The Defense Budget and the Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions

Enacted on August 2, 2011, the Budget Control Act of 2011 as amended (P.L. 112-25, P.L. 112-240, P.L. 113-67, P.L. 114-74, P.L. 115-123, and P.L. 116-37) sets limits on defense and nondefense discretionary spending. As part of an agreement to increase the statutory limit on public debt, the BCA aimed to reduce annual federal budget deficits by a total of at least $2.1 trillion from FY2012 through FY2021, with approximately half of the savings to come from defense.

The spending limits (or caps) apply separately to defense and nondefense discretionary budget authority. Budget authority is provided by law to a federal agency to obligate money for goods and services. The caps are enforced by a mechanism called sequestration. Sequestration automatically cancels previously enacted appropriations (a form of budget authority) by an amount necessary to reach prespecified levels. The defense spending limits apply to national defense (budget function 050) but not to funding designated for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) or as emergency requirements.

Some defense policymakers and officials argue the BCA spending restrictions impede the Department of Defense’s (DOD’s) ability to adequately resource military personnel and equipment for operations and other national security requirements. Others argue the limits are necessary to curb rising deficits and debt.

Congress has repeatedly amended the legislation to raise the spending limits with two-year budget agreements. Most recently, on August 2, 2019, President Donald Trump signed into law the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 (BBA 2019; P.L. 116-37). The bill amended the BCA to increase defense discretionary spending caps by the largest amount to date—by $90.3 billion, to $666.5 billion in FY2020; and by $81.3 billion, to $671.5 billion in FY2021. BBA 2019 also specified nonbinding Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism (OCO/GWOT) defense funding targets of $71.5 billion for FY2020 and $69 billion for FY2021.

The annual federal budget deficit decreased from $1.1 trillion (6.7% of Gross Domestic Product) in FY2012 to $779 billion (3.9% of GDP) in FY2018, but is projected to increase to $1 trillion (4.5% of GDP) in FY2021. Meanwhile, federal debt held by the public has increased from $11.3 trillion (70.3% of GDP) in FY2012 to $15.7 trillion (77.8% of GDP) in FY2018, and is projected to further increase to $18.8 trillion (82.4% of GDP) in FY2021.

The Defense Budget and the Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Background

- Frequently Asked Questions

- What is the debate over defense spending caps?

- How does the BCA affect defense spending?

- What are the BCA limits on defense discretionary spending?

- How did the Bipartisan Budget of Act of 2019 change BCA defense caps?

- Does the BCA limit Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) funding?

- How have the defense spending caps changed over time?

- What is sequestration?

- Do BCA caps apply to the Department of Defense (DOD)?

- Can the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) trigger sequestration?

- How has defense discretionary spending changed since enactment of the BCA?

Figures

Summary

Enacted on August 2, 2011, the Budget Control Act of 2011 as amended (P.L. 112-25, P.L. 112-240, P.L. 113-67, P.L. 114-74, P.L. 115-123, and P.L. 116-37) sets limits on defense and nondefense discretionary spending. As part of an agreement to increase the statutory limit on public debt, the BCA aimed to reduce annual federal budget deficits by a total of at least $2.1 trillion from FY2012 through FY2021, with approximately half of the savings to come from defense.

The spending limits (or caps) apply separately to defense and nondefense discretionary budget authority. Budget authority is provided by law to a federal agency to obligate money for goods and services. The caps are enforced by a mechanism called sequestration. Sequestration automatically cancels previously enacted appropriations (a form of budget authority) by an amount necessary to reach prespecified levels. The defense spending limits apply to national defense (budget function 050) but not to funding designated for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) or as emergency requirements.

Some defense policymakers and officials argue the BCA spending restrictions impede the Department of Defense's (DOD's) ability to adequately resource military personnel and equipment for operations and other national security requirements. Others argue the limits are necessary to curb rising deficits and debt.

Congress has repeatedly amended the legislation to raise the spending limits with two-year budget agreements. Most recently, on August 2, 2019, President Donald Trump signed into law the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 (BBA 2019; P.L. 116-37). The bill amended the BCA to increase defense discretionary spending caps by the largest amount to date—by $90.3 billion, to $666.5 billion in FY2020; and by $81.3 billion, to $671.5 billion in FY2021. BBA 2019 also specified nonbinding Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism (OCO/GWOT) defense funding targets of $71.5 billion for FY2020 and $69 billion for FY2021.

The annual federal budget deficit decreased from $1.1 trillion (6.7% of Gross Domestic Product) in FY2012 to $779 billion (3.9% of GDP) in FY2018, but is projected to increase to $1 trillion (4.5% of GDP) in FY2021. Meanwhile, federal debt held by the public has increased from $11.3 trillion (70.3% of GDP) in FY2012 to $15.7 trillion (77.8% of GDP) in FY2018, and is projected to further increase to $18.8 trillion (82.4% of GDP) in FY2021.

Background

National defense is one of 20 major functions used by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to organize budget data―and the largest in terms of discretionary spending. The national defense budget function (identified by the numerical notation 050) comprises three subfunctions: Department of Defense (DOD)-Military (051); atomic energy defense activities primarily of the Department of Energy (DOE) (053); and other defense-related activities (054) such as Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) counterintelligence activities.1 Discretionary spending is, for the most part, provided by annual appropriations bills and the focus of Congress's efforts to fund the federal government. By contrast, mandatory (or direct) spending, which includes entitlement programs such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, is generally governed by existing statutory criteria.2

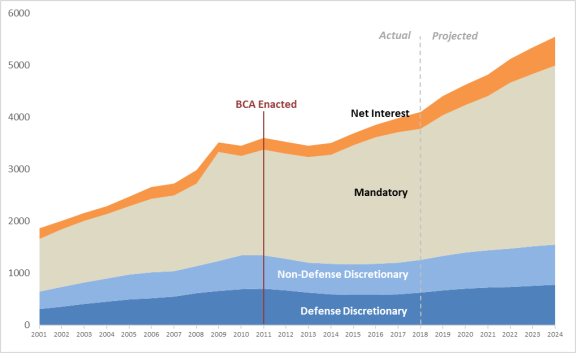

Since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, outlays—money spent by a federal agency from funds provided by Congress—for defense discretionary programs in nominal dollars (not adjusted for inflation) have more than doubled from $306 billion in FY2001 to $623 billion in FY2018.3 Defense discretionary outlays are projected to reach $721 billion in FY2021.4 Yet as a percentage of total federal outlays, defense discretionary outlays declined over this period from 16.4% in FY2001 to 15.2% in FY2018. They are projected to further decrease to 14.9% in FY2021, as mandatory programs and net interest consume a larger share of the total (see Figure 1).5

Between FY2009 and FY2012, annual federal budget deficits topped $1 trillion. In FY2009, the deficit reached 9.8% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the highest level since World War II.6 The deficits were attributable in part to reduced tax revenues from the 2007-2009 recession and increased spending from the economic stimulus package known as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5).7 As part of an agreement to increase the statutory limit on public debt, the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25) aimed to reduce annual federal budget deficits by a total of at least $2.1 trillion from FY2012 through FY2021, with approximately half of the savings to come from defense.

Congress has previously used budget enforcement mechanisms—such as a statutory limit on annual appropriations for discretionary activities—to mandate a specific budgetary policy or to obtain a fiscal objective. The BCA amended the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 (P.L. 99-177) by reinstating spending limits on discretionary budget authority beginning in FY2012.8 Congress provides budget authority by law to federal agencies to obligate money for goods and services. Congress does not directly control outlays, which occur when obligations are liquidated, primarily through issuing checks, transferring funds, or disbursing cash.9 For spending limits in FY2012 and FY2013, the BCA originally specified separate "security" and "nonsecurity" categories. The security category was broad in scope and included budget accounts of the Department of Defense (DOD), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the National Nuclear Security Administration, the intelligence community management account, and international affairs (budget function 150).10 After the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction did not reach a deficit-reduction deal and triggered backup budgetary enforcement measures of steeper reductions to the initial BCA caps beginning in FY2013, the "security" category was revised to the narrower "defense" category, which included only discretionary programs in the national defense budget function (050).

|

Figure 1. Outlays by Budget Enforcement Act Category, FY2001-FY2024 (in billions of dollars) |

|

|

Source: Office of Management and Budget, Table 8.1, Outlays by Budget Enforcement Act Category: 1962-2024, at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/historical-tables/, and Congressional Budget Office, 10-Year Budget Projections, Table 1-1, CBO's Baseline Budget Projections, by Category, and Table 1-5, CBO's Baseline Projections of Discretionary Spending, Adjusted to Exclude the Effects of Timing Shifts, August 2019, at https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#3. Notes: Actual figures from FY2001 to FY2018 from OMB; projections from FY2019 to FY2024 from CBO. Outlays include funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO). |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the debate over defense spending caps?

The discretionary spending limits established by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25) have been a point of contention since enactment.

Critics of the legislation argue reductions to defense investments "present a grave and growing danger to our national security."11 They also note the spending restrictions disproportionately affect defense programs, which in FY2017 accounted for 16% of budgetary resources (excluding net interest payments) and 49% of BCA spending reductions.12 The late Senator John McCain and Representative Mac Thornberry, the former chairs of the Senate and House Armed Services Committees, respectively, have said the law has "failed."13 In 2019, Representative Adam Smith, chairman of HASC, introduced the Relief from Sequestration Act of 2019 (H.R. 2110) "to repeal the automatic cuts in both discretionary and mandatory spending triggered by the 2011 Budget Control Act's sequestration."14 Former Defense Secretary James Mattis has said: "Let me be clear: As hard as the last 16 years of war have been on our military, no enemy in the field has done as much to harm the readiness of U.S. military than the combined impact of the BCA's defense spending caps, worsened by operating for 10 of the last 11 years under continuing resolutions of varied and unpredictable duration."

Proponents of BCA argue its limits are necessary in light of recurring deficits and growing federal debt.15 Representative Mark Meadows, a former chairman of the House Freedom Caucus who has repeatedly opposed budget deals to raise the spending caps, has said, "I want to fund our military, but at what cost? Should we bankrupt our country in the process?"16 Lawrence Korb, an Assistant Secretary of Defense during the Reagan Administration, said the BCA has "affected defense capability somewhat," but noted Congress has blunted the law's impact by increasing the caps and by exempting from the restrictions funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), allowing the Department of Defense (DOD) to use such funds for regular, or base, budget activities.17

Attempts to fully repeal BCA have not succeeded.18 Lawmakers have enacted increases to the defense and nondefense sending caps for each year from FY2013 to FY2021.19

How does the BCA affect defense spending?

The Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25) contained several measures intended to reduce deficits by a total of at least $2.1 trillion from FY2012 to FY2021, with approximately half of the savings to come from defense.20 A key component of the legislation set limits on discretionary budget authority to reduce projected spending by $0.9 trillion over the period. As backup budgetary enforcement measures, the BCA also required at least $1.2 trillion in additional savings if a congressionally mandated panel, the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction, did not reach agreement on a deficit-reduction plan. The spending limits (or caps) apply separately to defense and nondefense discretionary budget authority.21 The caps are enforced by a mechanism called sequestration, which automatically cancels previously enacted spending by an amount necessary to reach prespecified levels.22 The defense discretionary spending limits apply to national defense (budget function 050) but not to funding designated for Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism (OCO/GWOT) or as emergency requirements.23 Because the committee did not agree on a plan to reduce the deficit, the BCA required steeper reductions to the discretionary spending limits each year from FY2013 through FY2021 (see Table 1).24

What are the BCA limits on defense discretionary spending?

Congress has repeatedly amended the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25) to revise the discretionary spending limits, mostly recently with the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 (P.L. 116-37).25 Table 1 depicts the limits as amended (in bold and shaded) for the defense category, which includes discretionary programs of the national defense budget function (050) and excludes funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), emergencies, and certain other activities.26

Table 1. BCA Limits on National Defense (050) Discretionary Base Budget Authority

(in billions of dollars)

|

National Defense (050) |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

Budget Control Act of 2011 |

555 |

546 |

556 |

566 |

577 |

590 |

603 |

616 |

630 |

644 |

|

BCA after automatic revision |

555 |

492 |

501 |

511 |

522 |

535 |

548 |

561 |

575 |

589 |

|

American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 |

555 |

518 |

497 |

511 |

522 |

535 |

548 |

561 |

575 |

589 |

|

Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 |

555 |

518 |

520 |

521 |

523 |

536 |

549 |

562 |

576 |

590 |

|

Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 |

555 |

518 |

520 |

521 |

548 |

551 |

549 |

562 |

576 |

590 |

|

Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 |

555 |

518 |

520 |

521 |

548 |

551 |

629 |

647 |

576 |

590 |

|

Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 |

555 |

518 |

520 |

521 |

548 |

551 |

629 |

647 |

667 |

672 |

Sources: Congressional Budget Office, letter to the Honorable John A. Boehner and Honorable Harry Reid estimating the impact on the deficit of the Budget Control Act of 2011, August 2011; CBO, Final Sequestration Report for Fiscal Year 2012, January 2012; CBO, Final Sequestration Report for Fiscal Year 2013, March 2013; CBO, Final Sequestration Report for Fiscal Year 2014, January 2014; CBO, Final Sequestration Report for Fiscal Year 2016, December 2015, CBO, Sequestration Update Report: August 2017, August 2017; CBO, Cost Estimate for Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, February 2018, CBO, Sequestration Update Report: August 2019; P.L. 116-37.

Notes: Bold and shaded figures indicate statutory changes. Figures do not include funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), emergencies, and certain other activities. The BCA as amended provided for "security" and "nonsecurity" categories in FY2012 and FY2013: italicized figures denote CRS estimates of budget authority for defense and nondefense categories in those years. Small changes in budget authority beginning in FY2016 are caused by adjustments in the annual proportional allocations of automatic enforcement measures as calculated by OMB: for more information on these adjustments, see CBO, Estimated Impact of Automatic Budget Enforcement Procedures Specified in the Budget Control Act, September 2011. This table is an abridged version of one that originally appeared in CRS Report R44874, The Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions, by Grant A. Driessen and Megan S. Lynch.

How did the Bipartisan Budget of Act of 2019 change BCA defense caps?

On August 2, 2019, President Trump signed the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 (BBA 2019; P.L. 116-37). BBA 2019 raised discretionary spending limits set by the BCA for FY2020 and FY2021—the final two years the BCA discretionary caps are in effect. The act also extended mandatory spending reductions through FY2029 and suspended the statutory debt limit until August 1, 2021.27

BBA 2019 raised the federal government's discretionary spending limits, as set by the BCA, from $1.119 trillion for FY2020 and $1.145 trillion for FY2021 to $1.288 trillion for FY2020 and to $1.298 trillion for FY2021. The act increased FY2020 defense discretionary funding levels (excluding OCO) by the largest amount to date—$90.3 billion in FY2020, from $576.2 billion to $666.5 billion—and nondefense funding by $78.3 billion, from $543.2 billion to $621.5 billion. The FY2021 adjustments are slightly lower, with an increase of $81.3 billion in defense discretionary funding, from $590.2 billion to $671.5 billion, and an increase of $71.6 billion for nondefense funding, from $554.9 billion to $626.5 billion.

Does the BCA limit Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) funding?

The BCA stipulates that certain discretionary funding, such as appropriations designated for Overseas Contingency Operations/Global War on Terrorism (OCO/GWOT) or as emergency requirements, allow for an upward adjustment of the discretionary limits. OCO funding is therefore described as "exempt" from the discretionary spending limits. The BCA does not define what constitutes OCO funding. Instead, the BCA includes a requirement that Congress designate OCO spending on an account-by-account basis, and that the President subsequently designate the spending as such. Further, the BCA does not limit the level or amount of spending that may be designated for OCO.28

Debate over what should constitute OCO or emergency activities and expenses has shifted over time, reflecting differing viewpoints about the extent, nature, and duration of U.S. military operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere.29 Recently, Congress and the President have designated funding for OCO that includes activities previously in the regular, or base, DOD budget.30 By designating OCO funding for ongoing activities not directly related to contingency operations, Congress and the President can effectively increase topline defense, foreign affairs, and other related discretionary spending, without triggering sequestration.31

Like the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015; P.L. 114-74), BBA 2019 also established targets for OCO/GWOT funding for the next two fiscal years.32 BBA 2019 set the defense OCO/GWOT target at $71.5 billion for FY2020 and $69 billion for FY2021, and the nondefense OCO/GWOT target at $8 billion for both FY2020 and FY2021.33 (See Table 2.)

|

Category |

FY2020 |

FY2021 |

|

Defense |

71,500 |

69,000 |

|

Nondefense |

8,000 |

8,000 |

|

Total |

79,500 |

77,000 |

Source: Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 (BBA 2019; P.L. 116-37).

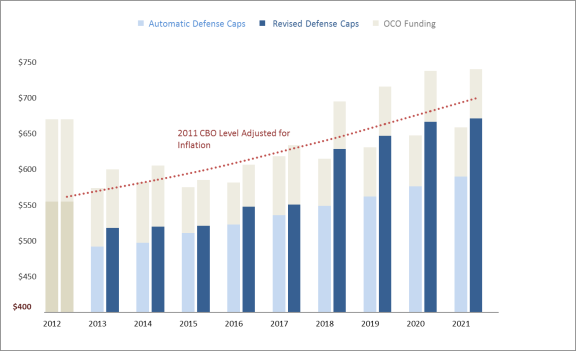

How have the defense spending caps changed over time?

To date, CRS estimates Congress has amended the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25) to increase defense discretionary spending limits by a total of approximately $435 billion (thus lowering their deficit-reduction effect by a corresponding amount). The increases over previous caps break down as follows:

- $26 billion (5%) in FY2013;

- $23 billion (5%) in FY2014;

- $10 billion (2%) in FY2015;

- $25 billion (5%) in FY2016;

- $15 billion (3%) in FY2017;

- $80 billion (15%) in FY2018;

- $85 billion (15%) in FY2019;

- $90 billion (16%) in FY2020; and

- $81 billion (14%) in FY2021.34

|

Figure 2. Changes to BCA Limits on National Defense (050) Discretionary Budget Authority, FY2012-FY2021 (in billions of dollars) |

|

|

Sources: Automatic and revised BCA limits from Table 1; Overseas Contingency Operations funding from Department of Defense, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Comptroller), National Defense Budget Estimates for FY2020, Table 2-1: Base Budget, War Funding and Supplementals by Military Department, by P.L. Title (FY2001-FY2019), May 2019; and P.L. 116-37; 2011 CBO level from Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Outlook: An Update, Table 1-6: Illustrative Paths for Discretionary Budget Authority Subject to the Caps Set in the Budget Control Act of 2011, August 2011. Notes: Defense caps reflect levels established under automatic revision of the BCA; revised defense caps reflect levels established under American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA; P.L. 112-240), Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (BBA 2013; P.L. 113-67), Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015; P.L. 114-74), Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018; P.L. 115-123), and Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 (BBA 2019; P.L. 116-37). OCO funding reflects DOD levels and does not include appropriations for hurricane relief, avian flu and Ebola assistance, Iron Dome, missile defeat, and other purposes. CBO baseline excludes funding for operations in Afghanistan and Iraq and for similar activities. |

In 2011, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated discretionary budget authority for the national defense budget function (050), excluding funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), would total $6.26 trillion over the 10-year period from FY2012 through FY2021, assuming the 2011 level would grow at the rate of inflation (see Figure 2).35 Based on this level, CRS estimates the BCA would have decreased projected defense discretionary base budget authority by approximately $0.86 trillion (14%) to $5.39 trillion over the decade—and the caps as amended would reduce projected defense discretionary base budget authority by approximately $0.43 trillion (7%) to $5.83 trillion over the period.36 Note, however, that these figures do not take into account funding for OCO, emergencies, and certain other activities. Defense OCO funding is projected at approximately $0.77 trillion over the same period, and DOD has acknowledged using OCO funding for base budget activities.

What is sequestration?

Sequestration provides for the enforcement of budgetary limits established in law through the automatic cancellation of previously enacted spending, making largely across-the-board reductions to nonexempt programs, activities, and accounts. A sequester is implemented through a sequestration order issued by the President as required by law. The purpose of sequestration is to deter enactment of legislation violating the spending limits or, in the event that such legislation is enacted violating these spending limits, to automatically reduce spending to the limits specified in law. Each statutory limit—defense and nondefense—is separately enforced so that the breach of the limit for one category is enforced by a sequester of resources only within that category.37

The absence of legislation to reduce the federal budget deficit by at least $1.2 trillion triggered sequestration in 2013. In accordance with the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25), then-President Barack Obama ordered the sequestration of budgetary resources across nonexempt federal government accounts on March 1, 2013—five months into the fiscal year. DOD was required to apply a $37 billion sequester to $528 billion in available (subfunction 051) budgetary resources—a reduction of 7%.

Do BCA caps apply to the Department of Defense (DOD)?

Department of Defense (DOD)-Military activities (budget subfunction 051) historically constitute approximately 95% of the national defense budget (function 050).38 Although the BCA does not establish limits on subfunctions (051, 053, and 054), the BCA limits on national defense have, in practice, been proportionally applied to subfunctions. CRS estimates the BCA limits on DOD-Military base budget activities at approximately $638 billion in FY2020 and $643 billion in FY2021.

Can the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) trigger sequestration?

Legislation authorizing discretionary appropriations, such as the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), does not provide budget authority and therefore cannot trigger sequestration for violating discretionary spending limits.39 A sequester will occur only if either the defense or nondefense discretionary spending limits are exceeded in enacted appropriations bills.40

How has defense discretionary spending changed since enactment of the BCA?

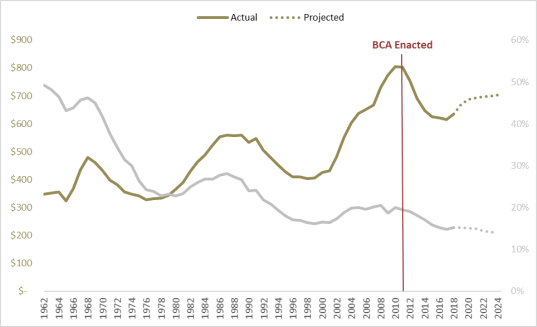

Nominal defense discretionary outlays, including funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), decreased from $671 billion in FY2012 to $623 billion in FY2018, a decline of $48 billion (7%). They are projected to reach $721 billion in FY2021, an increase of $51 billion (8%) from FY2012.41 Adjusting for inflation (in constant FY2019 dollars), defense discretionary outlays peaked at $806 billion in FY2010 during the height of the U.S.-led wars in Iraq and Afghanistan (see Figure 3).42 Following enactment of the BCA, defense discretionary outlays decreased from $755 billion in FY2012 to $635 billion in FY2018, a decline of $119 billion (16%) in inflation-adjusted dollars. They are projected to reach $693 billion in FY2021, $62 billion (8%) less than the FY2012 level in inflation-adjusted dollars. The figure also shows defense discretionary outlays as a percentage of all federal outlays. Over the past half century, federal outlays devoted to defense discretionary programs have trended downward from nearly half (49%) of total outlays in FY1962 during the Vietnam War, to 19% in FY2012 after enactment of the BCA, to 15% in FY2018. They are projected to remain relatively flat through FY2021.43

|

Figure 3. National Defense (050) Discretionary Outlays, FY1962-FY2024 (in billions of FY2019 dollars and as percentage of total federal outlays) |

|

|

Source: Office of Management and Budget, Historical Tables, Table 8.1, Outlays by Budget Enforcement Act Category: 1962-2024, and Table 10.1, Gross Domestic Product and Deflators Used in the Historical Tables: 1940-2024, at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/historical-tables/, and Congressional Budget Office, 10-Year Budget Projections, Table 1-5, CBO's Baseline Projections of Discretionary Spending, Adjusted to Exclude the Effects of Timing Shifts, at https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#3. Notes: Outlays include funding designated for Overseas Contingency Operations and other adjustments to the discretionary budget authority limits established by the BCA as amended. Amounts adjusted for inflation using GDP (Chained) Price Index from OMB Table 10.1. |

Similarly, defense discretionary outlays as a share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) have trended downward, from 9.2% of GDP in FY1968, to 4.2% of GDP in FY2012 after enactment of the BCA, to 3.1% of GDP in FY2018. By FY2021—the last year of the BCA discretionary caps—CBO projects defense discretionary outlays at 3.2% of GDP.44

The deficit-reduction effects of the BCA have been offset by other factors affecting the federal budget.45 The federal budget deficit decreased from $1.1 trillion (6.7% of Gross Domestic Product) in FY2012 to $779 billion (3.9% of GDP) in FY2018, but is projected to increase to $1 trillion (4.5% of GDP) in FY2021.46 Over the same period, federal debt held by the public has increased from $11.3 trillion (70.3% of GDP) in FY2012 to $15.7 trillion (77.8% of GDP) in FY2018 and is projected to further increase to $18.8 trillion (82.4% of GDP) in FY2021.47

Author Contact Information

Acknowledgments

This is an update to a report originally authored by Lynn M. Williams, former CRS Specialist in Defense Readiness and Infrastructure. It references research previously compiled by Amy Belasco, former CRS Specialist in U.S. Defense Policy and Budget; Grant A. Driessen, CRS Analyst in Public Finance; and Megan S. Lynch, CRS Specialist on Congress and the Legislative Process. Jennifer M. Roscoe, Research Assistant, helped compile the graphics.

Footnotes

| 1. |

See CRS In Focus IF10618, Defense Primer: The National Defense Budget Function (050), by Christopher T. Mann. |

| 2. |

See CRS Report 98-721, Introduction to the Federal Budget Process, coordinated by James V. Saturno. |

| 3. |

Office of Management and Budget, Historical Tables, Table 8.7, Outlays for Discretionary Programs: 1962-2024, at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/historical-tables/. |

| 4. |

Congressional Budget Office, 10-Year Budget Projections, Table 1-5, CBO's Baseline Projections of Discretionary Spending, Adjusted to Exclude the Effects of Timing Shifts, August 2019, at https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#3. |

| 5. |

Office of Management and Budget, Historical Tables, Table 8.1, Outlays by Budget Enforcement Act Category: 1962-2024, at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/historical-tables/; and Congressional Budget Office, 10-Year Budget Projections, Table 1-1, CBO's Baseline Budget Projections, by Category, and Table 1-5, CBO's Baseline Projections of Discretionary Spending, Adjusted to Exclude the Effects of Timing Shifts, August 2019, at https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#3. For more information on mandatory spending trends, see CRS Report R44763, Present Trends and the Evolution of Mandatory Spending, by D. Andrew Austin. |

| 6. |

Office of Management and Budget, Historical Tables, Table 1.3, Summary of Receipts, Outlays, and Surpluses or Deficits (-) in Current Dollars, Constant (FY 2012) Dollars, and as Percentages of GDP: 1940-2024, at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/historical-tables/. |

| 7. |

CRS Report R44874, The Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions, by Grant A. Driessen and Megan S. Lynch. |

| 8. |

Office of Management and Budget, Final Sequestration Report to the President and Congress for Fiscal Year 2018, April 6, 2018, at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/2018_final_sequestration_report_april_2018_potus.pdf. |

| 9. |

See CRS Report 98-721, Introduction to the Federal Budget Process, coordinated by James V. Saturno. |

| 10. |

Office of Management and Budget, Final Sequestration Report to the President and Congress for Fiscal Year 2012, January 18, 2012, at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/legislative_reports/sequestration/sequestration_final_jan2012.pdf. |

| 11. |

Open letter from eighty-five national security experts and former government officials: Elliot Abrams, David Adesnik, and Michael Auslin, et al. to John Boehner, then-speaker of the House, and Mitch McConnell, Senate Majority Leader, et al., February 24, 2015. Document on file with the author. |

| 12. |

Frederico Bartels, "America's defense budget is yet again held hostage by Congress," The Hill, November 2, 2017, at http://thehill.com/opinion/national-security/358385-congress-needs-to-do-its-job-and-properly-fund-americas-defense. |

| 13. |

Former Sen. John McCain, "Restoring American Power: Recommendations for the FY2018-FY2022 Defense Budget," white paper, January 16, 2017; and Ben Werner, "Thornberry: Budget Control Act Limits on Defense Spending Could End Soon," USNI News, September 6, 2017, at https://news.usni.org/2017/09/06/thornberry-budget-control-act-limits-defense-spending-end-soon. |

| 14. |

The legislation was introduced and referred to the House Budget Committee on April 4, 2019. See also Adam Smith, "Chairman Smith Reintroduces Legislation to End Sequestration," press release, April 4, 2019, at https://adamsmith.house.gov/2019/4/chairman-smith-reintroduces-legislation-to-end-sequestration. For more on sequestration, see the "What is sequestration?" section later in this report. |

| 15. |

See, for example, Michael Shindler, "Don't Let Defense Wreck the Budget," Real Clear Defense, February 23, 2017, at https://www.realcleardefense.com/articles/2017/02/23/dont_let_defense_wreck_the_budget_110857.html. For more information on deficits and debt, see CRS Report R44383, Deficits, Debt, and the Economy: An Introduction, by Grant A. Driessen. |

| 16. |

Rep. Mark Meadows, "Rep. Meadows' Statement on Budget Agreement," press release, February 9, 2018, at https://meadows.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=815. Final House roll call vote results for the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 at http://clerk.house.gov/evs/2019/roll511.xml. |

| 17. |

Lawrence J. Korb, "Trump's Defense Budget," Center for American Progress, February 28, 2018, at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/security/news/2018/02/28/447248/trumps-defense-budget/. |

| 18. |

Rep. Mike Turner, "Trump Calls for Repeal of Sequestration; Turner: Repeal Gains Groundswell of Support," press release, March 1, 2017, https://turner.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/trump-calls-for-repeal-of-sequestration-turner-repeal-gains-groundswell. |

| 19. |

The BCA was amended by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA; P.L. 112-240), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (BBA 2013; P.L. 113-67, referred to as the Murray-Ryan agreement), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015; P.L. 114-74), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018; P.L. 115-123), and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 (BBA 2019; P.L. 116-37). For more information, see CRS Insight IN11148, The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019: Changes to the BCA and Debt Limit, by Grant A. Driessen and Megan S. Lynch. |

| 20. |

Congressional Budget Office, Letter from then-Director Douglas W. Elmendorf to then-Speaker of the House John Boehner and then-Majority Leader of the Senate Harry Reid, "CBO Estimate of the Impact on the Deficit of the Budget Control Act of 2011," August 1, 2011, at http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/123xx/doc12357/budgetcontrolactaug1.pdf. |

| 21. |

Legislation amending the BCA included equal increases to defense and nondefense discretionary spending caps until the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123), which included a larger increase to defense than nondefense. For more on the so-called parity principle, see CRS In Focus IF10657, Budgetary Effects of the BCA as Amended: The "Parity Principle", by Grant A. Driessen. For more on the "security" category that predated the "defense" category, see the "Background" section above. |

| 22. |

For more information on sequestration, see CRS Report R42972, Sequestration as a Budget Enforcement Process: Frequently Asked Questions, by Megan S. Lynch. |

| 23. |

For more information on the national defense budget function, see the Background section above. For more information on OCO, see CRS Report R44519, Overseas Contingency Operations Funding: Background and Status, by Brendan W. McGarry and Emily M. Morgenstern. |

| 24. |

These automatic reductions to the original BCA limits are often referred to as sequestration but technically are not because Congress can allocate funding within the caps. |

| 25. |

The BCA was amended by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA; P.L. 112-240), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (BBA 2013; P.L. 113-67, referred to as the Murray-Ryan agreement), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015; P.L. 114-74), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018; P.L. 115-123), and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 (BBA 2019; P.L. 116-37). |

| 26. |

For more on the "security" category that predated the "defense" category, see the "Background" section above. |

| 27. |

For more information on the BBA 2019, see CRS Insight IN11148, The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019: Changes to the BCA and Debt Limit, by Grant A. Driessen and Megan S. Lynch. |

| 28. |

The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-74) established non-binding targets for OCO spending in FY2016 and FY2017. |

| 29. |

For more information on OCO funding, see CRS Report R44519, Overseas Contingency Operations Funding: Background and Status, by Brendan W. McGarry and Emily M. Morgenstern. |

| 30. |

The term base budget is generally used to refer to funding for planned or regularly occurring costs to man, train and equip the military. This is used in contrast to amounts needed to fund contingency operations or DOD response to emergencies or disaster relief. |

| 31. |

Section 1501 of the National Defense Authorization Act for FY2017 (P.L. 114-328) stipulates that certain amounts designated as OCO are to be used for base budget requirements. Such amounts would not be counted against the BCA limits. See also OMB, "Presidential Designation of Funding as an Emergency Requirement: Multiple Accounts in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2017, for the Department of Agriculture, Department of Homeland Security, Department of Housing and Urban Development, Department of the Interior, Department of Transportation, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration," press release, May 2017, at https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/budget/amendments/Emergency%20Funding%20Transmittal%20Package%205.5.17.pdf. |

| 32. |

In FY2017, OCO funding for defense and nondefense exceeded the targets set in BBA 2015. See P.L. 114-74 and Office of Management and Budget, OMB Sequestration Update Report to the President and Congress for Fiscal Year 2020, August 20, 2019, at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Sequestration_Update_August_2019.pdf. |

| 33. |

In the Senate, the use of the OCO/GWOT designation for funds appropriated for FY2020 and FY2021 may be subject to a point of order under section 208 of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 (BBA 2019; P.L. 116-37). If the point of order were made, it would require a vote of three-fifths of all Senators to retain the designation. For more information, see CRS Report R42388, The Congressional Appropriations Process: An Introduction, coordinated by James V. Saturno. |

| 34. |

This figure is based on a CRS estimate of changes to the defense category. The BCA initially provided for "security" and "nonsecurity" categories. See notes to Table 1 and the Background section. |

| 35. |

Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Outlook: An Update, Table 1-6, Illustrative Paths for Discretionary Budget Authority Subject to the Caps Set in the Budget Control Act of 2011, August 2011. Document on file with the author. |

| 36. |

These take into account the small changes in budget authority caused by adjustments in the annual proportional allocations of automatic enforcement measures as calculated by OMB, as well as changes to the FY2014 defense cap from P.L. 112-240. See notes to Table 1. |

| 37. |

This paragraph was contributed by Megan S. Lynch, CRS Specialist on Congress and the Legislative Process. See CRS Report R42972, Sequestration as a Budget Enforcement Process: Frequently Asked Questions, by Megan S. Lynch. |

| 38. |

See CRS In Focus IF10618, Defense Primer: The National Defense Budget Function (050), by Christopher T. Mann. |

| 39. |

For more information on the NDAA, see CRS In Focus IF10516, Defense Primer: Navigating the NDAA, by Brendan W. McGarry and Valerie Heitshusen. |

| 40. |

See CRS Report R42972, Sequestration as a Budget Enforcement Process: Frequently Asked Questions, by Megan S. Lynch. |

| 41. |

Office of Management and Budget, Historical Tables, Table 8.1, Outlays by Budget Enforcement Act Category: 1962-2024, at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/historical-tables/, and Congressional Budget Office, 10-Year Budget Projections, Table 1-5, CBO's Baseline Projections of Discretionary Spending, Adjusted to Exclude the Effects of Timing Shifts, at https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#3. |

| 42. |

Ibid. Amounts adjusted for inflation using GDP (Chained) Price Index from Office of Management and Budget, Historical Tables, Table 10.1, Gross Domestic Product and Deflators Used in the Historical Tables: 1940-2024, at https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/historical-tables/. |

| 43. |

Ibid. |

| 44. |

Office of Management and Budget, Historical Tables, Table 8.4, Outlays by Budget Enforcement Act Category as Percentages of GDP: 1962-2024, and Congressional Budget Office, 10-Year Budget Projections, Table 1-1, CBO's Baseline Budget Projections, by Category, and Table 1-5, CBO's Baseline Projections of Discretionary Spending, Adjusted to Exclude the Effects of Timing Shifts, at https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/budget-economic-data#3. |

| 45. |

For example, the Congressional Budget Office in 2018 increased projected deficits compared to a previous estimate due to tax and spending legislation, including the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (P.L. 115-97), Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123), and the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141). |

| 46. |

Office of Management and Budget, Table 1.3, Summary of Receipts, Outlays, and Surpluses Or Deficits (-) in Current Dollars, Constant (FY2012) Dollars, and as Percentages Of GDP: 1940-2024, and Congressional Budget Office, 10-Year Budget Projections, Table 1-1, CBO's Baseline Budget Projections, by Category, and Table 1-5, CBO's Baseline Projections of Discretionary Spending, Adjusted to Exclude the Effects of Timing Shifts.. |

| 47. |

Office of Management and Budget, Historical Tables, Table 7.1, Federal Debt at the End of Year: 1940–2024, and Congressional Budget Office, 10-Year Budget Projections, Table 1-1, CBO's Baseline Budget Projections, by Category. |