Novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19): Q&A on Global Implications and Responses

In December 2019, hospitals in the city of Wuhan in China’s Hubei Province began seeing cases of pneumonia of unknown origin. Chinese health authorities ultimately connected the condition, later named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), to a previously unidentified strain of coronavirus. The disease has spread to almost every country in the world, including the United States. WHO declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 30, 2020; raised its global risk assessment to “Very High” on February 28; and labeled the outbreak a “pandemic” on March 11. In using the term pandemic, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus cited COVID-19’s “alarming levels of spread and severity” and governments’ “alarming levels of inaction.” As of May 14, 2020, WHO had reported more than 4.2 million COVID-19 cases, including almost 300,000 deaths, of which more than 40% of all cases and 55% of all deaths were identified in Europe, and more than 30% of all cases and nearly 30% of all deaths were identified in the United States. Members of Congress have demonstrated strong interest in ending the pandemic domestically and globally. To date, Members have introduced dozens of pieces of legislation on international aspects of the pandemic (see the Appendix).

Individual countries are carrying out not only domestic but also international efforts to control the COVID-19 pandemic, with the WHO issuing guidance, coordinating some international research and related findings, and coordinating health aid in low-resource settings. Countries are following (to varying degrees) WHO policy guidance on COVID-19 response and are leveraging information shared by WHO to refine national COVID-19 plans. The United Nations (U.N.) Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) is requesting almost $7 billion to support COVID-19 efforts by several U.N. entities. International financial institutions (IFIs), including the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and the regional development banks, are mobilizing their financial resources to support countries grappling with the COVID-19 pandemic. The IMF has announced it is ready to tap its total lending capacity, about $1 trillion, to support governments responding to COVID-19. The World Bank can mobilize about $150 billion over the next 15 months, and the regional development banks are also preparing new programs and redirecting existing programs to help countries respond to the economic ramifications of COVID-19.

On January 29, 2020, President Donald Trump announced the formation of the President’s Coronavirus Task Force, led by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and coordinated by the White House National Security Council (NSC). On February 27, the President appointed Vice President Michael Pence as the Administration’s COVID-19 task force leader, and the Vice President subsequently appointed the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) Ambassador Deborah Birx as the “White House Coronavirus Response Coordinator.” On March 6, 2020, the President signed into law the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2020, P.L. 116-123, which provides $8.3 billion for domestic and international COVID-19 response. The Act includes $300 million to continue the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) global health security programs and a total of $1.25 billion for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and Department of State. Of those funds, $985 million is designated for foreign assistance accounts, including $435 million specifically for Global Health Programs. On March 27, 2020, President Trump signed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act), P.L. 116-136, which contains emergency funding for U.S. international COVID-19 responses, including $258 million to USAID through the International Disaster Assistance (IDA) account and $350 million to the State Department through the Migration and Refugee Assistance (MRA) account (P.L. 116-127).

The pandemic presents major consequences for foreign aid, global health, diplomatic relations, the global economy, and global security. Regarding foreign aid, Congress may wish to consider how the pandemic might reshape pre-existing U.S. aid priorities—and how it may affect the ability of U.S. personnel to implement and oversee programs in the field. The pandemic is also raising questions about deportation and sanction policies, particularly regarding Latin America and the Caribbean and Iran. In the 116th Congress, Members have introduced legislation to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic in particular and to address global pandemic preparedness in general. This report focuses on global implications of and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, and is organized into four broad parts that answer common questions regarding: (1) the disease and its global prevalence, (2) country and regional responses, (3) global economic and trade implications, and (4) issues that Congress might consider. For information on domestic COVID-19 cases and related responses, see CRS Insight IN11253, Domestic Public Health Response to COVID-19: Current Status and Resources Guide, by Kavya Sekar and Ada S. Cornell.

Novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19): Q&A on Global Implications and Responses

Jump to Main Text of Report

Contents

- Introduction

- What are coronaviruses and what is COVID-19?

- How is COVID-19 transmitted?

- What are global COVID-19 case fatality and hospitalization rates?

- Where are COVID-19 cases concentrated?

- COVID-19 Responses of International Institutions

- International Health Regulations

- What rules guide COVID-19 responses worldwide?

- How does WHO respond to countries that do not comply with IHR (2005)?

- How does the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) relate to IHR (2005) and pandemic preparedness?

- Multilateral Technical Assistance

- What is WHO doing to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic?

- How are international financial institutions responding to COVID-19?

- What is the U.N. humanitarian response to the COVID-19 pandemic?

- U.S. Support for International Responses

- Emergency Appropriations for International Responses

- U.S. Department of State

- How does the State Department help American citizens abroad?

- What are the authorities and funding for the State Department to carry out overseas evacuations?

- How many evacuations have been carried out due to the COVID-19 pandemic?

- U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)

- Where is USAID providing COVID-19 assistance?

- What type of assistance does USAID provide for COVID-19 control?

- How do USAID COVID-19 responses relate to regular pandemic preparedness activities?

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- What role is CDC playing in international COVID-19 responses?

- How do CDC COVID-19 responses relate to regular pandemic preparedness activities?

- U.S. Department of Defense (DOD)

- What is the DOD global COVID-19 response?

- Emergency Appropriations for DOD Responses

- To what extent is COVID-19 affecting United States security personnel?

- Regional Implications of and Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Asia

- What are the implications for U.S.-China relations?

- What are the implications in Southeast Asia?

- What are the implications in Central Asia?

- What are the implications in South Asia?

- What are the implications in Australia and New Zealand?

- What are the implications for U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan?

- What COVID-19 containment lessons could be learned from Asia?

- Europe

- How are European governments and the European Union (EU) responding?

- How is the pandemic affecting U.S.-European relations?

- Africa

- How are African governments responding?

- How is the Africa CDC responding?

- Middle East and North Africa

- How are Middle Eastern and North African governments responding?

- What are the implications for U.S.-Iran policy?

- Canada, Latin America, and the Caribbean

- How is the Canadian government responding?

- How are Latin American and Caribbean governments responding?

- International Economic and Supply Chain Issues

- What are the implications of the pandemic in China's economy?

- How is COVID-19 affecting the global economy and financial markets?

- How is COVID-19 affecting U.S. medical supply chains?

- Issues for Congress

Figures

Tables

- Table 1. Top 10 Countries with Confirmed COVID-19 Cases and Deaths

- Table 2. COVID-19 Cases and Deaths, by WHO Region

- Table 3. United Nations COVID-19 Appeal: April-December 2020

- Table 4. USAID Global Pandemic Preparedness Funding: FY2017-FY2021 Request

- Table 5. CDC Global Pandemic Preparedness Funding: FY2017-2020 Enacted

- Table A-1. Report Authors

Appendixes

Summary

In December 2019, hospitals in the city of Wuhan in China's Hubei Province began seeing cases of pneumonia of unknown origin. Chinese health authorities ultimately connected the condition, later named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), to a previously unidentified strain of coronavirus. The disease has spread to almost every country in the world, including the United States. WHO declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 30, 2020; raised its global risk assessment to "Very High" on February 28; and labeled the outbreak a "pandemic" on March 11. In using the term pandemic, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus cited COVID-19's "alarming levels of spread and severity" and governments' "alarming levels of inaction." As of May 14, 2020, WHO had reported more than 4.2 million COVID-19 cases, including almost 300,000 deaths, of which more than 40% of all cases and 55% of all deaths were identified in Europe, and more than 30% of all cases and nearly 30% of all deaths were identified in the United States. Members of Congress have demonstrated strong interest in ending the pandemic domestically and globally. To date, Members have introduced dozens of pieces of legislation on international aspects of the pandemic (see the Appendix).

Individual countries are carrying out not only domestic but also international efforts to control the COVID-19 pandemic, with the WHO issuing guidance, coordinating some international research and related findings, and coordinating health aid in low-resource settings. Countries are following (to varying degrees) WHO policy guidance on COVID-19 response and are leveraging information shared by WHO to refine national COVID-19 plans. The United Nations (U.N.) Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) is requesting almost $7 billion to support COVID-19 efforts by several U.N. entities. International financial institutions (IFIs), including the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and the regional development banks, are mobilizing their financial resources to support countries grappling with the COVID-19 pandemic. The IMF has announced it is ready to tap its total lending capacity, about $1 trillion, to support governments responding to COVID-19. The World Bank can mobilize about $150 billion over the next 15 months, and the regional development banks are also preparing new programs and redirecting existing programs to help countries respond to the economic ramifications of COVID-19.

On January 29, 2020, President Donald Trump announced the formation of the President's Coronavirus Task Force, led by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and coordinated by the White House National Security Council (NSC). On February 27, the President appointed Vice President Michael Pence as the Administration's COVID-19 task force leader, and the Vice President subsequently appointed the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) Ambassador Deborah Birx as the "White House Coronavirus Response Coordinator." On March 6, 2020, the President signed into law the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2020, P.L. 116-123, which provides $8.3 billion for domestic and international COVID-19 response. The Act includes $300 million to continue the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) global health security programs and a total of $1.25 billion for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and Department of State. Of those funds, $985 million is designated for foreign assistance accounts, including $435 million specifically for Global Health Programs. On March 27, 2020, President Trump signed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act), P.L. 116-136, which contains emergency funding for U.S. international COVID-19 responses, including $258 million to USAID through the International Disaster Assistance (IDA) account and $350 million to the State Department through the Migration and Refugee Assistance (MRA) account (P.L. 116-127).

The pandemic presents major consequences for foreign aid, global health, diplomatic relations, the global economy, and global security. Regarding foreign aid, Congress may wish to consider how the pandemic might reshape pre-existing U.S. aid priorities—and how it may affect the ability of U.S. personnel to implement and oversee programs in the field. The pandemic is also raising questions about deportation and sanction policies, particularly regarding Latin America and the Caribbean and Iran. In the 116th Congress, Members have introduced legislation to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic in particular and to address global pandemic preparedness in general. This report focuses on global implications of and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, and is organized into four broad parts that answer common questions regarding: (1) the disease and its global prevalence, (2) country and regional responses, (3) global economic and trade implications, and (4) issues that Congress might consider. For information on domestic COVID-19 cases and related responses, see CRS Insight IN11253, Domestic Public Health Response to COVID-19: Current Status and Resources Guide, by Kavya Sekar and Ada S. Cornell.

Introduction

In December 2019, a new disease, later called COVID-19, emerged in China and quickly spread around the world. The disease presents major consequences for global health, foreign relations, the global economy, and global security. International institutions and country governments are taking a variety of responses to address these challenges. In the 116th Congress, Members have introduced legislation to respond to COVID-19 in particular and to address global pandemic preparedness in general that are now occurring on a global scale. This report focuses on global implications of and responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, and is organized into four broad parts that answer common questions regarding: (1) the disease and its global prevalence, (2) country and regional responses, (3) global economic and trade implications, and (4) issues that Congress might consider. For information on domestic COVID-19 cases and related responses, see CRS Insight IN11253, Domestic Public Health Response to COVID-19: Current Status and Resources Guide, by Kavya Sekar and Ada S. Cornell.

What are coronaviruses and what is COVID-19?1

Coronaviruses that typically infect humans are common pathogens, which can cause mild illnesses with symptoms similar to the common cold, or severe illness, potentially resulting in death of the victim. Prior to COVID-19, two "novel" coronaviruses (i.e., coronaviruses newly recognized to infect humans) have caused serious illness and death in large populations, namely severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2002-2003 and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), which was first identified in 2012 and continues to have sporadic transmission from animals to people with limited human-to-human spread.2

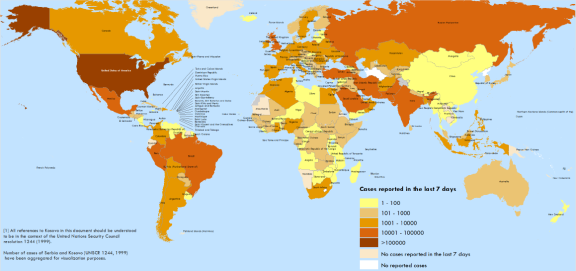

The origin of COVID-19 is unknown, although genetic analysis suggests an animal source.3 The World Health Organization (WHO) first learned of pneumonia cases from unknown causes in Wuhan, China, on December 31, 2019. In the first days of January 2020, Chinese scientists isolated a previously unknown coronavirus in the patients, and on January 11, Chinese scientists shared its genetic sequence with the international community. (See CRS Report R46354, COVID-19 and China: A Chronology of Events (December 2019-January 2020), by Susan V. Lawrence.) The virus is now present in most countries (Figure 1). For the purposes of this report, CRS refers to COVID-19 as the virus and the syndrome people often develop when infected.4

|

|

Source: World Health Organization, COVID-19 Situation Report 114, May 13, 2020. |

How is COVID-19 transmitted?5

Health officials and researchers are still learning about COVID-19. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the virus is thought to spread mainly from person-to-person between individuals who are in close contact with each other (less than six feet), through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs or sneezes.6 Health officials and researchers are still determining the virus's incubation period, or time between infection and onset of symptoms. CDC is using 14 days as the outer bound for the incubation period, meaning that the agency expects someone who has been infected to show symptoms within that period.

The CDC has confirmed that asymptomatic cases (infected individuals who do not have symptoms) can transmit the virus, though "their role in transmission is not yet known."7 A study of the 3,711 passengers on the Diamond Princess cruise ship found that 712 people (19.2% of the cruise ship passengers) tested positive for COVID-19. Almost half (331) of the positive cases were asymptomatic at the time of testing.8

What are global COVID-19 case fatality and hospitalization rates?9

The COVID-19 case fatality rate is difficult to determine; milder cases are not being diagnosed, death is delayed, and wide disparities exist in case detection worldwide. In addition, the case fatality rate in any given context may depend on a number of factors including the demographics of the population, density of the area, and the quality and availability of health care services. Scientists are using different methods to estimate case fatality and estimates range. One study of those diagnosed with COVID-19 estimated case fatality rates for Wuhan, China and other parts of China at 1.4% and 0.85%, respectively.10 Another estimated 3.6% within China and 1.5% outside the country,11 with a third recommending using a range of 0.2%-3.0%.12

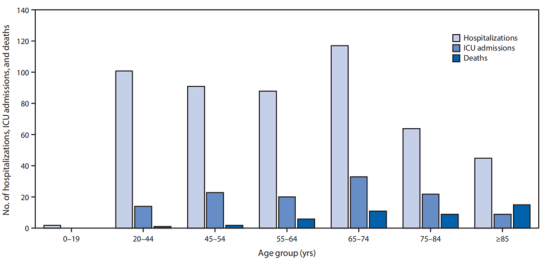

Current data suggest the elderly and those with preexisting medical conditions (including asthma, high blood pressure, heart disease, cancer, and diabetes) are more likely to become severely sickened by COVID-19. One study in China showed that 80% of those killed by the virus were older than 60 years and 81% of surveyed COVID-19 cases were mild.13 Another study showed that 87% of all hospitalized COVID-19 patients in China were aged between 30 and 79 years, though the study did not further disaggregate the data by age.14 Whereas the CDC found that the elderly had higher death rates, more than half (55%) of reported COVID-19 hospitalizations between February 12 and March 16, 2020, were of individuals younger than 65 years (Figure 2).15

Where are COVID-19 cases concentrated?16

As of May 13, 2020, national governments reported to the WHO more than 4 million cases of COVID-19 and almost 300,000 related deaths worldwide. Ten countries accounted for over 70% of all reported cases and almost 80% of all reported deaths (Table 1). The pandemic epicenter has shifted from China and Asia to the United States and Europe. China and Belgium are no longer among the 10 countries with the highest number of deaths, and Russia and Brazil joined the ranks. Almost 90% of all reported cases were identified in the WHO Americas and Europe regions (Table 2).17 Cases are continuing to rise in the Americas, where 88% of all cases were found in the United States (74%), Brazil (9%), and Canada (4%). In Europe, the cases are more widely distributed, and seven countries comprise 77% of all cases: Russia (14%), Spain (13%), United Kingdom (13%), Italy (12%), Germany (10%), Turkey (8%) and France (8%).

|

Country |

Cases |

Deaths |

% of All Cases |

% of All Deaths |

|

United States |

1,320,054 |

79,634 |

31.6 |

27.7 |

|

Russia |

242,271 |

2,212 |

5.8 |

0.8 |

|

Spain |

228,030 |

26,920 |

5.5 |

9.4 |

|

United Kingdom |

224,467 |

32,692 |

5.4 |

11.4 |

|

Italy |

221,216 |

30,911 |

5.3 |

10.8 |

|

Germany |

171,306 |

7,634 |

4.1 |

2.7 |

|

Brazil |

168,331 |

11,519 |

4.0 |

4.0 |

|

Turkey |

141,475 |

3,894 |

3.4 |

1.4 |

|

France |

138,161 |

26,948 |

3.3 |

9.4 |

|

Iran |

110,767 |

6,733 |

2.7 |

2.3 |

|

Top 10 Total |

2,968,078 |

229,097 |

71.2 |

79.7 |

|

Grand Total |

4,170,424 |

287,399 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Source: WHO, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report 114, May 13, 2020.

|

WHO Region |

Cases |

Deaths |

% of All Cases |

% of All Deaths |

|

Europe |

1,780,316 |

159,799 |

42.7 |

55.6 |

|

Americas |

1,781,564 |

106, 504 |

42.7 |

37.1 |

|

Western Pacific |

163,201 |

6,578 |

3.9 |

2.3 |

|

Eastern Mediterranean |

284,270 |

9,259 |

6.8 |

3.2 |

|

Southeast Asia |

110,932 |

3,746 |

2.7 |

1.3 |

|

Africa |

49,429 |

1,500 |

1.2 |

0.5 |

|

Diamond Princess |

712 |

13 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Total |

4,170,424 |

287,399 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Source: WHO, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report 114, May 13, 2020.

Note: WHO regions at https://www.who.int/chp/about/regions/en/, accessed on April 6, 2020.

COVID-19 Responses of International Institutions

Individual countries carry out both domestic and international efforts to control the COVID-19 pandemic, with the WHO issuing guidance, coordinating some international research and related findings, and coordinating health aid in low-resource settings. Countries follow (to varying degrees) WHO policy guidance on COVID-19 response and leverage information shared by WHO to refine national COVID-19 plans. The United Nations (U.N.) Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) is requesting $6.7 billion to support COVID-19 efforts by several U.N. entities (see "Multilateral Technical Assistance" section).18

International Health Regulations19

What rules guide COVID-19 responses worldwide?

WHO is the U.N. agency responsible for setting norms and rules on global health matters, including on pandemic response. The organization also develops and provides tools, guidance and training protocols. In 1969, the World Health Assembly (WHA)—the governing body of WHO—adopted the International Health Regulations (IHR) to stop the spread of six diseases through quarantine and other infectious disease control measures. The WHA has amended the IHR several times, most recently in 2005.20 The 2005 edition, known as IHR (2005), provided expanded means for controlling infectious disease outbreaks beyond quarantine. The regulations include a code of conduct for notification of and responses to disease outbreaks with pandemic potential, and carry the expectation that countries (and their territories) will build the capacity, where lacking, to comply with IHR (2005). The regulations mandate that WHO Member States

- build and maintain public health capacities for disease surveillance and response;

- provide or facilitate technical assistance to help low-resource countries develop and maintain public health capacities;

- notify WHO of any event that may constitute a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) and respond to requests for verification of information regarding such event; and

- follow WHO recommendations concerning public health responses to the relevant PHEIC.

Per reporting requirements of the IHR (2005), China and other countries are monitoring and reporting COVID-19 cases to WHO. Observers are debating the extent to which China is fully complying with IHR (2005) reporting rules (see "Asia" and the Appendix).

How does WHO respond to countries that do not comply with IHR (2005)?

IHR (2005) does not have an enforcement mechanism. WHO asserts that "peer pressure and public knowledge" are the "best incentives for compliance."21 Consequences that WHO purports non-compliant countries might face include a tarnished international image, increased morbidity and mortality of affected populations, travel and trade restrictions imposed by other countries, economic and social disruption, and public outrage.

China's response to the COVID-19 outbreak may deepen debates about the need for an IHR enforcement mechanism. On one hand, questions about the timeliness of China's reporting of the COVID-19 outbreak and questions about China's transparency thereafter might bolster arguments in favor of an enforcement mechanism. On the other hand, some have questioned whether the WHA would vote to abdicate some of its sovereignty to provide WHO enforcement authority.

How does the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) relate to IHR (2005) and pandemic preparedness?

IHR (2005) came into force in 2007, with signatory countries committing to comply by 2012. In 2012, only 20% of countries reported to the WHO that they had developed IHR (2005) core capacities, and many observers asserted the regulations needed a funding mechanism to help resource-constrained countries with compliance. In 2014, the WHO launched the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) as a five-year (2014-2018) multilateral effort to accelerate IHR (2005) implementation, particularly in resource-poor countries lacking the capacity to adhere to the regulations. The GHSA appeared to advance global pandemic preparedness capacity; more than 70% of surveyed countries reported in 2017 being prepared to address a global pandemic.22 Regional disparities persisted, however; about 55% of surveyed countries in the WHO Africa region reported being prepared for a pandemic, compared to almost 90% of countries surveyed in the WHO Western Pacific region. In 2017, participating countries agreed to extend the GHSA through 2024. For more information on the GHSA, see CRS In Focus IF11461, The Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA): 2020-2024, by Tiaji Salaam-Blyther.

Multilateral Technical Assistance

What is WHO doing to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic?23

In February 2020, WHO released a $675 million Strategic Preparedness and Response Plan for February through April 2020. WHO aims to provide international coordination and operational support, bolster country readiness and response capacity—particularly in low-resource countries—and accelerate research and innovation. As of May 8, private donors and 26 countries have contributed $536.5 million towards the plan, including $30.3 million from the United States.24 Countries have pledged an additional $198.5 million towards the plan. As of April 22, WHO has used the funds to

- purchase and ship personal protective equipment (PPE) to 133 countries, including

- 2,566,880 surgical masks and masks,

- 1,641,900 boxes of gloves,

- 184,478 gowns,

- 29,873 goggles, and

- 79,426 face shields;

- supply 1,500,000 diagnostic kits to 126 countries;

- develop online COVID-19 training courses in 13 languages; and

- enroll more than 100 countries in WHO-coordinated trials to accelerate identification of an effective vaccine and treatment, which include

- 1,200 patients,

- 144 studies, and

- 6 candidate vaccines in clinical evaluation and 77 in preclinical evaluation.25

In April 2020, the WHO issued an updated plan that provided guidance for countries preparing for a phased transition from widespread transmission to a steady state of low-level or no transmission, among other things.26 The update did not include a request for additional funds.

Also in April 2020, the WHO hosted a virtual event with the President of France, the President of the European Commission, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation where heads of state, the G20 President, the African Union Commission Chairperson, the U.N. Secretary General and leaders from a variety of nongovernmental organizations, including Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness and Innovation (CEPI), pledged their commitment to the Access to COVID-19 Tools (ACT Accelerator).27 The participants, and other partners who have since joined the effort, committed to "work towards equitable global access" to COVID-19 countermeasures (including vaccines and therapies). A pledging conference, hosted by the European Union (EU), took place on May 4 to support the effort. As of May 6, donors have pledged $7.4 billion for the ACT Accelerator and other global COVID-19 responses. The United States neither participated in the launch nor provided funding for the ACT Accelerator.

Debates about whether health commodities are a public good are long-standing and have intensified in recent years. For decades, countries have willingly donated virus samples to the WHO for international research. During a 2005-2007 H5N1 avian flu outbreak, however, Indonesia refused to share samples of the virus, asserting that companies were selling patented vaccines created from the donated samples at a price Indonesians could not afford.28 The WHO and its Member States, through the WHA, have not yet developed an agreement that satisfies poor countries concerned about affordability and wealthier countries (where most global pharmaceutical companies are based) concerned about recapturing research and development costs. The WHO has sought to negotiate prepurchasing agreement during each major outbreak since the H5N1 debacle. French officials, for example, have characterized any COVID-19 commodity that might be developed as a "public good," and they have criticized statements by a French pharmaceutical company on committing to provide the U.S. government first access to a COVID-19 vaccine that the company produces.29 The WHO has established the Solidarity Trial to coordinate international COVID-19-related research and development. Participating parties, including countries, pharmaceutical companies, and nongovernmental organizations, agree to openly share virus information and commodities developed with donated specimens.30 The EU and its Member States, and nine other countries, have drafted a resolution to be considered at the upcoming World Health Assembly on a unified international COVID-19 response, including on "the need for all countries to have unhindered timely access to quality, safe, efficacious and affordable diagnostics, therapeutics, medicines and vaccines ... for the COVID-19 response."31

How are international financial institutions responding to COVID-19?32

The international financial institutions (IFIs), including the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and specialized multilateral development banks (MDBs), are mobilizing unprecedented levels of financial resources to support countries grappling with the health and economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.33 About 100 countries—more than half of the IMF's membership—have requested IMF loans, and the IMF has announced it is ready to tap its total lending capacity, about $1 trillion, to support governments responding to COVID-19.34 In April 2020, the World Bank pledged to mobilize about $160 billion through 2021, and other multilateral development banks committed about $80 billion over the same time period.35 MDB support is expected to cover a wide range of activities, including strengthening health services and primary health care, bolstering disease monitoring and reporting, training front-line health workers, encouraging community engagement to maintain public trust, and improving access to treatment for the poorest patients. In addition, at the urging of the IMF and the World Bank, the G-20 countries in coordination with private creditors have agreed to suspend debt payments for low-income countries through the end of 2020.

Policymakers are discussing a number of policy actions to further bolster the IFI response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Examples include changing IFI policies to allow more flexibility in providing financial assistance, pursuing policies at the IMF to increase member states' foreign reserves, and providing debt relief to low-income countries. Some of these policy proposals would require congressional legislation. Through the stimulus legislation (P.L. 116-136), Congress accelerated authorizations requested by the Administration in the FY2021 budget for the IMF, two lending facilities at the World Bank, and two lending facilities at the African Development Bank.

What is the U.N. humanitarian response to the COVID-19 pandemic?36

Outside of the WHO, other U.N. entities and their implementing partners are considering how to maintain ongoing humanitarian operations while preparing for COVID-19 cases should they arise.37 On March 17, 2020, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) announced they were suspending global resettlement travel for refugees due to the COVID-19 travel bans.38 Cessation of resettlement may reinforce population density in refugee camps and other settlements, which might further complicate efforts to address COVID-19 outbreaks in such settings.

Many experts agree that even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the scope of current global humanitarian crises was unprecedented.39 The U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) estimated that in 2020, nearly 168 million people in 53 countries would require humanitarian assistance and protection due to armed conflict, widespread or indiscriminate violence, and/or human rights violations.40 The 2020 U.N. global humanitarian annual appeal totaled an all-time high of more than $28.8 billion, excluding COVID-19 responses.41 The appeal also focused on the needs of displaced populations, which numbered more than 70 million people, including 25.9 million refugees, 41.3 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) and 3.5 million asylum seekers.42 In addition, natural disasters are also key drivers of displacement each year.43

Humanitarian experts agree that the conditions in which vulnerable, displaced populations live make them particularly susceptible to COVID-19 spread and present significant challenges to response and containment.44 Overcrowded living spaces and insufficient hygiene and sanitation facilities make conditions conducive to contagion.45 In many situations, disease control recommendations are not practical. Space is not available to create isolation and "social-distancing," for example, and limited access to clean water and sanitation make regular and sustained handwashing difficult.46 In addition, low or middle-income countries that are likely to struggle to respond effectively to the pandemic host 85% of refugees worldwide.47 So far, relatively few COVID-19 cases have been reported among the displaced and those affected by conflict or natural disasters, although there is a widespread lack of testing.48

On March 25, 2020, the United Nations launched a $2.01 billion global appeal for the COVID-19 pandemic response to "fight the virus in the world's poorest countries, and address the needs of the most vulnerable people" through the end of the year.49 According to the United Nations, as of early May, donors had so far provided $923 million toward the initial appeal and contributed $608 million outside the plan.50 On May 7, 2020, the United Nations announced it had tripled the appeal to $6.7 million and expanded its coverage to 63 countries as it became clear that COVID-19's "most devastating and destabilizing effects will be felt in the world's poorest countries."51 While the United Nations does not expect the pandemic to peak in the world's poorest countries for another three to six months, already there are reports of "incomes plummeting and jobs disappearing, food supplies falling and prices soaring, and children missing vaccinations and meals."52 The updated plan brings together humanitarian appeals from other U.N. agencies in an effort to coordinate emergency health and humanitarian responses (see Table 3).

UNOCHA will coordinate the U.N.-wide response, but most of the activities will be carried out by specific U.N. entities, non-governmental organizations, and other implementing partners. U.N. guidance for scaling up responses in refugee and IDP settings includes addressing mental health and psychological aspects, adjusting food distribution, and developing prevention and control mechanisms in schools.53 Some experts recommend incorporating COVID-19 responses within existing humanitarian programs to ensure continuity of operations and to protect aid personnel while facilitating their access in areas where travel has been restricted.54

|

Type of Response Plan |

Health |

Nonhealth |

Total |

|

Global support services |

0.0 |

0.0 |

1,010 |

|

Humanitarian Response Plans |

1,300 |

2,180 |

3,490 |

|

Regional Refugee Response Plans |

265 |

729 |

994 |

|

Regional Refugee and Migrant Response Plan |

132 |

306 |

439 |

|

Other plans |

92 |

65 |

157 |

|

New plans |

235 |

394 |

629 |

|

Total |

2,024 |

3,674 |

6,708 |

Source: UNOCHA, Global Humanitarian Response Plan COVID-19: United Nations Coordinated Appeal April – December 2020, May Update, May 7, 2020.

Notes: Each U.N. agency's role in implementing the plan is described briefly on pp. 40-43 of the above cited report.

U.S. Support for International Responses

On January 29, 2020, President Donald Trump announced the formation of the President's Coronavirus Task Force, led by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and coordinated by the White House National Security Council (NSC).55 On February 27, the President appointed Vice President Michael Pence as the Administration's COVID-19 task force leader, and the Vice President subsequently appointed the head of the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), Ambassador Deborah Birx, as the White House Coronavirus Response Coordinator.56 International COVID-19 response efforts carried out by U.S. federal government departments and agencies, including those in the Task Force, are described below.57

Emergency Appropriations for International Responses58

On March 6, 2020, the President signed into law P.L. 116-123, Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2020, which provides $8.3 billion for domestic and international COVID-19 response.59 The Act includes $300 million to continue the CDC's global health security programs and a total of $1.25 billion for the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and Department of State. USAID- and Department of State-administered aid includes the following:

- Global Health Programs (GHP). $435 million for global health responses (see "U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)"), including $200 million for USAID's Emergency Reserve Fund (ERF).60

- International Disaster Assistance (IDA). $300 million for relief and recovery efforts in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Economic Support Fund (ESF). $250 million to address COVID-19-related "economic, security, and stabilization requirements."

The Act also provides $1 million to the USAID Office of Inspector General to support oversight of COVID-19-related aid programming.

On March 27, 2020, President Trump signed P.L. 116-136, Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, which contains emergency funding for U.S. international COVID-19 responses, including the following:

- International Disaster Assistance (IDA). $258 million to "prevent, prepare for, and respond" to COVID-19.

- Migration and Refugee Assistance (MRA). $350 million to the State Department-administered MRA account to "prevent, prepare for, and respond" to COVID-19.

U.S. Department of State61

How does the State Department help American citizens abroad?

Section 43 of the State Department Basic Authorities Act of 1956 (P.L. 84-885; hereinafter, the Basic Authorities Act) requires the State Department to serve as a clearinghouse of information on any major disaster or incident that affects the health and safety of U.S. citizens abroad.62 The department implements this statutory responsibility through its Consular Information Program (CIP), which provides a range of products, including but not limited to country-specific information web pages, Travel Advisories, Alerts, and Worldwide Cautions. Travel Advisories range from Level 1 (Exercise Normal Precautions) to Level 4 (Do Not Travel).

On March 31, 2020, the State Department issued an updated Level 4 Global Health Advisory advising U.S. citizens to avoid all international travel due to the global impact of COVID-19.63 Level 4 Travel Advisories do not constitute a travel ban. Instead, they advise U.S. citizens not to travel because of life threatening risks and, in some cases, limited U.S. government capability to provide assistance to U.S. citizens.64 The State Department's Level 4 Global Health Advisory notes that because the State Department has authorized the departure of U.S. personnel abroad who are "at higher risk of a poor outcome if exposed to COVID-19," U.S. embassies and consulates may have more limited capacity to provide services to U.S. citizens abroad.65

CIP products are posted online and disseminated to U.S. citizens who have registered to receive such communications through the Smart Traveler Enrollment Program (STEP). The Assistant Secretary for Consular Affairs is responsible for supervising and managing the CIP. 66 State Department regulations provide that when health concerns rise to the level of posing a significant threat to U.S. citizens, the State Department will publish a web page describing the health-related threat and resources.67 The Bureau of Consular Affairs has developed such a web page for the COVID-19 pandemic.68 Additionally, the State Department has created a website providing COVID-19-related information and resources for every country in the world.69 Furthermore, on March 24, 2020, the State Department began publishing a daily COVID-19 newsletter, developed for Members of Congress and congressional staff, intended to "dispel rumor, combat misinformation, and answer any outstanding questions regarding the Department's overseas crisis response efforts."70

What are the authorities and funding for the State Department to carry out overseas evacuations?

The Omnibus Diplomatic Security and Antiterrorism Act of 1986 (P.L. 99-399) authorizes the Secretary of State to carry out overseas evacuations. Section 103 of this law requires the Secretary to "develop and implement policies and programs to provide for the safe and efficient evacuation of United States Government personnel, dependents, and private United States citizens when their lives are endangered."71 In addition, the Basic Authorities Act authorizes the Secretary to make expenditures for overseas evacuations. Section 4 of this law authorizes both expenditures for the evacuation of "United States Government employees and their dependents" and "private United States citizens or third-country nationals, on a reimbursable basis to the maximum extent practicable," leaving American citizens or third-country nationals generally responsible for the cost of evacuation, although emergency financial assistance may be available for destitute evacuees.72 Furthermore, the Basic Authorities Act limits the scope of repayment to "a reasonable commercial air fare immediately prior to the events giving rise to the evacuation."73

In practice, even when the State Department advises private U.S. citizens to leave a country, it will advise them to evacuate using existing commercial transportation options whenever possible. This is reflected in the State Department's current Level 4 Global Health Advisory, which states that "[i]n countries where commercial departure options remain available, U.S. citizens who live in the United States should arrange for immediate return."74 In more rare circumstances, when the local transportation infrastructure is compromised, the State Department will arrange chartered or non-commercial transportation for U.S. citizens to evacuate to a safe location determined by the department. Following the outbreak of COVID-19, the State Department has made such arrangements for thousands of U.S. citizens throughout the world, initially those in Wuhan, China and, shortly thereafter, U.S. citizen passengers who were quarantined on the Diamond Princess cruise ship in Yokohama, Japan. As demand for repatriation surged, the State Department leveraged new options to evacuate U.S. citizens, including "commercial rescue flights." To facilitate these flights, the department worked with the airline industry to help them secure the needed clearances to carry out evacuation flights in high-demand countries.75 The State Department said that these flights enabled it to focus its own resources to send chartered flights where "airspace, border closures, and internal curfews have been the most severe."76 While evacuations are still ongoing, the department estimated in late April that around 40% of U.S. citizens who were evacuated for reasons related to COVID-19 returned to the United States on commercial rescue flights.77

Congress authorizes funding for the evacuation-related activities through the Emergencies in the Diplomatic and Consular Service (EDCS) account, which is part of the annual Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs (SFOPS) appropriation. For FY2020, Congress appropriated $7.9 million for this account.78 Congress typically funds this account through no-year appropriations, thereby authorizing the State Department to indefinitely retain funds.79 The State Department is able to further fund emergency evacuations using transfer authorities provided by Congress. In recent SFOPS appropriations, for example, Congress has authorized the State Department to transfer and merge funds appropriated to the Diplomatic Programs, Embassy Security, Construction, and Maintenance, and EDCS accounts for emergency P.L. 116-123, evacuations.80

In addition to the funds and transfer authorities provided in annual appropriations legislation, Congress appropriated an additional $588 million for State Department operations (including $264 million appropriated through P.L. 116-123 and $324 million appropriated through P.L. 116-136) to "prevent, prepare for, and respond to coronavirus," including by carrying out evacuations. P.L. 116-123 also increased the amount of funding the State Department is authorized to transfer from the Diplomatic Programs account to the EDCS account for emergency evacuations during FY2020 from $10 million to $100 million.81

How many evacuations have been carried out due to the COVID-19 pandemic?

The State Department began arranging evacuations of U.S. government personnel and private U.S. citizens in response to the COVID-19 pandemic on January 28, 2020, when the department started evacuating over 800 American citizens from Wuhan, China. An additional 300 American citizens who were passengers aboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship were subsequently evacuated in February. When COVID-19 continued to spread and was declared a global pandemic by WHO, the State Department accelerated its efforts to evacuate Americans amid actions by countries to close their borders and implement mandatory travel restrictions. On March 19, 2020, the State Department established a repatriation task force to coordinate and support these efforts. As of May 11, 2020, the State Department had coordinated the repatriation of more than 85,000 Americans on 886 flights.82 The State Department's current Level 4 Global Health Advisory warns that while the department is "making every effort to assist U.S. citizens overseas who wish to return to the United States, funds "may become more limited or even unavailable."83 Some Members of Congress have applauded the State Department's efforts to scale up consular assistance to U.S. citizens abroad during the COVID-19 pandemic. Other Members have expressed concern that as COVID-19 spread worldwide, the State Department was slow to communicate with and provide options to Americans abroad seeking repatriation.84

U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)85

Where is USAID providing COVID-19 assistance?

USAID is providing assistance to more than 100 affected and at-risk developing countries facing the threat of COVID-19.86 USAID identified these countries through a combination of the following criteria:

- trend of increasing confirmed cases of COVID-19, especially with evidence of local transmission;

- imported cases with high risk for local transmission due to connectivity to a hotspot;

- low scores on the Global Health Security Index87 classification of health systems and on the Global Health Security Agenda Joint External Evaluation, which measures compliance with IHR (2005);

- other vulnerabilities (unstable political situation, displaced populations); and

- the existence of other U.S. global health programs that could be leveraged.

USAID is also providing funding to multilateral organizations, including the WHO, UNICEF, and the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies for COVID-19 assistance, and to facilitate coordination with other donors.

What type of assistance does USAID provide for COVID-19 control?

On February 7, 2020, USAID committed $99 million from the Emergency Reserve Fund (ERF) for Contagious Infectious Diseases. USAID received $986 million from the first emergency supplemental appropriation and an additional $353 million from the second. Examples of activities to which USAID resources will be programed include

- assisting target countries to prepare their laboratories for COVID-19 testing,

- implementing a public-health emergency plan for points of entry,

- activating case-finding and event-based surveillance for influenza-like illnesses,

- training and equipping rapid-response teams,

- investigating cases and tracing the contacts of infected persons, and

- adapting health worker training materials for COVID-19.

As of May 1, 2020, USAID pledged to provide $653 million for international COVID-19 response, $215 million of which has been obligated.88 The pledged amounts include $99 million from the ERF, $100 million from the Global Health Programs (GHP) account, $300 million in humanitarian assistance from the International Disease Assistance (IDA) account, and $153 million from the Economic Support Fund (ESF).

How do USAID COVID-19 responses relate to regular pandemic preparedness activities?

Congress appropriates funds for USAID global health security and pandemic preparedness activities through annual State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs appropriations (Table 4). From FY2009 through FY2019, the bulk of USAID's pandemic preparedness activities have been implemented through the Emerging Pandemic Threats (EPT) program. Those efforts comprised USAID's contribution towards advancing the Global Health Security Agenda (see "International Health Regulations") and are being leveraged for COVID-19 responses worldwide. Key related activities include

- strengthening surveillance systems to detect and report disease transmission;

- upgrading veterinary and other national laboratories;

- strengthening programs to combat antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in the public health and animal-health sectors;

- training community health volunteers in epidemic control and designing community-preparedness plans;

- conducting simulation exercises to prepare for future outbreaks; and

- establishing or strengthening emergency supply-chain programs specially designed to deliver critically needed commodities (e.g., personal protective equipment) to affected communities during outbreaks.

The PREDICT project was a key part of the EPT program. According to USAID, the second phase of the project, PREDICT-2 (2015-2019), helped nearly 30 countries detect and discover viruses with pandemic potential. The project has

- detected more than 1,100 unique viruses, 931 of which were novel viruses (such as Ebola and coronaviruses);

- sampled over 163,000 animals and people; and

- provided $207 million from 2009 through 2019.

USAID has responded to 42 outbreaks through PREDICT-2, which ended in March 2020 (following a three-month extension). In May 2020, USAID announced that it will use the lessons learned through PREDICT to inform its new STOP Spillover project. The STOP Spillover project is aimed at building capacity in partner countries to stop the spillover of zoonotic diseases into humans. USAID aims to "award the STOP Spillover project by the end of September 2020, through a competitive process, as PREDICT sunsets as scheduled."89

Table 4. USAID Global Pandemic Preparedness Funding: FY2017-FY2021 Request

(current U.S. $ millions)

|

Fiscal Year |

Amount |

|

FY2017 Enacted |

72.5 |

|

FY2018 Enacted |

72.5 |

|

FY2019 Enacted |

100.0 |

|

FY2020 Enacted |

100.0 |

|

FY2021 Requested |

115.0 |

Source: Congressional budget justifications and appropriations legislation.

Notes: Excludes emergency appropriations for controlling the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa.

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)90

What role is CDC playing in international COVID-19 responses?

CDC has staff stationed in more than 60 countries who have been providing technical support, where relevant, and is receptive to bilateral requests for assistance or requests for assistance through the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN). CDC is working with WHO and other partners, including USAID and the Department of State, to assess needs and accelerate COVID-19 control, particularly by helping countries to implement WHO recommendations related to the diagnosis and care of patients, tracking the epidemic, and identifying people who might have COVID-19.

Through supplemental appropriations (P.L. 116-123), Congress provided CDC $300 million for global disease detection and emergency response. CDC plans to obligate $150 million of the funds by the end of FY2020. Related efforts will focus on

- disease surveillance,

- laboratory diagnostics,

- infection prevention and control,

- border health and community mitigation, and

- vaccine preparedness and disease prevention.

CDC is reportedly working closely with USAID and Department of State to ensure a coordinated U.S. government approach to the COVID-19 pandemic. CDC is prioritizing countries based on

- the current status of COVID-19 in country and future trajectory of its spread;

- the ability to effectively implement activities given CDC presence, capacity and partnerships in the country; and

- the capacity to provide support to other countries in the region.

CDC staff are working with colleagues in partner countries to conduct investigations that will help inform COVID-19 response efforts.

How do CDC COVID-19 responses relate to regular pandemic preparedness activities?

Through the Global Health Protection line item of annual Labor-HHS appropriations, CDC works to enhance public health capacity abroad and improve global health security, particularly through GHSA (Table 5). CDC works to bolster global health security and pandemic preparedness in 19 countries by focusing on enhancing the core foundations of what CDC views as strong public health systems—comprehensive disease surveillance and integrated laboratory systems, a strong public health workforce, and capable emergency management structures.

Programs within CDC's global health security portfolio include the following:

- The Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP) trains a global workforce of field epidemiologists to increase countries' ability to detect and respond to disease threats, address the global shortage of skilled epidemiologists, and deepen relationships between CDC and other countries. Over 70 countries have participated in FETP with more than 10,000 graduates.

- National Public Health Institutes (NPHI) help more than 26 partner countries carry out essential public health functions and ensure accountability for public health resources. The program focuses on improving the collection and use of public health data, as well as the development, implementation, and monitoring of public health programs.

- Global Rapid Response Team (GRRT) is a team of public health experts who remain ready to deploy for supporting emergency response and helping partner countries achieve core global health capabilities. The GRRT focuses on field-based logistics, communications, and management operations. Since the GRRT's inception, more than 500 CDC staff have provided over 30,000 person-days of response support. From January through March 2020, CDC staff has completed more than 100 deployments for COVID-19 response. Core and surge members support domestic deployments to quarantine stations and repatriation sites, international deployments, WHO and country office operations, and the Emergency Operations Center in Atlanta.

- The Public Health Emergency Management (PHEM) program trains public health professionals affiliated with international ministries of health on emergency management and exposes them to the CDC Public Health Emergency Operations Center. To date, the program has graduated 142 fellows from 37 countries (plus the African Union).

|

Fiscal Year |

Amount |

|

FY2017 Enacted |

58.2 |

|

FY2018 Enacted |

108.2 |

|

FY2019 Enacted |

108.2 |

|

FY2020 Enacted |

183.2 |

Source: Correspondence with CDC, March 27, 2020.

Notes: In the Labor, HHS Appropriations, these activities are described as Global Public Health Protection. For the purposes of this report, these activities are referred to as pandemic preparedness.

U.S. Department of Defense (DOD)

What is the DOD global COVID-19 response?91

DOD is conducting medical surveillance for COVID-19 worldwide.92 Related activities entail daily monitoring of reported cases, including persons under investigation (PUI), confirmed cases, and locations of such individuals,93 as well as surveillance for COVID-19 at China's southern border.94 DOD is supporting the U.S. CDC with additional laboratory capabilities. The DOD Laboratory Network, which includes military facilities in the United States and in certain overseas locations, has made available to interagency network laboratories its "detection and characterization capabilities … to support COVID-19-related activities across the globe."95 The Secretary of Defense also has directed geographic combatant commanders96 to "execute their pandemic plans in response to the [COVID-19] outbreak."97

Emergency Appropriations for DOD Responses98

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act (P.L. 116-127) became law on March 18, 2020. Title II of Division A of the act included $82 million for the Defense Health Program to waive all TRICARE cost-sharing requirements related to COVID-19.99

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act; P.L. 116-136) became law on March 27, 2020. Title III of Division B of the act included $10.5 billion in emergency funding for DOD. Of the $10.5 billion, $4.9 billion (47%) is for the Defense Health Program (DHP), according to the bill text. The DHP funding included $1.8 billion for patient care and procurement of medical and protective equipment; $1.6 billion to increase capacity in military treatment facilities; $1.1 billion for private-sector care; and $415 million to develop vaccines and to procure diagnostic tests, according to a summary released by the Senate Appropriations Committee.100 H.R. 748 also provided

- $2.5 billion for the defense industrial base, including $1.5 billion in defense working capital funds and $1 billion in Defense Production Act purchases;

- $1.9 billion in operations and maintenance (O&M) funding for the Services, in part to support deployment of the hospital ships USNS COMFORT and USNS MERCY to ease civilian hospital demand by caring for non-COVID patients; and

- $1.2 billion in military personnel (MILPERS) funding for Army and Air National Guard personnel deployments.

DOD has not detailed how much of the emergency funding may be used to support international activities related to COVID-19, though DOD has stated it is working with the Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of State to provide support in dealing with the pandemic.101 As part of missions that began in March, Air National Guard C-17 cargo aircraft have transported hundreds of thousands of coronavirus testing swabs from Italy to the United States.102 The swabs have been distributed to medical facilities around the country at the direction of the Department of Health and Human Services.103

To what extent is COVID-19 affecting United States security personnel?104

The degree to which U.S. security operations around the world may be affected due to personnel becoming infected has yet to be determined.105 Numerous media reports suggest that various parts of the U.S. military have seen a significant number of servicemembers contract or die from COVID-19 related symptoms. Citing operational security concerns, on March 30, 2020 the Department of Defense (DOD) directed military service commanders not to share the number of personnel affected by the COVID-19. In justifying this policy the DOD stated, "We will not report the aggregate number of individual service member cases at individual unit, base or Combatant Commands. We will continue to do our best to balance transparency in this crisis with operational security."106 Also, as of April 1, 2020, reportedly the Department of Homeland Security had nearly 9,000 employees whose exposure to COVID-19 that has taken them out of the workforce,107 and deployed U.S. Naval vessels, such as the USS Theodore Roosevelt, have had their operational effectiveness called into question.108

Regional Implications of and Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Asia

What are the implications for U.S.-China relations?109

U.S.-China relations were fraught well before the outbreak of COVID-19, with the two governments engaging in a bitter trade war, competing for influence around the globe, and clashing over such issues as their activities in the South China Sea, China's human rights record, and China's Belt and Road Initiative. The pandemic appears to have increased the acrimony. On February 3, when the COVID-19 outbreak was at its peak in China, a spokesperson for China's Foreign Ministry blasted the United States for its response to the crisis there. "The U.S. government hasn't provided any substantive assistance to us, but it was the first to evacuate personnel from its consulate in Wuhan, the first to suggest partial withdrawal of its embassy staff, and the first to impose a travel ban on Chinese travelers," the spokesperson charged. "What it has done could only create and spread fear."110 Days later, Secretary of State Michael R. Pompeo announced the United States would make available up to $100 million in existing funds "to assist China and other impacted countries," and that the State Department had facilitated the delivery to China of 17.8 tons of personal protection equipment and medical supplies donated by the private sector.111

As COVID-19 transmission has accelerated in the United States, the Trump Administration has stepped up criticism of China's early response to the outbreak. Secretary Pompeo told an interviewer on March 24, "unfortunately, the Chinese Communist Party covered this up and delayed its response in a way that has truly put thousands of lives at risk."112 Spokespeople for the State Department and China's Foreign Ministry have traded COVID-19-related accusations on Twitter. On March 12, a Chinese spokesperson tweeted, "It might be US army who brought the epidemic to Wuhan."113 Secretary Pompeo accused China of waging a disinformation campaign "designed to shift responsibility," and President Trump for several days referred to COVID-19 as "the Chinese virus."114

On April 17, in announcing his decision to withhold U.S. funding from the World Health Organization, President Trump accused the multilateral institution of having "pushed China's misinformation about the virus, saying it was not communicable and there was no need for travel bans."115 Administration officials have also repeatedly suggested that a Chinese research institution may have been the source of the virus.116 On April 30, 2020, when asked if he had seen anything "that gives you a high degree of confidence that the Wuhan Institute of Virology was the origin of the virus," the President replied, "Yes, I have."117 The same day, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence stated that the intelligence community would continue efforts "to determine whether the outbreak began through contact with infected animals or if it was the result of an accident at a laboratory in Wuhan," indicating continuing uncertainties about the virus's origin.118

China has pushed back against U.S. allegations, including in a "Reality Check" document tweeted by a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson responding to 24 U.S. allegations, which the spokesperson calls "lies."119 (The document argues, for example, that the Wuhan Institute of Virology "does not have the capability to design and synthesize a new coronavirus, and there is no evidence of pathogen leaks or staff infections in the Institute.") Chinese spokespeople have gone on the offensive in criticizing the U.S. response to COVID-19 and have doubled down on spreading a conspiracy theory that the virus could have originated in the United States. On May 8, a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson tweeted, "The #US keeps calling for transparency & investigation. Why not open up Fort Detrick & other bio-labs for international review? Why not invite #WHO & int'l experts to the U.S. to look into #COVID19 source & response?"120

Some U.S.-based analysts have expressed alarm about the downward spiral in bilateral relations. Some see neither the United States nor China helping to coordinate a global response to the pandemic, and argue, "U.S.-China strategic competition is giving way to a kind of 'managed enmity' that is disrupting the world and forestalling the prospect of transnational responses to transnational threats."121 Others suggest, "There will be time later to assess the early mistakes of China and others in greater detail, but the virus is out there now and we should be tackling it together." Some have called for cooperation in vaccine development and distribution, and in addressing the economic crisis the virus is causing in the developing world."122

Writing in The Washington Post, China's Ambassador to the United States suggested on May 5 that China would still be open to cooperation. "Blaming China will not end this pandemic," he wrote. "On the contrary, the mind-set risks decoupling China and the United States and hurting our efforts to fight the disease, our coordination to reignite the global economy, our ability to conquer other challenges and our prospects of a better future."123 In a May 14, 2020, Fox News interview, President Trump said, however, that he had no desire to speak to China's leader Xi Jinping. He suggested that to punish China, "we could cut off the whole relationship." Apparently referring to the U.S. trade deficit with China, which was $378.6 billion in 2019, the President added, "You'd save $500 billion if you cut off the whole relationship."124

Several Members of Congress have introduced legislation criticizing China's response to the COVID-19 pandemic (see Appendix).

What are the implications in Southeast Asia?125

Southeast Asia was one of the first regions to experience COVID-19 infections and the outbreak could have broad social, political, and economic implications in the months ahead and possibly years ahead. The region's countries are deeply tied together through trade and the movement of labor, links that could be reshaped if the outbreak leads to broad policy changes. Their economies have already been affected by disruptions to these links, and broad economic networks and supply chains could be reshaped if the outbreak leads to broad policy changes.

As an example, Malaysia banned overseas travel on March 18, affecting approximately 300,000 Malaysians who work in neighboring Singapore. Malaysia, however, changed tack on April 14 and allowed Malaysians in Singapore to return if they agreed to be tested and placed in quarantine. In Singapore, widespread outbreaks among migrant laborers, mostly from South Asia, who live in crowded dormitories, have led to the region's largest number of COVID-19 infections.

Other regional issues include the following:

- Indonesia and the Philippines, the region's two most populous nations, appear to be experiencing widening outbreaks and may have a significantly larger COVID-19 case count than their public health systems are able to detect and address.126

- Malaysia and Thailand, which have undergone substantial political turmoil in recent years, have relatively new governments that could face legitimacy questions based on their responses to the pandemic and as their economies begin the process of opening.127

- Some nations, including the Philippines and Cambodia, have taken actions that raise concerns about human rights and freedoms. Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte has imposed strict lockdown measures that one U.N. official criticized as "highly militarized," and these measures have resulted in more than 120,000 arrests, disproportionally affecting poor urban residents.128 Human rights groups have criticized a draft emergency order by Cambodia's government that would give it greater control over traditional and social media.129

- Some of the region's poorest countries, including Burma and Laos, have reported relatively few COVID-19 cases, highlighting questions about transparency in nations that may be particularly vulnerable given their underdeveloped health systems.

Much of the Southeast Asian diplomatic calendar, which drives regional cooperation on a wide range of issues including trade and public health, has been cancelled or has moved to virtual meetings. The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) has cancelled this year's iteration of its annual Shangri-la Dialogue, slated for June 5-7, after consultations with the government of Singapore.130

What are the implications in Central Asia?131

In Central Asia, the economic impacts of the pandemic may affect the roles of Russia and China in the region. Given disruptions to trade and cross-border movement, the pandemic could reverse recent progress on regional connectivity, a U.S. policy priority in Central Asia. The COVID-19 pandemic is placing significant economic pressure on Central Asian countries due to declines in domestic economic activity, economic disruptions in China and Russia, and the fall in hydrocarbon prices. China has cut the volume of natural gas imports from Central Asia due to falling demand, and analysts speculate that Chinese investment in the region may also shrink. Turkmenistan sends almost all of its gas exports to China and is particularly vulnerable, as the Turkmen government uses gas exports to service billions of dollars of Chinese loans. The economic impact of the pandemic will likely interrupt the flow of remittances from Russia, where millions of Kyrgyz, Tajik, and Uzbek citizens work as labor migrants, accounting for significant percentages of their countries' GDPs.132

Some measures implemented to combat the spread of COVID-19 could provide governments in the region with the means to suppress political and media freedoms. Human Rights Watch has stated that Central Asian governments are failing to uphold their human rights obligations by limiting access to information and arbitrarily enforcing pandemic-related restrictions. In Kazakhstan, authorities have detained government critics and journalists on suspicion of "disseminating knowingly false information during a state of emergency," a charge that can be punished by up to seven years in prison. Kyrgyz authorities restricted the ability of independent media outlets to report for over a month using provisions in the country's state of emergency. The government of Tajikistan has been suppressing information on the pandemic, refusing to answer media questions and blocking a website that crowdsources information on COVID-19 fatalities in the country.133

What are the implications in South Asia?134

The seven countries of South Asia are home to about 1.8 billion people, nearly one-quarter of the world's population. In most South Asian countries, per capita spending on health care is relatively low and medical resources and capacities are limited.135 Dense populations and lack of hygiene are facilitating factors for pandemics, and with medical equipment needed to address the crisis in short supply, South Asia nations are likely to face serious risk.136 As of May 1, 2020, the United States had provided nearly $6 million in health assistance to help India slow the spread of COVID-19 and nearly $15 million to assist Pakistan's response.137

The COVID-19 crisis has put a broad hold on activities related to U.S.-India and regional multilateral security cooperation, as well as delayed sensitive negotiations on U.S.-India trade disputes. The postponement of a planned March visit to New Delhi by Secretary of Defense Mark Esper had led to worries by some of inertia in bilateral defense relations.138 With India and Pakistan still engaged in a deep-rooted militarized rivalry, any generalized South Asian crisis, especially in the disputed region of Kashmir, could lead to societal breakdowns and/or open interstate conflict between these two nuclear-armed countries.

India. Several U.S. and Indian firms are cooperating on research for a coronavirus vaccine.139 India is home to several major vaccine manufacturers and is the world's leading producer of hydrocholoquine, an anti-malarial drug President Trump has touted as a potential treatment for COVID-19. In April, the U.S. President suggested that the United States might retaliate against India if New Delhi bans export of the drug and fails to fulfill an existing large-scale U.S. purchase order. India has agreed to allow limited exports.140

The COVID-19 crisis has led to more acute questioning of the political leadership in India, where since last year Prime Minister Narendra Modi has faced mass protests over new citizenship laws and persecution of Muslims. Reports indicate that the health pandemic is fueling greater oppression and persecution of Indian Muslims, with that community coming under blame for the pandemic from some quarters. Accusations also have arisen that the New Delhi government is using the pandemic as a cover for increased efforts to limit press freedoms. India's Jammu and Kashmir territory—which came under a strict security lockdown in August 2019 and lost statehood in November—reportedly faces a "double lockdown" with the pandemic and resulting severe physical and psychological hardships. The New Delhi government may be using the pandemic as cover to further consolidate its grip on the disputed Kashmir Valley.141

In Pakistan, Prime Minister Imran Khan was already dealing with widespread disaffection related to his government's performance and legitimacy. In late March, the powerful military "stepped in and sidelined" the civilian leadership after the Khan government's national pandemic response was criticized for perceived indecisiveness. By some accounts, the Pakistan government has also "caved in to the demands of clerics" regarding lockdown regulations.142

In Bangladesh, social distancing is difficult for many living in densely populated areas. In addition, over 1 million displaced Rohingya reside in overcrowded and unsanitary camps along Bangladesh's border with Burma. Of these Rohingya, approximately 630,000 live in the Kutupalong camp, which may be the world's largest refugee camp. The population density in the camps—104,000 people per square mile in Kutupalong—poses challenges for social distancing, quarantine, and isolation. Any COVID-19 transmission in the camps would likely quickly overwhelm medical facilities and services, and because of the camps' porous perimeters, risk spreading into neighboring Bangladeshi towns and villages.143 Bangladesh reportedly quarantined a number of Rohingya on Bhansan Char island to prevent the spread of COVID-19.144

What are the implications in Australia and New Zealand?145