Introduction

The annual National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) authorizes appropriations for the Department of Defense (DOD) and defense-related atomic energy programs of the Department of Energy.1

In addition to authorizing appropriations, the NDAA establishes defense policies and restrictions, and addresses organizational administrative matters related to DOD. The bill incorporates provisions governing military compensation, the department's acquisition process, and aspects of DOD policy toward other countries, among other subjects. Enacted to authorize annual defense appropriations since FY1962, the bill also sometimes serves as a vehicle for legislation that originates in congressional committees other than the armed services committees.

Unlike an appropriations bill, the NDAA does not provide budget authority for government activities. While the NDAA does not provide budget authority, historically it has provided a fairly reliable indicator of congressional sentiment on funding for particular programs. The bill authorizes funding for DOD activities at the same level of detail at which budget authority is provided by the corresponding defense and military construction appropriations bills. As defense authorization and appropriations bills can differ on a line-item level, some observers view defense authorizations as funding targets rather than amounts. According to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), "An authorization act is basically a directive to Congress itself, which Congress is free to follow or alter (up or down) in the subsequent appropriation act."2

In addition, committee reports accompanying the NDAA often contain language directing an individual, such as a senior DOD official, to take a specified action by a date certain. Although such directive report language is not legally binding, agency officials generally regard it as a congressional mandate and respond accordingly.

|

Selected CRS Products For more information on the bill's organization and legislative process, see CRS In Focus IF10515, Defense Primer: The NDAA Process, by Valerie Heitshusen and Brendan W. McGarry and CRS In Focus IF10516, Defense Primer: Navigating the NDAA, by Brendan W. McGarry and Valerie Heitshusen. For more information on FY2019 defense budget request and appropriations, see CRS In Focus IF10887, The FY2019 Defense Budget Request: An Overview, by Brendan W. McGarry and CRS Report R45689, FY2019 Defense Appropriations Act (P.L. 115-245), by Pat Towell. For more information on the federal budget process, see CRS Report 98-721, Introduction to the Federal Budget Process, coordinated by James V. Saturno. |

Legislative Activity

Table 1 and Table 2 below provide an overview of legislative actions taken on the FY2019 NDAA, along with relevant funding authorization figures for budget functions in different versions of the bill considered by the 115th Congress.

Selected Actions

For FY2019, the Trump Administration requested $708.1 billion to fund programs falling under the jurisdiction of the House and Senate Armed Services Committees and subject to authorization by the annual National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA).

On May 24, 2018, the House voted 351-66 to pass H.R. 5515 (Roll no. 230), an amended version of the FY2019 NDAA reported by the House Armed Services Committee. That bill would have authorized approximately the same amount as the President's request, including $639.1 billion ($1.1 million less than the request) for the so-called base budget—that is, funds intended to pay for defense-related activities that DOD and other agencies would pursue even if U.S. armed forces were not engaged in contingency operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere. The remaining $69 billion ($158,000 less than the request), designated as funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), would have funded the incremental costs of those ongoing contingency operations, as well as any other costs that Congress and the President agreed to so designate.3

On June 18, 2018, the Senate voted 85-10 to pass its version of H.R. 5515 (Record Vote Number 128), after replacing the House-passed text of H.R. 5515 with an amended version of the FY2019 proposal reported by the Senate Armed Services Committee (S. 2987). That bill would have authorized $707.9 billion, including $639.4 billion ($492.4 million more than the request) for the base budget and $68.5 billion ($515.4 million less than the request) for OCO.4

On July 23, 2018, a conference committee reported a compromise version of the bill (H.Rept. 115-863). However, the initial conference report required revision due in part to technical issues.5 On July 25, 2018, the conference committee reported a revised conference report (H.Rept. 115-874). That bill authorized approximately the same amount as the President's request, though with several billions of dollars of adjustments to amounts within the appropriation titles.

On July 26, 2018, the House voted 359-54 to approve the conference report (Roll no. 379). On August 1, the Senate voted 87-10 to approve the conference report (Record Vote Number 181). On August 13, 2018, President Donald J. Trump signed the bill into law (P.L. 115-232).

The legislation marked the first NDAA since the FY1997 act enacted prior to the start of the fiscal year.6

|

Subcommittee Markup |

HASC Report |

House Passage |

SASC Report |

Senate Passage |

Conference Report |

Public Law |

||

|

House |

Senate |

House |

Senate |

|||||

|

5/15/2018 |

6/5/2018 |

5/24/2018 |

6/18/2018 |

7/26/2018 |

8/1/2018 |

8/13/2018 |

||

Source: Congress.gov.

Note: The Senate voted to pass its version of H.R. 5515 after replacing the House-passed text of H.R. 5515 with an amended version of the FY2019 proposal reported by the Senate Armed Services Committee (S. 2987).

Bill Overview

House and Senate conferees authorized $708.1 billion in discretionary budget authority for national defense programs in the final version of the conference report for H.R. 5515 (H.Rept. 115-874), an increase of $16 billion (2.3%) from the FY2018 enacted amount. While that figure was approximately the same amount as the President's request for FY2019, it included billions of dollars in adjustments to amounts for individual DOD appropriation titles, as well as for atomic energy defense programs and other defense-related activities. See Table 2.

|

Appropriation (Budget Function) |

FY2018 NDAA |

FY2019 Request |

H.R. 1515 (House authorized) |

H.R. 5515 (Senate authorized) |

FY2019 NDAA |

|

Procurement |

$137.3 |

$130.5 |

$133.6 |

$132.0 |

$132.3 |

|

Research, Development, Test and Evaluation |

$86.3 |

$91.1 |

$91.9 |

$92.2 |

$91.7 |

|

Operation and Maintenance |

$192.3 |

$199.5 |

$195.6 |

$200.4 |

$198.5 |

|

Military Personnel |

$141.8 |

$148.2 |

$147.5 |

$145.2 |

$147.1 |

|

Other Authorizations |

$37.7 |

$37.4 |

$37.8 |

$37.4 |

$37.0 |

|

Military Construction and Family Housing |

$10.0 |

$10.5 |

$10.3 |

$10.5 |

$10.3 |

|

Subtotal, DOD-Military (051) Base Budget |

$605.5 |

$617.1 |

$616.7 |

$617.6 |

$616.9 |

|

Atomic Energy Defense Programs (053) |

$20.6 |

$21.8 |

$22.1 |

$21.7 |

$21.9 |

|

Defense-Related Activities (054) |

$0.3 |

$0.2 |

$0.3 |

n/a |

$0.3 |

|

Total, National Defense (050) Base |

$626.4 |

$639.1 |

$639.1 |

$639.4 |

$639.1 |

|

Overseas Contingency Operations |

$65.7 |

$69.0 |

$69.0 |

$68.5 |

$69.0 |

|

Grand total, National Defense (050) |

$692.1 |

$708.1 |

$708.1 |

$707.9 |

$708.1 |

Sources: H.Rept. 115-404, conference report to accompany P.L. 115-91; H.Rept. 115-676, House Armed Services Committee report to accompany H.R. 5515; S.Rept. 115-262, Senate Armed Services Committee report to accompany S. 2987; and H.Rept. 115-874, conference report to accompany P.L. 115-232.

For example, of the $616.9 billion authorized for DOD base budget activities, the conference report included $132.3 billion for procurement, an increase of $1.8 billion (1.3%) from the President's request; $91.7 billion for research, development, test, and evaluation (RDT&E), an increase of $670 million (less than 1%) from the request; $198.5 billion for operation and maintenance, a decrease of $960 million (less than 1%) from the request; $147.1 billion for military personnel, a decrease of $1.2 billion (approximately 1%) from the request; and $10.3 billion for military construction and family housing, a decrease of $123 million (1.2%).

The conference report also included $21.9 billion for atomic energy defense programs, an increase of $108.6 million (less than 1%) from the President's request; and $300 million for other defense-related activities, an increase of $86 million (40%) from the request.

Background

Congressional authorization of FY2019 defense authorizations reflects a running debate about the size of the defense budget given the strategic and budgetary issues facing the United States.

|

Selected CRS Products For more information strategic issues, see CRS In Focus IF10485, Defense Primer: Geography, Strategy, and U.S. Force Design, by Ronald O'Rourke, CRS Report R43838, A Shift in the International Security Environment: Potential Implications for Defense—Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke, and CRS Report R44891, U.S. Role in the World: Background and Issues for Congress, by Ronald O'Rourke and Michael Moodie. For more information on budgetary issues, see CRS Report R45202, The Federal Budget: Overview and Issues for FY2019 and Beyond, by Grant A. Driessen and CRS Report R44874, The Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions, by Grant A. Driessen and Megan S. Lynch. |

The President's FY2019 budget request for DOD was shaped in part by the department's efforts to align its priorities with its 2018 National Defense Strategy and conform to discretionary spending limits set by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA; P.L. 112-25) as amended by the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018; P.L. 115-23).7

Strategic Context8

On December 18, 2017, the Trump Administration released its first National Security Strategy (NSS).9 The NSS maintains that, in addition to the threats posed to the United States by rogue regimes and violent extremist organizations that have been a central focus of national security policy since the end of the Cold War, great power rivalry and competition have once again become a central feature of the international security landscape. To advance U.S. interests effectively within this strategic context, the Administration argues, the United States must improve domestic American security and bolster economic competitiveness while rebuilding its military.

The NSS further argues that that since the 1990s, the United States has "displayed a great degree of strategic complacency," largely as a result of overwhelming and unchallenged U.S. military and economic superiority.10 Operations in the Balkans, Africa, Afghanistan, and Iraq, while challenging and complex undertakings, did not require fundamental revision of the capabilities of the United States. Yet both China and Russia appear to be developing capabilities and concepts that potentially "overmatch," or demonstrate technological superiority, to U.S. military capabilities.

Released in January 2018, DOD's 11-page unclassified summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS) articulates how the department plans to advance U.S. objectives outlined in the White House's National Security Strategy (NSS).11 Consistent with comparable documents issued by prior Administrations, the NDS maintains that there are five central external threats to U.S. interests: China, Russia, North Korea, Iran, and terrorist groups with global reach. In a break from previous Administrations, however, the NDS views retaining the U.S. strategic competitive edge relative to China and Russia as a higher priority than countering violent extremist organizations. It also contends that, unlike most of the period since the end of the Cold War, the Joint Force must now operate in contested domains where freedom of access and maneuver is no longer assured.

Accordingly, the NDS summary called for "increased and sustained investment" to counter evolving threats from China and Russia: "Long-term strategic competitions with China and Russia are the principal priorities for the Department, and require both increased and sustained investment, because of the magnitude of the threats they pose to U.S. security and prosperity today, and the potential for those threats to increase in the future."12 The NDS organizes DOD activities along three central interconnected "lines of effort": rebuilding military readiness and improving the joint force's lethality, strengthening alliances and attracting new partners, and reforming the department's business practices.

In June 2017, several months before the release of the NDS, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Marine General Joseph Dunford recommended that Congress increase the regular, or base, defense budget between 3% and 5% a year above inflation ("real growth") to maintain the U.S. competitive advantage against strategic competitors such as China and Russia.13 "We know now that continued growth in the base budget of at least 3% above inflation is the floor necessary to preserve just the competitive advantage we have today and we can't assume that our adversaries will stand still," he said.

Budgetary Context

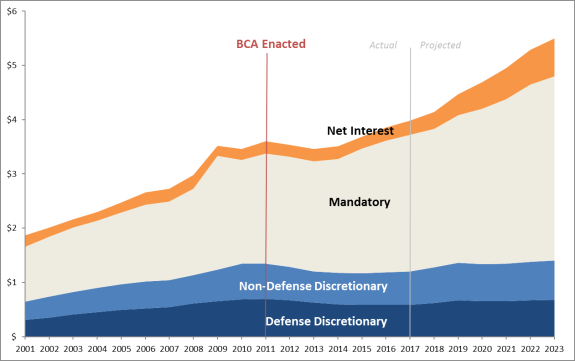

Congressional action on the FY2019 NDAA was shaped in part by a focus on controlling federal spending amid rising federal debt. The Budget Control Act emphasized limiting discretionary spending, including defense spending. However, mandatory spending makes up the largest share of federal spending and is projected to increase at a faster rate than discretionary spending. See Figure 1.

Historical Perspectives14

As the 115th Congress considered the President's FY2019 request for defense spending, OMB had estimated that since 9/11, outlays for defense discretionary programs in nominal dollars (not adjusted for inflation) would increase 122% from $306.1 billion in FY2001 to $678 billion in FY2019, while outlays for non-defense discretionary programs would increase 83% from $343 billion in FY2001 to $626 billion in FY2019. OMB had also estimated that outlays for mandatory programs would increase 172% from $1 trillion in FY2001 to $2.7 trillion in FY2019, while outlays for net interest payments on the national debt would increase 76% from $206.2 billion in FY2001 to $363.4 billion in FY2019.15

The Congressional Budget Office had projected mandatory spending and net interest payments would increase at faster rates than defense and nondefense discretionary spending over the next decade. CBO had also projected net interest payments on the national debt would surpass defense discretionary outlays in FY2023.16

FY2019 Budget Request

President Donald J. Trump's FY2019 budget request, released on February 12, 2018, included $726.8 billion for national defense, a major federal budget function that encompasses defense-related activities of the federal government.17

National defense is one of 20 major functions used by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to organize budget data and is the largest in terms of discretionary spending. The national defense budget function (identified by the numerical notation 050) comprises three subfunctions: DOD–Military (051); atomic energy defense activities primarily of the Department of Energy (053); and other defense-related activities (054), such as FBI counterintelligence activities.18

The $726.8 billion national defense budget request included $716 billion in discretionary budget authority and $10.8 billion in mandatory budget authority.19

Portion of Defense Budget Subject to NDAA

Of the $726.8 billion requested for national defense, approximately $708.1 billion was subject to authorization by the annual National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA).20 The remainder of the request was either for mandatory funds not requiring annual authorization or for discretionary funds under the jurisdiction of other congressional committees.21

Of the $708.1 billion, the Trump Administration's revised request included $639.1 billion in discretionary funding for the so-called base budget—that is, funds intended to pay for defense-related activities that the Department of Defense (DOD) and other agencies would pursue even if U.S. armed forces were not engaged in contingency operations, designated Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere.22 The remaining $69 billion of the request would fund the incremental costs of OCO, as well as any other costs that Congress and the President agreed to so designate.23

The request was consistent with discretionary spending limits (or caps) on defense activities originally established by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA; P.L. 112-25) and amended by the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018; P.L. 115-123). The FY2019 defense spending cap was $647 billion and applied to discretionary defense programs (excluding OCO).24 The cap included programs outside the scope of the NDAA and for which the Administration requested approximately $8 billion.25 Thus, the portion of the cap applicable to spending authorized by the NDAA was approximately $639 billion.

Budget Control Act

As part of an agreement to increase the statutory limit on public debt, the BCA aimed to reduce annual federal budget deficits by a total of at least $2.1 trillion from FY2012 through FY2021 compared to projected levels, with approximately half of the savings to come from defense.26 The spending limits (or caps) apply separately to defense and nondefense discretionary budget authority.27 The caps are enforced by a mechanism called sequestration that automatically cancels previously enacted appropriations by an amount necessary to reach pre-specified levels.28 The BCA effectively exempted certain types of discretionary spending from the statutory limits, including funding designated for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO)/Global War on Terrorism (GWOT).29 In the past, Congress has amended the legislation to raise the spending limits (thus lowering its deficit-reduction effect by corresponding amounts), but, as of July 2019, it had not changed the limits for FY2020 and FY2021.

OCO Funding Shift30

Of the $686.1 billion for DOD, the Trump Administration's initial request included $597.1 billion for the base budget.31 The remaining $89 billion was designated as funding for OCO.32 However, in an amendment to the budget after Congress raised spending caps as part of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018; P.L. 115-123), the Administration removed the OCO designation from $20 billion of funding, in effect, shifting that amount into the base budget request.33 In a statement on the budget amendment, White House Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney said the amended request fixed "long-time budget gimmicks" in which OCO funding had been used for base budget requirements.34 Beginning in FY2020, "the Administration proposes returning to OCO's original purpose by shifting certain costs funded in OCO to the base budget where they belong," he wrote.35

Selected Policy Issues

Military Personnel36

The Administration requested authorization for an active-duty end-strength of 1.3 million personnel, an increase of 15,600 personnel from the enacted FY2018 level; and for a reserve component end-strength of 824,700 personnel, an increase of 800 personnel from the enacted FY2018 level.37

|

Selected CRS Product For more background and analysis on this topic, see CRS Report R45343, FY2019 National Defense Authorization Act: Selected Military Personnel Issues, by Bryce H. P. Mendez et al. |

The House version of the bill would have supported the Administration's request, while the Senate amendment would have authorized an end-strength of 9,439 fewer personnel than requested, including 8,639 fewer active-duty personnel and 800 fewer reserve component personnel. The act authorizes the Administration's requested end-strength. See Table 3.

|

Component |

FY2019 Request |

H.R. 2215 (House authorized) |

H.R. 5515 |

FY2019 NDAA (P.L. 115-232) |

|

Army |

487,500 |

487,500 |

485,741 |

487,500 |

|

Navy |

335,400 |

335,400 |

331,900 |

335,400 |

|

Marine Corps |

186,100 |

186,100 |

186,100 |

186,100 |

|

Air Force |

329,100 |

329,100 |

325,720 |

329,100 |

|

Total, Active Forces |

1,338,100 |

1,338,100 |

1,329,461 |

1,338,100 |

|

Army National Guard |

343,500 |

343,500 |

343,500 |

343,500 |

|

Army Reserve |

199,500 |

199,500 |

199,500 |

199,500 |

|

Navy Reserve |

59,100 |

59,100 |

59,000 |

59,100 |

|

Marine Corps Reserve |

38,500 |

38,500 |

38,500 |

38,500 |

|

Air National Guard |

107,100 |

107,100 |

106,600 |

107,100 |

|

Air Force Reserve |

70,000 |

70,000 |

69,800 |

70,000 |

|

Coast Guard Reserve |

7,000 |

7,000 |

7,000 |

7,000 |

|

Total, Selected Reserves |

824,700 |

824,700 |

823,900 |

824,700 |

Sources: H.Rept. 115-404, conference report to accompany P.L. 115-91; H.Rept. 115-676, House Armed Services Committee report to accompany H.R. 5515; S.Rept. 115-262, Senate Armed Services Committee report to accompany S. 2987; and H.Rept. 115-874, conference report to accompany P.L. 115-232.

Notes: HASC is House Armed Services Committee, SASC is Senate Armed Services Committee.

Military Pay Raise38

Title 37, Section 1009, of the United States Code (37 U.S.C. §1009) provides a permanent formula for an automatic annual increase in basic pay that is indexed to the annual increase in the Employment Cost Index (ECI), a survey prepared by the Department of Labor's Bureau of Labor Statistics, for "wages and salaries" of private industry workers. The FY2019 budget request proposed a 2.6% increase in basic pay for military personnel in line with the formula in current law. The Senate amendment included a provision that would have waived the automatic increase in basic pay under 37 U.S.C. §1009 and specified a pay raise of 2.6%. The enacted bill contains no provision relating to a general increase in basic pay, thereby leaving in place the automatic adjustment of 37 U.S.C. §1009 amounting to 2.6% in 2019.

Officer Management Overhaul

Title V of the act contains provisions that modified key parts of the Defense Officer Personnel Management Act (DOPMA; P.L. 96-513) governing the appointment, promotion, and separation of military officers. Changes include allowing civilians with operationally relevant training or experience to enter the military up to the rank of O-6—a colonel in the Army, Air Force, or Marine Corps; or captain in the Navy—and creating an "alternative promotion" process for officers in specialized fields.

Military Construction39

The Administration requested $11.4 billion in new budget authority for DOD military construction and family housing projects, including $10.5 billion in base budget funding and $921 million in Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) funding. See Table 4.

|

Appropriation |

FY2019 Request |

H.R. 5515 |

H.R. 5515 |

FY2019 NDAA |

|

Military Constructiona |

$8.9 |

$8.8 |

$9.0 |

$8.8 |

|

Family Housingb |

$1.6 |

$1.6 |

$1.6 |

$1.6 |

|

Subtotal, Military Construction and Family Housing |

$10.5 |

$10.3 |

$10.5 |

$10.3 |

|

Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) |

$0.9 |

$0.9 |

$0.9 |

$0.9 |

|

Total, Military Construction and Family Housing |

$11.4 |

$11.3 |

$11.4 |

$11.3 |

Sources: H.Rept. 115-676, House Armed Services Committee report to accompany H.R. 5515; S.Rept. 115-262, Senate Armed Services Committee report to accompany S. 2987; and H.Rept. 115-874, conference report to accompany P.L. 115-232.

Notes: Numbers may not sum due to rounding.

a. Military construction includes amounts for NATO Security Investment Program and Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) activities.

b. Family housing includes amounts for DOD Family Housing Improvement Fund and Unaccompanied Housing Improvement Fund.

Selected Military Construction Projects

The act authorizes less funding than requested for some of the most valuable military construction projects. For example, the act authorizes

- $105 million for the MIT-Lincoln Laboratory, West Lab Compound Semiconductor Laboratory and Microsystem Integration Facility (CSL/MIF), at Hanscom Air Force Base, MA ($120 million less than requested);

- $181 million for Phase 1, Increment 2 of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency complex known as Next NGA West (N2W) in St. Louis, MO ($33 million less than requested); and

- $140 million for Phase 2 of the long-range discriminating radar system complex at Clear Air Force Station, AK ($44 million less than requested).

OCO Projects

Most of the $921 million requested for military construction using OCO funds was for projects related to the European Deterrence Initiative (see the "European Deterrence Initiative (EDI)" section). The act authorizes an additional $30.4 million for flight line support facilities and an additional $40 million for a personnel deployment processing facility, both at Al Udeid Air Base, Qatar. The act does not authorize the $69 million requested for a high-value detention facility at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

Acquisition Policy40

Congress generally exercises its legislative powers to affect defense acquisitions through Title VIII of the NDAA, typically entitled Acquisition Policy, Acquisition Management, and Related Matters. In some years, the NDAA also contains titles specifically dedicated to aspects of acquisition, such as Title XVII of the FY2018 NDAA, entitled Small Business Procurement and Industrial Base Matters.41

Congress has been particularly active in legislating acquisition reform over the last four years. For FY2016-FY2019, NDAA titles specifically related to acquisition reform contained an average of 80 provisions (318 in total), compared to an average of 47 such provisions (466 in total) in the NDAAs for the preceding 10 fiscal years.

|

Selected CRS Product For an overview of selected acquisition reform-related provisions found in the NDAAs for FY2016 (P.L. 114-92), FY2017 (P.L. 114-328), and FY2018 (P.L. 115-91), see CRS Report R45068, Acquisition Reform in the FY2016-FY2018 National Defense Authorization Acts (NDAAs), by Moshe Schwartz and Heidi M. Peters. |

Examples of recent acquisition reform-related provisions include the following:

- Changes to the role of the Chiefs of the Military Services and the Commandant of the Marine Corps (collectively referred to as the Service Chiefs) in the acquisition process (Section 802 of P.L. 114-92, the FY2016 NDAA);

- Splitting the office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics (USD [AT&L]) into two separate offices: the office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment (USD A&S) and the office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (USD R&E) (Section 901 of P.L. 114-328, the FY2017 NDAA);

- Strengthening the role of the military departments in acquisitions (see, for example, Section 897 of P.L. 114-328, the FY2017 NDAA);

- Increasing the government-wide simplified acquisition threshold from $150,000 to $250,000 (Section 805 of P.L. 115-91); and,

- Creating or expanding numerous rapid acquisition authorities, such as establishing middle tier acquisition pathways for rapid production and fielding (Section 804 of the FY2016 NDAA), and expanding and making permanent authorities relating to prototyping and follow-on production conducted using procurement authorities known as other transactions (Section 815 of P.L. 114-92, the FY2016 NDAA).42

While the FY2019 NDAA generally does not include sweeping defense acquisition system reform-related provisions similar to those included in the FY2016-FY2018 NDAAs, it does include numerous provisions making other changes relating to defense acquisitions, such as the following:

- Creating a framework to consolidate defense acquisition-related statutes in a new Part V of Subtitle A of Title 10, U.S. Code (Sections 801-809);

- Increasing the DOD micro-purchase threshold from $5,000 to $10,000 (Section 821);

- Requiring DOD to conduct a study of the frequency and effects of so-called "second bite at the apple" bid protests involving the same contract award or proposed award filed through both the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and the U.S. Court of Federal Claims (Section 822);43

- Splitting the Title 41 definition of commercial item into separate definitions for commercial product and commercial service (Section 836); and

- Limiting the government-wide use of lowest price technically acceptable (LPTA) source selection criteria (Section 880).44

European Deterrence Initiative (EDI)45

The act authorizes $6.3 billion in OCO funding for the European Deterrence Initiative (EDI), an effort DOD began in 2014 to reassure NATO allies in Central and Eastern Europe of a continued U.S. commitment to their national security after the Russian military intervention in Ukraine, in addition to $250 million for Ukraine security assistance.46 Of the latter amount, $50 million was authorized for "lethal assistance," including anti-armor weapon systems, mortars, crew-served weapons and ammunition, grenade launchers and ammunition, small arms and ammunition; as well as counter-artillery radars, including medium-range and long-range counter-artillery radars that can detect and locate long-range artillery.47 Most of the EDI funding is intended for prepositioning a division-sized set of equipment in Europe and boosting the regional presence of U.S. forces.

Iraqi and Syrian Forces Training48

The act authorizes $1.4 billion in OCO funding for activities to counter the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) by training and equipping Iraqi Security Forces and vetted Syrian opposition forces. The act includes a provision (Section 1233) limiting the use of roughly half of the $850 million for Iraq until the Secretary of Defense submits a report to the congressional defense committees on the U.S. strategy in Iraq. Another provision (Section 1231) limits the use of all of the $300 million for Syria until the President submits a report to congressional committees on the U.S. strategy in Syria. The Administration submitted the required reports to Congress in early 2019.

Foreign Investment49

In response to concerns from some Members of Congress that certain foreign direct investment, primarily by Chinese firms, may pose risks to U.S. national defense and economic security, Title XVII of the act incorporates provisions designed to limit foreign access to sensitive U.S. technology. Subtitle A of Title XVII, the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 (FIRRMA), expands the purview of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) to address national security concerns in part by amending the current process for the committee to review, on behalf of the President, the national security implications of foreign direct investment in U.S. companies. Subtitle B of Title XVII, the Export Controls Act of 2018, includes provisions to expand controls for exporting certain "dual-use" civilian and military items in part by requiring the establishment of an "interagency process to identify emerging and foundational technologies."

|

Selected CRS Products For more information and background on the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), see CRS In Focus IF10952, CFIUS Reform: Foreign Investment National Security Reviews, by James K. Jackson and Cathleen D. Cimino-Isaacs and CRS Report RL33388, The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), by James K. Jackson. |

Prohibition on Chinese Telecommunications Equipment50

In response to concerns from some Members of Congress that Chinese telecommunications equipment manufacturers may pose a security risk to U.S. communications infrastructure, the act includes a provision (Section 889) prohibiting the heads of federal agencies from procuring telecommunications equipment or services from companies linked to the government of China, including Huawei Technologies Company and ZTE Corporation, among others. Huawei filed suit against the United States over the provision, arguing that it amounts to an unconstitutional "bill of attainder."51

Another provision of the act (Section 1091) prohibits DOD from obligating funds authorized to be appropriated by the act or otherwise available for Chinese language instruction provided by Confucius Institutes, language and culture centers affiliated with China's Ministry of Education, unless the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness issues a waiver. It also bars DOD use of any obligated funds to support a Chinese language program at an institution of higher education that hosts a Confucius Institute.

Selected Acquisition Programs52

Strategic Nuclear Forces53

DOD has described upgrading the nuclear triad—that is, submarines armed with submarine-launched ballistic missiles, land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles, and strategic bombers carrying gravity bombs and air-launched cruise missiles—as its "number one priority."54

The Trump Administration's 2018 Nuclear Posture Review, released in February 2018, reiterated the findings of previous reviews "that the nuclear triad—supported by North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) dual-capable aircraft and a robust nuclear command, control, and communications system—is the most cost-effective and strategically sound means of ensuring nuclear deterrence."55

The department said that programs—such as the Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine, B-21 long-range strike bomber, and Long-Range Standoff (LRSO) cruise missile—to replace the existing inventory of systems intended to deliver nuclear weapons would be "fully funded" for the year if its FY2019 budget requests were met.56

See Table 5 for information on the FY2019 budget request and authorizations for selected strategic offense and long-range systems.57

|

Program (CRS Report) |

Appropriation Type |

FY2019 Request |

H.R. 5515 |

H.R. 5515 |

FY2019 NDAA |

|

Columbia-Class Ballistic Missile Submarine (R41129) |

Proc. |

$3,005.3 |

$3,088.0 |

$3,005.3 |

$3,242.3 |

|

RDT&E |

$704.9 |

$716.9 |

$704.9 |

$716.9 |

|

|

B-21 Bomber (R44463) |

Proc. |

||||

|

RDT&E |

$2,314.2 |

$2,314.2 |

$2,314.2 |

$2,314.2 |

|

|

D-5 Trident II Missile Mods |

Proc. |

$1,078.8 |

$1,078.8 |

$1,078.8 |

$1,078.8 |

|

RDT&E |

$157.7 |

$166.7 |

$157.7 |

$166.7 |

|

|

Bomber Upgrades (R43049) |

Proc. |

$221.1 |

$183.4 |

$216.3 |

$211.4 |

|

RDT&E |

$723.8 |

$738.6 |

$738.6 |

$725.7 |

|

|

Long-Range Standoff Weapon |

Proc. |

||||

|

RDT&E |

$614.9 |

$699.9 |

$699.9 |

$699.9 |

|

|

Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent |

Proc. |

||||

|

RDT&E |

$345.0 |

$414.4 |

$414.4 |

$414.4 |

|

|

Conventional Prompt Global Strike (R41464) |

Proc. |

||||

|

RDT&E |

$263.4 |

$413.4 |

$263.4 |

$413.4 |

Source: CRS analysis of DOD budget documentation and H.Rept. 115-874, conference report to accompany H.R.5515, John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 (P.L. 115-232).

Note: Full citations of CRS products are listed in the Appendix.

Columbia-Class Ballistic Missile Submarine58

The Columbia-class program, previously known as the Ohio replacement program (ORP) or SSBN(X) program, is a program to design and build a new class of 12 ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) to replace the Navy's current force of 14 Ohio-class SSBNs. The Navy has identified the Columbia-class program as its top priority program. The service wants to procure the first Columbia-class boat in FY2021. The Navy's proposed FY2019 budget requested $3 billion in advance procurement (AP) funding and $705 million in research and development funding for the program. The budget also included $1.3 billion to continue refurbishing the Trident II (or D-5) missiles that arm the submarines. The act authorizes $3.2 billion for the Columbia-class program. The act supports the President's request for refurbishment of the Trident II missiles, and increased research-and-development funding for the effort.

B-21 Long-Range Strike Bomber59

The budget request included $2.3 billion to continue development of the B-21 long-range bomber, which the Air Force describes as one of its top three acquisition priorities. Acquisition of the airplane is slated to begin in 2023. The new bomber—like the B-2s and B-52s currently in U.S. service—could carry conventional as well as nuclear weapons. For the latter role, the request included $615 million to continue development of the Long-Range Standoff Weapon (LRSO), a cruise missile that would replace the 1980s-vintage Air-Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM) currently carried by U.S. bombers. The act supports the President's budget request for the B-21 bomber. The act authorizes an increase of $85 billion for the LRSO to $700 million.

Land-Based Ballistic Missiles60

The budget request included $345 million to continue developing a new, land-based intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), known as the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD), which in 2029 would begin replacing the Minuteman III missiles currently in service. The act authorizes an increase of $69 million to $414 million for the new Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent.

Low-Yield D-5 Nuclear Warhead 61

The budget request included $65 million for the W76-2 warhead modification program. The effort is intended to modify an unspecified number of Trident II MK4/W76 warheads, each of which has a yield of 100 kilotons, into a lower-yield variant referred to as the W76-2. The atomic weapons used at Hiroshima and Nagasaki were roughly 15 and 20 kilotons, respectively. The Trump Administration's February 2018 Nuclear Posture Review called for "low-yield" nuclear options to preserve "credible deterrence against regional aggression."62 The act authorizes the requested funding.

Ballistic Missile Defense Programs63

Since the late 1940s, the United States has developed and deployed ballistic missile defenses (BMD) to defend against enemy missiles. Since the start of an expanded initiative under President Ronald Reagan in 1985, BMD has been a key national security interest in Congress. Lawmakers have since appropriated more than $200 billion for a broad range of research and development programs and deployment of BMD systems. The United States has deployed a global array of networked ground-, sea-, and space-based sensors for target detection and tracking, an extensive number of ground- and sea-based hit-to-kill (direct impact) and blast fragmentation warhead interceptors, and a global network of command, control, and battle management capabilities to link those sensors with those interceptors.

The Trump Administration's FY2019 budget request included a total of $12.9 billion for defense against ballistic missiles, of which $9.9 billion would be allocated to the Missile Defense Agency (MDA).64

See Table 6 for information on the FY2019 budget request and authorization actions for selected ballistic missile defense systems.

|

Program (CRS Report) |

Appr. |

FY2019 Request |

H.R. 5515 (House Authorized) |

H.R. 5515 (Senate Authorized) |

FY2019 NDAA (P.L. 115-232) |

||||

|

# |

$ |

# |

$ |

# |

$ |

# |

$ |

||

|

Ground-Based Midcourse Defense |

Proc. |

14 |

$524.0 |

14 |

$524.0 |

14 |

$524.0 |

14 |

$524.0 |

|

RDT&E |

$1,008.3 |

$799.0 |

$791.0 |

$890.0 |

|||||

|

Improvements to Ground-Based Midcourse Defense |

Proc. |

||||||||

|

RDT&E |

$1,019.6 |

$791.2 |

$880.2 |

$790.0 |

|||||

|

Aegis and Aegis Ashore (RL33745) |

Proc. |

71 |

$820.8 |

71 |

$820.8 |

71 |

$820.8 |

71 |

$820.8 |

|

RDT&E |

$891.0 |

$891.1 |

$891.0 |

$891.0 |

|||||

|

Terminal Ballistic Missile Defense (THAAD, Patriot/PAC-3 and Patriot Modifications) |

Proc. |

322 |

$2,430.0 |

322 |

$2,450.0 |

322 |

$2,430.0 |

322 |

$2,440.0 |

|

RDT&E |

$340.6 |

$510.6 |

$524.7 |

$534.7 |

|||||

|

Israeli Cooperative Missile Defense Programs (incl. David's Sling and Iron Dome) |

Proc. |

$200.0 |

$200.0 |

$200.0 |

$200.0 |

||||

|

RDT&E |

$300.0 |

$300.0 |

$300.0 |

$300.0 |

|||||

Source: CRS analysis of DOD budget documentation and H.Rept. 115-874, conference report to accompany H.R.5515, John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 (P.L. 115-232).

Note: Full citations of CRS products are listed in the Appendix.

U.S. Homeland Missile Defense

The Administration requested a total of approximately $2.6 billion for the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense (GMD), which included funding for systems and related improvements such as Common Kill Vehicle Technology, Pacific Discriminating Radar, and Long Range Discrimination Radar. As of November 2017, the system comprised 44 interceptor missiles at two sites, including 40 at Fort Greely in Alaska and four at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.65 The interceptors are intended to destroy intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) with ranges in excess of 5,500 kilometers launched toward U.S. territory from countries such as North Korea. The department is adding another site at Fort Greely with 20 interceptors as part of a plan to expand the system to include 64 interceptors.66 The request included funding for an additional four interceptors and 10 silos, as well as continued development of a new warhead called the Redesigned Kill Vehicle (RKV) intended to replace the existing warhead known as the Exoatmospheric Kill Vehicle (EKV).67

While the House and Senate generally supported the request for the GMD system—they authorized the procurement request and most of the RDT&E request—conferees included a provision (Section 1683) that requires at least one successful flight intercept test of the RKV before it could enter production. The provision also requires the director of the Missile Defense Agency to report on ways to accelerate the fielding of the additional 20 interceptors with RKVs at Fort Greely.

Regional Missile Defense

The Administration's budget request included $1.1 billion for procurement and additional development work associated with the Terminal High-Altitude Air Defense (THAAD) interceptors, intended to intercept short-, medium-, and intermediate-range ballistic missiles.68 THAAD is a transportable system designed to defend troops abroad and population centers. In testing, the system has generally performed well by most measures, but it has not operated in combat. Both the House and Senate supported the Administration's request for $874 million in procurement for 82 THAAD interceptors and increased funding for associated research and development.

The request included $1.4 billion in procurement funding for the Army's Patriot system, including 240 Patriot Advanced Capability (PAC-3)/Missile Segment Enhancement (MSE) interceptors.69 The most mature U.S. BMD system, Patriot was used with mixed results in combat in the 1991 and 2003 wars against Iraq and is fielded around the world by the United States and other countries that have purchased the system. Patriot is a mobile system and designed to defend relatively small areas such as military bases and airfields. Patriot works with THAAD to provide an integrated and overlapping defense against incoming missiles in their final phase of flight. The act supports the Administration's request.

The act includes a provision (Section 241) requiring the Secretary of the Army to report on the survivability of air defense artillery, including "an analysis of the utility of relevant active kinetic capabilities, such as a new, long-range counter-maneuvering threat missile and additional indirect fire protection capability units to defend Patriot and Terminal High Altitude Area Defense batteries."

Military Space Programs70

The President's budget request included $9.3 billion in funding for National Security Space (NSS) acquisition programs.71

National Security Space is one of 12 Major Force Programs (MFP) of the DOD and includes funding for space launches, satellites, and support activities.72 MFP-12 includes funding for some classified programs and, for the most part, does not include funding for National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) and National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) programs.73

See Table 7 for information on the FY2019 budget request and authorization actions for selected military space programs.

|

Program (CRS Report) |

Appr. |

FY2019 Request |

H.R. 5515 (House Authorized) |

H.R. 5515 (Senate Authorized) |

FY2019 NDAA (P.L. 115-232) |

||||

|

# |

$ |

# |

$ |

# |

$ |

# |

$ |

||

|

Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (R44498) |

Proc. |

5 |

$1,704.5 |

5 |

$1,704.5 |

5 |

$1,704.5 |

5 |

$1,704.5 |

|

RDT&E |

$245.4 |

$245.4 |

$245.4 |

$245.4 |

|||||

|

Global Positioning System |

Proc. |

$71.6 |

$76.6 |

$71.6 |

$71.6 |

||||

|

RDT&E |

$1,405.2 |

$1,405.2 |

$1,405.2 |

$1,387.2 |

|||||

|

Space Based Infrared System |

Proc. |

$138.4 |

$138.4 |

$138.4 |

$138.4 |

||||

|

RDT&E |

$703.7 |

$703.7 |

$803.7 |

$803.7 |

|||||

|

Advanced Extremely High Frequency and SATCOM Projects |

Proc. |

$91.4 |

$91.4 |

$91.4 |

$91.4 |

||||

|

RDT&E |

$676.5 |

$676.5 |

$676.5 |

$676.5 |

|||||

Source: CRS analysis of DOD budget documentation and H.Rept. 115-874, conference report to accompany H.R.5515, John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 (P.L. 115-232).

Note: Full citations of CRS products are listed in the Appendix.

Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle

The budget request for NSS acquisition programs included approximately $2 billion to continue acquiring satellite launchers under the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) program and to continue developing a replacement for the Russian-made rocket engine used in some national security space launches since the early 2000s.74 The act supported the budget request.

The act includes a provision (Section 1603) to designate the EELV program as the National Security Space Launch (NSSL) program, effective March 1, 2019.75 The provision also requires the Secretary of Defense to consider both "reusable and expendable launch vehicles" in any future solicitations "for which the use of a reusable launch vehicle is technically capable and maintains risk at acceptable levels."76

Global Positioning System

The budget request included approximately $1.5 billion for the GPS satellite program and related projects.77 The technology provides worldwide positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) information to military and civilian users.78 Funding would support launch of two GPS III satellites, development of GPS Next Generation Operational Control System (OCX), and integration of Military GPS User Equipment (MGUE) intended in part to provide a more powerful jam-resistant signal and information to military personnel in contested environments.79 The act authorizes $18 million less than the requested $1.4 billion in research and development funding due to what the conferees described as "insufficient justification."80

Space-Based Infrared System

The budget request included $842 million for the Space-Based Infrared System (SBIRS), including $704 million for research, development, test, and evaluation and $138 million for procurement.81 The system is a successor to the Defense Support Program (DSP) designed in part to provide early warning of a strategic missile attack on the United States and to support missile defense activities.82 The request was intended to support launch of Geosynchronous Earth Orbit (GEO) satellites and development of Next-Generation Overhead Persistent Infrared (OPIR) satellites.83 The act authorizes increasing RDT&E funding by $100 million to $804 million to "accelerate sensor development."84

The act includes a provision (Section 1613) requiring the Secretary of Defense to evaluate supply chain vulnerabilities for protected satellite communications and OPIR.85 The conference report accompanying the bill directs the head of the Government Accountability Office (GAO) "to review the early planning for the next generation OPIR system and associated ground capabilities," and assess, in part, "to what extent will the next generation OPIR system continue to fulfill existing key SBIRS capabilities?"86

Advanced Extremely High Frequency and Satellite Communications Projects

The budget request included $842 million for Advanced Extremely High Frequency (AEHF) and Satellite Communications (SATCOM) projects, including $677 million in research, development, test, and evaluation and $91 million in procurement.87 The projects are intended in part to provide communications that are secure, survivable, and resistant to jamming.88 Funding was to support the fifth and sixth AEHF satellites, as well as activities to improve AEHF operational resiliency through programs such as Protected Tactical Service (PTS), Protected SATCOM Services-Aggregated (PSCS-A), and Protected Tactical Enterprise Service (PTES).89 The act supports the budget request.90

The act includes a provision (Section 1614) requiring the Secretary of Defense to report on how the evolved strategic satellite program, PTS, and PTES "will meet the requirements for resilience, mission assurance, and the nuclear command, control, and communication missions of the Department of Defense."91

U.S. Space Command

The act includes a provision (Section 1601) requiring the President, with the advice and assistance of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and through the Secretary of Defense, to establish U.S. Space Command as a subordinate unified command under U.S. Strategic Command "for carrying out joint space warfighting operations."92

The provision states the commander of U.S. Space Command is responsible for "ensuring the combat readiness of forces assigned to the space command" and "monitoring the preparedness to carry out assigned missions of space forces assigned to unified combatant commands other than the United States Strategic Command."93

Ground Vehicle Programs94

In addition to modernizing the ground forces' existing armored combat vehicles such as the M-1 Abrams tank, M-2 Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicle (IFV), and Stryker wheeled combat vehicle, the Administration's FY2019 budget request included funding for newer capabilities, including mobile defense against cruise missiles and unmanned aircraft, and improved firepower and mobility for infantry units.

See Table 8 for information on the FY2019 budget request and authorizations for selected ground vehicle programs.

|

Program (CRS Report) |

Appr. |

FY2019 Request |

H.R. 5515 (House Authorized) |

H.R. 5515 (Senate Authorized) |

FY2019 NDAA (P.L. 115-232) |

||||

|

# |

$ |

# |

$ |

# |

$ |

# |

$ |

||

|

M-1 Abrams Tank (upgrade and modifications [mods]) |

Proc. |

135 |

$2,492.6 |

135 |

$2,492.6 |

135 |

$2,492.6 |

135 |

$2,492.6 |

|

RDT&E |

$164.8 |

$164.8 |

$164.8 |

$149.9 |

|||||

|

M-2 Bradley Fighting Vehicle |

Proc. |

61 |

$880.4 |

61 |

$880.4 |

61 |

$556.4 |

61 |

$720.4 |

|

RDT&E |

$167.0 |

$167.0 |

$167.0 |

$154.8 |

|||||

|

M-109A6 Paladin self-propelled artillery |

Proc. |

36 |

$418.8 |

36 |

$493.8 |

36 |

$528.8 |

45 |

$528.8 |

|

RDT&E |

|||||||||

|

Stryker Combat Vehicle (new and mods) |

Proc. |

3 |

$309.4 |

113 |

$498.2 |

3 |

$309.4 |

69 |

$363.5 |

|

RDT&E |

$58.9 |

$58.9 |

$58.9 |

$49.1 |

|||||

|

Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (R43240) |

Proc. |

197 |

$710.2 |

197 |

$710.2 |

197 |

$610.2 |

197 |

$679.0 |

|

RDT&E |

$118.2 |

$118.2 |

$118.2 |

$118.2 |

|||||

|

Amphibious Combat Vehicle (R42723) |

Proc. |

30 |

$167.5 |

30 |

$167.5 |

30 |

$167.5 |

30 |

$167.5 |

|

RDT&E |

$98.2 |

$98.2 |

$98.2 |

$76.1 |

|||||

|

Infantry Firepower and Mobility Programsa (R44968) |

Proc. |

$47.0 |

$37.0 |

$47.0 |

$42.7 |

||||

|

RDT&E |

$401.8 |

$401.8 |

$326.8 |

$326.8 |

|||||

|

Air Defense Programsb (IN10931) |

Proc. |

$176.9 |

$176.9 |

$676.9 |

$260.2 |

||||

|

RDT&E |

$326.8 |

$326.8 |

$356.8 |

$304.8 |

|||||

Source: CRS analysis of DOD budget documentation and H.Rept. 115-874, conference report to accompany H.R.5515, John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 (P.L. 115-232).

Notes: Full citations of CRS products are listed in the Appendix.

a. Infantry Firepower and Mobility Programs include Mobile Protected Firepower (MPF), Ground Mobility Vehicle (GMV), and Light Reconnaissance Vehicle (LRV).

b. Air Defense Programs include Initial Maneuver Short-Range Air Defense (IM-SHORAD) and Indirect Fire Protection Capability (IFPC).

Legacy Systems

The act authorizes most of the approximately $2.7 billion requested to upgrade the Army's fleet of M-1 Abrams tanks, the service's main battle tank that entered service in 1980.95 The funding was intended to upgrade a portion of the fleet with a system enhancement package (SEP) that includes new armor, electronics, and weapons stations. It was also to equip three brigades with the Trophy active protection system (APS), designed in part to automatically acquire, track, and respond with hard or soft kill capabilities to a variety of threats, including rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs) and anti-tank guided missiles (ATGMs).

The act authorizes more funds than requested to accelerate two other components of the Army's current combat vehicle fleet. It authorizes $413 million, $44 million more than requested, to replace the flat underside of many types of the Stryker wheeled combat vehicles with a V-shaped bottom intended to more effectively mitigate the explosive force of buried landmines or improvised explosive devices (IEDs).96 It also authorized $529 million, $110 million more than requested, to replace the chassis and powertrain of the M-109 Paladin self-propelled howitzer with the more powerful and robust chassis of the Bradley troop carrier.97

The act authorizes fewer funds than requested for components of the Army's existing combat vehicle fleet. It authorizes $875 million, $172 million less than requested, to continue modernizing the Bradley primarily due to a "program decrease." It also authorizes $244 million, $22 million less than requested, for the Amphibious Combat Vehicle (ACV), a successor to the Marine Corps' AAV-7 amphibious troop carrier;98 and $797 million, $31 million less than requested, for the Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV), intended to the place the Vietnam-era M-113 tracked personnel carrier.99

The act includes a provision (Section 254) requiring the Secretary of the Army to develop a strategy to competitively procure a new transmission for the Bradley fighting vehicle, including an analysis of potential cost savings and performance improvements from a transmission common to the Bradley family of vehicles, including the AMPV and Paladin.

Infantry Firepower and Mobility

The Administration requested $449 million to develop and begin purchasing vehicles intended to boost the lethality and mobility of Army Infantry Brigade Combat Teams (IBCTs). The bulk of the funds were to develop a lightweight tank, designated Mobile Protected Firepower (MPF). The remainder of the funds were to begin purchasing four-wheel-drive, off-road vehicles for reconnaissance missions and troop transport, designated Light Reconnaissance Vehicle (LRV) and Ground Mobility Vehicle (GMV), respectively.

The act authorizes $370 million for the programs, $79 million less than requested, with most of the reduction due to a "Mobile Protected Firepower decrease."

The act includes a provision (Section 248) requiring the Secretary of the Army to submit a report to the Armed Services Committees on active protection systems (APS) for armored combat and tactical vehicles. Specifically, the provision required the report to: assess the effectiveness of such systems recently tested on the Abrams, Bradley, and Stryker; discuss plans for further testing, proposals for future development, and a timeline for fielding; and describe how the service plans to incorporate such systems into new armored combat and tactical vehicles, such as MPF, AMPV, and the Next Generation Combat Vehicle (NGCV), the Army's replacement for the Bradley.

Air Defense

The Administration requested $504 million for programs intended to enhance mobile Army defense against aircraft, including unmanned aerial systems and cruise missiles. These include a Stryker combat vehicle equipped to launch Stinger missiles, designated Interim Maneuver Short-Range Air Defense systems (IM-SHORAD), and a larger, truck-mounted missile launcher, designated Indirect Fire Protection Capability (IFPC).

The act authorizes $565 million for the programs, $61 million more than requested, driven by an increase to IFPC for "interim cruise missile defense."

The act includes a provision (Section 241) requiring the Secretary of the Army to submit a report to the Armed Services Committees on the service's efforts to improve the survivability of air defense artillery, including an analysis of new technology and additional units to defend Patriot and THAAD batteries.

Shipbuilding Programs100

In December 2016, the Navy adopted a new force goal of 355 ships—a total similar to the 350-ship fleet President Trump had called for during the 2016 election campaign. The 355-ship plan replaced a previous 308-ship plan the Navy had adopted in March 2015.101

The Navy's proposed FY2019 budget requested the procurement of 10 combat ships, including two Virginia-class attack submarines, three DDG-51 class destroyers, one Littoral Combat Ship (LCS), two TAO-205 class oilers, one Expeditionary Sea Base ship, and one towing, salvage, and rescue ship.102

The act authorizes $1.9 billion more than the request, including funding for the 10 combat ships requested, as well as two additional LCSs. The act authorizes procurement of a fourth Ford-class aircraft carrier (CVN-81). The act also authorizes procurement of additional noncombat ships, including a cable ship that was not requested and three more ship-to-shore connectors than the five that were requested.

See Table 9 for summary information on the FY2019 budget request and authorization actions for selected shipbuilding programs.

|

Program (CRS Report) |

Appr. |

FY2019 Request |

H.R. 5515 (House Authorized) |

H.R. 5515 (Senate Authorized) |

FY2019 NDAA (P.L. 115-232) |

||||

|

# |

$ |

# |

$ |

# |

$ |

# |

$ |

||

|

Ford-class Aircraft Carrier (RS20643) |

Proc. |

$1,598.2 |

1 |

$1,549.1 |

$1,598.2 |

1 |

$1,598.2 |

||

|

RDT&E |

$108.2 |

$123.2 |

$108.2 |

$108.2 |

|||||

|

Mid-life Refueling and Overhaul for Nuclear-powered Carriers |

Proc. |

$449.6 |

$449.6 |

$449.6 |

$449.6 |

||||

|

RDT&E |

|||||||||

|

Virginia-class Attack Submarine (RL32418) |

Proc. |

2 |

$7,169.8 |

2 |

$8,107.8 |

2 |

$7,419.8 |

2 |

$7,149.8 |

|

RDT&E |

$145.6 |

$124.2 |

$145.6 |

$145.6 |

|||||

|

DDG 51-class Aegis destroyer (RL32109) |

Proc. |

3 |

$5,699.2 |

3 |

$5,387.2 |

3 |

$5,921.7 |

3 |

$5,867.7 |

|

RDT&E |

$213.7 |

$193.7 |

$213.7 |

$203.4 |

|||||

|

Mods to Existing Aegis Cruisers and Destroyers |

Proc. |

$764.4 |

$863.7 |

$764.4 |

$756.0 |

||||

|

RDT&E |

|||||||||

|

Littoral Combat Ship, including modules (RL33741 and R44972). |

Proc. |

1 |

$1,074.1 |

3 |

$1,963.2 |

1 |

$1,002.5 |

3 |

$1,920.5 |

|

RDT&E |

$162.8 |

$162.8 |

$162.8 |

$162.8 |

|||||

|

T-AO 125-class Refueling Oiler |

Proc. |

2 |

$1,052.2 |

2 |

$1,032.2 |

2 |

$1,052.2 |

2 |

$1,052.2 |

|

RDT&E |

$1.3 |

$1.3 |

$1.3 |

$1.3 |

|||||

|

LPD 17-class or LX(R)-class Amphibious Landing Ship |

Proc. |

$150.0 |

$650.0 |

$500.0 |

|||||

|

RDT&E |

$5.5 |

$5.5 |

$5.5 |

$5.5 |

|||||

|

Expeditionary Seabase Ship |

Proc. |

1 |

$650.0 |

1 |

$630.0 |

1 |

$650.0 |

1 |

$647.0 |

|

RDT&E |

|||||||||

|

Ship-to-Shore Connector |

Proc. |

5 |

$334.8 |

8 |

$517.3 |

5 |

$334.8 |

8 |

$517.3 |

|

RDT&E |

$1.4 |

$1.4 |

$1.4 |

$1.4 |

|||||

|

Cable Ship |

Proc. |

1 |

$250.0 |

1 |

$250.0 |

||||

|

RDT&E |

|||||||||

|

Towing, Salvage, and Rescue Ship |

Proc. |

1 |

$80.5 |

1 |

$75.5 |

1 |

$80.5 |

1 |

$80.5 |

|

RDT&E |

|||||||||

Source: CRS analysis of DOD budget documentation and H.Rept. 115-874, conference report to accompany H.R.5515, John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 (P.L. 115-232).

Note: Full citations of CRS products are listed in the Appendix.

Carrier 'Block Buy'

The Administration's $1.6 billion request to fund a Ford-class aircraft carrier was intended as the fourth of eight annual increments to cover the estimated $12.6 billion cost of what will be the third ship of the Ford class. That ship, designated CVN-80 and named Enterprise, is slated for delivery to the Navy at the end of FY2027.103

While the act does not authorize appropriations for a fourth Ford-class aircraft carrier (CVN-81), the law allows for the procurement to occur in conjunction with CVN-80. Proponents of such an arrangement, known as block buy contracting, contend that it could accelerate the delivery of the fourth ship and reduce the overall cost of the two vessels.104

The act includes a provision (Section 121) stating that before the funds could be used for a block buy, the Secretary of Defense would have to certify to the congressional defense committees an analysis demonstrating that the approach would "result in significant savings compared to the total anticipated costs of carrying out the program through annual contracts."

Littoral Combat Ships105

In addition to the Administration's request of $646 million to procure a Littoral Combat Ship, the act authorizes $950 million to procure two more LCSs, which conferees described as a "program increase—two ships." The increase more than offset a decrease of $37.7 million in procurement funding for the program to "align plans and other costs with end of production."

Amphibious Landing Ships

The act authorizes an additional $500 million for an LPD-17-class amphibious landing transport or a variant of that ship designated LX(R) and an additional $182.5 million for three more air-cushion landing craft in addition to the five requested to haul tanks and other equipment ashore from transport ships.

2017 Destroyer Collisions

The act includes provisions intended to address factors perceived to have contributed to the two separate collisions in 2017 involving Pacific Fleet destroyers that resulted in the deaths of 17 U.S. sailors. A provision (Section 322) requires that Navy ships be subject to inspections with "minimal notice" to the crew and annual reports on "the material readiness of Navy ships as compared to established material requirements standards," among other topics. Another provision (Section 323) limited to 10 years the time that aircraft carriers, amphibious ships, cruisers, destroyers, frigates, and littoral combat ships can be based outside the United States. Another provision (Section 526) stated the Secretary of the Navy is to require key watch standers—that is, a person standing watch on a ship, such as an officer of the deck, engineering officer of the watch, conning officer or piloting officer—to "maintain a career record of watchstanding hours and specific operational evolutions."

Aviation Systems106

The act, for the most part, authorizes funding for the Administration's request for military aircraft acquisition.

The act authorizes additional funding for 15 more aircraft than requested, including six AH-64 Apache attack helicopters, five UH-60 Black Hawk utility helicopters, two MQ-9 Reaper reconnaissance and attack unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), one RQ-4 Global Hawk long-range reconnaissance UAV, and one E-2 Hawkeye airborne surveillance aircraft. The act authorizes less funding than requested for other programs, including the MQ-25 Stingray carrier-based refueling and reconnaissance UAV and the KC-46 refueling tanker aircraft.

See Table 10 for information on the FY2019 budget request and authorizations for selected aircraft programs.

|

Program (CRS Report) |

Appr. |

FY2019 Request |

H.R. 5515 (House Authorized) |

H.R. 5515 (Senate Authorized) |

FY2019 NDAA (P.L. 115-232) |

||||

|

# |

$ |

# |

$ |

# |

$ |

# |

$ |

||

|

Fighter and Ground-Attack Aircraft |

|||||||||

|

F/A-18 |

Proc. |

24 |

$1,996.4 |

24 |

$1,966.4 |

24 |

$1,996.4 |

24 |

$1,940.1 |

|

RDT&E |

|||||||||

|

F/A-18 modifications (mods) |

Proc. |

$1,213.5 |

$1,211.0 |

$1,227.4 |

$1,224.9 |

||||

|

RDT&E |

$301.8 |

$309.3 |

$325.8 |

$308.8 |

|||||

|

F-35, all variants and mods (RL30563) |

Proc. |

77 |

$8,798.5 |

77 |

$8,665.9 |

75 |

$8,698.5 |

77 |

$8,665.9 |

|

RDT&E |

$1,262.0 |

$1,262.0 |

$1,262.0 |

$1,262.0 |

|||||

|

F-22 mods |

Proc. |

$259.7 |

$259.7 |

$259.7 |

$259.7 |

||||

|

RDT&E |

$603.6 |

$583.9 |

$603.6 |

$588.5 |

|||||

|

F-15 mods |

Proc. |

$695.8 |

$763.0 |

$695.8 |

$756.5 |

||||

|

RDT&E |

$330.0 |

$380.0 |

$330.0 |

$338.6 |

|||||

|

F-16 mods |

Proc. |

$324.3 |

$324.3 |

$324.3 |

$324.3 |

||||

|

RDT&E |

$191.6 |

$191.6 |

$191.6 |

$191.6 |

|||||

|

A-10 mods |

Proc. |

$109.1 |

$174.1 |

$174.1 |

$174.1 |

||||

|

RDT&E |

$26.7 |

$26.7 |

$26.7 |

$26.7 |

|||||

|

OA-X light attack plane (IF10954) |

Proc. |

$450.0 |

$300.0 |

||||||

|

RDT&E |

|||||||||

|

Unmanned Aerial Systems |

|||||||||

|

RQ-4 Global Hawk |

Proc. |

3 |

$699.3 |

4 |

$780.3 |

3 |

$699.3 |

4 |

$780.3 |

|

RDT&E |

$507.5 |

$494.7 |

$507.5 |

$507.5 |

|||||

|

MQ-9 Reaper |

Proc. |

29 |

$773.6 |

22 |

$623.7 |

35 |

$893.6 |

31 |

$819.6 |

|

RDT&E |

$138.2 |

$138.2 |

$138.2 |

$138.2 |

|||||

|

MQ-25 Stingray |

Proc. |

||||||||

|

RDT&E |

$683.9 |

$567.0 |

$683.9 |

$567.0 |

|||||

|

Combat Support and Transport Aircraft |

|||||||||

|

KC-46 tanker (RL34398) |

Proc. |

15 |

$2,559.9 |

12 |

$2,010.9 |

14 |

$2,312.0 |

15 |

$2,351.5 |

|

RDT&E |

$88.2 |

$88.2 |

$88.2 |

$83.2 |

|||||

|

Air Force One replacement |

Proc. |

||||||||

|

RDT&E |

$673.0 |

$673.0 |

$673.0 |

$673.0 |

|||||

|

VH-92 presidential helicopter (RS22103) |

Proc. |

6 |

$649.0 |

6 |

$649.0 |

6 |

$649.0 |

6 |

$649.0 |

|

RDT&E |

$245.1 |

$245.1 |

$245.1 |

$245.1 |

|||||

|

C-130, new aircraft only (R43618) |

Proc. |

10 |

$1,523.9 |

10 |

$1,423.9 |

10 |

$1,523.9 |

10 |

$1,473.7 |

|

RDT&E |

$121.4 |

$121.4 |

$121.4 |

$121.4 |

|||||

|

P-8 Poseidon |

Proc. |

10 |

$2,055.0 |

10 |

$2,029.0 |

10 |

$2,055.0 |

10 |

$2,030.0 |

|

RDT&E |

$197.7 |

$197.7 |

$197.7 |

$197.7 |

|||||

|

E-2D Advanced Hawkeye |

Proc. |

4 |

$983.4 |

4 |

$967.1 |

5 |

$1,158.4 |

5 |

$1,144.9 |

|

RDT&E |

$223.6 |

$215.6 |

$223.6 |

$213.6 |

|||||

|

JSTARS replacement aircraft |

Proc. |

||||||||

|

RDT&E |

$623.0 |

$50.0 |

$30.0 |

||||||

|

Rotary-wing and Tilt-rotor Aircraft |

|||||||||

|

AH-64 Apache and mods, new aircraft and remanufactured aircraft |

Proc. |

60 |

$1,376.1 |

60 |

$1,376.1 |

60 |

$1,376.1 |

66 |

$1,544.1 |

|

RDT&E |

$31.0 |

$31.0 |

$31.0 |

$31.0 |

|||||

|

UH-60 Black Hawk, new aircraft and upgrades |

Proc. |

68 |

$1,262.3 |

73 |

$1,347.3 |

68 |

$1,262.3 |

73 |

$1,347.3 |

|

RDT&E |

$35.2 |

$35.2 |

$35.2 |

$35.2 |

|||||

|

CH-47 Chinook, new and remanufactured aircraft |

Proc. |

8 |

$156.3 |

8 |

$156.3 |

8 |

$156.3 |

8 |

$156.3 |

|

RDT&E |

$157.8 |

$157.8 |

$157.8 |

$155.1 |

|||||

|

CH-53K |

Proc. |

8 |

$1,274.9 |

8 |

$1,250.9 |

8 |

$1,274.9 |

8 |

$1,229.5 |

|

RDT&E |

$326.9 |

$326.9 |

$326.9 |

$326.9 |

|||||

|

UH-1/AH-1, new aircraft and upgrades |

Proc. |

25 |

$820.8 |

25 |

$820.8 |

25 |

$820.8 |

25 |

$820.8 |

|

RDT&E |

$58.1 |

$58.1 |

$58.1 |

$58.1 |

|||||

|

V-22 Osprey and mods (RL31384) |

Proc. |

7 |

$1,118.5 |

7 |

$1,118.5 |

7 |

$1,118.5 |

7 |

$1,093.4 |

|

RDT&E |

$161.6 |

$161.6 |

$161.6 |

$161.6 |

|||||

|

Search and Rescue Helicopter |

Proc. |

10 |

$680.2 |

10 |

$680.2 |

10 |

$680.2 |

10 |

$680.2 |

|

RDT&E |

$457.7 |

$457.7 |

$457.7 |

$457.7 |

|||||

Source: CRS analysis of DOD budget documentation and H.Rept. 115-874, conference report to accompany H.R.5515, John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 (P.L. 115-232).

Note: Full citations of CRS products are listed in the Appendix.

Fighter and Attack Aircraft

The budget request included $8.8 billion for the procurement of 77 F-35 Lightning II aircraft as part of the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program. The quantity includes 48 Air Force F-35As, equipped for conventional runway operations, 20 Marine Corps F-35Bs, equipped for short takeoff and vertical landing (STOVL) operations; and nine Navy F-35Cs, equipped for aircraft carrier operations.107

The House version of the bill generally would have supported the Administration's request, while the Senate amendment would have cut funding associated with two aircraft—one F-35A and one F-35C—due to "program realignment." While the act authorizes $133 million (1%) less procurement funding than requested, it authorizes the requested quantity of F-35 aircraft.

The act includes a provision (Section 1282) limiting the delivery of any F-35s to Turkey (which plans to buy 100 of the aircraft) until the Secretary of Defense submits a report to congressional committees on the Turkish government's plan to purchase the S-400 air and missile defense system from Russia.108 The report was to include "an assessment of impacts on other United States weapon systems and platforms operated jointly with the Republic of Turkey," including the F-35, Patriot surface-to-air missile system, CH-47 Chinook heavy-lift helicopter, AH-64 Apache helicopter, UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter, and F-16 Fighting Falcon fighter jet.

To compensate for the slower-than-planned fielding of the F-35 aircraft, the budget request included funds to mitigate a shortfall in the Navy's fleet of strike fighters by buying new F/A-18s and upgrading planes of that type already in service. The House version of the bill and the Senate amendment would have supported the request. The act generally supports the request, authorizing $56 million (3%) less than the $2 billion requested for 24 F/A-18s and $18 million (1%) more than the $1.5 billion requested to modify existing versions of the aircraft.

Section 127 of the act requires the Secretary of the Navy to work to modify the F/A-18 aircraft "to reduce the occurrence of, and mitigate the risk posed by, physiological episodes affecting crewmembers of aircraft," by replacing the cockpit altimeter, upgrading the onboard oxygen system generation system, redesigning aircraft life support systems, and installing equipment associated with improved physiological monitoring and alert systems.

The act authorizes $300 million in procurement funding not included in the President's request to begin buying an unspecified number of new OA-X light attack aircraft.109 Section 246 of the act requires the Secretary of the Air Force to submit to the congressional defense committees a report on the service's OA-X "experiment" and how the program incorporates partner nation requirements.

The act authorizes $201 million for modifications to the A-10 Thunderbolt II ground-attack aircraft known as the Warthog, including $65 million more than the President's request for additional wing replacements.

Tanker Aircraft