Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund: Programs and Policy Issues

As communities face a variety of economic challenges, some are looking to local banks and financial institutions for solutions that address the specific development needs of low-income and distressed communities. Community development financial institutions (CDFIs) provide financial products and services, such as mortgage financing for homebuyers and not-for-profit developers; underwriting and risk capital for community facilities; technical assistance; and commercial loans and investments to small, start-up, or expanding businesses. CDFIs include regulated institutions, such as community development banks and credit unions, and nonregulated institutions, such as loan and venture capital funds.

The Community Development Financial Institutions Fund (Fund), an agency within the Department of the Treasury, administers several programs that encourage the role of CDFIs and similar organizations in community development. Nearly 1,000 financial institutions located throughout all 50 states and the District of Columbia are eligible for the Fund’s programs to provide financial and technical assistance to meet the needs of businesses, homebuyers, community developers, and investors in distressed communities. In addition, the Fund certifies entities and designates areas that are eligible for the New Markets Tax Credit and Opportunity Zone (OZ) tax incentives, which were recently enacted by the 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97).

This report begins by describing the Fund’s history, current appropriations, and each of its programs. A description of the Fund’s process of certifying certain financial institutions to be eligible for the Fund’s program awards follows. The next section provides an overview of each program’s purpose, use of award proceeds, eligibility criteria, and relevant issues for Congress.

The final section analyzes four policy considerations of congressional interest regarding the Fund and the effective use of federal resources to promote economic development. First, it analyzes the debate on targeting development assistance toward particular geographic areas or low-income individuals generally. Prior research indicates that geographically targeted assistance, like the Fund’s programs, may increase economic activity in the targeted place or area. However, this increase may be due to a shift in activity from an area not eligible for assistance.

Second, it analyzes the debate over targeting economic development policies toward labor or capital. The Fund’s programs primarily rely on the latter, such as encouraging lending to small businesses rather than targeting labor, such as wage subsidies. Research indicates the benefits of policies that reduce capital costs in a targeted place may not be passed on to local laborers in the form of higher wages or increased employment.

Third, it examines whether the Fund plays a unique role in promoting economic development and if it duplicates, complements, or competes with the goals and activities of other federal, state, and local programs. Although CDFIs are eligible for other federal assistance programs and other agencies have a similar mission as the Fund, the Fund’s programs have a particular emphasis on encouraging private investment and building the capacity of private financial entities to enhance local economic development

Fourth, it examines assessments of the Fund’s management. Some argue that the Fund’s programs are not managed in an effective manner and are not held to appropriate performance measures. Others contend that the Fund is fulfilling its mission and achieving its performance measures.

Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund: Programs and Policy Issues

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Legislative Origins and Current Structure

- Budget

- Entity Certification

- Certified Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs)

- Certified Community Development Entities (CDEs)

- Qualified Opportunity Funds (QOFs)

- Programs

- CDFI Program

- Native American CDFI Assistance

- Small and Emerging CDFI Assistance

- Healthy Food Financing Initiative

- New Markets Tax Credit

- Bank Enterprise Award

- Opportunity Zone Tax Incentives

- Bond Guarantee Program

- Capital Magnet Fund

- Policy Considerations

- How Effective Are Geographically Targeted Economic Development Policies?

- Should Economic Development Policies Target Capital or Labor?

- Do the Fund's Programs Duplicate Other Government Efforts?

- Is the CDFI Fund Managed Effectively?

Figures

Tables

Summary

As communities face a variety of economic challenges, some are looking to local banks and financial institutions for solutions that address the specific development needs of low-income and distressed communities. Community development financial institutions (CDFIs) provide financial products and services, such as mortgage financing for homebuyers and not-for-profit developers; underwriting and risk capital for community facilities; technical assistance; and commercial loans and investments to small, start-up, or expanding businesses. CDFIs include regulated institutions, such as community development banks and credit unions, and nonregulated institutions, such as loan and venture capital funds.

The Community Development Financial Institutions Fund (Fund), an agency within the Department of the Treasury, administers several programs that encourage the role of CDFIs and similar organizations in community development. Nearly 1,000 financial institutions located throughout all 50 states and the District of Columbia are eligible for the Fund's programs to provide financial and technical assistance to meet the needs of businesses, homebuyers, community developers, and investors in distressed communities. In addition, the Fund certifies entities and designates areas that are eligible for the New Markets Tax Credit and Opportunity Zone (OZ) tax incentives, which were recently enacted by the 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97).

This report begins by describing the Fund's history, current appropriations, and each of its programs. A description of the Fund's process of certifying certain financial institutions to be eligible for the Fund's program awards follows. The next section provides an overview of each program's purpose, use of award proceeds, eligibility criteria, and relevant issues for Congress.

The final section analyzes four policy considerations of congressional interest regarding the Fund and the effective use of federal resources to promote economic development. First, it analyzes the debate on targeting development assistance toward particular geographic areas or low-income individuals generally. Prior research indicates that geographically targeted assistance, like the Fund's programs, may increase economic activity in the targeted place or area. However, this increase may be due to a shift in activity from an area not eligible for assistance.

Second, it analyzes the debate over targeting economic development policies toward labor or capital. The Fund's programs primarily rely on the latter, such as encouraging lending to small businesses rather than targeting labor, such as wage subsidies. Research indicates the benefits of policies that reduce capital costs in a targeted place may not be passed on to local laborers in the form of higher wages or increased employment.

Third, it examines whether the Fund plays a unique role in promoting economic development and if it duplicates, complements, or competes with the goals and activities of other federal, state, and local programs. Although CDFIs are eligible for other federal assistance programs and other agencies have a similar mission as the Fund, the Fund's programs have a particular emphasis on encouraging private investment and building the capacity of private financial entities to enhance local economic development

Fourth, it examines assessments of the Fund's management. Some argue that the Fund's programs are not managed in an effective manner and are not held to appropriate performance measures. Others contend that the Fund is fulfilling its mission and achieving its performance measures.

Introduction

|

Types of CDFIs

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, "Community Development Financial Institutions: A Unique Partnership for Banks," Community Development Special Issue, 2011. |

Community development financial institutions (CDFIs) have been using small-scale and locally developed strategies to stabilize and advance low-income and financially underserved communities for decades. CDFIs are specialized financial institutions that work in market niches that are underserved by traditional financial institutions.1 They provide a range of financial products and services in economically distressed markets, such as mortgage financing for low-income and first-time homebuyers and not-for-profit developers, flexible underwriting and risk capital for needed community facilities, technical assistance, and commercial loans and investments to small start-up or expanding businesses in low-income areas. CDFIs exist in both rural and urban communities. CDFIs include regulated institutions, such as community development banks and credit unions, and nonregulated institutions, such as loan and venture capital funds.

Some stakeholders are concerned that a shortage of capital from CDFIs will reduce opportunities for new entrepreneurs to establish a business, existing businesses to expand and hire new workers, and consumers to acquire the credit they need to buy or make improvements to a property. Others believe that these goals can be better served through other public policy or private means.

This report begins by describing the Community Development Financial Institutions Fund's (Fund's) history, current appropriations, and each of its programs. The next section of the report analyzes four policy considerations of congressional interest regarding the Fund and the effective use of federal resources to promote economic development. It analyzes the reasons why some individuals may choose not to locate in an underdeveloped community, why government policies may be justified in encouraging economic activity to relocate to underdeveloped communities, and which policies are more successful in addressing aspects of underdevelopment. Lastly, this report examines the Fund's programs and management to see if they represent an effective and efficient government effort to promote economic development in low-income and distressed communities.

Legislative Origins and Current Structure

The Riegle Community Development and Regulatory Improvement Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-325) established the Fund to assist CDFIs in providing coordinated development strategies across various sectors of the local economy. These coordinated development strategies are designed to encourage small businesses, affordable housing, the availability of commercial real estate, and human development.2 The legislation intended to improve the supply of capital, credit, private investment, and development services in economically distressed areas. In proposing the Fund, President Clinton stated that "by ensuring greater access to capital and credit, we will tap the entrepreneurial energy of America's poorest communities and enable individuals and communities to become self-sufficient."3

Although the Riegle Act created the Fund as a wholly owned, independent government corporation, a supplemental appropriations bill moved the Fund into the Department of the Treasury (Treasury) in 1995.4 The Fund was moved within Treasury because of its focus on financial institutions and because other bank regulatory agencies (i.e., the Office of Thrift Supervision and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency) were already located within the agency.5 The Fund is a component of the programs of the Under Secretary's Office of Domestic Finance, and it is directly under the Assistant Secretary for Financial Institutions.6

The Fund is headed by a director, who is appointed by the Secretary of the Treasury and not subject to Senate confirmation. Initially, the director served a three-year term. However the Fund was led by approximately 10 directors in its first 15 years. To bring greater stability to the Fund's leadership, the Secretary of the Treasury made the director's position into a career appointment in 2010, meaning there are no limits on the length of the director's term. Annie Donovan has been Director of the Fund since December 2014.7

By statute, the Fund also has a 15-member Community Development Advisory Board. The board members include the Secretaries of Agriculture, Commerce, Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Interior, and the Treasury; the Administrator of the Small Business Administration (SBA); and nine private citizens appointed by the President. The advisory board's function is to advise the Director of the Fund on policies regarding the Fund's activities. The advisory board is not allowed, by law, to advise the Fund on the granting or denial of any particular application for monetary or nonmonetary awards.

Although the Fund is organized within Treasury's Office of Domestic Finance, in recent years Congress has provided the Fund with its own budget authority line in annual financial services appropriations bills.8 These appropriations go toward the Fund's administration, programs, and program awards. The Fund's appropriations cover administration of approvals for allocations of the New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC); however, the actual tax credit is awarded through the Internal Revenue Code, not through the Fund's appropriations.

Budget

As shown in Table 1, the Fund's total enacted budget authority for FY2017 was $233.1 million. Of this $233.1 million, 66% ($153.1 million) was appropriated for the Fund's core CDFI financial and technical assistance programs; 10% ($23.6 million) was appropriated for administration of the Fund's programs, including the NMTC; 8% ($19.0 million) was appropriated for the Bank Enterprise Award (BEA) program; and the remaining 16% ($37.4 million) was appropriated for set-asides for other specific programs.

Table 1. Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund

Programs Funding, FY2013 to FY2018 (Request)

(in millions of dollars)

|

Budget Activity |

FY13 |

FY14 |

FY15 |

FY16 |

FY17 |

FY18 |

|

CDFI Program |

138.4 |

146.4 |

152.4 |

153.4 |

153.1 |

0.0 |

|

Administration |

21.8 |

24.6 |

23.1 |

23.6 |

23.6 |

14.0 |

|

Healthy Food Financing Initiative (HFFI) |

20.8 |

22.0 |

22.0 |

22.0 |

22.0 |

0.0 |

|

Bank Enterprise Award (BEA) Program |

17.1 |

18.0 |

18.0 |

19.0 |

19.0 |

0.0 |

|

Native American CDFI Assistance (NACA) |

11.4 |

15.0 |

15.0 |

15.5 |

15.5 |

0.0 |

|

Total Budget Authority |

209.4 |

226.0 |

230.5 |

233.5 |

233.1 |

14.0 |

Sources: U.S Department of the Treasury, Community Development Financial Institutions Fund FY2018 Congressional Justification for Appropriations and Annual Performance Plan, p. 4, at https://www.treasury.gov/about/budget-performance/CJ18/13.%20CDFI%20Fund%20-%20FY%202018%20CJ.pdf; U.S Department of the Treasury, Community Development Financial Institutions Fund FY2017 President's Budget, February 9, 2016, p. 2, at https://www.treasury.gov/about/budget-performance/CJ17/13.%20CDFI%20FY%202017%20CJ.PDF; and U.S Department of the Treasury, Community Development Financial Institutions Fund FY2016 President's Budget, February 2, 2015, at http://www.treasury.gov/about/budget-performance/CJ16/12.%20CDFI%20FY%202016%20CJ.pdf.

Note: Administration costs include administration of the New Markets Tax Credit. Total budget authority numbers might not add up to program totals due to rounding.

In his FY2018 budget blueprint, President Trump requested $14 million to fund administration costs. This funding would be used to manage past awards and monitor compliance.9 Funding would also include administration of new award rounds for two zero credit subsidy programs: the NMTC and Bond Guarantee program. The budget blueprint calls for eliminating funding for the Fund's four discretionary grant and loan programs (i.e., CDFI Program, HFFI, BEA Program, and NACA) and new allocations into the Capital Magnet Fund.

Entity Certification

To be eligible for certain Fund-related programs, an organization must be certified as a CDFI, Community Development Entity (CDE), or Qualified Opportunity Fund (QOF). CDFIs are eligible for CDFI Program FA and TA. CDEs are eligible for the NMTC. QOFs are eligible for Opportunity Zone (OZ) tax incentives.

Certified Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs)

CDFI certification is a designation conferred by the Fund and a requirement for accessing financial award assistance from the Fund through the CDFI program, Native American CDFI Assistance (NACA) programs, and certain benefits under the BEA program to support an organization's established community development financing programs.

An organization that does not meet each of the certification eligibility requirements at the time of application for technical assistance is still eligible to apply for and receive technical assistance. This may occur if the Fund determines that the organization's application materials provide a realistic course of action to ensure that it will meet each of the certification requirements within two years of entering into an assistance agreement with the Fund.

To be eligible for CDFI certification, the applicant must

- be a legal entity;

- have a primary mission of promoting community development;

- primarily provide financial products, development services, or other similar financing in arms-length transactions;

- primarily serve (direct at least 60% of financial product activities to) one or more geographic investment areas meeting certain poverty or income standards, low-income targeted populations, or other targeted populations that lack adequate access to capital and historically have been denied credit;

- provide development services, such as credit or home-buying counseling, in conjunction with financial products;

- maintain accountability to defined target markets through representation on a governing or advisory board or through outreach activities; and

- be a nongovernment entity and not under the control of any government entity (except tribal governments).10

|

|

Source: Community Development Financial Institutions Fund, at https://www.cdfifund.gov/programs-training/certification/cdfi/Pages/default.aspx. |

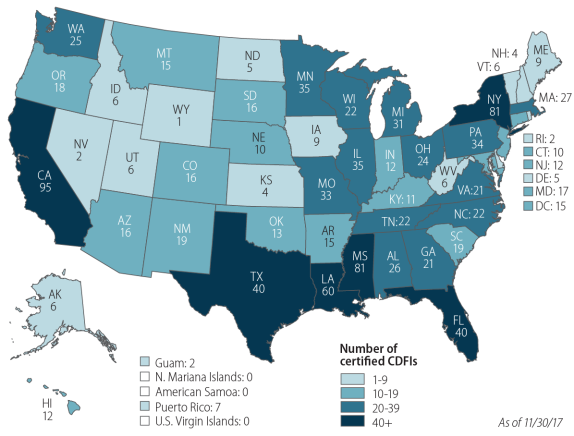

As of November 31, 2017, there were 1,011 certified CDFIs.11 As shown in Figure 1, at least one CDFI is located in each of the 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, and Puerto Rico. California and New York contain more certified CDFIs than any other U.S. state or territory. Of the 1,011 certified CDFIs, 558 (51%) are loan funds, 304 (28%) are credit unions, 137 (12%) are banks or thrifts, 86 (8%) are depository institution holding companies, and 16 (1%) are venture capital funds.12 Of the 1,011 certified CDFIs, 73 (7%) are certified Native American CDFIs.

Certified Community Development Entities (CDEs)

CDE certification is required to receive an NMTC allocation. A certified CDE is a domestic corporation or partnership that is an intermediary vehicle for the provision of loans, investments, or financial counseling in low-income communities (LICs). CDEs use the NMTC to encourage investors to make equity investments in the CDE or its subsidiaries. To be eligible for CDE certification, the applicant must

- be a legal entity and a domestic corporation or partnership for federal tax purposes;

- have a primary mission of serving or providing investment capital to low-income communities or low-income individuals and target at least 60% of activities to these groups; and

- maintain accountability to low-income communities through representation on a governing or advisory board.13

|

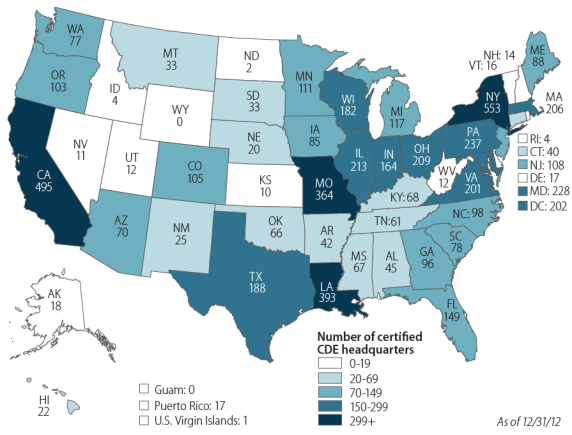

Figure 2. Certified Community Development Entities (CDEs), by Location |

|

|

Source: Data previously posted on the CDFI Fund website. |

As of July 31, 2012, there were 5,780 certified CDEs (including their subsidiaries) located throughout the United States, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.14 As shown in Figure 2, California and New York also contained more certified CDEs than any other U.S. state or territory.

Qualified Opportunity Funds (QOFs)

The 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97) created a new set of tax incentives for entities that are certified by the Fund as being "Qualified Opportunity Funds" (QOFs).15 QOFs are defined in P.L. 115-97 as:

...any investment vehicle which is organized as a corporation or partnership for the purpose of investing in qualified opportunity zone property (other than another qualified opportunity fund) that holds at least 90% of its assets in qualified opportunity zone property...

"Qualified Opportunity Zone (OZ) property" can be stock or partnership interest in a business located within a qualified OZ or tangible business property located in a qualified OZ. Qualified OZ property must have been acquired by the QOF after December 31, 2017. For each month that a QOF fails to meet the 90% requirement it must pay a penalty equal to the excess of the amount equal to 90% of its aggregate assets divided by the aggregate amount of qualified OZ property held by QOF multiplied by an underpayment rate (short term Federal interest rate plus three percentage points). There is an exception from this general penalty for reasonable cause. P.L. 115-97 authorizes the Fund to promulgate regulations and rules regarding specific processes for QOF certification.

Programs

The Fund's official mission is to increase economic opportunity and promote community development investments in low-income and distressed communities in the United States. To carry out this mission, the Fund is composed of several programs that address multiple needs of distressed communities. These programs encourage qualified entities to provide financial and technical assistance to meet the needs of local businesses, potential homebuyers, community developers, and potential investors in low-income and distressed communities. The Fund's range of incentives includes equity investment in program awardees, tax credits, grants, loans, and deposits and credit union shares in insured CDFIs and state-insured credit unions.16

All of the Fund's programs use geographically targeted incentives intended to increase community development in underserved and distressed communities, where certain types of economic activity might not otherwise occur. Ideas for geographically targeted community development policies were a feature of federal policy debates throughout the 1980s and early 1990s.17 Despite bipartisan support for these policies at the time, they were not widely implemented at the federal level until the Clinton Administration.18

CDFI Program

The Community Development Banking and Financial Institutions Act of 1994 in the Riegle Community Development and Regulatory Improvement Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-325) authorized the Fund's core CDFI program. The CDFI program provides two types of monetary awards, financial assistance (FA) and technical assistance (TA). These awards are given to CDFIs to build their capacity to serve low-income people and communities that lack access to affordable financial products and services.19

To be eligible for an FA award, a CDFI must be certified by the Fund before it applies for the award. Prospective applicants that are not yet certified must submit a separate certification application to be considered for an FA award during a funding round. Both certified and noncertified CDFIs are eligible to apply for TA awards. However, noncertified organizations must be able to become certified within two years after receiving a TA award.

In evaluating and selecting applicants for awards, the Fund evaluates the applicant's likelihood of meeting its goals as described in a required comprehensive business plan. The Fund also considers the applicant's prior history of servicing distressed communities, operational capacity, financial track record, and other attributes.20

|

Minimum Requirements for

Source: 12 C.F.R. §1806.200(b). |

Activities eligible for program awards must target a distressed community, which is defined by two requirements. First, the community (investment area) must meet minimum area requirements. The community must be a continuous area of general local government that (1) has a population of at least 4,000, if located in a metropolitan statistical area; (2) has a population of at least 1,000, in nonmetropolitan areas; or (3) is located entirely within an Indian reservation.21

Second, at least 30% of eligible residents in the community must have incomes that are less than the national poverty level, as published by the U.S. Bureau of the Census, and the community must have an unemployment rate that is at least 1.5 times greater than the national average, as determined by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics' most recent data. In addition, the Fund may specify other requirements in a program's applicable notice of funds availability (NOFA).22 The Fund's online resource, Fund Mapping System (CIMS), designates which localities either fully qualify or partially qualify as distressed communities, based on the three criteria.23

If the community does not meet the individual minimum area requirements, the applicant may select two or more geographic units which, in the aggregate, meet the minimum area eligibility requirements, provided none of the geographic units has a poverty rate less than 20%.24

As of FY2017, the Fund makes awards up to $2 million to certified CDFIs under the FA component of the CDFI program.25 A CDFI may use an FA award for lending, investing, enhancing liquidity, or other means of financing

- commercial facilities that promote revitalization, community stability, or job creation or retention;

- businesses that provide jobs to, are owned by, or enhance the availability of products and services to low-income individuals;

- housing that is principally affordable to low-income persons, with some exceptions;

- the provision of consumer loans; or

- other businesses or activities as requested by the applicant and deemed appropriate by the Fund.26

As of FY2017, the Fund awards grants of up $125,000 to certified CDFIs and established entities seeking to become certified under the TA component of the CDFI program.27 TA awards are intended to build a CDFI's capacity to provide affordable financial products and services to low-income communities and families. TA grants may be used for a variety of purposes, including

- purchasing equipment, materials, or supplies;

- procuring for consulting or contracting services;

- paying the salaries and benefits of certain personnel;

- training staff or board members; and

- conducting other activities deemed appropriate by the Fund.28

FA and TA awards are both generally subject to two restrictions. First, the Fund typically requires an applicant to demonstrate that it can match from a nonfederal source, dollar-for-dollar, the amount of money that it is requesting from the Fund. With regard to FA awards, the Fund is authorized to make awards to applicants in a like form to the matching funds secured by the awardee.29 For example, the Fund can only match a nonfederal grant with an FA grant—not a loan. Second, the Fund generally limits any one entity or its affiliates from receiving more than $5 million in awards from the Fund within a three-year period.30

However, restrictions on the Fund's awards have been subject to temporary legislative changes. For example, the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act (ARRA) of 2009 (P.L. 111-5) waived the nonfederal, dollar-for-dollar matching requirement for three years.31 Thus, the Fund did not require awards in FY2009, FY2010, and FY2011 to be matched by nonfederal sources.32 The matching requirement returned for awards in FY2012 for fund programs that did not receive a congressional wavier.33

The Fund awarded 224 FA awards and 41 TA awards totaling $171.1 million to 265 organizations in FY2017.34 The organizations were headquartered in 46 states and the District of Columbia.

Native American CDFI Assistance

The origin of the Native American CDFI Assistance (NACA) component of the CDFI program dates back to the Riegle Act of 1994. The Riegle Act mandated that the Fund conduct a study of lending and investment practices on Indian reservations. The study was directed to identify and determine the impact of private-financing barriers on Native American populations.35 Since the November 2001 release of the Native American Lending Study, the Fund certifies Native CDFIs and provides assistance through the CDFI program's authority. These programs are designed to reduce barriers preventing access to credit, capital, and financial services in Native American, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian communities (collectively referred to as Native Communities).36

The Fund receives a separate appropriation for the NACA component of the CDFI program. Under the NACA component of the CDFI program, the Fund issues FA and TA awards to organizations with the primary mission of increasing access to capital in Native Communities. In addition, the NACA component provides TA grants to certified Native CDFIs, emerging Native CDFIs, and sponsoring entities (see below). TA awards may be used by the recipient to become certified as a Native CDFI or to create a new Native CDFI.

A CDFI must be certified by the Fund as one of three types of entities to become eligible for NACA's FA and TA awards:37

- certified Native CDFIs, organizations that direct at least 50% of their activities toward serving Native Communities;

- emerging Native CDFIs, organizations that demonstrate to the satisfaction of the Fund that they have a plan to achieve Native CDFI certification within a reasonable timeframe; or

- sponsoring entities, organizations (typically tribes or tribal entities) that pledge to create separate legal entities that will eventually become certified as Native CDFIs.

Table B-1 summarizes the locations of Certified Native CDFIs by state. Hawaii, Oklahoma, and South Dakota each contain more certified Native CDFIs than any other U.S. state.

Small and Emerging CDFI Assistance

The Small and Emerging CDFI Assistance (SECA) component of the CDFI program is designed to assist small or emerging CDFIs. It provides the same type of FA and TA awards as the general CDFI program. It distinguishes small or emerging CDFIs from other CDFIs using two eligibility criteria, as announced in the annual notice of funds availability. Since FY2009, the Fund's appropriations have waived the matching funds requirement under the general CDFI Program for SECA FA applicants.38 For FY2017 awards, a certified CDFI met the eligibility criteria of being a small or emerging CDFI if it had financial holdings below certain caps (based on the respective type of financial institution) or if it began operations after January 1, 2013.39

Awards provided through the SECA application are subject to caps. For FY2017, these caps include $700,000 in general FA funds and up to $125,000 in TA funds for capacity-building activities.40

Healthy Food Financing Initiative

The Fund has used its authority within its CDFI program to support the Healthy Food Financing Initiative (HFFI), which began in FY2011. The Fund's HFFI is part of a multi-agency HFFI, involving Treasury, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The HFFI represents the federal government's effort to expand the supply and demand for nutritious foods, including increasing the distribution of agricultural products, developing and equipping grocery stores, and strengthening producer-to-consumer relationships. Through its role in the HFFI, the Fund provides grants for organizations serving low-income neighborhoods with limited access to affordable and nutritious food.

New Markets Tax Credit

Congress established the New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC) program as part of the Community Renewal Tax Relief Act of 2000, contained within the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2001 (P.L. 106-554), to encourage investors to make investments in impoverished, low-income communities (LICs) that traditionally lack access to capital. The NMTC is designed to increase private investment in LICs, where conventional access to credit and investment capital for developing small businesses, creating and retaining jobs, and revitalizing neighborhoods is often limited.41 The NMTC is a nonrefundable tax credit intended to encourage qualified investment groups to support CDEs that operate in eligible LICs.42 Although the NMTC is credited through the federal tax code, the Fund is responsible for awarding the tax credit allocations to eligible CDEs through a competitive award process. The credit provided to the investor totals 39% of the amount of the investment made in a CDE and is claimed over a seven-year credit allowance period.43 In each of the first three years, the investor receives a credit equal to 5% of the total amount paid for the stock or capital interest at the time of purchase. For the final four years, the value of the credit is 6% annually. Investors must retain their interest in a qualified equity investment throughout the seven-year period or risk forfeiture of that interest.44

Under the tax code's NMTC provisions, only eligible investments in qualifying LICs can receive the NMTC. Qualifying LICs include census tracts that have at least one of the following criteria: (1) a poverty rate of at least 20%; (2) a median family income below 80% of the greater of the statewide or metropolitan area median family income if the LIC is located in a metropolitan area; or (3) a median family income below 80% of the median statewide family income if the LIC is located outside a metropolitan area. As defined by these criteria, about 39% of the nation's census tracts covering nearly 36% of the U.S. population are eligible for the NMTC.45 In addition, designated targeted populations may be treated as LICs. As a result of the definition of qualified LICs, virtually all of the country's census tracts are potentially eligible for the NMTC.46

Qualified investment groups can apply to the Fund for an allocation of the NMTC. CDEs seek individuals who can benefit from tax preferences to make qualifying equity investments in the CDE.47 The CDE then makes equity investments in LICs and low-income community businesses, all of which must be qualified. After the CDE is awarded a tax credit allocation, the CDE is authorized to offer the tax credits to private equity investors in the CDE.

The Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-312) extended NMTC authorization through 2011 at $3.5 billion per year. The American Taxpayer Relief Act (ATRA; P.L. 112-240) extended the NMTC through 2012 and 2013 with an authority of $3.5 billion per year. The Tax Increase Prevention Act of 2014 (P.L. 113-295) extended the NMTC through 2014 at $3.5 billion. The Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes (PATH) Act (Division Q of P.L. 114-113) extended the NMTC authorization from 2015 through 2019 at $3.5 billion per year.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has issued several reports examining the NMTC's overall performance and ability to benefit certain types of LICs. A 2007 GAO report contains survey results from a sample of NMTC recipients suggesting that the NMTC influenced the decisions of investors to invest in LICs.48 GAO published a 2009 report responding to congressional concerns about the low success rate of minority-owned CDEs in obtaining NMTC allocations. GAO found that although a CDE's resources and experience are important factors in successfully obtaining an NMTC allocation, minority status is associated with a lower probability of receiving an allocation, when controlling for other factors. GAO could not determine why this relationship exists or whether any actions (or lack of) by the Department of the Treasury contributed to minority CDEs' lower probability of success, given that the Fund provides assistance that is available to all CDEs that do not receive awards detailing some of the weaknesses in its applications.49 In a 2012 report, GAO concluded that although the NMTC directed most awards and tax credits to metropolitan areas, it generally met proportionality goals of nonmetropolitan areas.50 Another GAO report released in 2012 reported that the effects of the NMTC are difficult to assess because of information gaps in the collection of tax data.51

In addition, GAO reports have focused on the NMTC's complex application and administration and have provided recommendations to make the program simpler and more accessible to those in LICs. For example, a 2010 GAO report noted that the complexity of NMTC transaction structures appears to make it more difficult for CDEs to execute smaller transactions and results in less equity ending up in low-income community businesses than would likely end up there were the transaction structures simplified.52 In a 2011 report, GAO suggested that Congress convert at least part of the NMTC to a grant program to increase the amount of federal subsidy reaching businesses in impoverished LICs.53 In a 2014 report, GAO found that the financial structures of NMTC investments have become more complex and less transparent over time.54 The complexity is due, in part, to combining financing from multiple sources (including multiple government-based development incentives) and can sometimes lead to higher fees or interest rates charged by CDEs.55

Bank Enterprise Award

The Bank Enterprise Award (BEA) was originally authorized by the Bank Enterprise Act of 1991 in the Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 1992 (P.L. 102-142). Prior to the creation of the Fund, the BEA was administered by the Comptroller of the Currency and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Section 114 of the Riegle Community Development and Regulatory Improvement Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-325) moved the BEA under the operations of the Fund.

The Fund's BEA program provides formula-based grants to FDIC-insured banks and thrifts to expand investments in CDFIs and to increase lending, investment, and service activities within economically distressed communities. The Fund measures increases in an applicant's lending, investment, and service activities relative to a baseline of similar, qualified activities conducted by the applicant in the previous application cycle. BEA rewards are retrospective, awarding applicants for activities they have already completed, in contrast to the Fund's primary CDFI program, which typically awards applicants based on their plans for the future.56

The BEA provides formula-based grants to qualified banks and thrifts based on three categories:

- CDFI-related activities include equity investments (e.g., grants, stock purchases, purchases of partnership interests, or limited liability company membership interests), equity-like loans, and support activities (e.g., loans, deposits, or technical assistance), to certified CDFIs.

- Distressed community financing activities include loans or investments for home mortgages, housing development, home improvement, commercial real estate development, small businesses, and education financing in distressed communities.

- Service activities include the provision of financial services (e.g., check-cashing or money order services, electronic transfer accounts, and individual development accounts).57

FDIC-insured financial institutions that are dedicated to financing and supporting economic development in qualified communities are eligible for the BEA. No applicant may receive a BEA if it has (1) an application pending for assistance under the current round of the awards under the CDFI program; (2) been awarded assistance from the Fund under the CDFI program within the 12-month period prior to the date the Fund selects the applicant to receive a BEA; or (3) ever received assistance under the CDFI program for the same activities for which it is seeking a BEA.58 Applicants may apply for both a CDFI program award and a BEA program award in a given year; however, receiving a CDFI program award removes an applicant from eligibility for a BEA in the same year.59

In FY2016, 102 depository institutions received $18.8 million in BEA program awards.60

According to a GAO report, the Fund's authorizing statute places no restrictions on how BEA recipients may use their award.61 In this same report, the Fund agreed with GAO's interpretation of its authorizing statute.62 However, the Fund changed the terms of the program's award agreements in 2009.63 Recipients must now use the award, or an amount equivalent to the award amount, for BEA-qualified activities in a distressed community.64

The BEA program's effect on investment in distressed communities is the topic of multiple GAO reports to Congress. In 1998, GAO reported that, according to the Fund, most of the 1996 awardees reported using their awards to further the objectives of the BEA program even though the program's authorizing legislation did not place restrictions on the use of the awards.65 Each of GAO's five case study banks also reported using its award money to expand its existing investments in community development.66 In a 2006 report, GAO concluded that the extent to which the BEA program may provide banks with incentives to increase their investments in CDFIs and lending in distressed communities is difficult to determine, but available evidence GAO reviewed suggested that the program's impact has likely not been significant. Award recipients GAO interviewed said the BEA program lowers bank costs associated with investing in a CDFI or lending in a distressed community, allowing for increases in both types of activities. However, other economic and regulatory incentives also encourage banks to undertake award-eligible activities, and it is difficult to isolate and distinguish these incentives from those of a BEA award.67 Treasury disputed GAO's findings and questioned GAO's methodology in evaluating the BEA program.

Opportunity Zone Tax Incentives

The 2017 tax revision (P.L. 115-97) authorized Opportunity Zone (OZ) tax incentives for investments held by QOFs in qualified OZs. The Fund will designate census tracts that will be eligible for OZ tax incentives and certify qualified opportunity funds (QOFs) that will be eligible to claim tax incentives for eligible activities within an OZ.

To become a qualified OZ, the chief executive officer (e.g., governor) of the state must nominate, in writing, census tracts to the Secretary of the Treasury.68 A nominated tract must be either (1) a qualified LIC, using the same criteria as eligibility under the NMTC,69 or (2) a census tract that is contiguous with an LIC if the median family income of the tract does not exceed 125% of that contiguous LIC. Qualified OZ designations are in effect for 10 years.

Additionally P.L. 115-97 limits the number of census tracts within a state that can be designated as a qualified OZ based on the following criteria:

- If the number of LICs in a state is less than 100, then a total of 25 census tracts may be designated as qualified OZs.

- If the number of LICs in a state is 100 or more, then the maximum number of census tracts that may be designated as qualified OZs is equal to 25% times the total number of LICs.

- No more than 5% of the census tracts in a state can be designated as a qualified opportunity zone.

P.L. 115-97 provides two main tax incentives to encourage investment in qualified OZs.70 First, it allows for the temporary deferral of inclusion in gross income of capital gains that are reinvested in a qualified OZ. If the investment in the QOF is held by the taxpayer for at least five years, the basis on the original gain is increased by 10% of the original gain. If the OZ asset or investment is held by the taxpayer for at least seven years, the basis on the original gain is increased by an additional 5% of the original gain. The deferred gain is recognized on the earlier of the date on which the qualified OZ investment is disposed of or December 31, 2026. Only taxpayers who rollover capital gains of non-OZ assets before December 31, 2026, will be able to take advantage of the special treatment of capital gains for non-OZ and OZ realizations under the provision. The basis of an investment in a QOF immediately after its acquisition is zero. If the investment is held by the taxpayer for at least five years, the basis on the investment is increased by 10% of the deferred gain. If the investment is held by the taxpayer for at least seven years, the basis on the investment is increased by an additional 5% of the deferred gain. If the investment is held by the taxpayer until at least December 31, 2026, the basis in the investment increases by the remaining 85% of the deferred gain.

Second, P.L. 115-97 excludes from gross income the post-acquisition capital gains on investments in QOFs that are held for at least 10 years. Specifically, in the case of the sale or exchange of an investment in a QOF held for more than 10 years, at the election of the taxpayer the basis of such investment in the hands of the taxpayer shall be the fair market value of the investment at the date of such sale or exchange. Taxpayers can continue to recognize losses associated with investments in QOFs as under current tax law.

OZ tax incentives are in effect from the enactment of P.L. 115-97 on December 22, 2017, through December 31, 2026. There is no gain deferral available with respect to any sale or exchange made after December 31, 2026, and there is no exclusion available for investments in qualified OZs made after December 31, 2026.

Bond Guarantee Program

The Small Business Jobs Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-240) authorized the Bond Guarantee program on September 27, 2010.71 The Fund's Bond Guarantee program is designed to provide a low-cost source of long-term, "patient" capital to CDFIs.72 Treasury may guarantee up to 10 bonds per year, each at a minimum of $100 million. The total of all bonds cannot exceed $1 billion per year. Each bond is fully guaranteed by the United States and offered at a cost equivalent to the current Treasury rates for comparable maturities. The bonds cannot exceed a maturity of 30 years, are taxable, and do not qualify for Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) credit.73 Treasury guarantees the full amount of notes or bonds issued to support CDFIs that make investments for eligible community or economic development purposes.74

Authorized uses of the loans financed may include a variety of financial activities that constitute community or economic development in low-income or underserved areas (e.g., the provision of basic financial services, housing that is principally affordable to low-income individuals, and businesses that provide jobs for low-income people or are owned by low-income individuals).75

By legislative design, the Bond Guarantee program is a zero-subsidy credit program and does not require annual appropriations funding. Because the bonds will be guaranteed by the United States, in accordance with federal credit policy, the Federal Financing Bank (FFB), a U.S. government corporation under the general supervision and direction of Treasury, will purchase the bonds issued by qualified issuers.76 Qualified issuers will lend the bond proceeds to eligible CDFIs. The FFB finances obligations that are fully guaranteed by the United States, such as the bonds or notes issued by CDFIs under the CDFI Bond Guarantee program.

Despite being first authorized in 2010, initial implementation of the Bond Guarantee program was slow. Congress reduced the program's potential lending authority of $4 billion ($1 billion annually for four years of authorization) to $1 billion between 2010 and 2014 due to delays in appropriating budget authority for new direct loan obligations under the program. The Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2015 (P.L. 113-235) reauthorized the program and limited the total loan amount supported by the bonds in FY2015 to $750 million. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016 (P.L. 114-113) extended authority to guarantee bonds in FY2016 to support $750 million in CDFI lending. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017 (P.L. 115-31) limited the CDFI lending supported by the bonds issued in FY2017 to $500 million.

Capital Magnet Fund

The Housing and Economic Recovery Act (HERA) of 2008 (P.L. 110-289) established the Capital Magnet Fund (CMF) for CDFIs and other nonprofits to expand financing for the development, rehabilitation, and purchase of affordable housing and economic development projects in distressed communities.77 Through the CMF, the Fund provided competitively awarded grants to CDFIs and qualified nonprofit housing organizations. CMF awards could be used to finance affordable housing activities as well as related economic development activities and community service facilities. Awardees were able to use financing tools, such as loan loss reserves, loan funds, risk-sharing loans, and loan guarantees, to produce eligible activities whose aggregate costs are at least 10 times the size of the award amount.78

Three types of organizations were eligible to apply for a CMF award. An organization applying for a CMF award had to either (1) be certified as a CDFI by the Fund; (2) have an application for CDFI certification pending with the Fund, provided such application was submitted prior to the due date specified in the applicable notice of funds availability; or (3) be a nonprofit organization having as one of its principal purposes the development or management of affordable housing.

As authorized in HERA, the CMF was to receive funding via a set-aside from government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. However, such contributions have been suspended indefinitely. The GSEs never made contributions to the CMF, as was originally expected under HERA, due to their financial condition and status under conservatorships.79 Instead, the Consolidation Appropriations Act, 2010 (P.L. 111-117) appropriated $80 million in initial funding for the CMF for FY2010.80 The Fund awarded grants to 23 CDFIs and qualified nonprofit housing organizations serving in FY2010.81 It received a total of 230 applications requesting $1 billion for the FY2010 CMF funding round.82

Funding for the CMF was discontinued for FY2011, and contributions from the GSEs remained suspended. In 2014, a group of 33 Senators and a group of 78 Representatives sent letters to Mel Watt, director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), asking that the FHFA cease its suspension of contributions to the CMF (issued when Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac entered into conservatorship).83 On December 11, 2014, Director Watt sent letters to the GSEs instructing them to begin making their first-ever financial contributions to the CMF.84

In FY2016, the second round of CMF awards, 32 organizations received $91.47 million in awards spread across 37 states and the District of Columbia.85

Policy Considerations

This section analyzes four policy considerations that may generate congressional attention regarding the Fund's use of federal resources to promote economic development. First, it analyzes the debate on targeting development assistance toward people versus places. Second, it examines the debate on targeting economic development policies toward labor or capital. Third, it analyzes whether the Fund plays a unique role in promoting economic development or whether it duplicates, complements, or competes with the goals and activities of other federal, state, and local programs. Fourth, it examines assessments of the Fund's management.

How Effective Are Geographically Targeted Economic Development Policies?

From an economic perspective, what theoretical basis is there for the promotion of development in distressed communities? Economic theory suggests firms and workers will locate to the most efficient and productive areas to do business in the long run, without the assistance of government policy. From this perspective, government policies, such as tax exemptions or tax expenditures, that create incentives to locate in one area at the expense of another result in net social loss of efficiency—where finite resources are not being used to produce their maximum output for the lowest cost.86 Economic theory indicates that these policies create a distortion in the market, such that resources are directed from an area of higher potential productivity to an area of lower potential productivity.87

However, government policy may be economically justified if business investment in distressed communities would generate positive externalities.88 Positive externalities, also known as spillover benefits, occur when the actions of one individual or firm benefit others in society. Because a given business will tend to only consider its own (private) benefit from an activity, and not the total benefit to society, too little of the positive externality-generating activity may be undertaken from society's perspective. Governments, however, may intervene through the use of taxes, subsidies, and other forms of assistance to align the interests of individual businesses with the interests of society to achieve a more economically efficient outcome.

How may government policy generate positive externalities within a community? It is possible that potential investors may invest in an underdeveloped community as long as the potential return on that investment exceeds the potential risk. If investors are not attracted to a particular community, however, government incentives may be able to change investors' perceived return and risk calculations. If this initial group of businesses is successful, due in part to the government's incentives, then that success may send positive signals about potential return for other businesses that choose to locate in the community. In addition, if government incentives encourage employment in the communities, employees may feel they have more of a stake in the community and participate positively in activities outside of work. Although government incentives initially benefit particular businesses or investments, they may also allow the broader community to capture these spillover benefits.

Empirical evaluations of geographically targeted economic development policies have been mixed.89 Evaluations differ, in part, due to several factors, including the use of different evaluation criteria for economic development, different policies or sample areas used for analysis, or the use of different empirical strategies. Many of these studies are based on variations of state and local enterprise zones and federal empowerment zones. Enterprise zones typically provide certain tax incentives and regulatory relief for distressed communities, whereas federal empowerment zones provide certain tax exemptions and employer tax credits for hiring new employees.

Some studies have found that geographically targeted policies have a positive effect on several indicators of economic activity in the targeted area. These studies cite that such policies facilitate entrepreneurship and increase employment in the targeted area.90 John Ham et al. find that an empowerment zone designation reduces local unemployment and poverty rates by 8.7% and 8.8%, respectively, whereas an enterprise zone designation reduces local unemployment and poverty rates by 2.6% and 20%, respectively.91 Leslie Papke's review of surveys from participants in multiple U.S. enterprise zones indicates that start-up firms average approximately 25% of new businesses within the targeted zones.92 Barry Rubin and Margaret Wilder's analysis of Indiana's enterprise zone indicates that 76% of the 1,878 jobs created between the beginning of the program in 1983 and 1986 could not be attributed to regional or sectoral growth.93 Assuming these residual jobs were created in large part due to policy, the researchers calculated that the creation of each of these 1,430 jobs cost taxpayers $1,372 per job, annually.94

By contrast, other evaluations indicate that these policies have little effect on economic activity within the targeted area or that they do not contribute to a net increase of economic activity throughout the larger economy. These studies find that geographically targeted policies encourage some types of economic activity at the detriment of others—thus rearranging the mix of economic activity within the target area.95 For example, Andrew Hanson and Shawn Rohlin indicate that location-based tax incentives have a positive effect on the firm location in industries that benefit the most from the tax incentives, but net growth in new establishments is offset by declines or slower growth in other industries that are less likely to use the tax incentives.96

In addition, some studies indicate that geographically targeted policies may shift activity from a comparative area toward the targeted zone, rather than create new economic activity. For example, Tami Gurley-Calvez et al. find that the NMTC may have led to an increase in corporate investment within the targeted areas but that it did not lead to a net increase in corporate investment.97 These authors conclude that the NMTC might encourage investment to shift from one LIC to another close substitute, as some corporate investors might already be investing in LICs to fulfill Community Reinvestment Act requirements.98

The effect of geographically targeted economic development policies on local property prices is also an area of contention among researchers.99 From a theoretical perspective, government incentives to increase the supply of affordable property increase the demand for that property. That greater demand drives rents higher. If local residents do not benefit from the increase in economic activity, then higher property values may encourage those with lower incomes to move out of the community.100

Given the lack of consensus among researchers on the effectiveness of geographically targeted economic policies, policy makers may opt to more narrowly define the primary objective of development. At its core, the debate is a question of whether development policies should help people or places. If the primary objective is to improve business and employment opportunities relative to other areas, then these policies might be effective. If the primary objective of such policies is to create new jobs, then the effect of these policies may be limited. If policy makers wish to help the poor, then it might be asked why government assistance should only be extended to the poor living in distressed communities (as opposed to the poor living in nondistressed communities). Each standard for evaluation implies a different set of metrics and results in a different set of trade-offs.

Should Economic Development Policies Target Capital or Labor?

Assuming geographically targeted policies can positively affect economic development within the intended community, what type of benefit is most effective? Policies can provide a benefit related to labor costs, capital costs, or both (i.e., total costs). In other words, should development policies target workers, business owners, or both?

When a geographically targeted subsidy is applied to one of these two factors of production, economic theory suggests two behavioral responses occur. The first response is that total output (i.e., economic activity) increases. This increase in total output increases the use of both capital and labor, to some degree. Economists label this the output effect of production. The second response is a substitution effect, whereby firms use one factor of production at the detriment of the other. The net effect of the output effect and substitution effect determines the total effect of the policy. In other words, the total effect reflects whether the policy benefits labor more than capital or vice versa.

For example, a labor subsidy, such as a payroll tax credit for hiring a worker, provided within a particular area will encourage labor-intensive firms to locate within that same area. All firms (whether attracted by the labor subsidy or already operating in the area) will tend, in addition to expanding operations, to substitute their use of labor for capital. If the objective of the labor subsidy is to promote employment, then the substitution effect (the use of more labor, relative to capital) reinforces the benefits of the output effect (the use of more labor, due to expanded operation). In other words, the policy is expected to result in a net increase in employment.

By contrast, a capital subsidy, such as tax deductions for capital investments, provided within a particular area will encourage capital-intensive firms to locate within that area. All firms (whether attracted by the capital subsidy or already operating in the area) will tend, in addition to expanding operations, to substitute their use of capital for labor. If the objective of the capital subsidy is to promote employment, then the substitution effect (the use of more capital, relative to labor) offsets the benefits of the output effect (the use of more labor, due to expanded operation). Moreover, if the substitution effect is more powerful than the output effect, a capital subsidy may end up decreasing employment in the area.101 In this instance, the net effect of the capital subsidy is less employment in the area than before the policy.

Policies that relate to total costs may balance the trade-off between the promotion of capital or labor in the targeted area. If producers are indifferent between using labor or capital, then a policy that provides equally weighted incentives toward the employment of labor and capital will result in a positive income effect, with no substitution effect. However, if producers use relative factor price differentials to inform the mix of capital and labor they employ, then the result of a policy that relates to total costs will depend on the strength and direction of the substitution effect.

Studies indicate that geographically targeted tax incentives for business owners (e.g., the NMTC) have a positive but limited effect in increasing the economic well-being of other individuals living within the target area. Timothy Bartik's review of 57 empirical studies on the effect of state and local preferential tax incentives for employers in a state or metropolitan area found that 57% of the studies found at least one statistically significant effect on generating development in the target area.102 Bartik found that the average measure of responsiveness, or elasticities, or change between tax measures and economic activity in a targeted state or metropolitan area ranges from -0.25 across all studies to -0.51 for studies that include statistical controls for both public service and fixed effects. In other words, the study concluded that a 10% reduction in all taxes within a particular geographic zone would generate a 2.5% to 5.1% increase in economic activity within the same zone.

Do the Fund's Programs Duplicate Other Government Efforts?

Legislative interest in identifying duplicative federal programs has grown as some Members of Congress have become concerned about the size or efficient management of federal budgetary resources. GAO defines duplicative programs as federal programs that overlap with the goals or activities of other federal, state, or local policies.103

Some say the Fund's programs duplicate other federal, state, local, and private-sector efforts to increase economic development in distressed and low-income communities. The Fund's website contains a guide that provides a list of possible financing sources for CDFIs.104 At the federal level, various programs exist as possible sources of finance for CDFIs. These programs are managed by executive agencies, such as USDA, SBA, HHS, HUD, Interior, Treasury, and Commerce. Based on this variety of possible funding sources for CDFIs, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), under President George W. Bush, said the Fund's core CDFI program was not unique because several states administer similar programs and CDFIs can use private-sector equity investment to accomplish activities they would otherwise accomplish with the Fund's awards.105

In addition, the NMTC is not the only tax incentive designed to encourage economic development in distressed communities. The Senate Committee on the Budget Print on Tax Expenditures lists several other tax incentives that are meant to achieve similar goals as the NMTC. These incentives provide short-term development assistance (e.g., disaster relief provisions), enhance tribal area development, and encourage business and capital investment in target communities.106 The Bush era's OMB also stated that the NMTC was not unique because other federal, state, and local tax credit programs are available through agencies such as HUD and Commerce's Economic Development Agency.107

However, others believe the Fund plays a unique or complementary role to the programs mentioned above. First, Fund supporters most commonly argue that community lenders are ready and willing to fill financing gaps, but they often struggle to find the amount of capital and liquidity they need to meet loan demand in distressed communities.108 Although certain CDFIs may be eligible for similar forms of assistance from other federal programs (e.g., guaranteed loans from SBA), the Fund's limitations to activities in distressed communities allows CDFIs to compete with other entities that face similar economic, environmental, and geographic challenges. Second, Fund programs have supported alternatives to predatory lending institutions in distressed communities—notably in tribal communities.109 Third, some argue that the Fund's programs complement, not compete with, the goals and programs of other federal initiatives. For example, former Assistant Secretary for Financial Institutions Michael Barr testified before the House Committee on Financial Services that funding for the Community Reinvestment Act encourages more entities to invest in CDFIs.110

In contrast to the assessment by the Bush era's OMB, some say the Fund provides incentives for activity that private-sector investors would not otherwise engage in. For example, the Fund enables more CDFIs to provide affordable, critical-gap financing for businesses.111 In other words, the Fund encourages CDFIs to provide short-term loans to businesses or homebuyers to cover immediate financial obligations while that borrower secures sufficient funds to make a full payment or find a more stable financing scheme. In addition, CDFIs provide technical assistance and training to borrowers to reduce default risk. For these reasons, some representatives from national banking chains argue that CDFIs complement traditional banking products in distressed communities and LICs and help these financial markets operate more efficiently.112

Is the CDFI Fund Managed Effectively?

Concerns over the Fund's management primarily involve questions over the transparency and consistency of the Fund's award evaluation processes.

Early on in the Fund's history, there were concerns in Congress about whether the applications for awards were being issued based on an objective and transparent criteria.113 Additionally, there were concerns over the Fund's ability to monitor and evaluate the performance of award recipients.114 These initial concerns have been largely addressed as the Fund has incorporated feedback and recommendations from outside parties, such as the Treasury's Office of Inspector General. The Fund also has developed the Community Investment Impact System (CIIS), which is a database that CDFIs and CDEs use to submit their Institution Level Reports (ILRs) and Transaction Level Reports (TLRs) to the Fund. The Fund issues annual reports and releases this data to the public.115

Some Members of Congress have expressed concern regarding the lack of CDFIs that serve U.S. territories and rural communities.116 However, a 2012 GAO report concluded that the policies and procedures of the CDFI and NMTC programs help ensure that awards and allocations generally are proportionate to the numbers of qualified applicants that serve metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas.117 In addition, some Members of Congress have expressed interest in the performance of CDFIs compared with their non-CDFI peers.118

In addition, some Members of Congress raised concerns over the use of funds from the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) for assistance to CDFIs. President Obama authorized a program that made certified CDFIs eligible to receive capital investments at a discounted dividend, with the intent of increasing the supply of credit to community banks.119 Some maintained that TARP's temporary funds were not intended to target regional banks and that the program functionally resulted in a bypass of the typical appropriations process for the Fund.120

Bank on USA Program

In his FY2011 budget request, President Obama proposed the Bank on USA program as a means to facilitate access to, and evaluate the effectiveness of, affordable, high-quality financial products, services, and education to unbanked and underbanked individuals.121 Title 12 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (P.L. 111-203) authorized the Fund to "encourage initiatives for financial products and services that are appropriate and accessible for millions of Americans who are not fully incorporated into the financial mainstream."122

Although the President requested more than $41 million in funding for Bank on USA for FY2012 and $20 million for FY2013, Congress did not approve funding for the program.123 There was no request for Bank on USA appropriations in the President's FY2014 budget request.

Financial Education and Counseling Pilot Program

The Financial Education and Counseling (FEC) pilot program provided grants in FY2010 to organizations that provided financial education and counseling services to prospective homebuyers. The goals of the FEC pilot program were to increase the financial knowledge and decision-making capabilities of prospective homebuyers, assist prospective buyers to plan for major purchases, and provide information on how to improve credit scores. Certified CDFIs, a Housing and Urban Development-approved housing counseling agency, credit union, or government entity could request FEC funding for administrative expenses for FEC-related programs.124

Section 1132 of HERA of 2008 (P.L. 110-289) authorized the Secretary of the Treasury to create FEC pilot programs. For FY2009, Congress appropriated $2 million to the Fund for the FEC program.125 Treasury selected five organizations to receive $400,000 for their services toward the mission of the program.126 In FY2010, Congress appropriated $4.15 million, of which $3.15 million was designated for an eligible organization in Hawaii.127

A 2011 GAO report concluded that Treasury's process for selecting FEC grantees was applied consistently using established criteria. In 2010, the four grantees served a combined total of 311 clients.128 However, GAO could not meaningfully assess the impact of the program or the effectiveness of individual grantees because grantees had been providing services under the FEC program for less than a year.129

Appendix B. Certified Native CDFIs

|

State |

Certified Native CDFIs |

|

Oklahoma |

8 |

|

South Dakota |

7 |

|

Hawaii |

7 |

|

Minnesota |

6 |

|

New Mexico |

5 |

|

Arizona |

5 |

|

California |

4 |

|

Wisconsin |

4 |

|

Washington |

4 |

|

Michigan |

3 |

|

Colorado |

3 |

|

Montana |

3 |

|

Alaska |

3 |

|

North Dakota |

2 |

|

Nebraska |

2 |

|

Maine |

1 |

|

Mississippi |

1 |

|

North Carolina |

1 |

|

Oregon |

1 |

|

Wyoming |

1 |

|

New York |

1 |

|

Texas |

1 |

|

Total |

73 |

Source: Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Fund, at https://www.cdfifund.gov/programs-training/certification/cdfi/Pages/default.aspx.

Note: CDFI counts are as of November 30, 2017.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Janet L. Yellen, Chair of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, "Welcoming Remarks," Speech at Community Banking in the 21st Century Fifth Annual Community Banking Research and Policy Conference cosponsored by the Federal Reserve System and Conference of State Bank Supervisors, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, October 4, 2017, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/yellen20171004a.htm. |

| 2. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Banking, Finance, and Urban Affairs, Proposed Legislation: The Community Development Banking and Financial Institutions Act of 1993, Message from the President, 103rd Cong., 1st sess., July 15, 1993, H. Doc. 103-118 (Washington: GPO, 1993). |

| 3. |

Ibid. |

| 4. |

The Emergency Supplemental Appropriations for Additional Disaster Assistance, for Anti-terrorism Initiatives, for Assistance in the Recovery from the Tragedy that Occurred at Oklahoma City, and Rescissions Act, 1995 (P.L. 104-19). |

| 5. |

See Lehn Benjamin, Julia Sass Rubin, and Sean Zielenbach, "Community Development Financial Institutions: Current Issues and Future Prospects," Proceedings, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System's Community Affairs Research Conference, Sustainable Community Development: What Works, What Doesn't, and Why, March 28, 2003, p. 7, at http://www.federalreserve.gov/communityaffairs/national/CA_Conf_SusCommDev/pdf/zeilenbachsean.pdf. |

| 6. |

U.S. Department of the Treasury, "Organizational Structure," at http://www.treasury.gov/about/organizational-structure/Pages/default.aspx. |

| 7. |

See U.S. Department of the Treasury, "U.S. Treasury Department Announces New Director of the Community Development Financial Institutions Fund," press release, November 25, 2014, at http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/jl9709.aspx. |

| 8. |

During the Clinton Administration, funding was provided through the annual Veteran's Affairs-HUD-Independent agencies appropriations. |

| 9. |

U.S Department of the Treasury, Community Development Financial Institutions Fund FY2018 Congressional Justification for Appropriations and Annual Performance Plan, p. 2, at https://www.treasury.gov/about/budget-performance/CJ18/13.%20CDFI%20Fund%20-%20FY%202018%20CJ.pdf. |

| 10. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), Community Development Financial Institutions and New Markets Tax Credit Programs in Metropolitan and Nonmetropolitan Areas, GAO-12-547R, April 26, 2012, p. 4, at http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-12-547R. |

| 11. |

For a list of these certified CDFIs with their contact information, see CDFI Fund, "CDFI Certification," at https://www.cdfifund.gov/programs-training/certification/cdfi/Pages/default.aspx. |

| 12. |

CRS analysis of certified CDFI data at https://www.cdfifund.gov/programs-training/certification/cdfi/Pages/default.aspx. |

| 13. |

Ibid. |

| 14. |

The Fund has not updated its public counts of certified community development entities (CDEs) since this date and has removed the spreadsheet of certified CDEs from its website. |

| 15. |

This description was adapted from the Joint Explanatory Statement of the Committee of Conference for H.R. 1 (115th Congress), December 18, 2017, at http://docs.house.gov/billsthisweek/20171218/Joint%20Explanatory%20Statement.pdf. |

| 16. |

12 C.F.R. §1805.401. |

| 17. |

For a historical analysis of these debates, see the discussion section of CRS Report R41268, Small Business Administration HUBZone Program, by [author name scrubbed]. |

| 18. |

These programs include the 1993 reform of the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 (P.L. 95-128) and the Empowerment Zone program, established by the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 (P.L. 103-66). |

| 19. |

Laws pertaining to the CDFI Fund's financial assistance (FA) and technical assistance (TA) are located in 46 U.S.C. §§1805.300-1805.303. |

| 20. |

12 C.F.R. §1805.701. |

| 21. |

12 C.F.R. §1806.200(b)(1). |

| 22. |

12 C.F.R. §1806.200(b)(2). |

| 23. |

CDFI Fund, "Community Development Financial Institutions Fund Mapping System (CIMS)," at https://www.cdfifund.gov/Pages/mapping-system.aspx. |

| 24. |

12 C.F.R. §1806.200(c). |

| 25. |

Department of the Treasury, "Notice of Funds Availability (NOFA) Inviting Applications for Financial Assistance (FA) Awards or Technical Assistance (TA) Grants Under the Community Development Financial Institutions Program (CDFI Program) Fiscal Year (FY) 2017 Funding Round," 82 FR 11991 Federal Register 11991 - 12008, February 27, 2017. |

| 26. |

12 C.F.R. §1805.301. |

| 27. |

Department of the Treasury, "Notice of Funds Availability (NOFA) Inviting Applications for Financial Assistance (FA) Awards or Technical Assistance (TA) Grants Under the Community Development Financial Institutions Program (CDFI Program) Fiscal Year (FY) 2017 Funding Round," 82 FR 11991 Federal Register 11991 - 12008, February 27, 2017. |

| 28. |

12 C.F.R. §1805.303. |

| 29. |

12 C.F.R. §1805.501. |

| 30. |