another potential future issue is systemic risk from marketplace lenders. Currently, marketplace lending is likely too small relative to total credit outstanding to cause stress across the financial system if loan defaults were to rise or marketplace lenders were to fail. However, the industry is growing rapidly, and its investors include individual savers and large institutional investors. Banks buy marketplace loans and enter into a variety of agreements and arrangements with marketplace lenders. If the size and interconnectedness of marketplace lending continues to grow, the industry risks could threaten systemic stability in coming years.39

Regulation

Marketplace lending is subject to federal and state regulations and requirements. The rules are numerous but will be generally described here in three groups:

- Securities registration and disclosure.

- Consumer protection and fair-lending compliance.

- State-level regulatory requirements.

Although marketplace lending is subject to these rules and regulations, the existing regulatory system was designed prior to the advent of online marketplace lending. As a result, there is some uncertainty related to how regulation should be applied and how effective it can be. Some issues include the following:

- Potentially uncertain, inconsistent, or unnecessarily burdensome application of state regulation.

- Potential lack of supervisory oversight.

- Lack of risk-retention requirements.

Existing Regulatory Framework

Making loans and selling whole loans, loan notes, or equity to investors are well-established financial activities, and participating firms are subject to many existing regulations and requirements involving both federal and state regulatory agencies.40 Examples of federal regulations are listed in the Appendix. This section focuses on certain issues concerning securities issuance, consumer protection and fair lending, and regulations at the state level.

Federal Securities Regulation

The objective of securities law is to ensure that investors have enough information to make informed judgments and to prevent investors from being defrauded. The Securities Act of 1933 (P.L. 73-22) generally requires issuers that make a public offering of securities41—which would include marketplace lenders raising funding by selling loan notes or issuing equity to the general public42—to register securities with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).43 The act also requires that issuers of securities provide investors with a public disclosure containing detailed information about the issuer and the relevant securities, including descriptions of the issuing company and securities, financial statements, and a discussion of risk factors. Companies issuing registered securities also must fulfill ongoing reporting requirements related to their financial condition under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (P.L. 73-291).44

Certain marketplace lenders may be able to forego registration of their securities with the SEC if they meet criteria that qualify them for an exemption from registration.45 Some of these exemptions restrict funding sources and marketplace lender size. For example, a marketplace lender that offered securities online could be exempt from SEC registration under Regulation A46 or Regulation D.47

Companies can also qualify for reduced reporting requirements as an "emerging growth company" if they meet certain criteria, including annual revenues of less than $1.07 billion.48

Regardless of whether the securities are registered or unregistered, marketplace lenders would be liable for investor losses if the offering materials they provided contained materially false information or omitted important information. Borrower-provided information could potentially create such a liability. Marketplace lenders verify much, but not all, of the information borrowers include in applications, some of which could be incorrect. Marketplace lenders have addressed the problem by stating in their offering materials what borrower information is unverified and specifying that investors assume the risk that this information is unverified.49

Securities issued by marketplace lenders backed by a single loan generally have not been treated as asset-backed securities (ABS) subject to the risk-retention rule by regulators. The purpose of this regulation is to incentivize prudent lending. ABS are defined as securities backed by a pool of assets. Most marketplace lenders issue notes backed by a single asset, an individual loan.50 This distinction allows marketplace lenders to avoid certain reporting requirements and risk-retention rules—prescribed by The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-203)—that require ABS issuers to retain a stake in the assets underlying an issuance.51

Federal Consumer Protection Regulation

When marketplace lenders make loans to consumers, the lenders are subject to consumer-protection laws. The Truth in Lending Act (P.L. 90-321) requires that lenders provide consumers with standardized, easy-to-understand information about the terms of the loan.52 The Equal Credit Opportunity Act (P.L. 94-239) prohibits lenders in a credit transaction from considering a borrower's race, color, sex, age, religion, national origin, marital status, or whether the borrower receives income from public assistance.53 Also, the method used to determine creditworthiness generally must not have a disparate impact on those groups based on any of these characteristics.54 The Dodd-Frank Act prohibits unfair, deceptive, and abusive acts and practices in consumer lending,55 and the Federal Trade Commission Act (P.L. 75-447) prohibits unfair or deceptive acts and practices in or affecting commerce, including lending.56 Consumers are also protected by laws related to debt collection, privacy, and credit-reporting practices, all of which may apply to marketplace lenders when their activities fall within the scope of these laws.57 Additional federal laws and regulations apply, but an exhaustive examination is beyond the scope of this report.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) are two important agencies involved in regulating marketplace lending. The CFPB has the authority to enforce federal consumer-protection laws, and nonbank lenders—including marketplace lenders—are generally subject to this enforcement authority. The CFPB also has rulemaking authority over consumer lending, including for rulemaking that prohibits unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts and practices. The FTC has enforcement authority of certain consumer-protection statutes. The FTC also has regulations in place prohibiting certain abusive terms in credit contracts.58

In addition, under certain circumstances, marketplace lenders may be subject to consumer compliance requirements and supervision by federal bank regulators—the Federal Reserve, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation—an issue that will be covered in more detail in the "Federal Supervisory Authority" section.59

|

Troubles at Lending Club: Examples of Federal Regulatory Actions On May 9, 2016, Lending Club—reportedly the world's largest marketplace lender—publicly announced the results of an internal review conducted by an independent subcommittee of the company's board of directors related to the improper sale of loans.60 The review revealed, among other things, that (1) in March and April 2016, Lending Club sold a total of $22.3 million worth of loans to an institutional investor with characteristics that did not conform to that investor's requirements and (2) in late December 2009, the chief executive officer (CEO) of Lending Club and three of his family members took out 32 loans totaling $722,800 through the Lending Club platform to boost reported loan volumes. Lending Club repurchased the nonconforming loans at par from the investor, and the CEO resigned shortly before the public announcement of the review findings.61 Following the announcement, Lending Club received a grand jury subpoena from the Department of Justice (DOJ) and formal requests for information from the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) as the agencies began investigations.62 The DOJ and SEC investigations were still ongoing as of June 2018,63 and in April 2018 the FTC filed a complaint in federal court, charging Lending Club with, among other things, deceptive practices involving hidden fees and falsely indicating to applicants that investors had backed their loans.64 Although the outcomes of the investigations and legal action are not yet known, they nevertheless serve as an illustration that marketplace lenders are subject to the legal and regulatory authorities of federal regulatory agencies. |

State Laws

In addition to federal securities and lending laws, many marketplace lenders are subject to related state-level laws in states in which they operate. The issuer of securities sometimes has to register the securities with a state securities commission and may have to renew that registration periodically. The state commission may have the authority to deny registration of any security it judges to be unsuitable for sale.65 Individual states also have laws prohibiting unfair or deceptive trade practices. Each state may require a marketplace lender to get one or more licenses to operate as a lender, broker, or debt-collection agency, depending on the state's requirements. Finally, certain states have laws that limit the amount of interest and fees a lender can charge for certain loans.66

State laws and regulations—and the related obligations and costs they impose on certain marketplace lenders—raise interrelated policy questions related to what degree marketplace lenders should be subject to federal- or state-level laws and regulations. These questions are covered in more detail in the "Federal and State Regulation: Debate and Uncertainty" subsection in this report.

Regulatory Issues

Policymakers developed much of the existing regulatory framework before marketplace lending emerged, and observers have raised questions about the effectiveness and efficiency of current regulation as it relates to this industry. Proponents of marketplace lending highlight certain issues that they argue are unnecessarily hindering the growth of a beneficial source of credit. They assert that certain court decisions have created uncertainty regarding how existing laws and regulations will be applied to marketplace lenders and the loans they make.67 In addition, they argue that complying with 50 different sets of state laws and regulations is unnecessarily burdensome.68

By contrast, some observers have expressed concern over whether current regulations appropriately address the risks posed by marketplace lending. They question whether regulators have the necessary authorities—such as supervisory authority—to adequately monitor the industry and whether existing regulation appropriately mitigates risks associated with the "originate-to-sell" business model used by many marketplace lenders.69 A related concern is that certain marketplace lenders may be practicing regulatory arbitrage—meaning they are designing their business models and activities specifically to circumvent certain regulations.70 If this were the case, it would mean that although the risks presented by marketplace lenders are not fundamentally different from those presented by other, more established lenders, they nevertheless are subject to regulation that is more lenient.

This section will cover issues related to the following:

- Uncertainties over the degree to which federal or state laws and regulations apply to particular marketplace lenders and certain proposed solutions to create clarity;

- Supervisory authorities in regard to marketplace lenders; and

- Originate-to-sell models used by many marketplace lenders.

Federal and State Regulation: Debate and Uncertainty

In many cases, marketplace lenders are required to obtain applicable state licenses and are subject to state regulatory regimes regarding lending and securitization in each state in which they operate. Certain proponents of the industry have argued that in certain cases, state-by-state regulation is unnecessarily onerous, is inefficient, and hinders the growth of a potentially beneficial industry. They contend that federal bank regulations should apply to certain marketplace lending and preempt state law.71 Other observers, including customer advocacy groups and state regulators, have argued that state-level regulations provide important oversight and consumer protections that marketplace lenders should not be allowed to circumvent.72

In addition to debates over whether federal or state rules should apply, recent court rulings have created uncertainty regarding the circumstances in which federal or state law will apply. Policymakers have made certain proposals intended to provide clarity on these issues. For example, bills that would provide clarity on the legal issues in question have been introduced in the 115th Congress, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) has announced that it will accept applications for national bank charters from certain fintech companies, such as marketplace lenders. These proposals generally seek to ensure that federal law will preempt certain state regulations of marketplace lenders.73 As a result, observers that view state regulations as unduly burdensome typically support these proposals,74 and those that view state regulations as necessary and appropriate oppose them.75

"True Lender" and "Valid When Made"76

State usury laws and other state-level requirements are likely a factor in why some marketplace lenders use an indirect lending business model.77 Recall that in this model, a Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC)-insured bank originates the loans and the marketplace lender sells a note backed by the loan to investors. The indirect lending arrangement may allow indirect marketplace lenders to avoid being subject to individual state laws. Generally, federal law provides that FDIC-insured banks are subject to the usury laws of only the state in which they are incorporated, even when lending to borrowers in other states with stricter usury laws.78 Federal law accordingly preempts the application of state usury laws to FDIC-insured banks by allowing FDIC-insured banks to "export" the maximum interest rates of their "home" states when lending to borrowers in other states.79

Recently, certain judicial decisions have created uncertainty over whether states may enforce their usury laws against nonbanks that purchase loans from FDIC-insured banks. Specifically, these decisions have generated uncertainty regarding the circumstances in which nonbanks, which do not have the right to "export" the maximum interest rates of their "home" states when they originate loans to borrowers in other states, acquire that right with respect to loans they purchase from FDIC-insured banks.80 A detailed legal analysis of such cases is beyond the scope of this report. What bears mentioning here is that until recently, nonbanks that purchased loans from FDIC-insured banks generally have assumed that they are entitled to federal preemption of state usury laws with respect to those loans under the "valid when made" principle.81 According to the "valid when made" principle, which has been endorsed by some courts in certain contexts,82 a loan that is nonusurious (and thus valid) when originated remains nonusurious irrespective of the identity of its subsequent purchasers. However, several recent judicial decisions have cast doubt on whether the "valid when made" principle allows nonbanks to benefit from federal preemption.

A number of courts have held that arrangements pursuant to which nonbanks engage in significant "lender-like" activities in connection with loans, such as soliciting borrowers and making credit decisions, and direct partner banks to originate the loans (so-called "rent-a-charter" schemes), do not benefit from federal preemption of state usury laws. These courts have concluded that based upon the economic realities of the relevant transactions, the nonbanks are the "true lenders" and are not entitled to federal preemption.83

Moreover, in 2015, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit held that federal law did not preempt state-law usury claims brought against a nonbank debt collector that had purchased debt from a national bank even in the absence of such a "true lender" claim.84 The court arrived at this conclusion despite the fact that the plaintiff had not alleged that the debt collector was the "true lender" because the court reasoned that the application of state usury law to the debt collector would not significantly interfere with the national bank's ability to exercise its federally conferred right to "export" the maximum interest rate of its "home" state.85

These decisions present some marketplace lenders with legal uncertainty. Currently, indirect marketplace lenders generally rely on an understanding that the banks they partner with are the "true lenders," and that they benefit from federal preemption with respect to the loans they purchase from these banks.86 If this is not actually the case, marketplace lenders may have to adjust their business models to ensure that they comply with the usury laws of all of the states in which they operate.

A number of bills in the 115th Congress are intended to address these uncertainties and clarify issues related to third-party loan arrangements. H.R. 4439, which was referred to the House Committee on Financial Services in November 2017, would establish guidelines for when a bank is a "true lender." Section 581 of H.R. 10 and H.R. 3299 (which passed the House in June 2017 and February 2018, respectively), and S. 1642 (which was referred to the Senate Banking Committee in July 2017) would codify the "valid when made" principle. Proponents argue that these bills would resolve the uncertainty involving "true lender" questions and the "valid when made" doctrine, and thus allow increased credit availability through third-party relationships.87 Opponents argue such bills would inappropriately undermine important state-level consumer protections.88

Special Purpose National Bank Charter89

One possible avenue to resolve some uncertainty facing certain marketplace lenders (and other financial technology firms performing bank-like activities) would be to allow them to apply for and, provided they meet all necessary requirements, to grant them national bank charters.90 In this way, these companies would be explicitly subject to all laws and regulations applicable to national banks, including those that preempt state law. In December 2016, then-Comptroller of the Currency Thomas Curry announced that the OCC would examine whether certain financial technology companies would be eligible to receive a special purpose national bank charter,91 and the OCC released a whitepaper examining the issue and calling for public comments.92 On July 31, 2018, the OCC issued a policy statement announcing that it would consider "applications for special purpose bank charters from financial technology (fintech) companies that are engaged in the business of banking but do not take deposits."93

Until the OCC actually grants such charters and marketplace lenders operate under the national bank regime for some amount of time, determining the benefits and costs of these fintech charters will be speculative to a certain degree. Importantly, marketplace lenders are not required to obtain an OCC charter, but rather they have the option to do so. How many will elect to apply to enter the national bank regime and be approved by the OCC is still an open question.94

In addition, the OCC stated that fintech firms granted the charter "will be subject to the same high standards of safety and soundness and fairness that all federally chartered banks must meet," and also that the OCC "may need to account for differences in business models and activities, risks, and the inapplicability of certain laws resulting from the uninsured status of the bank."95 How the specific parameters of the new charters strike that balance in practice may significantly affect what the outcomes of issuing fintech charters will be. If the OCC is too accommodative of marketplace lenders, they could gain the advantages of a national bank charter without being subject to sufficient prudential safeguards and consumer protections. Not only could this generate inappropriately large risks, it could give marketplace lenders an advantage over traditional banks. If the OCC is too stringent, then there may be no incentive for marketplace lenders to apply for a charter, making it an ineffective solution to the challenges the charter is aimed at addressing.

Finally, the OCC's assertion that it has the authority to grant such charters may be challenged. Shortly after the initial 2016 announcements that the OCC was examining the possibility of granting the charters, the Conference of State Bank Supervisors and the New York State Department of Financial Services sued the OCC to prevent it from issuing the charters on the grounds that it lacked the authority to do so.96 However, a federal district court dismissed the case after concluding that because the OCC had not yet issued charters to nonbanks, the plaintiffs (1) lacked standing to challenge the OCC's purported decision to move forward with chartering nonbanks, and (2) had alleged claims that were not ripe for adjudication.97 Since the dismissal, state regulators have expressed their intent to file new legal challenges if the fintech charters are granted.98 Given the OCC's July 2018 announcement, it appears state regulators may soon have the opportunity to do so.

Notwithstanding these uncertainties, observers have made assessments on the advisability or inadvisability of making a national bank charter available to marketplace lenders. Proponents of the idea generally view the charter as a mechanism for freeing companies from what they assert is the unnecessarily onerous regulatory burden of being subject to numerous state regulatory regimes. They further argue that this would be achieved without overly relaxing regulations, as the companies would become subject to the OCC's national bank regulatory regime and its rulemaking, supervisory, and enforcement authorities.99 Opponents generally assert both that the OCC does not have the authority to charter these types of companies, and that doing so would inappropriately allow marketplace lenders to circumvent important state-level consumer protections.100

Federal Supervisory Authority

Marketplace lenders—like many nonbank lenders—are generally not subject to the same federal supervisory oversight as banks.101 Although many laws and regulations apply to marketplace lenders, federal regulatory oversight and checking for compliance is generally less active ex ante than it is at banks, where examiners periodically check if the institution is complying with regulations.

However, in the event that marketplace lenders apply for and are granted special purpose national bank charters as proposed by the OCC, they would become directly subject to the OCC's supervisory authority.102 In addition, as third-party vendors, indirect lenders that partner with banks that originate loans are subject to supervision if the bank's regulator chooses to examine them. Even if the regulator chooses not to directly supervise an indirect marketplace lender, its supervisory authorities could indirectly set parameters on marketplace lender behavior. The partner bank is "ultimately responsible for managing activities conducted through third-party relationships" in the eyes of the regulator,103 and so the bank has incentive to monitor and demand certain standards of partners in business relationships.

Some observers, though, are concerned that as currently constructed, this situation creates opportunities for marketplace lenders to harm borrowers.104 For example, direct lenders are not subject to federal oversight, because their lending activities do not involve a partner bank. If policymakers determine that greater federal oversight is necessary, one possible avenue would be to subject them to CFPB supervision. The CFPB has certain authorities to supervise nonbanks under certain circumstances. The CFPB may supervise nonbanks that originate, broker, or service mortgage loans; "larger participants" (as defined through CFPB rulemaking) in markets for consumer financial products or services; payday lenders; private education lenders; and entities which the CFPB has reasonable cause to determine pose risks to consumers with regard to the offering or provision of consumer financial products or services.105 Thus, the CFPB may be able to place certain marketplace lenders that are large or have questionable business practices under its supervision, though it has not yet done so. If Congress determined marketplace lenders should have closer federal supervision, it could direct the CFPB or another agency to do so through legislation.

"Originate-to-Sell" and the Risk-Retention Rule

When marketplace lenders sell a single loan or pieces of a single loan, they generally have not been required to adhere to risk-retention rules, which apply to issuers that pool many loans together into a single security, a common practice at banks and nonbank lenders. Risk-retention rules were adopted after the financial crisis in an effort to prevent imprudent lending by institutions originating loans with the intent to securitize them. The rules generally require an institution that securitizes loans into a pooled security to hold a portion (usually 5%) of the underlying assets on its balance sheet. Potential loss from loans defaulting is an incentive for the originator to maintain careful underwriting practices and not make excessively risky loans. Some observers assert that marketplace lenders face the same incentive to weaken underwriting that issuers of pooled securities do and should be subject to the rule. Others assert that risk retention is unnecessary because, among other reasons, the simplicity of a single loan—unlike a security backed by numerous loans and featuring complex structures regarding returns to investors—makes it easier for an investor to understand the risks she is taking.106

Potential Future Developments

The marketplace-lending industry is young and involves a degree of uncertainty. Several developments could reveal more about the future of the industry, including the following:

- Traditional lender response to new innovations and companies.

- Marketplace lending performance during and after a recession.

- Resolution of outstanding regulatory issues.

Traditional Lender Response

Incumbent lenders may respond to the emergence of marketplace lending in several ways, including no longer competing for small, unsecured loans; adopting the technology and practices of marketplace lenders; and entering into cooperative relationships with marketplace lenders. How the market develops and to what extent marketplace lending becomes part of traditional bank and nonbank lending practices may affect how the regulatory system will respond.

Some banks may choose not to compete directly with marketplace lenders. Small loans have low profit margins compared to large ones.107 Banks may decide that their business models, which require branch infrastructure and higher regulatory costs, should not include making small, unsecured loans. By not competing in this market, banks would avoid the costs of setting up their own online, automated systems or changing their application and underwriting systems, while losing only unprofitable customers. However, banks would risk later losing market share of more profitable segments if marketplace lending continues to grow and branch out into more profitable market segments.

Alternatively, banks could choose to compete directly with the emergent companies. One option for banks would be to independently start their own online, automated platforms and use more data in underwriting. All loans or certain loans that align with a bank's own underwriting standards could be held on the balance sheet, and capabilities to match loans with investors could also be developed. By developing their own platforms, banks could bring the efficiencies of marketplace lenders into their own business models. Alternatively, banks could purchase existing online marketplace lenders and make them part of the bank's organization. The risk associated with developing a platform or purchasing an existing one is that it would require a potentially large investment in an area outside bank expertise.108 Another, more concerning possibility is that in competition for market share, banks may weaken underwriting to generate more originations, potentially leading to loan losses.109

Another option that banks are commonly pursuing is to enter into a collaborative relationship with marketplace lenders, as discussed in the "Participants" section. For most banks, this approach means investing in loans originated by online lenders or contracting with marketplace lenders to create an online, automated platform for the bank. These arrangements could allow banks to share in some of the benefits of marketplace lending and to commit to smaller additional costs.110

Performance in Recession

Many uncertainties about marketplace lending will likely be clarified after the industry has been active during an entire economic cycle with a recession. Loan demand and funding availability likely will decline during adverse economic conditions, and whether marketplace lenders fail will reveal more about the sustainability of the business models. In addition, potential investors and market analysts will be able to more meaningfully compare delinquency and default rates of marketplace loans relative to other lenders after a complete credit cycle, and the industry's relative performance may affect funding availability either positively or negatively.111

Regulatory Developments

As the marketplace lending industry develops, industry participants and policymakers will likely closely observe how laws and regulations are applied to marketplace lenders and what effect those applications have on the industry's growth and development. Based on those observations, policymakers likely will have to make determinations on where the existing framework appropriately regulates the industry—in such instances no action will necessarily be taken—and where regulation needs to be changed. For example, as marketplace lenders apply for and are granted special purpose charters, it will create clarity about the characteristics and parameters of that regime. Policymakers could determine a federal agency or agencies should take a more active role in the direct oversight of marketplace lenders, which may require a statutory change depending on the current supervisory authority of regulatory agencies. If policymakers determine the originate-to-sell business models used by marketplace lenders present sufficiently similar risks as those used by traditional loan securitizers, risk-retention rules could be applied to the marketplace lenders. Other uncertainties related to "true lender" and "valid when made" questions may be resolved judicially or through legislation.112

Conclusion

Marketplace lending is a rapidly growing and evolving industry involving new firms and technologies, individual borrowers and savers, institutional investors, and banks. The industry's lack of track record and its interconnectedness result in many areas of uncertainty. Opportunities for benefits exist for borrowers (including underserved borrowers), investors, and the financial system, but these opportunities come with potential risks. The current regulatory system aims to balance benefits and risks, but it was developed before marketplace lending became prevalent. As a result, it is not clear how effectively the existing system will regulate the marketplace-lending industry. As the industry matures and if regulatory issues are resolved, the effects of marketplace lending for the financial system and the economy will become clearer.

Appendix. Examples of Laws and Regulations

|

Law |

Examples of Requirements or Provisions |

Relevant Federal Agencies |

|

Bank Service Company Act |

Provides federal banking agencies with the authority to regulate and examine certain third-party service providers for banks. |

FRB, OCC, FDIC, NCUA |

|

Electronic Fund Transfer Act (P.L. 95-630)—Regulation E |

Stipulates that terms and conditions of electronic transfers to and from customer accounts must be disclosed and consumer liability for unauthorized transfers is limited. |

OCC, FRB, FDIC, NCUA, FTC, CFPB |

|

Equal Credit Opportunity Act (P.L. 94-239)—Regulation B |

Prohibits lenders from discriminating against applicants on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, sex or marital status, age, or whether public assistance is a source of income. |

CFPB, FRB, OCC, FDIC, NCUA,FTC, DOJ |

|

Fair Credit Reporting Act |

Imposes disclosure requirements on lenders that deny an application based on information in a credit report. Requires that information reported to credit bureaus is accurate, that credit reports are obtained only for a permissible purpose, and that lenders have an identity-theft-prevention program. |

FTC, CFPB, FRB, OCC, NCUA, FDIC |

|

Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (P.L. 95-109)—Regulation F |

Provides guidelines and limitation on conduct of consumer debt collectors. Prohibits false and misleading representations, harassing or abusive conduct, and unfair practices. |

FTC, CFPB, OCC, FRB, FDIC, NCUA |

|

Section 1036 of the Dodd-Frank Act (P.L. 111-203) |

Prohibits unfair, deceptive, or abusive business acts or practices. |

CFPB |

|

Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act (P.L. 75-447) |

Prohibits unfair or deceptive business acts or practices. |

FTC, FRB, FDIC, OCC, NCUA |

|

Securities Act of 1933 |

Requires securities issuers engaged in a public offering to register the securities with the SEC, unless the securities are exempt. |

SEC |

|

Securities Exchange Act of 1934 |

Generally requires securitizers or sponsors of asset-backed securities (ABS) to retain an economic interest of at least 5% of the credit risk of the assets collateralizing the ABS. |

FDIC, FRB, OCC, SEC, FHFA, HUD |

|

Title V of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Financial Modernization Act (P.L. 106-102)—Regulation P |

Limits when financial institutions may disclose a consumer's nonpublic personal information and requires financial institutions to notify customers about their information-sharing practices and about the customer's right to opt out. |

FTC, CFPB, FRB, OCC, NCUA, FDIC |

|

Truth in Lending Act |

Requires lenders to provide understandable disclosures about certain terms and conditions of their transaction with the borrower and gives borrowers certain rights to updated disclosures. Regulates the advertising of lenders. |

CFPB, FRB, OCC, NCUA, FDIC, FTC |

Source: Peter Manbeck and Marc Franson, The Regulation of Marketplace Lending: A Summary of the Principle Issues (2016 Update), American Bankers Association White Paper, April 2016, pp. 38-39.

Notes: This is not an exhaustive list of all regulations related to marketplace lending but rather an illustrative list of examples.

CFPB = Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

DOJ = Department of Justice

FDIC = Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation

FHFA = Federal Housing Finance Agency

FRB = Federal Reserve Board

FTC = Federal Trade Commission

HUD = Department of Housing and Urban Development

NCUA = National Credit Union Administration

OCC = Office of the Comptroller of the Currency

SEC = Securities and Exchange Commission

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge Jay B. Sykes, CRS Legislative Attorney, for contributing the legal analysis and for his valuable comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

| 1. |

Two notes on terminology: The term peer-to-peer lending was widely used during the early development of the industry. Marketplace lending includes peer-to-peer lending but also refers to a wider range of lending activity. Peer-to-peer lending involves selling loans to individual people and used to be a very prevalent business model in the industry. However, large institutional investors and hedge funds play an increasingly prominent role in funding marketplace loans, making the term peer misleading. Fintech is a broad and evolving term that generally refers to issues involving new, innovative technologies being used to change the way financial services are provided or the way the financial system operates. Marketplace lending is one example of a business practice that can be classified as Fintech. |

| 2. |

Freddie Mac, Office of the Chief Economist, Marketplace Lending: The Final Frontier? December 22, 2015. |

| 3. |

Loan securitization refers to an arrangement in which the holder of loans creates and sells a security to an investor which entitles that investor to receive payments dependent on the repayment of the underlying loan or loans. Typically, marketplace lenders that engage in securitization sell securities backed by a single loan. Typically, other types of lenders that engage in securitization sell securities backed by a pool of hundreds or thousands of loans. |

| 4. |

Collateral is an asset the borrower pledges to the lender that the lender can take possession of if the borrower defaults on the loan. For example, a mortgage is secured by a house. This allows the lender to recoup some value on a defaulted secured loan. For this reason, all else being equal, an unsecured loan is riskier than a secured loan. |

| 5. |

U.S. Department of the Treasury, Opportunities and Challenges in Online Marketplace Lending, May 10, 2016, pp. 10-15, at https://www.treasury.gov/connect/blog/Documents/Opportunities_and_Challenges_in_Online_Marketplace_Lending_white_paper.pdf. |

| 6. |

Ryan Nash and Eric Beardsley, "Future of Finance Part 1: The Rise of the New Shadow Bank," Goldman Sachs Equity Research, March 15, 2015, pp. 12-15, 23-26. |

| 7. |

Some marketplace lenders use issuing banks at least in part for regulatory reasons. By making a bank the originator of the loans, the marketplace lender may be able shift compliance of certain regulations to the bank. These issues are discussed in more detail in the "Regulation" section. |

| 8. |

U.S. Department of the Treasury, Opportunities and Challenges in Online Marketplace Lending, May 10, 2016, pp. 5-8, at https://www.treasury.gov/connect/blog/Documents/Opportunities_and_Challenges_in_Online_Marketplace_Lending_white_paper.pdf. |

| 9. |

Data from Statistica, available at https://www.statista.com/outlook/338/109/marketplace-lending—personal-/united-states#market-revenue, accessed on June 14, 2018. |

| 10. |

Federal Reserve, "Financial Accounts of the United States" (formerly Flow of Funds), Fourth Quarter 2017, Table L.222, line 1, and Table L.104, lines 18 and 19 (mortgages excluded), at https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/. |

| 11. |

Neil Tomlinson et al., "Marketplace Lending: A Temporary Phenomenon?" Deloitte Insights, May 2016, p. 5. |

| 12. |

U.S. Department of the Treasury, "Opportunities and Challenges in Online Marketplace Lending," May 10, 2016, pp. 10-15, at https://www.treasury.gov/connect/blog/Documents/Opportunities_and_Challenges_in_Online_Marketplace_Lending_white_paper.pdf. |

| 13. |

Ryan Nash and Eric Beardsley, "Future of Finance Part 1: The Rise of the New Shadow Bank," Goldman Sachs Equity Research, March 15, 2015, pp. 12-15, 23-26. |

| 14. |

"Marketplace Lending Industry Compendium," Lending Robot (blog), July 21, 2016, at http://blog.lendingrobot.com/industry/marketplace-lending-industry-compendium/. |

| 15. |

Lending Club, 2017 Annual 10-K filing, February 22, 2018, p.49, at https://ir.lendingclub.com/Cache/392292654.pdf?IID=4213397&FID=392292654&O=3&OSID=9. |

| 16. |

OnDeck, 2017 Annual 10-K filing, March 2, 2018, p.6, at http://d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net/CIK-0001420811/af7bf87c-defa-4abf-a2c4-5f3c3c0812cc.pdf. |

| 17. |

Smittipon Srethapramote et al., "Global Marketplace Lending: Disruptive Innovation in Financials," Morgan Stanly Blue Paper, May 19, 2015, pp. 9-10. |

| 18. |

PriceWaterhouseCoopers, "Peer Pressure: How Peer-to-Peer Lending Platforms Are Transforming the Consumer Lending Industry," February 2015, pp. 5-6. |

| 19. |

The bank may at a later time sell or securitize the loan, as the bank would any other loan it originates and holds. |

| 20. |

U.S. Department of the Treasury, Opportunities and Challenges in Online Marketplace Lending, May 10, 2016, pp. 15-17, at https://www.treasury.gov/connect/blog/Documents/Opportunities_and_Challenges_in_Online_Marketplace_Lending_white_paper.pdf. |

| 21. |

Neil Tomlinson et al., "Marketplace Lending: A Temporary Phenomenon?" Deloitte Insights, May 2016, p. 13. |

| 22. |

Comparisons of funding costs between the industries are challenging, because the true cost of raising funds and attracting customers is difficult to compare across the industries. Banks offer a wider range of financial services than marketplace lenders and have different costs and sources of funding. Banks pay low interest rates on deposits—one of their main sources of funding—to fund loans, but banks also incur other costs to attract funding and provide other services besides lending. Deposits are attractive to many savers because they are guaranteed by government deposit insurance. This insurance requires banks to take on regulatory costs of complying with bank safety and soundness regulation to obtain that insurance. Banks have costs associated with maintaining payment and processing systems and branch networks that are used in part to attract and retain depositors. Marketplace lenders avoid much of these costs and instead offer higher rates of return for investor funds and spend more on marketing to attract customers. |

| 23. |

Ryan Nash and Eric Beardsley, "Future of Finance Part 1: The Rise of the New Shadow Bank," Goldman Sachs Equity Research, March 15, 2015, p. 16. |

| 24. |