Small Business Credit Markets and Selected Policy Issues

Small businesses are owned by and employ a wide variety of entrepreneurs—skilled trade technicians, medical professionals, financial consultants, technology innovators, and restaurateurs, among many others. As do large corporations, small businesses rely on credit to purchase inventory, to cover cash flow shortages that may arise from unexpected expenses or periods of inadequate income, or to expand operations. During the Great Recession of 2007-2009, lending to small businesses declined. A decade after the recession, it appears that while many small businesses enjoy increased access to credit, others might still face credit constraints.

Congress has demonstrated an ongoing interest in credit availability for small businesses, viewing them as a medium for stimulating the economy and creating jobs. In general, Congress’s interest in the small business credit market focuses on quantity and price—specifically (1) whether small businesses can reasonably obtain loans from private lenders and (2) whether the prices (lending rates and fees) of such credit are fair and competitive. Congress passed legislation to facilitate lending to small businesses that are likely to face hurdles in obtaining credit:

The Small Business Act of 1953 (P.L. 83-163) established the Small Business Administration (SBA), which administers several types of programs to support capital access for small businesses that struggle to obtain credit on reasonable terms and conditions from private-sector lenders.

The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA; P.L. 95-128) encouraged banks to address persistent unmet small business credit demands in low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities.

The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act; P.L. 111-203) required the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (CFPB) to collect data from small business lenders concerning credit applications made by women-owned, minority-owned, and small businesses with the goal of better understanding their financing needs. The CFPB has not yet implemented this requirement.

Data that capture small business borrowers’ characteristics and lenders’ underwriting processes (i.e., their processes for determining whether borrowers are creditworthy) could help to accurately determine whether small businesses have sufficient and fairly priced access to private credit. Various government agencies and financial institutions define small business using factors that may be based upon annual revenues, number of employees, market scope, market share, and some or all of the above factors. Because no consensus definition of a small business exists, data to analyze the small business credit market’s performance are limited and fragmented. Moreover, certain small businesses face additional challenges that may force them to seek financing outside of traditional business credit markets. Many new start-up firms, for example, do not have the financial track records to qualify for standard business loans and frequently must rely on mortgage and consumer credit. In addition, many small businesses rely on customized lending products, thus limiting their choice of lenders to those with specialized underwriting methodologies or business models. The lack of a consensus definition of small business, along with the wide variety of idiosyncratic business risks, hinders the availability of conclusive evidence on the small business credit market’s overall performance and, therefore, the ability to assess the effectiveness of various policy actions designed to increase small business lending.

In 2017, the CFPB issued a request for information on the small business lending market to solicit feedback on how to implement the Dodd-Frank requirement to collect data from financial institutions on small business credit applications. Final rulemaking, however, has been delayed. In addition, various bills regarding the small business credit market have been introduced in the 116th Congress. For example, H.Res. 370 would express “the sense of the House of Representatives that small business owners seeking financing have fundamental rights, including transparent pricing and terms, competitive products, responsible underwriting, fair treatment from financing providers, brokers, and lead generators, inclusive credit access, and fair collection practices.” H.R. 3374 would amend the Equal Credit Opportunity Act to require the collection of small business loan data related to LGBTQ-owned businesses. H.R. 1937 and S. 212, the Indian Community Economic Enhancement Act of 2019, among other things, would require the Government Accountability Office to conduct a study to assess and quantify the extent to which federal loan guarantees, such as those provided by the SBA, have been used to facilitate credit access in these communities.

Small Business Credit Markets and Selected Policy Issues

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- The Demand for SBLs: Multiple Definitions of a Small Business

- The Supply of SBLs: Background on Lenders and Industry Underwriting and Funding Practices

- Types of Small Business Lenders

- Bank Lending to Small Businesses

- Credit Union Lending to Small Business Members

- Marketplace (Fintech) Lending

- Access to Funding in Different Growth Stages

- Funding for Start-ups

- Funding for Later-Stage Small Firms

- Attempting to Identify SBL Market Failures

- Shortage of Small Loans

- Collateral Eligibility for Secured Lending

- SBLs and the Community Reinvestment Act

- Small Business Loan Pricing

- CFPB Collection of Small Business Data

- Conclusion

Summary

Small businesses are owned by and employ a wide variety of entrepreneurs—skilled trade technicians, medical professionals, financial consultants, technology innovators, and restaurateurs, among many others. As do large corporations, small businesses rely on credit to purchase inventory, to cover cash flow shortages that may arise from unexpected expenses or periods of inadequate income, or to expand operations. During the Great Recession of 2007-2009, lending to small businesses declined. A decade after the recession, it appears that while many small businesses enjoy increased access to credit, others might still face credit constraints.

Congress has demonstrated an ongoing interest in credit availability for small businesses, viewing them as a medium for stimulating the economy and creating jobs. In general, Congress's interest in the small business credit market focuses on quantity and price—specifically (1) whether small businesses can reasonably obtain loans from private lenders and (2) whether the prices (lending rates and fees) of such credit are fair and competitive. Congress passed legislation to facilitate lending to small businesses that are likely to face hurdles in obtaining credit:

- The Small Business Act of 1953 (P.L. 83-163) established the Small Business Administration (SBA), which administers several types of programs to support capital access for small businesses that struggle to obtain credit on reasonable terms and conditions from private-sector lenders.

- The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA; P.L. 95-128) encouraged banks to address persistent unmet small business credit demands in low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities.

- The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act; P.L. 111-203) required the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (CFPB) to collect data from small business lenders concerning credit applications made by women-owned, minority-owned, and small businesses with the goal of better understanding their financing needs. The CFPB has not yet implemented this requirement.

Data that capture small business borrowers' characteristics and lenders' underwriting processes (i.e., their processes for determining whether borrowers are creditworthy) could help to accurately determine whether small businesses have sufficient and fairly priced access to private credit. Various government agencies and financial institutions define small business using factors that may be based upon annual revenues, number of employees, market scope, market share, and some or all of the above factors. Because no consensus definition of a small business exists, data to analyze the small business credit market's performance are limited and fragmented. Moreover, certain small businesses face additional challenges that may force them to seek financing outside of traditional business credit markets. Many new start-up firms, for example, do not have the financial track records to qualify for standard business loans and frequently must rely on mortgage and consumer credit. In addition, many small businesses rely on customized lending products, thus limiting their choice of lenders to those with specialized underwriting methodologies or business models. The lack of a consensus definition of small business, along with the wide variety of idiosyncratic business risks, hinders the availability of conclusive evidence on the small business credit market's overall performance and, therefore, the ability to assess the effectiveness of various policy actions designed to increase small business lending.

In 2017, the CFPB issued a request for information on the small business lending market to solicit feedback on how to implement the Dodd-Frank requirement to collect data from financial institutions on small business credit applications. Final rulemaking, however, has been delayed. In addition, various bills regarding the small business credit market have been introduced in the 116th Congress. For example, H.Res. 370 would express "the sense of the House of Representatives that small business owners seeking financing have fundamental rights, including transparent pricing and terms, competitive products, responsible underwriting, fair treatment from financing providers, brokers, and lead generators, inclusive credit access, and fair collection practices." H.R. 3374 would amend the Equal Credit Opportunity Act to require the collection of small business loan data related to LGBTQ-owned businesses. H.R. 1937 and S. 212, the Indian Community Economic Enhancement Act of 2019, among other things, would require the Government Accountability Office to conduct a study to assess and quantify the extent to which federal loan guarantees, such as those provided by the SBA, have been used to facilitate credit access in these communities.

Introduction

Small businesses are owned by and employ a wide variety of entrepreneurs—skilled trade technicians, medical professionals, financial consultants, technology innovators, and restaurateurs, among many others. As do large corporations, small businesses rely on loans to purchase inventory, to cover cash flow shortages that may arise from unexpected expenses or periods of inadequate income, or to expand operations. The Federal Reserve has reported that lending to small businesses declined during the Great Recession of 2007-2009.1 During the recession, many firms scaled down operations in anticipation of fewer sales, and lenders also tightened lending standards. A decade after the recession, evidence on whether lending to small business has increased is arguably inconclusive. Some small firms may be able to access the credit they need; however, others may still face credit constraints, and still others may be discouraged from applying for credit. Furthermore, drawing direct conclusions about small business access to credit can be difficult because available data are limited and fragmented.

Congress has demonstrated an ongoing interest in small business loans (SBLs), viewing small businesses as a medium for stimulating the economy and creating jobs. Congress's interest in small business credit access generally focuses on (1) whether small businesses can secure credit from private lenders and (2) whether small businesses can obtain such credit at fair and competitive lending rates. In other words, policymakers are interested in whether market failures exist that impede small business access to credit and, if so, what policy interventions might be warranted to address those failures.2 Market failures, in economics and specifically in the SBL market context, refer to barriers that impede credit allocation by private lenders. For example, some lenders may be reluctant to lend to businesses with collateral assets (e.g., inventories) that are difficult to liquidate, as may be typical of some small businesses (e.g., restaurants). Under certain financial or regulatory circumstances, small loans may not generate sufficient returns to justify their origination costs, which also may be considered a market failure.3 In addition, market failures may exist when borrowers pay noncompetitive lending rates in excess of their default risk. Start-ups and some small businesses that provide niche products frequently must rely on mortgage or consumer credit or private equity investors rather than more traditional SBLs because lenders find it challenging to price loans for these firms, which could be another indicator of SBL market failure.

Obtaining conclusive evidence on SBL market performance in terms of quantities and pricing is difficult for several reasons. First, there is no consensus definition of a small business across government and industry. Moreover, as the Federal Reserve stated, "fully comprehensive data that directly measure the financing activities of small businesses do not exist."4 Drawing conclusions about the availability and costs of SBLs is not possible using existing data sources, which lack information such as the size and financial characteristics of the businesses that apply for credit, the types of loan products they seek, the types of lenders to whom they applied for credit, and which credit requests were rejected and which were approved. Second, the risks small business owners take are not standardized and vary extensively across industries and locations. For this reason, determining whether SBL prices (lending rates and fees) are competitive is difficult without standardized benchmark prices that can be used to compare the relative prices of other SBLs.

To address SBL market failures, Congress passed legislation to facilitate lending to small businesses that are likely to face hurdles obtaining credit. For example, the Small Business Act of 1953 (P.L. 83-163) established the Small Business Administration (SBA), which administers several types of programs to support capital access for small businesses that can demonstrate the inability to obtain credit at reasonable terms and conditions from private-sector lenders.5 The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA; P.L. 95-128) encouraged banks to address persistent unmet small business credit demands in low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities.6 The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act; P.L. 111-203) required the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (CFPB) to collect data from small business lenders to identify the financing needs of small businesses, especially those owned by women and minorities.7 (The CFPB has not yet implemented this requirement.)

In addition, various bills addressing the SBL market have been introduced in the 116th Congress. For example, H.Res. 370 would express "the sense of the House of Representatives that small business owners seeking financing have fundamental rights, including transparent pricing and terms, competitive products, responsible underwriting, fair treatment from financing providers, brokers, and lead generators, inclusive credit access, and fair collection practices." H.R. 3374 would amend the Equal Credit Opportunity Act8 to require the collection of small business loan data related to LGBTQ-owned businesses. H.R. 1937 and S. 212, the Indian Community Economic Enhancement Act of 2019, among other things, would require the Government Accountability Office to assess and quantify the extent to which federal loan guarantees, such as those provided by the SBA, have been used to facilitate credit access in these communities.

This report examines the difficulty of assessing and quantifying market failures in the SBL market, which consists of small business borrowers (demanders) and lenders (suppliers). It begins by reviewing various ways to define a small business, illustrating that there is no consensus definition of the demand side of the SBL market across government or industry. The focus then shifts to describing the supply side—namely the types of lenders that lend to small businesses, as well as their lending business models and practices. The report subsequently attempts to identify credit shortages in certain SBL market segments (e.g., the market for small loans, loans for businesses with risky or unsuitable collateral, and loans for businesses in underserved communities). It also examines whether market failures associated with SBL pricing can be identified. Finally, the report concludes by briefly discussing the Dodd-Frank Act requirement that the CFPB collect data to facilitate the understanding of SBL market activity.

The Demand for SBLs: Multiple Definitions of a Small Business

There is no universally accepted definition of a small business. The federal government and industry define small businesses differently in different circumstances. Although factors such as annual earnings, number of employees, type of business, and market share are typically considered, determining the universe of small businesses from which to collect data is difficult without a consensus definition. If a consensus definition existed, then identifying a small business for data-collection purposes would become more feasible—for example, a concise question on a loan application might identify whether the business applying for the loan met certain defined factors making it a small business. Below are examples of the ways regulators, researchers, Congress, and industry have defined small businesses:

- The SBA defines a small business primarily by using a size standards table it compiles and updates periodically. The table lists size thresholds for various industries by either average annual receipts or number of employees.9 The SBA also defines small businesses differently for different SBA programs. For example, the SBA's 7(a), Certified Development Company/504, and Small Business Investment Company (SBIC) programs have alternative size standards based on tangible net worth and average net income.10

- Academic research frequently uses a firm that has 500 employees or fewer (but does not monopolize an industry) as a proxy measure for a small business. This definition has been adopted by various federal agencies, such as the U.S. Census Bureau, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the Federal Reserve.11 In addition, some research views microbusinesses as a subset of small businesses. A common academic definition of a microbusiness is a firm with only one owner, five employees or fewer, and annual sales and assets under $250,000.12

- Small business definitions in statute also vary. For example, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) sets different size standards for small businesses under various tax laws. The IRS provides certain tax forms for self-employed taxpayers and small businesses with assets under $10 million.13 The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA; P.L. 111-148), however, defined a small business in multiple ways (e.g., fewer than 50 full-time employees to avoid ACA's employer shared responsibility provision; fewer than 25 full-time equivalent employees for tax credits, etc.).14

- According to a Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) survey, small and large banks have their own definitions of a small business.15 Small banks (defined as banks with $10 billion or less in assets) view a small business as one in which the owner "wears many hats," referring to an owner who performs multiple tasks, perhaps because the firm is a start-up or still in its early growth stage. Large banks define small businesses more formally, in terms of annual revenues and sales.

The Supply of SBLs: Background on Lenders and Industry Underwriting and Funding Practices

This section provides background on small business lenders and underwriting practices. Although small businesses rely on a variety of credit sources that include personal (consumer or mortgage) credit, family, friends, and crowd-funding, they also rely on various types of financial institutions (banks and nonbanks). Financial institutions vary in how they are regulated, the business models they adopt, the types of loans they offer, and the growth stages of the small businesses they serve. These differences are all factors involved when evaluating whether shortages exist in the SBL market.

Some lenders are increasingly using business credit scores to assess creditworthiness, and they may deny SBLs due to either a lack of or poor business credit history.16 The SBA since 2014 has also relied upon credit scores to qualify applicants for its 7(a) loan program.17 In 2016, the Small Business American Dream Gap Report found that many businesses failed to understand their business scores or even know that they had one.18 The text box below summarizes the information used to compute credit scores specifically for businesses.19

|

Business Credit Scores Lenders rely on credit reports and scoring systems to determine the likelihood that prospective consumer borrowers will repay their loans. Similarly, firms collect data regarding businesses' financial behaviors that lenders can use to determine whether businesses qualify for commercial loans.20 Some of these data-collection firms produce both business credit reports and risk scores. Although each firm has its own proprietary model for producing credit risk scores, a higher business credit score generally indicates that a business presents lower credit risk. Some of the factors used to determine business credit scores include the following:21

The Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) generally includes federal statutes that relate to consumer credit, but its protections for consumers do not apply to businesses.22 For example, businesses, unlike consumers, are not entitled to free credit reports or credit scores even after an adverse action, such as the denial of a loan request.23 In addition, businesses typically must pay to see their credit reports, and no formal process exists for disputing errors. For these reasons, businesses may have more difficulty correcting errors on their credit reports. |

Types of Small Business Lenders

Because banks have historically been the principal sources for commercial business lending, credit availability is frequently evaluated in terms of banking trends; however, nonbank financial institutions also engage in commercial business and industrial (C&I) lending. The Federal Reserve has reported that smaller firms are more likely than large firms to apply to nonbank lenders for credit.24 Credit unions have become an important source of small business loans in recent years. Likewise, nonbank fintech lenders have become an important source of credit in market segments that banks may have exited (e.g., business loans of $100,000 or less).25

Bank Lending to Small Businesses

Because the types of SBLs made by a bank may be related to its size, this section begins with bank size definitions. Small community banks, which may be defined as having total assets of $1 billion or less, are considered a subset of the larger category of community banks; community banks may be defined as having total assets up to $10 billion.26 Large banks have total assets that exceed $10 billion.

Community banks hold approximately 50% of outstanding SBLs (defined as the share of loans with principal amounts less than $100,000); however, the number and market share of community banks have been declining for more than a decade.27 Overall, the number of FDIC-insured institutions fell from a peak of 18,083 in 1986 to 5,477 in 2018. The number of institutions with less than $1 billion in assets fell from 17,514 to 4,704 during that time period, and the share of industry assets held by those banks fell from 37% to 7%. Meanwhile, the number of banks with more than $10 billion in assets rose from 38 to 138, and the share of total banking industry assets held by those banks increased from 28% to 84%.87 The decline in community banks is meaningful because they have historically been one of the largest sources of funding for small businesses. Furthermore, some academic research suggests that, as banks grow, their enthusiasm for lending to starts-ups and small businesses may diminish.28 In 2015, the Federal Reserve highlighted a decline in the share of community banks' business loan portfolios with initial principal amounts under $100,000, suggesting that these banks were making fewer loans to small businesses.29

Credit Union Lending to Small Business Members

Although some credit unions make SBLs, their commercial lending activities are limited.30 The Credit Union Membership Access Act of 1998 (CUMAA; P.L. 105-219) codified the definition of a credit union member business loan (MBL) and established a commercial lending cap, among other provisions.31 An MBL is any loan, line of credit, or letter of credit used for an agricultural purpose or for a commercial, corporate, or other business investment property or venture. The CUMAA limited (for one member or group of associated members) the aggregate amount of outstanding business loans to a maximum of 15% of the credit union's net worth or $100,000, whichever is greater. The CUMAA also limited the aggregate amount of MBLs made by a single credit union to the lesser of 1.75 times the credit union's actual net worth or 1.75 times the minimum net worth required to be well-capitalized.32 Three exceptions to the credit union aggregate MBL limit were authorized for (1) credit unions that have low-income designations or participate in the Community Development Financial Institutions program;33 (2) credit unions chartered for making business loans; and (3) credit unions with a history of primarily making such loans.

Generally speaking, the volume of credit union MBL lending is minor in comparison to the banking system. As of September 30, 2015, for example, credit unions reportedly accounted for approximately 1.4% of the commercial lending done by the banking system.34 A large credit union—one with $10 million or more in assets—might adopt a business lending model comparable to a small community bank or perhaps a midsize regional bank in the commercial loan market.35 Similar to community banks, approximately 85% of MBLs were secured by real estate in 2013, with some credit unions heavily concentrated in agricultural loans.36 A larger credit union (e.g., $1 billion or more in assets) could originate larger loans relative to most community banks with assets less than $1 billion.37 Despite competition with some banks in certain localities, the credit union system is significantly smaller than the banking system in terms of overall asset holdings and, correspondingly, has a smaller footprint in the broader commercial lending market.38

Marketplace (Fintech) Lending

The share of SBLs originated by nonbank fintech lenders has expanded.39 However, whether the increase in originations reflects an increase in small business lending is unclear because not all fintechs retain their loan originations in their asset portfolios. Fintechs may generate revenues by (1) originating loans and collecting underwriting fees; (2) selling the loans to third-party investors (via adoption of a private placement funding model, discussed in the below text box "Funding Options for Lenders"); and (3) collecting loan servicing fees (from either the borrowers or investors).40 The fintech lending model has attained a competitive edge by streamlining and expediting the more traditional labor- and paper-intensive manual underwriting process by, for example, adopting online application submission and proprietary artificial intelligence for underwriting.41 For this reason, marketplace lending has been both a substitute (providing credit in some loan markets not served by banks) and a complement (via numerous bank partnerships) to the banking system.42 If, for example, a fintech partners with a bank and subsequently transfers (sells) its loan originations to a bank's balance sheet, the loan would be reported as a banking asset; such scenarios make it difficult to isolate fintech firms' impact in the broader SBL market.

Access to Funding in Different Growth Stages

This section explains the relationship between the growth stage of a small business and its access to credit. Start-ups and more established firms are likely to have different experiences obtaining business loans. In addition, underwriting requirements and the degree of loan product customization, which vary among lenders, may also be more suitable for borrowers at different stages. The text box at the end of this section summarizes some funding options for lenders that may also influence their underwriting practices and the types of loans they offer.

Funding for Start-ups

A firm's growth stage matters for credit access. During the initial start-up stage, small businesses typically have little collateral; their financial statements often lack sufficient histories of earnings and tax returns to meet lender requirements; and they typically do not have a performance track record during an economic downturn. As a result, lenders often find it difficult, time-consuming, and costly to determine whether a start-up is creditworthy. For this reason, start-ups often obtain funds from friends and family and drawdowns of personal savings. In addition, start-ups rely on financing from the owner's personal consumer credit products (e.g., credit cards, home equity loans) rather than a traditional commercial loan made by a financial institution.43 According to the Federal Reserve Small Business Credit Survey, which defines a small business as having $1 million or less in annual revenue, 42% of the small business owners surveyed used their personal credit scores to secure a loan and 45% used both their business and personal credit scores.44 Furthermore, having a low business credit score was reported as the number one reason why small businesses were rejected for credit, followed by an insufficient credit history.

Because many small businesses rely on personal credit history and consumer credit products (rather than business credit), declines in consumer credit availability during economic downturns are also likely to affect small businesses' access to credit.45 Home equity credit during the 2007-2009 recession declined along with real estate collateral prices, contributing to tighter lending standards. Likewise, any consumer credit cost increase is likely to affect certain small businesses. For example, given the rise in credit card rates over the recession, small businesses that carried large debt balances over several payment cycles might have paid higher borrowing costs relative to a more conventional business loan.46 Hence, changes in the availability and pricing of consumer credit are likely to have similar effects on consumers and some small businesses, especially start-ups.

Funding for Later-Stage Small Firms

Once a firm enters into a more advanced growth stage, it may have one or more of the following attributes:

- a positive cash flow,

- more than two years of experience,

- a high business credit score, or

- achieves $1 million or more in annual revenues.

Lenders can subsequently provide more mature businesses with one or more loans secured by their assets, supported by their credit and earnings histories. Accordingly, firms in later growth stages tend to have greater access to SBLs. Nevertheless, small firms still are more likely to obtain credit via relationship lending.

Two prevailing commercial lending underwriting models are relationship and transactional lending.47 Small and community banks typically engage in relationship lending (or relationship banking), meaning that they develop close familiarity with their customers (i.e., soft information) and provide financial services within a circumscribed geographical area.48 Relationship lending provides a comparative advantage for pricing lending risks that are unique, infrequent, and localized. A relationship lender may also prefer being in close geographical proximity to the collateral (e.g., local real estate) borrowers used to secure their loans. The nature of the risks requires the loan underwriting process to be more labor-intensive.49

By contrast, large institutions typically engage in transactional lending that frequently relies on automated, statistical underwriting methodologies and large volumes.50 Transactional lending provides a comparative advantage for loan pricing when the borrowers face more conventional business risks (i.e., hard information, such as sales fluctuations, costs of inputs, specific industry factors, and other relevant metrics) rather than idiosyncratic risks that are difficult for an automated underwriting model to quantify. By relying on conventional financial metrics and documentation, transactional lenders do not need to be located near their borrowers to monitor their financial health. Moreover, because underwriting is more automated for these institutions, credit requests are most frequently denied because of (1) weak business performance, (2) insufficient loan collateral, and (3) having too much existing debt outstanding.51

A lender's underwriting model influences the way it defines a small business. As previously mentioned, community banks tend to describe small businesses as those whose owners multitask, meaning that they perform multiple large-scale tasks rather than relying on designated, full-time employees. Small businesses who face these types of challenges are unlikely to provide (in a timely manner) the metrics necessary for automated underwriting and, therefore, tend to be underwritten manually when requesting credit. For manual underwriting, small firms' credit scores are often not essential to evaluate creditworthiness and determine loan terms. Instead, relationship lending allows for more tailoring of loans (e.g., customized lending terms or repayment schedules) to small firms' idiosyncratic needs. Hence, lenders with relationship lending models are likely more well-adapted to underwrite businesses with risks that are unusual and oftentimes difficult to quantify.

By contrast, large banks use metrics such as the dollar amount of annual sales revenues to categorize a small business. Automated underwriting becomes more amenable for businesses with business credit scores and the ability to provide financial documentation in a timely manner. A bank may offer an unsecured credit card loan to a firm with reliable financial performance records, thus reducing the monitoring costs associated with collateralized lending. Furthermore, firms with standardized financials can obtain more standardized (noncustomized) and competitively priced loans, which can be delivered faster. In general, the average costs to originate (and fund) loans decrease as the volume of loans or loan amounts increase. Lenders with transactional lending models can benefit more (relative to manual underwriters) from such economies of scale because their customer bases include more borrowers with standardized and quantifiable risks.

Although they tend to rely on different types of credit, both start-ups and well-established firms may be highly dependent on certain lenders that specialize in underwriting loans for certain industries (e.g., maritime, breweries and distilleries, or moving). In addition, some lenders primarily engaged in transactional underwriting may still rely on relationship lending under some limited circumstances. For example, a larger firm may be willing to relax supplementary financial requirements (known as covenants) designed to reduce credit risk for borrowers with whom the firm has an ongoing relationship. This type of action may be considered a form of manual underwriting.52

|

Funding Options for Small Business Lenders Lenders' underwriting models may correspond with their preferred method to fund their loan originations. Funding loans refers to how lenders acquire the funds to lend. Selected options for lenders to fund loans to small businesses are described below:

|

Attempting to Identify SBL Market Failures

This section attempts to find evidence of market failures that may be addressed by policy interventions. The specific areas of potential concern are (1) whether the lending industry is providing enough small loans for small businesses; (2) whether certain small businesses lack the type of collateral that lenders require to secure the loans; (3) whether the amount of credit provided in low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities is insufficient; and (4) whether the price of credit is too expensive for small businesses.

Shortage of Small Loans

Reviewing the number of small-sized loans may help determine if a SBL market shortage exists, assuming that (1) lenders make small-sized loans to small businesses and (2) an ideal size definition exists. The FDIC provides multiple size definitions of SBLs:

- loans with origination amounts less than or equal to $100,000;

- loans with origination amounts less than or equal to $250,000;

- loans to firms with gross annual revenues less than or equal to $1 million; and

- loans with origination amounts greater than $250,000 to firms satisfying any amenable small business definition.

The FDIC's 2018 Small Business Lending Survey of 1,200 banks uses a C&I loan size limit of $1 million as a proxy for small business lending.

In 2015, the Federal Reserve specifically highlighted the decline of community banks' business loans with initial principal amounts under $100,000.55 The current interest-rate environment, which has been at a historic low since the recent recession, may influence this outcome. In a low-interest-rate environment, even relationship lenders may have a greater incentive to increase loan sizes to generate sufficient interest income to cover the costs of providing them.56 Assuming that the underwriting, servicing, and compliance costs do not vary with loan size, then incurring those fixed costs for larger-sized loans, which may be more likely to generate more interest revenue, may be more economical for lenders. The retreat from the $100,000 loan market might be temporary if interest rates rise in the future. Nonetheless, denials of SBL requests because of a shift in lenders' preferences toward originating larger loans may indicate a market failure.

Attempting to find a proxy for market failure by examining the availability of SBLs of $100,000 or any size threshold is challenging for the following reasons:

- According to the Federal Reserve's Survey of Lending Terms, at the beginning of 2017, the average C&I loan size for all domestic commercial banks (excluding U.S. branches and agencies of foreign banks) was approximately $575,000; the average business loan size at small domestic banks was approximately $123,000; and the average loan size at large domestic banks was approximately $729,000.57 By contrast, at the beginning of 2007 (prior to the 2007-2009 recession), the average C&I loan size for all domestic commercial banks was approximately $379,000; the average business loan size at small domestic banks was approximately $117,000; and the average loan size at large domestic banks was approximately $578,000.58 Despite the 51.7% increase in average C&I loan size for all domestic commercial banks, the average C&I loan size for small commercial banks—which hold approximately 50% of outstanding SBLs—increased by a relatively modest 5.13%. Thus, it is not apparent that the smaller-size SBL market segment has been displaced.

- If lenders increase the total amount of SBLs made at $250,000 or $1 million, for example, while simultaneously making fewer loans of $100,000, then whether that outcome represents an increase or decrease in overall small business lending is subject to debate.59 Similarly, the FDIC noted that even the $1 million loan size limit may underestimate the amount of loans made to small firms. Some small firms (with annual revenues under $1 million) may get loans that exceed $1 million. Some SBLs may be secured by residential real estate and counted as mortgages. Conversely, the data collected may overstate SBLs to small businesses. The financial data on bank C&I loans do not report on loans made to a well-defined group of small firms.60 Instead, the data only report on small loans to all businesses (regardless of size), thus overstating the amount of SBLs, given that large businesses also receive loans of these sizes.

- The demand for $100,000 SBLs (from community banks) may have decreased. For example, technology firms, which represent many start-ups since the 2007-2009 recession, frequently do not purchase large amounts of inventory. Such firms that are able to operate out of the owners' homes may finance operations with personal savings and credit cards.61 Conversely, the demand for large loans may have increased. For example, some firms may determine that obtaining larger-size loans during the current low-interest-rate environment is more economical than having to reborrow at some point in the future at higher lending rates.

In addition to the abovementioned issues, drawing conclusions about SBL shortages based primarily on the lending practices of community banks is premature in the absence of a comprehensive dataset that includes loans made by nonbank lenders. Fintech lenders may be filling the gap in small business lending left by a decline in community banks. Because fintech lenders generally are not required to hold capital against their portfolio loans or can fund via private placement, they may be able to take advantage of opportunities to lend to small businesses that would not generate sufficient profit margins for community banks. Loans retained in fintech lenders' portfolios or funded via private placement, however, are currently not reported to the federal banking regulators. Furthermore, businesses may have multiple loans and often seek credit from multiple lenders. In some cases, small businesses may be able to obtain credit from some lenders and not others, particularly in cases when borrowers inadvertently seek credit from lenders using incompatible underwriting models. In short, the focus on a particular loan size or particular lender type is arguably too narrow for evaluating performance in the SBL market.

Collateral Eligibility for Secured Lending

A market failure may exist if lenders are unwilling to provide loans backed by illiquid collateral (i.e., collateral that cannot be easily liquidated if the borrower fails to repay the loan)—an issue that may disproportionately affect certain small businesses. Banks and credit unions provide business loans via asset-based lending (ABL) guidelines that require firms to pledge assets (e.g., cash, receivables from inventory sales, inventory) as collateral for loans.62 For ABL purposes, federal banking regulators define a SBL as any loan to a small business (as defined by Section 3(a) of the Small Business Act of 1953 [P.L. 83-163 as amended] and implemented by the SBA) or a loan that does not exceed $2 million for commercial, corporate, business, or agricultural purposes.63 A bank typically provides fully collateralized short-term loans (under five years) to firms based upon their performance records (e.g., sufficient credit and earnings histories and assets), and it monitors the risks to the collateral that would need to be liquidated (sold) if the small business experienced financial distress.64 Similarly, credit unions can provide MBLs that comply with NCUA's ABL guidelines.65

Some firms' inventory, however, may not be ideal for ABL guidelines. Collateral that would be difficult to liquidate without losing too much value may not be acceptable. For example, restaurants (a common type of small business) have leases, cooking equipment (likely to resell for less than its initial sale price), and inventories of food that would not generate the income necessary to recoup losses from a loan default.66 Restaurants also have difficulty demonstrating the ability to repay a loan over a period of years. For this reason, lenders may not accept a restaurant's collateral as security for a loan.

In response to this market failure, the SBA administers various programs to facilitate small business credit access (typically loans for up to $5 million and for 5-25 years) for financially healthy firms with collateral or inventory less likely to satisfy ABL requirements.67 Some borrowers that can demonstrate the ability to repay (e.g., minimum business credit score, management experience, minimum levels of cash flow, some collateral, and personal guarantees by the business owners) still may not be able to obtain affordable credit elsewhere (i.e., from other lenders), which might seem paradoxical.68 This may be because the firm's inventory does not turn over at a steady pace (e.g., seasonal merchandise), and a lender would face difficulty quickly liquidating the collateral if the firm became financially distressed. For a fee, the SBA may retain the credit risk of a small business loan up to a certain percentage, and the lender assumes the remaining share of credit risk to ensure incentive alignment during underwriting.69 SBA-guaranteed loans frequently have higher lending rates relative to ABL loans, taking into account the guarantee (and loan servicing) fees charged to borrowers to compensate the federal agency for retaining a majority of the default risk and the additional risk correlated with illiquid collateral.70

Following the recent recession, the SBA has reported an increase in the dollar amount of guaranteed lending over 2013-2018, which might indicate the ability to mitigate more market failures.71 If, however, borrowers fail to repay their loans and it is not possible to recover sufficient fees and proceeds from asset liquidations to cover the losses, then the SBA may need additional appropriations from Congress to account for the shortfall.72 The utility of government intervention in the form of SBA-guaranteed lending, therefore, is debatable. When borrowers are unable to obtain private-sector credit but subsequently repay their SBA loans, that outcome may suggest that a government guarantee helped correct a failure and improve SBL market performance. Conversely, when borrowers are unable to obtain private-sector credit and subsequently default on their SBA loans, that outcome suggests no market failure initially existed in the private SBL market. Monitoring loan performance is useful in distinguishing between a legitimate credit market barrier and an excessive lending risk, but such monitoring can only occur after loans have been originated and guaranteed, which underscores the difficulty of correctly identifying and effectively mitigating market failures.

SBLs and the Community Reinvestment Act

A market failure may exist if lenders make fewer SBLs in low- and moderate-income (LMI) areas than in higher-income areas. The Community Reinvestment Act of 1977 (CRA; P.L. 95-128) was designed to encourage banking institutions to meet the credit needs of their entire communities.73 The federal banking regulatory agencies—the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency—currently implement the CRA. The regulators issue CRA credits, or points, when banks engage in qualifying activities—such as mortgage, consumer, and business lending; community investments; and low-cost services that would benefit LMI areas and entities—that occur within a designated assessment area. These credits are then used to issue each bank a performance rating. The CRA requires these ratings be considered when banks apply for charters, branches, mergers, and acquisitions, among other things.

Under the CRA, the banking regulators award CRA credit to certain SBLs (including small farm loans), provided these loans meet both (1) a size test and (2) a purpose test. Small businesses that receive an SBL must either (1) meet the size eligibility standards for the SBA's Certified Development Company/504 or SBIC programs or (2) have gross annual revenues of $1 million or less to qualify for CRA credit. The loans must also promote community and economic development, as explained in the federal bank regulators' guidelines, to qualify for CRA credit.74

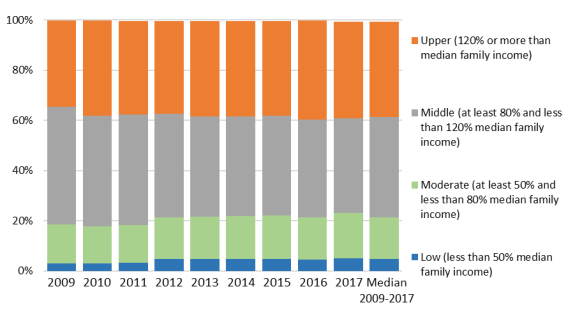

Figure 1 shows the distribution of SBLs for $1 million or less that were eligible for CRA credit over the 2009-2017 period across census tracts grouped into four relative income categories as measured against median family income (MFI).75 For comparison, the last column shows the median percentages of total SBLs over the entire period. The median figures are as follows: 5.2% in the low-income tracts (< 50% of MFI), 16.7% in the moderate-income tracts (50% ≥ MFI < 80%), 40% in the middle-income tracts (80% ≥ MFI <120%), and 37.9% in the upper-income tracts (120% ≥ of MFI). This figure does not capture all CRA business lending because SBLs exceeding $1 million may also receive CRA credit. (In addition, the data in this figure represent a subset of lending activity that occurs in LMI tracts because large C&I loans, as well as consumer loans, may qualify for CRA credit.) Furthermore, changes in the number of SBL or CRA loans could indicate a change in the percentage of CRA credit awarded to SBLs, a change in total SBL originations, or both.

|

Figure 1. Small Business, Small Farm, and Community Development Lending Data |

|

|

Source: Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, at https://www.ffiec.gov/hmcrpr/cra18tables1-5.pdf#Table5. Notes: The small businesses have annual revenues of $1 million or less. The SBLs are for $1 million or less. |

Despite data limitations, the trends suggest that the share of SBLs in LMI areas has remained steady at approximately 20% for almost a decade. Whether that share can increase further—which would suggest that credit may not be accessible for small businesses located in LMI areas—is difficult to determine. For example, the demand for small business credit in LMI areas may be lower relative to higher-income areas. The number of potential businesses and lending opportunities in LMI areas may be comparatively lower if a greater percentage of small businesses locate in areas where their prospective customers would have sufficient incomes to sustain demand for the products or services they offer. In short, the data on SBLs awarded CRA credit do not provide a way to measure the demand for SBLs. There is no information on the number of businesses located in LMI areas that applied for loans and were subsequently rejected, making it difficult to conclude that a failure exists in the SBL market in LMI areas. Accordingly, Congress has called for the collection of data from small business lenders, discussed in more detail in the section entitled "CFPB Collection of Small Business Data."

Small Business Loan Pricing

The pricing of SBLs—specifically interest rates and fees—is another consideration for evaluating the small business credit market's overall performance. A small business might not seek credit if it is too expensive. A small business might determine that it cannot afford an offer for credit if more of its financial resources (e.g., net income) must be devoted to paying interest than reinvesting in operations. When loan prices are set substantially higher than the risks posed by borrowers and the costs to acquire the funds used to make the loans, the pricing is not considered competitive. In economics, a competitive price is one that multiple suppliers would offer to buyers for the same good or service. A competitive price is often the best or lowest that a buyer can find for a good or service and, therefore, can be used as a benchmark price when comparison shopping to evaluate other offers.

Determining whether SBLs are competitively priced is challenging. A common market failure is imperfect information, or information asymmetry—when one party in a transaction has more accurate or more detailed information than the other party. This imbalance can result in inefficient outcomes.76 In the case of the small business credit market, the risks taken by small business owners are not standardized and vary extensively across industries and geographical locations. It is difficult for lenders to determine competitive loan pricing without sufficient comparable businesses from which to obtain reasonable estimates of expected losses and predict cash flows.77 Similarly, it may be difficult for small businesses to determine whether a loan offer is competitive without sufficient comparable business loans.

Relationship lending, as previously discussed, can alleviate an SBL market failure that arises from the inability to price credit risks. Relationship lending allows a lender to collect more information about a borrower's financial behaviors, which may result in less stringent collateral requirements and greater access to credit at a lower price over time.78

Disclosure laws are another way to potentially resolve this type of market failure. In consumer credit markets, the Truth-In-Lending Act of 1968 (TILA; P.L. 90-301) requires lenders to disclose the total cost of credit to consumers in the form of an annual percentage rate (APR). TILA is designed to ensure borrowers are aware of their loan costs. For some consumer products, regulators require lenders to provide greater disclosures about product features that could result in borrowers paying excessive rates and fees, especially in cases where they are unaware of assessed penalty fees and interest-rate increases.79 Effective disclosures arguably mitigate the incentive for lenders to charge substantial markups above funding costs and borrowers' risks, thus resulting in lower loan prices.

Although TILA applies to mortgage and consumer loans, it does not apply to business loans. For this reason, legislative proposals have been introduced in Congress to extend TILA disclosures to small firms. For example, H.R. 5660, the Small Business Credit Card Act of 2018, would extend TILA disclosures to firms with 50 or fewer employees. Whether TILA protections for business credit would result in more competitive business loan terms is unclear. First, evidence suggests that TILA protections do not necessarily encourage consumers to shop for lower borrowing rates despite having more standardized (e.g., collateral) lending risks relative to businesses, suggesting it is unlikely TILA protections for small business would encourage them to shop around for credit.80 Second, some small businesses may already rely on certain types of credit to which TILA does apply. For example, some businesses obtain credit via personal credit cards and home equity loans, to which TILA disclosure requirements already apply. In addition, many lenders already disclose APRs on their business credit cards.81

CFPB Collection of Small Business Data

The Dodd-Frank Act requires financial institutions to compile, maintain, and report information concerning credit applications made by women-owned, minority-owned, and small businesses.82 This data collection is intended to "facilitate enforcement of fair lending laws" and to "enable communities, governmental entities, and creditors to identify business and community development needs and opportunities of women-owned, minority-owned, and small businesses."83 The Dodd-Frank Act authorizes the CFPB to collect various data from financial institutions about the credit applications they receive from small businesses, including the number of the application and date it was received; the type and purpose of loan or credit applied for; the amount of credit applied for and approved; the type of action taken with regard to each application and the date of such action; the census tract of the principal place of business; the business's gross annual revenue; and the race, sex, and ethnicity of the business's principal owners.

On May 10, 2017, the CFPB announced that it was seeking public comment about the small business financing market, including relevant business lending data used and maintained by financial institutions and the costs associated with the collection and reporting of data.84 Specifically, the CFPB requested information on five categories: "(1) small business definition, (2) data points, (3) financial institutions engaged in business lending, (4) access to credit and financial products offered to businesses, and (5) privacy." With respect to definition, the CFPB sought comment on the best definition of a small business and the burden of collecting data under that definition. In addition, the CFPB requested information on what data financial institutions should be required to collect and report, and which institutions should be exempted. The CFPB also requested feedback on product types offered to small businesses because the variety of terms and loan covenants that can be used to tailor loans, in addition to the interest rate, are part of the overall cost (price) of credit. The comment period closed on September 14, 2017. The CFPB has not yet issued a proposed rule, but it recently announced that such a rule was part of its spring 2019 regulatory agenda.85

Evaluating the small business lending market's overall performance (in terms of market failures) would be easier with less fragmented, more complete data. Collecting data, however, poses challenges for the CFPB and industry lenders. First, the Equal Credit Opportunity Act prohibits the collection of race and gender information, thus increasing the difficulty for the CFPB to implement a rule that would require such reporting.86 In addition, the collection and reporting of SBL data would likely need to be converted to a digital format.87 The fixed costs to implement digital reporting systems could be relatively larger for small financial institutions than for large institutions. Large institutions have more customers (to justify the initial expense) and offer a more limited range of standardized products.88 Depending upon the collection requirements eventually implemented, some institutions might decide to offer more standardized, less tailored financial products to reduce reporting costs. It is possible that more financial institutions may require minimum loan amounts (e.g., exit the loan market delineated as $100,000 and below) to ensure that the loans generate enough revenue to cover the costs to fund and report data.

Conclusion

From an economics viewpoint, the ability to evaluate the performance of various SBL market segments—specifically whether (1) a small business credit shortage exists or (2) pricing for loans to small businesses is significantly above the lending risks and funding costs—is extremely challenging. Policymakers have been interested in whether market failures that impede small business access to capital exist and, if so, what policy interventions might address those market failures. However, it is difficult to discern which policy interventions would be most well-suited to addressing potential small business credit market failures without better data about the market itself. Arriving at more definitive conclusions about the availability and costs of SBLs might be possible with information such as the size and financial characteristics of the businesses that apply for loans, the types of loan products they request, the type of lenders to whom they applied, and which applications were approved and rejected. Collecting the necessary data, however, presents both legal and cost challenges.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

Robert Dilger, N. Eric Weiss, Cheryl Cooper, Ronda Mason, Denise Penn, Andrew Schaefer, and Baird Webel made substantive contributions to the report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Report to the Congress on the Availability of Credit to Small Business, September 2012, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/other-reports/availability-of-credit/September-2012-Executive-Summary.htm. See also, Arthur B. Kennickell, Myron L. Kwast, and Jonathan Pogach, Small Business and Small Business Finance during the Financial Crisis and the Great Recession: New Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2015-039, February 27, 2015, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/econresdata/feds/2015/files/2015039pap.pdf. The definition of a small business used in this study was developed from the household responses in the various cross-sectional Surveys of Consumer Finances (SCFs) in 2007 and 2010 and panel reinterview in 2009 with participants from 2007. In addition to collecting detailed information on wealth, the SCFs ask respondents whether they are self-employed, if they own one or more (nonfarm) businesses, and whether they are active or passive managers. |

| 2. |

For more on price theory, see N. Gregory Mankiw, Principles of Microeconomics, 8th ed. (Cengage Learning, 2018). |

| 3. |

See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Report to the Congress on the Availability of Credit to Small Business, September 2017, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/sbfreport2017.pdf. |

| 4. |

See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Report to the Congress on the Availability of Credit to Small Business, September 2017, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/sbfreport2017.pdf. Section 2227 of the Economic Growth and Regulatory Paperwork Reduction Act of 1996 requires that, every five years, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System submit a report to Congress on the small business lending market, including "the demand for credit by small businesses, the availability of credit, the range of credit options available, the types of credit products used, the credit needs of small businesses, the risks of lending to small businesses, and any other factors that the Board deems appropriate." |

| 5. |

See CRS Report RL33243, Small Business Administration: A Primer on Programs and Funding, by Robert Jay Dilger and Sean Lowry; and CRS Report R40985, Small Business: Access to Capital and Job Creation, by Robert Jay Dilger. |

| 6. |

See CRS Report R43661, The Effectiveness of the Community Reinvestment Act, by Darryl E. Getter. |

| 7. |

See Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, "CFPB Explores Ways to Assess the Availability of Credit for Small Business," press release, May 10, 2017, at https://www.consumerfinance.gov/about-us/newsroom/cfpb-explores-ways-assess-availability-credit-small-business/. |

| 8. | |

| 9. |

See "Table of Size Standards," Small Business Administration, at https://www.sba.gov/document/support--table-size-standards; and "Size Standards," Small Business Administration, at https://www.sba.gov/federal-contracting/contracting-guide/size-standards. |

| 10. |

See Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), "SBA Certified Development Company/504 Loan Program," at https://www.occ.treas.gov/topics/community-affairs/publications/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-sba-certified-dev-co-504-loan.pdf; and OCC, "Small Business Investment Companies: Investment Options for Banks, Community Developments," September 2015, at https://www.occ.gov/topics/community-affairs/publications/insights/insights-sbic.pdf. |

| 11. |

See Karen Gordon Mills and Brayden McCarthy, The State of Small Business Lending: Innovation and Technology and the Implications for Regulation, Harvard Business School Entrepreneurial Management Working Paper no. 17-042, November 29, 2016. |

| 12. |

See Tammie Hoy, Jessie Romero, and Kimberly Zeuli, Microenterprise and the Small-Dollar Loan Market, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Economic Brief EB-12-05, May 2012, at https://www.richmondfed.org/-/media/richmondfedorg/publications/research/economic_brief/2012/pdf/eb_12-05.pdf. |

| 13. |

See Internal Revenue Service (IRS), "Small Business and Self-Employed Tax Center," at https://www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed. |

| 14. |

See IRS, "Determining if an Employer is an Applicable Large Employer," at https://www.irs.gov/affordable-care-act/employers/determining-if-an-employer-is-an-applicable-large-employer. |

| 15. |

See Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), 2018 FDIC Small Business Lending Survey, revised December 20, 2018, at https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/sbls/full-survey.pdf. (Hereinafter 2018 FDIC Small Business Lending Survey.) |

| 16. |

See Marco Carbajo, 10 Stats That Explain Why Business Credit is Important for Small Business, SBA, March 9, 2017, at https://www.sba.gov/blogs/10-stats-explain-why-business-credit-important-small-business. |

| 17. |

A small business, in most instances, must have a FICO Small Business Scoring Service (SBSS) score of 140 (but usually 160) out of 300, management experience, minimum indicator of cash flow, some collateral, and personal guarantees by the business owners to qualify for the SBA's flagship 7(a) loan guarantee program. See SBA, Streamlining Small $ Loans, at https://www.sba.gov/sites/default/files/articles/Credit_Scoring_Z-fold_Brochure_20140711.pdf. |

| 18. |

See NAV—Business Credit Reports, "New Research from Nav Reveals Nearly Half of Small Businesses Don't Know Business Credit Scores Exist," press release, November 2, 2016, at https://www.nav.com/blog/half-smb-dont-know-business-credit-scores-exist-1587/; and NAV—Business Credit Reports, Nav's Small Business American Dream Gap Report Reveals Surprising Reason Many Loan Applicants Get Denied, 2015, at https://www.nav.com/insights/. |

| 19. |

For comparison, see CRS Report R44125, Consumer Credit Reporting, Credit Bureaus, Credit Scoring, and Related Policy Issues, by Cheryl R. Cooper and Darryl E. Getter. |

| 20. |

Dun & Bradstreet, FICO, Experian, and Equifax are examples of business credit reporting and scoring firms. |

| 21. |

The determinants listed come from one or more of the following sources: Experian, Business Profile Report, 2010, at https://www.experian.com/assets/business-information/brochures/bpr-training-guide.pdf; NAV—Business Credit Reports, Business Credit Scores & Reports, March 15, 2019, at https://www.nav.com/business-credit-scores/; Fundbox, Guide to Business Credit Scores, 2019, at https://fundbox.com/business-credit-score/; and Claire Tsosie and Steve Nicastro, Business Credit Score 101, Nerdwallet, October 6, 2017, at https://www.nerdwallet.com/blog/small-business/business-credit-score-basics/. |

| 22. |

P.L. 91-508. Title VI, §601, 84 Stat. 1128 (1970), codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. §§1681-1681x. For the legal definition, see 12 C.F.R. §1090.104, "Consumer Reporting Market," at http://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=c13cb74ad55c0e8d6abf8d2d1b26a2bc&mc=true&node=se12.9.1090_1104&rgn=div8. The Fair Credit Reporting Act, the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, and the Equal Credit Opportunity Act are all consumer credit protection amendments included in the Consumer Credit Protection Act (P.L. 90-321). |

| 23. |

See Levi King, "Your Business Credit Report Probably Has Errors: Why and What You Can Do About It," Nav—Business Credit Reports, February 5, 2019, at https://www.nav.com/blog/your-business-credit-report-probably-has-errors-175-1068/; and Michelle Black, "Correcting Incorrect Information on Your Business Credit Reports," Nav—Business Credit Reports, February 21, 2019, at https://www.nav.com/blog/correcting-incorrect-information-on-your-business-credit-reports-33860/. |

| 24. |

The Herfindahl-Hirschman Indexes, a commonly accepted measure of market concentration used by antitrust authorities, have either remained constant or decreased somewhat according to the Federal Reserve. See Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Report to Congress on the Availability of Credit to Small Business, September 2017, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/sbfreport2017.pdf. |

| 25. |

Fintech is an abbreviation for financial technology, and fintech lenders refer to online lenders that are not federally insured depositories (i.e., banks and credit unions). See Julapa Jagtiani and Catharine Lemieux, Do Fintech Lenders Penetrate Areas That Are Underserved by Traditional Banks?, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, WP 18-13, March 2018, at https://www.philadelphiafed.org/-/media/research-and-data/publications/working-papers/2018/wp18-13.pdf. |

| 26. |

See FDIC, FDIC Community Banking Study, December 2012, at https://www.fdic.gov/regulations/resources/cbi/report/cbi-full.pdf. |

| 27. |

Federal Reserve Governor Lael Brainard, "Community Banks, Small Business Credit, and Online Lending," speech at Community Banking Research and Policy Conference, St. Louis, MO, September 30, 2015, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/brainard20150930a.htm. (Hereinafter Governor Lael Brainard, "Community Banks, Small Business Credit, and Online Lending.") |

| 28. |

See Robert DeYoung, Lawrence G. Goldberg, and Lawrence J. White, Youth, Adolescence, and Maturity of Banks: Credit Availability to Small Business in an Era of Banking Consolidation, Department of Finance: New York University, Leonard N. Stern School of Business, October 10, 1997. |

| 29. |

Governor Lael Brainard, "Community Banks, Small Business Credit, and Online Lending." |

| 30. |

Credit unions, which are supervised by the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA), are financial cooperatives that can only make loans to their members, other credit unions, and credit union organizations. See NCUA, The Federal Credit Union Act, revised April 2013, at http://www.ncua.gov/Legal/Documents/fcu_act.pdf. NCUA was created by the Federal Credit Union Act of 1934 (48 Stat. 1216). P.L. 91-468, 84 Stat. 994 made the NCUA an independent agency, which is governed by a three-member board. |

| 31. |

For a discussion of the Supreme Court decision and congressional response to it that resulted in P.L. 105-219, see National Credit Union Administration, Petitioner, v. First National Bank & Trust Co., et al.; AT&T Family Federal Credit Union, et al., Petitioners, v. First National Bank and Trust Co., et al., 118 S. Ct. 927 96-843, 96-847 (1998). See also William R. Emmons and Frank A. Schmid, "Credit Unions and the Common Bond," Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, September/October 1999, at http://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/review/99/09/9909we.pdf. |

| 32. |

At the time of the Credit Union Membership Access Act of 1998 (CUMAA), some Members of Congress were concerned that commercial lending, which is considered riskier than consumer lending, would increase the credit union system's risk profile. In deliberations over the CUMAA, Members expressed concern that a cap calculated as 12.25% (1.75 multiplied by the 7% statutory requirement to be well-capitalized) of a credit union's total assets was too high if small loans (under $50,000) were not counted toward the cap, and Members were also concerned that such an exemption could open up a regulatory arbitrage opportunity enabling chartered credit unions to assume more financial risk and circumvent the cap limitation in the legislation. Hence, the 12.25% lending cap arguably represented a compromise. See additional discussions in U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, Credit Union Membership Access Act, report to accompany H.R. 1151, 105th Cong., 2nd sess., May 21, 1998, S.Rept. 105-193. |

| 33. |

A designated Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) works in financial market niches that are underserved by traditional financial institutions. For more information, see the CDFI website at https://www.cdfifund.gov/programs-training/Pages/default.aspx. |

| 34. |

NCUA, "Member Business Lending; Commercial Lending," 81 Federal Register 13530-13559, March 14, 2016. |

| 35. |

Small credit unions with assets under $10 million are unlikely to become substantial providers of MBLs because it would not be cost effective for them to invest in the necessary underwriting systems for the volume of commercial lending that they would feasibly be able to do. MBLs are perhaps the most complex lending activity for credit unions and would require significant resources that many smaller credit unions would find cost prohibitive. See Testimony of NCUA Chairman Debbie Matz, in U.S. Congress, House Committee on Financial Services, Subcommittee on Financial Institutions and Consumer Credit, H.R. 1418: The Small Business Lending Enhancement Act of 2011, 112th Cong., 1st sess., October 12, 2011, pp. 11-12, at http://financialservices.house.gov/UploadedFiles/101211matz.pdf. |

| 36. |

See NCUA, "Overall Trends," December 31, 2013, at http://www.ncua.gov/legal/documents/reports/ft20131231.pdf. For the sake of comparison, credit unions collectively provided a total of $39.58 billion of MBLs, which equaled 3.87% of credit union assets in December 2012; approximately 84% of MBLs were secured by real estate. (See NCUA, "Overall Trends," December 31, 2012, at http://www.ncua.gov/legal/documents/reports/ft20121231.pdf.) Credit unions with assets of $10 million or less collectively made 458 (or 0.03%) of the MBLs originated by the credit union system in 2012; the median of the average MBL size for this group was approximately $60,000. Credit unions having more than $10 million in assets made the remaining 175,514 (or 99.7%) of the MBLs in 2012. Credit unions with more than $1 billion in assets made 68,088 (or 38.7%) of the MBLs in 2012. The median of the average MBL size in 2012 was $99,228 for credit unions with $10 million to $100 million in assets; $159,396 for credit unions with $100 million to $500 million in assets; $242,079 for credit unions with $500 million to $1 billion in assets; and $303,958 for credit unions with more than $1 billion in assets. These data were provided to the Congressional Research Service (CRS) by the NCUA. |

| 37. |

See Richard G. Anderson and Yang Liu, "Banks and Credit Unions: Competition Not Going Away," Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, The Regional Economist, April 2013, pp. 4-9, at http://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/pub_assets/pdf/re/2013/b/Banks_CreditUnions.pdf. |

| 38. |

See CRS In Focus IF11048, Introduction to Bank Regulation: Credit Unions and Community Banks: A Comparison, by Darryl E. Getter. |

| 39. |

See U.S. Department of the Treasury, Opportunities and Challenges in Online Marketplace Lenders, May 10, 2006, at https://www.treasury.gov/connect/blog/Documents/Opportunities_and_Challenges_in_Online_Marketplace_Lending_white_paper.pdf; and CRS Report R44614, Marketplace Lending: Fintech in Consumer and Small-Business Lending, by David W. Perkins. |

| 40. |

In terms of business lending, some fintech lenders originate the equivalent of signature loans to business owners. Signature loans are frequently described as unsecured personal (consumer) installment loans. In some cases, a signature loan arguably may blur the distinction between a personal and a business loan, especially when originated for an owner (e.g., dentist, barber) of a microbusiness. See Matt Tatham, "What is a Signature Loan?," Experian, September 10, 2018, at https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/what-is-a-signature-loan/. |

| 41. |

See W. Scott Frame, Larry D. Wall, and Lawrence J. White, Technological Change and Financial Innovation in Banking: Some Implications for Fintech, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Working Paper no. 2018-11, October 2018, at https://www.frbatlanta.org/research/publications/wp/2018/11-technological-change-and-financial-innovation-in-banking-some-implications-for-fintech-2018-10-02.aspx. On July 31, 2018, the OCC announced that it would begin accepting applications for national bank charters from fintech firms. A limited-purpose charter may expand opportunities for a fintech lender to develop more of its own long-term customer relationships and operate less as a third-party technology vendor for bank originators. |

| 42. |

See Lawrence H. Summers, "Larry Summers on the Future of Banking," The Washington Post, May 2, 2017, at https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/05/02/larry-summers-on-the-future-of-banking/. Some third-party vender relationships with banking firms have been characterized as partnerships, although many have been considered client-vendor relationships. See Steve Cocheo, "Partner or Vendor? Why It Matters in Fintech World," Banking Exchange, March 22, 2017, at http://m.bankingexchange.com/news-feed/item/6773-partner-or-vendor-why-it-matters-in-fintech-world. |

| 43. |

Funds obtained from family and friends arguably may be considered equity rather than a loan. If the level of risk associated with a business venture is such that a lender is unable to determine an appropriate interest rate to charge commensurate with the risk, then equity may be a more feasible funding alternative at certain growth stages. |

| 44. |

By contrast, only 25% of the large business owners in the survey relied on their personal credit score to secure a loan; 53% used both their business and personal credit scores. See Federal Reserve Banks, Small Business Credit Survey 2016, April 2017, at https://www.newyorkfed.org/smallbusiness/small-business-credit-survey-employer-firms-2016. |

| 45. |

See Arthur B. Kennickell, Myron L. Kwast, and Jonathan Pogach, Small Business and Small Business Finance during the Financial Crisis and the Great Recession: New Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2015-039, February 27, 2015, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/econresdata/feds/2015/files/2015039pap.pdf; and Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Report to the Congress on the Availability of Credit to Small Business 2012, at https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/other-reports/availability-of-credit/September-2012-Executive-Summary.htm. |

| 46. |

Meta Brown et al., The Financial Crisis at the Kitchen Table: Trends in Household Debt and Credit, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Current Issues in Economics and Finance, vol. 19, no. 2, 2013, at https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/current_issues/ci19-2.pdf. |