Background

In the past, Congress has used budget enforcement mechanisms—such as a statutory limit on annual appropriations for discretionary activities—to mandate a specific budgetary policy or to obtain a fiscal objective.1 Such discretionary spending limits were first in effect between FY1991 and FY2002, and were reestablished in the Budget Control Act of 2011(BCA/P.L. 112-25).

The BCA contains several measures intended to reduce the budget deficit by $2.1 trillion over the period FY2012-FY2021. A key component of the BCA is the establishment limits on the level of discretionary spending in order to achieve projected savings of approximately $1.0 trillion over that period. These limits are similar to budget enforcement mechanisms used previously by Congress. In addition, the BCA required approximately $1.1 trillion in savings to be generated from a plan developed by the congressionally established, bipartisan, Joint Committee on Deficit Reduction.

The BCA limits apply separately to defense and nondefense discretionary budget authority and are enforced by a mechanism called sequestration.2 Sequestration provides for the automatic cancellation of previously enacted spending to reduce discretionary spending to the limits specified in the BCA. The defense limits apply to the national defense budget (function 050), but do not restrict amounts provided for "emergencies" or "Overseas Contingency Operations."3 Absent enactment of a Joint Committee on Deficit Reduction bill to reduce the deficit by at least $1.2 trillion, the BCA required downward adjustments (or reductions) to the statutory limit on both defense and nondefense spending each year through FY2021. This automatic reduction to the original BCA limits is also referred to as sequestration.

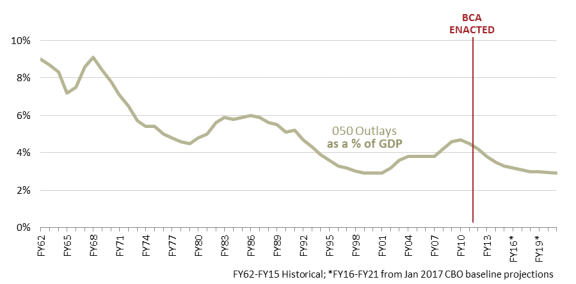

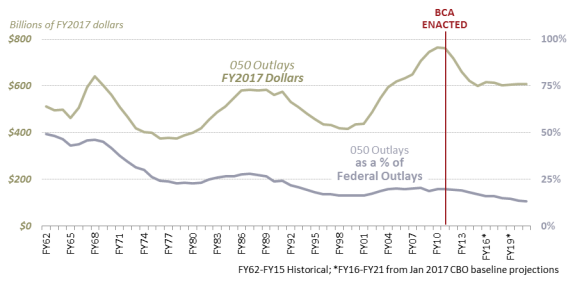

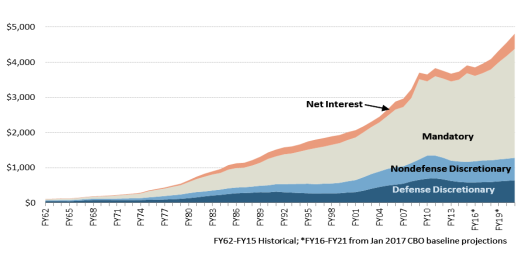

CRS has estimated that the BCA as amended would reduce FY2012-FY2021 annual budget deficits by $1.9 trillion (inclusive of net interest costs).4 Despite the deficit reduction effects of the BCA, the January 2017 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) baseline projects that real budget deficits would increase from 2.9% of GDP in FY2017 to 5.0% of GDP in FY2027.5 This projected growth is attributable to projected increases in real mandatory spending and net interest payments exceeding the anticipated BCA reductions in discretionary spending and rise in revenues in those years. Mandatory spending increases are generally a reflection of increases in the cost of health and income security programs due to factors such as changing demographics, rising per capital health care costs, and changes to benefits.6 In FY2011, mandatory spending and net interest consumed 61.0% of the federal budget and is forecast to grow to 73.4% of federal budget in FY2021 (see Figure 1).7

|

Figure 1. Outlays by Budget Enforcement Category FY1962-FY2021 in billions of nominal dollars |

|

|

Source: OMB Historical Table 8.1 and CBO, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2017 to 2027, January 2017. Notes: CBO projections are based on current law, and assume that the limits on discretionary budget authority established by the BCA as amended will proceed as scheduled. Outlays include programs designated as Overseas Contingency Operations and other adjustments to the discretionary budget authority limits established by the BCA as amended. For more information factors contributing to the growth of mandatory spending, CRS Report R44763, Present Trends and the Evolution of Mandatory Spending, by [author name scrubbed]. |

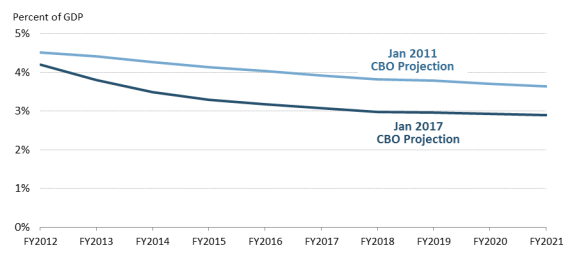

Federal outlays devoted to defense programs have fallen as a share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in every year since enactment of the BCA. In FY2011, defense outlays equaled 4.5% of GDP. By FY2021–the last year of the BCA limits on defense discretionary budget authority–CBO projects that defense outlays would equal 2.9% of GDP (see Figure 2).8

Defense Policymakers and Senior Officials Seek Relief from BCA Limits

The discretionary spending limits established by the BCA have been a point of deliberation since they were instituted in 2011 with many defense advocates arguing that associated reductions to defense investments "present a grave and growing danger to our national security."9 At the same time, concerns over recurring deficits and growing federal debt remain, and some pundits argue the BCA limits are necessary.

The federal government already spends far more than it receives and legislators have a responsibility to spend only as much as they need to. The spending caps put in place by the BCA, and the punitive nature of the sequestering that follows if they are exceeded, are well-designed measures that encourage responsible spending. The incoming administration should not let rhetoric get in the way of duty.10

Members of Congress and the executive branch have often expressed dissatisfaction with the spending limits and reductions required by the BCA/P.L. 112-25, and modifications to both the defense and nondefense limits have been enacted for the fiscal years FY2013-FY2017. Following the November 2016 presidential election, Members of Congress, senior military officials, and President Trump have either proposed increases to the defense spending limit or called for repeal of the BCA.

- In a January 16, 2017, white paper on the FY2018-FY2022 defense budget, Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, Senator John McCain, stated,

By all measures the BCA has failed. A law intended to reduce federal spending has cut defense and other discretionary budgets for five years without decreasing the federal debt.... This law (BCA) must be repealed outright so we can budget for the true costs of our national defense.11

- On February 9, 2017, Vice Chief of Staff of the Army, General Daniel B. Allyn, took an unusual step for a senior uniformed military officer and provided an overall assessment of the bill's impact, telling members of the House Armed Services Committee (HASC) that "[t]he most important actions you can take—steps that will have both a positive and lasting impact—will be to immediately repeal the 2011 Budget Control Act and ensure sufficient funding to train, man and equip the FY17 NDAA authorized force."12

- Congressman Mike Turner, Chairman of the HASC Subcommittee on Tactical Air and Land Forces, introduced the Repeal Sequestration for Defense Act (H.R. 1441) on March 8, 2017. Before filing the bill, Chairman Turner had gathered more than 100 congressional lawmakers' signatures on a letter to Speaker Paul Ryan asking for a vote on the floor of the House to repeal the budget reductions.13

- On March 16, 2017, the Trump Administration released two defense budget proposals—a topline proposal for national defense discretionary spending for fiscal year (FY) 2018 as part of the Administration's Budget Blueprint for Federal spending, and a detailed request for additional funding for Department of Defense (DOD) military activities for FY2017.14

- The Blueprint represents a $603 billion request for national defense (budget function 050) discretionary budget authority for FY2018 base budget requirements and $65 billion for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO). In conjunction with the proposal for FY2018, the Trump Administration also requested $30 billion for DOD military activities (budget subfunction 051) in addition to the amounts requested by the Obama Administration. Of this amount, $24.9 billion is slated for base budget activities and $5.1 billion is associated with OCO.

- Both base budget proposals exceed the current statutory limits on defense discretionary spending established by the BCA. The Administration's proposals propel the issue of amending or repealing the BCA near the forefront of congressional deliberations on the federal budget.

- On March 22, 2017, Secretary of Defense Mattis testified before the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee and in response to a question on the impact of BCA, told the panel,

I can find nothing in the Budget Control Act that—that helps our national security.... I believe it also sidelines the Congress. I think it puts you in a spectator role when we need you in an oversight role in the department because it's your knowledge of what we're doing and understanding the strategy that allows you to commit American dollars to the defense of this country.

As it is now, we're all watching as this—I would call it near-senseless approach to budgeting—goes on its automatic pilot and we all stand there mute saying there's no way you can dignify it.... It hurts us in terms of readiness and in terms of long-term capability to defend the country.15

- On March 23, 2017, Congressman Adam Smith, Ranking Member on the House Armed Services Committee, introduced the Relief from Sequester Act (H.R. 1745).16 The bill contains several findings, the first of which states, "Sequestration was designed as a forcing mechanism for an agreement on a comprehensive, deficit reduction plan. It has failed to produce the intended results."

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the BCA limits on the defense budget?

The BCA affects annual defense spending in two primary ways. First, the BCA established statutory limits on defense and nondefense discretionary spending through FY2021 that are enforced by sequestration.17 The limits on defense apply to discretionary budget authority provided for national defense (budget function 050).18 These limits effectively do not apply to appropriations designated by both Congress and the President as funding either (1) for an "emergency," or (2) for "Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO)."19

Second, in absence of the enactment of a Joint Committee on Deficit Reduction bill to reduce the deficit by at least $1.2 trillion, the BCA required downward adjustments (or reductions) to the statutory limit on both defense and nondefense spending each year through FY2021. This automatic process to reduce spending began in FY2013 and is often referred to as a sequester. These reductions are to be calculated annually by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and are included in the OMB Sequestration Preview Report to the President and Congress, which is to be issued with the President's annual budget submission.20

Congress has amended the BCA three times since enactment.21 Collectively, these amendments resulted in revisions the limits in years FY2013 through FY2017. Table 1 depicts the BCA limits, as amended and adjusted, on national defense (function 050) budget authority.

Table 1. BCA Limits on National Defense (050) Discretionary Budget Authority

billions of then-year dollars

|

National Defense (050) |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

Budget Control Act of 2011 |

555 |

546 |

556 |

566 |

577 |

590 |

603 |

616 |

630 |

644 |

|

Budget Control Act of 2011 after revision (sequestration) |

555 |

492 |

502 |

512 |

523 |

536 |

549 |

562 |

576 |

590 |

|

American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 |

555 |

518* |

498* |

512 |

523 |

536 |

549 |

562 |

576 |

590 |

|

Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 |

555 |

518 |

520* |

521* |

523 |

536 |

549 |

562 |

576 |

590 |

|

Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 |

555 |

518 |

520 |

521 |

548* |

551* |

549 |

562 |

576 |

590 |

|

*[Bold-italics] indicates a statutory change was made to the original BCA limits. |

||||||||||

Source: CRS analysis of P.L. 112-240, P.L. 113-67, and P.L. 114-74; CBO Final Sequestration Report for Fiscal Year 2012.

Notes: Amounts shown reflect the projected automatic reduction required when a bill reported by the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction to reduce the deficit by at least $1.2 trillion was not enacted by January 15, 2012.

The national defense budget (function 050) is comprised of DOD military (subfunction 051), defense-related programs in the Department of Energy for nuclear weapons (subfunction 053), and defense-related activities of the Department of Justice (subfunction 054). DOD military activities (subfunction 051) have historically constituted approximately 95% of the national defense budget request. Although the BCA does not establish limits on the subfunctions (051, 053 and 054), the BCA limits on function 050 have been applied proportionally to the subfunctions in practice. Table 2 provides the estimated effects of the BCA on DOD budget authority.

Table 2. Estimated Effect of the BCA on DOD Military (051) Budget Authority

billions of then-year dollars

|

DOD Military (051) |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

Budget Control Act of 2011 |

531 |

521 |

530 |

540 |

550 |

563 |

575 |

588 |

601 |

614 |

|

Budget Control Act of 2011 after revision (sequestration) |

531 |

473 |

480 |

490 |

500 |

513 |

525 |

537 |

551 |

564 |

|

American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 |

531 |

495* |

475* |

490 |

500 |

513 |

525 |

537 |

551 |

564 |

|

Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 |

531 |

495 |

496* |

496* |

500 |

513 |

525 |

537 |

551 |

564 |

|

Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 |

531 |

495 |

496 |

496 |

522* |

526* |

525 |

537 |

551 |

564 |

|

*[Bold-italics] indicates a statutory change was made to the original BCA limits. |

||||||||||

Source: CRS estimate based on P.L. 112-240, P.L. 113-67, and P.L. 114-74; CBO Final Sequestration Report for Fiscal Year 201; OMB Historical Table 5.1, Budget Authority by Function and Subfunction: 1976-2021.

Notes: The budget for DOD military activities (051) is a subset of the national defense budget (050), shown in Table 1 and has historically constituted approximately 95% of the national defense budget request.

What is a sequester?22

A sequester provides for the enforcement of budgetary limits established in law through the automatic cancellation of previously enacted spending, making largely across-the-board reductions to nonexempt programs, activities, and accounts. A sequester is implemented through a sequestration order issued by the President as required by law. The purpose of sequestration is to deter enactment of legislation violating the spending limits or, in the event that such legislation is enacted violating these spending limits, to automatically reduce spending to the limits specified in law. Each statutory limit—defense and nondefense—is separately enforced so that the breach of the limit for one category is enforced by a sequester of resources only within that category.

Does the BCA limit Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) funding?

The BCA stipulates that certain discretionary funding, such as appropriations designated as emergency requirements or Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), allow for an upward adjustment of the discretionary limits. In essence, OCO funding is therefore described as being "exempt" from the discretionary spending limits.

The BCA does not define what constitutes OCO funding. Instead, it includes a requirement that Congress designate spending as being OCO on an account-by-account basis, and that the President subsequently designate the spending as OCO. Further, the BCA does not limit the level or amount of spending that may be designated as OCO.

The designation of certain war-related activities and expenses as OCO requirements has shifted over time, reflecting differing viewpoints about the extent, nature, and duration of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Recently, Congress and the President have designated as "OCO" funds for a variety of activities that had previously been contained in the DOD base budget.23 By designating ongoing activities not directly related to contingency operations as "OCO," Congress and the President can effectively continue to increase topline defense, foreign affairs, and other related discretionary spending, without triggering sequestration.24

How has defense spending changed since enactment of the BCA?

The BCA discretionary limits were projected to reduce the level of national defense (function 050) spending for the decade (FY2012-FY2021) by about 14% or $860 billion compared to continuing the FY2011 enacted level in real terms (steady-state spending with an adjustment for inflation).25 The absence of legislation to reduce the federal budget deficit by at least $1.2 trillion triggered the sequestration process in 2013. In accordance with the BCA, President Obama ordered the sequestration of budgetary resources across nonexempt federal government accounts on March 1, 2013—five months into the fiscal year. DOD was required to apply a $37 billion sequester to $528 billion in available (subfunction 051) budgetary resources—a reduction of 7%.

Figure 3 compares CBO projections of FY2012-FY2021 discretionary defense outlays in January 2011, months before BCA enactment, with actual data and their January 2017 forecast. The figure illustrates a reduction in actual and projected defense spending over that time period, ranging from 0.41% of GDP in FY2012 to 0.95% of GDP in FY2018.

Figure 4 shows inflation-adjusted defense outlays from FY1962 to FY2021 and reflects 6.7% reduction in projected defense outlays during the period of the BCA (FY2012-FY2021). CBO projects the defense outlays to decline from 18% of the federal budget in FY2011 to 13% by FY2021 as mandatory spending and net interest are expected to reach 73.4% of the federal budget by that time (see Figure 1).26

BCA Effects on the DOD Military (051) Budget

The budget plan submitted with the President's FY2012 budget may provide a reference point for the BCA's effect on DOD military (051) spending, as it was the last budget submitted to Congress prior to enactment of the BCA. The Future Years Defense Program (FYDP), submitted to Congress in conjunction with the budget request, contains information on programmed dollars, manpower and force structure over a 5-year period.27

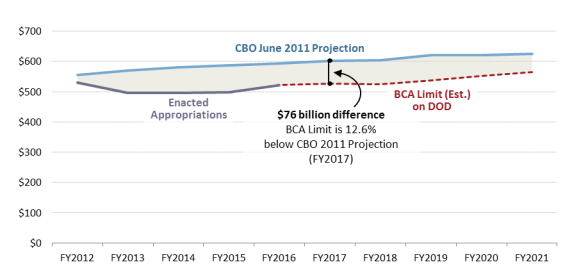

CBO issued its long-term projection for DOD spending based on the 2012 FYDP in June 2011, two months prior to enactment of the BCA.28 Using the CBO projections based on the FY2012 FYDP as a baseline, Figure 5 provides a comparison of the FY2012 budget request to actual appropriations provided in accordance with the BCA limits. The FY2012 budget request included $553 billion for DOD military (051). Based on that, CBO projected a budget of $602 billion for DOD in FY2017. The FY2017 BCA limit of $526 billion is $76.0 billion (12.6%) below the June 2011 CBO projection for FY2017. Over the period FY2012-FY2021, the projected BCA limits on DOD are $714.0 billion (12.0%) below the June 2011 CBO projections for the period.

|

Figure 5. Effects of the BCA on DOD Military (051) Budget Authority billions of then-year dollars |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis the BCA (P.L. 112-25) as amended, defense appropriations acts for fiscal year 2013-2016 and CBO's Long Term Implications of FY2012 Future Years Defense Program, Table A-1, June 2011. |

For information on the broader effects of the BCA, see CRS Report R42506, The Budget Control Act of 2011 as Amended: Budgetary Effects, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed].

Would appropriations authorized by the FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act conform to the BCA limits?

The National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2017 (S. 2943/P.L. 114-328) was enacted December 23, 2016 and authorized $543.4 billion for programs under the jurisdiction of the House and Senate Armed Services Committees. Authorizations of discretionary appropriations–such as the NDAA–do not provide budget authority, and therefore, cannot trigger a sequester for violation of the discretionary spending limits. In authorizing defense appropriations for FY2017, P.L. 114-238 corresponds to the broader national defense (function 050) BCA limit of $551 billion.29

The House-passed version of the FY2017 NDAA (H.R. 4909) would have dedicated $23.1 billion of OCO-designated funding to DOD base budget purposes—$18.0 billion more than the Obama Administration proposed. Such funding would not have been subject to the BCA limits. However, the Administration and the congressional minority leadership objected to providing defense funding for base budget requirements in excess of the defense spending limit unless it was accompanied by a comparable increase in funding for nondefense, base budget programs.30 Negotiations between the House and Senate NDAA conferees resulted in the allocation of $8.3 billion in OCO-designated funding for base requirements—$5.2 billion stemming from the Administration's request and $3.2 billion added during the conference negotiations (see Table 3).31

Table 3. FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 4909, S. 2943)

billions of dollars of discretionary budget authority

in the jurisdiction of the Armed Services Committees

|

Title |

Budget Request |

House-passed H.R. 4909 |

Senate-passed |

Enacted |

||||||||

|

Base Budget |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

OCO for OCO purposes |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

OCO for base budget purposes a |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Subtotal: DOD OCO Budget |

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

Source: H.Rept. 114-537, H.R. 4909, S.Rept. 114-255, and S. 2943.

Notes: Totals may not reconcile due to rounding. Includes only those accounts under the jurisdictions of the House and Senate Armed Services Committees.

a. In its report on S. 2943, the Senate Armed Services Committee did not identify OCO funding that was requested or authorized for base budget purposes.

Would proposed FY2017 defense appropriations conform to the BCA limits?

Congressional action on the FY2017 defense appropriations bill has not been completed. DOD has operated under continuing resolutions thus far in FY2017 (P.L. 114-223 /P.L. 114-254), which expire April 28, 2017.32 The rate of operations provided under the continuing resolution is based on the FY2016 appropriated level. CBO has projected the level of spending provided in these continuing resolutions to be below the BCA spending limit for FY2017.33

Much like the House-passed NDAA, the first House-passed Defense Appropriations Act for 2017 (H.R. 5293) would have provided for additional OCO funding to be used for base budget requirements ($23.1 billion). The Senate committee-reported bill (S. 3000) bill did not.34

On March 2, 2017, H.R. 1301 was introduced as the "final version" of the FY2017 Defense Appropriations bill and reflects an agreement between the House and Senate on defense appropriations for FY2017 (see Table 4).35 The bill appears to be consistent with the FY2017 NDAA (P.L. 114-328) and, if enacted in its current form, would likely comply with the BCA limits.

Table 4. FY2017 Defense Appropriations Act (H.R. 5293, S. 3000, and H.R. 1301)

billions of dollars of discretionary budget authority in the jurisdiction of the Subcommittees on Defense

|

Title |

Budget Requesta |

|||

|

DOD Base Budget (051) |

$511.2 |

$510.6 |

$509.5 |

$509.6 |

|

OCO for OCO purposes |

$53.7 |

$43.0 |

$58.9 |

$61.8 |

|

OCO for base budget purposesb |

$5.1 |

$15.7 |

— |

— |

|

Subtotal: DOD OCO Budget |

$64.6 |

$58.6 |

$58.6 |

$61.8 |

|

Totalc |

$569.9 |

$569.3 |

$568.1 |

$571.5 |

Source: H.Rept. 114-577, H.R. 5293, S.Rept. 114-263, S. 3000, H.R. 1301, and the Explanatory Statement to Accompany H.R. 1301, at https://rules.house.gov/bill/115/hr-130.

Notes: Totals may not reconcile due to rounding. Includes only those accounts under the jurisdiction of the Defense Appropriations Subcommittees.

a. Includes the November 2016 OCO Budget Amendment.

b. Neither the report to accompany S. 3000, nor the Explanatory Statement to Accompany H.R. 1301 identifies OCO funding that was requested or authorized for base budget purposes.

Trump Administration Defense Budget Proposals

On March 16, 2017, the Trump Administration released two defense budget proposals—a topline proposal for national defense discretionary spending for FY2018 as part of the Administration's Budget Blueprint for Federal spending, and a detailed request for additional funding for DOD military activities for FY2017.36

The Budget Blueprint represents a $603 billion request for national defense (function 050) discretionary budget authority for FY2018 base budget requirements and $65 billion for OCO. In conjunction with the proposal for FY2018, the Trump Administration also requested $30 billion for FY2017 DOD military activities (budget subfunction 051) in addition to the amounts requested by the Obama Administration. Of this amount, $24.9 billion is slated for base budget activities and $5.1 billion is associated with OCO. The Trump Administration's proposals exceed the current BCA limits for both FY2017 and FY2018. For more information see CRS Report R44806, The Trump Administration's March 2017 Defense Budget Proposals: Frequently Asked Questions, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed].