The Effectiveness of the Community Reinvestment Act

The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA; P.L. 95-128, 12 U.S.C. §§2901-2908) addresses how banking institutions meet the credit needs of the areas they serve, particularly in low- and moderate-income (LMI) neighborhoods. The federal banking regulatory agencies—the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC)—currently implement the CRA. The regulators issue CRA credits, or points, where banks engage in qualifying activities—such as mortgage, consumer, and business lending; community investments; and low-cost services that would benefit LMI areas and entities—that occur with a designated assessment area. These credits are then used to issue each bank a performance rating. The CRA requires these ratings be taken into account when banks apply for charters, branches, mergers, and acquisitions among other things.

The CRA, which was enacted in 1977, was subsequently revised in 1989 to require public disclosure of bank CRA ratings to establish a four-tiered system of descriptive performance levels (i.e., Outstanding, Satisfactory, Needs to Improve, or Substantial Noncompliance). In 1995, the CRA examination was customized to account for differences in bank sizes and business models. In 2005, the bank size definitions were revised and indexed to the Consumer Price Index. The 2005 amendments also expanded opportunities for banks to earn CRA credit for public welfare investments (such as providing housing, services, or jobs that primarily benefit LMI individuals). Qualifying activities under the CRA have evolved to include consumer and business lending, community investments, and low-cost services that would benefit LMI areas and entities.

Congressional interest in the CRA stems from various perceptions of its effectiveness. Some have argued that, by encouraging lending in LMI neighborhoods, the CRA may also encourage the issuance of higher-risk loans to borrowers likely to have repayment problems (under the presumption that low-income is correlated with lower creditworthiness), which can translate into losses for lenders. Others are concerned that the CRA is not generating sufficient incentives to increase credit availability to qualified LMI borrowers, which may impede economic recovery for some, particularly following the 2007-2009 recession.

This report informs the congressional debate concerning the CRA’s effectiveness in incentivizing bank lending and investment activity to LMI borrowers. After a discussion of the CRA’s origins, it presents the CRA’s examination process and bank activities that are eligible for consideration of CRA credits. Next, it discusses the difficulty of determining the CRA’s influence on bank behavior. For example, the CRA does not specify the quality and quantity of CRA-qualifying activities, meaning that compliance with the CRA does not require adherence to lending quotas or benchmarks. In the absence of benchmarks, determining the extent to which CRA incentives have influenced LMI credit availability relative to other factors is not straightforward. Banks also face a variety of financial incentives—for example, capital requirements, the prevailing interest rate environment, changes in tax laws, and technological innovations—that influence how much (or how little) they lend to LMI borrowers. Because multiple financial profit incentives and CRA incentives tend to exist simultaneously, it is difficult to determine the extent to which CRA incentives have influenced LMI credit availability relative to other factors.

The Effectiveness of the Community Reinvestment Act

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- CRA Background and Objectives

- CRA Examinations

- Defining the CRA Assessment Areas

- Qualifying Activities

- The CRA Examination Tests

- Community Investments Qualifying for CRA Consideration

- Results of the CRA Examination

- Difficulties Determining CRA Effectiveness

- Is the CRA Examination Subjective?

- Do Higher-Risk Loans Receive CRA Consideration?

- Subprime Mortgages and the Qualified Mortgage Rule

- Small-Dollar (Payday) Lending

- Do Profit and CRA Incentives Exist Simultaneously?

- Recent Developments

Figures

Tables

Appendixes

Summary

The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA; P.L. 95-128, 12 U.S.C. §§2901-2908) addresses how banking institutions meet the credit needs of the areas they serve, particularly in low- and moderate-income (LMI) neighborhoods. The federal banking regulatory agencies—the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC)—currently implement the CRA. The regulators issue CRA credits, or points, where banks engage in qualifying activities—such as mortgage, consumer, and business lending; community investments; and low-cost services that would benefit LMI areas and entities—that occur with a designated assessment area. These credits are then used to issue each bank a performance rating. The CRA requires these ratings be taken into account when banks apply for charters, branches, mergers, and acquisitions among other things.

The CRA, which was enacted in 1977, was subsequently revised in 1989 to require public disclosure of bank CRA ratings to establish a four-tiered system of descriptive performance levels (i.e., Outstanding, Satisfactory, Needs to Improve, or Substantial Noncompliance). In 1995, the CRA examination was customized to account for differences in bank sizes and business models. In 2005, the bank size definitions were revised and indexed to the Consumer Price Index. The 2005 amendments also expanded opportunities for banks to earn CRA credit for public welfare investments (such as providing housing, services, or jobs that primarily benefit LMI individuals). Qualifying activities under the CRA have evolved to include consumer and business lending, community investments, and low-cost services that would benefit LMI areas and entities.

Congressional interest in the CRA stems from various perceptions of its effectiveness. Some have argued that, by encouraging lending in LMI neighborhoods, the CRA may also encourage the issuance of higher-risk loans to borrowers likely to have repayment problems (under the presumption that low-income is correlated with lower creditworthiness), which can translate into losses for lenders. Others are concerned that the CRA is not generating sufficient incentives to increase credit availability to qualified LMI borrowers, which may impede economic recovery for some, particularly following the 2007-2009 recession.

This report informs the congressional debate concerning the CRA's effectiveness in incentivizing bank lending and investment activity to LMI borrowers. After a discussion of the CRA's origins, it presents the CRA's examination process and bank activities that are eligible for consideration of CRA credits. Next, it discusses the difficulty of determining the CRA's influence on bank behavior. For example, the CRA does not specify the quality and quantity of CRA-qualifying activities, meaning that compliance with the CRA does not require adherence to lending quotas or benchmarks. In the absence of benchmarks, determining the extent to which CRA incentives have influenced LMI credit availability relative to other factors is not straightforward. Banks also face a variety of financial incentives—for example, capital requirements, the prevailing interest rate environment, changes in tax laws, and technological innovations—that influence how much (or how little) they lend to LMI borrowers. Because multiple financial profit incentives and CRA incentives tend to exist simultaneously, it is difficult to determine the extent to which CRA incentives have influenced LMI credit availability relative to other factors.

CRA Background and Objectives

Congress passed the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 (CRA; P.L. 95-128, 12 U.S.C. §§2901-2908) in response to concerns that federally insured banking institutions were not making sufficient credit available in the local areas in which they were chartered and acquiring deposits. According to some in Congress, the granting of a public bank charter should translate into a continuing obligation for that bank to serve the credit needs of the public where it was chartered.1 Consequently, the CRA was enacted to "re-affirm the obligation of federally chartered or insured financial institutions to serve the convenience and needs of their service areas" and "to help meet the credit needs of the localities in which they are chartered, consistent with the prudent operation of the institution." The CRA requires federal banking regulators to conduct examinations to assess whether a bank is meeting local credit needs.2 The regulators issue CRA credits, or points, where banks engage in qualifying activities—such as mortgage, consumer, and business lending; community investments; and low-cost services that would benefit low- and moderate-income (LMI) areas and entities—that occur within assessment areas (where institutions have local deposit-taking operations). These credits are then used to issue each bank a performance rating from a four-tiered system of descriptive performance levels (Outstanding, Satisfactory, Needs to Improve, or Substantial Noncompliance). The CRA requires federal banking regulators to take those ratings into account when institutions apply for charters, branches, mergers, and acquisitions, or seek to take other actions that require regulatory approval.

Congress became concerned with the geographical mismatch of deposit-taking and lending activities for a variety of reasons.3 Deposits serve as a primary source of borrowed funds that banks may use to facilitate their lending. Hence, there was concern that banks were using deposits collected from local neighborhoods to fund out-of-state as well as various international lending activities at the expense of addressing the local area's housing, agricultural, and small business credit needs.4 Another motivation for congressional action was to discourage redlining practices. One type of redlining can be defined as the refusal of a bank to make credit available to all of the neighborhoods in its immediate locality, including LMI neighborhoods where the bank may have collected deposits. A second type of redlining is the practice of denying a creditworthy applicant a loan for housing located in a certain neighborhood even though the applicant may qualify for a similar loan in another neighborhood. This type of redlining pertains to circumstances in which a bank refuses to serve all of the residents in an area, perhaps due to discrimination.5

The CRA applies to banking institutions with deposits insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), such as national banks, savings associations, and state-chartered commercial and savings banks.6 The CRA does not apply to credit unions, insurance companies, securities companies, and other nonbank institutions because of the differences in their financial business models.7 The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the Federal Reserve System, and the FDIC administer the CRA, which is implemented via Regulation BB.8 The CRA requires federal banking regulatory agencies to evaluate the extent to which regulated institutions are effectively meeting the credit needs within their designated assessment areas, including LMI neighborhoods, in a manner consistent with the federal prudential regulations for safety and soundness.9

The CRA's impact on lending activity has been publicly debated. Some observers are concerned that the CRA may induce banks to forgo more profitable lending opportunities in nontargeted neighborhoods by encouraging a disproportionate amount of lending in LMI communities.10 Furthermore, some argue that the CRA compels banks to make loans to higher-risk borrowers that are more likely to have repayment problems, which may subsequently compromise the financial stability of the banking system.11 For example, some researchers have attributed the increase in risky lending prior to the 2007-2009 recession to banks attempting to comply with CRA objectives.12 Others are concerned that enforcement of CRA objectives has not been stringent enough to compel banks to increase financial services in LMI areas.13 Almost all banks receive Satisfactory or better performance ratings (discussed in more detail below) on their CRA examinations, which some may consider indicative of weak enforcement.

This report informs the congressional debate concerning the CRA's effectiveness in incentivizing bank lending and investment activity to LMI customers. It begins with a description of bank CRA examinations, including how a bank delineates its assessment area; the activities that may qualify for points under the three tests (i.e., lending, investment, and service) that collectively make up the CRA examination; and how the composite CRA rating is calculated. Next, the report analyzes the difficulty in attributing bank lending decisions to CRA incentives. For example, the CRA does not specify the quality and quantity of CRA-qualifying activities, meaning that CRA compliance does not require adherence to lending quotas or benchmarks. Without explicit benchmarks, linking the composition of banks' loan portfolios to either too strong or too weak CRA enforcement is difficult. Banks are also unlikely to get CRA credit for all of the loans they make to LMI customers. Specifically, higher-risk loans that banking regulators explicitly discourage are unlikely to be eligible for CRA consideration. Furthermore, greater mobility of lending and deposit-taking activity across regional boundaries due to various financial market innovations has complicated the ability to geographically link various financial activities.14 Hence, many banks' financial activities occurring in a designated assessment area that are eligible for CRA consideration may simply be profitable, meaning they may have occurred without the CRA incentive. Finally, this report summarizes recent policy discussions regarding modernization of the CRA.

CRA Examinations

As noted above, the federal banking regulators conduct regular examinations of banks to assess whether they meet local credit needs in designated assessment areas. The regulators issue CRA credits, or points, when banks engage in qualifying activities—such as mortgage, consumer, and business lending; community investments; and low-cost services that would benefit LMI areas and entities—that occur within assessment areas.

Defining the CRA Assessment Areas

Regulation BB provides the criteria that a bank's board of directors must use to determine the assessment area(s) in which its primary regulator will conduct its CRA examination.15 The assessment area typically has a geographical definition—the location of a bank's main office, branches, and deposit-taking automatic teller machines, as well as surrounding areas where the bank originates and purchases a substantial portion of loans.16 Assessment areas must generally include at least one metropolitan statistical area (MSA) or at least one contiguous political subdivision, such as a county, city, or town.17 Regulation BB also requires that assessment areas may not reflect illegal discrimination, arbitrarily exclude LMI geographies, and extend substantially beyond an MSA boundary or a state boundary (unless the assessment area is located in a multistate MSA). Banking regulators regularly review a bank's assessment area delineations for compliance with Regulation BB requirements as part of the CRA examination.

Instead of a more conventionally delineated assessment area, certain banking firms may obtain permission to devise a strategic plan for compliance with Regulation BB requirements. For example, wholesale and limited purpose banks are specialized banks with nontraditional business models.18 Wholesale banks provide services to larger clients, such as large corporations and other financial institutions; they generally do not provide financial services to retail clients, such as individuals and small businesses. Limited purpose banks offer a narrow product line (e.g., concentration in credit card lending) rather than provide a wider range of financial products and services. These banking firms typically apply to their primary regulators to request designation as a wholesale or limited purpose bank and, for CRA examination purposes, are evaluated under strategic plan options that have been tailored for their distinctive capacities, business strategies, and expertise.19 The option to develop a strategic plan of pre-defined CRA performance goals is available to any bank subject to the CRA.20 The public is allowed time (e.g., 30 days) to provide input on the draft of a bank's strategic plan, after which the bank submits the plan to its primary regulator for approval (within 60 days after the application is received).21

Qualifying Activities

Regulation BB does not impose lending quotas or benchmarks. Instead, Regulation BB provides banks with a wide variety of options to serve the needs of their assessment areas. Qualifying CRA activities include mortgage, consumer, and business lending; community investments; and low-cost services that would benefit LMI areas and entities.22 For example, banks may receive CRA credits for such activities as

- investing in special purpose community development entities (CDEs), which facilitate capital investments in LMI communities (discussed below);

- providing support (e.g., consulting, detailing an employee, processing transactions for free or at a discounted rate, and providing office facilities) to minority- and women-owned financial institutions and low-income credit unions (MWLIs), thereby enhancing their ability to serve LMI customers;

- serving as a joint lender for a loan originated by MWLIs;23

- facilitating financial literacy education to LMI communities, including any support of efforts of MWLIs and CDEs to provide financial literacy education;

- opening or maintaining bank branches and other transactions facilities in LMI communities and designated disaster areas;

- providing low-cost education loans to low-income borrowers;24 and

- offering international remittance services in LMI communities.25

The examples listed above are not comprehensive, but they illustrate several activities banks may engage in to obtain consideration for CRA credits.26 The banking regulators will consider awarding CRA credits or points to a bank if its qualifying activities occur within an assigned assessment area. The points are then used to compute a bank's overall composite CRA rating.

The CRA Examination Tests

Regulators apply up to three tests, which are known as the lending, investment, and service tests, respectively, to determine whether a bank is meeting local credit need in designated assessment areas. The lending test evaluates the number, amount, and distribution across income and geographic classifications of a bank's retail banking activities, which include residential mortgage loans, small business loans, small farm loans, and consumer loans. The investment test grades a bank's community development investments (discussed in more detail in the next section) in the assessment area. The service test examines a bank's retail service delivery, such as the availability of branches and low-cost checking in the assessment area. The point system for bank performance under the lending, investment, and service tests is illustrated in Table 1.27 The lending test is generally regarded as the most important of the three tests, awarding banks the most points (CRA credits) in all rating categories. As shown in Table 1, banks receive fewer credits for making CRA-qualified investments than for providing direct loans to individuals under the lending test. In some instances, an activity may qualify for more than one of the performance tests.28

Table 1. Points Assigned for CRA Performance Under the Individual Lending, Investment, and Service Tests

|

Rating |

Lending |

Investment |

Service |

|

Outstanding |

12 |

6 |

6 |

|

High Satisfactory |

9 |

4 |

4 |

|

Low Satisfactory |

6 |

3 |

3 |

|

Needs to Improve |

3 |

1 |

1 |

|

Substantial Noncompliance |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Source: Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council.

Federal banking regulators evaluate financial institutions based upon their capacity, constraints, and business strategies; demographic and economic data; lending, investment, and service opportunities; and benchmark against competitors and peers. Because these factors vary across banks, the CRA examination was customized in 1995 to account for differences in bank sizes and business models.29

In 2005, the bank size definitions were revised to include small, intermediate small, and large banks.30 The bank regulators also indexed the asset size thresholds—which are adjusted annually—to inflation using the Consumer Price Index.31 As of January 1, 2020, a small bank is defined as having less than $1.305 billion in assets as of December 31 of either of the prior two calendar years; an intermediate small bank has at least $326 million as of December 31 of both of the prior two calendar years but less than $1.305 billion as of December 31 of either of the prior two calendar years;32 and a large bank has $1.305 billion or more in assets.

Small banks are typically evaluated under the lending test. Regulators review (1) loan-to-deposit ratios; (2) percentage of loans in an assessment area; (3) lending to borrowers of different incomes and in different amounts; (4) geographical distribution of loans; and (5) actions on complaints about performance. Intermediate small banks are subject to both the lending and investment tests. Large banks are subject to all three tests.

Community Investments Qualifying for CRA Consideration

As mentioned previously, direct lending to borrowers, taking place in what is referred to as primary lending markets, qualify for CRA credit under the lending test. Investments taking place in secondary lending markets, in which investors purchase loans that have already been originated (such that little or no direct interaction occurs between investors and borrowers), qualify for CRA credit under the investment test. Secondary market investors may assume the default risk associated with a loan if the entire loan is purchased. Alternatively, if a set of loans are pooled together, then numerous secondary investors may purchase financial securities in which the returns are generated by the principal and interest repayments from the underlying loan pool, thereby sharing the lending risk. Direct ownership of loans or purchases of smaller portions (debt securities) of a pool of loans, therefore, are simply alternative methods to facilitate lending. As shown in Table 1 above, a bank may receive CRA consideration under the lending test for making a loan to LMI individuals that is guaranteed by a federal agency, such as the Federal Home Administration (FHA).33 If, however, a bank purchases securities backed by pools of FHA-guaranteed mortgage originations, this activity receives credit under the investment test. Thus, the bank receives less CRA credit when the financial risk is shared with other lenders than it would for making a direct loan (and holding all of the lending risk) even though it would still facilitate lending to LMI borrowers.

In 2005, the activities that qualify for CRA credit were expanded to encourage banks to make public welfare investments. More specifically, qualifying activities include

- a public welfare investment (PWI) that promotes the public welfare by providing housing, services, or jobs that primarily benefit LMI individuals;34 and

- a community development investment (CDI), economic development investment, or project that meets the PWI requirements.35 Examples of CDI activities include promoting affordable housing, financing small businesses and farms, and conducting activities that revitalize LMI areas.

Banks may engage in certain activities that typically would not be permitted under other banking laws as long as these activities promote the public welfare and do not expose institutions to unlimited liability.36 For example, banks generally are not allowed to make direct purchases of the preferred or common equity shares of other banking firms; however, banks may purchase equity shares of institutions with a primary mission of community development (discussed in more detail in the Appendix) up to an allowable CDI limit.37 The Financial Services Regulatory Relief Act of 2006 (P.L. 109-351) increased the amount that national banking associations and state banks (that are members of the Federal Reserve System) may invest in a single institution from 10% to 15% of a bank's unimpaired capital and unimpaired surplus.38

CDIs that benefit a bank's designated assessment area may qualify for CRA credit. For CRA purposes, the definition of a CDI was expanded in 2005 to include "underserved and distressed" rural areas39 and "designated disaster areas"40 to aid the regional rebuilding from severe hurricanes, flooding, earthquakes, tornados, and other disasters.41 The disaster area provision allows banks anywhere in America to receive consideration for CRA credit if they facilitate making credit available to a distressed location or geographic area outside of their own assessment areas. Thus, the 2005 revisions to the PWI and CDI definitions made more banking activities eligible for CRA credits.

The banking regulators would consider awarding full CRA credits under the lending test to banks that make CDI loans directly in their assessment areas. Under the investment test, however, the banking regulators may choose to prorate the credits awarded to indirect investments.42 The Appendix provides examples of CDI activities that would qualify for CRA consideration under the investment test. Any awarded CRA credits could be prorated given that investing banks typically would have less control over when and where the funds are loaned.

Results of the CRA Examination

The CRA was revised in 1989 to require descriptive CRA composite performance ratings that must be disclosed to the public.43 The composite ratings illustrated in Table 2 are tabulated using the points assigned from the individual tests (shown in Table 1 above). Grades of Outstanding and Satisfactory are acceptable; Satisfactory ratings in both community development and retail lending are necessary for a composite Satisfactory.44 Large banks must receive a sufficient amount of points from the investment and service tests to receive a composite Outstanding rating.

|

CRA Composite Rating |

Total Point Requirements |

|

|

Outstanding |

|

|

|

Satisfactory |

|

|

|

Needs to Improve |

|

|

|

Substantial Noncompliance |

|

Source: Federal Financial Institutions Examinations Council.

Regulators include CRA ratings as a factor when lenders request permission to engage in certain activities, such as moving offices or buying another institution. Denying requests, particularly applications for mergers and acquisitions, is a mechanism that may be applied against banking organizations with ratings below Satisfactory. In 2005, the banking regulators also ruled that any evidence of discrimination or credit practices that violate an applicable law, rule, or regulation by any affiliate would adversely affect an agency's evaluation of a bank's CRA performance.45 Applicants with poor ratings may resubmit their applications after making the necessary improvements. Covered institutions must post a CRA notice in their main offices and make publicly available a record of their composite CRA performance.46

Difficulties Determining CRA Effectiveness

Given that the CRA is not a federal assistance program and that several regulators implement it separately, no single federal agency is responsible for evaluating its overall effectiveness. In 2000, Congress directed the Federal Reserve to study the CRA's effectiveness.47 The Federal Reserve's study reported that lending to LMI families had increased since the CRA's enactment but found it was not possible to directly attribute all of that increase to the CRA. For example, advancements in underwriting over the past several decades have enabled lenders to better predict and price borrower default risk, thus making credit available to borrowers that might have been rejected prior to such technological advances.48 This section examines the difficulty linking bank lending outcomes directly to the CRA, considering questions raised about the subjectivity of the CRA examination itself, whether prudential regulators use CRA to encourage banks to engage in high-risk lending, and whether the increased lending to LMI borrowers since CRA's enactment can be attributed to other profit-incentives that exist apart from the CRA.49

Is the CRA Examination Subjective?

Questions have been raised as to whether the CRA examination itself is effective at measuring a bank's ability to meet local credit needs. For example, the CRA examinations have an element of subjectivity in terms of measuring both the quality and quantity of CRA compliance. In terms of quality, regulators determine the "innovativeness or flexibility" of qualified loan products; the "innovativeness or complexity" of qualified investments; or the "innovativeness" of ways banks service groups of customers previously not served.50 The number of points some CRA-qualifying investments receive relative to others is up to the regulator's judgment given that no formal definition of innovativeness has been established (although regulators provide a variety of examples as guidelines for banks to follow).51 In terms of quantity, there is no official quota indicating when banks have done enough CRA-qualified activities to receive a particular rating. Without specific definitions of the criteria or quotas, the CRA examination may be considered subjective.

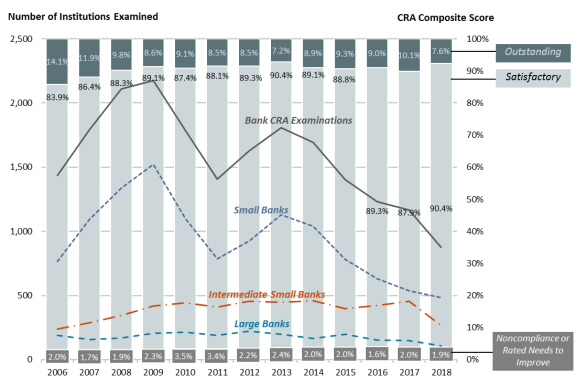

Almost all banks pass their CRA examinations. Figure 1 shows the average annual composite scores of banks that received CRA examinations as well as the annual number of bank examinations by size.52 In general, most banks receive a composite Satisfactory or better rating regardless of the number of banks examined in a year. For all years, approximately 97% or more of banks examined received ratings of Satisfactory or Outstanding. Whether the consistently high ratings reflect the CRA's influence on bank behavior or whether the CRA examination procedures need improvement is difficult to discern.

|

Figure 1. Summary of Annual CRA Examinations: Number of Banks Examined and Average Composite Ratings 2006-2018 (4th quarter) |

|

|

Source: CRS, Data provided by the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council CRA Rating Search, at http://www.ffiec.gov/craratings/default.aspx. |

Do Higher-Risk Loans Receive CRA Consideration?

Another issue raised is whether the CRA has resulted in banks making more high-risk loans given that it encourages banks to lend to LMI individuals (perhaps under the presumption that LMI individuals are less creditworthy relative to higher-income individuals). Since passage of the CRA, however, innovations have allowed lenders to better evaluate the creditworthiness of borrowers (e.g., credit scoring, the adoption of automated underwriting), thus enhancing credit availability to both high credit quality and credit-impaired individuals. Credit-impaired borrowers can be charged higher interest rates and fees than those with better credit histories to compensate lenders for taking on greater amounts of credit or default risk.53 Nontraditional loan products (e.g., interest-only, initially low interest rate) allow borrowers to obtain lower regular payments during the early stages of the loan, perhaps under the expectation that their financial circumstances may improve in the later stages as the loan payments adjust to reflect the true costs. The ability to charge higher prices or offer such nontraditional loan products may result in greater higher-risk lending. Because these technological developments in the financial industry occurred after enactment of the CRA, banks' willingness to enter into higher-risk lending markets arguably cannot be attributed solely to the CRA.

Regulators arguably are more reluctant to award banks CRA credit for originating higher-risk loans given the scrutiny necessary to determine whether higher loan prices reflect elevated default risk levels or discriminatory or predatory lending practices.54 Primary bank regulators are concerned with both prudential regulation and consumer protection.55 It is difficult for regulators to monitor how well borrowers understood the disclosures regarding loan costs and features, or whether any discriminatory or predatory behavior occurred at the time of loan origination.56 Regulators use fair lending examinations to determine whether loan pricing practices have been applied fairly and consistently across applicants or if some steering to higher-priced loan products occurred. Nevertheless, although it is not impossible for banks to receive CRA credits for making some higher-priced loans, regulators are mindful of practices such as improper consumer disclosure, steering, or discrimination that inflate loan prices.57 Prudential regulators are also unlikely to encourage lending practices that might result in large concentrations of high-risk loans on bank balance sheets.58 Hence, certain lending activities—subprime mortgages and payday lending—have been explicitly discouraged by bank regulators, as discussed in more detail below.

Subprime Mortgages and the Qualified Mortgage Rule

Although no consensus definition has emerged for subprime lending, this practice may generally be described as lending to borrowers with weak credit at higher costs relative to borrowers of higher credit quality.59 In September 2006, the banking regulatory agencies issued guidance on subprime lending that was restrictive in tone.60 The guidance warned banks of the risk posed by nontraditional mortgage loans, including interest-only and payment-option adjustable-rate mortgages. The agencies expressed concern about these loans because of the lack of principal amortization and the potential for negative amortization. Consequently, a study of 2006 Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data reported that banks subject to the CRA and their affiliates originated or purchased only 6% of the reported high-cost loans made to lower-income borrowers within their CRA assessment areas.61 Banks, therefore, received little or no CRA credit for subprime mortgage lending. Instead, federal regulators offered CRA consideration to banks that helped mitigate the effects of distressed subprime mortgages.62 On April 17, 2007, federal regulators provided examples of various arrangements that financial firms could provide to LMI borrowers to help them transition into affordable mortgages and avoid foreclosure. The various workout arrangements were eligible for favorable CRA consideration.63

Banks are unlikely to receive CRA consideration for originating subprime mortgages going forward. The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (Dodd-Frank Act; P.L. 111-203) requires lenders to consider consumers' ability to repay before extending them mortgage credit, and one way for lenders to comply is to originate qualified mortgages (QMs) that satisfy various underwriting and product-feature requirements.64 For example, QMs may not have any negative amortization features, interest-only payments, or points and fees that exceed specified caps of the total loan amount; in most cases, borrowers' debt-to-income ratios shall not exceed 43%. QM originations will give lenders legal protections if the required income verification and other proper underwriting procedures were followed. Given the legal protections afforded to QMs, some banks might show greater reluctance toward making non-QM loans. With this in mind, the federal banking regulators announced that banks choosing to make only or predominately QM loans should not expect to see an adverse effect on their CRA evaluations; however, the regulators did not indicate that CRA consideration would be given for non-QMs.65 Arguably, the federal banking regulators appear less inclined to use the CRA to encourage lending that could be subject to greater legal risks.

Small-Dollar (Payday) Lending

Banks have demonstrated interest in providing financial services such as small dollar cash advances, which are similar to payday loans, in the form of subprime credit cards, overdraft protection services, and direct deposit advances. However, banks are discouraged from engaging in payday and similar forms of lending.66 Legislation, such as the Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-24), placed restrictions on subprime credit card lending. In addition, federal banking regulators expressed concern when banks began offering deposit advance products due to the similarities to payday loans.67 Specifically, on April 25, 2013, the OCC, FDIC, and Federal Reserve expressed concerns that the high costs and repeated extensions of credit could add to borrower default risks and issued final supervisory guidance regarding the delivery of these products.68 Many banks subsequently discontinued offering deposit advances.69

In general, these legislative and regulatory efforts explicitly discourage banks from offering high-cost consumer financial products and thus such products are unlikely to receive CRA consideration. When various financial products are deemed unsound by bank regulators and not offered by banks, a possible consequence may be that some customers migrate to nonbank institutions willing to provide these higher-cost products.70 Accordingly, the effectiveness of the CRA diminishes if more individuals choose to seek financial products from nonbank institutions.

Do Profit and CRA Incentives Exist Simultaneously?

In general, it can be difficult to determine the extent to which banks' financial decisions are motivated by CRA incentives, profit incentives, or both. Compliance with CRA does not require banks to make unprofitable, high-risk loans that would threaten the financial health of the bank. Instead, CRA loans have profit potential; and bank regulators require all loans, including CRA loans, to be prudently underwritten. As evidenced below, it may be difficult to determine whether banks have made particular financial decisions in response to profit or CRA incentives in cases where those incentives exist simultaneously.

- For example, banks increased their holdings of municipal bonds in 2009. Although banks may receive CRA consideration under the investment test for purchasing state and local municipal bonds that fund public and community development projects in their designated assessment areas, banks may choose this investment for reasons unrelated to CRA. During recessions, for example, banks may reduce direct (or primary market) lending activities and increase their holdings of securities in the wake of declining demand for and supply of direct loan originations that occur during economic slowdowns and early recovery periods.71 In addition, a provision of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5) provided banks with a favorable tax incentive to invest in municipal bonds in the wake of the 2007-2009 recession.72 Hence, determining whether banks increased their municipal holdings because of a turn to securities markets for higher yields following a recession, a favorable tax incentive, or the CRA incentive is challenging.

- Similarly, banks increased their investments in Small Business Investment Corporations (SBICs, defined in the Appendix) in 2010. Investments in SBICs allow banks to provide subordinate financing (rather than senior debt) to businesses. Senior lenders have first claims to the business's assets in case of failure; however, subordinate financiers provide funds in the form of mezzanine capital or equity, requiring a higher return because they are repaid after senior lenders. Banks generally are not allowed to act as subordinate financiers because they are not allowed to acquire ownership interests in private equity funds, unless such investments promote public welfare.73 Hence, attributing community development financing activities, such as SBIC investments, to CRA incentives may arguably be easier (relative to other financing activities) because the ability to engage in subordinate financing activities typically represents a CRA exemption from ordinary permissible banking activities.74 Following the 2007-2009 recession, however, U.S. interest rates dropped to historically low levels for an abnormally long period of time. Because low-yielding interest rate environments squeeze profits, banks were likely to search for higher-yielding and larger-sized lending opportunities, such as investments in SBICs. Hence, it remains difficult to determine whether a particular bank's decision to increase SBIC financing activities was driven by normal profit or CRA-related incentives.

- Between June 2016 and June 2017, more than 1700 U.S. bank branches were closed.75 Many branch closings occurred primarily in rural and low-income tract areas, raising concerns that banks would be able to circumvent their CRA obligation to lend and be evaluated in these areas.76 A traditional bank business model, however, relies primarily on having access to core deposits, a stable source of funds used to subsequently originate loans.77 Banks value geographic locations with greater potential to attract high core deposit volumes, which is also consistent with the CRA's requirement that assessment areas include at least one MSA or contiguous political subdivision (as previously discussed). Furthermore, using FDIC and U.S. Census Bureau data, the Federal Reserve noted that the number of branches per capita in 2017 was higher than two decades ago.78 Hence, determining whether branch closures reflect a bank's intentions to circumvent CRA compliance or to facilitate its ability to attract core deposits is challenging.

Recent Developments

On December 12, 2019, the OCC and FDIC released a joint Notice of Proposed Rulemaking to update the CRA regulations "to make the regulatory framework more objective, transparent, consistent, and easy to understand."79 The comment period ends on March 9, 2020. The bullet points below provide an overview of selected provisions from the proposed rule.

- As previously discussed, under the current CRA regulatory framework, a bank may obtain permission to devise a strategic plan for compliance if it wishes to delineate a nonconventional assessment area. The proposed rule arguably may achieve a similar outcome via a two-step process. The proposal introduces a facility-based assessment area that delineates an assessment area around a bank's main office, branches, or non-branch deposit-taking facilities, as well as surrounding areas where it has originated or purchased a substantial portion of its retail loans. Hence, the facility-based assessment area component addresses a bank's CRA obligation based upon its physical location. Second, if a bank receives 50% or more of its retail domestic deposits from geographic areas outside of its facility-based assessment area, then it would be required to delineate a deposit-based assessment area, which includes any additional (nonoverlapping) areas where it sources at least 5% of its total retail deposits. Hence, the deposit-based assessment area addresses a bank's CRA obligation based upon activities that may occur (via the internet) outside of a geographical location. Both the facility-based assessment area and additional deposit-based assessment areas would be combined and used to evaluate a bank's CRA activity. The proposal still retains the option for banks to develop strategic plans for atypical circumstances.

- Under the existing framework, many community development (CD) activities—including joint lending arrangements (discussed in the Appendix of this report under Loan Participations)—can be interpreted as qualifying activities. The proposal would replace the term qualified investment used in current regulations with community development investment, and it would expressly state qualifying CD activities. The definition of CD investments would also be expanded to include banks' commitments to lend and invest.80 According to the OCC and FDIC, reducing subjectivity and designating what CD activities would automatically receive CRA credit arguably may incentivize banks to expand CRA activities. The regulators' discretion to prioritize prudential concerns, however, is uncertain. For example, bank regulators under the existing framework can choose not to award CRA credit to loans that could pose greater credit or insolvency risk for a bank, particularly if a financially distressed institution would pose more harm than benefit to a LMI community. If a bank delays originating a loan until receiving CRA credit confirmation, it may ultimately be waiting to see if such lending activity is (1) eligible for more favorable capital or liquidity treatment (relative to non-CRA activities) or (2) granted an exemption from an otherwise impermissible activity (e.g., SBIC investment). In short, the proposal does not discuss whether a bank's cost to fund an investment opportunity may be affected if CRA credit is awarded, making it unclear why a bank might forgo a profitable lending opportunity without advance assurance of CRA confirmation.

- The proposal would revise the definition of a small bank (for the purposes of complying with CRA) to one with assets up to $500 million, and a separate category for intermediate small banks would not be included. The asset-size threshold would continue to be adjusted annually based on changes in the CPI. These small banks would not be subject to the community development test nor be required to engage in CD activities. Instead, these banks would continue to be evaluated under the existing CRA regulatory framework.

- For banks with assets above $500 million, the proposal introduces three empirical tests for evaluating CRA performance: a CRA evaluation test, a retail lending distribution test, and a CD minimum test.81 The ratings of Outstanding and Satisfactory, for example, would be assigned depending upon whether a bank exceeds or meets a combination of benchmark thresholds.82 Whether community banks with assets greater than $500 million would face greater challenges meeting the proposed empirical metrics' thresholds is not currently addressed in the proposed rule.83

- Currently, the size threshold for a small retail business loan is $1 million and for a small farm loan is $500,000. Loans of these sizes or smaller are eligible for CRA credit under the lending test. For loans made in excess of these thresholds, banks must provide justification and receive credit under the investment test.84 The proposed rule would increase the size of both thresholds to $2 million.85

- Banks that receive a rating of Outstanding would qualify for a five-year CRA evaluation period.

- The FDIC estimates that the proposed rule may increase compliance costs for all small FDIC institutions. Specifically, the FDIC estimates that, assuming the costs of certain labor services, the annual compliance costs would total $93,000 for banks subject to the small bank performance standards and $665,802.45 for banks subject to the new general performance standards. Some of these costs may also stem from the requirement to collect and maintain data for each qualifying loan or CD investment held on-balance sheet as well as for any CD services and monetary or in-kind donations until the completion of its next evaluation. The data collection requirement arguably may also add to the compliance costs for small banks, which may be why the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau delayed implementing a rule that would require the reporting of small business lending data.86

The Federal Reserve did not join the OCC and FDIC in the proposed rulemaking because of its concern that the proposal might have unintended consequences. Specifically, the Federal Reserve is concerned that it may be possible to satisfy the empirical metrics without fully meeting CRA expectations in terms of local needs.87 At this point, the Federal Reserve is conducting further data analysis before implementing any empirical metrics.

Appendix. CRA Investment Options

Community development investments that meet public welfare investment (PWI) requirements are those that promote the public welfare, primarily resulting in economic benefits for low- and moderate-income (LMI) individuals. This appendix provides examples of CDI activities that would qualify for consideration under the CRA investment test. In many cases, covered banks are more likely to take advantage of these optional vehicles to obtain CRA credits if they perceive the underlying investment opportunities to have profit potential.

Loan Participations

Banks and credit unions often use participation (syndicated) loans to jointly provide credit. When a financial firm (e.g., bank, credit union) originates a loan for a customer, it may decide to structure loan participation arrangements with other institutions.88 The loan originator often retains a larger portion of the loan and sells smaller portions to other financial institutions willing to participate. Suppose a financial firm originates a business or mortgage loan in a LMI neighborhood. A bank may receive CRA investment credit consideration by purchasing a participation, thus becoming a joint lender to the LMI borrower. An advantage of loan participations is that the default risk is divided and shared among the participating banks (as opposed to one financial firm retaining all of the risk). CRA consideration is possible if the activity occurs within the designated assessment area. For all participating banks to receive credit, some overlap in their designated assessment areas must exist. An exception is made for participations made to benefit designated disaster areas, in which all participating banks would receive CRA consideration regardless of location.

State and Local Government Bonds

State and local governments issue municipal bonds, and the proceeds are used to fund public projects, community development activities, and other qualifying activities.89 The interest that nonbank municipal bondholders receive is exempt from federal income taxes to encourage investment in hospitals, schools, infrastructure, and community development projects that require state and local funding. Legislative actions during the 1980s eliminated the tax-exempt status of interest earned from holdings of municipal bonds for banks.90 Although banks no longer have a tax incentive to purchase municipal bonds, they still consider the profitability of holding these loans, as they do with all lending opportunities. Furthermore, banks receive CRA investment consideration when purchasing state and local municipal bonds that fund public and community development projects in their designated assessment areas.

CRA-Targeted Secondary Market Instruments

Secondary market financial products have been developed to facilitate the ability of banks to participate in lending activities eligible for CRA consideration, such as purchasing mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) or shares of real estate investment trusts (REITs). A MBS is a pool of mortgage loans secured by residential properties; a multifamily MBS is a pool of mortgage loans secured by multifamily properties, consisting of structures designed for five or more residential units, such as apartment buildings, hospitals, nursing homes, and manufactured homes. CRA-MBSs are MBSs consisting of loans that originated in specific geographic assessment areas, thereby allowing bank purchases into these pools to be eligible for CRA consideration under the investment test.91 Similarly, REITs may also pool mortgages, mortgage MBSs, and real estate investments (e.g., real property, apartments, office buildings, shopping malls, hotels). Investors purchase shares in REIT pools and defer the taxes.92 Banks may only invest in mortgage REITs and MBS REITs. Similar to the CRA-MBSs, the REITs must consist of mortgages and MBSs that would be eligible for CRA consideration. The Community Development Trust REIT is an example of a REIT that serves as a CRA-qualified investment for banks.93

Community Development Financial Institutions and Equity Equivalent Investments

The Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund was created by the Riegle Community Development Regulatory Improvement Act of 1994 (the Riegle Act; P.L. 103-325).94 The CDFI Fund was established to promote economic development for distressed urban and rural communities. The CDFI Fund, currently located within the U.S. Department of the Treasury, is authorized to certify banks, credit unions, nonprofit loan funds, and (for-profit and nonprofit) venture capital funds as designated CDFIs.95 In other words, a bank may satisfy the requirements to become a CDFI, but not all CDFIs are banks. The primary focus of institutions with CDFI certification is to serve the financial needs of economically distressed people and places. The designation also makes these institutions eligible to receive financial awards and other assistance from the CDFI Fund.96

In contrast to non-CDFI banks, some CDFI banks have greater difficulty borrowing funds and then transforming them into loans for riskier, economically distressed consumers.97 The lack of loan level data for most CDFI banks causes creditors to hesitate in making low-cost, short-term loans to these institutions. Specifically, the lack of information on loan defaults and prepayment rates on CDFI banking assets is likely to result in limited ability to sell these loan originations to secondary loan markets. Consequently, the retention of higher-risk loans, combined with limited access to low-cost, short-term funding, makes CDFI banks more vulnerable to liquidity shortages.98 Hence, CDFIs rely primarily on funding their loans (assets) with net assets, which are proceeds analogous to the equity of a traditional bank or net worth of a credit union. CDFI net assets are often acquired in the form of awards or grants from the CDFI Fund or for-profit banks. Funding assets with net assets is less expensive for CDFIs than funding with longer-term borrowings.

Banks may obtain CRA investment credit consideration by making investments to CDFIs, which provides CDFIs with net assets (equity). Under PWI authority, banks are allowed to make equity investments in specialized financial institutions, such as CDFIs, as long as they are considered by their safety and soundness regulator to be at least adequately capitalized.99 Furthermore, the final Basel III notification of proposed regulation (NPR)100 allows for preferential capital treatment for equity investments made under PWI authority, meaning equity investments to designated CDFIs may receive more favorable capital treatment.101 Consequently, banks often provide funds to CDFIs through equity equivalent investments (EQ2s), which are debt instruments issued by CDFIs with a continuous rolling (indeterminate) maturity. EQ2s, from a bank's perspective, are analogous to holding convertible preferred stock with a regularly scheduled repayment.102 Hence, banks may view EQ2s as a potentially profitable opportunity to invest in other specialized financial institutions and receive CRA consideration, particularly when the funds are subsequently used by CDFIs to originate loans in the banks' assessment areas.103

Small Business Investment Companies

The Small Business Administration (SBA) was established in 1953 by the Small Business Act of 1953 (P.L. 83-163) to support small businesses' access to capital in a variety of ways.104 Although issuing loan guarantees for small businesses is a significant component of its operations, the SBA also has the authority to facilitate the equity financing of small business ventures through its Small Business Investment Company (SBIC) program, which was established by the Small Business Investment Act of 1958 (P.L. 85-699).105 SBICs that are licensed and regulated by the SBA may provide debt and equity financing and, although not a program requirement, educational (management consulting) resources for businesses that meet certain SBA size requirements.106

Banks may act as limited partners if they choose to provide funds to SBICs, which act as general partners.107 Banks may establish their own SBICs, jointly establish SBICs (with other banks), or provide funds to existing SBICs. SBICs subsequently use bank funding to invest in the long-term debt and equity securities of small, independent (SBA-eligible) businesses, and banks may receive CRA investment consideration if the activities benefit their assessment areas.108 Community banks invest in SBICs because of the profit potential as well as the opportunity to establish long-term relationships with business clients during their infancy stages. Banks that are considered by their regulators to be adequately capitalized are allowed to invest in these specialized financial institutions under PWI authority, but the investments still receive risk-based capital treatment.109 SBIC assets, similar to CDFIs, are illiquid given the difficulty to obtain credit ratings for SBIC investments; thus, they cannot be sold in secondary markets.110 Because banks risk losing the principal of their equity investments, they are required to perform the proper due diligence associated with prudent underwriting.111

Tax Credits

The low-income housing tax credit (LIHTC) program was created by the Tax Reform Act of 1986 (P.L. 99-514) to encourage the development and rehabilitation of affordable rental housing.112 Generally speaking, government (federal or state) issued tax credits may be bought and, in many cases, sold like any other financial asset (e.g., stocks and bonds). Owners of tax credits may reduce their tax liabilities either by the amount of the credits or by using the formulas specified on those credits, assuming the owners have participated in the specified activities that the government wants to encourage. For LIHTCs, banks may use a formula to reduce their federal tax liabilities when they provide either credit or equity contributions (grants) for the construction and rehabilitation of affordable housing. If a bank also owns a LIHTC, then a percentage of the equity grant may be tax deductible if the CDFI uses the funds from the grant to finance affordable rental housing. Furthermore, banks may receive consideration for CRA-qualified investment credits.

After a domestic corporation or partnership receives designation as a Community Development Entity (CDE) from the CFDI Fund, it may apply for New Markets Tax Credits (NMTCs). Encouraging capital investments in LMI communities is the primary mission of CDEs, and CDFIs and SBICs automatically qualify as CDEs.113 Only CDEs are eligible to compete for NMTCs, which are allocated by the CDFI Fund via a competitive process. Once awarded an allocation of NMTCs, the CDE must obtain equity investments in exchange for the credits. Then, the equity proceeds raised must either be used to provide loans or technical assistance or deployed in eligible community investment activities. Only for-profit CDEs, however, may provide NMTCs to their investors in exchange for equity investments.114 Investors making for-profit CDE equity investments can use the NMTCs to reduce their tax liabilities by a certain amount over a period of years. As previously discussed, a bank may receive CRA credit for making equity investments in nonprofit CDEs and for-profit subsidiaries, particularly if the investment occurs within the bank's assessment area. Furthermore, banks may be able to reduce their tax liabilities if they can obtain NMTCs from the CDEs in which their investments were made.

Author Contact Information

Denise Penn made substantive contributions to the report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

See U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, Community Credit Needs, S. 406, 95th Cong., 1st sess., March 23-25, 1977, pp. 1-429. |

| 2. |

The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency conducts a Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 (CRA) examination of national banks every three years, see "CRA Questions and Answers" at https://www.occ.treas.gov/topics/compliance-bsa/cra/questions-and-answers.html. For banks supervised by the Federal Reserve, see "Consumer Compliance and CRA Examination Mandates, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/supervisionreg/caletters/Attachment_CA_13-20_Frequency_Guidance.pdf. The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999 (GLBA; P.L. 106-102) mandated the examination for smaller banks of $250 million or less. For more information, see "Consumer Compliance Examinations—Examination and Visitation Frequency," at https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/compliance/manual/2/ii-12.1.pdf. P.L. 109-351, the Financial Services Regulatory Relief Act of 2006, reduced the frequency of on-site CRA examinations for smaller banking institutions. |

| 3. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, Housing and Community Development Act of 1977, committee print, prepared by Report to accompany S. 1523, 95th Cong., 1st sess., May 16, 1977, Report No. 95 175 (Washington: GPO, 1977), pp. 33-35. |

| 4. |

During the 20th century, U.S. banks began to expand their operations across designated geographical boundaries. For example, large regional banks in the 1960s and 1970s expanded their lending operations internationally and, in some cases, established foreign branches. The U.S. banking system was also transitioning from a system characterized primarily by unit banking, in which a small, independent bank operated solely in one state with no branches, to interstate banking. Interstate banking and branching allows a bank to conduct activities (e.g., accepting deposits, lending) across geographical (state) boundaries, forgoing the need to establish separate subsidiaries for each locality in which it operates and, therefore, having to duplicate the operating costs and capital requirements in each subsidiary. See James V. Houpt, "International Activities of U.S. Banks and in U.S. Banking Markets," Federal Reserve Bulletin, September 1999, pp. 599-615, at http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/bulletin/1999/0999lead.pdf; Frederick R. Dahl, "International Operations of U.S. Banks: Growth and Public Policy Implications," Law and Contemporary Problems, Winter 1967, pp. 100-130; and David L. Mengle, "The Case for Interstate Branch Banking," Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Economic Review, vol. 76 (November 1990), at http://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/economic_review/1990/pdf/er760601.pdf. The Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-328, 108 Stat. 2338) overrode long-standing state prohibitions against nationwide banking. See Susan McLaughlin, "The Impact of Interstate Banking and Branching Reform: Evidence from the States," Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Current Issues in Economics and Finance, vol. 1, no. 2 (May 1995), at http://www.ny.frb.org/research/current_issues/ci1-2.pdf. |

| 5. |

For a description of the Fair Housing Act (Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, P.L. 90-284, 42 U.S.C. §3601 et seq.), see http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/supmanual/cch/fair_lend_fhact.pdf. For more information about the Fair Housing Act, see CRS Report 95-710, The Fair Housing Act (FHA): A Legal Overview, by David H. Carpenter; and CRS Report R44557, The Fair Housing Act: HUD Oversight, Programs, and Activities, by Libby Perl. |

| 6. |

See Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), Community Reinvestment Act, Fact Sheet, March 2014, at http://www.occ.gov/topics/community-affairs/publications/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-cra-reinvestment-act.pdf. |

| 7. |

Credit unions have membership restrictions, meaning these institutions may only lend to their members. A credit union may get permission to lend outside of its membership if it wants to operate in an underserved area. See CRS In Focus IF11048, Introduction to Bank Regulation: Credit Unions and Community Banks: A Comparison, by Darryl E. Getter. Insurance and securities companies do not hold federally insured deposits and are not subject to the CRA. |

| 8. |

The OCC is the primary regulator for national banks. The Federal Reserve System is the primary regulator for bank holding companies and some state banks. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) is the primary regulator for state banks not under the Federal Reserve. For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10035, Introduction to Financial Services: Banking, by Raj Gnanarajah and David W. Perkins. Several states also have separate community reinvestment laws applicable to banking institutions under their supervision. |

| 9. |

Safety and soundness regulation refers to banks maintaining prudent loan underwriting standards and sufficient regulatory capital to buffer against default risks and prudently underwrite CRA-qualified loans. |

| 10. |

For example, see Yaron Brook, "The Government Did It," Forbes, July 18, 2008, at http://www.forbes.com/2008/07/18/fannie-freddie-regulation-oped-cx_yb_0718brook.html. |

| 11. |

See Michael V. Berry, "Historical Perspectives on the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977," Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, ProfitWise News and Views, December 2013, at http://www.chicagofed.org/digital_assets/publications/profitwise_news_and_views/2013/PNVDec2013_FINAL_web.pdf. |

| 12. |

See Sumit Agarwal et al., Did the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) Lead to Risky Lending?, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Working Paper no. 18609, December 2012, at http://www.nber.org/papers/w18609.pdf. |

| 13. |

For example, see Roberto Quercia, Janneke Ratcliffe, and Michael A. Stegman, "The CRA: Outstanding, and Needs to Improve," in Revisiting the CRA: Perspectives on the Future of the Community Reinvestment Act, Federal Reserve Banks of Boston and San Francisco, February 2009, pp. 47-58, at http://www.frbsf.org/community-development/files/revisiting_cra.pdf. |

| 14. |

See Robert B. Avery, Marsha J. Courchane, and Peter Zorn, "The CRA Within A Changing Financial Landscape," Federal Reserve Banks of Boston and San Francisco, in Revisiting the CRA: Perspectives on the Future of the Community Reinvestment Act, February 2009, pp. 30-47, at http://www.frbsf.org/community-development/files/revisiting_cra.pdf. |

| 15. |

See Kenneth Benton and Donna Harris, "Understanding the Community Reinvestment Act's Assessment Area Requirements," Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, Consumer Compliance Outlook, First Quarter 2014, at https://consumercomplianceoutlook.org/2014/first-quarter/understanding-cras-assessment-area-requirements/. |

| 16. |

See Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, "Consumer Affairs: Delineation of Assessment Areas," August 1, 2017, at https://www.kansascityfed.org/en/banking/fedconnections/archive/delineation-of-assessment-areas-8-1-17. |

| 17. |

According to the U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB), a metropolitan statistical area (MSA) is a core area containing a substantial population nucleus, together with adjacent communities having a high degree of economic and social integration with that core. See "Metropolitan and Micropolitan," at https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/metro-micro/about.html. |

| 18. |

See OCC, "Wholesale and Limited Purpose Banks under the Community Reinvestment Act," January 11, 2012, at https://www.occ.treas.gov/topics/compliance-bsa/cra/wholesale-and-limited-purpose-banks-under-cra.html. |

| 19. |

See OCC, "National Banks Evaluated On the Basis of a Strategic Plan under the Community Reinvestment Act," September 14, 2017, at https://www.occ.treas.gov/topics/compliance-bsa/cra/strategic-plan-under-cra.html. |

| 20. |

See OCC, "Guidelines for Requesting Approval for a Strategic Plan under the Community Reinvestment Act, at https://www.occ.treas.gov/news-issuances/bulletins/1996/bulletin-1996-11a.html. |

| 21. |

See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, "Community Reinvestment Act: Strategic Plans," December 7, 2018, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/consumerscommunities/cra_strategic.htm; and FDIC, "Approved Limited Purpose, Strategic Plan, and Wholesale Institutions Report," at https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/community/community/apprlp.html. |

| 22. |

See OCC, CRA: Community Development Loans, Investments, and Services, Fact Sheet, March 2014, at http://www.occ.gov/topics/community-affairs/publications/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-cra-loans.pdf. |

| 23. |

P.L. 102-233, the Resolution Trust Corporation, Refinancing, Restructuring, and Improvement Act of 1991, as amended by P.L. 102-550, the Housing and Community Development Act of 1992, gives positive CRA credit to losses resulting from branches transferred to minority- and women-owned institutions. P.L. 102-550 allows cooperation with minority- and female-owned institutions to receive such credit. For examples of various qualified community investments and technical assistance that can receive consideration for CRA credit, see OCC, Treasury; Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; FDIC, "Community Reinvestment Act; Interagency Questions and Answers Regarding Community Reinvestment; Notice," 78 Federal Register 69671-69680, November 20, 2013. |

| 24. |

On September 29, 2010, federal banking regulators implemented P.L. 110-315, 122 Stat. 3078, which allows CRA consideration to be given to banks that make low-cost education loans to LMI borrowers. See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, FDIC, OCC, Office of Thrift Supervision, "Agencies Issue Final Community Reinvestment Act Rule to Implement Provision of Higher Education Opportunity Act," press release, September 29, 2010, at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2010-10-04/pdf/2010-24737.pdf. |

| 25. |

For more information on remittances and recent regulatory developments, see CRS Report R43217, Remittances: Background and Issues for Congress, by Martin A. Weiss. |

| 26. |

A more extensive list of activities eligible for CRA credit consideration can be found at FDIC, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, OCC, "Agencies Release Final Revisions to Interagency Questions and Answers Regarding Community Reinvestment," press release, November 15, 2013, at http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/bcreg/20131115a.htm. |

| 27. |

The point system is illustrated at Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, "Community Reinvestment Act: Interagency Questions and Answers Regarding Community Reinvestment," 66 Federal Register 36639, July 12, 2001, pp. 33639-33640. |

| 28. |

See U.S. Department of Treasury, OCC; Federal Reserve System; FDIC, "Community Reinvestment Act; Interagency Questions and Answers Regarding Community Reinvestment; Notice," 74 Federal Register, January 6, 2009. |

| 29. |

See OCC, Federal Reserve System, FDIC, Office of Thrift Supervision, "Community Reinvestment Act Regulations and Home Mortgage Disclosure; Final Rules," 60 Federal Register 22156-22223, May 4, 1995. |

| 30. |

See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, OCC, FDIC, "Community Reinvestment Act Regulations," 70 Federal Register 44256-44270, August 2, 2005. |

| 31. |

Ibid. |

| 32. |

See OCC, Treasury; Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, FDIC, "Community Reinvestment Act Regulations," 84 Federal Register 71738-71740, December 30, 2019. |

| 33. |

See Derek Hyra et al., "The SBA's 7(a) Loan Program: A Flexible Tool for Commercial Lenders," Community Developments Insights, September 2008; and William Reeves, "FHA 203(k) Mortgage Insurance Program: Helping Banks and Borrowers Revitalize Homes and Neighborhoods," Community Developments Insights, May 2013. |

| 34. |

For a more detailed definition of a PWI, see OCC, Public Welfare Investments, Fact Sheet, July 2011, at http://www.occ.gov/topics/community-affairs/publications/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-public-welfare-investments.pdf; and 12 C.F.R. §§24.2, 24.3, and 24.6 at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2013-title12-vol1/pdf/CFR-2013-title12-vol1-part24.pdf. |

| 35. |

Community development includes "activities that promote economic development by [the] financing [of] business or farms that meet the size eligibility standards consistent with Small Business Administration's size limitations for Development Company and Small Business Investment Company programs." See Definition of Community Development, Federal Reserve—12 C.F.R. §228.12, at http://www.phil.frb.org/community-development/events/development-financing-in-rural-pa/presentations/cca_rural-111606_definitions.pdf. |

| 36. |

See OCC, Activities Permissible for a National Bank, Cumulative, April 2012, at http://www.occ.gov/publications/publications-by-type/other-publications-reports/bankact.pdf. |

| 37. |

Under PWI investment authority, banks can make investments that are not otherwise expressly permitted under the National Bank Act. See OCC, Public Welfare Investments, Fact Sheet, July 2011, at http://www.occ.gov/topics/community-affairs/publications/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-public-welfare-investments.pdf; and 12 C.F.R. §§24.2, 24.3, and 24.6 at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CFR-2013-title12-vol1/pdf/CFR-2013-title12-vol1-part24.pdf. |

| 38. |

Supervised banks are restricted as to how much they are allowed to lend to a single borrower. The lending limit applies to the banks' unimpaired capital and unimpaired surplus, and higher amounts may be permitted for different types of loans. Generally speaking, unimpaired capital and unimpaired surplus refer to a bank's Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital, which includes its allowance for loan and lease losses, minus any nonmarketable intangible assets. For the legal definitions of unimpaired capital and surplus, see Part 215—Loans to Executive Officers, Directors, and Principal Shareholders of Member Banks (Regulation O), 59 Federal Register 8837, February 24, 1994, at http://www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/rules/7500-1300.html. |

| 39. |

These areas are available from the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council. For example, see the 2012 List of Distressed or Underserved Nonmetropolitan Middle-Income Geographies at https://www.ffiec.gov/cra/pdf/2012distressedorunderservedtracts.pdf. |

| 40. |

Federal disaster declarations listing affected counties are available from the Federal Emergency Management Agency website at http://www.fema.gov/news/disasters.fema. |

| 41. |

See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, FDIC, OCC, "Banking Agencies Issue Final community Reinvestment Act Rules," press release, July 19, 2005, at http://www.federalreserve.gov/BoardDocs/press/bcreg/2005/20050719/default.htm. |

| 42. |

Regulators may withhold or prorate CRA credits for indirect investments to ensure they are applied to low-income community developments. For example, suppose a project expected to be constructed or completed within a bank's assessment area is relocated elsewhere (outside of the assessment area). A bank is unlikely to receive CRA credits for any prior investment in the securities to facilitate the project. For more information, see U.S. Department of Treasury, OCC; Federal Reserve System; FDIC, "Community Reinvestment Act; Interagency Questions and Answers Regarding Community Reinvestment; Notice," 74 Federal Register, January 6, 2009. |

| 43. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Financial Services, The Community Reinvestment Act, Testimony by Sandra F. Braunstein, director, Division of Consumer and Community Affairs, 110th Cong., 2nd sess., February 13, 2008, at http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/braunstein20080213a.htm. |

| 44. |

The text of this joint ruling is available at http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/press/bcreg/2005/20050719/attachment.pdf. |

| 45. |

See OCC, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, and FDIC, "Community Reinvestment Act Regulations," at http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/press/bcreg/2005/20050719/attachment.pdf. |

| 46. |

See Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Community Reinvestment: Does Your Bank Measure Up?, at http://www.frbatlanta.org/pubs/cra/community_reinvestment_does_your_bank_measure_up_printable.cfm. |

| 47. |

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, The Performance and Profitability of CRA-Related Lending, at http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/surveys/craloansurvey/cratext.pdf. |

| 48. |

For studies on technological developments and credit availability, see Robert B. Avery, et al., "Credit Risk, Credit Scoring, and the Performance of Home Mortgages," Federal Reserve Bulletin, vol. 82, no. 7 (July 1996), pp. 621-648; Susan Wharton Gates, Vanessa Gail Perry, and Peter M. Zorn, "Automated Underwriting in Mortgage Lending: Good News for the Underserved?," Housing Policy Debate, vol. 13, no. 2 (2002), pp. 369-391; Michael S. Barr, "Credit Where It Counts: The Community Reinvestment Act and Its Critics," New York University Law Review, vol. 80, no. 2 (2005), pp. 513-652; and John Taylor and Josh Silver, "A Framework for Revisiting the CRA," in Revisiting the CRA: Perspectives on the Future of the Community Reinvestment Act, Federal Reserve Banks of Boston and San Francisco, February 2009, pp. 2-7, at http://www.frbsf.org/community-development/files/cra_30_years_wealth_building.pdf. |

| 49. |

For example, see William C. Apgar and Mark Duda, "The Twenty-Fifth Anniversary of the Community Reinvestment Act: Past Accomplishments and Future Regulatory Challenges," Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Economic Policy Review, vol. 9, no. 2 (June 2003), at http://www.newyorkfed.org/research/epr/03v09n2/0306apga.pdf. |

| 50. |