Financial Inclusion and Credit Access Policy Issues

Access to basic financial products and services is generally considered foundational for households to manage their financial affairs, improve their financial well-being, and graduate to wealth building activities in the future. Financial inclusion in three domains can be particularly important for households:

access to bank and other payment accounts;

access to the credit reporting system; and

access to affordable short-term small-dollar credit.

In the United States, robust consumer credit markets allow most consumers to access financial services and credit products to meet their needs in traditional financial markets. For example, the vast majority of consumers have a bank account, a credit score, a credit card, and other types of credit products.

Some consumers—who tend to be younger adults, low- and moderate-income (LMI) or possess an imperfect credit repayment history—can find gaining access to these banking and credit products and services difficult. Currently, consumers tend to rely on family or community connections to get their first bank account, establish a credit history, and gain access to affordable and safe credit. For those excluded, consumers may find managing their financial lives expensive and difficult.

Different barriers affect different populations. For some younger consumers, a lack of a co-signer might make it more difficult to build a credit report history or a lack of knowledge or familiarity with financial institutions may be a barrier to obtaining a bank account. For consumers living paycheck to paycheck, a bad credit history or a lack of money could serve as barriers to obtaining affordable credit or a bank account. For immigrants, the absence of a credit history in the United States or language differences could be critical access barriers. For consumers who do not have familiarity or access to the internet or mobile phones, a group in which older Americans may be overrepresented, technology can be a barrier to accessing financial products and services.

Financial institutions may find serving these consumers expensive or difficult, given their business model and safety and soundness regulation requirements. For example, lower-balance or less credit-worthy consumers may generally be less profitable for banks to serve. Likewise, some consumers may lack a credit history, making it difficult for lenders to determine their credit risk on a future loan.

New technology has the potential to lower the cost of financial products and expand access to underserved consumers. For example, alternative (nontraditional) data may be able to better price default risk for lenders, which could expand credit access or make credit less expensive for some consumers. In addition, internet-based mobile wallets may provide affordable access to payment services for unbanked consumers. Yet, relevant consumer protection and data security laws and regulations may need to be reconsidered or updated in response to these technological developments. Policymakers debate whether existing regulation can accommodate financial innovation or whether a new regulatory framework is needed.

Given the importance of financial inclusion to financial well-being, and the challenges facing certain segments of the population, this topic may continue to be the subject of congressional interest and legislative proposals. In the 116th Congress, the House Financial Services Committee marked up and ordered reported H.R. 4067, directing the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (CFPB) to report to Congress on these issues. In general, political debates around how to best achieve financial inclusion for underserved consumers relate to whether policy changes could help expand consumers’ affordable access to these financial products and services. Disagreements exist about whether government programs or regulation should be used to directly support financial inclusion or whether laws and regulations make it more difficult for the private sector to create new or existing products targeted at serving underserved consumers.

Financial Inclusion and Credit Access Policy Issues

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Financial Inclusion Overview

- Financial Product Access and Financial Well-Being

- Access to Checking and Other Banking Accounts

- The Unbanked and Underbanked

- Checking and Savings Accounts: Banking Economics

- Banking Account Alternatives

- Access to Emergency Savings and Savings Accounts

- Possible Policy Responses

- Access to the Credit Reporting System

- Credit Invisibles and Unscorables

- Barriers to Entering the Credit System

- Expanding Credit Visibility Policy Issues

- Expanding Use of Currently Reported Products

- Using Alternative Data in Credit Reports

- Access to Affordable Small-Dollar Credit

- Access to Traditional Bank Credit Products

- Credit Alternative Financial Products

- New Technology and Market Developments

- Possible Policy Responses

- Conclusion

Summary

Access to basic financial products and services is generally considered foundational for households to manage their financial affairs, improve their financial well-being, and graduate to wealth building activities in the future. Financial inclusion in three domains can be particularly important for households:

- access to bank and other payment accounts;

- access to the credit reporting system; and

- access to affordable short-term small-dollar credit.

In the United States, robust consumer credit markets allow most consumers to access financial services and credit products to meet their needs in traditional financial markets. For example, the vast majority of consumers have a bank account, a credit score, a credit card, and other types of credit products.

Some consumers—who tend to be younger adults, low- and moderate-income (LMI) or possess an imperfect credit repayment history—can find gaining access to these banking and credit products and services difficult. Currently, consumers tend to rely on family or community connections to get their first bank account, establish a credit history, and gain access to affordable and safe credit. For those excluded, consumers may find managing their financial lives expensive and difficult.

Different barriers affect different populations. For some younger consumers, a lack of a co-signer might make it more difficult to build a credit report history or a lack of knowledge or familiarity with financial institutions may be a barrier to obtaining a bank account. For consumers living paycheck to paycheck, a bad credit history or a lack of money could serve as barriers to obtaining affordable credit or a bank account. For immigrants, the absence of a credit history in the United States or language differences could be critical access barriers. For consumers who do not have familiarity or access to the internet or mobile phones, a group in which older Americans may be overrepresented, technology can be a barrier to accessing financial products and services.

Financial institutions may find serving these consumers expensive or difficult, given their business model and safety and soundness regulation requirements. For example, lower-balance or less credit-worthy consumers may generally be less profitable for banks to serve. Likewise, some consumers may lack a credit history, making it difficult for lenders to determine their credit risk on a future loan.

New technology has the potential to lower the cost of financial products and expand access to underserved consumers. For example, alternative (nontraditional) data may be able to better price default risk for lenders, which could expand credit access or make credit less expensive for some consumers. In addition, internet-based mobile wallets may provide affordable access to payment services for unbanked consumers. Yet, relevant consumer protection and data security laws and regulations may need to be reconsidered or updated in response to these technological developments. Policymakers debate whether existing regulation can accommodate financial innovation or whether a new regulatory framework is needed.

Given the importance of financial inclusion to financial well-being, and the challenges facing certain segments of the population, this topic may continue to be the subject of congressional interest and legislative proposals. In the 116th Congress, the House Financial Services Committee marked up and ordered reported H.R. 4067, directing the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (CFPB) to report to Congress on these issues. In general, political debates around how to best achieve financial inclusion for underserved consumers relate to whether policy changes could help expand consumers' affordable access to these financial products and services. Disagreements exist about whether government programs or regulation should be used to directly support financial inclusion or whether laws and regulations make it more difficult for the private sector to create new or existing products targeted at serving underserved consumers.

Safe and affordable financial services are an important tool for most American households to avoid financial hardship, build assets, and achieve financial security over the course of their lives. In the United States, robust consumer credit markets allow most consumers to access financial services and credit products to meet their needs in traditional financial markets. The vast majority of consumers have, for example, a bank account, a credit score, a credit card, and other types of credit products. However, some consumers—who tend to be younger adults, low- and moderate-income (LMI) consumers or possess imperfect credit repayment history—can find gaining access to these products and services difficult. For those excluded, consumers may find managing their financial lives expensive and difficult.

This report provides an overview on financial inclusion. It then focuses on three areas: (1) access to bank and other payment accounts; (2) inclusion in the credit reporting system; and (3) access to affordable short-term credit. These areas are generally considered foundational for households to successfully manage their financial affairs and graduate to wealth building activities in the future. Wealth building activities—such as access to homeownership, education, and other financial investments—are outside the scope of this report.1

Financial Inclusion Overview

Financial inclusion refers to the idea that individuals "have access to useful and affordable financial products and services that meet their needs—transactions, payments, savings, credit, and insurance—delivered in a responsible and sustainable way."2 Access to financial products allows households to better manage their financial lives, such as storing funds safely, making payments in exchange for goods and services, and coping with unforeseen financial emergencies, such as medical expenses or car or home repairs.

In the United States, most households rely on financial products found at traditional depository intuitions—commercial banks or credit unions. Some households also use financial products and services outside of the banking system, either by choice or due to a lack of access to traditional institutions. While products outside the banking sector may better suit some households' needs, these products might also lack consumer protections or other benefits that traditional financial institutions tend to provide.

Different barriers affect different populations. For some younger consumers, a lack of a co-signer might make it more difficult to build a credit report history or a lack of knowledge or familiarity with financial institutions may be a barrier to obtaining a bank account. For consumers living paycheck to paycheck, a bad credit history or a lack of money could serve as barriers to obtaining affordable credit or a bank account. For immigrants, the absence of a credit history in the United States or language differences could be critical access barriers. For consumers who do not have familiarity or access to the internet or mobile phones, a group in which older Americans may be overrepresented, technology can be a barrier to accessing financial products and services.

Financial Product Access and Financial Well-Being

Some consumers face barriers that make it more difficult for them to access traditional bank products, such as a bank account, enter the credit system, and gain access to financial product and service offerings in traditional financial markets. These barriers can be significant because they may disadvantage these consumers from effectively managing their financial lives and achieving financial well-being, which the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (CFPB) defines as

- 1. having control over day-to-day, month-to-month finances;

- 2. having the ability to absorb a financial shock;

- 3. being on track to meet financial goals; and

- 4. being able to make choices that allow a person to enjoy life.3

Research has examined the factors involved in achieving financial well-being. For example, a CFPB study found that—after controlling for certain economic factors—money management is strongly associated with financial well-being.4 In addition, the CFPB has found that not having a bank account and nonbank transaction product use (e.g., check cashing or money orders) is correlated with lower financial well-being.5 Although nonbank short-term credit is also correlated with lower financial well-being, the effect is not as large as the financial products previously mentioned.6 Lastly, holding liquid savings7 is highly correlated with the CFPB's financial well-being scale.8

Academic research conducted abroad also suggests the importance of access to financial products to improve financial well-being.9 For example, some studies suggest that access to bank accounts can lead to more savings.10 In particular, debit accounts seem to have strong effects, by helping consumers save more by reducing money spent on financial services and monitoring costs.11 Moreover, access to faster and more secure payment services has also been shown to provide significant benefits to consumers, including helping lower-income consumers better handle financial shocks.12 Likewise, inclusion in credit bureaus also have positive effects on consumers by reducing market information asymmetry and allowing some consumers to obtain better terms of credit.13 In contrast, the evidence on the effect of small-dollar short-term credit on individuals' financial well-being is mixed.14

Many Americans have low financial well-being and live paycheck to paycheck. National surveys suggest that about 40% of Americans find "covering expenses and bills in a typical month is somewhat or very difficult,"15 and they could not pay all of their bills on time in the past year.16 In addition, more than 40% of households did not set aside any money in the past year for emergency expenses.17 Therefore, a sizable portion of the adult population report they would have difficulty meeting an unexpected expense. If faced with a $400 unexpected expense, 39% of adults say they would borrow, sell something, or not be able to cover the expense.18 These financial struggles lead to real impacts on the health and wellness of these families; those with low financial well-being are more likely to face material hardship.19

Access to Checking and Other Banking Accounts

The banking sector provides valuable financial services for households that allow them to save, make payments, and access credit.20 Most U.S. consumers choose to open a bank account because it is a safe and secure way to store money.21 For example, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) insures up to $250,000 per depositor against an institution's failure. In addition, consumers gain access to payment services through checking accounts, such as bill pay and paper checks. Frequently, a checking account includes access to a debit card, which increases a consumer's ability to make payment transactions through the account.22 For most consumers, a checking or savings account is less expensive than alternative ways to access these types of services. Some studies suggest that affordable access to payment transactions may be particularly important for consumers to manage their financial lives.23

For most consumers, opening a bank account is relatively easy. Consumers undergo an account verification process and sometimes provide a small initial opening deposit of money into the account.24 Many consumers open their first depository account when they get their first job or start post-secondary education. Checking and savings accounts are often the first relationship that a consumer has with a financial institution, which can later progress into other types of financial products and services, such as loan products or financial investments.

Safe and affordable financial services, especially for families with unpredictable income or expenses, have the potential to help households avoid financial hardship. However, many U.S. households—often those with low incomes, lack of credit histories, or credit histories marked with missed debt payments—do not use banking services.

The Unbanked and Underbanked

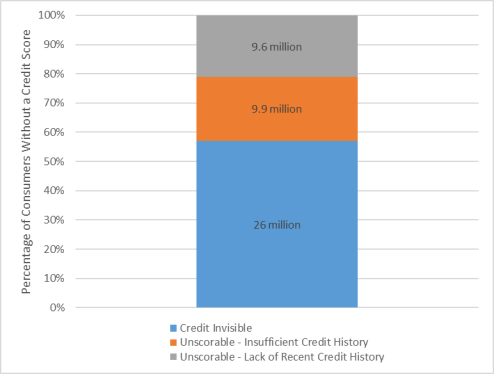

According to the FDIC's 2017 National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, 6.5% of households in the United States were unbanked, meaning that these households do not have a bank account (see Figure 1).25 In addition, another 18.7% of households were underbanked, meaning that although these households had a bank account, they still obtained one or more of certain financial products and services outside of the banking system in the past year.26 These specified nonbank financial products, called alternative financial services, include check cashing, money orders, payday loans, auto title loans, pawn shop loans, refund anticipation loans, and rent-to-own services. Unbanked consumers tend to be lower-income, younger, have less formal education, of a racial or ethnic minority, disabled, and have incomes that varied substantially from month to month compared with the general U.S. population.27

|

Figure 1. Percentage of American Households Unbanked or Underbanked |

|

|

Source: Gerald Apaam et al., FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, October 2018, p. 2, at https://www.fdic.gov/householdsurvey/2017/2017report.pdf. |

Unbanked persons may be electing not to open a bank account due to costs, a lack of trust, or other barriers. According to the survey, these households report that they do not have a bank account because they do not have enough money, do not trust banks, and to avoid high and unpredictable bank fees.28 In addition, for immigrants, the account verification process may be more challenging to complete, and the consumer's country of origin may influence their trust of banks.29

In the past decade or so, the availability of free or low-cost checking accounts has reportedly diminished, and fees associated with checking accounts have grown.30 Some bank accounts require minimum account balances to avoid certain maintenance or service fees. The most common fees that checking account consumers incur are overdraft and nonsufficient fund fees.31 Overdraft services can help consumers pay bills on time, but fees can be costly particularly if used repeatedly. For consumers living paycheck to paycheck, maintaining bank account minimums and avoiding account overdrafts might be difficult, leading to unaffordable account fees. In addition, unpaid fees can lead to involuntary account closures, making it more difficult to obtain a bank account in the future.

Checking and Savings Accounts: Banking Economics

Depository institutions incur expenses to provide checking and savings accounts to consumers.32 In addition to specific account maintenance costs, physical banking branches incur costs to hire staff and maintain retail locations.

To recoup these costs, depository institutions make money from interest rate spreads (i.e., loaning out funds in checking and savings accounts) and account fees. Historically, some banks were willing to lose money on these types of accounts to begin a relationship with a client and later get more profitable business from the client, such as a credit card or mortgage loan.33 In fact, checking and savings accounts data might allow a bank to better underwrite and price loans to a consumer.34 In this way, banks with a checking account relationship with a consumer might be able to provide more attractive loan terms than other banks without this relationship.

Given these dynamics, lower-balance or less credit-worthy consumers may generally be less profitable for banks to serve. Consumers with low checking or savings account balances provide banks minimal funds to lend out and make a profit with. Moreover, less credit-worthy consumers may be less likely to develop into a profitable relationship for the banks if the consumer is not in a position to obtain loans from the bank in the near future. Therefore, bank fees may be seen as the best way for banks to recoup their account costs for these consumers. Because of the way bank fees are structured, consumers with lower balances using checking and savings accounts tend to incur more fees than consumers with higher balances.

Bank access may also have a geographic component, as some observers are concerned that banking deserts—areas without a bank branch nearby—exist in certain communities. Branch offices are still important to many consumers, even as mobile and online banking has become more popular. For example, most banked households visit a bank branch regularly, and one-third of banked households visit 10 or more times in a year.35 However, in the past 10 years, the number of bank branch offices has declined in the United States due to many causes, such as bank consolidations and the rise of online banking.36 Some argue that this has left some communities without any nearby bank branches, making it more difficult to access quality banking services, particularly in lower-income, non-urban areas.37 Yet others argue that banking deserts are not a major issue in the United States because they have been stable over time, and minority areas are less likely to be affected than other areas of the country.38

Banking Account Alternatives

Unbanked households rely on nonbank alternative financial products and services. Both unbanked and underbanked households are more likely to use transaction alternative financial products than credit alternative financial products.39 Transaction alternative financial products include check cashing, money orders, and other nonbank transaction products. In a typical month, unbanked consumers are more likely to use cash, nonbank money orders, and prepaid cards to pay bills and receive income, in contrast to banked consumers, who are most likely to use direct deposit, electronic bank payments, personal checks, debit cards, and credit cards.40

Alternative financial products can sometimes be less expensive, faster, and more convenient for some consumers.41 For example, although check cashing, money orders, and other nonbank transaction products might charge high fees, some consumers may incur higher or less predictable fees with a checking account. In addition, such alternative financial products might allow consumers to access cash more quickly, which might be valuable for consumers with tight budgets and little liquid savings or credit to manage financial shocks or other expenses. Lastly, nonbank stores often are open longer hours including evenings and weekends than banks, which might be more convenient for working households. Moreover, these nonbank stores might also be more likely to cater to a local ethnic or racial community, for example, by hiring staff who speak a native language and live in the local community. Although consumers may find benefits in using alternative financial products substitutes, these products may not always have all of the benefits of bank accounts, such as FDIC insurance or other consumer protections.

General-purpose prepaid cards are another popular alternative to a traditional checking account. Use of prepaid cards is more prevalent among unbanked households—26.9% of unbanked and 14.5% of underbanked households used a prepaid card in the past year.42 These cards can be obtained through a bank, at a retail store, or online, and they can be used in payment networks, such as Visa and MasterCard. General-purpose reloadable prepaid cards generally have features similar to debit and checking accounts, such as the ability to pay bills electronically, get cash at an ATM, make purchases at stores or online, and receive direct deposits.43 However, unlike checking accounts, prepaid card funds are not always federally insured against an institution's failure.44 Prepaid cards often have a monthly maintenance fee and other particular service fees, such as using an ATM or reloading cash. Some banks offer prepaid cards, yet unbanked consumers are much more likely to use a prepaid card from a store or website that is not a bank.45

Nonbank private-sector innovation could also provide more affordable financial products to unbanked and underbanked consumers. Whereas bank products may be expensive to provide to lower-income or less credit-worthy consumers, technology may be able to reduce the cost. For example, internet-based mobile wallets may provide access to payment services for unbanked consumers.46 Alternatives to a banking-based payment system have been proposed or pursued in other countries. For example, the M-pesa, a mobile payment system that does not use banks, has achieved a relatively high level of usage in parts of Africa.47 In addition, new mobile products aim to help consumers manage their money better and save by automating savings behavior.48 Yet, concerns continue to exist for internet-based products around data privacy and cybersecurity issues. Policymakers debate whether existing regulation can accommodate financial innovation or whether a new regulatory framework is needed.49

Access to Emergency Savings and Savings Accounts

Some research suggests that emergency savings is crucial for a household's financial stability. The ability to meet unexpected expenses is particularly important, because within any given year, most households face an unexpected financial shock.50 For example, one study found that families with even a relatively small amount of non-retirement savings (e.g., $250-$750) are less likely in a financial shock to be evicted, miss a housing or utility payment, or receive means-tested public benefits.51 These findings are consistent throughout the income spectrum, not only for lower-income families.52

One barrier for building emergency savings may include not having a separate account dedicated to saving. For example, money in a transaction account intended for emergencies can be vulnerable to unintentional overspending.53 Although almost all banked households report having a checking account, roughly a quarter do not have a savings account.54 These households tend to be lower-income and living in rural areas and are more likely to be an ethnic or racial minority or working-age disabled compared with the U.S. population.55 Moreover, unbanked households are much less likely to report saving for unexpected expenses and emergencies (17.4%) than banked households (61.6%).56 Whereas most households save using a checking or savings account, most unbanked households save at home or with family or friends.57 In addition, saving with a prepaid card is much more common for unbanked households.58 Some recent research suggests that saving, not only through a savings account, but also through savings wallets on prepaid cards, can help consumers avoid high-cost credit and alternative financial services.59

Possible Policy Responses

In regard to accessing financial products and services that help consumers manage their finances and achieve financial success, some research suggests that consumers may particularly benefit from (1) access to affordable electronic payment system services, for example, through a traditional bank account; and (2) a safe way to accumulate and hold emergency savings. The government, the private sector, and the nonprofit sector all may be in a position to help increase access to these types of financial products for the underserved.

Some propose changes to bank regulation to try to increase access to bank accounts. For example, the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) encourages banking institutions to meet the credit needs of the areas they serve, particularly in LMI neighborhoods.60 Banks receive "CRA credits" for qualifying activities, such as mortgage, consumer, and business loans. Currently, providing bank accounts to LMI consumers or neighborhoods is not included in the calculation. Bank regulators are considering updating the CRA, and they recently received public comments on reforming implementation of the law.61 The Federal Reserve indicated that it is considering, due to public feedback, expanding the list of products and services that are eligible for CRA credits, including "financial services and products aimed at helping consumers get on a healthier financial path," such as affordable checking and savings accounts for LMI consumers.62 Bank regulators may need to balance expanding CRA credit for these products with the CRA's statutory purpose, which was focused on encouraging bank lending activities to meet local communities' credit needs.

Payment system improvements, either by the government or the private sector, may also have the potential to improve welfare for unbanked or underbanked consumers. Many of these consumers choose alternative financial payment products such as check cashers to access their funds quickly.63 These consumers might not require such alternative services if bank payment systems operated faster than they normally do. Both the private sector and the government are currently working on initiatives to make the bank payment system faster.64 For example, the Federal Reserve plans to introduce a real time payment system called FedNow in 2023 or 2024, which would allow consumers access to funds quickly after initiating the transfer.65 Faster payments may help some consumers avoid overdraft fees on checking accounts.66 However, some payments that households make would also be cleared faster—debiting their accounts more quickly—which could be disadvantageous to some of these households compared with the current system.

Other policy proposals include the government directly providing accounts to retail customers. For example, offering banking services through postal offices67 or providing banking services online to the public through the Federal Reserve, which already provides accounts to banks.68 Opposition to these proposals often centers on the appropriate role for the government. Some argue that the government should not be competing with the private sector to provide these services to consumers, especially in the competitive banking market.69 Moreover, government bank accounts may not attract consumer demand. For example, the Treasury Department's myRA account program—which provided workers without a work retirement account a vehicle for retirement savings—closed after about three years, in part due to lack of participation.70

Financial education programs or outreach initiatives coordinated by the government, nonprofit organizations, and financial institutions could support financial inclusion as well.71 Given the importance of emergency savings, in 2019, CFPB Director Kraninger announced that the CFPB wants to focus on increasing consumer savings, through financial education initiatives72 and joint research projects with the financial industry.73 In addition, the "Bank On" movement—a coalition between city, state, and federal government agencies, community organizations, financial institutions, and others—aims to encourage unbanked consumers to open and use bank accounts. Bank accounts associated with the movement must have no overdraft fees, charge a minimal amount of monthly fees, have deposits that are federally insured, and offer traditional banking services, such as direct deposit, debit or prepaid cards, and online banking.74 Nearly 3 million accounts have been opened through the movement, generally to new bank customers, and consumers tend to actively use these accounts.75

This topic may continue to be the subject of congressional interest and legislative proposals. In the 116th Congress, the House Financial Services Committee marked up and ordered reported H.R. 4067, directing the CFPB to report to Congress on unbanked, underbanked, and underserved consumers.76 In addition, other legislation introduced proposes establishing an office within the CFPB to work on unbanked and underbanked issues (H.R. 1285) and proposes developing short-term non-retirement savings accounts for consumers with their employers automatically deducting from their paychecks (S. 1019, H.R. 2120, S. 1053) or using their tax refund to save (H.R. 2112, S. 1018 ).

Access to the Credit Reporting System

The credit reporting industry collects information on consumers and uses it to estimate the probability of future financial behaviors, such as successfully repaying a loan or defaulting on it. The information collected has largely related to consumers' past financial performance and repayment history on traditional credit products. Consumer files generally do not contain information on consumer income or assets or on alternative financial services. Credit bureaus collect and store payment data reported to them by financial firms, and they or other credit scoring companies use this data to estimate individual consumers' creditworthiness, generally expressed as a numerical "score." The three largest credit bureaus—Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion—provide credit reports nationwide that include repayment histories.77 Credit reports generally may not include information on items such as race or ethnicity, religious or political preference, or medical history.78

This industry significantly affects consumer access to financial products, because lenders and other financial firms use consumer data when deciding whether to provide credit or other products to an individual and under what terms. Consumers who find it challenging to enter the traditional credit reporting system face challenges accessing many consumer credit products, such as mortgages or credit cards, because creditors are unable to assess the consumer's credit worthiness. This section examines some consumer credit reporting issues and related developments and policy issues.

Credit Invisibles and Unscorables

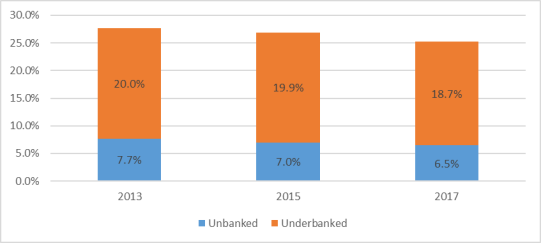

According to the CFPB, credit scores cannot be generated for approximately 20% of the U.S. population due to their limited credit histories.79 The CFPB categorizes consumers with limited credit histories into several groups. One category of consumers, referred to as credit invisibles, have no credit record at the three nationwide credit reporting agencies and, thus, do not exist for the purposes of credit reporting. Credit invisibles represents 11% of the U.S. adult population, or 26 million consumers (see Figure 2). Another category of consumers have a credit record and thus exist, but they cannot be scored or are considered unscorable. Unscorable consumers either have insufficient (short) histories or stale (outdated) histories. The insufficient and stale unscored groups, each containing more than 9 million individuals, collectively represent 8.3% of the U.S. adult population, or approximately 19 million consumers.80

Limited credit history is correlated with age, income, race, and ethnicity. Many consumers that are credit invisible or unscorable are young. For example, 40% of credit invisibles are under 25 years old.81 Moreover, consumers who live in lower-income neighborhoods or are black or Hispanic are also disproportionately credit invisible or unscorable compared with the U.S. population.82

Barriers to Entering the Credit System

Most young adults transition into the credit reporting system in their early twenties—80% of consumers transition out of credit invisibility before age 25 and 90% before age 30.83 For young consumers, the most common ways to become credit visible is through credit cards, student loans, and piggybacking (i.e., becoming a joint account holder or authorized user on another person's account, such as a parent's account).84

Young adults in LMI neighborhoods tend to make the transition to credit visibility at older ages than young adults in higher-income neighborhoods. In urban areas, consumers over 25 years old from LMI neighborhoods have higher rates of credit invisibility than those in middle and upper income areas.85 In addition, the highest rates of credit invisibility for consumers over 25 years old are in rural areas, and these rates do not vary much based on neighborhood income.86 Credit invisible consumers in LMI and rural areas are less likely to enter the credit bureaus through a credit card than credit invisible consumers in other parts of the country,87 possibly because piggybacking is notably less common in LMI communities.88 Moreover, using student loans to become credit visible is also less common in LMI areas.89

Recent immigrants also have trouble entering the credit system when they come to the United States. Existing credit history from other countries does not transfer to the U.S. system. In addition, immigrants' alternative forms of identification, such as the Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITINs) might not be accepted by some financial services providers.90

Expanding Credit Visibility Policy Issues

Consumers without a credit record have trouble accessing credit, but without access to credit, a consumer cannot establish a credit record. In general, there are two ways that policymakers tend to approach this issue, either by (1) expanding uptake of financial products reported in the current system or (2) expanding the types of information in the credit reporting system using alternative data.

Expanding Use of Currently Reported Products

The first approach often focuses on financial education and entry-level products. Financial education and partnerships between financial services providers and nonprofit groups may help consumers learn how credit reporting works, develop a credit history, and become scorable.91 For example, financial wellness programs at workplaces are a growing way to deliver these types of programs.92 Yet financial education, coaching, and counseling can be expensive and difficult to provide to consumers.93

On the financial product side, tensions exist between expanding credit access to build a credit history and upholding consumer protection. For example, credit cards are the most common first product reported to credit bureaus, yet consumer protection regulations, such as the CARD Act of 2009,94 reduce young consumers' access to credit cards.95 Stakeholders believe that large financial services providers should develop entry-level credit products that are profitable and sustainable, without sacrificing consumer protections.96 For example, secured credit cards—which are "secured" by a consumer deposit, so the issuer faces little risk of default—can help establish a credit history, but currently, are less likely to move consumers to credit visibility than unsecured (regular) credit cards.97 Some consumer advocates believe that the security deposit is an obstacle for lower-income consumers.98 This issue epitomizes the difficulty in developing credit-building financial products for unscorable consumers that are safe, accessible, and prudent for the financial institution.

Using Alternative Data in Credit Reports

Alternative data generally refers to data that the national consumer reporting agencies do not traditionally use (e.g., information other than traditional financial institution credit repayments) to calculate a credit score. It can include both financial and nonfinancial data. In a 2017 Request for Information, the CFPB included examples of alternative data, such as payments on telecommunications; rent or utilities; checking account transaction information; educational or occupational attainment; how consumers shop, browse, or use devices; and social media information.99

Alternative data could potentially be used to expand access to credit for current credit invisible or unscorable consumers, but it also could create data security risks or consumer protection violations. Alternative data used in credit scoring could increase accuracy, visibility, and scorability in credit reporting by including additional information beyond that which is traditionally used. The ability to calculate scores for the credit invisible or unscoreable consumer groups could allow lenders using these scores to better determine the creditworthiness of people in these groups. Arguably, this would increase access to—and lower the cost of—credit for some credit invisible or unscorable individuals, as lenders using alternative data are able to find new creditworthy consumers. However, in cases where the alternative data includes negative or derogatory information, it has the potential to harm some consumers' existing credit scores. Some prospective borrowers may be unaware that alternative data has been used in credit decisions, raising privacy and consumer protection concerns.100 Moreover, alternative data may pose fair lending risks if the data used are correlated with characteristics, such as race or ethnicity.101

Using alternative data for credit reporting raises regulatory compliance questions, which may be why adaption of alternative data in the credit reporting system is currently limited. The main statute regulating the credit reporting industry is the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA),102 which establishes consumers' rights in relation to their credit reports, as well as permissible uses of credit reports. It also imposes certain responsibilities on those who collect, furnish, and use the information contained in consumers' credit reports. Alternative data providers outside of the traditional consumer credit industry may find FCRA data furnishing requirements burdensome. Some alternative data may have accuracy issues, and managing consumer disputes requires time and resources. These regulations may discourage some organizations from furnishing alternative data, even if the data could help some consumers become scorable or increase their credit scores. In an effort to address such concerns, many consumer data industry firms use alternative data only when consumers' opt-in.103

Using alternative data for credit reporting may continue to be the subject of congressional interest and legislative proposals. In the 116th Congress, the House Financial Services Committee marked up and ordered reported H.R. 3629, which among other things directs the CFPB to report to Congress on the impact of using nontraditional data on credit scoring.104 In addition, other legislation introduced allows types of alternative data to be furnished to the credit bureaus (S. 1828, H.R. 4231).

Access to Affordable Small-Dollar Credit

Short-term, small-dollar loans are consumer loans with relatively low initial principal amounts, often less than $1,000, with relatively short repayment periods, generally for a small number of weeks or months. Small-dollar loans can be offered in various forms and by both traditional financial institutions (e.g., banks) and alternative financial services providers (e.g., payday lenders).

Many U.S. consumers do not have access to affordable small-dollar credit; often for these consumers, small-dollar credit is either expensive or difficult to access. The extent to which borrowers' financial situations would be harmed by using expensive credit or having limited access to credit is widely debated. Credit is an important way households pay for unexpected expenses and compensate for emergencies, such as a car or home repair, a medical expense, or a pay cut. Credit that can be paid back flexibly is particularly valued by consumers, especially those living paycheck to paycheck.105 Research suggests that access to this type of short-term credit can help households during short-term emergencies, yet unsustainable debt can harm households.106 Consumer groups often raise concerns regarding the affordability of small-dollar loans. Some borrowers may fall into debt traps, situations where borrowers repeatedly roll over existing loans into new loans and find it difficult to repay outstanding balances. Regulations aimed at reducing costs for borrowers may result in higher costs for lenders, possibly limiting or reducing credit availability for financially distressed individuals.107

This section focuses on expanding access to affordable small-dollar credit. Policymakers continue to be interested in ways to increase access to affordable credit because it is an important step in achieving financial stability.

Access to Traditional Bank Credit Products

About 80% of U.S. households have access to bank or traditional financial institution credit products, such as a general or store credit card, a mortgage, an auto loan, a student loan, or a bank personal loan.108 Credit cards are the most common form of credit, and they are what most households use for small-dollar credit needs.109 In general, banks require a credit score or other information about the consumer to prudently underwrite a loan. Scorable and credit-worthy consumers are in a position to gain access to credit from traditional sources. Financial institutions also sometimes provide consumer loans to existing customers, even if the borrower lacks a credit score (e.g., a consumer with a checking account who is a student or young worker). Some institutions make these loans to build long-term relationships.

The remaining 20% of households do not have access to any traditional bank credit products,110 generally because they are either unscorable or have a blemished credit history. They are more likely to be unbanked, low-income, and minority households.111 Not having access to traditional bank credit is also correlated with age, formal education, disability status, and being a foreign-born noncitizen.112 According to an FDIC estimate, 12.9% of households had unmet demand for bank small-dollar credit.113 Of these households interested in bank credit, over three-quarters were current on bills in the last year, suggesting these households might be creditworthy.114

Policymakers often face a trade-off between consumer protection and access to credit when regulating the banking sector. Consumer protection laws at the state and federal levels often limit the profitability of small-dollar, short-term loans. For example, legislation such as the CARD Act of 2009 placed restrictions on subprime credit card lending.115 Small-dollar, short-term loans can be expensive for banks to provide. Although many of the underwriting and servicing costs are somewhat fixed regardless of size, smaller loans earn less total interest income, making them more likely to be unprofitable.116 Moreover, excluded consumers often are either unscorable or have a blemished credit history, making it difficult for banks to prudently underwrite loans for these consumers. In addition, banks face various regulatory restrictions on their permissible activities, in contrast to nonbanks. For these reasons, many banks choose not to offer credit products to some consumers.

Nevertheless, banks have demonstrated interest in providing certain small-dollar financial services such as direct deposit advances, subprime credit cards, and overdraft protection services. In these cases, banks may face regulatory disincentives to providing these services, because bank regulators and legislators have sometimes demonstrated concerns about banks providing these products. For example, before 2013, some banks offered deposit advance products to consumers with bank accounts, which were short-term loans paid back automatically out of the borrower's next qualifying electronic deposit.117 Research findings from the CFPB suggest that although deposit advance was designed to be a short-term product, many consumers used it intensively. In the CFPB's sample, the median user was in debt for 31% of the year.118 Because of this sustained use and concerns about consumer default risk, in 2013, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), FDIC, and Federal Reserve issued supervisory guidance, advising banks to make sure deposit advance products complied with consumer protection and safety and soundness regulations.119 Many banks subsequently discontinued offering deposit advances.120

At the same time, regulators and policymakers have implemented policies aimed at increasing credit availability. Regulation implemented pursuant to the CRA (the 1977 law discussed in the "Access to Checking and Other Banking Accounts" section above) encourages banking institutions to meet the credit needs of consumers in the areas they serve, particularly in LMI neighborhoods that tend to include these excluded consumers. However, the CRA applies only to individuals with an established relationship with a bank, excluding unbanked consumers in an area. Likewise, many small-dollar loan products may not be considered qualifying activities. Moreover, the CRA does not encourage banks from engaging in unprofitable activities, so the incentives it creates might be limited.

Credit Alternative Financial Products

Credit alternative financial products include payday loans, pawn shop loans, auto title loans, and other types of loan products from nonbank providers. According to the FDIC, 6.9% of American households used a credit alternative financial service in 2017.121 Households that rely on credit alternative financial services are more likely to be lower-income, younger, and a racial or ethnic minority compared with the general U.S. population.122

Some argue that credit alternative financial products are expensive and are more likely than bank products to lead to debt traps. Bank small-dollar credit may be less expensive for prime borrowers with credit histories or relationships with banks. For other consumers, credit alternative financial products might better serve their needs due to fee structure or less stringent underwriting. Yet, some of these consumers may not have access to bank products and thus rely on credit alternative financial products for their credit needs.

New Technology and Market Developments

New technology may have the potential to help expand access to affordable credit to underserved consumers. For example, new nonbank digital or mobile-based financial products may lower the cost to provide small-dollar loans, making it easier to expand credit access to the underserved. Other nonbank products try to reduce default risk, for example, through employer-based lending models, to expand access to credit for more consumers.123

In addition, some lenders choose not to rely solely on the credit reporting system, and instead use alternative data directly to make credit decisions. New products that use alternative data on prospective borrowers—either publicly or with the borrower's permission—may be able to better price lenders' default risk, which could expand credit access or make credit cheaper for some consumers.124 Recent findings suggest that some types of alternative data—such as education, employment, and cash-flow information—might be promising ways to expand access to credit. For example, initial results from the Upstart Network's credit model, which uses alternative data to make credit and pricing decisions, shows that the model expands the number of consumers approved for credit, lowers the rate consumers pay for credit on average, and does not increase disparities based on race, ethnicity, gender, or age.125 Moreover, another recent study suggests that cash-flow data may more accurately predict creditworthiness, and its use would expand credit access to more borrowers, while meeting fair lending rules.126

One market segment is particularly illustrative of this practice. With the proliferation of internet access and data availability, some new lenders—often referred to as marketplace lenders or fintech lenders—rely on online platforms and frequently underwrite loans using alternative data. Although fintech lending remains a small part of the consumer lending market, it has grown rapidly in recent years. According to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), "in 2017, personal loans provided by these lenders totaled about $17.7 billion, up from about $2.5 billion in 2013."127 In addition, incumbent bank and nonbank lenders have adopted certain of these technologies and practices to varying degrees, and in some cases have partnered or contracted with fintech companies to build or run online, algorithmic platforms.

Yet, despite the potential of new technology in small-dollar lending markets, these technologies also create risks for consumers. For example, new digital technology exposes consumers to data security risks. In addition, lenders' alternative data used to make credit decisions could result in disparate impacts or other consumer protection violations.

Possible Policy Responses

Policymakers and observers will likely continue to explore ways to make affordable and safe credit accessible to a greater portion of the population (in addition to including more people in the credit reporting system, as discussed in a previous section of the report).

Changes to bank regulation could encourage more banking institutions to increase access to credit to underserved consumers. For example, some question the effectiveness of how the CRA is currently implemented, particularly with regard to short-term, small-dollar loans. As bank regulators consider updating the CRA, the Federal Reserve said that another area they are considering changing, due to public feedback, is expanding CRA-eligible products and services, such as payday loan alternatives and other small-dollar short-term loans for LMI consumers.128 Yet, as stated earlier in the report, bank regulators need to balance new CRA criteria with federal prudential regulations for safety and soundness, which requires banks to prudently undertake CRA-qualified activities and not engage in activities that are likely unprofitable to the bank.

Reducing regulatory barriers may also allow more banking institutions to increase access to credit to underserved consumers. Financial regulators have taken recent steps to encourage banks to re-enter the small-dollar lending market. In October 2017, the OCC rescinded the 2013 guidance, and in May 2018 issued a new bulletin to encourage their banks to enter this market.129 In November 2018, the FDIC solicited advice about how to encourage more banks to offer small-dollar credit products.130 It is unclear whether these efforts will encourage banks to enter the small-dollar market with a product similar to deposit advance.

In terms of using new technology and alternative data in consumer lending, questions exist about how to comply with fair lending and other consumer protection regulations. 131 Currently, the federal financial regulators are monitoring these new technologies, but they have not provided detailed guidance.132 In February 2017, the CFPB requested information from the public about the use of alternative data and modeling techniques in the credit process.133 Information from this request led the CFPB to outline principles for consumer-authorized financial data sharing and aggregation in October 2017.134 These nine principles include, among other things, consumer access and usability, consumer control and informed consent, and data security and accuracy.135 According to the GAO, both fintech lenders and federally regulated banks that work with fintech lenders reported that additional regulatory clarification would be helpful.136 Therefore, the GAO recommended "that the CFPB and the federal banking regulators communicate in writing to fintech lenders and banks that partner with fintech lenders, respectively, on the appropriate use of alternative data in the underwriting process." 137

Lastly, some advocate for the federal government providing small-dollar short-term loans to consumers directly if the private sector leaves some underserved, for example, through postal offices.138 Yet, providing credit to consumers is more risky than providing bank accounts or other banking services because some consumers will default on their loans. Opponents of the government directly providing consumer loans often centers on concerns about the federal government managing the credit risks it would undertake.139 These opponents generally argue that the private sector is in a more appropriate position to take these risks.

Conclusion

Access to bank and other payment accounts, the credit reporting system, and affordable short-term small-dollar credit are generally considered foundational for households to manage their financial affairs, improve their financial well-being, and graduate to wealth building activities in the future. In the United States, robust consumer credit markets allow most consumers to access financial services and credit products to meet their needs in traditional financial markets. Yet currently, consumers tend to rely on family or community connections to get their first bank account, establish a credit history, and gain access to affordable and safe credit.

Given the importance of financial inclusion to financial well-being, and the challenges facing certain segments of the population, this topic is likely to continue to be the subject of congressional interest and legislative proposals. As markets develop and technology continues to change, new financial products have the potential to lower costs and expand access. Yet, as this report described, relevant laws and regulations may need to be reconsidered or updated in response to these technological developments. Moreover, policymakers may consider whether other policy changes could help expand consumers' affordable access to these financial products and services. Disagreements will continue to exist around whether government programs or regulation should be used to directly support financial inclusion or whether laws and regulations make it more difficult for the private sector to create new or existing products targeted at underserved consumers.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

For more information on homeownership, see CRS Report R42995, An Overview of the Housing Finance System in the United States, by N. Eric Weiss and Katie Jones. For more information on education finance, see CRS Report R43351, The Higher Education Act (HEA): A Primer, by Alexandra Hegji. For more information on saving and investing for retirement, see CRS Report RL34397, Traditional and Roth Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs): A Primer, by John J. Topoleski and CRS Report R40707, 401(k) Plans and Retirement Savings: Issues for Congress, by John J. Topoleski. |

| 2. |

The World Bank's definition of financial inclusion, see The World Bank, "Financial Inclusion," October 2, 2018, at https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/financialinclusion/overview. |

| 3. |

Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (CFPB), Financial Well-being: The Goal of Financial Education, January 2015, p. 5, at https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201501_cfpb_report_financial-well-being.pdf. (Hereinafter CFPB, Financial Well-being in America.) |

| 4. |

CFPB, Pathways to Financial Well-Being: The Role of Financial Capability, September 2018, pp. 7-11, at https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/bcfp_financial-well-being_pathways-role-financial-capability_research-brief.pdf. |

| 5. |

CFPB, Financial Well-being in America, September 2017, p. 57, at https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/201709_cfpb_financial-well-being-in-America.pdf. |

| 6. |

CFPB, Financial Well-being in America, p. 57. |

| 7. |

Liquid savings are financial assets, such as a savings account, from which the household can easily access funds. In contrast, illiquid wealth includes valuable items, such as a car or home, that a household owns. For more information on U.S. households' balance sheet, see CRS Report R45813, An Overview of Consumer Finance and Policy Issues, by Cheryl R. Cooper. |

| 8. |

CFPB, Financial Well-being in America, pp. 49-53. |

| 9. |

Yet, because these studies were generally conducted abroad, it is possible that these effects may differ in the U.S. context. |

| 10. |

Dean Karlan et al., Research and Impacts of Digital Financial Services, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Working Paper no. 22633, September 2016, p.2. (Hereinafter Karlan etal., Research and Impacts of Digital Financial Services.) |

| 11. |

Pierre Bachas et al., How Debit Cards Enable the Poor to Save More, NBER, Working Paper no. 23252, October 2018. |

| 12. |

Financial shocks are unexpected expenses, such as a car or home repair, a medical expense, or a pay cut; Karlan et al., Research and Impacts of Digital Financial Services, p.3. |

| 13. |

Karlan et al., Research and Impacts of Digital Financial Services, pp.4-5. |

| 14. |

Karlan et al., Research and Impacts of Digital Financial Services, p.1. |

| 15. |

CFPB, Financial Well-being in America, p. 72. |

| 16. |

Financial Health Network (formerly CFSI), U.S. Financial Health Pulse: 2018 Baseline Survey Results, May 2019, p.4, at https://finhealthnetwork.org/research/u-s-financial-health-pulse-2018-baseline-survey-results/. |

| 17. |

Gerald Apaam et al., FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, October 2018, p. 43, at https://www.fdic.gov/householdsurvey/2017/2017report.pdf. (Hereinafter Apaam et al., FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households.) |

| 18. |

Federal Reserve, Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2018, May 2019, p. 2, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2018-report-economic-well-being-us-households-201905.pdf. |

| 19. |

CFPB, Financial Well-being in America, p. 6. |

| 20. |

The banking sector includes both banks and credit unions. |

| 21. |

In this report, bank accounts refer to checking, savings, and other accounts at all depository institutions, including banks and credit unions. |

| 22. |

For more information on checking accounts, see CRS Report R43364, Recent Trends in Consumer Retail Payment Services Delivered by Depository Institutions, by Darryl E. Getter. |

| 23. |

CFPB, Financial Well-being in America, p. 57; and Karlan et al., Research and Impacts of Digital Financial Services, p. 3. |

| 24. |

For a bank account, the initial opening deposit is usually under $100. Some banks do not require an initial deposit. For more information, see Melissa Lambarena, What You Need to Open a Bank Account, NerdWallet, October 30, 2018, at https://www.nerdwallet.com/blog/banking/how-to-open-a-bank-account-what-you-need/. |

| 25. |

Apaam et al., FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, p. 1. |

| 26. |

Apaam et al., FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, p. 1. |

| 27. |

Apaam et al., FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, p. 19. |

| 28. |

Apaam et al., FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, p.4. |

| 29. |

Vanessa Gail Perry, "Acculturation, Microculture and Banking: An Analysis of Hispanic Consumers in the USA," Journal of Services Marketing, vol. 22, no. 6 (2008), p. 427. |

| 30. |

CFPB, CFPB Study of Overdraft Programs: A White Paper of Initial Data Findings, June 2013, pp. 15-17, at https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201306_cfpb_whitepaper_overdraft-practices.pdf; and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), FDIC Quarterly Banking Profile: Quarterly Income Time-Series Data, 2019, at https://www.fdic.gov/bank/analytical/qbp/. |

| 31. |

Trevor Bakker et al., Data Point: Checking Account Overdraft, CFPB, July 2014, p. 5, at https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201407_cfpb_report_data-point_overdrafts.pdf. |

| 32. |

Depository institutions refer to both banks and credit unions. |

| 33. |

Robert Barba, "The True Cost of Free Checking," Bankrate, March 7, 2018, at https://www.bankrate.com/banking/checking/free-checking-is-not-really-free/. |

| 34. |

Loretta J. Mester, Leonard I. Nakamura, and Micheline Renault, "Checking Accounts and Bank Monitoring," FRB of Philadelphia Working Paper No. 01-3, March 2001; Lars Norden and Martin Weber, "Credit Line Usage, Checking Account Activity, and Default Risk of Bank Borrowers," Review of Financial Studies, vol. 23 (2010), pp. 3665-3699. |

| 35. |

Apaam et al., FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, p. 14. |

| 36. |

Although some traditional banks have tried to compete in the digital banking space to provide cheaper products to consumers, banks have not always been successful with the online product channel. See Penny Crosman, "Where did JPMorgan Chase's Finn experiment go wrong?" American Banker, June 6, 2019. |

| 37. |

Drew Dahl and Michelle Franke, "Banking Deserts" Become a Concern as Branches Dry Up, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, July 25, 2017, at https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/second-quarter-2017/banking-deserts-become-a-concern-as-branches-dry-up; Donald Morgan, Maxim Pinkovskiy, and Bryan Yang, Banking Deserts, Branch Closings, and Soft Information, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, March 7, 2016, at https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2016/03/banking-deserts-branch-closings-and-soft-information.html; and Francisco Covas, Some Facts About Bank Branches and LMI Customers, Bank Policy Institute, April 4, 2019, at https://bpi.com/notes-papers-presentations/some-facts-about-bank-branches-and-lmi-customers/. |

| 38. |

Donald Morgan, Maxim Pinkovskiy, and Bryan Yang, Banking Deserts, Branch Closings, and Soft Information, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, March 7, 2016, at https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2016/03/banking-deserts-branch-closings-and-soft-information.html; and Francisco Covas, Some Facts About Bank Branches and LMI Customers, Bank Policy Institute, April 4, 2019, at https://bpi.com/notes-papers-presentations/some-facts-about-bank-branches-and-lmi-customers/. |

| 39. |

Apaam et al., FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, p. 8. |

| 40. |

Apaam et al., FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, p. 12. |

| 41. |

Lisa Servon, The Unbanking of America: How the New Middle Class Survives (Mariner Books, 2017). |

| 42. |

Apaam et al., FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, p. 7. |

| 43. |

Apaam et al., FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, p. 34. |

| 44. |

For more information on prepaid cards, see CRS Report R43364, Recent Trends in Consumer Retail Payment Services Delivered by Depository Institutions, by Darryl E. Getter. |

| 45. |

Apaam et al., FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, p. 38. |

| 46. |

For more information, see CFPB, Mobile Financial Services: A Summary of Comments from the Public on Opportunities, Challenges, and Risks for the Underserved, November 2015, p.7, at https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201511_cfpb_mobile-financial-services.pdf. |

| 47. |

For more information on M-pesa, see "Why does Kenya lead the World in Mobile Money?" The Economist, March 2, 2015. |

| 48. |

For more information on popular savings apps, see Melanie Lockert, The Best Money Apps for Saving and Investing, Credit Karma, January 24, 2018, at https://www.creditkarma.com/advice/i/best-money-saving-apps/. |

| 49. |

For more information, see CRS In Focus IF11195, Financial Innovation: Reducing Fintech Regulatory Uncertainty, by David W. Perkins, Cheryl R. Cooper, and Eva Su. |

| 50. |

According to a Pew Charitable Trusts survey, 60% of households face a financial shock within 12 months, such as a major car or home repair, a trip to the hospital, a pay cut, or another large expense. The median cost of a household's most expensive shock during a year is $2,000. For more information, see The Pew Charitable Trusts, How Do Families Cope With Financial Shocks? The Role of Emergency Savings in Family Financial Security, October 2015, pp. 4-5, at https://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2015/10/emergency-savings-report-1_artfinal.pdf. |

| 51. |

Signe-Mary McKernan et al., Thriving Residents, Thriving Cities: Family Financial Security Matters for Cities, The Urban Institute, April 2016, p. 2, at https://www.urban.org/research/publication/thriving-residents-thriving-cities-family-financial-security-matters-cities. |

| 52. |

McKernan et al., Thriving Residents, Thriving Cities, pp. 6-9. |

| 53. |

For more information on consumer financial biases, see CRS Report R45813, An Overview of Consumer Finance and Policy Issues, by Cheryl R. Cooper. |

| 54. |

Apaam et al., FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, p. 4. |

| 55. |

Apaam et al., FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, p. 44. |

| 56. |

Apaam et al., FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, p. 8. |

| 57. |

Apaam et al., FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, p. 9. |

| 58. |

Apaam et al., FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households, p. 9. |

| 59. |

Cheryl Cooper et al., Tools for Saving: Using Prepaid Accounts to Set Aside Funds, CFPB, September 2016, at https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/092016_cfpb_ToolsForSavingPrepaidAccounts.pdf; Mathieu Despard et al., "Effects of a Tax-Time Savings Intervention on Use of Alternative Financial Services among Lower-Income Households," Journal of Consumer Affairs, vol. 51, no. 2 (2017); and Gregory Mills et al., "First‐Year Impacts on Savings and Economic Well‐Being from the Assets for Independence Program Randomized Evaluation," Journal of Consumer Affairs, vol. 53, no. 1 (Summer 2019). |

| 60. |

P.L. 95-128; for more information on the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), see CRS Report R43661, The Effectiveness of the Community Reinvestment Act, by Darryl E. Getter. |

| 61. |

On April 3, 2018, the U.S. Department of the Treasury (Treasury) released recommendations to modernize CRA in a memorandum to the federal banking regulators (Office of the Comptroller of the Currency [OCC], FCIC, and the Federal Reserve). One of their recommendations to modernize the CRA is to expand the types of loans, investments, and services that qualify for CRA credit. For more information, see U.S. Department of the Treasury, "Memorandum for the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation," April 3, 2018, at https://home.treasury.gov/sites/default/files/2018-04/4-3-18%20CRA%20memo.pdf. |

| 62. |

Federal Reserve, Perspectives from Main Street: Stakeholder Feedback on Modernizing the Community Reinvestment Act, June 2019, p. 9, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/stakeholder-feedback-on-modernizing-the-community-reinvestment-act-201906.pdf. For more information on the potential to encourage banks to provide basic bank services and small-dollar, nonmortgage loans to low- and moderate-income consumers, see U.S. Government Accountability Office, Community Reinvestment Act: Options for Treasury to Consider to Encourage Services and Small-Dollar Loans When Reviewing Framework, GAO-18-244, February 2018, at https://www.gao.gov/assets/700/690050.pdf. |

| 63. |

Aaron Klein, The Fastest Way to Address Income Inequality? Implement a Real Time Payment System, Brookings Institution, January 2, 2019, at https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-fastest-way-to-address-income-inequality-implement-a-real-time-payment-system. |

| 64. |

Several private-sector initiatives are underway to implement faster payments. For an overview, see Nacha, Faster Payments 101, at https://www.nacha.org/system/files/2019-05/FasterPayments101_2019.pdf. Notably, the Clearing House introduced its real time payment network (with real-time settlement) in November 2017; according to the Clearing House, it currently "reaches 50% of U.S. transaction accounts, and is on track to reach nearly all U.S. accounts in the next several years." For more information, see The Clearing House, The RTP Network: For All Financial Institutions, webpage, at https://www.theclearinghouse.org/payment-systems/rtp/institution. |

| 65. |

The Federal Reserve stated, "it will likely take longer for any service, whether the FedNow Service or a private-sector service, to achieve nationwide reach regardless of when the service is initially available." Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, Federal Reserve Actions to Support Interbank Settlement of Faster Payments, August 5, 2019, Docket No. OP-1670, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/files/other20190805a1.pdf. |

| 66. |

CFPB, Consumer Voices on Overdraft Programs, November 2017, pp. 16-19, at https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_consumer-voices-on-overdraft-programs_report_112017.pdf. |

| 67. |

Mehrsa Baradaran, "It's Time for Postal Banking," Harvard Law Review Forum, vol. 127 (February 2014), pp. 165-175; and Mehrsa Baradaran, How the Other Half Banks: Exclusion, Exploitation, and the Threat to Democracy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015). |

| 68. |

Morgan Ricks, John Crawford, and Lev Menand, "A Public Option for Bank Accounts (or Central Banking for All)," Vanderbilt Law Research Paper 18-33 & UC Hastings Research Paper No. 287, January 26, 2019. |

| 69. |

Eric Grover, "Return to Sender: Here's What's Wrong with Postal Banking," American Banker, May 17, 2018. |

| 70. |

Katie Lobosco, "Treasury Ends the MyRA, Obama's Retirement Savings Program," CNN Money, July 28, 2017. |

| 71. |

Adele Atkinson and Flore-Anne Messy, Promoting Financial Inclusion through Financial Education: OECD/INFE Evidence, Policies and Practice, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions no. 34, 2013, at https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/5k3xz6m88smp-en.pdf. |

| 72. |

CFPB, CFPB Announces Start Small, Save Up Initiative, February 25, 2019, at https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-announces-start-small-save-initiative/. |

| 73. |

Yuka Hayashi, "Consumer Watchdog Wants to Work With Financial Companies to Encourage Saving," The Wall Street Journal, July 17, 2019. |

| 74. |

Heather Hennerich, A Look at the Affordable Banking Movement, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, January 23, 2019, at https://www.stlouisfed.org/open-vault/2019/january/affordable-banking-movement. |

| 75. |

Hennerich, A Look at the Affordable Banking Movement. |

| 76. |

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has released a cost estimate on H.R. 4067, finding that "enacting H.R. 4067 would increase direct spending by $10 million over the 2020-2029 period for the CFPB." CBO, "H.R. 4067, Financial Inclusion in Banking Act of 2019," October 21, 2019, at https://www.cbo.gov/publication/55750. |

| 77. |

For a list of consumer reporting agencies, see "List of Consumer Reporting Agencies," issued by CFPB, at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201501_cfpb_list-consumer-reporting-agencies.pdf. |

| 78. |

For more information on the credit reporting industry, see CRS Report R44125, Consumer Credit Reporting, Credit Bureaus, Credit Scoring, and Related Policy Issues, by Cheryl R. Cooper and Darryl E. Getter. |

| 79. |

Kenneth P. Brevoort, Philipp Grimm, and Michelle Kambara, Data Point: Credit Invisibles, CFPB, May 2015, p. 6, at http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201505_cfpb_data-point-credit-invisibles.pdf. (Hereinafter Brevoort, Grimm, and Kambara, Data Point: Credit Invisibles.) |

| 80. |

Brevoort, Grimm, and Kambara, Data Point: Credit Invisibles, p. 6. |

| 81. |

Brevoort, Grimm, and Kambara, Data Point: Credit Invisibles, p.14. |

| 82. |

Brevoort, Grimm, and Kambara, Data Point: Credit Invisibles, pp.16-23. |

| 83. |

Kenneth P. Brevoort and Michelle Kambara, Data Point: Becoming Credit Visible, CFPB, June 2017, pp. 5 and 8, at https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/BecomingCreditVisible_Data_Point_Final.pdf. |

| 84. |

Brevoort and Kambara, Data Point: Becoming Credit Visible, p. 13; and CFPB, Building a Bridge to Credit Visibility: A Report on the CFPB's September 2018 Building a Bridge to Credit Visibility Symposium, July 2019, p. 12, at https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_building-a-bridge-to-credit-visibility_report.pdf. |

| 85. |

Kenneth Brevoort et al., Data Point: The Geography of Credit Invisibility, CFPB, September 2018, pp. 10-11, at http://s3.amazonaws.com/files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/bcfp_data-point_the-geography-of-credit-invisibility.pdf. |

| 86. |

Brevoort et al., Data Point: The Geography of Credit Invisibility, pp. 11-12. |

| 87. |

Brevoort et al., Data Point: The Geography of Credit Invisibility, p. 13. |

| 88. |

Brevoort and Kambara, Data Point: Becoming Credit Visible, p. 6. |

| 89. |

Brevoort and Kambara, Data Point: Becoming Credit Visible, p. 17. |

| 90. |

CFPB, Building a Bridge to Credit Visibility: A Report on the CFPB's September 2018 Building a Bridge to Credit Visibility Symposium, July 2019, p. 8, at https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_building-a-bridge-to-credit-visibility_report.pdf. (Hereinafter CFPB, Building a Bridge to Credit Visibility.) |

| 91. |

CFPB, Building a Bridge to Credit Visibility, p. 9. |

| 92. |