The Defense Budget and the Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions

Changes from April 21, 2017 to July 13, 2018

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

The Budget Control Act and the Defense BudgetDefense Budget and the Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions

Contents

- Background

- Frequently Asked Questions

- What

are the BCA limits on the defense budget? What is a sequesteris the debate over defense spending caps?- How does the BCA affect defense spending?

What are the BCA limits on defense discretionary spending?- Does the BCA limit Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) funding?

- How has defense spending changed since enactment of the BCA?

Would appropriations authorized by the FY2017What are the BCA limits on the Department of Defense (DOD)?- How have the defense spending caps changed over time?

- What is a sequester?

- Can the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) trigger a sequester?

- How has defense discretionary spending changed since enactment of the BCA?

- What are the Administration's plans for defense spending?

- Acknowledgements

National Defense Authorization Act conform to the BCA limits?- Would proposed FY2017 defense appropriations conform to the BCA limits?

Figures

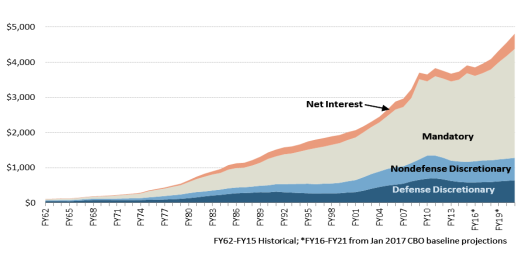

- Figure 1. Outlays by Budget Enforcement Category , FY1962-FY2023

- Figure 2. Changes to BCA Limits on National Defense (050) Discretionary Budget Authority, FY2012-FY2021

- Figure 3. National Defense (050) Discretionary Outlays, FY1962-FY2023

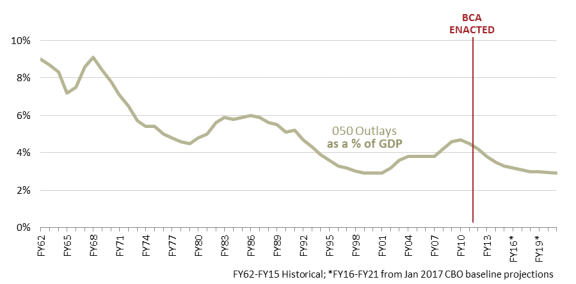

- Figure 2. National Defense (050) Outlays as Percentage of GDP

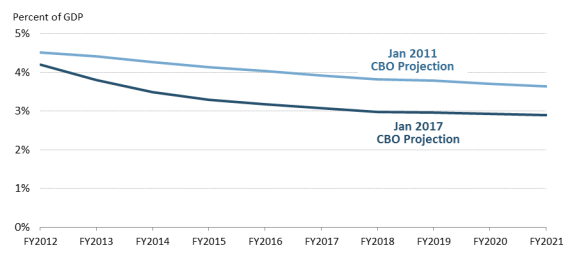

- Figure 3. Defense Outlays: CBO Projections in January 2011 and January 2017

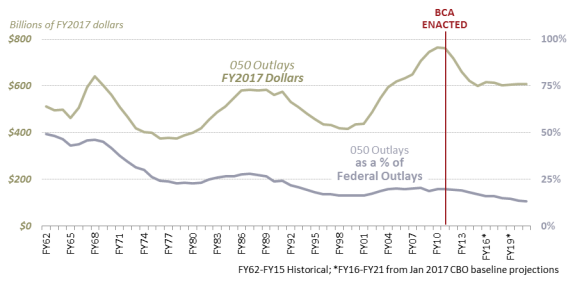

- Figure 4. National Defense (050) Outlays, FY1962-FY2021

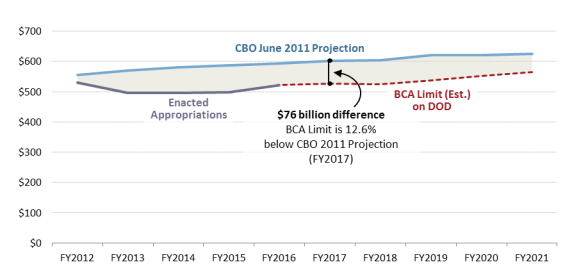

- Figure 5. Effects of the BCA on DOD Military (051) Budget Authority

Tables

- Table 1. BCA Limits on National Defense (050) Discretionary Base Budget Authority

Summary

Enacted on August 2, 2011, the Budget Control Act of 2011 as amended (P.L. 112-25, P.L. 112-240, P.L. 113-67, P.L. 114-74, and P.L. 115-123) sets limits on defense and nondefense spending. As part of an agreement to increase the statutory limit on public debt, the BCA aimed to reduce annual federal budget deficits by a total of at least $2.1 trillion from FY2012 through FY2021, with approximately half of the savings to come from defense.

The spending limits (or caps) apply separately to defense and nondefense discretionary budget authority. Budget authority is authority provided by law to a federal agency to obligate money for goods and services. The caps are enforced by a mechanism called sequestration. Sequestration automatically cancels previously enacted appropriations (a form of budget authority) by an amount necessary to reach prespecified levels. The defense spending limits apply to national defense (budget function 050) but not to funding designated for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) or emergencies.

Some defense policymakers and officials argue the spending restrictions impede the Department of Defense's (DOD's) ability to adequately prepare military personnel and equipment for operations and other national security requirements. Others argue the limits are necessary to curb rising deficits and debt.

After lawmakers did not reach a deficit-reduction deal and triggered steeper reductions to the initial BCA caps, Congress repeatedly amended the legislation to raise the spending limits. Most recently, President Donald Trump on February 9, 2018, signed into law the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123). The bill amended the BCA to increase discretionary defense spending caps by the largest amounts to date—by $80 billion to $629 billion in FY2018 and by $85 billion to $647 billion in FY2019. It did not change the spending limits for FY2020 and FY2021.

The annual federal budget deficit decreased from $1.1 trillion (6.8% of Gross Domestic Product) in FY2012 to $665 billion (3.5% of GDP) in FY2017, but is projected to increase to $1.1 trillion (4.9% of GDP) in FY2021. Meanwhile, federal debt held by the public has increased from $11.3 trillion (70.4% of GDP) in FY2012 to $14.7 trillion (76.5% of GDP) in FY2017, and is projected to further increase to $19 trillion (83.1% of GDP) in FY2021.

Background

National defense is one of 20 major functions used by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to organize budget data―and the largest in terms of discretionary spending. The national defense budget function (identified by the numerical notation 050) comprises three subfunctions: Department of Defense (DOD)-Military (051); atomic energy defense activities primarily of the Department of Energy (DOE) (053); and other defense-related activities (054) such as Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) counterintelligence activities.1 Discretionary spending is, for the most part, provided by annual appropriations bills and the focus of Congress's efforts to fund the federal government. By contrast, mandatory (or direct) spending, which includes entitlement programs such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, is generally governed by existing statutory criteria.2 Since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, outlays—money spent by a federal agency from funds provided by Congress—for discretionary defense programs in nominal dollars (not adjusted for inflation) has almost doubled from $306 billion in FY2001 to $590 billion in FY2017. Defense discretionary outlays are projected to reach $655 billion in FY2021. Yet as a percentage of total federal outlays, discretionary defense outlays declined over this period from 16.4% in FY2001 to 14.8% in FY2017. They are projected to further decrease to 13.2% in FY2021, as mandatory programs and net interest consume a larger share of the total (see Figure 1).3Between FY2009 and FY2012, annual federal budget deficits topped $1 trillion and averaged 8.5% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the highest level since World War II. The deficits are attributable in part to reduced tax revenues from the 2007-2009 recession and increased spending from the economic stimulus package known as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5).4 As part of an agreement to increase the statutory limit on public debt, the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25) aimed to reduce annual federal budget deficits by a total of at least $2.1 trillion from FY2012 through FY2021, with approximately half of the savings to come from defense.

Congress has previously used budget enforcement mechanisms—such as a statutory limit on annual appropriations for discretionary activities—to mandate a specific budgetary policy or to obtain a fiscal objective. The BCA amended the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 (P.L. 99-177) by reinstating spending limits on discretionary budget authority beginning in FY2012.5 Congress provides budget authority by law to federal agencies to obligate money for goods and services. Congress does not directly control outlays, which occur when obligations are liquidated, primarily through issuing checks, transferring funds, or disbursing cash.6 For spending limits in FY2012 and FY2013, the BCA originally specified separate "security" and "nonsecurity" categories. The security category was broad in scope and included budget accounts of the Department of Defense (DOD), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the National Nuclear Security Administration, the intelligence community management account, and international affairs (budget function 150).7 After the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction did not reach a deficit-reduction deal and triggered backup budgetary enforcement measures of steeper reductions to the initial BCA caps beginning in FY2013, the "security" category was revised to the narrower "defense" category, which included only discretionary programs in the national defense budget function (050).

Figure 1. Outlays by Budget Enforcement Category, FY1962-FY2023(in trillions of dollars)

Budget Authority - Table 2. Estimated Effect of the BCA on DOD Military (051) Budget Authority

- Table 3. FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 4909, S. 2943)

- Table 4. FY2017 Defense Appropriations Act (H.R. 5293, S. 3000, and H.R. 1301)

Summary

Following lengthy congressional deliberations on deficit reduction, the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA/P.L. 112-25) was enacted on August 2, 2011. The BCA contained several measures intended to reduce the budget deficit by $2.1 trillion over the period FY2012-FY2021. The BCA established limits on the level of discretionary spending in order to achieve projected savings of approximately $1.0 trillion over the period. In addition, the BCA required approximately $1.1 trillion in savings to be generated from a plan developed by the congressionally established, bipartisan, Joint Committee on Deficit Reduction.

The BCA limits apply separately to defense and nondefense discretionary budget authority and are enforced by a mechanism called sequestration. Sequestration automatically cancels previously enacted spending to reduce discretionary spending to the limits specified in the BCA. The defense limits apply to the national defense budget (function 050), but do not restrict amounts provided for "emergencies" or "Overseas Contingency Operations."

Calls to remove or raise the limits on defense spending have greatly intensified following the November 2016 presidential election. Senior members of the House and Senate have called for action to eliminate the threat of sequestration to defense and related legislation (H.R. 1441 and H.R. 1745) has been recently introduced in the House. On March 16, 2017, President Trump submitted budget proposals for defense that exceed the BCA limits for FY2017 and FY018, requesting Congress increase or remove the caps.

This report addresses several frequently asked questions related to the BCA and the defense budget.

For more information see CRS Report R42506, The Budget Control Act of 2011 as Amended: Budgetary Effects, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]; CRS Insight IN10389, Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015: Adjustments to the Budget Control Act of 2011, by [author name scrubbed]; CRS Report R42972, Sequestration as a Budget Enforcement Process: Frequently Asked Questions, by [author name scrubbed]; and CRS Report R41901, Statutory Budget Controls in Effect Between 1985 and 2002, by [author name scrubbed].

Background

In the past, Congress has used budget enforcement mechanisms—such as a statutory limit on annual appropriations for discretionary activities—to mandate a specific budgetary policy or to obtain a fiscal objective.1 Such discretionary spending limits were first in effect between FY1991 and FY2002, and were reestablished in the Budget Control Act of 2011(BCA/P.L. 112-25).

The BCA contains several measures intended to reduce the budget deficit by $2.1 trillion over the period FY2012-FY2021. A key component of the BCA is the establishment limits on the level of discretionary spending in order to achieve projected savings of approximately $1.0 trillion over that period. These limits are similar to budget enforcement mechanisms used previously by Congress. In addition, the BCA required approximately $1.1 trillion in savings to be generated from a plan developed by the congressionally established, bipartisan, Joint Committee on Deficit Reduction.

The BCA limits apply separately to defense and nondefense discretionary budget authority and are enforced by a mechanism called sequestration.2 Sequestration provides for the automatic cancellation of previously enacted spending to reduce discretionary spending to the limits specified in the BCA. The defense limits apply to the national defense budget (function 050), but do not restrict amounts provided for "emergencies" or "Overseas Contingency Operations."3 Absent enactment of a Joint Committee on Deficit Reduction bill to reduce the deficit by at least $1.2 trillion, the BCA required downward adjustments (or reductions) to the statutory limit on both defense and nondefense spending each year through FY2021. This automatic reduction to the original BCA limits is also referred to as sequestration.

CRS has estimated that the BCA as amended would reduce FY2012-FY2021 annual budget deficits by $1.9 trillion (inclusive of net interest costs).4 Despite the deficit reduction effects of the BCA, the January 2017 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) baseline projects that real budget deficits would increase from 2.9% of GDP in FY2017 to 5.0% of GDP in FY2027.5 This projected growth is attributable to projected increases in real mandatory spending and net interest payments exceeding the anticipated BCA reductions in discretionary spending and rise in revenues in those years. Mandatory spending increases are generally a reflection of increases in the cost of health and income security programs due to factors such as changing demographics, rising per capital health care costs, and changes to benefits.6 In FY2011, mandatory spending and net interest consumed 61.0% of the federal budget and is forecast to grow to 73.4% of federal budget in FY2021 (see Figure 1).7

FY1962-FY2021 in billions of nominal dollars |

|

|

Source: OMB Historical Table 8.1 and CBO, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2017 to 2027, January 2017. Notes: CBO projections are based on current law, and assume that the limits on discretionary budget authority established by the BCA as amended will proceed as scheduled. Outlays include programs designated as Overseas Contingency Operations and other adjustments to the discretionary budget authority limits established by the BCA as amended. For more information factors contributing to the growth of mandatory spending, CRS Report R44763, Present Trends and the Evolution of Mandatory Spending, by [author name scrubbed]. |

Federal outlays devoted to defense programs have fallen as a share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in every year since enactment of the BCA. In FY2011, defense outlays equaled 4.5% of GDP. By FY2021–the last year of the BCA limits on defense discretionary budget authority–CBO projects that defense outlays would equal 2.9% of GDP (see Figure 2).8

Defense Policymakers and Senior Officials Seek Relief from BCA Limits

The discretionary spending limits established by the BCA have been a point of deliberation since they were instituted in 2011 with many defense advocates arguing that associated Actual figures from FY1962 through FY2017 from OMB; projections from FY2018 through FY2023 from CBO. Outlays include funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO).

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the debate over defense spending caps?

The discretionary spending limits established by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25) have been a point of contention since enactment.

Critics of the legislation argue reductions to defense investments "present a grave and growing danger to our national security."9 At the same time, concerns over recurring deficits and growing federal debt remain, and some pundits argue the BCA limits are necessary.

The federal government already spends far more than it receives and legislators have a responsibility to spend only as much as they need to. The spending caps put in place by the BCA, and the punitive nature of the sequestering that follows if they are exceeded, are well-designed measures that encourage responsible spending. The incoming administration should not let rhetoric get in the way of duty.10

Members of Congress and the executive branch have often expressed dissatisfaction with the spending limits and reductions required by the BCA/P.L. 112-25, and modifications to both the defense and nondefense limits have been enacted for the fiscal years FY2013-FY2017. Following the November 2016 presidential election, Members of Congress, senior military officials, and President Trump have either proposed increases to the defense spending limit or called for repeal of the BCA.

- In a January 16, 2017, white paper on the FY2018-FY2022 defense budget, Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, Senator John McCain, stated,

By all measures the BCA has failed. A law intended to reduce federal spending has cut defense and other discretionary budgets for five years without decreasing the federal debt.... This law (BCA) must be repealed outright so we can budget for the true costs of our national defense.11

- On February 9, 2017, Vice Chief of Staff of the Army, General Daniel B. Allyn, took an unusual step for a senior uniformed military officer and provided an overall assessment of the bill's impact, telling members of the House Armed Services Committee (HASC) that "[t]he most important actions you can take—steps that will have both a positive and lasting impact—will be to immediately repeal the 2011 Budget Control Act and ensure sufficient funding to train, man and equip the FY17 NDAA authorized force."12

- Congressman Mike Turner, Chairman of the HASC Subcommittee on Tactical Air and Land Forces, introduced the Repeal Sequestration for Defense Act (H.R. 1441) on March 8, 2017. Before filing the bill, Chairman Turner had gathered more than 100 congressional lawmakers' signatures on a letter to Speaker Paul Ryan asking for a vote on the floor of the House to repeal the budget reductions.13

- On March 16, 2017, the Trump Administration released two defense budget proposals—a topline proposal for national defense discretionary spending for fiscal year (FY) 2018 as part of the Administration's Budget Blueprint for Federal spending, and a detailed request for additional funding for Department of Defense (DOD) military activities for FY2017.14

- The Blueprint represents a $603 billion request for national defense (budget function 050) discretionary budget authority for FY2018 base budget requirements and $65 billion for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO). In conjunction with the proposal for FY2018, the Trump Administration also requested $30 billion for DOD military activities (budget subfunction 051) in addition to the amounts requested by the Obama Administration. Of this amount, $24.9 billion is slated for base budget activities and $5.1 billion is associated with OCO.

- Both base budget proposals exceed the current statutory limits on defense discretionary spending established by the BCA. The Administration's proposals propel the issue of amending or repealing the BCA near the forefront of congressional deliberations on the federal budget.

- On March 22, 2017, Secretary of Defense Mattis testified before the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee and in response to a question on the impact of BCA, told the panel,

I can find nothing in the Budget Control Act that—that helps our national security.... I believe it also sidelines the Congress. I think it puts you in a spectator role when we need you in an oversight role in the department because it's your knowledge of what we're doing and understanding the strategy that allows you to commit American dollars to the defense of this country.

As it is now, we're all watching as this—I would call it near-senseless approach to budgeting—goes on its automatic pilot and we all stand there mute saying there's no way you can dignify it.... It hurts us in terms of readiness and in terms of long-term capability to defend the country.15

- On March 23, 2017, Congressman Adam Smith, Ranking Member on the House Armed Services Committee, introduced the Relief from Sequester Act (H.R. 1745).16 The bill contains several findings, the first of which states, "Sequestration was designed as a forcing mechanism for an agreement on a comprehensive, deficit reduction plan. It has failed to produce the intended results."

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the BCA limits on the defense budget?

The BCA affects annual defense spending in two primary ways. First, the BCA established statutory limits on defense and nondefense discretionary spending through FY2021 that are enforced by sequestration.17 The limits on defense apply to discretionary budget authority provided for national defense (budget function 050).18 These limits effectively do not apply to appropriations designated by both Congress and the President as funding either (1) for an "emergency," or (2) for "Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO)."19

Second, in absence of the enactment of a Joint Committee on Deficit Reduction bill to reduce the deficit by at least $1.2 trillion, the BCA required downward adjustments (or reductions) to the statutory limit on both defense and nondefense spending each year through FY2021. This automatic process to reduce spending began in FY2013 and is often referred to as a sequester. These reductions are to be calculated annually by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and are included in the OMB Sequestration Preview Report to the President and Congress, which is to be issued with the President's annual budget submission.20

Congress has amended the BCA three times since enactment.21 Collectively, these amendments resulted in revisions the limits in years FY2013 through FY2017. Table 1 depicts the BCA limits, as amended and adjusted, on national defense (function 050) budget authority.

Table 1. BCA Limits on National Defense (050) Discretionary Budget Authority

Proponents of BCA argue its limits are necessary in light of recurring deficits and growing federal debt: "The spending caps put in place by the BCA, and the punitive nature of the sequestering that follows if they are exceeded, are well-designed measures that encourage responsible spending."11 Representative Mark Meadows, chair of the House Freedom Caucus, which opposed the latest budget deal to raise the spending caps, said, "I want to fund our military, but at what cost? Should we bankrupt our country in the process?"12 Lawrence Korb, an Assistant Secretary of Defense during the Reagan Administration, said the BCA has "affected defense capability somewhat," but noted Congress has blunted the law's impact by increasing the caps and by exempting from the restrictions funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), allowing the Department of Defense (DOD) to use such funds for base-budget activities.13billions of then-year dollars8 They also note the spending restrictions disproportionately affect defense programs, which in FY2017 accounted for 16% of budgetary resources (excluding net interest payments) and 49% of BCA spending reductions.9 Senator John McCain and Representative William "Mac" Thornberry, the chairs of the Senate and House Armed Services Committees, respectively, have said the law has "failed."10 Defense Secretary James Mattis has said: "Let me be clear: As hard as the last 16 years of war have been on our military, no enemy in the field has done as much to harm the readiness of U.S. military than the combined impact of the BCA's defense spending caps, worsened by operating for ten of the last 11 years under continuing resolutions of varied and unpredictable duration."

|

National Defense (050) |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

Budget Control Act of 2011 |

555 |

546 |

556 |

566 |

577 |

590 |

603 |

616 |

630 |

644 |

|

Budget Control Act of 2011 after revision (sequestration) |

555 |

492 |

502 |

512 |

523 |

536 |

549 |

562 |

576 |

590 |

|

American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 |

555 |

518* |

498* |

512 |

523 |

536 |

549 |

562 |

576 |

590 |

|

Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 |

555 |

518 |

520* |

521* |

523 |

536 |

549 |

562 |

576 |

590 |

|

Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 |

555 |

518 |

520 |

521 |

548* |

551* |

549 |

562 |

576 |

590 |

|

*[Bold-italics] indicates a statutory change was made to the original BCA limits. |

||||||||||

Source: CRS analysis of P.L. 112-240, P.L. 113-67, and P.L. 114-74; CBO Final Sequestration Report for Fiscal Year 2012.

Notes: Amounts shown reflect the projected automatic reduction required when a bill reported by the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction to reduce the deficit by at least $1.2 trillion was not enacted by January 15, 2012.

The national defense budget (function 050) is comprised of DOD military (subfunction 051), defense-related programs in the Department of Energy for nuclear weapons (subfunction 053), and defense-related activities of the Department of Justice (subfunction 054). DOD military activities (subfunction 051) have historically constituted approximately 95% of the national defense budget request. Although the BCA does not establish limits on the subfunctions (051, 053 and 054), the BCA limits on function 050 have been applied proportionally to the subfunctions in practice. Table 2 provides the estimated effects of the BCA on DOD budget authority.

Table 2. Estimated Effect of the BCA on DOD Military (051) Budget Authority

billions of then-year dollars

|

DOD Military (051) |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

Budget Control Act of 2011 |

531 |

521 |

530 |

540 |

550 |

563 |

575 |

588 |

601 |

614 |

|

Budget Control Act of 2011 after revision (sequestration) |

531 |

473 |

480 |

490 |

500 |

513 |

525 |

537 |

551 |

564 |

|

American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 |

531 |

495* |

475* |

490 |

500 |

513 |

525 |

537 |

551 |

564 |

|

Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 |

531 |

495 |

496* |

496* |

500 |

513 |

525 |

537 |

551 |

564 |

|

Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 |

531 |

495 |

496 |

496 |

522* |

526* |

525 |

537 |

551 |

564 |

|

*[Bold-italics] indicates a statutory change was made to the original BCA limits. |

||||||||||

Source: CRS estimate based on P.L. 112-240, P.L. 113-67, and P.L. 114-74; CBO Final Sequestration Report for Fiscal Year 201; OMB Historical Table 5.1, Budget Authority by Function and Subfunction: 1976-2021.

Notes: The budget for DOD military activities (051) is a subset of the national defense budget (050), shown in Table 1 and has historically constituted approximately 95% of the national defense budget request.

What is a sequester?22

A sequester provides for the enforcement of budgetary limits established in law through the automatic cancellation of previously enacted spending, making largely across-the-board reductions to nonexempt programs, activities, and accounts. A sequester is implemented through a sequestration order issued by the President as required by law. The purpose of sequestration is to deter enactment of legislation violating the spending limits or, in the event that such legislation is enacted violating these spending limits, to automatically reduce spending to the limits specified in law. Each statutory limit—defense and nondefense—is separately enforced so that the breach of the limit for one category is enforced by a sequester of resources only within that category.

Does the BCA limit Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) funding?

BCA after automatic revision

American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012

Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013

Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015

Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018

Notes: Bold and shaded figures indicate statutory changes. Figures do not include funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), emergencies, or disaster relief. The BCA as amended provided for "security" and "nonsecurity" categories in FY2012 and FY2013: italicized figures denote CRS estimates of budget authority for defense and nondefense categories in those years. Small changes in budget authority beginning in FY2016 are caused by adjustments in the annual proportional allocations of automatic enforcement measures as calculated by OMB: for more information on these adjustments, see CBO, Estimated Impact of Automatic Budget Enforcement Procedures Specified in the Budget Control Act, September 2011. This table is an abridged version of one that originally appeared in CRS Report R44874, The Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed].The BCA stipulates that certain discretionary funding, such as appropriations designated as emergency requirements or Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), allow for an upward adjustment of the discretionary limits. In essence, OCO funding is therefore described as being

555

546

556

566

577

590

603

616

630

644

555

492

501

511

522

535

548

561

575

589

555

518

497

511

522

535

548

561

575

589

555

518

520

521

523

536

549

562

576

590

555

518

520

521

548

551

549

562

576

590

555

518

520

521

548

551

629

647

576

Sources: CBO, letter to the Honorable John A. Boehner and Honorable Harry Reid estimating the impact on the deficit of the Budget Control Act of 2011, August 2011; CBO, Final Sequestration Report for Fiscal Year 2012, January 2012; CBO, Final Sequestration Report for Fiscal Year 2013, March 2013; CBO, Final Sequestration Report for Fiscal Year 2014, January 2014; CBO, Final Sequestration Report for Fiscal Year 2016, December 2015, CBO, Sequestration Update Report: August 2017, August 2017; CBO, Cost Estimate for Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, February 2018.

591

"exempt" from the discretionary spending limits.

The BCA does not define what constitutes OCO funding. Instead, it includes a requirement that Congress designate spending as being OCOOCO spending on an account-by-account basis, and that the President subsequently designate the spending as OCOsuch. Further, the BCA does not limit the level or amount of spending that may be designated as OCO.

The designation of certain war-related activities and expenses as OCO requirements has shifted over time, reflecting differingdifferent viewpoints about the extent, nature, and duration of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. conflicts in countries such as Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria.24 Recently, Congress and thethe President have designated as "OCO" funds for a variety of activities that had previously been containedfunding for OCO that includes activities previously in the DOD base budget.2325 By designating funding for ongoing activities not directly related to contingency operations as "OCO," Congress and the President can effectively continue to increase topline defense, foreign affairs, and other related discretionary spending, without triggering sequestration.24

How has defense spending changed since enactment of the BCA?

The BCA discretionary limits were projected to reduce the level of national defense (function 050) spending for the decade (FY2012-FY2021) by about 14% or $860 billion compared to continuing the FY2011 enacted level in real terms (steady-state spending with an adjustment for inflation).25 The absence of legislation to reduce the federal budget deficit by at least $1.2 trillion triggered the sequestration process in 2013. In accordance with the BCA, President Obama ordered the sequestration of budgetary resources across nonexempt federal government accounts on March 1, 2013—five months into the fiscal year. DOD was required to apply a $37 billion sequester to $528 billion in available (subfunction 051) budgetary resources—a reduction of 7%.

Figure 3 compares CBO projections of FY2012-FY2021 discretionary defense outlays in January 2011, months before BCA enactment, with actual data and their January 2017 forecast. The figure illustrates a reduction in actual and projected defense spending over that time period, ranging from 0.41% of GDP in FY2012 to 0.95% of GDP in FY2018.

Figure 4 shows inflation-adjusted defense outlays from FY1962 to FY2021 and reflects 6.7% reduction in projected defense outlays during the period of the BCA (FY2012-FY2021). CBO projects the defense outlays to decline from 18% of the federal budget in FY2011 to 13% by FY2021 as mandatory spending and net interest are expected to reach 73.4% of the federal budget by that time (see Figure 1).26

BCA Effects on the DOD Military (051) Budget

The budget plan submitted with the President's FY2012 budget may provide a reference point for the BCA's effect on DOD military (051) spending, as it was the last budget submitted to Congress prior to enactment of the BCA. The Future Years Defense Program (FYDP), submitted to Congress in conjunction with the budget request, contains information on programmed dollars, manpower and force structure over a 5-year period.27

CBO issued its long-term projection for DOD spending based on the 2012 FYDP in June 2011, two months prior to enactment of the BCA.28 Using the CBO projections based on the FY2012 FYDP as a baseline, Figure 5 provides a comparison of the FY2012 budget request to actual appropriations provided in accordance with the BCA limits. The FY2012 budget request included $553 billion for DOD military (051). Based on that, CBO projected a budget of $602 billion for DOD in FY2017. The FY2017 BCA limit of $526 billion is $76.0 billion (12.6%) below the June 2011 CBO projection for FY2017. Over the period FY2012-FY2021, the projected BCA limits on DOD are $714.0 billion (12.0%) below the June 2011 CBO projections for the period.

billions of then-year dollars |

|

|

Source: CRS analysis the BCA (P.L. 112-25) as amended, defense appropriations acts for fiscal year 2013-2016 and CBO's Long Term Implications of FY2012 Future Years Defense Program, Table A-1, June 2011. |

For information on the broader effects of the BCA, see CRS Report R42506, The Budget Control Act of 2011 as Amended: Budgetary Effects, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed].

Would appropriations authorized by the FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act conform to the BCA limits?

The National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2017 (S. 2943/P.L. 114-328) was enacted December 23, 2016 and authorized $543.4 billion for programs under the jurisdiction of the House and Senate Armed Services Committees. Authorizations of discretionary appropriations–such as the NDAA–do not provide budget authority, and therefore, cannot trigger a sequester for violation of the discretionary spending limits. In authorizing defense appropriations for FY2017, P.L. 114-238 corresponds to the broader national defense (function 050) BCA limit of $551 billion.29

The House-passed version of the FY2017 NDAA (H.R. 4909) would have dedicated $23.1 billion of OCO-designated funding to DOD base budget purposes—$18.0 billion more than the Obama Administration proposed. Such funding would not have been subject to the BCA limits. However, the Administration and the congressional minority leadership objected to providing defense funding for base budget requirements in excess of the defense spending limit unless it was accompanied by a comparable increase in funding for nondefense, base budget programs.30 Negotiations between the House and Senate NDAA conferees resulted in the allocation of $8.3 billion in OCO-designated funding for base requirements—$5.2 billion stemming from the Administration's request and $3.2 billion added during the conference negotiations (see Table 3).31

Table 3. FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 4909, S. 2943)

billions of dollars of discretionary budget authority

in the jurisdiction of the Armed Services Committees

|

Title |

Budget Request |

House-passed H.R. 4909 |

|

| ||||||||

|

Base Budget |

|

|

|

| ||||||||

|

OCO for OCO purposes |

|

|

|

| ||||||||

|

OCO for base budget purposes a |

|

|

|

| ||||||||

|

Subtotal: DOD OCO Budget |

|

|

|

| ||||||||

|

Total |

|

|

|

|

Source: H.Rept. 114-537, H.R. 4909, S.Rept. 114-255, and S. 2943.

Notes: Totals may not reconcile due to rounding. Includes only those accounts under the jurisdictions of the House and Senate Armed Services Committees.

a. In its report on S. 2943, the Senate Armed Services Committee did not identify OCO funding that was requested or authorized for base budget purposes.

Would proposed FY2017 defense appropriations conform to the BCA limits?

Congressional action on the FY2017 defense appropriations bill has not been completed. DOD has operated under continuing resolutions thus far in FY2017 (P.L. 114-223 /P.L. 114-254), which expire April 28, 2017.32 The rate of operations provided under the continuing resolution is based on the FY2016 appropriated level. CBO has projected the level of spending provided in these continuing resolutions to be below the BCA spending limit for FY2017.33

Much like the House-passed NDAA, the first House-passed Defense Appropriations Act for 2017 (H.R. 5293) would have provided for additional OCO funding to be used for base budget requirements ($23.1 billion). The Senate committee-reported bill (S. 3000) bill did not.34

On March 2, 2017, H.R. 1301 was introduced as the "final version" of the FY2017 Defense Appropriations bill and reflects an agreement between the House and Senate on defense appropriations for FY2017 (see Table 4).35 The bill appears to be consistent with the FY2017 NDAA (P.L. 114-328) and, if enacted in its current form, would likely comply with the BCA limits.

Table 4. FY2017 Defense Appropriations Act (H.R. 5293, S. 3000, and H.R. 1301)

billions of dollars of discretionary budget authority in the jurisdiction of the Subcommittees on Defense

|

Title |

| |||

|

DOD Base Budget (051) |

$511.2 |

$510.6 |

$509.5 |

$509.6 |

|

OCO for OCO purposes |

$53.7 |

$43.0 |

$58.9 |

$61.8 |

|

$5.1 |

$15.7 |

— |

— |

|

Subtotal: DOD OCO Budget |

$64.6 |

$58.6 |

$58.6 |

$61.8 |

|

$569.9 |

$569.3 |

$568.1 |

$571.5 |

Source: H.Rept. 114-577, H.R. 5293, S.Rept. 114-263, S. 3000, H.R. 1301, and the Explanatory Statement to Accompany H.R. 1301, at https://rules.house.gov/bill/115/hr-130.

Notes: Totals may not reconcile due to rounding. Includes only those accounts under the jurisdiction of the Defense Appropriations Subcommittees.

a. Includes the November 2016 OCO Budget Amendment.

b. Neither the report to accompany S. 3000, nor the Explanatory Statement to Accompany H.R. 1301 identifies OCO funding that was requested or authorized for base budget purposes.

c. Includes the November 2016 OCO Budget Amendment.

Trump Administration Defense Budget Proposals

On March 16, 2017, the Trump Administration released two defense budget proposals—a topline proposal for national defense discretionary spending for FY2018 as part of the Administration's Budget Blueprint for Federal spending, and a detailed request for additional funding for DOD military activities for FY2017.36

The Budget Blueprint represents a $603 billion request for national defense (function 050) discretionary budget authority for FY2018 base budget requirements and $65 billion for OCO. In conjunction with the proposal for FY2018, the Trump Administration also requested $30 billion for FY2017 DOD military activities (budget subfunction 051) in addition to the amounts requested by the Obama Administration. Of this amount, $24.9 billion is slated for base budget activities and $5.1 billion is associated with OCO. The Trump Administration's proposals exceed the current BCA limits for both FY2017 and FY2018. For more information see CRS Report R44806, The Trump Administration's March 2017 Defense Budget Proposals: Frequently Asked Questions, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed].

Author Contact Information

Footnotes

| 1. |

Discretionary budget authority is authority provided under annual appropriation acts, which are under the control of the House and Senate Appropriations Committees. By contrast, mandatory–or direct– budget authority is generally governed by statutory criteria and it is not normally set by annual appropriation acts. Mandatory spending includes entitlement programs such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. For more information see Congressional Budget Office, Frequently Asked Questions about CBO Cost Estimates, https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/ce-faq. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. |

For more information see CRS Report R42972, Sequestration as a Budget Enforcement Process: Frequently Asked Questions, by [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. |

For more information on federal budget functions see CRS In Focus IF10618, Defense Primer: The National Defense Budget Function (050), by [author name scrubbed]. For more information on funding for Overseas Contingency Operations see CRS Report R44519, Overseas Contingency Operations Funding: Background and Status, coordinated by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. |

Estimate calculated by CRS using CBO and OMB data. A detailed breakout of that estimate may be found in Table 6 of CRS Report R42506, The Budget Control Act of 2011 as Amended: Budgetary Effects, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. |

CBO, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2017 to 2027, January 24, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. |

For more information on mandatory spending see CRS Report R44763, Present Trends and the Evolution of Mandatory Spending, by [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7. |

OMB Historical Table 8.1 and CBO, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2017 to 2027, January 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8. |

CBO, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2017 to 2027, January 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9. |

Open letter from eighty-five national security experts and former government officials: Elliot Abrams, David Adesnik, and Michael Auslin, et al. to John Boehner, Speaker of the House, and Mitch McConnell, Senate Majority Leader, et al., February 24, 2015, available at http://www.foreignpolicyi.org/content/national-security-leaders-urge-congress-increase-defense-spending. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10. |

Michael Shindler, "Don't Let Defense Wreck the Budget," Real Clear Defense, February 23, 2017. For more information on federal deficits and debt, see CRS Report R44383, Deficits and Debt: Economic Effects and Other Issues, by [author name scrubbed] . |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11. |

Senator John McCain, "Restoring American Power: Recommendations for the FY2018-FY2022 Defense Budget," January 16, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Trump Administration's initial FY2019 DOD budget request, released on February 12, 2018, included $89.0 billion designated for OCO. In a budget amendment published April 13, 2018, the Administration removed the OCO designation from $20.0 billion of funding in the initial request, in effect, shifting that amount into the base budget request after Congress agreed to raise the spending caps. In a statement on the budget amendment, White House Office of Management and Budget Director Mick Mulvaney said the FY2019 budget request fixes "long-time budget gimmicks" in which OCO funding has been used for base budget requirements. Beginning in FY2020, "the Administration proposes returning to OCO's original purpose by shifting certain costs funded in OCO to the base budget where they belong," he wrote.27 What are the BCA limits on the Department of Defense (DOD)?Department of Defense (DOD)-Military activities (budget subfunction 051) historically constitute approximately 95% of the national defense budget (function 050).28 Although the BCA does not establish limits on subfunctions (051, 053 and 054), the BCA limits on national defense have, in practice, been proportionally applied to subfunctions. CRS estimates the BCA limits on DOD-Military base budget activities at approximately $600 billion in FY2018, $617 billion in FY2019, $549 billion in FY2020, and $564 billion in FY2021. How have the defense spending caps changed over time? The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123), enacted on February 9, 2018, amended the BCA to raise defense discretionary spending caps for FY2018 and FY2019, with increases more than three times larger than previous changes (see Figure 2). To date, CRS estimates Congress has amended the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25) to increase discretionary defense spending limits by a total of $264 billion (thus lowering their deficit-reduction effect by a corresponding amount). The increases over previous caps break down as follows:Figure 2. Changes to BCA Limits on National Defense (050) Discretionary Budget Authority, FY2012-FY2021 (in billions of dollars) Sources: Data on BCA limits from Table 1; Overseas Contingency Operations and emergency funding from DOD, National Defense Budget Estimates for FY2019, Table 2-1: Base Budget, War Funding and Supplementals; and OMB, Budget of the U.S. Government for Fiscal Year 2019, Table S-7: Proposed Discretionary Caps for 2019 Budget; 2011 level from CBO, The Budget and Economic Outlook: An Update, Table 1-6: Illustrative Paths for Discretionary Budget Authority Subject to the Caps Set in the Budget Control Act of 2011.Notes: Automatic defense caps reflect levels established under automatic revision of the BCA; revised defense caps reflect levels established under American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA; P.L. 112-240), Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (BBA 2013; P.L. 113-67), Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015; P.L. 114-74), and Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018; P.L. 115-123). OCO/emergency funding reflects DOD levels. 2011 level assumes growth at the rate of inflation. In 2011, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated discretionary budget authority for the national defense budget function (050), excluding funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), would total $6.26 trillion over the 10-year period from FY2012 through FY2021, assuming the 2011 level would grow at the rate of inflation (see Figure 2).30 Based on this benchmark, CRS estimates the automatic reductions to the initial caps of the BCA would have decreased projected discretionary defense base budget authority by approximately $868 billion (14%) to $5.39 trillion over the decade—and the caps as amended would reduce projected defense discretionary base budget authority by approximately $604 billion (10%) to $5.65 trillion over the period.31 What is a sequester? A sequester provides for the enforcement of budgetary limits established in law through the automatic cancellation of previously enacted spending, making largely across-the-board reductions to nonexempt programs, activities, and accounts. A sequester is implemented through a sequestration order issued by the President as required by law. The purpose of sequestration is to deter enactment of legislation violating the spending limits or, in the event that such legislation is enacted violating these spending limits, to automatically reduce spending to the limits specified in law. Each statutory limit—defense and nondefense—is separately enforced so that the breach of the limit for one category is enforced by a sequester of resources only within that category.32The absence of legislation to reduce the federal budget deficit by at least $1.2 trillion triggered the sequestration process in 2013. In accordance with the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25), then-President Barack Obama ordered the sequestration of budgetary resources across nonexempt federal government accounts on March 1, 2013—five months into the fiscal year. DOD was required to apply a $37 billion sequester to $528 billion in available (subfunction 051) budgetary resources—a reduction of 7%. Can the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) trigger a sequester?Legislation authorizing discretionary appropriations, such as the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), does not provide budget authority and therefore cannot trigger a sequester for violating discretionary spending limits.33 A sequester will occur only if either the defense or nondefense discretionary spending limits are exceeded in enacted appropriations bills.34 How has defense discretionary spending changed since enactment of the BCA? Nominal defense discretionary outlays, including funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO), decreased from $671 billion in FY2012 to $590 billion in FY2017, a decline of $80 billion (12%). They are projected to reach $655 billion in FY2021, a decline of $16 billion (2%) from FY2012.35 Adjusting for inflation (in constant FY2018 dollars), defense discretionary outlays peaked at $784 billion in FY2010 during the height of the U.S.-led wars in Iraq and Afghanistan (see Figure 3).36 Following enactment of the BCA, defense discretionary outlays decreased from $734 billion in FY2012 to $599 billion in FY2017, a decline of $135 billion (18%) in inflation-adjusted dollars. Despite a projected uptick in FY2018 and FY2019, they are projected to reach $620 billion in FY2021, $114 billion (16%) less than the FY2012 level in inflation-adjusted dollars. The figure also shows defense discretionary outlays as a percentage of all federal outlays. Over the past half century, federal outlays devoted to discretionary defense programs have trended downward from nearly half of total outlays in FY1962 during the Vietnam War, to 19% in FY2012 after enactment of the BCA, to 15% in FY2017. They are projected to further decline to 13% in FY2021, as mandatory spending and net interest consume a larger share of all federal outlays (see also Figure 1).37Figure 3. National Defense (050) Discretionary Outlays, FY1962-FY2023 (in billions of FY2018 dollars and as percentage of total outlays)

|

Source: OMB Historical Tables, Table 8.1, Outlays by Budget Enforcement Act Category: 1962-2023, Table 8.4, Outlays by Budget Enforcement Act Category as Percentages of GDP: 1962-2023, and CBO, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2018 to 2028. Amounts adjusted for inflation using GDP (Chained) Price Index from OMB Historical Tables, Table 10.1, Gross Domestic Product and Deflators Used in the Historical Tables: 1940-2023. Notes: Outlays include programs designated as Overseas Contingency Operations and other adjustments to the discretionary budget authority limits established by the BCA as amended. Similarly, discretionary defense outlays as a share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) have trended downward, from 9.1% of GDP in 1968 to 4.2% of GDP in FY2012 after enactment of the BCA to 3.1% of GDP in FY2017. By FY2021—the last year of the BCA limits—CBO projects discretionary defense outlays to decline to 2.9% of GDP.38 The deficit-reduction effects of the BCA have been offset by other factors affecting the federal budget.39 While the deficit decreased from $1.1 trillion (6.8% of Gross Domestic Product) in FY2012 to $665 billion (3.5% of GDP) in FY2017, it is projected to increase to $1.1 trillion (4.9% of GDP) in FY2021.40 Over the same period, federal debt held by the public has increased from $11.3 trillion (70.4% of GDP) in FY2012 to $14.7 trillion (76.5% of GDP) in FY2017 and is projected to further increase to $19 trillion (83.1% of GDP) in FY2021.41 What are the Administration's plans for defense spending?The Trump Administration has proposed increasing defense spending beyond the statutory limits of the Budget Control Act of 2011 (P.L. 112-25) as amended. The President's FY2019 budget request proposed increasing caps on defense discretionary base budget authority by $84 billion (15%) to $660 billion in FY2020 and by $87 billion (15%) to $677 billion in FY2021. It also proposed defense funding for Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) totaling $73 billion in FY2020 and $66 billion in FY2021.42 AcknowledgementsThis is an update to a report originally authored by [author name scrubbed], former CRS Specialist in Defense Readiness and Infrastructure. It references research previously compiled by [author name scrubbed], former CRS Specialist in U.S. Defense Policy and Budget; [author name scrubbed], CRS Analyst in Public Finance; and [author name scrubbed], CRS Specialist on Congress and the Legislative Process. [author name scrubbed], Research Assistant, helped compile the graphics. Author Contact Information [author name scrubbed], Analyst in U.S. Defense Budget

([email address scrubbed], [phone number scrubbed])

Footnotes1.

|

|

See CRS In Focus IF10618, Defense Primer: The National Defense Budget Function (050), by [author name scrubbed]. 2.

|

|

See CRS Report 98-721, Introduction to the Federal Budget Process, coordinated by [author name scrubbed]. 3.

|

|

OMB, Historical Tables, Table 8.1, Outlays by Budget Enforcement Act Category: 1962–2023, and CBO, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2018 to 2028, April 2018, and CBO, 10-Year Budget Projections, Table 2-4: Discretionary Spending Projected in CBO's Baseline, and Table 4-1: at https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53651. For more information on mandatory spending trends, see CRS Report R44763, Present Trends and the Evolution of Mandatory Spending, by [author name scrubbed]. 4.

|

|

CRS Report R44874, The Budget Control Act: Frequently Asked Questions, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. 5.

|

|

OMB, Final Sequestration Report to the President and Congress for Fiscal Year 2018, April 6, 2018, at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/2018_final_sequestration_report_april_2018_potus.pdf. 6.

|

|

See CRS Report 98-721, Introduction to the Federal Budget Process, coordinated by [author name scrubbed]. 7.

|

|

OMB, Final Sequestration Report to the President and Congress for Fiscal Year 2012, January 18, 2012, at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/legislative_reports/sequestration/sequestration_final_jan2012.pdf. 8.

|

|

Open letter from eighty-five national security experts and former government officials: Elliot Abrams, David Adesnik, and Michael Auslin, et al. to John Boehner, then-speaker of the House, and Mitch McConnell, Senate Majority Leader, et al., February 24, 2015. 9.

|

|

Frederico Bartels, "America's defense budget is yet again held hostage by Congress," The Hill, November 2, 2017, at http://thehill.com/opinion/national-security/358385-congress-needs-to-do-its-job-and-properly-fund-americas-defense. See also Footnote 4. 10.

|

|

Senator John McCain, "Restoring American Power: Recommendations for the FY2018-FY2022 Defense Budget," January 16, 2017, at https://www.mccain.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/2017/1/restoring-american-power-sasc-chairman-john-mccain-releases-defense-budget-white-paper; and Ben Werner, "Thornberry: Budget Control Act Limits on Defense Spending Could End Soon," USNI News, September 6, 2017, at https://news.usni.org/2017/09/06/thornberry-budget-control-act-limits-defense-spending-end-soon. 11.

|

|

Michael Shindler, "Don't Let Defense Wreck the Budget," Real Clear Defense, February 23, 2017, at https://www.realcleardefense.com/articles/2017/02/23/dont_let_defense_wreck_the_budget_110857.html. For more information on deficits and debt, see CRS Report R44383, Deficits and Debt: Economic Effects and Other Issues, by [author name scrubbed]. 12.

|

|

Mark Meadows, "Rep. Meadows' Statement on Budget Agreement," press release, February 9, 2018, at https://meadows.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=815. Final roll call vote results for the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 at http://clerk.house.gov/evs/2018/roll069.xml. 13.

|

|

Lawrence J. Korb, "Trump's Defense Budget," Center for American Progress, February 28, 2018, at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/security/news/2018/02/28/447248/trumps-defense-budget/. |

U.S. Congress, House Committee on Armed Services, Statement by General Daniel B. Allyn, Vice Chief of Staff, United States Army, Hearing on The State of the Military, 115th Cong., 1st sess., February 7, 2017. |

||

|

Congressman Mike Turner, "Trump Calls for Repeal of Sequestration; Turner: Repeal Gains Groundswell of Support," press release, March 1, 2017, https://turner.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/trump-calls-for-repeal-of-sequestration-turner-repeal-gains-groundswell. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

The BCA was amended by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA; P.L. 112-240), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (BBA 2013; P.L. 113-67, referred to as the Murray-Ryan agreement), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015; P.L. 114-74), and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018; P.L. 115-123). For more information on the effect of each, see CRS Insight IN10861, Discretionary Spending Levels Under the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. 16.

|

|

CBO, Letter from then-Director Douglas W. Elmendorf to then-Speaker of the House John Boehner and then-Majority Leader of the Senate Harry Reid, "CBO Estimate of the Impact on the Deficit of the Budget Control Act of 2011," August 1, 2011; http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/123xx/doc12357/budgetcontrolactaug1.pdf. 17.

|

|

Legislation amending the BCA included equal increases to defense and nondefense discretionary spending caps until the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123), which included a larger increase to defense than nondefense. For more on the so-called parity principle, see CRS In Focus IF10657, Budgetary Effects of the BCA as Amended: The "Parity Principle", by [author name scrubbed]. For more on the "security" category that predated the "defense" category, see the "Background" section above. 18.

|

|

For more information on sequestration, see CRS Report R42972, Sequestration as a Budget Enforcement Process: Frequently Asked Questions, by [author name scrubbed]. 19.

|

|

For more information on the national defense budget function, see the "Background" section above. For more information on OCO, see CRS Report R44519, Overseas Contingency Operations Funding: Background and Status, coordinated by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. 20.

|

|

These automatic reductions to the original BCA limits are often referred to as sequestration but technically are not because Congress can allocate funding within the caps. See footnote 18. 21.

|

|

See footnote 15. 22.

|

|

For more on the "security" category that predated the "defense" category, see the "Background" section above. 23.

|

|

The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-74) established non-binding targets for OCO spending in FY2016 and FY2017. 24.

|

|

See CRS Report R44519, Overseas Contingency Operations Funding: Background and Status, coordinated by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

Office of Management and Budget, America First: A Budget Blueprint to Make America Great Again, March 16, 2017 and Department of Defense Comptroller, Overview—Request for Additional FY2017 Appropriations, March 16, 2017. |

||||||||||

| 15. |

U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Appropriations, Subcommittee on Department of Defense, Department of Defense Budget and Readiness, 115th Cong., 1st sess., March 22, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16. |

H.R. 1745 is cosponsored by Representatives Conyers, Lujan Grisham, McGovern, Jayapal and DelBene. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17. |

Discretionary budget authority is authority provided under annual appropriation acts, which are under the control of the House and Senate Appropriations Committees. By contrast, mandatory–or direct– budget authority is generally governed by statutory criteria and it is not normally set by annual appropriation acts. Mandatory spending includes entitlement programs such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. For more information see Congressional Budget Office, Frequently Asked Questions about CBO Cost Estimates, https://www.cbo.gov/about/products/ce-faq. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18. |

The national defense budget function is comprised of DOD military (subfunction 051), defense-related programs in the Department of Energy for nuclear weapons (subfunction 053), and defense-related activities of the Department of Justice (subfunction 054). See OMB Historical Table 5.1, Budget Authority by Function and Subfunction: 1976-2021. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19. |

For more information see CRS Report R44519, Overseas Contingency Operations Funding: Background and Status, coordinated by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20. |

Required by section 254 of the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act of 1985 (2 U.S.C. 904). |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21. |

The BCA was amended by the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA/P.L. 112-240), the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 (BBA 2013/P.L. 113-67, referred to as the Murray-Ryan agreement), and the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015/P.L. 114-74). For more information on the effect of each of the amendments, see CRS Insight IN10389, Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015: Adjustments to the Budget Control Act of 2011, by [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22. |

Contributed by Megan Lynch, CRS Specialist on Congress and the Legislative Process. For more information on sequestration, see CRS Report R42972, Sequestration as a Budget Enforcement Process: Frequently Asked Questions, by [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The term base budget is generally used to refer to funding for planned or regularly occurring costs to man, train and equip the military force. This is used in contrast to amounts needed for contingency operations or DOD response to emergencies |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Section 1501 of National Defense Authorization Act for FY2017 (P.L. 114-328) stipulates that certain amounts designated as OCO are to be used for base budget requirements. Such amounts would not be counted against the BCA limits. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 25. |

CBO, Letter from Douglas Elmendorf, Director to Speaker of the House, John Boehner and Majority Leader of the Senate, Harry Reid, "CBO Estimate of the Impact on the Deficit of the Budget Control Act of 2011," August 1, 2011; http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/ftpdocs/123xx/doc12357/budgetcontrolactaug1.pdf. The defense share ("security" category) is half of the total reduction of $2.1 trillion over the decade. CBO and OMB generally compare budget requests to a current services baseline that reflects the prior year's enacted level plus an adjustment for inflation. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 26. |

CBO, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2017 to 2027, January 24, 2017. See also CRS Report R44763, Present Trends and the Evolution of Mandatory Spending, by [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 27. |

For more information on the defense budget process, see CRS In Focus IF10429, Defense Primer: Planning, Programming, Budgeting and Execution Process (PPBE), by [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 28. |

Congressional Budget Office, Long-Term Implications of the FY2012 Future Years Defense Program, June 2011, available at https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/112th-congress-2011-2012/reports/06-30-11_fydp.pdf. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 29. |

The amounts authorized by the NDAA fund activities under the jurisdiction of the House and Senate Armed Services Committees and do not encompass the entire national defense budget (function 050). In addition to the $543.4 base discretionary amounts authorized by the NDAA, $7.8 billion of the 050 request is either authorized elsewhere or is not subject to additional authorization. For more detail see summary table in H.Rept. 114-840, p. 1332, Base National Defense Discretionary Programs that Are Not In the Jurisdiction of the Armed Services Committee or Do Not Require Additional Authorization. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 30. |

See OMB, "Statement of Administration Policy on H.R. 4909, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2017," May 16, 2016, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/legislative/sap/114/saphr4909r_20160516.pdf; and Senator Harry Reid, "Reid: Senate Must Give Defense Bill Deliberative Approach It Deserves," press release, May 25, 2016, http://www.reid.senate.gov/press_releases/2016-05-25-reid-senate-must-give-defense-bill-deliberative-approach-it-deserves#.V1GXYE0UVFo. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 31. |

For more information on the FY2017 NDAA see CRS Report R44497, Fact Sheet: Selected Highlights of the FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 4909, S. 2943), by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 32. |

For more information on the continuing resolution and the effect on defense spending see CRS Report R44636, FY2017 Defense Spending Under an Interim Continuing Resolution (CR): In Brief, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 33. |

Congressional Budget Office, CBO estimate of Senate Amendment 5082 to H.R. 5325, Continuing Appropriations and Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2017, and Zika Response and Preparedness Act, September 23, 2016, and CBO estimate for the Further Continuing and Security Assistance Appropriations Act, 2017, December 7, 2016. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 34. |

For more information on congressional actions related to FY2017 defense appropriations see CRS Report R44531, FY2017 Defense Appropriations Fact Sheet: Selected Highlights of H.R. 5293, S. 3000, and H.R. 1301, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 35. |

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Appropriations, "Fiscal Year 2017 Defense Bill to Head to the House Floor," press release, March 2, 2017. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 36. | DOD, Defense Budget Overview: United States Department of Defense Fiscal Year 2019 Budget Request, originally published February 12, 2018, and revised February 13, 2018; OMB, Estimate #1-FY2019 Budget Amendments, April 18, 2018; and OMB, Addendum to the FY2019 Budget, February 12, 2018. See CRS In Focus IF10618, Defense Primer: The National Defense Budget Function (050), by [author name scrubbed]. CBO, The Budget and Economic Outlook: An Update, Table 1-6, Illustrative Paths for Discretionary Budget Authority Subject to the Caps Set in the Budget Control Act of 2011, August 2011. This paragraph was contributed by [author name scrubbed], CRS Specialist on Congress and the Legislative Process. See CRS Report R42972, Sequestration as a Budget Enforcement Process: Frequently Asked Questions, by [author name scrubbed]. For more information on the NDAA, see CRS In Focus IF10516, Defense Primer: Navigating the NDAA, by [author name scrubbed] and [author name scrubbed]. See CRS Report R42972, Sequestration as a Budget Enforcement Process: Frequently Asked Questions, by [author name scrubbed]. See footnote 3. See footnote 3 and OMB, Historical Tables, Table 10.1, Gross Domestic Product and Deflators Used in the Historical Tables: 1940–2023. See footnote 3. OMB, Historical Tables, Table 8.4, Outlays by Budget Enforcement Act Category as Percentages of GDP. See CBO references in footnote 3. For example, CBO in 2018 increased projected deficits compared to a previous estimate due to recent tax and spending legislation, including the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (P.L. 115-97), Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-123), and the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2018 (P.L. 115-141). OMB, Historical Tables, Table 1.3, Summary of Receipts, Outlays, and Surpluses or Deficits in Current Dollars, Constant (FY2009) Dollars, and as Percentages of GDP, 1940-2023. See CBO references in footnote 3. OMB, Historical Tables, Table 7.1, Federal Debt at the End of Year: 1940–2023. See CBO references in footnote 3. |