Immigration: U.S. Asylum Policy

Asylum is a complex area of immigration law and policy. While much of the recent debate surrounding asylum has focused on efforts by the Trump Administration to address asylum seekers arriving at the U.S. southern border, U.S. asylum policies have long been a subject of discussion.

The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) of 1952, as originally enacted, did not contain any language on asylum. Asylum provisions were added and then revised by a series of subsequent laws. Currently, the INA provides for the granting of asylum to an alien who applies for such relief in accordance with applicable requirements and is determined to be a refugee. The INA defines a refugee, in general, as a person who is outside his or her country of nationality and is unable or unwilling to return to that country because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.

Under current law and regulations, aliens who are in the United States or who arrive in the United States, regardless of immigration status, may apply for asylum (with exceptions). An asylum application is affirmative if an alien who is physically present in the United States (and is not in removal proceedings) submits an application to the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS’s) U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). An asylum application is defensive when the applicant is in standard removal proceedings with the Department of Justice’s (DOJ’s) Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) and requests asylum as a defense against removal. An asylum applicant may receive employment authorization 180 days after the application filing date.

Special asylum provisions apply to aliens who are subject to a streamlined removal process known as expedited removal. To be considered for asylum, these aliens must first be determined by a USCIS asylum officer to have a credible fear of persecution. Under the INA, credible fear of persecution means that “there is a significant possibility, taking into account the credibility of the statements made by the alien in support of the alien’s claim and such other facts as are known to the officer, that the alien could establish eligibility for asylum.” Individuals determined to have a credible fear may apply for asylum during standard removal proceedings.

Asylum may be granted by USCIS or EOIR. There are no numerical limitations on asylum grants. If an alien is granted asylum, his or her spouse and children may also be granted asylum, as dependents. A grant of asylum does not expire, but it may be terminated under certain circumstances. After one year of physical presence in the United States as asylees, an alien and his or her spouse and children may be granted lawful permanent resident status, subject to certain requirements.

The Trump Administration has taken a variety of steps that would limit eligibility for asylum. As of the date of this report, legal challenges to these actions are ongoing. For its part, the 115th Congress considered asylum-related legislation, which generally would have tightened the asylum system. Several bills contained provisions that, among other things, would have amended INA provisions on termination of asylum, credible fear of persecution, frivolous asylum applications, and the definition of a refugee.

Key policy considerations about asylum include the asylum application backlog, the grounds for granting asylum, the credible fear of persecution threshold, frivolous asylum applications, employment authorization, variation in immigration judges’ asylum decisions, and safe third country agreements.

Immigration: U.S. Asylum Policy

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- What is Asylum?

- Overview of Current Asylum Provisions

- Asylum Application Process

- Affirmative Asylum

- USCIS Decisions on Affirmative Asylum Applications

- Defensive Asylum

- EOIR Decisions on Defensive Asylum Applications

- Evolution of U.S. Asylum Policy

- Refugee Act of 1980

- Asylum Process

- Adjustment of Status

- Withholding of Deportation

- 1980 Interim Regulations

- 1990 Final Rule

- Acts of 1990 and 1994

- 1994 Final Rule

- Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act and Implementing Regulations

- Asylum Provisions

- Definition of a Refugee

- Inspection of Arriving Aliens

- Withholding of Removal

- Implementing Regulations

- Convention Against Torture Protection and Implementing Regulations

- Post-1996 Statutory Provisions

- 2018 Interim Final Rule

- DHS Migrant Protection Protocols

- Recent Legislative and Presidential Action

- Legislation in the 115th Congress

- H.R. 4760 and H.R. 6136

- H.R. 391

- Other Bills

- Presidential Action

- Selected Policy Issues

- Asylum Backlog

- Grounds for Asylum

- Credible Fear of Persecution Threshold

- Frivolous or Fraudulent Asylum Claims

- Employment Authorization

- Variation in Immigration Judges' Asylum Decisions

- Safe Third Country Agreements

- Conclusion

Figures

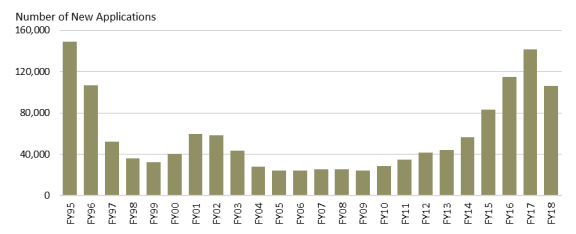

- Figure 1. New Affirmative Asylum Applications Filed, FY1995-FY2018

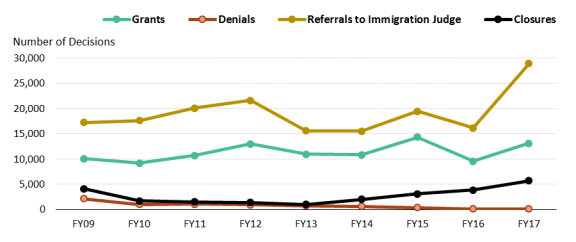

- Figure 2. USCIS Decisions on Affirmative Asylum Applications, FY2009-FY2017

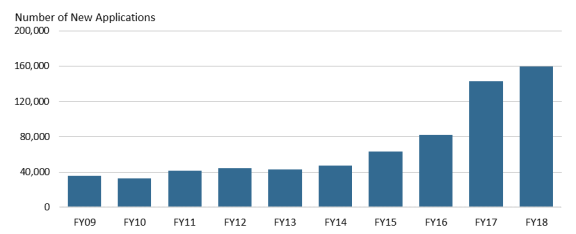

- Figure 3. Defensive Asylum Applications Filed, FY2009 -FY2018

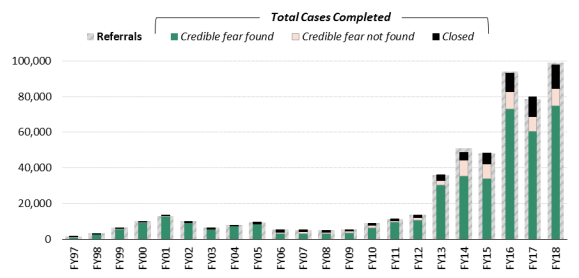

- Figure 4. Credible Fear Referrals and Findings, FY1997-FY2018

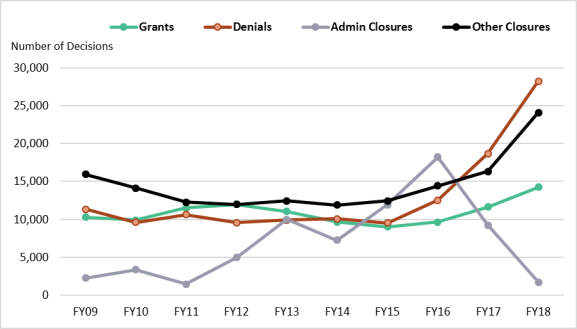

- Figure 5. Immigration Judge Decisions in Defensive Asylum Cases, FY2009-FY2018

Tables

- Table A-1. New Affirmative Asylum Applications Filed, FY1995-FY2018

- Table A-2. Top 10 Nationalities Filing New Affirmative Asylum Applications, FY2007-FY2018

- Table B-1. USCIS Decisions on Affirmative Asylum Applications, FY2009-FY2017

- Table B-2. Credible Fear Cases: Referrals & Completions, FY1997-FY2018

- Table B-3. Outcomes of Completed Credible Fear Cases, FY1997-FY2018

- Table C-1. Defensive Asylum Applications Filed, FY2009-FY2018

- Table D-1. EOIR Decisions in Asylum Cases, FY2009-FY2018

- Table D-2. Immigration Judge Decisions in Asylum Cases with Initial Credible Fear Findings, FY2009-FY2018

Summary

Asylum is a complex area of immigration law and policy. While much of the recent debate surrounding asylum has focused on efforts by the Trump Administration to address asylum seekers arriving at the U.S. southern border, U.S. asylum policies have long been a subject of discussion.

The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) of 1952, as originally enacted, did not contain any language on asylum. Asylum provisions were added and then revised by a series of subsequent laws. Currently, the INA provides for the granting of asylum to an alien who applies for such relief in accordance with applicable requirements and is determined to be a refugee. The INA defines a refugee, in general, as a person who is outside his or her country of nationality and is unable or unwilling to return to that country because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.

Under current law and regulations, aliens who are in the United States or who arrive in the United States, regardless of immigration status, may apply for asylum (with exceptions). An asylum application is affirmative if an alien who is physically present in the United States (and is not in removal proceedings) submits an application to the Department of Homeland Security's (DHS's) U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). An asylum application is defensive when the applicant is in standard removal proceedings with the Department of Justice's (DOJ's) Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) and requests asylum as a defense against removal. An asylum applicant may receive employment authorization 180 days after the application filing date.

Special asylum provisions apply to aliens who are subject to a streamlined removal process known as expedited removal. To be considered for asylum, these aliens must first be determined by a USCIS asylum officer to have a credible fear of persecution. Under the INA, credible fear of persecution means that "there is a significant possibility, taking into account the credibility of the statements made by the alien in support of the alien's claim and such other facts as are known to the officer, that the alien could establish eligibility for asylum." Individuals determined to have a credible fear may apply for asylum during standard removal proceedings.

Asylum may be granted by USCIS or EOIR. There are no numerical limitations on asylum grants. If an alien is granted asylum, his or her spouse and children may also be granted asylum, as dependents. A grant of asylum does not expire, but it may be terminated under certain circumstances. After one year of physical presence in the United States as asylees, an alien and his or her spouse and children may be granted lawful permanent resident status, subject to certain requirements.

The Trump Administration has taken a variety of steps that would limit eligibility for asylum. As of the date of this report, legal challenges to these actions are ongoing. For its part, the 115th Congress considered asylum-related legislation, which generally would have tightened the asylum system. Several bills contained provisions that, among other things, would have amended INA provisions on termination of asylum, credible fear of persecution, frivolous asylum applications, and the definition of a refugee.

Key policy considerations about asylum include the asylum application backlog, the grounds for granting asylum, the credible fear of persecution threshold, frivolous asylum applications, employment authorization, variation in immigration judges' asylum decisions, and safe third country agreements.

Introduction

Illegal aliens have exploited asylum loopholes at an alarming rate. Over the last five years, DHS has seen a 2000 percent increase in aliens claiming credible fear (the first step to asylum), as many know it will give them an opportunity to stay in our country, even if they do not actually have a valid claim to asylum.

—Department of Homeland Security (DHS) press release, December 20, 20181

The increased number of Central Americans petitioning for asylum in the United States is not because more people are "exploiting" the system via "loopholes," but because many have credible claims…. There is no recorded evidence by any U.S. federal agency showing that the increased number of people petitioning for asylum in the United States is due to more people lying about the dangers they face back in their country of origin.

—Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) commentary, March 14, 20182

These statements and the conflicting views about asylum seekers underlying them suggest why the asylum debate has become so heated. Policymakers have faced a perennial challenge to devise a fair and efficient system that approves legitimate asylum claims while deterring and denying illegitimate ones. Changes in U.S. asylum policy and processes over the years can be seen broadly as attempts to strike the appropriate balance between these two goals. Periods marked by increasing levels of asylum-seeking pose particular challenges and may elicit a variety of policy responses. Faced with an influx of Central Americans seeking asylum at the southern U.S. border, the Trump Administration has put forth policies to tighten the asylum system (see, for example, the "2018 Interim Final Rule" and "DHS Migrant Protection Protocols" sections of this report); these policies typically have been met with court challenges. This report explores the landscape of U.S. asylum policy through an analysis of current asylum processes, available data, legislative and regulatory history, recent legislative and presidential proposals, and selected policy questions.

What is Asylum?

In common usage, the word asylum often refers to protection or safety. In the immigration context, however, it has a narrower meaning. The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) of 1952, as amended,3 provides for the granting of asylum to an alien4 who applies for such relief in accordance with applicable requirements and is determined to be a refugee.5 The INA defines a refugee, in general, as a person who is outside his or her country of nationality and is unable or unwilling to return to, or to avail himself or herself of the protection of, that country because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution based on one of five protected grounds: race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. Asylum can be granted by the Department of Homeland Security's (DHS's) U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) or the Department of Justice's (DOJ's) Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), depending on the type of application filed (see "Asylum Application Process").

The INA distinguishes between applicants for refugee status and applicants for asylum by their physical location. Refugee applicants are outside the United States, while applicants for asylum are physically present in the United States or at a land border or port of entry.6 After one year as a refugee or asylee (a person granted asylum), an individual can apply to be become a U.S. lawful permanent resident (LPR).7

Overview of Current Asylum Provisions

With some exceptions, aliens who are in the United States or who arrive in the United States, regardless of immigration status, may apply for asylum. This summary describes the asylum process for an adult applicant.

As discussed in the next section of the report, asylum may be granted by a USCIS asylum officer or an EOIR immigration judge.8 There are no numerical limitations on asylum grants. In order to receive asylum, an alien must establish that he or she meets the INA definition of a refugee, among other requirements. Certain aliens, such as those who are determined to pose a danger to U.S. security, are ineligible for asylum. An asylum applicant who is not otherwise eligible to work in the United States may apply for employment authorization 150 days after filing a completed asylum application and may receive such authorization 180 days after the application filing date.

An alien who has been granted asylum is authorized to work in the United States and may receive approval to travel abroad. A grant of asylum does not expire, but it may be terminated under certain circumstances, such as if an asylee is determined to no longer meet the INA definition of a refugee. After one year of physical presence in the United States as an asylee, an alien may be granted LPR status, subject to certain requirements. There are no numerical limitations on the adjustment of status of asylees to LPR status.

Special asylum provisions apply to certain aliens without proper documentation who are determined to be subject to a streamlined removal process known as expedited removal. To be considered for asylum, these aliens must first be determined by a USCIS asylum officer to have a credible fear of persecution. Those determined to have a credible fear may apply for asylum during standard removal proceedings. (See "Inspection of Arriving Aliens.")

Asylum Application Process

Applications for asylum are either defensive or affirmative. A different set of procedures applies to each type of application.

Affirmative Asylum

An asylum application is affirmative if an alien who is physically present in the United States (and not in removal proceedings) submits an application for asylum to DHS's USCIS. An alien may file an affirmative asylum application regardless of his or her immigration status, subject to applicable restrictions. There is no fee to apply for asylum.9

Figure 1 shows the number of new affirmative asylum applications filed with USCIS since FY1995, the year filings reached their historical high point. The years included in this figure and in the subsequent figures and tables differ due to the availability of data from the relevant agencies. The data displayed in Figure 1 are for applications, not individuals; an application may include a principal applicant and dependents. Figure 1 reflects the impact of various factors. For example, reforms in the mid-1990s, which made the asylum system more restrictive, contributed to the decline in applications in the earlier years shown. A contributing factor to the application increases in the later years depicted in Figure 1 was the influx of unaccompanied alien children from Central America seeking asylum.10 (See Appendix A for underlying data and data on the top 10 nationalities filing affirmative asylum applications.)

The INA prohibits the granting of asylum until the identity of the asylum applicant has been checked against appropriate records and databases to determine if he or she is inadmissible or deportable, or ineligible for asylum.11 As part of the affirmative asylum process, applicants are scheduled for fingerprinting appointments. The fingerprints are used to confirm the applicant's identity and perform background and security checks.

Asylum applicants are interviewed by USCIS asylum officers. In scheduling asylum interviews, the USCIS Asylum Division is currently giving priority to applications that have been pending for 21 days or less. According to USCIS, "Giving priority to recent filings allows USCIS to promptly place such individuals into removal proceedings, which reduces the incentive to file for asylum solely to obtain employment authorization."12

Under DHS regulations, the asylum interview is to be conducted in "a nonadversarial manner." The applicant may bring counsel or a representative to the interview, present witnesses, and submit other evidence. After the interview, the applicant or the applicant's representative can make a statement.13

USCIS Decisions on Affirmative Asylum Applications

An asylum officer's decision on an application is reviewed by a supervisory asylum officer, who may refer the case for further review.14 If an asylum officer ultimately determines that an applicant is eligible for asylum, the applicant receives a letter and form documenting the grant of asylum.15

If the asylum officer determines that an applicant is not eligible for asylum and the applicant has immigrant status, nonimmigrant status, or temporary protected status (TPS),16 the asylum officer denies the application.17 If the asylum officer determines than an applicant is not eligible for asylum and the applicant appears to be inadmissible or deportable under the INA, however, DHS regulations direct the officer to refer the case to an immigration judge for adjudication in removal proceedings.18 In those proceedings, the immigration judge evaluates the asylum claim independently as a defensive application for asylum.

Figure 2 presents data on affirmative asylum applications considered by USCIS since FY2009. It shows four separate outcome categories. Closures are cases administratively closed for reasons such as abandonment or lack of jurisdiction. A closure in one fiscal year in Figure 2 could have been refiled or reopened in a subsequent year. Figure 2 shows that a majority of cases were referred to an immigration judge each year. These referrals included both applicants who were interviewed by USCIS and applicants who were not (e.g., they did not appear for the interview). (See Table B-1 for underlying data and additional detail.19)

Defensive Asylum

An asylum application is defensive when the applicant is in standard removal proceedings in immigration court20 and requests asylum as a defense against removal. Figure 3 provides data on defensive asylum applications filed since FY2009. The data include both cases that originated as defensive cases as well as cases that were first filed as affirmative applications with USCIS, as described in the preceding section. (See Table C-1 for underlying data and additional detail.)

There are different ways that an alien can be placed in standard removal proceedings. An alien who is living in the United States can be charged by DHS with violating immigration law. In such a case, DHS initiates removal proceedings when it serves the alien with a Notice to Appear before an immigration judge.

Another way to be placed in standard removal proceedings relates to the statutory expedited removal and credible fear screening provisions discussed more fully below (see "Inspection of Arriving Aliens"). Under the INA, an individual who is determined by DHS to be inadmissible to the United States because he or she lacks proper documentation or has committed fraud or willful misrepresentation of facts to obtain documentation or another immigration benefit (and thus is subject to expedited removal) and expresses the intent to apply for asylum or a fear of persecution is to be interviewed by an asylum officer to determine if he or she has a credible fear of persecution. Credible fear of persecution means that "there is a significant possibility, taking into account the credibility of the statements made by the alien in support of the alien's claim and such other facts as are known to the officer, that the alien could establish eligibility for asylum."21 If the alien is found to have a credible fear, the asylum officer is to refer the case to an immigration judge for a full hearing on the asylum request during removal proceedings.

Figure 4 provides data on USCIS credible fear findings since FY1997. For each year, it shows the number of credible fear cases referred to and completed by USCIS and the outcomes of the completed cases. Closed cases are cases in which a credible fear determination was not made. (See Table B-2 and Table B-3 for underlying data and additional detail.)

EOIR Decisions on Defensive Asylum Applications

During a removal proceeding, an attorney from DHS's Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) presents the government's case for removing the alien, the alien or their representative may present evidence on the alien's behalf and cross examine witnesses, and an immigration judge from EOIR determines whether the alien should be removed. An immigration judge's removal decision is generally subject to administrative and judicial review.22

Figure 5 presents data on EOIR decisions in defensive asylum cases since FY2009. (See Appendix D for underlying data and data for defensive cases that began with a credible fear claim.23) Figure 5 shows a sharp drop in administrative closures since FY2016. Administrative closing "allows the removal of cases from the immigration judge's calendar in certain circumstances" but "does not result in a final order" in the case;24 cases that are administratively closed can be reopened. Administrative closure has been used, for example, when an alien has a pending application for relief from another agency. In May 2018, Attorney General Jeff Sessions ruled that immigration judges and the BIA do not have general authority to administratively close cases.25

Evolution of U.S. Asylum Policy

The INA, as originally enacted, did not contain refugee or asylum provisions. Language on the conditional entry of refugees was added by the INA Amendments of 1965.26 The 1965 act authorized the conditional entry of aliens, who were to include those who demonstrated to DOJ's Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS)27 that

(i) because of persecution or fear of persecution on account of race, religion, or political opinion they have fled (I) from any Communist or Communist-dominated country or area, or (II) from any country within the general area of the Middle East, and (ii) are unable or unwilling to return to such country or area on account of race, religion, or political opinion, and (iii) are not nationals of the countries or areas in which their application for conditional entry is made.28

In 1968, the United States acceded to the 1967 United Nations Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees (Protocol). The Protocol incorporated the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (Convention), which the United States had not previously been a party to, and expanded the Convention's definition of a refugee.29 The Convention had defined a refugee in terms of events occurring before January 1951. The Protocol eliminated that date restriction. It also provided that the refugee definition would apply without geographic limitation, while allowing for some exceptions.30 With the changes made by the Protocol, a refugee came to be defined as a person who "owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country."

The Protocol retained other elements of the Convention, including the latter's prohibition on refoulement (or forcible return), a fundamental asylum concept. Specifically, the Convention prohibited states from expelling or returning a refugee "to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of his race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion."31

In the 1970s, INS issued regulations that established procedures for applying for asylum in the United States and for adjudicating asylum applications. For example, a 1974 rule provided that an asylum applicant could include his or her spouse and unmarried minor children on the application and that INS could deny or approve an asylum application as a matter of discretion.32

Refugee Act of 1980

Despite the U.S. accession to the 1967 U.N. Protocol, the INA did not include a conforming definition of a refugee or a mandatory nonrefoulement provision until the enactment of the Refugee Act of 1980.33 As noted, the 1965 conditional entry provisions incorporated a refugee definition that was limited by type of government and geography. A 1999 INS report explained a goal of the Refugee Act as being "to establish a politically and geographically neutral adjudication for both asylum status and refugee status, a standard to be applied equally to all applicants regardless of country of origin."34

The definition of a refugee, as added to the INA by the 1980 act, reads, in main part:

(A) any person who is outside any country of such person's nationality ... and who is unable or unwilling to return to, and is unable or unwilling to avail himself or herself of the protection of, that country because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.35

(This first part of the definition of a refugee has not changed since enactment of the Refugee Act.)

Asylum Process

As explained by INS Acting Commissioner Doris Meissner at a 1981 Senate hearing, the primary focus of the Refugee Act of 1980 was the refugee process. According to Meissner's written testimony, "The asylum process was looked upon as a separate and considerably less significant subject."36 In keeping with this secondary status, the asylum provisions added by the 1980 act to the INA (as INA §208) comprised three short paragraphs. The first directed the Attorney General to establish asylum application procedures for aliens physically present in the United States or arriving at a land border or port of entry, regardless of immigration status, and gave the Attorney General discretionary authority to grant asylum to aliens who met the newly added INA definition of a refugee. The second paragraph allowed for the termination of asylum status if the Attorney General determined that the alien no longer met the INA definition of a refugee due to "a change in circumstances" in the alien's home country. The third paragraph provided for the granting of asylum status to the spouse and children37 of an alien granted asylum.38

Adjustment of Status

Separate language in the Refugee Act added a new Section 209 to the INA on refugee and asylee adjustment of status. Adjustment of status is the process of acquiring LPR status in the United States. The asylee provisions granted the Attorney General discretionary authority to adjust the status of an alien who had been physically present in the United States for one year after being granted asylum and met other requirements, subject to an annual numerical limit of 5,000.39

Withholding of Deportation

The Refugee Act amended an INA provision on withholding of deportation, making it consistent with the nonrefoulement language in the Convention. The INA provision in effect prior to the enactment of the Refugee Act "authorized" the Attorney General to withhold the deportation of an alien in the United States (other than an alien involved in Nazi-related activity) to "any country in which in his opinion the alien would be subject to persecution on account of race, religion or political opinion." The Refugee Act revised this language to prohibit the Attorney General from deporting or returning any alien to a country where the Attorney General determines the alien's life or freedom would be threatened because of the alien's race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. It also added exclusions beyond the one for participation in Nazi-related activity.40 Specifically, the new provision made an alien ineligible for withholding if the alien had participated in the persecution of another person based on race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion; the alien had been convicted of a "particularly serious crime" and thus was a danger to the United States; there existed "serious reasons for considering that the alien had committed a serious nonpolitical crime outside the United States," or there existed "reasonable grounds" for considering the alien a danger to national security. (For subsequent changes to this provision, see "Withholding of Removal.")

1980 Interim Regulations

INS published interim regulations in June 1980 to implement the Refugee Act's provisions on refugee and asylum procedures.41 The asylum regulations included the following:

- INS district directors had jurisdiction over all requests for asylum except for those made by aliens in exclusion or deportation proceedings.42

- An alien whose application for asylum was denied by the district director could renew the asylum request in exclusion or deportation proceedings.

- The applicant had the burden of proof to establish eligibility for asylum.

- The asylum applicant would be examined in person by an immigration officer or an immigration judge.43

- The district director (or the immigration judge) would request an advisory opinion on the asylum application from the Department of State's (DOS's) Bureau of Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs (BHRHA).

- The district director could grant work authorization to an asylum applicant who filed a "non-frivolous" application.

- The district director's decision on an asylum application was discretionary.

- The district director would deny an asylum application for various reasons, including that the alien had been firmly resettled in another country; the alien had participated in the persecution of another person based on race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion; the alien had been convicted of a "particularly serious crime" and thus was a danger to the United States; there existed "serious reasons for considering that the alien had committed a serious non-political crime outside the United States;" or there existed "reasonable grounds" for considering the alien a danger to national security.

- An initial grant of asylum was for one year and could be extended in one-year increments.

- Asylum status could be terminated for various reasons, including changed conditions in the asylee's home country.

1990 Final Rule

There was much discussion and debate about asylum in the 1980s, as related legislation and regulations were proposed, court cases were litigated, and the number of applications increased. In addition, in a 1983 internal DOJ reorganization, EOIR was established as a separate DOJ agency to administer the U.S. immigration court system. It combined the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA)44 with the INS immigration judge function. With the creation of EOIR, the immigration courts became independent of INS.

It was not until July 1990 that INS published a final rule to revise the 1980 interim regulations on asylum procedures.45 According to the supplementary information to the 1990 rule, the asylum policy established by the rule reflected two core principles: "A fundamental belief that the granting of asylum is inherently a humanitarian act distinct from the normal operation and administration of the immigration process; and a recognition of the essential need for an orderly and fair system for the adjudication of asylum claims."46

The 1990 final rule created the position of asylum officer within INS to adjudicate asylum applications. As described in the supplementary information to a predecessor 1988 proposed rule, asylum officers were intended to be "a specially trained corps" that would develop expertise over time, with the expected result of greater uniformity in asylum adjudications.47 Under the 1990 rule, asylum applications filed with the district director were to be forwarded to the asylum officer with jurisdiction in the district.

Under the 1990 rule, comments on asylum applications by DOS—a standard part of the adjudication process under the 1980 interim regulations—became optional.48 (In an earlier, related development, DOS announced that as of November 1987 it would no longer be able to provide an advisory opinion on every asylum application due to budget constraints and would focus on those cases where it thought it could provide input not available from other sources.49)

The 1990 rule distinguished between asylum claims based on actual past persecution and on a well-founded fear of future persecution. To establish a well-founded fear of future persecution, the rule required, in part, that an applicant establish that he or she fears persecution in his or her country based on one of the five protected grounds and that "there is a reasonable possibility of actually suffering such persecution" upon return. The rule further detailed the "burden of proof" requirements for asylum applicants. It provided that the applicant's own testimony alone may be sufficient to prove that he or she meets the definition of a refugee. It also stated that an applicant could show a well-founded fear of persecution on one of the protected grounds without proving that he or she would be persecuted individually, if the applicant could establish "that there is a pattern or practice" of persecution of similarly situated individuals in his or her home country and that he or she is part of such a group.50

The 1990 rule provided that a grant of asylum to a principal applicant would be for an indefinite period. It also provided that the grant of asylum to a principal applicant's spouse and children would be indefinite, unless the principal's asylum status was revoked.

Under the 1990 rule, an application for asylum was also to be considered an application for withholding of deportation; in cases of asylum denials, the asylum officer was required to decide whether the applicant was entitled to withholding of deportation. A 1987 proposed rule would have made asylum officers' decisions on asylum and withholding of deportation applications binding on immigration judges.51 That change was not retained in the 1990 final rule, however, which preserved immigration judges' role in adjudicating asylum and withholding of deportation claims in exclusion or deportation proceedings. Regarding eligibility for withholding of deportation, the 1990 rule stated, in part, "The applicant's life or freedom shall be found to be threatened if it is more likely than not that he would be persecuted on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion."52

The 1990 rule directed the asylum officer to grant an undetained asylum applicant employment authorization for up to one year if the officer determined that the application was not frivolous; frivolous was defined as "manifestly unfounded or abusive."53 The employment authorization could be renewed in increments of up to one year. The asylum officer had to provide an applicant with a written decision on an asylum or withholding of deportation application, and had to provide an explanation in the case of a denial. The 1990 rule also granted specified officials in INS and DOJ the authority to review the decisions of asylum officers but did not grant applicants any right to appeal to these officials.

Acts of 1990 and 1994

The Immigration Act of 199054 and the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 199455 made several changes to the asylum-related provisions in the INA. The 1990 act amended INA §209 to increase the annual numerical limitation on asylee adjustment of status from 5,000 to 10,000.56 It also added new language to INA §208, making an alien who had been convicted of a crime categorized as an aggravated felony under the INA ineligible for asylum.57 The 1994 act further amended INA §208 to state that an asylum applicant was not entitled to employment authorization except as provided at the discretion of the Attorney General by regulation.58

1994 Final Rule

In March 1994, INS published a proposed rule to streamline its asylum procedures that included a number of controversial provisions. The agency characterized the problem the proposal sought to address as follows: "The existing system for adjudicating asylum claims cannot keep pace with incoming applications and does not permit the expeditious removal from the United States of those persons who[se] claims fail."59

The 1994 final rule, published in December 1994, made fundamental changes to the asylum adjudication process.60 Under the rule, INS asylum officers were no longer to deny asylum applications filed by aliens who appeared to be excludable or deportable,61 or to consider applications for withholding of deportation from such applicants, with limited exceptions. Instead, officers were to either grant such applicants asylum or immediately refer their claims to immigration judges, where the claims would be considered as part of exclusion or deportation proceedings. Asylum officers were to continue to issue approvals and denials in cases of asylum applications filed by aliens with a legal immigration status.

The 1994 rule also made changes to the employment authorization process for asylum applicants that were intended to "discourage applicants from filing meritless claims solely as a means to obtain employment authorization."62 Under the rule, an alien had to wait 150 days after his or her complete asylum application had been received to apply for employment authorization.63 INS then had 30 days to adjudicate that employment authorization application. (These 150-day and 30-day time frames remain in regulation.64) According to the supplementary information accompanying the rule, the goal was to make a decision on an asylum application before the end of 150 days: "The Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) and the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) would strive to complete the adjudication of asylum applications, through the decision of an immigration judge, within this 150-day period."65

Some of the provisions in the proposed rule were not adopted in the final rule. These included proposals to make asylum interviews discretionary and to charge fees for asylum applications and initial applications for employment authorization.66

Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act and Implementing Regulations

The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) of 199667 significantly amended the INA's asylum provisions and made a number of other changes to the INA relevant to asylum policy. Many of the IIRIRA changes remain in effect.

One set of changes, which had broad implications for the immigration system generally, concerned the INA grounds of exclusion. Applicable to aliens outside the United States, these provisions enumerated classes of aliens who were ineligible for visas and were to be excluded from admission. IIRIRA amended these provisions and replaced the concept of an excludable alien with that of an inadmissible alien—the latter being a person who, whether outside or inside the United States, has not been lawfully admitted to the country. In general, with the enactment of IIRIRA, an alien became ineligible for a visa or admission if he or she was described in the reconfigured grounds of inadmissibility.68

Asylum Provisions

IIRIRA added restrictions to the general policy set forth in the 1980 Refugee Act and incorporated into the INA that an alien who is present in the United States or who arrives in the United States, regardless of immigration status, can apply for asylum. In general, under the IIRIRA amendments, which remain in effect, an alien is not eligible to apply for asylum unless the alien can show that he or she filed the application within one year of arriving in the United States. An alien is also generally ineligible to apply if he or she has previously had an asylum application denied. There is an exception to both restrictions if an alien can show "changed circumstances which materially affect the applicant's eligibility for asylum," and an additional exception to the time limit requirement if the alien can show "extraordinary circumstances" related to the filing delay.69 IIRIRA also made an alien ineligible to apply for asylum if the Attorney General determined that the alien could be removed, pursuant to a bilateral or multilateral agreement, to a safe third country where the alien would be considered for asylum or equivalent temporary protection (see "Safe Third Country Agreements").70

IIRIRA amended the INA to authorize, but not require, the Attorney General to impose fees on asylum applications and related applications for employment authorization.71 Among other new asylum provisions it added to the INA were a requirement to check the identity of applicants against "all appropriate records or databases maintained by the Attorney General and by the Secretary of State" and a permanent bar to receiving any immigration benefits for aliens who knowingly file frivolous asylum applications after being notified of the consequences for doing so.72 IIRIRA also put asylum processing-related time frames in statute, including a requirement that "in the absence of exceptional circumstances," administrative adjudication of an asylum application be completed within 180 days after the filing date.73 All these provisions are still in statute.

IIRIRA modified and codified some existing and prior asylum regulations. It amended an existing INA provision on employment authorization by adding language prohibiting an asylum applicant who is not otherwise eligible for employment authorization from being granted such authorization earlier than 180 days after filing the asylum application. It further amended the INA asylum provisions to add grounds for denying asylum. Similar to the mandatory denial language in the 1980 interim regulations, these grounds included an applicant's conviction for a "particularly serious crime," "serious reasons for believing the alien has committed a serious nonpolitical crime outside the United States," "reasonable grounds" for considering the alien a danger to national security, and the applicant's firm resettlement in another country prior to arrival in the United States.74 IIRIRA also added, as a new asylum denial ground, being inadmissible to the United States on certain terrorist-related grounds.75 In addition, IIRIRA provided that the Attorney General could establish additional ineligibilities for asylum by regulation that were consistent with the INA asylum provisions.76 These IIRIRA amendments remain a part of the INA, although the provision on terrorist-related grounds of inadmissibility has been revised.77

IIRIRA amended the INA language on termination of asylum to state that the granting of asylum "does not convey a right to remain permanently in the United States." It also added new termination grounds to the existing ground of no longer meeting the INA definition of a refugee. IIRIRA provided that asylum could be terminated if the Attorney General determined that the asylee met one of the grounds for denying asylum noted in the preceding paragraph. Among IIRIRA's other new grounds for terminating asylum was a determination by the Attorney General, analogous to the "safe third country" determination described above, that the alien could be removed, pursuant to a bilateral or multilateral agreement, to a safe third country where the alien would be eligible for asylum or equivalent temporary protection.78 The IIRIRA asylum termination provisions remain part of the INA.79

Definition of a Refugee

IIRIRA amended the INA definition of a refugee to cover individuals subject to "coercive population control." It provided that for purposes of meeting the definition of a refugee, an individual who had been forced to have an abortion or undergo sterilization or had been persecuted for resistance to a coercive population control program would be considered to have been persecuted on the basis of political opinion. Similarly, an individual with a well-founded fear that he or she would be forced to undergo a procedure or would be persecuted for resistance to a coercive population control program would be considered to have a well-founded fear of persecution on the basis of political opinion.80 This language remains part of the INA definition of a refugee.

Inspection of Arriving Aliens

IIRIRA amended the INA provisions on the inspection of aliens by immigration officers to establish a new immigration enforcement mechanism known as expedited removal. In general, under expedited removal an alien who is determined by an immigration officer to be inadmissible to the United States because the alien lacks proper documentation or has committed fraud or willful misrepresentation of facts to obtain documentation or another immigration benefit may be removed from the United States without any further hearings or review, unless the alien indicates either an intention to apply for asylum or a fear of persecution.81

Under the INA, as amended by IIRIRA, this expedited removal procedure was to be applied to all arriving aliens, a term that includes aliens arriving at a U.S. port of entry.82 (An exception for Cuban citizens arriving at U.S. ports of entry by aircraft is no longer in effect.83) It also could be applied to any (or all) aliens in the United States, as designated by the Attorney General at his or her discretion, if an alien has not been admitted or paroled into the United States and "has not affirmatively shown, to the satisfaction of an immigration officer, that the alien has been physically present in the United States continuously for the 2-year period immediately prior to the date of the determination of inadmissibility."84 Using this statutory authority, the application of expedited removal has been expanded to classes of aliens beyond arriving aliens (see "Implementing Regulations").

Under the IIRIRA amendments, an alien who is subject to expedited removal and expresses the intent to apply for asylum or a fear of persecution is to be interviewed by an asylum officer to determine if the alien has a credible fear of persecution.85 (Special procedures apply to aliens arriving in the United States at a U.S.-Canada land port of entry in accordance with a U.S.-Canada agreement; see "Safe Third Country Agreements.") Under the INA, credible fear of persecution means that "there is a significant possibility, taking into account the credibility of the statements made by the alien in support of the alien's claim and such other facts as are known to the officer, that the alien could establish eligibility for asylum."86 If an alien is found to have a credible fear, the asylum officer is to refer the case to an immigration judge for full consideration of the asylum request during standard removal proceedings. If an alien is found not to have a credible fear, the alien may request that an immigration judge review the negative finding. To ultimately receive asylum, however, an alien must meet the higher standard of showing past persecution or a well-founded fear of future persecution.

Withholding of Removal

As part of a larger set of changes to the INA replacing the concept of deportation with removal, IIRIRA added a withholding of removal provision (INA §241(b)(3)) to replace the existing INA withholding of deportation provision.87 The new withholding of removal provision stated, and continues to state, in main part, that "the Attorney General may not remove an alien to a country if the Attorney General decides that the alien's life or freedom would be threatened in that country because of the alien's race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion."88 The IIRIRA provision retained language on ineligibility for withholding that had been enacted in 1980. It also included language on treatment of aggravated felonies for purposes of ineligibility for withholding of removal.89 The IIRIRA amendments on ineligibility for withholding of removal remain in current law.90

Some of the same ineligibility grounds apply to applicants for withholding of removal and applicants for asylum. As noted, however, asylum is also subject to a second set of restrictions, under which certain individuals are ineligible to apply for this form of relief. These restrictions include the requirement to apply for asylum within one year after arrival in the United States. Withholding of removal is not subject to an analogous set of restrictions. Another difference between withholding of removal and asylum concerns adjustment to LPR status. The INA provides for the adjustment of status of aliens granted asylum but not those granted withholding of removal (for further comparison of withholding of removal and asylum, see "Implementing Regulations," below).

Implementing Regulations

In March 1997, DOJ issued an interim rule, effective April 1, 1997, to amend existing regulations to implement the IIRIRA provisions on asylum, withholding of removal, expedited removal, and other immigration procedures.91 In December 2000, DOJ published a final rule on asylum procedures, which addressed jurisdiction, asylum application procedures, and withholding of removal, among other issues.92

The December 2000 rule included language on eligibility for asylum and eligibility for withholding of removal under INA §241(b)(3). Regarding eligibility for asylum based on a well-founded fear of future persecution, the 2000 regulations stated, in part, "An applicant has a well-founded fear of persecution if: (A) The applicant has a fear of persecution in his or her country of nationality … on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion; (B) There is a reasonable possibility of suffering such persecution if he or she were to return to that country."93 This language was similar to that in the 1990 rule. Unlike the earlier rule, however, the 2000 regulations also provided that an applicant would not be considered to have a well-founded fear of persecution if he or she could relocate within his or her home country "if under all the circumstances it would be reasonable to expect the applicant to do so."94

Regarding eligibility for withholding of removal under INA §241(b)(3) based on a future threat to one's life or freedom, the 2000 regulations, like the earlier 1990 regulations on withholding of deportation, stated that an applicant could demonstrate a future threat "if he or she can establish that it is more likely than not that he or she would be persecuted on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion upon removal to that country."95 As with the regulations on asylum eligibility, the 2000 regulations on eligibility for withholding of removal provided that an applicant could not demonstrate a threat to life or freedom upon a finding that the applicant could avoid the threat by relocating within his or her home country if it were reasonable to expect him or her to do so.

The December 2000 regulations on eligibility for asylum and withholding of removal under INA §241(b)(3) remain in effect. Comparing the above-cited standards for providing these two forms of relief in cases involving claims of future persecution, the threshold for granting withholding of removal (more likely than not) is higher than that for granting asylum (reasonable possibility).

Regarding expedited removal, DOJ stated in the supplementary information to the March 1997 interim rule that for the time being, it would only apply the expedited removal provisions to arriving aliens (i.e., aliens arriving at ports of entry and certain others). At the same time, it reserved "the right to apply the expedited removal procedures to additional classes of aliens within the limits set by the statute, if, in the [INS] Commissioner's discretion, such action is operationally warranted."96

Beginning in 2002, DOJ and then DHS, which assumed primary responsibility for immigration under the Homeland Security Act,97 acted to apply the expedited removal procedures to additional classes of aliens. In November 2002, DOJ extended expedited removal to aliens arriving by sea who are not admitted or paroled and who have not been continuously present in the United States for the prior two years.98 In August 2004, DHS authorized the placing in expedited removal proceedings of aliens who are present in the United States without having been admitted or paroled, and are found inadmissible due to lack of proper documentation or to commission of fraud or willful misrepresentation to obtain documentation or another immigration benefit, in certain circumstances. These circumstances were that the aliens "are encountered by an immigration officer within 100 air miles of the U.S. international land border" and "have not established to the satisfaction of an immigration officer that they have been physically present in the United States continuously for the fourteen-day (14-day) period immediately prior to the date of encounter."99

Convention Against Torture Protection and Implementing Regulations

Separate from asylum and withholding of removal under the INA, protection from removal is available to aliens in the United States who are more likely than not to be tortured in the country of removal, in accordance with the United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment100 (Convention Against Torture, or CAT), which entered into force for the United States in November 1994. Under Article 3 of the CAT, "No State Party shall expel, return ("refouler") or extradite a person to another State where there are substantial grounds for believing that he would be in danger of being subjected to torture." Under current DHS and DOJ regulations, torture is defined, in part, as "any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person … when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity."101 In February 1999, DOJ published an interim rule establishing procedures to implement U.S. obligations under Article 3 of the CAT in the removal process.102 These regulations have since been revised.

DHS regulations set forth procedures for handling cases in which an alien subject to expedited removal expresses a fear of torture. In a process analogous to that for aliens subject to expedited removal who express a fear of persecution, DHS regulations provide that such an alien is to be interviewed by an asylum officer to determine if he or she has a credible fear of torture.103 To establish a credible fear of torture, an alien must show that "there is a significant possibility that he or she is eligible for" protection under the CAT.104 Eligibility for CAT protection, unlike for asylum, does not require the showing of a nexus between the torture claim and a protected ground (such as race). If the asylum officer makes an affirmative credible fear finding, the officer is to refer the case to an immigration judge for full consideration of the CAT application during standard removal proceedings. If the officer makes a negative finding, the alien may request a review of that determination by an immigration judge.105 If during removal proceedings the immigration judge determines that "the alien is more likely than not to be tortured in the country of removal," the alien is entitled to CAT protection.106 That protection is to be granted in the form of either withholding of removal or deferral of removal depending on the circumstances of the case.107

The February 1999 CAT rule also established another screening process—for reasonable fear of persecution or torture. Modeled on but separate from the credible fear of persecution or torture screening processes, reasonable fear screening applies to certain aliens who are not eligible for asylum (these are aliens ordered removed under INA §238(b) for the commission of certain criminal offenses or aliens whose deportation, exclusion, or removal is reinstated under INA §241(a)(5)). Under current DHS and DOJ regulations, if an alien in this category expresses a fear of returning to the country of removal, USCIS is to make a reasonable fear determination, subject to review by an immigration judge.108 To establish a reasonable fear of persecution, an alien must establish "a reasonable possibility that he or she would be persecuted on account of his or her race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinion"; this is the same standard used to establish eligibility for asylum. To establish a reasonable fear of torture, an alien must establish "a reasonable possibility that he or she would be tortured in the country of removal."109

If the alien receives a positive reasonable fear finding, the case is referred to an immigration judge to determine whether the alien is eligible for withholding of removal under INA §241(b)(3) or withholding of removal or deferral of removal under the CAT.110 DHS and DOJ regulations further state, however, that the granting of such withholding of removal or deferral of removal would not prevent the United States from removing the alien to a third country.111

Post-1996 Statutory Provisions

While the IIRIRA amendments to the INA asylum provisions remain largely in place, subsequent laws have made further changes to the INA provisions. For example, the Real ID Act of 2005112 amended the INA language on the conditions for granting asylum to add "burden of proof" provisions, which had previously been in regulations. These burden of proof provisions remain in law. They require an asylum applicant to show that "race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion was or will be at least one central reason for persecuting the applicant" to meet the definition of a refugee.113 The provisions further set forth standards for making determinations about an applicant's credibility and about the need for corroborating evidence to sustain an applicant's burden of proof.114 In addition, among its other asylum-related provisions, the Real ID Act eliminated the annual caps on asylee adjustment of status.115 The 2008 William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA) added language to the INA asylum provisions that addressed asylum applications by unaccompanied alien children in the United States. This new language made certain statutory restrictions on applying for asylum inapplicable to these children and provided that a USCIS asylum officer would have initial jurisdiction over any asylum application filed by an unaccompanied child, even if the child was in removal proceedings.116

2018 Interim Final Rule

On November 9, 2018, DHS and DOJ jointly issued an interim final rule to govern "asylum claims in the context of aliens who are subject to, but contravene, a suspension or limitation on entry into the United States through the southern border with Mexico that is imposed by a presidential proclamation or other presidential order."117 That same day, President Donald Trump issued a proclamation to suspend immediately the entry into the United States of aliens who cross the Southwest border between ports of entry (see "Presidential Action"). According to the supplementary information accompanying the interim rule, the rule would serve to "channel inadmissible aliens to ports of entry, where such aliens could seek to enter and would be processed in an orderly and controlled manner."118

The interim rule, which is not in effect due to legal challenges, would bar an alien who enters the United States in contravention of the proclamation from eligibility for asylum. Under the rule, an asylum officer would make a negative credible fear of persecution determination in the case of such an alien. As explained in the supplementary information to the rule, however, aliens who enter the United States at the Southwest border without inspection would continue to be eligible for consideration for forms of protection from removal other than asylum—namely, withholding of removal under INA §241(b)(3) and protections under the CAT. The interim final rule addresses eligibility for asylum and screening procedures for aliens who enter the United States in contravention of the proclamation. Regarding claims for withholding of removal under the INA or withholding or deferral of removal under the CAT, the rule establishes that such claims would be assessed under the reasonable fear standard (see "Convention Against Torture Protection and Implementing Regulations"). The supplementary information includes the following summary of the two-stage screening protocol the rule would institute:

Aliens determined to be ineligible for asylum by virtue of contravening a proclamation, however, would still be screened, but in a manner that reflects that their only viable claims would be for statutory withholding or CAT protection…. After determining the alien's ineligibility for asylum under the credible-fear standard, the asylum officer would apply the long-established reasonable-fear standard to assess whether further proceedings on a possible statutory withholding or CAT protection claim are warranted.119

This rule is being challenged in federal court. On December 19, 2018, a federal district court judge in California granted a nationwide preliminary injunction against it.120

DHS Migrant Protection Protocols

On December 20, 2018, DHS announced the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), under which "individuals arriving in or entering the United States from Mexico—illegally or without proper documentation—may be returned to Mexico for the duration of their immigration proceedings."121 The U.S. government notified the Mexican government about the MPP that same day. The MPP is separate and distinct from a safe third country agreement (see "Safe Third Country Agreements").

The DHS press release announcing the Migrant Protection Protocols characterized them as "historic measures" to address the "illegal immigration crisis." In the words of the press release:

Aliens trying to game the system to get into our country illegally will no longer be able to disappear into the United States, where many skip their court dates. Instead, they will wait for an immigration court decision while they are in Mexico. 'Catch and release' will be replaced with 'catch and return.' In doing so, we will reduce illegal migration by removing one of the key incentives that encourages people from taking the dangerous journey to the United States in the first place. This will also allow us to focus more attention on those who are actually fleeing persecution.122

According to DHS, the U.S. government will invoke INA §235(b)(2)(C),123 which permits the return of certain aliens arriving in the United States on land from a foreign contiguous territory to that foreign territory pending standard removal proceedings. An alien potentially subject to this return provision under the INA is an applicant for admission who "is not clearly and beyond a doubt entitled to be admitted" and thus is "detained for a [standard removal] proceeding."124 INA §235(b)(2)(C) is explicitly inapplicable to aliens who are determined to be subject to expedited removal.125

On January 28, 2019, USCIS and DHS's Customs and Border Protection (CBP) issued memoranda on MPP implementation.126 The CBP memorandum announced that the agency would begin implementing the MPP that day. According to the memorandum, "MPP implementation will begin at the San Ysidro port of entry [in California], and it is anticipated that it will be expanded in the near future." Also on January 28, 2019, CBP issued "MPP Guiding Principles," which included the following: "To implement the MPP, aliens arriving from Mexico who are amenable to the process … and who in an exercise of discretion the officer determines should be subject to the MPP process, will be issued [a] Notice to Appear (NTA) and placed into Section 240 removal proceedings. They will then be transferred to await proceedings in Mexico." Among the aliens identified as "not amenable to MPP" in the CBP guiding principles document are unaccompanied alien children, citizens or nationals of Mexico, aliens processed for expedited removal, and aliens who are more likely than not to face persecution or torture in Mexico.127 The MPP is in effect as of the date of this report, but it remains unclear how DHS is making decisions about which aliens to process under the protocols. The MPP is being challenged in federal court.128

Recent Legislative and Presidential Action

Legislation in the 115th Congress

Asylum-related legislation was considered in the 115th Congress. Two immigration bills that were the subjects of unsuccessful House floor votes in June 2018—the Securing America's Future Act of 2018 (H.R. 4760) and the Border Security and Immigration Reform Act of 2018 (H.R. 6136)—contained similar provisions on asylum. A third asylum-related House bill (the Asylum Reform and Border Protection Act of 2017 (H.R. 391)) that included some of the same provisions as the above measures was ordered to be reported by the House Judiciary Committee. In addition, the House and the Senate acted on several other measures containing more limited language on asylum.

H.R. 4760 and H.R. 6136

H.R. 4760 and H.R. 6136, as considered on the House floor, included various provisions related to asylum. Both bills would have amended the INA "safe third country" asylum provision, under which an alien is ineligible to apply for asylum if it is determined that he or she can be removed to a safe country "pursuant to a bilateral or multilateral agreement" (see "Safe Third Country Agreements"). H.R. 4760 and H.R. 6136 would have eliminated the "pursuant to a bilateral or multilateral agreement" language.

Both bills would have added a new provision to the INA stating that an alien's asylum status would be terminated if the alien returned to his or her home country (from which the alien sought refuge in the United States) absent changed country conditions. Both bills would have given DHS discretionary authority to waive this provision in individual cases. H.R. 4760 also included an exception to this provision for certain Cubans.

Both bills would have amended the INA provisions on frivolous asylum applications (see "Frivolous or Fraudulent Asylum Claims"). Current INA provisions make an alien permanently ineligible for immigration benefits if he or she knowingly files a frivolous asylum application after receiving notice of the consequences for doing so. The bills would have changed the notification process. They would have required that a written notice appear on the asylum application advising the applicant of the consequences of filing a frivolous application. The bills would also have added language to the INA explaining that an application is frivolous if "it is so insufficient in substance that it is clear that the applicant knowingly filed the application solely or in part to delay removal from the United States, to seek employment authorization as an applicant for asylum" or "any of the material elements are knowingly fabricated."

H.R. 4760 and H.R. 6136 also would have changed the INA definition of credible fear of persecution, which an alien in expedited removal has to show to be able to pursue an asylum claim. The bills would have added a new requirement to the definition—that "it is more probable than not that the statements made by, and on behalf of, the alien in support of the alien's claim are true." The bills would also have required audio or audio/visual recording of expedited removal and credible fear interviews.

H.R. 391

H.R. 391, as ordered to be reported by the House Judiciary Committee, would have amended the INA provisions on safe third country removals, termination of asylum upon return to the home country, frivolous asylum applications, and credible fear similarly to H.R. 4760 and H.R. 6136. In addition, this bill would have made a number of other changes to the asylum-related language in the INA.129 Among its asylum-related provisions, H.R. 391 would have clarified the INA definition of a refugee (which asylum applicants also have to satisfy), specifically the "membership in a particular social group" ground. It would have defined particular social group, which is not currently defined in statute, to mean a group that is "defined with particularity," is "socially distinct," and has members who share "a common immutable characteristic."

H.R. 391 would have explicitly provided that the "membership in a particular social group" ground would cover individuals who fail or refuse "to comply with any law or regulation that prevents the exercise of the individual right of that person to direct the upbringing and education of a child of that person (including any law or regulation preventing homeschooling)." At the same time, the bill sought to prohibit the application of this ground to asylum cases involving criminal gang membership or activity.

H.R. 391 also included language related to the INA asylum provisions that enumerate certain determinations about an alien that preclude the granting of asylum. One of these determinations is that the alien was "firmly resettled in another country" before coming to the United States and requesting asylum. H.R. 391 would have considered the "firmly resettled" criterion to be satisfied "by evidence that the alien can live in such country (in any legal status) without fear of persecution."

Other Bills

Other bills that saw action in the 115th Congress included more limited language on asylum. For example, the Criminal Alien Gang Member Removal Act (H.R. 3697), as passed by the House, would have added a new item to the INA list of determinations that preclude the granting of asylum. It would have made an alien ineligible for asylum if he or she was inadmissible or deportable based on new INA criminal gang membership or criminal gang-related activity grounds that the bill would have established. Under H.R. 3697, such an alien would also have been exempt from the INA restriction on removing an alien to a country where his or her life or freedom would be threatened based on race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.

Asylum-related provisions similar to those in H.R. 3697 were included in two other measures—the Michael Davis, Jr. and Danny Oliver in Honor of State and Local Law Enforcement Act (H.R. 2431), as ordered to be reported by the House Judiciary Committee, and the SECURE and SUCCEED Act (S.Amdt. 1959 to H.R. 2579), which failed on a Senate floor vote in February 2018. In addition, these two measures would have made further changes to the INA's asylum-related provisions. They would have made aliens ineligible for asylum if they were inadmissible on a broader array of terrorist-related grounds and would have exempted aliens who were inadmissible on this larger set of terrorist grounds from the general INA restriction on removing an alien to a country where his or her life or freedom would be threatened.

H.R. 2431 and S.Amdt. 1959 would also have amended the INA provisions on asylee adjustment of status to LPR status. Current INA provisions generally require that applicants for adjustment be admissible to the United States as immigrants, but they grant the Secretary of Homeland Security or the Attorney General broad authority to waive applicable inadmissibility provisions for humanitarian purposes. While there were significant differences among the asylee adjustment of status amendments in S.Amdt. 1959 and H.R. 2431, both measures would have limited existing DHS/DOJ inadmissibility waiver authority and added new deportability-related requirements to the INA asylee adjustment of status provisions.

Presidential Action

Citing constitutional and statutory authority, President Trump issued a presidential proclamation on November 9, 2018, to immediately suspend the entry into the United States of aliens who cross the Southwest border between ports of entry.130 The proclamation indicates that its entry suspension provisions will expire 90 days after its issuance date or on the date that the United States and Mexico reach a bilateral safe country agreement, whichever is earlier. Also on November 9, 2018, DHS and DOJ jointly issued an interim final rule to bar an alien who enters the United States in contravention of the proclamation from eligibility for asylum. The proclamation and the rule are being challenged in federal court (see "2018 Interim Final Rule").131 On February 7, 2019, President Trump renewed the proclamation with the issuance of a new proclamation with the same name.132

Selected Policy Issues

Asylum is a complex area of immigration law and policy. Much of the recent debate surrounding it has focused on efforts by the Trump Administration to tighten the asylum system. Several key policy considerations about asylum are highlighted below. Some, such as the grounds for granting asylum, have been long-standing issues for policymakers, while others, such as safe third country agreements, have been garnering attention more recently.

Asylum Backlog

There has been much discussion about an increasing backlog of asylum applications. The term asylum backlog may suggest that there is a single queue of pending asylum cases. In fact, as discussed above, USCIS and EOIR separately adjudicate affirmative asylum cases and defensive asylum cases, respectively.133 (Backlog as used in this report is synonymous with pending caseload.)

The numbers of pending USCIS affirmative asylum applications and EOIR defensive asylum cases have varied over the years, impacted by factors including international developments, changes to U.S. immigration laws, and agency resources. In the case of affirmative applications, there have been significant fluctuations in the size of the backlog over the history of the asylum program. Since FY2009, however, backlogs of both USCIS affirmative asylum applications and EOIR cases have increased annually. At the end of FY2009, there were about 6,000 pending affirmative asylum applications at USCIS134; that number stood at about 320,000 at the end of FY2018.135

During this same period, the number of pending cases before EOIR increased from about 224,000 at the end of FY2009 to about 786,000 at the end of FY2018.136 Not all the EOIR cases necessarily involve an asylum claim, however. According to EOIR, as of June 18, 2018, it had about 720,000 pending cases, and some 325,000 of those (about 45%) included asylum applications.137

A variety of arguments are made for prioritizing the reduction of the asylum backlog. These include the need to preserve the integrity of the asylum process and to provide protection in a timely manner to legitimate asylum seekers. More controversial arguments for addressing the backlog center on the perceived need to eliminate an incentive for unauthorized aliens without valid asylum claims to enter the United States and file frivolous applications (see "Frivolous or Fraudulent Asylum Claims").

Regarding the affirmative asylum backlog, USCIS described its January 2018 decision to interview more recent asylum applications before older filings as "an attempt to stem the growth of the agency's asylum backlog."138 There is debate about whether this is an effective and judicious strategy. While some point to signs that this processing change is reducing the backlog,139 others argue that it is a wrongheaded approach and that USCIS should instead be dedicating more resources to adjudicating asylum cases. Those in the latter group argue that individuals with older, valid asylum claims will face even longer waits for relief under the last in-first out system.140

DHS efforts to reduce the asylum backlog are also impacting other humanitarian admissions programs. According to the report Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2019, "DHS in FY 2017 and FY 2018 shifted a significant proportion of its refugee officers to processing affirmative asylum applications and conducting credible fear and reasonable fear screenings. This reduced the number of refugee interviews that could be conducted abroad in those years."141 The report also indicates that the Administration plans to "continue to shift some refugee officers to assist the Asylum Division" in FY2019 to address the asylum backlog.142

Regarding the backlog of immigration court cases, the director of EOIR testified at an April 2018 Senate hearing that the agency was addressing challenges that had contributed to the backlog. In his prepared testimony, he cited the challenges of "declining case completions, protracted hiring times for new immigration judges, and the continued use of paper files."143