Immigration: Recent Apprehension Trends at the U.S. Southwest Border

Unauthorized migration across the U.S. Southwest border poses considerable challenges to federal agencies that apprehend and process unauthorized migrants (aliens) due to changing characteristics and motivations of migrants in the past few years. Unauthorized migration flows are reflected by the number of migrants apprehended by the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS’s) Customs and Border Protection (CBP). In FY2000, total annual apprehensions at the border were at an all-time high of 1.64 million, before gradually declining to 303,916 in FY2017, a 45-year low. Apprehensions then increased to 396,579 in FY2018 and 851,508 in FY2019, the highest level since FY2007.

More notably, the character of unauthorized migrants has changed during the past decade. Historically, unauthorized migrant flows involved predominantly single adult Mexicans, traveling without families, whose primary motivation was U.S. employment. As recently as FY2011, Mexican nationals made up 86% of all apprehensions, and relatively few requested asylum. In FY2019, however, “Northern Triangle” migrants from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras comprised 81% of all apprehensions that year. Economic migrants exclusively seeking employment no longer dominate the unauthorized migrant flow, which is now driven to a greater extent by asylum seekers and those escaping violence and domestic insecurity, or those with motivations involving a mixture of protection and economic opportunity.

CBP classifies apprehended unauthorized migrants into single adults, family units (at least one parent/guardian and at least one child), and unaccompanied alien children (UAC). In 2012, single adults made up 90% of apprehended migrants at the Southwest border. In FY2019, however, persons in family units and UAC together accounted for 65% of all apprehended migrants that year. In FY2019, CBP apprehended a record 473,682 persons in family units, exceeding all apprehensions of family unit members from FY2012-FY2018 combined. Mothers headed almost half of all family units apprehended in FY2019. In addition, apprehended persons in family units shifted from mostly Mexican nationals (80%) in FY2012 to mostly Salvadoran, Guatemalan, and Honduran nationals (91%) in FY2019. Similar changes occurred in the origin countries of unaccompanied alien children, whose total apprehensions also reached a record (76,020) in FY2019.

The changing character of the migrant flow has led to logistical and resource challenges for federal agencies, particularly CBP. These include a general capacity shortfall in CBP holding facilities, the lack of appropriate facilities to detain families in Immigration Customs and Enforcement (ICE) detention centers, the reassignment of some CBP personnel who monitor the border to process and respond to migrants in holding facilities, and rapidly expanding immigration court backlogs that delay expeditious proceedings. The changing underlying motivations and border migration strategies of recent migrants also makes apprehension data less useful than in the past for measuring border enforcement. Because many unauthorized migrants now actively seek out U.S. Border Patrol agents in order to request asylum, increases or decreases in apprehension numbers may not reflect the effectiveness of border enforcement strategies.

In response, the Trump Administration has changed existing policies for apprehended migrants, including implementing the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), also known as the “remain in Mexico” immigration policy, which allow DHS to return migrants seeking U.S. admission to the contiguous country from which they arrived on land, pending removal proceedings.

Options for Congress could include legislative responses to the series of policies that the Administration has developed to address the changing flow of migrants at the Southwest border. Some proposals may consider changes to the appropriations of agencies charged with processing unauthorized migrants to reshape the system from one that was designed to apprehend and return single unauthorized adults from Mexico with no claims for protection, to one that can more quickly adjudicate those seeking humanitarian protection. Other options may include greater supervision of unauthorized migrants who are released into the United States, and mandating the collection and publication of more-detailed and timely data from CBP to more completely assess the flow of unauthorized migrants, including those in the MPP program, and their impact on border enforcement and the immigration court system.

Immigration: Recent Apprehension Trends at the U.S. Southwest Border

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- Changing Migration and Apprehension Trends

- Interpreting Apprehensions Data

- Total Apprehensions

- Apprehensions by Country of Origin

- Apprehensions by Demographic Category

- Apprehensions of Family Units by Country of Origin

- Apprehensions of Unaccompanied Alien Children

- Total Apprehensions by Month in FY2019

- Policy Implications

Figures

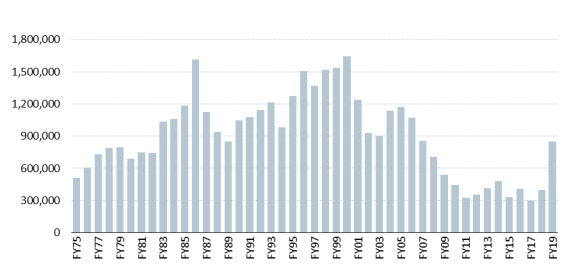

- Figure 1. Total Apprehensions at the Southwest Border, FY1975-FY2019

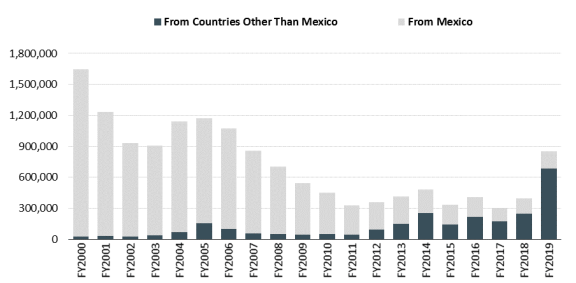

- Figure 2. Total Apprehensions at the Southwest Border, by Country of Origin, FY2000-FY2019

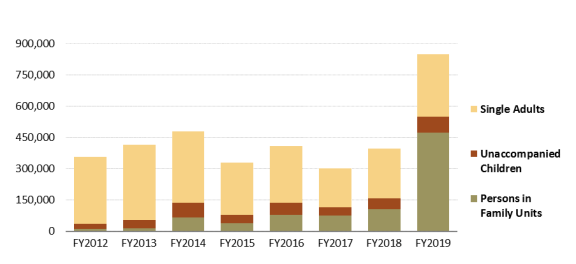

- Figure 3. Total Apprehensions at the Southwest Border, by Demographic Category, FY2012-FY2019

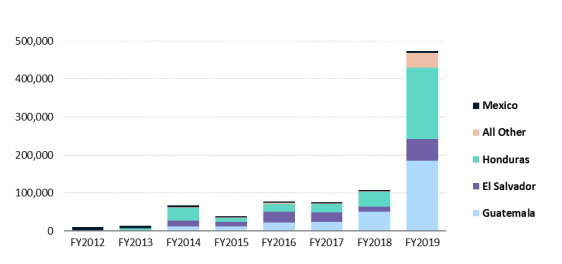

- Figure 4. Family Unit Apprehensions at the Southwest Border, by Country of Origin, FY2012-FY2019

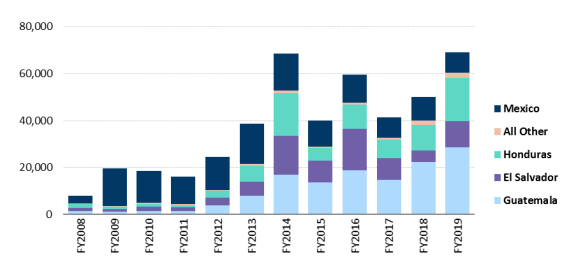

- Figure 5. Unaccompanied Alien Children Apprehensions at the Southwest Border, by Country of Origin, FY2008-FY2019

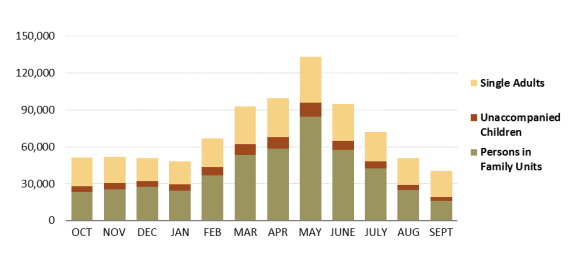

- Figure 6. Total Apprehensions at the Southwest Border, by Month and Demographic Category, FY2019

Summary

Unauthorized migration across the U.S. Southwest border poses considerable challenges to federal agencies that apprehend and process unauthorized migrants (aliens) due to changing characteristics and motivations of migrants in the past few years. Unauthorized migration flows are reflected by the number of migrants apprehended by the Department of Homeland Security's (DHS's) Customs and Border Protection (CBP). In FY2000, total annual apprehensions at the border were at an all-time high of 1.64 million, before gradually declining to 303,916 in FY2017, a 45-year low. Apprehensions then increased to 396,579 in FY2018 and 851,508 in FY2019, the highest level since FY2007.

More notably, the character of unauthorized migrants has changed during the past decade. Historically, unauthorized migrant flows involved predominantly single adult Mexicans, traveling without families, whose primary motivation was U.S. employment. As recently as FY2011, Mexican nationals made up 86% of all apprehensions, and relatively few requested asylum. In FY2019, however, "Northern Triangle" migrants from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras comprised 81% of all apprehensions that year. Economic migrants exclusively seeking employment no longer dominate the unauthorized migrant flow, which is now driven to a greater extent by asylum seekers and those escaping violence and domestic insecurity, or those with motivations involving a mixture of protection and economic opportunity.

CBP classifies apprehended unauthorized migrants into single adults, family units (at least one parent/guardian and at least one child), and unaccompanied alien children (UAC). In 2012, single adults made up 90% of apprehended migrants at the Southwest border. In FY2019, however, persons in family units and UAC together accounted for 65% of all apprehended migrants that year. In FY2019, CBP apprehended a record 473,682 persons in family units, exceeding all apprehensions of family unit members from FY2012-FY2018 combined. Mothers headed almost half of all family units apprehended in FY2019. In addition, apprehended persons in family units shifted from mostly Mexican nationals (80%) in FY2012 to mostly Salvadoran, Guatemalan, and Honduran nationals (91%) in FY2019. Similar changes occurred in the origin countries of unaccompanied alien children, whose total apprehensions also reached a record (76,020) in FY2019.

The changing character of the migrant flow has led to logistical and resource challenges for federal agencies, particularly CBP. These include a general capacity shortfall in CBP holding facilities, the lack of appropriate facilities to detain families in Immigration Customs and Enforcement (ICE) detention centers, the reassignment of some CBP personnel who monitor the border to process and respond to migrants in holding facilities, and rapidly expanding immigration court backlogs that delay expeditious proceedings. The changing underlying motivations and border migration strategies of recent migrants also makes apprehension data less useful than in the past for measuring border enforcement. Because many unauthorized migrants now actively seek out U.S. Border Patrol agents in order to request asylum, increases or decreases in apprehension numbers may not reflect the effectiveness of border enforcement strategies.

In response, the Trump Administration has changed existing policies for apprehended migrants, including implementing the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), also known as the "remain in Mexico" immigration policy, which allow DHS to return migrants seeking U.S. admission to the contiguous country from which they arrived on land, pending removal proceedings.

Options for Congress could include legislative responses to the series of policies that the Administration has developed to address the changing flow of migrants at the Southwest border. Some proposals may consider changes to the appropriations of agencies charged with processing unauthorized migrants to reshape the system from one that was designed to apprehend and return single unauthorized adults from Mexico with no claims for protection, to one that can more quickly adjudicate those seeking humanitarian protection. Other options may include greater supervision of unauthorized migrants who are released into the United States, and mandating the collection and publication of more-detailed and timely data from CBP to more completely assess the flow of unauthorized migrants, including those in the MPP program, and their impact on border enforcement and the immigration court system.

Introduction

Over the past two years, increasing migration across the Southwest border of the United States has posed considerable challenges to U.S. federal agencies charged with apprehending and processing unauthorized migrants.1 From FY2000 to FY2017, unauthorized migration flows—measured in this report by the number of migrants apprehended by the Department of Homeland Security's (DHS's) Customs and Border Protection (CBP)—had been generally declining. Apprehensions statistics historically have been used as a rough measure of trends in unauthorized migration flows, as well as a rough indicator of border enforcement (see "Interpreting Apprehensions Data" below). After reaching an all-time peak of 1,643,679 in FY2000, apprehensions fell to a 45-year low of 303,916 in FY2017. In FY2018 apprehensions increased to 396,579, and in FY2019 they more than doubled to 851,508.

The Administration and some Members of Congress have characterized the recent increases as a border security and humanitarian crisis. For example, then-CBP Commissioner Kevin McAleenan, in testimony to the Senate Judiciary Committee on March 6, 2019, stated

I have heard a number of commentators observe that even with these alarming levels of migration, the numbers are lower than the historical peaks, and as a result, they suggest what we are seeing at the border today is not a crisis.

I fundamentally disagree. From the experience of our agents and officers on the ground, it is indeed both a border security—and a humanitarian—crisis.

What many looking at total numbers fail to understand is the difference in what is happening now in terms of who is crossing, the risks that they are facing, and the consequences for our system.2

The difference McAleenan cited refers to the characteristics of apprehended migrants at the Southwest border—their origin countries, demographic characteristics, and migratory motivations—all of which have changed considerably during the past decade. In prior decades, unauthorized migrant flows involved predominantly adult male Mexicans, whose primary motivation was U.S. employment. If apprehended, they were typically processed through expedited removal3 and quickly repatriated. Relatively few migrants applied for humanitarian immigration relief such as asylum.

Mexican migrants now make up a minority of total apprehensions. Sizable numbers of migrants from the "Northern Triangle"—the Central American countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras—now make up the largest group. Smaller numbers of migrants are also arriving at the Southwest border from South America (e.g., Venezuela, Peru), the Caribbean (e.g., Cuba), Africa (e.g., Cameroon, Uganda), Central Asia (e.g., Uzbekistan), and South Asia (e.g., India, Bangladesh), among other regions.4 Instead of being dominated by adult males, migrant flows over the course of this decade have been increasingly characterized by migrants traveling as families (family units) and unaccompanied alien5 children (UAC).

While a sizeable proportion of unauthorized migrants seek U.S. employment, a growing proportion of arriving migrants are seeking asylum and protection from violence.6 Studies of recent migration trends cite persistent poverty, inequality, demographic pressure related to high population growth, vulnerability to natural disasters, high crime rates, poor security conditions, and the lack of a strong state presence as factors that "push" migrants to make the risky and often dangerous journey from the Northern Triangle.7 "Pull" factors include the increasing use of U.S. asylum policy that, until recently, allowed most asylum seekers to remain in the United States while they awaited a decision on their cases. Lengthy court backlogs8 allow migrants admitted to the United States the opportunity to reunite with family members and acquire work authorization, typically six months after U.S. admission.9 Motivations for leaving Northern Triangle countries and choosing the United States are often a mixture of these push and pull factors, which can be interconnected,10 especially for families and unaccompanied children.

Some observers argue that the recent migrant flows represent a failure of the rule of law. They question the legitimacy of asylum claims being made by recent unauthorized migrants and contend that many are abusing U.S. immigration laws bestowing humanitarian relief in order to gain entry into, or permission to remain in, the United States. Other observers characterize the recent migrant flows as a legitimate international humanitarian crisis resulting from violent and lawless circumstances in migrants' countries of origin. These observers contend that the "crisis" at the border reflects the inability of U.S. federal agencies to adequately process arriving migrants and adjudicate their claims for immigration relief.

The changing character of the migrant flow has reportedly produced a number of logistical and resource challenges for federal agencies.11 These include a general capacity shortfall in CBP holding facilities, lack of appropriate facilities to detain families in ICE detention centers, reassignment of CBP personnel from port of entry duty to responding to migrants in processing facilities, and lengthy immigration court backlogs that delay expeditious proceedings. During migration peaks, these resource constraints—coupled with legal restrictions on the length of time that some migrants may be held12—have forced DHS to release migrants who have entered the United States unlawfully, particularly those in family units, rather than detaining or removing them.13

In response to the large increase in arrivals of migrants without proper entry documents, the Trump Administration has initiated changes to existing policy for apprehended migrants, largely designed to discourage these unauthorized migration flows. In January 2019, the Administration implemented the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), also known as the "remain in Mexico" immigration policy, which allow DHS to return applicants for admission to the United States to the contiguous country from which they arrived (on land) pending removal proceedings.14 The MPP sends migrants back to Mexico to await their court proceedings for the duration of their case.15 This program requires the coordination and assistance of the government of Mexico, a country facing its own high levels of unauthorized migration on its southern border.16 The program is currently operating in six border locations.17

Understanding changing migration patterns over the past decade may help inform Congress as it considers immigration-related legislation. This report discusses recent migrant apprehension trends at the Southwest border. It describes how unauthorized migration to the United States has changed in terms of the absolute numbers of migrants as well as their origin countries, demographic composition, and primary migratory motivations. The report concludes with a brief discussion of related policy implications.

Changing Migration and Apprehension Trends

The Trump Administration's and Congress's responses to the changing characteristics of unauthorized migrants at the Southwest border occur within the context of border security debates. Border security has been an ongoing subject of congressional interest since the 1970s, when unauthorized immigration to the United States first registered as a serious national challenge, and it has received increased attention since the terrorist attacks of 2001. Current debates center on how best to secure the Southwest border, including how and where to place barriers and other tactical infrastructure to impede unauthorized migration as well as the deployment of U.S. Border Patrol agents to prevent unlawful entries of migrants and contraband.18 Securing the border while facilitating legitimate trade and travel to and from the United States is CBP's primary mission;19 major shifts in CBP activities can strain resources and disrupt operations.20

According to U.S. immigration law, foreign nationals who arrive in the United States without valid entry documentation may pursue asylum and related protections if they demonstrate a credible fear of persecution or torture in their country of origin.21 These migrants, along with others either apprehended or refused admission at a port of entry, appear in the statistics kept by CBP (see "Interpreting Apprehensions Data" below).

While CBP's responsibilities include monitoring the Southwest and Northern land borders, as well as the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, the Southwest border with Mexico commands most of the agency's resources because of its attendant risks. The Southwest border runs for nearly 2,000 miles along the four Southwestern states of California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas.22 It is not only the locus of most unauthorized migration to the United States but also that of illicit drugs, counterfeit products, dangerous agricultural products, and trafficked children.23 Much of this activity occurs at U.S. ports of entry at the Southwest border, where CBP officers inspect all individuals and vehicles that seek to enter the United States.

Interpreting Apprehensions Data

CBP's two components that monitor the Southwest border at and between ports of entry—the U.S. Border Patrol (USBP) and the Office of Field Operations (OFO)—collect statistics on individuals who have crossed the border illegally and those who are denied entry. Between ports of entry, USBP agents are responsible for apprehending individuals not lawfully present in the United States.24 OFO officers are responsible for inspections at U.S. ports of entry and collect data on noncitizens who are denied entry to the United States at ports of entry. Migrants typically are denied entry because they are not in possession of a valid entry document or are determined "inadmissible" on one of several grounds, such as having a criminal record, being a potential public safety threat, or being a public health threat.25 Inadmissible migrants made up 27%, 24%, and 13% of all migrants arriving at ports of entries along the Southwest border in FY2017, FY2018, and FY2019, respectively. While the number of inadmissible migrants grew slightly from FY2018 to FY2019, their percentage share of all CBP encounters diminished compared to apprehensions, as absolute numbers of apprehensions more than doubled during that period. (Table 1).26 Both inadmissible and apprehended migrants can be placed in the MPP program.

|

Migrants |

Percentage |

|||||

|

Fiscal Year |

Inadmissible |

Apprehended |

Total |

Inadmissible |

Apprehended |

Total |

|

2017 |

111,275 |

303,916 |

415,191 |

27% |

73% |

100% |

|

2018 |

124,511 |

396,579 |

521,090 |

24% |

76% |

100% |

|

2019 |

126,001 |

851,508 |

977,509 |

13% |

87% |

100% |

Apprehensions statistics historically have been used as a rough measure of trends in unauthorized migration flows.27 The utility of these statistics for measuring border enforcement effectiveness, on the other hand, has long been considered of limited usefulness because of the unknown relationship between apprehensions and successful unlawful entries, among other reasons.28 Apprehensions data, by definition, do not include illegal border crossers who evade USBP agents. They also do not account for the number of potential migrants who are discouraged from attempting U.S. entry because of enforcement measures.29 Consequently, it is generally unclear if an increase in apprehensions results from more attempts by migrants to enter the country illegally or from a higher apprehension rate of those attempting to enter the United States illegally—or both.

However, these statistics are arguably now less relevant than in previous years as a metric of border security efforts. In the past several years, an indeterminate but sizable share of migrants who cross between U.S. ports of entry have actively sought out U.S. Border Patrol agents in order to "turn themselves in" to request asylum.30 In prior years, such migrants typically would have attempted to evade USBP agents. As such, CBP's classification of these migrants as apprehensions may overstate the degree to which the agency's resources, personnel, and strategies prevent migrants from crossing the border illegally and entering the United States.

Total Apprehensions

The number of total apprehensions has long been used as a basic measure of migration pressure and border enforcement. Total annual apprehensions at the Southwest border averaged 687,639 during the 1970s; 999,476 during the 1980s; 1,266,556 during the 1990s; and 1,020,143 during the 2000s; but then declined to 427,766 during the 2010s.31 Annual apprehensions reached a 45-year low in FY2017 (303,916). In FY2018, total apprehensions increased to 396,579; and in FY2019, they more than doubled to 851,508, the highest level since FY2007 (see Figure 1). While high relative to annual apprehensions during the past decade, the FY2019 level is lower than annual apprehension levels for 25 of the past 45 years. Thus, recent changes in the character of the migrant flows during the past decade occurred within the context of historically low numbers of apprehensions since FY2000.

|

Figure 1. Total Apprehensions at the Southwest Border, FY1975-FY2019 |

|

|

Sources: U.S. Customs and Border Protection. FY1975-FY2018: "U.S. Border Patrol Fiscal Year Southwest Border Sector Apprehensions (FY 1960 - FY 2018)," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/media-resources/stats; FY2019: "Southwest Border Migration FY2019," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration/fy-2019. |

Apprehensions at the Southwest border initially peaked at 1.62 million in 1986, the same year that Congress enacted the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), which gave lawful permanent resident status32 to roughly 2.7 million unauthorized aliens residing in the United States.33 After declining substantially for a few years, apprehensions rose again, climbing from 0.85 million in FY1989 to an all-time high of 1.64 million in FY2000. Apprehensions generally fell after that (with the exception of FY2004-FY2006), reaching a then-low point of 327,577 in FY2011. Since that year, apprehensions have fluctuated, as noted above.

Apprehensions by Country of Origin

The national origins of apprehended migrants have shifted considerably during the past two decades (see Figure 2). In FY2000, for example, almost all of the 1.6 million aliens apprehended at the Southwest border (98%) were Mexican nationals, and relatively few requested asylum.34 As recently as FY2011, Mexican nationals made up 86% of all 327,577 Southwest border apprehensions in that year.

That share has declined, however, and for most years after FY2013, Mexicans accounted for less than half of total apprehensions on the Southwest border. In FY2019, "other-than-Mexicans" comprised 81% of all 851,508 apprehensions. From FY2012 to FY2019,35 the number of Mexican nationals apprehended dropped by 37%, from 262,341 to 166,458, while the number of migrants apprehended from all other countries increased six-fold, from 94,532 to 685,050.36

|

Figure 2. Total Apprehensions at the Southwest Border, by Country of Origin, FY2000-FY2019 (Country of origin is either Mexico or other than Mexico) |

|

|

Sources: U.S. Customs and Border Protection. FY2000-FY2018: "U.S. Border Patrol Apprehensions From Mexico and Other Than Mexico (FY 2000 - FY 2018)," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/media-resources/stats; FY2019: "U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector Fiscal Year 2019," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions-fy2019. The FY2019 "From Countries Other than Mexico" figure was computed by summing apprehensions of Mexican national single adults, family units, and unaccompanied alien children, and subtracting that sum from total apprehensions. |

Apprehensions by Demographic Category

CBP classifies apprehended unauthorized migrants into three demographic categories: single adults, family units (at least one parent/guardian and at least one child), and unaccompanied alien children (UAC).37 Of the three categories, apprehensions of persons in family units have increased the most in absolute terms since FY2012, the first year for which publicly available CBP data differentiated among the three demographic categories (see Figure 3).

In FY2012, 321,276 single adults made up 90% of the 356,873 arriving migrants apprehended at the Southwest border, while members of family units numbered 11,116, and UAC accounted for 24,481.38 By FY2019, however, apprehensions of persons in family units numbered 473,682, more than all family unit apprehensions from FY2012 to FY2018 combined.39 Together in FY2019, those persons in family units as well as UAC (76,020 apprehensions) accounted for 65% of all apprehensions while the remaining 35% (301,806) were single adults, of whom 84% were men.40 Approximately 48% of family units apprehended in FY2019 were headed by mothers, 44% were headed by fathers, and about 8% were headed by two parents.41

|

Figure 3. Total Apprehensions at the Southwest Border, by Demographic Category, FY2012-FY2019 |

|

|

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection. FY2012-FY2016: "United States Border Patrol Southwest Family Unit Subject and Unaccompanied Alien Children Apprehensions Fiscal Year 2016, Statement by Secretary Johnson on Southwest Border Security," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/southwest-border-unaccompanied-children/fy-2016; FY2017-FY2019: "U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions. Notes: Family unit apprehensions represent apprehended individuals in family units, not apprehended families. |

Apprehensions of Family Units by Country of Origin

As the number of apprehensions of individuals in family units has increased in recent years, their national origins have shifted from mostly Mexican, (comprising 80% of all 11,116 family unit apprehensions in FY2012), to mostly Salvadoran, Guatemalan, and Honduran, who together made up 91% of all 457,871 such apprehensions in FY2019 (see Figure 4). Apprehensions of individuals in family units from El Salvador increased from 636 (6%) of all such apprehensions in FY2012 to 27,114 (35%) of all 77,674 of such apprehensions in FY2016 before declining to 54,915 (12%) in FY2019. Over the same period, the share of family unit apprehensions from Honduras (513) and Guatemala (340) each grew from less than 5% of the total in FY2012 to 188,416 and 185,233, respectively, about 39% each of the total in FY2019. By comparison, the 6,004 apprehensions of Mexicans in family units made up 1% of the total in FY2019.

Notably, the percentage of persons in family units from "all other countries," has been relatively low over the same period. In absolute numbers, this category registered less than 4,000 apprehensions in all years prior to FY2019, but rose to 37,132 family unit apprehensions in FY2019 (7% of the total, the same share as in FY2012).

|

Figure 4. Family Unit Apprehensions at the Southwest Border, by Country of Origin, FY2012-FY2019 |

|

|

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection. FY2012-FY2016: "United States Border Patrol Southwest Family Unit Subject and Unaccompanied Alien Children Apprehensions Fiscal Year 2016, Statement by Secretary Johnson on Southwest Border Security," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/southwest-border-unaccompanied-children/fy-2016; FY2017-FY2019: "U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions. Notes: Family unit apprehensions represent apprehended individuals in family units, not apprehended families. |

Apprehensions of Unaccompanied Alien Children

Over the past decade, the number of unaccompanied alien children apprehended at the Southwest border has increased considerably (see Figure 5). From FY2011 to FY2014, UAC apprehensions increased each year, and more than quadrupled from 16,067 in FY2011 to 68,541 in FY2014. From FY2014 to FY2018, UAC apprehensions fluctuated, declining to 39,970 in FY2015; increasing to 59,692 in FY2016; declining again to 41,435 in FY2017; and increasing again to 50,036 in FY2018. In FY2019, UAC apprehensions reached 76,020, a level that exceeds the previous peak in FY2014.42 In FY2019, approximately 30% of apprehended UAC were girls.43

In the past decade, the country-of-origin composition of apprehended UAC, like that of family units, has shifted from mostly Mexican to mostly Salvadoran, Guatemalan, and Honduran.44 For example, in FY2009 Mexican UAC (16,114) made up 82% of all 19,668 UAC apprehensions in that year, while Salvadoran (1,221), Guatemalan (1,115), and Honduran (968) UAC made up 6%, 6%, and 5%, respectively, of the total. In contrast, by FY2019 Mexican UAC (10,487) made up 14% of all 76,020 UAC apprehensions in that year, while Salvadoran (12,021), Guatemalan (30,329), and Honduran (20,398) UAC made up 16%, 40%, and 27%, respectively, of the total.

|

Figure 5. Unaccompanied Alien Children Apprehensions at the Southwest Border, by Country of Origin, FY2008-FY2019 |

|

|

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection. FY2008-FY2009: "Juvenile and Adult Apprehensions—Fiscal Year 2013;" FY2010-FY2018: "U.S. Border Patrol Total Monthly UAC Apprehensions by Sector," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/media-resources; FY2019: "U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector Fiscal Year 2019," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions. |

Current statute treats children from contiguous countries (Mexico and Canada) differently than children from non-contiguous countries. While UAC from Mexico can be repatriated promptly through a process known as voluntary departure, UAC from all other countries are placed in formal removal proceedings. The latter are then referred to the Department of Health and Human Services' (HHS') Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), where they are initially sheltered and subsequently placed with family members or sponsors while they await their immigration hearing. Hence, the shift in the country-of-origin composition of the apprehended UAC population has had considerable impact on agencies charged with the processing and care of these children.

Total Apprehensions by Month in FY2019

Over the past two decades, apprehensions have followed a pattern consistent with a seasonal migration cycle. In this cycle, peak numbers of apprehensions occur in the spring months (March–June), followed by progressively lower numbers in the hotter summer months (July–September), lower-than-average numbers through the fall months (October–December), and even lower numbers in January, before rising again through the spring months when the pattern begins to repeat.45

|

Figure 6. Total Apprehensions at the Southwest Border, by Month and Demographic Category, FY2019 |

|

|

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection, "U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector Fiscal Year 2019," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions. |

During FY2019, the monthly pattern in total apprehensions at the Southwestern border was similar to the trends during the past two decades (see Figure 6). From the peak in May through September of FY2019, apprehensions declined nearly 70%, from approximately 133,000 to just over 40,000.

These data suggest that the declines in monthly apprehensions from May to September of FY2019 stemmed primarily from declining numbers of family unit apprehensions. The number of persons in family units apprehended on a monthly basis dropped from 84,490 in May to 15,824 in September (an 81% decrease). For UAC, apprehensions declined by 72%, from 11,475 in May to 3,165 in September. Apprehensions of single adults saw a smaller decline (42%) over this period, from 36,894 in May to 21,518 in September.

These patterns suggest that declining apprehensions in recent months may have resulted not only from the immigration enforcement policies of the Trump Administration but also from decades-long seasonal migration patterns, among other factors.46

Policy Implications

This report has described the following major shifts in the composition and character of migrant flows to the Southwest border that have unfolded in less than a decade:

- In the past two years, the number of total apprehensions has increased substantially, a reverse of the general trend of declining and relatively low apprehension levels seen since FY2001.

- The unauthorized migrant flow apprehended at the Southwest border no longer consists primarily of individuals from Mexico, a country with whom the United States shares a border and close economic and historical ties. It now originates largely from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. Also, growing numbers of unauthorized migrants are originating from Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean.

- The unauthorized migrant flow is no longer dominated by economic migrants exclusively seeking employment. It is now driven to a larger extent than in past years by asylum seekers and others with similar motivations, such as escaping violence and domestic insecurity, who may also be interested in working in the United States. Such migrants often seek out U.S. Border Patrol agents at the border when crossing illegally between U.S. ports of entry rather than attempting to elude them.

- The unauthorized migrant flow no longer consists primarily of single adult migrants but rather of families and children traveling without their parents.

Although not previously discussed, changing migration strategies are also altering how federal agencies respond to migrant flows. For example, migrants have been increasingly traveling in large groups, reportedly to protect themselves from harm.47 In addition, more migrants are arriving at remote CBP outposts along the Southwest border, sometimes overwhelming the relatively few CBP personnel who staff them.48

These changing patterns at the Southwest border have considerable policy implications. In comparison with apprehended single adult economic migrants from Mexico, more-recently apprehended migrants require lengthier processing and create a call for greater resources and personnel of more federal agencies. When migrants originate from countries other than the contiguous countries of Mexico and Canada, their removals involve longer processing time, higher transportation costs, and more involved inter-agency coordination. If arriving migrants are unaccompanied alien children from noncontiguous countries, they are protected from immediate removal by statutes that require them to be put into formal immigration removal proceedings and they are referred to the care and custody of ORR.49 If migrants seek asylum, they generally require a credible fear hearing.50 They may be detained in DHS facilities for varying periods51 and must be processed by DOJ's Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR).52

CBP, among all federal agencies, is arguably the most affected by the break with historical migration patterns. The pressures of large groups of migrants arriving together and the greater vulnerabilities of new arrivals are reportedly testing CBP's border infrastructure, agency personnel, and long-standing policies. When unauthorized migrant flows consist largely of families and children, who often arrive in large groups or at remote U.S. border locations, CBP has adjusted its operations and allocated resources and personnel to accommodate more vulnerable migrants. Some studies also suggest that smuggling guides sometimes direct migrants to cross in specific locations to outmaneuver USBP agents and infrastructure and avoid detection.53 Moreover, anecdotal evidence suggests migrant arrival strategies can be based upon perceptions of differences in border enforcement policies and practices among and within the nine CBP Southwest border sectors.54 If enforcement policies vary by sector, CBP can expect migration patterns to shift to sectors that migrants perceive as offering them the greatest chance of acquiring the immigration relief they seek.

The Trump Administration has changed immigration enforcement policies and practices at the border in an attempt to reduce unauthorized migration and discourage fraudulent or frivolous claims for humanitarian immigration relief. President Trump, DHS, DOD, and DOJ have acted together with a series of policy changes that make it more difficult for migrants to be awarded asylum. For example, see the following:

- In November 2018, the President issued a proclamation to suspend immediately the entry into the United States of aliens who cross the Southwest border between ports of entry.55 This proclamation has been challenged in court and a preliminary injunction was issued by a federal district court.56

- As noted above, DHS implemented the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) in January 2019, and for the past several years CBP has also used the practice of "metering" migrants. Both of these policies require migrants to wait on the Mexican side of the border.57

- Since April 2018, National Guard personnel have supported DHS at the border, while active duty personnel began providing support in October 2018.58 In February 2019, President Trump proclaimed a national emergency pursuant to the National Emergencies Act in order to fund a physical barrier at the Southwest border with Mexico using $6.1 billion in funds from the Department of Defense (DOD).59 In September 2019, the Secretary of Defense deferred funding for military construction projects in order to redirect funds to border barrier projects using his authority under the emergency statute 10 U.S.C., Section 2808.60

- In July 2019, DHS and DOJ jointly issued an interim final rule (IFR)61 that makes aliens ineligible for asylum in the United States if they arrive at the Southwest border without first seeking protection from persecution in other countries through which they transit.62

- In addition, the United States is working with Mexico to decrease Central American migrant flows63 and with Central American governments to promote economic prosperity, improve security, and strengthen regional governance.64

The changing character of recent migrant flows at the Southwest border also may suggest that apprehensions may be less useful than in the past for measuring border enforcement. Because many apprehended migrants now actively seek out U.S. Border Patrol agents in order to request asylum, increases or decreases in apprehension numbers may not reflect the effectiveness of border enforcement strategies. Rather, an increase in apprehensions combined with the changing characteristics of recently apprehended migrants may increasingly portend greater resource needs for federal agencies because the administrative requirements for asylum claims are more resource-intensive than those for unauthorized migrants who do not request asylum and are quickly repatriated through expedited removal. The challenge of deterring unauthorized migrants from entering the United States has been complicated and overshadowed by the challenge of processing, in a fair and timely manner, relatively greater numbers of migrants seeking asylum.65

Recent migration research suggests that forced migration from civil conflict, violence, weather events, and climate change is playing a more prominent role in worldwide migratory patterns.66 To some extent, patterns described in this report are consistent with that trend. Declining birth rates in parts of Latin America and improving employment prospects in Mexico over the past decade have reduced the relative proportion of single adult migrants whose primary motivation is U.S. employment.67 In contrast, relatively high levels of violence and lack of public security, among other factors, have increased the relative proportion of Central American and Mexican families and children whose primary migratory motivation is humanitarian relief.

Options for Congress could include legislative responses to the series of policies that the Administration has developed to address the changing flow of migrants at the Southwest border. Some proposals may consider changes to the appropriations of agencies charged with processing unauthorized migrants to reshape the system from one that was designed to apprehend and return single unauthorized adults from Mexico with no claims for protection, to one that can more quickly adjudicate those seeking humanitarian protection. Other options may include greater supervision of unauthorized migrants who are released into the United States,68 and mandating the collection and publication of more-detailed and timely data from DHS to more completely assess the flow of unauthorized migrants, including those in the MPP program, and their impact on border enforcement and the immigration court system.

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

As used in this report, a migrant is a person who has temporarily or permanently crossed an international border, is no longer residing in his or her country of origin or habitual residence, and is not recognized as a refugee. Migrants may include asylum seekers. The term migrant is not defined in statute. |

| 2. |

CBP Commissioner Kevin K. McAleenan, Oversight of Customs and Border Protection's Response to the Smuggling of Persons at the Southern Border, Department of Homeland Security, Testimony before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, March 6, 2019. |

| 3. |

Expedited removal is a streamlined removal process for unauthorized aliens that was established by Congress in 1996. For more information, see CRS Report R45314, Expedited Removal of Aliens: Legal Framework. |

| 4. |

CRS interviews with CBP officials, McAllen, TX, August 14, 2018; San Diego, CA, August 15, 2018; El Paso, TX, August 12, 2019; and Nogales, AZ, August 14, 2019. |

| 5. |

Under §101(a)(3) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (8 U.S.C. §1101(a)(3)), an alien is a person who is not a U.S. citizen or a U.S. national. The definition includes persons legally and not legally present in the United States. In this report, the terms alien, foreign national, and noncitizen are synonymous. |

| 6. |

See CRS Report R45489, Recent Migration to the United States from Central America: Frequently Asked Questions; and CRS Report R43628, Unaccompanied Alien Children: Potential Factors Contributing to Recent Immigration. |

| 7. |

See, for example, CRS In Focus IF11151, Central American Migration: Root Causes and U.S. Policy; CRS Report R45489, Recent Migration to the United States from Central America: Frequently Asked Questions; archived CRS Report R43628, Unaccompanied Alien Children: Potential Factors Contributing to Recent Immigration; and Randy Capps, Doris Meissner, and Ariel G. Ruiz Soto, et al., From Control to Crisis: Changing Trends and Policies Reshaping U.S.-Mexico Border Enforcement, Migration Policy Institute, August 2019. |

| 8. |

At the end of FY2019, DOJ's Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) listed 987,274 pending cases. |

| 9. |

See, for example, Carrie Kahn, "Caravan Of Central American Migrants Seeking Asylum Hope To Cross Border," NPR, April 29, 2018; Alicia A. Caldwell, "As Migration From Guatemala Surges, U.S. Officials Seek Answers," Wall Street Journal, October 13, 2018; and Andrew R. Arthur, "Looking for Push Factors in Central America: The pull factors are likely stronger, but at least CBP is trying," Center for Immigration Studies, October 18, 2018. |

| 10. |

For a discussion of how these factors are often connected, see Matthew Lorenzen, "Unaccompanied Child Migrants," Journal on Migration and Human Security, vol. 5, no. 4 (2017), pp. 744-767. |

| 11. |

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, "Press Briefing by Acting CBP Commissioner Mark Morgan," press release, November 14, 2019. |

| 12. |

While DOJ and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) have broad statutory authority to detain adult aliens, children must be detained according to guidelines established in the Flores Settlement Agreement, the Homeland Security Act of 2002, and the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008. A 2015 judicial ruling held that children remain in family immigration detention for no more than 20 days. If parents cannot be released with them, children are treated as unaccompanied alien children and transferred to the Department of Health and Human Services' (HHS's) Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) for care and custody. For more information, see CRS Report R45297, The "Flores Settlement" and Alien Families Apprehended at the U.S. Border: Frequently Asked Questions. |

| 13. |

Testimony of CBP Commissioner Kevin K. McAleenan, in U.S. Congress, Senate Judiciary Committee, Oversight of Customs and Border Protection's Response to the Smuggling of Persons at the Southern Border, 116th Cong, 1st sess., March 6, 2019. |

| 14. |

Section 235(b)(2)(C) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) provides such authorization. Guiding principles from DHS were released in January 2019, see https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2019-Jan/MPP%20Guiding%20Principles%201-28-19.pdf. |

| 15. |

For more information, see CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10251, "Migrant Protection Protocols": Legal Issues Related to DHS's Plan to Require Arriving Asylum Seekers to Wait in Mexico; and DHS, Assessment of Migrant Protection Protocols, 2019. |

| 16. |

For more on Mexico's immigration trends, policies, and agreements with the United States, see CRS In Focus IF10215, Mexico's Immigration Control Efforts. |

| 17. |

See U.S. Department of Homeland Security, "DHS Expands MPP Operations to Eagle Pass," press release, October 28, 2019, https://www.dhs.gov/news/2019/10/28/dhs-expands-mpp-operations-eagle-pass. For a more detailed examination of the MPP, including some information on the more than 55,000 individuals in the program, see U.S. Department of Homeland Security, "DHS Assessment of Migrant Protection Protocols, 2019." |

| 18. |

See CRS Report R42138, Border Security: Immigration Enforcement Between Ports of Entry; and CRS Report R43356, Border Security: Immigration Inspections at Ports of Entry for more on border security. |

| 19. |

U.S. Customs and Border Protection, "About CBP," https://www.cbp.gov/about. |

| 20. |

For example, on April 1, 2019, then-Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen M. Nielsen issued a memorandum to order CBP Commissioner Kevin McAleenan to undertake emergency surge operations and increase the temporary reassignment of personnel and resources from across the agency to address a large influx of migrants. As a result, 750 Border Patrol officers were subsequently sent to the Southwest border. See U.S. Department of Homeland Security, "Secretary Nielsen Orders CBP to Surge More Personnel to Southern Border, Increase Number of Aliens Returned to Mexico," press release, April 1, 2019; and Julian Aguilar, "Long delays at border bridges bring anxiety for businesses as Holy Week begins," Texas Tribune, April 15, 2019. |

| 21. |

See CRS In Focus IF11074, U.S. Immigration Laws for Aliens Arriving at the Border; and CRS Report R45539, Immigration: U.S. Asylum Policy. |

| 22. |

For more information, see CRS Insight IN11040, Border Security Between Ports of Entry: Homeland Security Issues in the 116th Congress. |

| 23. |

See, for example, CRS In Focus IF11279, Illicit Drug Flows and Seizures in the United States: In Focus; CRS In Focus IF10400, Transnational Crime Issues: Heroin Production, Fentanyl Trafficking, and U.S.-Mexico Security Cooperation; CRS Report R43356, Border Security: Immigration Inspections at Ports of Entry; and CRS Report RL33200, Trafficking in Persons in Latin America and the Caribbean. |

| 24. |

CBP defines apprehensions as "the physical control or temporary detainment of a person who is not lawfully in the U.S. which may or may not result in an arrest"; see https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/cbp-enforcement-statistics. |

| 25. |

For more information on grounds of inadmissibility, see archived CRS Report R43892, Alien Removals and Returns: Overview and Trends. CBP reports apprehensions and "inadmissibles" both together and separately. This report examines apprehensions data (those apprehended between ports of entry) hereinafter. See U.S. Department of Homeland Security, United States Border Patrol, "Stats and Summaries," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration. |

| 26. |

Because of the limited number of years of publicly available data from CBP, inadmissible migrants are not discussed further in this report. This report examines apprehensions data (those apprehended between ports of entry) hereinafter. See U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Border Patrol, "Stats and Summaries," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration. |

| 27. |

Border Patrol apprehensions data count events rather than people. Thus, for example, one unauthorized migrant caught trying to enter the country on three separate occasions during the same fiscal year counts as three apprehensions. For more information, see archived CRS Report R44386, Border Security Metrics Between Ports of Entry. |

| 28. |

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Border Security Metrics Report, February 26, 2019, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/ndaa_border_metrics_report_fy_2018_0_0.pdf (hereinafter, "DHS, Border Security Metrics Report, 2019"). |

| 29. |

See DHS, Border Security Metrics Report, 2019; and Stephanie Leutert and Sara Spaulding, "How Many Central Americans are Traveling North," Lawfare, March 14, 2019, https://www.lawfareblog.com/how-many-central-americans-are-traveling-north. |

| 30. |

See, for example, Alicia Caldwell, "Along the Border, Migrant Mothers Turn Themselves In to Immigration Authorities," Wall Street Journal, June 26, 2018; and Astrid Galvan, "AP Explains: What happens when migrants arrive at US border," APNews, June 26, 2019. |

| 31. |

Averages computed by CRS. See Figure 1 for data sources. |

| 32. |

A lawful permanent resident (LPR) is a foreign national who has been approved to live and work permanently in the United States. |

| 33. |

For more information, see CRS Report R42138, Border Security: Immigration Enforcement Between Ports of Entry. |

| 34. |

DHS, Border Security Metrics Report, 2019. |

| 35. |

This period corresponds to that of publicly available data from DHS differentiating apprehensions of unauthorized migrants according to demographic category shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4, below. |

| 36. |

CBP Acting Commissioner Mark Morgan stated in a White House press briefing that in October 2019 the number of Mexican migrants apprehended with those determined inadmissible exceeded the number from the Northern Triangle countries combined for the first time in 18 months; U.S. Department of Homeland Security, "Press Briefing by Acting CBP Commissioner Mark Morgan," press release, November 14, 2019, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/press-briefing-acting-cbp-commissioner-mark-morgan-2/. |

| 37. |

CBP defines a family unit as "individuals (either a child under 18 years old, parent, or legal guardian) apprehended with a family member by the U.S. Border Patrol." U.S. Customs and Border Protection, "Southwest Border Migration FY2019," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration. Family unit apprehensions represent apprehended individuals in family units, not apprehended families. An unaccompanied alien child (UAC) is defined in statute as a child who has no lawful immigration status in the United States; has not attained 18 years of age; and with respect to whom there is no parent or legal guardian in the United States, or there is no parent or legal guardian in the United States available to provide care and physical custody; 6 U.S.C. §279(g)(2). CBP classifies a child arriving at the border without a parent or legal guardian as an unaccompanied alien child. Children arriving with relatives other than parents, including grandparents, siblings, aunts and uncles, are not considered to be in family units and are treated as unaccompanied. Single adults are individuals at least 18 years of age who are not part of a family unit. |

| 38. |

According to former CBP Commissioner Kevin McAleenan, "single adult males used to make up over 90% of arriving aliens in past years." Testimony of CBP Commissioner Kevin McAleenan, in U.S. Congress, House Committee on Homeland Security, Subcommittee on Border and Maritime Security, Border Security, Commerce and Travel: Commissioner McAleenan's Vision for the Future of CBP, 115th Cong., 2nd sess., April 25, 2018. |

| 39. |

ICE's Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) have described an increasing number of migrants "presenting" at the border as family units that are composed of unrelated individuals since spring of 2018. Many individuals in family units who request asylum have been released into the U.S. interior with a court date (via a Notice to Appear (NTA)), often well into the future. This may provide an incentive for families to send children with unrelated individuals posing as parents, and for adults wanting to gain entry to arrive with a child to whom they are not related. A press release from October 17, 2019, states that a six-month operation in the El Paso sector identified 238 families without verifiable relationships: https://www.ice.gov/news/releases/ice-hsi-el-paso-usbp-identify-more-200-fraudulent-families-last-6-months. |

| 40. |

CBP data tabulation on gender provided to CRS on request, October 31, 2019. |

| 41. |

CBP data tabulation provided to CRS on request, October 31, 2019. All numbers are approximate. |

| 42. |

U.S. Customs and Border Protection, "Southwest Border Migration FY2019," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration. |

| 43. |

CBP data tabulation provided to CRS on request, October 31, 2019. |

| 44. |

For more information, see CRS Report R43599, Unaccompanied Alien Children: An Overview, Figure 1. |

| 45. |

CRS analyzed published CBP total monthly apprehensions data from FY2000 to FY2019 (not presented herein). For a detailed discussion of this annual migration cycle, see, for example, Douglas S. Massey, Rafael Alarcon, Jorge Durand, and Humberto González, Return to Aztlan, University of California Press, 1990. |

| 46. |

Other factors may have also contributed to this decline, and establishing the contribution of each factor requires a rigorous analysis that is beyond the scope of this report. |

| 47. |

For more information, see CRS Report R45489, Recent Migration to the United States from Central America: Frequently Asked Questions. |

| 48. |

Simon Romero and Caitlin Dickerson, "'Desperation of Thousands' Pushes Migrants Into Ever Remote Terrain," New York Times, January 29, 2019; and Alicia Caldwell, "Illegal Migrant Crossings Surge in Remote New Mexico Desert," Wall Street Journal, January 29, 2019. |

| 49. |

For more information, see CRS Report R43599, Unaccompanied Alien Children: An Overview. |

| 50. |

For more information, see CRS Report R45539, Immigration: U.S. Asylum Policy. |

| 51. |

See CRS Report R45915, Immigration Detention: A Legal Overview. |

| 52. |

U.S. Department of Justice, Executive Office for Immigration Review, "Executive Office for Immigration Review: An Agency Guide," fact sheet, December 2017. |

| 53. |

See, for example, Victoria A. Greenfield, Blas Nuñez-Neto, and Ian Mitch et al., Human Smuggling and Associated Revenues: What Do or Can We Know About Routes from Central America to the United States?, Homeland Security Operational Analysis Center operated by the RAND Corporation, 2019. |

| 54. |

Alicia A. Caldwell, "Migrants Find Different Fates at Texas, Arizona Borders," Wall Street Journal, November 11, 2019. |

| 55. |

Executive Office of the President, "Addressing Mass Migration Through the Southern Border of the United States," 83 Federal Register 57661-57664, November 9, 2018. |

| 56. |

The government has not sought a stay of the district court's December 19, 2018, preliminary injunction order. For more information, see American Bar Association, "Update on Changes to Asylum Eligibility, Update as of December 19, 2018," February 11, 2019. |

| 57. |

For more information, see CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10295, The Department of Homeland Security's Reported "Metering" Policy: Legal Issues; and CRS In Focus IF10215, Mexico's Immigration Control Efforts. |

| 58. |

This has included surveillance, engineering, construction, transportation, maintenance, and planning support. For more information, see CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10121, The President's Authority to Use the National Guard or the Armed Forces to Secure the Border. |

| 59. |

Executive Office of the President, "Declaring a National Emergency Concerning the Southern Border of the United States," 84 Federal Register 4949-4950, February 20, 2019. A federal district court initially blocked the Administration from using DOD funding for border barrier construction. That injunction was ultimately stayed by the Supreme Court, thereby permitting the Trump Administration to use the DOD funds as planned. For more information, see CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10310, Supreme Court Stays Injunction That Had Blocked a Portion of the Administration's Border Wall Funding. |

| 60. |

Together, the administration has assembled approximately $6.7 billion through various sources of funding (largely DOD) in funds to construct border barriers on the southwest border. For more information, see CRS Report R45937, Military Funding for Southwest Border Barriers; and "Declaration of an Emergency at the Southern Border" in CRS Report 98-505, National Emergency Powers. |

| 61. |

For more information on the IFR, Asylum Eligibility and Procedural Modifications, see https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/07/16/2019-15246/asylum-eligibility-and-procedural-modifications. |

| 62. |

For more information, including ongoing legal challenges to the IFR, see CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10337, Asylum Bar for Migrants Who Reach the Southern Border through Third Countries: Issues and Ongoing Litigation. |

| 63. |

For more information, see CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10295, The Department of Homeland Security's Reported "Metering" Policy: Legal Issues; and CRS In Focus IF10215, Mexico's Immigration Control Efforts. |

| 64. |

For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10371, U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America: An Overview; and CRS Report R44812, U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America: Policy Issues for Congress. |

| 65. |

A recent analysis from DHS that follows a 2014 cohort of aliens who were either apprehended or found inadmissible along the Southwest border for three years demonstrates that the existing enforcement system is designed primarily to return certain types of migrants (adults with no family members from Mexico, and those who have previously been convicted of a crime) to their home countries. However, among those requesting asylum, it is much more likely that they had neither been repatriated nor had their case resolved by the end of 2017. See U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2014 Southwest Border Encounters: Three Year Cohort Outcomes Analysis, August 2018, p. 2, https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/18_0918_DHS_Cohort_Outcomes_Report.pdf. |

| 66. |

For more information, see, for example, Stephen Castles, "Confronting the Realities of Forced Migration," Migration Policy Institute, May 1, 2004; International Organization for Migration, "IOM Outlook on Migration, Environment and Climate Change," 2014; Holly Reed, "Forced Migration and Undocumented Migration and Development," paper for the United Nations Expert Group Meeting for the Review and Appraisal of the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development and its Contribution to the Follow-up and Review of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, October 31, 2018; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, "International migrants numbered 272 million in 2019, continuing an upward trend in all major world regions," Population Facts, September 2019; and Susan Martin, Sanjula Weerasinghe, and Abbie Taylor, "Crisis Migration," Brown Journal of World Affairs, vol. XX (Fall/Winter 2013), pp. 123-137. |

| 67. |

See, for example, Richard Miles, "A Smaller, Wealthier Mexico Is on the Horizon," Center for Strategic and International Studies, December 11, 2017; Jeffrey S. Passel, D'Vera Cohn, and Ana Gonzalez-Barrera, "Net Migration from Mexico Falls to Zero—and Perhaps Less," Pew Research Center, April 23, 2012; Daniel Chiquiar and Alejandrina Salcedo, "Mexican Migration to the United States: Underlying Economic Factors and Possible Scenarios for Future Flows," Migration Policy Institute, April 2013; CRS Report R43628, Unaccompanied Alien Children: Potential Factors Contributing to Recent Immigration; and Randy Capps, Doris Meissner, and Ariel G. Ruiz Soto et al., From Control to Crisis: Changing Trends and Policies Reshaping U.S.-Mexico Border Enforcement, Migration Policy Institute, August 2019. |

| 68. |

For more information on DHS's existing Alternatives to Detention program, see CRS Report R45804, Immigration: Alternatives to Detention (ATD) Programs. |