Recent Migration to the United States from Central America: Frequently Asked Questions

Over the last decade, migration to the United States from Central America—in particular from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras (known collectively as the Northern Triangle)—has increased considerably. Families migrating from this region, many seeking asylum, have made up an increasing share of the migrants seeking admission to the United States at the U.S.-Mexico border. In the past year, news reports of migrant “caravans” from the Northern Triangle traveling toward the United States have sparked intense interest and questions from Congress.

Many factors, both in their countries of origin and elsewhere, contribute to people’s decisions to emigrate from the Northern Triangle. Weak institutions and corrupt government officials, chronic poverty, rising levels of crime, and demand for illicit drugs result in insecurity and citizens’ low levels of confidence in government institutions. These “push” factors intersect with “pull” factors attracting migrants to the United States, including economic and educational opportunities and a desire to reunify with family members.

Addressing these factors is complex. Under the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America, the United States is working with Central American governments to promote economic prosperity, improve security, and strengthen governance in the region. Since 2014, Mexico has helped the United States manage flows of Central American migrants, including a recent decision to allow certain U.S.-bound asylum seekers to remain in Mexico while awaiting U.S. immigration proceedings. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)—in collaboration with local and federal governments and civil society—is providing immediate and longer-term support for Mexico’s refugee agency and migrants in transit.

Central Americans who wish to request asylum in the United States may do so at a U.S. port of entry before a Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officer or upon apprehension by a CBP officer between U.S. ports of entry. Those requesting asylum at the border undergo screening to determine whether they can pursue an asylum claim. To receive asylum, a foreign national must establish, among other requirements, that he or she is unable or unwilling to return to his or her home country because of past persecution or a well-founded fear of future persecution based on one of five protected grounds (race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion). In 2018, President Trump, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and the Department of Justice (DOJ) took various actions to tighten the U.S. asylum system. These actions have been met with legal challenges. For example, on November 9, 2018, the President issued a presidential proclamation to suspend immediately the entry into the United States of aliens who cross the Southwest border between ports of entry. This proclamation and a related DHS-DOJ rule are being challenged in federal court.

Chapter 15, Title 10 of the U.S. Code provides general legislative authority for the Armed Forces to provide certain types of support to federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies. In October 2018, active-duty personnel were deployed to the Southwest border to provide assistance in air and ground transportation, logistics support, engineering capabilities and equipment, medical support, housing, and planning support. The Posse Comitatus Act constrains the manner in which military personnel may be used in a law enforcement capacity at the border. President Trump has contemplated proclaiming a national emergency pursuant to the National Emergencies Act (NEA) in order to fund a physical barrier at the southern border with Mexico using DOD funds.

Congress provided the President with significant discretion to reduce foreign assistance to Central America in FY2018, dependent on the governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras addressing a variety of congressional concerns, including improving border security, combating corruption, and protecting human rights. The President’s ability to modify assistance to the Northern Triangle for the remainder of FY2019 will depend on provisions Congress may include in future appropriations legislation.

Recent Migration to the United States from Central America: Frequently Asked Questions

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- How do current levels of Central American migrants apprehended at the Southwest border of the United States compare with earlier apprehension levels for Central Americans?

- Why are people leaving the Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras?

- What factors are attracting people from the Northern Triangle to the United States?

- Why do some migrants choose to travel in large groups? Is this a new phenomenon?

- Actions by Governments and International Organizations

- What is the United States doing to address the factors driving migration from the Northern Triangle?

- What results have recent U.S. assistance efforts in the Northern Triangle produced?

- What is Mexico doing to address the flow of Central American migrants through its territory?

- What is the role of the United Nations and other organizations in addressing the humanitarian needs of migrants from the Northern Triangle?

- The Role of U.S. Government Agencies and the Military

- What is the role of U.S. government agencies involved in processing migrants at the Southwest U.S. border?

- How does the United States process unlawful border crossers?

- What is the process for seeking asylum in the United States?

- What did former Attorney General Sessions decide about domestic violence and gang violence as grounds for asylum? What is the status of that decision?

- How does the United States screen for security threats among those seeking entry at the Southwest border?

- What types of missions do military personnel typically perform on the Southwest border?

- How does the Posse Comitatus Act limit the use of military personnel?

- Can the Department of Defense build the border wall?

- The Role of the U.S. President

- What authority does the President have to use military personnel to support border security operations?

- What authority does the President have to cut off aid to the Northern Triangle countries?

- What actions has the President taken to restrict eligibility for asylum?

- Where can more information be found?

Summary

Over the last decade, migration to the United States from Central America—in particular from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras (known collectively as the Northern Triangle)—has increased considerably. Families migrating from this region, many seeking asylum, have made up an increasing share of the migrants seeking admission to the United States at the U.S.-Mexico border. In the past year, news reports of migrant "caravans" from the Northern Triangle traveling toward the United States have sparked intense interest and questions from Congress.

Many factors, both in their countries of origin and elsewhere, contribute to people's decisions to emigrate from the Northern Triangle. Weak institutions and corrupt government officials, chronic poverty, rising levels of crime, and demand for illicit drugs result in insecurity and citizens' low levels of confidence in government institutions. These "push" factors intersect with "pull" factors attracting migrants to the United States, including economic and educational opportunities and a desire to reunify with family members.

Addressing these factors is complex. Under the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America, the United States is working with Central American governments to promote economic prosperity, improve security, and strengthen governance in the region. Since 2014, Mexico has helped the United States manage flows of Central American migrants, including a recent decision to allow certain U.S.-bound asylum seekers to remain in Mexico while awaiting U.S. immigration proceedings. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)—in collaboration with local and federal governments and civil society—is providing immediate and longer-term support for Mexico's refugee agency and migrants in transit.

Central Americans who wish to request asylum in the United States may do so at a U.S. port of entry before a Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officer or upon apprehension by a CBP officer between U.S. ports of entry. Those requesting asylum at the border undergo screening to determine whether they can pursue an asylum claim. To receive asylum, a foreign national must establish, among other requirements, that he or she is unable or unwilling to return to his or her home country because of past persecution or a well-founded fear of future persecution based on one of five protected grounds (race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion). In 2018, President Trump, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and the Department of Justice (DOJ) took various actions to tighten the U.S. asylum system. These actions have been met with legal challenges. For example, on November 9, 2018, the President issued a presidential proclamation to suspend immediately the entry into the United States of aliens who cross the Southwest border between ports of entry. This proclamation and a related DHS-DOJ rule are being challenged in federal court.

Chapter 15, Title 10 of the U.S. Code provides general legislative authority for the Armed Forces to provide certain types of support to federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies. In October 2018, active-duty personnel were deployed to the Southwest border to provide assistance in air and ground transportation, logistics support, engineering capabilities and equipment, medical support, housing, and planning support. The Posse Comitatus Act constrains the manner in which military personnel may be used in a law enforcement capacity at the border. President Trump has contemplated proclaiming a national emergency pursuant to the National Emergencies Act (NEA) in order to fund a physical barrier at the southern border with Mexico using DOD funds.

Congress provided the President with significant discretion to reduce foreign assistance to Central America in FY2018, dependent on the governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras addressing a variety of congressional concerns, including improving border security, combating corruption, and protecting human rights. The President's ability to modify assistance to the Northern Triangle for the remainder of FY2019 will depend on provisions Congress may include in future appropriations legislation.

Introduction

Over the last decade, migration to the United States from Central America—in particular from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras (known collectively as the Northern Triangle)—has increased considerably. From 2006 to 2016, the number of individuals living in the United States who were born in the Northern Triangle grew from 2.2 million to almost 3 million; this increase (37%) was more than twice the increase for the total foreign-born population (16%).1 During the same period, the foreign-born population from Mexico living in the United States held steady at 11.5 million (which is more than any other country-of-birth group). In 2016, the foreign-born population from the Northern Triangle comprised less than 1.0% of the U.S. population and 6.8% of the 43.7 million foreign-born residents of the United States, up from 5.8% in 2006.2

Even though total apprehensions of illegal border crossers were at a 45-year low in FY2017, the number of families from the Northern Triangle apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border has increased in recent years. While earlier migrants apprehended at the Southwest border were predominantly single, adult males from Mexico, currently the majority of apprehended migrants are families and unaccompanied children, and the majority of apprehended migrants come from the Northern Triangle.3 An increasing share of those arriving at the Southwest border are requesting asylum, some at official ports of entry and others after entering the United States "without inspection" (i.e., illegally) between U.S. ports of entry. This is adding to a large backlog of asylum cases in U.S. immigration courts.

In the past year, news reports of migrant "caravans" from the Northern Triangle traveling toward the U.S. border have sparked intense interest and many questions from Congress, including the following: What factors are contributing to the increase in migration from the Northern Triangle to the United States? Is the choice to migrate in large groups a new trend? How are the United States, Mexico, and Central American governments responding? How are U.S. policies at the border—including security screening, removal proceedings, military involvement, and asylum processing—being implemented? This report addresses these and other frequently asked questions.

|

Key Terms Migrant, in general, is a person who has temporarily or permanently crossed an international border, is no longer residing in his or her country of origin or habitual residence, and is not recognized as a refugee. As used in this report, migrants may include asylum seekers. Refugee, as used in this report and as defined in U.S. and international law,4 is a person who has fled his or her country of origin or habitual residence because of a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. Refugees are unwilling or unable to avail themselves of the protection of their home governments due to fears of persecution. Asylum-seeker, as used in this report, is a person who has fled his or her home country and seeks sanctuary in another country, where the person applies for asylum (i.e., the right to be recognized as a refugee). Alien, as used in this report and as defined in U.S. law,5 is a person who is not a citizen or national of the United States. It is synonymous with foreign national. Unauthorized alien, as used in this report, is an alien who lacks a lawful immigration status. Unaccompanied alien children (UAC), as used in this report and as defined in U.S. law,6 are children who lack lawful immigration status, are under age 18, and are either without a parent or legal guardian in the United States or without a parent or legal guardian in the United States who is available to provide care and physical custody. |

How do current levels of Central American migrants apprehended at the Southwest border of the United States compare with earlier apprehension levels for Central Americans?7

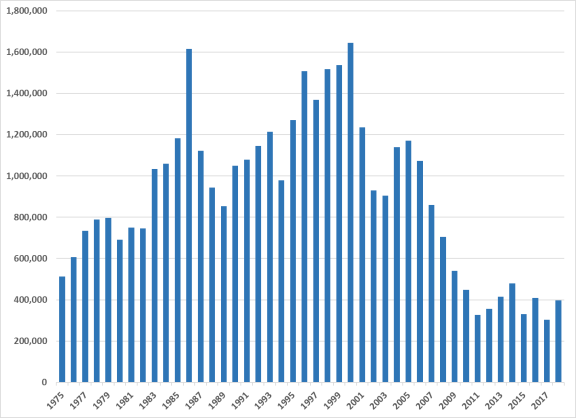

The increase in the number of Central American migrants apprehended at the Southwest border is occurring within the context of historically low levels of total alien apprehensions (see Figure 1). Apprehensions of migrants of all nationalities increased consistently beginning in 1960, fluctuated between two peaks of 1.62 million in FY1986 and 1.64 million in FY2000, and then declined to a 45-year low of approximately 304,000 in FY2017. Apprehensions increased in FY2018 to 397,000, which was comparable to the annual Southwest border average (401,000) for the most recent 10-year period (FY2009-FY2018).

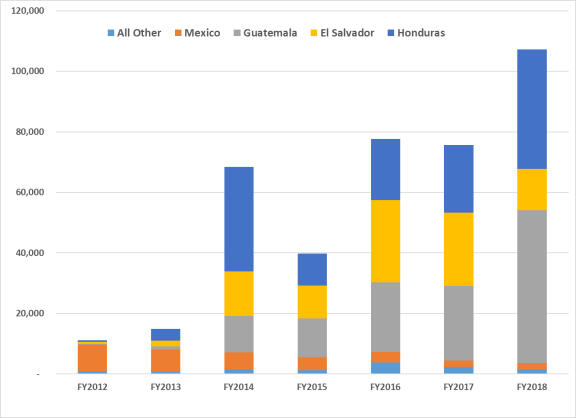

Two demographic shifts, illustrated in the apprehension data, characterize recent migrant flows. First, over the past two decades the national origins of apprehended aliens have changed. In FY2000, almost all Southwest border apprehensions (98%) were of Mexican nationals.8 Beginning in FY2012, however, the percentage of apprehended aliens from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador started to increase as a share of total apprehensions. By FY2018, foreign nationals from those three countries made up 52% of all apprehensions.9 Second, the type of migrants apprehended has also shifted. In the past, single adult males made up over 90% of apprehended aliens.10 Currently, the majority of apprehended migrants are families and unaccompanied children.11 From FY2012 to FY2018, the predominant national origins of such families changed from Mexico to the Northern Triangle countries (see Figure 2). (For more information, see CRS Report R45266, The Trump Administration's "Zero Tolerance" Immigration Enforcement Policy.)

|

Figure 1. Total Apprehensions at the Southwest Border by U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, FY1975-FY2018 |

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Border Patrol, "Stats and Summaries," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/media-resources/stats. |

|

Figure 2. Total Family Unit Apprehensions at the Southwest Border by U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, FY2012-FY2018 |

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Border Patrol, "Stats and Summaries," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/media-resources/stats. |

Why are people leaving the Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras?12

Many factors—including those in their countries of origin, destination countries (often the United States), and other countries—contribute to people's decisions to emigrate from the Northern Triangle.

Drivers of migration are interrelated, often reinforcing one another. Over time, weak institutions and corrupt government officials, economic growth that does not significantly reduce chronic poverty, rising levels of crime, and demand for illicit drugs result in insecurity and citizens' low levels of confidence in government institutions. These in turn contribute to an increased desire to leave a country.13

The Northern Triangle countries have long histories of autocratic rule, weak institutions, and corruption.14 A lack of political will and capacity, rampant bribery and embezzlement of state funds, and some of the lowest tax collection rates in Latin America divert and diminish resources, leaving state institutions and programs underfunded.15 These problems also limit the governments' abilities to respond to crises such as natural disasters and food insecurity. All of these factors help perpetuate chronic poverty. While often cited as a leading cause of emigration from the Northern Triangle, poverty alone does not explain it.

Over the past decade, transnational criminal organizations have used the Central American corridor for a range of illicit activities, including trafficking approximately 90% of cocaine bound for the United States.16 As a result, Northern Triangle countries have experienced extremely elevated homicide rates and general crime committed by drug traffickers, gangs, and other criminal groups. For instance, clashes between street gangs and, in El Salvador, between gangs and security forces, have paralyzed cities and some rural areas.17 A recent study found that the probability that an individual intends to migrate is 10-15 percentage points higher for Salvadorans and Hondurans who have been victims of multiple crimes than for those who have not.18

Finally, Central America has always been particularly subject to climate variability. According to the World Risk Index, Guatemala and El Salvador are among the 15 countries in the world most exposed to natural disasters, especially earthquakes and droughts.19 About one-fourth of those employed in the Northern Triangle work in the agriculture sector;20 widespread crop failures can have a devastating impact on people's livelihoods and ability to feed their families. According to the 2018 Global Hunger Index, Guatemala and Honduras ranked second and third in hunger levels in Central America and the Caribbean, behind Haiti.21 Research indicates that more intense and erratic weather patterns in recent years are strongly linked to food insecurity and migration.22

(For more information, see CRS Report R44812, U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America: Policy Issues for Congress; CRS Report RL34027, Honduras: Background and U.S. Relations; CRS Report R43616, El Salvador: Background and U.S. Relations; CRS Report R42580, Guatemala: Political and Socioeconomic Conditions and U.S. Relations; and CRS Report RL34112, Gangs in Central America.)

What factors are attracting people from the Northern Triangle to the United States?23

The factors discussed above intersect with factors attracting migrants to the United States. Economic opportunity may motivate Northern Triangle families and unaccompanied children to migrate. Despite challenging labor market conditions for low-skilled minority youth in the United States, economic prospects for industrial sectors employing low-skilled workers have improved recently. Educational opportunities may also be a motivating factor in migration, as perceptions of free public education through high school may be widespread among young migrants.

Family reunification is a key motive, as many migrants have family members among the sizable Salvadoran, Guatemalan, and Honduran foreign-born populations residing in the United States.24 While the impacts of actual and perceived U.S. immigration policies have been widely debated, it remains unclear if, and how, specific immigration policies have motivated families and children to migrate to the United States. Some contend that the United States' asylum policy, which allows asylum seekers to remain in the United States while they await a decision on their cases, has encouraged recent family and unaccompanied child migration to the country. Currently, immigration courts face a backlog of over 700,000 asylum cases, resulting in wait times of months or years, and a substantial portion of asylum seekers fail to appear in court.25 Others have argued that the revised humanitarian relief policies for unaccompanied children included in the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA) of 2008, which expanded immigration relief options for such children, fostered a similar result among this migrant population. (For more information, see archived CRS Report R43628, Unaccompanied Alien Children: Potential Factors Contributing to Recent Immigration.)

Why do some migrants choose to travel in large groups? Is this a new phenomenon?26

Migrants from the Northern Triangle traveling to the United States customarily have used various means to get to the Mexico-U.S. border, including walking, hitchhiking, riding on the top of trains through Mexico, and riding buses, all with or without the assistance of smugglers. Central American migrants have joined into groups to make the journey together as a way to share resources, avoid the cost of smugglers, and gain protection by the safety offered in numbers.27 "Caravans" have reportedly occurred for a least a decade,28 but they received little attention until last spring when a group of roughly 1,000 Central American migrants headed to the United States. About 400 migrants eventually made it to the U.S. border.29

In past years, ad hoc processions have been loosely organized by nonprofit groups wanting to call attention to the plight of migrants in their home communities, particularly those of families with children fleeing unsafe environments, poverty, and lack of protection from gang violence and extortion.30 Mobile phone technology has facilitated navigation and affords communication with impromptu groups, resulting in migrations that can expand and contract along the way.

Actions by Governments and International Organizations

What is the United States doing to address the factors driving migration from the Northern Triangle?31

Under the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America, the United States is working with Central American governments to promote economic prosperity, improve security, and strengthen governance in the region. The Obama Administration launched the strategy following a surge in apprehensions of unaccompanied alien children in 2014, and the Trump Administration largely has left the strategy in place. Congress appropriated an estimated $2.1 billion to support the strategy from FY2016-FY2018, roughly doubling annual aid levels for the region.32 The governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras are carrying out complementary efforts under their Plan of the Alliance for Prosperity in the Northern Triangle. They collectively allocated an estimated $7.7 billion to the initiative from 2016-2018,33 though some analysts have questioned whether those funds have been targeted effectively.34

On December 18, 2018, the Trump Administration committed to providing $5.8 billion in public and private investment to support institutional reforms and development in the Northern Triangle.35 Nearly all of the foreign assistance included in that figure was appropriated in prior years and the remainder consists of potential loans, loan guarantees, and private sector resources that the U.S. Overseas Private Investment Corporation could mobilize if it is able to identify commercially viable projects. (For more information, see CRS Report R44812, U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America: Policy Issues for Congress.)

What results have recent U.S. assistance efforts in the Northern Triangle produced?36

It is too early to assess the full impact of recent U.S. efforts because implementation did not begin until 2017 for many of the programs funded under the U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America.37 Nevertheless, the Northern Triangle countries, with U.S. support, have made some tentative progress. For example, they have implemented some policy changes that have contributed to economic stability. At the same time, living conditions have yet to improve for many residents because the Northern Triangle governments have not invested in effective poverty-reduction programs.38 Security conditions also have improved in some respects, as homicide rates have declined for three consecutive years.39 Still, many Northern Triangle residents continue to feel insecure, and the percentage of individuals reporting they were victims of crime increased in all three nations between 2014 and 2017.40 The countries' attorneys general—with the support of the U.N.-backed International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala and the Organization of American States-backed Mission to Support the Fight against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras—have made significant progress in the investigation and prosecution of high-level corruption cases. Those efforts could be undermined, however, as they have received considerable pushback from political and economic elites in the region.41 (For more information, see CRS Report R44812, U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America: Policy Issues for Congress.)

What is Mexico doing to address the flow of Central American migrants through its territory?42

Since a surge of unaccompanied child migrants from the Northern Triangle transited Mexico to the United States in 2014, Mexico has helped the United States manage flows of Central American migrants and has received more than $100 million in U.S. funding for those efforts.43 From 2015 through 2018, Mexico returned almost 524,000 migrants who entered it from the Northern Triangle countries.44 At the same time, Mexico has provided temporary visas for those who want to work in its southern border states, as well as humanitarian visas and access to asylum for those who do not raise criminal or terrorist concerns when their biometric information is run against U.S. databases. President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has thus far been willing to shelter some U.S.-bound Central American migrants, but he urged the U.S. government to invest in southern Mexico and Central America to prevent future unauthorized migration. On December 18, 2018, the two governments made a joint announcement in support of economic development in Mexico and the Northern Triangle.45

The Mexican government has faced pressure from the United States to help contain and disperse recent caravans of Central American migrants transiting the country; humanitarian groups, by contrast, have urged it to assist the migrants. In fall 2018, Mexican citizens, aid groups, and local, state, and federal entities provided migrants with food, shelter, and emergency aid. As of early December 2018, the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported that 3,300 members of migrant caravans had applied for asylum in Mexico.46 At the same time, more than 3,000 people had accepted voluntary repatriation to their countries of origin. With U.S. ports of entry limiting the number of migrants accepted each day for asylum screening, border cities may have to shelter thousands of migrants for many months.47 Mexico's refugee agency, which has received support from UNHCR (discussed below), was overwhelmed processing record numbers of applications prior to the arrival of recent migrant caravans.

In late 2018, the U.S. and Mexican governments were negotiating an agreement—dubbed "Remain in Mexico"—that would have required U.S.-bound asylum seekers who could not demonstrate that they faced imminent danger in Mexico to remain there as their U.S. asylum claims were processed.48 Prior to the conclusion of a final bilateral agreement, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) notified Mexico that it would implement a new policy under Section 235(b)(2)(C) of the Immigration and Nationality Act to return some non-Mexican asylum seekers (excluding unaccompanied minors) to Mexico to await their immigration court decisions.49 Mexico responded with a statement declaring that it has the right to admit or reject foreigners arriving in its territory, and that it would provide humanitarian visas and work permits to certain non-Mexicans awaiting U.S. immigration proceedings and offer some individuals the ability to apply for asylum in Mexico.50 Mexico reportedly began implementing this policy in mid-January,51 and the United States returned the first asylum seeker to Mexico under its new policy—dubbed the "Migrant Protection Protocols"—on January 29, 2019.52 Mexican officials have reportedly stated that they will not accept minors or individuals over age 60 awaiting asylum claims.53 Concerns over the costs to local governments of sheltering migrants and the safety of migrants could make this policy difficult to maintain.54 (For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10215, Mexico's Immigration Control Efforts.)

What is the role of the United Nations and other organizations in addressing the humanitarian needs of migrants from the Northern Triangle?55

A range of organizations provide humanitarian assistance to people traveling from the Northern Triangle toward the United States, including U.N. entities and other intergovernmental organizations, local and national non-governmental organizations, and the private sector.56 According to UNHCR—a key U.N. entity operating in the region—comprehensive assistance is needed at all phases of the journey, including food, medical care, shelter, protection, and, in many cases, legal support.57

Experts characterize this flow of people from the Northern Triangle as mixed migration, defined as different groups—such as economic migrants, refugees, asylum-seekers, trafficked persons, and unaccompanied children—who travel the same routes and use the same modes of transportation. The distinctions between groups in mixed migration flows raise questions about their status and rights. While refugees are granted certain rights and protection under international refugee law, migrants are not protected by a comparable set of rules or treaties. Nevertheless, UNHCR asserts that transit and destination countries should provide all of these groups access to humanitarian assistance, protection, and due process to assess their asylum claims, even if they do not qualify as refugees. Those who flee are often unsafe not only in their home countries, but also during their journey north where they face recruitment into criminal gangs, sexual and gender-based violence, and murder.58 Many are vulnerable, including women, children, the elderly, and those with disabilities.59

In Mexico, UNHCR provides immediate and longer-term support by working with local and federal governments and alongside civil society and other partners.60 In addition to shelter and cash-based humanitarian assistance, broader safety mechanisms include improved screening procedures and dissemination of information for those fleeing violence, increased ways to guard against smugglers and traffickers, and enhanced access to the Mexican asylum system.61 Even with additional support from UNHCR, Mexico's Commission for the Aid of Refugees (COMAR) lacks sufficient capacity to process claims.62 UNHCR and other organizations are also being mobilized along the caravan routes in places such as Chiapas, Oaxaca, and Tijuana.63

International humanitarian efforts aim to align with the Comprehensive Regional Protection and Solutions Framework, an intergovernmental agreement that defends the rights of migrants and refugees who live in or cross the territories of Belize, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and Panama.64 In general, most Latin American and Caribbean countries are part of an ongoing forum to address issues driving displacement such as poverty, economic decline, inflation, violence, disease, and food insecurity.65 In the current situation, U.N. and other experts urge donors to provide timely and predictable international funding to support host governments and local communities that are assisting arrivals.66

The Role of U.S. Government Agencies and the Military

What is the role of U.S. government agencies involved in processing migrants at the Southwest U.S. border?67

Several federal agencies are involved in immigration processing at land, air, and sea ports of entry and along U.S. borders shared with Mexico and Canada. The following descriptions are not exhaustive of all the duties carried out by each entity; they are a selection of duties relevant to immigration enforcement at the Southwest border at and between land ports of entry.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) includes several relevant components:

Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is responsible for facilitating lawful trade and travel while preventing unauthorized people and contraband from entering the country. Within CBP, U.S. Border Patrol is the law enforcement agency that secures U.S. borders at and between ports of entry; Border Patrol agents apprehend and hold foreign nationals who have no valid entry documents when they reach ports of entry or who attempt to cross between ports of entry. CBP's Office of Field Operations (OFO) operates U.S. ports of entry and conducts immigration inspections of arriving foreign nationals to determine their admissibility to the United States.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) is responsible for protecting the country from cross-border crime and illegal immigration that threatens national security and public safety. ICE's Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) enforces immigration laws pertaining to the detention and removal of unauthorized aliens and oversees detention centers, including family detention centers. ICE also finds and removes deportable aliens located in the U.S. interior.

United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) is responsible for adjudication of immigration and naturalization petitions, consideration of refugee and asylum claims and related humanitarian and international concerns, and other services, such as issuing employment authorizations and processing nonimmigrant change-of-status petitions. At the border, USCIS asylum officers interview foreign nationals who arrive without admissions documents at a port of entry or who encounter a Border Patrol agent and express a fear of return to their home countries based on persecution. If migrants are found to have "credible fear," they are referred to an immigration judge for a hearing.

The Department of Justice (DOJ) runs the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), the federal government's immigration courts. Immigration judges determine whether an alien is removable or is eligible for some type of immigration relief during the removal process (e.g., asylum or withholding of removal). The standard removal process is a civil administrative proceeding involving a DHS attorney and an EOIR immigration judge to determine whether an alien should be removed. (For more information, see CRS Report R43892, Alien Removals and Returns: Overview and Trends.)

The Department of Health and Human Services' (HHS') Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) is responsible for the care of unaccompanied alien children (UAC) and their subsequent placement in appropriate custody. ICE handles custody transfer or repatriation. (For more information, see archived CRS Report R43599, Unaccompanied Alien Children: An Overview.)

How does the United States process unlawful border crossers?68

Aliens apprehended for illegally entering the United States between U.S. ports of entry generally face civil penalties for illegal presence in the United States and may face criminal penalties for illegal entry. Aliens who have been removed face additional criminal penalties if they are apprehended for illegal reentry. Aliens apprehended for illegal entry and reentry are subject to prosecution in federal criminal courts by DOJ.

All apprehended aliens, including children, are placed into one of two types of immigration removal proceedings: standard proceedings that involve formal hearings in an immigration court run by DOJ's EOIR before an immigration judge, or streamlined "expedited removal" proceedings without such hearings. ICE is responsible for legally representing the government during removal proceedings. CBP may refer aliens to DOJ for criminal prosecution depending on whether they meet current criminal enforcement priorities. If CBP does not refer apprehended aliens to DOJ for criminal prosecution, CBP may either return them to their home countries using expedited removal or transfer them to ICE custody for immigration detention while they are in formal removal proceedings. (For more information, see CRS Report R45314, Expedited Removal of Aliens: Legal Framework.)

Aliens who wish to request asylum may do so at a U.S. port of entry before a CBP officer or upon apprehension by a CBP officer between U.S. ports of entry. Aliens requesting asylum at the border are entitled to an interview assessing the credibility of their asylum claims. (For more information, see "What is the process for seeking asylum in the United States?" below.)

During the brief period when the Trump Administration's "zero tolerance" policy was in effect (May and June 2018), DOJ sought the prosecution of all adults caught entering illegally, including asylum seekers and adults accompanied by children. On June 20, 2018, following considerable and largely negative public attention to family separations stemming from the zero tolerance policy, President Trump issued an executive order (EO) effectively ending the policy. While it was in effect, DHS classified all children accompanying criminally prosecuted adults as UAC and turned them over to HHS' ORR, where they were housed temporarily in its shelters. After the prosecuted adults served any applicable criminal sentence, they were transferred to ICE custody, placed in immigration detention, and eventually, in most cases, reunited with their children, either in family detention or upon release into the United States on bond, an order of supervision, or another condition of release. Other parents were deported before they were reunited with their children, and a small number of parents still in the United States remain separated from their children. (For more information, see CRS Report R45266, The Trump Administration's "Zero Tolerance" Immigration Enforcement Policy.)

What is the process for seeking asylum in the United States?69

The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) provides, subject to certain exceptions and restrictions, that aliens who are in the United States or who arrive in the United States (whether or not at an official port of entry) may apply for asylum, regardless of their immigration status. Asylum may be granted by a USCIS asylum officer or a DOJ EOIR immigration judge. To receive asylum, an alien must establish, among other requirements, that he or she is unable or unwilling to return to his or her home country because of past persecution or a well-founded fear of future persecution based on one of five protected grounds (race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion). Certain aliens, such as those who are determined to pose a danger to U.S. security, are ineligible to receive asylum.

Special asylum provisions apply to aliens who are subject to a streamlined removal process known as expedited removal. In order for such an alien to be considered for asylum, a USCIS asylum officer first must determine that the alien has a credible fear of persecution. (For more information, see CRS Report R45314, Expedited Removal of Aliens: Legal Framework.)

What did former Attorney General Sessions decide about domestic violence and gang violence as grounds for asylum? What is the status of that decision?70

In June 2018, the Attorney General, whose decisions are binding on DHS officers and immigration judges, issued a decision regarding the adjudication of asylum claims based on "membership in a particular social group." In the decision, Attorney General Sessions stated that "[g]enerally, claims by aliens pertaining to domestic violence or gang violence perpetrated by non-governmental actors will not qualify for asylum" based on the "membership in a particular social group" ground. He further noted that because such claims would not generally qualify for asylum, they also would not generally meet the threshold for a finding of a credible fear of persecution.71 USCIS subsequently issued a policy memorandum to provide guidance to its asylum officers in light of the Attorney General's decision. The memorandum included guidance on determining whether an alien is eligible for asylum as well as whether an alien has a credible fear of persecution and thus can pursue an asylum claim.72

The new policies regarding credible fear of persecution determinations were challenged in federal court. In December 2018, a federal district court judge permanently enjoined the U.S. government from continuing some of the new credible fear policies.73 Other components of the former Attorney General's decision and the USCIS memorandum, including standards for adjudicating asylum claims, remain in effect. (For more information, CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10207, Asylum and Related Protections for Aliens Who Fear Gang and Domestic Violence.)

How does the United States screen for security threats among those seeking entry at the Southwest border?74

TECS (not an acronym) is the main system that CBP officers employ at the border and elsewhere to screen arriving travelers and determine their admissibility. CBP also uses the Automated Targeting System (ATS), which is a decision support tool. As one of its functions, ATS "compares information about travelers and cargo arriving in, transiting through, or exiting the country, against law enforcement and intelligence databases," including information from the Terrorist Screening Databased (TSDB, commonly referred to as the terrorist watchlist).75 As its name suggests, Automated Targeting System-Passenger (ATS-P) is the portion of ATS focused on passengers, "for the identification of potential terrorists, transnational criminals, and, in some cases, other persons who pose a higher risk of violating U.S. law"76 and is used by CBP personnel at the border, ports of entry, and elsewhere, including screening the passenger manifests of all U.S. bound international flights.77 (For more information, see CRS Report R44678, The Terrorist Screening Database and Preventing Terrorist Travel.)

What types of missions do military personnel typically perform on the Southwest border?78

Active duty and National Guard personnel have performed a variety of missions on the Southwest border in the past, including ground and aerial surveillance, road and fencing construction, intelligence analysis, transportation, maintenance, and communications support. According to a DOD news release, the National Guard personnel who deployed to the border in April 2018 would provide "surveillance, engineering, administrative and mechanical support to border agents."79

A subsequent DOD news release announcing the deployment of active duty personnel in October 2018 stated that CBP "requested aid in air and ground transportation, and logistics support, to move CBP personnel where needed. Officials also asked for engineering capabilities and equipment to secure legal crossings, and medical support units. CBP also asked for housing for deployed Border Protection personnel and extensive planning support."80

The Trump Administration issued a memo on November 20, 2018, which authorized military personnel to perform

those military protective activities that the Secretary of Defense determines are reasonably necessary to ensure the protection of Federal personnel, including a show or use of force (including lethal force, where necessary), crowd control, temporary detention and cursory search. Department of Defense personnel shall not, without further direction from the President, conduct traditional civilian law enforcement activities, such as arrest, search, and seizure in connection with the enforcement of the laws.81

During a discussion with reporters on November 21, 2018, Secretary of Defense James Mattis responded to questions about the potential use of military personnel in a law enforcement role:

The one point I want to make again is we are not doing law enforcement. We do not have arrest authority. Now the governors could give their troops arrest authority. I don't think they've done that, but there are—is no arrest authority under Posse Comitatus for the U.S. federal troops. You know, that can be done but it has to be done in accordance with the law, and that has not been done nor has it been anticipated.82

Later in the interview he stated

On detention, we do not have arrest authority. Detention would—I would put it in terms of minutes. In other words, if someone's beating on a Border Patrolman and if we were in position to have to do something about it, we could stop them from beating on them and take him over and deliver him to a Border Patrolman, who would then arrest him for it…. There's no violation of Posse Comitatus, there's no violation here at all. We're not going to arrest or anything else. To stop someone from beating on someone and turn them over to someone else—this is minutes not even hours, okay?83

According to a January 14 news release from DOD, Acting Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan approved continued DOD assistance to DHS through September 30, 2019. It also noted that "DOD is transitioning its support at the southwestern border from hardening ports of entry to mobile surveillance and detection, as well as concertina wire emplacement between ports of entry. DOD will continue to provide aviation support."84

How does the Posse Comitatus Act limit the use of military personnel?85

The Posse Comitatus Act constrains how military personnel may be used in a law enforcement capacity at the border. The Posse Comitatus Act is a criminal prohibition that provides

Whoever, except in cases and under circumstances expressly authorized by the Constitution or Act of Congress, willfully uses any part of the Army or the Air Force as a posse comitatus or otherwise to execute the laws shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than two years, or both.86

Consequently, there must be a constitutional or statutory authority to use federal troops in a law enforcement capacity to enforce immigration or customs laws directly by, for example, stopping aliens from entering the country unlawfully, apprehending gang members, or seizing contraband. As noted in a section below, federal law permits the Armed Forces to act in a supporting role for civil authorities by providing logistics or operating and maintaining equipment, among other things.

Case law suggests that the Posse Comitatus Act is violated when (1) civilian law enforcement officials make a direct active use of military personnel to execute the law; (2) the use of the military pervades the activities of the civilian officials; or (3) the military is used so as to subject persons to the exercise of military power which is regulatory, prescriptive, or compulsory in nature. The Posse Comitatus Act does not apply to the National Guard unless it is activated for federal service.

One possible statutory exception the President could potentially invoke for direct military enforcement is the Insurrection Act provision for sending troops whenever he determines that "unlawful obstructions, combinations, or assemblages, or rebellion against the authority of the United States, make it impracticable to enforce the laws of the United States … by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings."87 However, the Insurrection Act appears never to have been invoked to respond to unlawful migrant border crossings, and its application in such a situation has not been tested in court.

The executive branch has long asserted two constitutional exceptions to the Posse Comitatus Act "based upon the inherent legal right of the U.S. Government … to insure the preservation of public order and the carrying out of governmental operations within its territorial limits, by force if necessary."88 These exceptions include the emergency authority "to prevent loss of life or wanton destruction of property and to restore governmental functioning and public order when sudden and unexpected civil disturbances, disasters, or calamities seriously endanger life and property and disrupt normal governmental functions to such an extent that duly constituted local authorities are unable to control the situation"; and the authority to "protect Federal property and Federal governmental functions when the need for protection exists and duly constituted local authorities are unable or decline to provide adequate protection."89 (For more information, see CRS Report R42659, The Posse Comitatus Act and Related Matters: The Use of the Military to Execute Civilian Law.)

Can the Department of Defense build the border wall?90

President Trump has contemplated proclaiming a national emergency91 pursuant to the National Emergencies Act (NEA)92 in order to fund a physical barrier at the southern border with Mexico using DOD funds. Declaring a national emergency could permit the President to invoke two statutes that could potentially permit either the use of unobligated military construction funds93 or the reprogramming of Army Corps of Engineers civil works funds.94

Military Construction Funds. Upon declaring a national emergency pursuant to the NEA, the President may invoke the emergency military construction authority in 10 U.S.C. §2808. Originally enacted in 1982, Section 2808 provides that upon the President's declaration of a national emergency "that requires use of the armed forces," the Secretary of Defense may "without regard to any other provision of law ... undertake military construction projects ... not otherwise authorized by law that are necessary to support such use of the armed forces." Section 2808 limits the funds available for emergency military construction to "the total amount of funds that have been appropriated for military construction" that have not been obligated. With certain limited exceptions, Presidents have generally invoked this authority in connection with construction at military bases in foreign countries.

The circumstances in which the Section 2808 authority could be used to deploy barriers along the border appears to be a question of first impression, and one that is likely to be vigorously litigated. It appears that three interpretive questions could impede such use. First, there may be dispute about whether conditions at the border provide a sufficient factual basis to invoke Section 2808. Before the Section 2808 authority may be used, the President must determine that the relevant construction project would address a problem qualifying as a national emergency "that requires use of the armed forces." Moreover, the construction project must be "necessary to support such use of the armed forces." Second, if the above criteria are met, then an assessment would be necessary to determine whether construction of a border wall qualifies as a "military construction project" within the meaning of Section 2808. Title 10 defines the term "military construction project" for purposes of Section 2808 to include "military construction work," and defines "military construction" as "includ[ing] any construction, development, conversion, or extension of any kind carried out with respect to a military installation ... or any acquisition of land or construction of a defense access road."95 Because there does not appear to be case law addressing the scope of this definition of "military construction," the question of whether Section 2808 extends to the construction of a border wall appears to be an issue of first impression. Third, if a court were to review the invocation of Section 2808 to construct a border wall, its analysis might be informed by the location of particular barriers. It is possible that a border wall will be "necessary to support such use of the armed forces" at some locations but not others. Likewise, the construction of a wall over certain areas of the border—specifically, areas that directly abut military bases—would appear to have a greater claim to qualifying as construction undertaken "with respect to a military installation" than construction at other locations along the border.

Army Corps of Engineers Funds. Section 2293 of Title 33, U.S. Code, authorizes the Secretary of the Army to terminate or defer Army civil works projects that are "not essential to the national defense" upon a declaration of a national emergency under the NEA "that requires or may require the use of the Armed Forces." The Secretary of the Army can then use the funds otherwise allocated to those projects for "authorized civil works, military construction, and civil defense projects that are essential to the national defense." As with Section 2808, it is unsettled whether the construction of a border wall would qualify as an "authorized civil works, military construction, [or] civil defense project[]." This uncertainty is compounded by the difficulty of determining whether the qualifier "authorized" modifies all of the items enumerated in Section 2293 or only the term "civil works." If the term "authorized" modifies all of the items in the relevant sentence, then Section 2293 arguably would not allow the President to construct a border wall if that term is read to mean specifically authorized by Congress.

Courts have traditionally afforded significant deference to executive claims of military necessity, deference which may stand as a substantial obstacle to legal challenges to any factual findings supporting the invocation of either Section 2808 or Section 2293. (For more information, see CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10242, Can the Department of Defense Build the Border Wall?)

The Role of the U.S. President

What authority does the President have to use military personnel to support border security operations?96

The President's authority to use military personnel to support border security operations depends on whether those personnel are active duty troops serving under Title 10, U.S. Code, or National Guard troops operating under Title 32, U.S. Code.97 Section 502 of Title 32, U.S. Code, provides the authority for the Secretary of the Army and the Secretary of the Air Force to call National Guard units to full-time duty under Title 32 status for training "or other duty in addition to" mandatory training. Section 502(f) "other duty" may include "homeland defense activities."98 Such activities are defined to mean activities:

undertaken for the military protection of the territory or domestic population of the United States, or of infrastructure or other assets of the United States determined by the Secretary of Defense as being critical to national security, from a threat or aggression against the United States.99

Chapter 15 of Title 10, U.S. Code—Military Support for Civilian Law Enforcement Agencies—provides general legislative authority for the Armed Forces to provide certain types of support to federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies, particularly in counterdrug, counterterrorism, and counter-transnational crime efforts.100 Such authorities permit the military to provide certain types of support for border security and immigration control operations. These authorities permit DOD to share information collected during the normal course of military operations,101 loan equipment and facilities,102 provide expert advice and training,103 and maintain and operate equipment.104

To assist federal law enforcement agencies, military personnel may maintain and operate equipment in conjunction with counterterrorism operations or the enforcement of counterdrug laws, immigration laws, and customs requirements.105 To assist federal law enforcement agencies in counter drug operations, military personnel may, among other things, engage in the "[c]onstruction of roads and fences and installation of lighting to block drug smuggling corridors across international boundaries of the United States."106 Chapter 15 support authority "does not include or permit direct participation by a member of the Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps in a search, seizure, arrest, or other similar activity unless participation in such activity by such member is otherwise authorized by law."107

One other possible source of authority is Section 1059 of the National Defense Authorization Act of 2016.108 That provision authorized the Secretary of Defense, with the concurrence of the Secretary of Homeland Security, to spend up to $75 million of 2016 DOD funds to provide assistance to CBP "for purposes of increasing ongoing efforts to secure the southern land border of the United States."109 The types of assistance permitted include "deployment of members and units of the regular and reserve components of the Armed Forces to the southern land border of the United States" along with "manned aircraft, unmanned aerial surveillance systems, and ground-based surveillance systems to support continuous surveillance of the southern land border of the United States" and "[i]ntelligence analysis support."110 (For more information, see CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10121, The President's Authority to Use the National Guard or the Armed Forces to Secure the Border.)

What authority does the President have to cut off aid to the Northern Triangle countries?111

Congress provided the President with significant discretion to reduce foreign assistance to Central America in FY2018. In the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141), Congress designated "up to" $615 million for the Central America strategy, effectively placing a ceiling on aid but no floor. The act also requires the State Department to withhold 75% of assistance for the central governments of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras until the Secretary of State certifies that those governments are addressing a variety of congressional concerns, including improving border security, combating corruption, and protecting human rights. The act empowers the Secretary of State to suspend and reprogram aid if he determines the governments have made "insufficient progress" in addressing the legislative requirements. The President's ability to modify assistance to the Northern Triangle countries for FY2019 will depend on provisions Congress may include in future appropriations legislation.

What actions has the President taken to restrict eligibility for asylum?112

Citing constitutional and statutory authority, the President issued a presidential proclamation on November 9, 2018, to immediately suspend the entry into the United States of aliens who cross the Southwest border between ports of entry. The proclamation indicates that its entry suspension provisions will expire 90 days after its issuance date or on the date that the United States and Mexico reach a bilateral agreement that allows for the removal of asylum seekers to Mexico, whichever is earlier. Also on November 9, 2018, DHS and DOJ jointly issued an interim final rule to bar an alien who enters the United States in contravention of the proclamation from eligibility for asylum. Under the rule, an asylum officer is to make a negative credible fear determination in the case of such an alien. (For more information, see CRS Insight IN10993, Presidential Proclamation on Unlawful Border Crossers and Asylum.)

The proclamation and the rule are being challenged in federal court. As of the date of this report, the changes to the asylum process set forth in the rule are not in effect. (For more information, see CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10222, District Court Temporarily Blocks Implementation of Asylum Restrictions on Unlawful Entrants at the Southern Border.)

Where can more information be found?

For more information on relevant topics and issues Congress may consider, see the following reports or contact the authors:

CRS Report R44812, U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America: Policy Issues for Congress, by Peter J. Meyer

CRS Report R45120, Latin America and the Caribbean: Issues in the 115th Congress, coordinated by Mark P. Sullivan (see "Migration Issues" section)

CRS In Focus IF10215, Mexico's Immigration Control Efforts, by Clare Ribando Seelke and Carla Y. Davis-Castro

CRS Report R43616, El Salvador: Background and U.S. Relations, by Clare Ribando Seelke

CRS Report RL34027, Honduras: Background and U.S. Relations, by Peter J. Meyer

CRS Report R42580, Guatemala: Political and Socioeconomic Conditions and U.S. Relations, by Maureen Taft-Morales

CRS Report R45266, The Trump Administration's "Zero Tolerance" Immigration Enforcement Policy, by William A. Kandel

CRS Insight IN10993, Presidential Proclamation on Unlawful Border Crossers and Asylum, by Andorra Bruno

CRS Report RS20844, Temporary Protected Status: Overview and Current Issues, by Jill H. Wilson

CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10150, An Overview of U.S. Immigration Laws Regulating the Admission and Exclusion of Aliens at the Border, by Hillel R. Smith

CRS Report R42138, Border Security: Immigration Enforcement Between Ports of Entry, coordinated by Audrey Singer

CRS Report R43356, Border Security: Immigration Inspections at Ports of Entry, by Audrey Singer

CRS Report R43599, Unaccompanied Alien Children: An Overview, by William A. Kandel

CRS Legal Sidebar LSB10121, The President's Authority to Use the National Guard or the Armed Forces to Secure the Border, by Jennifer K. Elsea

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

The "foreign-born population" refers to people living in the United States who were not U.S. citizens at birth, regardless of their current immigration status. U.S.-born children are not included. The foreign-born population from the Northern Triangle counts those born in El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala. |

| 2. |

The numbers in this paragraph come from the Census Bureau's 2016 American Community Survey. |

| 3. |

Testimony of Kevin McAleenan, Commissioner, U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, in U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Customs and Border Protection Oversight, 115th Cong., 2nd sess., December 11, 2018. |

| 4. |

8 U.S.C. §1101(a)(42); Article 1 of the United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, as revised by Article 1 of the United Nations Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. |

| 5. |

8 U.S.C. §1101(a)(3). |

| 6. |

6 U.S.C. §279(g)(2). |

| 7. |

This section was written by William Kandel, CRS Analyst in Immigration Policy. |

| 8. |

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Border Patrol, "Stats and Summaries," https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/media-resources/stats. |

| 9. |

Ibid. |

| 10. |

Testimony of Kevin McAleenan, Commissioner, U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, in U.S. Congress, House Committee on Homeland Security, Subcommittee on Border and Maritime Security, Border Security, Commerce and Travel, Commissioner McAleenan's Vision for the Future of CBP, 115th Cong., 2nd sess., April 25, 2018. |

| 11. |

Testimony of Kevin McAleenan, Commissioner, U.S. Customs and Border Patrol, in U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Customs and Border Protection Oversight, 115th Cong., 2nd sess., December 11, 2018. |

| 12. |

This section was written by Maureen Taft-Morales and Clare Seelke, CRS Specialists in Latin American Affairs. |

| 13. |

Mollie J. Cohen, Noam Lupu, Elizabeth J. Zechmeister, eds., The Political Culture of Democracy in the Americas, 2016/17: A Comparative Study of Democracy and Governance, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP), August 2017, pp. xxvi, 15, 21, 40,60,91. |

| 14. |

See CRS Report R44812, U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America: Policy Issues for Congress. |

| 15. |

Christopher Sabatini, et al., Central America 2030: Political, Economic and Security Outlook, Florida International University, 2018, pp. 3-4; Mollie J. Cohen, Noam Lupu, Elizabeth J. Zechmeister, eds., The Political Culture of Democracy in the Americas, 2016/17: A Comparative Study of Democracy and Governance, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP), August 2017, p. 49. |

| 16. |

U.S. Department of State, International Narcotics Control Strategy Report 2017 Volume 1: Drug and Chemical Control, March 2017, p.160. |

| 17. |

International Crisis Group, El Salvador's Politics of Perpetual Violence, December 19, 2017. |

| 18. |

Crime victimization appears to play less of a role in Guatemalans' migration decisions. Jonathan T. Hiskey et al., "Leaving the Devil You Know: Crime Victimization, US Deterrence Policy, and the Emigration Decision in Central America," Latin American Research Review, vol. 53, no. 3 (2018). |

| 19. |

Hans-Joachim Heintze, Lotte Kirch, Barbara Küppers, Holger Mann, Frank Mischo, Peter Mucke, Tanja Pazdzierny, Ruben Prütz, Dr. Katrin Radtke, Friederike Strube, Daniel Weller, World Risk Report 2018, Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft, 2018, p.40. |

| 20. |

Statista 2018, https://www.statista.com/statistics/460536/employment-by-economic-sector-in-el-salvador/; https://www.statista.com/statistics/454909/employment-by-economic-sector-in-guatemala/; https://www.statista.com/statistics/510041/employment-by-economic-sector-in-honduras/. |

| 21. |

Welt Hunger Hilfe, Concern Worldwide, Global Hunger Index: Forced Migration and Hunger, October 2018, p.53. |

| 22. |

World Food Programme, Inter-American Development Bank, International Fund for Agricultural Development, Organization of American States, and International Organization for Migration, Food Insecurity and Emigration: Why people flee and the impact on family members left behind in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, August 2017, p.17. |

| 23. |

This section was written by William Kandel, CRS Analyst in Immigration Policy. |

| 24. |

D'Vera Cohn, Jeffrey S. Passel, and Ana Gonzalez-Barrera, "Rise in U.S. Immigrants From El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras Outpaces Growth From Elsewhere," Pew Research Center, December 7, 2017 |

| 25. |

Asylum seekers may intentionally abscond or may fall out of contact with the court system due to a change in address. If their court date changes, for example, and they have not provided updated contact information, they could miss their court date. If they fail to show up for a removal hearing, for example, they can be removed in absentia which would render them inadmissible for five years and ineligible for relief from removal for 10 years. |

| 26. |

This section was written by Audrey Singer, CRS Specialist in Immigration Policy. |

| 27. |

The Associated Press estimates that almost 4,000 migrants have died or gone missing en route to the United States through Mexico over the last four years. Maria Verza, "Honduras mother waits for migrant son missing en route to US," Associated Press, December 4, 2018. |

| 28. |

Ted Hesson, "Trump has whipped up a frenzy on the migrant caravan: Here are the facts," Politico, October 23, 2018. |

| 29. |

Delphine Schrank, "Migrants from caravan in limbo as U.S. says border crossing full," Reuters, April 29, 2018. |

| 30. |

Ted Hesson, "Trump has whipped up a frenzy on the migrant caravan: Here are the facts," Politico, October 23, 2018. |

| 31. |

This section was written by Peter Meyer, CRS Specialist in Latin American Affairs. |

| 32. |

U.S. Department of State, Congressional Budget Justification, Department of State, Foreign Operations and Related Programs, Fiscal Year 2018, May 23, 2017; U.S. Department of State, Congressional Budget Justification, Foreign Operations, Appendix 2, Fiscal Year 2019, March 14, 2018; and "Explanatory Statement Submitted by Mr. Frelinghuysen, Chairman of the House Committee on Appropriations, Regarding the House Amendment to Senate Amendment on H.R. 1625," Congressional Record, vol. 164, no. 50—book III (March 22, 2018), p. H2851. |

| 33. |

"Recursos Presupuestarios de los Países Asignados al Plan de la Alianza para la Prosperidad," released by Rocio Izabel Tabora, Secretaría de Finanzas de Honduras, October 16, 2018. |

| 34. |

See, for example, Manuel Orozco, "One Step Forward for Central America: The Plan for the Alliance for Prosperity," Inter-American Dialogue, March 16, 2016. |

| 35. |

U.S. Department of State, "The U.S. Strategy for Central America and Southern Mexico," press release, December 18, 2018. |

| 36. |

This section was written by Peter Meyer, CRS Specialist in Latin American Affairs. |

| 37. |

The current strategy builds on previous U.S. assistance efforts that have proven successful. For example, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) is expanding its community-based crime and violence prevention programs. A three-year impact evaluation found that communities where such programs were implemented reported 19% fewer robberies, 51% fewer extortion attempts, and 51% fewer murders than otherwise would have been expected based on trends in similar communities. Susan Berk-Seligson, Diana Orcés, and Georgina Pizzolitto, et al., Impact Evaluation of USAID's Community-Based Crime and Violence Prevention Approach in Central America: Regional Report for El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Panama, Vanderbilt University, Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP), October 2014, p. 12. |

| 38. |

Instituto Centroamericano de Estudios Fiscales, Perfiles Macrofiscales de Centroamérica, August 2018. |

| 39. |

U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Progress Report for the United States Strategy for Central America's Plan for Monitoring and Evaluation, May 2018, p.18. |

| 40. |

Mollie J. Cohen, Noam Lupu, and Elizabeth J. Zechmeister, eds., Political Culture of Democracy in the Americas, 2016/17, Vanderbilt University, Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP), August 2017. |

| 41. |

See, for examples, Jeff Ernst and Elisabeth Malkin, "In a Corruption Battle in Honduras, the Elites Hit Back," New York Times, July 1, 2018; "El Salvador's Top Cop Pursues Politicians; Now Some Want Him Gone," Reuters, December 20, 2018; and CRS Insight IN11029, Guatemalan President's Dispute with the U.N. Commission Against Impunity (CICIG). |

| 42. |

This section was written by Clare Seelke, CRS Specialist in Latin American Affairs. |

| 43. |

See CRS In Focus IF10215, Mexico's Immigration Control Efforts. |

| 44. |

This information is available through October 2018 in Spanish at http://www.politicamigratoria.gob.mx/es_mx/SEGOB/Extranjeros_presentados_y_devueltos |

| 45. |

U.S. Department of State, "United States-Mexico Declaration of Principles on Economic Development and Cooperation in Southern Mexico and Central America," December 18, 2018. |

| 46. |

U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Response to Arrivals of Asylum-Seekers from the North of Central America to Mexico: Situation Update #3, December 5, 2018. |

| 47. |

Caitlin Dickerson, "Migrants at the Border: Here's Why There's No Clear End to Chaos," New York Times, November 26, 2018. |

| 48. |

Alan Gomez, "New Trump administration policy requires asylum seekers to remain in Mexico, bans US entry," USA Today, December 20, 2018. |

| 49. |

U.S. Department of State, "Secretary Kirstjen M. Nielsen Announces Historic Action to Confront Illegal Immigration," December 20, 2018. This policy, which DHS calls the "Migrant Protection Protocols," took effect on January 25, 2019, and could face legal challenges. See U.S. Department of Homeland Security, "Migrant Protection Protocols," January 24, 2019. |

| 50. |

Government of Mexico, "Statement of the Government of Mexico regarding the decision of the United States Government to implement section 235 (b) (2) (c) of its Immigration and Nationality Law," Press Release No. 14, December 20, 2018. |

| 51. |

Jeff Ernst and Kirk Semple, "Mexico Moves to Encourage Caravan Migrants to Stay and Work," January 25, 2019. |

| 52. |

Elliot Spagat, "US launches plan for asylum seekers to wait in Mexico," Washington Post, January 29, 2019; and U.S. Department of Homeland Security, "Readout from Secretary Nielsen's Trip to San Diego," January 29, 2019. |

| 53. |

"Mexico Won't Accept Minors Awaiting U.S. Asylum Claims," Associated Press, January 29, 2019. |

| 54. |

Jonathan Blitzer, "The Long Wait for Tijuana's Migrants to Process Their Own Asylum Claims," The New Yorker, November 29, 2018. |

| 55. |

This section was written by Rhoda Margesson, CRS Specialist in International Humanitarian Policy. |

| 56. |

Examples include the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the International Organization for Migration (IOM), and the U.N. Children's Fund (UNICEF), along with organizations working outside the U.N. system, such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). U.N. Humanitarian Country Teams are also working in the Northern Triangle countries. See U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean, Year in Review 2017, April 27, 2018. |

| 57. |

CRS Interview with U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), December 4, 2018. |

| 58. |

U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), "UNHCR Alarmed by Sharp Rise in Forced Displacement in North of Central America," UNHCR Press Briefing, Geneva, Switzerland, May 22, 2018. |

| 59. |

U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Response to Arrivals of Asylum-Seekers from the North of Central America to Mexico; Situation Update, November 22, 2018. |

| 60. |

U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Response to Arrivals of Asylum-Seekers from the North of Central America to Mexico: Situation Update #3, December 5, 2018. |

| 61. |

Ibid. |

| 62. |

U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Response to Arrivals of Asylum-Seekers from the North of Central America to Mexico; Situation Update, November 22, 2018. |

| 63. |

Ibid. |

| 64. |

Ibid. |

| 65. |

This forum is based on the 1984 Cartagena Declaration on Refugees. |

| 66. |

CRS Interview with U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), December 4, 2018. |

| 67. |

This section was written by Audrey Singer, CRS Specialist in Immigration Policy. |

| 68. |

This section was written by Audrey Singer, CRS Specialist in Immigration Policy. |

| 69. |

This section was written by Andorra Bruno, CRS Specialist in Immigration Policy. |

| 70. |

This section was written by Andorra Bruno, CRS Specialist in Immigration Policy. |

| 71. |

Matter of A-B-, Respondent, 27 I&N Dec. 316 (A.G. 2018). |

| 72. |

U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, Guidance for Processing Reasonable Fear, Credible Fear, Asylum, and Refugee Claims in Accordance with Matter of A-B-, policy memorandum, July 11, 2018, p. 10. |

| 73. |

Grace v. Whitaker, __ F. Supp. 3d. __, 2018 WL 6628081 (D.D.C. 2018). |

| 74. |

This section was written by Audrey Singer, CRS Specialist in Immigration Policy. |

| 75. |

Department of Homeland Security, Automated Targeting System—TSA/CBO Common Operating Picture, Phase II, Privacy Impact Assessment Update, September 16, 2014, p. 1. |

| 76. |

Department of Homeland Security, Automated Targeting System, Privacy Impact Assessment, June 1, 2012, p. 6. |

| 77. |

Department of Homeland Security, Automated Targeting System—TSA/CBO Common Operating Picture, Phase II, Privacy Impact Assessment Update, September 16, 2014, p. 1. |

| 78. |

This section was written by Lawrence Kapp, CRS Specialist in Military Manpower Policy. |

| 79. |

Lisa Ferdinando, "DOD, DHS Outline National Guard Role in Securing Border," April 16, 2018, https://dod.defense.gov/News/Article/Article/1494860/dod-dhs-outline-national-guard-role-in-securing-border/ |

| 80. |

Jim Garamone, "5,200 Active-Duty Personnel Moving to Southwest Border, Northcom Chief Says," October 29, 2018, https://dod.defense.gov/News/Article/Article/1675810/5200-active-duty-personnel-moving-to-southwest-border-northcom-chief-says/. |

| 81. |

James Laporta, "Donald Trump Signs Authorization for Border Troops Using Lethal Force as Migrant Caravan Approaches, Document Reveals," Newsweek, November 21, 2018, https://www.newsweek.com/donald-trump-memo-migrant-caravan-border-troops-1226945 (memorandum text included at end of article). |

| 82. |

Secretary of Defense James Mattis, "Media Availability with Secretary Mattis," November 21, 2018, https://dod.defense.gov/News/Transcripts/Transcript-View/Article/1696911/media-availability-with-secretary-mattis/. |

| 83. |

Ibid. |

| 84. |