Capital Markets: Asset Management and Related Policy Issues

The asset management industry is large and complex. Asset management companies—also known as investment management companies, or asset managers—are companies that manage money for a fee with the goal of growing it for those who invest with them. The most well-known product these companies create are investment funds. Many types of investment funds exist, including mutual funds, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), hedge funds, private equity, and venture capital. Their business practices and the types of regulatory requirements to which they are subject are far from standardized. Investment funds differ by, among other things, asset risk profile, investor access, portfolio company operations, and the ease of buying or selling their shares. In addition to investment funds, the asset management industry also consists of entities that connect funds to investors and other services, such as investment advice providers and custodians.

Asset managers collectively manage trillions in assets, including investment savings, of nearly half of all U.S. households. The industry has experienced periods of high growth largely attributable to retail investors’ increased reliance on asset managers to invest their money for them rather than investing their own money themselves.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is the primary regulator overseeing the asset management industry. The industry is governed by a somewhat fragmented regulatory regime stemming from several different statutes. Most of the regulatory framework was created in the 1930s and 1940s, but the business practices and trends affecting the industry are evolving. Examples of this evolution include (1) the rapid growth of the industry; (2) the increasing dependency of American businesses on capital market financing; (3) the shift from active to passive investment style; and (4) the expansion of the private securities markets.

Congress has shown interest in issues relating to the asset management industry. During the 116th Congress, lawmakers have held related hearings on asset management, financial innovation, investor protection, financial stability, and leveraged lending. Three areas that have been of particular interest to many are as follows:

Whether the asset management industry has any implications for financial stability in the United States. Some financial authorities state that asset management companies did not pose much concern to financial stability during the 2007-2009 financial crisis period, with the exception of money market mutual funds. This is because asset managers are generally agents who provide investment services to clients without taking direct risk of financial loss. But some argue that structural vulnerabilities do exist and could be observed in certain financial instruments. Their implications, however, are uncertain.

Whether regulation of the asset management industry provides sufficient access and protection for retail investors. The investor protection concerns center on investor access restrictions, especially for private funds. Private funds are perceived to have a higher risk and return profile relative to public funds, thus leading to discussions of investor protection and equal access to investment opportunities.

The impact of financial technology on the industry, and whether the current regulatory framework is adequate to address these new technologies. Financial innovation is an integral part of the asset management industry’s development, and it creates policy and regulatory debates regarding the extent to which the new technologies are appropriately served by the existing regulatory regime. One of the common goals of policymaking in this area is to protect investors without hindering innovation.

Capital Markets: Asset Management and Related Policy Issues

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Types of Asset Management Companies

- Public Funds

- Private Funds

- Public Versus Private Funds

- Other Forms of Asset Management

- Operational Components

- Operation of a Fund

- Key Intermediaries

- Regulatory and Risk Mitigation Frameworks

- Asset Management Risks and Regulation Compared With Banking

- Disclosure Requirements

- Investor Access Restrictions

- Examinations

- Securities Investor Protection Corporation

- Risk Mitigation Controls

- Recent Trends

- The Asset-Management Industry's Growth

- Capital Market Financing Outpaces Bank Lending

- Active to Passive Investment Style Shift

- Private Securities Offerings Outpace Public Offerings

- Policy Issues

- Financial Stability

- Money Market Mutual Funds

- Exchange-Traded Funds

- Leveraged Lending

- Investor Protection

- Defining Accredited Investors

- Voting of Proxy Shares

- Fund Disclosure

- Financial Innovation

- Digital Asset Custody

- Nonfinancial Technology Platforms

- Facebook Libra's ETF-Like Characteristics

- Conclusion

Figures

- Figure 1. Selected Public Funds Net Asset Value

- Figure 2. Selected Private Funds Net Asset Value

- Figure 3. Operation of a Mutual Fund

- Figure 4. Nonfinancial Business Financing: A Comparison

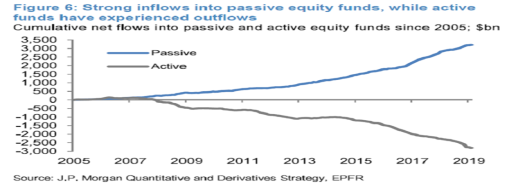

- Figure 5. Cumulative Flows into Passive and Active Equity Funds

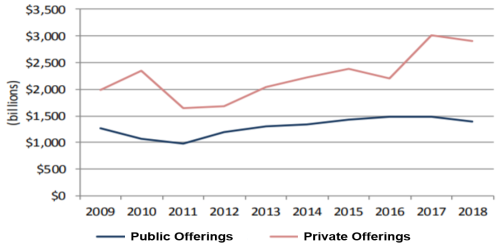

- Figure 6. New Capital Raised in Public and Private Securities Markets, 2009-2018

Tables

Appendixes

Summary

The asset management industry is large and complex. Asset management companies—also known as investment management companies, or asset managers—are companies that manage money for a fee with the goal of growing it for those who invest with them. The most well-known product these companies create are investment funds. Many types of investment funds exist, including mutual funds, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), hedge funds, private equity, and venture capital. Their business practices and the types of regulatory requirements to which they are subject are far from standardized. Investment funds differ by, among other things, asset risk profile, investor access, portfolio company operations, and the ease of buying or selling their shares. In addition to investment funds, the asset management industry also consists of entities that connect funds to investors and other services, such as investment advice providers and custodians.

Asset managers collectively manage trillions in assets, including investment savings, of nearly half of all U.S. households. The industry has experienced periods of high growth largely attributable to retail investors' increased reliance on asset managers to invest their money for them rather than investing their own money themselves.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is the primary regulator overseeing the asset management industry. The industry is governed by a somewhat fragmented regulatory regime stemming from several different statutes. Most of the regulatory framework was created in the 1930s and 1940s, but the business practices and trends affecting the industry are evolving. Examples of this evolution include (1) the rapid growth of the industry; (2) the increasing dependency of American businesses on capital market financing; (3) the shift from active to passive investment style; and (4) the expansion of the private securities markets.

Congress has shown interest in issues relating to the asset management industry. During the 116th Congress, lawmakers have held related hearings on asset management, financial innovation, investor protection, financial stability, and leveraged lending. Three areas that have been of particular interest to many are as follows:

Whether the asset management industry has any implications for financial stability in the United States. Some financial authorities state that asset management companies did not pose much concern to financial stability during the 2007-2009 financial crisis period, with the exception of money market mutual funds. This is because asset managers are generally agents who provide investment services to clients without taking direct risk of financial loss. But some argue that structural vulnerabilities do exist and could be observed in certain financial instruments. Their implications, however, are uncertain.

Whether regulation of the asset management industry provides sufficient access and protection for retail investors. The investor protection concerns center on investor access restrictions, especially for private funds. Private funds are perceived to have a higher risk and return profile relative to public funds, thus leading to discussions of investor protection and equal access to investment opportunities.

The impact of financial technology on the industry, and whether the current regulatory framework is adequate to address these new technologies. Financial innovation is an integral part of the asset management industry's development, and it creates policy and regulatory debates regarding the extent to which the new technologies are appropriately served by the existing regulatory regime. One of the common goals of policymaking in this area is to protect investors without hindering innovation.

Introduction

The asset management industry operates in a complex system with many components. Asset management companies have two major product categories—public funds and private funds. Additionally, a number of intermediaries, such as investment advisers and custodians, provide distribution channels, safeguards, and other essential services to investors and issuers. Nearly half, or 44.8%, of all U.S. households own some form of public funds.1 When operating as expected, the industry functions to pool assets, share risks, allocate resources, produce information, and protect investors.

Asset management companies—also referred to as investment management companies, money managers, funds, or investment funds—are collective investment vehicles that pool money from various individual or institutional investor clients and invest on their behalf for financial returns.2 The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) is the primary regulator of the asset management industry. The main statutes that govern the asset management industry at the federal level include the Investment Company Act of 1940 (P.L. 76-768), the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 (P.L. 76-768), the Securities Act of 1933 (P.L. 73-22), and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (P.L. 73-291).

Public and private funds are distinguished by the types of investors who can access them and by the regulation applied to them. Public funds, such as mutual funds, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), closed-end funds, and unit investment trusts (UITs), are broadly accessible to investors of all types.3 Private funds are limited to more sophisticated institutional and retail (individual) investors, thus the name private fund.4 The main types of private funds are hedge funds, venture capital funds, and private equity.5

The first part of this report provides an overview of the asset management industry and its regulation. Although there is no single definition for the industry, the report generally covers public and private investment funds and the industry components that serve those funds.6 The report also illustrates some of the industry's key risk exposures and the regulations designed to disclose, monitor, and mitigate them.

The second part of this report considers current trends and policy issues, including (1) whether the asset management industry affects the financial stability of the United States; (2) whether regulation of the asset management industry provides sufficient protection for the retail investors who invest money in the industry; and (3) the impact of financial technology, or "fintech," on the industry, and whether the current regulatory framework is adequate to address these new technologies.

Industry Assets

The asset management industry is large and highly concentrated. Exact statistics differ somewhat depending on the source, but one industry report on the world's 500 largest asset managers indicates that the largest U.S. asset managers (i.e., those within the global top 500 ranking) managed around $50 trillion in assets in 2017.7 The top 10 U.S. asset managers alone held $26.2 trillion in assets under management as of year-end 2017 (Table 1).

|

Rank |

Asset Manager |

Assets Under Management |

|

1 |

BlackRock |

6.3 |

|

2 |

Vanguard Group |

4.9 |

|

3 |

State Street Global |

2.8 |

|

4 |

Fidelity Investments |

2.4 |

|

5 |

J.P. Morgan Chase |

2.0 |

|

6 |

Bank of New York Mellon |

1.9 |

|

7 |

Capital Group |

1.8 |

|

8 |

Goldman Sachs Group |

1.5 |

|

9 |

Prudential Financial |

1.4 |

|

10 |

Northern Trust Asset Management |

1.2 |

|

Top 10 Total |

26.2 |

Source: CRS based on data from Willis Towers Watson/Thinking Ahead Institute 500 and Pensions & Investments.

The industry's assets are measured by assets under management (AUM) and net assets. AUM or gross assets refer to the sum of assets overseen by the asset manager. Net assets refer to the value of assets minus liabilities. U.S.-registered investment companies or "public funds" held $21.4 trillion in total net assets as of 2018.8 Private funds, which are not accessible by typical households, held $8.7 trillion in total net assets and $13.5 trillion in AUM as of December 2018.9 In addition, other market intermediaries, such as broker-dealers, held around $3.1 trillion AUM as of second quarter 2018.10

Types of Asset Management Companies

Many types of asset management companies exist. Further, the different types of asset management companies are subject to different regulatory requirements. This section highlights major types of asset management companies, including public funds, private funds, and other forms of asset management.

Public Funds

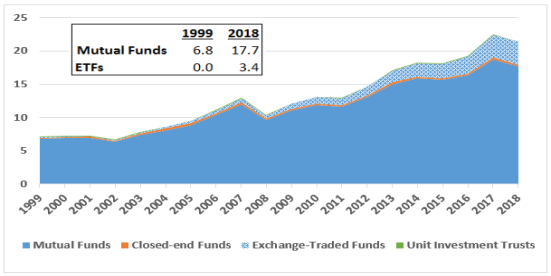

Public funds are pooled investment vehicles that gather money from a wide variety of investors and invest the money in stocks, bonds, and other securities. They are SEC-registered investment companies that are open to all institutional and retail investors in the public, thus the name public funds. Asset holdings of public funds experienced significant growth in the past two decades (Figure 1). At year-end 2018, public funds managed more than $21.4 trillion in assets, largely on behalf of more than 100 million U.S. retail investors.11

The four basic types of public funds are mutual funds, closed-end funds, exchange-traded funds, and unit investment trusts.

Mutual Funds

Mutual funds are the most widely used pooled investment vehicle. They are also called open-ended funds, referring to their continuous offering of shares. Mutual funds do not have a limit on the number of shares they can issue.12 The shares are not traded on exchanges. When investors need to exit their investment positions, they "redeem" shares at net asset value (NAV).13 Redemption means selling shares back to the mutual fund. These technical features, including NAV and redemption, are revisited in the context of compliance and risk controls in "Regulatory and Risk Mitigation Frameworks" section of this report.

Closed-End Funds

A closed-end fund is a publicly traded investment company that sells a limited number of shares rather than continuously offering them. Closed-end fund shares are not redeemable, meaning they cannot be returned to the fund for NAV, but they are traded in the secondary market.14 Investors can exit closed-end funds by buying or selling shares on securities exchanges.15

Exchange-Traded Funds (ETF)

ETFs are pooled investment vehicles that combine features of both mutual funds and closed-end funds.16 ETFs offer investors a way to pool their money into a fund with continuous share offerings that can also trade on exchanges like a stock.17

Unit Investment Trusts (UIT)

UITs invest money raised from many investors in a one-time public offering in a generally fixed portfolio of stocks, bonds, or other investments. It is an investment company organized under a trust or similar structure that issues redeemable securities, each of which represents an interest in a unit of specified securities.18

Private Funds

Private funds, in contrast, are investment companies that operate through exemptions from certain SEC regulation.19 Private funds are also called alternative investments. Relative to public funds, private funds tend to take on higher risk, and they are subject to more investor access restrictions. Private funds are available to only a limited number of qualified investors, thus the name private funds.20

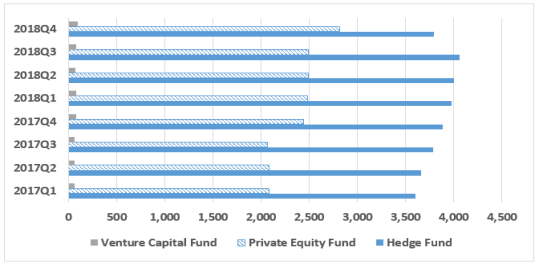

As of December 2018, private funds held $8.7 trillion in total net assets and $13.5 trillion in gross assets under management (Figure 2).21 From the SEC's first available private funds statistics in the first quarter of 2013 to the fourth quarter of 2018, the private fund industry grew more than 60%, primarily led by increases in private equity and hedge funds.22 The rules governing the funds were established as part of the Investment Company Act in the 1940s, but some argue the drafters never foresaw the rise of private funds at such a scale.23 The current private fund landscape thus raises questions regarding if or how the regulations ought to be updated.

The main types of private funds include hedge funds, venture capital funds, private equity funds, and family offices, but these fund types are not mutually exclusive.24 Some use the term private equity interchangeably as a catch-all phrase to describe all types of private funds.25 This report uses the terminology set forth by the SEC in its private funds Form PF reporting system.26

Among all major types of private funds, only venture capital funds and family offices have legal definitions. In 2010, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 111-203; Dodd-Frank Act)27 removed the historical exemption from SEC registration for investment advisers with fewer than 15 clients to "fill a key gap in the regulatory landscape."28 The act also established legal definitions of venture capital funds and family offices, so that these selected private funds could be exempted from the new regulation requirement.29 In addition, private funds with less than $150 million in assets under management continue to be exempted.30

Private Equity Funds

A private equity fund is a pooled investment vehicle that typically concentrates on investments not offered to the public, such as ownership stakes in privately held companies.31 Private equity fund investors include high-net-worth individuals and families, pension funds, endowments, banks and insurance companies.32 According to a 2017 survey, around 88% of institutional investors invested in private equity funds; nearly a third allocated more than 10% of their assets in private equity.33

Venture Capital Funds

Venture capital funds are sources of startup financing for early stage, high-potential firms, such as high-tech startups. Pursuant to the Dodd-Frank Act, the SEC established a definition for venture capital funds in 2011. To be considered for the venture capital exemption from certain investment company regulatory requirements, the fund should generally pursue a venture strategy, cannot borrow funding to incur leverage, and should hold no more than 20% of its capital in nonqualifying investments, among other conditions.34 The legal definition of "venture capital fund" needs to be met in order to qualify for regulatory exemptions.35

Hedge Funds

Hedge funds are pooled investment vehicles that often deploy more "speculative" investment practices than mutual funds, such as leverage and short-selling.36 Among investors, hedge funds are more controversial than other funds because of their high fee structure coupled with reported persistent underperformance.37 Hedge fund fee structures often include an annual asset management fee of 1% to 2% of assets under management as well as an additional 20% performance fee on any profits.38 This fee structure could motivate a hedge fund manager to take greater risks in the hope of generating a larger performance fee, yet only the investors, not the hedge funds, bear the downside risk.

Prior to the Dodd-Frank Act, hedge funds were virtually unregulated, and regulators were largely unaware of the hedge fund market's size, investment strategies, and number of players.39 The Dodd-Frank Act mandated more detailed reporting of hedge funds and other private funds. Confidential filings from hedge funds are now reported to the SEC.40 Despite continuous discussions of whether hedge funds' fees are excessive and their closings, the hedge fund industry remains at peak net assets levels of around $4 trillion (Figure 2).41

Family Offices

Family offices are investment firms that solely manage the wealth of family clients. They do not offer their services to the public and are generally exempt from SEC registration requirements.42 According to a 2018 report, around two-thirds of family offices were established after 2000.43 Owing to their exclusivity, family offices receive minimal regulation and oversight. They have grown rapidly in recent years and are reportedly increasingly becoming an option for some hedge fund managers, who solely manage their own money.44

Public Versus Private Funds

Table 2 compares public and private funds' characteristics. The main differences between public and private funds include the following examples:

- Risk—private funds normally invest in higher-risk assets and deploy more volatile investment strategies. For example, certain private funds focus on funding for startups, which are inherently riskier with higher possibilities for business failure. Certain private funds also have a greater ability to borrow money to invest (leverage), which could multiply the funds' risks and returns.

- Regulation—private funds face less regulation relative to public funds. For example, whereas public funds generally have to calculate daily valuation and maintain periodic public reporting, private funds are not subject to such mandates.

- Investor access—private funds are limited as to the type and the number of investors they can reach, while public funds are available to all investors. These restrictions are meant to protect certain retail investors who are perceived as less sophisticated, given the generally higher risk and lower levels of regulation.

- Portfolio company involvement—a private equity or venture capital fund typically uses client funds to obtain a controlling interest in a nonpublicly traded company (called a portfolio company). This controlling interest normally allows the private fund to have a say in the portfolio company's operations. Public funds, in contrast, typically do not directly affect portfolio company management and operations, except through shareholder voting processes.

- Liquidity—liquidity refers to how easy it is to buy and sell securities without affecting the price. Public funds are considered liquid for investors because of their redemption or exchange trading features, whereas private funds are considered illiquid.

- Holding period

- Private funds often invest in private securities that are not publicly traded.45 This causes private funds to normally have to wait for three to seven years before a "liquidity event" can occur.46 The liquidity events are typically company buyouts or initial public offerings (IPOs).47 Private funds typically realize the gains or losses of their investments only when portfolio companies are sold or go public.

- Public funds mostly invest in publicly traded companies that are considered to offer immediate liquidity. Public funds are not restricted from investing in private securities, but certain public fund regulatory requirements, such as daily valuation, make private investment operations less practical for public funds. As such, public funds largely focus on publicly traded securities and have not significantly undertaken private securities investments.48

- Publicly traded private funds

- Some of the world's largest private fund managers are publicly traded, and thus able to offer company stock level liquidity.49 This means that public investors can directly purchase these fund companies' stocks and gain exposure to the companies' private fund investment portfolios as a whole. Publicly listed asset management firms include Amundi Group, Man Group, Och-Ziff Capital Management Group, Blackstone Group, and KKR. In 2017, they managed $2.4 trillion combined.50

- Publicly traded private funds must concurrently adhere to private fund compliance requirements and restrictions, as well as public security offering standards.51 These private funds separately answer to both their direct fund investors and public shareholders.

|

Fund Type |

NAV ($trillions) |

Publicly Offered |

Main Investors |

Disclosure |

Risk of Loss |

Redemption/Exit |

Leverage |

|

|

Public Funds |

Mutual Funds |

17.7 |

Yes |

Retail, institutional |

High |

Low |

End of day |

Yes with cap |

|

Closed-end Funds |

0.3 |

Yes |

Retail, institutional |

High |

Low |

Intraday (secondary market) |

Yes with cap |

|

|

Exchange-traded Funds |

3.4 |

Yes |

Retail, institutional |

High |

Low |

Intraday (secondary market) |

Yes with cap |

|

|

Private Funds |

Private Equity |

2.8 |

No |

Institutional, certain qualified retail |

Low |

High |

Buyout/IPO |

Yes |

|

Hedge Funds |

3.8 |

No |

Institutional, certain qualified retail |

Low |

High |

Quarterly + lock-up period |

Yes and typically high |

|

|

Venture Capital |

0.1 |

No |

Institutional, certain qualified retail |

Low |

High |

Buyout/IPO |

No (unless limited short-term) |

|

Source: CRS. NAV data from the Securities and Exchange Commission and Investment Company Institute.

Notes: IPO = initial public offering. Buyout = the purchase of controlling share of a company. NAV = net asset value. Public funds NAV as of year-end 2018, private funds NAV as of 4th quarter 2018. The summary characteristics are for selected funds and typical situations only; they are not inclusive of all situations.

Other Forms of Asset Management

Other forms of asset management do not fit tightly into the public or private fund categorization.

Business Development Companies

Business development companies (BDCs) are closed-end funds that primarily invest in small and developing businesses, and that generally provide operational assistance to such businesses in addition to funding. Congress created BDCs in 1980 in amendments to the Investment Company Act of 1940 to "make capital more readily available to small, developing, and financially troubled companies that are not able to access public markets or other forms of conventional financing."52 BDCs are not required to register with the SEC as investment companies, and thus face much less regulation than mutual funds. But they do offer their securities to the public, and their public offerings are subject to full SEC reporting requirements.53

Fund of Funds

A fund of funds is an investment fund that invests in other funds. The fund of funds design aims to achieve asset allocation, diversification, hedging, or other investment objectives. The SEC estimates that almost half of all registered funds invest in other funds.54

Operational Components

The asset management industry operates in a complex system with many components, including different types of funds and various intermediaries. This section explains the operation of a typical public fund as well as other prominent actors supporting the fund and the efficient operations of the industry.

Operation of a Fund

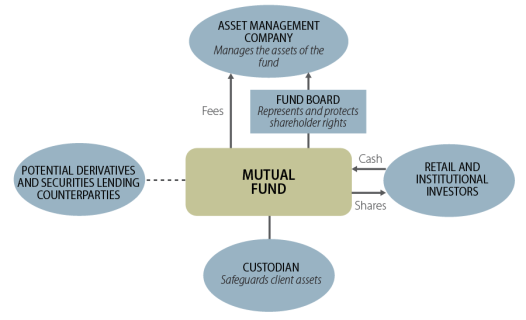

Funds typically operate through asset management companies (AMCs). The largest AMCs, as measured by assets under management, are shown in Table 1. The AMCs can manage multiple funds of different types. Each fund has an Investment Management Agreement that designates the AMC to manage the fund's portfolio composition and trading. As Figure 3 illustrates, the end investors own the fund and contribute cash for its shares, custodians safeguard the fund assets, and the fund can also interact with certain counterparties for other transactions.55

|

|

Source: CRS. |

Key Intermediaries

The main players supporting the asset management industry include those who are more directly related to the flow of capital, such as financial advisers and others who serve back-office or administrative functions, such as data and research, asset safekeeping, and shareholder voting. Because funds are also financial products that are sold to investors, investment advisers and broker-dealers are the most commonly used retail sales and distribution channels. This section discusses several selected groups of players that frequently appear in asset management policy discussions.

Investment Advisers

An investment adviser is "any person or firm that for compensation is engaged in the business of providing advice to others or issuing reports or analysis regarding securities."56 Investment advisers generally include money managers, investment consultants, financial planners, and others who provide advice about securities.57 Investment advisers meeting the SEC legal definition must register with the SEC.58 As of 2018, the SEC oversaw around 13,200 registered investment advisers.59

Broker-Dealers

Brokers and dealers are often discussed together, but they are two different types of entities. Brokers conduct securities transactions for others.60 They are generally paid a commission on securities sales. Dealers conduct securities transactions for their own accounts.61 Most brokers and dealers must register with the SEC and also comply with the guidance of self-regulatory organizations (SROs).62 The Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) is the main SRO for the broker-dealer industry. FINRA writes and enforces broker-dealer rules, conducts examinations, and provides investor education.63 As of 2018, FINRA supervises around 3,596 member firms and 626,127 individual registered reps.64

|

Different Standards of Care: Investment Advisers Versus Broker-Dealers Investment advisers and broker-dealers play similar roles with regard to helping retail and institutional investors make financial decisions. However, they are subject to different standards of care, with tighter standards for SEC-registered investment advisers:

Research cited by the SEC shows that retail investors generally do not understand the difference between investment advisers and broker-dealers or their different standards of care. Aiming to improve the quality and transparency of financial advice, the SEC finalized a package of rules, including Regulation Best Interest (17 C.F.R. §240), in 2019. |

Custodians

Custodians provide safekeeping of financial assets. They are financial institutions that do not have legal ownership of assets but are tasked with holding and securing the assets, among other administrative functions.65 As mentioned in more detail in the "Asset Management Risks and Regulation" section of this report, client assets are not owned by an adviser or fund. As part of the regulatory requirements to protect investors, client assets are generally required to be safeguarded by a qualified custodian who maintains possession and control of the assets. In the past 90 years, financial custody has evolved from a system of self-custody to custodians playing key component of asset management operations. Today, four banks (BNY Mellon, J.P. Morgan, State Street, and Citigroup) service around $114 trillion of global assets under custody.66

Information Services

The asset management industry in its essence is also an investment research industry that aggregates data and analysis for investment decision-making. Owing to the sophistication of the industry's technology and analysis, there are many data vendors and research providers, including national exchanges, data and technology aggregators, and sell-side researchers involved.67

The Proxy System

A proxy vote is a vote cast by others on behalf of a shareholder who may not physically attend a shareholder meeting. This is how the vast majority of shareholder votes are cast. The SEC requires investment managers to vote as proxies in the best interest of their clients and disclose their voting policies and records to clients.68 During the 2018 shareholder meeting season, there were more than 4,000 shareholder meetings involving over 259 million proxy votes.69 Under the current system, shareholders cast their votes through a variety of intermediaries that assume the functions of forwarding proxy materials, collecting voting instructions, voting shares, soliciting proxies, tabulating proxies, and analyzing proxy issues.70 Different aspects of this complex system have attracted years-long policy debates regarding proxy reform.71

Regulatory and Risk Mitigation Frameworks

The asset management industry's legislative history is relatively long and complex. The current regulatory regime governing the asset management industry was not a comprehensive design from inception, but rather developed through many iterations of adjustments and expansions. Therefore, the asset management industry is overseen by a somewhat fragmented regulatory regime with areas of disconnect between business practices and the legal definitions describing them.72

Congress created the SEC during the Great Depression to restore public confidence in the U.S. capital markets. Early policymaking in the 1930s focused on full disclosure, with the specific intention that publicly traded companies tell the whole truth about any material issues pertaining to their securities and the risks associated with investing in them.73 However, Congress realized that the disclosure-based approach alone was not enough to deter fraudulent and abusive activities in the asset management industry, which flourished in the 1920s and 1930s. Congress thus directed the SEC to conduct a 1½-year study of the issue in the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935.74 The SEC took four years, resulting in a four-part study with six additional supplemental reports.75 Based on the SEC research and subsequent hearings, in 1940, Congress introduced two new laws to govern the asset management industry—the Investment Company Act of 1940 and the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. These statutes and regulations required those who manage and distribute funds to treat investors fairly and honestly.76 The textbox below describes the individual laws,77 which generally apply to the asset management industry as follows:

- Asset management companies must comply with the Investment Company Act of 1940 or gain exemption from its requirements.

- Funds' portfolio managers or investment advisers generally must register with the SEC under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940.78

- The funds themselves are securities, and thus subject to federal securities regulation in relation to securities offering and trading, including the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934.79

Asset Management Risks and Regulation Compared With Banking

After the 2007-2009 financial crisis, Congress directed more attention toward financial services sector risks and policy solutions. In some congressional discussions, risks in the banking and asset management industries were jointly debated.80 Although similarities exist between the two industries' financial risks, there are fundamental differences. These differences are derived from the industries' different business models, risk controls, and risk mitigation backstops.

Agent-Based Versus Principal-Based Models

The asset management framework is an agent-based model that separates investment management functions from investment ownership.81 This is different from the principal-based model for banking, in which banks own and retain the assets and risks. In many ways, asset managers are viewed as agents that perform investment management services. They are compensated through service or performance fees, but otherwise they are insulated from the investment returns or their clients' account losses.82 Because their clients' assets are not owned by the funds, asset managers routinely exit the market without significant market impact.83

Even when under market stress, the risks associated with asset managers winding down differ greatly from those associated with bank liquidations. Whereas bank failures may lead to government financial intervention for either recovery or resolution, asset managers do not own or guarantee client assets.84 Their clients bear investment performance risks and can directly transfer assets out of failing asset management firms. With that said, macro-prudential tools for detecting and mitigating systemic risks in the banking sector have been considered for asset management firms. For example, the Dodd-Frank Act mandated the SEC implement annual stress testing for certain asset managers.85

Disclosure Requirements

Disclosure requirements are the cornerstone of securities regulation.86 The purposes of and requirements for disclosure differ for public and private funds. Public funds normally provide public disclosures to inform investors. Private funds normally provide SEC-only disclosures that allow the agency to monitor risks and inform policy, while maintaining confidentiality.87

Public Disclosure

Public disclosures allow the public to make informed judgments about whether to invest in specific funds by ensuring that investors receive significant information on the funds. The disclosure-based regulatory philosophy is consistent with Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis's famous dictum that "sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman."88 Public disclosures, including mutual fund and ETF prospectuses, are available for free from the SEC public disclosure portal.89 SEC-registered investment advisers, for example, are also required to publicly report their business operations and certain disciplinary events.90

Nonpublic SEC-only Disclosure

A number of SEC-only reporting requirements apply to public and private funds and their advisers. The private disclosures are often for purposes of regulatory review, risk monitoring, and policymaking. The SEC normally does not make information that identifies any particular registrant publicly available, although it can release certain information in aggregate and use the information in enforcement actions. Examples of private disclosure include public fund liquidity position reporting91 and periodic reporting of private funds by SEC-registered investment advisers pursuant to Dodd-Frank Act requirements.92

Investor Access Restrictions

Public funds are open to all investors, but private funds' investor access is restricted by several intersecting federal laws that govern different regulatory requirements for securities offerings, investment management companies, and investment advisers. Only those investors who meet certain definitions can invest in private funds without triggering related regulatory requirements. Funds can avoid additional regulatory requirements by adhering to restrictions on the types of investors permitted to invest in the fund; some examples follows:93

- Accredited investor—if a fund's investors meet the definition, such a fund could qualify for private securities exemption.94

- Qualified client—if a fund's investors meet the definition, the fund manager could receive performance-based compensation.95

- Qualified purchaser—if a fund's investors meet the definition, the fund could be exempted from registering as an investment company.96

Most private funds choose to comply with investor definitions to preserve their scaled-down regulatory requirements relative to public funds. The specifics of the investor access definitions, especially the accredited investor definition, have been a source of policy debate.

Examinations

The SEC's Office of Compliance Inspections and Examinations (OCIE) is responsible for conducting examinations and certain other risk oversight of the asset management industry.97 In addition, self-regulatory agencies, such as FINRA, also conduct examinations of their members under SEC oversight.98

OCIE examinations focus on compliance, fraud, risk monitoring, and informing policymaking. OCIE has 1,000 employees in 11 regional offices and headquarters. Approximately 10,000 mutual funds and ETFs, 13,200 investment advisers, and 3,800 broker-dealers, among other regulated entities are subject to potential examinations.99 The OCIE completed more than 3,000 examinations in fiscal year 2018.100

Securities Investor Protection Corporation

The federal government does not guarantee or insure the value and performance of investment management accounts. As the common investment disclaimer—"past performance is no guarantee of future results"—suggests, due to unpredictable market fluctuations, capital markets investors could experience underperformance or lose their principal.101 Investors should be prepared to absorb their own losses.

When a capital markets firm fails, certain losses could possibly receive limited payouts for investors from the Securities Investor Protection Corporation (SIPC). However, the nature and the level of payouts are different than those associated with the banking insurer Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

SIPC is a nongovernment nonprofit corporation created by the Securities Investor Protection Act.102 It insures up to $500,000 of cash and securities (with a $250,000 limit for cash) in brokerage accounts to protect customers against cash and securities losses if their brokerage firm fails.103 SIPC only protects the custody function of the broker-dealers, which means it works to restore any assets missing from customers' accounts but it does not protect the principal against the decline in market value of investments.104 The FDIC, in contrast, is a government organization that insures up to $250,000 of deposits, including principal, in banks and thrift institutions when these institutions fail.105

Risk Mitigation Controls

The asset management industry faces a number of risks. Some of them are inherent in the industry's agent-based business model whereas others are more common to financial services institutions. This section lays out examples of the risk factors and attendant mitigation controls to help policymakers better comprehend the rationale behind the regulatory requirements. This section also contains a summary table (Table 3) providing context on how certain existing regulations fit into risk mitigation policy goals.

Conflict of Interest

- Context: Conflicts of interest may occur in any principal-agent paradigm within which one entity (agent) makes decisions on behalf of another entity (principal).106 In the context of asset management industry client relationships, the central concern is that asset managers (agents) may not act in the best interest of investors (principals). An example of a conflict of interest would be an investment adviser directing clients' investments toward products that generate higher sales commissions, rather than products that best fit the clients' financial needs.

- Examples of mitigation controls: SEC-registered investment advisers are fiduciaries,107 meaning they have a legal obligation to act in the best interest of their clients. FINRA also casts a similar, yet less rigorous suitability requirement for broker-dealers. The standard requires broker-dealers to make investment recommendations to suit client financial needs.108 In addition, the SEC adopted Regulation Best Interest in June 2019 to address certain conflict of interest concerns in financial advisory services.109 The proposal aims to further prevent financial advisers from placing their own financial or other interests ahead of the best interest of their clients.110

Liquidity

- Context: Liquidity, as mentioned previously, is commonly defined as the ease of buying or selling assets without affecting their prices. The easier the assets are to sell, the higher their liquidity. The liquidity issue could be especially important during market distress, when factors like cash needs and exceptional volatility in asset valuations could drive panic reactions in the market. Different funds have different types of liquidity risk concerns. Mutual funds that allow investors to redeem their shares daily need to maintain sufficient liquid assets to meet shareholder redemptions and minimize the impact of the redemptions on the funds' remaining shareholders.111 Private funds present different concerns because, in most cases, their investors enter into illiquid investments knowing that they could experience several years of holding periods.112 Private funds generally do not promise daily redemption, and investors in private funds cannot easily sell their positions to meet urgent cash needs.

- Examples of mitigation controls: Funds that offer frequent redemption as a product feature must maintain liquid assets to meet potential redemptions. Under the SEC liquidity rule, such funds must categorize their investments into four different types and limit their illiquid investments to no more than 15% of the funds' net assets.113

Leverage

- Context: Leverage generally refers to the use of borrowed funding to invest, which may multiply risks and returns.114 High leverage could complicate funds' investment structures and increase risks to both individual investors and the financial system as a whole, due to its effects in multiplying both losses and returns.115

- Examples of mitigation controls: Mutual funds and closed-end funds are subject to a 300% asset coverage requirement.116 This is a leverage ratio of 33%, meaning the fund cannot borrow an amount exceeding a third of its portfolio size. By contrast, most private funds do not have leverage restrictions.

Operational Risks

- Context: Operational risks arise from operational challenges and business transaction issues. Operational risks are especially important for the asset management industry because the industry manages client accounts. Accurate client account recordkeeping and transfer, asset safeguards, information sharing, and cybersecurity are some areas of operational importance.

- Examples of mitigation controls: The SEC's custody rule requires registered investment advisers to engage qualified custodians to (1) have possession and control of assets, (2) undergo annual surprise examinations, (3) have a qualified custodian maintaining client assets, and (4) send account statements directly to the clients instead of to funds, among other requirements.117

|

Risk Factors |

Compliance and Risk Controls |

Examples of Strongly Affected Parties |

How It Works |

|

|

Investor Protection |

Risk transparency |

Disclosure requirements |

Public funds |

Requires public disclosure of portfolio composition and risks so that investors are informed |

|

Retail investor exposure |

Investor access restrictions |

Private funds |

Disallows ordinary retail investors to purchase private funds that are perceived as having higher risk than public funds |

|

|

Conflict of interest |

Fiduciary and suitability standards |

Broker-dealers and investment advisers |

Requires advisers to place the best interest of clients ahead of their own interests (i.e., sales commissions) |

|

|

Investment Portfolio Risk |

Liquidity |

Liquidity rules and daily NAV valuation |

Mutual funds |

Ensures the availability of liquid assets to meet investor redemption needs |

|

Leverage |

Leverage ratio requirements |

Business development companies |

Caps the amount investment companies could borrow to reduce portfolio risk and complexity for those funds that are selling to retail investors |

|

|

Operational Risk |

Asset safekeeping |

Custody rule |

Digital assets management |

Makes sure there is a third party custodian to safeguard and ensure the availability of investment portfolio assets |

Source: CRS.

Notes: "Examples of strongly affected parties" refer to the entities within the asset management ecosystem that are likely to be strongly affected by the risk control requirements. The column does not list all the affected parties. The table is for illustration purposes only and is not inclusive of all risk factors or mitigation controls. See "Risk Mitigation and Controls" section of the report for explanation of the different factors in column one.

Recent Trends

Over the past several decades, the asset-management industry has undergone several changes that may have important implications for public policy. This section discusses a number of these changes, including (1) the industry's overall growth; (2) increased reliance on capital markets for financing rather than bank loans by American businesses; (3) a shift from active to passive investment style; and (4) the expansion of private securities markets.

The Asset-Management Industry's Growth

In the past two decades, the asset-management industry has grown significantly because of increased use of defined-contribution retirement plans,118 asset appreciation, and changes in investment styles and preferences, among other things (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).119 Over the past 70 years, investors have largely shifted from investing directly themselves to investing indirectly through asset managers. For example, in the 1940s, almost all corporate equities were held by households and nonprofits, whereas in 2017, direct holdings by individuals made up less than 40% of total holdings.120 Some argue that the percentage of equity directly held by individuals could be closer to 20%.121 As a result of these changes, asset managers now dominate the investment decisionmaking on behalf of retail investors and other institutions. Their influence on both investors and the companies they invest in has expanded.

Capital Market Financing Outpaces Bank Lending

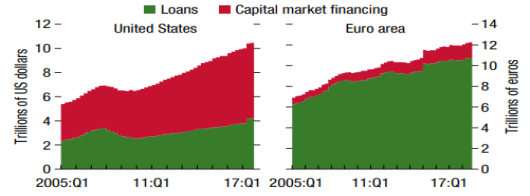

The importance of the asset-management industry has also increased because of changes in the relative importance of the capital markets and banks. Specifically, growth in capital markets financing (i.e., the issuance of bonds and other debt securities) significantly outpaced growth in bank loans (Figure 4).

This general trend has increased the relative importance of asset managers, who represent major holders of such bonds and debt securities. For example, mutual funds and ETFs held about 21% of all U.S. corporate bonds in 2018, more than double their percentage of such holdings in 2009.122 The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has observed that this shift may be attributable to tighter banking regulation, rising compliance costs, and bank deleveraging following the 2007-2009 financial crisis.123 As Figure 4 illustrates, U.S. capital markets play a much more dominant role in business financing relative to the Euro area.

Active to Passive Investment Style Shift

The asset-management industry has also witnessed a trend away from active and toward passive management, whereby asset managers do not actively select funds' portfolio assets, instead pegging investments to an index, such as the S&P 500. In recent years, passive investment through index mutual funds and ETFs has displaced active investment (Figure 5).124 This trend has mostly been driven by passive funds' lower costs through management fee savings and superior performance. According to a 2016 S&P Global study, for example, active stock managers underperformed their passive-fund targets more than 80% of the time over 1-year, 5-year, and 10-year periods.125

|

Figure 5. Cumulative Flows into Passive and Active Equity Funds ($ Billions) |

|

|

Source: J.P. Morgan Quantitative and Derivatives Strategy and EPFR Global. |

The rise of passive investing has generated criticism from active asset managers. Some active managers are concerned that the growth of passive investing will undermine price discovery through reduced fundamental research by active asset managers.126 They argue this could create systemic risk concerns through correlations and volatility, affecting the efficient allocation of capital.127 Regarding financial stability, a recent Federal Reserve whitepaper concludes that the shift from active to passive investment has probably reduced liquidity transformation risks while amplifying market volatility and asset management industry concentration.128 Finally, some argued that actively managed funds perform better than passive strategies when markets are less efficient. If this argument is true, then actively managed funds may be able to capitalize on market inefficiencies caused by growth in passive investment, enabling continued growth in active management as well.

Private Securities Offerings Outpace Public Offerings

The asset-management industry has also taken on increased importance because of a significant rise in the volume of private securities offerings.129 Because many asset managers purchase large volumes of private securities, this shift has led the asset-management industry to occupy an increasingly central role in U.S. financial markets. In 2018, American companies raised roughly $2.9 trillion through private offerings—more than double the size of public offerings that year.

|

Figure 6. New Capital Raised in Public and Private Securities Markets, 2009-2018 |

|

|

Source: SEC. Notes: Dollar figures are not inflation adjusted. |

The increase in the volume of private securities offerings has also attracted the attention of policymakers, some of whom have proposed measures to increase investor access to private securities markets. For example, a type of closed-end fund, referred to as an interval fund, can conduct periodic repurchases generally every 3, 6, or 12 months.130 Because of the longer intervals, these funds are better able to involve less liquid assets such as private securities. In a 2017 report, the Treasury recommended the SEC review the rules governing interval funds.131 The SEC also explored the potential of interval funds in its 2019 concept release regarding private securities markets.132

Policy Issues

The increased importance of the asset-management industry raises a variety of policy issues. This section discusses several of these issues, including financial stability, investor protection, and financial innovation.

Financial Stability

Financial stability typically refers to the ability of the financial system to withstand economic shocks and satisfy its basic functions: financial intermediation, risk management, and capital allocation.133 Policymakers attempting to safeguard financial stability generally focus on the minimization of systemic risk—the risk that the entire financial system will cease to perform these functions. Former Federal Reserve Governor Daniel Tarullo has identified four possible sources of systemic risk:

- Domino or spillover effects—when one firm's failure imposes debilitating losses on its counterparties.

- Feedback loops—when fire sales of assets depress market prices, thereby imposing losses on all investors holding the same asset class.

- Contagion effects—a run in which investors suddenly withdraw their funds from a class of institutions or assets.

- Disruptions to critical functions—when a market can no longer operate because of a breakdown in market infrastructure.134

According to an international financial organization, the Financial Stability Board, asset-management companies did not display particularly large financial stability concerns during the 2007-2009 financial crisis, with the exception of money market mutual funds (MMFs).135 This is a result of the fact that asset managers are generally agents who provide investment services to clients rather than principals who invest for themselves.136 They manage large amounts of assets, but do not have direct ownership of them. As such, asset managers are largely insulated from client account losses. This does not mean that the industry is free of financial stability concerns. Actual market events show that even perceived-to-be-safe funds could trigger financial system instability. For example, the money market mutual fund industry triggered market disruptions in 2008 and accelerated the 2007-2009 financial crisis. Before that, hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management's failure in 1998 also demonstrated that the transmission of risks from one event can broadly affect the functioning of the financial system.137

The Financial Stability Board identified several asset management structural vulnerabilities that could present financial stability risks. These vulnerabilities include liquidity mismatch, leverage within investment funds, operational risk and challenges under stressed conditions, and certain lending activities of asset managers and funds.138 This section uses three examples—money market mutual funds, ETFs, and leveraged lending—to illustrate the context of selected asset management structural vulnerabilities and the extent to which these vulnerabilities could cause financial stability concerns.

Money Market Mutual Funds139

Money market mutual funds (MMFs) represent one corner of the asset-management industry that has generated systemic-risk issues. MMFs are mutual funds that invest in short-term debt securities, such as U.S. Treasury bills or commercial paper (a type of corporate debt).140 Because MMFs invest in high-quality, short-term debt securities, investors generally regard them as safe alternatives to bank deposits even though they are not federally insured like bank deposits.141 Like the shares of other mutual funds, MMF shares are generally redeemed at net asset value (NAV), meaning investors sell shares back to a fund at a per share value of the fund's assets minus its liabilities.

Some MMFs, however, operate somewhat differently than most other mutual funds. Specifically, some MMFs aim to keep a stable NAV at $1.00 per share, paying dividends as their value rises and thereby even more closely mimicking the features of bank deposits. If its stable NAV drops below $1.00, which rarely occurs, it is said that the MMF "broke the buck." On September 15, 2008, Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. filed for bankruptcy. The next day, one MMF, the Reserve Primary Fund, broke the buck when its shares fell to 97 cents after writing off the debt issued by Lehman Brothers.142 This event triggered an array of market reactions and accelerated the 2007-2009 financial crisis.143 Ultimately the Treasury Department intervened with an emergency guarantee program for MMFs as one of the ways to address the crises.144

MMFs thus became a known financial stability concern, demonstrating clearly that they are susceptible to sudden large redemptions (runs) that can cause dislocation in short-term funding markets. MMFs are vulnerable to runs because shareholders have an incentive to redeem their shares before others do when there is a perception that the fund could suffer a loss. To address this concern, the SEC promulgated MMF rules in 2010 and 2014 mandating that institutional municipal and institutional prime MMFs float their NAV from stable value. The SEC also provided new tools to the MMFs' boards, allowing them to impose fees and redemption gates to discourage runs.

Policy discussions continued after the 2014 revisions, especially about whether the MMFs' NAV should be floating or stable, generating controversy and attracting congressional interest. For example, the Consumer Financial Choice and Capital Markets Protection Act of 2019 (S. 733) would require the SEC to reverse the floating NAV back to a stable NAV for the affected MMFs. A floating NAV reflects more closely the actual market value of the fund. Proponents believe the floating NAV could (1) reduces investors' incentive in distressed markets to run because of the difference between stable value and the actual market value; (2) allows investors to understand price movements and market fluctuations, and (3) removes the implicit guarantee of zero investor losses through stable value that could lead to unrealistic expectations of safety.145 Opponents believe that floating NAV does not solve the issue of investors fleeing. For example, one academic research article concludes that European MMFs that offer similar structures to floating NAV did not experience significant reduction in run propensity during market distress.146 In addition, providing floating NAV requires calculation time and more tax, accounting, and disclosure related business model changes.147 Opponents also point to the volume decline of affected MMFs since the reform as an example of a shrinking MMF market that may create working capital shortages for business and municipal operations.148 Others argue that because the MMF reform has been fully implemented since October 2016, it makes sense to study the actual effectiveness and impact of the reform before considering changes.149

|

Stress Testing for Asset Management Firms Stress testing generally refers to a forward-looking quantitative evaluation of the impact of stressful economic and financial market conditions. As part of the broader legislative response to the 2007-2009 financial crisis, the Dodd-Frank Act requires regulators to establish stress tests for banks and certain asset management firms. The SEC is responsible for establishing stress testing methodologies for broker-dealers, registered investment companies, and registered investment advisers with $10 billion or more in total consolidated assets. The stress tests are to include baseline, adverse, and severely adverse scenarios, and the results of the stress testing must be reported to the SEC and the Federal Reserve Board. As part of the SEC's 2014 MMF reform, MMFs are required to test their abilities to maintain weekly liquid assets of at least 10% and to minimize principal volatility in response to several SEC-defined hypothetical stress scenarios, including: (1) increases in the level of short-term interest rates, (2) the downgrade or default of particular portfolio security positions, and (3) the widening of spreads in various sectors.150 The SEC has not yet implemented the Dodd-Frank Act stress-testing requirements for asset managers. A 2017 Treasury Department report states that the Treasury does not support the use of banking sector prudential stress testing on investment advisers and investment companies because the MMF reform stress testing requirements already "satisfy the spirit of" the Dodd-Frank Act's stress testing requirements.151 In the 116th Congress, the Alleviating Stress Test Burden to Help Investors Act (H.R. 3987) would exempt nonbanks from certain Dodd-Frank stress test requirements. There are also others who support stress tests as an important systemic risk mitigation tool. |

Exchange-Traded Funds

Some commentators have also argued that ETFs raise certain systemic-risk concerns. The vast majority of all ETF assets are passively managed or index-based; thus investors often view the high growth in ETFs as one of the driving forces behind the passive investment trend the report discusses in the previous section. With U.S. ETFs accounting for more than $3.4 trillion in assets under management and 30% of all U.S. equity trading volume in 2018, ETFs' scale and continued growth give rise to financial stability considerations.152

The key systemic-risk issue surrounding certain ETFs involves liquidity mismatch. Liquidity mismatch generally points to a relatively complex ETF operational structure that offers buying and selling activities at both the fund level and the portfolio asset level. If the amount of liquidity differs between the two levels, for example, if the ETF shares trade differently than the underlying portfolio ETF holdings of stocks or other assets, there could be a liquidity mismatch.153 Some argue this liquidity mismatch could amplify market distress and potentially trigger fire sales that further depress asset prices and worsen market conditions. In contrast, others have argued that liquidity provision through the ETF structure is additive, meaning an ETF's liquidity is at least as great as that of its underlying assets.154 Other commentators have argued that not all ETFs are created equal. The majority of ETFs are "plain-vanilla" index-tracking products that are considered lower risk. However, there is also a growing subset of complex, higher-risk ETFs that is a source of greater concern. To add to the confusion, the industry does not currently have a consistent naming convention to clearly differentiate between the types of products that are higher risk.155

On September 26, 2019, the SEC established a comprehensive listing standard for ETFs only. Prior to that, prospective ETF issuers typically must have been approved by the SEC under an exemption to the Investment Company Act. The new ETF approval process replaces individual exemptive orders with a single rule for plain-vanilla ETFs. The approach excludes certain higher-risk ETFs and mandates new disclosures and other conditions on index-based and actively managed ETFs.156

Leveraged Lending

Leveraged lending, also referred to as leveraged loans, is financing made to below investment grade companies (i.e., companies with a credit rating below BBB-/Baa3), which tend to be highly indebted.157 Leveraged lending received its name because of the recipients' high-debt-to-earnings leverage. Most leveraged loans are syndicated, meaning that a group of bank or nonbank lenders, including asset managers, collectively funds a single borrower, in contrast to a traditional loan held by a single bank.158 Some regulators consider syndicated loans to be an emerging regulatory gray area that is not fully overseen by either banking or securities regulators.159

Leveraged loans generally present higher risks than other forms of lending because they involve riskier borrowers and often feature relatively weak investor safeguards (indicated by a weak "covenant") and relatively weak capabilities for loan repayment, indicated by high ratios of debt to earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA).160 During the past decade, the U.S. leveraged loan market experienced rapid growth, deteriorating credit quality, and decreased repayment capabilities (Table 4). However, the total amount of leveraged loans outstanding remained relatively low at around $1 trillion as of 2018. Nonbanks make up around 90% of the leveraged loan primary market investor base as of 2017.161 Mutual funds and hedge funds held 21% and 5% of leveraged loans in 2017 respectively, with mutual funds' share of the market more than doubling between 2006 and 2017.162 In addition, nearly 60% of U.S. leveraged loans are packaged into a type of structured credit called a collateralized loan obligation (CLO).163 CLOs are then sold to institutional investors, including asset managers, banks, and others, with the asset management industry holding the riskier CLO tranches and banks holding the higher-quality tranches.164 Mutual funds and other investment vehicles hold more than 20% of CLOs.165

|

U.S. Leveraged Loan Market Characteristics |

2007 |

2018 |

|

Outstanding Leveraged Loans ($ billions) |

$554 |

$1,147 |

|

U.S. Issuance (percent of global issuance) |

66.9% |

75.8% |

|

Covenant Quality Index |

2.6 |

4.1 |

|

Covenant Lite Share (percent of new issuance) |

29.2% |

84.7% |

|

Total Debt/EBITDA (times) |

4.9 |

5.3 |

Source: IMF, Global Financial Stability Report, April 2019.

Notes: EBITDA = earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization. Covenant = certain credit agreements that serve as a measurement of the degree of investor protection. A higher covenant quality index score denotes weaker covenant quality.

Multiple financial regulators and Members of Congress have voiced concerns about leveraged loans' risks and implications for financial stability.166 However, other commentators have argued that leveraged loans are resilient and stable, claiming unwarranted fears.167

Leveraged lending raises a variety of policy issues, including the following:

- Market opacity. Leveraged lending, particularly the increase of covenant-lite loans, couples high risk with relative lack of transparency, potentially leading to unexpectedly high losses and shocks to the financial system (Table 4). It is unclear, as discussed below, the degree to which contagion across the financial system would result from this.

- Liquidity mismatch. Public funds expect easy entry and exit through daily redemption or intraday trading, whereas leveraged loans, which could serve as underlying assets to funds, trade infrequently and take longer to settle. These features of leveraged loans have prompted the Chairman of the SEC to caution that investors should be aware of their relative illiquidity.168

- The loan syndication process and federal oversight. Leveraged loans are usually syndicated by groups of institutional investors, including asset managers. Some regulators and researchers worry that certain leveraged loans are less regulated than other financial products like bonds and bank loans.169

Contagion risk. Given the leveraged loan market's size and investor composition, some experts have argued that leveraged lending raises concerns about financial contagion. However, most investors in leveraged loans are nonbanks, with the asset management industry holding a significant portion of total outstanding exposure. As a result, some commentators have argued that direct financial losses from leveraged loans would largely stop at the investor level, instead of being multiplied throughout the interconnected financial system by banks.170 The Chairman of the Federal Reserve, for example, has indicated that while leveraged loans raise some concerns, they "do[es] not appear to present notable risks to financial stability."171

Data gap. Some analysts have argued that the lack of available information through data collection and sharing on CLO holdings has prevented the industry and the regulators from monitoring risks in the leveraged lending market.172

Investor Protection

Investor protections attempt to prevent investors from being harmed due to inappropriate risk exposure, conflicts of interest, or abusive conduct. This section discusses certain policy debates concerning investors' access to private funds, fund disclosures, and asset managers' voting of clients' stocks.

Defining Accredited Investors173

Some private funds are limited to "accredited investors"—a limitation that has generated debate about which categories of investors should be eligible for this status. An individual can qualify as an accredited investor if he or she (1) earned more than $200,000 (or $300,000 together with a spouse) in annual gross income during each of the prior two years and can reasonably be expected to earn a gross income above that threshold in the current year, or (2) has a net worth of more than $1 million (either alone or together with a spouse), excluding the value of their primary residence.174 Institutions can also qualify as accredited investors if they own more than $5 million in assets. A number of regulated entities, such as banks, insurance companies, and registered investment companies, automatically qualify as accredited investors.

Some commentators have criticized the SEC's existing rules for determining accredited investor status, arguing that income and net-worth criteria bear little relationship to investor sophistication. These critics contend that the current accredited investor definition is both over- and under-inclusive, capturing wealthy but unsophisticated investors while excluding those who are well-informed but less affluent. In addition, given the trend of private securities offerings outpacing public offerings, some observers are concerned about ensuring equal access to investment opportunities and the diversification benefits from allocating capital across the full spectrum of public and private securities and funds. Commentators have accordingly discussed expanding the accredited investor definition to (1) account for individuals with financial training or demonstrated financial experience, (2) allow investors to opt-in to private market investment opportunities, or (3) expand the eligible accredited investor base in other ways, subject to certain limitations.175

Voting of Proxy Shares

Proxy voting represents another issue involving investor protection that has taken on increased significance. Asset managers have fiduciary duties to vote the proxies of their public company voting shares on their clients' behalf.176 Some asset managers outsource proxy voting and research to proxy advisory firms, whereas others operate these functions in-house. Commentators have identified a number of policy issues involving the proxy system, including (1) stewardship—whether asset managers and proxy advisory firms are in fact voting in their clients' best interests; and (2) accuracy—whether the actual votes are tabulated correctly. These topics are critically important because proxy voting can often decide the strategic directions of publicly traded companies. To address these issues, the SEC issued a concept release soliciting public feedback on the proxy system in 2010.177 The SEC has also held multiple roundtables to discuss the proxy process, most recently in November 2018.178

Fund Disclosure

Ensuring full and fair disclosure of material information is a key objective of the federal securities laws. To promote these goals, the SEC has implemented a series of initiatives to improve the investor experience by updating the design, delivery, and content of fund disclosure. For example, after longstanding policy debate, the SEC adopted Rule 30e-3 in June 2018 to allow certain investment funds to transmit shareholder reports digitally as the default option.179 Supporters of this rule point to its environmental and economic benefits, including its estimated $2 billion savings over a 10-year period.180 In contrast, the rule's opponents have voiced concerns over the usefulness of electronic reports for elderly and rural investors who may lack access to or familiarity with the Internet.181 The SEC continues to seek public input on the fund disclosure and retail investor experience, including shareholder reports, prospectuses, advertising, and other types of disclosure.182

Financial Innovation

Financial innovation is an integral part of the asset management industry's development. Innovation raises policy and regulatory issues, including (1) whether new technologies and practices have outgrown or are sufficiently served by the existing regulatory system; (2) how the regulatory framework can achieve the goal of "same business, same risk, same regulation";183 and (3) how to protect investors without hindering innovation. This section explains policy challenges involving these general issues.

Digital Asset Custody

Digital-asset custody has recently attracted regulatory attention. Under the SEC's Custody Rule, custodians of client assets must abide by certain requirements designed to protect client funds from the possibility of being lost or misappropriated. This rule was developed for the traditional asset management industry that dealt in instruments with more tangible tracks of physical existence and recording, and thus could pose unique challenges for digital assets often without tangible representation. For example, the digital asset industry's common practice thus far focuses on the safeguarding of private keys.184 Private keys are unique numbers assigned mathematically to digital asset transactions to confirm ownership, raising questions about the nature of "possession" and "control" of a digital asset.185

A March 2019 letter from the SEC to the digital asset industry solicited public input regarding the custody of digital assets.186 In the letter, the SEC summarized a number of policy issues involving the custody of digital assets, including the use of distributed ledger technology (DLT) to record ownership, the use of public and private cryptographic key pairings to transfer digital assets, the ability to restore or recover lost digital assets, the generally anonymous nature of DLT transactions, and the challenges auditors face in examining DLT and digital assets.187 Congressional hearings have also addressed the issue of digital asset custody.188

Nonfinancial Technology Platforms