U.S. Assistance for Sub-Saharan Africa: An Overview

Changes from May 20, 2020 to August 30, 2022

This page shows textual changes in the document between the two versions indicated in the dates above. Textual matter removed in the later version is indicated with red strikethrough and textual matter added in the later version is indicated with blue.

U.S. Assistance tofor Sub-Saharan Africa: An

August 30, 2022

Overview

Tomas F. Husted,

Overview. Congress authorizes, appropriates, and oversees U.S. foreign assistance for sub-

Coordinator

Saharan Africa (“Africa”), which typically receives about a quarter of all U.S. foreign assistance

Analyst in African Affairs

(including humanitarian assistance) annually. Annual State Department- and U.S. Agency for

International Development (USAID)-administered assistance to Africa increased more than five-

Alexis Arieff

fold in the 2000s, largely due to increases in global health spending to help combat HIV/AIDS.

Specialist in African Affairs

Over the past decade, funding levels have fluctuated between $6.5 and $7.5 billion annually. This

does not include funding allocated from global accounts or programs, such as humanitarian assistance, or funds provided through multilateral bodies, such as the United Nations and the

Lauren Ploch Blanchard

World Bank. Other federal entities also administer programs in African countries, including the

Specialist in African Affairs

Millennium Challenge Corporation, Peace Corps, U.S. Development Finance Corporation, and

the Departments of Defense, Health and Human Services, and Agriculture.

Nicolas Cook Specialist in African Affairs

Objectives and Delivery. Unless noted, this report focuses on State Department- and USAID-

administered funds. Over the past decade, approximately 70% of U.S. assistance for Africa has sought to address health challenges, primarily HIV/AIDS. Other assistance has aimed to foster

agricultural development and economic growth; strengthen peace and security; improve education access and social service delivery; and strengthen democracy, human rights, and governance (DRG). Much of this funding is provided under multi-country initiatives focused largely or wholly on Africa, including the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), the President’s Malaria Initiative, Feed the Future, Prosper Africa, and Power Africa.

The Biden Administration. The Biden Administration has articulated priorities for U.S. engagement with Africa that are broadly consistent with those of its predecessors. Stated objectives include advancing global health; enhancing peace and security; promoting mutually beneficial economic growth, trade, and investment; strengthening democracy; and building resilience to address challenges related to health, climate change, food security, and other areas. In its FY2023 Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPS) budget request, the Administration proposed $7.77 billion in assistance specifically for Africa, up from $7.65 billion in FY2021 actual nonemergency allocations. Health programs comprise roughly 75% of the FY2023 proposal, economic growth assistance 12%, peace and security assistance 6%, DRG programs 4%, and education and social service funding 4%. Top recipients would include Nigeria ($610 million), Tanzania ($565 million), Mozambique ($558 million), Uganda ($549 million), and Kenya ($525 million).

Issues for Congress. The 117th Congress is considering the Biden Administration’s FY2023 budget request for Africa as it debates FY2023 appropriations. Congress will evaluate the FY2023 request for Africa in the context of other demands on U.S. attention and resources—including for security, economic, and humanitarian aid for Ukraine and ongoing efforts to combat COVID-19. More broadly, policymakers, analysts, and advocates continue to debate the funding levels, focus, and effectiveness of U.S. assistance programs in Africa. Some Members have questioned whether current assistance for Africa is sufficient and appropriately balanced between sectors given the broad scope of U.S. interests in the region. Congressional debate also has focused on the appropriate approach to U.S. engagement with undemocratic governments in the region, and on the possible unintended consequences associated with U.S. foreign assistance, among other considerations. That comprehensive regional- or country-level breakouts of U.S. assistance are not routinely made available in public budget documents may complicate congressional oversight, inhibit efforts to assess impact, and obscure policy dilemmas. Congress may continue to assess whether executive branch departments and agencies provide sufficient programmatic, funding, and impact evaluation information to Congress to enable effective oversight and timely responses to identified challenges.

Congress has shaped U.S. assistance for Africa through annual appropriations legislation directing allocations for certain activities and countries. Congress has also enacted appropriations provisions and other legislation prohibiting or imposing conditions on aid to specific countries in Africa, and on certain kinds of assistance, on various grounds (e.g., related to trafficking in persons, child soldiers, terrorism, military coups, and religious freedom). Security assistance has been a focus of congressional scrutiny: Congress has restricted certain kinds of support for foreign security forces implicated in human rights abuses, and the 117th Congress has acted to enhance congressional oversight of U.S. security assistance for Africa.

Congressional Research Service

link to page 4 link to page 4 link to page 6 link to page 6 link to page 8 link to page 10 link to page 13 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 15 link to page 15 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 16 link to page 17 link to page 17 link to page 17 link to page 18 link to page 20 link to page 5 link to page 7 link to page 9 link to page 9 link to page 11 link to page 11 link to page 13 link to page 14 link to page 14 link to page 18 link to page 24 U.S. Assistance for Sub-Saharan Africa: An Overview

Contents

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Historic Trends and Key Rationales ................................................................................................ 1 Recent Funding Trends, Objectives, and Delivery .......................................................................... 3

Health Assistance ...................................................................................................................... 3 Economic Growth Assistance.................................................................................................... 5 Peace and Security Assistance................................................................................................... 7 Democracy, Human Rights, and Governance (DRG) ............................................................. 10 Education and Social Services ................................................................................................ 10

Selected Global Assistance for Africa ............................................................................................ 11

Humanitarian Assistance .......................................................................................................... 11 Health Assistance .................................................................................................................... 12 Peace and Security Assistance................................................................................................. 12

Other U.S. Department and Agency Assistance ............................................................................ 13

The Department of Defense (DOD) ........................................................................................ 13 Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) ............................................................................ 13 The Peace Corps ...................................................................................................................... 14 African Development Foundation (USADF) .......................................................................... 14

The Biden Administration and the FY2023 Request ..................................................................... 14

The FY2023 SFOPS Budget Request for Africa ..................................................................... 15

Outlook and Issues for Congress ................................................................................................... 17

Figures Figure 1. U.S. Assistance for Africa, Select State Department and USAID Accounts .................... 2 Figure 2. Health Assistance for Africa in FY2021, by Program Area and Element ........................ 4 Figure 3. Economic Growth Assistance for Africa in FY2021, by Program Area and

Element......................................................................................................................................... 6

Figure 4. Peace and Security Assistance for Africa in FY2021, by Program Area and

Element......................................................................................................................................... 8

Figure 5. DRG Assistance for Africa in FY2021, by Program Area and Element ........................ 10 Figure 6. Education and Social Services Assistance for Africa in FY2021, by Program

Area and Element ........................................................................................................................ 11

Figure 7. The FY2023 Request for Africa, by Account ................................................................. 15

Contacts Author Information ........................................................................................................................ 21

Congressional Research Service

link to page 5 U.S. Assistance for Sub-Saharan Africa: An Overview

Introduction This report is intended to serve as a primer on U.S. foreign assistance funding and programming for sub-Saharan Africa (“Africa”) to inform Congress as it authorizes, appropriates funds for, and oversees such engagement. This report focuses primarily on funds and programs administered by the State Department and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), and includes more limited discussion of select assistance managed by other U.S. departments and agencies. A separate CRS report, CRS Report R45428, Sub-Saharan Africa: Key Issues and U.S. Engagement, discusses U.S. policy toward and engagement in Africa.

Scope and Definitions

Unless otherwise indicated, this report discusses State Department- and USAID-administered assistance allocated specifically for African countries and regional programs. It does not comprehensively discuss funding allocated for African countries via global accounts and programs that are not allocated by country or region in annual State Department Congressional Budget Justifications (CBJs), which provide information on the planned allocation of appropriated assistance.1 Unless otherwise noted, figures refer to actual allocations of funding appropriated in given fiscal year (hereinafter, “allocations”).2

Historic Sub-Saharan Africa: An Overview

Contents

- Introduction

- Recent Assistance Trends and Key Rationales

- U.S. Assistance to Africa: Objectives and Delivery

- Select Assistance Provided through Global Accounts and Programs

- Assistance Administered by Other U.S. Federal Departments and Agencies

- U.S. Aid to Africa During the Trump Administration

- The FY2021 Assistance Request for Africa

- Select Issues for Congress

- Outlook

Figures

- Figure 1. Map of Africa

- Figure 2. U.S. Aid to Africa, Select State Department and USAID Accounts

- Figure 3. U.S. Assistance to Africa in FY2019, by Program Area

- Figure 4. Health Assistance to Africa in FY2019 by Program Area

- Figure 5. Title 22 Security Assistance to Africa FY2015-FY2019, Selected Accounts

- Figure 6. Emergency Food Assistance to Africa, Select Programs

- Figure 7. Allocated and Requested Aid to Africa in FY2016-FY2021, Select Accounts

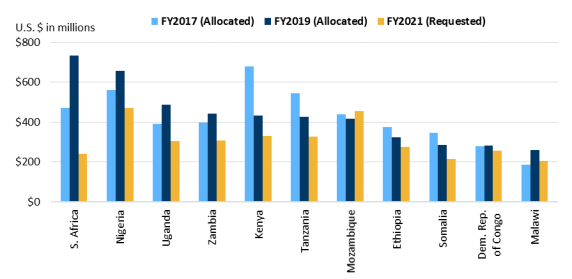

- Figure 8. U.S. Aid to Africa, Top Recipients, Recent Allocations vs. FY2021 Request

Summary

Overview. Congress authorizes, appropriates, and oversees U.S. assistance to sub-Saharan Africa ("Africa"), which received over a quarter of U.S. aid obligated in FY2018. Annual State Department- and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)-administered assistance to Africa increased more than five-fold over the past two decades, primarily due to sizable increases in global health spending and more incremental growth in economic and security assistance. State Department and USAID-administered assistance allocated to African countries from FY2019 appropriations totaled roughly $7.1 billion. This does not include considerable U.S. assistance provided to Africa via global accounts, such as emergency humanitarian aid and certain kinds of development, security, and health aid. The United States channels additional funds to Africa through multilateral bodies, such as the United Nations and World Bank.

Objectives and Delivery. Over the past decade, roughly 70-75% of annual U.S. aid to Africa has sought to address health challenges, notably relating to HIV/AIDS, malaria, maternal and child health, and nutrition. Much of this assistance has been delivered via disease-specific initiatives, including the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the President's Malaria Initiative (PMI). Other U.S. aid programs seek to foster agricultural development and economic growth; strengthen peace and security; improve education access and social service delivery; bolster democracy, human rights, and good governance; support sustainable natural resource management; and address humanitarian needs. What impacts the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic may have for the scale and orientation of U.S. assistance to Africa remains to be seen.

Aid to Africa during the Trump Administration. The Trump Administration has maintained many of its predecessors' aid initiatives that focus wholly or largely on Africa, and has launched its own Africa-focused trade and investment initiative, known as Prosper Africa. At the same time, the Administration has proposed sharp reductions in U.S. assistance to Africa, in line with proposed cuts to foreign aid globally. It also has proposed funding account eliminations and consolidations that, if enacted, could have implications for U.S. aid to Africa. Congressional consideration of the Administration's FY2021 budget request is underway; the Administration has requested $5.1 billion in aid for Africa, a 28% drop from FY2019 allocations. Congress has not enacted similar proposed cuts in past appropriations measures.

Selected Considerations for Congress. Policymakers, analysts, and advocates continue to debate the value and effectiveness of U.S. assistance programs in Africa. Some Members of Congress have questioned whether sectoral allocations are adequately balanced given the broad scope of Africa's needs and U.S. priorities in the region. Concern also exists as to whether funding levels are commensurate with U.S. interests. Comprehensive regional- or country-level breakouts of U.S. assistance are not routinely made publicly available in budget documents, complicating estimates of U.S. aid to the region and congressional oversight of assistance programs.

In addition to authorizing and appropriating U.S. foreign assistance, Congress has shaped U.S. aid to Africa through legislation denying or placing conditions on certain kinds of assistance to countries whose governments fail to meet standards in, for instance, human rights, debt repayment, or trafficking in persons. Congress also has restricted certain kinds of security assistance to foreign security forces implicated in human rights abuses. Some African countries periodically have been subject to other restrictions on U.S. foreign assistance, including country-specific provisions in annual aid appropriations measures restricting certain kinds of assistance. Congress may continue to debate the merits and effectiveness of such restrictions while overseeing their implementation.

Introduction

This report is intended to serve as a primer on U.S. foreign assistance to sub-Saharan Africa ("Africa") to help inform Congress' authorization, appropriation, and oversight of U.S. foreign aid for the region. It focuses primarily on assistance administered by the State Department and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), which administer the majority of U.S. aid to the region. It covers recent funding trends and major focus areas of such assistance, select programs managed by other U.S. agencies and federal entities, and the Trump Administration's FY2021 aid budget request for Africa. In addition to discussing aid appropriations, this report notes a range of legislative measures that have authorized specific assistance programs or placed conditions or restrictions on certain types of aid, or on aid to certain countries. Select challenges for congressional oversight are discussed throughout this report. For more on U.S. engagement in Africa, see also CRS Report R45428, Sub-Saharan Africa: Key Issues and U.S. Engagement.

Definitions. Unless otherwise indicated, this report discusses State Department- and USAID-administered assistance allocated for African countries or for regional programs managed by the State Department's Bureau of African Affairs (AF), USAID's Bureau for Africa (AFR), and USAID regional missions and offices in sub-Saharan Africa. It does not comprehensively discuss funding allocated to African countries via global accounts or programs, which publicly available budget materials do not disaggregate by country or region.1 Except as noted, figures refer to actual allocations of funding appropriated in the referenced fiscal year (hereafter, "allocations"). 2

|

COVID-19 in Africa: Emergent Implications for U.S. Assistance3 This report does not specifically address the implications of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for U.S. assistance to Africa, as the consequences of the pandemic for the scale and orientation of U.S. aid to the region remain to be seen. While the impacts of COVID-19 continue to unfold across the region, several factors may inhibit African countries' capacities to respond to the virus. Many countries have limited disease surveillance and response capabilities, owing in part to shortages of health equipment and personnel. Limited access to safe water may hinder handwashing and other hygienic measures. Physical distancing is a challenge in the high-density settlements where millions of Africans live, as well as in humanitarian settings such as displacement camps. COVID-19's economic impacts also are likely to be substantial in Africa, where many countries rely on commodity exports or tourism—sectors expected to be hard-hit by the pandemic. Several initial analyses have projected that Africa will face an economic contraction in 2020, which would mark the first regional recession in over two decades.4 Africa's oil export-dependent countries, including regional powerhouse Nigeria, face a second threat: a concurrent global oil price collapse initially linked to an oil production competition between Saudi Arabia and Russia. That the pandemic is unfolding simultaneously in developed countries and in other developing regions may limit the availability of donor funds that could help African countries address health and economic challenges. How the COVID-19 pandemic may affect U.S. assistance to Africa remains to be seen. 5 As of early May, the State Department and USAID had announced approximately $269 million in health, humanitarian, and economic and governance aid to support African responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.6 This assistance includes funding for public health information campaigns, laboratory capacity, disease surveillance, water and sanitation, and infection control in healthcare facilities in Africa, along with economic support and education programs. The Administration also has pledged to donate ventilators to several African countries; those deliveries are underway. In addition to assistance provided on a bilateral basis, the United States provides substantial funding to multilateral organizations involved in regional responses to COVID-19, such as United Nations (U.N.) agencies, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the African Development Bank (AfDB). Congressional authorization and appropriation measures will continue to shape U.S. foreign assistance as the pandemic unfolds. |

|

|

Source: General reference map created by CRS. Boundaries may not be authoritative. Mauritius is not shown. |

Recent Assistance Trends and Key Rationales

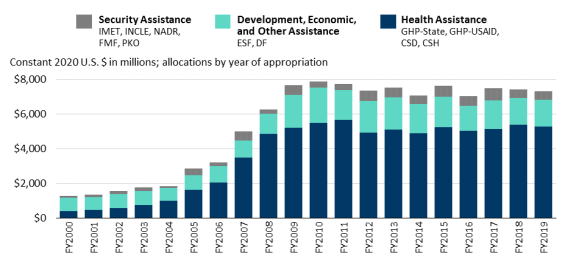

Trends and Key Rationales Africa has received a growing share of annual U.S. foreign assistance funding over the past two decades: the region received 37, accounting for 36% of State Department- and USAID-administered aid obligations in FY2018, up from 28% of global obligations in 2008 and 16% in 1998.7 U.S. aid to Africafunding allocated for specific regions in FY2021 (latest available), up from 31% in 2011 and 10% in 2001.3 U.S. assistance for the region grew markedly during the 2000s (see Figure 1), as Congress appropriated substantial funds to support the President'’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), which the George W. Bush Administration launched in 2003. Development and security aid to Africa also increased during that period, albeit to a lesser extent (see Figure 2). Assistance for Africa plateaued during the Obama Administration, with bipartisan support in Congress. As discussed below, assistance to combat HIV/AIDS remains by far the largest category of U.S. assistance for Africa. Development and security aid for Africa also increased during the 2000s, albeit to a lesser extent. U.S. assistance for Africa was comparatively flat over the past decade, generally fluctuating between $7.06 billion and $8.0 billion in annual allocations, excluding emergency humanitarian assistance and other funding allocated from global accounts and programs. Africa received roughly $7.0 billion in annual U.S. aid allocations in the first three years of the Trump Administration, despite the Administration's repeated proposals to curtail aid to the region.8

Over the past decade, roughly 70% of U.S. assistance to African countries has supported health programs, notably focused on HIV/AIDS, malaria, nutrition, and maternal and child health. U.S. assistance also seeks to encourage economic growth and development, bolster food security, enhance governance, and improve security.

As discussed below, African countries also receive assistance administered by other federal agencies. The United States channels additional funding to Africa through multilateral bodies, such as U.N. agencies and international financial institutions like the World Bank.

Policymakers, analysts, and advocates continue to debate the value and design of assistance programs in Africa. Proponents of such assistance often contend that foreign aid advances U.S. national interests in the region, or that U.S. assistance (e.g., to respond to humanitarian need) reflects U.S. values of charity and global leadership.9 Critics often allege that aid has done little to improve socioeconomic outcomes in Africa overall, that aid flows may have negative unintended consequences (such as empowering undemocratic regimes), or that other countries should bear more responsibility for providing aid to the region.10 Assessing the effectiveness of foreign aid is complex—particularly in areas afflicted by conflict or humanitarian crisis—further complicating such debates.11 Selected considerations concerning U.S. aid to Africa and issues for Congress are discussed in further detail below (see "Select Issues for Congress").

U.S. Assistance to Africa: Objectives and Delivery

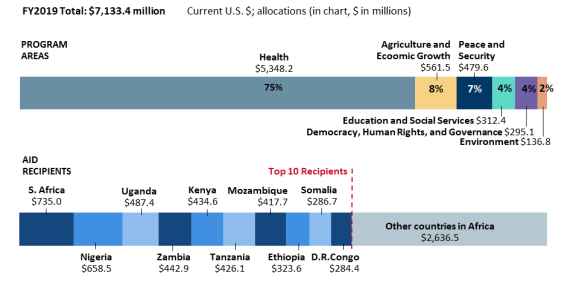

U.S. assistance seeks to address a range of development, governance, and security challenges in Africa, reflecting the continent's size and diversity as well as the broad scope of U.S. policy interests in the region. State Department- and USAID-administered assistance for Africa totaled roughly $7.1 billion in FY2019, not including funding allocated to Africa via global accounts and programs (see "Select Assistance Provided through Global Accounts and Programs," below).

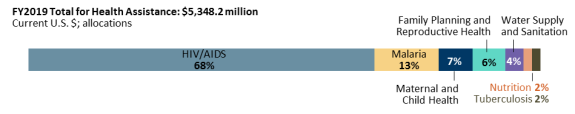

Health. At $5.3 billion, health assistance comprised 75% of U.S. aid to Africa in FY2019.12 The majority of this funding supported HIV/AIDS programs (see Figure 4), with substantial assistance provided through the global President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)—a State Department-led, interagency effort that Congress first authorized during the George W. Bush Administration and reauthorized through 2023 under P.L. 115-305.13 Programs to prevent and treat malaria, a leading cause of death in Africa, constituted the second-largest category of health assistance; such funding is largely provided through the USAID-led President's Malaria Initiative (PMI), which targeted 24 countries in Africa (out of 27 globally) as of 2019.14

|

|

|

Source: CRS calculation based on FY2019 sectoral data provided by USAID, February 2020. |

Beyond disease-specific initiatives, U.S. assistance has supported health system strengthening, nutrition, family planning and reproductive health, and maternal and child health programs. The United States also has supported global health security efforts, including pandemic preparedness and response activities, notably through the U.S.-supported Global Health Security Agenda.15 In recent years, USAID and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) led robust U.S. responses to two Ebola outbreaks on the continent, in West Africa (2014-2016) and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC, 2018-present).16

Agriculture and Economic Growth. U.S. support for economic growth in Africa centers on agricultural development assistance. USAID agriculture programs seek to improve productivity by strengthening agricultural value chains, enhancing land tenure systems and market access road infrastructure, promoting climate-resilient farming practices, and funding agricultural research. Nearly 60% of U.S. agricultural assistance to Africa in FY2019 benefitted the eight African focus countries17 under Feed the Future (FTF)—a USAID-led, interagency initiative launched by the Obama Administration that supports agricultural development to reduce food insecurity and enhance market-based economic growth.18 (There are 12 FTF focus countries worldwide; the initiative supports additional countries under "aligned" and regional programs.) The Global Food Security Act of 2016 (P.L. 114-195, reauthorized through 2023 in P.L. 115-266) endorsed an approach to U.S. agricultural and food assistance similar to FTF.

Other U.S. economic assistance programs support trade capacity-building efforts, economic policy reforms and analysis, microenterprise and other private sector strengthening, and infrastructure development. Since the early 2000s, USAID has maintained three sub-regional trade and investment hubs focused on expanding intra-regional and U.S.-Africa trade, including by supporting African exports to the United States under the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA, Title I, P.L. 106-200, as amended) trade preference program.19 USAID also coordinates Prosper Africa, an emerging Trump Administration trade and investment initiative (see Text Box).

|

The Administration's Prosper Africa Initiative20 Prosper Africa seeks to double U.S.-Africa trade, spur U.S. and African economic growth, and encourage U.S. commercial interest and investment in African markets. As of early 2020, a "deal team" within each U.S. embassy in Africa had been established to help link U.S. firms to trade and investment opportunities in Africa, enable African firms to access similar opportunities in the United States, and facilitate private sector access to U.S. trade assistance, financing, and insurance services. USAID's sub-regional trade and investment hubs are expected to support the initiative through trade capacity-building and related activities. Prosper Africa seeks to marshal the resources and capabilities of various U.S. trade promotion agencies, such as the Export-Import (Ex-Im) Bank, the Trade and Development Agency (TDA), the Small Business Administration (SBA), and the new U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC, established in the BUILD Act, Division F of P.L. 115-254).21 Prosper Africa is at an early stage of implementation, and its impact on U.S.-Africa trade remains to be seen. In addition, the extent to which Prosper Africa differs from past U.S. trade assistance efforts focused on Africa may be debated. Trade capacity-building has been an enduring focus of USAID's trade and investment hubs, which have long supported efforts to expand African exports. The Obama Administration's Trade Africa initiative, which the Trump Administration discontinued, was a trade hub-led effort to bolster intra-regional trade and integration, with an initial focus on East Africa. The Obama Administration also launched Doing Business in Africa (DBIA), an effort to increase U.S. business exposure to African markets and U.S. trade promotion programs. DBIA is now defunct apart from the DBIA President's Advisory Council, a board of private sector actors that offers advice on strengthening U.S.-Africa commercial ties. The Administration has portrayed Prosper Africa as a "one-stop shop" to connect U.S. and African entrepreneurs with the broad range of U.S. trade and investment support programs.22 |

Electrification is another focus of U.S. economic assistance in Africa. Power Africa, a USAID-led initiative that the Obama Administration launched in 2013, seeks to enhance electricity access through technical assistance, grants, financial risk mitigation tools, loans, and other resources—accompanied by trade promotion and diplomatic and advisory efforts. Facilitating private sector contracts is a key focus of the initiative, which aims to build power generation facilities capable of producing 30,000 megawatts of new power and establish 60 million new power connections by 2030.23 A sub-initiative, Beyond the Grid, supports off-grid electricity access. Power Africa involves a range of U.S. federal entities in addition to USAID, including the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), DFC, Ex-Im Bank, TDA, and Departments of State, Energy, Commerce, and Agriculture. The Electrify Africa Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-121) made it U.S. policy to aid electrification in Africa through an approach similar to that of Power Africa.

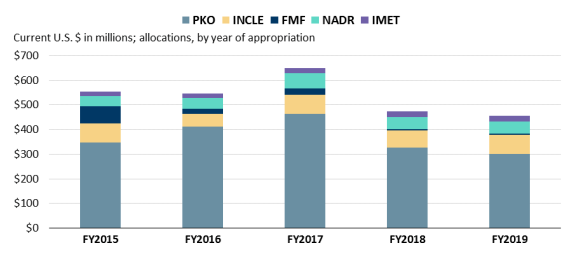

Peace and Security. The State Department administers a range of programs to build the capacity of African militaries and law enforcement agencies to counter security threats, participate in international peacekeeping and stabilization operations, and combat transnational crime (e.g., human and drug trafficking). State Department security assistance authorities are codified in Title 22 of the U.S. Code. Congress appropriates funds for Title 22 programs in annual Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriations, though the Department of Defense (DOD) implements several of these programs. (For information on DOD security cooperation, see "Assistance Administered by Other U.S. Federal Departments and Agencies.")

The Peacekeeping Operations (PKO) account is the primary vehicle for State Department-administered security assistance to African countries (Figure 5). Despite its name, PKO supports not only peacekeeping capacity-building, but also counterterrorism, maritime security, and security sector reform. (A separate State Department-administered account, Contributions to International Peacekeeping Activities [CIPA], funds U.S. assessed contributions to U.N. peacekeeping budgets.) In recent years, the largest PKO allocation for Africa has been for the U.N. Support Office in Somalia (UNSOS), which supports an African Union stabilization operation in that country.24 PKO funding also supports two interagency counterterrorism programs in Africa: the Trans-Sahara Counter-Terrorism Partnership (TSCTP, in North-West Africa), and the Partnership for Regional East Africa Counterterrorism (PREACT, in East Africa).

The Nonproliferation, Anti-terrorism, Demining, and Related Programs (NADR) account funds counterterrorism training and other capacity-building programs for internal security forces, as well as other activities such as landmine removal. International Narcotics Control and Law Enforcement (INCLE) funds support efforts to combat transnational crime and strengthen the rule of law, including through judicial reform and law enforcement capacity-building. The International Military Education and Training (IMET) program offers training for foreign military personnel at facilities in the United States and abroad, and seeks to build military-to-military relationships, introduce participants to the U.S. judicial system, promote respect for human rights, and strengthen civilian control of the military. The United States provides grants to help countries purchase defense articles and services through the Foreign Military Financing (FMF) account.

USAID also implements programs focused on conflict prevention, mitigation, and resolution. Such assistance seeks to prevent mass atrocities, support post-conflict transitions and peace building, and counter violent extremism, among other objectives. Congress appropriates funding for such programs as economic assistance, as opposed to security assistance.

Democracy, Human Rights, and Governance (DRG). State Department- and USAID-administered DRG programs seek to enhance democratic institutions, improve government accountability and responsiveness, and strengthen the rule of law. Activities include supporting African electoral institutions and political processes; training political parties, civil society organizations, parliaments, and journalists; promoting effective and accountable governance; bolstering anti-corruption efforts; and strengthening justice sectors. U.S. assistance also provides legal aid to human rights defenders abroad and funds programs to address particular human rights issues and enable human rights monitoring and reporting.

Education and Social Services. U.S. basic, secondary, and higher education programs seek to boost access to quality education, improve learning outcomes, and support youth transitions into the workforce. Some programs specifically target marginalized students, such as girls and students in rural areas or communities affected by conflict or displacement. Youth development activities also include the Young African Leaders Initiative (YALI), which supports young African business, science, and civic leaders through training and mentorship, networking, and exchange-based fellowships.25 USAID supports four YALI Regional Leadership Centers on the continent—in Ghana, Kenya, Senegal, and South Africa—which offer training and professional development programs. Additional U.S. assistance programs enhance access to, and delivery of, other social services, such as improved water and sanitation facilities.

Environment. Environmental assistance programs in Africa focus on biodiversity conservation, climate change mitigation and adaptation, countering wildlife crime, and natural resource management. In recent years, the largest allocation of regional environmental assistance has been for the Central Africa Regional Program for the Environment (CARPE)

These figures do not include funds administered through global accounts or programs, such as humanitarian assistance. They also exclude funds administered by other U.S. federal entities, such as the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) and Department of Defense (DOD), and U.S. contributions to international financial institutions and other multilateral bodies, such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and United Nations (U.N.) agencies.

Policymakers, analysts, and advocates continue to debate the value and appropriate balance of U.S. assistance programs in Africa. Proponents contend that foreign assistance helps African countries address pressing challenges (e.g., development and humanitarian needs) while advancing U.S. national interests, such as by bolstering U.S. economic relations abroad and promoting U.S. influence vis-à-vis that of global competitors such as China and Russia.5 Some also contend that U.S. assistance reflects U.S. values of charity and global leadership.6

Critics have alleged that foreign aid may create market distortions or dependencies, or have other unintended consequences, such as prolonging conflicts or strengthening undemocratic regimes.7 Some African commentators have criticized the nature of donor-recipient relationships, describing them as shaped primarily by donor prerogatives rather than by the needs and demands of recipient countries, or as benefitting international implementers over local authorities and organizations.8 5 Stephen A. O’Connell, “What the U.S. Gains From its Development Aid to Sub-Saharan Africa,” EconoFact, January 31, 2017.

6 For more on the rationales and objectives of U.S. foreign assistance, see CRS Report R40213, Foreign Assistance: An Introduction to U.S. Programs and Policy, by Emily M. Morgenstern and Nick M. Brown.

7 For a critical assessment of foreign assistance in Africa, see, for example, Max Bergmann and Alexandra Schmitt, A Plan to Reform U.S. Security Assistance, Center for American Progress, 2021; and Dambisa Moyo, Dead Aid: Why Aid is Not Working and How There is a Better Way for Africa (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2009).

8 See, e.g., testimony by Degan Ali and Ali Mohamed in House Foreign Affairs Committee, “Shifting the Power: Advancing Locally-Led Development and Partner Diversification in U.S. Development Programs,” hearing, 117th

Congressional Research Service

2

link to page 20 U.S. Assistance for Sub-Saharan Africa: An Overview

More broadly, some Members and others have called for a reorientation of U.S. engagement in Africa to deemphasize U.S. assistance relative to U.S. commercial engagement, calling for “trade, not aid” to promote development in the region.9 Other considerations related to U.S. assistance for Africa and issues for Congress are discussed below (see “Outlook and Issues for Congress”).

Recent Funding Trends, Objectives, and Delivery Since FY2017, health assistance has constituted approximately three-quarters of annual U.S. assistance for Africa; HIV/AIDS-related funding alone typically accounts for around half of all State Department- and USAID-administered assistance for the region in a given fiscal year.10 Agriculture and other economic programs generally have comprised the second-largest focus area of U.S. assistance for Africa, accounting for around 9% of average annual allocations since FY2017, followed by peace and security programs (7%), education and social services funding (4%) and democracy, human rights, and governance (DRG) assistance (4%).11

U.S. assistance for Africa totaled $7.65 billion in FY2021 allocations, including supplemental global health security funds provided in the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA, P.L. 117-2) but excluding emergency assistance appropriated for Sudan under Title IX of P.L. 116-260 as well as humanitarian assistance.12 Broadly consistent with past years, health programs comprised roughly 78% of FY2021 assistance, followed by funds to promote economic growth, advance peace and security, enhance education and other social service delivery, and strengthen democracy, human rights, and governance.

Health Assistance Congress funds U.S. health assistance for Africa primarily through appropriations to the Global Health Programs account, which is administered partly by the State Department (GHP-State) and partly by USAID (GHP-USAID). Health assistance to improve access to water and sanitation, however, is generally funded under the Development Assistance (DA) account.

Cong., 1st Sess., September 23, 2021; U.N. Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator Mark Lowcock, “What’s Wrong with the Humanitarian Aid System and How to Fix It,” remarks at Center for Global Development, April 2021.

9 See, e.g., remarks by Representative Karen Bass in House Foreign Affairs Committee roundtable, “Roundtable: Celebrating African Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Leadership,” May 25, 2021; Adva Saldinger, “Q&A: US Representative Ted Yoho on his foreign aid philosophy,” Devex, February 24, 2017.

10 CRS calculations based on FY2017-FY2021 data provided by USAID, May 2022. In FY2017, the State Department revised the Standardized Program Structure and Definitions (SPSD) framework under which U.S. foreign assistance is categorized by program area and activity, complicating assessments of longer-term sectoral funding trends.

11 CRS calculations based on data provided by USAID, May 2022. Figures reflect averages from FY2017-FY2021. 12 State Department, CBJ for FY2023. Specifically, this includes $367 million in global health security in development (GHSD) assistance provided in ARPA to enable comparison with the Biden Administration’s FY2023 request, which—in a departure from past budget requests—disaggregates most GHSD funding by country. It excludes $700 million in emergency funding for Sudan appropriated in the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 (Title IX of P.L. 116-260).

Congressional Research Service

3

U.S. Assistance for Sub-Saharan Africa: An Overview

Figure 2. Health Assistance for Africa in FY2021, by Program Area and Element

Source: CRS graphic. Figures are CRS calculations based on data from State Department CBJ for FY2023.

HIV/AIDS. Most U.S. health assistance for Africa supports HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment efforts under the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)—a State Department-led, interagency effort that Congress first authorized during the George W. Bush Administration and reauthorized through 2023 in P.L. 115-305.13 GHP-State is the primary vehicle for HIV/AIDS assistance for Africa, though USAID partly manages such funding, and USAID administers some additional HIV/AIDS assistance via GHP-USAID. Nigeria, Tanzania, Mozambique, South Africa, Uganda, and Zambia were the top recipients of HIV/AIDS assistance allocations in FY2021.

Malaria. Programs to prevent and treat malaria typically constitute the second-largest category of U.S. health assistance for the region.14 Such funding is largely provided through the USAID-led President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI), which focused on 24 African “focus countries” (out of 27 worldwide) as of July 2022. Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which together account for roughly 40% of annual malaria cases globally, regularly rank as the leading recipients of U.S. counter-malaria assistance in Africa.15

Maternal and Child Health, Family Planning, and Reproductive Health. African countries have made strides in maternal and child health in recent decades, yet stark challenges persist; as a region, Africa accounts for an estimated two-thirds of global maternal deaths and has the world’s highest neonatal and under-five mortality rates.16 U.S. maternal and child health programs aim to improve maternal, newborn, and early childhood care. Family planning and reproductive health

13 See CRS In Focus IF11018, Global Trends in HIV/AIDS, by Sara M. Tharakan, and CRS In Focus IF10797, PEPFAR Stewardship and Oversight Act: Expiring Authorities, by Tiaji Salaam-Blyther.

14 See CRS In Focus IF11146, Global Trends: Malaria, by Sara M. Tharakan. 15 Malaria burden figures from World Health Organization (WHO), World Malaria Report 2021, 2021. 16 WHO, U.N. Children’s Fund, U.N. Population Fund, World Bank, and U.N. Population Division, Trends in Maternal Mortality, 2000 to 2017, 2019; U.N. Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation, Levels & Trends in Child Mortality: Report 2021, 2021.

Congressional Research Service

4

link to page 14 U.S. Assistance for Sub-Saharan Africa: An Overview

programs, meanwhile, support access to contraception, along with efforts to end child marriage, female genital mutilation/cutting, gender-based violence, and other reproductive health issues.17

Global Health Security. U.S. health assistance for Africa includes some funding for pandemic preparedness and response activities, though most such assistance is channeled through global accounts and programs or administered by other U.S. agencies, such as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, it also has included aid to help African countries counter the disease and its effects (see Text Box).

COVID-19-Related Assistance for Africa

As of March 31, 2022 (latest data available), USAID-administered support for COVID-19 responses in Africa totaled over $1.8 bil ion, most of which was special y appropriated by Congress and represents an addition to regular annual foreign aid appropriations.18 USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (BHA) administered a majority ($1.3 bil ion) of such funding, with smaller amounts managed by the Bureau for Africa ($353 mil ion) and Bureau for Global Health ($231 mil ion). Ethiopia has been the largest recipient of U.S. COVID-19-related assistance in Africa by, with at least $366 mil ion in U.S. obligations as of March 2022, fol owed by South Sudan ($182 mil ion), Sudan ($163 mil ion), and Nigeria ($104 mil ion).

Other Assistance. Other U.S. health assistance for Africa, most administered by USAID, seeks to enhance access to improved water and sanitation facilities, improve nutrition, and combat tuberculosis. As discussed below (see “Selected Global Assistance for Africa”), the United States provides additional health funding for Africa through global programs as well as through contributions to multilateral health initiatives such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria (the Global Fund).

Economic Growth Assistance As noted above, economic growth programs typically comprise the second-largest focus area of U.S. assistance for Africa. Congress funds such assistance primarily through the DA account, though some programs are funded via the Economic Support Fund (ESF).19

17 See CRS Report R46215, U.S. Bilateral International Family Planning and Reproductive Health Programs: Background and Selected Issues. On differences between maternal and child health programs and family planning and reproductive health programs, see State Department, “Updated Foreign Assistance Standardized Program Structure and Definitions,” April 19, 2016.

18 Figures in this text box refer to obligated funds provided in the 2020 Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act (P.L. 116-123), the 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act (P.L. 116-136), the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act (P.L. 117-2), and prior year funding. Figures do not include USAID support for GAVI COVAX, the multilateral vaccine initiative. USAID, “COVID-19 – Sub-Saharan Africa (Fact Sheet #4, FY2022),” March 31, 2022. 19 The State Department and USAID jointly administer ESF funding; USAID manages DA.

Congressional Research Service

5

U.S. Assistance for Sub-Saharan Africa: An Overview

Figure 3. Economic Growth Assistance for Africa in FY2021, by Program Area and

Element

Source: CRS graphic. Figures are CRS calculations based on data from State Department CBJ for FY2023.

Agricultural Development. Support for agricultural development typically constitutes the largest category of U.S. economic growth assistance for Africa. Such programs seek to improve agricultural productivity by strengthening value chains, enhancing land tenure systems and access to markets, promoting climate-resilient farming practices, and funding agricultural research. Feed the Future (FTF), a USAID-led, interagency initiative launched by the Obama Administration to reduce food insecurity and enhance market-based economic growth, is the main channel for U.S. agricultural assistance for Africa; as of July 2022, there were eight African FTF focus countries, out of 12 globally.20 The Global Food Security Act of 2016 (P.L. 114-195, reauthorized through 2023 in P.L. 115-266) endorsed an approach to U.S. food security assistance similar to FTF.

Trade and Investment. Prosper Africa, a USAID-led, multiagency initiative launched by the Trump Administration in 2019, is the primary vehicle for U.S. trade and investment assistance for Africa. It aims to spur U.S. and African market-led economic growth by substantially increasing two-way U.S.-African trade and investment ties, foster business environment reforms in Africa, and counter the economic influence of China and other U.S. global competitors.21

A range of U.S. assistance programs support trade capacity-building (TCB) efforts that aim to boost African countries’ ability to trade with other countries and with the United States—the latter notably under the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA, P.L. 106-200, as amended),

20 African FTF focus countries are Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, and Uganda. FTF supports other countries under “aligned” and regional programs

21 Prosper Africa primarily seeks to harmonize and provide a single point of access to the services and programs of 17 U.S. agencies and departments with trade and investment promotion and economic development mandates. See CRS In Focus IF11384, The Trump Administration’s Prosper Africa Initiative, by Nicolas Cook and Brock R. Williams.

Congressional Research Service

6

link to page 17 U.S. Assistance for Sub-Saharan Africa: An Overview

which provides duty-free treatment for U.S. imports from eligible African countries.22 Over the last two decades, much of this activity has been channeled through two (formerly three) USAID-administered sub-regional trade and investment hubs, located in West and Southern Africa.

Climate Change and Environment. The State Department classifies a range of U.S. assistance to mitigate and address the impacts of climate change under the umbrella of economic growth assistance, though not all of this assistance is directly related to economic growth.23 Under the Obama Administration, the United States sharply increased such funding, including for Africa; the Trump Administration took steps to largely end such assistance globally.

The Biden Administration has placed a high priority on responding to climate change globally and, as discussed below, has sought to increase climate change-related assistance for Africa (see “The Biden Administration and the FY2023 Request”). During the Biden Administration, the largest allocation of climate change-related assistance has been for Power Africa, a USAID-led electrification effort launched by the Obama Administration that provides technical assistance and advice, grants, loans, financial risk mitigation, and other assistance to support increased access to power, including renewable energy.24 Facilitating individual power projects is a core focus of the initiative, which aims to create 30,000 megawatts of new power generation capacity and establish 60 million new connections in Africa by 2030.25 Expanding energy access in the region is a standing U.S. policy goal under the Electrify Africa Act of 2015 (P.L. 114-121).

U.S. economic growth assistance also funds “environment” programs, activities related to natural resources that are not directly focused on climate change (e.g., conservation and countering wildlife crime). Funding for the Central Africa Regional Program for the Environment (CARPE) is typically the largest allocation of annual environment assistance. Implemented by USAID and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (per congressional directives), CARPE, CAPRE promotes conservation, and sustainable resource use, and climate change mitigation in Central Africa's Congo Basin rainforest, with a present focus on landscapes in DRC, the Republic of Congo, and the Central African Republic (CAR).26 Congress has shown enduring interest in international conservation initiatives and efforts to curb wildlife trafficking and other environmental crime, including in Africa.27

Select Assistance Provided through Global Accounts and Programs

As noted, the discussion above does not account for U.S. development, security, or health assistance allocated to African countries via global accounts and programs—funds that are not broken out by region or country in public budget documents. This includes situation-responsive assistance, such as emergency humanitarian aid and certain kinds of governance support, which is appropriated on a global basis and allocated in response to emerging needs or opportunities. Notably, it also includes certain security assistance programs through which some African countries have received considerable funding in recent years. Gaps in region- and country-level aid data may raise challenges for congressional oversight (see "Select Issues for Congress").

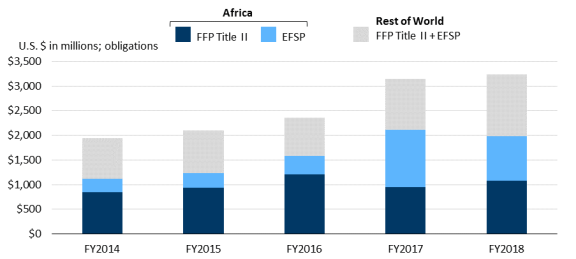

Emergency Assistance. As of early 2020, there were U.S.- or U.N.-designated humanitarian crises in Burkina Faso, CAR, DRC, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, and the Lake Chad Basin (including parts of Cameroon, Chad, Niger, and Nigeria). The United States administers humanitarian aid to Africa under various authorities. Key accounts and programs include:

- USAID-administered Food for Peace (FFP) assistance authorized under Title II of the Food for Peace Act of 1954 (P.L. 83-480, commonly known as "P.L. 480"), which primarily provides for the purchase and distribution of U.S. in-kind food commodities.28 African countries consistently have received a majority of annual FFP Title II emergency assistance in recent years.

USAID-administered International Disaster Assistance (IDA), which funds food and nonfood humanitarian assistance—including the Emergency Food Security Program (EFSP), which funds market-based food assistance, including cash transfers, food vouchers, and food procured locally and regionally.29

State Department-administered Migration and Refugees Assistance (MRA) assistance for refugees and vulnerable migrants.

|

|

|

Source: USAID, Emergency Food Security Program Report and International Food Assistance Report, FY2014-FY2018. |

Assistance Administered by Other U.S. Federal Departments and Agencies

While the State Department and USAID administer the majority of U.S. foreign assistance to Africa, other federal departments and agencies also manage or support aid programs in the region. For example, the Departments of Agriculture, Energy, Justice, Commerce, Homeland Security, and the Treasury conduct technical assistance programs and other activities in Africa, and may help implement some State Department- and USAID-administered programs on the continent.

Other U.S. federal entities involved in administering assistance to Africa notably include:

The Department of Defense (DOD). In addition to implementing some State Department-administered security assistance programs, DOD is authorized to engage in security cooperation with foreign partner militaries and internal security entities for a range of purposes.30 The majority of this assistance has been provided under DOD's "global train and equip" authority, first established by Congress in the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) of FY2006 (P.L. 109-163). In the FY2017 NDAA (P.L. 114-328), Congress codified and expanded the "global train and equip" authority under 10 U.S.C. 333 ("Section 333"), consolidating various capacity-building authorities that it had granted DOD on a temporary or otherwise limited basis. Section 333 authorizes DOD to provide training and equipment to foreign military and internal security forces to build their capacity to counter terrorism, weapons of mass destruction, drug trafficking, and transnational crime, and to bolster maritime and border security and military intelligence.

Comprehensive regional- or country-level funding data for DOD security cooperation programs are not publicly available, complicating approximations of funding for African countries. A CRS calculation based on available congressional notification data suggests that Kenya, Uganda, Niger, Chad, Somalia, and Cameroon have been the top African recipients of cumulative DOD global train and equip assistance over the past decade.31 Congress has authorized additional DOD security cooperation programs in Africa under global or Africa-specific authorities (e.g., to help combat the Lord's Resistance Army rebel group in Central Africa between FY2012 and FY2017).

Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC).32 Authorized by Congress in 2004, the MCC supports five-year development "compacts" in developing countries that meet various governance and development benchmarks. MCC recipient governments lead the development and implementation of their programs, which are tailored to address key "constraints to growth" identified during the compact design phase. The MCC also funds smaller, shorter-term "threshold programs" that assist promising candidate countries to become compact-eligible.

As shown in Appendix B, the MCC has supported 32 compacts or threshold programs in 22 African countries since its inception, valued at roughly $8.0 billion in committed funding. There are seven ongoing compacts and threshold programs in the region. The MCC has suspended or terminated compacts with some African governments for failing to maintain performance against selection benchmarks: it terminated engagement in Madagascar and Mali due to military coups, and suspended development of a second compact for Tanzania in 2016 due to a government crackdown on the political opposition.33 In late 2019, the MCC cancelled a $190 million tranche of funding under Ghana's second compact over concerns with the Ghanaian government's termination of a contract with a private energy utility.34

The Peace Corps.35 The Peace Corps supports American volunteers to live in local communities abroad and conduct grassroots-level assistance programs focused on agriculture, economic development, youth engagement, health, and education. As of September 2019, 45% of Peace Corps Volunteers were serving in sub-Saharan Africa—by far the largest share by region.36 Conflict and other crises in Africa have episodically led the Peace Corps to suspend programming over concern for volunteer safety, with recent conflict-related suspensions in Mali (in 2015) and Burkina Faso (2017) and temporary suspensions in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone during the 2014-2016 West Africa Ebola outbreak. In 2019, the Peace Corps announced that it would resume operations in Kenya after suspending activities in 2014 due to security concerns. The Peace Corps ceased all activities and recalled all volunteers worldwide in March 2020 due to COVID-19.

African Development Foundation (USADF). A federally funded, independent nonprofit corporation created by Congress in the African Development Foundation Act of 1980 (Title V of P.L. 96-533), the USADF seeks to reduce poverty by providing targeted grants worth up to $250,000 that typically serve as seed capital for small-scale economic growth projects. The USADF maintains a core focus on agriculture, micro-enterprise development, and community resilience. It prioritizes support for marginalized, poor, and often remote communities as well as selected social groups, such as women and youth—often in fragile or post-conflict countries. USADF also plays a role in selected multi-agency initiatives, such as Power Africa and YALI.

U.S. Aid to Africa During the Trump Administration

In 2018, the Trump Administration identified three core goals of its policy approach toward Africa: expanding U.S. trade and commercial ties, countering armed Islamist violence and other forms of conflict, and imposing more stringent conditions on U.S. assistance and U.N. peacekeeping missions in the region.37 The Administration also has emphasized efforts to counter "great power competitors" in Africa, namely China and Russia, which it has accused of challenging U.S. influence in the region through "predatory" economic practices and other means.38 Other stated policy objectives include promoting youth development and strengthening investment climates on the continent.39 Budget requests and other official documents, such as USAID country strategies, have asserted other priorities broadly similar to those pursued by past Administrations, such as boosting economic growth, investment, and trade, enhancing democracy and good governance, promoting socioeconomic development, and improving health outcomes.40

The Administration has expressed skepticism of U.S. foreign aid globally, and to certain African countries in particular. For instance, then-National Security Advisor John Bolton pledged in 2018 to curtail aid to African countries whose governments are corrupt and to direct assistance toward states that govern democratically, pursue transparent business practices, and "act as responsible regional stakeholders [...and] where state failure or weakness would pose a direct threat to the United States and our citizens."41 These objectives do not appear to have been revoked since Bolton's departure from the White House in September 2019. Whether the Administration's budget proposals for aid to Africa have reflected such pledges is debatable, however, as discussed below ("The FY2021 Assistance Request for Africa: Overview and Analysis").

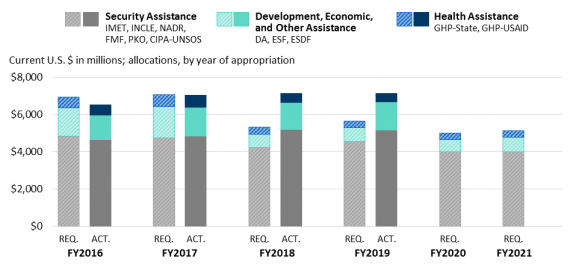

The Trump Administration has maintained several assistance initiatives focused substantially or exclusively on Africa—including PEPFAR, the PMI, Feed the Future, Power Africa, and YALI, among others—and, as noted above, has launched Prosper Africa, a new Africa-focused trade and investment initiative. At the same time, the Administration has proposed to sharply reduce U.S. assistance to Africa (and globally), even as Congress has provided assistance for Africa at roughly constant levels in recent fiscal years (see Figure 7). The Trump Administration also has proposed changes to the manner in which the United States delivers assistance which, if enacted, could have implications for U.S. aid to Africa. These include:

Changes to humanitarian assistance. As part of a consolidation of humanitarian aid accounts, the Administration has repeatedly proposed to eliminate FFP Title II aid, through which African countries received $1.2 billion in emergency food assistance in FY2019.42 The FY2021 budget request would merge the four humanitarian accounts—FFP Title II, International Disaster Assistance (IDA), Migration and Refugee Assistance (MRA), and Emergency Refugee and Migration Assistance (ERMA)—into a single International Humanitarian Assistance (IHA) account. Budget documents assert that the consolidation would enhance the flexibility and efficiency of humanitarian assistance.43

Changes to bilateral economic assistance. The Administration has repeatedly proposed to merge a number of bilateral economic assistance accounts—including Development Assistance (DA) and Economic Support Fund (ESF) aid, through which African countries received a cumulative $1.5 billion in FY2019—into a new Economic Support and Development Fund (ESDF) account. The Administration has consistently requested far less in ESDF than prior-year combined allocations for the subsumed accounts. Budget documents contend the consolidation would improve efficiency.44

Cutting Foreign Military Financing for Africa. Unlike previous Administrations, the Trump Administration has not requested FMF for African countries, with the exception of Djibouti, which hosts the only enduring U.S. military installation in Africa.45

Eliminating the USADF. The Administration annually has proposed to eliminate the USADF and create a grants office within USAID that would assume responsibility for the agency's work. In successive budget requests, the Administration has included one-time closeout funding for the agency (e.g., $4.7 million for FY2021).

To date, Congress has maintained the existing account structures for the delivery of humanitarian aid and economic assistance and continued to appropriate operating funds to the USADF—most recently under P.L. 116-94 at a level of $33 million for FY2020. Consideration of the President's FY2021 budget request, released in February 2020, is underway.

The FY2021 Assistance Request for Africa

Overview. The Administration's FY2021 budget request includes $5.2 billion in aid for Africa, an increase from its FY2020 request ($5.0 billion) but 28% below FY2019 allocations ($7.1 billion).46 These totals do not include emergency humanitarian aid or funding allocated to African countries from global accounts and programs. Funding for Africa would fall sharply from FY2019 levels across most major funding accounts, including Global Health Programs (which would see a 22% drop), PKO (23%), INCLE (46%), and IMET (16%).47 Non-health development assistance would see the largest decline from FY2019 levels: the request would provide $797 million in ESDF for Africa, down 48% from $1.5 billion in allocated ESF and DA in FY2019. The request includes $75 million in ESDF for Prosper Africa, up from $50 million requested in FY2020. Separate proposed decreases in U.S. funding for U.N. peacekeeping missions, most of which are in Africa, could have implications for stability and humanitarian operations.48

Analysis. Overwhelmingly weighted toward health assistance, with the balance largely dedicated to traditional development and security activities, the FY2021 request aligns with long-standing U.S. priorities in the region—while at the same time proposing significant cuts to U.S. assistance across all major sectors. Congress has not enacted similar proposed reductions in previous appropriations measures; several Members specifically have raised concerns over the potential ramifications of such cuts for U.S. influence and partnerships abroad.49 In this regard, it may be debated whether the FY2021 budget, if enacted, would be likely to advance the Administration's stated priority of countering the influence of geostrategic competitors in Africa. For instance, officials have described Prosper Africa as partly intended to counter China's growing influence in the region, yet $75 million in proposed funding for the initiative is arguably incommensurate with the Administration's goal of "vastly accelerat[ing]" two way U.S-Africa trade and investment.50

Despite the Administration's pledge to curtail aid to countries that fail to govern democratically and transparently, top proposed recipients in FY2021 include several countries with poor or deteriorating governance records (e.g., Uganda, Rwanda, Nigeria, and Tanzania). Sharp proposed cuts to bilateral economic assistance, through which the United States funds most DRG activities, could have implications for U.S. democracy and governance programming in the region.

Select Issues for Congress

Below is a selected list of issues that Congress may consider as it weights budgetary proposals and authorizes, appropriates funding for, and oversees U.S. foreign aid programs in Africa. References to specific countries are provided solely as illustrative examples.

Scale and balance. Members may debate whether U.S. assistance to Africa is adequately balanced between sectors given the broad scope of Africa's needs and U.S. priorities on the continent, and whether overall funding levels are commensurate with U.S. interests in the region. Successive Administrations have articulated a diverse range of development, governance, and security objectives in Africa—yet U.S. assistance to the region has remained dominated by funding for health programs since the mid-2000s. Some Members of Congress have expressed concern over the relatively small share of U.S. aid dedicated to other stated U.S. priorities, such as promoting good governance, expanding U.S.-Africa commercial ties, and mitigating conflict.51

Meanwhile, the Trump Administration's repeated proposals to sharply reduce U.S. assistance to Africa have spurred pushback from some Members. Congressional objections have centered on the risks that aid cuts could potentially pose for U.S. national security, foreign policy goals, and U.S. influence and partnerships in Africa.52 Notably, the proposed cuts in U.S. assistance come at a time when China and other countries, including Russia, India, Turkey, and several Arab Gulf states, are seeking to expand their roles in the region.53

Transparency and oversight. While this report provides approximate funding figures based largely on publicly available allocation data, comprehensive estimates of U.S. aid to Africa and amounts dedicated to specific focus areas are difficult to determine. Executive branch budget documents and congressional appropriations measures do not fully disaggregate aid allocations by country or region; meanwhile, databases such as USAID's Foreign Aid Explorer and the State Department's ForeignAssistance.gov provide data on obligations and disbursements but do not track committed funding against enacted levels, raising challenges for congressional oversight.

As noted above, gaps in region- and country-level assistance data may partly reflect efforts to maintain flexibility in U.S. assistance programs—for instance, by appropriating humanitarian aid to global accounts and allocating it according to need. At the same time, Congress has not imposed rigorous reporting requirements evenly across U.S. foreign aid programs. For instance, while DOD "global train and equip" assistance is subject to congressional notification and reporting requirements that require detailed information about country and security force unit recipients and assistance to be provided, there is no analogous reporting requirement governing State Department security assistance.54 Public budget documents may thus include country- and program-level breakouts of some security assistance, while other funds—such as for the Global Peace Operations Initiative (GPOI), a PKO-funded peacekeeping capacity-building program through which some African militaries have received substantial U.S. training and equipment—are not reflected in bilateral aid budgets. A lack of data on what U.S. assistance has been provided to African countries may obscure policy dilemmas or inhibit efforts to evaluate impact.55

Country Ownership. Policymakers may debate the extent to which U.S. assistance supports partner African governments in taking the lead in addressing challenges related to socioeconomic development, security, and governance. The majority of U.S. aid to Africa is provided through nongovernment actors—such as U.N. agencies, humanitarian organizations, development practitioners, and civil society entities—rather than directly to governments. (Exceptions include U.S. security assistance for African security forces and some healthcare capacity-building programs.) Channeling aid through nongovernment actors may be preferable in countries where the state is unable or unwilling to meet the needs of its population, and may additionally grant the United States greater control and oversight over the use of aid funds. At the same time, experts debate whether this method of assistance adequately equips recipient governments to take primary responsibility for service delivery and other state duties—as well as whether this mode of delivery may limit donor influence and leverage with the recipient country government.56

Conditions on U.S. assistance. Congress has enacted legislation denying or placing conditions on assistance to countries that fail to meet certain standards in, for instance, human rights, counterterrorism, debt repayment, religious freedom, child soldier use, or trafficking in persons. In general, statutes establishing such conditions accord the executive branch the discretion to designate countries for sanction or waive such restrictions. Congress may continue to debate the merits and effectiveness of such restrictions. In FY2020, several African governments are subject to aid restrictions due to failure to meet standards related to:

- Religious freedom, under the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998 (P.L. 105-292), with Eritrea currently listed as a "Country of Particular Concern."57

- The use of child soldiers, under the Child Soldiers Prevention Act (CSPA, P.L. 110-457, as amended) and related legislation, with DRC, Mali, Somalia, South Sudan, and Sudan subject to potential security assistance restrictions in FY2020.58 In October 2019, President Trump exercised his authority under CSPA to waive certain restrictions for DRC, Mali, Somalia, and South Sudan.59

- Trafficking in persons (TIP), under the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA, P.L. 106-386, as amended) and related legislation, with Burundi, Comoros, DRC, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, The Gambia, Mauritania, and South Sudan subject to potential aid restrictions in FY2020. In October 2019, President Trump partially waived such restrictions with regard to DRC and South Sudan, and fully waived them for Comoros.60

Some African countries periodically have been subject to other restrictions on U.S. foreign aid, such as those imposed on governments that rose to power through a coup d'état, support international terrorism, or are in external debt arrears. (In contrast to most legislative aid restrictions, a provision in annual appropriations legislation prohibiting most aid to governments that accede to power through a military coup does not grant the executive branch authority to waive the restrictions.61) Congress has also included provisions in annual aid appropriations measures restricting certain aid to specific African countries, notably Sudan and Zimbabwe.

In addition, the so-called "Leahy Laws" restrict most kinds of State Department- and DOD-administered security assistance to individual units or members of foreign security forces credibly implicated in a "gross violation of human rights," subject to certain exceptions.62 The executive branch does not publish information on which units or individual personnel have been prohibited from receiving U.S. assistance pursuant to these laws. Congress also has restricted certain kinds of security assistance deemed likely to be used for unintended purposes; for instance, language in annual foreign aid appropriations measures prohibits the use of funds for providing tear gas and other crowd control items to security forces that curtail freedoms of expression and assembly.

Unintended consequences. Some observers have raised concerns that the provision of U.S. foreign assistance may have unintended consequences, including in Africa. For instance, some analysts have questioned whether U.S. food assistance may inadvertently prolong civil conflict by enabling warring parties to sustain operations, though others have challenged that assertion.63 Whether providing certain forms of U.S. aid, notably security assistance, may at times jeopardize U.S. policy goals in other areas is another potential consideration. For instance, some analysts have questioned whether security assistance to African governments with poor human rights records (e.g., Chad, Cameroon, Nigeria, and Uganda) may strengthen abusive security forces or inhibit U.S. leverage on issues related to democracy and governance.64 Proponents of U.S. security assistance programs in Africa may contend that aspects of such engagements—such as military professionalization and human rights training—enhance security sector governance and civil-military relations, and may thus improve human rights practices by partner militaries.

Outlook

Congress commenced consideration of the President's FY2021 budget request in February 2020. To date, the 116th Congress has not adopted many of the Administration's proposed changes regarding assistance to Africa, notably its repeated attempts to significantly reduce aid to the region. Allocated funding has instead hovered around $7 billion per year, excluding emergency humanitarian aid. As Congress debates the FY2021 Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs appropriations measure, Members may consider issues such as:

- The economic, humanitarian, and health-related shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is expected to have a severe impact on Africa's development trajectory;

Unfolding political transitions in Sudan and Ethiopia, which may have significant implications for governance and conflict trends in the region;65

Conflicts and humanitarian crises in Burkina Faso, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Mali, Nigeria, Somalia, and South Sudan;66

Repressive governance in several countries that rank as top recipients of U.S. assistance in Africa, including Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia;67

The effectiveness of existing conditions on U.S. foreign assistance to Africa, whether additional conditions and restrictions may be necessary, and the appropriate balance between ensuring congressional influence and providing executive branch flexibility;

U.S.-Africa trade and investment issues, including as they relate to funding and overseeing the Administration's Prosper Africa initiative; and

The involvement in Africa of foreign powers such as China and Russia, and the implications of such engagement for U.S. national security and policy interests.

Appendix A.

U.S. Assistance to Africa, by Country

Allocations by year of appropriation, selected accounts, in thousands of current U.S. dollars

|

Country / Account |

FY2017 |

FY2018 |

FY2019 |

FY2020 req. |

FY2021 req. |

|

Angola |

43,942 |

42,023 |

33,619 |

24,400 |

36,400 |

|

GHP-State |

11,058 |

9,028 |

4,932 |

0 |

10,000 |

|

GHP-USAID |

28,390 |

28,390 |

24,000 |

22,000 |

22,000 |

|

IMET |

494 |

605 |

587 |

400 |

400 |

|

NADR |

4,000 |

4,000 |

4,100 |

2,000 |

4,000 |

|

Benin |

23,590 |

24,512 |

25,550 |

19,300 |

19,300 |

|

GHP-USAID |

23,000 |