Immigration: Alternatives to Detention (ATD) Programs

Since FY2004, Congress has appropriated funding to the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS’s) Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) for an Alternatives to Detention (ATD) program to provide supervised release and enhanced monitoring for a subset of foreign nationals subject to removal whom ICE has released into the United States. These aliens are not statutorily mandated to be in DHS custody, are not considered threats to public safety or national security, and have been released either on bond, their own recognizance, or parole pending a decision on whether they should be removed from the United States.

Congressional interest in ATD has increased in recent years due to a number of factors. One factor is that ICE does not have the capacity to detain all foreign nationals who are apprehended and subject to removal, a total that reached nearly 400,000 in FY2018. (ICE reported an average daily population of 48,006 aliens in detention for FY2019, through June 22, 2019.) Other factors include recent shifts in the countries of origin of apprehended foreign nationals, increased numbers of migrants who are traveling with family members, the large number of aliens requesting asylum, and the growing backlog of cases in the immigration court system.

Currently, ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) runs an ATD program called the Intensive Supervision Appearance Program III (ISAP III). On June 22, 2019, program enrollment included more than 100,000 foreign nationals, who are a subgroup of ICE’s broader “non-detained docket” of approximately 3 million aliens. Those in the non-detained docket include individuals the government has exercised discretion to release—for example, they are not considered a flight risk or there is a humanitarian reason for their release (as well as other reasons). (Others who are not detained include aliens in state or federal law enforcement custody and absconders with a final order of removal.) Individuals in the non-detained docket, and not enrolled in the ISAP III program, receive less-intensive supervision by ICE. Those in ISAP III are provided varying levels of case management through a combination of face-to-face and telephonic meetings, unannounced home visits, scheduled office visits, and court and meeting alerts. Participants may be enrolled in various technology-based monitoring services including telephonic reporting (TR), GPS monitoring (location tracking via ankle bracelets), or a recently introduced smart phone application (SmartLINK) that uses facial recognition to confirm identity as well as location monitoring via GPS.

From January 2016 to June 2017, ICE also ran a community-based supervision pilot program for families with vulnerabilities not compatible with detention. The Family Case Management Program (FCMP) prioritized enrolling families with young children, pregnant or nursing women, individuals with medical or mental health considerations (including trauma), and victims of domestic violence. The program was designed to increase compliance with immigration obligations through a comprehensive case management strategy run by established community-based organizations. FCMP offered case management that included access to stabilization services (food, clothing, and medical services), obligatory legal orientation programing, and interactive and ongoing compliance monitoring. An ICE review of FCMP in March 2017 showed that the rates of compliance for the program were consistent with other ICE monitoring options. The program was discontinued due to its higher costs as compared to ISAP III. Even with the higher costs, there is considerable congressional interest in the effectiveness of FCMP as a way to maintain supervision for families waiting to proceed through the backlogged immigration court system.

While DHS upholds that ISAP III is neither a removal program nor an effective substitute for detention, it notes that the program allows ICE to monitor some aliens released into communities more closely while their cases are being resolved. Supporters of ATD programs point to their lower costs compared to detention on a per day rate, and argue that they encourage compliance with court hearings and ICE check-ins. Proponents also mention the impracticalities of detaining the entire non-detained population of roughly 3 million aliens. The primary argument against ATD programs is that they create opportunities for participants to abscond (e.g., evade removal proceedings and/or orders). Other concerns include whether the existence of the programs provides incentives for foreign nationals to migrate to the United States with children to request asylum, in the hope that they will be allowed to reside in the country for several years while their cases proceed through the immigration court system, or that it provides incentives—such as community release—for adults without bona fide family relationships to travel with children and file fraudulent asylum claims or do children harm.

Immigration: Alternatives to Detention (ATD) Programs

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Background

- Laws Governing Aliens Arriving at the U.S. Border

- Detention in the Immigration System

- ICE Caseload Size and ATD Participants

- Alternatives to Detention (ATD) Programs

- Intensive Supervision Appearance Program III (ISAP III)

- Who is in the ISAP III program?

- Evaluating ATD

- The Family Case Management Program (FCMP)

- Who was enrolled in the FCMP?

- Evaluating FCMP

- Why have alternatives to detention?

Figures

- Figure 1. ICE Caseload: Non-detained, Detained, and ISAP III Participants

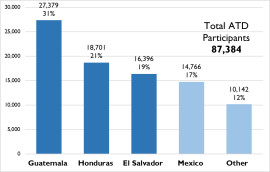

- Figure 2. ISAP III Active Participants by Country of Birth

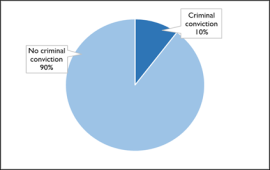

- Figure 3. ISAP III Active Participants by Criminal Conviction

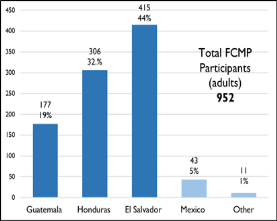

- Figure 4. FCMP Adult Participants by Country of Birth, 2017

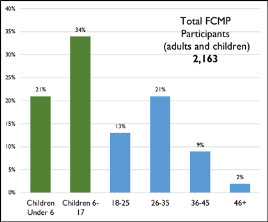

- Figure 5. All Participants (Children and Adults) by Age, 2017

- Figure 6. FCMP Participants by Vulnerability

Summary

Since FY2004, Congress has appropriated funding to the Department of Homeland Security's (DHS's) Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) for an Alternatives to Detention (ATD) program to provide supervised release and enhanced monitoring for a subset of foreign nationals subject to removal whom ICE has released into the United States. These aliens are not statutorily mandated to be in DHS custody, are not considered threats to public safety or national security, and have been released either on bond, their own recognizance, or parole pending a decision on whether they should be removed from the United States.

Congressional interest in ATD has increased in recent years due to a number of factors. One factor is that ICE does not have the capacity to detain all foreign nationals who are apprehended and subject to removal, a total that reached nearly 400,000 in FY2018. (ICE reported an average daily population of 48,006 aliens in detention for FY2019, through June 22, 2019.) Other factors include recent shifts in the countries of origin of apprehended foreign nationals, increased numbers of migrants who are traveling with family members, the large number of aliens requesting asylum, and the growing backlog of cases in the immigration court system.

Currently, ICE's Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) runs an ATD program called the Intensive Supervision Appearance Program III (ISAP III). On June 22, 2019, program enrollment included more than 100,000 foreign nationals, who are a subgroup of ICE's broader "non-detained docket" of approximately 3 million aliens. Those in the non-detained docket include individuals the government has exercised discretion to release—for example, they are not considered a flight risk or there is a humanitarian reason for their release (as well as other reasons). (Others who are not detained include aliens in state or federal law enforcement custody and absconders with a final order of removal.) Individuals in the non-detained docket, and not enrolled in the ISAP III program, receive less-intensive supervision by ICE. Those in ISAP III are provided varying levels of case management through a combination of face-to-face and telephonic meetings, unannounced home visits, scheduled office visits, and court and meeting alerts. Participants may be enrolled in various technology-based monitoring services including telephonic reporting (TR), GPS monitoring (location tracking via ankle bracelets), or a recently introduced smart phone application (SmartLINK) that uses facial recognition to confirm identity as well as location monitoring via GPS.

From January 2016 to June 2017, ICE also ran a community-based supervision pilot program for families with vulnerabilities not compatible with detention. The Family Case Management Program (FCMP) prioritized enrolling families with young children, pregnant or nursing women, individuals with medical or mental health considerations (including trauma), and victims of domestic violence. The program was designed to increase compliance with immigration obligations through a comprehensive case management strategy run by established community-based organizations. FCMP offered case management that included access to stabilization services (food, clothing, and medical services), obligatory legal orientation programing, and interactive and ongoing compliance monitoring. An ICE review of FCMP in March 2017 showed that the rates of compliance for the program were consistent with other ICE monitoring options. The program was discontinued due to its higher costs as compared to ISAP III. Even with the higher costs, there is considerable congressional interest in the effectiveness of FCMP as a way to maintain supervision for families waiting to proceed through the backlogged immigration court system.

While DHS upholds that ISAP III is neither a removal program nor an effective substitute for detention, it notes that the program allows ICE to monitor some aliens released into communities more closely while their cases are being resolved. Supporters of ATD programs point to their lower costs compared to detention on a per day rate, and argue that they encourage compliance with court hearings and ICE check-ins. Proponents also mention the impracticalities of detaining the entire non-detained population of roughly 3 million aliens. The primary argument against ATD programs is that they create opportunities for participants to abscond (e.g., evade removal proceedings and/or orders). Other concerns include whether the existence of the programs provides incentives for foreign nationals to migrate to the United States with children to request asylum, in the hope that they will be allowed to reside in the country for several years while their cases proceed through the immigration court system, or that it provides incentives—such as community release—for adults without bona fide family relationships to travel with children and file fraudulent asylum claims or do children harm.

Background

In recent years, the Trump Administration and Congress have grappled with how to address the substantial number of migrants from the Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras arriving to the U.S. Southwest border. Many observers have criticized what they label as "catch and release," a colloquial phrase used to describe the process by which apprehended asylum seekers who lack valid documentation are subsequently released into the U.S. interior while they await their immigration hearings. This occurs because of growing backlogs in the immigration court system leading to wait times for immigration hearings now often lasting two years or more,1 and a lack of appropriate detention space for families due to the limitations imposed by the Flores Settlement Agreement, which restricts the government's ability to detain alien minors.2 Such observers argue that many apprehended aliens who are released into the United States do not appear for their immigration hearings and become part of the unlawfully present alien population.3

In light of these circumstances, Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Alternatives to Detention (ATD) programs4 are generating increased congressional interest as a way to monitor and supervise foreign nationals who are released while awaiting their immigration hearings. Proponents of ATD programs cite their substantially lower daily costs compared with detention, the high compliance rates of ATD participants with immigration court proceedings, and what they characterize as a more humane approach of not detaining low-flight-risk foreign nationals, many of whom are asylum applicants (particularly family units).5 Critics contend that ATD programs provide opportunities for participants to abscond (e.g., evade removal proceedings and/or orders) and create incentives for migration by allowing people to live in the United States for extended periods while awaiting the resolution of their case. They also question the effectiveness of these types of monitoring programs as a removal tool (i.e., as a means to remove participants ordered removed from the United States).6 DHS, for its part, states that nothing compares to detention for ensuring compliance.7 However, existing capacity to hold aliens is limited.

Immigration statistics indicate that while the total number of individuals apprehended at the Southwest border has generally declined over the past two decades, the demographic profile of those apprehended has shifted toward a population more likely to be subject to detention.8 Historically, most unauthorized aliens apprehended at the Southwest border have been adult Mexican males who are considered to be "economic" migrants because they are primarily motivated by the opportunity to work in the United States, and who can be more easily repatriated without requiring detention.9 However, over the past five years, apprehensions of aliens from the Northern Triangle countries—many of whom are reportedly fleeing violence and seeking asylum in the United States—have exceeded those from Mexico.10

Since 2017, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has reported a sharp increase in the number of apprehensions at the Southwest border, especially among members of family units11 and unaccompanied alien children (UAC).12 Together, persons in family units and UAC currently make up more than two-thirds of apprehensions. In May 2018, the number of apprehensions by the U.S. Border Patrol plus the number of aliens determined inadmissible by CBP's Office of Field Operations (OFO) totaled 22,000; in April 2019, that number was 100,569, a 357% increase.13 In contrast, the number of single adults who were apprehended or found inadmissible rose from 24,493 to 43,637, a 46% increase, during the same time period. Foreign nationals from the Northern Triangle are requesting asylum at high rates that are DHS officials say are overwhelming the ability of federal agencies to process their detention, adjudication, and removal.14

Laws Governing Aliens Arriving at the U.S. Border

The U.S. Border Patrol is responsible for immigration enforcement at U.S. borders between ports of entry (POEs). CBP's Office of Field Operations (OFO) handles the same responsibilities at the POEs. Foreign nationals seeking to enter the United States may request admission legally at a POE. In some cases, aliens attempt to enter the United States illegally, typically between POEs on the southern border.15 If apprehended, they are processed and detained briefly by Border Patrol; placed into removal proceedings; and, depending on the availability of detention space, either transferred to the custody of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) or released into the United States.16

Removal proceedings take one of two forms (streamlined or standard) depending on how the alien attempted to enter the United States, his/her country of origin, whether he/she is an unaccompanied child or part of an arriving family unit, and whether he/she requests asylum. If the alien is determined by an immigration officer to be inadmissible to the United States because he/she lacks proper documentation or has committed fraud or willful misrepresentation in order to gain admission, the alien may be subject to a streamlined process known as expedited removal. Expedited removal allows for the alien to be ordered removed from the United States without any further hearings or review.17 UAC, however, are not subject to expedited removal. Instead, if they are subject to removal, they are placed in standard removal proceedings and transferred to the Department of Health and Human Services' (HHS') Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) pending those proceedings.18

Although most aliens arriving in the United States without valid documentation are subject to expedited removal, they may request asylum,19 a form of relief granted to foreign nationals physically present within the United States or arriving at the U.S. border who meet the definition of a refugee.20 During CBP's initial screening process, if the alien indicates an intention to apply for asylum or a fear of persecution in his/her home country, the alien is interviewed by an asylum officer from DHS's U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) to determine whether she/he has a "credible fear of persecution."21 If the alien establishes a credible fear, she/he is placed into standard removal proceedings under Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) §240 and may pursue an asylum application at a hearing before an immigration judge.

Those who receive a negative credible fear determination may request that an immigration judge review that finding. If the immigration judge overturns the negative credible fear finding, the alien is placed in standard removal proceedings; otherwise, the alien remains subject to expedited removal and is usually deported.

Aliens may be detained or granted parole while in standard removal proceedings. During these proceedings, immigration judges within the Department of Justice's (DOJ's) Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) conduct hearings to determine whether a foreign national is subject to removal or eligible for any relief or protection from removal. While immigration judges have the authority to make custody decisions, ICE makes the initial decision whether to detain or release the alien into the United States pending removal proceedings. Most asylum seekers who are members of family units are currently being released into U.S. communities to await their immigration hearings.22

Detention in the Immigration System

The INA authorizes DHS to arrest, detain, remove, or release foreign nationals subject to removal.23 Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) is the office within ICE that is charged with detention and removal of aliens from the United States. Generally, aliens may be detained pending removal proceedings, but detention is discretionary if the alien is not subject to mandatory detention.24 Detention is mandatory for certain classes of aliens (e.g., those convicted of specified crimes) with no possibility of release except in limited circumstances.25

During the intake process, an ERO officer uses the ICE Risk Classification Assessment (RCA), a software tool that attempts to standardize custody decisions across all ERO offices, to evaluate whether a foreign national should be detained or released on a case-by-case basis.26 The factors used to make the detention decision include, but are not limited to, criminal history, alleged gang affiliation, previous compliance history, age (must be at least 18), community or family ties, status as a primary caregiver or provider to family members, medical conditions, or other humanitarian conditions.27

Typically, an alien may be released from ICE custody on an order of recognizance,28 bond,29 or parole on humanitarian grounds.30 For example, aliens initially screened for expedited removal who request asylum are generally subject to mandatory detention pending their credible fear determinations, and, if found to have a credible fear, pending their standard removal proceedings; however, DHS has the discretion to parole the alien into the United States pending those proceedings.31

Pursuant to a court settlement agreement, alien minors may be detained by ICE for only a limited period,32 and must be released to an adult sponsor or a non-secure, state licensed child welfare facility pending their removal proceedings. Due to these legal restrictions and a lack of appropriate facilities for family units, DHS typically releases family units with accompanying minors, if they are subject to removal, pending their removal proceedings because there are not enough licensed shelters available to detain the number of family units arriving at the Southwest border. Thus, if family units entering the United States request asylum and receive a positive credible fear determination, they typically will not be detained throughout their removal proceedings.

In addition, as noted previously, UAC are generally transferred to the custody of ORR pending the outcome of their removal proceedings.33 Thus, like family units, UAC typically are released from DHS custody and placed in the non-detained docket during those proceedings.

All aliens released from ICE custody into the U.S. interior are assigned to the non-detained docket and must report to ICE at least once a year.34 ICE's non-detained docket currently has approximately 3 million cases.35 Some portion of those in the non-detained docket are enrolled in an ATD monitoring program, but all aliens in the non-detained docket are awaiting a decision on whether they should be removed from the United States.36

The number of initial "book-ins"37 to an ICE detention facility (by ICE and CBP combined) has exceeded 300,000 annually in recent years, peaking in 2014 at 425,728, and reaching nearly 400,000 in FY2018.38 Even though there were nearly 400,000 admissions to detention in FY2018, the number of book-ins does not describe the population of aliens who are in a detention facility on any given day. Instead, the number of aliens in detention on a given day is determined by the number of book-ins, the length of stay in detention, and the number of beds authorized by Congress. In FY2019, the number of detention beds authorized by Congress was set at 45,274, up nearly 5,000 from the previous year, and more than 10,000 greater than FY2016. ICE reported that 54,082 aliens were currently detained on June 22, 2019.39

ICE Caseload Size and ATD Participants

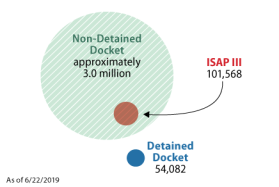

Figure 1 shows the ICE caseload, which consists of all detained and non-detained aliens that ICE must supervise as part of its docket management responsibilities.

As mentioned above, non-detained aliens include those released from ICE custody on various types of orders, including orders of recognizance, parole, and bond, and those who were never detained.40 The ICE non-detained docket also includes aliens in state or federal law enforcement custody and at-large aliens with final orders of removal (e.g., fugitives).41 Those released from ICE custody are required to report to ERO at least once annually, but the frequency is at the discretion of ERO.42 The non-detained docket caseload is monitored as aliens move through immigration court proceedings until their cases close.43 Aliens in ATD have secured a legal means of release (i.e., bond or parole); participating in ATD is a condition of their release.

As noted, ICE's full non-detained caseload was approximately 3 million foreign nationals on June 22, 2019.44 On that same date, ICE reported that there were 54,082 detained aliens, less than 2% of the entire ICE caseload. Included in the ICE non-detained caseload are 101,568 aliens, approximately 3% of all cases (See Figure 1), enrolled in ISAPIII.45

The goal of the ICE ATD program is to monitor and supervise certain aliens in removal proceedings more frequently relative to those released with annual supervision. Those in ATD are required to report to ERO annually as well, but they are also subject to varying degrees of supervision and monitoring at more frequent intervals on a case-by-case basis (see description of "Alternatives to Detention (ATD) Programs"). More broadly, DHS maintains that ATD programs should not be considered removal programs or a substitute for detention. Instead, according to DHS, these programs have enhanced ICE's ability to monitor more intensively a subset of foreign nationals released into communities.

|

Figure 1. ICE Caseload: Non-detained, Detained, and ISAP III Participants |

|

|

Source: ICE Detention Management Statistics, as of June 22 2019, https://www.ice.gov/detention-management. |

Alternatives to Detention (ATD) Programs

Intensive Supervision Appearance Program III (ISAP III)

ICE's Intensive Supervision Appearance Program III (ISAP III) is the third iteration of the ATD program started by the agency in 2004. 46 It is the only ATD program currently operated by ERO.47 To be eligible for this program, participants must be 18 years of age or older and at some stage of their removal proceedings.48 The most recent publicly available data show that there were 101,568 active participants enrolled in ISAP III, 49 which is a 283% increase over the 26,625 enrollees in FY2015.50

Those enrolled in ISAP III are supervised largely by BI, Inc.,51 a private company that provides ICE with case management and technology services in an attempt to ensure non-detained aliens' compliance with release conditions, attendance at court hearings, and removal.52 ERO ATD officers determine case management and supervision methods on a case-by-case basis. Case management can include a combination of face-to-face and telephonic meetings, unannounced visits to an alien's home, scheduled office visits by the participant with a case manager, and court and meeting alerts. Technology services may include telephonic reporting (TR), GPS monitoring (via ankle bracelets), or a relatively new smartphone application (SmartLINK) that allows enrolled aliens to check in with their case workers using facial recognition software to confirm their identity at the same time that their location is monitored by the GPS capabilities of the smartphone.53 As of June 22, 2019, approximately 42% of active participants in the ISAP III program used telephonic reporting, 46% used GPS monitoring, and 12% used SmartLINK.54

According to a 2014 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report, enrollees in ICE ATD programs are closely supervised at the beginning of their participation.55 If they are compliant with the terms of their plans in the first 30 days, the level of supervision may be lowered. Various compliance benchmarks are tracked in order to make decisions about whether supervision should be reduced or increased. If a final order of removal is issued, supervision usually increases until resolution of the case. ICE typically ends an alien's participation in the program when they are removed, depart voluntarily,56 or are granted relief from removal through either a temporary or permanent immigration benefit.57

Who is in the ISAP III program?58

Statistics obtained from ERO59 show that of the 87,384 enrollees in ISAP III on August 31, 2018, approximately 61% were female and 56% were members of family units (at least one adult with at least one child). Approximately 61% of participants were between the ages of 18 and 34, another 38% were 35-54, and 2% were 55 and older.60 Seventy-one percent of ISAP III enrollees were from the Northern Triangle countries of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador (Figure 2). Participants from Mexico made up 17% of the total, and the remaining 12% were from all other countries (Figure 2). Ninety percent had no record of a criminal conviction (Figure 3). Although all foreign nationals in ISAP III are in removal proceedings, most (86%) did not yet have a final order of removal on the date that these data were made available. Fourteen percent had a final order of removal; 19% of these aliens had appealed their removal order.61

Evaluating ATD

In 2014, GAO evaluated ISAP III's predecessor program, ISAP II, during the FY2011 to FY2013 period.62 This iteration of the program had two supervision options, "full service" and "technology only," thus the results of the GAO evaluation of ISAP II have limited utility for better understanding the effectiveness of ISAP III (which has not been similarly evaluated).

The GAO evaluation of ISAP II noted that ICE had established two program performance measures to assess the effectiveness of the program: ensuring compliance with court appearance requirements and securing removals from the United States.63 However, GAO stated that limitations in data collection interfered with its ability to assess overall program performance.64

GAO found high rates of compliance with court appearances among full service ISAP II enrollees in the FY2011-FY2013 time period: 99% of participants appeared at their court hearings, dropping to 95% if it was their final removal hearing. Similar data was not collected for participants enrolled in the technology-only component, which amounted to 39% of the total participants in 2013.65 GAO subsequently reported that ICE, through its contractor, began collecting court compliance data for approximately 88% of the total participants, who were managed by either ICE or the contractor.66

According to ICE officials, as reported by GAO, ICE added a performance measure based on removals in 2011 because "the court appearance rate had consistently surpassed 99 percent and the program needed to establish another goal to demonstrate improvement over time."67

GAO found that ICE met its ISAP II program goal for the number of removals for FY2012 and FY2013.68 For each of these years, the removal goal was a 3% increase in the number of removals from the previous fiscal year. In FY2012, the removal goal was 2,815, and ICE met it by removing 2,841 program participants from the United States. In FY2013, the removal goal was increased to 2,899, and ICE removed 2,901 program participants from the United States.69

Even though GAO was able to report on ISAP II removal and court compliance performance measures, it determined that data collection limitations hampered its ability to fully evaluate ISAP II's performance.70 For example, as described above, data collection on court appearance rates was inconsistent and incomplete for over one-third of program participants.71 ICE's performance measures were based on data collected at the time of an alien's termination from ISAP II, but ICE could not determine whether the alien complied with all of the terms of his/her release while participating in the program or absconded, due to incomplete record keeping and limited resources to maintain contact.72 GAO concluded that these performance measures and rates provided an incomplete picture of enrollees who were terminated from ISAP II prior to receiving final disposition of immigration proceedings, making it impossible to know how many were removed, departed voluntarily, or absconded.73

The Family Case Management Program (FCMP)

The Family Case Management Program (FCMP), which operated from January 2016 until June 2017, was an ATD pilot program for families with vulnerabilities not compatible with detention. An ICE review of the program published in March 2017 showed that although the rates of compliance for the FCMP were consistent with other ICE monitoring options, FCMP daily costs per family unit were higher than ISAP III.74 The program was discontinued.

The FCMP prioritized families with young children or pregnant or nursing women, individuals with medical or mental health considerations (including trauma), and victims of domestic violence.75 The program was designed to increase compliance with immigration obligations through a comprehensive case management strategy supported by established community-based organizations (CBOs).76 A private contractor, GEO Care, Inc., entered into agreements with local CBOs that provided case management and other services.77

The program operated as follows.78 Each family was assigned to a case manager and offered three sets of services. First, participants were offered "initial stabilization" services, such as referrals for legal assistance, medical and food assistance, and English language training, based on the premise that stable families are more likely to comply with immigration requirements. Second, participants were required to attend legal orientation programs, which included presentations about immigration proceedings, obligations of participants, and legal representation. These programs were also designed to orient enrollees in understanding basic U.S. laws covering issues such as child supervision, domestic violence, and driving while intoxicated. Third, the program was specifically intended to reinforce information pertinent to aliens' cases through frequent reporting requirements, typically monthly office and home visits with case managers and monthly appointments with ERO. Ongoing relationships with case workers were developed to build trust in the immigration system and set clear expectations of the legal process, as well as to provide planning assistance for the eventuality of return, removal, or an immigration benefit that would offer relief from removal. Individualized and interactive oversight of cases and a flexible monitoring plan (similar to ISAP III) were implemented to provide a range of supervision options—supervision was typically high while families stabilized their situations, and lower (conducted by ERO only) once they were considered stabilized.

Who was enrolled in the FCMP?

The program enrolled 952 heads of households with 1,211 children, for a total of 2,163 individuals in five metropolitan areas around the country.79

|

|

|

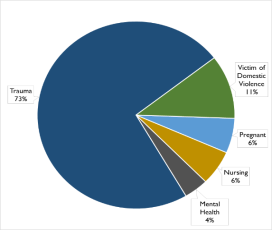

According to a 2018 ICE internal close-out report, most of the families in the program (92%) were headed by women; and most of the participants (95%) were from the Northern Triangle countries—El Salvador (44%), Honduras (32%), and Guatemala (19%) (Figure 4).80 Overall, 55% of the program participants were children under the age of 18; 21% of children were under age 6. Twenty-one percent of program participants were between the ages of 26 and 35, 13% were 18-25, 9% were 36-45, and 2% were 46 or older (Figure 5). All participants enrolled in the FCMP were individually assessed for vulnerabilities and needs. Seventy-three percent had experienced some kind of trauma, 11% were victims of domestic violence, 6% were pregnant, 6% were nursing, and 4% had mental health concerns (Figure 6).81

|

|

Source: Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Family Case Management Program (FCMP) [INTERNAL] Close-Out Report, February 2018. |

Evaluating FCMP

ICE conducted an evaluation of the FCMP that focused on three metrics: attendance at ERO appointments, attendance at appointments with community-based organizations, and attendance at court hearings.82 Data on compliance of the relatively small number of families that completed the program prior to its termination reported it to be high across all locations, with 99% attendance at immigration court proceedings and 99% compliance with ICE monitoring requirements.83 About 4% of program participants absconded during the life of the program. In total, 65 families left the program: 7 were removed from the United States by ICE, 8 left the country on their own, 9 were granted some form of immigration relief, and 41 absconded. The rest of the families remained in the program; however, because of its short duration the ICE evaluation of the FCMP is limited—the majority of the participants were still in immigration proceedings when it was terminated. It is unknown what the program's success rates would have been if participants were allowed to remain in the program through the final outcome of their cases. When ICE discontinued the program in June 2017, the agency stated that rates of compliance for the FCMP were consistent with its other ATD program (i.e., ISAP III).

In addition to compliance rates, another important factor in evaluating the program is its cost. The FCMP cost approximately $38.47 per family per day in FY2016, versus approximately $4.40 per person per day for ISAP III. By comparison, family detention costs an estimated $237.60 per day and adult detention in the same cities that the FCMP operated in cost $79.57 on average per day in FY2016.84 The FCMP is more expensive than ISAP III due to the comprehensive case management and services available to its participants, the more vulnerable family populations targeted, and the smaller caseload per case manager (which allowed for more time with each participant household). For example, FCMP case managers were expected to have a high level of experience, used outreach (not just referrals) to connect participants with community resources, had Spanish language ability or accessed interpretation services, and developed individualized plans for families, including children. The evaluation indicated that FCMP families made use of the services offered to them: the most common referrals made by case workers were for legal services, medical attention, and food aid.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2019 (P.L. 116-6) includes $30.5 million to resume the FCMP. The conference report85 states that the FCMP "can help improve compliance with immigration court obligations by helping families access community-based support of basic housing, healthcare, legal and educational needs." The conference report also directs ICE to prioritize the use of ATD programs, including the FCMP, for families. In addition, the report instructs ICE to brief the relevant committees,86 within 90 days of the date of enactment,87 on a plan for a program within the FCMP managed by nonprofit organizations that have experience in connecting families with community-based services.

The ICE ERO Detention Management website mentions a new program, Extended Case Management Services (ECMS). It states, "as instructed by Congress, ICE recently incorporated many of the Family Case Management Program (FCMP) principles into its traditional ATD program. These principles were incorporated into the current ATD ISAP III through a contract modification and are known as Extended Case Management Services (ECMS). These same services are available through the ECMS modification as they were available under FCMP with two distinct differences: ECMS is available in a higher number of locations and available at a fraction of the cost. While ECMS is a new program, ICE continues to identify and enroll eligible participants." As of June 22, 2019, ICE reported that 57 family units and 59 adults are enrolled in ECMS.88

Why have alternatives to detention?

Supporters of ATD programs cite several reasons for their use. First, the number of foreign nationals currently being taken into custody far exceeds the capacity of existing detention facilities. As noted above, in FY2018 the number of book-ins to ICE facilities was nearly 400,000.89 As of July 12, 2018, ICE's detention capacity was approximately 45,700 beds; of these, approximately 2,500 were for family units housed in family residential centers.90 Second, many foreign nationals who are in removal proceedings are not considered security or public safety threats, nor are they an enforcement priority as outlined in guidance to DHS personnel regarding immigration enforcement.91 Third, some foreign nationals who are found deportable or inadmissible may not be removed because their countries of citizenship refuse to confirm an individual's identity and nationality, issue travel documents, or otherwise accept their physical return.92 A U.S. Supreme Court ruling from 2001, Zadvydas v. Davis, limits the federal government's authority to indefinitely detain aliens who have been ordered removed and who have no significant likelihood of removal in the reasonably foreseeable future.93

Those who promote using ATD programs also cite the relatively low cost compared with detention. ICE spent an average of $137 per adult per day in detention nationwide in FY2018.94 The cost of enrolling foreign nationals in the ISAP III program depends on the method of management, but the average daily cost per participant in FY2018 (through July 2018) was $4.16.95 GAO utilized two methods of determining the cost of ATD (ISAP II) relative to detention in FY2013 (at that time, the average daily cost of ISAP II was $10.55, while daily detention was an average of $158). First, given the average daily costs of ATD and detention, and the average length of time an alien spent in detention awaiting an immigration judge's final decision, GAO found that the cost of maintaining an enrollee in ISAP II would surpass the costs of detention only if the enrollee were in the program for 1,229 days, which would be 846 days longer than the average number of days a participant typically spent in it. Second, given the average cost of ATD and detention, and the average length of time an alien spent in detention regardless of whether a final decision on her/his case was rendered, GAO determined an individual would have to spend, on average, 435 days in ISAP II before they exceeded the cost of the average length of detention (29 days in FY2013).96

There are also arguments against using ATD programs. Of primary concern is that the programs, in comparison to detention, create opportunities for aliens in removal proceedings to abscond and become part of the unauthorized population who are not allowed to lawfully live or work in the United States. Because immigration judges must prioritize detained cases, ATD enrollees must often wait several years before their cases are heard, during which time they may abscond. They may also fall out of contact with ERO for other reasons. For example, an alien may move within the United States and fail to provide updated contact information to ERO. If they do not receive communication from ICE or the immigration court system, they could miss court dates that have changed in the interim. If they fail to show up for a removal hearing, for example, they can be ordered removed in absentia, which would render them inadmissible for a certain period (at least 5 years if they are an arriving alien, and at least 10 years for all other aliens) and ineligible for certain forms of relief from removal for 10 years.

Another concern is that asylum-seeking families are often placed into ATD, and this creates incentives for others to travel to the United States with children, request asylum, and receive similar conditions of release into the United States. DHS has expressed concern over adults using children as a "human shields" to avoid detention after illegally entering the United States.97 Those without bona fide family relationships may travel with children and file fraudulent claims or do harm to children.98 Recent reports of children being "recycled"—crossing into the United States with an adult or a family, only to be returned across the border to travel with another migrant—has prompted DHS to take biometric data, such as fingerprints, from children.99

Additional arguments against using ATD programs include that reliable measures of their effectiveness are limited, as discussed above in "Evaluating ATD" and "Evaluating FCMP," and for the FCMP pilot, that the feasibility of scaling up a small pilot program to accommodate the large number of families requesting asylum remains an open question.

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

Mariam Ghavalyan, research assistant in CRS's Domestic Social Policy Division, provided research and graphics assistance, and Amber Wilhelm, visual information specialist in CRS's Publishing and Editorial Resources Section, provided graphics assistance for this report.

Footnotes

| 1. |

As of February 28, 2019, waiting periods for immigration cases were averaging 728 days nationwide. TRAC, "Average Time Pending Cases Have Been Waiting in Immigration Courts as of January 2019," https://trac.syr.edu/phptools/immigration/court_backlog/apprep_backlog_avgdays.php. |

| 2. |

See CRS Report R45297, The "Flores Settlement" and Alien Families Apprehended at the U.S. Border: Frequently Asked Questions. |

| 3. |

See, for example, Dan Cadman, "Punishing" Apprehended Illegal Aliens with Alternatives to Detention? Center for Immigration Studies, May 2017, https://cis.org/Cadman/Punishing-Apprehended-Illegal-Aliens-Alternatives-Detention. |

| 4. |

Although DHS uses the term "Alternatives to Detention," in practice, these programs may more accurately be described as increased supervision programs for individuals whom ICE has determined can be released from custody. Individuals released from custody are placed in the non-detained docket. The non-detained docket includes both aliens released from detention waiting for an immigration court hearing and those released from detention with final deportation orders. See Department of Homeland Security and Office of Inspector General, ICE Deportation Operations, April 13, 2017, p. 6, https://www.oig.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/assets/2017/OIG-17-51-Apr17.pdf. |

| 5. |

See, for example, National Immigrant Justice Center, The Real Alternatives to Detention, June 18, 2017, https://immigrantjustice.org/sites/default/files/content-type/research-item/documents/2018-06/The%20Real%20Alternatives%20to%20Detention%20FINAL%2006.17.pdf; and Alex Nowrasteh, Alternatives to Detention are Cheaper than Universal Detention, Cato Institute, June 20, 2018, https://www.cato.org/blog/alternatives-detention-are-cheaper-indefinite-detention. |

| 6. |

See, for example, Dan Cadman, Are 'Alternative to Detention' Programs the Answer to Family Detention?, Center for Immigration Studies, June 28, 2018, https://cis.org/Cadman/Are-Alternative-Detention-Programs-Answer-Family-Detention. |

| 7. |

ICE written communication with CRS, May 7, 2019. |

| 8. |

For details on immigration trends, see Appendix A of CRS Report R45266, The Trump Administration's "Zero Tolerance" Immigration Enforcement Policy. |

| 9. |

Ibid. |

| 10. |

U.S. Customs and Border Protection, U.S. Border Patrol Apprehensions From Mexico and Other Than Mexico (FY 2000 - FY 2017) https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2017-Dec/BP%20Total%20Apps%2C%20Mexico%2C%20OTM%20FY2000-FY2017.pdf. |

| 11. |

The term "family unit," which is not found in statute, commonly refers to two or more related individuals, one of whom is a parent or legal guardian of the other(s). CBP defines "family unit" as the number of individuals (either a child under 18 years old, parent, or legal guardian) apprehended with a family member by the U.S. Border Patrol. In its apprehension statistics, CBP uses the term "family unit" to count all individuals who are apprehended as part of a group of such related individuals, not a count of the families. U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Southwest Border Migration FY 2018, https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration/fy-2018; and Southwest Border Migration FY 2019, https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration. |

| 12. |

Unaccompanied alien children are defined in statute as children who lack lawful immigration status in the United States, are under the age of 18, and are arriving without either a parent or legal guardian or do not have a parent or legal guardian in the United States who is available to provide care and physical custody (6 U.S.C. §279(g)(2)). |

| 13. |

See U.S Border Patrol statistics: U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions FY2018 and FY2019 and Office of Field Operations Southwest Border Inadmissibles FY2018 and FY2019, https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration. |

| 14. |

Some have characterized the immigration system as reaching a breaking point. See, for example, Michael D. Shear, Miriam Jordan and Manny Fernandez, "The U.S. Immigration System May Have Reached a Breaking Point," New York Times, April 10, 2019. |

| 15. |

For more information on arrivals, see CRS In Focus IF11074, U.S. Immigration Laws for Aliens Arriving at the Border. |

| 16. |

CBP may refer aliens to DOJ for criminal prosecution if they meet criminal enforcement priorities (e.g., child trafficking, prior felony convictions, multiple illegal entries). See CRS In Focus IF11074, U.S. Immigration Laws for Aliens Arriving at the Border. |

| 17. |

P.L. 104-208, Div. C, §302(a), amending INA §235 (8 U.S.C. §1225). |

| 18. |

8 U.S.C. §1232(b)(3). |

| 19. |

Asylum can be requested by foreign nationals who have legally entered the United States and are not in removal proceedings ("affirmative" asylum, not discussed in this report) or by those who are in removal proceedings and claim asylum as a defense to being removed ("defensive" asylum). For more on asylum, see CRS Report R45539, Immigration: U.S. Asylum Policy. |

| 20. |

The INA (INA §208 (8 U.S.C. §1158)) provides for the granting of asylum to aliens who fit the refugee definition: a person unable or unwilling to return to, or avail himself or herself of the protection of, his/her home country because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution based on one of five protected grounds: race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. |

| 21. |

8 U.S.C. §1225(b)(1)(A)(ii). Under INA §235(b)(1)(B)(v), for purposes of this subparagraph, the term "credible fear of persecution" means that there is a significant possibility, taking into account the credibility of the statements made by the alien in support of the alien's claim and such other facts as are known to the officer, that the alien could establish eligibility for asylum under 8 U.S.C. § 1158. |

| 22. |

See CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10150, An Overview of U.S. Immigration Laws Regulating the Admission and Exclusion of Aliens at the Border. |

| 23. |

INA §§235, 236, 287. |

| 24. |

For background information on immigration detention, see archived CRS Report RL32369, Immigration-Related Detention. |

| 25. |

INA §§235(b)(1)(B)(ii), (iii)(IV), 235(b)(2)(A), 236(c). |

| 26. |

RCA is part of the Enforce Alien Removal Module (EARM) Suite used to process individuals taken into ICE custody that uses a methodology developed by ICE to consider a range of factors to inform a custody determination. |

| 27. |

ICE email response to CRS request, October 18, 2018. |

| 28. |

Orders of recognizance and supervision are types of orders that release an individual with reporting conditions. See CRS Report R43892, Alien Removals and Returns: Overview and Trends. |

| 29. |

According to USCIS, bond is the amount of money set by DHS or an immigration judge as a condition to release a person from detention for an immigration court hearing at a later date. |

| 30. |

ICE response to CRS request, October 18, 2018. |

| 31. |

See CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10297, Attorney General Rules that Unlawful Entrants Generally Must Remain Detained While Asylum Claims Are Considered. |

| 32. |

For more on ICE detention of families in accordance with the Flores Settlement Agreement, see CRS Report R45297, The "Flores Settlement" and Alien Families Apprehended at the U.S. Border: Frequently Asked Questions. |

| 33. |

UAC are transferred to ORR per 8 U.S.C. §1232(b)(3) if they are from a country not contiguous with the United States, or from Mexico or Canada and have a credible fear of persecution. |

| 34. |

The frequency of "check-ins" is at the discretion of ERO (ICE email response to CRS request, October 18, 2018). |

| 35. |

According to ICE Detention Management statistics, there are currently "over 3 million individuals assigned to the non-detained docket," see https://www.ice.gov/detention-management. |

| 36. |

See CRS Report R42138, Border Security: Immigration Enforcement Between Ports of Entry. |

| 37. |

An initial book-in is the start of a unique detention stay. |

| 38. |

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2014, ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report Fiscal Year 2014; U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2018, Fiscal Year 2018 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report. However ICE Detention Management Statistics show 416,631 book-ins as of the week of June 22, 2019. If current trends continue apace, the total for FY2019 may exceed the previous high point in FY2014. See https://www.ice.gov/detention-management |

| 39. |

ICE Detention Management Statistics as of June 22, 2019, https://www.ice.gov/detention-management. |

| 40. |

Once an alien has been ordered removed, if the alien is released from detention that release is on an order of supervision. See INA §241(a)(3); 8 C.F.R. §241.5. |

| 41. |

ICE email response to CRS request, October 18, 2018. |

| 42. |

ICE email response to CRS request, October 18, 2018. |

| 43. |

In April 2017, the DHS Office of Inspector General (OIG) reported several challenges to the management of non-detained foreign nationals more generally. The first is that caseloads of deportation officers vary greatly among those supervising detained and non-detained aliens, with those with responsibility for the non-detained aliens having a much larger number of cases. The OIG found that cases are distributed arbitrarily to deportation officers and recommended that ICE review staffing allocations and develop a new model. The OIG also found that policies and procedures are not clearly communicated to assist deportation officers in their jobs, and that ICE does not offer standardized training. ICE concurred with both of these findings. See Department of Homeland Security and Office of Inspector General, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement's Alternatives to Detention (Revised), February 4, 2015. |

| 44. |

ICE Detention Management Statistics as of June 22, 2019, https://www.ice.gov/detention-management. |

| 45. |

Ibid. |

| 46. |

ICE, "ICE Announces Alternative Detention Program," June 18, 2004; this press release is no longer available on the DHS website, but is found in AILA Doc. No 04061836, https://www.aila.org/infonet/ice-announces-alternative-detention-program. This report uses ATD as an umbrella term to refer to all ATD programs run by ICE, including ISAP III and its predecessors (ISAP I and ISAP II). The Family Case Management Program (FCMP) is identified separately when referenced. |

| 47. |

The Intensive Supervision Appearance Program II (ISAP II) preceded the current program; it was run by a contractor from 2009 to 2014 with two supervision options. Prior to that, the first iteration of ISAP ran from 2004 to 2009 with three separate programs operated by two contractors. Both ISAP I and ISAP II were limited in geographic scope. ISAP III is available nationwide in over 100 locations, and for participants residing within all ICE Areas of Responsibility (AORs). |

| 48. |

ICE email response to CRS request, October 18, 2018. |

| 49. |

ICE Detention Management Statistics as of June 22, 2019, https://www.ice.gov/detention-management. |

| 50. |

Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Budget Overview, Fiscal Year 2019 Congressional Justification. |

| 51. |

BI Incorporated is an electronic monitoring company providing a continuum of monitoring technologies and related supervision services for unauthorized aliens in ICE's non-detained docket. |

| 52. |

Sometimes ICE chooses to monitor an alien directly, when it is in the agency's interest. |

| 53. |

ICE response to CRS request, October 18, 2018, and written communication, May 7, 2019. SmartLINK does not actively monitor the participant's location through their cell phone as a GPS ankle monitor would. SmartLINK obtains location (a latitude and longitude point) during the check-in while using facial recognition but does not gather GPS points at any other time. |

| 54. |

ICE Detention Management Statistics as of June 22, 2019, https://www.ice.gov/detention-management. |

| 55. |

U.S. Government Accountability Office, Alternatives to Detention: Improved Data Collection and Analyses Needed to Better Assess Program Effectiveness, 15-26, November 2014, https://www.gao.gov/assets/670/666911.pdf (hereinafter referred to as "GAO, 2014"). 2014 represents the most recent year that GAO or any other federal oversight entity reviewed the ATD programs. |

| 56. |

Voluntary departure under INA §240B, 8 U.S.C. §1229c, permits an alien to depart voluntarily from the United States at the alien's own expense in lieu of being subject to removal proceedings or prior to the completion of such proceedings, if the alien meets certain statutory requirements. |

| 57. |

For discussion of temporary and permanent types of relief from removal, see CRS Report R43892, Alien Removals and Returns: Overview and Trends. |

| 58. |

The data in this section of the report was obtained directly from ICE ERO. More recent publicly available data does not include the demographic information needed to describe in more detail the population under supervision by the ISAP III program. |

| 59. |

ICE provided detailed tabulations about the ATD population to CRS on August 31, 2018, when the population enrolled in ISAP III was 87,384. |

| 60. |

Due to rounding, these numbers do not sum to 100%. |

| 61. |

Numbers in this paragraph come from tabulations provided to CRS by ICE, August 31, 2018. |

| 62. |

GAO, 2014. |

| 63. |

Ibid, p. 30. |

| 64. |

Government Accountability Office, Immigration: Progress and Challenges in the Management of Immigration Courts and Alternatives to Detention Program, GAO-18-701T, September 18, 2018 (hereinafter, "GAO, 2018"). |

| 65. |

Ibid, p. 31. This is because when the program began, the plan was to have all participants in the full-service component that was run by the contractor. The technology-only component did not have the same data collection requirement and the agency determined it did not have sufficient resources to prioritize this data collection. |

| 66. |

According to GAO, 2018, as of June 2017, ICE reported that the contractor was collecting data on foreign nationals' court appearance compliance in both components. However, "ICE officials stated that they did not expect that 100 percent of foreign nationals in the ATD program would be tracked for court appearance compliance by the contractor because there may be instances where ICE has chosen to monitor a foreign national directly, rather than have the contractor track a foreign national's compliance with court appearance requirements" (p. 16). |

| 67. |

GAO, 2014, p. 32. |

| 68. |

A removal was attributed to ISAP II if the alien was enrolled in the program for at least one day and was removed or had departed voluntarily from the United States in the same fiscal year, regardless of whether the alien was still enrolled in the program when she/he left the country. |

| 69. |

GAO, 2014, p. 33. |

| 70. |

GAO, 2018. |

| 71. |

Ibid. |

| 72. |

Enrollees were terminated from the program when they were removed, returned, or receive some form of immigration relief. In addition, they were terminated if they were arrested by another law enforcement entity, absconded, or otherwise violated the terms of the program. In 2011, ICE recommended that ERO field offices cut costs by terminating participants who were not high priority (those new to the program or those with a final order of removal). |

| 73. |

GAO, 2018, p. 15. |

| 74. |

ICE email response to CRS request, August 21, 2018; "FCMP cost approximately $35.73 per day per enrollee in FY 2017, compared to approximately $4.20 per day for ATD - ISAP III, as of March 2017." |

| 75. |

Information on the FCMP in this section primarily comes from an internal DHS ICE report: Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Family Case Management Program (FCMP) [INTERNAL] Close-Out Report, February 2018 (hereinafter referred to as "ICE, Family Case Management Program (FCMP)") |

| 76. |

The five organizations were Bethany Christian Services in Baltimore/Washington, DC; Frida Kahlo Community Organization in Chicago; International Institute of Los Angeles in Los Angeles; Youth Co-Op, Inc. in Miami; and Catholic Charities of New York in New York City/Newark. |

| 77. |

In addition, ICE piloted two pro bono community-supported release programs during 2013-2015. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) and the Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service (LIRS) provided housing, case management, and legal representation for 100 aliens released from detention. The pilot programs demonstrated the feasibility of ICE working with nongovernmental entities to enhance participant compliance. |

| 78. |

ICE, Family Case Management Program (FCMP). |

| 79. |

The metropolitan areas were Baltimore/Washington, DC; Chicago; Los Angeles; Miami; and New York City/Newark. |

| 80. |

ICE, Family Case Management Program (FCMP). |

| 81. |

While the FCMP report noted a primary vulnerability associated with the household, it does not provide further details of particular issues nor whether families had more than one issue. |

| 82. |

ICE, Family Case Management Program (FCMP), p 6. |

| 83. |

Ibid. |

| 84. |

Ibid. |

| 85. | |

| 86. |

House Appropriations Subcommittee on Homeland Security, and the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Homeland Security. |

| 87. |

P.L. 116-6 was enacted on February 15, 2019. |

| 88. | |

| 89. |

This figure is a gross count of the number of initial book-ins, not the number of unique individuals. See Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, 2018, Fiscal Year 2018 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report, https://www.ice.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Report/2017/iceEndOfYearFY2017.pdf |

| 90. |

DHS response to CRS request, July 12, 2018. |

| 91. |

ICE ERO removal priorities are outlined in Executive Order 13768, "Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States," January 25, 2017, and a related DHS implementation memorandum, "Enforcement of the Immigration Laws to Serve the National Interest," issued February 20, 2017. The memorandum directs DHS personnel to prioritize removable aliens who "(1) have been convicted of any criminal offense; (2) have been charged with any criminal offense that has not been resolved; (3) have committed acts which constitute a chargeable criminal offense; (4) have engaged in fraud or willful misrepresentation in connection with any official matter before a governmental agency; (5) have abused any program related to receipt of public benefits; (6) are subject to a final order of removal but have not complied with their legal obligation to depart the United States; or (7) in the judgment of an immigration officer, otherwise pose a risk to public safety or national security. The Director of ICE, the Commissioner of CBP, and the Director of USCIS may, as they determine is appropriate, issue further guidance to allocate appropriate resources to prioritize enforcement activities within these categories-for example, by prioritizing enforcement activities against removable aliens who are convicted felons or who are involved in gang activity or drug trafficking." |

| 92. |

For further discussion of "recalcitrant" countries, see CRS In Focus IF11025, Immigration: "Recalcitrant" Countries and the Use of Visa Sanctions to Encourage Cooperation with Alien Removals. |

| 93. |

533 U.S. 678 |

| 94. |

ICE email response to CRS request, October 18, 2018. |

| 95. |

ICE email response to CRS request, October 18, 2018. |

| 96. |

GAO, "Alternatives to Detention: Improved Data Collection and Analyses Needed to Better Assess Program Effectiveness," 2014. |

| 97. |

Isaac Stanley-Becker, "Kirstjen Nielsen asserts women and children were 'human shields' in tear gas attack at border," Washington Post, November 26, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2018/11/27/kirstjen-nielsen-claims-women-children-were-human-shields-tear-gas-attack-border/?utm_term=.629f2fb9cc2f . |

| 98. |

Dan Cadman, Why Alien Detention Is Necessary: A Rebuttal to Anti-Detention Advocates, Center for Immigration Studies, 2015, https://cis.org/Report/Why-Alien-Detention-Necessary#10; and Marianne LeVine, "DHS officials tell senators migrants are 'renting babies' to cross the border," Politico Pro, June 6, 2019. |

| 99. |

Nomann Merchant, "Border Patrol expands fingerprinting of migrant children," Associated Press, April 26, 2019. |